Alan J. Reid

A Philosophy of Gun Violence

Front Matter

Preface

I am not anti-gun. Let me be forthright about that. I view the gun as a burdensome technology that presents complicated ethical, moral, and philosophical convictions, but I also see the gun as a technological achievement with an impressive lineage of innovation that continues to this day. I respect the tradition and the constitutional rights of modern gun owners, and I acknowledge that the vast majority of gun owners are responsible and well-intentioned. However, I do believe there should be sensible restrictions on the types and number of guns that someone can own, who should possess guns, as well as the places that guns should be permitted. In doing research for this book over the last couple of years, I spoke with numerous experts who asked me why I wanted to write a book on guns. I was cautioned on more than one occasion that this pursuit would make me more enemies than friends. However, this is not simply a book about guns; it is a book about the intersection between humanity and the technological design of artifacts. The gun is a working proxy for this relationship.

To be clear, this book is not a personal opine on guns. It is not a condemnation of gun culture, a virtue-signaling social critique on gun violence, nor a textual handwringing over the epidemic of school shootings, violent crime, armed protests, or the militarization of police forces in this country, which are all underwritten by the gun. I do address the residual effects of the gun, but I do so through a philosophical meditation on the behavioral and persuasive design of the gun and the consequences that result from its use. I am channeling technology philosophers like Don Ihde, Neil Postman, Langdon Winner, and Bruno Latour, who argued that holding a gun fundamentally changes our outward perspective on the world, as well as the way that we view ourselves. Summarily, this book extends the argument that although people are not wholly exculpable, the function of the gun follows its form; in other words, the gun begets the gunner. When holding a hammer, we look for nails. When holding a gun, we look for opportunities to use it. This book deconstructs the gun as a non-neutral technological artifact and explores how it shapes the individual reality and behaviors of the holder, and by extension, argues that the gun creates more problems than it solves. Gun apologists view the gun as both a peacemaker and a peacekeeper, but by design, the gun is the antithesis to peace.

Whether we like it or not, guns are deeply rooted in the fabric of American society, and they are here to stay. People from all backgrounds use guns for many different reasons. Some go to the shooting range to hone their marksmanship (for sport and for self-defense purposes). Others shoot guns for therapeutic reasons, venting their frustration with something or someone that has wronged them. Some use guns to feel socially gratified and to identify with others through a shared interest, not unlike those who frequent the gym or the bar to fulfill the same human need for community and belongingness. Most claim gun ownership for self-defense purposes, though this bogeyman rarely materializes, and it is more likely that the gun fulfills its own self-prophecy of harm. Regardless of the reason for its use, the gun has been galvanized as an American institution, emblematic of freedom and autonomy, which compels us to view it as more than just a violent weapon. It is an artifact that carries with it a subtext of social, cultural, and political cache. The gun tells us a story; it is a text that is meant to be read by the user and by others.

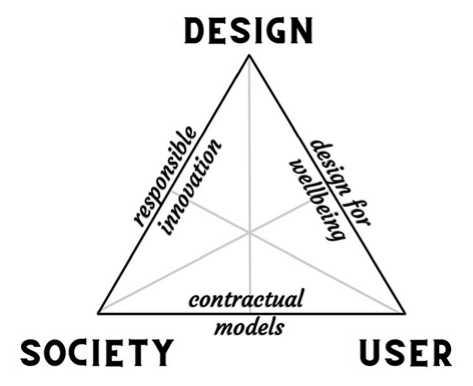

So, why write this book now? This past year, after a school shooting incident at a local high school, the school board responded by recommending that area schools install metal detectors at every entrance, increase the presence of armed School Resources Officers (SROs) on campus, and require all students to carry clear backpacks. There is serious talk about arming teachers in the classroom and proposed legislation to incentivize teachers with additional pay to do so. This misdirection has become commonplace following gun violence. More generally, as the rate of gun ownership increases and the instances of gun violence trend upwards, gun lobbyists and organizations simultaneously push to relax gun-carrying laws in public spaces. Therefore, I feel it is worthwhile to examine how guns impact not just the carrier, but everyone around him or her. It is necessary first to understand how the non-neutrality of guns amplifies dangerous behaviors and then evaluate whether this is socially, morally, and ethically corrosive in a modern civilization. It is obvious that the typical arguments for and against gun rights do little to convince either side. So instead, this book will cite a blend of philosophical approaches, including Don Ihde’s postphenomenology, Peter-Paul Verbeek’s philosophy of technological artifacts, and Bruno Latour’s ActorNetwork Theory as well as other theories of behavioral and persuasive design, to reveal the gun as an active force in individual use and decisionmaking. I use theoretical frameworks like Value-Sensitive Design (VSD), Responsible Innovation (RI), and Design for Wellbeing (DfW) to argue that gun manufacturers and distributors have a social and ethical responsibility to counter the gun epidemic by designing and selling a safer product. Let’s cut through the typical noise that surrounds the gun debate and concentrate instead on the one thing that is common in all gun violence: the gun.

At its core, the gun is a weapon of destruction—a killing tool—that facilitates homicide, mass murder, school shootings, accidental shootings, suicide, aggravated robbery, and intimidation. Critics of this book will be quick to point out that the gun also can save a life, prevent a robbery, provide food for a family, and create a sense of personal freedom and security, and they would be right. However, it is entirely dishonest to present these two views as being equivalent. It is not my intention to argue that all guns should be confiscated or abolished. It is the goal of this book to show the reader that guns, through their design, deliberately encourage and streamline purposeful behaviors and should be governed accordingly. Like many other technologies, guns are perceived mistakenly as neutral tools that bend to the will of their users. But the philosophy of technology shows us that guns are an inherently non-neutral and political artifact, predisposed for an intentional use: destruction. While most examine only the result of the gun use (how it is used), I present a nuanced interpretation of gun culture by rejecting the often-cited Value-Neutral Thesis and instrumentalist view of the gun, and instead, explain the lethality of the gun through various behavioral and psychological lenses (why it is used).

Chapter 1 of this book provides a survey of the current landscape on guns and gun culture in the United States, illustrating the gun epidemic that is uniquely American. Chapter 2 reviews philosophical frameworks that help explain the intersectionality of technology and culture. Chapters 3 and 4 present views on how the influence of technology might be perceived when personal choice and persuasive design collide. Chapter 5 delves into the constitutionality and politicization of gun ownership and use. Chapter 6 considers how innovation is redefining the gun as a technological object and weighs the implications for making guns even more ubiquitous and accessible in a civilized society.

Kure Beach, NC Alan J. Reid

Acknowledgments

This book was made possible by my wife, Alison, who gave me the assurance and support to write about this divisive subject, and by my four children, who I hope will thrive in a world where guns and gun violence are unfamiliar. I am thankful for those who spoke to me—on and off the record—for this book, providing a wide-ranging consortium of experts on gun culture, behavior, and design. Specifically, I wish to thank the following for their willingness to have an exchange of ideas: criminal researcher, John Lott; design guru, Don Norman; Stanford University professor, B.J. Fogg; and the French philosopher, Bruno Latour, whose work is the foundation for this book and whose words of encouragement mean the world to me.

About the Author

Alan J. Reid is Associate Professor of Writing and Instructional Technologies at Coastal Carolina University and an Evaluation Analyst and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Reid earned a PhD in Instructional Design and Technology and writes about the intersectionality of technological design and culture. His previous book, The Smartphone Paradox: Our Ruinous Dependency in the Device Age, was published in 2018.

List of Figures

Fig. 1.1 The Chinese hand cannon is an early ancestor of the moderngun (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/26591) 9

Fig. 1.2 The inside of a gun’s rifled barrel (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=rifling&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Rifling_of_a_cannon_(M75;_90mm;_y.1891;_Austro-Hungarian;_exposed_in_Ljubljana,_Slovenia).jpg)

Fig. 1.3 Rate of civilian gun ownership per 100,000 people in each ofthe G10 countries (Alpers, P. & Picard, M. (2021). Guns inthe United States: Total Number of Gun Deaths. SydneySchool of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, February 22. Accessed March 12, 2021. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compare/194/rate_of_civilian_fire-arm_possession/18,31,66,69,88,91,125,177,178,192)

Fig. 1.4 Rate of gun deaths per 100,000 people in each of the G10countries (Alpers, P. & Picard, M. (2021). Guns in the UnitedStates: Total Number of Gun Deaths. Sydney School of PublicHealth, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, February22. Accessed March 12, 2021. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compare/194/total_number_of_gun_deaths/18,31,66,69,88,91,125,177,178,192)

Fig. 2.1 A Cellphone Pistol is designed for concealment. Used withpermission (https://www.idealconceal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IC9mm-Photo-3-500x500-1.jpeg)

Fig. 3.1 A reversal of the script of the gun changes its perceived use(https://imgflip.com/memetemplate/47264806/Backwards-Gun)

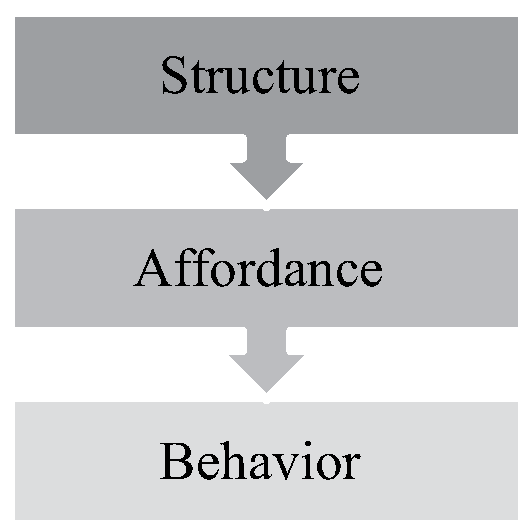

Fig. 3.2 An object’s structural makeup determines its affordances,which suggests behaviors

Fig. 4.1 Car decal depicting the gun family (https://www.flickr.com/photos/bryanalexander/40598428541/in/photostream/)

Fig. 5.1 A highly distorted set of data as shared by the official NRATwitter account (https://twitter.com/NRA/status/1465831902904995845)

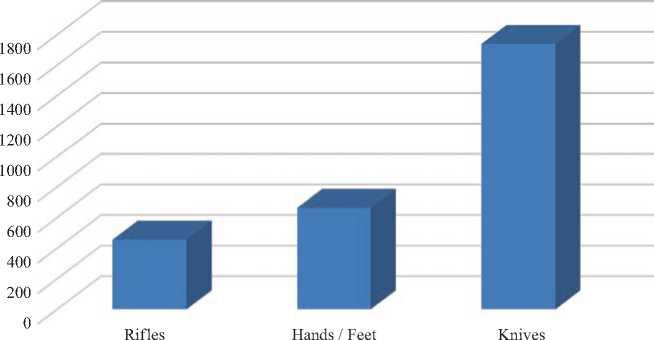

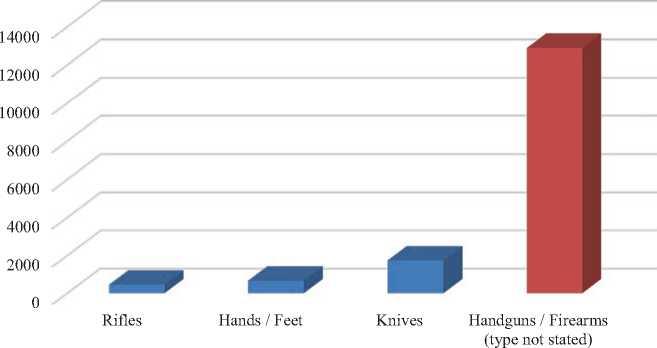

Fig. 5.2 Murder victims by weapon type (2020). Source: FBI CrimeData Explorer

Fig. 5.3 A donated rifle is forged into gardening tools. Used withpermission

Fig. 5.4 A proposed gun reform model

1. The Gun Problem

On December 14, 2012, in Newtown, Connecticut, a 20-year-old gunman walked unobstructed into the halls of Sandy Hook Elementary School, where he shot and killed 20 children and 6 adults before taking his own life. Sandy Hook, or the Newtown Massacre as it is sometimes referred to, was especially tragic because most of the victims were kindergarteners aged 6—7. Then-President Barack Obama would later recall the shooting at Sandy Hook as “the worst day of [his] presidency.” This day would remind us that life is fragile, and that evil knows no boundaries. It raised questions about the safety of school campuses. It fueled the conversation about a worsening mental health crisis. And it reignited the gun debate in the United States, which had seemingly gone dormant in the periods between previous shooting sprees like the Columbine school shooting in 1999 that killed 15 and the shooting at Virginia Tech University in 2007 that killed 33—the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history up to that point in time (there have been multiple mass shooting events that have since been even deadlier). The Newtown Massacre was indeed horrific, and every parent clutched their child a little tighter that night and before school drop-off the next morning. But what happened afterward was not at all unprecedented or even unpredictable, and not much has changed since.

What followed in the days after Sandy Hook was not unusual. Across the nation and the rest of the world, there was remembrance: Candlelight vigils were held for the victims and their families, there was a nationally televised ceremony in which all victims’ names were read aloud with the toll of a bell, and there were widespread calls for moments of silence. An online movement, Web Goes Silent, requested that all internet users abstain from all online activity from 9:30 AM to 9:35 AM on December 21, 2012: the one-week anniversary of the massacre. And while the town, the country, and the world mourned, the executive vice-president of the National Rifle Association (NRA), Wayne LaPierre, was in Washington, DC preparing his remarks to be delivered at a press conference later that day in which he would lay out his distastefully tone-deaf argument for strengthening gun rights.

Just days after 20 kindergartners and 6 adults had been murdered senselessly, LaPierre argued that it was the media—depictions of violence in television, film, and video games—that ultimately were to blame for the sociopathic killing that took place at Sandy Hook. He said, “As parents, we do everything we can to keep our children safe. It is now time for us to assume responsibility for their safety at school. The only way to stop a monster from killing our kids is to be personally involved and invested in a plan of absolute protection. The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”[1] In this press conference, LaPierre reiterated the same solution to gun violence that he had proposed in 2007, following the mass shooting at Virginia Tech University: “Put armed police officers in every school.” He would later extend this talking point even further, lobbying for a plan to train and arm schoolteachers in K-12 classrooms: “If we truly cherish our kids more than our money or our celebrities, we must give them the greatest level of protection possible and the security that is only available with a properly trained—armed—good guy.” This rhetorical argument is flawed for a few reasons but none more preposterous than the notion that the solution to America’s gun problem is that it simply does not have enough guns in the hands of its citizens. LaPierre’s circular logic was that the only way to protect ourselves from gun violence is with more guns. We must respond to violence with more violence.

The move by the NRA to bolster support for gun rights is standard protocol in the wake of a tragedy. In 1999, Charlton Heston, the NRA President from 1998 to 2003, organized a pro-gun rally in Denver, just miles away from Columbine High School, which had been the site of the nation’s deadliest school shooting only two weeks earlier. In 2012, George Zimmerman shot and killed teenager Trayvon Martin, sparking protest over the controversial stand-your-ground law in Florida, which the NRA would later describe as a “human right.” The NRA would deflect away from the issue of a vigilante shooting of an unarmed Black teenager and instead blame the media networks for “manufacturing controversy.”[2] In 2013, LaPierre appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press to argue that the shooting spree at the naval yard in Washington that happened just days before, which killed 12 members of the armed services, was because “there weren’t enough good guys with guns.”[3] Charles Cotton, an NRA board member, explained that the 2015 shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which killed nine people, occurred because of the political opposition to concealed carry. He wrote: “Eight of his church members who might be alive if he had expressly allowed members to carry handguns in church are dead.”[4] Unironically, the pro-gun refrain has become a predictable response to gun violence, and the NRA is a central figure in the gun debate that is resurrected in the aftermath of every tragedy.

It seems there is a fundamental disagreement on the role of guns in society. Some view guns largely as a destructive force that is responsible for more harm than good. Others embrace the opposite view that guns are the only true equalizer between good and bad forces and only by infusing more guns into the hands of do-gooders can we prevent gun violence. And it is this second, misguided view of neutrality—what we might refer to as instrumentalism—which this book is intent on debunking. Whereas gun advocacy groups such as the NRA loudly proclaim slogans like “Guns don’t kill people; people kill people,” technology philosophers largely agree that technology is non-neutral and that technological objects—such as the gun—color our experiences with the surrounding world. French philosopher Bruno Latour expanded on this concept of what he called technical mediation to describe the ways in which objects translate their uses to us through their design and, consequently, define our existences in the world. Importantly, technological objects change us in deep and lasting ways. They can mediate our understanding of ourselves and of others. So, objects—like guns—are not merely instruments or tools for us to use in completely detached ways based solely on whether we are good or bad individuals; they do not stand by passively as gun apologists tirelessly argue.

The gun issue is a deeply sensitive and divisive subject. The gun is not just a deadly weapon; it is an identity, a political tool, a virtue signal, an asset, and a liability. For many, it is the reason they lost a loved one, either to the prison cell or to the graveyard. Guns are simultaneously nostalgic and traumatic. This is why much of the conversation around guns is irrational and plagued with personal anecdotes rather than facts. But there are some logical questions that we should ask about our complicated relationship with guns. For instance, are guns truly neutral as many gun apologists argue, or do they residually impact our perceptions and behaviors in mostly negative ways? Do guns stoke violence rather than suppress it? And if so, are guns as necessary to our daily lives as they once were, or do they pose a burden to civilized society? By extension, if guns are shown to be non-neutral and positively charged for their use, and they distort the way we perceive reality, then shouldn’t this be reflected in the laws and regulation of these objects? As you have probably deduced by now, the central argument of this book is that guns do, indeed, negatively mediate our existence in the world, and this is not adequately reflected in gun policy or in much of the public’s perception of guns and their commonplace in American society.

Much of the misunderstanding of guns is derived from a false premise in which we look naively upon all technology as being neutral. We apply this view to not only guns, but social media, artificial intelligence, robotics, surveillance, and even biotechnologies. The general posture is that because technology can be used in good and bad ways, this makes it neither one nor the other. And the conversation usually skips forward from here, after everyone nods in agreement that technology is most certainly neutral and depends entirely on the user. But let’s take a step back for a moment and consider—just as many historians, critics, ethicists, and philosophers have before—that technology might be actively charged, and it is not as simple as categorizing it neatly into the “good” or “bad” column of the ledger. The First Law of Technology, as stated by historian Melvin Kranzberg, is that “[t]echnology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” This is a softened approach to the idea that we shouldn’t be talking about technology in terms of good or bad, positive or negative, but that technology simply is not neutral. And this nonneutrality might compel us in the direction toward good and bad behaviors.

When we talk about famous and infamous people, we typically develop a perception of that person and assign him or her a positive or negative value. For instance, would you consider Ghandi or Martin Luther King Jr. to be a good or bad force in society? Most people would identify these two men as iconic social justice warriors who positively shaped their societies. But perhaps some might point out the questionable views that Ghandi held toward women or the infidelities of Dr. King. Undoubtedly, these men are human, and that makes them imperfectly fallible. Similarly, Adolf Hitler is not praised for his artistic ability to paint with oils on canvas. To do so would be preposterous because it overshadows his true nature of evil. People are not and cannot be neutral; they are complex. They can do both good and bad things, sometimes simultaneously. Likewise, the technologies that are designed for a specific purpose cannot be neutral. They carry with them the original intent of the designer and an undercurrent of ethical values. For example, is a medical technology such as a pacemaker, which is designed to regulate the heartbeat and used to save lives, equally as neutral as a gun, which is designed for firing bullets and used so often to take lives? Clearly, technologies prescribe positive and negative directionality.

To further complicate the discussion around the neutrality of guns, we must consider what philosopher Don Ihde calls the multistability of objects. His view is that because technologies can be used in different ways, this ambiguity means that we can never really understand what a technology is all by itself. Instead, we must think of them as “technologiesin-use,” and this depends heavily on our cultural context. According to Ihde, our technologies (the gun, especially) have a “trajectory” for their use and promote their intentional design to the user. He calls this “technological intentionality.”[5] And while guns lack in the multistability of their design (a gun is highly unlikely to be used as a substitute for a paperweight, a hammer, a ball, or pretty much anything else besides a tool for firing bullets), its multistability is discussed in terms of its available use. In fact, a gun can be used to both perpetrate a school shooting and prevent one. And so here we are. We have arrived at a crossroads where even the most tragic events involving guns—even ones that involve young school children—fail to convince us that guns are not neutral. LaPierre and the NRA would like to limit the conversation on guns to the most basic view: that guns can be used for both good and bad, and it is the good guys who must prevail and can only only do so with the help of guns. This is a bad faith argument, a misdirection, and a fantasy. The question is not whether guns have multistability (as every technology does), or whether guns are neutral (which every technology is not). The discourse that surrounds guns should be refocused on the overall intentionality of the gun itself and its subsequent impact on its user. We must consider the totality of the gun, which is designed to be destructive, not constructive.

A Brief History

When you visualize a gun, what do you see? You likely are imagining a handheld automatic pistol or a hunting rifle. Or perhaps you envision the highly militaristic-looking but widely available semi-automatic AR-15. But these are modern iterations of ancient technologies. Guns, like all technologies, have evolved substantially over time. You probably did not associate the word gun with the matchlock gun—the preferred weapon of colonial American minutemen—or a much earlier ancestor of the modern gun: the Chinese hand cannon from the Yuan Dynasty in the thirteenth century. So, it is appropriate that we begin our discussion of guns with language.

The terminology that surrounds guns varies significantly. Aside from the obvious distinctions in how the English word “gun” is translated across different languages (“gun” ispistola in Spanish and Italian, vapen in Norwegian, arma de fogo in Portuguese, gewehr in German), the ways in which we talk about guns might sound differently based on age, upbringing, and even our own biases toward guns, in addition to our geographic location. And as I am a native English speaker and do not have a second language, we will look at how the terminology of guns changes throughout the English language, specifically.

Rhetorically speaking, our linguistic profiles are rooted mainly in our individual, social, and cultural experiences. If you served in the military, gun is a highly generic expression, and its use is strongly discouraged; weapon or rifle is the preferred term instead. When talking about statistical data and research, the term firearms is more professional and functions as a more inclusive descriptor. For the purposes of this book, the term gun has been chosen deliberately because of its vagueness and overall flexibility to be applied to various contexts, but it does have its limitations. For instance, would you consider an assault rifle a gun, or does it surpass the seriousness of the word? Is machine gun (a particular category of firearm) more provocative than gun? To this point, we must understand nuances in language that might attach different connotations to words and even specific types of guns. For example, the term pistol or six-shooter connotes a slightly less dangerous object than firearm or even gun. The word musket sounds even less frightful likely because of its inefficiency. An Uzi sounds deadly, but the phrase assault rifle sounds even more menacing. The FN Herstal Five-seveN™ semi-automatic pistol is known colloquially as the “cop-killer” because of its armor-piercing ammunition properties. Not surprisingly, this colloquial term is not received favorably by law enforcement. Slang terms like gat or piece are synonyms, and phrases like “strapped” and “packing heat” refer to an armed person. The etymological discussion is an important one. Technology critic, Neil Postman, explained that “technology imperiously commandeers our most important terminology. It redefines ‘freedom,’ ‘truth,’ intelligence,’ ‘fact,’,

‘wisdom,’ ‘memory,’ ‘history’ — all the words we live by.”[6] This could not be truer for guns, which are so closely aligned with autonomy, protection, and power. The way that we talk about guns, and the words we choose to describe them is indicative of who we are and what we believe. And just as the linguistic descriptions of guns have changed over time, so too has the technology of guns.

The answer to the question, “Where did the gun originate?” is not a straightforward one. First, we must define what we mean by gun. The most basic definition is a device that uses a controlled explosion to fire a projectile at an intended target. Military historians and weapons experts disagree on who is responsible for pioneering gun technology, when, and where it took place. A logical place to begin is by looking at when gunpowder was first invented, as this is a prerequisite for a functioning gun. According to Claude Blair in his book, European and American Arms, the Chinese were proficient in their use of pyrotechnics by the eleventh century. He argues, however, that this did not necessarily translate into gunpowder for use in propellants. Instead, he presumes that the earliest example of gunpowder used as an “exploding charge” in a weapon did not take place until hundreds of years later in the fourteenth century in Western Europe.[7] More recent studies have suggested even earlier, in tenth-century China, where “fire lances” were commonly used in battle. These handheld weapons resembled more of a flamethrower than a gun, but it most certainly bears an early resemblance to the handgun.

The Chinese later developed the hand cannon (see Fig.1.1), which was a handheld device that used explosive powder and a rod to pack a single projectile (usually an iron ball) into a bronze tube. The hand cannon was a miniaturization of its predecessor—the cannon—and did not utilize a trigger or any scoping or sight technology. Rather, it relied on a manual fiery ignition through a touch hole. Although it was less destructive, the diminutive cannon was highly portable and could be operated efficiently by a single person, unlike its parent technology. Its first known use was in thirteenth-century China, and over the next two centuries, the technological ideation spread quickly through the rest of Asia and the Europe.[8] In 1970, archeologists uncovered what is generally considered the world’s oldest firearm in the Heilongjiang province of China. This hand cannon is inscribed with the date of 1288, and hundreds of hand cannons from the same period have been unearthed since its discovery.

Fig. 1.1 The Chinese hand cannon is an early ancestor of the modern gun (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/26591)

By the end of the fourteenth century, descriptions of a portable hand gonne regularly appeared in French, German, and Italian historical documents. Some historians use the term “hand gonnes” interchangeably with the hand cannon, though the hand gonne typically was mounted onto a longer stick or pole. The driving factor for this innovation most likely was war, though fire lances and hand cannons gave Chinese warriors only a slight competitive advantage in battle because of their inefficient designs. This led to the next significant improvement in gun design: the invention of the matchlock.

In his book, The Complete Handgun: 1300 to the Present, Ian Hogg asserts that it was the Europeans who outfitted the hand gonne with a matchlock mechanism, which used a spring-loaded system to “thrust the match forward to make contact with the powder.”[9] In doing so, the shooter could focus intently on the target and not have to monitor the lighting of the gunpowder simultaneously. This important advancement simplified shooting from a multi-tasking procedure to a single-tasking one. Several more modifications improved the design of the gun throughout the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. From the matchlock to the wheel-lock to the flintlock, each innovation favored the shooter by improving the efficiency and overall usability of the gun.

As guns became more dependable, gunsmiths began experimenting with multi-chambered guns that could fire multiple rounds of ammunition in succession. There were two main methods for this: the doublebarrel, which simply joined two barrels side by side, and the “superimposed load,”[10] in which a single barrel gun could discharge several shots without reloading. The six-barreled 0.38 caliber (1780), duck’s foot pistol (late-1700s), 24-shot pepperbox (1790), and Collier five-chambered flintlock (1820) are all examples of variations of the superimposed load design. Shooters could now fire repeated rounds of ammunition with a portable pistol, essentially transforming the gun experience from a duel to a shootout.

Around 1825, Henry Deringer introduced a new brand of pistol, which quickly gained popularity as the first firearm for personal protection. Often stashed away in a pocket or in a boot, the gun reverted to a single-shot design though it was lightweight, reliable, and most importantly, concealable. Hogg writes, “Few wanted to burden themselves with the usual heavy pistol of the day, preferring to have something which they could conceal about their person, but which could be brought into play very quickly when the need arose.”[11] The pistol offered personal protection but also posed a new threat. Nearly undetectable, the Deringer meant that anyone could be inconspicuously armed. This was the case on April 14, 1865, when John Wilkes Booth walked into the Ford’s Theatre and assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at close range. The lone gunshot most certainly rang throughout the theater on that night and then proverbially throughout the rest of the world, but Booth’s attack had signaled an important flashpoint in gun history: After many centuries of innovation and diffusion, guns had become concealable and effortless, and this would forever change the way we perceive and read others in public.

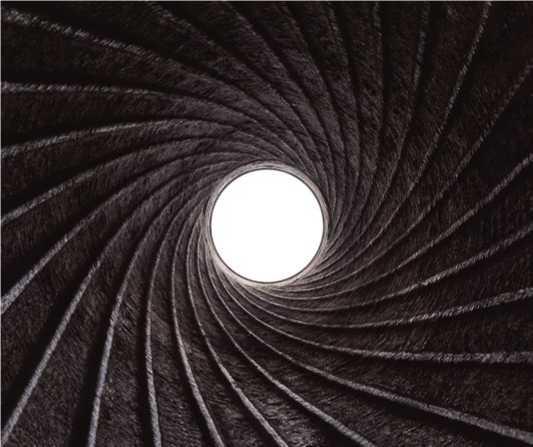

Gun technologies continued to make advancements over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but major leaps in innovations typically coincided with war efforts and often played a significant role in their outcomes. For instance, the combat that troops faced during the American Civil War (1861—1865) was changed radically by rifled weapons. Both the Union and Confederate armies adopted the rifled bore as its weapon of choice. Prior to the 1880s, guns were extremely imprecise and largely unpredictable. But a rifled gun would use spiraling grooves inside the barrel (Fig.1.2) to initiate spin on a bullet once discharged, greatly improving its accuracy and trajectory. (The rifling profile of a gun produces a unique signature for bullets; this would later prove to be extremely useful for forensic firearm examiners to match a bullet to the gun that fired it). This invention made guns more precise and, subsequently, more deadly. The rifled weapon also changed military strategy and tactics. Instead of large block formations of infantrymen facing off on an open battlefield, the rifled gun would force soldiers to take cover in trenches, a hallmark trait of World War I (1914—1918).

The next advancement in gun technology was focused on rapidity. A prototype for the modern machine gun emerged in the late 1880s, and it would revolutionize modern warfare from that point on. The Maxim machine gun was invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim, and it would come to later define the first world war as “the machine gun war.”[12] Today, machine gun designs copy the brilliance of Maxim’s gun, which used the pressurized gas from each cartridge to power the loading, ignition, and firing of the subsequent round. This combination of gasoperated belt-fed ammunition led to a sustained firing of more than 500 rounds per minute, though it required at least two people to operate. Still, the machine gun had effectively driven enemy troops underground because of its unrelenting assault. Trench warfare, as it would become known, described how opposing soldiers would entrench themselves in hand-dug ditches to draw cover from enemy fire during World War I.

Fig. 1.2 The inside of a gun’s rifled barrel ( https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=rifling&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns 14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Rifling_of_a_cannon_(M75;_90mm;_y.1891;_ Austro-Hungarian;_exposed_in_Ljubljana,_Slovenia).jpg)

Militaries found that firing long-range machine guns across the battlefield would create a problematic “no-man’s-land”[13] in the middle ground. To advance on the enemy, a more portable, individualized weapon was needed to counteract the machine gun fire. U.S. gun designer John Moses Browning responding by outfitting a rifle to make it fully automatic, allowing soldiers to traverse no-man’s-land while rapidly firing an entire magazine in roughly two seconds’ time. And this would provide enough support for troops to breach the enemy’s trenches, where they would employ the submachine gun that would become a favorite of mobsters and gangsters: the Tommy gun. The designer of the Tommy gun, John T. Thompson, referred to the gun as “the trench broom”[14] because of its ability to for quick bursts of close-range firing that swept out entrenched enemy forces. The gun had become even more deadly and even more mobile.

The M1 Rifle, also known as the Garand rifle, was the standard issue weapon for U.S. troops during World War II and the Korean War, but it remained popular globally for decades afterward. Designed by John Cantius Garand, the M1 rifle played a critical role on the Eastern Front of WWII. This practical, durable, semi-automatic weapon could endure the harsh conditions of Eastern Europe and was easy to disassemble, clean, and reassemble. Moreover, it was regarded as the most accurate rifle of its time. Competitive shooters would continue using the M1 throughout the 1950s.

The semi-automatic M1 Rifle was usurped by the assault rifle. The Sturmgewehr 44 is recognized as the first assault rifle, coming to fruition around 1944, but its successor persists today. The AK-47 (Automat Kalashnikov-1947) is not a precision weapon known for its accuracy, but it is extremely lightweight, impervious to harsh weather conditions, and capable of carrying a lot of ammunition. This menacing gun reigned throughout the Cold War and is one of the most ubiquitous automatic weapon types to exist today. Some estimates suggest that the AK-47 makes up about one-fifth of the world’s total number of guns in circulation,[15] and “[n]o weapon has been responsible for more deaths than the AK-47.”[16] Unlike the guns discussed previously in this chapter, the AK-47 bridges the battlefield and the boulevard. Its accessibility on the free marketplace makes this weapon more of a personal vice than a military armament. Today, a simple internet search yields a multitude of AK-47s available for purchase for around $1000. But in recent years, popularity has surged with the new generation of the military-style weapon: the AR-15.

The ArmaLite Rifle (AR-15) is a semi-automatic weapon that evolved out of the M-16 Rifle—the standard issue automatic weapon for U.S. troops in Vietnam. The AR-15 is believed to be the most popular style of semi-automatic weapon in the United States, but it has a troubling history of use. The term “AR-15” is actually a generic term used to described AR-style weapons that many different gun manufacturers offer, and not, in fact, an acronym for “Assault Rifle” as many assume. This style of weapon has been used in many high-profile mass shootings, including, but not limited to, the Las Vegas Massacre (61 dead), Pulse Nightclub Shooting (49 dead), Newtown Massacre (27 dead), and Sutherland Springs (26 dead). This has prompted strong opposition to the commercial sale of AR-15s for civilian use. In the wake of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, FL in 2018 (17 dead), several large retailers banned the sale of AR-style weapons in their stores, while others either discontinued the sale of ammunition from their shelves or raised the minimum age to legally purchase ammunition. At the time of this writing, there are ongoing legislative efforts to ban assault-style weapons such as the AK-47 and AR-15 in the United States, but these attempts have been unsuccessful since the Federal Assault Weapons Ban, a ten-year provision that criminalized the sale and possession of assault weapons and large capacity ammunition magazines, lapsed in 2004 under the Bush administration.

Throughout history, the evolution of the gun has been driven predominantly by war efforts. Whether by hand cannons or fully automatic assault weapons, the militaries that were equipped with the best firearm technologies often emerged victorious. And so, it was a matter of national security and prosperity that firearms were necessitated. But more recently, advanced weaponry such as the AK-47 and the AR-15 have become more symbolic than practical. More identity than self-preservation. More militaristic than patriotic. The only country in the world to feature a modern firearm on its national flag is Mozambique, which features an AK-47 as a symbol for defense, though many in the country view it as a hostile reminder of the country’s struggle with civil war.[17]

The AK-47 and AR-15 have become iconographic among gun enthusiasts, who use the image of the weapons as a credo for freedom, individualism, and autonomy. In the United States, the phrase “Come and Take It” can be seen printed on t-shirts, hats, flags, and bumper stickers on vehicles. The slogan usually features the silhouette of an assault weapon and is reminiscent of the popular saying by the former NRA president, Charlton Heston, who warned others that they could have his firearms only if they take them “From my cold, dead hands.” The catchphrase likely was adapted from an earlier slogan popularized by the NRA: “I Will Give Up My Gun When They Peel My Cold Dead Fingers From Around It.”[18] Similarly, the saying “Come and Take It” has been appropriated from its many uses throughout history. Its roots can be traced back to ancient Greece and the Battle of Thermopylae, in which the Spartan commander Leonidas refused to give up arms, saying “MOAQN AABE” (“Come and take them”). The phrase, roughly translated to Molon labe, has been a consistent refrain from gun apologists who perceive gun control measures as a threat to their personal liberties. “Come and Take It” appeared in numerous wars as America materialized, including the American Revolutionary War (1775—1783), and the Texas Revolution of 1835, and it is this deep connection to heroic revolutionaries and their arms that fuel the misguided “Come and Take It” movement of today. But modern gun apologists who invoke this phrase on the clothes they wear, the vehicles they drive, and the flags they fly, are not championing a noble cause as their forefathers once did; they are imposters who are only coddling a juvenile defiance to social progress. They are pseudopatriots who feel otherwise impotent without their weapons. They are not freedom fighters; they are slaves to the gun and the culture of violence that it creates.

Over time, the gun has transgressed from a mechanical marvel that fought and won wars to a hollow symbol of individualism and freedom.

In our modern technological age, the gun is not as necessary to our flourishment as it once was. Wars are fought in cyberspace, not in trenches. Hunting is a sport, not a means for survival. Ironically now, guns do more to create and foment the very threat that they supposedly eliminate.

An Epidemic

Every day in the United States, an average of 100 people die from gun violence.[19] To put that into perspective, this figure is roughly the same number of players on both sidelines of an NFL regular season game. Or approximately five K-12 classrooms. Or about the same number of musicians in a full-scale symphony orchestra. But quantifying gun-related violence and even gun ownership can be tricky, and at times, deceptive. Numbers vary widely on basic measurements such as the number of guns in circulation, the rate of gun ownership, and deaths-by-gun-related violence. As a result, the problem of establishing good and reliable data plagues the gun conversation; anti-gun and pro-gun advocates will often cherry-pick the most convenient data to support their arguments. Reports sometimes fail to disclose the criteria for inclusion of data, too. For instance, when talking about the number of guns in circulation, it would be most helpful to differentiate between military, law enforcement, and civilian gun owners, as there are obvious differences in motives for gun possession among these groups. Furthermore, statistics on the number of deaths by gun most certainly need to make a distinction between the types of death—suicide, homicide, accidental—and should clearly acknowledge whether the figure is a total number or per capita. The figure I cited at the beginning of this paragraph—100 gun deaths per day in the United States—includes intentional (homicide and suicide by gun) and unintentional or accidental shootings and is averaged from dividing the total population by the total number of annual gun-related deaths.

Keeping accurate data on gun violence and gun ownership is critical to public perception toward guns. John Lott is an economist who wrote the influential book More Guns, Less Crime (1998), which made numerous pro-gun arguments that he claimed to support with data. These claims persist today, including his denial of the link between gun ownership and suicide, that gun-free zones invite mass shootings, that unintentional shootings of children rarely involve other children, and perhaps the biggest lie of all, that “right-to-carry” laws reduce violent crime. Lott’s claims have been debunked repeatedly by researchers over the years, and his own methodology was rooted in bad statistical modeling choices, yet his writing has been perpetuated by pro-gun organizations like the NRA with impunity. The “more guns, less crime” hypothesis may have been flatly discredited by scholars, but it has been fruitful for Lott, who was appointed to the Department of Justice in the waning days of the Trump administration as a senior advisor at the Office of Justice Programs where he oversaw $5 billion in grant funding into crime research. A spokesperson for the Everytown for Gun Safety organization likened this federal appointment to “putting an arsonist in charge of the fire department.”[20]

Data that surround the gun conversation are sensitive. Numerous variables can misrepresent statistical data, such as the prevalence of gang or illicit drug-related activity in a specific region, socioeconomic conditions, and accessibility to guns, to name a few. And there is always the possibility that confirmation bias steers our interpretation of data toward a desired outcome. Despite all these external variables and discrepancies in statistical reporting, however, there are some truisms that cannot be ignored. For example, gun violence affects women, people of color, and other marginalized communities disproportionately, and where there is easier access to guns, there is more gun violence.[21] In other words: more guns, more crime.

The Small Arms Survey was established in 1999 to provide governments and lawmakers with reliable, impartial data on global firearms. Its strategic goal is to “maintain its role as a global centre of excellence on small arms, light weapons, and armed violence” and to “catalyse change through knowledge building and expertise.”[22] In its most recent annual report (2018), the researchers wrote that “civilians possess more than 80 per cent of the one billion-plus firearms in global circulation.”[23] The report noted a significant upward trend in the number of guns in global circulation, from 875 million in 2006 to more than 1 billion in 2017 and attributed this gain largely due to civilian purchases. Currently, there is a significant stockpile of guns in the hands of civilians all around the world.

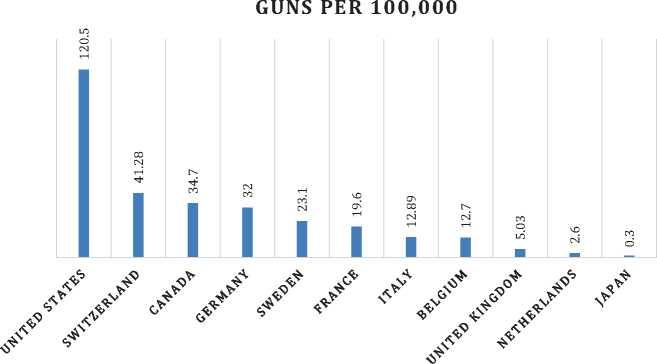

Unquestionably, the country with the most guns and civilian gun owners is the United States. (Note the use of civilian gun owner here; countries like Finland and Switzerland have compulsory military service and thus outfit all men over the age of 18 with a military-issued weapon, thereby skewing the per capita data on gun ownership). The Small Arms Survey reported that there were 393 million American civilians who possessed a gun: twice as many as the next four countries combined (India, 71.1m civilian gun owners; China, 49.7m; Pakistan, 43.9m). However, the United States falls fifth in line for the number of law enforcement and military holdings behind European and Asian countries. The United States has more guns than people, averaging 120.5 firearms per 100 legal residents, and the vast majority of guns are owned by civilians.[24] Or, to put it another way, the United States has 5% of the world’s population and 46% of the world’s civilian-owned guns.[25]

By contrast, peer countries of the United States have only a fraction of the number of civilian gun owners. The following chart represents civilian gun ownership in each of the 11 countries that are members of the G10, a cohort of countries that are like the United States in terms of socioeconomic development. Data presented in Fig.1.3 is from the most recent, complete year of data reported from each country.

Fig. 1.3 Rate of civilian gun ownership per 100,000 people in each of the G10 countries (Alpers, P. & Picard, M. (2021). Guns in the United States: Total Number of Gun Deaths. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy. org, February 22. Accessed March 12, 2021. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compare/194/rate_of_civilian_firearm_possession/18,31,66,69,88,91,125,177,178,192)

Currently, 2016 is the most complete year on record for statistical reporting of global gun-related deaths. Although numbers vary, it is estimated that between 195,000 and 276,000 deaths occurred globally in 2016 by firearms, and this estimation represents an overall decrease in global gun-related deaths since 1990.[26] However, the parameters of the gun-related death are significant. If we are looking at the total number of deaths by country, Brazil led all others with 43,200 fatalities in 2016. The United States came next with 37,200 lives lost to gun-related violence in that same year. However, if we parse the data by the per capita rate, then Brazil falls to eighth on the list; United States ranks 20th. In 2016, El Salvador saw a staggering 39.2 deaths by gun per 100,000 people (compared to the U.S. rate of 10.6/100,000), but researchers attribute these figures to the violent drug trade in this region, as well as in the next three deadliest countries: Venezuela, Guatemala, and Colombia. As such, the following chart depicts the rate of gun deaths per 100,000 people for each of the countries that belong to the G10, presumably all of which are peer countries of the United States (Fig.1.4).

Fig. 1.4 Rate of gun deaths per 100,000 people in each of the G10 countries (Alpers, P. & Picard, M. (2021). Guns in the United States: Total Number of Gun Deaths. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, February 22. Accessed March 12, 2021. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compare/194/total_number_of_gun_deaths/18,31,66,69,88,91,125,177,178,192)

This data can be unpacked even further. Although the United States significantly overshadows its peer countries in terms of ownership and gun-related fatalities, the majority of deaths can be attributed to suicide by firearm and not homicide. In fact, as of 2019, suicide contributes the most to the total number of gun deaths in the United States annually (7.29 per 100,000 people). Homicide by gun occurred at a rate of 4.38/100,000 people and unintentional or accidental shootings accounted for 0.15/100,000 people. In raw numbers, 2019 had a total of 23,941 suicides by gun, 14,389 homicides, and 486 gun deaths by accident. Although the United States does not have the most egregious gun-related fatality rate on the world stage, it does warrant special attention compared to its peer countries. It also should be pointed out that the medical care for gun wounds is far superior in the United States than in lessdeveloped countries, and this helps mitigate the number of gun fatalities. In this context, the United States has more guns and more deaths by gun ]]by an inordinate amount, and this provides a strong justification to understand why guns represent the worst in American exceptionalism.

Another uniquely American aspect of the gun problem is the number and frequency of mass shootings that occur. Data on this subject is heavily disputed by groups on both sides of the gun issue, as there is no consensus on the terminology used to describe mass shooting events. Mother Jones, which is self-described as “America’s longest-established investigative news organization,”[27] displays an active database of mass shootings that have taken place in the United States since 1982,[28] though they categorize a mass shooting event as having three or more fatalities. By contrast, organizations such as the Gun Violence Archive qualify a mass shooting where four or more people, excluding the gunman, are shot (but not necessarily killed). The FBI does not necessarily acknowledge mass shootings as a unit of measurement, but it does describe mass murder events, which are “described as a number of murders (four or more) occurring during the same incident, with no distinctive time period between the murders. These events typically involved a single location, where the killer murdered a number of victims in an ongoing incident.”[29] A mass murderer might include an arsonist or bomber, which clearly are different from mass shooters. In a 2019 report, the FBI referred to a mass killing as having three or more fatalities in a single incident, and this number excludes the shooter.[30] Referencing a shooter, specifically, implies that a mass killing hinges on a gunman, but this explicit language remains absent from official government records.

In fact, there are many other criteria that delineate the types of mass shootings that occur; since most mass shootings (killings of four or more) take place in private settings and among family members and domestic partners, we might differentiate between a mass shooting and a mass public shooting, such as the Virginia Tech University and Las Vegas shootings, which killed 33 and 61 people, respectively. Some shootings are discounted as a mass shooting event simply because the gunman wounded or maimed others but did not kill them. Events in which at least four victims were wounded but not killed also should qualify as mass shootings since this was the shooter’s intent. Using this measurement, the Gun Violence Archive reported 417 mass shooting events in the United States in 2019 where at least four people were shot (but not necessarily killed). In other words, by this definition, the United States averages a mass shooting event every day.

Still, using the most limited yet commonly relied upon definition of a mass shooting (four deaths in a single incident, excluding the shooter), the United States experiences 19 mass shootings each year.[31] And, a study conducted by researchers at the Harvard University School of Public Health, which analyzed data collected by the FBI, found that mass public shootings are occurring more frequently.[32] As the number of guns in circulation grows and as the world’s population increases, it is important to offer a contextualized view of these data. So, how does the United States compare to other countries? This question is difficult to answer, again, because of the inconsistencies in language and definitions. A country experiencing cultural conflicts might report a mass shooting as genocide; a country with political unrest might report a mass shooting as a political or terrorist attack. For these reasons and more, it is difficult to compare countries one-to-one. Even with the most conservative tabulations, however, the United States has an appreciably higher rate of mass shootings than other countries, though this does not seem to yield any real change in public opinion or in legislation.

In addition to the sheer number and frequency of mass shooting events, the United States emerges in stark contrast to its peer countries with its collective response to these events. Studies have shown that largescale mass shooting tragedies prompt an increase in the sale of firearms, depending on the degree to which the event is covered in the media.[33] In addition, gun sales increase nearly any time legislation is introduced that would infringe on gun owners’ rights.[34] In 2019, a lone gunman opened fire in a crowded Walmart store in El Paso, Texas, killing 23 people and injuring 23 others. The weapon of choice was the WASR-10, an AK-47style semi-automatic that is marketed for civilian use. Months later at the 2020 Democratic presidential debates, U.S. Representative Beto O’Rourke—who hails from El Paso—was asked to respond to the issue of banning certain models of guns, particularly those used in the El Paso Massacre. He responded, “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15, your AK-47 ... We’re not going to allow it to be used against our fellow Americans anymore.” This statement not only derailed his presidential bid but also outraged gun enthusiasts. Later that week, the NRA proclaimed O’Rourke the “AR-15 Salesman of the Month . possibly even of the year.”[35] This reaction might seem counterintuitive to other developed countries, which have taken meaningful actions in response to mass shooting events.

In 1996, following the Port Arthur Massacre, where a lone gunman used an AR-10 semi-automatic rifle to murder 35 people in Tasmania, Australia, Prime Minister John Howard quickly introduced sweeping legislation that would forever change the country’s firearm laws and make Australia the de facto case study on how gun control can reduce gun violence. The National Firearms Agreement (NFA) strengthened the licensing system for gun ownership and required applicants to have a “genuine reason” for owning a firearm; personal protection did not qualify as a justification for gun ownership. Automatic and semi-automatic weapons were banned completely. Prime Minister Howard also initiated a gun buyback program that decommissioned 650,000 firearms. Ultimately, intentional firearm-related deaths (both homicide and suicide) declined in Australia since the NFA was enacted, but new research suggests that downward trend of firearm deaths in Australia can be attributed to multiple legislative acts that occurred in the late 1980s and early

1990s and not just the NFA.[36] Regardless, Howard had successfully capitalized on a national tragedy to legislate guns. Twenty years later, the Deputy Prime Minister, Tim Fischer, reflected on Port Arthur after the Sandy Hook Massacre. He told a reporter, “Port Arthur was our Sandy Hook. Port Arthur we acted on. The USA is not prepared to act on their tragedies.”[37]

Earlier that same year, 1996, the Dunblane Massacre took place at a primary school in Scotland. In this shooting, the gunman used legally obtained handguns—not assault weapons—to kill 18 people. Like the Sandy Hook Massacre, most of the victims were young children aged 5-6. What resulted was the Snowdrop Campaign: a citizen-led grassroots petition for the banning of all handguns. (The Snowdrop was the only flower in bloom at the time of the massacre). Prime Minister introduced The Firearms Amendment Act of 1997, which extended the 1968 legislative act to ban “certain small firearms.”[38] Prime Minister Tony Blair later reinforced the amendment with the Firearms (Amendment) (No. 2) Act, which closed the loopholes for the types of lower-caliber handguns that could be legally owned, effectively banning all private ownership of handguns in the United Kingdom. In 2003, the Anti-Social Behaviour Act further clarified these laws, reclassifying air weapons and pellet guns, helping to clarify the data on gun-related incidents. Just as in Australia, the rate of firearm-related deaths and injuries has steadily declined in the United Kingdom, and most attribute this to the forceful regulation of guns.

More recently, in 2019, an active shooter killed 51 and injured 40 others in a terrorist attack on a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern immediately sprang into action, declaring in a news conference: “There will be changes to our gun laws.”[39] Indeed, the New Zealand government passed legislation within weeks of the massacre that outlawed all semi-automatic firearms. A second wave of legislation in 2020 tightened requirements for firearm license holders, requiring gun owners to document every sale or purchase of a firearm. Just as in Australia and Britain, a gun buyback program also was implemented. In a stark opposition to American gun culture, Prime Minister Ardern justified these regulations, saying that “[o]wning a firearm is a privilege, not a right.”[40]

Each of these cases represents empirical evidence that countries can take meaningful action in response to a mass shooting event and that these legislative efforts yield observable effects on decreasing gun violence. But this simply has not been the case in the United States. Rather, the American response to a high-profile shooting is a familiar one: There is widespread media coverage of the event that sparks national debate between proand anti-gun advocates, which only further entrenches each side in their own arguments. Politicians and activists call for gun reform; groups like the NRA hold rallies. Support for any legislative effort to curb gun violence slowly fades until the next mass shooting event, which in the United States, occurs every month or every day, depending on how you define a mass shooting.[41] This pattern of tragedy, sensationalized media, politicization, and atrophy always ends in a stalemate and has been aptly described as the “shooting cycle.”[42] Until this cycle is broken, there is a preventable epidemic that persists, and it starts with the gun.

Portrait of a Gun Owner

We cannot know for sure how many people own guns or how many guns are in circulation. To know this, there would have to be a well-kept federal database—or a registry—of gun owners in the United States. However, a government-based system of tracking gun owners spooks many gun enthusiasts who claim to own guns, in part, to defend against a tyrannical government that has overstepped its authority. To some, a federal gun registry is the first step on a slippery slope to authoritarianism. To others, a federal registry for guns would be no different than the one that currently exists for owning a vehicle. And even with such a system in place, this would not account for an underground marketplace that it would surely create. Regardless, the absence of a federal registry means that we must rely on self-report survey data to gauge current figures on gun ownership and demographics. Credible, unbiased organizations such as Pew Research Center, Gallup, and Quinnipiac University routinely poll randomized samples of Americans on basic demographic background and attitudinal questions about guns and proposed gun legislation. Researchers often take this data and extrapolate it to the entirety of the American public, but a major methodological limitation of these surveys is that they typically sample only a few thousand respondents. Federal agencies like the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and Explosives (ATF) provide more accurate reporting on retrospective data like the number of firearms licenses issued and import/export data for U.S.-based firearm manufacturers but do not collect attitudinal data. When all these data sources are cobbled together, an abstract view of gun ownership in the United States begins to emerge, but it is far from a complete picture. We can, however, synthesize multiple data sources and look at historical trends to better understand the seemingly basic question of “Who owns guns?”

It is extremely likely that either you grew up with a gun in the home, you currently live in a home with a gun, or you know someone who does. A 2017 Pew Research Center poll found that 42% of respondents indicated that they live in a home with a gun (of this percentage, 30% reported owning a gun).[43] This figure is slightly lower than the percentage of respondents who indicated that they had previously grown up in a home with a gun (48%). This may not be that surprising, considering gun ownership in the United States has been on the decline in recent years.[44] But a declining level of ownership does not equate to fewer guns. In fact, there are more guns in the United States than people. It is more common than not for a gun owner to possess multiple firearms; the Pew poll also found that two-thirds of respondents who owned a gun owned more than one, and nearly one-third of respondents reported owning five or more guns. People who like guns tend to really like them.

There are many reasons why someone chooses to own a gun. By far, though, gun owners cite self-protection as the primary motivator for keeping a firearm in the home.[45] A 2019 Gallup poll found that men and women were just as likely to identify protection (both self-protection and the protection of loved ones) as the most prominent reason for gun ownership, but ironically, research has shown that the presence of a firearm in a household may actually increase the likelihood of killing a domestic partner.[46] Aside from protection, the next most common reasons given for owning a gun include hunting (40%), recreation and sport (11%), and that the gun was passed down to them as a family heirloom (6%).

This question of “Who owns guns?” is nuanced, and the answers that I try to provide here are not generalizable to all individuals and populations. Indeed, there are many contributing factors that determine whether or not someone will own a gun, or whether this even was a conscious choice that was made (e.g., the recipient of a gun as a family heirloom). To be clear, gun ownership spans all ages, races, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds, and intelligences, but there are some variables that strongly influence whether someone will own a gun.

Gun ownership in adulthood often hinges on one’s childhood upbringing and previous socialization with guns. Gun owners, according to one study, were more likely to have grown up in rural areas where guns were prevalent or had attended a summer camp where shooting guns had been a recreational activity.[47] Moreover, these gun owners were more likely than non-owners to provide their children with guns, thereby perpetuating the cycle of ownership. In fact, guns are often bestowed upon younger generations through the passing down of family heirlooms.

Modern laws govern the minimum age for gun ownership, which varies by state and by gun type. Most states limit the purchase of a handgun until age 18, with some states postponing until age 21. The purchase of a long gun is less regulated by age, with fewer states imposing minimum age requirements to own. There are 30 states in which a person under the age of 18 can legally own a long gun (shotgun or rifle). The rationale behind these minimum age requirements takes into account the majority of suicides—by far—are committed with a gun, and that minors, specifically, have seen an 82% increase in gun-related suicides between the years of 2009 and 2018.[48] Although minors in most states are prohibited from legally purchasing and owning a handgun, federal law makes an exception to these regulations when there is “temporary possession” of the gun for directed activities such as target practice and hunting.[49] And, restricting the age limit to purchase and own a firearm is not the same as having access to a firearm. A 2015 study found that one-third of adolescent respondents lived in a home with a firearm that was loaded and unlocked, and 41% of adolescent respondents indicated that they had “easy access” and “the ability to shoot” the firearm.[50] Certainly, childhood experiences help shape attitudes toward guns later in life.

Alternatively, there is no upper limit to the age of someone who can own a gun. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that men aged 65 and older are the group at highest risk of gun-related suicide, followed by men and women aged 85 or older. Because elderly adults experience these higher rates of suicide, and because suicide is most commonly gun-related, there is a growing concern about a population of aging gun owners in the United States who have dementia or who are experiencing bouts of loneliness and depression and who have easy access to a gun. Research on persons with dementia, or PWD, found that 60% of PWDs live in a household with a firearm, and this number is expected to increase.[51] According to a 2017 paper titled “Armed and Aging: Dementia and Firearms Do Not Mix,” the authors point out that it is this potentially disastrous cocktail of cognitive decline, firearm accessibility, and the “prospect of loss of autonomy and becoming a burden upon relatives” that threatens this demographic, specifically.[52]

Gender also can predetermine the likelihood of owning a gun. According to the Pew Research Center, males are far more likely to have grown up participating in gun-related activities such as hunting and range-shooting than females,[53] and men typically receive their first gun at an earlier age than women.[54] These are strong predictors of future gun ownership. The gun experience for adolescent males seems almost a rite of passage; males generally participate in gun-related behaviors from an early age, including air soft guns, BB and pellet guns, and paintball. A quick walk through the toy aisles of a department store will confirm this stark difference between our cultivation of adolescent male and female proclivities. My son, who is nine years old at the time of this writing, has been the recipient of countless Nerf guns and ammunition as birthday presents from his friends and extended family members. His classmates regularly hold birthday parties at a popular local venue named Crossfire, which doubles as both an indoor paintball and a Nerf gun facility. The old storage warehouse now resembles a military-style tactical training course for urban warfare. Young children run rampant throughout the indoor space, wearing protective glasses, sniping one another with either paint or foam-based ammunition. The only rule is to not shoot each other above the neck, which is abandoned almost immediately after the timer begins. All is fair in love and Nerf war. Young males are born into a gun culture. In fact, I have two sons and two daughters, and I have yet to see either of my daughters receive a Nerf gun for a present or be invited to a gun-themed party venue. Women comprise only about a fifth of all gun owners.[55]

Although both men and women cite protection as the primary reason for owning a gun, women are far more likely to cite protection as the only reason.[56] Broadly speaking, women tend to be more pragmatic about gun ownership than men, seeing the gun as a means of self-defense. However, men identify gun ownership as being essential to their identity and to their personal sense of freedom.[57] Take, for example, bestselling author and editor-in-chief of the NRA’s magazine, Frank Miniter, who in addition to his books titled Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide and The Politically Incorrect Guide to Hunting, wrote The Future of the Gun, which fetishizes guns and gun culture. In it, he fantasizes about how guns liberate women:

Imagine a woman walking alone, at midnight. Under a streetlight’s glare are two men watching her. She doesn’t pause ... She is alone, sure ... But tight behind her belt is something small, but powerful. She has a gun of the future, a small, light, but deadly equalizer that takes fear from the night .

She lives in a free society, a city that gives her the ability to be equal to anyone. So she only shifts her eyes at the idle men as she passes. They’ve seen her before. She isn’t afraid. They nod respect. She’s free. Truly free. Truly equal . She knows the ultimate freedom is freedom from predation. That is the future of the gun. It is the future of freedom.[58]

Setting aside the gross misunderstanding that Miniter has about what it means to be “truly free” in this scenario, his view of guns is that they are the truest equalizer. That only by virtue of packing heat is this woman equal to these men. And notwithstanding the obvious Freudian interpretation of the gun as a phallic symbol here, this sentiment goes far beyond the boundaries of self-defense, and instead reinforces a chauvinistic view of women and their vulnerability. She is a damsel in distress, and only the gun can save her. The feminist perspective of gun ownership is slightly different. In the 2017 article titled “Gendering the 2[nd] Amendment,” the authors ask: “By exercising their Second Amendment rights, are they becoming more equal and empowered citizens, or are they acquiescing to a hyper-masculine culture that their reform-minded sisters have long sought to tame?”[59]

The Well Armed Woman, LLC (TWAW) is a website dedicated to educating, equipping, and empowering women gun owners. Founder Carrie Lightfoot describes her abusive relationship with her ex-husband as the motivation for creating the site. She notes the great divide between “women’s interest in guns and the male-dominated ‘camo and ammo’ firearm industry.”[60] Lightfoot understands that a relatively untapped corner of the gun market is the woman who feels a gun will make her safer; her online store features fashionably chic products like molded ear plugs, slim carrying holsters, concealed carry totes and clutches, concealed carry leggings and corsets, pink magazine loaders, jewelry forged out of spent ammunition, and a hat that reads “Fearless and Free.” It seems more fearful than fearless to walk around with a concealed handgun, in constant anticipation that you will be attacked, harassed, or predated at any moment. Yet, like Miniter, Lightfoot’s hat suggests that the gun shall set women free.

Not everyone shares in this freedom around guns. What of the “idle men” that Miniter describes in the above scenario? I wonder if they would feel free knowing that a female passerby nearly riddled them with bullets because she felt threatened. And, I wonder if this perceived threat would be impacted by the race of the men. More than any other racial group, Black adults view gun violence as a “very big problem”—more than twice as much as do Whites.[61] In fact, gun ownership is a very privileged position that benefits Whites. A study published by Cambridge University Press asked White Americans about their support for gun availability among White women and among Black men. They found that “priming white Americans with the thought of a Black man decreases support for gun availability, whereas priming the thought of a white woman increases support for gun availability.”[62] Deep racial biases affect how gun ownership is perceived but also govern how criminal offenders are prosecuted. According to the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC), the sentencing for firearm offenses disproportionately affect Blacks more than any other group. Black offenders are convicted at a higher rate compared to all others, are convicted more often on multiple counts of gunrelated charges and receive longer sentences on average for firearm offenses.[63] Gun ownership is a White institution that is rooted in systemic oppression and racism, from colonization to slavery, the Black Codes to the Jim Crow Laws, the suppression of Civil Rights to the inequitable application of the law today.

The racial makeup of gun ownership is exacerbated further by geographic location. The Pew Research Center reported that 46% of respondents who lived in a rural area own a gun, compared to only 28% of those who live in suburbs and 19% who live in urban areas.[64] Rural America is largely White; racial and ethnic minorities make up only about 22% of the U.S. rural population but 43% of urban areas.[65] Gun ownership is most prevalent in western, rural states. The top three states with the highest rate of household firearm ownership, by order of magnitude, are 1. Montana, 2. Wyoming, and 3. Alaska. The U.S. Census Bureau cites Montana and Wyoming as having more than 90% of residents who identify as White; Alaska has a lower percentage of Whites (65%) but the nation’s highest population of Alaskan Natives, which accounts for 15% of the state’s residents.[66] The northeastern region of the United States— Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—account for the lowest rate of household firearms. Further, views on gun rights are congruous with locality. Rural Americans largely oppose restrictions placed on guns, whereas urban and suburban Americans support tighter gun laws.[67] Guns mean something different for rural and urban Americans, just as they do for White and Black Americans.

Perhaps the easiest distillation of gun ownership in the United States is by political affiliation. It is mostly accurate to say that support for guns and gun rights typically falls along party lines. According to a Pew Research Center survey, Democrats showed more support than Republicans for banning high-capacity magazines and assault-style weapons. An even greater disparity exists between the two parties regarding legislation that would allow concealed carry without a permit and in more places. In contrast to their political counterparts, the majority of Democrat respondents opposed legislation to allow K-12 teachers and officials to carry guns in school.[68] Furthermore, Democrats support a federal database to track gun sales, which Republicans fervently oppose. Clearly, political affiliations are one way to delineate attitudes toward guns, but this is not universally true.

Members of both political parties can find common ground on some gun control issues. Both Republicans and Democrats largely agree on legislation that would prevent people with mental illness to purchase guns legally. And, there is consensus between the two parties that people on federal watch lists also should be unable to legally purchase guns. Although support for guns and gun rights is a central tenet of Republicanism, it is not an exclusively Republican behavior. A 2020 Gallup poll reported that 45% of respondents who identified as “Liberal” either lived in a home with a gun (45%) or personally owned a gun (15%). For Moderates, this figure was much higher; 70% of total respondents lived in a home with a gun or personally owned a gun.[69]