A text dump on the UK governments response to leftist movements

Open letter to the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering

(Anti-)Anti-Terrorism & Counter-Information Projects

Introduction to Counter-Terrorism

Northern Ireland-related terrorism

Counter Terrorism Policing \ What We Do \ Prevent

Mixed, unclear or unstable cases

Concerns that a child or young person is being radicalised online

How children, young people and adult learners become vulnerable to radicalisation

ProtectUK — The Threat from Left-Wing, Anarchist and Single-Issue Terrorism (LASIT)

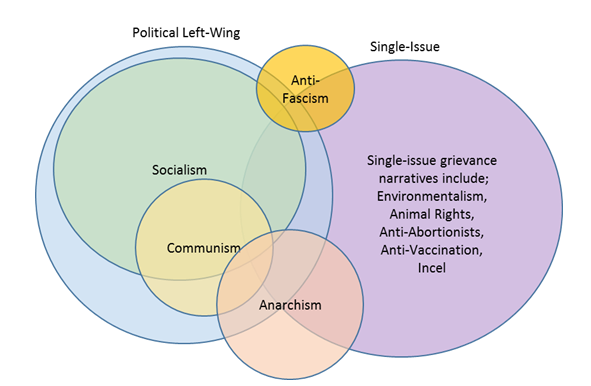

What is LASIT and what ideologies does it include?

What LASIT attacks have taken place in the West?

How does LASIT manifest in the UK?

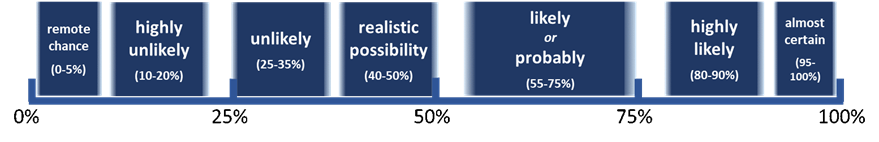

Probability and Likelihood in Intelligence Assessments

Education against Hate — Let’s Discuss: Extreme Left-Wing, Anarchist and Single-Issue Extremism

Examples of extreme left-wing, anarchist and single-issue terrorism

Where to find out more information

Far-left extremism: then and now

Open letter to the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering

Author: Return Fire Magazine

Date: March 27, 2024

Source: Retrieved on March 27, 2024 from returnfire.noblogs.org.

“The event aims to be an informal and self-organised gathering of activists, representatives and delegates from groups active in the prisoner solidarity / anti-prison / anti-repression struggle, one focused on the consolidation of international solidarity…”

– second call-out for the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering, Brighton

Hi comrades, known and unknown to us.

We welcome this initiative, and send our love and gratitude to all gathering in Brighton with the aim of together building a more durable and combative struggle against the authoritarian nightmare of the present-day. From the limits of our own capacity, we’d like to offer some thoughts; reflections that have been born from decades of shared struggle and over 10 years of publishing our magazines with a strong presence of anti-repression/anti-prison documentation and agitation. (This has included putting out texts and translations from comrades behind bars, sometimes with the direct participation of the prisoners themselves.) As limited and fallible as they are, they are what we have to offer: they are here for you and the comrades back in your own areas to do with as you will. Considering the international dimension of the gathering, we have tried to provide adequate context for those less familiar with recent cycles of struggle on these isles, and we have also brought our thoughts into conversation with other writings produced in the course of the struggle in past years, with their questions, analysis and proposals.

We will address some patterns and strategies of social control and State targeting of liberatory movements, and then make some observations and suggestions which might be slightly ‘up-steam’ of the more visible moments of police action itself, yet which we consider vital to the resilient movements we need to build, rather than only attempting to plug a hole in the dam with a finger of anti-repression work after the fact. This is especially important when we consider that police action is in fact ongoing at all times; understanding modern State philosophies of counter-insurgency allows us to see that repression is the norm, not the exception, and that in a very real sense it is not hyperbole to describe this as the latest adaptation of a permanent social war[1] – sometimes nearly invisible yet ironically total – being waged against the population by those who would govern it. This encompasses the repressive apparatus of the security agencies/military, cops and other State agencies down to the smallest level, together with the media, academic collaborators, corporations and recuperated civil society organisations, not to mention our own fear and suggestibility. (As Athina Karatzogianni and Andrew Robinson set out in their essay ‘Virilio’s Parting Song,‘ increasingly the (social-)mediascape allows repression to circulate horizontally, free-floating, self-managed.)

Comrades attending to themes of repression know as well as anyone that our efforts are not bound to the same cycles of rise and fall as the social movements that draw overt police attention (although indelibly linked to our own cycles as living beings, our own moments of extroversion and introspection). Rather, we constitute a base-line rhythm which allows the maintenance of memory, collective learning, support for those under attack, and the patient, inexorable return of pressure to the camp of the oppressor. Or, we fail in the attempt.

In the UK context, a lot has happened since the international Gathering Against the Prison Society in Brighton in 2009, standing as it did at the door of a following wave of dynamic action in the first half-decade that followed (student revolts, militant squat defence/eviction offence, a 2011 uprising across England following a racialised police execution, the return of a combative anarchist street presence in the pacified wasteland of the capital, anarchist attacks proliferating in the West Country, and more). Repression in its broader sense also moved forward with leaps and bounds; ramping up of police armament and surveillance architecture (perhaps most dramatically under cover of preparations for the 2012 London Olympics), various terror panics over the Islamic-identified “internal enemy,” the “hostile environment” policy of immigration management and its continued internationalisation via partnered detention schemes from Jamaica to (coming soon) Rwanda, a never-ending raft of new legal restrictions on taking to the streets or targeting infrastructures and updated in the era of COVID-19, renewed State attacks on travelling communities and squatting, prisons over-filled to bursting, academic collaboration refining an insidious ‘soft cop’ policing of protests until it is time for the hammer to strike, collusion with right-wing street movements, the surveillance operations of undercover officers being exposed and intimidating both those previously targeted and those aspiring to act.

While an in-depth analysis of those years will not be attempted here, it is vital for those who have lived through those times (and those that preceded them) to share lessons they have learned and reflections with other generations. The focus for the first part of this letter will be on one specific arrow the enemy has in their quiver, which has rained down on us at certain moments and looks likely to continue: that being, counter-terrorism legislation and framing. We regret deeply not appearing at the Brighton gathering this March 29th-31st to present the following thoughts in person, but in March 2021, the Dutch police raided and seized the servers of the NoState tech collective, taking down a variety of anarchist counter-information and prisoner solidarity pages such as Act For Freedom Now!, Montreal Counter-Info, 325, North Shore Counter-Info, and Berlin Anarchist Black Cross, in the context of an undisclosed ‘criminal investigation’. Although our website is not hosted by NoState and was thus unaffected, news has trickled back to us that the cops were also demanding any information related to our publication project, Return Fire. (Most of the above important webpages are now reopened on new servers, and we send our greetings and solidarity to them.) For now, we will make our contribution from the shadows.

(Anti-)Anti-Terrorism & Counter-Information Projects

“Anarchists, activists and environmentalists are targetted as “extremists” and “terrorists” with special police teams designed to infiltrate and dismantle their campaigns and organisations.”

– first call-out for the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering, Brighton

When, in May 2020, the domestic intelligence agency MI5 announced that they were taking over the monitoring and tracking of “domestic terror threats” within the UK from the police, it was probably only a matter of time until the new unit (LASIT; left-wing, anarchist, and single-issue[2] terrorism) would be testing its mettle – and doubtless seeking to justify its budget – by playing a public hand.

Labelling anarchists and other anti-authoritarian enemies of the ruling order as ‘terrorists’ is not a novel development, the term having been leveled – with varied levels of success – against rebels from the French Revolution onwards. In the 20th century, it was the Spanish State that really first brought a comprehensive ‘anti-terrorism’ policy to bear as a permanent tool in its arsenal, at first against Basque independence struggles but quickly also against (other) youth in any self-organised and combative demonstrations and sabotages it could allege to be the work of Basque ‘terrorists’. (Though it wasn’t long before the UK took up the theme regarding independence struggles in the British-occupied north of Ireland, and Germany did so against the Marxist-Leninist and occasionally autonomist/anarchist urban guerrillas of the 1970s plus those it could associate with them.)

“Since 1991 and the fall of the Soviet Union,” we can read in the text ‘A Wager on the Future’ by Josep Gardenyes, “the capitalist world system has lacked an oppositional dichotomy that can modulate and recuperate all dissident movements.” After the jihadist attacks of September 2001, it looked for some time that such a dichotomy had been found: that of democracy versus the figure of the terrorist. Under that sign was gathered all whom jihadists and other authoritarian groups managed to recruit (or among whom they attempted to, or that the State could allege them to…) from what remained of the broader anti-colonial movements after the (nominal) independence wars of the 1960s and 1970s and the most alienated and disillusioned of their children, including those in the West. What followed was its deployment on a truly international scale “as a conjunction of moral narrative, political discourses, institutional mandates, interstate connections, and juridico-military resources that any government allied with the global powers could make use of.”[3] What this looks like in practice ranges from unlimited surveillance to the fact that people can stay in prison for months or even years without clear accusation or trial and severe restrictions once released, not to mention social – or even literal – assassination.

During one of the earliest of the anti-terrorist cases which anarchists in France have faced, in 2008 you could read the following on a poster on the streets:

In this world upside down, terrorism is not forcing billions of human beings to survive under unacceptable conditions; it’s not poisoning the earth. It’s not continuing a scientific and technological research which everyday further subjugates our lives, penetrates our bodies and modifies nature in an irreversible way. It’s not imprisoning and deporting human beings because they don’t have an adequate little scrap of paper. It’s not killing and mutilating at work for the enrichment to infinity of the bosses. All that is called economy, civilization, democracy, progress, public order.

The media, as ever, have been instrumental in this effort, not least because of the level of public complicity that a charge like ‘terrorism’ requires (clearly a moral category they shape and promote rather than one ‘objective’ enough to include the endless list of State-inflicted or far-right/racist attacks), to achieve its task of not only neutralising individuals but of disciplining populations. But the media is not the only other non-State (or para-State) institution that plays and has played a significant role; we are talking about academics. Take the 2020 report published by Paul Gill, Zoe Marchment and Arlene Robinson of Univeristy College London’s ‘Department of Security and Crime Science’. In the paper, ‘Domestic Extremist Criminal Damage Events: Behaving Like Criminals or Terrorists?‘, these lackeys of the securitisation industry and cops specifically take the wave of anarchist attacks on a wide variety of corporations, State agencies, animal exploiters, fascists, transport lines, and communications infrastructure that has characterised the south-westerly city and environs of Bristol, England, during the last decade or two, and offers clear recommendations to the repressive organs of the State as to how to equate these sabotages – legally and propagandistically – with terrorism.

(Police efforts to apply the term so far in that area have been somewhat anemic, such as the confused and ambiguous interview with then-head of the unsuccessful[4] Operation Rhone investigation aired on a BBC documentary on the topic[5] after the iconic 2013 destruction-by-fire of the soon-to-open multi-million-pound police firearms training facility was described by the local Chief Constable as ‘domestic extremism’; that so far they had not found the actions to fit within the “clear legislation” of terrorism, but that “possibly” they were looking at a terrorist cell?)

Their analysis identified priority interventions for the cops as – among other things like increased stop-and-search and extensive forensic/DNA profiling, as we have seen in other anti-anarchist operations across the theatre of Europe this past decade in both legal and illegal forms – working with the media to portray anarchist and other liberatory movements that use direct action as “domestic extremism” (the term already in vogue but potentially falling from favour[6]) and then equivocate this directly to “terrorism.” They also specifically recommended targeting anti-repression networks and solidarity groups.

They needn’t of bothered; this is already old hat to a variety of States directly involved with repressing combative anarchism in the world today, though the prize for that task surely is a tie between Greece and Spain in that regard (with France as a runner-up). Where anarchists in those countries have succeeded in mobilising a counter-discourse against terrorism charges and their social validity, the criminal cases have sometimes fallen flat (to the investigators chagrin);[7] and worldwide, anarchist tensions within social movements and explosions of mass rage have often led to their destructive techniques spreading to be used by other exploited and rebellious actors rather than being contained by the repression. What we have seen increasingly, though, is State attempts to close down our means of digital communication and diffusion of our ideas on grounds of incitement, terrorist apologism, even hate-speech.[8]

Two of the three authors of the paper on anarchist action around Bristol, Paul Gill and Zoe Marchment, subsequently had their photos, phone numbers and emails circulated by anarchists.[9] Not yet have we seen responses to match those in territories claimed by the Chilean State, for example, where the following year anarchists smuggled a bomb into the National Academy of Political and Strategic Studies (ANEPE)at night on the eve of the commemoration of 2019–2020’s popular revolt in those lands, where they knew of “permanent academic activities intended for police forces, in terms of intelligence, investigative and counterinsurgency strategies. It is a repressive body under the Ministry of Defence which also shares knowledge internationally with States such as Spain, Colombia, Israel, etc. Different academics of this den of Power have written about anarchist practices and tendencies, trying to analyze our ideas, dynamics and proposals,” the responsibility claim reads. Previously last decade, other anti-capitalists exposed a member of Brighton’s own Leftist journal Aufheben, John Drury, as a long-standing academic collaborator with the cops, helping to devise policing strategies for protests. (Perhaps more disappointing was the reactions – or lack of reactions – from much of the movements he claimed to be supporting but was actually a parasite upon, earning his wages informing to the enemy.[10])

Our circles have benefited from various forms of using security culture to defend ourselves from policing and journalists; we need to go further and consider how to prevent being compromised by academics (or the communications technologies which we increasingly rely on and which the latter, like the cops, can easily access and analyse). We have to popularise this broad suspicion as far as possible in the movements we participate in (even when there are now an increasing amount of anarchist academics whose studies could benefit us but too often only end up in the hands of their supervisors, the State, and a tiny handful of other scholars). The scandal of recent years of the anti-fascist researcher Alexander Reid Ross, co-founder of the Earth First! Newswire and contributor to an anarchist academic journal, going on to work with former CIA and Department of Homeland Security agents for an ‘anti-extremism’ centre providing intelligence and analysis to technology companies, law enforcement and public officials (and which also produced a report on how anarchists use social media to “instigate widespread violence”,[11] comparing them to jihadis and right-wing militias) should bring this awareness to the fore.

Where the State succeeds in framing their blows against us as “counter-terror operations,” it attempts to ‘monster’, delegitimise and ultimately disappear our ideas and practices, at precisely the point when in many places across the world we are at the frontlines in messy and many-faceted struggles that can still be said to hold a glimmer of liberatory potential. Here in the UK previous generations have also faced this threat at times of heightened struggle; our minds go to the ‘GANDALF’ case that MI5 also backed a generation ago against our circles in an attack on Green Anarchist magazine due to its publishing of Animal Liberation Front (ALF) communiques (clearly intended as a dampener on a decade of generalised dissent and popular participation in ecological action), an example collective memory has failed to keep as alive in the present moment as it should.[12] However, on a global scale right now it is clear that, even if the paradigm of anti-terrorism is failing to stabilise the capitalist world-system as it is rocked by revolts, crises, pandemics and wars, it is in sporadic but systematic use against anarchists (amongst others) in most countries with sizeable anarchist movements.

The annual European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report (TE-SAT) released a new edition in December,[13] with the usual chapter dedicated to “left-wing and anarchist terrorism.” The authors express concern that “anarchist terrorists and violent extremists continue to pose a threat to public safety and security in the EU by damaging critical infrastructure resulting e.g. in large-scale power outages.”[14] They note a sharp increase in the number of Leftist/anarchist “terror” attacks in the year they studied compared to the year before, although they admitted that this may index to the fact of “changes in Member States’ classification of attacks as terrorist versus violent extremist.” They note that “anarchist extremists and terrorists in the EU place high importance on the legal and financial support provided to detained ‘comrades’.” The most common “offence” leading to arrest during the period in question, according to them, was not partaking in action, but “membership of a terrorist organisation.”[15]

Lest you imagine that simply not committing the more spectacularised acts of what the system projects as terrorism will protect you (or, worse, that denouncing other anarchists for “terrorist tactics” – such as the UK Anarchist Federation did following the 2012 knee-cap shooting of a top nuclear executive in Italy – will keep you safe), consider some of the deployments of terrorism charges of late.

In the Siberian territories claimed by the Russian State, three teenage anarchists were convicted for terrorism; for having ‘built’ a headquarters of the state intelligence service in an online game, then virtually ‘blowing it up’. In the US during the insurrection of 2020, the time-honoured anti-capitalist and anti-colonial practice of blocking trainlines is what has got some terror charges. Spanish police, according to the media, contemplate attack on a police station (during rioting itself sparked by the conviction of a communist rapper for ‘supporting terrorist violence’ when speaking of armed struggle, as another singer previously was for the same reasons) as grounds for the same.

As climate heats and ecological communities of life melt down, the hostage-takers at the helm of industrial society will be eager to use the hammer of counter-terrorism (as they never stinted from doing, even when it wasn’t already too late to stop the tipping point) against saboteurs, land-defenders and development-blockers trying to slow the accelerating catastrophe: witness the clamour from the German media and prosecutors over the recent wave of ‘Switch Off!‘ sabotage actions. Prosecutors in Turkey also recently referred anarchist detainees to the counter-terrorism office for incitement over published calls regarding State atrocities; however in that case the charges were also ultimately not brought down on them.

The European Union is considering putting anti-fascist groups on the list of those designated as terrorists (recall the 14 European Arrest Warrants requested by Hungary for German, Italian, Albanian and Syrian comrades, mostly yet to be captured), and Lina, an anti-fascist from Leipzig, was imprisoned on charges of having beaten some fascists, i.e., “having formed and being part of a criminal organization” under §129 of Germany’s criminal code; a.k.a, its Anti-Terror Laws. In Belarus, comrades who have taken responsibility for burning police stations and the like during the 2020 revolts there received long sentences on terror charges as a result as a clear disciplinary message to participants in the uprising, in a country where the death penalty has previously been applied in a terrorism case there. And if we’re not to commit the common error of forgetting the necessity of sustained and long-term solidarity, from Italy to the so-called US it’s already decades since some anarchist comrades have been under continual imprisonment because of ‘terrorism’ convictions.

The actions the prosecutors target seem to us, without fail, necessary and important contributions towards movements with teeth, able to take the offensive and also defend ourselves, imposing costs on the system for their moves against us and steady destruction of our lives, dignity and the Earth we both are and are of. And to us these acts are magnified when they hold resonance in a social context, going hand-in-hand with attempts to address our own needs and lives in a variety of contexts of struggle, refusal, and reconnection with the land and its many beings.

It is also our belief that combating the device of ‘anti-terrorism’ is itself a social process, because that is the terrain that ‘anti-terrorism’ tries to cut us off from by making us appear (to whoever is still fooled by the police spokespersons and their media or academic auxiliaries) as unrelatable, monstrous, fit only for extermination in the white cells of democracy; the oblivion of which they have been throwing those of various Muslim cultural backgrounds and Irish militants into on these isles for so long already with so little social opposition. The question we believe remains to be developed is, what strategies on the social level should we apply to prevent this enclosure, now and in the cases sure to come? How to use the opportunity opened by the repression not to close in on ourselves but to open a social conversation about the deployment of this discourse of terrorism and terrorists? Efforts in the past – looking to the international context – have ranged from “the State is the only real terrorist” to “we are all terrorists then!” How have these discourses aided or hindered, and in which contexts? Perhaps the Brighton gathering this month will collectively shed some light on this issue, with the attention both of those familiar with contexts of the UK and those with experience of counter-terror operations in other countries.

We think that counter-information platforms and publishing projects have a lot to think about here, not just because we offer a primary form of communicating our ideas and discourses which would challenge the terrorism narrative (though doubtless all anti-authoritarians need to be able to speak about these subjects with all the people in their lives, not just those who will pick up a magazine or read a blog), but because increasingly we ourselves are the target of the counter-terror operations, on the basis of incitement or providing instruction.

This is significant because – despite the large amount of brave comrades in jails across the continents for direct actions in many forms – law enforcement has long admitted that anarchist affinity groups are especially hard to penetrate, surveil and take out of action.[16] “The propagandists of Anarchist doctrines will be treated with the same severity as the actual perpetrators of outrage,” reads a declaration from the Spanish government in 1893 (during the heyday of the “propaganda by the deed” attacks on government and military figures and heads of State), and over a century later – having still failed to stem the anarchist insurgency by other means – this strategy seems set to continue. November 2021, the Italian State launched yet another wave of raids and charges against comrades in its claimed territories; they were accused of being another group that publishes a magazine it seems the police would rather didn’t exist. The charges? “Having constituted and promoted an association with aims of terrorism.”

It does not surprise us that the UK State is, like its neighbours on the continent, eager to repress the channels anarchists and others use to propagate our critiques and project our dreams. Attacks on publications and web-projects have been rising around the world, in both legal and extra-legal forms – comrades of the Indonesian Anarchist Black Cross (to give but one example) speak of how this “has been increasingly encouraged by the Indonesian Police, with initiatives such as the creation of a “cyber police” or social media police, with one of their aims being to isolate the spread of information not only from anarchist networks but also from other political dissidents and those who have the courage to criticize the state”:

The Indonesian Police from 2014 to 2019 have disbursed funds of ± 900 billion rupiah, which are used as funds for buzzers[17] to curb the spread and growth of counter-information media. In 2018 the Indonesian Police began to re-focus on the anarchist movement in Indonesia. Also, national police recently made a statement about banning media from covering police violence. However, we are sure that both individuals and groups who are focusing on counter-information and grassroots reports will continue to exist and grow. Given the severity of this situation in which all the tools of the State and Capitalism try to carry out silencing and repressiveness either online or physically, this is not the time to be silent and surrender ourselves to fear.

We do not agree with those who say that these repressive moves specifically target us because of the fear that the system feels from our actions and ideas in and of themselves; rather, it is when those practices manage to seep out across the social terrain, especially in moments of contestation, that our ideas become truly dangerous to the State and its order.[18] (For example, the EU “terrorism” report cited above worries about the increasing amount of violence targeting police stations, personnel and even their personal property: during the years when we have seen some of the most intense anti-police rioting of recent years, from France to the so-called United States, often in places with a history of anarchist anti-police agitation and action.)

For this reason, resisting the enclosure that repression always attempts (whether by the name of anti-terrorism or something else) is always more helpful than allowing the enclosure to do its work, even as we support those directly targeted. Lastly, making fighting repression into a social process rather than an anarchist specialisation also allows for the possibility of prisoner solidarity to become a practice for a wider section of society than our own resources can allow, sustaining us in combating the extreme isolation that terror suspects are often subjected to, and – just as importantly – allowing prisoners a greater possibility to continue to participate in some ways in the struggles that often led them to the cells in the first place, circumventing the efforts of the jailers and investigators to wear us down, hem us in and destroy us.

Terror charges are a way to strip struggles of intelligibility, of history, of context, reducing the accused to ‘bare life’ that can be done with as seen fit. How to we break out (discursively, spiritually, and of course ultimately practically) of the enclosure raised around us? At least in part, by improving our own intelligibility, history, context, and showing – not just telling – the values which give our lives meaning. Doubtless, beyond simply protesting the ‘excessive’ application of the term, a part of this ‘anti-anti-terrorism’ is too often disavowed by the more populist among us: that part is throwing the dichotomous partner of the dominant terrorism discourse – democracy – into the wastebin as yet another revolutionary dead-end or diversion, to be surpassed along with every other false dichotomy. (After all, which democracy hasn’t been built on a foundation of alienation, slavery, warfare and genocide: on terrorism, if you like?) Before the blackmail of totalitarianisms – democratic, communist, or fascist – revolutionary anti-state solidarity in words and acts.

The State here (and especially under the Conservative government) has for some time been pursuing a course of successively criminalising every form of rebellion or protest that even edges towards effective disruption of the status quo, a strategy that could be characterised as “shut up or blow up.”[19] When even the usual release-values of “democratic dissent” are stopped up (possibly because the global elite, bloated on its own arrogance since the 1960s, barely remembers a time when they were last forced to offer concessions due to powerful movements threatening revolution), we are sitting on top of a powder-key that seemingly could go off at any moment.

“In other words,” continues ‘A Wager on the Future’, “we live in a world where the powerful are trying to hide and to crush revolts, the desire for freedom, and revolutionary movements behind a curtain of antiterrorism”:

Antiterrorism is still convincing, it still mobilizes people and serves to justify more repression and control, but at the same time, this is a world in crisis, in which the majority of perturbed people, angry people, precarious people, are reluctant to trust either of the two poles of power. It is a dichotomy made to be taken apart, to allow us to again create a self-defined space of struggle and freedom. […] Yet it seems that few anarchists have taken notice that attacking antiterrorism, discursively and in practice, will not only decommission one of the most potent weapons in the state arsenal, it might also be our only chance of regaining our protagonism, self-defining a subjectivity of negation and rebellion, and projecting revolutionary paths in the coming years.

In the face of all this, it serves us well to ask how to proceed given that – as anarchists – we are not simply trying to attend to the ravages of repression after the manner of lawyers and human rights campaigners, but rather with an eye to fortifying the very struggles which the enemy is trying to shut down or preempt. Ultimately, the strongest base we have for resisting repression is neither a sound counter-discourse nor the most impenetrable security culture (though both are invaluable), but the maintenance of strong and well-rooted struggles themselves which can continue to give context to the cases of repression and allow those targeted by the State to continue participating, and it is to this – albeit still within the framework of our efforts countering repression – that we now turn.

Expanding Our Horizons

“In the face of escalated attacks against workers, young people, migrants and the living conditions of prisoners, we call for an encounter to learn how we can combine our struggle…”

– first call-out for the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering, Brighton

Combining struggles might be easier if we cultivated the ability to see the value in a symphony of complementary roles that each individual struggle, to be successful, must already contain. Yet more often than not this is not what we see in anarchist spaces. Either we find a valorisation of a couple of roles at most (mostly some variation of Warrior and Messenger) at the expense of all others, or we find the malignant heritage of the democratic imaginary in our spaces: everyone is expected to be able to do everything, to ultimately be interchangeable (to use the democratic parlance, ‘equal’). To be clear, more roles than this already exist, and have always existed, else we would never have survived this long as a tendency: but they often are neither valued nor developed (or rather, they are not developed communally and in complementarity, rather than as an individual project or even profession). Hence, we do not let them develop to their full potential. Those dedicated to tackling repression already know this; it is easier to find participation in the Warrior and Messenger roles than in those of attending to the emotional and practical needs of everyone impacted, tasks which are – not coincidentally – feminised in this society.

A recent Catalan text (forthcoming in English translation) by Josep Gardenyes, ‘Organization, Continuity, Community’, examines this exact dynamic. It lists a whole raft of existing modes of responsibility (sometimes more than one being fulfilled by the same person at some point of their life, but probably with a natural limit to how much time and energy one has to develop skills necessary for too many roles) which are visible once we really examine our spaces and struggles; fighters, healers, caretakers, builders, links, mediators, mediums, storytellers, and – at present – “be-theres”, those without as yet a defined contribution; and finally of course, ideologues who propagate justifications for their own current’s approach instead of actually performing any other role.

Many of these roles are necessary for multiplying the force of any struggle. This is impossible as long as any one element considers itself the most important; we have lived with the consequences of this arrogance for too long. The few healers among us are over-used and under-appreciated (for example, by the fighters who see themselves as the most vital or even sole agents, yet don’t know how to articulate their emotions or address the endless conflicts they generate around them). The healers, for their part, like the caretakers and mediators, end up turning to pacifist conceptions of struggle. The builders, mostly seeing themselves as the most pragmatic, have their pragmatism channeled away from the struggle (when they feel the model of their former comrades is simply to fight and get locked up for it, rather than anything “constructive”), and their efforts end up fortifying some charitable or otherwise non-revolutionary endevour. Does this sound familiar to anyone else?

Hence, we would like to bear in mind for the rest of this open letter that the basis of how we do what we do could ultimately be what determines the success – rightly identified in the call-out for this gathering as a necessity – of combining our struggles. We are convinced that this also holds keys to resolving difficulties and/or failures of anti-repression practice, both in specialised groups and as a sentiment (or lack of it) in the movements more broadly.

Before the Blow

“It’s time to stop wringing our hands and instead get organised. What do we have in common and can we build a common platform of action and discussion that helps us build a better world.”

– first call-out for the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering, Brighton

What framework do we have in mind when we speak of getting organised? To begin to answer this question, of course on the one hand we must have some kind of more specific idea of what the task at hand is. (That organisation must be a verb, a process of action, and not a static end in itself, was known to the comrades of the MIL and the OLLA[20] – that organisation is the organisation of the tasks of the struggle.)

For the purposes of what follows, without entering into justifications for this analysis, we will consider the basic needs of the current situation (at least in the circles we move in and know) as fitting within three themes. Namely, intervening in social conflicts, attempting to widen, deepen, and radicalise them (as we in turn are often radicalised by them). Rooting ourselves in the territories where we live and which we live as (obscured as this is by capitalism), including the land but also our histories and knowledge of how we came to be where and what we are. And, finding communal ways to address our vital necessities of life, away from the mediation of markets, State welfare, and colonial extractivism on any scale, and ensuring dignified survival in the face of attacks (pollution, borders, bosses, queer-bashing, gentrification, imprisonment, whatever it might be). Properly speaking, these three needs are not distinct but overlapping. Nonetheless some of our efforts will be more easily identifiable as relating to one or another of these needs.

Only once we have already established a provisional framework for what the tasks at hand are, and staked something in realising the projects to achieve those goals, is it necessary to discover which form of organisation will be most fitting for what we are already doing. Hence, each locality and tradition of struggle, with its own intensity of social conflict and internal dynamics, will have its own appropriate organising to address these three needs (or others): that is up to those who live in that reality to determine. To stay with the theme of repression, the strategies of State intervention will differ along with its interplay with media, culture, other social movements and tensions and more, and a valuable task for rebels would be to identify what those dynamics are in their own area.

But something that all comrades will have to face is how to address, realise, or resolve conflicts in their own circles and organisations. Again and again, we see reluctance or inability to do this hamstring efforts to organise. To not have dead words in our mouth when we speak of our dreams of a world without police or prisons, that has to change: not because – as some prison abolition activists might insist (and unconvinced neighbours might demand) – we must have blueprint solutions for a future we cannot yet know, but because they are the very means needed to carry collective struggle for prison demolition forward without faltering at every step.

For a start, we should accept that conflicts are not the exception, but the norm. Conflict is our companion through life, and is often clarifying, a means to grow and learn and change. Hence, when we fear and avoid conflict (or try to prematurely ‘solve’ it), we rob ourselves of this possibility. Not only this, but such discomfort can lead to people simply penalising whoever made the conflict impossible to ignore (thinking here of people who have been abused, or who simply cannot continue to ignore a shared problem). Others simply make the most of the situation to accrue points to their own status, without fundamentally changing the conditions leading to the problem.

It is a question of ‘when’ and not ‘if’ when it comes to a group needing to address conflict, and so we need to talk about it before the fact. To be able to take the collective opportunity, we have to envisage a process in which everyone involved is transformed in the process of a conflict, and not just reduce it to two or more individuals. This is very difficult in a culture which basically boils down to identifying good guys and bad guys, and justifying harm against the latter. There is, of course, an alternative: to pool our abilities and, through a healing process, we all grow together, and we don’t lose comrades.

But too often people simply prefer not to have to position themselves, or to expel the supposed ‘bad apple’ and leave themselves feeling clean. We need the ability to hold more levels of complexity than that, even (or especially) in the conflicts in which, as so often happens, one person has submitted another to harm and oppression. There is a further step to take beyond simply knowing all the theories around patriarchy, racialisation, and difference in its many forms: educating ourselves of the struggles against them, including how many of the resulting conflicts touch many intersections of power and privilege, and so are messy and complex, not black and white.

Only experience and intentionality will help us to see if someone (or, more likely, a social space) has caused harm and now seeks to respond to the suffering they have caused – and so will be willing to transform along with us – or they are a danger we must deal with otherwise, so as to protect ourselves. The former of these cases needs to be given the time it needs to play out; but the fear we have too often of conflict leads to people simply weighing up the resources or friendships they would lose depending on whose ‘side’ they would take (in situations often without the idealised duality of ‘abuser/abused’ when we are really honest) and then voting with their feet, not their self-professed values.

Weathering the Blow

What more does this have to do with repression? An attentiveness to counter-insurgency and other modern policing theories shows that the chief effect of repression is usually not the direct impact of the blow, but the fault-lines it opens up in the targeted group (or between the targeted group and other groups). If we are not practiced at how to deal with stressful situations, all too often the fault lines tear us from one another; and the tears often occur along the already-fraying parts of internal relationships, and map to power differentials that are best not left unexamined. Therefore, a holistic anti-repression practice to model will take this into account. Looking at how previous police operations affected each locality, how that was dealt with, and who reacted in what way, is without question a job that our enemies are conducting: we should not let them be the only ones to learn and adapt from that knowledge.

Many great resources are already circulated by comrades regarding how we should react in the face of repression (although updating the versions that exist with new information and legal/technological changes is always a valuable endeavor), from cultivating a wide-spread culture of zero-cooperation with law enforcement to dealing with overt or covert surveillance of our spaces. We are suggesting that attending to the quality of our internal dynamics should also be considered key before the hammer drops. This sentiment was shared by the reflection ‘Green Scared?‘, published in Rolling Thunder magazine in the confusion and paranoia in anarchist scenes of lands dominated by the United States following an extensive‘Green Scare’ anti-terror operation against activities of the ALF and Earth Liberation Front around the turn of the millennium, during which many former radicals collapsed under pressure and division and informed on each other:

State disruption of radical movements can be interpreted as a kind of “armed critique,” in the way that someone throwing a brick through a Starbucks window is a critique in action. That is to say, a successful use of force against us demonstrates that we had pre-existing vulnerabilities. This is not to argue that we should blame the victim in situations of repression, but we need to learn how and why efforts to destabilize our activities succeed. Our response should not start with jail support once someone has been arrested. Of course this is important, along with longer-term support of those serving sentences – but our efforts must begin long before, countering the small vulnerabilities that our enemy can exploit. Open discussion of problems – for example, gender roles being imposed in nominally radical spaces – can protect against unhealthy resentments and schisms. This is not to say that every split is unwarranted – sometimes the best thing is for people to go their separate ways; but that even if that is necessary, they should try to maintain mutual respect or at least a willingness to communicate when it counts.

Needless to say, many of you reading this will have experienced stresses coming from repressive situations, and seen people handling this more or less skillfully. (This includes conduct between prisoners and supporters, between co-defendants, etc.) The time to put skills into practice is now, not once the blow has already landed.

Recovering from the Blow

“Our communities are increasingly turned into open prisons, “a prison society”, through new technologies of social control.”

– first call-out for the International Anti-Prison / Anti-Repression Gathering, Brighton

The sadder truth is, that practically none of us had an experience of community in the first place. Why are we so weak that (acceptance of) the prison relationship so easily flourishes among us, when even societies under full colonial occupation or martial law managed to maintain more zones of resistance and insubordination than we see around us today on these isles and neighbouring countries?

Once again, many gathering in Brighton will be dedicating considerable effort already to prisoner support/solidarity efforts, but it is well known that this is not a general predisposition among our movements; it is often a specialisation (which while we do not necessarily want to reject, it is common knowledge that we want to involve more people in these practices). And the truth is that “we” (in this wider sense) are not good at prisoner support for many of the same reasons that we are not good at supporting each other in general. That is not solely an individual failing, but because here we live, breathe and eat capitalism, and shit out alienation.

There are many factors that amplify this alienation (neo-liberal dynamics penetrating even into resistance movements, the isolating effects of cybernetic technologies we are presently hostage to, patriarchal socialisation), but they are already known to many of you. Suffice to say that often we don’t know how to ask for help, we don’t know how to receive help, and certainly we don’t know how to give help; or on the contrary, we only know how to receive it as an entitlement or how to give it as a gendered, classed and/or racialised expectation, sabotaging liberatory potential in the act. So, overwhelmingly, we rely on the poisoned gifts of patriarchy and capitalism more than we rely on each other.

Until we are capable of transforming this sad fact, it is too early to speak of communities here: yet that is precisely what we need to struggle and survive. Not out of a romanticisation of the term: in fact, it is necessary to demystify it. Community is not the best thing ever. It’s not the solution to all problems, all loneliness, all frustration. It’s not everyone being of the same age and radical, sexual or temperamental persuasion. It’s just a body of imperfect people who share their survival. It is (at least sometimes) difficult, painful, life-giving and essential. Because it is how we can finally speak of destroying capitalism and the State.

There are glances of this potential to be had, even in Brighton: the organisational efforts to exercise mutual aid during the COVID-19 pandemic point to the ability to mobilise resources and connectivity, showing up the State as indifferent to our survival (let alone flourishing), when not an active hindrance. But, like Rhiannon Firth and others have cataloged, for the moment these initiatives only really take wing in the midst of disaster (manufactured or not), and can end up in the worst cases only supporting the return to isolated ‘normality’ while the neo-liberal State stands back: we have yet to treat everyday life as the disaster it truly is, marching us off the cliff of devastation and indignity.

“The varied attempts to create liberated communities cannot all be measured with the same ruler,” it is written in ‘Against Self-Sufficiency, the Gift‘ (by Sever), “but one failing that crops up pervasively in our present context is worth mentioning”:

Nowadays most people who have grown up with Western cultural values don’t even know what a community is. For example, it is not a subculture or a scene (see: “activist community” or “community accountability process”), nor is it a real estate zone or municipal power structure (see: “gated community” or “community leaders”).

If you will not starve to death without the other people who make up the group, it is not a community. If you don’t know even a tenth of them since the day either you or they were born, it is not a community. If you can pack up and join another such group as easily as changing jobs or transferring to a different university, if the move does not change all the terms with which you might understand who you are in this world, it is not a community.

A community cannot be created in a single generation, and it cannot be created by an affinity group. In fact, you are not supposed to have affinity with most of the other people in your community. If you do not have neighbours who you despise, it is not a healthy community. In fact, it is the very existence of human bonds stronger than affinity or personal preference that make a community. And such bonds will mean there will always be people who prefer to live at the margins. Whether the community allows this distinguishes the anti-authoritarian one from the authoritarian one.

Yet efforts to judge the communities we are trying to midwife into this world cannot fall into perfectionism; because perfectionism is incompatible with community in this sense. The tension shouldn’t surprise us: properly speaking, no community can coexist under the State, and so any that takes form under its reign is in a constant tension between expanding its autonomy and being liquidated. The only interesting question is where on that spectrum our efforts are at any one time, and how to re-adjust that balance, always pushing for the destruction of the State.

The consequences of this challenge for facing repression are apparent. Why, to take one example, did so many people in the Green Scare case turn informant? The theme is complex, but ‘Green Scared?’ notes that “[h]istorically, the movements with the least snitching have been the ones most firmly grounded in longstanding communities”:

Arrestees in the national liberation movements of yesteryear didn’t cooperate because they wouldn’t be able to face their parents or children again if they did; likewise, when gangsters involved in illegal capitalist activity refuse to inform, it is because doing so would affect the entirety of their lives, from their prospects in their chosen careers to their social standing in prison as well as their neighborhoods. The stronger the ties that bind an individual to a community, the less likely it is he or she will inform against it. North American radicals from predominantly white demographics have always faced a difficult challenge in this regard, as most of the participants are involved in defiance of their families and social circles rather than because of them. […] Here we see again the necessity of forging powerful, long-term communities with a shared culture of resistance; dropouts must do this from scratch, swimming against the tide, but it is not impossible.

[…] Healthy relationships are the backbone of such communities, not to mention secure direct action organizing. Again – unaddressed conflicts and resentments, unbalanced power dynamics, and lack of trust have been the Achilles heel of countless groups. The FBI keeps psychological profiles on its targets, with which to prey on their weaknesses and exploit potential interpersonal fissures. The oldest trick in the book is to tell arrestees that their comrades already snitched on them; to weather this intimidation, people must have no doubts about their comrades’ reliability.

Superseding the Blow

We stand before a crucial weakness our movements suffer, at least in the countries we know best: and more than a weakness, it is a tragedy, because it speaks to one of the few advantages that the enemy consistently enjoys in the social war. Once again, it goes deeper than a personal failing, although we all participate and have responsibilities and possibilities to overturn this condition. That disadvantage is the lack of continuity (generational, strategic, spiritual) in our struggles.

The State (and similar hierarchies), as James C. Scott has often emphasised, necessarily simplifies reality so as to be able to understand (that simplified version of) it enough to exert control. Often it is slow, parasitic, lumbering, unwieldy, imprecise. Our living webs of resistance and reciprocative survival – shifting, decentralised and chaotic (to reclaim a maligned term) – have proved infinitely more adaptable, intelligent and agile; this is one reason among many why it is vital to resist efforts to move us towards forms of organisation and imagination that more resemble those of the State itself, as is the proposal of the Left.[21] Yet this full potential is not realised, because the hegemony enjoyed by a confluence of the State, colonialism and patriarchy (and their capitalist consolidation then expansion) has managed to effectively break our transmission of knowledge and wisdom over the centuries. The result is that we are constantly starting again from zero when trying to break out of the dominant culture, without understanding how we came to be where we are: whereas the modern State maintains an almost-unbroken institutional memory of how to defeat us again and again, a memory they are constantly updating and refining.

Counter-repression organising sees this before us in the starkest and most depressing ways: often social revolt erupts, stones are thrown and police confronted, a new human potential emerges upon the barricades even from those we never expected. Then, after the rebellion has been crushed or bought off (or has simply burned itself out), that human potential dissipates back into routine, work, family, amnesia. What in other territories is achieved by genocidal levels of violence and intimidation is fulfilled just as efficiently (or more) by anti-depressants, social welfare, elections, media technology, and regular but sparing applications of policing, torture and imprisonment for those not yet pacified. We are left with prisoners of a war that nobody seems to even remember was raging weeks or months before, one that we are still fighting.

(Or, we thrust ourselves forward to attack – based not on an analysis of the conditions we find ourselves in, of our strengths and weaknesses, but on a fetishisation of abstract and unchanging principles – without heed for how the revolt can expand and extend itself by seeking solidarity from other social bodies. Sure enough, within a certain number of months or years, we are isolated by our need for security, by individualised survival strategies, the prison system, generational changes we haven’t worked out how to address, health break-downs and exhaustion. And, again and again, the line of transmission of our experiences across generation and phases of struggle is severed, and we’re back to reinventing the wheel.)

There are heroic efforts to keep that flickering memory alive (often dependent on forms of struggle that are not even recognised as such in the above scenario), and a vital part of that is not letting those repressed become forgotten (most importantly, including outside of our own circles): on that note, we can note the incredible continuity that the Brighton Anarchist Black Cross has maintained over the last decades, a rock in the UK prisoner support landscape, who perhaps will have something to say on this subject. In part, combating this amnesia has been a major goal of the format in which we release our magazine, Return Fire. The idea was to present something sizable and durable, less prey than slimmer and more frequent publications to be thrown away each year, with editorial explanations for those not already versed in our movements, to build collective reflection and memory you could find in one place when thinking about past years and cycles of struggle (as, in fact, has always been a focus in our ‘Memory as a Weapon’ column). Inspirational in this regard would be our eco-anarchist predecessors of the journal Do or Die, published from Brighton, who preserved records from otherwise-ephemeral sources of the ’90s/early ’00s struggles that the newest climate movements make so little reference to and learn so little from.

There’s a lot we could do differently to address this in our own movements (hints: not basing all our social spaces around the inclinations and rhythms of young militants alone, not modeling relationships that end up in self-isolating couples or criticism-allergic cliques, not managing conflicts so they only end in dynamics of win-lose or lose-lose…) But the memory we are talking about preserving or constructing cannot stay limited to our own small circles; it must draw breath in the streets, it must play on others lips as well. Anti-repression focuses have much to offer here, because – once presented in the messy and heterogeneous spaces where our potential comrades can be found – they can serve as a bridge to connect newer participants with those the State and media are attempting to isolate and annihilate.

As much was suggested by Peter Gelderloos’ ‘Diagnostic of the Future‘ when, writing in 2018 amidst a riotous US-wide prison labour strike and a resurgent far-right countered by those seeking a progressive democratic renewal, he asked “what are the positions that cut to the heart of the problem, no matter who is in power, while also speaking to the specific details of how power is trampling people down?”:

It is not that hard to conceive of a way to oppose state power and racist violence that leaves us ready, primed, and on our feet no matter who wins in November, and many anarchists are doing just that. As anarchists, we will always fight against borders, against racism, against police, against misogyny and transphobia, and thus we will always be on the frontlines against any right-wing resurgence. But are not borders, police, the continuation of colonial institutions, and the regulation of gender and families also a fundamental part of the progressive project?

The principal hypocrisy of progressives can often be found in their tacit support for repression, that unbroken chain that connects the most vicious fascist with the most humanistic lefty. That’s why it makes sense for anarchists to highlight the prisoners’ strike and to bring the question of solidarity with detainees from anti-pipeline struggles and prisoners from anti-police uprisings into the heart of any coalition with the left. If they want to protect the environment, will they support Marius Mason and Joseph Dibee?[22] If they think building ever more oil and gas pipelines at this advanced stage of global warming is unconscionable, will they stand with Water Protectors? If they loathe police racism, will they support the people still locked up after uprisings in Ferguson, Baltimore, Oakland and elsewhere, primarily black people fighting back on the frontlines against police violence?

Such an emphasis will separate Democratic Party operatives from sincere activists in the environmental, immigrant solidarity, and Black Lives Matter movements. It will also challenge the illusion that new politicians will solve these problems, and spread support for the tactics of direct action and collective self-defense.

We can also greatly deepen our understanding of repression in our areas and our resilience to it by making sure that older comrades (those with knowledge of the struggles and repression of previous decades) are still part of the conversation.

Considering that our struggles are at heart international (and turning this awareness into more than a simple slogan), forging meaningful connections with comrades in other territories is a necessity too. This gathering in Brighton is invaluable to support those links.

“Despite the advances in technology, radical communications has not kept pace,” as Eepa put it in ‘Building International Solidarity: Human Relations for Global Struggle‘; “Sure, many anarchics are aware of other struggles through communiques, news reports, or social media posts, but there is a deep rift between these casual interactions and meaningful relation building needed for resilient, effective, and meaningful struggle.”

They go on to emphasize the potentials that we only enjoy when such a network is under active maintenance and reinforcement, allowing us “to call for advice, to call for reinforcement, or to announce new projects of continental interest”:

Continental networks also act to ensure that the many varied regions, cultures, and political situations have a fast and effective means of reaching every other group on the continent, without relying on word-of-mouth, algorithms, or news releases.

[…] It can not be understated how much we can avoid stumbling blocks by learning from those who have been there and done that. International networks are also keenly important for ensuring that the relative wealth of even poorer comrades in the industrialized regions of the global north, gets shared with comrades in dire struggle with access to almost no monetary/material resources. We must find ways to ensure that we are getting funds and materials to the most dire struggles. This can only be done when we have developed resilient relationships with comrades across the globe.

Vital parts of this process of learning will be study of languages and of cultural differences, being observant and adaptive. “If you have a dozen comrades in your group,” Eepa reminds us, “you have enough people to learn lingua-francas for most of the colonized world”:

Everything you have in life starts with reaching. A toe dipped in the water before you learn to swim, your hand reaching out to grasp a rope you are about to climb, the raised hand in greeting of a new face. You take the first step by reaching out. Communications and solidarity is no different.

Taking this a step further, we can imagine an anti-repression network (or rather, many) of a city or region which not just keeps up to date on the struggles of anarchist circles in other countries or continents but actually commits to “partnering” with another one across borders. This could look like collectively raising travel funds to send comrades there to learn and share, keeping the relationships alive with long-distance communications and with repeat visits and hosting comrades from there here, always with an eye to sharing resources, contexts and ideas. What this would not look like would be how anarchist travel too often happens; basically as tourism, with the emphasis being on personal experiences (rather than on collectivising contacts we make with our struggles back home), spreading the stupider conflicts among us onto an international level, or – in terms of visiting countries with which our own exercises some variant of a colonial relationship – continuing to see our own countries as the centre of the world and being unable to listen and learn, let alone see the international entanglements of both the global system and of our struggles against it.

On the local level, the building of our capacities for genuine mutual aid back from the abyss we currently dangle over could be challenging ourselves to each connect with a willing comrade who is not already in our immediate circle – examples could range from prisoners, younger or older people, people who are parenting, people medicalised and/or suffering – and try to commit to a mutually-supportive, transformative relationship with them. (And them with us – the emphasis should be on mutuality, rather than charity, and each person who might fit the above descriptions should also think of who they could choose to support.) Perhaps over time this could expand to more than one person who isn’t already close to us, but we suspect that even engaging one person will be challenging enough for most people already (although those accustomed or expected to perform this kind of care already for gendered reasons will perhaps find it easy to “add” more people, in those cases creating a truly mutual – rather than extractive – relationship will doubtless be the more challenging part). But that could be a path to widening the scope of our relationships, expanding beyond what we are allowed access to under capitalist daily life.

Not Fearing the Next Blow

We know that we are likely to see more (and more intense) policing operations against our movements, our environments and friends, our families. We knew, since before we even became anarchists, what this society holds in store for the disobedient, the questioning, those with solidarity and will. The task ahead, ever trying to keep one pace out of reach of our annihilation, may lie not in obsessively avoiding the blow of repression if doing so keeps us isolated, or in obsessively returning the blow if doing so over-reaches and drains us. Rather, it may lie in superceding the blow (which, of course, given the circumstances could well include either avoiding or returning it!) on the social field: breaking the enclosure, and losing the fear.

Fear is natural and logical given what we know the enemy is capable of (often from personal experience and that of our loved ones). Fear can keep us safe in some circumstances, keep us sharp, keep up wary. It can also disable us, or lead us to seek false securities. For thousands of years, when they didn’t find ways to directly oppose them, our anarchic ancestors on all continents where States formed fled from them and often outlived them, keeping themselves and their anti-authoritarian rejection alive in the process, forging cultures in zones out of imperial reach. Now, as the last mountain and jungle vastnesses are brought under the map and the satellite (if not necessarily under control) and the seas rise to met us while the sky falls down on our heads, the task of destroying the State – not just attacking it, but superceding it in the process – could not be clearer.

Fear of the struggle will, in fact, keep us in greater danger; but to appreciate this, we have to think of ourselves as part of a larger social body struggling to be born, not as the isolated individuals repression aims to reduce us to when some of us are inevitably jailed. “So long as there are prisons,” according to one statement for the annual Week of Solidarity with Anarchist Prisoners, “the most courageous, sensitive, and beautiful among us will end up inside them, and the most courageous, sensitive, and beautiful parts of the rest of us will be inaccessible to us.” What will keep us strong – whether in the streets, under arrest or on the prowl from the margins – will be the social connections we manage to create; and which will creature us, in a constant process of becoming which we choose to call anarchy, here and now.

Because the fear we often confront, beyond the simple self-preservation of the flesh we like to call our own, speaks to the isolation and alienation we live in: we too often think that if we cannot create all the changes we need in the world at once, or at least in the course of our individual lives, we will have failed. Perhaps a part of the fear is the desire to not be seen to have been defeated, to have been overcome. But do we not carry the ghosts of every past struggle with us? Are they really so vanquished, or are they still there in the soil we feed from and eventually return to, the dreams we barely remember, the molotovs we throw and the arms we link? Will we not be there when generations we have yet to know assume the same tasks, defending or re-gaining the same freedoms; were we not always there? Or is the undead rationalist spirituality of capitalism – its religion of profits and loss, atoms and cells, borders and straight-jackets – the only imagination we have left?

Up with the Spring

Winter begins to turn her face from us, having let us take the opportunities – when we’ve been able – for introspection, healing, sharpening our weapons and theories. Now is the time for planting seeds and tending to them, whether those seeds are the letters we send across prison walls and borders, the fires we light under the structures and arses of our oppressors, or the memories we share so our multi-generational body doesn’t continue to be constantly ripped asunder by the march of capitalist daily life. We enter the aspect of Spring, of fruition, the popping of buds and imaginations. A time for renewal, stands taken and promises given.

Our affection and solidarity to each sincere heart which will beat in the presence of its kind in Brighton; we look forward to hearing the reflections and proposals of those comrades and more. Anti-repression will remain at the heart of any anarchism in movement, in rebellion, in self- and mutual-defence on a burning planet. We hope some of our provocations will relate to the concerns in this arena, and how it could sit with the rest of our lives as radicals. We hope this could be more fuel for collective conversations in which we identify our capacities, abilities and roles we can develop, finding a harmony between our desires and skills and the needs of others and the present moment; in other words, a shared survival, without which we can never speak in truth of liberation.

Strength and courage to all dignified prisoners and those on the streets.

Solidarity to the (other) comrades maintaining – or who have maintained – publications and counter-information websites under the shadow of the “counter-terror” regime and its disturbed dreams.

Let’s keep this fire from dying.

Until MayDay,

– R.F., Spring Equinox, 2024.

This essay also will be distributed in zine form as a companion piece – with an appendix in the form of the text version of Toby Shone’s phone-in from high-security prison to the debate “Thought and Action: Repressive Attacks on the Anarchist Written Word” held in El Paso Occupato, Turin (Italy), March 9th-10th, 2024 – to the final (double-)issue of Return Fire magazine, vol.6 chap6 & chap7, forthcoming.

MI5 Counter-Terrorism

https://www.mi5.gov.uk/counter-terrorism

Home > What we do > Counter-Terrorism

Introduction to Counter-Terrorism

What is terrorism?

Terrorist groups use violence and threats of violence to publicise their causes and as a means to achieve their goals. They often aim to influence or exert pressure on governments and government policies but reject democratic processes, or even democracy itself.

International terrorism

International terrorism from groups such as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and Al Qaeda present a threat from many others. They hold territory in places without functioning governments, making it easier for them to train recruits and plan complex, sophisticated attacks. Drawing on extreme interpretations of Islam to justify their actions, these groups often have the desire and capability to direct terrorist attacks against the West, and to inspire those already living there to carry out attacks of their own.

Northern Ireland-related terrorism

Northern Ireland-related terrorism continues to pose a serious threat to British interests. Although the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) has ceased its terrorist campaign and is now committed to the political process, some dissident republican groups continue to mount terrorist attacks, primarily against the security forces.

RWT/LASIT terrorism

MI5 took primacy for Right Wing Terrorism (RWT) and Left, Anarchist and Single-Issue Terrorism (LASIT) in April 2020. All terrorist threats arising from these ideologies are managed in the same way as our International Terrorism casework.

Countering terrorism

MI5 has countered terrorist threats to UK interests, both at home and overseas, since the 1960s and the threat has developed significantly since then. It’s challenging to understand the intentions and activities of secretive and sometimes highly organised groups. New and changing technologies make it increasingly difficult to obtain information necessary to disrupt the attack planning of these groups. Many are based in inaccessible areas overseas and there are limits to what can be done to prevent attacks planned and launched from abroad. Our techniques and the way we with work with other agencies both at home and abroad have to keep pace with the terrorists’ capabilities.

Counter Terrorism Policing \ What We Do \ Prevent

https://www.counterterrorism.police.uk/what-we-do/prevent/

We prevent vulnerable people from being drawn into extremism

Police have a long history of working to prevent vulnerable people being drawn into criminal behaviour. The government-led, multi-agency Prevent programme aims to stop individuals becoming terrorists and police play a key role.

We work with local authority partners and community organisations to help find solutions and work to support and protect vulnerable people.

Following assessment, many referrals to Prevent do not result in any further police action. In some cases other organisations such as health, forensic mental health, housing or education step in to provide support.

All referrals to police are handled with sensitivity and in confidence. If a person is assessed as being a terrorism risk, they may be referred to Home Office’s Channel Programme and maybe given help from a mentor.

UK Policing has a proud history of community engagement, and the success of Counter Terrorism Policing – just like other areas of policing – relies on the trust, confidence and support of all communities.

The Counter Terrorism Advisory Network (CTAN) is a national stakeholder engagement forum, which was formed by Counter Terrorism Policing in 2017. It is independently chaired, and its membership consists of survivors of terrorism, academics and researchers, a variety of faith leaders, and members who reach others through community organisations and groups – all of which are independent of policing.

Counter Terrorism Policing created the CTAN in order to speak directly and indirectly to those affected by terrorism, so they can be a ‘critical friend’ to policing and provide feedback on a variety of issues linked to Counter Terrorism strategy and policy. Consultation events and the contributions of members help to better understand the potential impact of policing activities and policies, and where necessary, to make changes to Counter Terrorism Policing’s approach.

Department for Education — Understanding and identifying radicalisation risk in your education setting

Published 24 October 2022

Applies to England

Contents

3. Mixed, unclear or unstable cases

5. How children, young people and adult learners become vulnerable to radicalisation

6. Risk factors

Print this page

To safeguard children, young people and adult learners who are vulnerable to radicalisation, designated safeguarding leads (DSLs) will need to take a risk-based approach.

The DSL should understand the risk of radicalisation in their area and educational setting. This risk will vary greatly and can change quickly, but nowhere is risk free.

To understand the risks or threats in your area, contact your:

-

Prevent coordinator or Prevent education officer in your local authority (if applicable)

-

HEFE regional Prevent coordinator (if you have one)

-

local policing team

-

local authority or safeguarding children partnership

-

local authority or police Prevent partners (for access to your counter-terrorism local profile)

The threat of terrorism

The Terrorism Act 2006 defines ‘terrorism’ as an action or threat designed to influence the government or intimidate the public. Its purpose is to advance a political, religious or ideological cause.

In summary, terrorism is an action that:

-

endangers or causes serious violence to a person or people

-

causes serious damage to property, or seriously interferes with or disrupts an electronic system

-

is designed to influence the government or to intimidate the public

The Prevent duty provides a framework for specified authorities to respond to the changing nature of threat in the UK. The government’s counter-terrorism (CONTEST) strategy 2018 says the main threat to the UK comes from Daesh or Al Qa’ida inspired terrorism, although extreme right wing terrorism is a growing threat.

Some groups and organisations are proscribed. This means they’re banned under counter-terrorism measures introduced under the Terrorism Act 2000 (for example, Daesh and National Action).

The Home Office has published a list of proscribed terrorist groups or organisations.

The extremism threat

The counter-terrorism (CONTEST) strategy 2018 defines ‘extremism’ as vocal or active opposition to the fundamental British values of:

-

democracy

-

the rule of law

-

individual liberty

-

mutual respect

-

tolerance of people with different faiths and beliefs

Extremism also includes calls for the death of members of the armed forces, whether in this country or overseas. Some groups and organisations that promote extremist ideologies are not proscribed terrorist groups or organisations.

These groups support divisive or hateful narratives towards others, but may not promote extreme violence. For example, they may hold views that support the distrust or hatred of people with different faiths or undermine the principles of democracy.

We have published resources to help explain:

Mixed, unclear or unstable cases