Allan R. Holmberg & Lauriston Sharp

Nomads of the Long Bow

The Siriono of Eastern Bolivia

1950

Also Available from Waveland Press, Inc.

Chapter IV: Exploitative Activities

Preservation and Storage of Food

Chapter VI: Routine Activities of Life

Chapter VII: Folk Beliefs and Science

Numeration, Mensuration, and Time Reckoning

Chapter VIII: Social and Political Organization

Chapter IX: Sex and the Life Cycle

Chapter XI: Some Problems and Conclusions

[Front Matter]

Also Available from Waveland Press, Inc.

Asebeubrcnner. Lifeline: Black Tami/ie.i in Chicago BilrtWt, BennhnrrC: The Modernization of a Spanish Villa gr ftartb. Nomads of South Persia: The Baum Tribe of the Khamseh Confederacy*

Bascom. The Yorvha of Southwestern Nigeria fizwo. The Ciberur Apache Bum, The Kalapalo Indians of Central Brasil Biuiien Mountain of the Condor: Metaphor rind Ritual in an Andean Ayllu

Bauman. Verbal Art ai Performance

Beidrlman, The Kaguru: A Matrilineat People of I uit Africa

Bernard-Pelto, Technology and Social Change, Second Edition

Blok. The Mafia of a Sicilian Village

Bohan nan-Curtin, Africa and Africans, T bird Id it ion

Carden, et al., Functions of Language in the Clauroom

C hinar. The Isthmus Zapotees: Women’s Roles in Cultural Context

Cohen. The Kanuri of Bomo

Crane-Augrosino, Field Projects in Anthropology: A Student Handbook. Second Edition

Davidson, Chicano Prisoners: The Key to San Quentin

Deng, The Dinka of the Sudan

de Rios, *Visionary Fine: Hallucinogenic Healing in the Peruvian Amozon

Downs, The Navaja

Dozier. The Pueblo Indians of North America

Dunn-Dunn, The Peasants of Central Buttia

Dwyer, Moroccan Dialogues: Anthropology in Question

Ekvall, Fields on the Hoof: Nexus of Tibetan Nomadic Pastoralism

Fakbouri, Kafr el-Elow; Continuity and Change of an Egyptian Community, Second Edition

Faron. The Mapuche Indians of Chile

Farrcr, Women arid Folklore Images and Genres

FflWer. Txintzuntzan: Mexican Peasants in a Changing World

Fraser. Fishermen of South Thailand: 7 he Malay Villagers

Freeman, Scarcity and Opportunity in an Indian Village

Friedl, Women and Men; 4n Anthropologist’s View

C.aniM, The Qemant: A Pagan-Hebraic Peasantry of Ethiopia

Garbn rino, Rig Cypress; A Changing Seminóte Community

Garharino, Sociocultural Theory in Anthropology; A Short History

Gibbs. Peoples of Africa*

Gmrli h. The Irish Tinkers: The Urbanisation of an Itinerant People. Second Fldltion

Gmrlch-Zcnner, Trban Life: Reading in Urban Anthropology, 2/E Gold, ‘st Pascal; Changing Leadership and Social Organisation in a Quebec Town*

Gimtrn, Ghamula in the World of the Sun: Time and Space in a Maya Oral Tradition

Mnlpcrn-Halpern. *A Serbian Village in Histórica/ Perspective Hanson, Rapan Lifeways: Society and History on a Polynesian Island Harris.

Catting Out Anger ReligUm among the Taita of Kenya Dickerson. The Chippewa and 7 heir Neighbors: A Study in Ethnohiitary*

Hicks, Tetum Ghosts and Kin

lloim)M-rg, Nomads of the Long Bow; The Siriono of Eastern Bolivia Holmcv,Schneider, Anthropology: 4»t Introduction, fourth Edition Isbell. To Defend Ourselves: Ecology and Ritual in an Andean Village Islam. A Bangladesh Village: Political Conflict and Cohesion Jacobs Fun City: An Ethnographic Study of a Retirement Community Jacobson. Itinerant ‘Townsmen Friendship and Soctal Order in Urban Uganda

Jones, Sanapia: Comanche Medicine Woman

Jones-Jones. The Himalayan Woman; A Study of Limbu Women in Marriage and Divorce kaplan-Manncrs. Culture Theory

Rea roes. The Winds of íxtepeji: W orld Vieu> aud Society in a Zapotee Town

Klaiu, East Indians in Trinidad: A Study in Cultural Persistence Klima, The Harabnig: F.ait African Cattle-Herders Rolenda. Caste in Contemporary India: Beyond Organic Solidarity i.a Flamme, Green Turtle Cay: A n Island in the Bahamas I.er, Freedom and Culture

Lee, Valuing the Self: What We Can Learn from Othes Cultures

L.es»a, L’lithi: A Micmmeskm Design for Living Locwen, The Mississippi Chíñete: Between Black and White, 2/E Lofland. A World of Strangers: Order and Action in Urban Public Space

Lyon. Native South American! Ethnology of the Least Known Continent

Malinowski. Arganauti«»/ the Western Pacific McCurdv-Spradlcy, live in Cultural Anthropology: Selected Reading

Mel ee, Modem BUwkfeet: Montanans on a Reservation Messengrr, hits Brag: hie of Ireland Middleton. The Lugbara of Uganda

Mitchell. The Bamboo Fire: .4n Anthropologist in .Ven’Guinea. 2/T Moore, et ai., The Biocultural Basis of Health: Expanding Vieu.« of Medical Anthropology

Nash, In the Lyes of the Ancestors. Relief and Behavior in a Mayan Communitf

Netting, Cultural Ecology, Second Edition

Norbeck, Changing Japan, Second Edition

Norbeck, Religion in Human Life

Ohnuki-Tierney, The Arms of the Northwest Coast of Southern Sakhalin

Ottenheimrr, Marriage in Domoni: Husbands and Wives in an Indian Ocean Community

Pandian, Anthropology and the Western TraditionToward an A uthentie A nthrofmlogy

Partridge, The Hippie Ghetto; The Natural History of a Subculture

Peho, The Snowmobile Revolution: Technology and Social Change in the A retie

Preston. Cult of the Goddess: Social and Religion Change in a Hindu Temple

Quintana-Flovd. ¡Que Gitano f: Gypsies of Southern Spain Read. Children of 7 heir Fathers; Growing Up among the Ngoni Reck. In the Shadow of Tlaloc: Life in o Mexican Village Richardson. Son Pedro. Colombia: Small Town in a Dexeloping Society

Kohnrr-Bcttaucr, The KwakiulU Indians of British Columlna Kosenfeld. “Shut Those I hick l ipil”: A Study of Slum Sc hoot failure Rusntan-Rubei. Feruling ¡nth Mine Enemy: Rank and Exchange among Northwest Coast Societies .Saizraann-Scheuflrr. Komarov: A Czech Fanning Village Schaffrr-Cooprr, Mandinko: The Ethnography of a West African Holy lutnd

Spmdler, Being on Anthropologist; Fieldwork in Eleven Culture.

Spindlrr, Culture Change and Modernization; Mini-Models and Case Studies

Spindler. Doing the Ethnography of Schooling: Educational Anthropology in Action

Spindler, Education and Cultural Process: Anthropological Approaches, Second Edition

*Spiedler-Spindlcr, flrenmen With Poner: The Menominee

Spradlev, Culture and Cognition. Rules, Maps and Plant

Sutherland, Gypiies: The Hidden Amrricam

Thomas, Refiguring Anthropology: Firtt Principles of Probability and Statistics*

Tylcr. *Cognitive Anthropology

Tyler. India: An Anthropological Perspective

I’nderhill, Papago Woman van Beek, The Kaptiki of the Mandara Hills Vigil, From Indians to Chícanos: The Dynamic of Mexican American Culture »*

VVaglry, Welcome of Tear, The Tapirape Indio tv of Central Bran ft Ward. Them Children: A Study in l.anguage Learning Whitten, Black Frontiersmen: Afro-Hiipanic Culture of Ecuador ft and Colombia*

Williams, Community in a Black Pentecostal Church Wilson, Good Company; 4 Study of Nyakyusa Age• t illages Wolcott. A Kwakiutl Village and School

Wolcott, The Man in the Principal’s Office: .4n Ethnography Yoort, The Gypsies

[Title Page]

NOMADS

OF THE LONG BOW

The Siriono of Bolivia

ALLAN R. HOLMBERG

[Copyright]

For more information about this book, write or call:

Waveland Press, Inc.

P.O. Box 400

Prospect Heights, Illinois 60070 (312) 634–0081

Nomads of the Long Bow was originally published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1950.

Copyright © 1969 by Laura H. Holmberg as executrix of the estate of Allan R. Holmberg. 1985 reissued by Waveland Press, Inc. Second printing. Reprinted by arrangement with Doubleday & Company, Inc.

ISBN 0-88133-161-9

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

*** [About the Author]

Allan Holmbebg’s early death in 1966 deprived anthropology of a leading innovator and distinguished scholar. As a Sterling Fellow in Anthropology at Yale, Dr. Holmberg completed his doctoral thesis on the Siriono Indians in 1946, published here as revised by the author shortly before his death. In 1948 he joined the faculty of Cornell University and began eighteen years of work in applied anthropology, using his knowledge to correct the injustice of poverty, sickness, and ignorance among peasant peoples in developing areas of South America.

Professional recognition came to Dr. Holmberg in such posts as Chairman of the Department of Anthropology at Cornell, Director of the University’s renowned Peru Project, Treasurer of the Society for Applied Anthropology, and membership on the President’s Scientific Advisory Committee, the Latin American Science Board, the Committee on Overseas Studies in the Behavioral Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences, and the Advisory Board of the Cornell Program in Social Psychiatry.

Foreword

This account of the near-starving Siriono Indians, foraging through the tropical swamps and forests of eastern Bolivia, was written by a young anthropologist at the beginning of his career. The book was originally conceived as a technical monograph to be read by a few specialists. Even worse, it was a doctoral dissertation designed to demonstrate the authors professional competence as an ethnographer. Those of us who have read scores of such theses know that few of them are very readable as literature and that fewer still are very exciting.

Yet, soon after Allan Holmberg’s thesis was deposited on the library shelves of Yale University in 1947 it began to excite the keenest professional interest and discussion among anthropologists. Published three years later by the Smithsonian Institution, it attracted a wider circle of excited readers and was soon out of print. Throughout the world, enthusiastic scholars and students of man began to read, study, and argue over his work. In this new edition, published posthumously, Holmberg’s thesis is now made available again not only to the scholar and student but to the general reader who would share with the scientist something of the excitement and adventure of anthropological discovery.

The lowly but instructive Siriono are an Old Stone Age people. They may have degenerated to this level from a more advanced technical condition, a view long rejected by the author, or they may simply be survivors who “from the beginning” retained a variety of man’s earliest culture. The problem is intriguing, but is irrelevant to the value of this book as a Paleolithic ethnography, a systematic description by a professionally trained eyewitness of the way of life of a still-living Old Stone Age people. It was at this Paleolithic level of subsistence, under conditions of a hunting and gathering technology without domesticated crops or livestock, that man developed, and our own and the Siriono’s ancestors became Homo sapiens.

Paleolithic man, however wise or foolish, is inevitably outside of history, for without writing, he has no written record of his own. Nor have Old Stone Age societies successfully survived the depredation of the New Stone Age and civilized men as these extended their uncompromising ways of life over the globe. Thus, few Paleolithic peoples ever enter history, and fewer still remain there—that is, unless a rare Holmberg appears on the scene from some civilization to bring them into the human record. Simply as a description of such a group, Holmberg’s work constitutes an important contribution to the study of man.

It is not easy to make generalizations about Paleolithic peoples. The small sample of simple, Old Stone Age folk surviving into our times—the Eskimo and a few Indian groups in North and South America, pygmies and bushmen of Africa, Oceanic Negritoids, aboriginal Australians—shows a considerable range of behavior differences, as well as some general similarities. Some have been cited as aggressive and generally malevolent in support of the popular Lord of the Flies or Naked Ape thesis that man is by nature bom ornery and vicious. Others have been called The Harmless People and used to support an argument such as Prince Kropotkin’s that within the simple group mutual aid and norms of benevolence are of value for survival and are thus an original aspect of the human condition. The data on the surviving Paleolithic Siriono are important to this debate and to the even older debate on the roles of Nature versus Nurture in shaping human behavior. We may well join prehistorians, ethnographers, and other specialists in welcoming Holmberg’s work, which discovered, described, and thus introduced into history a new and in many respects extraordinary Paleolithic experience.

Theoretical rather than humanitarian interests led Holmberg to seek out this starving group of Indians for his dissertation research. He did not know what he would find, for the Siriono were scarcely mentioned in the existing literature. But he hoped he might discover data with which to test the universality of some of the psychoanalytical assumptions popular in the 1940s. Anthropology, with its wide range of interests, is notorious for its discovery of a number of famous negative cases—single examples of patterned behavior that demonstrate the need to modify or throw out dogmatic notions based on a too narrow, parochial or biased scanning of the human data. The negative case is the exception that proves or tests the rule that certain behavior is universal as claimed and thus probably inevitable in human experience.

During the past half century the psychoanalytic portrait of human personality has come to be widely and almost unconsciously accepted by Western and Western-educated publics as a good likeness. According to this view, the sexual drive is universally the most dominant in the conscious and unconscious lives of human beings. And sexual libido in myriad manifestation is seen as the basic core of human action everywhere—except, as we discover here, among the hungry Siriono! If the hunger drive can displace sex in much of the normal waking and dreaming life of these food-starved Indians, then the role of this and of other appetites in the frustrations of our lives needs to be reconsidered, and the working out of such frustrations in overt and covert behavior requires further investigation. The lesson is that our first attempt must always be to understand the complicated life of each individual and of each group in its own specific terms while obtaining what help we can from “universals” drawn from our still too limited samples of humankind.

The trends and traditions of local cultures must be understood and utilized if the fives of individuals, and the group as a whole, are to be effectively changed by conscious influence exerted from outside, as is the aim of our modem programs of technical aid. It is clear that the specific traditional Siriono attitudes toward food could have been made to play a crucial role when mission or government agencies sought to change the nomadic Indians into sedentary gardeners and livestock producers, offering them sure means to secure a stable and adequate supply of food. Applied anthropology, the application of anthropological insights to the solution of problems of planned cultural change, is not a topic dealt with in this book. Yet the author, before he left the Siriono, and using his detailed knowledge of their specific way of fife, had already begun to “experiment with culture,” to introduce to them new forms of behavior carefully determined with regard to their already established patterns of feeling, thinking, and action.

Applied anthropology continued to be one of Holmberg’s primary professional interests, and during his long association with Cornell University, from 1948 until his early death in 1966 at the age of fifty-six, he won a world-wide reputation as a leading practitioner of the art. His Cornell program of research and development centered on Peru, where, among other projects, he successfully undertook to transfer initiative and authority in the Indian village of Vicos high in the Andes to the peasant villagers themselves, divesting them in a few years of their centuries-old peonage, and raising their level of living manyfold. He found that indeed the behavior of these peasants could be changed, but toward what ends, and by what sure means—ends and means which would not bring damaging reaction from within or counteraction from without? In the face of these large questions, Holmberg carefully made the necessary ethical and scientific calculations with knowledge, wisdom, humanity, and moral courage. The Siriono, too, could have used such anthropology to advantage.

Finally, this book suggests that the tasks of the field anthropologist may require some physical as well as moral bravery, some ingenuity as well as wisdom, some inner stamina as well as interest in humanity. As we read the modest introduction to this study, we appreciate the difficulties and actual dangers Holmberg overcame in establishing and maintaining contact with the elusive nomads of the long bow as they moved about their most inhospitable territory, a region so isolated that it was months before the author learned of his country’s entry into the Second World War. Holmberg succeeded admirably in his scientific work among the Siriono; but he also succeeded in maintaining health, energy, and spirits and in surmounting all the varied housekeeping troubles which confront the scholar working alone in a distant comer of the world. Had he failed in these essential tasks, there would have been no skilled observation, no careful records, no thoughtful analysis, and we would not have this report today.

With the young Allan Holmberg as companion and highly competent guide, the reader now embarks on this adventure in modern anthropology. May he not only discover the Siriono but also something of the aims and methods and character of the science of man and of one of its best practitioners.

Surin, Thailand Lauriston Sharp

June 1968

Introduction{1}

The following study was carried out under the auspices of the Social Science Research Council of which I was a pre-doctoral fellow in 1940–41. It had its origin in 1939, when I was associated with the Cross-Cultural Survey (now the Human Relations Area Files, Inc.) at the Institute of Human Relations, Yale University. While studying there, I was privileged to get considerable exposure to the cross-disciplinary approach to the problems of culture and behavior which was being emphasized at the Institute, especially by Doctors Murdock, Hull, Dollard, Miller, Ford, and Whiting.

As I continued my anthropological studies, it became more and more apparent to me, as to others, that a science of culture and behavior was most apt to arise from the application of techniques, methods, and approaches of several scientific disciplines concerned with human behavior—particularly social anthropology, sociology, psychology, and psychoanalysis—to specific problems. Consequently, in casting around for a subject on which to carry out field work, I began to search for one that would be especially amenable to cross-disciplinary treatment.

While studying at the Institute of Human Relations, I became keenly aware of the significant role played by such basic drives as hunger, thirst, pain, and sex in forming, instilling, and changing habits. Because of the difficulty of studying human behavior under laboratory conditions, our knowledge about the processes of learning has been derived largely from experimental studies of animals. However, the procedure, successfully employed in psychological experimentation, of depriving animals of food suggested that it might be possible to gain further insight into the relationship between the principles of learning and cultural forms and processes by studying a group of perennially hungry human beings. It was logical to assume that where the conditions of a sparse and insecure food supply exist in human society the frustrations and anxieties centering around the drive of hunger should have significant repercussions on behavior and on cultural forms themselves. Hence, I took as my general problem the investigation of the relation between the economic aspect and other aspects of culture in a society functioning under conditions of a sparse and insecure food supply. More specifically, the problem resolved itself into determining, if possible, the effect of intermittent frustration of the hunger drive on such cultural forms as diet, food taboos, eating habits, dreams, antagonisms, magic, religion, and sex relations, and upon such cultural processes as integration, mobility, socialization, education, and change.

In our own society there are many individuals who suffer from lack of food, but one rarely finds hunger as a group phenomenon. For this reason a primitive society, the Siriono of eastern Bolivia, was chosen for study. The Siriono were selected for several reasons. In the first place, they were reported to be seminomadic and to suffer from lack of food. In the second place, they were known to be a functioning society. In the third place, the conditions for study among them seemed favorable, since it was possible to make contact with the primitive bands roaming in the forest through an Indian school which had been established by the Bolivian government in 1937 for those Siriono who had come out of the forest and abandoned aboriginal life.

I left for Bolivia on September 28, 1940, and arrived in the field on November 28, 1940. Between November 28, 1940, and May 17, 1941, I worked with informants of various bands of Siriono who had been gathered together in a Bolivian Government Indian School at Casarabe, a kind of mixed village of Indians and Bolivians, situated about forty miles east of Trinidad, capital of the Province of the Beni. (See map.) At the time of my stay this so-called school had a population of about 325 Indians.

Following my residence in Casarabe, where I became grounded in the Indian language and those aspects of the aboriginal culture that still persisted there, I left in May 1941 to join a band of about 60 Siriono who were living under somewhat more natural conditions near the Rio Blanco on a cacao plantation called Chiquiguani, which was at that time a kind of branch of the Casarabe school. Upon arriving at Chiquiguani, however, I found that as a result of altercations with the Bolivians, the Indians had dispersed into the forest, so that I encountered no people with whom to work. Consequently, I returned to a ranch near the village of El Carmen. There I was fortunate in meeting an American cattle rancher, Frederick Park Richards, since deceased, who had resided in the area for many years and who had a number of Siriono living on his farm and cattle ranch. Through him I was presented to a Bolivian, Don Luis Silva Sánchez, a first-rate bushman, and explorer for the aforementioned school, who offered to be my companion, and who stayed with me during most of the time that I lived and wandered with the Siriono. In company with Silva I set out in search of the Indians who had dispersed into the forest. After about ten days they were located and agreed to settle on the banks of the Rio Blanco, about two or three days’ journey up the river by canoe from the village of El Carmen, at a place which we founded and named Tibaera, the Indian word for asayi palm, the site being so designated because of the abundance of this tree found there. I spent from July 15 to August 28, 1941, at Tibaera continuing my general cultural and linguistic studies, but under what I regarded as unsatisfactory conditions, since I had previously laid my plans and devoted my energies to acquiring techniques for observing a group of Siriono who had had little or no previous contact. Consequently, I suggested to Silva that we go in search of other Indians. Finally, on August 28, 1941, I set out from Tibaera, in company with Silva and parts of two extended families of Indians (21 people in all), traveling east and south through the raw bush in the general direction of the Franciscan missions of Guarayos, where we were told by the Indians that we might locate another band which had had little or no previous contact. After eight days of rough travel, much of which involved passing through swamps and through an area which had long been abandoned by the Siriono, we joyously arrived at a section of high ground containing relatively recent remains of a Siriono campsite. My Indian companions told me that this site had been occupied by a small number of Indians who had come there in quest of calabashes about three “moons” earlier.

Inspired by the hope of soon locating a primitive band, we silenced our guns, and lived by hunting with the bow and arrow so as not to frighten any Indians that might be within earshot of a gun. We followed the rude trails which had been made by the Indians about three months earlier, and after passing many abandoned huts, each one newer than the last, we finally arrived at midday on the eleventh day of march just outside a camp. On the advice of our Indian companions, Silva and I removed most of our clothes, so as not to be too conspicuous in the otherwise naked party—I at least had quite a tan—and leaving behind our guns and all supplies except a couple of baskets of roast peccary meat, which we were saving as a peace gesture, we sandwiched ourselves in between our Indian guides and made a hasty entrance into the communal hut. The occupants, who were enjoying a midday siesta, were so taken by surprise that we were able to start talking to them in their own language before they could grasp their weapons or flee. Moreover, as their interest almost immediately settled on the baskets of peccary meat, we felt secure within a few‘moments’ time and sent back for the rest of our supplies.

Once having established contact with such a group, I had intended to settle down or wander with them for several months, or until I could complete my studies. I was forced, however, to abandon this plan when, after being with them for a day or two, I came down with an infection in my eyes of such gravity that I was almost blinded. Fearing that this infection would spread to a point that I might lose my sight, and since I carried no medicines with which to heal it, I decided to set out for the Franciscan missions of the Guarayos, about eight days’ distance on foot, the nearest point at which aid could be obtained. Before leaving, however, I consulted with the chief of this new group (his name was Acíba-eóko, or Long-arm) and told him that I planned to return and study the manner of life of his people. In the meantime, the Indians in our original party, knowing of my plan, had already convinced the chief and other members of his band to return with them to the Rio Blanco and settle down for a while at Tibaera, a plan which suited me perfectly. Consequently, in the company of 4 Indians of this new band and Silva, I traveled on foot to Yaguarú, Guarayos. After about two weeks of fine treatment at the hands of the civilian administrator, Don Francisco Materna, and the equally hospitable Franciscan fathers and nuns, I was able to rejoin the band, and we slowly returned to Tibaera, arriving there on October 11,1941.

Besides what studies I was able to make of this band while roaming with them during part of September and October 1941, I continued to live with them at Tibaera, except for occasional periods of ten days’ or two weeks’ absence for purposes of curing myself of one tropical malady or another or of refreshing my mental state, until March 1942, when my studies were terminated by news that the United States had become involved in war three months previously.

As can be readily inferred from the above account of my contacts with the Siriono, they were studied under three different conditions: first, for about four months, while they were living at Casarabe under conditions of acculturation and forced labor; second, for about two months, while they were wandering under aboriginal conditions in the forest; finally, for about six months, while they were living at Tibaera, where aboriginal conditions had not appreciably changed except for the introduction of more agriculture and some iron tools. During the course of my work, I made a complete ethnological survey of the culture, although my attention was focused primarily on the problem of the sparse and insecure food supply and its relation to the culture. As my knowledge of the language and culture increased, I was constantly formulating, testing, and reformulating hypotheses with respect to this problem.

Since Siriono society is a functioning one, three fundamental methods of gathering field data were employed: (1) the use of informants, (2) the recording of observations, and (3) the conducting of experiments. The first two methods were followed throughout the course of the work. Experiments, such as the introduction of food plants and animals, were performed during the latter part of the study, although the extensive use of this method was limited by the termination of the research.

The application of the above field methods was facilitated by the use of various techniques, of which the following were the principal ones: (1) the use of the language of the people studied and (2) the participation of the ethnographer in the cultural life of the tribe.

When possible, data were recorded on the spot in an ethnographic journal, which was supplemented by a record of personal experiences while in the field. As the group was small, everyone was used as an informant, and since most of the activities of the Siriono center in but one hut, data on the behavior patterns of almost everyone could be recorded. No paid informants were used, although gifts such as bush knives and beads were given. No Siriono was a willing informant; little information was volunteered, and some was consciously withheld. Had it not been for the fact that I possessed a shotgun and medicines, life with the Indians would have been impossible. By contributing to the food supply and curing the sick, I became enough of an asset to them to be tolerated for the period of my residence.

At the time of leaving the field (I had not finished my studies) I did not feel satisfied that I had gained a profound insight into Siriono culture. True, I had studied the language to the extent that I could carry on a fairly lively conversation with the Indians, but the time spent in satisfying my own basic needs—acquiring enough food to eat, avoiding the omnipresent insect pests, trying to keep a fresh shift of clothes, reducing those mental anxieties that accompany solitude in a hostile world, and obtaining sufficient rest in a fatiguing climate where one is active most of the day—often physically prevented me from keeping as full a record of native life as I might have kept had I been observing more sedentary informants under less trying conditions. However, if I have contributed something to an understanding of these elusive but rapidly disappearing Indians, I shall feel more than satisfied.

This study would have been impossible without the help of many friends and various institutions. I am deeply indebted to the Social Science Research Council for originally providing the funds to carry out the field work; to Yale University (through the efforts of Dr. Cornelius Osgood) for granting me a Sterling Fellowship to write up the field data; and to the Smithsonian Institution for publication of the manuscript.

To my teachers at Yale University I owe a profound debt of gratitude, especially to Dr. G. P. Murdock, who has been a friendly adviser since the beginning of the study. Dr. Murdock spent many hours patiently reading, criticizing, and editing much of the original manuscript. While living with the Siriono, I also had the benefit of his counsel, together with that of the late Dr. Bronislaw Malinowski, Dr. Clark Hull, and Dr. John Dollard, all of whom formed an advisory committee at Yale. These gentlemen were largely responsible for developing my interest in certain problems of this research, and all of them sent me many stimulating letters of advice and criticism while I was in the field. None of them is responsible for any of its defects.

I wish to express my deepest appreciation to Dr. Alfred Métraux. It was he who was largely responsible for crystallizing my interest in the South American Indian and for my selection of the Siriono among whom to work. Dr. Métraux took a keen interest in this study from its inception and gave me constant encouragement while I was in the field. An invaluable service was also rendered by Dr. Wendell C. Bennett, who acted in an advisory capacity when I started to write up my field notes, and by Dr. Clellan S. Ford and Dr. John W. M. Whiting, who made many helpful suggestions and criticisms while I was preparing the manuscript.

While I was in Bolivia, many people helped me in the pursuit of my studies. I wish to express my thanks especially to Dr. Gustav Otero of La Paz, then Minister of Education, for providing me with a letter of introduction to the Director of the Núcleo Indigenal de Casarabe; to Don Carlos Loayza Beltrán, then Director of the Núcleo, and Horacio Salas, then Secretary of the Núcleo, for several months of friendly hospitality; to Senator Napoleon Solares A. of La Paz and Don Adolfo Leigue of Trinidad for comfortably sheltering me in the Casa Suárez in Trinidad, Beni.

My life with the Indians at Tibaera was made possible through the valiant co-operation of Don Luis Silva Sánchez of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Nothing I can say will express the gratitude I feel for this fearless Cruzeño who accompanied me for more than six months in the field under the most trying of conditions. Had it not been for Silva, in fact, my life with the Siriono under aboriginal conditions would have been unbearable.

I am deeply grateful to the late Frederick Park Richards of El Carmen for his bounteous hospitality and for generously providing me with the food and the mobility without which it would have been impossible to carry out my studies. I also wish to express my thanks to Don René Rousseau of Baures and Dr. and Mrs. Lothar Hepner, then of Magdalena, for many days of friendly hospitality and cordial companionship.

Finally, I should like to express my appreciation to the Siriono, who, for the first time in their history, tolerated a naive but inquisitive anthropologist on his first extended stay in the field.

Contents

Foreword to The American Museum

Science Books edition xi

Introduction to the original edition xvii

I Setting and people 1

-

II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. IX. X.

History 10Technology 17Exploitative activities 47Food and drink 71Routine activities of life 98Folk beliefs and science 116Social and political organization 124Sex and the life cycle 161Religion and magic 238Some problems and conclusions 244Appendix 263

Index 280

Illustrations

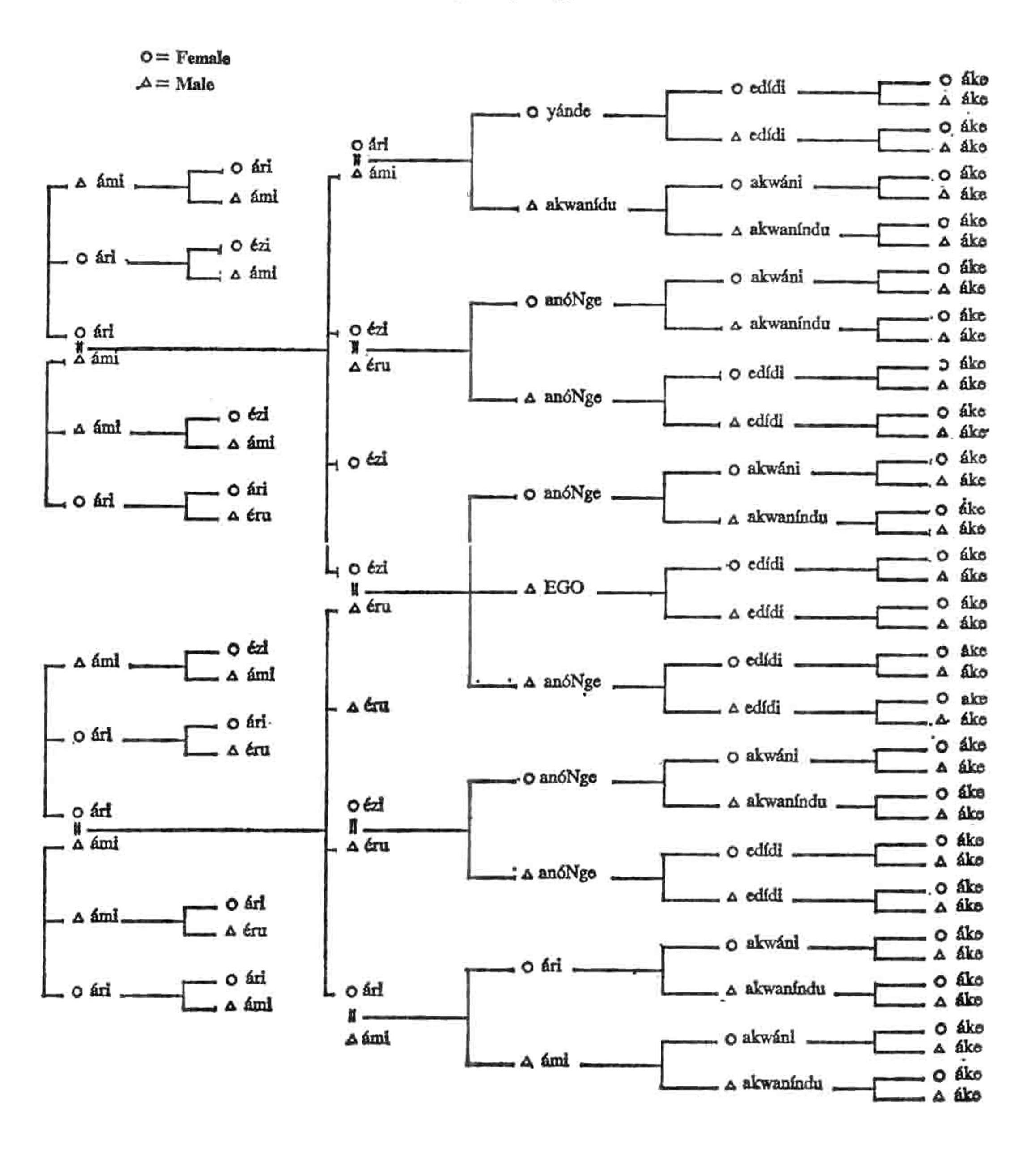

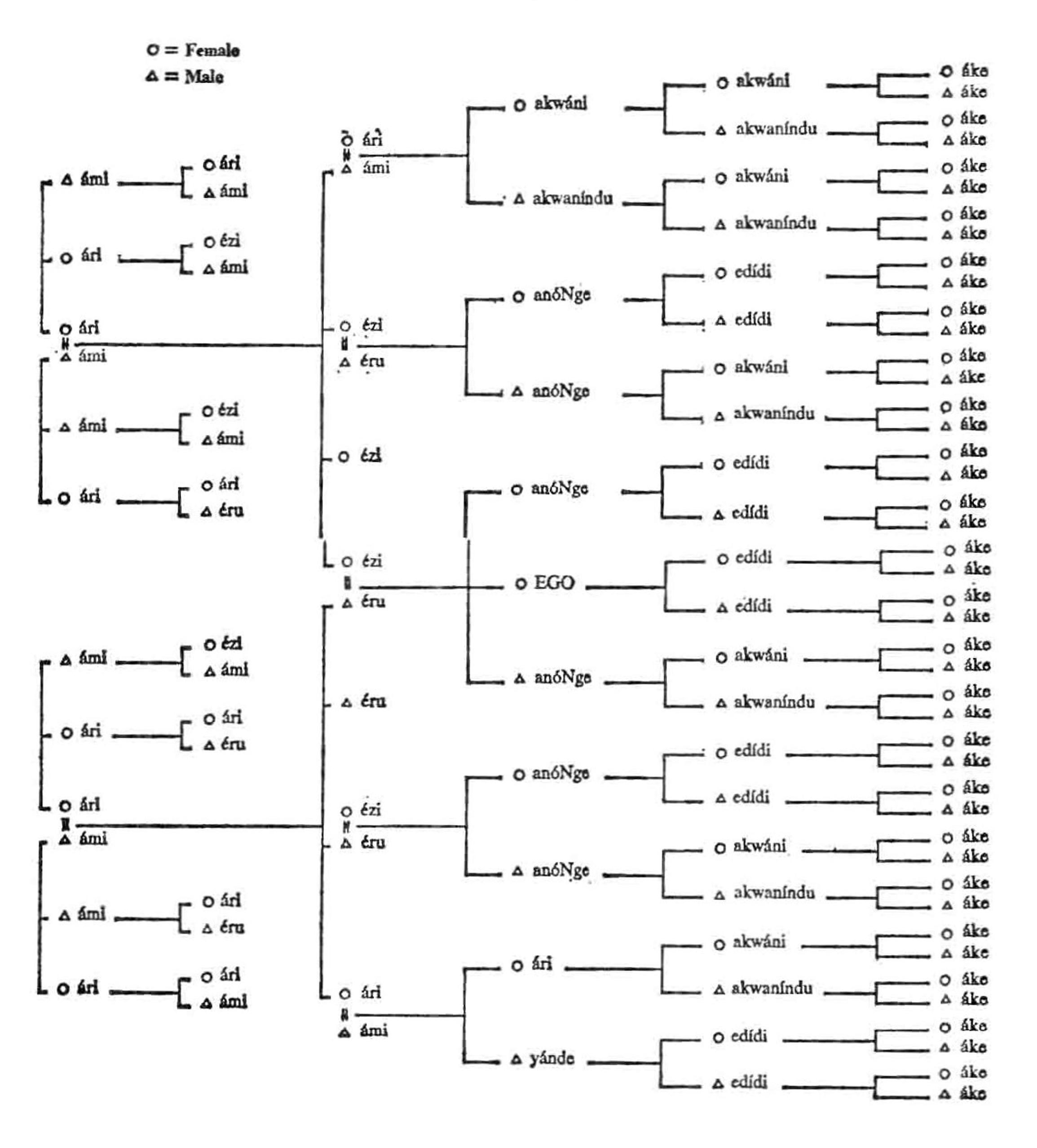

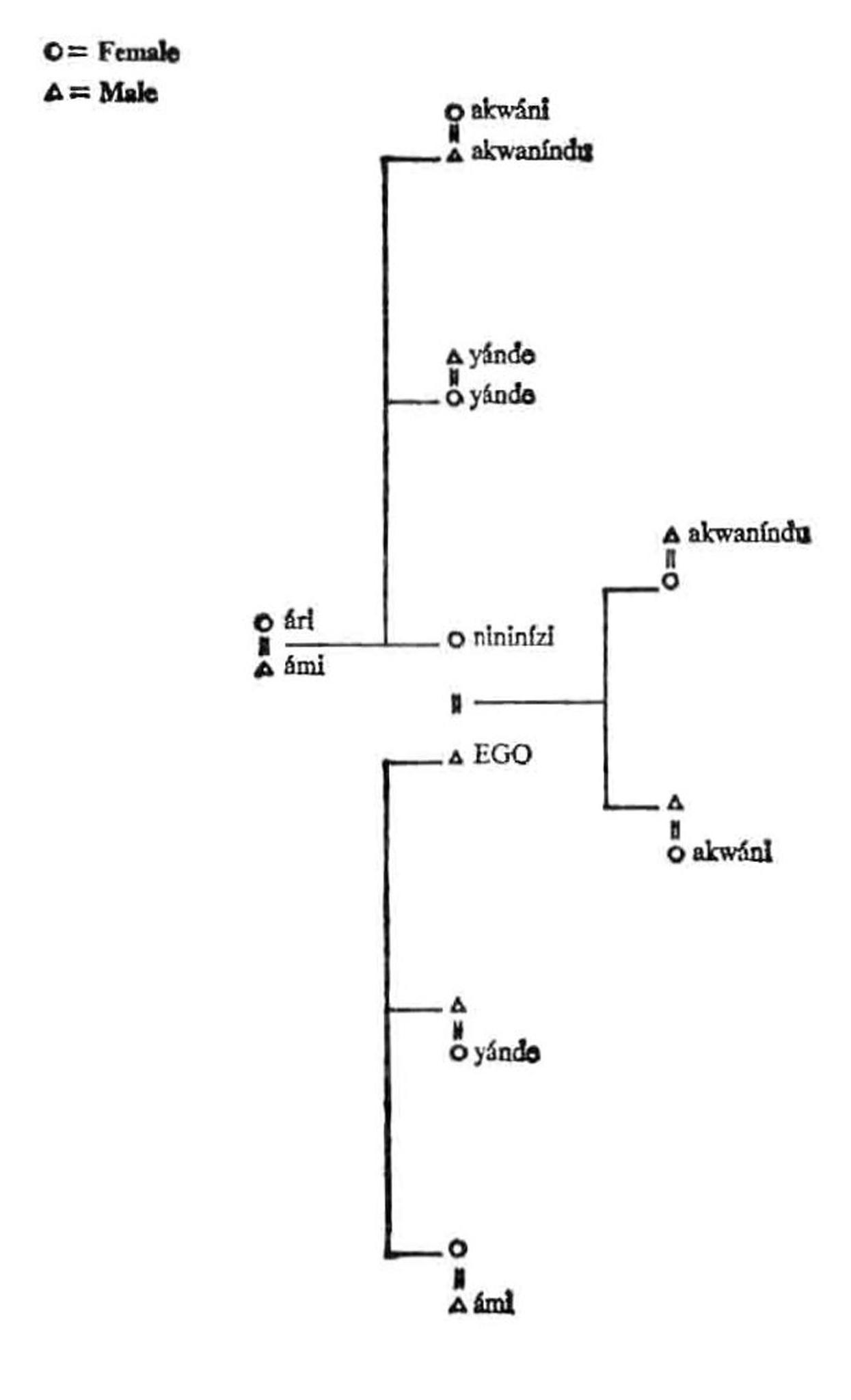

Charts

-

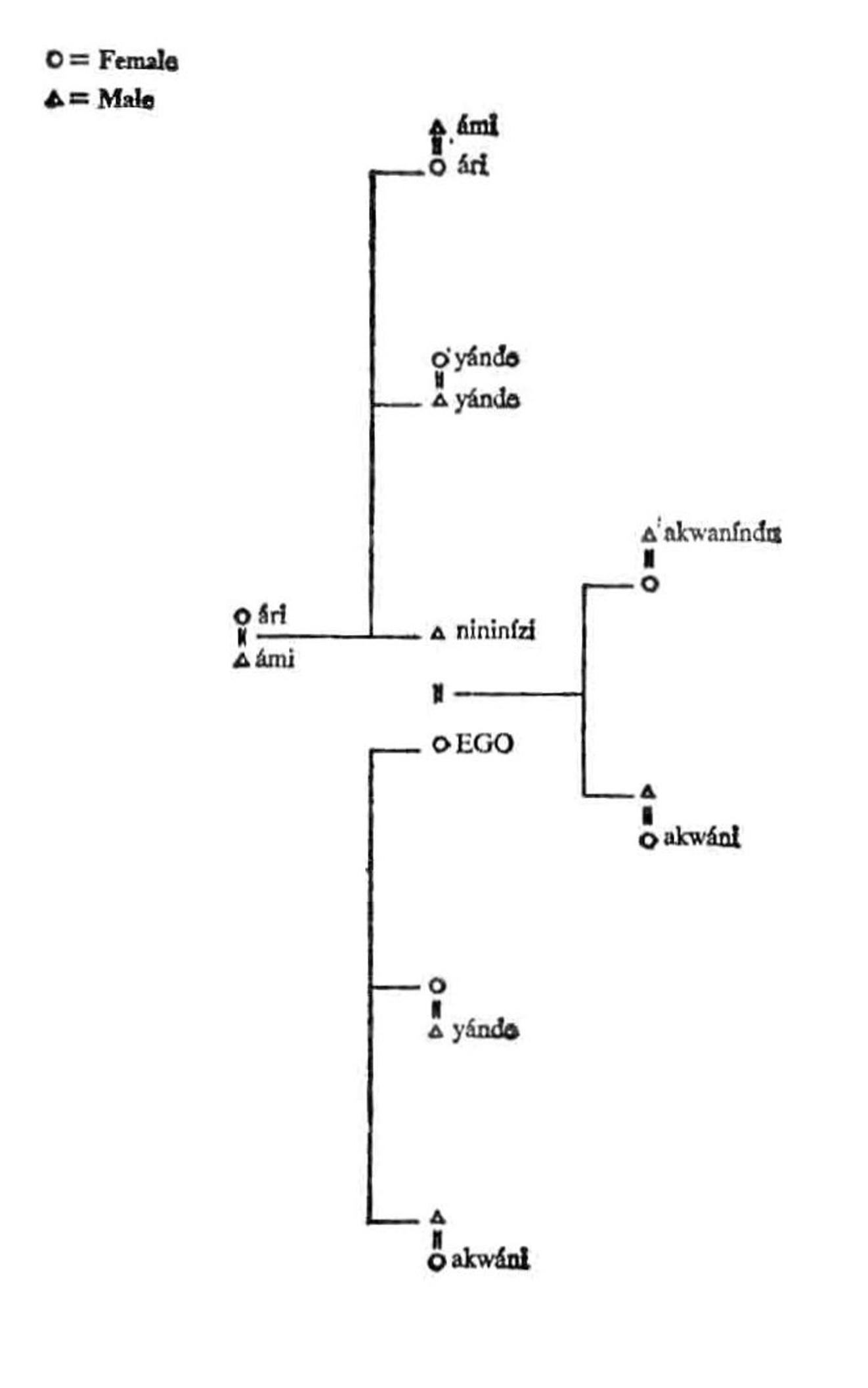

Lineal kinship chart Siriono (male speaking) 2. Lineal kinship chart Siriono (female speaking) 3. Affinal kinship chart Siriono (male speaking) 4. Affinal kinship chart Siriono (female speaking)

Photographs

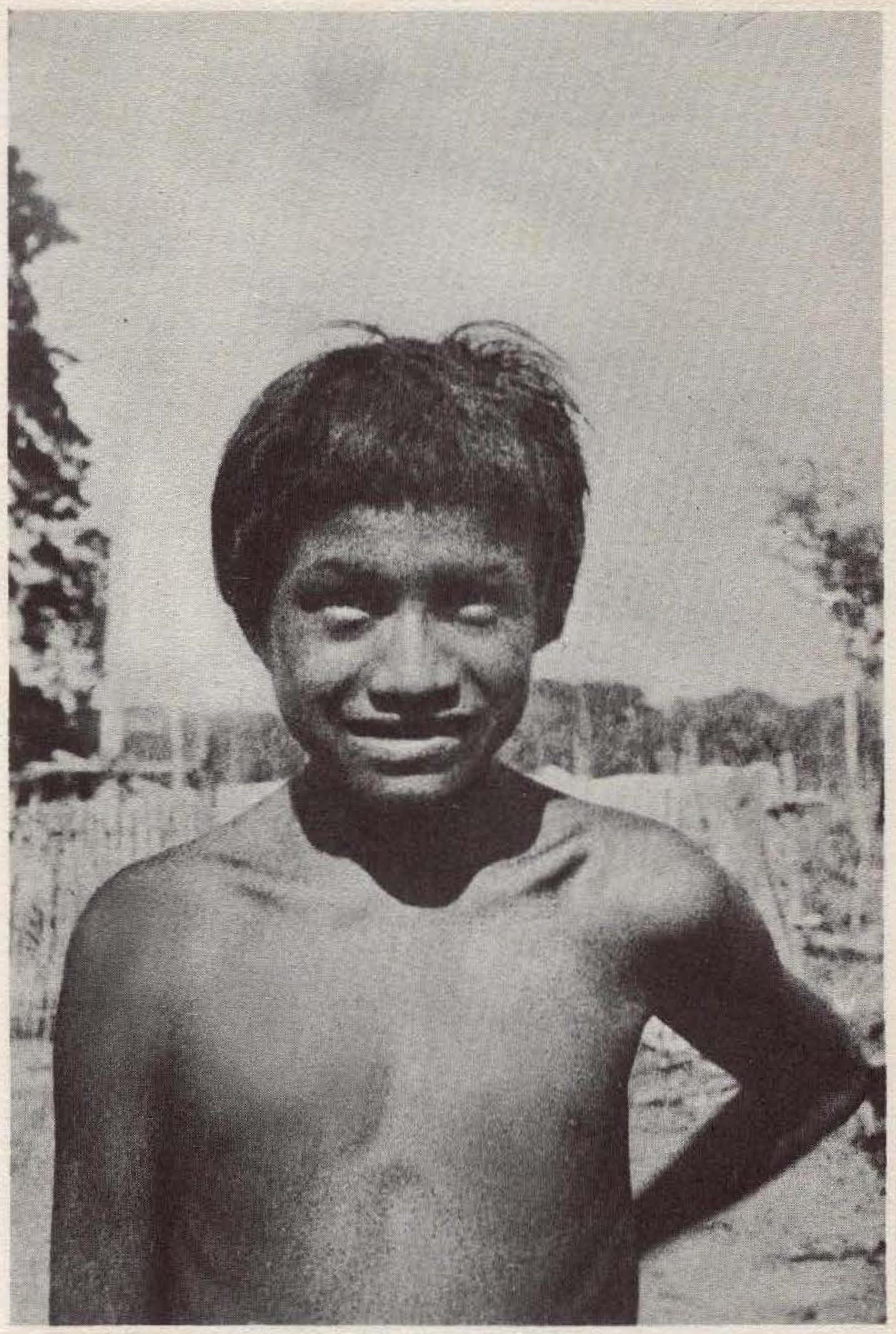

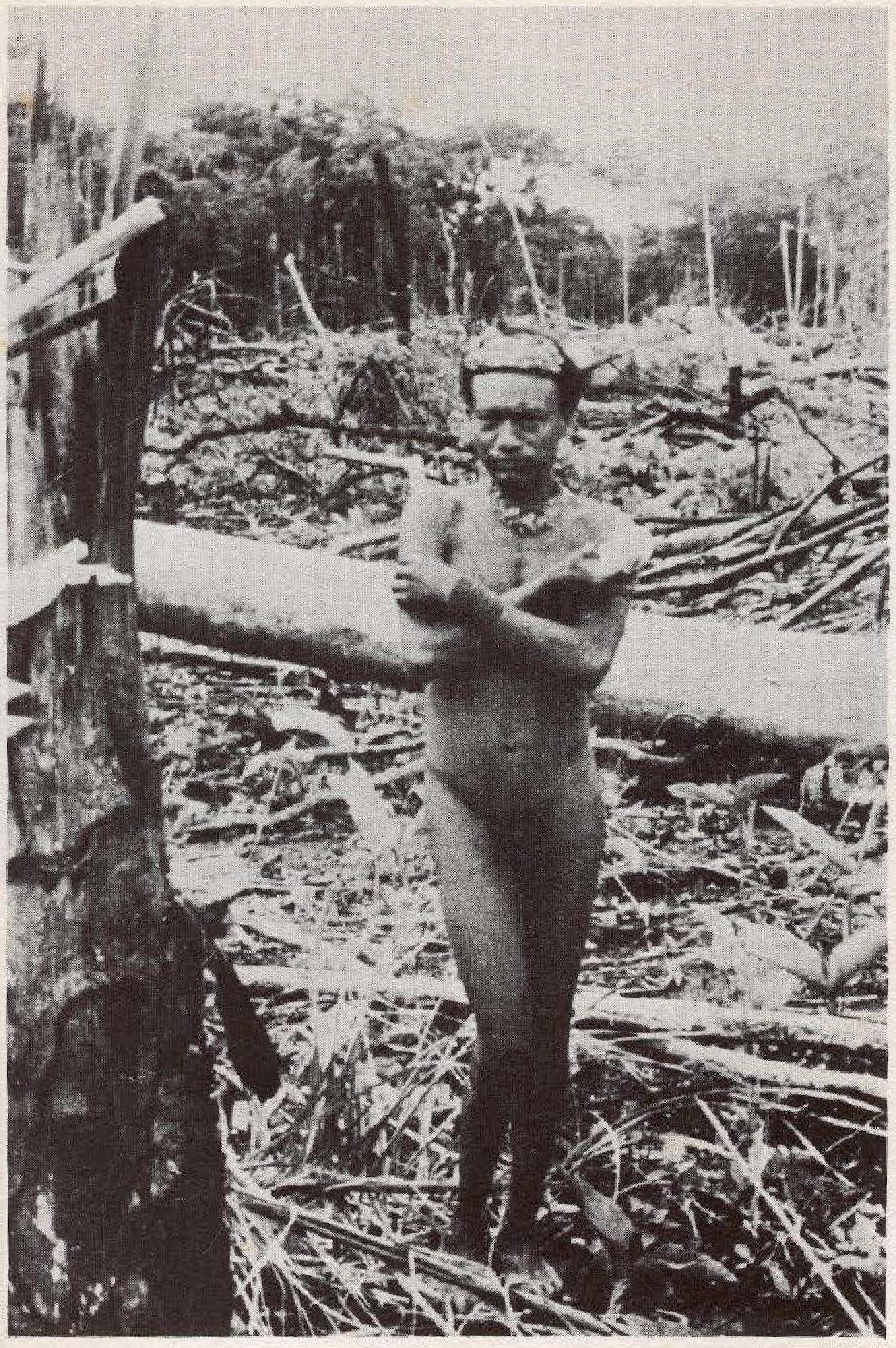

| Plate 1 | Erúba-erási (Sick-faced), a Siriono boy about 14 years old (Tibaera). |

| Plate 2 | A mother demonstrating how she carries her child in the baby sling. |

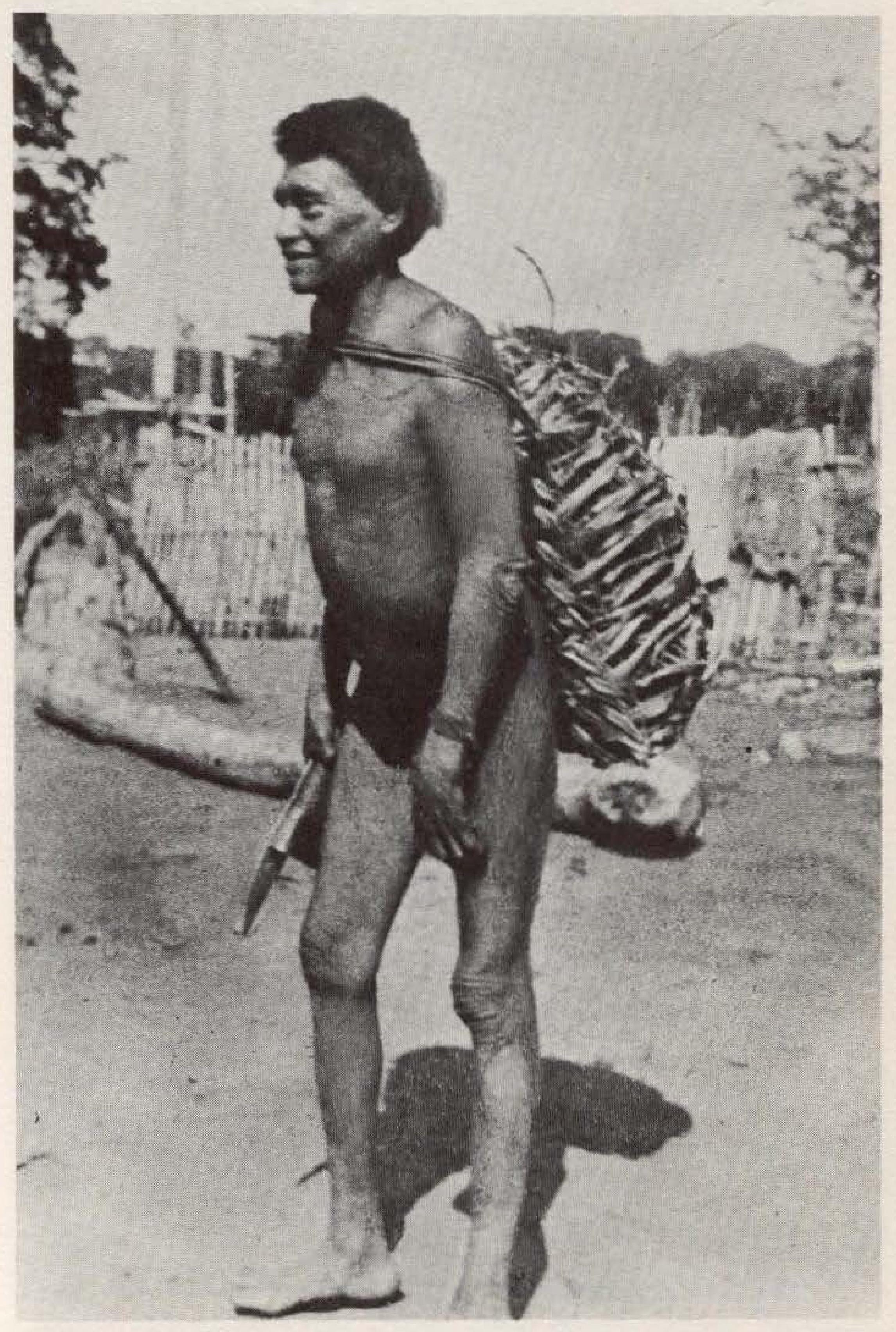

| Plate 3 | Enia demonstrating the method of carrying baskets by men (Tibaera). |

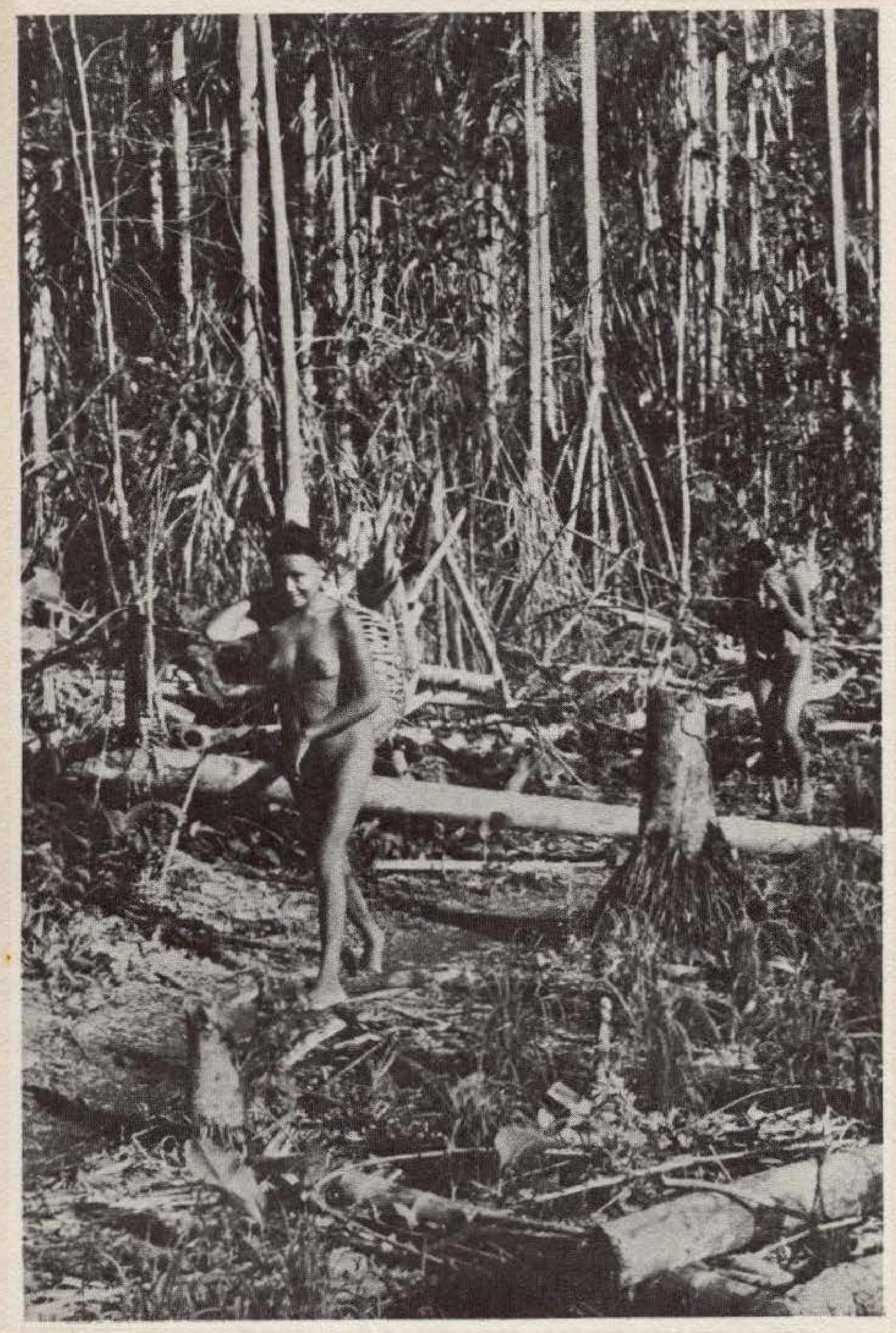

| Plate 4 | Bringing in firewood from forest in carrying baskets (Tibaera). |

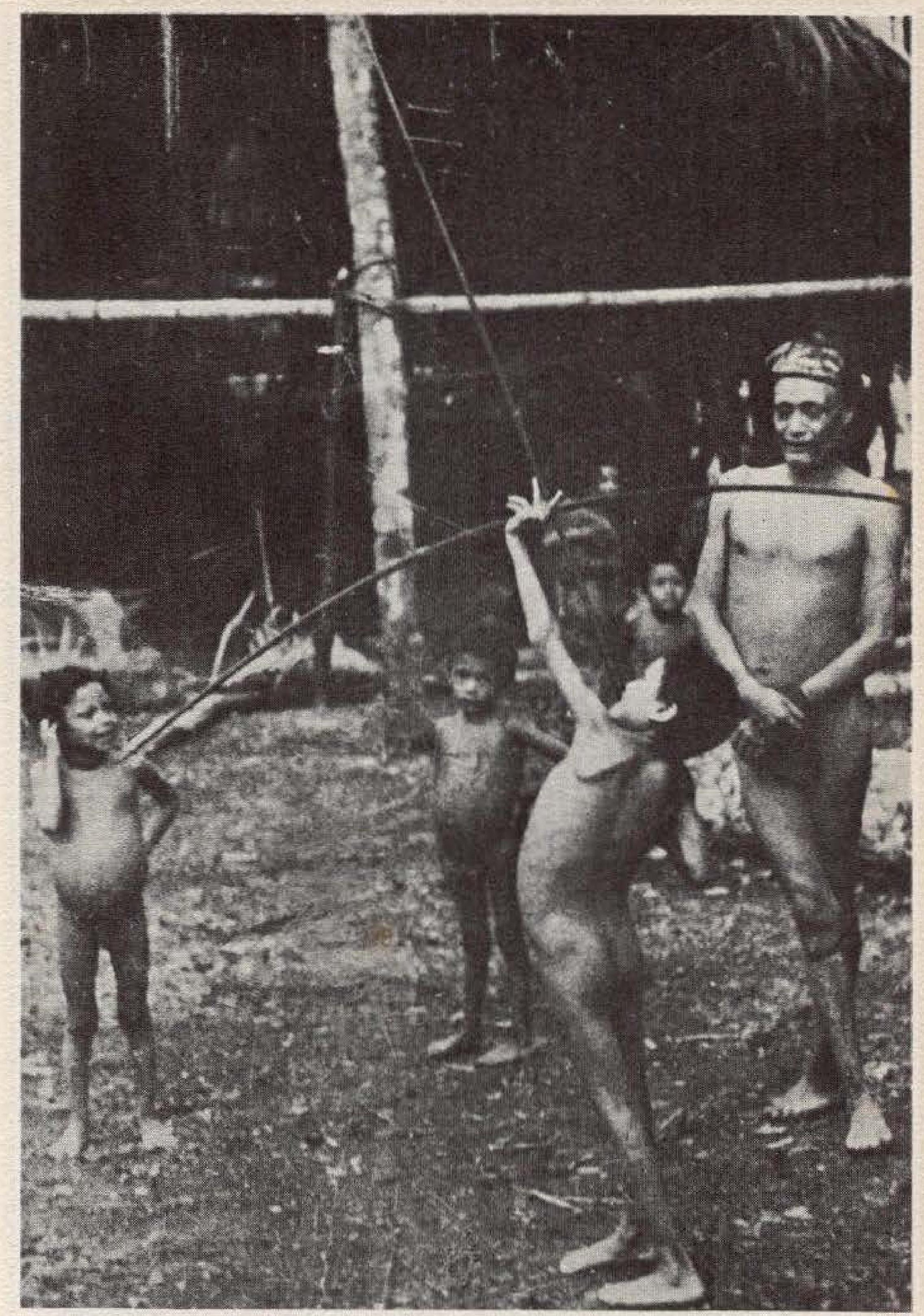

| Plate 5 | Yikinándu watching one of his sons draw the bow (Tibaera). |

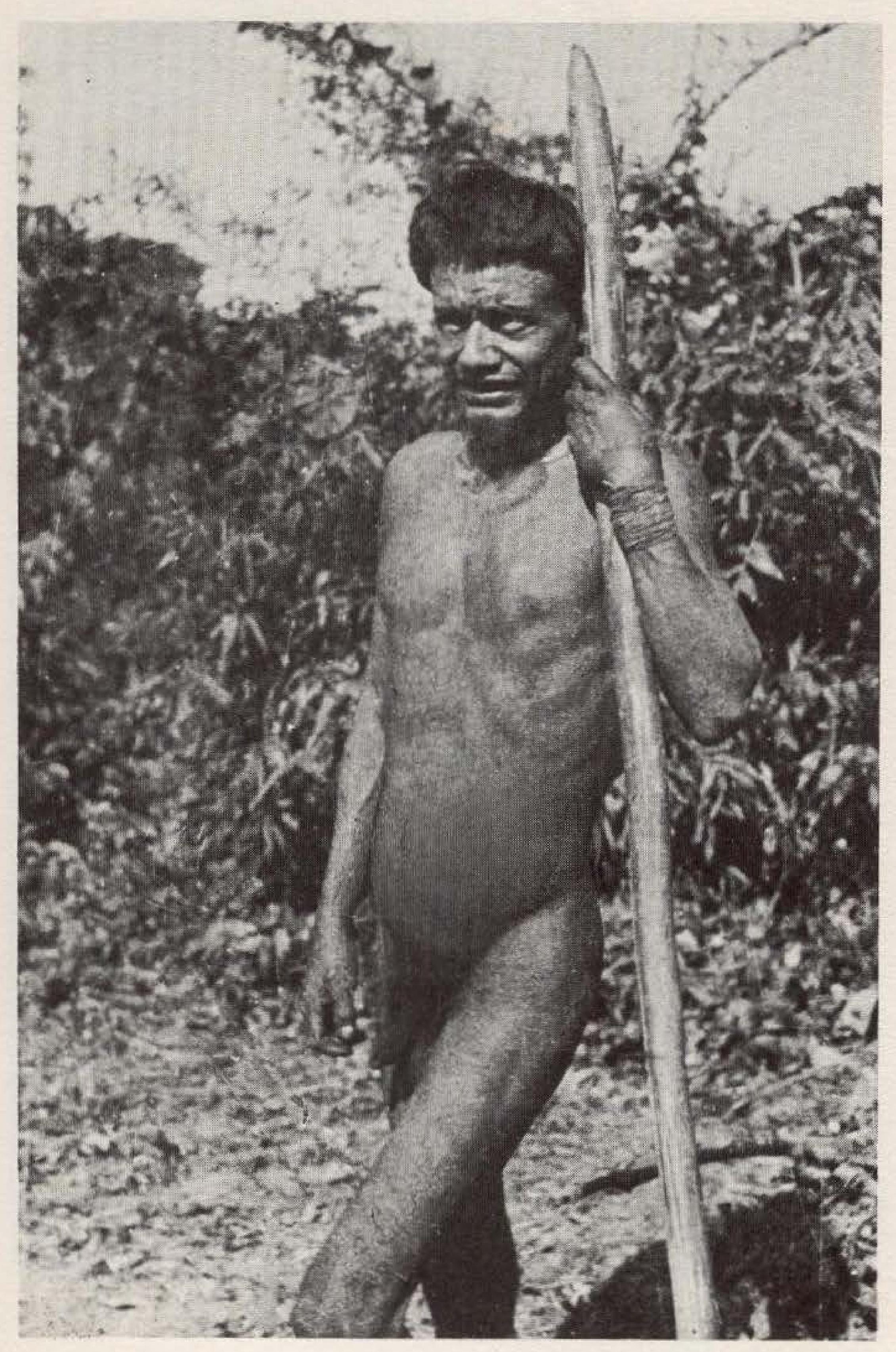

| Plate 6 | A hunter leaning on a pole (Tibaera). |

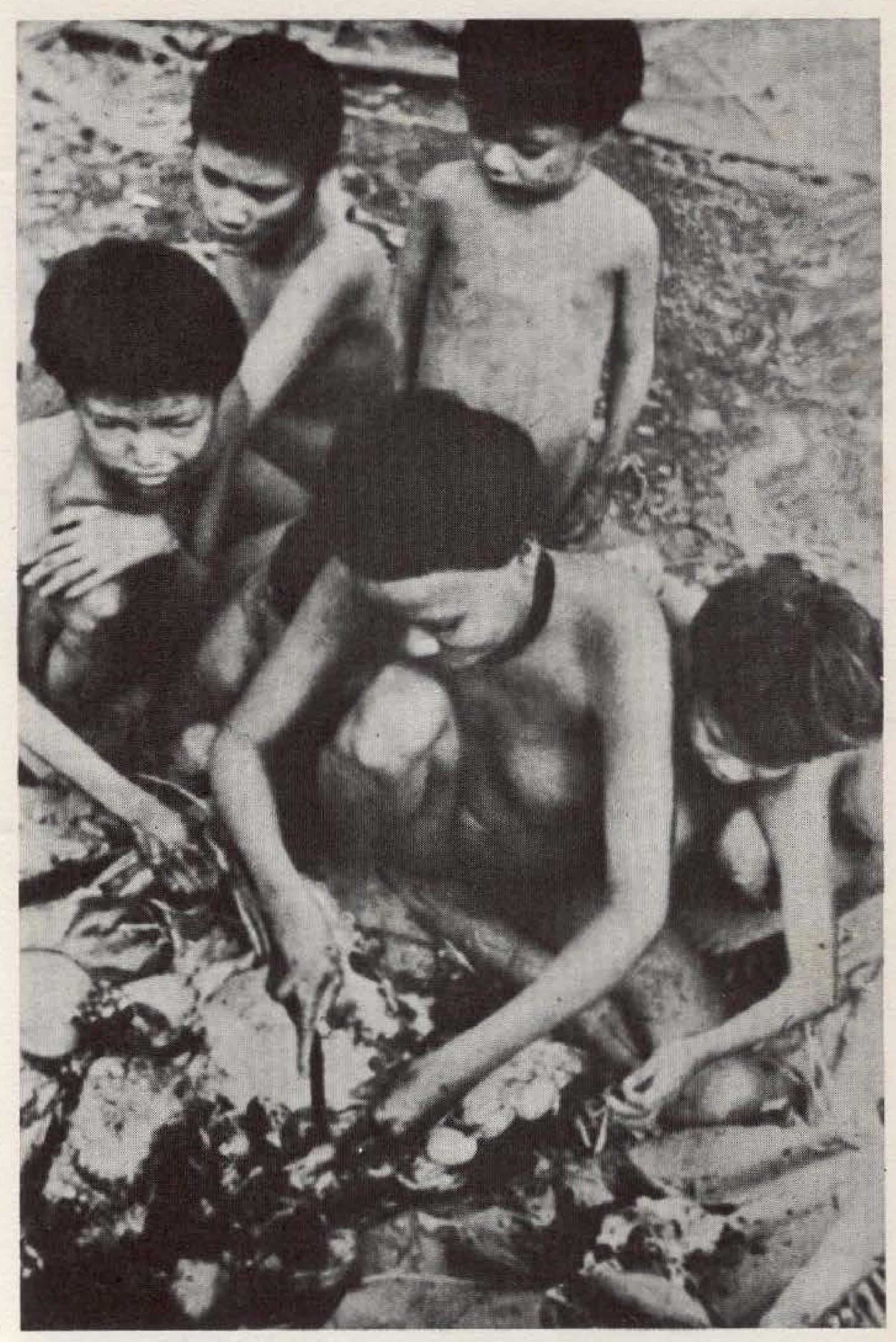

| Plate 7 | Etakui cutting up a tortoise (Tibaera). |

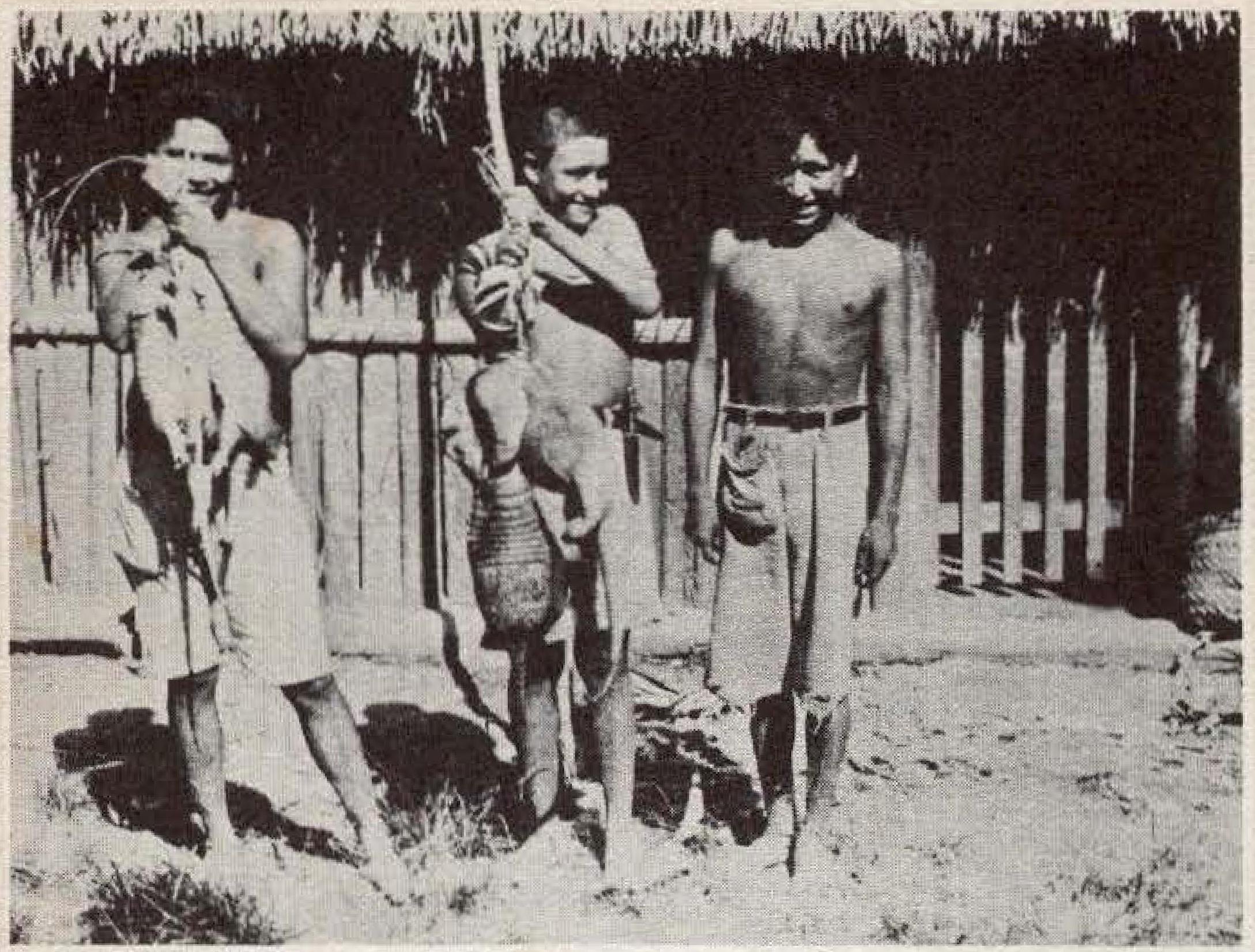

| Plate 8a | Siriono boys at Casarabe with catch of armadillos and anteaters. |

| Plate 8b | Monkey meat roasting in the jungle (Tibaera). |

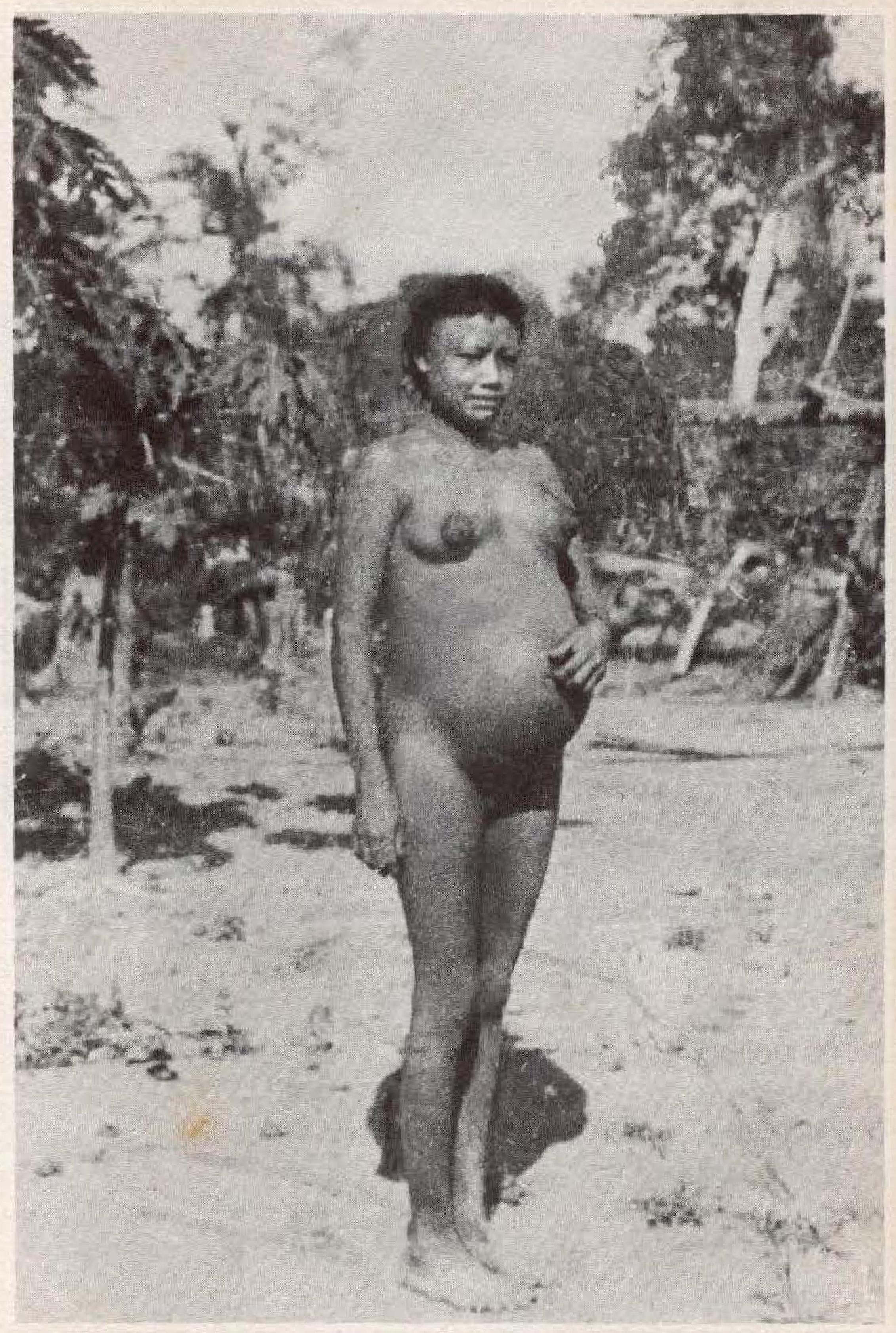

| Plate 9 | Pregnant woman, Eakwantúi; later she gave birth to twins (Tibaera). |

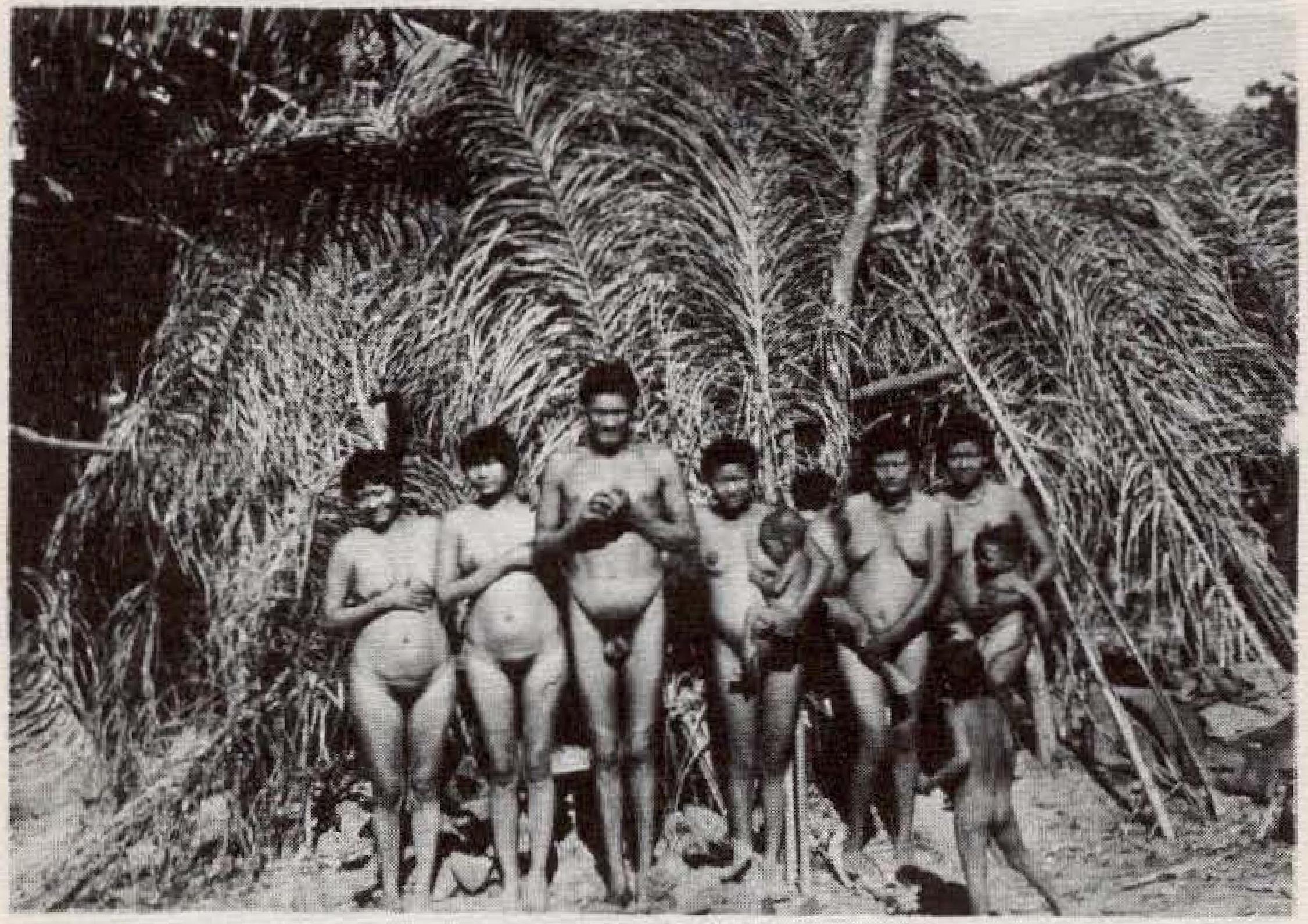

| Plate 10 | Siriono chief and his five wives outside of primitive hut at Casarabe. |

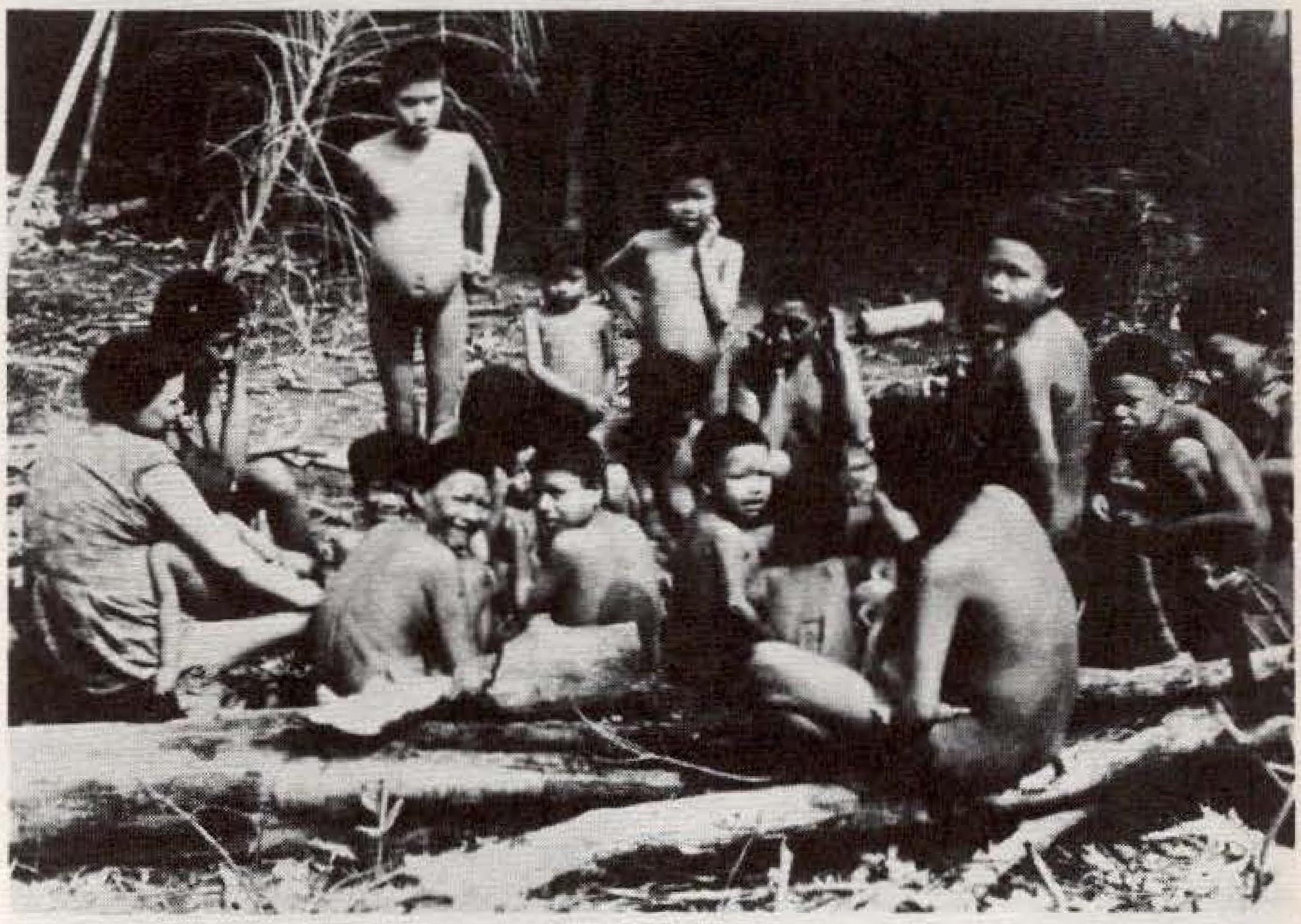

| Plate 11 | A group of Siriono women and children waiting for food. |

| Plate 12 | Father of newborn child, decorated with animal-teeth necklaces and feathers. |

Chapter I: Setting and People

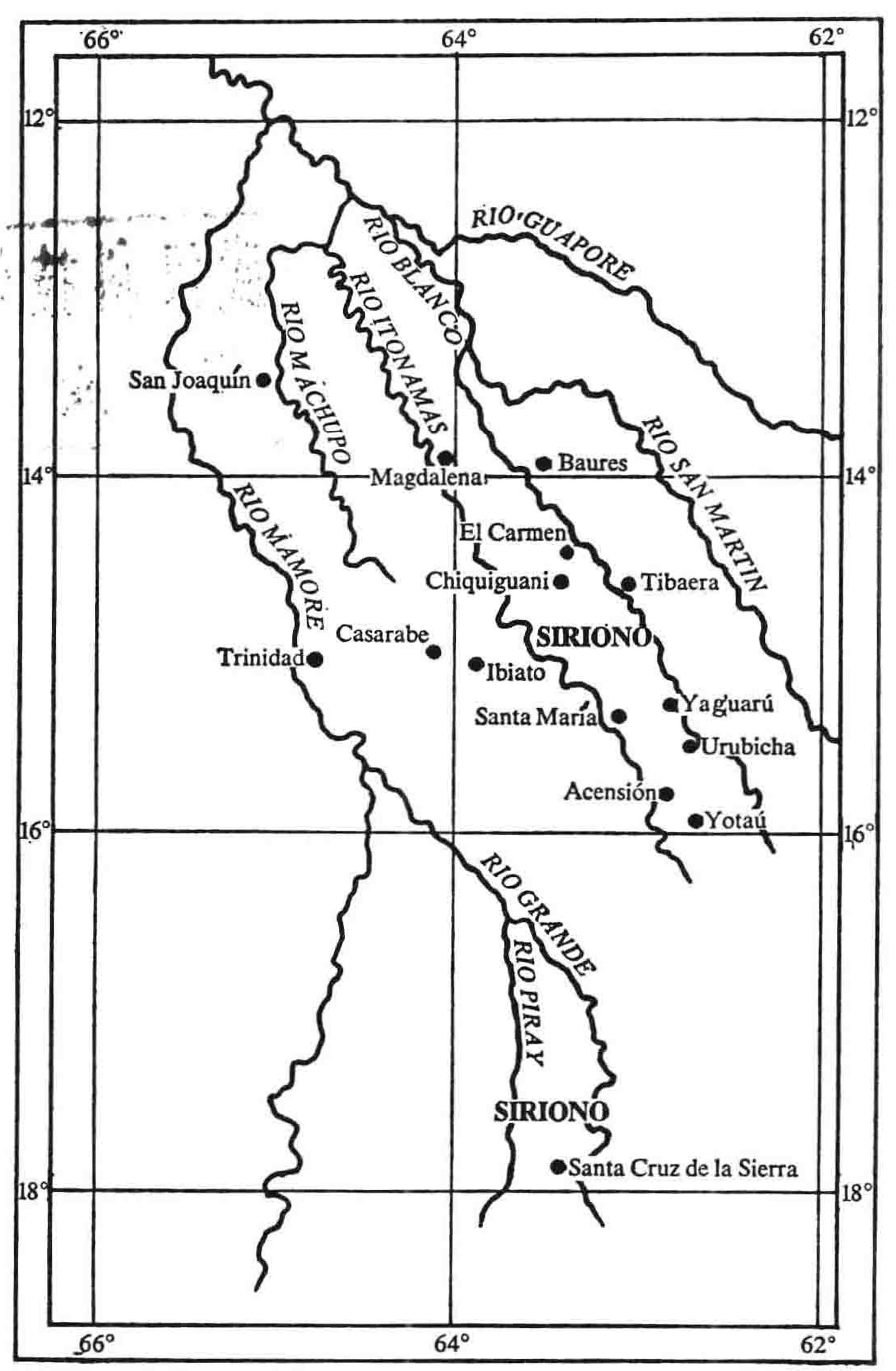

The Siriono are a group of semi-nomadic aborigines inhabiting an extensive tropical forest area, of about 200 miles square, between latitudes 13o and 17o S. and longitudes 63o and 65o W., in northern and eastern Bolivia. The name applied to these Indians is not of their own origin.[1] They refer to themselves simply as mbia or “people.” But as they have been called Siriono since first contact, and have been thus designated in the literature, I shall use the term.

The area of Bolivia inhabited by the Siriono is situated in the political departments of the Beni and Santa Cruz. It is roughly bounded on the north by the island forests, lying just south of the villages of Magdalena, Huacaraje, and Baures; on the south, by the Franciscan missions of Guarayos; on the east, by the Rio San Martin; and on the west, by the Rio Grande and Rio Mamoré. Within this extensive area the Siriono have lived and wandered in isolated pockets since the first European contact with them in 1693.

Until the 1930s, a great many Siriono were living in the islandTorests of the Mojos plains east of Trinidad and between the Rio Grande and Rio Piráy, but now most of these have become acculturated and are living under conditions of forced labor on cattle ranches, farms, schools, and missions near Trinidad, Magdalena, Baures, El Carmen, Guarayos, and Santa Cruz. Actually, almost the only unacculturated Siriono extant today are those occupying the forest country southeast of the village of El Carmen. Here, east of the banks of the upper Rio Blanco, is located a range of hills, locally known as the Cerro Blanco, near which wander a few groups of Siriono, who have as yet been unmolested by white contact. There may also still be game living between the Rio Grande and Rio Piráy, but these were not seen by me.

The region occupied by the Siriono is characterized by a tropical climate with two seasons, the wet and the dry. The former lasts from November to May; the latter from May to November. The annual mean temperature (no records available) runs around 73o F., with extremes of 50o F. during the cold south winds from Tierra del Fuego and 1100 F. during the heat of the average day. During the rainy season the climate is very hot and moist with rains on the average of every other day; during the dry season the extreme heat of the day is tempered by cooler nights and occasional cold windstorms from the south. These sures, as they are called by the Spanish-speaking natives of the region, are usually accompanied by rain and a very sudden drop in temperature. They generally last about four days and occur at average intervals of fifteen days during the months of April, May, and June. The prevailing winds, however, are from the north. The average rainfall is about 80 inches per year.

Geographically speaking, the Siriono country is situated in the eastern part of the vast plain, partly forested and partly pampa, lying between the Andes on the west and the Matto Grosso Plateau on the east. From south to north, this plain extends from the hill country north of the Gran Chaco to the low, unexplored hills of Brazil which lie just north of the Rio Guaporé. Within this area, from the Rio Blanco west to the Rio Marnore, are located the extensive llanos of Mojos dotted with the island forests once occupied by Indian groups. East of the Rio Blanco, however, between the Rio Guaporé on the north and the missions of Guarayos on the south, is a vast and dense forest plain which runs for hundreds of miles, and within which the few extant Siriono still wander today. This plain contains occasional low ranges of hills, which are part of the same chain that runs into Brazil on the north and into the Chiquitos region of Bolivia on the south.

Except for the few hills, the area generally is flat and only about five hundred feet above sea level. Both the pampas and the forests are characterized by alturas—high lands that do not flood during the rainy season—and bajuras—low lands that do flood in the rainy season. The alturas are characterized by a resistant capping of partially decomposed lava, containing a topsoil of coarse sand with occasional outcroppings of igneous rock. In elevation they lie some seventy-five feet above the bajuras, which are made up of a heavy, clayey topsoil and which are flooded during most of the rainy season. The alturas of the forest are considered to be the richest agricultural lands, while the bajuras of the pampa, since water stands in many of them the year around, are badly leached and suitable for little more than grazing.

The outstanding watershed features of the region are its numerous lakes and rivers. Of the former there are some twenty large ones in the Siriono country known to me. Around all of these lakes are extensive flood lands, and stemming from each are brooks or arroyos which drain into other lakes or into the principal rivers of the area, the Rio San Martin, the Rio San Joaquin, the Rio Negro, the Rio Blanco, Rio Itonamas (San Miguel or San Pablo), and the Rio Machupo. All of these rivers flow into the Guaporé (Itenez) before it joins the Mamoré (Madeira) in its route to the Amazon. The southwestern part of the area is drained by the Rio Piráy and Rio Grande, which also flow into the Mamoré. Although the rivers are numerous and of good size, the area in general is poorly drained; from the air during the rainy season it has somewhat the appearance of a huge swamp within which there are islands of high ground. All of the rivers follow very capricious courses and are of great age.

The environment, so far as is known, contains no mineral deposits of note. Gold has been reported from the region of the Cerro Blanco, which might be expected in view of the fact that gold is mined in the Chiquitos region to the south and has been mined in the Cerro San Simon to the north, but no deposits of significance have ever been worked. Stone is unknown in Mojos, although a poor grade of igneous rock is found along the Rio Itenez and the Rio Blanco. In the entire region there is no salt.

Present in the area, but not in the abundance that most people are wont to imagine they exist in tropical forests, are the most common types of Amazon Valley fauna. The principal mammals are the tapir, jaguar, puma, capybara, deer, peccary, paca, coati, agouti, monkey, armadillo, anteater, opossum, otter, and squirrel. Bats, including vampires, are a perennial pest.

Land and water fowl are numerous. King of these birds is the harpy eagle. Likewise present, and in greater numbers, are the king vulture and the black vulture, which are almost always seen high in the sky gliding like planes in search of carrion. Game fowl are also plentiful, especially the curassow, guan, wild duck, macaw, toucan, partridge, egret, cormorant, hawk, pelican, plover, kingfisher, trumpeter, spoonbill, and parrot. On the pampa one also frequently encounters the South American ostrich and varieties of ibis.

Of the reptiles, crocodiles and tortoises are plentiful. Occasionally one sees a tega or an iguana. More rarely encountered are snakes, including the anaconda, the fer-de-lance, the bushmaster, the rattler, and coral snakes.

The rivers and lakes of the area are well stocked with fish. Among the principal kinds are the palometa, the pacu, the parapatinga, the tucunaré, several kinds of catfish, and the stingray. Also present but rarely caught is the pirarucu, the largest bony fresh-water fish in the world. Not infrequently seen sporting in the lakes and rivers are schools of fresh-water porpoises, which may come so close as to upset one’s canoe when traveling by water. There are few shellfish and molluscs in these inland waters.

Only one who has traveled in the region can appreciate the myriad forms of insect life that harass the inhabitants. Since a great part of the country is swamp for at least six months of the year, mosquitoes of all kinds (and of which the area is never free) can breed unhampered, and as night falls, these insects, together with gnats and moths, descend upon one by the thousands. During the day, when these pests retire to the swamps and the depths of the forest, their place is taken by innumerable varieties of deer flies and stinging wasps. When traveling by water during the day, one is also perennially pestered by tiny flies which settle on the uncovered parts of one’s body by the hundreds and leave minute welts of blood where they sting.

No less molesting are the ants, most of which are stinging varieties. The traveler in the forest soon learns what kinds to avoid. Especially unpleasant are those which inhabit the tree called palo santo, the sting of a few of which will leave one with a fever, and the tucondera, an ant over a half inch in length whose bite causes partial paralysis for an hour or two.

In addition to the ants, mosquitoes, and flies, there are scorpions and spiders, whose bites may also cause partial paralysis and for whose presence one must be continually on the lookout, and sweat bees, who drive the perspiring traveler to a fury in trying to escape them. Some mention should also be made of the wood ticks, which range in size from a pin point to a fingernail. During the dry season as many as a hundred may drop from a disturbed leaf onto a person as he passes by. One of the most common pastimes of the Indian children is picking off wood ticks from returning hunters.

The flora, like the fauna, is typical of the Amazon River Valley. The forests may be characterized especially by an abundance of palms, among which the principal varieties are the motacú, asayí, chonta, total, samuque, and cusi. All of these palms yield an edible heart and nuts or fruits, which constitute an important part of the diet of the Indians. No less important in this respect are other fruit trees, particularly the pacobilla, the coquino, the pacáy, and the aguai.

Of the trees not producing fruit few are used by the Siriono. An exception is the ambaibo, the fiber of whose bark is twined into string out of which the hammocks and bowstrings are made. Abundant in the area, however, are such common Amazon Valley trees as mahogany, condurú, cedar, bamboo, massaranduba, itaúba, mapájo, bibosi, palo santo, ochoó, and rubber. Along some of the rivers there are also stands of chuchió (reed), from which the Siriono make their arrow shafts.

The pampa chiefly supports a grassy vegetation that is able to withstand extremes of wetness and dryness. Rows of palm are sometimes encountered on the pampa, but more often than not these plains are barren of trees as far as the eye can see.

Physical Type

Because of the lack of accurate instruments while I was in the field, I was unable to record exact physical measurements of the Siriono. Roughly speaking, however, it can be said that the men average about five feet four inches in height; the women, about five feet two inches. The cephalic index falls within the range of brachycephaly to mesocephaly; the nasal index is definitely platyrrhine.

Except in the cases of obvious crosses (the area has not lacked travelers and monks, some of whom may have left their marks) skin color is very dark—almost Negroid. The same may be said for the hair, which is not only jet black, but coarse and straight as well. The eyes are a deep brown in color; the Mongolian fold is marked.

Pilosity is not pronounced but is greater than in most Indian groups. Some of the men have well-developed beards, and all have a full growth of pubic hair, with a lesser growth of axillary hair. Women show marked differences with respect to pubic hair; some have heavy growths while others have almost none at all.

Head hair is extremely thick on both sexes and grows to a very low line on the forehead. Children are always born with a full head of thick hair, and the extension of the hairline to a point very low on the forehead is also very striking at birth.

Except for a very poor development of the lower legs, the Siriono are well-constructed physical specimens. Ontogenetically, they seem to fall within the normal human range. The men demonstrate a marked growth of the shoulder muscles as a result of pulling the bow; the women tend strongly to distended abdomens and pendant breasts, especially after childbirth. The protruding stomachs frequently found in children are almost always due to parasites.

As a result of the habit of picking up objects between the big and the second toe, most men and women possess well-developed prehensile toes. One rarely sees an Indian retrieve anything from the ground with his hands that he is able to pick up with his feet.

An unusual physical characteristic among the Siriono, one which might almost be called a mutation, is the small hereditary marks which characterize the backs of their ears. These marks or depressions in the skin, which appear at birth, look as if a little piece of flesh had been cut out here and there. If a Siriono were in doubt as to whether he were talking to one of his countrymen he would need only to look at the backs of his ears to identify him. These marks do not appear in any of the crosses I have seen. Most of the Indians with whom I talked, however, were only vaguely conscious of this characteristic and had no explanation for it.

Another unusual feature of the Siriono is the high incidence of clubfootedness. This trait appears in about 15 per cent of the population. At some time in Siriono history this recessive character has appeared and persisted because of the highly inbred character of the group.

Chapter II: History

The Siriono are an anomaly in eastern Bolivia. Widely scattered in isolated pockets of forest land, with a culture strikingly backward in contrast to that of their neighbors, they are probably a remnant of an ancient population that was exterminated, absorbed, or engulfed by more civilized invaders. Their language, however, is Tupian, elsewhere spoken by tribes of a more complex culture, but here represented only by themselves and the Guarayos, whose dialects are closely related. Traditions of friendship suggest that these peoples may once have been linked by a now obscure bond.

With the rest of their neighbors the Siriono show few affinities, cultural or linguistic. To the north and west live the warlike Moré, with whom they have had no contact. To the west are settled the Mojo, with whom they likewise have had little intercourse. Only in recent times have they associated with the Baure and Itonama, who reside to the north and who have been acculturated since the days of the Jesuits. Whenever possible they avoid clashes with the so-called Yanaigua, who wander to the south and who occasionally raid them, killing their men and stealing their women and children.

It is probable that the Siriono are of Guarani origin, that they have gradually been pushed northward into the sparsely inhabited forests they now occupy, and that in the course of their migrations they have lost much of their original culture. There is no evidence, cultural or linguistic, however, to support the theory held by Nordensldold (1911, pp. 16–17) that they represent a substratum of culture which once existed widely in the area they now occupy. The intangible aspects of Siriono history still await reconstruction.

Our previous knowledge of the Siriono, which is very scanty, dates from 1693, when they were first seen for a few days by Father Cyprian Barrace.[2] At that time the Siriono were occupying the deep forests in the southern part of the same region which they inhabit today. After first contact, and before their expulsion in 1767, the Jesuits probably made several attempts to missionize them. At any rate, in 1765 a few Siriono were coaxed into the mission of Buena Vista and were later transferred to the mission of Santa Rosa on the Rio Guaporé. So far as we know, no other attempt was made to missionize them until comparatively recent times. Of these endeavors most have failed, not so much because of warlikeness, since this character has been falsely attributed to the Siriono, but because of their sensitivity to maltreatment and their adherence to nomadic life.

In 1927, decimated by smallpox and influenza, a small group of Siriono was settled at the Franciscan Mission of Santa Maria near the Rio San Miguel. This venture did not result in success. In 1941 I met many Indians in the forests between Tibaera and Yaguarú who had formerly been living in Santa Maria but who had reverted to a nomadic existence because of what they regarded as unsatisfactory conditions of life at the mission. In 1935 American evangelists founded a mission for the Siriono at the site of an old Mojo mound called Ibiato, some sixty miles east of Trinidad. By 1940 this mission had a population of about 60 Indians, but could also not be called a successful undertaking for lack of funds and trained personnel. The same may be said for the Bolivian Government Indian School established at Casarabe—fifty miles east of Trinidad—in 1937. However noble in its purpose, the function of this school ultimately resulted in the personal exploitation of the Indians by the staff so that through maltreatment, disease, and death the number of Siriono was reduced from more than 300 in 1940 to less than 150 in 1945.

Of the remaining Siriono who have abandoned aboriginal life, a great many are living today under patrones on cattle ranches and farms along the Rio Blanco, Rio Grande, Rio Mamoré, and Rio San Miguel; others, who were captured as children in the forests, are now acting as servants in the villages of Magdalena, El Carmen, Huacaraje, and Baures. As to the distribution of the Siriono south and southwest of Guarayos, I have no information because I never visited this area and the literature tells us nothing. However, the total population of the Siriono today is probably about two thousand.

Alcide dOrbigny, the great French scientist and explorer, was the first writer of any importance to mention the Siriono. In 1825 he had an opportunity to study a few captured Siriono at Bibosi, a mission north of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Since d’Orbigny’s remarks on the Siriono were the first of any significance ever to be published, I quote them in extenso:

Less numerous than the Guarayos, the Siriono live in the heart of dark forests which separate the Rio Grande from the Rio Piray, between Santa Cruz de la Sierra and the Province of Moxos; from 17o to 18o south latitude and about 68° longitude west of Paris. The Siriono inhabit a large area although, according to many captives from this tribe whom we have seen at the Mission of Bibosi, near Santa Cruz, their number hardly reaches 1000 individuals.

No historian has spoken of them; their name appears only in some old Jesuit letters. According to the information we obtained in the country, the Siriono are perhaps the remains of the ancient Chiriguanos, having since the conquest always inhabited the same forests. Attacked by the Inca Yupaugui about the fifteenth century, they were forced at the beginning of the sixteenth century to flee from the Guaranis of Paraguay, who captured their settlements and, according to historians, annihilated them. Be that as it may, it is possible that the Siriono, well before the Chiriguanos, had come from the southeast and had migrated into areas far distant from the cradle of the Guarani nation.

The Siriono five under the same conditions as the Guarayos and have about the same color, stature, and fine proportions, judging from the few we have seen. In general, their features are the same, but they have a more savage appearance, a fearful and cold expression which is never encountered among the Guarayos. Since they have the custom of depilating their hair we cannot say whether they have as bushy a beard as the Guar ayos.

We have been assured that their language is the Guarani, but corrupted to the extent that they cannot understand the Chiriguanos perfectly. As to their personality, it differs essentially from that of the Guar ayos; they are so savage and hold so strongly to their primitive independence that they have never wanted to have contact with Christians. No one has been able to approach them unarmed. Their forebearers were gentle and affable, but these are less communicative. They live in scattered tribes which wander deep into the most impenetrable forests and live only by hunting. They build rude huts formed of boughs and know no other comforts of life; everything indicates that they live in the most savage state. They have no other industry than the making of weapons. These consist of bows eight feet long and arrows even longer, which they most often use seated, both the feet and hands being employed to shoot with great force; thus they are obliged to hunt only big game. Both sexes go entirely nude, with no clothing to burden them. They do not paint their bodies and wear no ornaments. On their trips they do not use canoes. If they have a river to cross they cut liana which they attach to a tree or to stakes placed for that purpose on the banks of the river. They wind the liana around tree trunks resting in the water, thus forming a kind of bridge which the women cling to in crossing with their children. Whenever they get the opportunity they attack the canoes of the Moxos and kill the rowers to obtain axes or other tools. This is all we have learned about this tribe, without doubt the most savage of the nation [D’Orbigny, 1839, trans., pp. 341–44].

José Cardus was the next writer of any significance to deal with the Siriono. In his book on the Franciscan missions of eastern Bolivia (Cardus, 1886, pp. 279–84) he devoted about five pages to a description of the condition and culture of the Siriono in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Following Cardus, Nordenskiold (1911, pp. 16–17) interviewed two Siriono on his 1908–9 expedition to eastern Bolivia, and on the strength of this published a two-page article about them which, however, contains very scanty data. In 1910 Theodor Herzog (1910, pp. 136–38, 194–200) published a short account of the geography of the area which also embodies a few notes on the Indians. In 1928 Eduard Radwan (1929, pp. 291–96) wrote a brief description of Siriono culture which deals primarily with their contacts with the Franciscan fathers at Santa Maria.

Some years ago, considerable stir was caused in the anthropological world by a publication of a series of articles and books by Richard Wegner (1928, pp. 369–84; 1931; 1932, pp. 321–40; 1934b, pp. 2–34) on a month’s journey to the Siriono country—to the Siriono between the Rio Piráy and Rio Grande and to those of the Mission of Santa Maria. In his various articles and books Wegner claimed to have discovered a primitive group of Siriono which he called Quruñgu’a, who possessed no language but whistling. Although this statement is patently absurd—I too have been with groups of Siriono who were uncommunicative for long periods of time—it should be pointed out that Wegners observations on the material culture, although not outstanding, are fairly accurate. However, his statements about language (or its lack), group classification, religion, and other subjects do not check with my findings, nor with those of the Franciscan monk Anselm Schermair (1934, pp. 519–21), who has written a brief article refuting the claims made by Wegner. My own data substantially agree with those of Padre Schermair, in so far as he has published them. For many years this Franciscan father has been collecting a vocabulary of the Siriono language, but his works have never been published. They will be awaited with great interest.[3]

In 1937 Stig Rydén spent three weeks collecting ethnological specimens and interviewing Indians at Casarabe. His results were published in 1941. Although the descriptions of his material collections are accurate enough, Ryden’s statements about the nonmaterial aspects of culture are mostly inaccurate because he was probably deceived by staff members of the school at Casarabe into recording false information about the Indians. Moreover, lacking adequate primary data, Rydén padded his work with irrelevant speculations and comparisons which are largely meaningless for the reconstruction of Siriono history.

Finally, it should be mentioned that most of the extant data on the Siriono were admirably summed up by Alfred Métraux (1942, pp. 110–14).

Chapter III: Technology

Technologically speaking, the Siriono can be classified with the most culturally backward peoples of the world. They subsist with a bare minimum of material apparatus. Being semi-nomadic, they do not burden themselves with material objects that might hamper mobility. In fact, apart from the hammocks they sleep in and the weapons and tools they hunt and gather with, they rarely carry anything with them. What few other material objects they make and use are generally hastily fashioned at the site of occupancy. A brief account of the principal technological processes and manufactured articles with their uses follows.

Fire

Fire-making is a lost art among the Siriono with whom I lived. I was told by my older informants that fire (táta) used to be made by twirling a stick between the hands, but not once did I see it generated in this fashion. Fire is carried from camp to camp in a brand consisting of a spadix of a palm. This spongy-like wood holds fire for long periods of time. When the band is traveling, at least one woman from every extended family carries fire along. I have even seen women swimming rivers with a firebrand, holding it above the water in one hand while paddling with the other.

In the hut every family has its own fire on the ground by the side of the hammock. Dried leaves of motacú palm are used to bring a fire to a blaze. Any dried or rotten wood serves as firewood (ndéa). The logs are placed on the ground like the spokes of a wheel, the fire being made in the part corresponding to the hub. As the ends of the logs bum down they are pushed inward. Cooking pots are placed directly on the logs. No hearths are employed.

Glue Manufacture

The only native “chemical” industry is the making of glue from beeswax (inti). This product is used extensively in arrow-making. The crude beeswax collected from the hive is put in a pot, mixed with water, and brought to a boil. While it is cooking, the dirt and other impurities are removed. The wax is then cooled and coagulated into balls about the size of a baseball. When desired for use, the wax is heated and smeared over the parts to be glued. It is generally but not always the men who prepare and refine beeswax.

Textile Industries

String and rope are twined by the women from the inner bark of the ambaibo trees. The tree is usually cut down by the men, who remove the outer bark in strips, pull the inner bark from them, and carry this back to camp. It is then thoroughly chewed by the women and placed on a stick over the fire to dry. The resulting shreds are twined into bowstrings, hammock strings, hammock ropes, and baby slings.

One of the most time-consuming activities of the women is the spinning of cotton thread (nin/u). The spindle is made by the men from chonta palm. It is planed into shape with a mussel shell. It is more or less circular in cross section and about a half inch in diameter at the middle; it is pointed at both ends and is about three feet long. The whorl consists of a disc of wood or baked clay which is put on the spindle from the bottom end.

The women prepare the cotton for spinning. The balls of cotton are first collected from the plant and then pulled apart and flattened into paper-thin sheets about six inches square from which the impurities are picked out. The cotton is then ready for spinning. During this process the woman is seated, usually in the hammock. The squares of unspun cotton rest on one thigh (a distaff is not employed) and the spindle on the other, with the whorl end resting on the ground at an angle of about 60°. The woman pulls a threadlike line of cotton from one of her squares, attaches it to the spindle, and spins it into thread by rolling the spindle on the thigh from the hip to the knee. As the thread accumulates, it is rolled around the bottom of the spindle. Cotton thread is employed extensively in arrow-making, for wrist guards, in twining baby slings, and in decorating the body on festive occasions. It is generally coated with uruku, a red paint made from the seeds of Bixa orellana.

The hammock (kiza) is the principal article of furniture in every Siriono hut. Hammocks are made by the women from string twined from bark fibers of the ambaibo tree and are very durable, lasting several years with the roughest treatment. In making a hammock a woman first digs two holes in the ground with her digging stick, as far apart as the length of the hammock is to be. Two posts about five or six feet long are then planted in the holes. The woman ties one end of her ball of string, previously twined, to the bottom of the post on her right, passes the string around the post to her left and back on the far side around the post on her right, and so on, continuing these winds, which are about one fourth of an inch apart, up the poles until she calculates that the desired width of the hammock has been reached. The resulting warp strings fonn two series of parallel lines, one at the front and the other at the back of the posts.

The weft strings are made of the same material as the warp strings, but are finer-twined than the latter. They are applied from bottom to top. The weaver places a weft string around the bottom warp string at the front of the posts and midway between them. She holds the warp string with her left hand and pulls both ends of the weft string tightly with the other hand to form two weft strands of equal length. She then takes the under strand in her left hand, crosses it over the upper strand which is held in her right hand, and then transfers each strand to the opposite hand, after which she pulls the twist tightly around the warp string. She then takes the first back warp string, pulls it over until it rests on the twist formed around the first front warp string, and gives the weft strands a second twist. She continues alternately to gather up the warp strings from front to back until all of them are held in place by a weft string, the ends of which are finally tied into a square knot at the top of the hammock. Usually about a dozen weft strings, placed about six inches apart, suffice for a hammock. After they have been applied, ambaibo bark fiber is bound around the hammock about four inches from each end, and it is then ready for hanging.

Hammocks vary in size, but one shared by husband and wife will be about six feet in length and about four feet in width. It usually takes a woman a full day to make a hammock, once the string has been prepared. Hammocks are almost always carried along on expeditions or hunting trips, but in case a person gets caught overnight in the forest without his hammock, a rude one is sometimes fashioned of liana in the manner described above.

Baby slings (erénda) are twined by the women in exactly the same way as hammocks, the only difference being that they are more often made of cotton than of bark-fiber string and that all the front warp strings are held together by one series of weft strings while those at the back are held together by another. During pregnancy a woman usually twines a new sling so as to have it ready when her infant is bom, for a new sling is made for every child. Slings are about three feet long and two feet wide.

Baskets (ináku) are plain and are made by the techniques of checkerwork and twilling. They may be classified into two types: those hastily constructed in the forest for carrying in game, wild fruits, or other products, and somewhat better ones woven for the storing of articles in the house. The former are always made of the green leaves of the motacú palm (by either the men or the women) and are thrown away as soon as their purpose has been served; the latter are more carefully woven (almost always by the women) of the ripe leaves of the heart of the motacú palm, and are a more or less permanent feature of every Siriono hut. Special baskets are made for storing such things as feather ornaments, pipes, cotton and bark-fiber string, necklaces, calabashes, beeswax, and feathers for arrows and ornaments. When the band is on the march, the various small baskets are placed in one large basket and are thus transported to the next camping spot.

In addition to baskets, women occasionally weave mats from the heart leaves of the motacu palm. These are used to sit on, to roll out coils of clay for potmaking, and to wrap the bodies of the dead. Fire fans are also woven by the women. The Siriono do not manufacture any type of barkcloth, nor do they use hides for anything but food. Feathers are applied to arrows and are used to make ornaments for decorating the hair, but featherwork as an art is not practiced.

Ceramics

The pottery industry is poorly developed, but rude, plain pots (ñéo) are occasionally made by the women. Since more food is broiled or roasted than boiled or steamed, a family rarely possesses more than one pot.

The banks of rivers serve as the principal source of clay. It is dug out by the women with the digging stick and carried home in baskets. In making a pot, the lumps of clay are first mixed with water and with carbonized seeds of the motacú palm, which constitute tlie temper. The resulting mixture is made into balls, from which coils for the sides of the pot are rolled out, and into discs, from which the base of a pot may be formed.

The base is molded, either out of a disc of clay (in case the bottom of the pot is to be rounded) or out of a small coil (in case it is to be more pointed). It is molded entirely with the fingers, and when finished is placed in a slight depression in the ground into which ashes have been put to serve as a cushion.

The rest of the pot is constructed by the coiling technique. After the base has been molded, the coils are rolled out one by one on a mat of motacú palm and applied in turn. In making a pot a woman works the coils of clay together with her fingers, on which she frequently spits. In addition, she employs the convex surface of a mussel shell called hitai to smooth out the clay. After one or two coils have been added to the base of the pot, it is generally left standing to dry for a day before others are added. In this way the pot does not lose shape by having too much weight at the top when the clay is wet. Thus several days commonly elapse before a pot is complete. Once finished, it is left to dry in the shade for about two days before it is baked.

Pots are baked in the hot ashes of an open fire. As each section of a pot hardens, it is turned slightly so as to bake another. Sometimes a pot is covered with green boughs and chips while it is baking to maintain an even heat. Since the method of baking is very crude, pots are very fragile and must be handled with great care. They vary in size from about five to ten inches in diameter at the top and from about eight to fourteen inches in height.

Pipes (keákwa), like pots, are made from a mixture of clay and carbonized seeds of the motacú palm. The entire pipe, including the stem, is molded from a single disc of clay, the fingers alone being used. As a woman molds the bowl, she leaves a small lump of clay at the bottom from which the stem is later fashioned. After finishing the bowl, she fashions this lump into a conelike shape and then inserts a palm straw into the bowl to make the hole for the stem. She then molds the lump of clay bit by bit around the straw until the stem of the pipe is of the desired length, leaving a little decorative projection at the bottom of the bowl which is called éka or teat.

After a pipe has been molded it is dried in the open air for a couple of days and then baked in the coals of a fire like a pot. In baking, the straw in the stem is burned out, leaving a hole through which to suck the pipe.

Circular spindle whorls are sometimes made by women from a small disc of clay hardened in the open fire like a pipe or a pot. Before they are baked they are fitted onto the spindle so that the hole in the whorl will be of proper size.

Utensils

Calabashes (yabóki) are prepared as drinking vessels in the following manner. A round hole about an inch in diameter is cut in the top of a gourd with the gouging tool. A small stick is then inserted, and the seeds are loosened and shaken out. The calabash is then washed on the inside and dried slowly in the fire, water being squirted on the outside from time to time to keep it from burning. Calabashes, though used primarily as drinking vessels, are also employed for making mead and for storing tobacco, feather ornaments, and animal teeth.

When calabashes are scarce, hollow sections of bamboo are sometimes used as drinking vessels, to store wild honey, or to make mead. They are simply cut to the length desired.

Mortars (mbúa) are sometimes hollowed out of fallen logs that lie near camp, but sections of a log are never cut especially for this purpose; that is, a section of a log is not cut, set up, and hollowed out on the end for use as a mortar. To make a mortar, a hole is made in the side of a fallen trunk with fire, the charcoal being chipped out with a digging stick, which also serves as the pestle. Mortars are used principally for grinding corn for food and mead, and for grinding burned motacú seeds for temper for pots. They are never carried from camp to camp.

No spoons, plates, bowls, or bags are manufactured by the Siriono. Pots and baskets have already been described.

Tools

The digging stick (siri)— the only agricultural tool —is made by the men from chonta palm. After a section of wood has been removed from the tree, it is planed to the desired shape with a mollusc shell called urúkwa. The digging stick is about three feet in length, three inches in width, and about an inch in thickness. The bottom end is sharpened so as to make it a more effective tool. The digging stick is used principally in planting and tilling, in grinding com, in digging out clay for pots, and in extracting palm cabbage and honey.

The Siriono construct a gouging tool by hafting an incisor tooth of an agouti or paca onto a femur of a howler monkey. This tool is employed principally to gouge out the nock in the reinforcing plug which is inserted in the feathered end of the arrow. In using the tool the handle is grasped in the right hand with the tooth down. The plug is held in the left hand, and the tool is worked back and forth over it until a groove large enough to hold the bowstring is made. This tool is also employed in making holes in the root ends of tlie animal teeth from which necklaces are strung.

Some mention should also be made of the use of a mollusc shell, called urúkwa, and a mussel shell, called hitai, as tools. The former is used by the men as a plane in making digging sticks, spindles, and bows, while the latter is employed by the women to smooth out the clay when making pots. The mandible (with teeth) of the palometa fish also serves as a tool, being employed to sever the aftershafts of the feathers glued on arrows. Any piece of bamboo serves for a knife but no work is done in bone, horn, shell, stone, or metal. European axes and machetes have been introduced to those bands which have had contact, but under aboriginal conditions European tools are rarely encountered.

Weapons

The bow (ngicLi) and arrow are the only weapons manufactured or used by the Siriono. Every adult male possesses a bow and arrows which he makes himself. So important are these weapons that when not hunting, a man, if busy, is most frequently observed making a new arrow or repairing an old one broken on the last hunt. A man’s bow and arrows, in fact, are his inseparable companions. When he is asleep in the house they rest upright against the frame pole to which his hammock is tied, and when he is walking in the forest he is invariably seen with his bow and a bundle of arrows over his right or left shoulder, points facing ahead, in quest of game.

The wood from which the bows are made is a variety of chonta palm, called siri. This tree, when mature, is about twelve inches in diameter and has a layer about two inches thick of very hard black wood just underneath the bark. It is from this layer that the bow is constructed. Although the material is relatively abundant in the environment, before making a new bow a hunter will search for some time to locate a chonta tree which has the appearance of being of proper maturity and hardness. It is a rare tree that has just the right qualities. The wood must be firm and resilient and must withstand the maximum pulling strength of the hunter without breaking. Frequently I have seen a man spend a couple of days in the construction of a bow only to have it snap on the first pull.

After a suitable tree has been sighted it is felled. I have never seen this done other than with an axe, but one of my oldest informants told me that he had known chonta palms to be felled by building a fire against the trunk until the hard layer had been burned through and then pushing the tree over. When a tree has been felled, a section of the circumference of the trunk, about four inches wide and as long as the hunter wants his bow to be, is cut out. Other smaller pieces of chonta may also be removed at this time, as this material is likewise indispensable in the construction of arrows.

Once the material has been taken out, work on the construction of the bow begins almost at once, before the wood dries out. Bows are plain and are made of a single stave. The making of a bow is a laborious process, as it is fashioned almost entirely by using mollusc shells, called urúkiva, to plane the wood down. A small hole is first made in the surface of one of these mollusc shells. The edges around the hole are then worked downward with the grain, and the section of wood is gradually planed to the desired shape. If a man possesses a machete, he may first use this to give the bow its approximate shape by roughly tapering the horns, but the finishing is always done with the shell to avert the danger of splitting the wood. In planing down a bow it is held securely on the ground between the big and the second toe.