How to Cite: Whitehead, A., & Letcher, A. (2023). ‘We’ll All Dance each Springtime with Jack-in-the-Green’: The ‘Green Man Complex’ in Contemporary British Culture. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, 17(2), 228–252. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.20463

Author Contact: Amy Whitehead, Massey University Auckland, Private Bag 102904, Auckland 0745, New Zealand. A.R.Whitehead@massey.ac.nz

Andy Letcher, Schumacher College, Dartington Hall, Totnes, Devon, United Kingdom TQ9 6EA. andy.letcher@schumachercollege.org.uk

Print ISSN: 1749-4907.

Online ISSN: 1749-4915

Submitted: 2021-09-15

Accepted: 2022-10-19

For information regarding the journal's Open Access policy, click here.

Amy Whitehead & Andy Letcher

‘We’ll All Dance each Springtime with Jack-in-the-Green’

The ‘Green Man Complex’ in Contemporary British Culture

Three Tendencies of the Green Man Complex in Contemporary Culture

Festivals, Processions, and the Green Man

Resistance and Re-territorialization: Mobilizing the Green Man

Costuming and Performance: Re-thinking the ‘Symbol’ with the Green Man

Abstract

The Green Man is a familiar image in British popular culture who is celebrated in a variety of ways, not least in an ever-growing number of festive processions in towns, villages, and cities, particularly around Beltane (May Day). Combining two scholarly voices, this article offers a survey of the Green Man image and related ritual phenomena in what we refer to as the ‘Green Man complex’. Here we address the Green Man’s role in what could be the mobilization of responses to the current ecological crisis, as well as his relationship to growing trends in dark green religion. Last, we turn our attention to the theoretical innovations that current Green Man phenomena invites: more than ‘symbolic’ or ‘representational’, the Green Man is a source for contemporary Pagan ritual religious creativity that is being used in animistic, embodied, territorializing, and reciprocal fashions to direct human attention toward the other-than-human vegetable kingdom.

Keywords

Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Paganism, Animism, ritual, costuming, procession, territorializing, magic

Introduction

The Green Man is a familiar image in British popular culture and also elsewhere. He is to be found on postcards, trinkets, garden ornaments, clothing, in Pagan[2] literature, art, and ephemera, and in hundreds of thousands of Instagram posts. He is celebrated in many newly composed folk songs, and every year more towns, villages, cities, and festivals host Green Man or Jack-in-the-Green processions, especially around May Day. Meanings and performances vary from person to person, place to place, but the image of the Green Man popularly conjures all things green, ancient, Pagan and atavistic, despite the best efforts of historians, for whom he is none of these. Nonetheless, he is proving active, agentic, and relevant at this moment of unprecedented ecological crisis.

Combining the voices of two scholars who share an appreciation for the history and present of the Green Man this article offers a survey of the Green Man image and related ritual phenomena as they are manifesting primarily in Britain. In conversation with what we refer to as the ‘Green Man complex’, we examine, among other tendencies, the ritualized, embodied performances that continue to gain momentum and grow in popularity in the UK. Significantly, we address the Green Man’s role in what could be the mobilization of responses to the current ecological crisis, his relationship to growing trends in dark green religion (Taylor 2010a; 2016a), and his role as providing a figure of ‘healthy masculinity’ for many Pagans. Last, we turn our attention to the theoretical innovations that current Green Man phenomena invites. More than ‘symbolic’ or ‘representational’, the Green Man is being used in animistic, embodied, territorializing, and reciprocal fashions to direct human attention toward the other-than-human Plant Kingdom.

Context

We begin by introducing the ‘Green Man’ and the ‘Jack-in-the-Green’. The Green Man, or foliate head, is a figurative carving depicting a human face, typically male, surrounded by leaves or spewing foliage from the mouth, nose, eyes or ears. It is found in European medieval churches although earlier examples have been found from the Romanesque period (Basford 1978), as are similar figures in India (Harding 1998). Despite furious speculation (see Matthews 1993; Harding 1998; Doel and Doel 2001; MacDermott 2003), its original meaning remains obscure. The folklorist Lady Raglan (d. 1940) identified the phenomenon and gave the Green Man his name in 1939. She linked it with other figures from British folklore and legend, such as Robin Hood, the Green Knight from the medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and most especially the Jack-in-the-Green (Lady Raglan 1939).

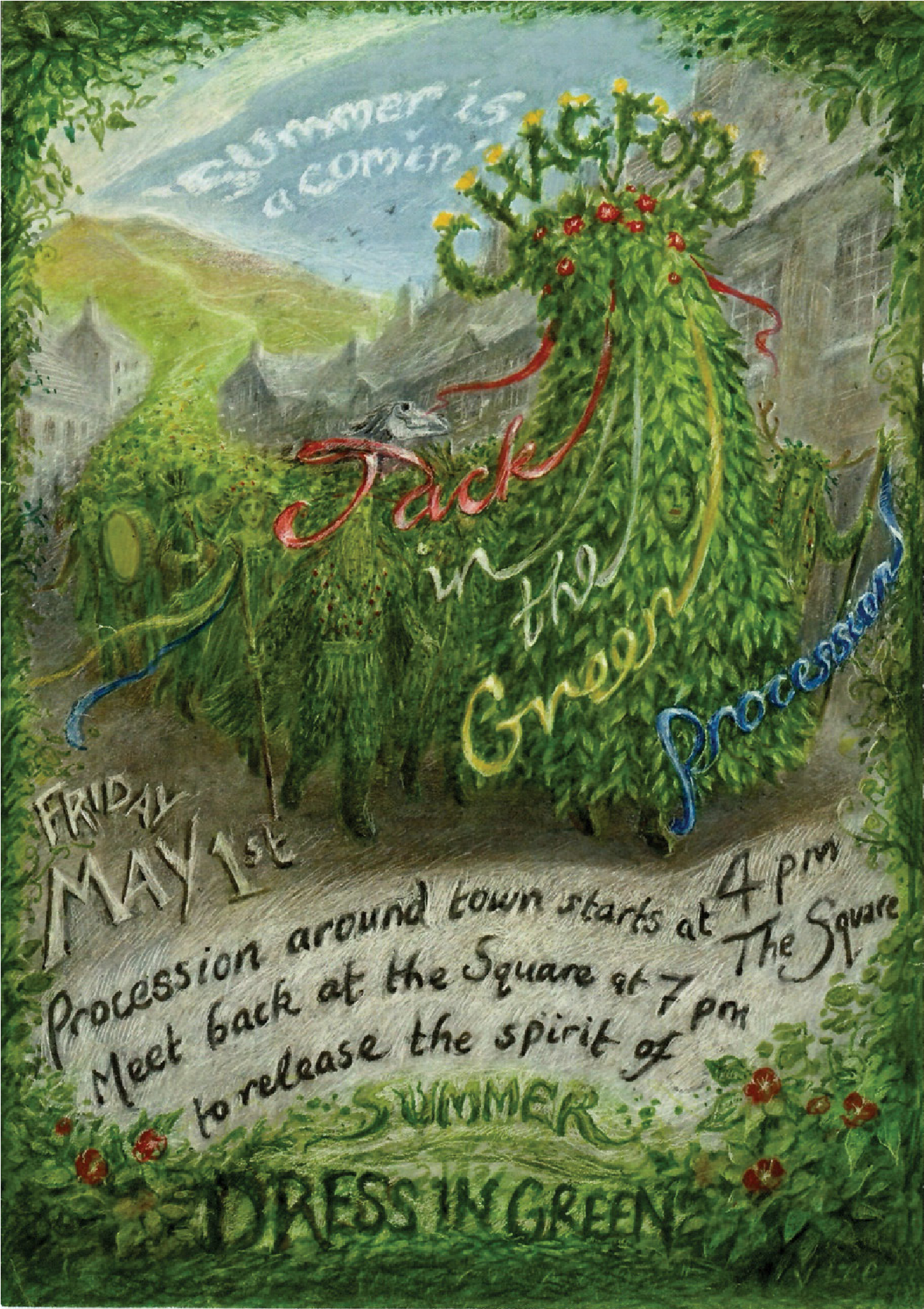

The Jack-in-the-Green is a human-sized, cone-shaped puppet placed over the bearer such that only their legs are visible. It is made from a wicker frame that has been festooned with greenery, often topped with a garlanded crown and sometimes sporting a Green Man mask (see Figure 1). Jacks are typically paraded through the streets of British towns and cities, and at festivals, as part of traditional, vernacular May time celebrations. They are often accompanied by ludic attendants known as bogies or whifflers – who may also be dressed in tattered green costumes, with green face paint or sporting Green Man masks –, as well as by folk musicians and Morris dancers.[3]

Although inaccurate from an historical point of view (described below) both the Green Man and the Jack-in-the-Green are popularly regarded as having something to do with a vaguely remembered preChristian, pagan past.[4] To understand the popularity of this Green Man complex in Britain today it is first necessary therefore to know how it became entangled with an idea of paganism.

The word pagan has its origins in late Antiquity, where the Latin term paganus referred to a civilian, that is ‘a person not enrolled in the Christian army of God’ (Hutton 1999: 4). An abject term, the original meaning drifted to mean ‘rustic’, and was hence set up in binary opposition to the civilized and the Christian. Now, it has come to refer not only to the manyfold spiritualities and worldviews of Europe that predated Christianity (about which evidence is scant), suggesting and supporting multiple, sometimes contradictory interpretations (see Hutton 1993; 2013), but also to the modern Pagan spiritualities of Wicca, Druidry, Asatru and so on, all largely revived, recreated, or reimagined since the end of the Second World War (Harvey 1997; Hutton 1999; Davy 2007). Some scholars therefore prefer to speak of a plurality of paganisms (Blain et al. 2004).

Early British anthropologists, Edward B. Tylor (1832–1917) and Sir James George Frazer (1854–1941), certainly cast pre-Christian religiosity as both a singular, ubiquitous thing, and a troubling and problematic earlier stage of human cultural evolution (for a fuller exposition, see Hutton 1999; Letcher 2012). In particular, Frazer – writing in three, ever more voluminous, editions of The Golden Bough between 1890–1915 – argued that all religions were but later evolutionary developments of an original and universal cult of a dying and reborn vegetation god, and in which vestigial traces of the original faith could be carefully uncovered by discerning scholars (the thinly-veiled attack on Christianity should be obvious). Frazer’s paganism necessitated the maintenance of fertility through springtime and harvest rituals that were often, he suggested, lewd or licentious. Frazer supposed that to the primitive mind, magical ritual simulating or enacting sex would bestow fertility more generally by a kind of sympathy, or what he termed homeopathic magic. The capricious vegetation god also sometimes required propitiation with even more heinous acts, namely, human sacrifice. For Frazer’s considerable and enduring audience, therefore, the pagan origins of Western culture elicited strong feelings of ambivalence, being at once titillating and horrifying, with the fear that paganism might erupt atavistically at any moment (see Letcher 2012). Frazer wrote:

Yet we should deceive ourselves if we imagined that the belief in witchcraft is even now dead in the mass of people; on the contrary there is ample evidence to show that it only hibernates under the chilling influence of rationalism, and that it would start into active life if that influence were ever seriously relaxed. The truth seems to be that to this day the peasant remains a pagan at heart; his civilization is merely a thin veneer which the hard knocks of life soon abrade, exposing the solid core of paganism and savagery below. (Frazer 1913: viii–ix)

Frazer’s ideas were condemned by scholars at the time and they have been so roundly demolished by later scholars that they remain of historical interest, for the most part, only in Pagan Studies (see Hutton 1993; 1999; Letcher 2012). And yet precisely because of that ambivalence his cultural influence was and remains strong. To give but a few examples: Jane Ellen Harrison and the so-called Cambridge Ritualists looked for Frazer’s vegetation god in ancient Greek religion while Robert Graves mixed Frazerian ideas with his own inspired outpourings in his influential work, The White Goddess. A whole generation of Frazer-inspired scholars sought out the hidden traces of his vegetation cult in language, folk tales, medieval Romance, children’s games, folklore and folk customs. Most famously Egyptologist Margaret Murray suggested that the Early Modern witch trials had actually been the persecution of the ancient pagan faith that had somehow clung on, persisting in secret in spite of Christianity (Hutton 1999). In wider culture, The Golden Bough influenced Stravinsky’s The Rites of Spring, T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume, Marin Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, and Robin Hardy’s 1973 cult folk horror-film classic, The Wicker Man.

The Wicker Man is especially significant here and so merits greater attention. The story follows a sanctimonious, Presbyterian Police Officer, Sergeant Howie, who is called to the fictional Scottish island of Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of a young girl. There he discovers, to his increasing horror, that the locals are pagan and that they worship their ancient gods through a variety of folk customs and practices (including a Jack-in-the-Green). They also practice licentious acts of sympathetic magic (not least in the rooms of the island’s pub: ‘The Green Man’). Howie suspects the girl is to become a human sacrifice, so as to restore the fertility of the ailing apple harvest for which the island is renowned. The film expresses a number of Frazerian ideas: that peasant culture can easily ‘revert’ to paganism; that folk customs are of pagan provenance; that paganism was concerned especially with maintaining fertility through sympathetic magic; and that paganism often employed human sacrifice. Indeed Anthony Schaffer, who wrote the screenplay for The Wicker Man, derived much of the inspiration for the film directly from The Golden Bough (see Sermon 2006). The film has such a cult status (Brown 2000), and has subsequently been so influential (spawning a 2006 remake starring Nicholas Cage, two homages, The Wicker Tree in 2011 and Midsommar in 2019, an academic collection of essays (Franks et al. 2006), and even a rollercoaster ride at British theme park Alton Towers) that at the very least it seems one of the most common ways in which Frazerian notions remain in circulation.

Given this ongoing influence, it is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that in the post-war period people began consciously and explicitly to ‘revive’ the paganism Frazer sought so hard to decry minus, of course, the more unpleasant aspects such as human-sacrifice but still perhaps enjoying the frisson that such connotations provided (see Hutton 1999). Frazer’s anti-religious thesis inadvertently provided much of modern, revived Paganism with something like a theology, an assertion we will explore presently.

Such was Frazer’s influence upon 20th century thought that when, in 1939, Lady Raglan discovered and named the foliate heads of medieval churches as Green Men, she could only regard such a figure – and the others with whom she linked him, the Jack-in-the-Green, Robin Hood and so on – as expressions of the same impulse. Later scholars, however, have conclusively demonstrated that Lady Raglan’s thesis was inferential and unsupported with thin, if any evidence, concluding that it should be dismissed (Judge 2000; Hutton 1993; Roud 2006).

In 1979 Roy Judge (see Judge 2000) published his award-winning study of the Jack-in-the-Green, providing systematic evidence that it was not of ancient provenance nor connected to the medieval foliate heads. It was rather the invention of chimney sweeps in the eighteenth century, who used the spectacle as a way to collect money at a moment in the year when their work was drying up for the summer. In 1978, Kathleen Basford published the first academic study of the Green Man (Basford 1978). Though she traced the roots of the image back to the Romanesque period, she demonstrated that the highwater mark of the Green Man was the late Middle Ages, so long after the formal end of paganism in Britain as to make the pagan survivals thesis untenable. For Basford, the Green Man was not a happy figure but a grim and arresting Christian reminder of mortality, a visual admonition about the need to tend the soul against the weeds of sin.

Scholars then are agreed. There is no link between the image of the Green Man and the Jack-in-the-Green puppet, nor indeed with any other figures from British legend and literature such as Robin Hood and the Green Knight. Neither is there any plausible link between any of these and ancient pre-Christian paganism. There the matter should end, except that what scholarship has done so much to prune, hack back and cleave apart, has taken on a life of its own, remaining stubbornly entangled within the popular imagination. As folklorist Steve Roud opines:

[The Jack-in-the-Green] has also become inextricably tangled up in the complex modern persona of ‘the Green Man’, that powerful symbol used by the romantic wing of various eco-friendly and New Age groups. He has thus been absorbed into the amorphous blend of foliate heads (as the Green Man carvings in churches were previously called), medieval wildmen, Robin Hood, Gawain and the Green Knight, and anything or anyone else ‘green’, who are all now equated with vegetation and nature spirits. Needless to say, there is not the slightest evidence that Jack-in-the-Green has any connections with these other characters, but it is probably impossible now to rescue him from such dubious company. (Roud 2006: 156)

As scholars of religions, we take a more open approach here, for such dubious company remains the subject of our study. There may very well be no historical connection between the Green Man and the Jackin-the-Green but there is now, a modern grafting of two disparate figures that bears considerable cultural fruit. As it will be demonstrated further along, this fruit, carrying on the enduring influence of Frazer, is feeding into a plethora of ritual and religious creativity found in popular culture as well as currents in contemporary Paganisms, the latter of which, from a Study of Religions perspective, is just as religiously real and authentic as longstanding religious traditions. Consequently, we speak of a ‘Green Man complex’ in which all those figures decried by Roud meet, and most visibly on British streets and elsewhere at ever more exuberant springtime celebrations.

The Return of the Jack

Though once widespread across England, Jack-in-the-Green processions had almost universally died out by the opening of the 20th century; the lone exception was at Knutsford, which has continued its procession unbroken since 1890 (The Company of the Green Man n.d.). There was a revival in Brentham in 1920, and in Oxford in 1951 (by the Oxford University Morris Men) though for the most part the current popularity for processional Jacks began in the 1970s, when a number of social and cultural factors coincided.

Given impetus perhaps by the dismal economy, the 1970s saw a significant interest in folklore, folk customs, folk music (driven by a new wave of folk rock and acid folk bands, such as Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, Comus, Trees, and Mellow Candle), Morris dancing, home brewing, country living, and self-sufficiency, couched around the invocation of and desire to return to imagined rural Arcadias from the British past (see Young 2010). Contrastingly, this period also saw a trio of darker ‘folk-horror’ movies in which the more unsettling aspects of Frazer’s pagan past haunts these rural idylls: The Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and the aforementioned The Wicker Man (1973) (which features a cameo appearance of a Jack-in-the-Green).

In 1972, the British folk singer Martin Graebe wrote a song, ‘Jackin-the-Green’, that has been covered by several folk bands and has become the unofficial anthem of many contemporary May festivities and Jack processions (and from which we’ve drawn the title of this paper). Graebe’s Jack is evidently akin to Frazer’s vegetation spirit, who possesses the power to ripen the wheat in the fields and make young women’s bellies swell with a single touch: ‘Now Jack-in-theGreen is a very strange man/ Though he dies every winter he’s born every spring’ (Graebe 1972). The song is often regarded as being of ancient pagan provenance. Such beliefs have been to Graebe’s evident delight and amusement (Graebe pers. comm.).

Graebe’s was followed in 1977 by another song of the same name by the far better-known progressive rock band, Jethro Tull, on the album Songs From the Wood (Jethro Tull 1977). Penned by Ian Anderson, this is possibly the first ecological reading of the Green Man complex, with Jack, a diminutive, benevolent, velvet-clad nature spirit, pushing up plants through the tarmac in defiance of urbanised modernity.

Anderson is said to have been inspired to write the song after receiving a copy of the extremely popular and now much sought-after book, Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain, which was published in 1973 and again in 1977 by the Reader’s Digest Association. Featuring on its embossed cover a picture of a horned, grimacing mask – the Dorset Ooser, as used by Morris Men in that county to celebrate May Day – the book affirmed a Frazerian reading of May customs. ‘May Day rites, which have their origins in ancient fertility ceremonies, included the crowning of a May Queen, Morris dancing, traditional plays, and dancing round the maypole’ (Reader’s Digest 1977: 24). A picture of an historic, presumably 19th century, Jack-in-the-Green procession was explained as having once ‘represented the spirit of the green woodlands’ (Reader’s Digest 1977: 24).

In 1974, Lionel Bacon encouraged people to revive Morris traditions by publishing his now indispensable Handbook of Morris Dances (Bacon 1974), and in 1978 the Labour government gave them the opportunity to do so by creating a May Bank Holiday (originally held on May 1st). Consequently, a slew of Jack processions were revived or created. (For an up-to-date list see The Company of the Green Man n.d.). Two of the largest events today, Rochester Sweeps Festival and Hastings Jackin-the-Green, were created in 1981 and 1983 respectively. They have been followed in the intervening years by a host of others, large and small, urban and provincial, folkloristic or overtly Pagan (such as at the Beltane celebrations in Glastonbury, and the Pagan pride march occurring at the Beltane bash event, held in London during the late 1990s and early 2000s). With the growth of all women Morris sides, and the growing cultural influence of feminist thought more generally, there have also been Jills-in-the-Green, such as that created by the Stroud-based Boss Morris.[5]

The association between Robin Hood and the Green Man complex was strengthened in the eyes of a new generation of children with the British TV series Robin of Sherwood (made by HTV and broadcast on ITV between 1984 and 1986), in which the legendary outlaw was depicted as having been chosen by a horned pagan deity, Herne the Hunter, to defeat the evil Sheriff of Nottingham, in service of wild nature. A similar theme was found in 1983 in the 2000AD comic strip Sláine (Mills and Bisley 2012) where its eponymous Iron Age hero strove to become a new incarnation of a horned god in service of the Earth goddess. In one scene a willing human sacrifice turns into a Green Man.

The ecological reading of the Green Man complex, however, received its biggest endorsement in 1990 with the publication of William Anderson’s Green Man: The Archetype of Our Oneness with the Earth (Anderson 1990). Anderson, a poet and writer, drew on the psychology of Carl Jung to suggest that the Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Robin Hood and the rest were expressions of the same corrective archetype, erupting from the collective unconscious at this moment of ecological crisis so as to restore balance between humanity and the natural world.

Anderson’s ideas were taken up by a charity, Common Ground, established in 1983, which sought to find ways to connect people to nature through heritage and culture, and often through the figure of the Green Man. Common Ground’s Sue Clifford, and Anderson himself, appeared in a 1990 BBC Omnibus documentary titled The Return of the Green Man.[6] It focused mainly on how the Green Man has impacted high culture, with talking heads from the film director John Boorman, the novelist Kingsley Amis, the composer Harrison Birtwhistle, and the artist John Piper amongst others. It also featured the Jack-in-theGreen procession at Rochester Sweeps festival, an interview with Slaine’s creators Pat Mills and Simon Bisley, and remarkable footage of a ritual conducted by some unnamed and masked Wiccans. That segment depicted the High Priest as possessed by the Green Man and subsequently being processed in a state of trance through an English woodland at dawn.

Three Tendencies of the Green Man Complex in Contemporary Culture

Interest in the Green Man complex has remained high well into the 21st century, as exemplified by three tendencies within contemporary culture identified by Letcher (2012). These remain tendencies only and should not be seen as a typology. The first consists of people who are mostly drawn to the Green Man complex by virtue of their interest in folk music, festivals, and culture. For instance, the folk singer Mike Harding, who has published a book of photographs of the Green Man (1998), tends to see the Green Man as a puzzle from a forgotten pagan past, but which nonetheless has the power to infuse contemporary folk music and customs with a sense of mystery and energy. The supposed paganism is acknowledged but kept at a safe distance, and is secondary to the revival and maintenance of tradition.

A second is found among contemporary Pagans and practitioners of alternative spiritualities or what Bron Taylor calls ‘dark green religion’ (Taylor 2010a), for whom the Green Man, and his more mobile counterpart, the Jack-in-the-Green, represent an actual pagan nature spirit or deity. Thus John Matthews, a well-known British, emic pagan author, wrote that the Green Man was ‘much more than a man, more even than a spirit, maybe a God’ (Matthews 1993: 62). The greenness is important, for allegiance to the Green Man signifies an orientation toward green, nature-aware, ecological lifestyles – at least in intention if not necessarily in practice.

Two examples of this second tendency must suffice. In 1991, Tyna Redpath (a longtime eco-activist) opened a shop called ‘The Goddess & the Green Man’ in Glastonbury, a small rural town in the South West of England.[7] The ‘Goddess & the Green Man’ remains hugely successful as one of Britain’s first purveyors and therefore facilitators of Goddess and Green Man religious material cultures. There, one can find and purchase images, spells, books, pendants, art, chalices, candles, herbs, magical charms, and other ritual paraphernalia. Currently, the shop’s website has a section of devotional guidance that reveals what is appropriate to honor, eat, do, and say during the Pagan Sabbats and Celtic Festivals. These festivals form the structure of many contemporary Pagan activities and sit within what is known among Pagans as the Pagan (Ritual) Wheel of the Year. These consist of: Yule/Winter Solstice (December), Imbolc (February), Spring Equinox (March), Beltane (April/May), Midsummer Solstice (June), Lughnasadh (August), Autumn Equinox (September), and Samhain (October/November). Beltane, the most significant to our objectives here, emphasizes fertility and the re-birth of life after the death of winter.

The second example concerns the ‘Pagan Pride’ march, which has been held for many years in the capital at, and around, the turn of the millennium. When march participants paraded a Green Man through Central London, they did so both as an expression of Pagan identity (with obvious influences or even appropriation from the LGBTQA+ Pride movement) but also to celebrate an effigy of what they considered an ancient pagan god. We will return to this tendency shortly by way of a further survey of examples of contemporary Green Man phenomena in culture.

Finally, there is a growing interest in folklore and custom, and its purported pagan origins, that stems from the popularity of folk horror, most especially the totemic film The Wicker Man, and that we call here wyrdlore. A cursory look through Instagram will find hundreds of sites devoted to the weird and uncanny to be found in the countryside, 1970s popular culture, and Britain’s past. There are, for example, a slew of ‘occult zines’ devoted to the subject: Weird Walking, Hellebore, Wyrdzine, Grimoire Silvanus, Magpie Magazine, to name a few, and a growing cottage industry of artists providing wyrdlore tee-shirt designs (for example Sin Eater), stickers, and even tattoos. Such interest comes with an ironic distance: enthusiasts identify with paganism, and all its connotations of the uncanny (see Freud 2003), without necessarily wanting to practice it (see Letcher 2012).

It is, of course, hard to say exactly who or what belongs to each of these tendencies. For instance, the Hastings Jack-in-the-Green ends with the ritual ‘slaying’ of the Jack to ‘release the spirit of summer’. Whether this amounts to a modern Pagan ritual, a knowing nod to 1970s cult movies, or a dramatic moment to provide a satisfying conclusion to a three-day festival remains moot, and the exact meaning will doubtless vary according to each participant.

Festivals, Processions, and the Green Man

Since the Jack has experienced a revival, he has become the celebrated and central focus of a variety of ritual performances and processions in Britain and in other parts of the traditionally (if not geographically) ‘western’ world. Highlighting the second tendency within the Green Man complex as indicated above, many of these performances and processions are deliberately Pagan and religious. Further, despite his critics, aspects of Frazer’s Golden Bough continue to have popular influence on contemporary Pagan and other practices, particularly where celebrations involve the creation and burning of a human or divine wicker effigy (in an obvious borrowing from the aforementioned movie; see Whitehead 2013; 2019), or in processions where the living embodiment of the Green Man moves with and among us.

In Glastonbury, for instance, which is the site of Redpath’s ‘Goddess & Green Man’ shop, there is an annual May Day (Beltane), Pagan ritual performance that was inaugurated in 2007. The performance follows an obviously Frazerian narrative in which the mature male counterpart of the Young Oak King/Jack in the Green (i.e., the fully fledged Green Man) falls in love with and marries the fertile Flora, the Maiden Goddess of Spring. It is a joyous and raucous ritual procession in which the sacred sexual union between the two is re-enacted and celebrated by participants as a perceived continuation of an ancient tradition. A May Pole is erected and the atmosphere is an effervescent, sensual mix of vibrant medieval costuming, green paint and foliage, the blaring of some horns, while other horns come fixed to heads. Drumming, singing, and live acoustic music further set the scene.

From discussions with participants at this event, combined with one of the author’s (Whitehead’s) observations as an animist, Pagan scholar at the event, the Green Man’s role is highly prioritized at the Glastonbury Beltane Celebrations. Participants say that the celebrations are life-affirming, that they promote unity and community, that they are celebrations of ‘green nature’ that foster a connection with the seasonal cycles. The Green Man, with his entourage of foliageclad merry-makers, process down the Glastonbury High Street where they stop for further celebration at the Market Cross. One participant claimed that the celebration is an expression of anarchy, and that there is a distinctive ‘male part’ of the ritual that is particularly associated with ‘the green’. The ‘male part’ of the ritual preparations involves the making of the (phallic) May Pole where it is the men’s job to go and get the (traditionally Ash) tree and carry it on their shoulders. The women are charged with digging the (vulvic) hole where the pole will go. All of this is in keeping with the (implicitly Frazerian) purpose of the ritual celebration: fertility. Whether or not the ritual participants at this event have conscious knowledge of Frazer’s work is unknown (requiring further research); however, from my (Whitehead’s) lived experience among British Pagans, a copy of the Golden Bough can often be found sitting on their bookshelves. This indicates that Frazer’s influence on popular Pagan and perhaps other forms of culture continues to inspire. One further participant said that he can be male ‘without explanation’ at the Beltane celebrations.

Arguably, the Green Man offers, at least for some, a figure of ‘healthy, nature-oriented masculinity’ in light of increasing critiques of ‘maleness’ (framed as patriarchal) from the feminist and eco-feminist groups whose ecological focus, according to Shai Feraro, coalesced with British Paganism, resulting in the growth of Goddess feminism at the turn of the 1980’s as reflected in the influential Wood and Water magazine (see Feraro 2022 for details). Assumed reflections of this movement can be found further in Lynn White Jr.’s famous thesis that the ‘Judeo-Christian tradition, especially Christianity, has promoted anthropocentric attitudes and environmentally destructive behaviors’ (Taylor et al. 2016). Having watched the Beltane processions grow in popularity for over a decade (see Birchall 2016), and coupled with existing Pagan interest in masculine, horned figures such as Herne the Hunter, Cernunnos, and Gwyn ap Nudd[8], it can be argued that the Green Man in the Glastonbury Beltane Celebrations is becoming a point of convergence and focus for a further subset of localized, male-oriented Pagan beliefs and practices. A Facebook group, ‘The Greenmen of Glastonbury’, created in May, 2016 (see The Greenmen of Glastonbury 2021), supports this claim and can contribute one example to an emergent field of Pagan masculinities that, as Feraro has pointed out in his article ‘Penis, Power and Patriarchy: Troubled Masculinities in British Paganism Set Against the Feminist Challenge of the 1970s and 1980s’ (Feraro 2023), has been largely overlooked to date. These beliefs/ practices emphasize, reclaim, and celebrate masculinity, as opposed, or in addition to, emphasis that has been placed on the Glastonbury Goddess. This emphasis has, by some accounts, become too dominant in the town, and has resulted in an imbalance between masculine and feminine (Whitehead 2019). There is a further political element to the ritual, with one participant shouting ‘Go Green!’.

An instance of where a Green Man is a modern feature at Beltane events (alongside a May Queen) can be found in the Beltane Fire Festival that takes place in Edinburgh, Scotland, which began in 1988. According to the Beltane Fire Society website (the society is a not-forprofit registered charity in Scotland), although the festival is inspired by the ancient Gaelic festival of Beltane and ‘draws on a variety of historical, mythological and literary influences’. However, according to the Beltane Fire Society (2021a) ‘the organisers do not claim it to be anything other than a modern celebration of Beltane, evolving with its participants. The purpose of our festival is not to recreate ancient practices but to continue in the spirit of our ancient forebears and create our own connection to the cycles of nature’. Followed by ‘a cavalcade of characters who are intrinsically linked to them and their journey’, both the May Queen and the Green Man lead the procession where they usher in the summertime by lighting a bonfire.

Festivals in Britain, the U.S., and New Zealand also demonstrably favor what the Green Man as a figure has to offer, i.e., ecological awareness and inspiration for art. Though held in August not May, the family friendly ‘Green Man Festival’, a music and arts festival established in 2003 with 25,000 capacity, takes place annually in Wales at a site called ‘the Settlement’. The Green Man festival has an emphasis, not surprisingly, on ‘being green’ and centers around a giant statue of a Green Man. And the Green Man has made thematic appearances at the famous Burning Man festival in the U.S. State of Nevada (established 2007) in the Black Rock Desert, as well as in New Zealand’s ‘glocalised’ version of Burning Man called ‘Kiwiburn’.

Pulling together what all this means is difficult given the previouslynoted diversity of Green Man-related phenomena. What for one participant is an act of Pagan devotion might be for another an ironic, playful expression of identity, or a more serious display of (possibly reformed) masculinity. Though Frazer’s historiography has been discounted by many scholars, his creation and reading of what we are calling the Green Man complex remains the dominant trope through all these various expressions. For many the Green Man complex is, always was, and remains, an expression of heteronormative ideas of fertility, even if it is doubtful whether participants give credence to the notion that their actions will result in an abundant harvest.

Resistance and Re-territorialization: Mobilizing the Green Man

One of the primary roles of ritual and other material performances are to direct attention to some thing (a place, site, concept, myth, or event). Processions, both ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ (if such distinctions can be made) are, in fact, a form of ‘cultural work’ that serve to generate beliefs, and reinforce narratives and belonging. This can be seen when, for example, religious statues such as the Virgin Mary or the Glastonbury Goddess (both woven and carved from wood) are processed in their religious contexts (see Whitehead 2013; 2019). In the cases where Green Men and Women are processed, attention is being directed to ‘the green’, nature, vegetation, fertility, and untamed wildness (especially in urban environments). Unlike Marian and Goddess statues which are animated in different ways (see Whitehead 2013), the Green Men/Women in these processions are living, foliage-donned and green-painted human performers that both signify and embody ‘living nature’. Mobilizing Green Men and Jacks-in-the-Green through processions draws audience and participant attention to green nature – as well as that which sits at the heart of Pagan practices, beliefs, and intentions.

We have already established that the dynamics of these events are relational (to place, space, intention) and differ from town to town, site to site, and it is difficult to measure the tendencies within each of these celebrations, and further still, the tendencies within the individuals taking part. What can be deduced, however, is that within each of these events, from a greater to a lesser extent, ‘resistance’ is at play. This resistance takes many forms. It can be resistance to ‘mainstream culture’ through aforementioned revivalist intentions of folk music, traditions, and cult films/literature. Within Pagan practices and worldviews, it can be resistance to, or critique of, mainstream (predominantly Christian) religious cultures that emphasize transcendence over immanence, and which are still productive cultural constructs that would, at least technically, reinforce dualisms between green nature from culture, or spirit from matter, or earth (on which see Whitney 2015; Taylor 2016). In the case of Glastonbury, it can be suggested that the Green Man also embodies resistance against what are deemed to be toxic forms of masculinity.

We would, however, like to advance this notion of resistance and argue that through the visual performances of Green Man processions a form of what Gilles Deleuze and Pierre-Felix Guattari (1972) refer to as an active ‘territorialisation’ is taking place, which signals a clear statement that ‘Jack is back’. In fact, similar to what was argued with regard to the annual Glastonbury Goddess processions where a wicker woven statue of the Glastonbury Goddess is processed to and through the most significant sites in the town (see Whitehead 2019), territorialization in these contexts can be better understood using what Kellie Jones (2011) refers to as ‘reterritorialization’ [italics our emphasis]. To Jones, this means: ‘recapturing one’s (combined and various) history, much of which has been dismissed as an insignificant footnote to the dominant culture’ (Jones 2011: 339). The ‘insignificant footnote’ that has been dismissed in the contexts of Green Man processions is none other than green nature, and the ritual ‘recapturing’ is done through both costuming and processing the god or vegetation spirit so that it can be seen, felt, and visually experienced particularly at significant moments such as May Day (the meaning of which wider publics in Britain are somewhat conscious).

It seems reasonable to suggest, therefore, that when Green Men (and sometimes Green Women) are ritually mobilized and processed through a town, city, or even landscape, a claim is being staked by the ritualists on behalf of green nature. These actions also reinforce the lyrics of the beforementioned Jethro Tull song, ‘Jack-in-the-Green’, i.e.:

Jack do you never sleep – does the green still run deep in your heart? Or will these changing times, motorways, powerlines, keep us apart?

Well, I don’t think so.

I saw some grass growing through the pavements today. (Tull 1977)

That many veterans of the 1990s anti-road building movement eventually settled in Glastonbury, and participate vocally in the Beltane celebrations, and other ritual moments in the town, is also significant here (see Letcher 2005).

For many (Pagans, non-Pagans, and scholar-enthusiasts[9] alike), the presence of the Green Man figure signals the presence, significance, and perhaps even the power of the other-than-human vegetable kingdom. If humans were to cease to exist, green nature would take hold and envelop our towns, cities, roads, and tunnels. What has happened to the urban environment of Chernobyl[10] since the disaster in April 1986 serves as a stark reminder that the spirit present in the figures of the Jack-in-the-Green and the Green Man will always prevail, whether we are here to witness it or not.

Further, new religious, alternative, and other movements tend to emerge at times of personal, social, and now we add environmental, crisis and when mainstream religions are not speaking directly to and addressing the needs of the people, or indeed, the Earth. Paganism can be broadly categorized as a ‘revitalization movement’, for example (Stein and Stein 2017: 260). Within the broad concept of ‘revitalization’, Paganism is ‘revivalistic’ due to the emphasis on reviving what practitioners perceive to be Celtic, pre-Christian (Stein and Stein 2017: 265–67), or ancient European practices that, for contemporary Pagans, signal healthier relationships with the natural world but have been intentionally suppressed by Christians. As mentioned above, although not historically accurate (nor does it need to be), the Green Man image is being utilized as the ancient embodiment of green nature, and provides a fecund source of inspiration for the Pagan imagination with its ‘getting back to’ emphasis on a cleaner, greener, pre-industrial, premodern age. It can be argued, then, that the ‘return of the Jack’ as a figure of interest is not coincidental, as indeed William Anderson suggested back in the 90s. But rather than being some archetypal upwelling from the collective unconscious, the visible and practical growth of the Green Man complex is heralding a call that corresponds with a host of other (dark green, religious, eco-spiritual) movements that have consciously emerged in recent years in response to our ecological crisis. Here, resistance against the more ecologically damaging realities of modernity and neoliberalism can also be discerned. This includes territorialization, as ritually carried out by Green Men and Jacks-inthe-Green, and can refer to reinstating emphasis on green nature in our time of trouble.

Costuming and Performance: Re-thinking the ‘Symbol’ with the Green Man

In addition to resistance and (re-)territorialization, the role of costuming as Green Men and Women during processions will now be further explored. Here, using the inspiration that may have stirred the popular Pagan Beltane celebrations in Glastonbury, we call once again upon Frazer (2012), if not to conversely redeem an aspect of his work, to assist in this next theoretical assertion: that for practitioners, ritually costuming as the Green Man/Jacks-in-the-Green at British processions is more than symbolic; it is, instead, a form of ritual eco-magic that can be read using Frazer’s categorization of sympathetic, homeopathic, or imitative magic based on the principle that ‘like attracts like’. Examples of ritual imitative magic are numerous, but to provide a few: in Western folklore, plants and other beings from the vegetable kingdom who are known to have healing properties can be identified through their imitative qualities. Here, the Law of Similarity works thus: ‘red cloverhead is used to treat problems of the blood, as is the red sap of bloodroot. Indigestion is treated by several yellow plants associated with the yellow color of bile that is often vomited up’ (Stein and Stein 2017: 148). Another example includes fertility rituals, similar elements of which can be found among a number of Australian Aborigine groups called ‘increase rites’ who, by drawing certain designs, placing certain objects on their bodies, and by re-enacting animal copulation, become their totem animal and therefore ritually ensure their reproductive success (Stein and Stein 2017: 148). Applying this working concept to costuming as the Green Man and prevalent in the deliberate intentions found among Glastonbury (and possibly other) Pagans at the Beltane celebrations, it can be argued that dressing up as (or ‘like’) Green Men and Women ritually invokes ‘like’. This gesture can be read as an invitation, or perhaps an invocation, for green nature to: a) return in the spring after the dormant phase of winter; b) make its/his presence known; and c) fuse with human participants at the borders where the human and vegetable kingdoms meet. In other words, costuming as the Green Man, by default, actively requests, invites and invokes the presence of the Green Man.

We suggest, then, that the act of costuming as the Green Man is more than symbolic, more than representational, and more than metaphorical. He is an agentic presence that acts on behalf of all things green. One person who has played the Green Man at the Glastonbury Beltane Celebration, as well as horned god Gwyn ap Nudd, revealed that he ritually ‘becomes’ these figures, takes pains over his preparation for the event, and meditatively invokes the spirit of that who he becomes. A further account from the man called Rosamund, played the Green Man at the Edinburgh Beltane Fire Festival read:

The role of the Green Man appeared to me like a snowdrop in December – surprising, exciting and somewhat daunting. An opportunity for fresh growth.

Just before meeting with…the May Queen, I was awash by a wave of emotions. I went out in the field, getting caught on the hawthorn and beech branches. Struck by the lack of the loving, supportive and grounded divine masculine energy that I (and somewhat ‘society’) can neglect to cultivate in the self. I’m hoping to explore this aspect through my time in this role, expanding it to the land and further. Taking the joyful, bold, vulnerable and protective nature of the Green Man as my measure.

This springly being of the Green Man offers up a sacrifice – of that which must be burned upon the fire. (Beltane Fire Society 2021b)

As Alfred Gell stated in relation to the notion of ‘idolatry’, this is not ‘pretend’ or ‘make-believe’ (Gell 1998: 134). Gell says: ‘The essence of idolatry is that it permits real physical interactions to take place between persons and divinities. To treat such interactions as ‘symbolic’ is to miss the point’ (1998: 135). Ritually embodying or becoming a god or spirit is not the same as worshipping one, as Gell makes clear. However, reducing interactions between humans and the objects of their worship to the merely ‘symbolic’ offers an impoverished view of the lived reality of the performance, its function, and what it offers both participants and lookers on. In fact, Taylor, making the link between idolatry and nature, suggests that we embrace an idolatry of nature, and that when we do, we will ‘stand up for wild natural processes, to which we, and all life, owe our existence, our vitality, and therefore, our fidelity’ (Taylor 2010b: 105). The ‘mobilised idol’ (or central figure of Beltane processions) of the Green Man, exemplifies how Taylor’s suggestion can work in practice. The living idol of the Green Man in procession carries out a particular, efficacious form of cultural work that, we contend, links audiences and participants into a reality that re-frames ‘nature’ as a living spirit alongside and with whom we all exist. This, in turn, can help us re-think what we believe to be unnecessary dualisms such as ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, as well as the safe notions of ‘representation’, ‘symbolic’ and ‘metaphor’ (Whitehead 2018: 76), the constructs of which have served a cage-like function of keeping the wildness of nature contained.

Finally, and significantly, the contemporary expressions that we have outlined here open themselves to an animistic reading. Graham Harvey succinctly defines animists as, ‘people who recognize that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others’ (Harvey 2005: 16). The key aspect here is that in a world full of persons, it behoves us to find and maintain correct relationships with the other-than-humans with whom we live. That typically involves acts of reciprocity, a giving back for the things that we routinely take, or take for granted. If, as Ronald Grimes has argued so playfully and forcefully, ‘performance is currency in the Deep World’s gift economy’ (Grimes 2002) then one could argue that the elaborate costumes, the Green Man masks, the Jack-in-the-Green puppets, the day-long processions, the music and revelry are less to do with ensuring fertility, and more to do with respectfully giving something back. They may no longer make offerings of alcohol, food, or tobacco (as traditionally animist cultures often do) but by giving time, sleep, energy and attention (our most precious of commodities these days) to the green upon which we all depend, participants are paying gratitude and respect to the wild world, through performance.

Conclusion

We believe that the renaissance of the Green Man in contemporary British and other cultures is timely. While it is unlikely that this revival was, initially, a deliberate attempt to draw attention to the significance of green nature in the ever-quickening pace of our industrialized societies, what is certain is that in addition the revival of the Green Man through the mediums of art, performance, and protest in the 20th century – the most recent revival of the Green Man in the 21st century especially, particularly within the performances found in contemporary Pagan movements – is doing a particular kind of cultural work that is drawing even further attention to the other-than-human Plant Kingdom in this unprecedented time of ecological crisis.

Our combined scholarly voices have offered both a survey of the figure of the Green Man and the Jack-in-the-Green in contemporary, primarily British, culture, as well as an overarching theoretical framework in the form of the Green Man complex within which to place the emergence of Green Man phenomena in culture. Three tendencies have been identified within the Green Man complex, each reflecting aspects of culture that have been influenced, whether deliberately or unconsciously, by the work of James G. Frazer: the first consists in people who are mostly drawn to the Green Man complex by virtue of their interest in folk music, festivals, and culture. The second is found among diverse groups of contemporary Pagans and/or practitioners of Taylor’s dark green religion, for whom, depending on the context, the Green Man, and his more mobile counterpart, the Jack-in-the-Green, can represent either an actual pagan nature spirit or deity, a powerful figure for a beleaguered natural world, or a galvanizing champion for all things green. As we have highlighted, although pre-Christian pagans in Britain may not have venerated a Green Man figure, contemporary Pagan adherents certainly do now, and this growing trend reflects the richness, viability, and complexity of their belief and practice in Britain and beyond. Lastly, we outlined a third tendency which reflects a growing, if ironic, interest in folklore and custom, and its purported pagan origins, that stems from the combination of interest in (at least) the idea of nature and the popularity of folk horror, and that we call here wyrdlore.

While all of these tendencies have received a degree of scholarly attention, we have drawn specifically on the second tendency of Paganism where we have highlighted the ritualized, embodied performances that are generating interest and popularity in the UK. Processions in particular have been addressed to highlight the ways in which the Green Man is being mobilized by Pagan groups. We also found within this second tendency that a sub-set of Paganism is emerging that centralizes the Green Man figure as a model for a healthy form of masculinity. We have also suggested that costuming as the Green Man is more than ‘symbolic’ or ‘representational’, but reciprocal, embodied acts that are helping us to re-think the ways in which we understand and value the power and significance of ritual performance. And finally, we have suggested that there is a possible animist reading of the Green Man complex, in which the processions, costumes, and taking to the streets in eco-protest, represent an act of reciprocity, a giving back to the other-than-human vegetable kingdom upon which we all depend.

Whatever his origins in the historical past, the Green Man has sprung back to life with renewed gusto. His very ambiguity allows a continual play of new meanings to arise and as such we expect to see more and more people dancing with Jack-in-the-Green as the spring returns each year.

References

Anderson, William. 1990. Green Man: The Archetype of Our Oneness with the Earth (London: Harper Collins).

Bacon, Lionel. 1974. A Handbook of Morris Dances (The Morris Ring).

Basford, Kathleen. 1978. The Green Man (London: D. S. Brewer).

Beltane Fire Society. 2021a. ‘About Beltane Fire Festival’. Accessed 29 June 2021. https://beltane.org/about-beltane/

Beltane Fire Society. 2021b. ‘Meet Our Green Man: Rosamund’. Accessed 29 June 2021. https://beltane.org/2021/03/26/meet-our-green-man-rosamund/

Birchall, Ben. 2016. ‘Glastonbury Beltane Celebrations – in Pictures’. The Guardian. Accessed 2 May 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2016/may/02/glastonbury-beltane-celebrations-in-pictures

Blain, Jenny, Douglas Ezzy, and Graham Harvey. 2004. Researching Paganisms (Lanham: Altamira Press).

Brown, Allan. 2000. The Wicker Man: The Morbid Ingenuities (Basingstoke: Sidgwick and Jackson).

Davy, Barbara Jane. 2007. An Introduction to Pagan Studies (Lanham: Altamira Press).

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1972. Anti-Œdipus. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. 2 vols. 1972–1980 (London and New York: Continuum, 2004) Translation of L’Anti-Oedipe (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit).

Doel, Fran and Geoff Doel. 2001. The Green Man in Britain (Brimscombe Port, Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited).

Feraro, Shai. 2022. ‘A Song of Wood and Water: The Ecofeminist Turn in 1970s–1980s British Paganism’ in B. Singler and E. Barker (eds). Transformations in Minority Religions (Abingdon: Routledge): 102–17.

———. 2023 (forthcoming). ‘Penis, Power and Patriarchy: Troubled Masculinities in British Paganism set against the Feminist Challenge During the 1970s–1980s’, Correspondences: Journal for the Study of Esotericism 11.1.

Franks, Benjamin, Stephen Harper, Jonathan Murray, and Lesley Stevenson. 2006. The Quest for the Wicker Man. History, Folklore and Pagan Perspectives (Edinburgh: Luath Press Ltd.).

Frazer, James G. 1913. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, Third Edition, Volume 11. Balder the Beautiful: The Fire-Festivals of Europe and the Doctrine of the External Soul, Part 1 (London: MacMillan & Co. Ltd).

———. 2012. ‘Sympathetic Magic’ in The Golden Bough, 3rd ed., 1: 52–219. Cambridge Library Collection – Classics. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139207485.006

Freud, Sigmund. 2003 [1919]. The Uncanny (London: Penguin Books).

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Graebe, Martin. 1972. ‘Jack in the Green’. Unpublished folk song. https://martinandshan.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Jack-in-the-Green.pdf

Grimes, Ronald L. 2002. ‘Performance is Currency in the Deep World’s Gift Economy: An Incantatory Riff for a Global Medicine Show’, ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in

Literature and Environment 9.1: 150–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/9.1.149

Harding, Mike. 1998. A Little Book of the Green Man (London: Aurum Press Ltd.).

Harvey, Graham. 1997. Listening People, Speaking Earth. Contemporary Paganism (London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers Ltd.).

———. 2005. Animism. Respecting the Living Earth (New York: Columbia University Press).

Hutton, Ronald. 1993. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers).

———. 1999. The Triumph of the Moon. A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

———. 2013. Pagan Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Jones, Kellie. 2011. Eye Minded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Judge, Roy. 2000 [1979]. The Jack-in-the-Green (London: FLS Books).

Lady Raglan. 1939. ‘The “Green Man” in Church Architecture’, Folklore 50.1: 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1939.9718148

Letcher, Andy. 2005. ‘“There’s Bulldozers in the Fairy Garden”: Re-Enchantment Narratives in British Eco-Paganism’, in L. Hume and K. Phillips (eds.) Popular Spiritualities: The Politics of Contemporary Enchantment (London: Ashgate): 175–86.

———. 2012. ‘Paganism and the British Folk Revival’, in D. Weston and A. Bennett (eds.) Pop Pagans: Paganism and Popular Music (London: Routledge): 91–109.

Lyons, Nina. 2016. Uprooted: On the Trail of the Green Man (London: Faber and Faber).

MacDermott, Mercia. 2003. Explore Green Men (Wymeswold, Loughborough: Heart of Albion Press).

Matthews, John. 1993. Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wildwood (Glastonbury: Gothic Image Publications).

Mills, Pat and Simon Bisley. 2012. Sláine: The Horned God. London: REBCA.

Plester, Tim and Rob Curry (dirs.). 2011. The Way of the Morris (Fifth Column Films, London): DVD.

Reader’s Digest. 1977. Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain (London: Reader’s Digest Association Ltd.).

Roud, Steve. 2006. The English Year: A Month by Month Guide to the Nation’s Customs and Festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night (London: Penguin Books Ltd.).

Sermon, Richard. 2006. ‘The Wicker Man, Mayday and the Reinvention of Beltane’ in B. Franks, S. Harper, J. Murray, and L. Stevenson (eds.) The Quest for the Wicker Man: History, Folklore and Pagan Perspectives (Edinburgh: Luath Press Ltd.): 26–43.

Stein, Rebeca and Philip Stein. 2017. The Anthropology of Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft (Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Taylor and Francis Group).

Taylor, Bron. 2010a. Dark Green Religion. Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press).

———. 2010b. ‘Idolatry, Paganism, and Trust in Nature’, The Pomegranate. 12.1: 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1558/pome.v12i1.103

———. 2016. ‘The Greening of Religion Hypothesis (Part One): From Lynn White, Jr and Claims That Religions Can Promote Environmentally Destructive Attitudes and Behaviors to Assertions They Are Becoming Environmentally Friendly’.

Journal for the Study of Religion, Culture and Nature 10.3: 268–305. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.v10i3.29010

Taylor, Bron, Gretel Van Wieren, and Bernard Daley Zaleha. 2016. ‘Lynn White Jr. and the Greening-of-Religion Hypothesis’. Conservation Biology 20.5: 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12735

The Company of the Green Man. n.d. ‘The Revival of the Jack in the Green’. https://thecompanyofthegreenman.wordpress.com/the-revival-of-the-jack-in-the-green/

The Greenmen of Glastonbury. 2021. ‘The Greenmen of Glastonbury Facebook Page’. Facebook, June 30, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/groups/110624469351633/about

Tull, Jethro. 1977. ‘Jack in the Green’. Track 02 on Songs From the Wood, Chrysalis Records, Vinyl.

Whitehead, Amy. 2013. Religious Statues and Personhood: Testing the Role of Materiality. (London: Bloomsbury).

———. 2018. ‘Fetish Things: Personhood, Power, and Uncomfortable Relations’ in M. Astor-Aguilera, M. and G. Harvey (eds). Rethinking Relations and Animism: Personhood and Materiality (London: Routledge): 75–93.

———. 2019. ‘Indigenizing the Goddess: Reclaiming Territory, Myth and Devotion in Glastonbury’, International Journal for the Study of New Religions. 9.2: 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsnr.37621

Whitney, Elspeth. 2015. ‘Lynn White Jr.’s “The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis” After Fifty Years’. History Compass 13.8: 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12254

Young, Rob. 2010. Electric Eden. Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music (London: Faber and Faber).

[2] In this paper we follow British convention by referring to pre-Christian European religiosity as pagan (lower case), and those related, nature-based, postwar revived religions as Pagan (upper case). In the U.S., the latter are typically referred to as Neopagan.

[3] Morris dancing is a traditional type of English folk dance involving teams, or ‘sides’, performing set dances to live accompanying music. It exists in two main styles: Cotswold Morris (as the name suggests from the Cotswolds are of Southern England) and Border Morris (from the counties where England borders Wales). It is popularly thought to be a pagan survival, to do with ensuring the fertility of the land, though this has been dismissed by recent scholarship: its most likely origins are as a Tudor court dance (Hutton 1993). By the opening of the twentieth century Morris dancing was in terminal decline (not least because so many practitioners had been killed during WW1) but it was self-consciously revived by bourgeoise folk music collectors, most notably Cecil Sharp (1859–1924), who regarded it, not unproblematically, as expressing something quintessential to the English völksgeist (see Letcher 2012). Though it has waxed and waned in popularity (often regarded as cloyingly nostalgic and unfashionable by cosmopolitan commentators), it is currently undergoing a resurgence, not least as modern Pagans seize upon its purported pagan origins to create expressly Pagan sides (such as Dartmoor’s Beltane Border Morris, Rochester’s Wolf’s Head and Vixen Border Morris, Croydon’s Wild Hunt Bedlam Morris, and Hereford’s Blackthorn Border Morris) (see Plester and Curry 2011; Bacon 1974; Young 2010; Letcher 2012).

[4] To give just two examples, folk musician and radio presenter Mike Harding wrote how, when first he encountered a Green Man carving, he was told that ‘it represented a pagan fertility figure’ (Harding 1998: 11). In her more recent memoir, Nina Lyons states emphatically that the Green Man ‘is a sort of forest-god, an emblem of the birth-death-rebirth cycle of the natural year’ (Lyons 2016: 7). The persistence of such associations is decried by Roud (2006).

[5] Boss Morris are an all-woman Cotswold Morris Dance side, founded in Stroud, UK, in 2015. They are known for their folk-inspired costumes, their use of electronic dance music, and for producing videos that obviously reference folk horror movies such as The Wicker Man. They have made numerous media appearances. See https://www.bossmorris.com/about.

[6] Available at time of writing at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7kR-_iTRUw.

[7] See https://www.goddessandgreenman.co.uk/.

[8] Herne the Hunter appears in British folklore as a spectre haunting Windsor Great Park but became depicted as a horned god in the aforementioned Robin of Sherwood. Cernunnos is the purported name of an Iron Age horned deity from the Paris region, while Gwyn ap Nudd is a figure from medieval Welsh literature, who appears first as one of King Arthur’s warriors and later as a deity of the underworld at Glastonbury (Hutton 1993). Though historically unrelated, in the modern popular imagination all three are now regarded as different expressions of the same, male, horned god.

[9] Both authors have affinities with and appreciation for various historical, popular, literary, and contemporary Pagan manifestations of the Green Man, whilst retaining a critical stance towards the phenomena. We are, in other words, critical insiders.

[10] The Chernobyl disaster refers to the accident that took place during a test of one of the nuclear reactors at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant on 26 April, 1986, near the city of Pripyat in what was then the Ukrainian SSR in the Soviet Union, and after the union’s collapse in 1991 became Ukrainian territory. This event is widely considered the worst disaster arising from a nuclear power plant in human history. It the forced and permanent removal of thousands from their homes in the region. What has resulted is an unexpected experiment in ‘rewilding’ such that, despite the toxic levels of radioactivity, biodiversity has flourished in the absence of human interference.