Amit Pinchevski & Roy Brand

Holocaust Perversions: The Stalags Pulp Fiction and the Eichmann Trial

The Fantasy Companion to the Trial

Intrusion of Reality into Fantasy

The Stalags, an Israeli pulp fiction series whose advent coincided with the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, portrayed sadomasochistic scenarios between SS female guards and Allied soldiers in POW camps. Written in Hebrew by native Israelis, these cheap pocketbooks were enormously popular with Israeli teenagers, many of whom were children of Holocaust survivors. We posit the Stalags (a) as a fictional counterpart of the trial, complementing the legal procedure with feats of the imagination, and (b) as a text upon which the Israeli young generation negotiated issues of power and identity.

Keywords: Holocaust Memory; Pornography; Pulp Fiction; Israel; Representation of Nazism; Trauma

During an interview with Cahiers du cine´ma, Michel Foucault commented on a contemporary trend: “How could Nazism, which was represented by lamentable, shabby, puritan young men, by a species of Victorian spinsters, have become everywhere today*in France, in Germany, in the United States*in all the pornographic literature of the whole world, the absolute reference of eroticism?” (cited in Friedlander, 1984, p. 74). Others noted a similar trend in Western culture starting in 1970s (Friedlander, 1984; Sontag, 1980). Not surprising, Israel did not figure in Foucault’s list of countries where Nazism became a marker of eroticism. The Jewish state, established only 3 years after the end of the war and home to many Holocaust survivors, would hardly seem the place for such iniquities. Yet, it was in Israel that a local genre of erotic pulp fiction involving Nazi characters gained enormous popularity in the early 1960s. The Stalags were renowned for their scenes of domination, torture, and sadistic sex, most characteristically between SS female guards and Allied soldiers in German POW camps. Written originally in Hebrew by native Israelis and published by small publishers in Tel Aviv, these cheap pocketbooks were particularly favored by Israeli teenagers, many of whom were children of Holocaust survivors. Significantly, the advent of this pulp coincided with the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

The Stalags have remained largely overlooked in most historical accounts of the period, figuring at best as a literary curiosity (Bartov, 2000; Ben-Ari, 2006; Eshed, 2002). Perhaps this low-culture specimen was not considered important enough to merit serious deliberation, let alone exclusive examination. Yet it may also be that the topic was deemed too self-evident, its implication too predictable: It could easily be explained away by what Foucault identified as a general trend “everywhere today,” by what Sontag (1980) referred to as “fascinating fascism,” or by what Friedlander (1984) dubbed as “kitsch and death.”[1] In other words, the Israeli pulp as yet another example of the postwar cultural obsession with representing Nazism as inherently decadent. But such explanations remain on the universal level and offer little insight into the specific cultural context of production and reception. That Nazism has become everywhere today a reference of eroticism, as Foucault suggests, does not entail that this juxtaposition means the same thing everywhere. This is all the more true in the case of the Stalags: putting Israel in the same category as France, Germany or the U.S. not only discards the specific post-Holocaust context at issue here but also the critical conjunction with the Eichmann trial. Thus, any speculation on the significance of the Israeli pulp must go beyond general, abstract explanations towards a more nuanced, culturally specific examination.

The Stalags, we argue, constituted an early response to the trauma of the Holocaust. We propose reading the Stalags as a fictional counterpart of the Eichmann trial, supplementing the legal procedure with various feats of fantasy. Moreover, the Stalags can be read as a cultural text upon which the young generation negotiated issues of power, identity, and sexuality vis-a‘-vis the parents’ generation on the one hand, and Zionist ideology, on the other. This interpretation highlights a crucial fact: for young Israelis of that time, coming to know about the Holocaust was intimately linked with the coming of puberty and the initiation into national identity. The Stalags reveal a generation’s simultaneous initiation into adulthood, nationhood, and victimhood. Appearing against the background of a transformative event in Holocaust memory in Israel, the Stalags weaved fantasy and transgression into a cultural text that accompanied the trial. As such, they testify to the way initial revelations of the traumatic past were incorporated and imagined in the minds of young Israelis in the early 1960s.

Chronicle of a Fad

The Stalags first hit the newsstands a few months after the trial of Adolf Eichmann opened in April 1961. Emerging at a time when pulp fiction industry in Israel was at its highest level of production, the Stalags were more than just another variation of erotic literature. They quickly became their own genre, outstripping the popularity of previous and contemporary pulps. The German contraction for stammlager (“base camp”), which during World War II came more specifically to denote a POW camp, entered the Hebrew language only to become synonymous with tales of sadistic sex in Nazi camps.

Many Stalags featured the same authors: Mike Baden, Victor Boulder, Kim Rockman, Erich Lindstrom, Mike Longshot, and Ralph Butcher were among the recurring names, often also as narrators. Although published and sold as translated fiction, all paperbacks were in fact written originally in Hebrew by native Israeli writers. The foreign-sounding pseudonyms were probably taken for commercial reasons, so as to add allure and believability to the plots. They might have also served to distance the plots from the immediate context and thus allow readers to consume the pulp with less guilt. For additional authenticity, each volume contained a name of a fictitious translator, often alongside banners such as “For the first time in Hebrew, no abbreviations, superb translation.” The actual writers of these pocketbooks were a small group of aspiring authors and journalists supplementing their income.[2]

The first of the series, Stalag 13, tells the story of Mike Baden, a British pilot held in a German POW camp. His experiences seem to follow the standard course of wartime captivity, until one day the camp’s SS staff is unexpectedly replaced by another unit:

There was nothing peculiar about the soldiers.... Nothing exceptional, but the physical fact that the soldiers were women. Two platoons of female SS storm troopers, wearing tight pants, shining boots, and vests from cloth that stretched across tall and upright breasts. Beneath the caps sprouted short army haircuts, but the hair was fine and the necks feminine and slim. (Baden, 1961, p. 60)[3]

Before long, the camp is run exclusively by the female officers, who proceed to dominate the men through menace, torture, and sexual abuse. Even as they plot rebellion, the soldiers are compelled to obey their sex-crazed dominators with a mixture of pleasure and revulsion. Finally, the men take revenge on their female captivators by means no less brutal than they had suffered themselves.

Stalag 13 appeared in four editions within a year and sold more than 25,000 copies*a bestseller even by today’s Israeli standards*and in three additional editions the following year, doubling the total sales. Its theme set the tone for the Israeli pulp fiction industry.[4] The first edition of Stalag 217, issued by the same publisher, sold out in less than a week. Its back cover promised a story even more cruel and more daring than its predecessor: “a true and brutally honest story of the lives of male captives bound by sadistic girls ... women whose entire essence is based on the brimming lust for the blood of others, for deriving sadistic pleasure from their pain, and for exploiting the manhood of the captive at their mercy.” Several small publishers set out to join the fad: pirating the Stalag brand name, they produced dozens of similar pocketbooks, many of which also reached thousands of readers countrywide. Subsequent titles included Stalag 3, Stalag 7, Stalag 10, Stalag 33, Stalag 69, Stalag 190, and so on to Stalag 1000. The more or less serial titles were soon replaced by more dramatic ones, such as Stalag of the Devils, Stalag of the Wolves, Women’s Stalag, Death Stalag, and I Was a Stalag Commander. Later versions relocated the setting from a German camp to camps of similar nature in Japan, Russia, Algiers, and Syria*Geishas Stalag, Stalag Stalingrad, Stalag of Experiments, and Desert Stalag. All in all, more than 70 titles of various publishers were published before the Stalag craze declined in 1965.[5]

A common element in many Stalags is a dominatrix commanding a unit of female guards. Some stories provide the rationale for female domination in the camps: during the Normandy campaign, all German men were shipped to the battlefront; this left home-front jobs to women. Female antagonists are often portrayed with much detail*not only their physical appearance, but also their emotional states, personal background, motivation, and desires. Some appear as the fictional counterparts of actual figures, such as Ilsa Koch, Irma Grese, and even Leni Riefenstahl, whose fictive counterpart appears in one of the last Stalags.[6] Notably, the Stalags almost never featured Jewish characters. Apart from an occasional reference to Jews in a handful of Stalags, all remaining titles refrained from directly involving anything Jewish in the stories. The focus was predominantly on the Anglo-Saxon versus the Axis-of-Evil. Publishers may have reckoned that as long as they portrayed German brutality against British or American prisoners, their books could pass as merely distasteful and thus avoid censorship.[7]

The popularity of these pulps is evident from a 1963 survey of the reading habits of 18-year-old Israelis. The Hebrew University sociologist was dismayed to find that most respondents reported reading pulp fiction on a regular basis; the majority mentioned Stalags as their favorite genre (Goldstein, 1963). Also in 1963, an episode entitled “Stalags Epidemic” of a popular radio show featured a father who is horrified to find his daughter reading a Stalag under the table during dinner; she indignantly retorts: “But, daddy, everyone’s reading this!” (Ben-Ari, 2006, p. 170). The Stalags’ popularity soon became a source of much concern. Newspapers reported on the “perverted literature” available everywhere, most scandalously at newsstands near schools, “the great attraction to which the light feet stampede during the intermission” (Goldstein, 1963, p. 8). One commentator singled out the Stalags as “the paperbacks which only sexually sick individuals with twisted imagination could have composed” (Elgat, 1964, p. 3). A Yediot Aharonot editorial called for the burning of the “literary filth”: “It is time to make a big fire and burn books at the stake. Immoral act? Absolutely moral! Because the books presented hereby for extermination are books that educate this generation for immorality” (Shamir, 1963, p. 7). The press was united in demanding that the authorities exercise control over the publication and distribution of printed obscenities. Yet, outrage was not specifically about featuring Nazi characters in pornographic tales but was about pornography per se, which was said to be linked to a rise in criminal activities among the young.

The Israeli authorities, on their part, were not keen to censor.[8] Apart from a couple of cases where publishers were charged (without conviction) for printing obscenities, the pulp fiction market remained generally sanction-free. The only Stalag exception was perhaps the most outrageous of the Stalags, one based on an allegedly true story of a French girl abused by a Nazi officer in occupied France. I Was Captain Schulz’s Private Bitch, published in 1962, caused such a public stir that the police was ordered to remove and confiscate all available copies. In the ensuing court case, the judge was not impressed with the publisher’s argument that the book was harmless and even historically informative, and penalized the publisher for printing obscenities. The book contained explicit scenes of the Nazi officer raping and molesting the book’s narrator, the alleged French girl, who described in the first person how she subsequently took revenge on her subjugator.[9] The ban only worked to heighten the curiosity around the book. Indeed, a competing publisher quickly followed up with a sequel sporting the same cover art and boasting the name Shultz in the title, albeit not nearly as controversial as its prequel.

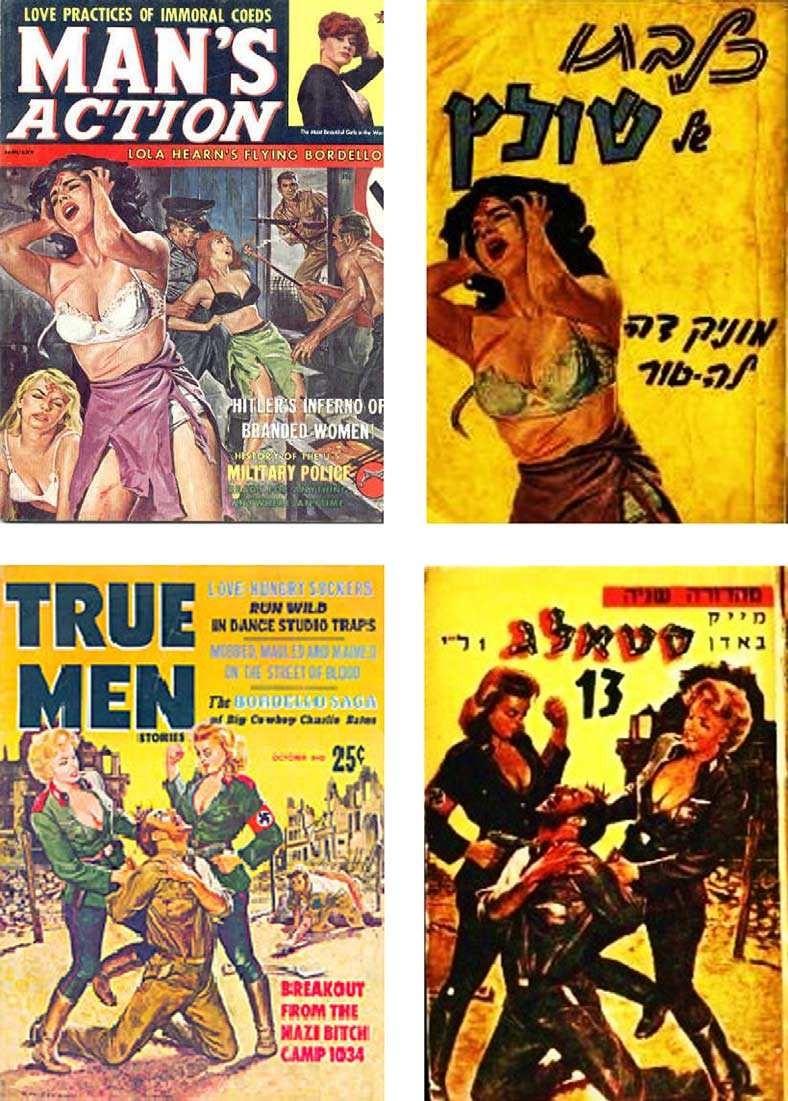

The Stalags were not the first pulp to combine sex and swastikas. The inspiration came from American men magazines that appeared in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s.[10] These “torture magazines” took the traditional concept of men’s adventure to the extreme, featuring stories of unlimited violence alongside lurid illustrations. While American pulps had traditionally depicted damsels in distress, they usually suggested that a hero was on the way to rescue. However, heroes came to play an increasingly marginal role in American men’s monthlies (Parfrey, 2003). In the early 1960s, their place was taken by a new male, a torturer rather than a savior, who typically wore Third Reich regalia with swastikas galore. “Torture magazines” apparently responded to a set of contemporary anxieties in the U.S.*the rise of feminism, sexual liberation and fear of sexually liberated women, the fading of postwar economic boom, racial unrest, and towards the end of decade, the Vietnam War (Savran, 1998; Uebel, 2002). These threats to traditional white masculinity were transported, so it seems, into a phantasmatic realm where Nazi iconography symbolized a suppressed manhood ridding itself from women whose power lies in their ability to seduce.

Some Stalags peculiarities indeed replicate ideas from the American original: for instance, releasing killer ants on prisoners buried with only their heads sticking out of the sand, or female guards etching a swastika onto a prisoner’s chest.[11] More conspicuous is the bootleg reproduction of illustrations from the American pulp, which adorn practically all Stalags’ front and back covers (see Figure 1). Notwithstanding these equivalencies, there are important differences. Whereas the American magazines combined image and text, the Israeli Stalags were almost exclusively text-based, with each title featuring only a cover illustration.[12] And while “torture magazines” were predominantly about male dominance, the Stalags exhibited interplay of roles with a clear preference of female dominance of males. But perhaps most significant is the context of reception, as the advent of the genre in Israel was against a very different backdrop than that of postwar America.

The Eichmann trial marked a watershed between a period of relative silence about the Holocaust and a period in which the Holocaust entered public discourse in Israel (Bartov, 2000; Felman, 2002; Segev, 2000; Shapira, 2005; Yablonka, 2004; Zertal, 2005). Particularly affected by the witnesses summoned by the prosecution were younger Israelis who, although growing up around survivors, only rarely heard them speak about what happened “there,” and almost never dared to ask. Thus, prior to the trial, young Israelis had been exposed only to rudimentary facts of the Holocaust while in school, which emphasized stories of personal sacrifice and heroism. Educating the young was one of the trial’s original goals, as chief prosecutor Gideon Hausner (1966) declared: “It was imperative for the stability of our youth that they should learn the full truth of what had happened” (p. 292). Hundreds of young people crowded the courtroom everyday, and many others listened to the proceedings on the radio and followed the events in the newspapers (Deutsch, 1974; Pinchevski, Liebes, & Herman, 2007; Yablonka, 2004).

Among the witnesses in the trial was an Auschwitz survivor named Yehiel Dinur, known until then by his pen name, Ka-tzetnik.[13] His books were infamous for unsettling descriptions of brutality, rape, and carnage in concentration camps. These semiautobiographical chronicles were particularly popular among Israeli teenagers, not least for their obscenities. Not surprisingly, Ka-tzetnik’s writings are often associated with the Stalags as examples of “illegitimate Holocaust literature” (Bartov, 2000). According to Bartov, the legitimate Holocaust literature typically consisted of quasi-fictional tales of heroic resistance and sacrifice: children smuggling food and guns into the ghettos, Janusz Korchak going with his students into the gas chambers, heroic youths preferring to die as fighters rather than victims. Focusing on action, sacrifice and meaningful death, these tales were very much in line with Zionist ideology, and therefore used as teaching material in schools. Conversely, the illegitimate materials*the Stalags and to some extent Ka-tzetnik’s books*were passed secretly from hand to hand and kept hidden in backyards, away from adult eyes.[14] Unlike the moralizing narratives propagated by Zionist ideology, the illegitimate texts provided a source of illicit excitement by violating a double taboo*sex and the Holocaust, two domains sanctioned by adults and barred to the young.

The Fantasy Companion to the Trial

Felman (2002) argues that the significance of the Eichmann trial was not ultimately in its legal consequences, but rather that it gave voice to the trauma of the Holocaust. It accomplished this not by successfully translating trauma into legal code but, paradoxically, by failing to do so. It was the inadequacy of the proceedings to accommodate trauma*and the public demonstration of that inadequacy*that marked this trial as a formative event in Holocaust memory. Failing to bring closure to trauma was precisely what did justice to the inexplicability of trauma. Taking Felman further, we suggest the trial also provoked fascination with the inexplicable. We argue that the failure to provide closure to trauma unleashed a phantasmatic potential for imagining what could not be explicated. The Stalags tapped into an imaginary realm opened between what was said through the legal procedure and what remained unsaid. In supplying outlet to public imagination, the Stalags functioned as the fantasy companion to the trial. As such, we posit, the Stalags combined pulp heroism, folk-psychology explanation of Nazism, and displaced repetitions from the trial, which, in turn corresponded with the trial on three different levels: narrative, paradigm, and intertextual.

Heroism and Transgression

The Stalags’ plots are essentially variations of pulp heroism, that is, the unfolding of a hero-protagonist’s exploits in overcoming evil and reinstating cosmic order. But this variant comes with a twist: this brush with evil involves acts of transgression and illicit pleasures. The narrative structure common across the genre consists of three main phases: initial downfall; captivity and transgression; breakout and revenge.

The exposition usually opens with a short conflict by the end of which the protagonist meets an initial downfall. The protagonist, typically an American or British pilot, emerges from the exposition beaten but not defeated, demonstrating endurance and resolve through physical and mental strength*qualities which will later enable him to overcome the vicissitudes of camp life. Stalag 13, for example, opens with combat during which British pilot Mike Baden is shot down over France. Failing to cross the lines back, he finds shelter, is betrayed by a local farmer, and finally arrives at the camp, all without losing his poise. His quality as invincibly macho is thus clear from the outset and remains simplistic and one-dimensional.

The two main themes at the center of each plot are captivity and transgression. The camp is portrayed as an isolated and enclosed microcosm. Moreover, each story makes clear that the Stalag is unlike any other Nazi camp. Although operating under Nazi rule, it is somehow an anomaly to that rule. Hence the camp is portrayed as both an exception to and a realization of Nazism*or better, the place where the aberration and the radicalization of Nazism meet. Under its auspices are eccentricities such as a Nazi project for immortalizing Aryans, horrendous medical experiments on prisoners, or the prostitution of female prisoners by criminals turned guards. Yet the fundamental aberration of the Stalag is the unlikely presence of men and women on opposite sides of the command line. Captivity is therefore portrayed as a laboratory of extreme brutality and at the same time as an orgy waiting to happen.

Indeed what makes this captivity special is the constant potential of transgression within it. The Stalag’s hierarchy and order are repeatedly stymied by means of sexual intercourse, abuse, and torture; in Goffman’s (1961) terms, the Stalag is a total institution gone awry. In it, the prisoners experience a taste of Aryan decadence: the collapse of all that is decent and the excess of everything wicked, a world turned upside down, where all homeland certainties are shattered and GIs are the complacent subjects of seductive Nazi vixens. This situation, along with its forbidden pleasures, stirs in them an internal battle of attraction and repulsion. In such instances, prisoners and guards, Aryans and non-Aryans, men and women, come into contact beyond the prescription of the total institution, entering an indeterminate state in which domination is exacerbated, contested, and finally restored. For instance, in Stalag 217, Lilly tries to seduce a British prisoner who first rejects her yet cannot contain his passion towards her. Soon they are in each other’s hands, suspended between the rule of nature and the rule of the camp. After intercourse, however, they each retire to their designated roles in the camp. Order is restored until the next round. Such turns of events*transgressing previous roles, succumbing to passion, and reinstating previous order*are typical of Stalags’ climactic scenes.

Finally, the common goal of all Allied protagonists is escape. Escape is their principal preoccupation and ultimate achievement, which makes them a crude model for rising up against the enemy and fighting against all odds. Some getaways read as if taken directly from Hollywood war movies, such as the 1963 The Great Escape (itself based on an actual break out of Allied soldiers from German Stalag Luft III in 1944). For the Israeli teens, however, such heroic escapes may have also evoked actual stories of members of Zionist militant groups escaping British prisons in 1940s Palestine; or fictional stories of the young members of Hasamba, a popular teen book series of the 1950s about a secret gang fighting the Arabs, British, and Nazis (see Almog, 2000; Shapira, 1992). At any rate, breaking out is not merely from the camp but from the reality it represents: from the grip of corruption and sin that must be annihilated before the soldiers resume their lives back home. Each plot ends with the war’s end, with Nazis fleeing the camp and seeking refuge from their former captives. But their flight is often short-lived, as after breakout comes revenge. Without exception, all Stalags’ plots end with settling the score against the evil perpetrator. Female commander Octopu-san of Stalag of Leaches is thrown into a pit of leaches dug for an American soldier; Nazi commander of Stalag 69, whose activities include torturing, molesting and killing female prisoners, is hanged by his feet for 2 days; and beautiful but deadly Lilly Metternich of Stalag 217 is tracked down and strangled by her ex-camp lover. Revenge thus restores the cosmic balance between good and evil. Each plot reenacts the motto of crime and punishment, of affliction and revenge, as if preempting the verdict in the criminal case against Eichmann. In sum, in the Stalags Nazi camps are the locus of sin, not carnage; prisoners are potent men and captivators are Amazon women. To paraphrase Hannah Arendt’s dictum, in the Stalags evil is no longer banal*it is exciting. As such, these narratives constitute a counter-narrative to the story of destruction*heroism, victory and sex as the ultimate triumph of libido over death.

Nazi Bipolarity

The Stalags evince a particular paradigm of Nazi mentality. Nazi characters are rendered as inherently bipolar, containing two contradictory elements between which they oscillate. Bipolarity causes them to undergo extreme dramatic emotional shifts. Thus Stalag 217 repeatedly contrasts Lilly’s adolescent naivete´ to her mature cruelty as an avid Nazi: “At first Lilly recoiled from violence ... [but] a strange transformation occurred in her once she saw her friends whipping the screaming prisoners. She felt power, strength, superiority. For the first time she felt herself identifying completely with the idea of the master race” (Boulder, 1961, p. 30). Likewise, the General’s femme fatale wife in Murder in the Stalag is described as seeming gentle, kind, and noble; but on the inside, “underneath the polished fac¸ade, lay the Nazi animal*that wanton creature, debaucher and deviant, in the best fashion of top Nazi regime” (Longshot, 1962, p. 79). In this story, Frau Gertie whips an American prisoner, but when he falls unconscious, she tends to him. To her baffled lover, she suddenly appears as “a completely new figure, an unexpected and surprising figure, which he had not suspected that might exist in this devil woman. At that moment Gertie seemed like a loving mother, taking care of her sick infant.” But when the prisoner refuses to divulge the location of a hidden treasure, “suddenly the loving mother disappeared, and her place was taken by the deceiving, conniving woman” (p. 195).

Noteworthy in this respect is the title I Was a Stalag Commander (1963), which recounts*in the first person*the vicissitudes of a Nazi officer in charge of a women’s Stalag. It tells the story of Colonel Rosenberg, who after being captured and tortured by Russian women, has made it his life’s goal to take revenge on women, particularly of Russian descent. Most striking is the confessional style of this pulp, which offers fictional speculation regarding the thoughts, beliefs, and emotional mindset of a Nazi officer. The name Eichmann appears explicitly when the narrator seeks refuge in South America, where he meets a fate similar to Eichmann’s. The narrator often confesses conflicting emotions, oscillating between sporadic moments of empathy to extremes of bottomless hatred. The portrayal of Rosenberg firmly remains within the scope of human emotions and capacities and, with its confessional style form, allows for a credible character. Conceivably, this Nazi figure complemented perceptions of the actual Nazi who was executed not long before this paperback was published.

The epitome of Nazi bipolarity is of human versus beast. Bestial and animalistic metaphors recur repeatedly in the Stalags but most remarkably in the portrayals of Nazi characters and in the sex scenes. Nazis are often depicted as harboring animal attributes under human skin. Female characters in particular are likened to wolves, snakes, and monsters. This bipolarity ultimately implicates the perception of the body itself, which appears as either superior and thus flawless and desirable, or as inferior and thus abominable and abject. Incidentally, the male Nazis are frequently portrayed as rather refined and effeminate compared to the brutish women. It is as if the change of guards occasioned a more fundamental transformation, not only of command but also of gender role.[15]

As a whole, sex scenes are rarely explicit, unfolding rather conservatively, following Hollywood cinematographic conventions of the 1950s: before, fadeout, and after* and almost nothing of the act itself. Perhaps in puritanical Israel of the early 1960s, where pornographic material was not of much variety, this was enough to excite the imagination. In any event, the description of what leads to sexual intercourse, and sometime of the intercourse itself, is imbued with animalistic metaphors. Again Nazi vixens appear as insatiable beasts prowling for the prey. But here they are joined by the male captives, who fall victim to their own irrepressible passion. A case in point is the Nazi commander of Stalag 13. After drugging two prisoners into submission, she “demonstrated for them what she wanted and they pleased her, squeaking like hairy rats hanged from the vibrating body of an eel.” On another occasion, she treats a prisoner “like she would treat a gorilla or a lion,” scolding him that “other than your physical advantages, which put you in the same company as prehistoric man or the giant heroes of our ancient Germanic legends, you suffer from mediocre mentality” (Boulder, 1961, pp. 164, 165, 180). Lust has reverted both of them to the state of brute nature, to sex-crazed animals, collapsing hierarchy and order into lascivious carnality. In the Stalag when it comes to sex, all are equally animals at base. Yet such animalization carries with it a kind of humanization: if all men and women, Aryan and non-Aryan, are essentially animals, this common animality is ultimately a basis of common humanity.

Thus these pulps offer a philosophy of Nazism and human nature*and of the way the former was extracted from the latter. The Stalags cast Nazism as an unmitigated conflict between instinct and norm, desire and repression, nature and culture, id and superego. Institutionalized within the camp’s regimen, Nazism ushers in the return of the repressed: of animal cruelty, of pagan rituals, of torture and sacrifice. The topsyturvy world of the Stalags suggests that Nazism was an aberration of history as much as women using sex and torture to dominate men is an aberration of nature. In fact, this conception of Nazism, whereby the beast in the human overcame the human in the beast, is not too far from what chief prosecutor Gideon Hausner said at Eichmann’s sentencing hearing:

Adolf Eichmann has removed himself, by his horrendous deeds, from the society of humans. Knowingly and willingly he chose the way of a ravaging predator, exterminating, bloodthirsty, and is incapable of demanding that humanity treat him by normal standards that stand between man and man. He was born a man, but lived his life like a tiger in the jungle. He gave his hand to horrific acts that anybody who carries them out erases human character from his face. For there are deeds that lie beyond the human realm, that are beyond the divide between man and beast. (The Attorney General against Adolf Eichmann, 1962, p. 267)

Significantly, this line of reasoning runs counter to the argument Hausner advocated throughout the trial, namely, that Eichmann’s actions followed from a conscious intention to implement and carry out Nazi ideology. The Nazi criminal as a beast is also at odds with the figure posed by Hausner in his opening speech, that of a “new kind of killer, the kind that exercises his bloody craft behind a desk” (Rosenne, 1961, p. 30). Hausner may have resorted to bestial imagery in order to further dehumanize Eichmann and bolster his demand for the death penalty. Nonetheless, these two key moments of the trial can be read as the paradigm case of Nazi bipolarity: on the one hand, the realization of ideology and instrumental rationality, on the other the incarnation of savagery and corruption. As chronicles of the trial attest, opinions on Eichmann’s mentality were markedly polarized, from “minor bureaucrat” and “simpleton” to “homicidally aggressive” and “schizoid” (Gouri, 2004, pp. 144, 294). It is perhaps from here, from the contradiction between the opposing Nazi archetypes, that fiction followed reality, and the phantasmatic potential opened by the trial was carried over to the Stalags.

Intrusion of Reality into Fantasy

In certain phrases and passages that reiterate, sometimes almost verbatim, the vocabulary and rhetoric heard inside the Eichmann courtroom, the Stalags reveal yet another, more direct, correlation with trial. Like external sounds that get incorporated into a dream, these quotes of fact infiltrate fiction to somehow figure in the plot and render them plausible. Most conspicuous in this respect is the recurring use of the German “Jawohl” (an emphatic “yes” often used in military context) in the Hebrew texts, mostly when a Nazi addresses a superior. This word would have been unlikely to be incorporated in the popular pulp without having registered first with the Israeli public as Eichmann’s standard reply to the judges.[16] Of particular note is an allusion in an early Stalag to a response to the prosecutor’s question, when Ka-tzetnik replied: “This is a chronicle from the planet of Auschwitz.” This phrase became a marker of ultimate evil. What Ka-tzetnik meant by “planet of Auschwitz” is that Auschwitz cannot be articulated within ordinary language; it forever remains beyond description and narration, beyond this world. (Shortly after pronouncing this phrase he collapsed on the stand.) This phrase, with its extraterrestrial connotation, uncannily repeats in the following:

Stalag 217 deviated from the framework of World War II and became an isolated planet in the center of Holland. Totally removed from the rest of the world ... the camp sank in the mire of debauchery. Packages and letters arriving from the outside were like ambassadors from another world, and people would retreat from their planet for a few seconds to read a letter or open a package and then return with a stroke of a hand to their share of sin. (Boulder, 1961, p. 137)

That such a distinctive phrase, so closely connected with a most memorable event in the trial, would so quickly appear in a pornographic pulp indicates some transference of the trial’s testimonial discourse to the imaginary discourse of the Stalags. The indescribable trauma of Auschwitz had somehow transmuted into the all-too-describable imaginary of corruption and sin.

The same goes for entire passages. Consider the description from Stalag 33 of prisoners arriving at the camp by train, where they were met by Germans who shouted out orders:

The Germans pushed and hit us viciously, lining us up in rows and rushing us forward, pounding and yelling ... Two German women held my hands and legs while a third was searching my private areas to see if I was hiding something; then another moment to sit on a wooden chair while a man was cutting my hair and shaving my head. Then horrific screams, “Raus! Schnell!” ... Whipping and pounding descended on those of us who failed to dress up quickly ... “Schnell! Schnell!” the well-known German efficiency*save every second ... (Boulder, 1963, pp. 56)

The narrator, to be sure, is a French girl who recounts her vicissitudes in a women’s camp: her forced labor in a German factory, her scuffles with the wicked Blokova, her incessant hunger, her brief affair with a Czech girl, and her eventual liberation and homecoming. Here, a testimonial narrative of captivity, the likes of which were heard repeatedly during the months of the trial, is laced up with voyeurism of the inside of women’s camp, melodrama of misery, and sexual innuendoes. Yet, the story also mentions the fate of the Jews, rumors about extermination camps and an even greater Nazi cruelty outside the Stalag. Indirect references to the Jewish tragedy recur in other titles as well, but always remain external to the main story, as if indeed transpiring on another planet of which only fragments of information are available.

Still another intrusion of reality into fantasy is occasioned by some exceptional digressions*pseudo-philosophical rumination*on the nature of Nazism:

Something was wrong with the German system. According to its rule a woman was allowed to rape a man just because she was an SS soldier and he would then be executed merely for being raped. Something was totally wrong with the German system that allowed people to do whatever they fancied in utter disregard to any moral code and any precedent. To kill, to murder*in fire, lead, gas, iron rods, in poison and suffocation, to burn, shatter, obliterate, destroy, annihilate, so as to establish a new empire on an ocean of blood and dead limbs.... (Baden, 1961, pp. 133134)

This excursion into the metaphysics of Nazi criminality comes in a scene where a British pilot is beaten and tortured mercilessly for impregnating a Nazi guard. It seems to appear almost out of nowhere, as an ominous voice interjecting into the text, intruding as if to append the text with the underlying rationale of Nazi perversion. Thus the trial and the atrocities recalled found their way into the pulp, albeit in a fractured, displaced manner. It is as if the trial returned to haunt its fictional counterpart; and the more far-fetched the pulp, the more conspicuous are the quotations of fact within fiction.

In sum, the Stalags*in their capacity as the fantasy companion to the trial* exhibit three levels of correspondence with the trial and the collective trauma it evoked: as heroic contra-narrative to the story of destruction; as speculation on the inner working of Nazi mentality; and as intrusion of reality into fantasy. What was made explicit in the trial*the Holocaust*was implicit in the pulp; and vice versa: The enigma of Nazism, which remained pending throughout the trial, is the main subject matter of the pulp. Given the above, this pulp presents a special challenge to recent speculations on Holocaust memory, such as Hirsch’s (1996) notion of postmemory. According to Hirsch, postmemory is the process by which the trauma of the previous generation is mediated, belatedly, through the narratives and memories of the next. Yet, as a transgenerational space of remembering linked specifically to cultural or collective trauma, “its object or source is mediated not through recollection but through imaginative investment and creation” (p. 662). If the past remains mostly untold, as in the case of second generation to Holocaust survivors, postmemory may take even more creative liberties. The Stalags represent a rather different situation of second-generation narratives. They do not appear belatedly but run parallel to, and in some respect even precede, the narrative of the first. In this case, fantasy anticipates rather than proceeds from survivors’ fragmented narratives. Rather than a product of postmemory, fantasy here is an expression of protomemory*a precursor to Holocaust memory, or better, its primal scene. Similarly, Hartman (2000) notes the diffusion of Holocaust imagery into popular culture texts, such as the migration of key phrases from a videotaped testimony to a Harold Pinter play. Hartman points to how Holocaust memory affectively influences a wider public in contemporary visual culture. Not only do the Stalags long predate the diffusion Hartman identifies with millennial hyperreality, but they also present a case where Holocaust memory impacts affectively even before being established as such.

The Drama of Power and Identity

The eroticism of the Stalag does not revolve around the act of sexual intercourse, let alone its depiction. What constitute the erotic core are various acts of dominance, humiliation and servitude*in short, practices of sadomasochism (henceforth S/M).[17] Why did S/M resonate with so many young readers during and after Eichmann’s trial? Answering this question reveals that beyond the thrill of the sexually illicit, the pulp may have also related to other, more profound concerns in Israeli society at the time. We argue that the Stalags constituted a text upon which Israeli youth negotiated issues of power and identity vis-a‘-vis both their parents’ generation and Zionist ideology. On this reading, the S/M configuration served as a platform for reworking conflicting tendencies within Israeli identity politics heightened by the Eichmann trial.

A few prefatory notes on S/M are important. First, S/M is not properly an act of violence, sexual or otherwise. Rather, it is an act of staging violence, performance of a game that draws on social stereotypes for the sake of sexual pleasure. Krafft-Ebing (1998) and Freud (1961) posited sadism and masochism as opposite yet interrelated psychopathologies of male and female sexuality, respectively. Freud already speculated on the playful nature of these pathologies, but it was Reik (1941) who first separated masochism from sexual violence and presented it as an erotic role-play for producing fantasies of power and powerlessness. Reik’s realization opened the way to regard S/M as an arena for negotiating questions of power, gender, and identity through the pleasurable performance of sexual fantasies. Subsequent accounts develop the idea of S/M as a dramatization of the intersection of sexuality and power through the excessive use of social codes (Deleuze, 1991; Mansfield, 1997; Noyes, 1997; Savran, 1997; Silverman, 1992).

While the performance of S/M entails reiterating the stereotypes and social codes it borrows, its aim is in fact subversion. By the staging of power, S/M recasts power precisely as staged, rather than natural or inborn. As McClintock (1993) contends, S/M performs social power as scripted power and hence as permanently subject to change. Its economy is one of conversion: strong to weak, male to female, pain to pleasure, adult to baby, slave to master, and back again. In refusing to regard power as fate or destiny, S/M stages a theatrical exercise in social contradiction, consciously aimed at problematizing notions of natural law and orthodox power. In McClintock’s words, “S/M performs social power as both contingent and constitutive, as sanctioned neither by fate or God, but by social convention and invention, and thus open to historical change” (p. 210). What is played out through S/M is the subversion, rather than the affirmation, of socially codified power. This occurs by dramatizing moments and situations where power is rendered most visible.

In this respect, S/M may be a strategy for negotiating the fragmentary nature of social identities and the contradictory imperatives they prescribe, particularly during trying times of change. S/M makes social identities commutable, and their boundaries open to improvisation and transformation. This was also observed by Fanon (1967) who, as a practicing psychiatrist in colonial Algeria, saw how white men were seeking submissive relationship with black natives. He ascribed this to a contradictory injunction of French soldiers to implement colonial rule and show “sadistic aggression toward the black man,” but do so when such behavior would have been chastised by the democratic culture of their homeland (p. 167). The practice of S/M allowed them to negotiate this double-bind, flirting with issues of racial power and colonial control through erotic investment and pleasure. More recently, Noyes (1998) reports an increase in the visibility of S/M scenes and imagery in mainstream South African culture. This does not necessarily indicate further violence in post-apartheid South Africa, but rather a “form of metacommunication about sexuality and power,” which occasions new ways to “negotiate the production of subjectivity within the violent social network of subjectifying forces” (pp. 147, 151). In such instances the cultural practice of S/M serves as a response to and a way to deal with socially coded power relations.[18]

To what aspects in Israel of the early 1960s did the Stalags respond? What signs of power and identity did they borrow from and subvert? What contradictory injection did they make manifest? We contend that the Stalags bear witness to and dramatize a defining moment in the story of identity formation in Israel. What they reenacted was a social drama at the heart of Zionist ideology: the confrontation between the new Israeli Jew and the old Diaspora Jew, as it emerged against the background of the Eichmann trial.

An important part of Zionist ideology was the attempt to construct a new national Jewish identity in stark opposition to the old Jewish Diaspora identity. The new Jew*the native Israeli, or Sabra*was deemed strong, courageous, and masculine, capable of defending his land and his people*the complete antithesis of the old Diaspora Jew, who was deemed weak, servile, cowardly and feminine. In many respects, contempt for the Diaspora and all it represented was one of the constitutive elements of the Zionist subject (Almog, 2000; Loshitzky, 2002; Shapira, 1992; Zertal, 1998; Zerubavel, 1995). Encounters with Holocaust survivors, who began to arrive in Israel in the late 1940s, further accentuated the difference between new and old Jews. In Israeli eyes, the Sabra was the self-confident pioneer who fought and withstood the Arab enemies, while the Diaspora Jew was the helpless victim who was led “like sheep to the slaughter.” Hence the veneration held by Zionist ideology for individual feats of Jewish heroism and resistance during the war, such as the Warsaw ghetto uprising and the mission of Hannah Senesh. The first generation of native Israelis “grew up under the soothing images of heroic partisans, not under the sign of ‘the other planet’” (Feldman, 1992, p. 233). Israel in its first decade was oriented towards realizing the national project rather than tending to the recently suffered tragedy.

Much of this changed with the Eichmann trial. Only then did Israelis confront the Holocaust and its survivors, pointblank. Scores of testimonies at the trial revealed the catastrophe from survivors’ perspective, for the first time giving them voice within the Israeli public sphere. This had a particularly strong impact on the young generation, previously schooled in the Zionist unidimensional view of the Holocaust. The trial awakened Jewish awareness in the young generation, perhaps “the only thing whose beginning is actually rooted in the Eichmann trial” (Yablonka, 2004, p. 252). The encounter with personal stories of those who were “there” presented young Israelis with intimate knowledge of destruction, as well as new figures, hitherto nameless and voiceless, with whom they could now empathize. This process brought ambiguity and complexity to a social mindset dominated until then by conviction and rigidity. In this sense, chief prosecutor Hausner’s recurring question to the witnesses “Why didn’t you resist?” resonated with the inner discourse of the young. Now another question arose for them: What would we have done had we been there? How would we, the strong, have behaved in the place of the weak? Herein is the contradictory injunction set before Israel’s young generation: on the one hand, seeing themselves as fulfilling the ideology of the new Jew, yet finding themselves identifying with the survivors and their stories, namely, with the epitome of the Diasporic Jew. A transformative process was set in motion whereby the definitions of what it means to be strong and what it means to be weak began to complexify. The Stalags were an agent in negotiating this process.

The Stalags can be read as a fictional narrative situating the new Jew in the place of the old, thereby staging the contradiction between the native Israelis and the survivors’ generation. Seen against the gendered metaphors of Israeli identity politics of that period, scenes of women dominating men and the constant reversal of weak and strong suggest the social roles they dramatized. The Stalags offered a singularly compact repository for rehearsing the question of “what would we have done in their place,” using the fictional camp as a displaced arena for the role-play. Through the erotization of power relations, captivity was no longer about servile Jews assailed by Nazi perpetrators but about virile Allied soldiers sexually abused by Aryan women. Servitude and powerlessness were thus dissociated from victimhood and infused with pleasurable, exciting potential. S/M scenarios presented readers with an erotic parable of power and loss of power, a master-slave fantasy with Nazi brutality as its theme.

More profoundly, the Stalags can be read as reenacting the drama buried under the Zionist disavowal of the Diaspora. Here the encounter between the new masculine Jew and the old effeminate Jew is no longer of one generation facing the other, but a confrontation at the heart of Jewish identity in post-Holocaust Israel. S/M rituals are often about recalling a forbidden childhood memory (McClintock, 1993). In female domination (Fem-Dom) S/M, what is evoked is the early identification with the culture of femininity, the infant’s first structuring principle. Later, children are tasked with identifying away from women, the founding dimension of their personality, toward an abstracted model of masculinity, one that comes into being not through recognition but through negation of the feminine. But the culture of women survives in secret tabooed rituals, where “male ‘slaves’ enact with compulsive repetition the forbidden knowledge of the power of women” (p. 213). In this sense Fem-Dom fantasies are to be understood as a way of furtively recalling the memory of maternity and relishing in forbidden femininity. Here is the parallel to the construction of the new Jew in Israel: the new Jew was also tasked with identifying away from his roots toward a distant and abstract model of identity, which was similarly predicated on a ritualized disavowal of a socially banished past. The new Jew was to emerge masculine, virile and strong while discarding all past feminine affinities associated with the historical figure of the old Jew. To the extent that these two models are comparable, the Stalags document the internal split of identity through its erotization. It is as if at the depth of the new Jew lurked the buried memory of the old Jew, which expressed itself partly as an obsession to be dominated and humiliated, forced back into submission by beautiful yet cruel women, only to be resurrected as powerful.

Finally, the Stalags can be read as reenacting yet another drama, that of the right to punish. Bringing Eichmann to trial was premised on the moral stance that historical justice is accomplished through a public legal procedure, leading eventually to sentencing and punishment. The Stalags, on the other hand, maintain that when it comes to Nazi criminals, historical justice means revenge. Thus if the trial displayed a regulated and disciplined response to atrocity, the Stalags expressed an unmitigated, visceral desire for vengeance. Their version of justice recalls pre-modern methods of retribution, as opposed to the legal manifestation of jurisprudence and due process of law.[19] Here, too, S/M flouts the reality upon which it draws. As McClintock (1993) points out, the scandal of S/M is that it borrows directly from the modern judicial model while radically rearranging the right to punish*taking it not as a preventative or corrective measure but as a source for excessive pleasure. The scandal of the Stalags was in borrowing from the Eichmann trial while reversing the legal course of action* performing the right to punish as the pleasure of revenge. The pulp made manifest what was consistently rejected in the trial*that punishment is inseparable from the economy of pleasure. Hence, the revenge denied from the survivors and deferred by the court was taken up by the pulp and dramatized to a fault. The right to judge and punish now made available to Jews in Israel marked the ascendancy of the new generation and underscored the incapacity suffered by the previous. In this sense, the Stalags can be read as an allegory of recent history: they repetitively act out the pleasure of coming to power after experiencing its complete loss. A primordial desire for reprisal found fictional expression, as pronounced by a prisoner in one Stalag, quoting Deuteronomy: “To me belongeth vengeance and recompense” (Rosenberg, 1963, p. 115).

First beginnings are almost always both childish and mythical. Like initial linguistic articulations or sexual explorations, they often seem awkward and embarrassing in retrospect. The Stalags testify to the nascent Holocaust consciousness among the Israeli young generation: early articulations of things previously unspoken*new speech for sex and at the same time new speech for trauma. The Stalags manifest the lived and felt aspects of a transformative period in the history of Israel*the “structure of feeling” of a generation’s coming to power, coming to terms, and coming to puberty. As a specimen of popular culture employing elements of Israeli identity politics at the time, they document how the untold trauma of the first generation weaved itself into the imagination of the second. As such the Stalags demonstrate a fantasy construction that bespeaks trauma, a stuttering of the Holocaust on the threshold of its articulation.

References

Almog, O. (2000). The Sabra: the creation of the new Jew (H. Watzman, Trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Baden, M. (1961). Stalag 13. Tel Aviv: Yam Suf.

Bartov, O. (2000). Mirrors of destruction: war, genocide, and modern identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ben-Ari, N. (2006). Suppression of the erotic in modern Hebrew literature. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Boulder, V. (1961). Stalag 217. Tel Aviv: Yam Suf.

Boulder, V. (1963). Stalag 33. Tel Aviv: Narkis.

Brand, Y. (1961, April 19). Shtei pgishot im Eichmann [Two meetings with Eichmann]. Yediot Acharonot, p. 4.

Brown, D. P. (1996). The beautiful beast: the life & crimes of SS-Aufseherin Irma Grese. Ventura, CA: Golden West Historical Publications.

Conot, R. E. (1984). Justice at Nuremberg. New York: Harper & Row.

Dawidowicz, L. S. (1977). The Jewish presence: Essays on identity and history. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Deleuze, G., & Sacher-Masoch, L. (1991). Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty & Venus in Furs (J. McNeil, Trans.). New York: Zone Books.

Deutsch, A. W. (1974). The Eichmann trial in the eyes of Israeli youngsters: opinions attitudes, and impact. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University.

Douglas, L. (1998). The shrunken head of Buchenwald: Icons of atrocity at Nuremberg.

Representations, 63, 3964.

Du Pont, O. (2005). Robert Graves’s Claudian novels: A case of pseudotranslation. Target: International Journal on Translation Studies, 17, 327347.

Elgat, Z. (1964). Hageografia shel hapornografia [The geography of Pornography]. (1964, May 18). Maariv, p. 3.

Eshed, E. (2002). From Tarzan to Zbeng: The Story of Israeli Pop Fiction. Tel Aviv: Bavel.

Fanon, F. (1967). Black skin, white masks (C. Farrington, Trans.). New York: Grove Press.

Feldman, Y. S. (1992). Whose story is it, anyway?: Ideology and psychology in the representation of the Shoah in Israeli literature. In S. Friedlander (Ed.), Probing the limits of representation: Nazism and the Final Solution (pp. 223239). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Felman, S. (2002). The juridical unconscious: Trials and traumas in the twentieth century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Freud, S. (1961). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 19 (J. Strachey, Trans.). London: Hogarth Press.

Friedlander, S. (1984). Reflections of Nazism: An essay on kitsch and death. New York: Harper & Row.

Frost, L. C. (2002). Sex drives: Fantasies of fascism in literary modernism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Geuens, J. P. (1996). Pornography and the Holocaust: The last transgression. Film Criticism, 20, 114130.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Goldstein, D. (1963, December 20). Ha’dochanim meleim ve’hachok hasar onim [Newsstands full and the law helpless]. Maariv, p. 8.

Gouri, H. (2004). Facing the glass booth: The Jerusalem trial of Adolf Eichmann (A. Mintz, Trans.). Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Harris, O. (2003). Film noir fascination: Outside history, but historically so. Cinema Journal, 43, 324.

Hartman, G. H. (2000). Memory.com: Tele-suffering and testimony in the dot com era. Raritan, 19, 118.

Harvey, S. (1998). Women’s place: The absent family of film noir. In E. A. Kaplan (Ed.), Women in film noir (pp. 2234). London: British Film Institute.

Hausner, G. (1966). Justice in Jerusalem. New York: Harper & Row.

Herzog, D. (2005). Sex after fascism: Memory and morality in twentieth-century Germany. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hirsch, M. (1996). Past lives: Postmemories in exile. Poetics Today, 17, 659686.

Krafft-Ebing, R. v.(1998). Psychopathia sexualis: with especial reference to the antipathic sexual instinct: a medico-forensic study (F. S. Klaf, Trans.). New York: Arcade Pub.

Longshot, M. (1962). Murder in the Stalag. Tel Aviv: Yam Suf.

Loshitzky, Y. (2002). Identity politics on the Israeli screen. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Mansfield, N. (1997). Masochism: The art of power. Westport, CT: Praeger.

McClintock, A. (1993). Maid to order: Commercial S/M and gender power. In P. Church Gibson & R. Gibson (Eds.), Dirty looks: Women, pornography, power (pp. 207231). London: British Film Institute.

Mizejewski, L. (1992). Divine decadence: Fascism, female spectacle, and the makings of Sally Bowles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Noyes, J. K. (1997). The mastery of submission: Inventions of masochism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Noyes, J. K. (1998). S/M in SA: Sexual violence, simulated sex and psychoanalytic theory. American

Imago, 55, 135153.

Parfrey, A. (2003). It’s a man’s world: Men’s adventure magazines: the postwar pulps. Los Angeles, CA: Feral House.

Pinchevski, A., Liebes, T., & Herman, O. (2007). Eichmann on the air: Radio and the making of an historic trial. The Historical Journal of Film. Radio and Television, 27, 126.

Rapaport, L. (2003). Holocaust pornography: Profaning the sacred in Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS.

Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, 22, 5379.

Reik, T. (1941). Masochism in modern man. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

Rosenberg, M. (1963). Haiiti mefaked Stalag [I was a Stalag commander]. Tel Aviv: Yam Suf.

Rosenfeld, A. H. (1985). Imagining Hitler. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Rosenne, S. (Ed.). (1961). 6,000,000 accusers: Israel’s case against Eichmann: the opening speech and legal argument of Mr. Gideon Hausner, Attorney-General. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Post.

Savran, D. (1998). Taking it like a man: White masculinity, masochism, and contemporary American culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Segev, T. (2000). The seventh million: The Israelis and the Holocaust. New York: Henry Holt.

Shamir, A. (1963, May 31). Hava nisrof sfarim (Let us burn books). Yediot Aharonot, p. 5.

Shapira, A. (1992). Land and power: The Zionist resort to force, 18811948. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shapira, A. (2005). The Eichmann trial: Changing perspectives. In D. Cesarani (Ed.), After Eichmann: Collective memory and the Holocaust since 1961 (pp. 1839). London: Routlegde.

Silverman, K. (1992). Male subjectivity at the margins. New York: Routledge.

Smith, J. (1991). Misogynies: Reflections on myths and malice. New York: Fawcett Columbine.

Sontag, S. (1980). Under the sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

The Attorney General against Adolf Eichmann, volume 4. (1962). Psak hadin [The verdict].

Jerusalem: Information Center at the Prime Minister’s Office.

Tshuka ushma stalagim [Passion named Stalags]. (1962). Ha’olam Ha’ze, 1289, 1214.

Tazhal yatza lemilhama bastalagim haklokelim [IDF wedges war on indecent Stalags]. (1964, September 24). Yediot Aharonot, p. 2.

Uebel, M. (2002). Masochism in America. American Literary History, 14, 389411.

Yablonka, H. (2004). The State of Israel vs. Adolf Eichmann. New York: Schocken Books.

Zertal, I. (1998). From catastrophe to power: Holocaust survivors and the emergence of Israel. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Zertal, I. (2005). Israel’s Holocaust and the politics of nationhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zerubavel, Y. (1995). Recovered roots: Collective memory and the making of Israeli national tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Amit Pinchevski is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Journalism at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Contact information: Amit Pinchevski, Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Mount Scopus, Jerusalem 91905, Israel. E-mail: amitpi@mscc.huji.ac.il.

Roy Brand is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Sarah Lawrence College, New York. Contact information: Roy Brand, Sarah Lawrence College, 1 Mead Way, Bronxville, NY 10708, USA. Email: rbrand@slc.edu.

The authors wish to thank Tally Gross for her research assistance, as well as Daniel Dayan and Linda Steiner for thoughtful comments on this paper, which was presented at the International Communication Association, 2007. Correspondence: Amit Pinchevski

ISSN 1529–5036 (print)/ISSN 1479–5809 (online) # 2007 National Communication Association

DOI: 10.1080/07393180701694598

[1] Films conflating Nazism and sexual perversions include Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) and Luchino Visconti’s The Dammed (1969). Cultural links between Nazism and sexuality are explored by Dawidowicz (1977), Frost (2002), Herzog (2005), Mizejewski (1992), Rosenfeld (1985), and Smith (1991).

[2] Pseudo-translations are common with texts that transgress existing norms, because “foreign” texts are usually granted more latitude than local (Du Pont, 2005). One author’s actual identity was revealed in a 1962 expose´ when 23-year-old Eli Keydar declared himself as the writer of Stalag 13. Having experience in pulp writing, he began working on the story equipped with high school textbooks for historical background (Tshuka ushma stalagim, 1962). Another name behind several pseudonyms is Uriel Meyron, a long-time writer of detective and adventure stories, who, according to the publisher, had broad historical knowledge and could produce a text within hours of demand (personal communication with publisher Ezra Narkis, January 2007).

[3] Unless otherwise indicated, all citations are translated from Hebrew by the authors.

[4] Numbers are taken from a magazine article (Tshuka ushma stalagim, 1962). The publisher of the first Stalags was Ezra Narkis, who had specialized in men’s magazines and pornographic pulp. Narkis accepted the manuscript of Stalag 13 from Eli Keydar after no other publisher even considered it. According to him, Stalag 13 sold in total nearly 70,000 copies (personal communication Narkis, January 2007). One account claims that producers of the 1965 Hogan’s Heroes heard about the book’s success while visiting in Israel and decided to adopt it for their American TV series, which also took place in Stalag 13 (Eshed, 2002).

[5] The catalogue of The Jewish National & University Library in Jerusalem lists about 80 titles that can be considered Stalags. One or two appeared in 1961, two-thirds appeared in 1963, and one title was published in 1965. The rapid decline was probably due to the torrent of Stalags from different publishers following the genre’s initial success. Narkis said he deliberately flooded the market with cheap, substandard titles in order to fight his competitors, which forced publishers to seek new formats (personal communication Narkis, January 2007). Risk of prosecution was also a factor, especially after a 1963 court case finding one publisher guilty of printing obscenities.

[6] Ilsa Koch, wife the commander of Buchenwald, was notorious for collecting specimens of human tattoos and fashioning lampshades from prisoners’ skins (Conot, 1984; Douglas, 1998). Koch was probably the inspiration for the 1974 B-movie Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS. Coincidentally enough, this movie was filmed on the Stalag 13 set of Hogan’s Heroes (Geuens, 1996; Rapaport, 2003). Irma Grese, “the Beautiful Beast,” the second-highest ranking women officer at Auschwitz (and also Josef Mengale’s mistress), was reputed to have beaten, tortured, and sexually abused inmates; she was sentenced to death in 1945 for these crimes (Brown, 1996).

[7] In matters relating to moral conduct, Israeli law at the time was based on the British law, which banned publication and distribution of obscenities; maximum punishment was 3 months’ imprisonment. Its exercise was, however, rare, as it collided with issues of freedom of speech and entailed technical problems of cataloguing and evaluating printed material.

[8] The issue was finally brought to the Knesset by members of the religious parties, who tried but failed to change the existing censorship policy. The Israeli army was more proactive: its Senior Education Officer resolved “to fight the enemy in its own camp” and publish cheap, short paperbacks with some of the attributes of the competition*but without the seductive characteristics; but these could hardly compete with the pulp’s allure (Tazhal yatza lemilhama, September 1964).

[9] Various rumors spread about the identity of this Stalag’s author: some said it was written by a literature professor and two of his female students. It was in fact a collective product: the idea came from an aspiring young author who heard a similar story from a woman in France; most of the writing was by a philosophy and literature student in her twenties, who declared she merely wrote down what had been running in her head; the final draft was probably completed by Eli Keydar, the author of Stalag 13 (Ben-Ari, 2006; Eshed, 2002; Tshuka ushma stalagim, 1962).

[10] Among these were: Male, Real, True, War Story, War Criminals, Man’s Adventure, All Man, Man’s Story, Man’s Epic, Man’s Action, Men in Conflict, Man to Man, Man’s Best, Real Man, Man’s Daring, True Men Stories, Daring, World of Men, Man’s Book (see Parfrey, 2003).

[11] Narkis says that after the success of Stalags 13, he showed another author, Uriel Meyron, short stories and illustrations from American “torture magazines,” urging him to write along the same lines. Keydar remembers meeting a publisher who gave him a copy of MALE magazine with a picture of two women torturing a man, saying “this would make a good topic” (Tshuka ushma stalagim, 1962, p. 14).

[12] The different formats reflect the cultural preferences of readerships. In Israel, the prevalence of text-based pulp was a combination of publishers’ interest in low-cost products and the readers’ preference towards a small and relatively inconspicuous pulp, which could easily be passed from hand to hand and read surreptitiously.

[13] Abbreviation of Konzentrationslager, German for concentration camp prisoner.

[14] Admitting he has no evidence of this, Bartov (2000) suspects that the Stalags were mostly read by boys, whereas girls just as often read Ka-tzetnik.

[15] Replicating elements of the femme fatale of 1950s American film noir, these animalistic metaphors also reveal a version of the virgin/whore dichotomy, between the Nazi-animal woman, who is tougher and crueler than any man, and the angelic-pure women, usually the resistance fighter or the girl back home, who remains celibate, absent or otherwise unattainable. See Harris (2003) and Harvey (1998).

[16] In a short commentary about his encounter with Eichmann in Jerusalem, Yoel Brand, a key witness who had negotiated with Eichmann for the release of Hungarian Jews in 1944, wrote: “Now I heard from his mouth only one word: ‘Jawohl’ with the same sniping, ordering sound as before” (Brand, 1961, p. 4). Haim Gouri (2004) remarks that since Eichmann’s responses were often verbose and roundabout, his “Jawohl” brought some relief to the audience and the judges.

[17] We use S/M (Alfred Kinsey’s neologism) broadly to denote various practices of submission and domination organized as a sexual game. This is different than the more traditional “sadomasochism” denoting a sexual pathology. As Deleuze (1991) affirms, sadism and masochism do not constitute a conceptual opposition but are two distinctive practices.

[18] Arguably, practicing S/M is not the same as reading erotic literature about it. Indeed, firsthand experience should not be confused with the vicarious. Yet, when considering S/M as a cultural practice such distinctions are somewhat arbitrary; for this practice is predicated on the interlacing, rather than the separating, of reality and fiction, body and text. Thanks to de Sade and Sacher-Masoch, S/M has its roots in literature, and may fairly be said to be itself a form of literature*a way to cast, direct and narrate a world of make-believe. Moreover, S/M is never simply an idiosyncratic imaginaire but a fantasy construction of fiction, imagination and narrative, all of which are inexorably linked with social life and culture*with history, politics, art, literature, cinema, and theatre. See Deleuze (1991) and Mansfield (1997).

[19] These two versions of punishment are analogous to what Foucault (1977) designates as sovereign punishment, performed through the spectacle of torture and execution, and penal reform, the rationally administered procedure of civic prevention and protection of society.