Darren Allen

100 Books to Read Before the End

An outsider canon, from Adorno to Grossmith

To be well informed, one must read quickly a great number of merely instructive books. To be cultivated, one must read slowly and with a lingering appreciation the comparatively few books that have been written by men who lived, thought, and felt with style.

Aldous Huxley

There is not enough time in a collapsing world to live a good life in which reading plays some part, and read crap books[1] which is easy to do. Not that you have to always be reading masterpieces of world literature, which can be a bit draining, particularly if you have to work, but when you’ve got time and space to tackle something decent you might want to start here.

The theme is quality. Strange, I know, but the only thing these books have in common is that they are good, which is the only criterion anyone with any sense ever looks for in such a list. There is light relief, here and there, but, for the most part, what follows are the towering literary achievements of our species.[2]

If you want Salman Rushdie, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Hilary Mantle or a Booker Prize winner, find yourself one of the ‘100 books to read before you die’ lists that the broadsheets and bookclubs put out.

Also, there are no black authors here and very few women (one I think). Amazing that so many people need to be reminded of why; because world literature, over the past three millennia, has been overwhelmingly dominated by European and Asian men. Even the woke-Pravda Guardian’s 100 greatest novels were nearly all by The Dreaded White Man. If you have to have an ethnically diverse list again I suggest you go to one where quality is subordinate to keeping people happy. There are plenty of them.

None of this is to say that my subjective taste plays no part whatsoever. Of course it does. On the whole, however, what follows are works which are a lot bigger than me. That’s what quality is, something which brings to the self something which is beyond the self, and the self-reinforcing society which it is tragically a part of.

And so we do have a unifying theme. These books are all, to a greater or lesser extent,[3] outsider literature. Not in a trivially literal sense (e.g. an ethnic outsider), but that which speaks to what lies outside the known, or the knowable, by those who had to struggle to grasp the elusive and the mysterious, and bring them back to a world which is so resistant to it, so resistant to…

1: Adorno, Theodore; Horkheimer, Max Dialectic of Enlightenment. Classic critique,[4] from the Godfathers of the Frankfurt School, of Enlightenment thought,[5] the alienating command-mentality of rationalism that has terminated in a machine-like intellectual world that commodifies individuality and sells it back to us. Extremely tough going — Adorno’s style is, like Hegel and Heidegger’s repulsive — but, still, more page-for-page insights than can be found in 300 pages of most books. Two examples: ‘Under the given conditions, exclusion from work means mutilation, not only for the unemployed but also for people at the opposite social pole. Those at the top experience the existence with which they no longer need to concern themselves as a mere substrate, and are wholly ossified as the self which issues commands.’ and ‘It is a feature of the irrationally systematic nature of this society that it reproduces, passably, only the lives of its loyal members.’ Despite being unnecessarily difficult, not to mention hollow, it’s worth making the effort with Adorno, and with the rest of his work, which cuts right through the shallow either-or fakery of modernism. Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man, something of a follow-up, and not exactly pool-side reading either, is also overflowing with acute observations on the modern condition.

2: Akutagawa, Ryunosuke, Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories. Akutagawa’s stories mix sweet sorrow, grotesque weirdness and the kind of subtlety that makes you warm with hazy pleasure when you detect it — or even (no matter) have it explained to you, as I had to with a few of these. Find yourself, if you can, a small, perceptive Japanese woman to guide you through the hypersubtle loveliness of Green Onions.

3: Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim. Well-behaved and restrained situation comedy. Terribly English, but light, umannered (in fact it represented one of the first concerted attacks on ‘manners’ in the literature of this country) and very funny; the kind of comedy that comes from slowing down social interactions to a quarter speed and remarking on every bizarre nuance that passes between people who are only pretending to like each other. Don’t bother with Amis fils; Amis père didn’t.

4: Balzac, Honoré de. Pére Goriot. Or any of the better ‘La Comédie humaine’ novels (such as Eugénie Grandet). Balzac makes an astonishing contrast to the trivial dilettantes exalted in the literary world of today, providing more insight into the human condition in ten pages than most Booker / Pulitzer winners manage in a career: ‘Eugène was smouldering with that suppressed rage which drives a young man to plunge still deeper into the hole he has dug for himself, as if he hoped to find some way out at the bottom’ or ‘…one of the most unattractive habits of Lilliputian minds is to imagine that others share their pettiness.’ Not as broad as Tolstoy, say, or as profound as Dostoevsky, Balzac’s later works tend to drown in minutia and he’s far too interested in commerce, but for anyone with a stake in the human condition, Balzac deserves to be read as closely as Proust read him.

5: Barfield, Owen. Saving the Appearances. Gets a bit hard going here and there, but is a minor classic of modern philosophy, if a little woolly round the edges. Makes the case that religion and science are forms of idolatry, in that both — despite of course what their followers like to believe — worship creations of the mind.

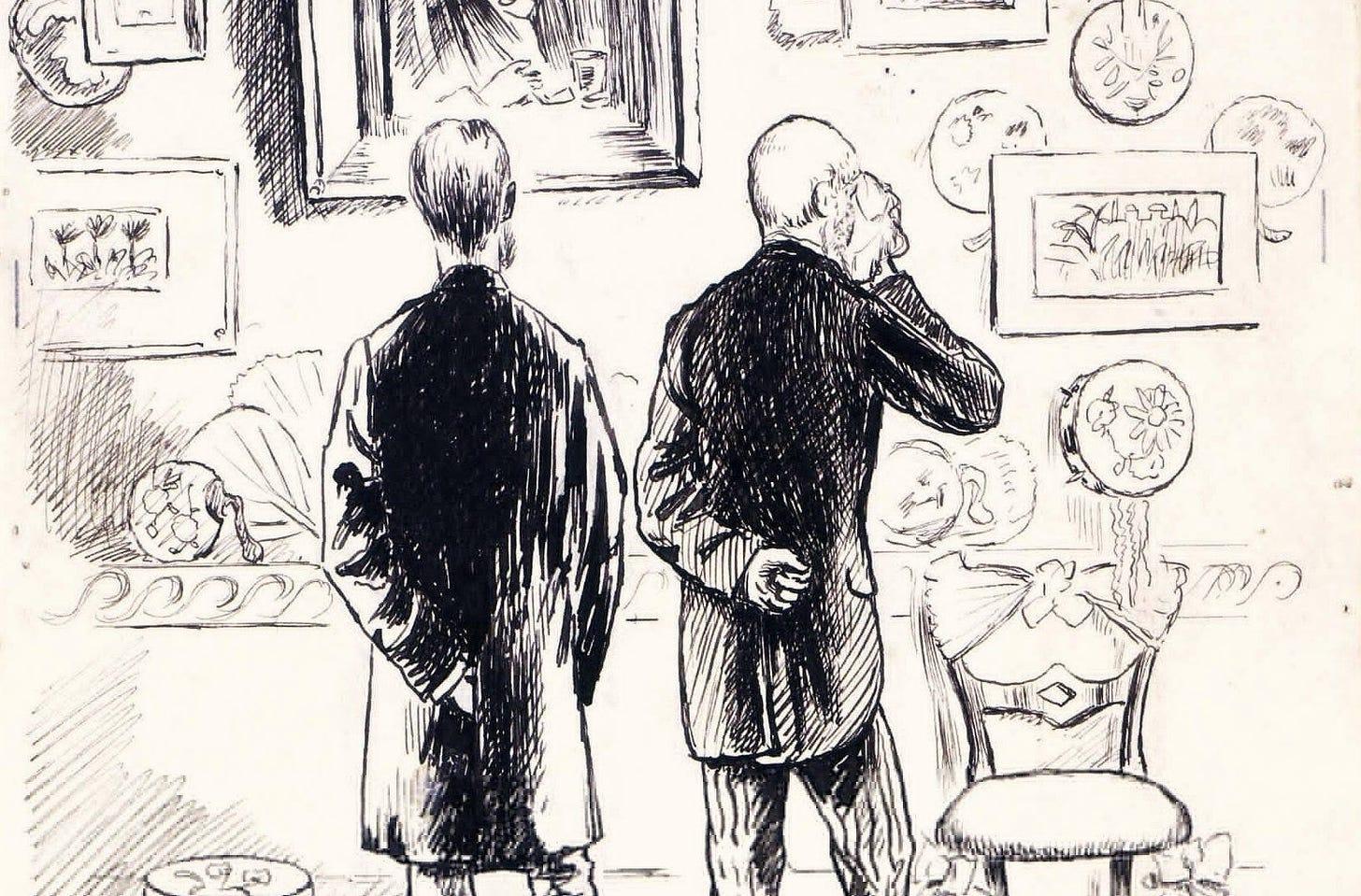

6: Berger, John.About Looking. ‘Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.’ A book about art, and about what is right in front of your eyes when you look at it, inspired by Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, about how the contextual aura of a work of art, which is literally priceless, has been supplanted by mere authenticity, something which you can put a price on. A subversive book because, like all subversive ideas, it is simple and direct; at one point in the teevee series Berger gets children to talk about renaissance masterpieces, and they make far more interesting comments than Brian Sewell or, God help us, Jonathan Jones.

7: Berger, Peter L. The Social Construction of Reality (with Thomas Luckmann). ‘The institutional order embraces the totality of social life, which resembles the continuous performance of a complex, highly stylized liturgy.’ Berger is tough-going. Not Marx or Adorno-level tough, but he does require a bit of effort. Worth it though. Unpicks the deep-structure of society in ways that connect up far flung perceptions into gut-powerful glowing nodes of deep meaning. The Sacred Canopy is also outstanding.

8: Berne, Eric. The Games People Play. ‘Wooden Leg. In this game the player uses his “wooden leg’”as an excuse for not doing something that he — and probably everyone else — knows he should. “Oh, I’d love to go hot-air ballooning with you, but I have this wooden leg, you see’. In extremis leads to ‘the plea of insanity’— “Of course I killed her! What do you expect of someone as fucked up as I am!”’ Plenty of other crackers here. Berne was one of a few marvellous psyche-writers of the 60s and 70s who explored the deep structure of the everyday. Also highly recommended; Erving Goffman.

9: Bickel, Lennard. Mawson’s Will. The most extraordinary tale of polar survival, beating even Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s correctly titled Worst Journey in the World. Douglas Mawson — ‘Awesome Mawson’ as my mum calls him — set out in 1911 to explore 1500 miles of unexplored Antarctica. It goes wrong, then it goes wronger, then there is a massive disaster, then everything gets really bad, then you begin to understand, in the deepest sense, what ‘difficult’ means.

10: Black, Bob. The Abolition of Work. Why work? Bob Black’s essays tend to wander into — I think — self-indulgent point scoring against ‘his enemies,’ but much that he writes is quite inspiring. This essay, rightly the one he is most famous for, is essential reading. I’ve heard that Bob Black fell into line over Covid and has been shaking his fist at the Russkies, so he might have fallen further than I thought, but he’s an elusive cat, so hard to substantiate.

11: Blake, William. Selected Poems. When Thomas Butts, a friend of the Blakes, came to visit them at their house in Lambeth he was amazed to find them both completely naked in the garden. ‘Come in!’ Blake cried. ‘It’s only Adam and Eve, you know!’ Blake’s life and work forms a whole, like the infinity that revealed itself to him in everything he laid his eyes on. I’ve chosen this famous book of poems as a gentle place to start, but everywhere leads directly to everywhere.

12: Blyth, Jonathan. The Law of the Playground. ‘LASER EYES. The glare that a teacher would give any wrongdoing too minor to warrant a verbal ticking off. When receiving laser eyes, pupils can protect themselves by holding a protractor or shatterproof ruler over the eyes, refracting the glare into a harmless rainbow of disapproval’. Abusive, puerile, stupid, revolting, sadistic, deeply, deeply offensive and yet, often, creative and sometimes oddly charming stories from ordinary schools, including a couple from mine. This book will be one of the first on the pyre when the woke generation take charge of the world, so get a copy now.

13: Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Gets a bit boring halfway through, and all the characters are real idiots. Aye! ‘bu’ that ‘fahl, flaysome divil of a gipsy, Heathcliff!’ I quite like Jane Austen — she’s wonderfully observant, within her limited, frigid little world — but for depth and subtlety Wuthering Heights knocks clean white Mansfield Park into a cocked hat. Charlotte Bronté’s work is good too, but a lot neater than Emily’s. D.H. Lawrence rightly condemned the rather sordid wish-fulfilment finale of Jane Eyre as ‘pornographic’.

14: Bryant, Edwin F. (ed.) Bhagavata Purana.10. By far the sexiest religious masterpiece. At one point Krishna duplicates himself into nine-hundred thousand copies of himself in order to make love to as many adoring devotees, for five hundred God-years, until the universe itself ignites. A friend of mine used to be a Hare Krisna, a fairly benign cult from what I can tell, although sexually repressive. He had to wear a little plastic apron in the shower so as not to catch a glimpse of his penis and was told that only when sufficiently spiritually advanced could he tackle the fruity tenth.

15: Bukowski, Charles. Ham on Rye. ‘At the age of 25 most people were finished. A whole goddamned nation of assholes driving automobiles, eating, having babies, doing everything in the worst way possible, like voting for the presidential candidate who reminded them most of themselves.’ Bukowski’s finest, but I have a soft-spot for bildungsroman. Post Office and Factotum are gleaming with dark spit-and-fuck truths too: ‘How in the hell could a man enjoy being awakened at 8:30 a.m. by an alarm clock, leap out of bed, dress, force-feed, shit, piss, brush teeth and hair, and fight traffic to get to a place where essentially you made lots of money for somebody else and were asked to be grateful for the opportunity to do so?’

16: Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God (vol 1–3). Joseph Campbell’s extraordinary review of the entire history of myth. Part 4, modern literature, is not half as interesting though (it’s all about Mann’s dull and pointless Magic Mountain). Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, the model for Star Wars (and countless tiresome Hollywood films since) focuses on male-oriented tales of self-mastery. His Historical Atlas of World Mythology is also a thing of wonder — my coffee table books of choice — although he died before completing them, which I can forgive, but it always strikes me as somewhat inconsiderate of him.

17: Camus, Albert. The Fall. ‘A single sentence will suffice for modern man. He fornicated and looked at his phone. After that vigorous definition, the subject will be, if I may say so, exhausted.’ (adapted) Ever realised you’re not the man you thought you were? This is the story for you! The Outsider is excellent too of course, with one of the funniest opening lines in the history of literature, ‘Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.’

18: Carter, Asa Earl. The Education of Little Tree. ‘He got pretty worked up about it. He said the meddlesome son of a bitch that invented the dictionary ought to be taken out and shot…’ Apparently full of lies and Carter, so they say, was full of shit. But these things really don’t matter with a story like this, which rings so true — in its innumerable details about the magic of nature and the characterful power of people who really live in it — that there has to be truth in it.

19: Céline, Louis-Ferdinand. Voyage to the end of the Night. ‘You don’t lose much when the rented house burns down.’ If you can ignore the questionable sexual ethics of Journey to the End of the Night, and a view of mankind which is unremittingly bleak, you’re in for a treat. The truth, and my God, the language. ‘Poverty is a giant, it uses your face to clean away the world’s garbage.’ On and on it goes, page after page, of unbelievably acute poetic insight, defying the rise of humourless modernism and initiating a rich vein of literature, on the margins of the acceptable canon, which started here, with Céline’s excoriating refusal of the world as he found it. From Céline, via Henry Miller, Jaroslav Hašek, Joseph Heller and Charles Bukowski the principle pleasure and purpose of the novel has, albeit without its grand ambitions, lived on, as a means of giving voice to moral truth in the teeth of a world which has no use for it.[6]

‘The best thing to do when you’re in this world, don’t you agree, is to get out of it.’ You said it Ferdinand; although I’m not sure Céline did get out, really. He pulled himself far enough out of the muck to see it as it is, but no further, which is why his decline was so very shabby.

20: Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quixote (trans. Grossman).

Quixote belongs on this list, but it can drag and exhaust — after nearly a thousand pages of madcap irrealism it feels very much like it’s time to clean the oven — and the ending, in which the eponymous hero abruptly realises the whole thing has been a mistake, is far from satisfying. It’s a road movie, basically, with all the inherent narrative weakness the genre entails. Nevertheless, Like so many classics, Quixote is surprisingly readable and funny, especially the first part, although it does add quite a weight to the old suspended disbelief (seventeenth century Spain seems to have been crawling with noble folk pretending to be shepherds and shepherdesses) and for all the tales of derring do, and the interesting questions the novel throws up on the nature of imagination, it’s really the immortal characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and the love they have for each other, and for the simple goodness of life, which makes the reading so agreeable.

21: Chuang Tzu / Zhuangzi. The Book of Chuang Tzu. ‘You can’t discuss the ocean with a well frog—he’s limited by the space he lives in. You can’t discuss the Way with a cramped scholar—he’s shackled by his doctrines.’ The first and certainly one of the greatest anarchist texts ever written. Quite unbelievably radical. I prefer the Watson translation, (The Complete Works of Zhuangzi) which has an excellent introduction and textual notes.

22: Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. ‘Their bearing, which was simply the bearing of commonplace individuals going about their business in the assurance of perfect safety, was offensive to me like the outrageous flauntings of folly in the face of a danger it is unable to comprehend.’ Dense, dense and super-intense; if somewhat hysterical (is Kurtz really a genius? doesn’t seem like it) and cynical (we’re basically all evil according to Conrad).

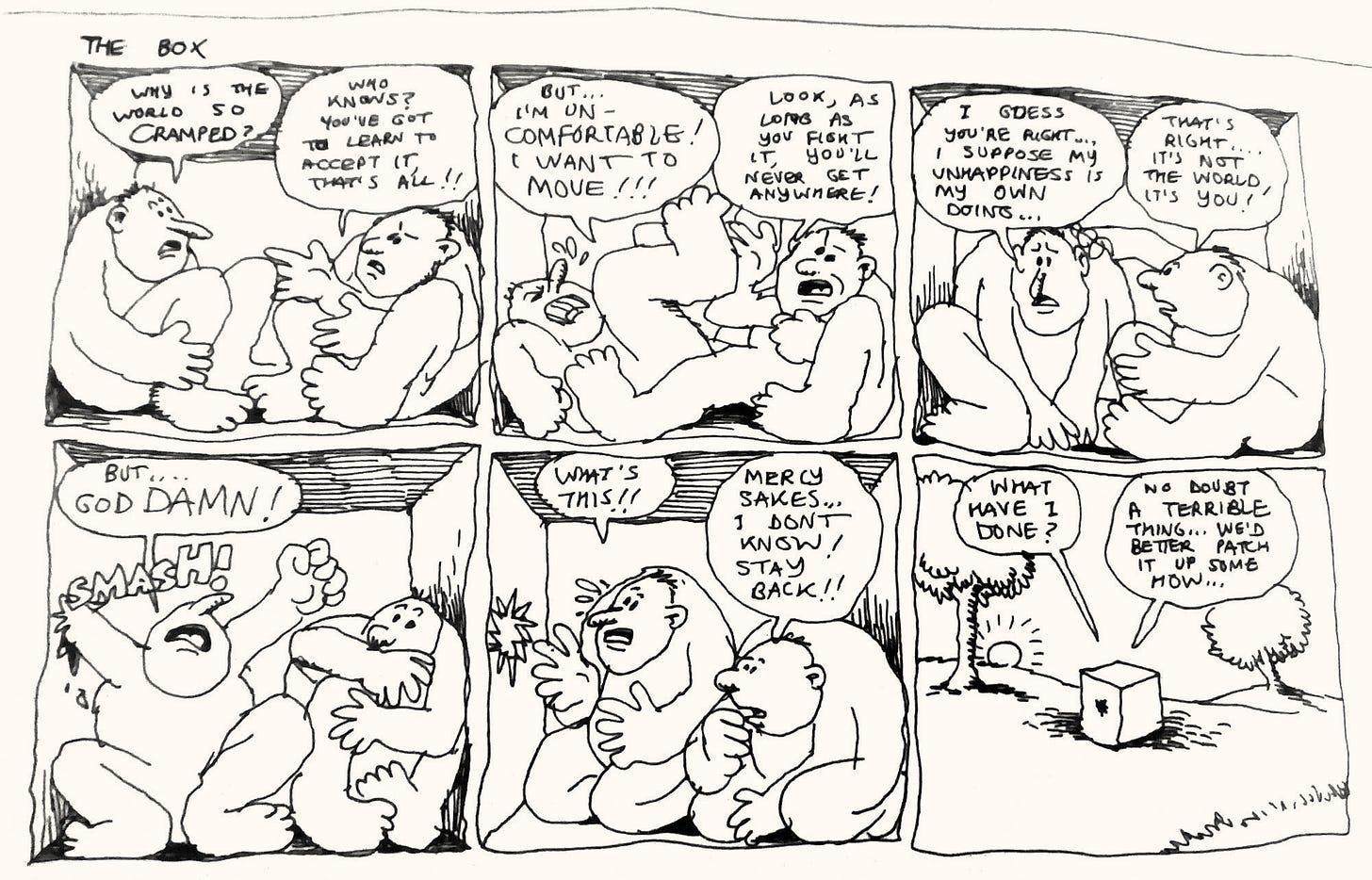

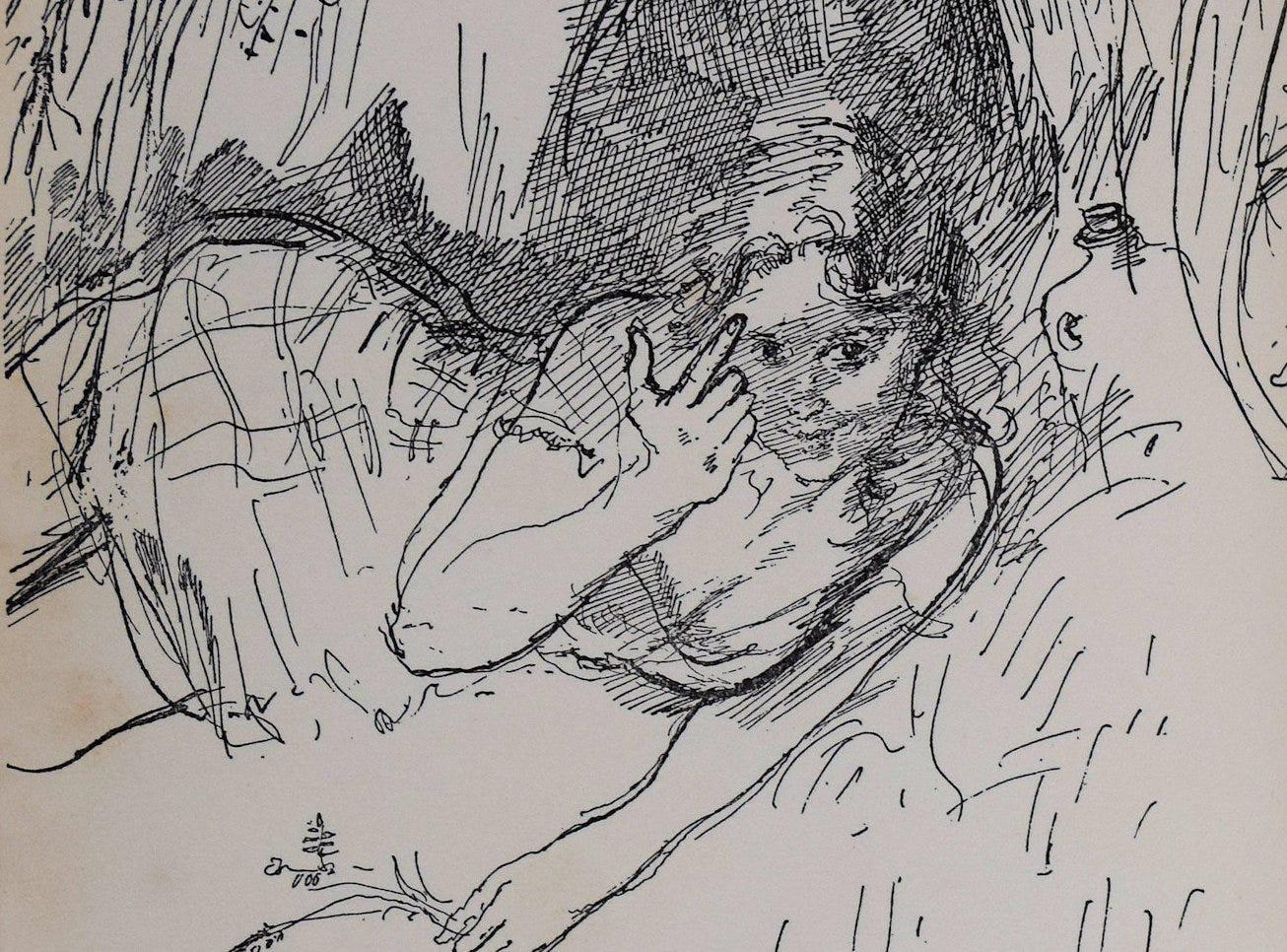

23: Crumb, Robert. Sketchbooks. Mind-blowing — far better than his comics I believe. Like opening the mind of a trickster god and pouring it over a stash of seventies porn mags. A lot of grim prurience, but entertainingly self-deprecating with it and some excellent, caustic observations of the ordinary folk of the world:

24: Dick, Philip K. Valis. ‘Perhaps the universe is in the invisible process of turning into the lord?’ Talking of Crumb, he did a very good account of the strange episode that led Philip K. Dick to write this, the world’s only science fiction autobiography. Dick penetrated the unreality of modern life down to the projector of the shuddering representation the mind makes of it. His hard-gnosticism sends him a bit awry, I believe, but I also think he was the last author to have said something. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch is another reality-bender, and perhaps a little more accessible, as are Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? — a subtle and bizarre enquiry into empathy (‘The only way to determine whether someone was an android was empathy. What separated humans from androids was that androids had no sense of empathy. The difficulty was that very few humans did either.’) and The Divine Invasion, which is Valis part two. Dick is the most modern writer of fiction on this list. If anyone knows of any writer, since 1974, who has said something, do let me know.

25: Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. Dickens’ most autobiographical novel and [consequently, I’d say] one of his most enjoyable. Possibly the most ludicrous ending in world literature, although plots aren’t so very important in Dickens, and Copperfield is, like most of Dickens’s heroes, a real sap with little modulation of character; but that doesn’t really matter either. The real problem with Dickens is that the natural, unifying ground of human character has been vitiated, leaving a sordid carnival of surface personalities and silly names; but, as Terry Eagleton points out, these are an essential backdrop to modern literature, situated as it is in urban spaces that deprive everyone we meet of context, and, in their reflection of a grotesque new social experience, Dickens characters make a profound commentary on modern life, often missed by his detractors. His books are also tremendously entertaining, with a light-hearted buoyancy[7] and eye for telling detail that humanise even the most dreadful scenes. He does tend to go overboard with all this, which can make his stories feel thin and mercurial — not to mention, gawd, so sentimental — but I’d rather read Bleak House than Madame Bovary any day, and consider the great man something of a major influence.

26: Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov (trans. Magarshack, David). And talking of endings, Dostoevsky was all about them. There is a breathless, fanatical feeling to his writing that make you want to get the point, tell us the POINT Fyodor! But, like a kind of sweaty existential-intellectual one-night-stand, after it’s over you don’t always feel you want to get into a relationship. There are some passages in Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Devils and here, in The Brothers Karamazov (particularly the legendary Grand Inquisitor and Russian Monk sections), along with a great many unmatched insights into the perversity of the human spirit, which are, for psychic truth, unmatched in world literature. For the sensory beauty of the sensory life, go Tolstoy, for the darker, inner chambers of the mountain — and for the freedom of the spirit that can only be found at the bottom of the pile — let Fyodor be your guide. You’ll have to wade through a great deal of piffle about ‘we Russians’ and his world is terribly claustrophobic (even the outdoor scenes seem to happen indoors — nature is dreadfully absent from his work) but well worth it.[8]

A related recommendation; Joseph Frank’s biography of Dostoevsky, which is the best literary biography I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a few.[9]

One of the greatest pleasures of my ‘intellectual life’ has been reading The Brothers Karamazov in tandem with Frank’s commentary. The glory!

27: Elias, Norbert. The Civilising Process. Fascinating history of manners, showing how social climbing and new class-stratification tended to repress physicality and spontaneity, leading to what we now understand as civility. Related, and also mind-opening, Phillipe Ariès, author of two masterpieces of medieval scholarship, The Hour of Our Death and Centuries of Childhood.

28: Eliot, T.S. The Wasteland. Along with The Hollow Men; pretty much the unworld as it is. Prufrock is phenomenal too, as is Four Quartets.

29: Ellul, Jacques. The Technological Society. Also Propaganda. Ellul’s work, along with that of Illich and Mumford, is central to understanding the modern world. Here is my account of the same system that Ellul wrote about so eloquently and perceptively, incorporating some of his key insights.

30: Eschenbach, Wolfram von. Parzival. Astonishing story, of penetrating subtlety, but pretty inaccessible these days as most medieval romances are. For a TLDR you might want to read Campbell’s account (see above).

31: Fielding, Henry. The History of Tom Jones; A Foundling. Tom Jones helped sire the English novel, which, for several centuries, was one of our chief contributions to world culture. Here the joy lies in Fielding’s mordant humour, his generous, forgiving view of human nature and his well-designed plots. It’s also a pleasure to inhabit a world in which the farting, shitting, bawdy body is accepted, in which society is, to some degree, ‘integrated’ (the social classes exist, for all their enmities, together) and in which psychological qualities have reality (Honour and Wit and Doubt and so on contend in people’s breasts like wrestlers), all far more human — not to mention medieval — than the remote, shallow, professional world of the Regency and Victorian literature which followed. Tom Jones does suffer from an innately conservative realism, with the suffocating superficiality that realism entails — the characters don’t end up much changed by 900 pages of adventure and neither does the reader — but, for all that, Fielding’s company — which he is prodigal with, frequently taking the reader by the hand in long authorial asides — is as congenial as that of his warm-hearted hero.

32: Forster, E.M. The Machine Stops. Over a hundred years ago Forster predicted the internet and the dystopian hellscape that it started making of the world when mechanisation ceased conveying people to to things and starting conveying things to people. Not just an external hell, but a psychological nightmare, one of constant impatient fear and inner deadness, all outlined here. Science-fiction at its prophetic, chilling finest.

33: Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. At the heart of Foucault too is a horrible, horrible emptiness, but this remains one of the classic works on the schizoid introjection of surveillance and the extraordinarily subtle techniques of controlling people in modern society. Should be read side-by-side with Baudrillard, another ‘postmodernist’, who, for all his emptiness, is also worth exploring and who provides a useful corrective to the idea, in both Foucault and Debord, that power and propaganda are things there which we here can do something about, or even perceive, when we have become the very illusion which oppresses us.

34: Grossmith, George. Diary of a Nobody. Funny late Victorian comedy about an uptight social climber — the status-obsessed forerunner of David Brent, Alan Partridge, Basil Fawlty and Rupert Rigsby. Not hysterically funny, but worth reading. It’s by the heroin-addict actor character in Mike Leigh’s splendid Topsy Turvy, if you’ve seen that. George’s brother did the illustrations…

35: Hesse, Herman. Steppenwolf. ‘In earlier times it was set by painters in a golden heaven, shining, beautiful and full of peace, and it is nothing else but what I meant a moment ago when I called it eternity. It is the kingdom on the other side of time and appearances. It is there we belong. There is our home. It is that which our heart strives for.’ One of the first, great outsider novels (Notes from the Underground preceded it), although the final surrealist section is a self-indulgent cop-out. Colin Wilson makes the point that Hesse didn’t ever really solve the riddle of life that obsessed him, but for posing it, and for entertaining us with the problem of being caught up in it, Hesse deserves his pillow in the palace.

36: Hoban, Rusell. Riddley Walker. Post-apocalyptic wasteland tale set in my neighbourhood. Close to my heart, obviously, although, without wanting to give it away too much, I don’t agree with the implications of the finale.

37: Holt, John. Teach Your Own. ‘A baby does not react to failure as an adult does, or even a five-year-old, because she has not yet been made to feel that failure is a shame, disgrace, a crime. Unlike her elders, she is not concerned with protecting herself against everything that is not easy and familiar.’ How and why to home-school which, having had a little to do with home-schooling, I know is very difficult. With enough fellow families however, in a homeschooling network, it can and must be done.

38: Hughes, Ted. The Hawk in the Rain. Effortless at height hangs his still eye, His wings hold all creation in a weightless quiet, Steady as a hallucination in the streaming air While banging wind kills these stubborn hedges. Apparently Hughes was so handsome that women would throw up when they saw him.

39: Hugo, Victor. Les Misérables. Just a gripping story, dotted with acute observations on the human condition. Don’t watch the musical, or that toothless BBC version that came out recently (only the lead was well cast), just sit down for a couple of months in total absorption (feel free to skip the dull history bits). Also Victor Hugo could fit an entire orange in his mouth.

40: Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. Actually I prefer The Perennial Philosophy and his fascinating essays. I don’t think Huxley was much of a story-teller. Like Orwell, he’s rather dry as novelist, just too much of a intellect. Brave New World is still a nightmarish vision of the present though.

41: Illich, Ivan. Medical Nemesis / Deschooling Society / Disabling Professions. ‘When cities are built around vehicles, they devalue human feet; when hospitals draft all those who are in critical condition, they impose on society a new form of dying; intensive education turns autodidacts into unemployables, intensive agriculture destroys the subsistence farmer, public fora dominated by privately-owned news-media slowly denigrate speech and the deployment of police undermines the community’s self-control. The malignant spread of medicine has comparable results: it turns mutual care and self-medication into misdemeanours or felonies’. Everyone should read Illich — the greatest thinker of the twentieth century — or at least have an understanding of his ideas on the paralysing effects of medicine, high-speed transport, excessive energy, schooling, gender, scarcity and what we call ‘life’. I’ve noticed that a lot of middle-class support for Illich has a curious tendency to eviscerate the core of his teachings, ignore his mysticism (and his book on Gender) and focus on secondary matters. Look twice if a fashionable author describes himself as a fan, because a mark of Illich’s genius, like genius generally, is that it is pretty much always out of fashion. Some people find Illich’s style rather forbidding. I don’t, but I can understand. If you find him hard going I recommend David Cayley’s superb overview; Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey (although you might want to skip the early part of his life, which is of more interest to Christians I’d say).

42: Jansson, Tove. The Moomin Series. The greatest children’s books of all time. See Layla Abdulrahim’s superb Children’ Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation for a guide to why, and why Winnie the Pooh and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory are so damned creepy.

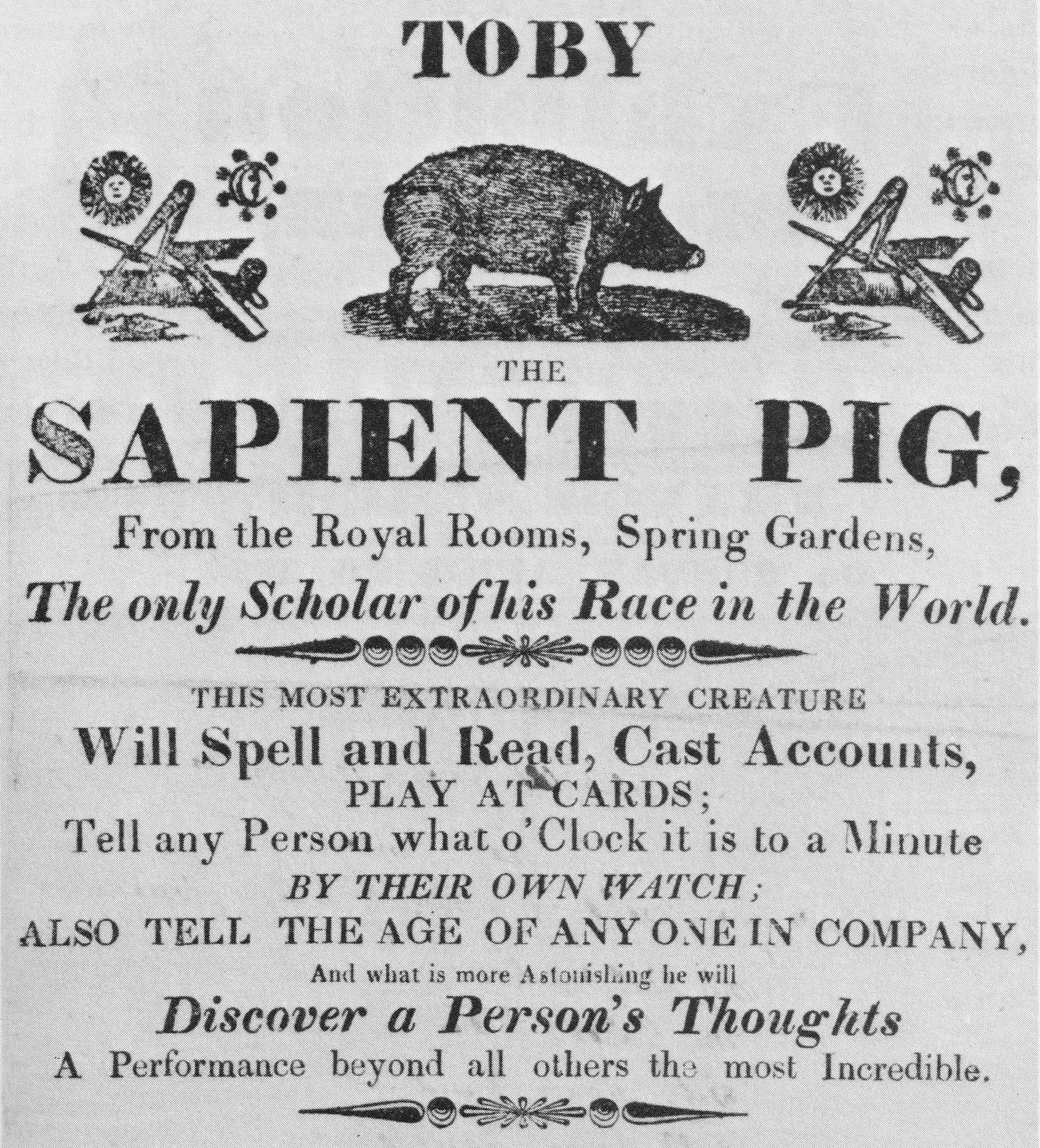

43: Jay, Ricky. Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women. ‘A celebration of the freak, the prestidigitator, the human anomaly.’ There’s a woman here, for example, Thea Alba — The Woman With Ten Brains — who could attach ten bits of chalk to her fingers and write ten different words at the same time. Honest! Very funny photos too. Do take a look at Jay’s work with cards while you’re at it — a 90s BBC documentary is my favourite, but there have been a few since then — for he was a true magician, a man who could turn the world inside out.

44: Jacobsen, Peter Jens. Niels Lyhne. A series of insights into the futile and tragic side of human-love, presented in long, voluptuous metaphors. Very little dialogue, no drama as such, rather one astonishing image after another of a heart dying, dying, dying… dead. Proust lite, if that appeals.

45: Johnstone, Keith. Impro. ‘Suppose an eight-year-old writes a story about being chased down a mouse-hole by a monstrous spider. It'll be perceived as 'childish' and no one will worry. If he writes the same story when he's fourteen it may be taken as a sign of mental abnormality. Creating a story, or painting a picture, or making up a poem lay an adolescent wide open to criticism. He therefore has to fake everything so that he appears 'sensitive' or 'witty' or 'tough' or 'intelligent' according to the image he's trying to establish in the eyes of other people. If he believed he was a transmitter, rather than a creator, then we'd be able to see what his talents really were.’ A masterpiece of psychological joy (except for the useless and rather creepy stuff at the end on masks), and one of the seminal books of my life, although I did a course with Johnstone which was dreadfully disappointing. He just told anecdotes for three days.

46: Kaczynski, Ted. Technological Slavery. Ted Kaczynski, if you don’t know, was a maths genius who went to live by himself in the remote rural Montana, read Ellul, Mumford and Illich, developed a hatred for industrial technology, started sending bombs to academics involved with modern technology, became the FBI’s most wanted man (dubbed ‘The Unabomber’), sent a manifesto (Industrial Society and Its Future) to the the New York Times promising to desist if they published it (which they did, along with the Washington Post), the manifesto was identified by his brother and Kaczynski was arrested and banged up for four thousand lifetimes. The manifesto itself is brilliant. Hardly a literary masterpiece, but a near-faultless critique of modern technological civilisation. When I say ‘near faultless’, actually there is an entire ‘half’ of the modern malaise which Kaczynski fails to address, which I outline here, and which probably accounts for his chilling insensitivity.

47: Kafka, Franz. The Trial. Not terribly gripping, Kafka, I think, and his stories are as hermetically sealed from sensate reality as the characters within them, but, along with 1984, Brave New World and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, The Trial is one of the four prophecies of the modern dystopia we ‘live’ in (albeit Kafka’s critique of the spiritual condition of ‘fallen man’ is more profound than the worldly malaise I point to in 33 Myths of the System). I can’t get over the feeling though, having read all his work, that Franz Kafka was actually a rather unpleasant fellow. His photos are creepy, and tragic. As Walter Benjamin said of him, ‘the experience which corresponds to that of Kafka, the private individual, will probably not become accessible to the masses until such time as they are being done away with,’ which is to say; schizoid insanity. The broken, unresolved narratives (The Castle is unfinished — yet one hardly notices), the nightmarish happenings blandly accepted, the way people and gestures come out of and return to nowhere, the sickly, sordid, disorienting setting; all the same but ever shifting, the emphasis on the frozen image, the overall hopelessness and heaviness… all this speaks of and to the modern mind, but not to the timeless heart.

48: Kant, Immanuel. The Critique of Pure Reason. No, don’t read this! It’s an extremely unpleasant experience; ‘as if an old bony hand is screwing your brain out of your skull’ as Musil put it; much like the feeling you used to have in school when the Maths teacher rumbled past your comprehension leaving you frustrated, lost, angry and alone. The subject matter is amazingly difficult, Kant does no favours to the reader, he gives no examples, he uses the same absurd technical term in different senses, there are massive, labyrinthine sentences that pile clause upon clause, the whole thing is organised into a mind-boggling structure (‘architectronic’ he calls it), and oh God is it dry. An 800 page slog which takes at least a couple of months, doing little else but reading it, to understand; and then only in parts. Speaking for myself, I’ve wrestled some wonderful truths from this book; but I can’t claim to have grasped the whole thing. So why is it here? Because, as Schopenhauer put it, ‘before Kant we were in time, after Kant, time was in us.’ He was the most important thinker to appear in Western philosophy, even if he arrived at his mindblowing conclusions through the most insanely circuitous route, even seemed to draw them, I think, reluctantly and even if, in his horrendous abstraction (Lawrence called him ‘the beastly Kant’) he opened the door unto worlds of philosophical verbiage. You’d be better off reading Schopenhauer, who tidied up Kant’s ideas, refused to flinch from their nutty implications, was infinitely clearer, and far more interesting. If you still want to give Kant a go, start with his easier and kind of simplified introduction, Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics, then read the Critique (the Cambridge translations) hand-in-hand with H.J.Paton’s guide to the first half of the critique which (unlike Kemp-Smith’s more famous commentary) is a masterpiece of clarity and sensitivity. Also recommended for nutters ready to cross, in Paton’s word, ‘the Arabian desert’ of the Critique, is A Kant Dictionary by Howard Caygill, as is the Routledge guide by Gardner.

49: Kerouac, Jack. Dharma Bums. I would hate to live with Kerouac, particularly as he slipped into drunken irrelevance, but there’s no denying the life, the freedom, the wide, wide lifeglory of this book and On the Road.

50: Kenkō, Yoshida. Essays in Idleness (aka The Harvest of Leisure). There was once a monk, in ancient Japan, who only ate radishes. Everyone mocked him, and called him ‘The Radish Monk’, but he continued eating radishes. He said that radishes gave him everything he needed, and that he’d tried other foods, but ‘Radishes are enough for me.’ One day, while the monk was out, two robbers, who had been waiting in the bushes outside his house, ran in to ransack his house. As they approached the veranda two ferocious warriors emerged, clad in full shogun armour, screaming and sawing the air with their swords. The robbers ran off, terrified, past the monk who, just then, was returning. ‘What’s this? What happened?’ asked the monk to the warriors who were now standing guard over his front gate. ‘We are your radishes,’ they said, ‘and we are returning your loyalty to us.’ Whereupon they turned back into radishes. Fascinating 14th century blog. Very short essays about a massive range of subjects and lots of little parables and stories — many of which are delightfully, immortally surreal. The mix of the familiar, the human and the alien is compelling. Also superb, although sparser, more melancholy and more centred on gentle contemplation, is the Hōjōki by Kamo no Chōmei, which Penguin lashed together with The Harvest of Leisure.

51: Krishnamurti, Jiddu. The Impossible Question / Krishnamurti, U.G. The Mystique of Enlightenment Or The Krishnamurti Reader or pretty much anything from Jiddu. It’s all the same from J. Krishnamurti — and yet, somehow never repeated. His essential point is that the mind can never solve its own problems, but the ways he unpicks this observation and applies it to the problems that mind does create, doesn’t seem to get old… That said, I’ve put the two ‘murtis’ together here, because UG is very much an antidote to JK, indeed to the whole spiritual tradition such people represent, slaying sacred cows like some kind of mad spiritual butcher. Enlightenment? Bullshit. God? Bullshit. Love? Bullshit. Meditation? Bullshit!!! As with many teachers and teachings one has to climb a mountain before one can enjoy the summit. The Western mind prefers to get a cable car and then finds, when it gets up there, that it is cold, lonely and insane.

52: Kropotkin, Peter Alekseevich. Mutual Aid. Flawed, like so much anarchist writing, by its Enlightenment-influenced secularity and its dread focus on work (although Kropotkin criticised Marx’s labour theory of value) — anarchism is really a complete philosophy of living, embracing the heights, the depths and the widths, not just social organisation. Still, Mutual Aid, Kropotkin’s answer to capitalist-friendly Darwinism (and socialist statism), emphasising ‘survival of the cooperative’, is an anarchist masterpiece. The Conquest of Bread is good too.

53: Lawrence, D.H. The Rainbow. D.H.Lawrence, that ‘animal with a sort of sixth sense’ was, without question, our greatest novelist and essayist. If, like me, you find the characterless, void of modernist writing suffocating, you might like to know that one author (T.S.Eliot was another) was able to to get beneath character to an actually existing, and quite miraculous, meaning. Scratch beneath Beckett, or Joyce, and your hand pokes through into thin air. Look under the surface of Lawrence, and worlds upon worlds of strange truth reveal themselves. His first great novel, Sons and Lovers, still had one foot in the real world, and is the most approachable of his books. After this, with The Rainbow and Women in Love, he let go of the character that modern readers need to get a hold of a story, which makes reading them a challenge, but in return they — like so many of his extraordinary essays and short stories — take the reader into the underworld that connects us all.

54: Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching (trans. Ellen Chen). ‘Both praise and blame cause concern, / For they bring people hope and fear. / The object of hope and fear is the self / For, without self, to whom may fortune and disaster occur?.’ More than a masterpiece; endlessly revelatory. The most succinct account of the ‘law of heaven and earth’ ever written. Quite a scholarly translation this. There are others more immediately readable, but do your research, as some are (at least according to Chen’s convincing account) downright deceptive.

55: Lee, Laurie. Cider With Rosie. ‘She was too honest, too natural for this frightened man; too remote from his tidy laws.’ Gorgeous evocation of a lost rural world, an England that, in some dim sense, I believe will one day return. Also excellent As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning. Lee was a gentle English Kerouac.

Where have all the Rosies gone?

56: Lee, Richard and Daly, Richard. The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Hunters and Gatherers. One of a large number of fascinating and instructive accounts of how primal folk live. I also recommend The Continuum Concept by Jean Liedloff, Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes by Daniel Everett, Affluence Without Abundance by James Suzman, In Search of the Primitive by Stanley Diamond, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers by Robert L. Kelly, The Forest People by Colin Turnball and Pre-Conquest Consciousness by E. Richard Sorensen.

57: Lermentov, Mikhail. A Hero of Our Time. A book about an absolute bastard. Strange how many of these there are; or not strange at all, as I explain in, How to Be Unlikeable.

58: Levi, Primo. If This is a Man. The greatest holocaust account. Appalling, but Levi’s revelation of humanity, even in actual hell, is a gift to the world. Equally fascinating and inspiring is the companion story The Truce, covering Levi’s long, long journey back home from Auschwitz. This is one of those books that you can give to pretty much anyone on earth, say ‘read that’, and they’ll consume the whole thing in a few days.

59: Lichtenberg. The Waste Books. ‘There are two ways of extending life: firstly by moving the two points ‘born’ and ‘died’ further away from one another… The other method is to go more slowly and leave the two points wherever God wills they should be…’ What? You’ve never heard of Lichtenberg? The compiler of books and books of fascinating, strange and acute philosophical aphorisms, beloved by Schopenhauer, Wittgenstein, Tolstoy, Nietzsche and Einstein? Oh dear oh dear. Off you go! Actually there’s nonsense here, as you would expect from such personal stuff, but, like other early masters of the art of epigram, many gleamful gems which gather in brightness as the books progress and as Lichtenberg aged. Another great aphorist of around the same time was François de La Rochefoucauld whose incredibly cynical ‘Maxims’ on love and self love from one of the darkest periods in human history (the Enlightenment) are well worth a read. Contains such classics as ‘The reason that lovers never weary each other is because they are always talking about themselves’. Finally, a word for the outstanding Faber Book of Aphorisms, edited by W.H. Auden (do try and get the original book design though, from back when Faber produced really beautiful books).

60: Long, Barry. Making Love. Barry Long said some bizarre things, declared himself ‘Guru of the West’, had an alarmingly strident style and, at one point, had a relationship with five beautiful women — but don’t let that put you off! Some of the things he says, particularly in Making Love, Meditation: A Foundation Course and Only Fear Dies were staggeringly original, perceptive and psychologically penetrating. I’ve spent many extraordinary hours in Barry Long’s company. I wrote an eulogy on Long in my collection of essays, Ad Radicem.

61: Maharshi, Sri Ramana. Be as You Are. (ed. David Goodman). Spiritual masterpiece, although it more or less comes down to asking yourself who you are a hundred times a day and replying to the effect that ‘I am reading these words’.

62: Mamet, David. A Whore’s Profession. Mamet turned into a grim reactionary, but around the time these essays were written he was alive to the ‘dreamlife of the world’, wrote some lovely accounts of his early life and, if you’re into writing, some superb technical treatises on the art of film. I also recommend his True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor, which is somewhat one-sided — in his zeal to strip acting of self-absorption he tends to miss a few subtle qualities that actors must divine to do their job — but he sweeps artistic bullshit away with stark panache.

63: Marx, Karl. Capital. I suppose it’s not surprising that Marx got himself his own ism, not to mention all those stone reproductions of his colossal head. We who stand against the system will forever be in debt to his unbelievably astute observations about the nature of the modern world, many of which stand independently of his hard (in both senses of the word) theoretical structures. His penetrating analysis of alienation in the modern world, his unpicking of the subtleties of capitalist exploitation and the almost awe-inspiring moral indignation that fuelled all of this are impossible to gainsay, or to escape. That said, Marx took some of his best ideas from the Anarchist Proudhon, he was wrong about labour (actually energy is the origin of value in the economy) and Marx’s state socialism, planned economics, bourgeois morality, distrust of the peasantry and working class and, of course, his intensely statist and technophilic communism — his state capitalism — are just another kind of oppression, as is his silly determinism, which nobody but lunatic rationalists of the professional class can possibly accept, although Capital, once you’ve got through the first unnecessarily complicated and boring chapters, is a surprisingly engaging read. Generally, I find certain strands of Marxist scholarship more interesting than Marx himself. Fromm, for example, or Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital or Harry Braverman’s superb Labor and Monopoly Capital are Marxist classics, and essential reading for criticising capitalism, but you’d be better off reading George Woodcock’s Anarchism for a history of more sensible (if tragically incomplete) solutions. Read my wildly popular critique of Marxism here.

64: Mascaro, Juan (trans.). The Upanishads. ‘In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as the Upanishads’ wrote Schopenhauer. It’s a bit repetitive, which is to be expected, given that it was transmitted orally, and there are some weird stories, but many bellymind treasures herein. ‘You cannot see That which is the Seer of seeing; you cannot hear That which is the Hearer of hearing; you cannot think of That which is the Thinker of thought; you cannot know That which is the Knower of knowledge. This is your Self, that is within all; everything else but This is perishable.’

65: Matsuo, Bashō. On Love and Barley (trans. Stryk, Lucien). ‘About the pine, learn from the pine; About the reed, learn from the reed.’

66: Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. I read Moby Dick a long, long time ago, when I was twenty five and sick and miserable in Indonesia. Melville’s immense heart kept me tethered to humanity and surrender to my fate. His fate was to be ignored while he was alive and then to have his gorgeous, meaty style, and biblical syntax, emulated by every ‘serious’ American author of ‘muscular prose’ for the next thousand years (the execrable Cormac McCarthy, for example). Melville’s earlier tales of derring do, Typee and Omoo are also fantastic reads, and far more accessible, and I’m a big fan of his later short stories, Bartleby, Billy Budd and Cock-a-Doodle-Do!

67: Miller, Henry. The Colossus of Maroussi. ‘It sounds like defeatism to say to the young of our day: “Do not rebel! Do not make victims of yourselves!” What I mean, in saying this, is that one should not fight a losing battle. The system is destroying itself; the dead are burying the dead. Why expend one’s energy fighting something which is already tottering? Neither would I urge one to run away from the danger zone. The danger is everywhere: there are no safe and secure places in which to start a new life. Stay where you are and make what life you can among the impending ruins. Do not put one thing above another in importance. Do only what has to be done—immediately. Whether the wave is ascending or descending, the ocean is always there. You are a fish in the ocean of time, you are a constant in an ocean of change, you are nothing and everything at one and the same time. Was the dinner good? Was the grass green? Did the water slake your thirst? Are the stars still in the heavens? Does the sun still shine? Can you talk, walk, sing, play? Are you still breathing? If you can answer yes with your entire being, then you offer the finest, most lasting and most joyous rebellion of all.’ Actually this quote is from Stand Still Like the Hummingbird, a collection of Miller’s essays, but it could come from pretty much anywhere in Miller’s work, which overflows with joy before the storm, or, as Orwell, a great admirer, put it, ‘fiddling while Rome burns, but, unlike everyone else, facing the flames.’ Miller had, on balance, a pretty terrible attitude to women and sex. Not a lot of tenderness, that’s for sure, and his lapses into heartless vulgarity are really impossible to forgive — no wonder feminism would have nothing to do with him. He was also self-centred (but what great man isn’t?), irresponsible and, as Orwell pointed out, without much imagination and given to frothy, florid flights of fancy with, actually, very little content. But. It cannot be denied Miller’s torch burned brighter than just about every other author of the twentieth century, and it still illuminates.

(Subscribe to continue reading the descriptions.)

68. Useful Work versus Useless Toil by William Morris

69. Technics and Civilization by Lewis Mumford

70. The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil

71. Botchan by Natsume Sōseki

72. The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs by Friedrich Nietzsche

73. Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell

74. Tertium Organum: The Third Canon of Thought: A Key to the Enigmas of the World by P.D. Ouspensky

75. Struggle of the Magicians: Exploring the Teacher Student Relationship by William Patrick Patterson

76. Trafic de chevaux: Nouvelles by Jacques Perret

77. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time by Karl Polanyi

78. Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain by Russell Ash

79. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Oliver Sacks

80. Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature, and Thought by Louis A. Sass

81. The World as Will and Representation: Volume 1 by Arthur Schopenhauer

82. King Lear (Arden Shakespeare: Third Series) by William Shakespeare

83. Kolyma Tales by Varlam Shalamov

84. Fury On Earth: A Biography Of Wilhelm Reich by Myron R. Sharaf

85. Audition: Everything an Actor Needs to Know to Get the Part by Michael Shurtleff

86. The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler

87. East of Eden by John Steinbeck

88. The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct by Thomas Szasz

89. The Gospels: Authorized King James Version by W.R. Owens

90. Walden by Henry David Thoreau

91. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

92. The Underground Sketchbook of Tomi Ungerer by Tomi Ungerer

93. The Rāmāyaṇa by Vālmīki

94. Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

95. The Complete Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson

96. The Soul of Man Under Socialism and Selected Critical Prose by Oscar Wilde

97. The Outsider by Colin Wilson

98. Philosophical Investigations by Ludwig Wittgenstein

99. Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis

100. Wolf Solent by John Cowper Powys

101. NonNonBa by Shigeru Mizuki

[1] Or, to put it another way, ‘A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones — for life is short.’ Arthur Schopenhauer.

[2] Those I have discovered at any rate. I’m not claiming this list is somehow definitive, which would be preposterous.

[3] Sometimes, it must be said, much lesser.

[4] Actually ‘dialectic’, or description of the evolving relationship of opposing forces.

[5] Although the authors, being Marxist materialists, did not actually reject the Enlightenment itself.

[6] I flatter myself that my Drowning is Fine continues this marginal tradition. Judge for yourself.

[7] Eagleton writes; ‘Distinguished visitors to Dickens’s home would smile indulgently to see the great man crouched on the carpet playing with his children, only to realize after a while that he was taking the game with disturbing seriousness and appeared notably reluctant to break off.’ Few authors have understood children and childishness as well as Dickens. Dostoevksy was another. Lawrence too could write a child.

[8] Dostoevsky also presents one of the most profound and penetrating critiques of materialism and utilitarianism in literature.

[9] I’ve heard that David Magarshack’s biography is more incisive and (obviously) shorter, but I can’t find a copy.