Alex Vadukul

‘Luddite’ Teens Don’t Want Your Likes

When the only thing better than a flip phone is no phone at all.

On a brisk recent Sunday, a band of teenagers met on the steps of Central Library on Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn to start the weekly meeting of the Luddite Club, a high school group that promotes a lifestyle of self-liberation from social media and technology. As the dozen teens headed into Prospect Park, they hid away their iPhones — or, in the case of the most devout members, their flip phones, which some had decorated with stickers and nail polish.

They marched up a hill toward their usual spot, a dirt mound located far from the park’s crowds. Among them was Odille Zexter-Kaiser, a senior at Edward R. Murrow High School in Midwood, who trudged through leaves in Doc Martens and mismatched wool socks.

“It’s a little frowned on if someone doesn’t show up,” Odille said. “We’re here every Sunday, rain or shine, even snow. We don’t keep in touch with each other, so you have to show up.”

After the club members gathered logs to form a circle, they sat and withdrew into a bubble of serenity.

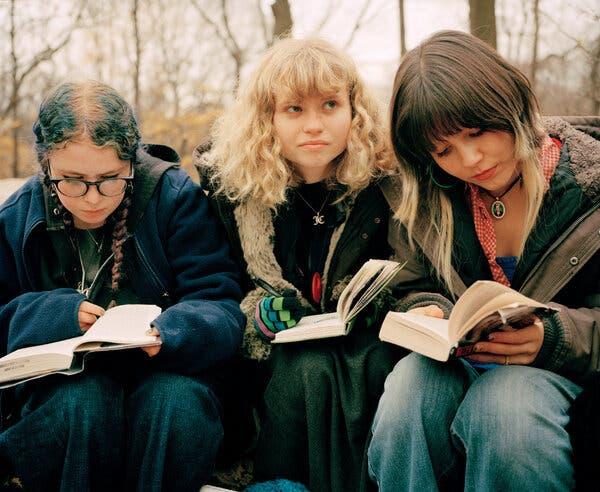

Some drew in sketchbooks. Others painted with a watercolor kit. One of them closed their eyes to listen to the wind. Many read intently — the books in their satchels included Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” Art Spiegelman’s “Maus II” and “The Consolation of Philosophy” by Boethius. The club members cite libertine writers like Hunter S. Thompson and Jack Kerouac as heroes, and they have a fondness for works condemning technology, like “Player Piano” by Kurt Vonnegut. Arthur, the bespectacled PBS aardvark, is their mascot.

“Lots of us have read this book called ‘Into the Wild,’” said Lola Shub, a senior at Essex Street Academy, referring to Jon Krakauer’s 1996 nonfiction book about the nomad Chris McCandless, who died while trying to live off the land in the Alaskan wilderness. “We’ve all got this theory that we’re not just meant to be confined to buildings and work. And that guy was experiencing life. Real life. Social media and phones are not real life.”

“When I got my flip phone, things instantly changed,” Lola continued. “I started using my brain. It made me observe myself as a person. I’ve been trying to write a book, too. It’s like 12 pages now.”

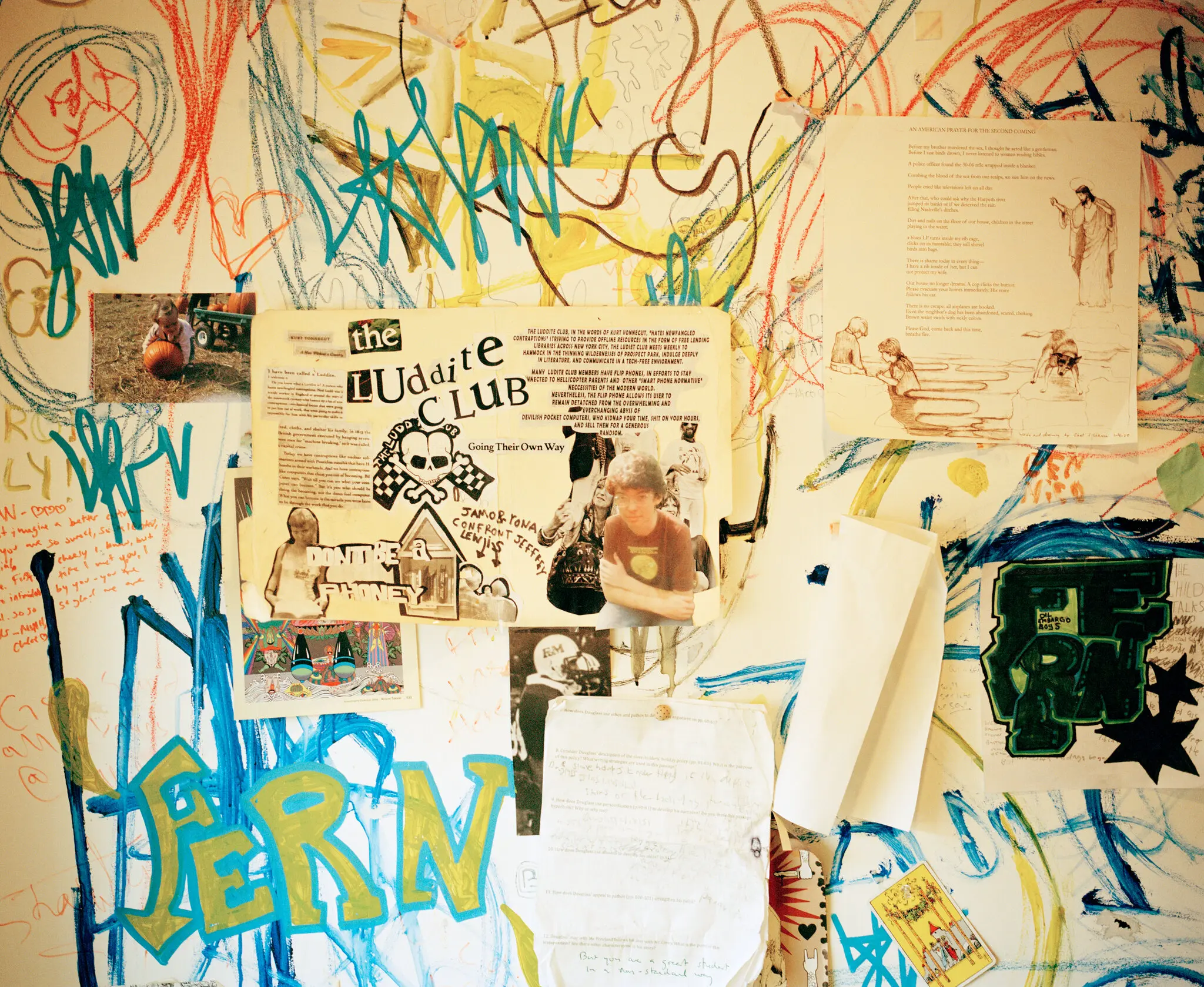

Briefly, the club members discussed how the spreading of their Luddite gospel was going. Founded last year by another Murrow High School student, Logan Lane, the club is named after Ned Ludd, the folkloric 18th-century English textile worker who supposedly smashed up a mechanized loom, inspiring others to take up his name and riot against industrialization.

“I just held the first successful Luddite meeting at Beacon,” said Biruk Watling, a senior at Beacon High School in Manhattan, who uses a green-painted flip phone with a picture of a Fugees-era Lauryn Hill pasted to it.

“I hear there’s talk of it spreading at Brooklyn Tech,” someone else said.

A few members took a moment to extol the benefits of going Luddite.

Jameson Butler, a student in a Black Flag T-shirt who was carving a piece of wood with a pocketknife, explained: “I’ve weeded out who I want to be friends with. Now it takes work for me to maintain friendships. Some reached out when I got off the iPhone and said, ‘I don’t like texting with you anymore because your texts are green.’ That told me a lot.”

Vee De La Cruz, who had a copy of “The Souls of Black Folk” by W.E.B. Du Bois, said: “You post something on social media, you don’t get enough likes, then you don’t feel good about yourself. That shouldn’t have to happen to anyone. Being in this club reminds me we’re all living on a floating rock and that it’s all going to be OK.”

A few days before the gathering, after the 3 p.m. dismissal at Murrow High School, a flood of students emerged from the building onto the street. Many of them were staring at their smartphones, but not Logan, the 17-year-old founder of the Luddite Club.

Down the block from the school, she sat for an interview at a Chock full o’Nuts coffee shop. She wore a baggy corduroy jacket and quilted jeans that she had stitched herself using a Singer sewing machine.

“We have trouble recruiting members,” she said, “but we don’t really mind it. All of us have bonded over this unique cause. To be in the Luddite Club, there’s a level of being a misfit to it.” She added: “But I wasn’t always a Luddite, of course.”

It all began during lockdown, she said, when her social media use took a troubling turn.

“I became completely consumed,” she said. “I couldn’t not post a good picture if I had one. And I had this online personality of, ‘I don’t care,’ but I actually did. I was definitely still watching everything.”

Eventually, too burned out to scroll past yet one more picture-perfect Instagram selfie, she deleted the app.

“But that wasn’t enough,” she said. “So I put my phone in a box.”

For the first time, she experienced life in the city as a teenager without an iPhone. She borrowed novels from the library and read them alone in the park. She started admiring graffiti when she rode the subway, then fell in with some teens who taught her how to spray-paint in a freight train yard in Queens. And she began waking up without an alarm clock at 7 a.m., no longer falling asleep to the glow of her phone at midnight. Once, as she later wrote in a text titled the “Luddite Manifesto,” she fantasized about tossing her iPhone into the Gowanus Canal.

While Logan’s parents appreciated her metamorphosis, particularly that she was regularly coming home for dinner to recount her wanderings, they grew distressed that they couldn’t check in on their daughter on a Friday night. And after she conveniently lost the smartphone they had asked her to take to Paris for a summer abroad program, they were distraught. Eventually, they insisted that she at least start carrying a flip phone.

“I still long to have no phone at all,” she said. “My parents are so addicted. My mom got on Twitter, and I’ve seen it tear her apart. But I guess I also like it, because I get to feel a little superior to them.”

At an all-ages punk show, she met a teen with a flip phone, and they bonded over their worldview. “She was just a freshman, and I couldn’t believe how well read she was,” Logan said. “We walked in the park with apple cider and doughnuts and shared our Luddite experiences. That was the first meeting of the Luddite Club.” This early compatriot, Jameson Butler, remains a member.

When school was back in session, Logan began preaching her evangel in the fluorescent-lit halls of Murrow. First she convinced Odille to go Luddite. Then Max. Then Clem. She hung homemade posters recounting the tale of Ned Ludd onto corridors and classroom walls.

At a club fair, her enlistment table remained quiet all day, but little by little the group began to grow. Today, the club has about 25 members, and the Murrow branch convenes at the school each Tuesday. It welcomes students who have yet to give up their iPhones, offering them the challenge of ignoring their devices for the hourlong meeting (lest they draw scowls from the die-hards). At the Sunday park gatherings, Luddites often set up hammocks to read in when the weather is nice.

As Logan recounted the club’s origin story over an almond croissant at the coffee shop, a new member, Julian, stopped in. Although he hadn’t yet made the switch to a flip phone, he said he was already benefiting from the group’s message. Then he ribbed Logan regarding a criticism one student had made about the club.

“One kid said it’s classist,” he said. “I think the club’s nice, because I get a break from my phone, but I get their point. Some of us need technology to be included in society. Some of us need a phone.”

“We get backlash,” Logan replied. “The argument I’ve heard is we’re a bunch of rich kids and expecting everyone to drop their phones is privileged.”

After Julian left, Logan admitted that she had wrestled with the matter and that the topic had spurred some heated debate among club members.

“I was really discouraged when I heard the classist thing and almost ready to say goodbye to the club,” she said. “I talked to my adviser, though, and he told me most revolutions actually start with people from industrious backgrounds, like Che Guevara. We’re not expecting everyone to have a flip phone. We just see a problem with mental health and screen use.”

Logan needed to get home to meet with a tutor, so she headed to the subway. With the end of her senior year in sight, and the pressures of adulthood looming, she has also pondered what leaving high school might mean for her Luddite ways.

“If now is the only time I get do this in my life, then I’m going to make it count,” she said. “But I really hope it won’t end.”

On a leafy street in Cobble Hill, she stepped into her family’s townhouse, where she was greeted by a goldendoodle named Phoebe, and she rushed upstairs to her room. The décor reflected her interests: There were stacks of books, graffitied walls and, in addition to the sewing machine, a manual Royal typewriter and a Sony cassette player.

In the living room downstairs, her father, Seth Lane, an executive who works in I.T., sat beside a fireplace and offered thoughts on his daughter’s journey.

“I’m proud of her and what the club represents,” he said. “But there’s also the parent part of it, and we don’t know where our kid is. You follow your kids now. You track them. It’s a little Orwellian, I guess, but we’re the helicopter parent generation. So when she got rid of the iPhone, that presented a problem for us, initially.”

He’d heard about the Luddite Club’s hand-wringing over questions of privilege.

“Well, it’s classist to make people need to have smartphones, too, right?” Mr. Lane said. “I think it’s a great conversation they’re having. There’s no right answer.”

A couple days later, as the Sunday meeting of the Luddite Club was coming to an end in Prospect Park, a few of the teens put away their sketchbooks and dog-eared paperbacks while others stomped out a tiny fire they had lit. It was the 17th birthday of Clementine Karlin-Pustilnik and, to celebrate, the club wanted to take her for dinner at a Thai restaurant on Fort Hamilton Parkway.

Night was falling on the park as the teens walked in the cold and traded high school gossip. But a note of tension seemed to form in the air when the topic of college admissions came up. The club members exchanged updates about the schools they had applied to across the country. Odille reported getting into the State University of New York at Purchase.

“You could totally start a Luddite Club there, I bet,” said Elena Scherer, a Murrow senior.

Taking a shortcut, they headed down a lonely path that had no park lamps. Their talk livened when they discussed the poetry of Lewis Carroll, the piano compositions of Ravel and the evils of TikTok. Elena pointed at the night sky.

“Look,” she said. “That’s a waxing gibbous. That means it’s going to get bigger.”

As they marched through the dark, the only light glowing on their faces was that of the moon.

Alex Vadukul is a city correspondent for The New York Times. He writes for Styles and is a three-time winner of the New York Press Club award for city writing and a three-time winner of Silurians Press Club medallions for his feature writing. He was a longtime writer for Sunday Metropolitan and has been a reporter on the Obituaries desk.