Dean Kuipers

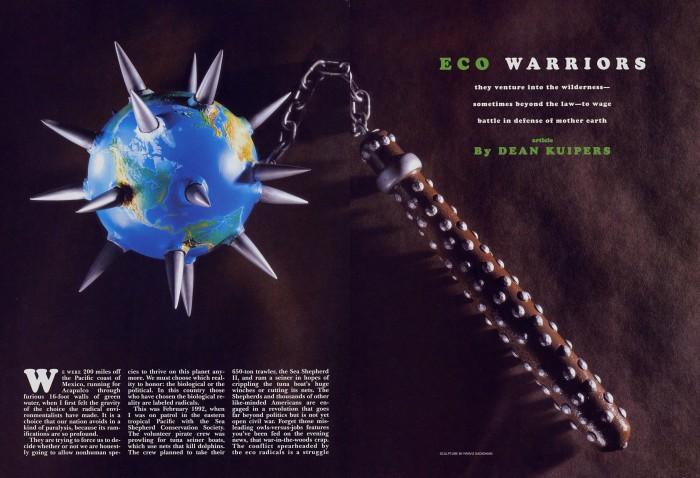

Eco Warriors

they venture into the wilderness--sometimes beyond the law--to wage battle in defense of mother earth

We were 200 miles off the Pacific coast of Mexico, running for Acapulco through furious 16-foot walls of green water, when I first felt the gravity of the choice the radical environmentalists have made. It is a choice that our nation avoids in a kind of paralysis, because its ramifications are so profound.

They are trying to force us to decide whether or not we are honestly going to allow nonhuman species to thrive on this planet anymore. We must choose which reality to honor: the biological or the political. In this country those who have chosen the biological reality are labeled radicals.

This was February 1992, when I was on patrol in the eastern tropical Pacific with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. The volunteer pirate crew was prowling for tuna seiner boats, which use nets that kill dolphins. The crew planned to take their 650-ton trawler, the Sea Shepherd II, and ram a seiner in hopes of crippling the tuna boat’s huge winches or cutting its nets. The Shepherds and thousands of other like-minded Americans are engaged in a revolution that goes far beyond politics but is not yet open civil war. Forget those misleading owls-versus-jobs features you’ve been fed on the evening news, that war-in-the-woods crap. The conflict spearheaded by the eco radicals is a struggle with ourselves, earth’s superpredators.

The Shepherds and their allies choose to preserve an ocean, not a fish farm scoured of competing predators and large mammals. They choose a North America that supports living, interconnected wilderness, not intensively managed zoo parks.

Before the storm I was in the galley of the Sea Shepherd II peeling a mango in 100 degree swelter and talking with one of the crew about efforts to reintroduce the grizzly bear to southern Colorado. At that moment the Sea Shepherd’s mission had nothing to do with grizzlies--but the bears had everything to do with the choice.

We know more now about the biology of wildness than ever before, and that makes some people crazy with fear. They worry how much we will have to lose personally if we commit to saving every species. A hobby? A job? An industry?

Everyone seems desperate for a compromise, but only a handful of people have the gall to point out that any further compromise means that grizzlies and Florida panthers and a raft of other critters will simply be dead, if they haven’t been killed off already. And so we decide like cowards: by default.

Folks don’t like to be told they are in denial, or that they have to be the first generation to sacrifice the American dream, and those are two reasons radical environmentalists are so hated. There’s also the fact that if you get in their way, they’ll sink your boat or spike your woodlot or torch your backhoe.

I don’t know why that hit me so hard falling through the spray off the Gulf of Tehuantepec at two A.M. Perhaps it was the tooth-grinding speed of the antihistamines I got in Panama, or the yawning green face of death trying to swallow the bow every minute or so. Maybe it was because the crew of fierce ecoteurs had left a photographer and me at the helm while they lay on the floor trying not to be seasick. At that moment it looked as if their hands-on approach to environmentalism would kill us all.

I had boarded the Sea Shepherd II to dig out what these eco warriors mean to our society, in the sense that hippies meant something to America in the Sixties and punks meant something to the suburbs in the Seventies. What I found is that these people always defer to what dolphins mean, or what 800-year-old redwoods mean. I’ve ended up with a portrait of wilderness as a player in a human conflict, a living entity with real needs, even desires. These couple thousand wild men and women have just loaned the wilderness their voices, their faces. And that changes everything.

•

When I asked Mike Roselle to tell me about his favorite action, or ecodefense, he didn’t hesitate. It was the one that earned him the small army of enemies who now speak of him with homicide in their voices.

A band of desert saboteurs from Earth First resolved in 1989 to put an end to the desert motorcycle race called the Barstow to Vegas, which ran through the East Mojave scenic area, a prospective national park and habitat of the desert tortoise, kangaroo rat and other creatures.

“The night before the race, we took a trailerload of railroad ties and four-by-eights down to the track,” remembers Roselle, a former oil-field roughneck and one of the five men who cooked up the idea for Earth First on a camping trip to Mexico’s Sonora Desert in 1980. “See, they had to go under Interstate Fifteen. There was this tunnel about six feet wide, eight feet high and one hundred fifty feet long that was made for water to go through. We built this cube to the size of the culvert, and at night we set it up in the middle of the tunnel.”

“I want you to picture this,” snaps Rick Siemans, senior editor of Dirt Bike magazine and head of the Sahara Club, a race sponsor. “Here are top expert riders going a hundred and ten miles pher hour down a sand wash at eleven o’clock, sun directly overhead, coal-black shadows, dust on their goggles, and they’re going to dart through this shadow, assumedly, and go to the other side. If our people hadn’t spotted that, they would have killed a half-dozen riders.”

Roselle says there were rules that the riders were supposed to walk their bikes through that culvert, Siemans says there weren’t. Whoever is right, the conflict born in that moment shows why neither the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society nor other desert protection leaders can openly cheer for Earth First. In this case, though, Ef won. The next year the government closed the course.

And now there’s a grudge. Around that time, a Sahara Club member called his pals to say someone at a local bar had keyed the paint and slashed the tires on his $30,000 work truck, which had Sahara Club stickers on it.

Siemans and his pals went to the bar the next week and parked a van in the same spot, stuck with so many stickers it “looked like a rolling billboard.” Siemans tells this part with relish: “It didn’t take twenty minutes and here came two guys outside. Long hair, scraggly-ass beards, the prototype earrings, the red shirts with the clenched fists [EF shirts]. They were getting ready to do the job on this van.

“We have our special division called the Sahara Clubbers,” he continues, “and I’m the smallest. I’m five-foot-nine, two hundred twenty-five pounds. Big Terry is our biggest. He’s six-five, three sixty-five. We jumped out and confronted these two boys. One of them was so upset he pissed himself right on the spot. We said, ‘We’re gonna let you boys be a warning. The next group we catch, we’re gonna break fingers and kneecaps.’

“We then handcuffed them face-to-face around a big tree. We slit their clothes off, left them bare-ass naked. Spray-painted their asses fluorescent orange and then called the cops and told them we’d apprehended a couple car thieves.

“That was our message to Earth First. If they fucked with us again, Sahara Clubbers were simply going to take baseball bats and do the justice that the authorities wouldn’t do.”

The Ef boys violated rule number two of direct action. The first rule--codified by Edward Abbey, whose novel The Monkey Wrench Gang was an inspiration for EF--is to honor all life and not hurt anyone. Abbey’s second rule: Don’t get caught.

•

The National Wildlife Federation, the largest environmental group in the U.S., compiles a national directory listing some 2000 conservation groups. But only a couple of these groups are radical--eco warriors, green guerrillas, biodiversity activists, part of the deep ecology movement.

We don’t have a tidy name for these groups, but I define them this way: One, they base campaigns on a no-compromise stance that reflects biological necessity. Two, they spend their time and money on direct action. That means they try to prevent environmental degradation by, for instance, locking their necks to bulldozers with kryptonite locks, by occupying trees or by freeing fur-farm animals. Three, they are grass roots groups with no pay, no perks and no corporate flowcharts.

In the U.S., we’re talking about only a few major groups. There’s Earth First, a loose, slowly growing network of 1300 to 2000 guerrillas all over North America. Anybody who wants to can secure a list of EF contacts, complete with names and phone numbers.

Then there are the Sea Shepherds, the original no-compromise commandos launched in 1977 by former (continued on page 122)Eco Warriors(continued from page 76) Canadian Coast Guard officer Paul Watson, who left Greenpeace after he was accused of using methods that were too confrontational. His gang has sunk eight whaling ships and a drift netter, rammed a half-dozen other vessels and blockaded the Canadian sealing fleet.

The Animal Liberation Front also fits the definition. It is an underground network whose agents are unknown. It has claimed between 70 and 100 “liberation” actions at fur farms and research labs since 1981, occasionally using arson and explosives. Another group is the Hunt Saboteurs, whose members disrupt big-game hunts.

Finally, there are the scores of lone monkey-wrenchers who remain unaffiliated. One night at a party in Albion, California, I met an 18-year-old half-Choctaw man who called himself the Crazy Coyote. He was with 15 EFers from a group known as the Albion Nation.

“I used to do some things by myself when I lived over by Tahoe,” Coyote told me, smiling. “I thought I was the only one.” When I asked him what kind of things, he said simply: “You know, monkey-wrenching. That’s why they call me the Crazy Coyote.”

This personal approach to environmental struggle is what Gary Snyder--a poet whose book Turtle Island won a 1975 Pulitzer Prize--calls “the real work”: fighting for a culture where all species have inherent worth and an equal right to exist--not for their value to humans as commodities or recreation but simply because they have an ecological niche, an evolutionary reason to be. Or, if you want to give it a Judeo-Christian twist, because God put them there.

The real work, according to Snyder and others, is to move yourself from an anthropocentric, or human-centered, universe to a biocentric one. This ancient worldview is no foreign import; it has American roots in the work of John Muir, Thoreau, the Transcendentalists and the 1830s wilderness romantics. In 1972 a Norwegian philosopher named Arne Naess coined the phrase “deep ecology,” and it stuck.

The movement now surging around these principles is getting a huge push from science, particularly rain-forest research, which has indicated we are now in the middle of a global mass extinction. At least five such extinctions are known to have happened on this planet. The last one was when glaciers descended over North America during the Ice Age. This one is caused largely by human overpopulation.

I recently saw a roadshow by Australian EFer John Seed, who cofounded the Rain Forest Information Center in 1982, and he told a crowd of about 150 people in Berkeley that a million species of plants, insects, fish and mammals, most of them unnamed, will disappear forever by the end of this century. If Seed’s addition is right, and a lot of biologists seem to agree with his figures, we’ll lose about 400 species a day from now until New Year’s Eve in 1999. Most of what human beings will stoop to “save,” such as the California condor, will become what Dr. Daniel Janzen, professor of biology at the University of Pennsylvania, calls “the living dead”--still there but not able to survive without human intervention.

Seed and other deep ecology evangelists get their gospel from conservation biology. It is a young science, only ten years old, but it is already booming at universities worldwide. As scientists slowly come to understand habitats, the movement adopts their findings as the no-compromise position.

That radical agenda, however, is not limited to direct-action groups. A strong second tier of radicalism is emerging: ecosystem-based wilderness groups that EF cofounder Dave Foreman is now championing as the New Conservation Movement. They distance themselves from what Paul Watson calls “the compromise environmental movement”--the so-called Group of Ten biggies such as the Environmental Defense Fund, whose operatives massage the political reality and field lobbyists in Washington, D.C.

“It would be a big mistake to say that it is simply a matter of tactics,” says Roselle. While a lot of the loud actions by Ef or the Sea Shepherds are meant to grab media attention and sway the American public, Roselle insists that the more important goal must be to change public policy. He says, “You can have radical tactics and not have radical politics. But if you have radical politics you may not need radical tactics.”

Erik Ryberg, an EFer from Missoula, Montana, made the distinction this way: “A difference between [the grass roots] and the mainstream groups is that just about every small grass roots group recognizes that what’s happening is conflict. And we’re here to be one side of that conflict. We’re engaged in a fight. Right now, there’s no avenue for compromise.

“The National Wildlife Federation and the Wilderness Society seem to think that, ‘Well, there’s not really a conflict. We just need to work out a few bugs in the system. We’ll get some more wilderness and everybody will be happy. And we can still drive our jet skis around.’ But you don’t find us trying to work with the Forest Service to get some sort of weird power and weird compromise situation going. Our people say: ‘The Forest Service is operating against the law and it needs to stop. We’re just going to beat it over the head until it realizes that.’”

•

It is May 1992 on California’s north coast. Stars drop through the night air like flaming pins. It’s a little past three A.M., and I’m crouching in the wet grass next to a dying fire, holding a squawking FM transceiver in my hand, writing down what the woman in the tree is singing. The Albion River moves past the base of a knoll; six miles downstream, where the river meets the Pacific, a buoy moans weirdly over the giant trees.

A lovely, nervous woman with an explosion of wild red hair sits on the near bank of the river, listening. Across the river on a 4’x8’ plywood platform rigged 75 feet up a redwood tree on the edge of this riparian meadow, an 18-year-old woman who calls herself Little Tree is singing.

“Why don’t you shut up?” yells one of the Louisiana Pacific security men hired to monitor her vigil, grinding out the night shift with an endless cup of coffee. They’ve had this same exchange pretty much every night since she first went up the tree seven days ago. But Little Tree just seems to get more and more powerful. She sings louder, anyway. She isn’t singing anything in particular, just singing, sometimes breaking off into howls or owl hoots. Sometimes she sleeps, sometimes she lies naked in the sun. The banner twisting under her platform says save the Enchanted Meadow! earth first!

Up the ridge, a couple of men named Emerald and Gray Cloud are on similar platforms deep in the canopy. From time to time we hear the three of them talking to one another over CB radios. Other men--Little Tree’s support team--lie sleeping, knocked out by fatigue and brandy and (continued on page 167)Eco Warriors(continued from page 122) a few fatties of Mendocino County’s finest weed, wrapped in makeshift bedding of coats, sheets of plastic, one blanket.

“When I come down,” she says into the quiet night, “they are going to kill my tree right away. Just because I was in it. I really want to come down. But I can stay here a little longer.”

Little Tree has been trespassing in corporate timber owned by Louisiana Pacific. Because it is illegal for LP’s fallers to risk harming the tree sitters, the three of them are slowing efforts to slash the trees off this ridge. Big wilderness is not at stake here. But a few people in the local community are working to restore the Pacific salmon run in this river, wiped out decades ago by logging, and they want community control of this meadow as a start.

“I tell the security people who are creeping around below me that this is my future that they are destroying,” she said. “I have to watch what’s going to happen to this planet in the next thirty years. It’s going to be my fate.

“I’ve always worshipped differently from mainstream Christian values, but at this point I worship the earth as a living being, just like you and I are living beings. What’s happening is absolutely a sacrilege. We’re killing ourselves.”

EF started the campaign to slow the cut on this coast back in 1983, to preserve the last five percent of the ancient forests left here. That campaign grew into the Redwood Summer of 1990, when thousands of activists occupied the forest for four months. I camped with the EFers on and off in 1990, and it was a weird and ominous summer kicked off by horrifying violence as two organizers were car-bombed.

The bomb’s targets were Judi Bari, an articulate and tenacious union organizer living in Willits and single mother of two daughters, and Darryl Cherney, an EF organizer and songwriter. In May 1990, before the Redwood Summer campaigns had begun, Bari and Cherney met in Berkeley with a movement-support collective called Seeds of Peace, nailing down the Seeds’ commitment to build kitchens and shitters and such at Redwood Summer camps. This meeting was private but not secret.

The next morning they jumped into Bari’s car, and as they drove across Oakland, a motion-activated pipe bomb under her seat blew the car into twisted chunks of metal. Nails wrapped around the bomb were driven into her body. Both Bari and Cherney survived the explosion, but Bari needed more than a year to learn how to walk again.

The suspects are legion, from loggers to timber company operatives to personal enemies. In fall 1992 a federal circuitcourt judge ruled that the two can sue the FBI and Oakland police department for allegedly engaging in conspiracy, false arrest, illegal searches and falsely portraying Bari and Cherney as responsible for the explosion. Meanwhile, both continue their mission, working with the Albion Nation.

Deep ecological consciousness stuns people slowly, one at a time. But once they convert, they rarely go back. This could probably never be a mass movement or a political party. The movement is about personal radicalization, and these people carry the oral history of the dirt under our feet and the battles fought over it.

The ten-year saga is already loaded with tactical lessons and legends--how Dave Foreman got dragged under a truck fighting logging roads in southern Oregon, or how Jumping James Jackson had two trees cut out from under him on a tree sit in Texas. Place names are now symbols: Cache Creek, Wyoming, site of the first EF resistance in 1981; Glen Canyon Dam, mythically targeted at the start of The Monkey Wrench Gang; the ten-year battle to halt a new observatory on Mount Graham, Arizona; the battle to halt logging in Illinois’ tiny Shawnee National Forest.

Add Albion to the list. Little Tree stayed up in her tree two more days. Crazy Coyote mysteriously replaced her and held the tree another week. A man calling himself Dark Moon replaced Emerald and stayed in his tree for 33 days, an EF record. Meanwhile, a lot of other people raised hell by blockading roads and cat-and-mousing with the fallers in the woods. The lumber company reciprocated by suing more than 100 protesters, seeking damages for lost timber revenues. Later in 1992, however, a court injunction stopped the logging.

•

Of course, not all of the eco radicals’ actions are as benign as tree sits. The Earth First Journal, a fat volume issued eight times a year, features a column called “Dear Ned Ludd,” which offers field-tested revisions on the book that started it all, Dave Foreman’s Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkey-wrenching.

It costs thousands of dollars to flush the engine of an earth mover after somebody dumps grinding compound into the oil, and hundreds of thousands to rehab a timber feller-buncher that mysteriously burns in the woods. A couple years back, published estimates of the cost of so-called ecotage in the U.S. reached up to $25 million a year.

Rod Coronado knows ecotage. In 1986 he and fellow Sea Shepherd David Howitt (chief engineer on the stormy mission I was on) sank two whaling ships at anchor in Reykjavík harbor. Iceland was then whaling in defiance of an International Whaling Commission ban.

Coronado and Howitt got jobs at Reykjavík’s meat-processing plant. After casing the operation for a month, the two trashed a computer room that facilitated whale processing. They drove down to the docks, searched the ships, then pulled the sea cocks on two ships while a guard slept on a third. The boats sank while the two men drove to the airport and left the country. Coronado was then 19, Howitt in his mid-20s.

Coronado is underground as I write this, saying he’s afraid of being killed by the FBI. A spokesman for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms calls him a “person of interest,” wanted in connection with a 1991–1992 Animal Liberation Front campaign in which five fur ranches, processors, feed co-ops and research offices were set on fire, resulting in more than a million dollars in damage.

I interviewed him in Venice Beach, California just before he submerged last April, and he gave one of the most eloquent defenses of wrecking shit I’ve ever heard. “We consider any action that prioritizes life over property to be nonviolent,” Coronado said. “And any action where property that is used to destroy life is destroyed, we consider to be the highest degree of nonviolence, because it prevents a greater degree of violence.

“With the level of global awareness that’s been raised toward the destruction of the earth,” he continued, “we feel that people should be connected with direct action. The Native Americans were so spiritually connected to the earth. They defended it and they died for it.

“When people identify the type of direct action that’s necessary, it’s scary. That means we are going to lose people. And people are going to start dying, on both sides of the camp.”

I asked Coronado if he was afraid of that. “I’m not. I’m waiting for it to happen. Because it’s the only thing that’s going to do it.”

Many people in the movement would disagree with Coronado’s philosophy of monkey-wrenching, which includes arson, explosives or any tactic that works (so long as it doesn’t hurt anyone). One who disagrees is Judi Bari, who has already survived two attempts on her life.

“All this male bullshit got saddled onto the idea of deep ecology,” she says with her usual candor. “I think monkey-wrenching has been developed to the limit of its possibilities. The culmination of it was the jailing of the Arizona Five.”

Bari is referring to the monkey-wrenchers caught by an FBI undercover operation in 1989. An agent named Mike Fain spent a year working his way into a small EF action group in Prescott and helped them try to cut an electrical tower that was part of a huge irrigation project. EFer Mark Davis got six years in prison and Peg Millett got three.

The morning after the desert bust, Dave Foreman was dragged from his bed by agents with drawn .357 magnums. He later chose to plea-bargain in order to reduce the others’ sentences. Foreman resigned from Earth First shortly thereafter.

“They failed to learn any lessons from the American Indian Movement or the Black Panthers,” says Bari, referring to the way both were crushed by the FBI. After a moment, she laughs, “I’m including myself in that, by the way.”

•

Whether or not eco warriors agree with Coronado’s all-or-nothing tactics, they have, by definition, experienced a similar spiritual transformation.

In Bill Devall and George Sessions’ book Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered, that transformation is one in which the personal self becomes the much broader Self, which includes the biological community:

This process of the full unfolding of the Self can also be summarized by the phrase, ‘No one is saved until we are all saved,’ where the ‘one’ includes not only me, an individual human, but all humans, whales, grizzly bears, whole rain-forest ecosystems, mountains and rivers, the microbes in the soil, and so on.

We’re wading into spiritual waters here, and all eco warriors are baptized in them to some degree. When the Self-realization manifests itself in ritual, EFers jokingly call it “woo-woo.” The woo-woo tends to get deep at the Round River Rendezvous, their yearly national meeting in the wilderness, at workshops such as John Seeds’ Council of All Being and in the heat of raging eco defense.

During an October action at the Nevada nuclear testing site in the desert about 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, I decided to plunge into those spiritual waters in a sweat bath led by a Native American. As the temperature rose in the dense little skin hut, men offered prayers in turn.

In the midst of all this, I realized that the kid sitting next to me was whispering “fucking faggots” over and over. Then the man currently praying was rattling off statistics on global warming that were undoubtedly part of his canvassing rap, and I just broke. I heard “fucking faggots” again and I plowed my way out the door into the cold night air.

The women in their hut were singing in unison, chanting, laughing. Somehow I was sure their Self-realization was going better than my own. It’s no one’s fault, really. We’ve just forgotten the language for this kind of thing.

•

Mike Roselle, current editor of the Earth First Journal in Missoula, Montana, is hardly an archetype among EFers, especially since about half of them are women. But when I think about them as a species, I always come up with him as a model. He’s beery, unkempt, larger than life, just plain large, red-bearded and rednecked. But it’s mostly his feral eyes, which say “Fuck the rules. I might just decide to go off. Nobody is safe.”

He was looking a bit lost at the new high-rise offices of the Rain Forest Action Network in San Francisco, of which he is a cofounder and board member, pacing the foyer in a smelly Malcolm X T-shirt and blown-out high tops.

We talked about big wilderness in the northern Rockies, an area encompassing northern Utah and Wyoming, western Montana, all of Idaho and eastern Washington. In 1992 EF began a campaign against road-building in Idaho’s Nez Perce National Forest. At the same time, the Alliance for the Wild Rockies uncorked a wilderness bill titled the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act, or NREPA, to preserve 6 million acres of wilderness in Montana and more in adjoining states. It was one of three big Montana wilderness bills that died in the House of Representatives in 1992.

“Many of the people who are in the Alliance [for the Wild Rockies] started out as EF activists,” says Roselle. “They no longer say: ‘I’m an Earth First activist.’ They got short hair. They wear ties. But they have taken the campaign to a whole new level. They’re talking about the same things we [EF] are talking about--big wilderness, wildlife corridors, an ecosystem approach, no compromises, big visionary stuff--and making it real.”

The more moderate politicos in Montana are sure the Alliance will get its ass beat like a gong, but that doesn’t worry Alliance members.

“We don’t think that it’s extreme at all,” says Dan Funsch, program director for the Alliance, representing about 2900 individuals and 300 businesses and groups. “This region is the place where we have the potential to preserve intact ecosystems.

“That’s the problem with our existing system of protected lands. They’re based on a human construct: that we want to preserve samples of these areas. They are relics, museum pieces. That’s totally different from trying to preserve a functioning ecosystem.”

NREPA is a piece of a new wilderness atlas not many people are aware of yet. But they will be. There is a plan that may define wilderness advocacy in the U.S. for the next century.

Spearheaded by Dave Foreman, the staff of the deep ecology journal Wild Earth and conservation biologists Reed Noss and Michael Soulé, the Wildlands Project is a master plan that would define a biodiversity reserve system across North America. Within the next few years it will include a series of maps and conservation projects that identify core wilderness reserves, multiple-use buffers around the reserves and wildlife corridors connecting the reserves.

Noss has already laid out the criteria by which local groups can identify candidate areas and begin the long-term work of preserving their piece of the system. That might mean legislation or lawsuits or direct action.

“What we’re trying to do is marry conservation biology with grass roots conservation activists,” says Foreman, a furry, squinty ex-Marine known for his rousing lecture-circuit orations in defense of wilderness in America and wildness in people.

“Being a conservationist, you are forced to react to brush fire after brush fire,” says Foreman. “Now we’re trying to step back and chart where we’re going. If we had it our way, what is our vision? How would we make the future? I think that we put an agenda on the table that nobody else ever has. That suddenly becomes the new agenda that the conservation groups, government and industry have to respond to. It’s redefining the terms of the debate.”

When Foreman and his comrades talk about big wilderness, they mean big. In his The Wildlands Project: Land Conservation Strategy, Noss writes: “At least half of the land area of the 48 conterminous states should be encompassed in core reserves and inner corridor zones (essentially extensions of core reserves) within the next few decades. I also believe that this could be done without great economic hardship.”

The wise-use people--the anti-environmentalist, pro-development backlash--puke when they read that stuff. But Foreman and Noss are thinking in terms of centuries, or, as Native Americans say, in terms of the next seven generations. That might mean that a rancher with a particularly big spread is encouraged to keep ranching but to will the land to the wildlands system after he and his children die. That way, it doesn’t become a subdivision. Presumably the grandkids can find another line of work.

•

In the summer of 1992, a dozen EFers from Montana and Oregon set up an action camp around a kitchen bus run by the Ancient Forest Bus Brigade, a beachhead for the eco defense of a roadless area in the Nez Perce National Forest near Dixie, Idaho. I was there for the first few days, and it was a frightening prospect. There had never been an Ef campaign in the state, so there was little community support. During a first meeting with the U.S. Forest Service’s Red River District, the rangers were clearly nervous about the ten well-informed hippies in their office.

I left the office with Phil Knight, of the Predator Project in Bozeman, Montana. I said to him, “That was a really great meeting.”

“Those lying bastards,” he replied.

The Red River District had just released the two largest timber sales in recent U.S. history, a total of 76,000 acres, and had begun punching in 145 miles of logging roads. These are areas the Alliance wants to protect, smack in the middle of the largest contiguous chunk of roadless wilderness in the lower 48, between three federal wilderness areas: the Frank Church/River of No Return, the Gospel Hump and the Selway-Bitterroot areas.

The sales are in some of the northern Rockies’ finest recovery habitat for gray wolves, pine martens, lynxes, fishers, wolverines, bighorn sheep, mountain goats and, of course, grizzlies. Grizzlies are the lower 48’s biggest, deadliest predators, and they pose the true test of our commitment: Saving them means honoring home ranges of several hundred square miles per bear. And saving those bears could also guarantee the survival of all the other animals with which they share the range.

I talked about the grizzly bears with wildlife biologist Derek Craighead last November outside his converted log-cabin office in Missoula. “The American people haven’t faced up to the fact that we’re at that critical point where we need to decide: Do we want bears or don’t we? If we don’t, fine. Let’s proceed as if we’re not going to try to save them. If we do want them, then we have to stop the continued release of national forest lands for logging and increased use of bear habitat by recreationists.”

Craighead is an NREPA backer, and he knew about the resistance actions in Idaho’s Red River District. Without that tiny, almost unnoticed EF resistance, another piece of griz habitat would be disrupted for a decade or two. As it was, the EF campaign in Idaho got heavy. As many as 60 armed, camouflaged USFS special agents, the “pot commandos,” tracked and videotaped the EFers in the woods. (“We always knew roughly how many USFS law enforcement there were,” said Erik Ryberg, “because the café in Dixie had been hired out to feed them and we’d count the lunch bags every morning.”)

They stayed for only eight weeks, and there were fewer than ten arrests, as EFers pulled off a tree-sit blockade of the new road, locked themselves to front-end loaders and made a habit of violating Forest Service orders for them to stay off the land. But they cost the USFS $260,000 in additional law-enforcement expenses. More important, the EF campaign put Idaho on the action map, where it never had been before.

•

I asked Derek Craighead for his assessment on the state of the bear.

“I think it’s doomed,” he said quietly. “It’ll survive for maybe four decades, maybe ten decades, but as a permanent, viable population in the lower forty-eight--no, I don’t see enough change in people’s attitudes about putting a real value on grizzly bears.”

Phil Knight had his own, more hopeful griz story to tell: “On my first backpack trip in the West I saw two grizzly bears and walked in their fresh tracks in the spring snow, and it made my hair stand up on end. I got a taste of what it’s like to be around something that I don’t control, and that really keeps the edge on life. As [ex-Green Beret and griz lover] Doug Peacock is fond of saying: ‘If there isn’t something big enough and mean enough out there to eat you, then it’s not really big wilderness.’ That’s attractive to me. And it reflects something I think the human race needs a lot more of: humility.”

“What kind of things? ‘You know, monkey-wrenching. That’s why they call me the Crazy Coyote.’”