Ana Salvá

Swedish man who dined with Khmer Rouge’s Pol Pot 40 years ago: I regret it

-

Communist Gunnar Bergstrom visited Cambodia in 1978 at the tail end of its rule, after being inspired by the Khmer Rouge’s vision of utopia

-

He was taken on a sanitised tour around the country, and even had dinner with the regime’s leader – a period of his life he is now documenting in a book

In August 1978, when Cambodia’s borders were closed off to the world, a young Swedish man – inspired by the Khmer Rouge’s vision of building a society based on freedom and equality – managed to gain entry into the country.

Gunnar Bergstrom, then 27 years old, was one of the many Swedes who protested the Vietnam war in the 1970s – an era in which he became increasingly disillusioned with Soviet communism.

Turning his attention to Cambodia, which he viewed as having been liberated from the capitalist Americans, Bergstrom created a students’ friendship association with the aim of helping the Khmer Rouge to spread its ideals.

The communist regime, which ruled between 1975 and 1979, presided over one of the worst mass murders in the 20th century. It is estimated around 2 million people – a quarter of Cambodia’s total population – were killed by the Khmer Rouge.

Gunnar says he and his associates heard some stories of the atrocities through refugees. But, consumed by ideology at the time, “we did not want to believe them”.

More than 40 years later, Bergstrom, now 68, is repentant about those “naive” days. The Stockholm resident has been channelling his remorse into a book about people like himself – dreamers who were so driven on chasing utopia, they became blind to reality.

Bergstrom’s 1978 visit to Cambodia was the result of two years of persistent negotiations for his association to gain access into the country, and took place three years after the Khmer Rouge came to power.

Khmer Rouge leaders convicted of genocide in landmark court ruling

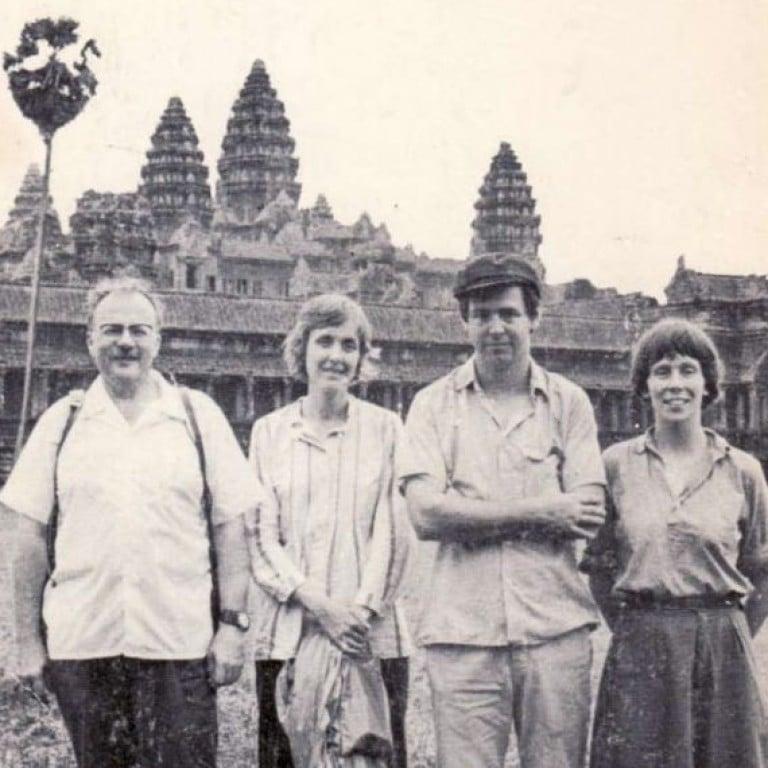

Bergstrom travelled there with three other members: Swedish author Jan Myrdal and two activists Marita Wikander and Hedvig Ekerwald.

Myrdal, now 91, is a controversial figure who is widely known for his denial of Cambodia’s genocide.

“We told [the Khmer Rouge] that we had an association and an office in Paris. They had a small office in Berlin and a large embassy in China. When we asked them if we could report on Cambodia, we were welcome,” says Bergstrom.

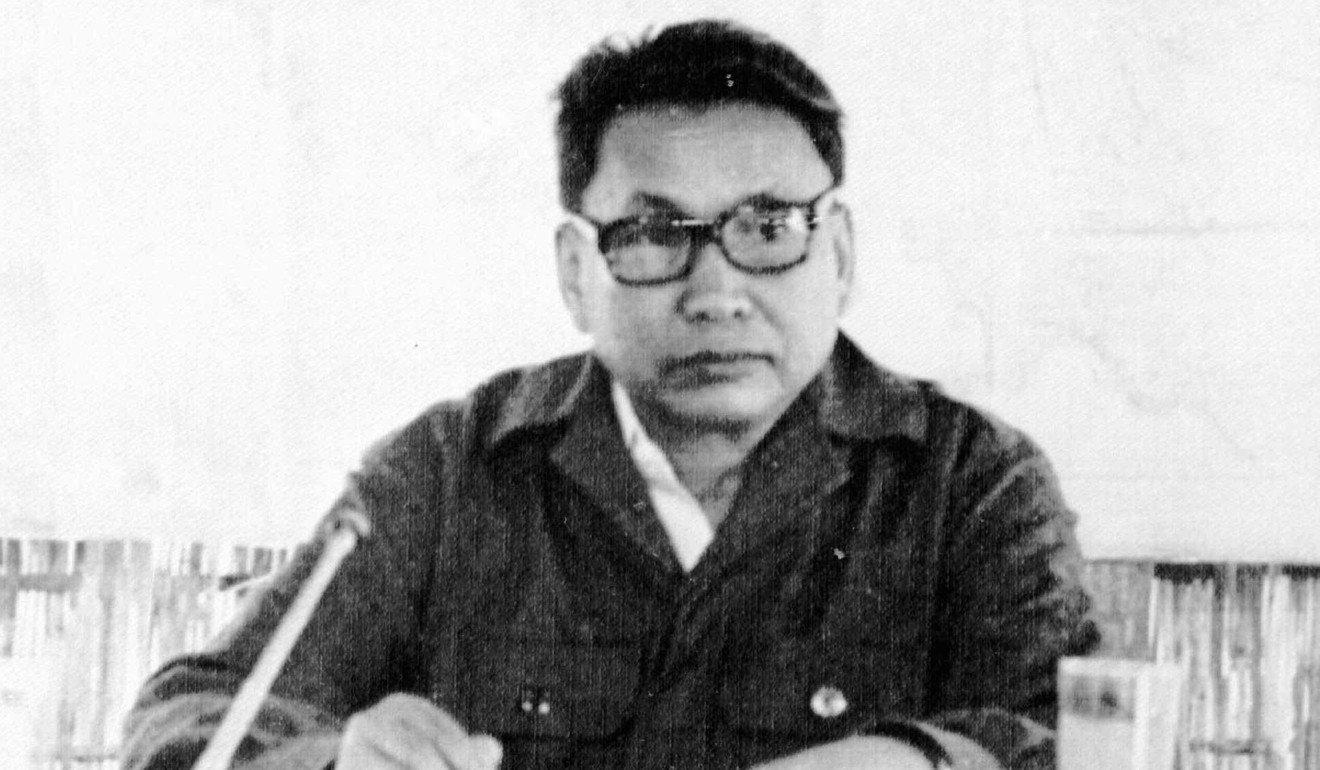

During the group’s two-week visit, they were shown a positive facade of Cambodian life after the revolution, where people worked in well-run hospitals and factories. They were even granted a dinner with Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.

Bergstrom says the leader “did not make a strong impression”, answering many questions with stock replies. “But he did not seem crazy as some people suggested.”

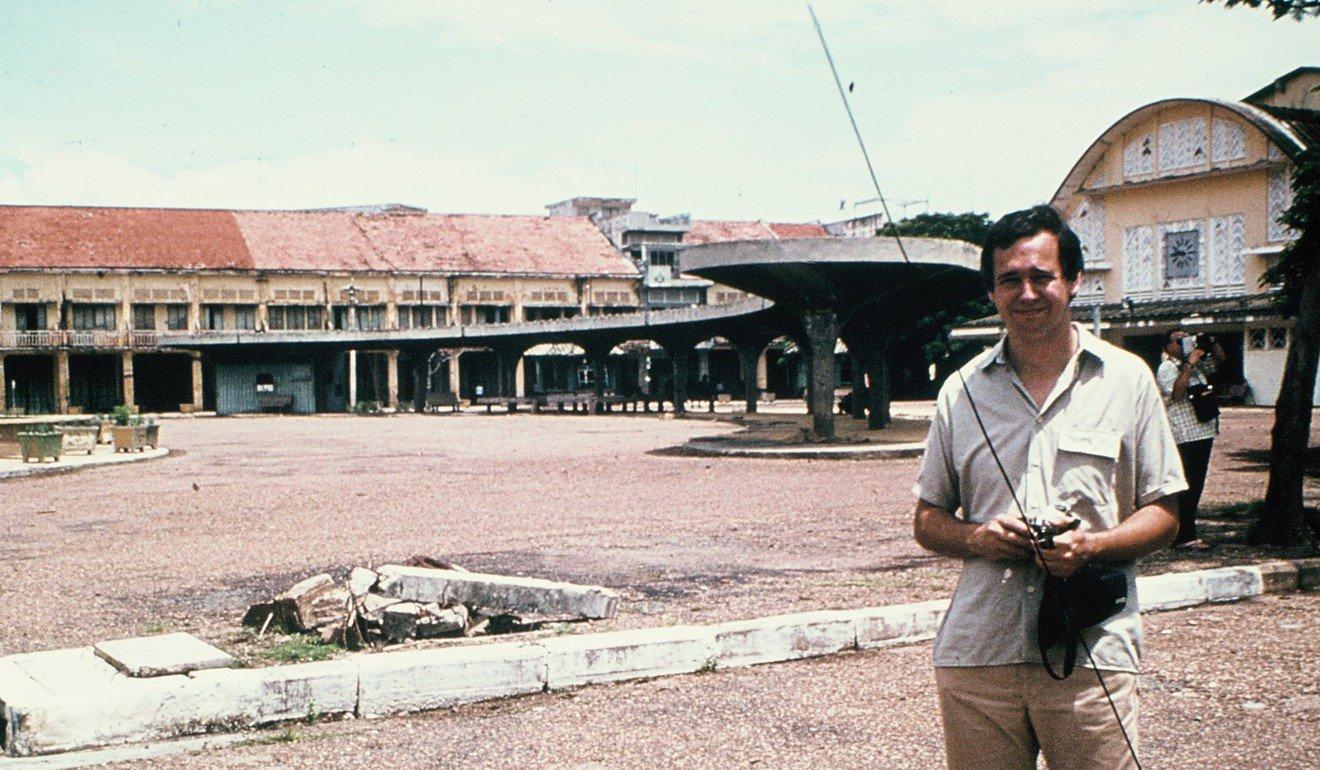

A few scenes in the empty city of Phnom Penh gave Bergstrom hints that life was perhaps not all rosy in Cambodia, including children working hard on boats and fishing for frogs. But he did not question further, when the tour guides, who were members of the regime, told the group the children were orphans who were being taken care of by having jobs.

Bergstrom said he found that international reporting about the regime was riddled with errors.

There was a news report saying people wearing glasses were being murdered in Cambodia, but said he saw some people wearing them. A New York Times article published during his visit reported that a well-known Khmer Rouge member had been killed, but Bergstrom says: “He was the person who accompanied us during the tour.”

Technology brings fresh hope in the search for Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge-era mass graves

Little did he know, the Khmer Rouge’s regime was about to crumble. Several months after Bergstrom went home, Vietnamese communists invaded Phnom Penh in January 1979, finding an impoverished country ravaged by mass killings.

Thousands of bodies were discovered at the infamous S-21 prison – a centre that was one of some 150 others used to interrogate, torture and execute those considered by the regime to be enemies of the state. While most of the inmates in such centres were Cambodian, a small number came from nations such as Vietnam, Thailand, France, the US and Australia.

The Vietnamese communist forces also found documents relating to 14,000 executed people and 12 survivors, who were all logged and photographed by the Khmer Rouge before they entered the building. S-21 has since been turned into a museum chronicling the genocide.

As evidence of the Khmer Rouge’s crimes against humanity mounted, Bergstrom grew increasingly sickened by his support for the regime and left the association after writing an article in a Swedish newspaper acknowledging the error of his ways. “It continued to operate a few more years and was later disbanded,” he says of the association.

In the years since his exit from the group, Bergstrom has focused his efforts on his psychiatric career, specialising in the rehabilitation of drug addicts. But he has continued keeping an interest in Cambodia by running a website about the country and the Khmer Rouge.

Khmer Rouge banned Cambodia’s traditional masked dancing for its decadence – but the ancient art survived

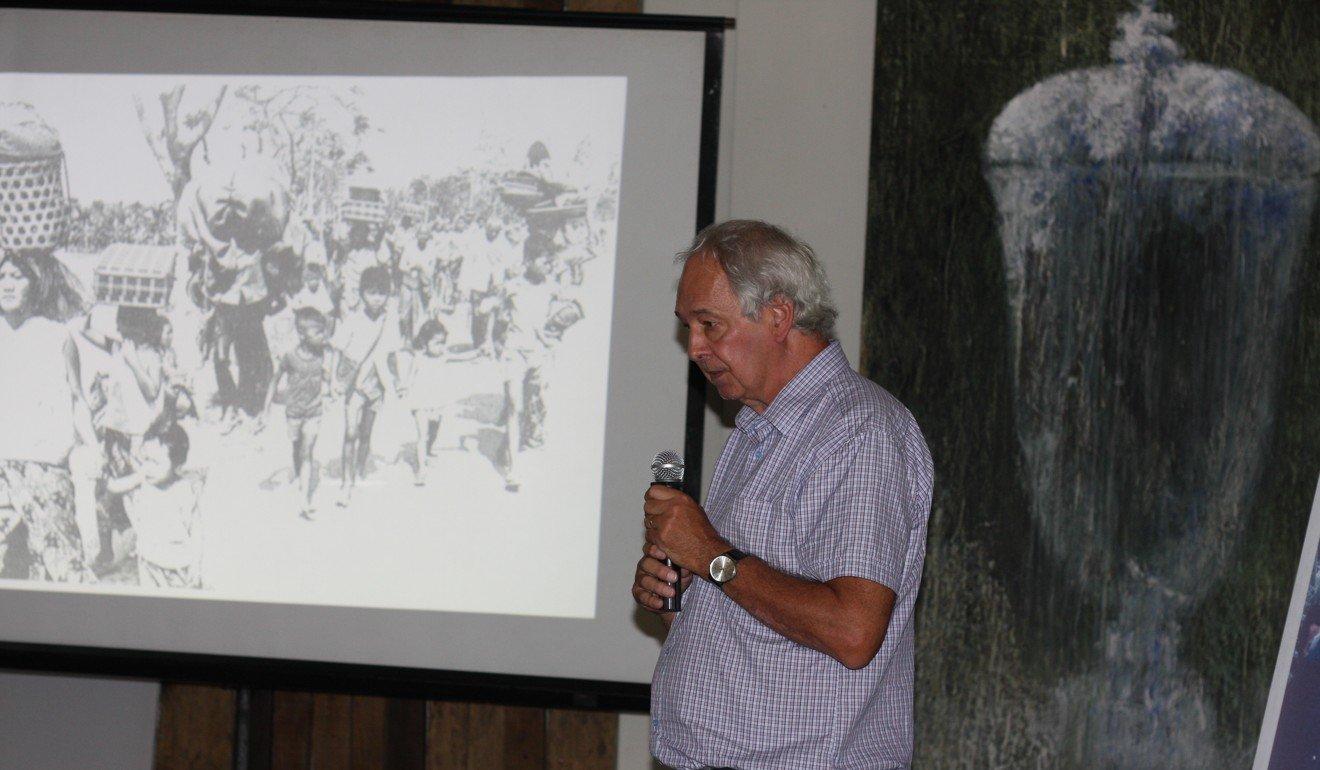

In 2008, three decades after visiting Cambodia as a guest of the regime, Bergstrom returned to the country to apologise to survivors of the genocide, and to present photographs of his trip to a museum.

Eight years later, he went back again to give a talk at a high school in Phnom Penh, where he told students it was vital to “learn from history” to prevent the resurgence of a regime capable of crimes against humanity.

According to Bergstrom, his companions on the trip have not apologised.

Myrdal has continued to write articles that cast the Khmer Rouge in favourable light, while Wikander, the widow of a Khmer Rouge ambassador in East Berlin, has preferred not to talk about those years. Bergstrom says Ekerwald does not support the former regime any more, though she has not said this publicly.

Bergstrom says his book manuscript is ready and he is waiting for a response from a publisher.

“If I get my book published, I hope to encourage critical thinking and respect for human rights and democracy,” says the Swede. “I’m not a communist today because communism has, when it has been put into use, caused a lot of suffering and has never worked the way I and many others had hoped.”