A text dump on David Skrbina

Double life: Academic David Skrbina revealed as prolific antisemitic author

University of Helsinki researcher suspected of links to prominent antisemitic figure

Links between Skrbina and Dalton

University of Helsinki terminates contract with alleged antisemitic researcher

David Skrbina on Ted Kaczynski & Luigi Mangione

David fucks up and reveals his alt identity — 39 minutes in

Ted Kaczynski & Technological Slavery | Know More News w/ Adam Green feat. David Skrbina PhD

[Jewish World Government Conspiracy]

CHAPTER 3: WHY THE JESUS STORY IS FALSE

(1) The Problem of the Evidence

(2) The Problem of the Chronology

Jewish Attitudes, Within and Without

Tacitus and the Second Century AD

CHAPTER 5: RECONSTRUCTING THE TRUTH

CHAPTER 6: TAKING STOCK, LOOKING AHEAD

APPENDIX B: A CRITIQUE OF ASLAN’S ZEALOT (2013)

Debate: Is Jesus (Isa) a HOAX? David Skrbina v. Peter Williamson at Wayne State University

The Jesus Hoax Wars — Know More News w/ Adam Green feat. David Skrbina PhD

Unraveling the Mind of Richard Spencer — Know More News w/ Adam Green

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 338: Ted Talk

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 536: David Skrbina on Ted Kaczynski

When did Dr. Skrbina start corresponding with Ted?

What does Dr. Skrbina think of Ted’s manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future?

Ted was concerned with human happiness, but wouldn’t crashing the system create unhappiness?

Can technology be harnassed in a good way?

How regulating tech would require a global government

What level of tech did Ted accept?

Do people want to destroy tech to conquer white people? And how good a mathematician was Ted?

What about the experiments performed on Ted at Harvard?

On uploading your brain and living forever

Can our solution to tech be a sophisticated, mixed approach?

Did you ever talk to Ted about Savitri Devi?

Which thinkers on tech influenced Ted?

Was Ted influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche?

Did Ted ever read Frank Herbert’s Dune?

Will Ted be thought of as a prophet?

Did Dr. Skrbina maintain contact with Ted?

Will Dr. Skrbina ever publish his correspondence with Ted?

How can we follow Dr. Skrbina’s work?

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 537 David Skrbina on Ted Kaczynski, Part 2

Was Ted’s untechnological vision utopian?

What are your thoughts about the media’s reaction to his death?

Couldn’t Ted have just started a blog?

Mixed book review from a neo-nazi

Catching Up With the Unabomber. When Does the End Justify the Means?

#14 – SOF Cast — David Skrbina on Ted Kaczynski, Technological Slavery & Eco-Theology

God and the Problem of Kerrville

Nature is Eugenic, Technology is Dysgenic

Objections Sustained: Why David Skrbina’s Arguments Still Fail

Eugenics on Trial in Japan and Korea

Universalizing Human Selection

Eugenics Redux: Reply to Unz and Alexis

History Speaks Debates a Holocaust Conspiracist

Opening Statement of History Speaks

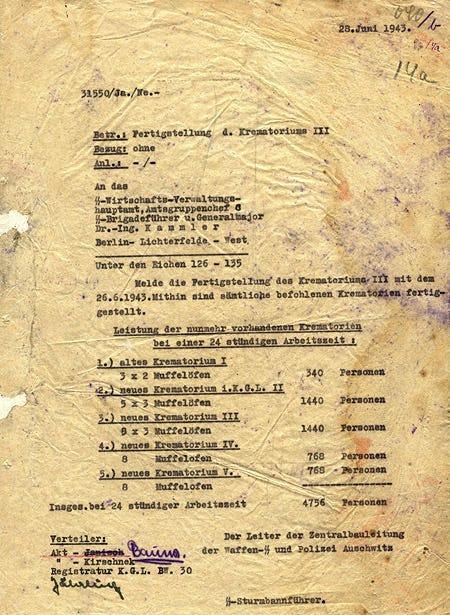

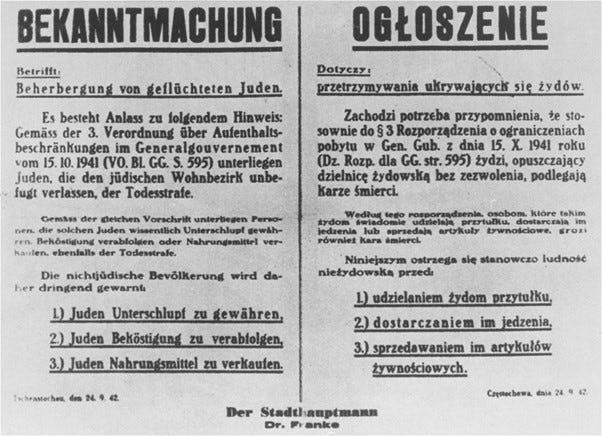

Stage 2: Kulmhof, Sobibor, Belzec, and Treblinka II

Debunking the Three Core Premises of Holocaust Denial

Opening Statement of Thomas Dalton

History Speaks Replies to Thomas Dalton

Is the Six Million Figure Sacrosanct?

Decades of Headlines about ‘Six Million Jews’ Prior to the Holocaust?

Gas Vans and the “Diesel Question”

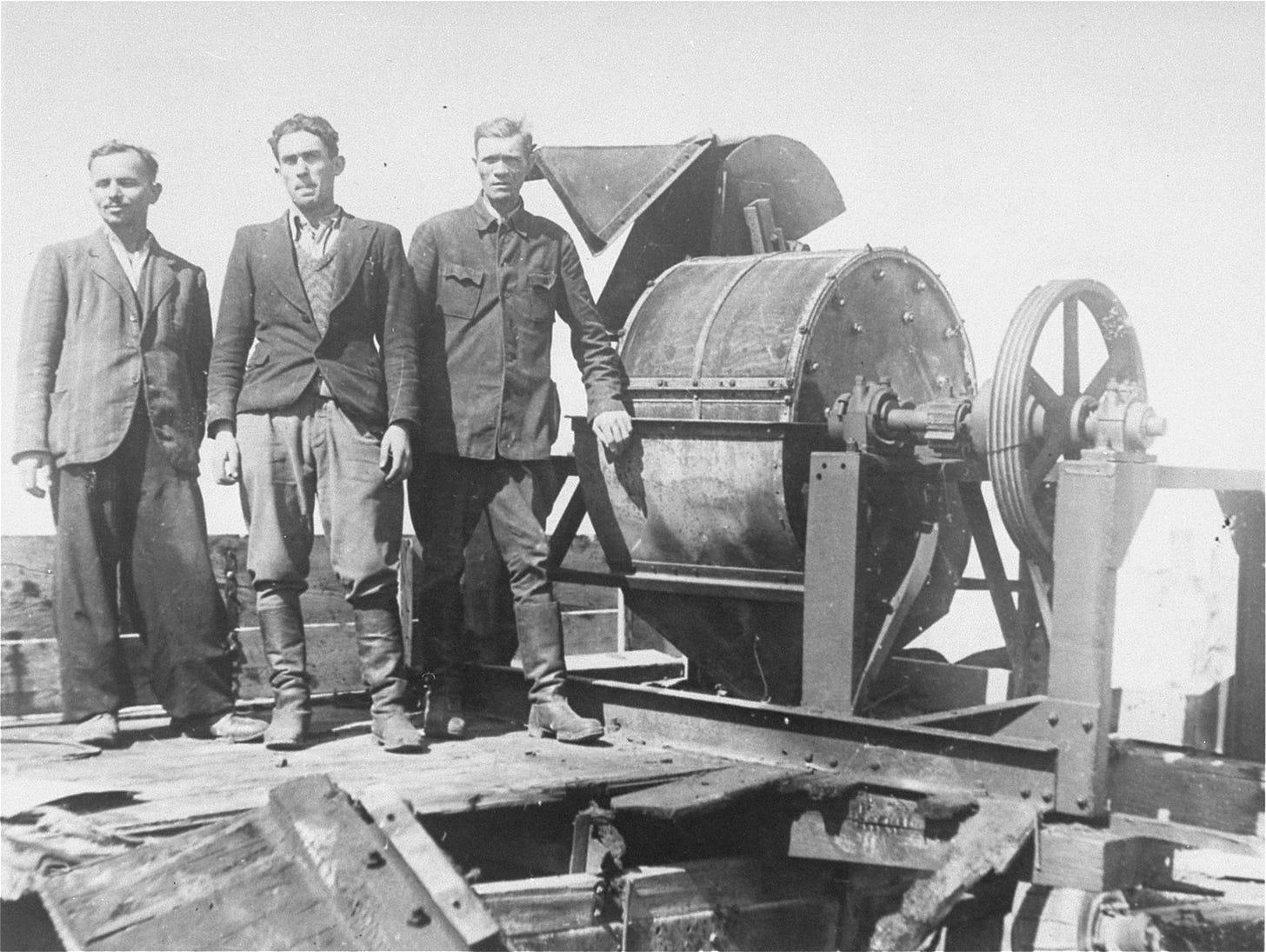

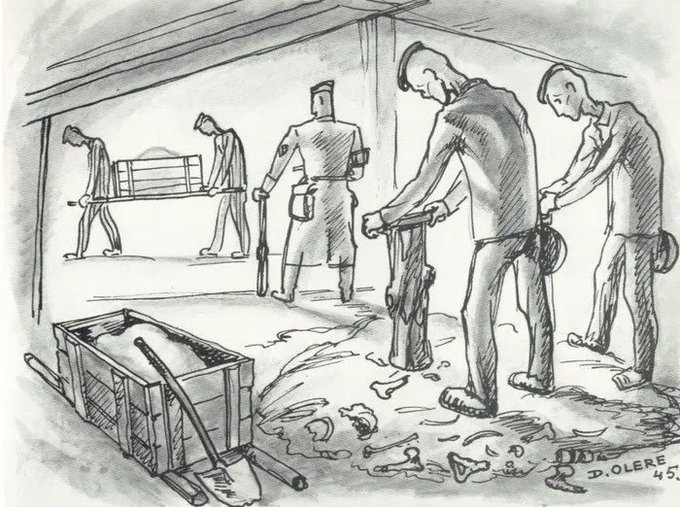

Body Disposal at the Reinhardt camps

Disposing of Bones, Teeth, and Ashes

Thomas Dalton Replies to History Speaks

Reply to Opening Statement and First Rebuttal by Thomas Dalton

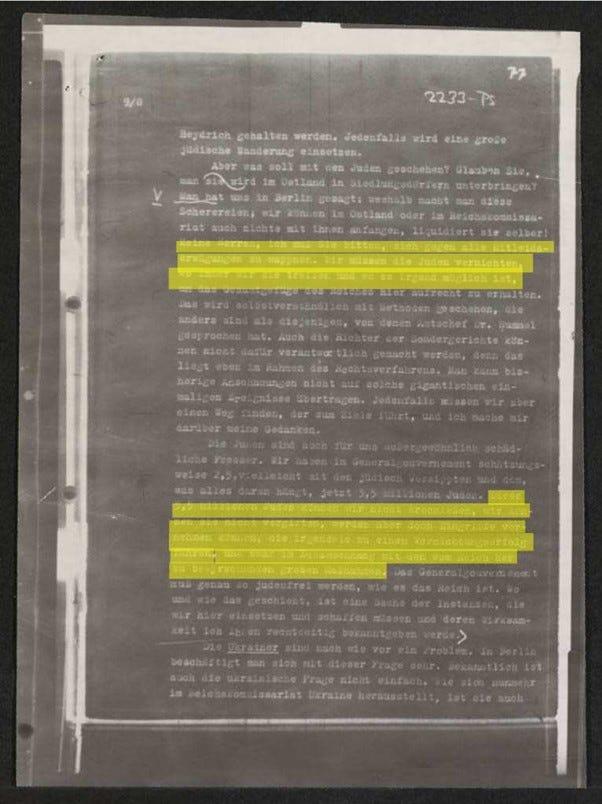

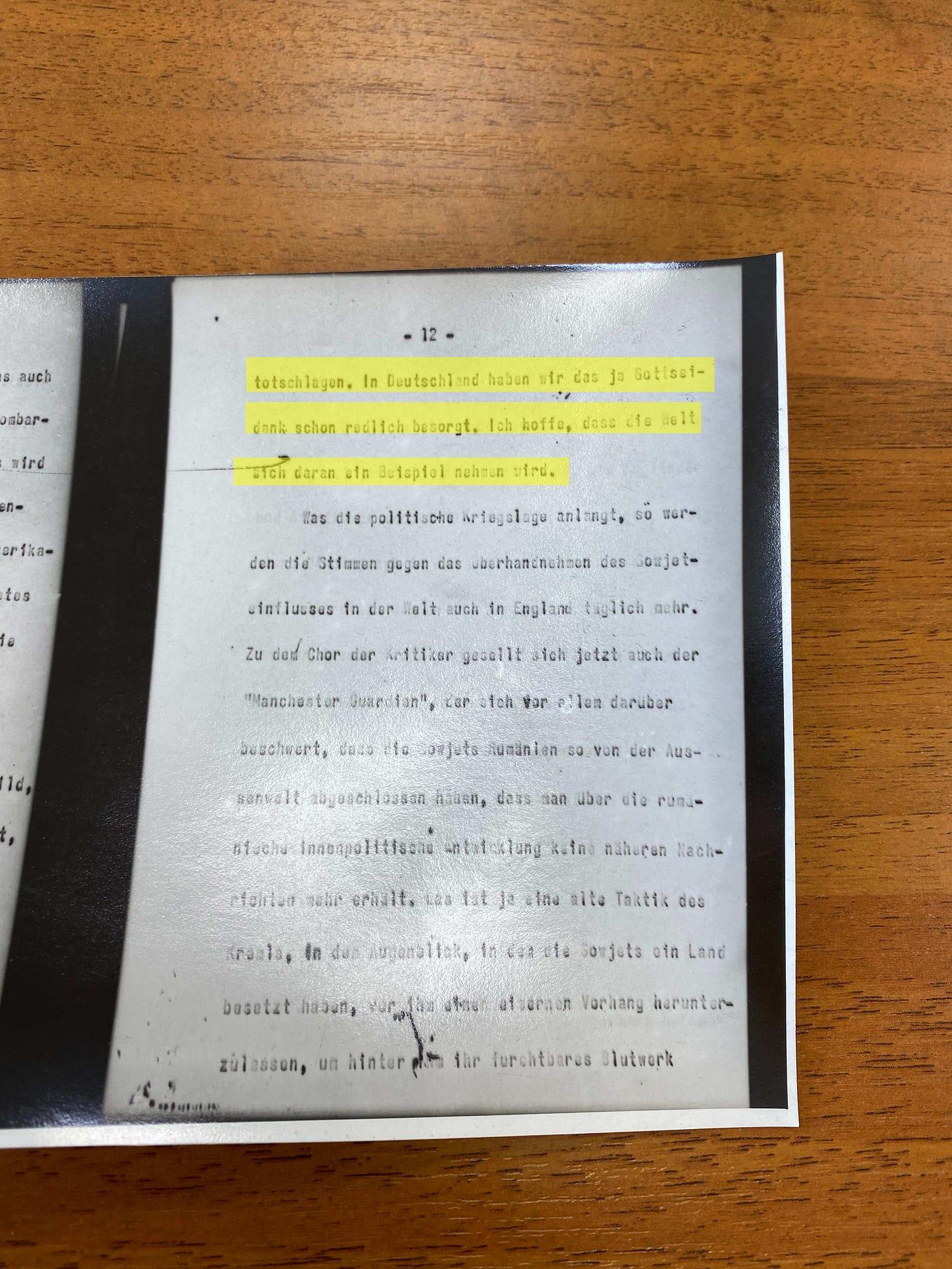

Confessions, Documents, Policies

But What About those “Six Million”?

Final Rebuttal by History Speaks

A ‘Dodgy’ Rebuttal: Kulmhof and Aktion Reinhardt

Reinhardt Camps: Incomplete Physical Evidence & Resettlement Theory

More Dodging: This Time on Auschwitz

Rebutting Dalton’s Auschwitz Arguments

Still More Dodging: German Policy and Quotes from German leaders

On Dalton’s Wordplay and Selective Quoting

A Dodge by History Speaks? Disposal of Ash and Human Remains at the Camps

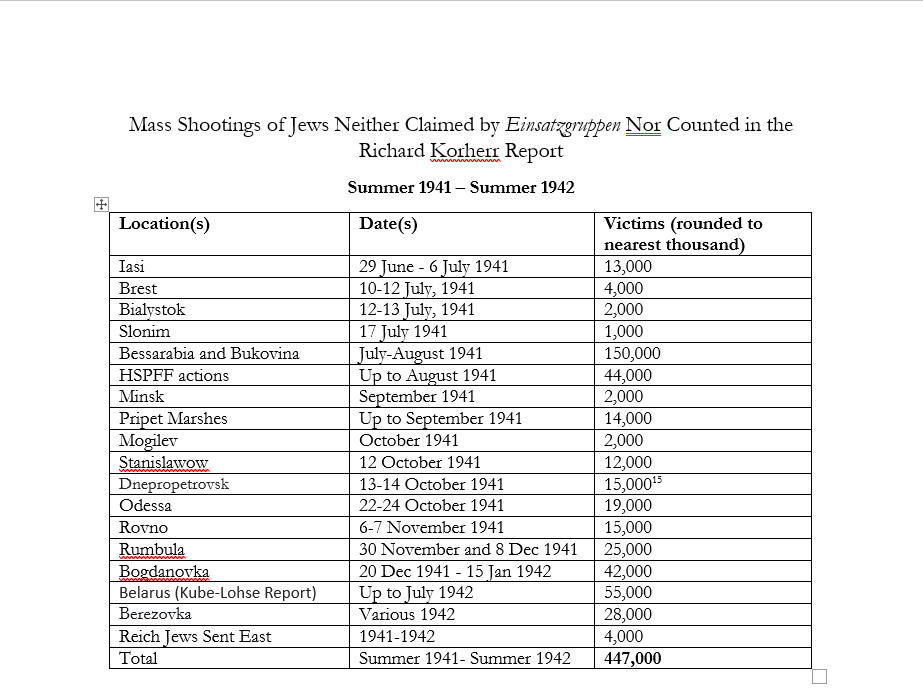

Appendix: Statistical Questions

More Than Five Million Total Deaths

A Recurring Issue: The Problem of the ‘Disappeared’ Jews

Introduction

Double life: Academic David Skrbina revealed as prolific antisemitic author

Date: March 17, 2025

Source: <https://www.splcenter.org/resources/hate-watch/academic-david-skrbina-revealed-antisemitic-author>

Authors: Hatewatch Staff

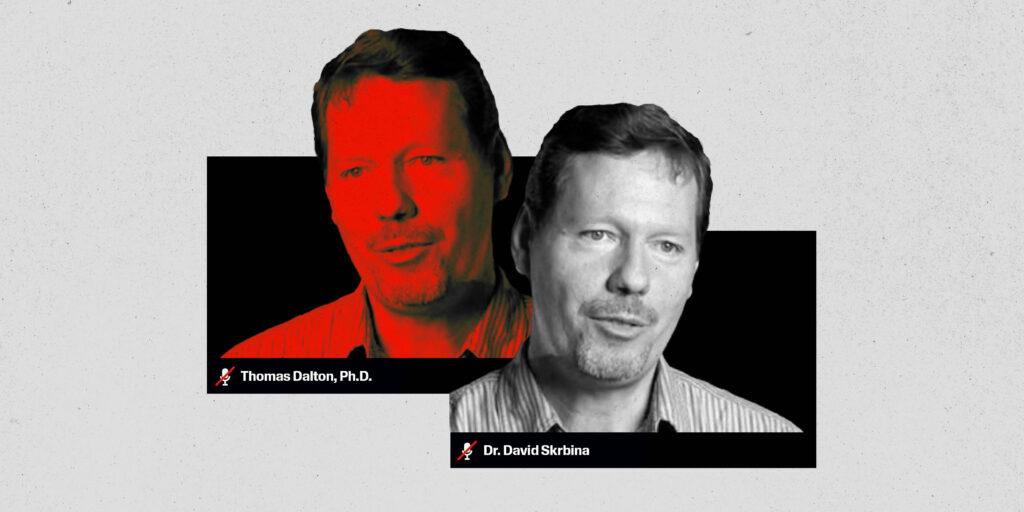

David Skrbina, Ph.D., a former University of Michigan-Dearborn professor and academic, has been revealed as the man behind the persona Thomas Dalton, Ph.D., a prolific antisemitic author and Holocaust denier.

On a Dec. 20 episode of antisemite Kevin Barrett’s podcast “Truth Jihad,” Skrbina inadvertently confirmed his dual identity. Until now, Skrbina has distanced himself from the dissemination of virulently antisemitic propaganda. “Dalton” is a frequent contributor and key figure in Clemens & Blair Publishing, a book producer that the Southern Poverty Law Center has labeled as an antisemitic hate group. His email is prominently listed on the group’s contact page, and his personal website is directly linked from Clemens & Blair’s homepage. Dalton is so prolific within the group that its website features a dedicated category to filter books he has authored or edited.

Revealing that Dalton and Skrbina are the same person underscores the importance of exposing those who cloak extremist ideology in academic authority. Unmasking Dalton exposes efforts to lend a facade of legitimacy to white supremacist and Holocaust denial views, a technique that these movements rely upon to spread their propaganda.

Dalton’s works include not only original writings, but also edited and republished versions of several infamous antisemitic texts, including Martin Luther’s On the Jews and Their Lies, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, Henry Ford’s The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem, and Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Across his publications, two central themes emerge: a relentless effort to blame Jewish people for the world’s problems and a concerted attempt to rehabilitate the image of the Nazis, including Hitler and Joseph Goebbels.

Dalton has been recognized as a leading author by Michael Santomauro, who has led antisemitic hate groups Clemens & Blair and, until his recent split with prominent Holocaust revisionist Germar Rudolf, the Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust (CODOH). In a 2016 interview with Holocaust denier Jim Rizoli, Santomauro said he assisted Dalton in publishing his Holocaust denial book titled Debating the Holocaust: A New Look at Both Sides.

Much of the work attributed to Dalton has been compared online to Skrbina’s work for years, with commenters noting similar themes and mentioning them in the same extremist forums.

Skrbina has publicly reviewed and critiqued his own pseudonymous work and likewise has used his Dalton persona to comment on his work under his real name. On the antisemitic website The Barnes Review, Skrbina wrote a review of Dalton’s book The Jewish Hand in the World Wars, where he refers to the book as “thought provoking” and an “invaluable resource.”

Skrbina praised Dalton for explaining “how Jewish revolutionaries were active in Berlin and Munich, ultimately bringing down that nation from within, and then coming to dominate the postwar Weimar government,” and that Jewish monolithic control and influence have been responsible for “virtually all wars” in modern American history. Skrbina has used his position as a professor of philosophy over the past 20 years for various universities — including Michigan State University and the University of Michigan — to lend credibility to his alter ego’s antisemitic works.

Skrbina accidentally revealed his identity during a chaotic moment on Barrett’s show. Barrett mistakenly identified Dalton as Skrbina when Skrbina accidentally logged onto the call under both identities. During the segment, Barrett discussed seeing both names together and speculated that they were the same individual. During the confusion, Barrett said, “That’s David’s picture, with Thomas Dalton’s moniker. … Thomas Dalton is the famous author of … Debating the Holocaust.” Barrett removed Skrbina’s “Dalton” profile from the chat, referring to him as “David AKA Thomas Dalton” with a chuckle while Skrbina simply let Barrett remove the Dalton profile.

Barrett concluded the interaction by stating, “The ADL is going to go after you now.” An audible feedback echo during the interview caused by Skrbina being logged in as himself and his pseudonym at the same time further exposed the link between Skrbina and Dalton.

Barrett himself has spread antisemitic conspiracy theories and written for the white nationalist publication The Unz Review. Following public critique of his antisemitism, his employer at the time, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, expressed disapproval with provost Patrick Farrell issuing a statement in 2006 that the university “does not support statements that are anti-Semitic, and we do not endorse Mr. Barrett’s personal views.”

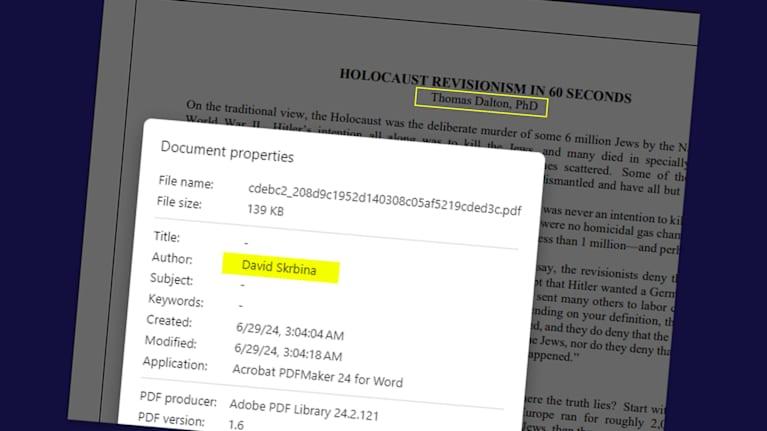

Additionally, two PDF files prominently displayed on Thomas Dalton’s website, titled “Holocaust Revisionism in 60 Seconds” and “Tactics of Organized Jewry in Suppressing Free Speech,” point to Dalton and Skrbina sharing an identity. Both files specify that Dalton was their author or editor. The SPLC examined the publicly available metadata for the two files, which indicated both were created using the same platform, and both clearly identified Skrbina as their creator.

Skrbina did not respond to a request for comment from Hatewatch.

In 2001, Skrbina successfully defended his dissertation at the University of Bath and achieved a doctorate in philosophy focusing on technology, eco-philosophy and environmental ethics. His initial research focused on panpsychism, a concept that suggests “the theory that mind exists, in some form, in all living and nonliving things — in consideration of the nature of consciousness and mind.” He went on to be a lecturer at the University of Helsinki in Finland from 2020–23. Earlier, he was a professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn from 2003–18. He also held positions at the University of Ghent in Belgium in 2008, Michigan State University in 2011 and Eastern Michigan University from 2006–07.

Skrbina also wrote several pieces about the existence of Jesus, criticisms of Israel, foreign wars and questioned the continued existence of the United States. Skrbina corresponded extensively with Ted Kaczynski, known as the “Unabomber,” who killed three people and injured 23 others with mail bombs between 1978 and 1995. Beginning in 2003, Skrbina exchanged approximately 150 letters with Kaczynski, delving into critiques of technological society. This collaboration led to the publication of Technological Slavery, a collection of Kaczynski’s writings that Skrbina edited and introduced. Through this work, Skrbina has actively promoted and legitimized Kaczynski’s extremist anti-technology ideology, amplifying his dangerous views to a wider audience.

In an interview discussing Skrbina’s book The Jesus Hoax, he claimed that the story of Jesus was a deliberate fabrication by St. Paul and his followers to weaken the Roman Empire — an argument that leans into antisemitic tropes about Jewish manipulation of historical events. The book also attacks modern technology, echoing Kaczynski’s radical anti-industrial rhetoric.

Skrbina’s portfolio of antisemitic literature, written under his pseudonym, was produced during his tenure as a professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan-Dearborn (2003–18) and later while at the University of Helsinki (2020–23). His 2016 Holocaust denial book, referenced by Santomauro in the Rizoli interview, was published by the now-defunct Castle Hill Publishers, a company notorious for producing Holocaust denial material.

Various white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizations have cited Dalton’s expertise and writings to support their hateful efforts. For instance, the National Vanguard, a white nationalist group, has referenced Dalton’s work in its publications. Additionally, the Institute for Historical Review, an organization known for promoting Holocaust denial, has featured Dalton’s articles and books. His publications are also available on platforms like The Barnes Review and The Occidental Observer, which is known for its antisemitic content.

University of Helsinki researcher suspected of links to prominent antisemitic figure

Subtitle: The University of Helsinki is investigating allegations that a visiting scholar has written antisemitic articles under a pseudonym.

Author: Eero Mäntymaa

Date: 22nd of March, 2025

Source: Yle News. <https://yle.fi/a/74-20151230>

The University of Helsinki is investigating a controversial case involving visiting researcher David Skrbina, who is suspected of ties to well-known antisemitic influencers.

The investigation follows an incident in December when Skrbina appeared on Kevin Barrett‘s Truth Jihad programme. Barrett is a prominent conspiracy theorist accused of harbouring antisemitic views, including Holocaust denial.

The incident took a peculiar turn when Skrbina joined the video discussion under two different profiles: his own name and the alias Thomas Dalton. Dalton is a notorious antisemitic author known for Holocaust denial and other controversial writings, though his true identity remains unknown, with many believing it to be a pseudonym.

The situation came to public attention when the [Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC)](https://www.splcenter.org/resources/hate-watch/academic-david-skrbina-revealed-antisemitic-author/), an anti-racism organisation, published an article linking Skrbina to Dalton. The Finnish newspaper [Demokraatti](https://demokraatti.fi/helsingin-yliopiston-tutkija-mukana-antisemitismiskandaalissa-epaillaan-netin-vihankylvajahahmoksi) has also reported on the matter.

Skrbina, who has worked as an adjunct lecturer at Helsinki University between 2020 and 2023, holds a visiting researcher contract with the university until the end of 2025. According to the university, there are no planned research or teaching activities with him for this year.

The university became aware of the concerns following the publication of the online articles. Mari Sandell, vice dean of the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, told Yle that the situation is under investigation, adding that faculty members involved with Skrbina were surprised and confused by the developments.

Skrbina has denied being Thomas Dalton when contacted by Yle. However, connections between the two men have raised suspicions.

Links between Skrbina and Dalton

The SPLC has previously suggested that Skrbina may be the person behind the alias Thomas Dalton. In a review of Dalton’s book The Jewish Hand in the World Wars, which promotes conspiracy theories about Jewish involvement in World War II, Skrbina praised the work, calling it thought-provoking and filled with lessons for modern times.

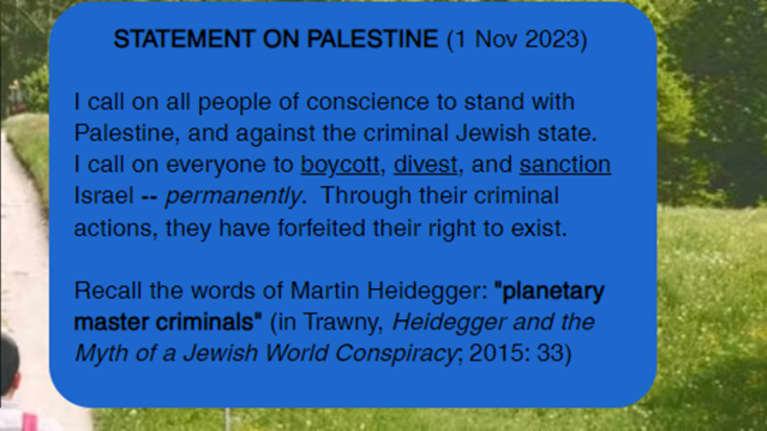

Skrbina has also made harsh statements regarding Israel under his own name. On his website, he calls for support for Palestine against what he describes as a “criminal Jewish state”.

Further evidence linking Skrbina to Dalton includes antisemitic files found on Dalton’s website, which, according to metadata, were created by someone named David Skrbina. The websites of both Skrbina and Dalton share the same IP address and appear to have been built with identical tools. Additionally, the metadata descriptions on both websites show striking similarities.

However, none of this evidence conclusively proves that Skrbina is Dalton. The same IP address can be used by numerous websites, and metadata can be manipulated.

Skrbina firmly denies any connection to Dalton, stating in an email to Yle that he is not Dalton.

Skrbina’s Defence

In response to Yle’s inquiries, Skrbina described his participation in Barrett’s programme as a “joke”.

“The event on Barrett’s show was a joke, which both parties laughed about. Then a criminal organisation used it as the basis for defamation against me,” he explained, referring to the SPLC’s article.

Skrbina further speculated that he might have been the victim of video manipulation.

“I joined the conversation as myself. There are all sorts of video manipulation techniques, but I don’t know how they are done,” he said.

Regarding the IP addresses and text file details, Skrbina argued that these too could be manipulated, and thus, could not be considered definitive proof.

When asked directly if he is Thomas Dalton, Skrbina gave a blunt denial: “The answer is simply no.”

The controversy has prompted some of the publishers that have released Skrbina’s works to react. Among them, Suomalainen Kirjakauppa, one of Finland’s largest bookstores, removed Skrbina’s book The Jesus Hoax, which questions the historical accuracy of the story of Jesus in the Bible, from its shelves after Yle’s inquiry.

University of Helsinki terminates contract with alleged antisemitic researcher

Subtitle: American researcher David Skrbina faces allegations that he has led a double life under an antisemitic pseudonym.

Source: Yle News. <https://yle.fi/a/74-20153520>

Date: 2nd of April 2025

The University of Helsinki has terminated its contract with American researcher David Skrbina amid allegations that he led a double life under an antisemitic pseudonym.

Skrbina, who had a visiting researcher contract with the university until the end of 2025, was dismissed last week, the university confirmed to Yle.

The decision follows an Yle report in late March suggesting Skrbina may have secretly operated under the name Thomas Dalton, an antisemitic writer known for publishing Holocaust denial material. Dalton is a pseudonym, and the true identity behind the name has never been confirmed.

Skrbina has denied being Thomas Dalton.

Suspicions arose after Skrbina appeared in a public video discussion using two separate profiles, one under his own name and another as Thomas Dalton. Several other pieces of evidence have also suggested the two individuals may be the same person.

The University of Helsinki stated that Skrbina was given an opportunity to respond before the decision was made, though it declined to disclose details of the discussion.

“From the university’s perspective, we have sufficiently investigated the matter,” said Mari Sandell, Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, in an email to Yle.

Skrbina’s academic work has focused on philosophical questions regarding technology. The university confirmed that his work there was related to this field.

His most recent visit to the university was in May 2024, when he taught as part of the course “Sufficiency in Organisation and Management Studies”. He had also worked as a part-time lecturer between 2020 and 2023.

The university noted that Skrbina was not invited to teach but had offered his services independently.

Additionally, Skrbina had been working on a book with Toni Ruuska, a docent of sustainable economy at the University of Helsinki. According to Yle, the project has been put on hold due to the allegations surrounding Skrbina.

Skrbina’s Anti-Semitism

Quote #1

Source: Ted Kaczynski & Technological Slavery

Adam: OK, this is what I wanted to get into. The little bit of a topic that I wanted to cover. This is a book that I read the secret doctrine of the giona Villena. He’s one of the most famous Kabbalah rabbis in Judaism from the 1700s, and it says here how couture this is their messianic. Agenda the messianic role of science and technology. This requires everyone, especially rabbis and tourist scholars, to familiarize themselves with the new sciences in order to understand the Kabbalah and the secrets of the Talmudic agada. And then it says torus blueprint for the redemption process. They cite the. Zohar, in the 600th year of the six Millennium, which is 1840 CE, that’s about the time of the Industrial Revolution, the gates of wisdom above Kabbalah, together with the wellsprings of wisdom below, science will be opened up and the world will prepare to usher in the 7th Millennium, which is coming in like 200 years according to the. This is symbolized by a man who begins preparation for ushering in the Sabbath on the afternoon of the 6th day, and they also believe before the Messianic Age. This is the birth pangs of the Moshiach, so we’re going to see more painful contractions, chaos, intensifying wars, famines. Dangerous technology plagues all types of that, that kind of. Stuff and then a couple more excerpts. The doctrine that science and technology play a prophetic and mystical role alongside the ancient mystical teachings of Judaism, and that this synthesis depends upon the Jewish nation being recentered in a rebuilt Jerusalem. Again, he wrote this in 1700s. They accomplished that right, and now Israel is a rising. Tech power in the world this is their Kabbalah agenda. Who’s going to call me a conspiracy theorist? I’m reading right from the top rabbi, it says. Sanctification of God’s name in the eyes of the nations of the Goyum via the unification of scientific wisdom, together with the esoteric wisdom of Israel I played, I played a clip before that all of these, like astrophysicists and scientist, are like, oh, the Kabbalah predicted. String theory and black holes and The Big Bang they’re trying to credit cabal. They’re like, it’s amazing that it knew all of these things highly. And sanctification of God’s name is also through military victories of Israel during the final battles of Gog and Magog, which they believe is end times, wars between Islam and Christianity, and even Russia and the West. They believe one more the teachings of. OK, the teachings of the Kabbalah themselves are the very source of Israel’s ascendancy and the means through which Israel can achieve the most elevated status. This is the intention of the verse to grant you ascendancy beyond all the nations. The gentiles. This is the best part. OK, the Gentiles would be able to understand the wisdom of our Torah from its simple literal meaning alone, but not the secret, esoteric meanings. They already do this themselves by simply studying the written Bible. And then it says if on the other hand, the verse is referring to the wisdom of the Torah that is hidden in the depths of its cabalistic mysteries, behold, they will never fully know or comprehend this, their esoteric mystical secrets. And then it says she is your. Wisdom. OK, hold. On the question is therefore how and under what circumstances will the Gentiles recognize this wisdom of Israel as stated in the verse? She is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the nations. Now the best part right here. First, the Gentiles will recognize Israel’s superior wisdom in the natural sciences. Then they will realize that this wisdom is derived from the esoteric secrets of the wisdom of the Torah. Only then will this verse be fulfilled. She is your wisdom, your understanding in the eyes of. The nations and this will grant you ascendancy above all the nations he has made for praise, fame and glory. And again the verse, the Zohar, the 600th year Kabbalah and science will usher in and prepare the world for the 7th Millennium. What are your thoughts on that?

David: Well, that’s really interesting. I didn’t know anything about the book until you just showed it. So it it’s a yeah really that’s kind of a fascinating statement from the 1700s. I guess is that what you said? So that’s yeah, it’s kind of a remarkable statement. Considering the relatively primitive state of science at that time, it was early in the process that would have been the early phases of the industrial revolution. I don’t know where. That rabbi lived when he wrote. That, but you know, obviously. He could see these things coming and he could see that that was kind of a source of wealth and power. So he wanted to get on the right side of that one for sure. And that was probably a good call. At his part. I guess, but it also makes me think of the present day, right. So I’m thinking about. Even sort of the Jewish role in in the US, in the high tech industry. So I don’t know, Adam, if you’ve considered that or looked at looked at that, but it’s really kind of impressive, right, who’s in, who’s on top of these technological institutions. I made a little just a little short. List the ones. That came to mind. You got Mark Zuckerberg. At Facebook you got Larry Page and Sergey. Brin at Google. You’ve got Larry. Ellison and Safra Katz at Oracle. You got Michael Dell at Dell computer. You got Susan Roode Sickie at YouTube and you got Adam Mosseri at Instagram.

Adam: Sam Altman is Open AI also.

David: And now you… exactly now you’ve got Sam Altman, who shows up with. This open AI, he’s. Big in this a I think it’s coming along. So it’s really kind of impressive, right? What these guys are doing, they’re really in these leading positions on several major aspects of the technological system. So maybe they’re taking your Kabbalah claims there to heart and they’re really viewing this as some kind of messianic mission on their part to run these things for a minute…

Adam: To heal the world, that’s their goal, right? They wanna supposedly heal the world is what they claim. Also, a lot of the top, the top vaccine makers as well. And it’s not my opinion.

David: Exactly because for the CDC you could go through right, the, the vaccine makers.

Adam: You can go to Jerusalem Post.

David: Yeah, exactly. We could add those guys to the list as well.

Quote #2

Source: The Jesus Hoax — Chapter 5.

Recall my explanation above, regarding how Paul and the Gospel writers had two sets of enemies: the Romans and their fellow elite Jews. In fact, they had a third enemy: the truth. Paul and crew knew they were lying to the masses, but they didn’t care. The Gentiles were always treated by the Jews with contempt, as I showed in chapter four. They could be manipulated, harassed, assaulted, beaten, even killed, if it served Jewish ends. This was not a problem for them. But what they did have to worry about were any dedicated and persistent truth-seekers in the world, who might take the trouble to expose their hoax. The cabal therefore had to oppose any intellectual methodology that might lead to the truth: empiricism, rationality, logic, common sense, ‘science.’ All these things would henceforth become enemies of the church, allied with the Devil.

As the initiator of the hoax, Paul earns the maximum amount of credit or, if you will, blame. His ‘moment at Damascus,’ if that’s what it was, kicked off the whole series of events. He constructed a simple and elemental lie, based on common ideas in mythology and a kernel of actual truth, in order to manipulate the Gentile masses for the benefit of the Jews. It was, quite frankly, a brilliant plan. But to successfully pull it off, Paul must have been a brilliant liar. He had to write down pure fiction as absolute truth. He had to lie to people’s faces and pretend to believe it. He had to entice and frighten innocent and simple-minded peasants into believing his outrageous concoction. And he did it. Paul—expert liar, artful liar, master liar.

Not that this is new news. In chapter four I cited numerous ancient sources who criticized Jewish misanthropy, and certainly a willingness to lie is compatible with that complaint. Ptolemy, for example, called the Jews “unscrupulous,” “treacherous,” “bold,” and “scheming.” Unfortunately the label of ‘liar’ has dogged them for centuries. In the early 1500s Martin Luther—founder of the Lutheran church—wrote a rather infamous book titled On the Jews and their Lies. There he declared that “they have not acquired a perfect mastery of the art of lying; they lie so clumsily and ineptly that anyone who is just a little observant can easily detect it”[1]—a statement that could well be a motto for the present work. I also note the striking irony of a man like Luther who was so opposed to Jewish lies, even as he himself fell for the greatest Jewish lie of all.

In 1798, the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant called the Jews “a nation of deceivers,” and in a later lecture he added that “the Jews…are permitted by the Talmud to practice deceit”.[2] In his final book, Arthur Schopenhauer made some extended observations on Judeo-Christianity. He wrote, “We see from [Tacitus and Justinus] how much the Jews were at all times and by all nations loathed and despised.” This was due in large part, he says, to the fact that the Jewish people were considered grosse Meister im Lügen—“great master of lies”.[3] Employing his usual blunt but elegant terminology, Nietzsche said this:

In Christianity all of Judaism, a several-century-old Jewish preparatory training and technique of the most serious kind, attains its ultimate mastery as the art of lying in a holy manner. The Christian, this ultima ratio of the lie, is the Jew once more—even three times a Jew.[4]

Similar comments came from express anti-Semites. Hitler called the Jews “artful liars” and a “race of dialectical liars,” adding that “existence compels the Jew to lie, and to lie systematically”.[5] And Joseph Goebbels, in his personal diary, wrote: “The Jew was also the first to introduce the lie into politics as a weapon. … He can therefore be regarded not only as the carrier but even the inventor of the lie among human beings”.[6]

Finally, a remark by Voltaire seems relevant here. The Jews, he said, “are, all of them, born with a raging fanaticism in their hearts… I would not be in the least bit surprised if these people would not some day become deadly to the human race”.[7] If a Jewish lie were to spread throughout the Earth, eventually drawing in more than 2 billion people, becoming the enemy of truth and reason, and causing the deaths of millions of human beings via inquisitions, witch burnings, crusades, and other religious atrocities—well, that could be considered a mortal threat, I think.

This, then, is my “Antagonism thesis”: Paul and his cabal[8] deliberately lied to the masses, with no concern for their true well-being, simply to undermine Roman rule. This little group tempted innocent people with a promise of heaven, and frightened them with the threat of hell. This psychological ploy was part of a long-term plan to weaken and, in a sense, morally corrupt the masses by drawing them away from the potent and successful Greco-Roman worldview and more toward an oriental, Judaic view.

As we know, it took some time but the new Christian religion did spread, eventually permeating the Roman world. In the year 315, the emperor himself, Constantine, converted to Christianity. In 380, Emperor Theodosius declared it the official state religion. And just 15 years later, in 395, the empire fractured and the classic (western) half utterly collapsed. In the ensuing vacuum, Christianity rose to power—and in Rome itself, of all places. The victory was complete, some 350 years after Paul’s grand vision came to him in a flash, “brighter than the sun.”

Quote #3

Source: The Jesus Hoax — Chapter 6.

And then perhaps another question comes to mind: Why haven’t we heard anything about all this before? Surely, if the case were so compelling, one might say, we would have seen it in movies, or heard news stories about it, or had it taught in schools. And yet nowhere—not even in our universities—do we hear this matter discussed. Why is that?

This is an enlightening question. We need to ask this: Who would have an incentive to examine the truth on this whole subject? Christians, obviously not. No one in the Christian hierarchy wants people to explore the truth, even though it’s highly likely that many of them do know it. Once you have an organization in place, salaries to pay, mortgages, monthly bills, and taxes, you need the whole business to keep functioning. Christians have every reason to sustain the hoax, not get to the bottom of it.

Jews have no interest in the truth here, either. As the ‘bad guys’ in the hoax story, Paul and friends threaten to cast a negative light on all Jews. This is particularly true when we look at the millennia-long history of critical comments on the Jews, as discussed in chapter 4. Any unearthing of these facts would require a lot of subtle explaining, to say the least. Rather than admit to a Jewish lie, present-day Jews would rather not bring up the subject at all. Particularly so, when millions of Christian Zionists are ideologically on their side. It’s simply a no-win situation for Jews, and so they let that dog lie (pun intended).

One might think that Muslims would be eager to criticize Jews and Christianity, and to expose any hoax. Yes and no. Islam, of course, is part of the Abrahamic lineage and thus is ultimately wedded to Judeo-Christianity, whether it likes it or not. Muslim monotheism derives ultimately from Judaic monotheism, just as it does for Christianity. All the Abrahamic religions worship the Jewish God; Muslims simply changed his name.

Islam furthermore accepts Jesus as a “prophet” and even grants him a kind of divine status—though they disavow his resurrection. The Quran has a number of interesting passages on him. Jesus (“Isa”) performs miracles, but only with Allah’s “permission” (III.49, V.110). Jews neither killed nor crucified him (IV.157), and so he did not die a martyr’s death. In a particularly impressive miracle, the Quran states that the infant Jesus spoke immediately upon birth: “He said: ‘Surely I am a servant of Allah; He has given me the Book and made me a prophet, and He has made me blessed…’” (XIX.30–31). Muslims therefore cannot accept either a mythicist Jesus nor even a merely historical Jesus; they need a semi-divine miracle man as well.

Governments are nominally neutral on religion, especially in the United States with its famous “separation of church and state.” They should, therefore, have an interest only in historical truth. When they draft school curricula for millions of public school children, it’s clear that they should at least present a mythicist alternative to traditional orthodoxy, as one line of thinking. But such information has yet to appear in any public text, to my knowledge.

But there is a deeper reason, I think, for why they avoid criticizing Christianity. Governments everywhere want compliant populations. They want citizens who will respect authority without question, follow the laws, accept its power, and not be too inquisitive. They like people who simply have faith in government, and who more or less blindly trust them. And in Christianity, rulers have found an ideology that can serve their interests. They can play up the ‘peaceable Jesus’ storyline—love thy neighbor, turn the other cheek, Jesus as “our paschal lamb” (1 Cor 5:7) or our “shepherd” (Jn 10:11), followers as “sheep,” (Mk 6:34, Jn 21:15)—while directing any militant undertones toward the “devil” of their choosing. Governments have no interest in turning over that applecart.

Colleges and universities are somewhat better, often having panels or speakers who challenge the Christian view. But the Antagonism Thesis is particularly difficult to discuss since it casts blame on Jews, and any negative talk about them risks ostracism or worse, even in our “liberal” and “free speech” universities.

What about our irreverent media and Hollywood filmmakers—those who are so willing to commit sacrilege against any social norm or moral standard? I suspect this has something to do with the extensive role played by Jewish Americans. It’s uncontroversial that Hollywood has been dominated by Jews for decades; a relatively recent article in the LA Times cites Jewish heads of nearly every major Hollywood studio.1 And it’s not just the movie business. All the major media conglomerates have a heavy Jewish presence in top management. If they should decide that Jewish malevolence at the heart of the Christian story “looks bad,” then they obviously won’t bring it up at all—not in the news, not on TV, not in books.2

Footnotes

1. “How Jewish is Hollywood?”, by Joel Stein (Dec 19, 2008).

2. For an interesting analysis of the role of Jews in the media, see Dalton (2015: 264–268).

Bibliography

Dalton, T. 2015. Debating the Holocaust (2nd ed.). Castle Hill.

— Primary Source Material —

David Skrbina on Ted Kaczynski & Luigi Mangione

Source: <old.bitchute.com/video/hLmXdibnPEEI>

Date: December 20th, 2024.

Authors: Kevin Barrett & David Skrbina

Kevin: Kevin Barrett doing this podcast in audio form up until a few years ago and now putting out video here on Revolution dot radio. The greatest of free speech sponsor radio network sponsor it yourself. Go to revolution dot radio and check it out. All right, I’m Kevin Barrett of Kevin barrett.substacks.com, where you cannot pay me to subscribe to my sub stack because I have been debated by strip. But if you go there, you’ll find your way to the workarounds, including my PayPal donations page. If you like this kind of free speech radio, be sure to well support it in whatever way you feel like. So hey, let’s get going tonight. We have a theme show that is after Luigi Mangione, the CEO Slayer has become a folk hero, necessitating the feds. Going after him with a death penalty threat in federal court, as well as a murder prosecution in state court. And then we had this news that a an anti genocide fighter has just been arrested for targeting the genocidal consulate in New York. So this is an interesting time to talk about that virtually non-existent. So it’s so minuscule, the fraction of human violence that. Is perpetrated by somebody other than governments, that is non state sponsored violence. There’s hardly any of it. I mean there’s a lot, but compared to what the state sponsored violence gives us, it’s virtually nothing. It hardly even exists. But I think it’s still worth talking about. And so we’re gonna talk about it with one certified expert and that. Is David Scherbina David Scherbina is a philosophy professor. He was a correspondent of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, and he published and edited one of his. Books. And David Scherbina is an expert on the metaphysics of technology. And the various critiques of technology that have been associated with the supposed with the Unabomber issue. And so on. OK, I just got a message that David is unavailable. So we’re gonna have to do a little work around here to try and bring him up. How are we gonna bring David up? We’re gonna pull this up, share a link for him, and we’re gonna send that to him, and hopefully he’ll be able to join us. And it’s kind of interesting how this stuff works sometimes better than other times, but let’s see. Where’s David? There he is. OK. Hello, David. We’re gonna send you a link here and use this to join the conversation and use. This. To join, OK, see if that’ll get David Scherbina up onto our show. And if not, then we’ll find some other work around. That’s the way it works. When you’re self producing here at Revolution dot radio. So. The let me talk a little bit about the second hour we’re gonna bring on Michael Brenner. He’s an international relations professor emeritus at this. Point. And we’re gonna talk about his essay. His very brief essay on anger in defense of anger that he sent out recently. A lot of people are tearing their hair out about the anger that’s floating around in American Society leading to these terrible events like Luigi Mangione shooting Healthcare. Deck and then the school shooting in Madison, WI and all of this. This mindless, senseless violence. As opposed to the mindful and very, very sensible violence of the US government supporting the genocide of Gaza, slaughtering 30 million people around the world as a response to the inside job of 9/11, which was perpetrated by governments. So yeah, mindless violence, right? Pushing back against the perpetrators of mindful violence through mindless violence. Very few people have done that, and it seems like it’s worth analyzing. All right, so Michael Brenner comes on there in the first half of the second hour and then in the second-half of the second hour, Rolf Lindgren reports live from Madison, WI, and Rolf will talk about this school shooting. He. Apparently, is he probably knows some people that send their kids to the Christian School where the shooting happened. Because Rolf is a Republican Party events coordinator, and so he sets up these kinds of film screenings and discussions and speeches by politicians, things like that, and he gives away free books at those events. And Ralph therefore has a pretty good kind of connection with that world of conservatives in Madison, WI, who are, by the way, a minority there. A Madison, WI is about as woke. I guess it’s gotten more kind of blandly woke over the years that I was there. I was popping in and out of Madison from my high school days, which were circa 1972 to 76. I used to drive over from the Milwaukee, WI outskirts of Pewaukee where I lived. To Madison, when I was starting at at 15, when I first got my driver’s license and I could drive legally in the car if there was somebody else in the car, I would drive an hour over to Madison and and try to talk with the college girls and things like that. And then I went to college there undergraduate years, and I’ve kind of been popping through Madison, WI. Ever since, and it’s definitely gotten much more vapid, rely woke over the years, it was always very left wing, but left wing wasn’t as stupid back then as these days. Maybe it’s just me, I don’t know, but we all changed our views over years. I think it’s me that’s changed. I think it’s the. The so-called leftists of Madison, WI, and anyway, so the Conservatives are now a small minority there and Rolf Lindgren is one of those movers and shakers in that world. That minoritarian world of conservatives of Madison. Johnson. OK, we’re having no luck here getting David on us. Let me try adding David Scherbina again using the standard method of trying to add somebody to the call. OK, there’s David. It says not on this call. Why isn’t he on this call? Hey, David, what’s going on here? He’s he’s listed as. As being having the link shared and stuff, but it tells us he’s not available to be on the call. Now, theoretically, if he finds the invitation, he will show up. He’ll be able to get on the call despite this weird method that seems to be locking him out. All right, he said. There would be no need for get the right time zone here with him, because that would be crazy if we tried to get everybody at the same time in the second hour. So yeah, I don’t see any emails from him, but. Yeah. OK, well. In that case, we don’t have David on. Let’s see, who could we randomly pull up here and see if somebody might be randomly available? Let’s see, looks like Cynthia McKinney isn’t on Rolf Lindgren’s coming on later in the show, but I don’t think we wanna bring him up yet. And spoil the suspense. Although that would be that would be interesting. Who else we is if we have anybody listening, who is one of our regular Skype listeners who would like to join the show? Just send the Skype message here and I will pick up on you. All right, so. Where do we even start with this topic of non state sponsored Viola? Yes, well, I guess I could mention that if all of the kind of life changing events that I underwent as a youngster, which included watching Lee Harvey Oswald’s attorney, give a talk. In Milwaukee, WI in 1974 about and show the Zapruder film and that undermined my faith in the American government. But another work that I encountered not long after that that undermined my safety government even more, at least at the kind of a theoretical level, was by a guy named Wolf Wolf, and it was entitled in defense of anarchism. And it’s a philosophical work political philosophy book that. Basically, argues that the there’s no rational basis for the notion that governments are magically legitimate, and that is that why do we consider that a government has more right to set the rules that we live by? Than anybody else than any other, say bureaucracy or club, right? I mean, you could just start a voluntary club with your friends and call yourself the government of planet Earth. And tell everybody what to do. And why does your club have any less right to be obeyed than, say, the United States, the United Nations, or what have you? And the answer will points out quite accurately, is there is no reason why there’s no real reason why anybody should take. Seriously, the claims of governments that they have some kind of special status that gives their rules any kind of special reason why they need to be obeyed any more than random rules set up by any other person or group of people. So yeah, so it’s an interesting argument and a lot of the counter arguments are really just based on pragmatism, which ends up supporting Wolf’s point. Which is. That ultimately, if you just go along with the strongest force around you, whatever that force is like, if some Mafiosi thug is holding a gun to your head. And you do what he tells you. That’s pragmatically probably a smart move if you don’t want him to shoot you. And likewise. If the government is telling you that you would need to, let’s say, pay your taxes. And you choose to do that. That might also be a smart move, so you don’t get kidnapped. But there’s there’s no reason why it’s necessarily the right thing to do to obey the government, but not necessarily the mafiosi. For instance, what if you could knock the gun out of the mafiosi’s hand? And turn it on him. And escape. Would you do that? Is that the right thing to do? Yeah, if you can get away with it. Absolutely. Of course it is. So what if you could knock the gun out of the? Government’s hand. And not pay your taxes. Would that be the right thing to do? Well, there’s all kinds of special pleading that the apologists for this myth of government legitimacy that Wolfe ably deconstructs in his book in defense of agrarianism would come up with. But it’s all ********. That is ultimately, there’s no for every reason and no rational reason indeed. Why you should accept that the government has the right to point the gun at your head and take your money. But the mafia’s achieved and doesn’t. So ultimately it becomes pure pragmatics. It becomes, you know, whatever works in the situation. Now The thing is that that’s the governments. Flourish. By pointing their guns at people’s heads and then but somehow convincing people that it’s OK that it’s legitimate for the government, unlike a mafiosi to point the gun at your head if it’s government pointing. Your head. It’s not the gun. That’s the reason that you obey them. It’s because it’s legitimate and there’s consent of the governed. And there’s the social contract and all of this ********. That stuff is ********. Total, absolute, utter, obvious ********. And I could figure that out as a 16 year old reading Wolf’s book in defense of anarchism. In the early 1970s. So that leads us to questions like given that the vast majority of virtually all violence and aggression and grotesque, extreme oppression and injustice that’s being perpetrated on this planet today is being perpetrated by governments. Maybe. Maybe people should start knocking guns out of their hands a lot more often. And maybe we should stop going along with this ridiculous habit of accepting violence that’s committed by governments. But deploring and hating and reviling violence that’s perpetrated against governments or against the will of governments like Luigi, for example, take Luigi, Luigi Mangione. So he killed the health insurance executive. OK, well, the United States government killed 30 million innocent people. As a response to the false Flag Act of September 11, 2130 million people. And now the people who are trying to convince you that the US government is some kind of special entity, that therefore it’s really not such a big deal that it kills people, but it’s so terrible that Louise, she she only killed somebody. Those people deserve your absolute utter contempt scorn. Derision and whatever else you can muster to throw at them. So. Oh, that’s that’s that’s my opening rant here. But unfortunately, we we don’t seem to have David Scherbina to see whether he agrees or disagrees with me on this one. But David, probably more or less agrees because he he wanted to come on here to talk about. The issues raised by Luigi Mangione’s rising to folk hero status.

And of course, among those issues are the issues of the way that extreme injustice and radically bad choices and policies at the collective level can be responded to. Maybe should be responded to. And you know, there’s one discourse that’s that’s consistently pacifist. That deplores all violence. Equally, whether it’s committed by governments or by non governments. Yeah. And so that to be consistent, that position requires you to oppose uniformed thugs kidnapping somebody like Luigi just as much as you would oppose uniformed thugs kidnapping at your. Yeah, just anybody else. Rather as much as you would oppose non uniform thugs, mafiosi or criminals? Kidnapping. Somebody, and so likewise it requires you to deplore the people killed in Syria, U.S. soldiers killing people in Syria. Today they’re occupying Syria, stealing their agricultural lands, best farming lands, stealing. Their energy producing land and if somebody gets killed over there, that’s just as much of an injustice. And just as much, if not more, something you should oppose as, as some CEO getting shot by some angry anti health insurance. Right. So I think David Scherbina is definitely the guy to talk on this subject with because again, he’s the editor of the late Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. Who famously was quite eloquent in his manifesto, arguing that technological society is heading down, down, down, leading us to hell, and it would be better to blow up technological society through terrorism. Quote UN quote if necessary or by whatever means. Work and take the consequences, which of course would be immense suffering as the technological life support systems we all enjoy today disappear. He thinks that would be better than allowing technology to continue to destroy humanity on the planet because it’s gonna get harder and harder and harder to get out from under technology as time goes by. And so those arguments that Kaczynski made back in the what 70s, I think? We have seemingly been borne out to a certain extent by events, as many of the kind of most fearsome prognostications of people worried about technology back in the day have proven to have been correct or even understated. And now we have AI writing how to kill which 200 innocent people should be killed in Gaza so that they’ll have at least a 47% probability of killing one Hamas Courier. This sort of thing, these kinds of horrors, drones running around surveilling us, the surveillance state being. It’s so powerful that it can easily catch people like Luigi Mangione while he’s at McDonald’s, and they have to make up a ridiculous story that somebody recognizes eyebrows. So Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto, which of course has been published and become something of a classic. Rick was then followed up by, I think a book called Technological Slavery. If I recall, edited by David Scherbina. And then David has produced some of his own books on these topics, including the metaphysics of technology. Which looks at the philosophical critiques of technology that Ted Kaczynski, let’s say, popularized through his terrorism campaign. Ohh and you know, I wonder if technology is being used to to block my conversation here with with David. Let’s let’s try him one more time. Because he he actually knows more about this stuff than I do. So there’s David. What happens if we try calling him again? He has a couple of different Skype accounts, but I know this is the one that he sent me. So it should be the right one. And unfortunately I thought maybe we had a time zone problem that does seem to happen a little more than it used to, since here I am in beautiful Morocco. Which has it doesn’t change for Daylight Time. It hangs out on central European time. And it changes, I think briefly, maybe during Ramadan or something and and then everybody else is always changing. And so Morocco gets confused. But I don’t think that’s the case. I think we have the right to. Time zone for David. And he’s he’s not showing up. Yeah, well, it’s a. It’s a dangerous topic to talk about. See if it’s right. Gordon Duff. He’s an expert on. Violence. Yeah, it’s a good thing Gordon Duff doesn’t have the morals of Ted Kaczynski or there’d be mayhem out there. Gordon is the former editor of Veterans today, which is now VTC foreignpolicy.com, where I hang out a little bit. Although. I’ve had some some technological glitches preventing me from logging in there, which is why I don’t post there much anymore. But anyway, Gordon has quite a collection of highly specialized firearms, has to be seen to be believed. Gordon is a master gunsmith. And allegedly has moved in the world of the people who use these kinds of weapons for, well, ostensibly government approved purposes. Three letter agency type stuff. And you know, his take on all this is is kind of, to my mind a little overly pragmatic that rather than being interested in the the principle of the thing and then the the actual philosophical argument about some of these things. Yeah. Gordon has kind of given up on that. Was just interested in getting stuff done and at some point he said, well, I don’t mind killing people, but I guess I just got tired of killing the wrong people. This was an explanation of leaving the three letter agency and becoming a bit of a pushback. The artist anyway. Gordon doesn’t seem to be available in responding to his messages at the moment. What time is it over there where he is? It’s gotta be like late morning. So that’s not the reason. He’s probably busy feeding his cats or taking apart a gun and putting it back together or something like that. All right. So we’ll, we’ll skip that. He’s like I said, he would be a violence expert to discuss this topic with, although he probably do that whole brilliant, add addled rant kind of thing that he so often does, and we probably wouldn’t be any the wiser when he was. None. Let’s see. Who do I see? I see. I see a few people reading on Skype. That probably wouldn’t be the right people to bring up for this particular topic in some of the cases, it would be maybe not the right people for really any topic. Let me try. We have a loyal listener here, Patrick. He was green. Let’s try Patrick. He says what is today is this Sunday OK? OK. Well, we we’re we’re going to try to see if we can reach Patrick here. Let’s see, he’s. He turned green. There he is. OK, let’s let’s try him and Patrick Chanel. He was on the show. He was actually a guest here. A bit. A little while back and did a very good job. Hey Patrick is. That you.

Patrick: Kevin.

Kevin: Hey, how you doing? Pretty good. I’m doing great. I’m hanging out broadcasting live on the radio. You are live on the radio, so don’t say anything illegal.

Patrick: I’m doing well. How about yourself? Alright, I won’t. Sounds good. Yeah, I was listening to you. I see your your guest didn’t arrive. That’s that’s no good too. Have been. I’ve been.

Kevin: Yeah, yeah.

Patrick: Following that a little bit. Through what I’ve been, you know, listening to, on and off, I I heard some of it on the no agenda show with Adam Curry and John C Devorak, which goes out every Thursday and Sunday. But they seem to think that. He’s, you know, they’re kind of ambivalent as to whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, since you kind of, you know, you can’t condone outright execution. Without a judge, jury or, you know, or. Trial. So I would definitely be against what happened there, but as far as people’s frustration, you can understand it after the whole COVID affair that took place.

Kevin: Yeah, yeah, I agree. I mean, the point I’ve been trying to make here, of course is is. That it’s interesting how you get this dispute between the the the 40% of the young people who think that Luigi Mangione is a hero, and then the maybe 78% of the population, according to the polls, that doesn’t think that. But that same 70% of the population, which likely will allow them to see the. Jury that will that will condemn Luigi Mangione is doesn’t really seem to be all that upset about their tax dollars being used to exterminate the women and children of Gaza. And that raises this question where Ukraine?

Patrick: Or you. Ukraine. Yeah, definitely. I just got a message today about about an hour ago. Not even an hour ago. A friend of mine who I visited when I was in Russia sent me pictures of a missile strike the US had gone out out in Russia, in the town of Real. And it was just, you know, devastation. It’s like, what are they doing? What are they? What are they trying to? Accomplish. What do you what? What’s your take on the whole Russian, Ukrainian thing? And why? Why? Why are they doing it? What? What benefit does it do to have? Russia. Take it. Well, I guess it, you know the you don’t have someone challenging the authority of NATO in in these these sorts of organizations that we have. That supposedly lowered over us these rules and these rulers, these cruel rulers. So what? What? What is your take on the whole Ukraine situation as it stands?

Kevin: Well, yeah, I guess I’m somewhat persuaded by the the realist school of foreign policy analysis and that they argue that it’s kind of predictable that you have these states that are seeking security. They’re driven by their populations to try to. Get powerful so they can prevent disasters like losing wars when your country loses a war, it can be a really horrible thing, and even if you’re not losing a war, you still lose. Out of economic well-being by not being so, so there’s just this sort of the way the game is played is is that these nation state entities are kind of always Gosling against each other and trying to find ways of. Getting an advantage, that’s the other. And you know, so they’re seemingly defensive. In the office. And so that, you know, that’s kind of the basis of where these things have. But then I mean seeming irrationality of some of these policies, including the American this, this starting this war on Russia and pushing so hard on Russia. When you would think that a saner approach would be to sort of manage the US empire standoff against rising China. China, by peacefully sort of playing off different parties against each other and holding back on the heavy duty violence and avoiding it like why do you need that? And so there’s like this excess of violence that seems unnecessary, the craziness of. Pushing NATO right up to Russia’s borders when it wasn’t necessary.

Patrick: Kevin, Kevin, I think we have someone that’s joined the call.

Kevin: NATO could. Been. Yeah, yeah, looks like somebody joined the call. Who’s the? This user.

David joins the call

David: Hi, Kevin, David, it’s Skrbina.

Kevin: David, OK, we got somehow not David on the line.

Patrick: Kevin. Kevin, I’ll, I’ll talk to you later. Thank you.

Kevin: OK. Well, Patrick, thanks. Yeah, great talking with you and we’ll pick that conversation up a little later. All right? So that’s so hey, David, how are you doing? I’m sorry about the problems getting connected. What happened?

David: Yeah. Sorry. Just a little got deflected from my schedule here this morning. Sorry about that. But I think I’m back on.

Kevin: You, you, you, you, Luddites, you Luddites are always doing that kind of stuff. You don’t. You don’t. You don’t. Look, you can’t look at your watch because you.

Unknown Speaker: Exactly.

Kevin: Don’t even believe in having wrist watches.

David: Yeah, not that bad. Not that. Not quite. That bad, yeah.

Kevin: Well, that’s good. OK, well, so, so where do we even start? I ranted a little bit earlier about how when I was a young and impressionable. My mind was blown by waking up to the JFK assassination problem in kind of the early to mid 70s when I was in high school and then around the same time a little after I encountered the book in defense of anarchism by a guy named Wolf, which makes a very, very strong case that we shouldn’t be giving governments any kind of. Special status in terms of being considering that their violence is legitimate and everybody else’s violence is not. So between those two things, I’ve basically lived my whole life without having the slightest respect for any kind of legitimacy that governments claim to have. And that question about when is violence legitimate? Has been raised by Luigi Mancini only becoming a folk hero, and you’re an expert on this having been. Correspondent and the publisher of Ted Kaczynski, the Unibar and also being one of the leading critics of technology. And being someone who would sort of side with that anarchist perspective of wolf and so on, that we shouldn’t necessarily assume that illegal actions are necessarily bad. So go ahead and pick it up. From there.

David: Yeah. Yeah. Thanks. Can you see me? I’m trying to.

Kevin: Make sure. No, no, I. No, I just see this, this little dot, this is Gu which is guest user.

David: Yeah, that’s what I can see too. I don’t know how to make it work. My camera’s on. I don’t know.

Kevin: Yeah, maybe it’s some kind of a permissions issue with your computer. Well, you’re a Luddite. So you have an excuse for that as well. You. Have a lot of excuses.

David: I’m well covered. Yeah, sorry. It says Skype has limited functionality. I’m not sure. Why it’s not letting me? Give you my video image but.

Kevin: It knows you’re it knows you’re a technophobe and it hates you. The AI has figured out who you are. It’s punishing you.

David: I I yes, I guess that’s it.

Kevin: Yeah, yeah, we knew it. Come to that, yeah.

David: In any in. Any case. Yeah, you’re right. So I mean, just just to talk about the Kaczynski case, right? So it’s. There’s some interesting. Parallels right between that and Mangione, right. So we have two individuals. Who took it upon themselves to take to take violent action for A cause, basically. And and, but there are differences as well, right? So I mean, there’s some superficial similarities, but there are also some significant differences. Kozinski. I, as far as I can tell, viewed his his his bombing campaign as sort of unique situation to gain the notoriety necessary. To publish the manifesto. And and that was kind of a very unique situation, you know, and he never advocated other people doing anything like that either in the manifesto, in the end of his post imprisonment writings, none of his letters to me, nothing talked about advocating violent action. Right. I mean it was understood that. That was a. A potential aspect that that might be part of the part of how the movement would operate but but somehow that was never really advocated by him direct.

Kevin: Isn’t that partly, though? Because that was sort of the conditions he was in once he was incarcerated. He wasn’t in a position if he advocates of violence when he’s incarcerated, they’ll shut him up.

Unknown Speaker: Well, it’s not.

David: Well, yes, exactly right that. So that was one of the one of the concerns was he while he was in prison, he could not write about it as he was communicating with myself and others, but of. Course in the manifesto. Which occurred before he was in prison. He basically had the a blank check. He could have written anything he wanted in that and they were going to basically agree to publish it. And even there, he was very circumspect, you know, he said the revolutionary actions might be violent. They might be, might not. They might be relatively rapid. They might take a long time. So. So even there, even when he had the chance, he, he declined to advocate explicitly of violent action.

Kevin: Interesting. Yeah. And so he he used violence as a sort of publicity stunt to get his message out there. And his very substantive manifesto out there. Whereas Luigi Mangione, his manifesto doesn’t seem to be nearly as substantive. Was it?

David: Not from what I can see. I don’t. I don’t. I didn’t not have a chance to see this whole document. Is it a released?

Kevin: No, they yeah, yeah. You. I apparent well what was put out there as supposedly the the whole quote UN quote manifesto was more of a manifesto of like, I think 250 or 300 some words. So it’s not even.

David: Yeah. OK. Exactly so. So there was a, what, a brief review of Kaczynski’s manifesto, right.

Kevin: Yeah, he mentioned it. Yeah.

David: Yeah. So, so so there. Was a few. Yeah, that OK. That was not. That’s right. That’s that’s that’s a micro micro fest though. I mean that was so small, right? It was just a few words of endorsement by him. There was a long quotation of somebody else that he apparently agreed with, and that seemed to be the extent of that of that particular post. So, you know. Unless something else surfaces, that’s that’s a pretty it’s a pretty, pretty small statement, just sort of generic interest and generic support for something like like that sort of action that Kaczynski was talking about.

Kevin: Yeah, it’s so why? Why do you know? Actually what kusinski did? In a sense, you could say it’s it’s warped or immoral or at the very least, you could argue that maybe he harms some of the wrong people, that people didn’t really deserve to be harmed in the way he harmed them, but his. The overall strategy was basically pretty rational in that he said, yeah, I’m going, I can get this message out to a lot more people if I do this. Violent Terror campaign is the publicity stunt. So it kind of makes sense within its own framework. But with Luigi Mangione, I guess maybe it’s just why do you think he did this? Like what good is it to to just kill one health insurance executive? Do you think he’s trying to inspire people to copycat him, or it’s hard to imagine the motivation, really.

David: Well, right again, there’s, that’s again an interesting parallel between Luigi and and Ted. Right? They were. They were both combating a larger system right of of which they are very small part. And so there’s this perennial dilemma of a of a large organizational structure, which is, you know, unjust or illegal or needs to be reformed or changed or overthrown. And how does an individual or a small group of individuals have any effect on this process? And and yeah, you’re right. I mean, an organizational structure that contains hundreds or thousands of people, it doesn’t really do any good. Even if you kill one or two of them, the system will just work around it. It will replace them, and it will. Move on. So so all you can do is gain attention, gain the notoriety, maybe use that to get a message out, maybe to send a message right to others that that extreme action is being taken by by individual people out there. So, you know, in, in Ted’s case, he was willing to take extreme. Action and he was willing to send a detailed message in terms. Of the manifesto. We can only guess in Mangione’s case that you know again, he’s maybe willing trying to send a message like like, these CEO’s cannot act with impunity and that they will somehow pay a price for for extremely unjust action. Right. So I guess we can assume that that’s. That’s really what Luigi had in mind. It’s hard, hard to know unless we hear from him. Exactly.

Kevin: Right. Yeah, I could see it as a kind of a symbolic attack on the the corporatocracy on the the fact that there’s been this change historically from like 1960 to today. The salaries of the CEOs compared to the average worker in the corporation have skyrocketed. To these orders of magnitude greater than they used to be, which also tracks with the overall shift of wealth in a wildly unjust direction, the distribution of wealth has gotten out of. And so certainly this idea that these very powerful people who are taking actions that harm huge numbers of other people, maybe shouldn’t always have total impunity and should have to think about the fact that these people that they’re harmed might someday harm them, that. Kind of makes a certain amount of sense. I wrote about that, sort of. From this I wrote a satirical piece from the viewpoint of my cat saying that you need claws if if the dogs don’t know that you have claws, they could. Just kill you. But if they have to worry that you have claws, they might actually behave a little better. And so maybe according to my cat, it would actually be a good thing if there were a lot more of this sort of thing, because then the people with power would have to realize they would have to consider the possibility that they would need to treat the less powerful people better. In order to survive.

David fucks up and reveals his alt identity — 39 minutes in

Kevin: So, so, here David, we just have, is that Thomas Dalton just showed up here, but I don’t know how? Thomas. Hello. Welcome. How did you show up in our show?

David: I don’t know how that happened.

Kevin: So this is your…

David: Hello. This is David. I’m I’m I’m getting a double. I’m getting an echo here so…

Kevin: What the heck? OK, OK. Yeah. David, that’s David’s picture with Thomas Dalton’s moniker. Thomas Dalton is the famous author of What’s it called Debating the Holocaust. But no, you’re David.

David: Ah.

Kevin: And then the guest user is still there. OK. Anyway, welcome. You’re confusing the heck out of me though.

David: Yeah, I don’t know. It’s weird. I’m getting an echo here. I don’t know why, but.

Kevin: Yeah. Well, there, there are two. Is there any any way you could hang up on the guest user? Here, I’ll get rid of the guest user. I’ll get rid of your echo. Here. Let’s see. Remove from call. OK, great. So now it’s just David AKA Thomas Dalton. Oh man, The ADL is gonna come after you now, they’re gonna think… you’re the Holocaust denier.

David: Oh boy, there you go. Yeah, but I mean, it was a good point. Right. What what you what you were saying there, Kevin, that, yeah, you have to have fangs, right? They have to take you seriously or or else you know, the the whole the whole resistance movement sort of comes to not right. I mean, nothing. Nothing can, can, will, will actually come out of it. So, I mean, you know, to me as sort of my background as philosophy, right, as an ethical philosopher and I it’s kind of interesting to to think of this as like a new ethical imperative, right. If these CEOs have to make decisions knowing that, you know, they’re that these actions could drive someone to homicidal action. Right, maybe. Maybe they need to take that into account as they make their policies that enrich the corporation and enrich themselves and their executives, maybe they need to think a little bit harder about. You know what’s it doing to? To to regular people on the street and what are the implications there, right?

Kevin: Indeed, indeed. And you know, and arguably the the the point I just made, if if pushed too far, it could be used to justify things like a school shooting by somebody who’s been bullied. Because see, the same kind of argument is that if an oppressor or a bullier knows that if they push the bullied person too far, the bullied person will just go crazy on them and be willing to basically throw away their lives in order to exact a price. From the bullier, the bully or the oppressor? If they know that, then they won’t bully or oppress so much. But then, if you take that too far, and then you’ve got, you’ve got a justification for school shootings. We’re gonna talk with Rolf Lindgren directly. Live from Madison, WI about that school shooting in a little bit. And now the opposite argument, of course, is the Hobbesian Neo con argument that you need to have. One great big bully in charge of the entire planet who will just squash anybody who gets out of line, and then we’ll all live happily ever after peaceful and prosperous, prosperous. And all that.

David: Well, right, I mean the state demands a monopoly on power, right? I mean that that’s really one of the things that are going on here. They’re they’re appalled that, you know, someone an individual might might take deadly force into their own hands and then act on that basis. Right. This is the traditional prerogative of all state. Governments, is they they have to have the exclusive monopoly on deadly force. Course. And they use that to impose order and and and, you know, and and keep keep people in line. Right. The problem is when they become corrupt and they and they also have that monopoly then then you’re in a bad shape. Right. Because then they can use that monopoly power to cause great harm to society and to yeah. The planet to to people. Everywhere. Right. So that’s that’s a dilemma, right?

Kevin: Indeed, yeah it is. And I don’t see any super easy solution there, you know, another an interesting comparison between Luigi Benzoni and Ted Kaczynski is that back when what year was Ted Kaczynski captured?

David: Yeah, 96, wait.

Kevin: 96 OK, because at that time he was very sharp, of course. And then the tracking and surveillance technology had not advanced as much as it has today. So the only way they were able to catch him was his brother turning him in based on his writing. Style and today with Luigi Mangione, they claimed that they caught him in a McDonald’s because somebody in the McDonald’s noticed his eyebrows. But the whole collective eyebrows of the Internet went way up in the air when they heard that saying ********. Some kind of surveillance technology caught him and they made-up that ridiculous eyebrow. In any case, Kaczynski was right that surveillance technology was going to massively advance. Very, very. To the point that somebody, even somebody like him, probably couldn’t get away with it for as long as he did because of pretty soon there will be cameras everywhere. And so if Ted tries to take a bus from the Wilds of Montana to Salt Lake City to drop a bomb in the mailbox, something’s gonna catch him. Something along the way, he’s gonna be picked up on a license plate. Surveillance camera or satellite, whatever. So anyway, the point being that and this proves that Ted’s right, because now we’re living in a nightmare world. We’re willing in hyper surveillance, right?

David: Well, yeah, exactly. I mean that’s that’s only one small area that you’ve been proven right, right. I mean the whole Technosphere has expanded massively, you know in the past 20 or 30 years, but surveillance and certainly one of those areas right where everything is monitored or everything is filled, everything is documented and and now we have AI systems that help pour through those. You know these gazillion bytes of data that are all being collected and analyzed so. Yeah, I mean, it’s just just one aspect of of of this techno nightmare sort of scenario that’s kind of being realized all around us. I guess you know some people could say, well, this is great, right? Because we catch criminals that way because we’re filming everybody and everything and we’re checking every car license plate and you know, every every. Every McDonald’s in the world simultaneously, and we’re stopping criminals. But of course it’s a massive invasion of privacy, you know? And and and there’s so many ethical problems that that are posed by the government having access to. Yeah, this massive amount of information about everybody and where everybody goes at any time, what everybody says and what everybody’s thinking and what you know, it might be implied about everybody’s thinking or what they should have said and they didn’t. I mean, so there’s all kinds of avenues of of, of abuse that are opened up to powerful and corrupt governments that have this. Kind of information and I I think we’re seeing that as well.

Kevin: Indeed, yeah, I personally agree with the laws against eavesdropping that used to be out there. You weren’t allowed to tap somebody’s phone. And I think that could even be used for, like, reading people’s mail. And therefore, these three letter agencies and someone that are listening to us and tapping our Internet communications and so on. Are criminals. And so they actually are the ones who ought to be punished. They ought to be. What do you do to people who violate laws while you kidnap them? You lock them up and so on. So actually, the people who are listening to us on behalf of the government without permission, therefore eavesdropping us violating our privacy, violation of privacy arguably is criminal in the sense that. It’s grossly immoral to the point that it needs to be punished, but when you have the people who call themselves the government and dominating the apparatus of coercion doing that, the only way to fight back is this kind of way that people like Ted Kaczynski and Luigi. He only did which of course whether it’s effective or not. At least it’s a gesture. So that’s that’s one way to think about it. And what would the other side respond then that there should be if you don’t want to live in this world where you’re being eavesdropped upon and your privacy is constantly being violated, you should what vote for the right? Come on.