Anne Garland RMN, MSc.

School of Health Sciences

The University of Nottingham

The role of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion

In persistent, treatment resistant depression

Chapter one: Introduction and overview

Depression and co-morbid disorders

Motivation for conducting this study

The cognitive science of depression

The evidence base for Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

TABLE 1: DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER (APA 2013 P 160–161)

TABLE 2: DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR PERSISTENT DEPRESSIVE DISORDER (APA 2013 P 168–169)

Defining and treating persistent, treatment resistant depression

The way forward in persistent, treatment resistant depression

The Practicality of theories: Defining a decision-making process

The conundrum of defining Shame as an affect

Cognitive-affective models of shame

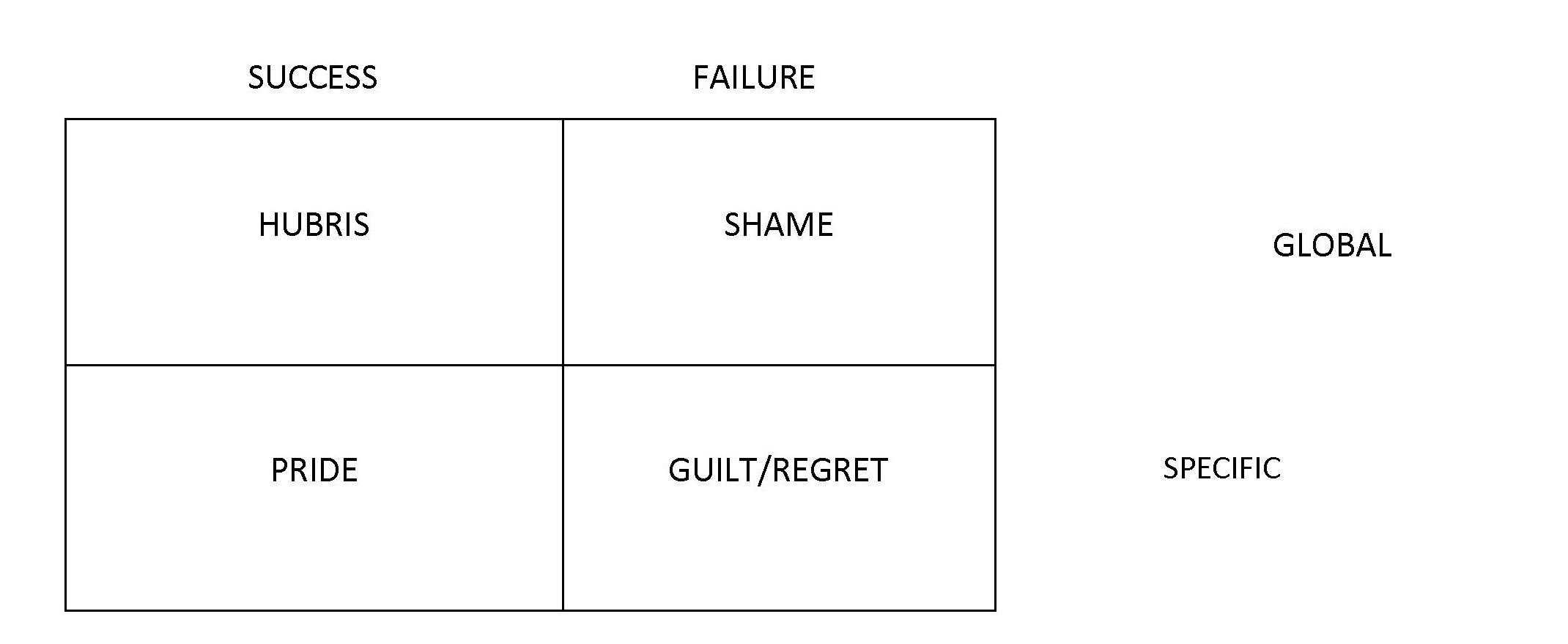

Cognitive-Attributional theories of shame

Lewis’ attributional theory of self-conscious emotions

Standards, Rules and Goals (SRG’s)

Internal versus external evaluations

Attributions about self: Global versus Specific

Step 1: Survival-Goal Relevance

Step 2: Attentional Focus on Self and Activation of Self-Representations

Step 3: Identity-Goal Relevance

Step 4: Identity-goal congruence

Step 5: Internality attributions

Step 6: Stability, Globality, controllability attributions

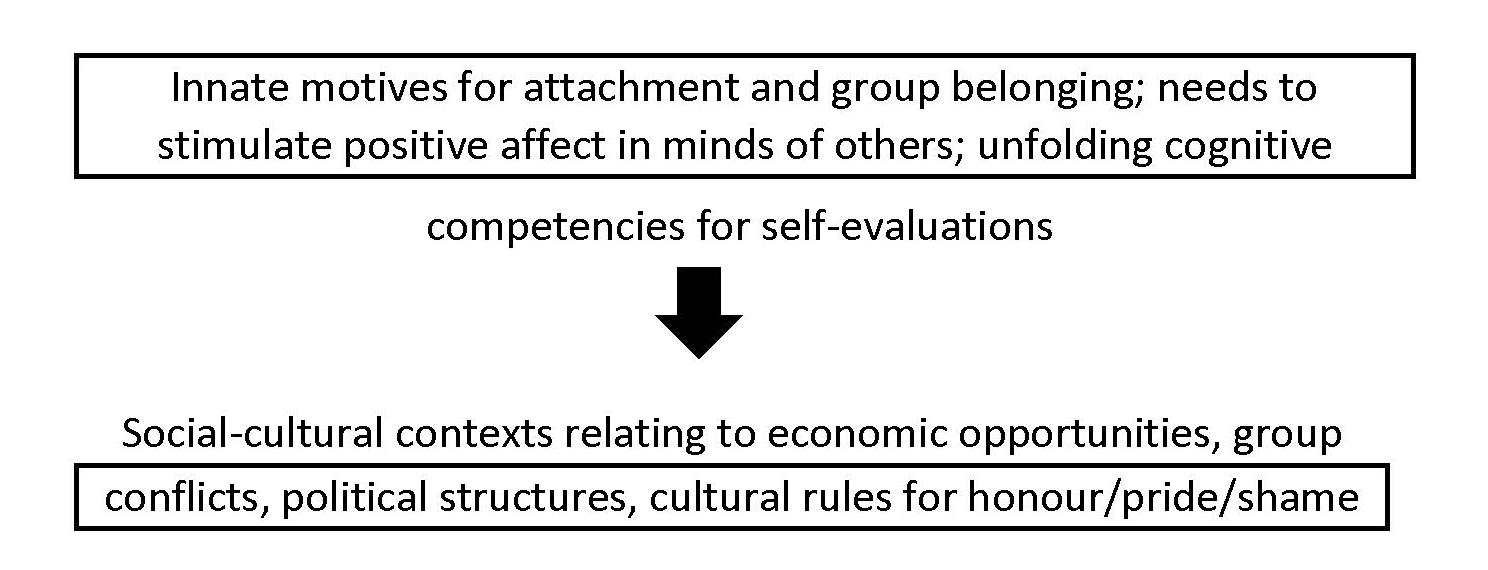

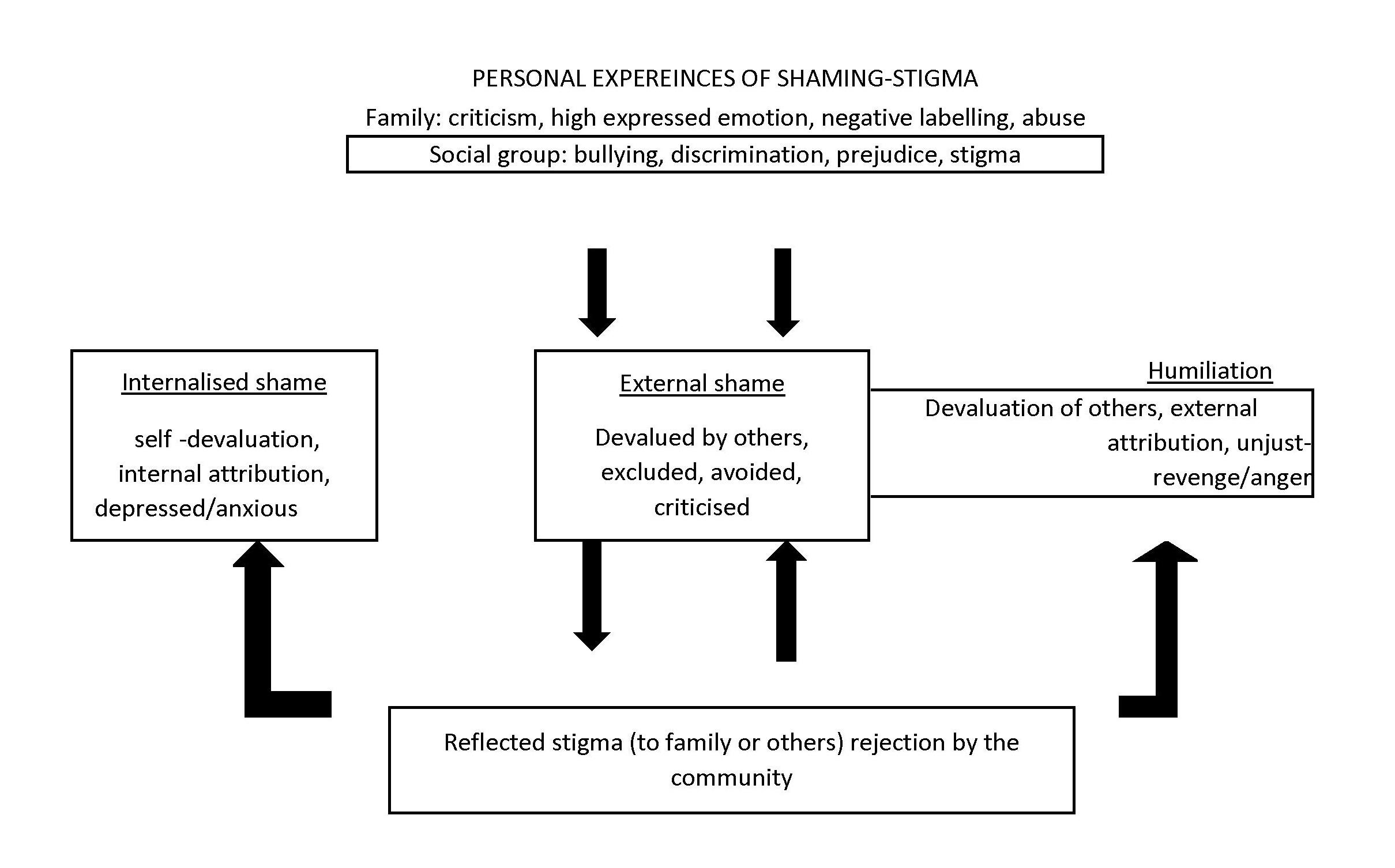

The evolutionary and biopsychosoical psychology model of shame

The definition of self-criticism

The psychoanalytic Formulation of Self-criticism

The Behavioural Formulation of Self-criticism

The cognitive formulation of self-criticism

The evolutionary formulation of self-criticism

Theories of the nature and origins of self-criticism and self-blame

Defining compassion and self-compassion

An evolutionary formulation of compassion

Compassion as an appraisal elicited emotion

Compassion as a motivational system

Self-kindness versus self-judgment

Common humanity versus isolation

Mindfulness versus over identification or avoidance

Examining the Practicality of these theories of shame using Brawley’s criteria

A critique of Gilbert’s theory of shame

Philosophical Pragmatism as an epistemological foundation

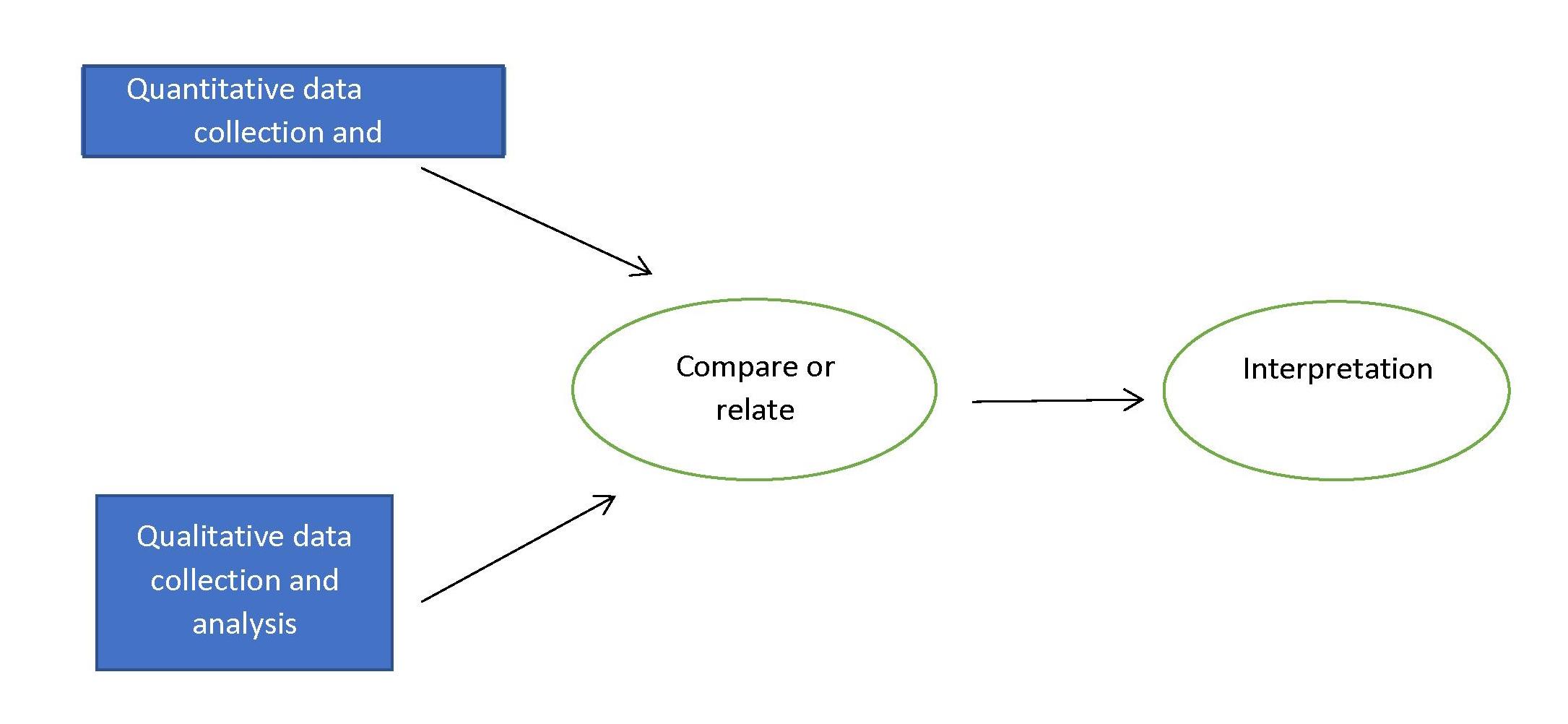

Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods

The power calculation in this PhD study

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the RCT

Step 1: Testing the psychometric status of OAS; FSCR and SCS

Rationale for chosen measures of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion

The forms of self-criticising/attacking and self-reassuring scale (FSCRS)

Step 2: Modelling variance in depressive symptoms against shame, self-criticism and selfcompassion

Rationale for chosen measures of depression

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HDRS-17)

Beck Depression Inventory-I (BDI-I)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Description of Qualitative Data Collection Method

TABLE 5: TYPES OF QUESTIONS FOR IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Establishing reliability and validity of the OAS, FSCR and SCS

Modelling variance of depression in relation to shame, self-criticism and self-compassion

An overview of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

The argument for epistemological coherence: The Primacy of Praxis revisited

Process for obtaining informed consent

Fieldwork and safety guidelines

Ethics Approval to conduct this research

Chapter 4 Quantitative Results

I. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis

The demographic profile of the study cohort

TABLE 6: DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY COHORT AT BASELINE

Descriptive Statistics for Other as Shamer Scale (OAS) baseline

TABLE 10: SUMMARY STATISTICS FOR OAS AT BASELINE

TABLE 11: DISTRIBUTION FOR EACH SUB-SCALE OF OAS AT BASELINE

TABLE 12: CRONBACH’S ALPHA SCORES AT BASELINE FOR OAS SCALE

TABLE 13: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE INFERIOR AT BASELINE

TABLE 14: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE INFERIOR AT BASELINE

TABLE 15: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE EMPTINESS AT BASELINE

TABLE 16: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATION FOR SUB-SCALE EMPTINESS AT BASELINE

TABLE 17: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE MISTAKES AT BASELINE

TABLE 18: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATION FOR SUB-SCALE MISTAKES AT BASELINE

Split-Half Reliability for OAS at baseline

TABLE 19: SUMMARY ITEM MEANS STATISTICS FOR OAS AT BASELINE

Test-retest reliability for OAS at baseline and 6 months

TABLE 21: TEST-RETEST RELIABILITY FOR OAS AT BASELINE AND 6 MONTHS

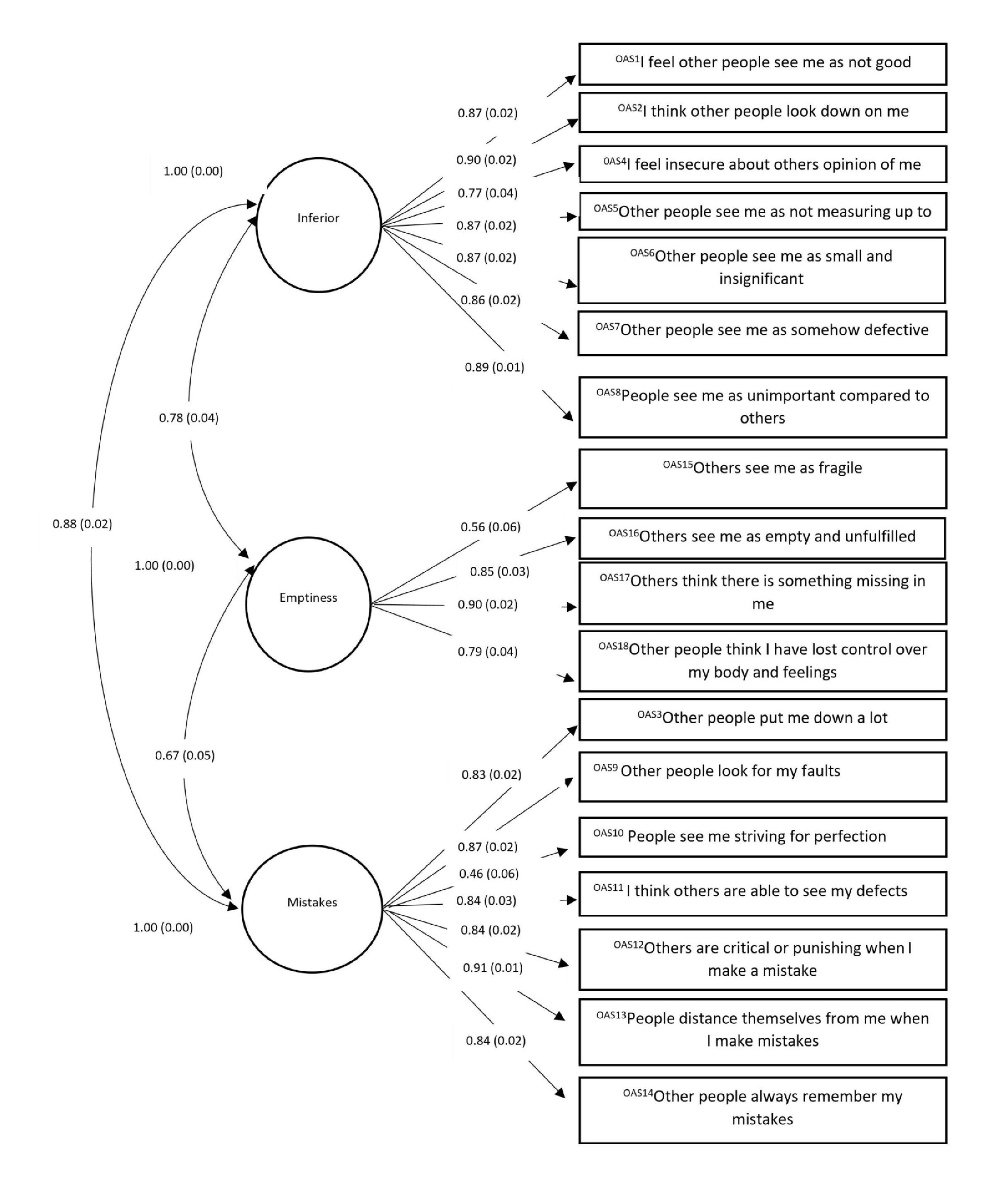

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

TABLE 22: THE CONTINUOUS LATENT VARIABLES AND INDICATORS TESTED FOR OAS, FSCSR AND SCS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Other as Shamer Scale

FIGURE 6: CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS PATH DIAGRAM FOR THE OTHER AS SHAMER SCALE (OAS)

Descriptive Statistics for Forms of Self-Criticising Self -Reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

TABLE 24: SUMMARY STATISTICS FOR FSCSR AT BASELINE

TABLE 25: DISTRIBUTION FOR EACH SUB-SCALE OF FSCSR AT BASELINE

TABLE 26: CRONBACH’S ALPHA FOR FSCSR AT BASELINE

TABLE 27: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE INADEQUATE SELF AT BASELINE

TABLE 28: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATION FOR SUB-SCALE INADEQUATE SELF AT BASELINE

TABLE 29: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE HATED SELF AT BASELINE

TABLE 30: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATION FOR SUB-SCALE HATED SELF AT BASELINE

TABLE 31: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE REASSURED SELF AT BASELINE

TABLE 33: SUMMARY ITEM MEANS STATISTICS FOR FSCSR AT BASELINE

TABLE 34: SPLIT HALF RELIABILITY SCALE STATISTICS FOR FSCSR AT BASELINE

Test-retest reliability for FSCSR at baseline and 6 months

TABLE 35: TEST -RETEST RELIABILITY FOR FSCSR BETWEEN BASELINE AND 6 MONTHS

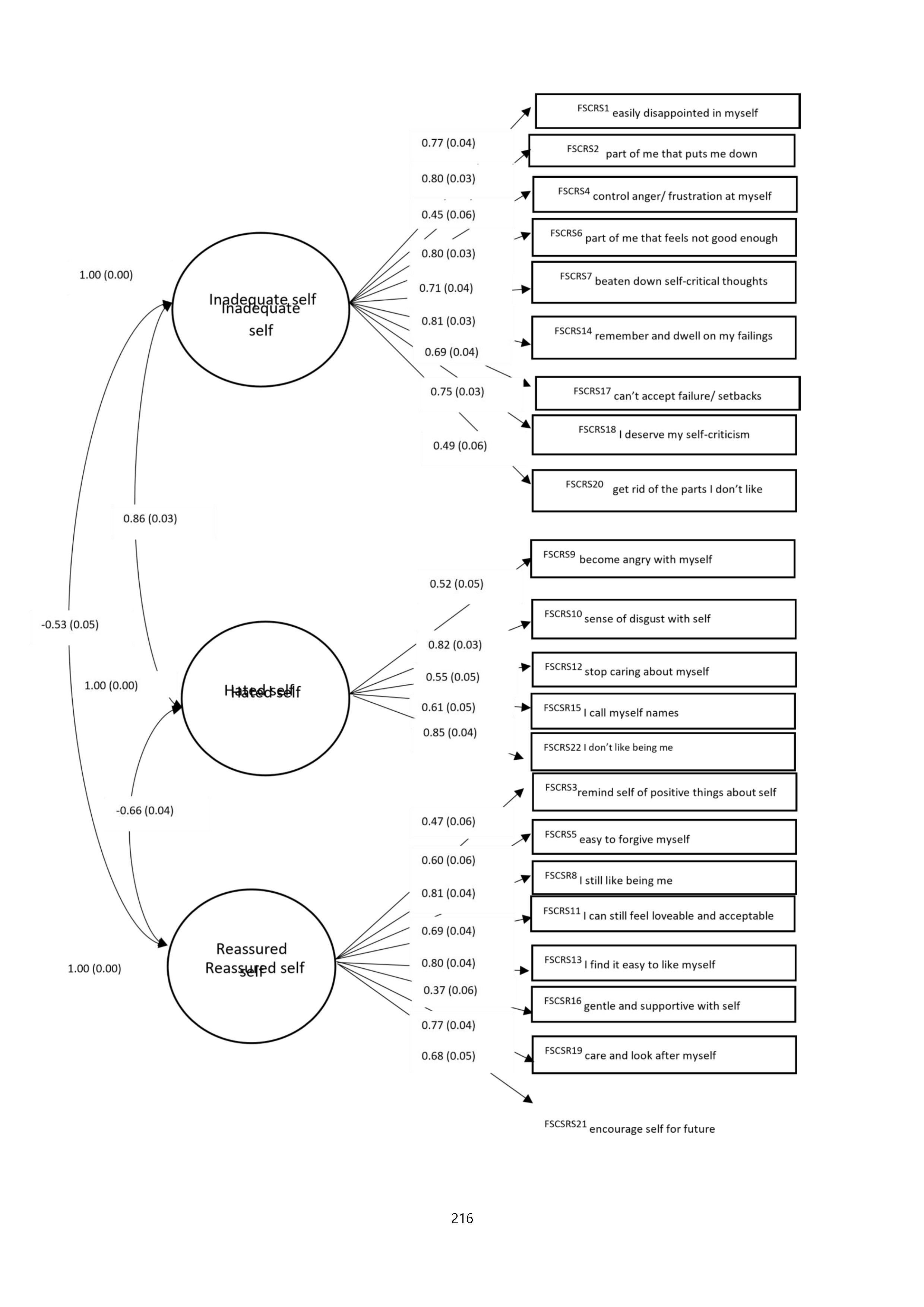

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Forms of Self-Criticism and self-Reassurance Scale (FSCSR)

TABLE 36: MODEL FIT INDICES FOR FSCSR

Descriptive Statistics for Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) baseline

TABLE 37: SUMMARY STATISTICS FOR SELF-COMPASSION SCALE (SCS) AT BASELINE

TABLE 38: DISTRIBUTION FOR EACH SUB-SCALE OF SCS AT BASELINE

TABLE 39: CRONBACH’S ALPHA FOR SCS AT BASELINE

TABLE 40: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE SELF-KINDNESS AT BASELINE

TABLE 41: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATION FOR SUB-SCALE SELF-KINDNESS AT BASELINE

TABLE 42: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE SELF-JUDGMENT AT BASELINE

TABLE 43: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATIONS FOR SUB-SCALE SELF-JUDGEMENT AT BASELINE

TABLE 44: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE COMMON HUMANITY AT BASELINE

TABLE 45: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATIONS FOR SUB-SCALE COMMON HUMANITY AT BASELINE

TABLE 46: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE ISOLATION AT BASELINE

TABLE 47: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATIONS FOR SUB-SCALE ISOLATION AT BASELINE

TABLE 48: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE MINDFULNESS AT BASELINE

TABLE 49: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATIONS FOR SUB-SCALE MINDFULNESS AT BASELINE

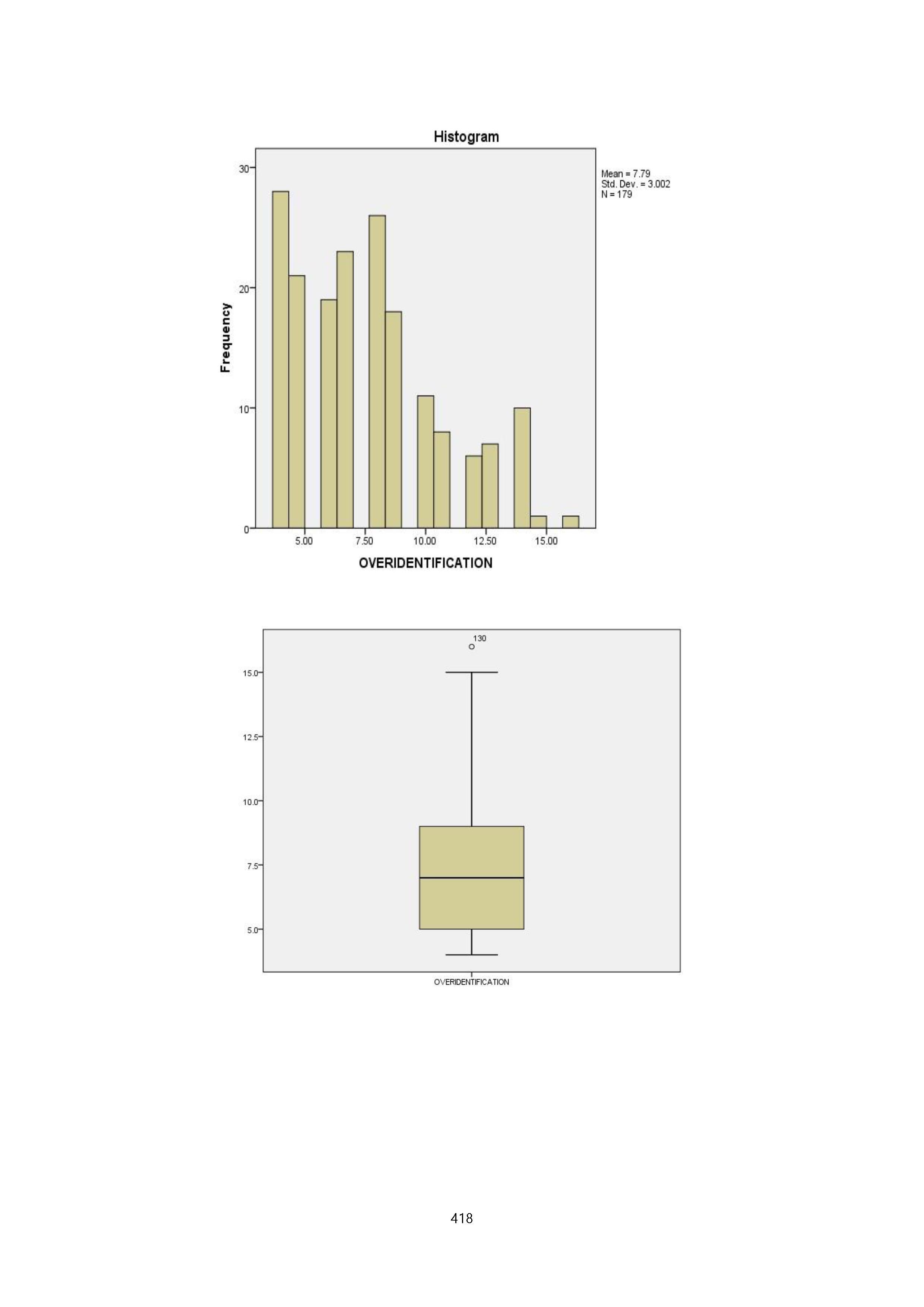

TABLE 50: ITEM STATISTICS FOR SUB-SCALE OVERIDENTIFICATION AT BASELINE

TABLE 51: ITEM TO ITEM CORRELATIONS FOR SUB-SCALE OVERIDENTIFICATION AT BASELINE

TABLE 52: SUMMARY ITEM MEANS FOR SCS AT BASELINE

TABLE 53: SPLIT HALF RELIABILITY SCALE STATISTICS FOR SCS AT BASELINE

Test-retest reliability for SCS at baseline

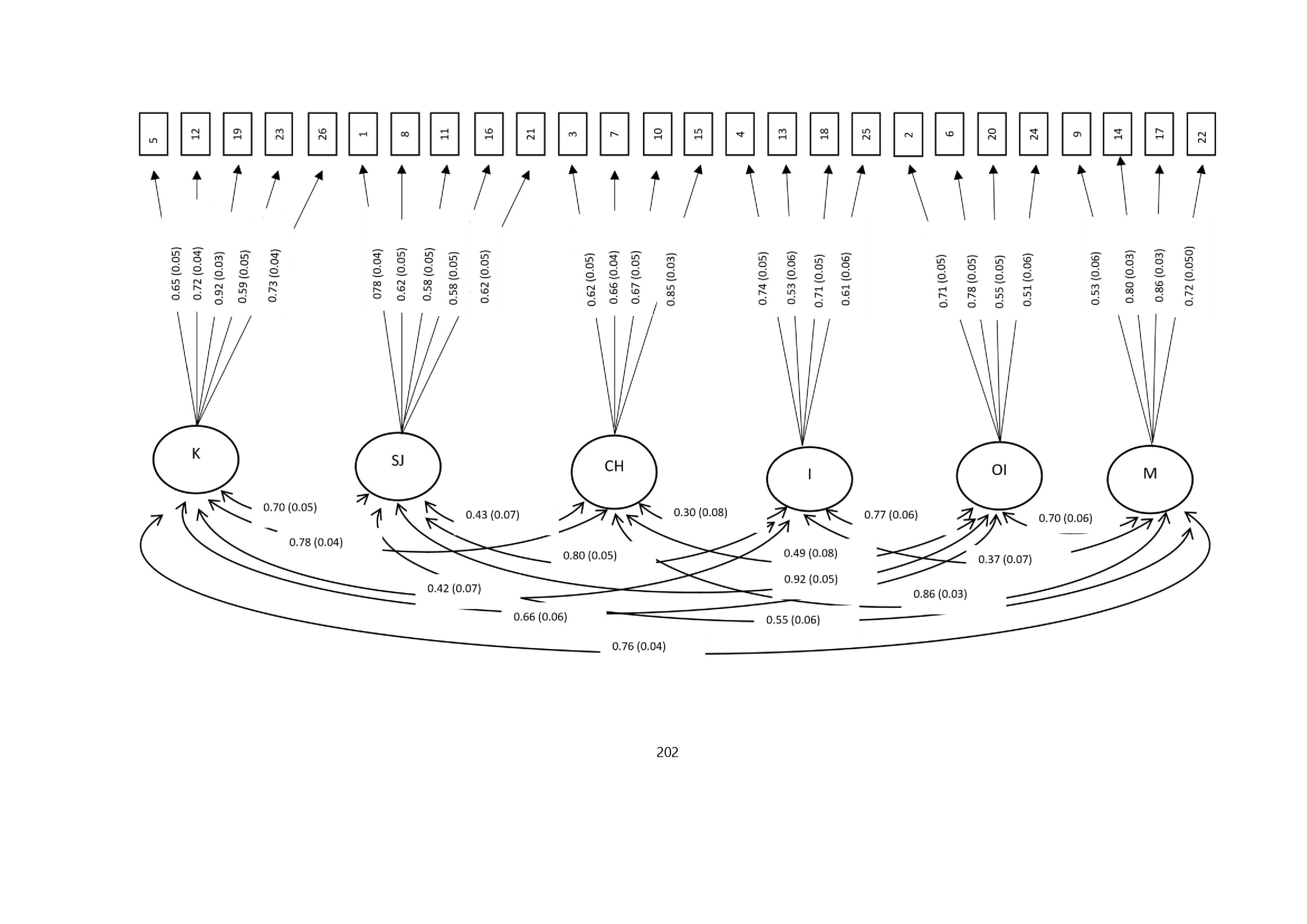

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for SCS

TABLE 55: MODEL FIT INDICES FOR SCS

TABLE 57: INFLUENCE OF OAS, FSCSR AND SCS ON BDI-I UNIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIATE REGRESSION MODELLING

TABLE 58: INFLUENCE OF OAS, FSCSR AND SCS ON PHQ-9 UNIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIATE REGRESSION MODELLING

TABLE 59: DEFINITION OF ‘COGNITION’ WITHIN IPA

Emergent themes and sub-themes in the qualitative data

1. Childhood adversity and social milieu

3. The function of self-criticism 4. Absence of self-compassion

1. Childhood adversity and the social milieu

Reluctance to speak about childhood

I. Not good enough/inferior/failure-self-criticism

ii. unimportant/not counting/not worthy-self-blame

iii. Bad/inadequate/insignificant/worthless: self-hate/loathing

3. The function of self-criticism/self-hating

i. Intellectual appreciation with good intentions

ii. Not understood/incomprehension

7. Memory and information processing biases in depression

Examination of the psychometric properties of the OAS, FSCSR and SCS in the study cohort

Suggested revisions to the OAS

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the OAS

Examination of the FSCSR and its sub-scales in relation to persistent treatment resistant depression

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the FSCSR

Examination of the SCS by sub-scale in relation to persistent treatment resistant depression

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the SCS

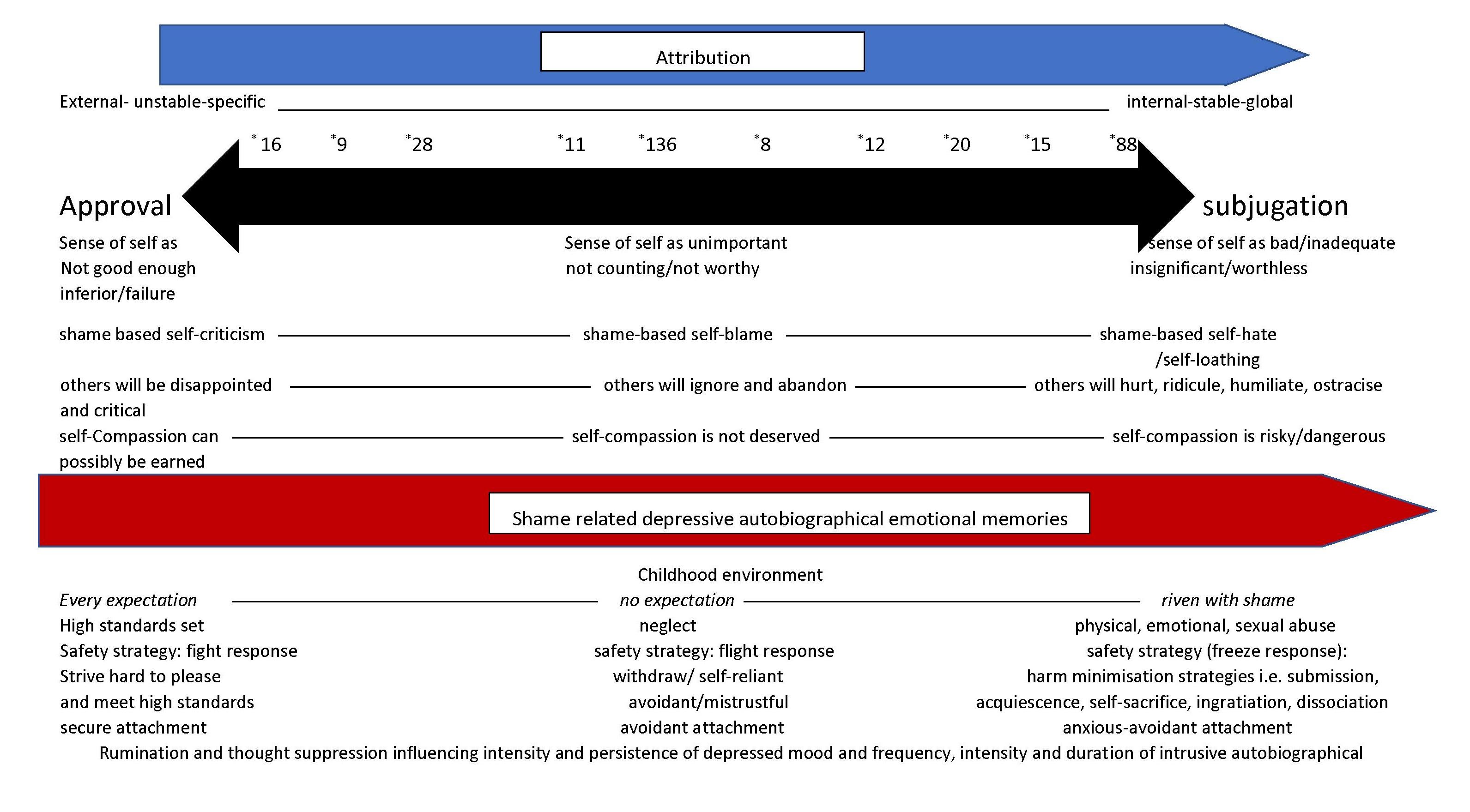

evolutionary biopsychosocial model

Defining the parameters of approval and subjugation

Shame of not meeting expectation: Every expectation

Shame, ridicule and humiliation: No expectation

Riven with shame: trapped and defeated

Clinical implications of these findings and avenues for future research

Frost, J. (2019). Regression Analysis: An Intuitive Guide for Using and Interpreting Linear

Health Research Authority (HRA) (2015) East Midlands-Nottingham Research Ethics

Appendix III: Proposed criteria for Multiple-Therapy-Resistant (MTR) Major Depressive Disorder

Appendix VI: Theories of shame measured against Brawley’s (1993) Practicality of a theory criteria

Appendix VII: Consort diagram of participant flow through RCT

Appendix VIII: Email invitation to participate as a healthy control in the study

Appendix IX: Healthy Controls: Screening Questionnaire Introduction and Background Information

Invitation to take part in the study

Involvement of the General Practitioner/Family doctor (GP)

Appendix XII: Other as Shamer Scale

Appendix: XIII: The Forms of Self-Criticising and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

Appendix XIV: Self Compassion Scale (SCS)

Appendix XV: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17</strong> (Hamilton, 1960)

Appendix XVI: Beck Depression Inventory-I (BDI-I)

Appendix XVII: The Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Appendix XVIII: Qualitative Interview Topic Guide

Background information and rapport building

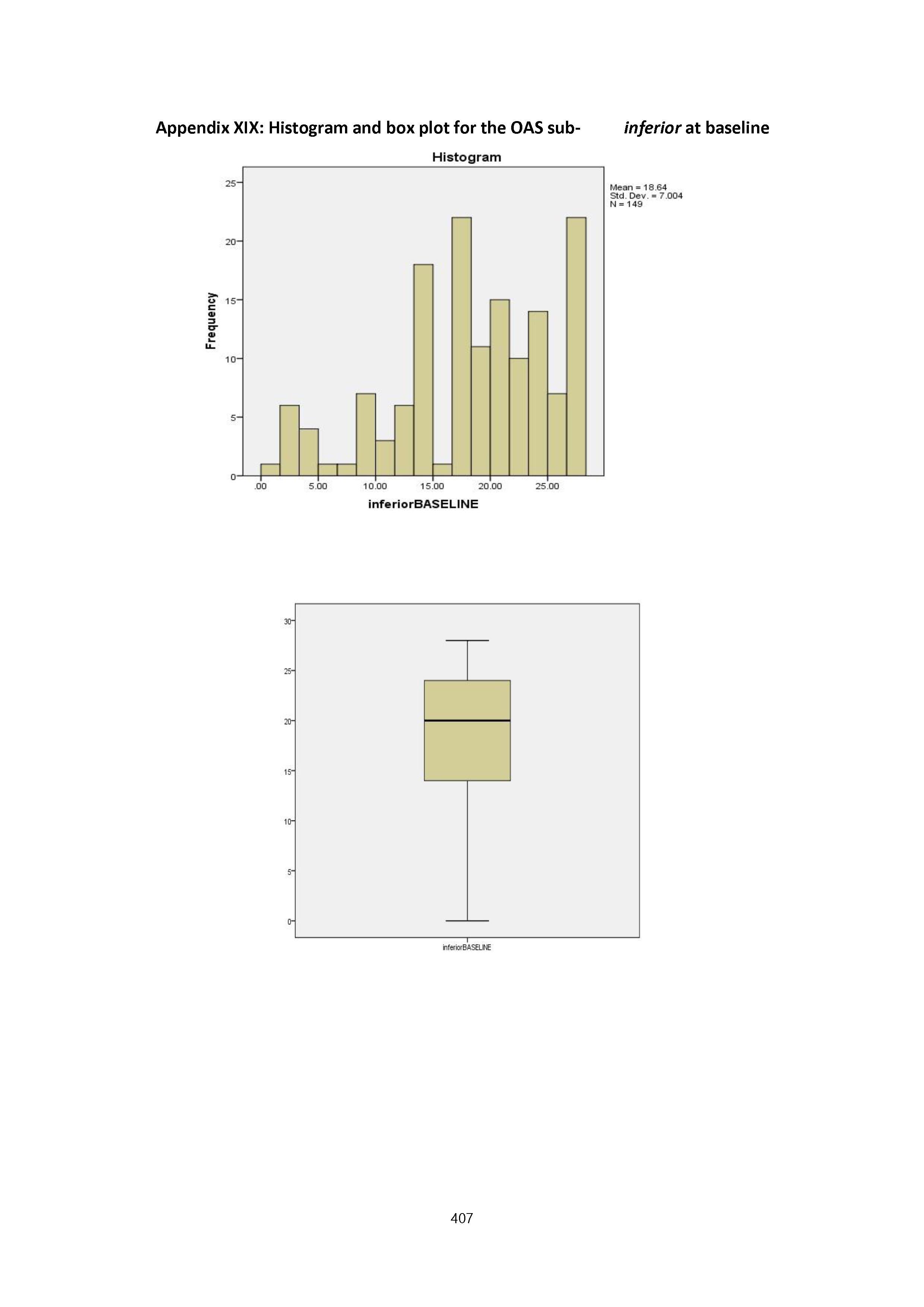

Appendix XIX: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub- inferior at baseline

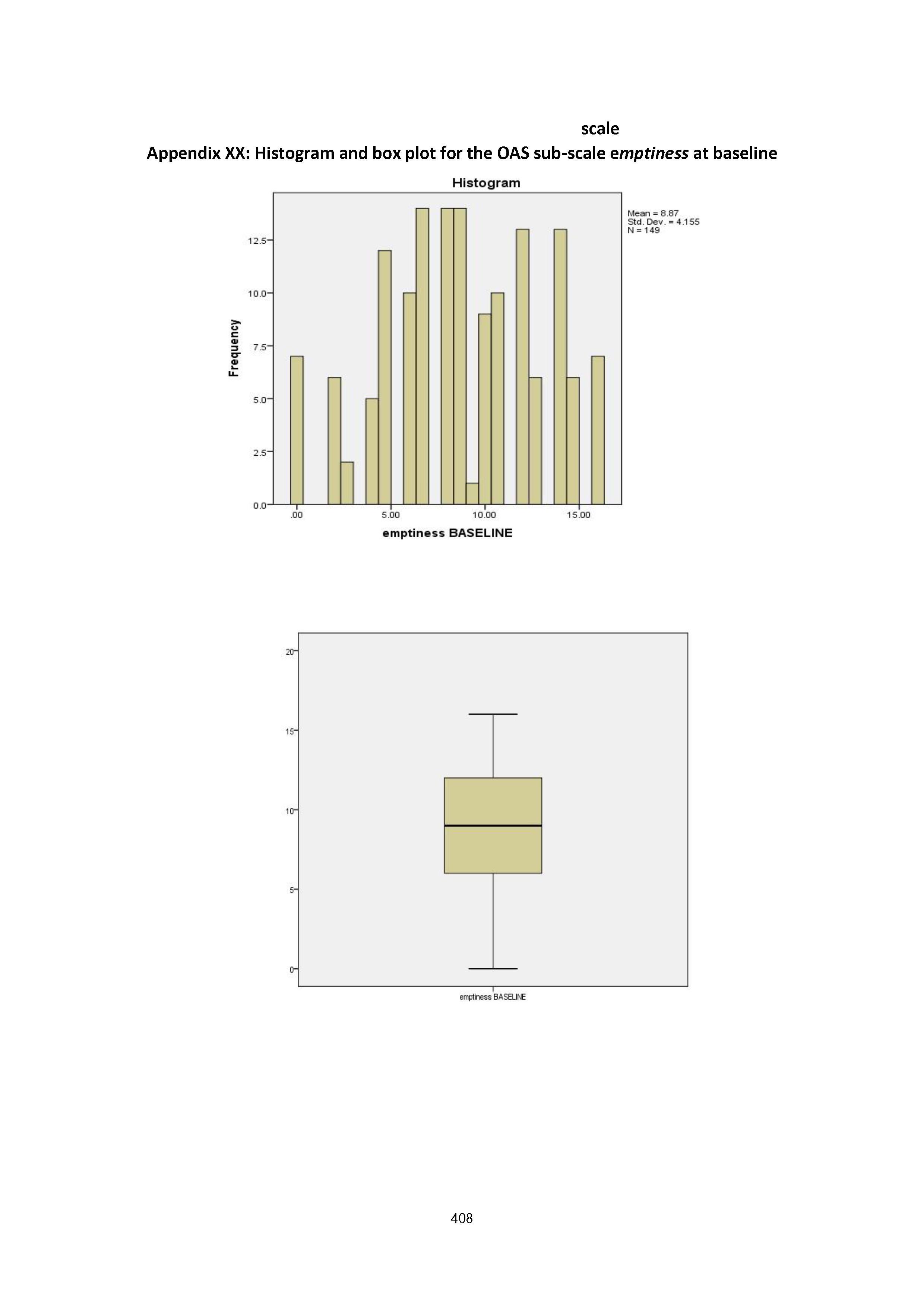

Appendix XX: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub-scale emptiness at baseline

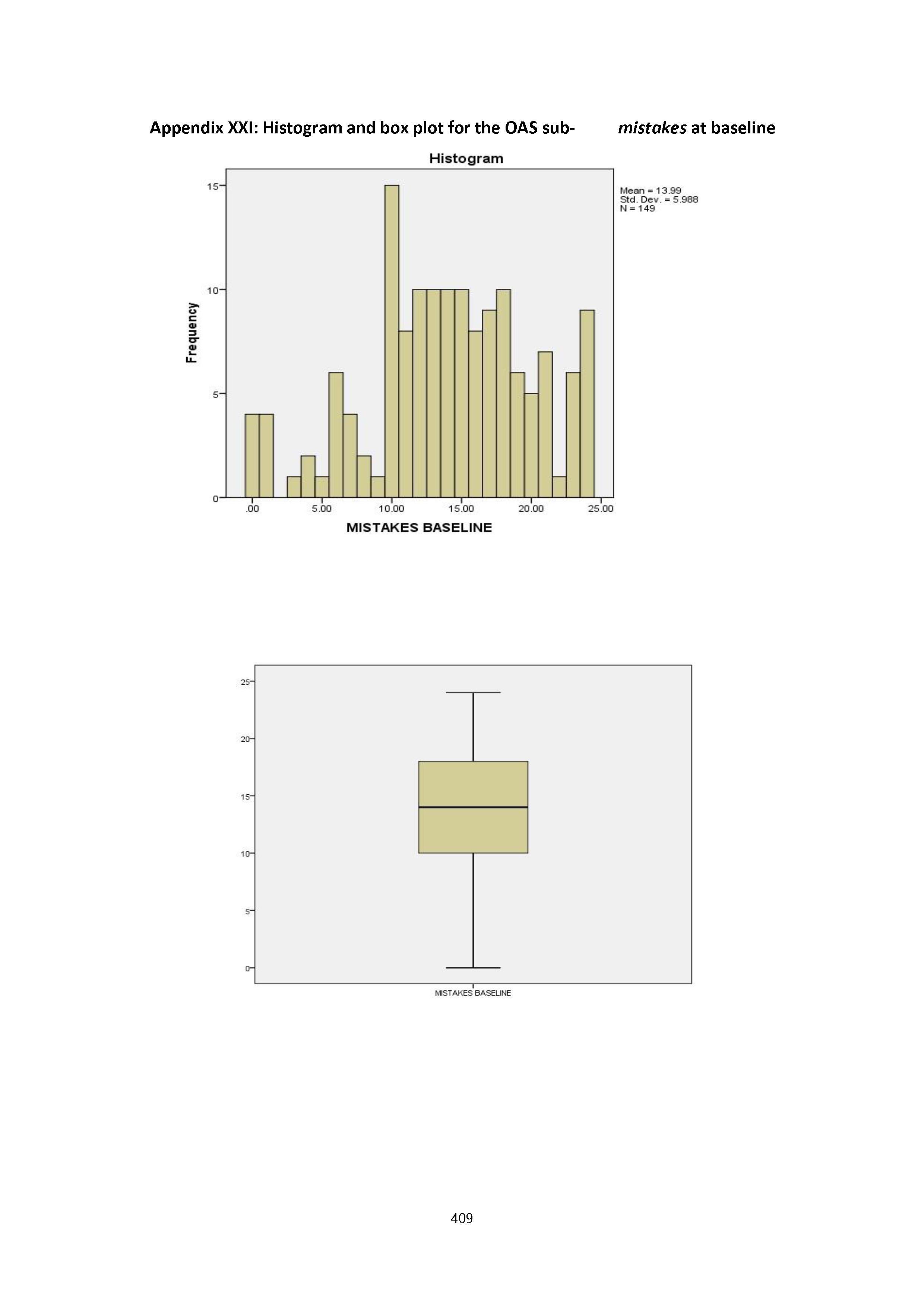

Appendix XXI: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub- mistakes at baseline

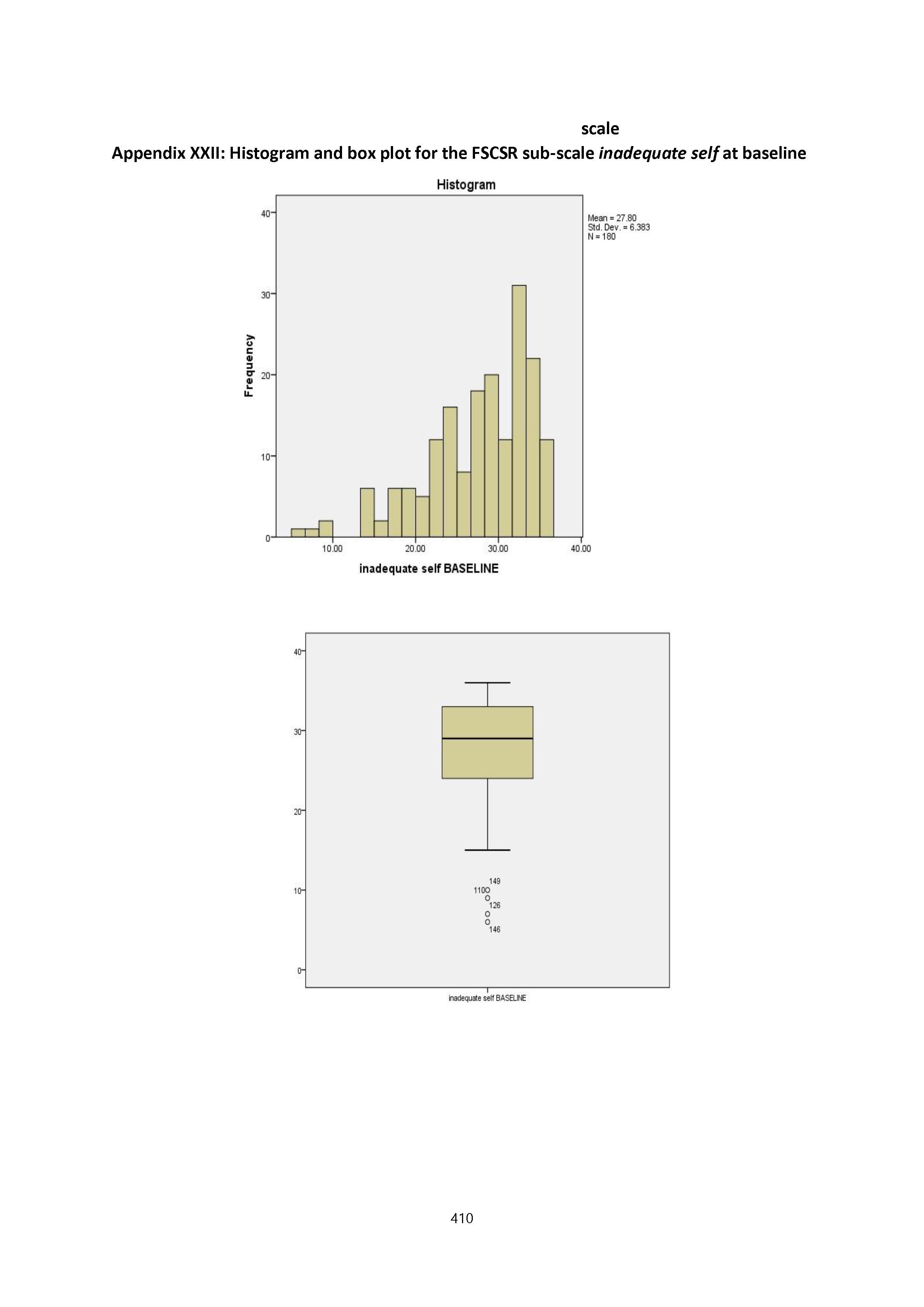

Appendix XXII: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub-scale inadequate self at baseline

Appendix XXIII: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub- hated self at baseline

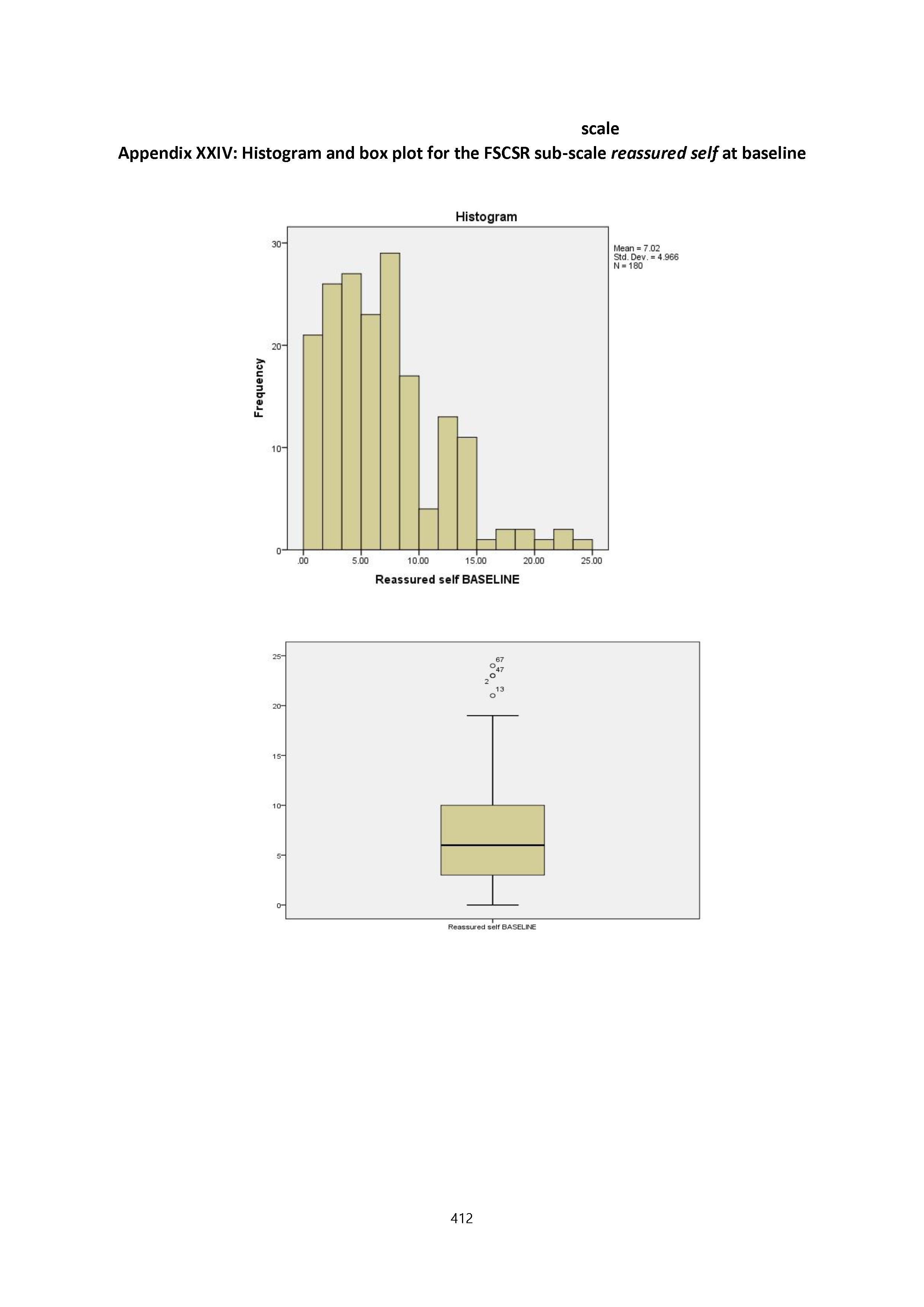

Appendix XXIV: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub-scale reassured self at baseline

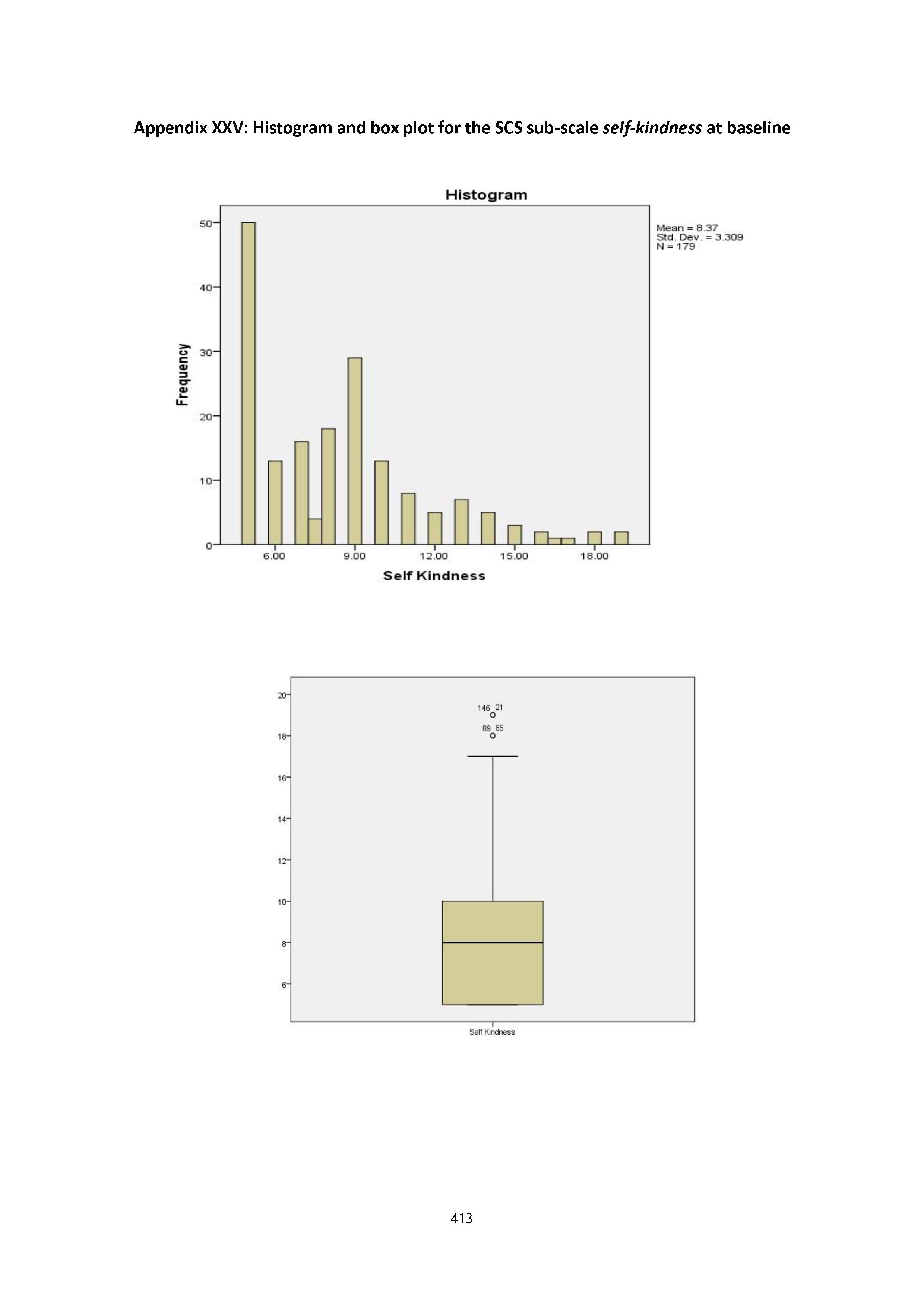

Appendix XXV: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale self-kindness at baseline

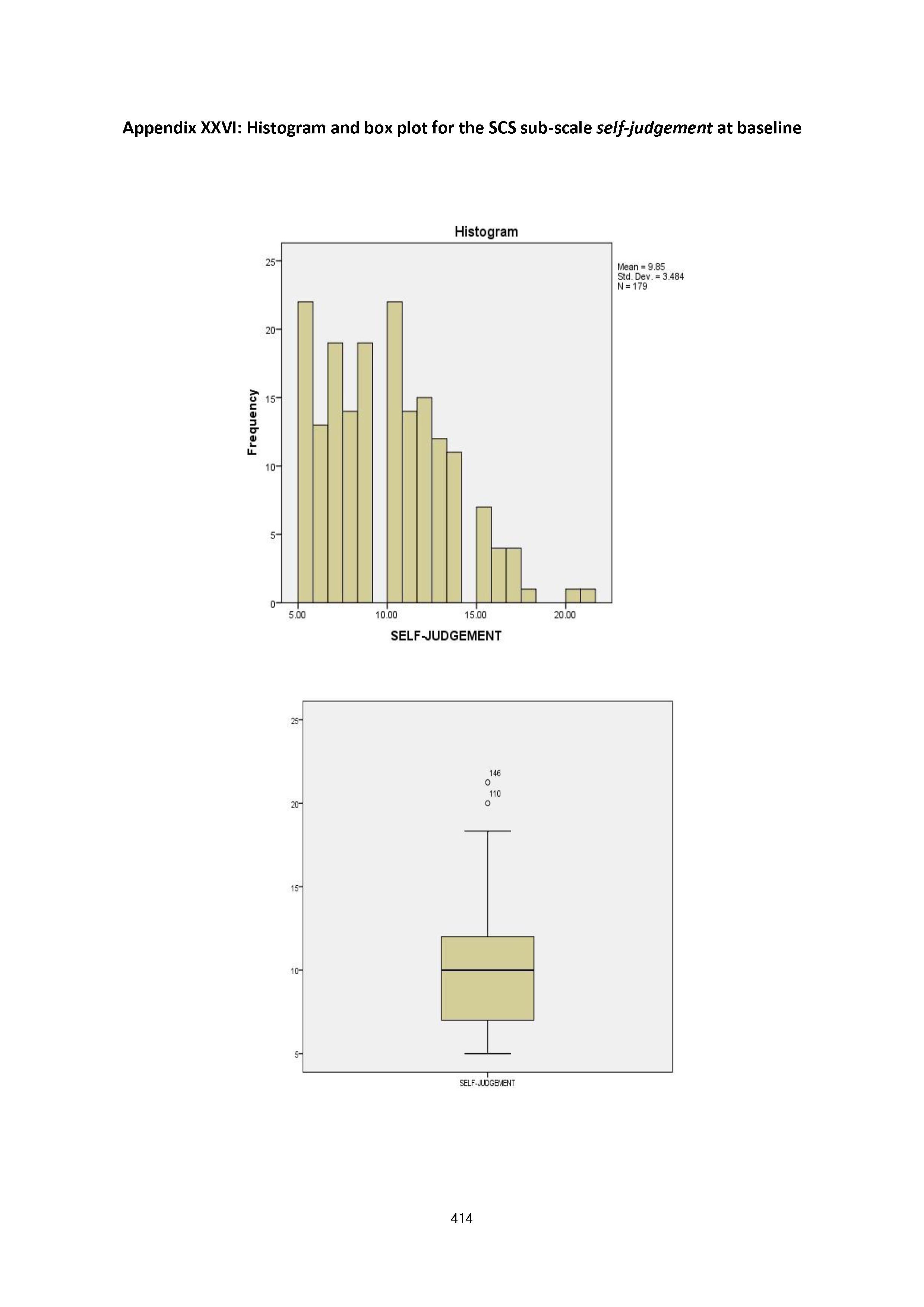

Appendix XXVI: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale self-judgement at baseline

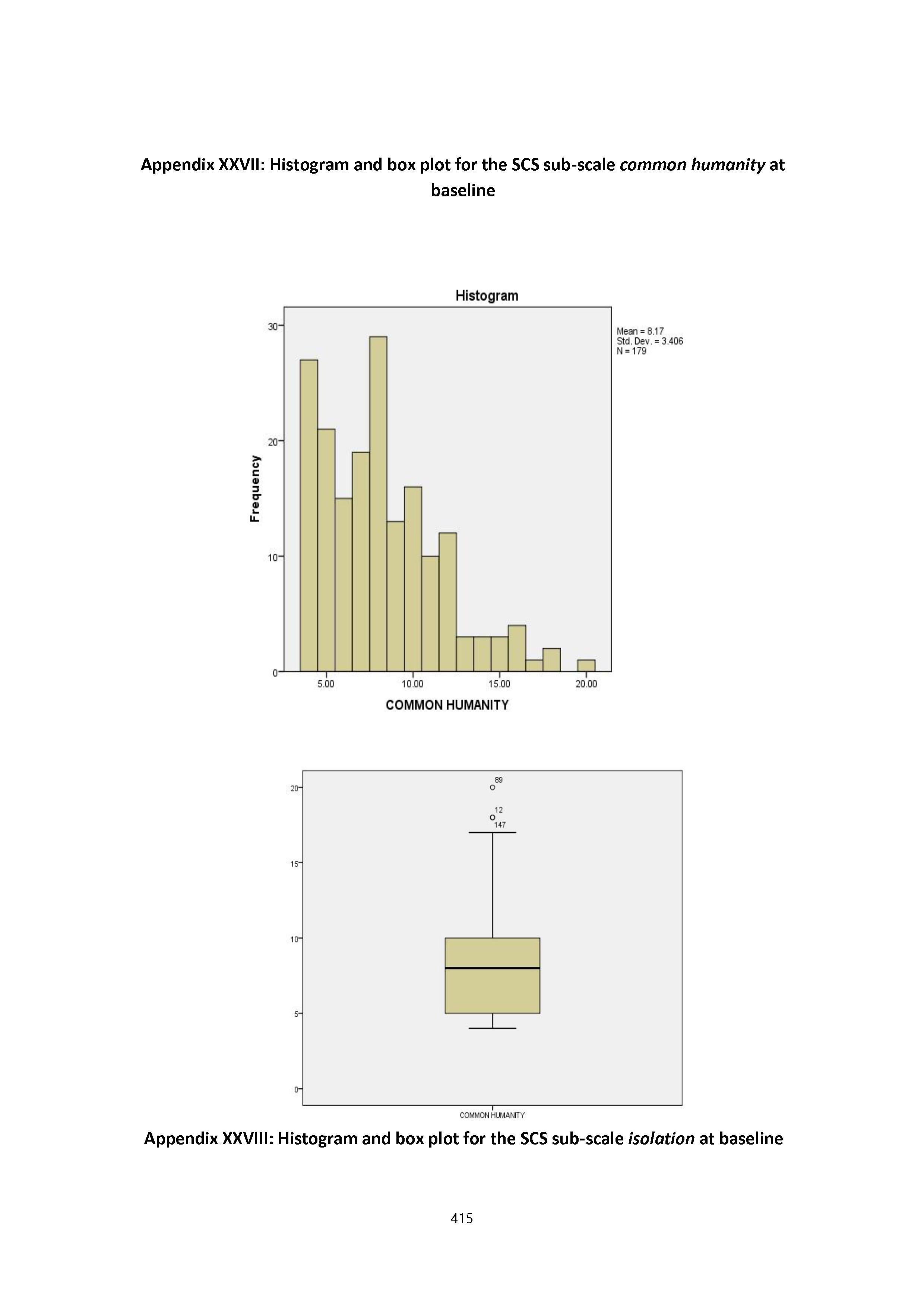

Appendix XXVII: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale common humanity at baseline

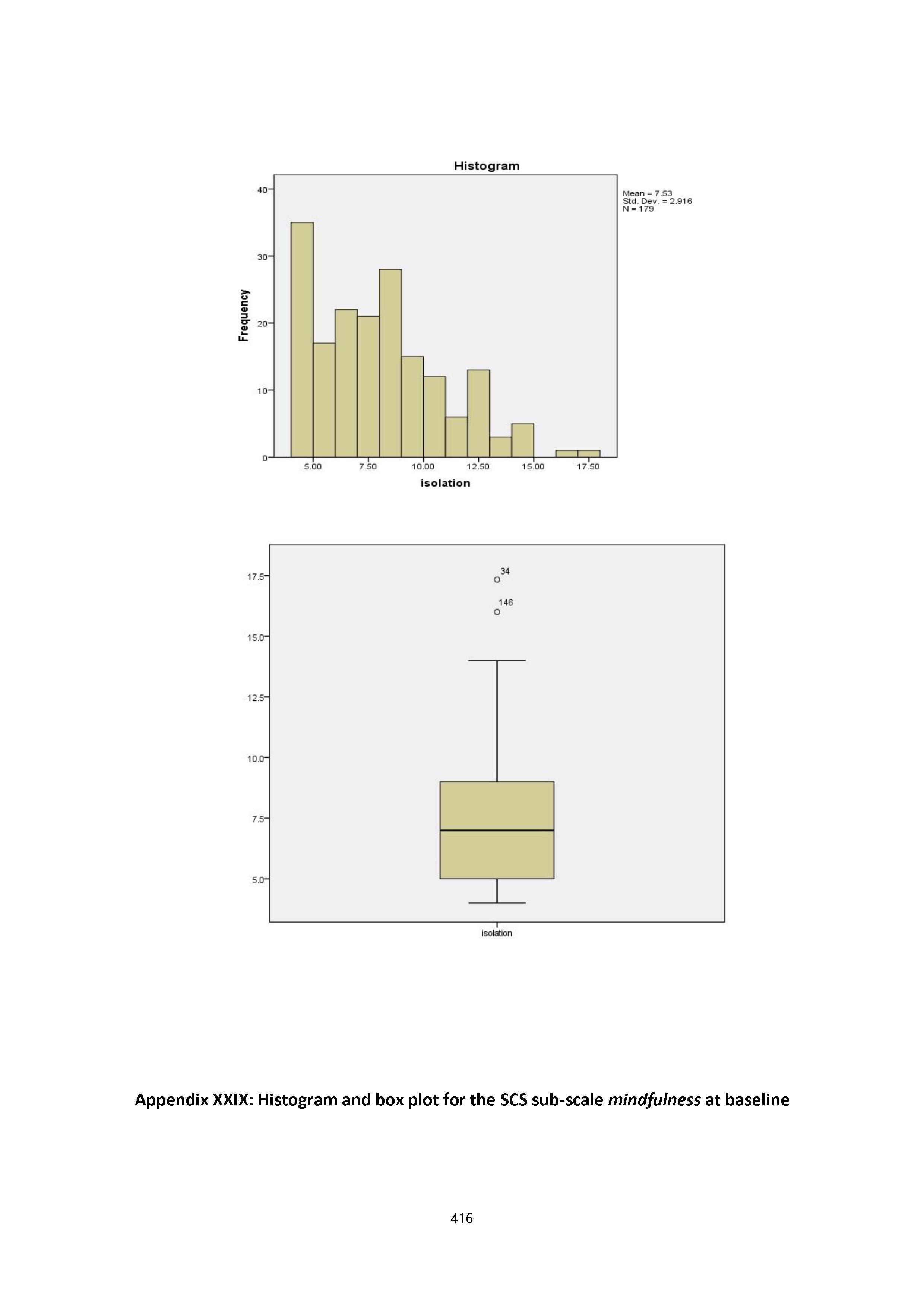

Appendix XXVIII: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale isolation at baseline

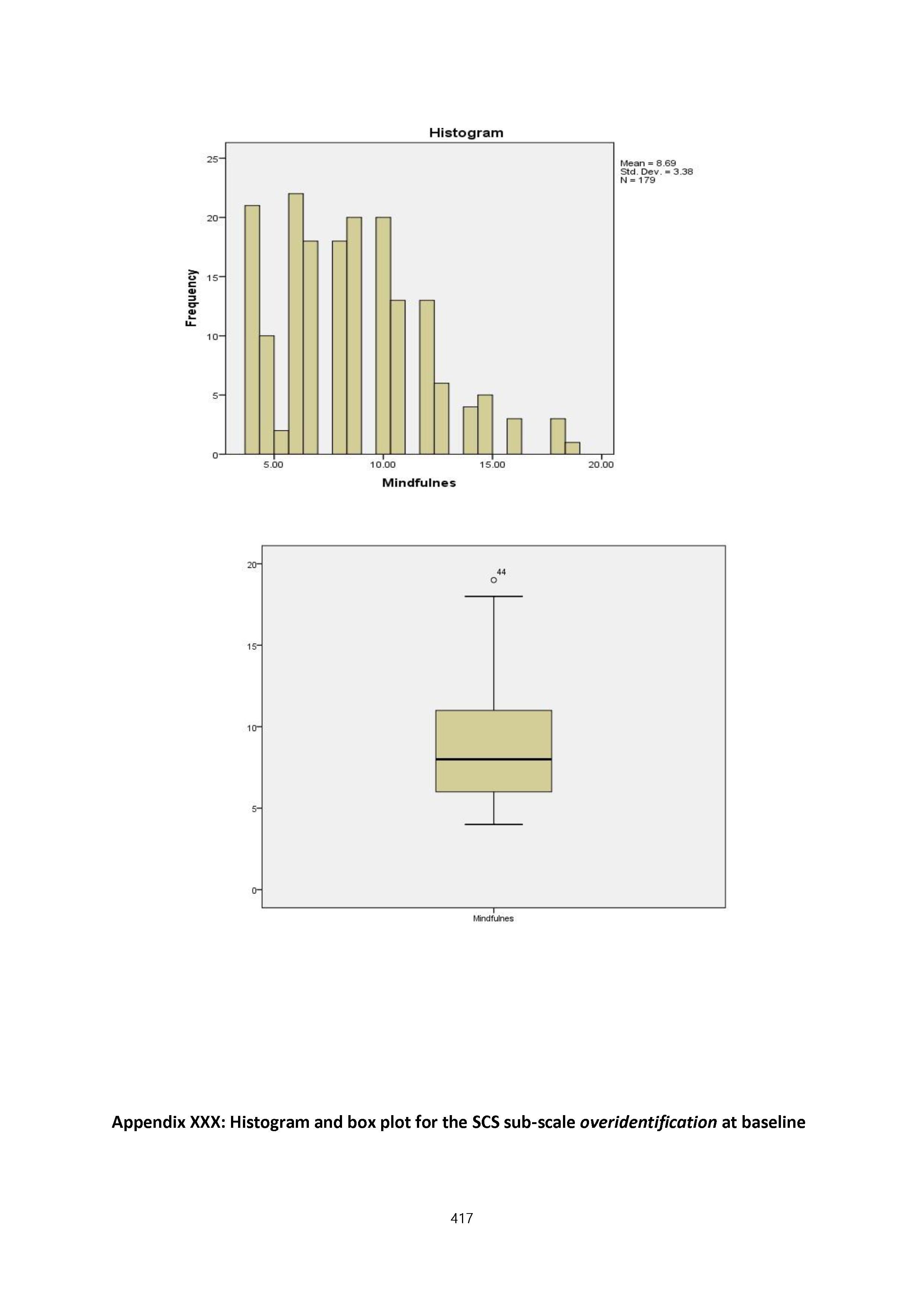

Appendix XXIX: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale mindfulness at baseline

Appendix XXX: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale overidentification at baseline

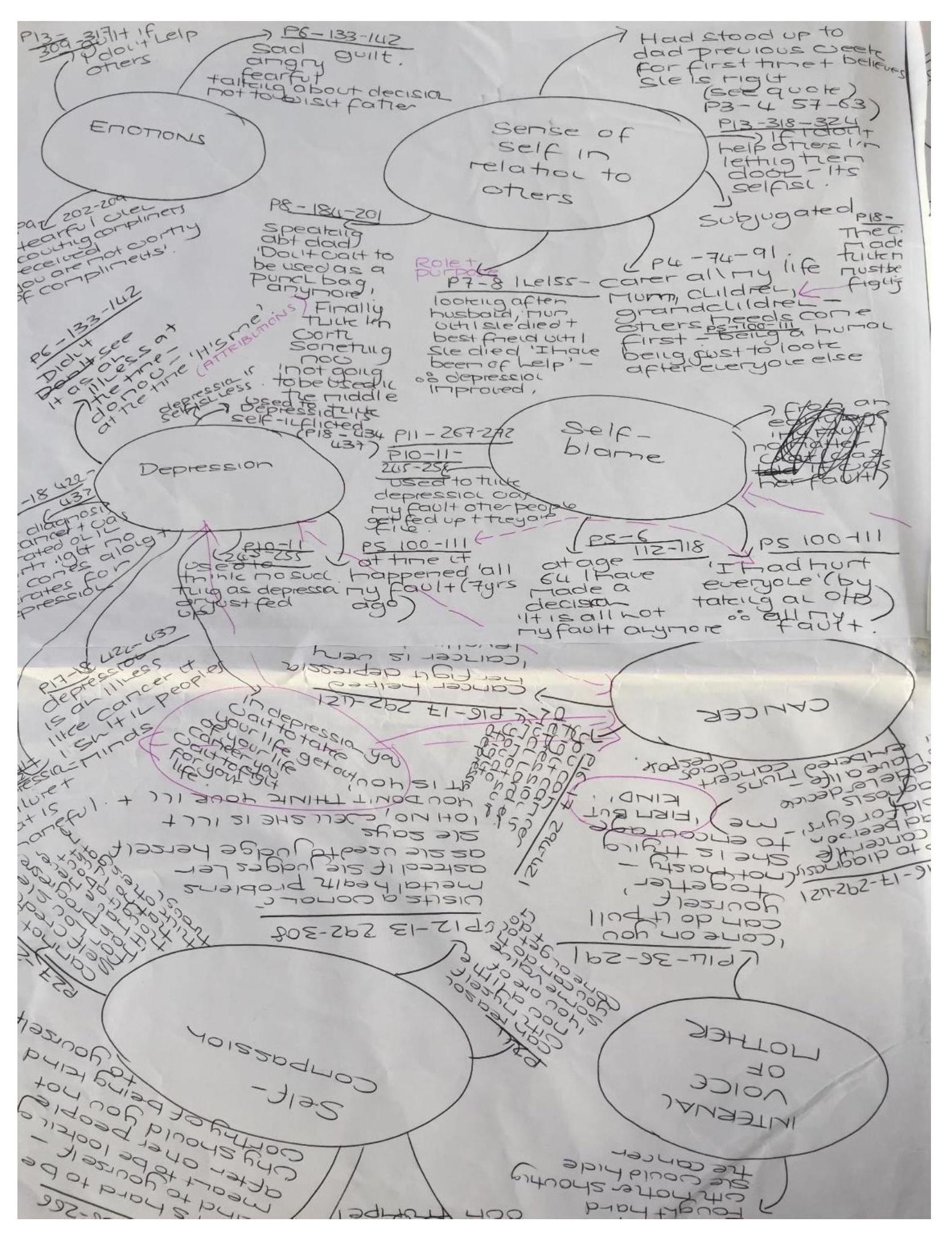

Appendix XXXI: Example of steps of qualitative data analysis (participant 12)

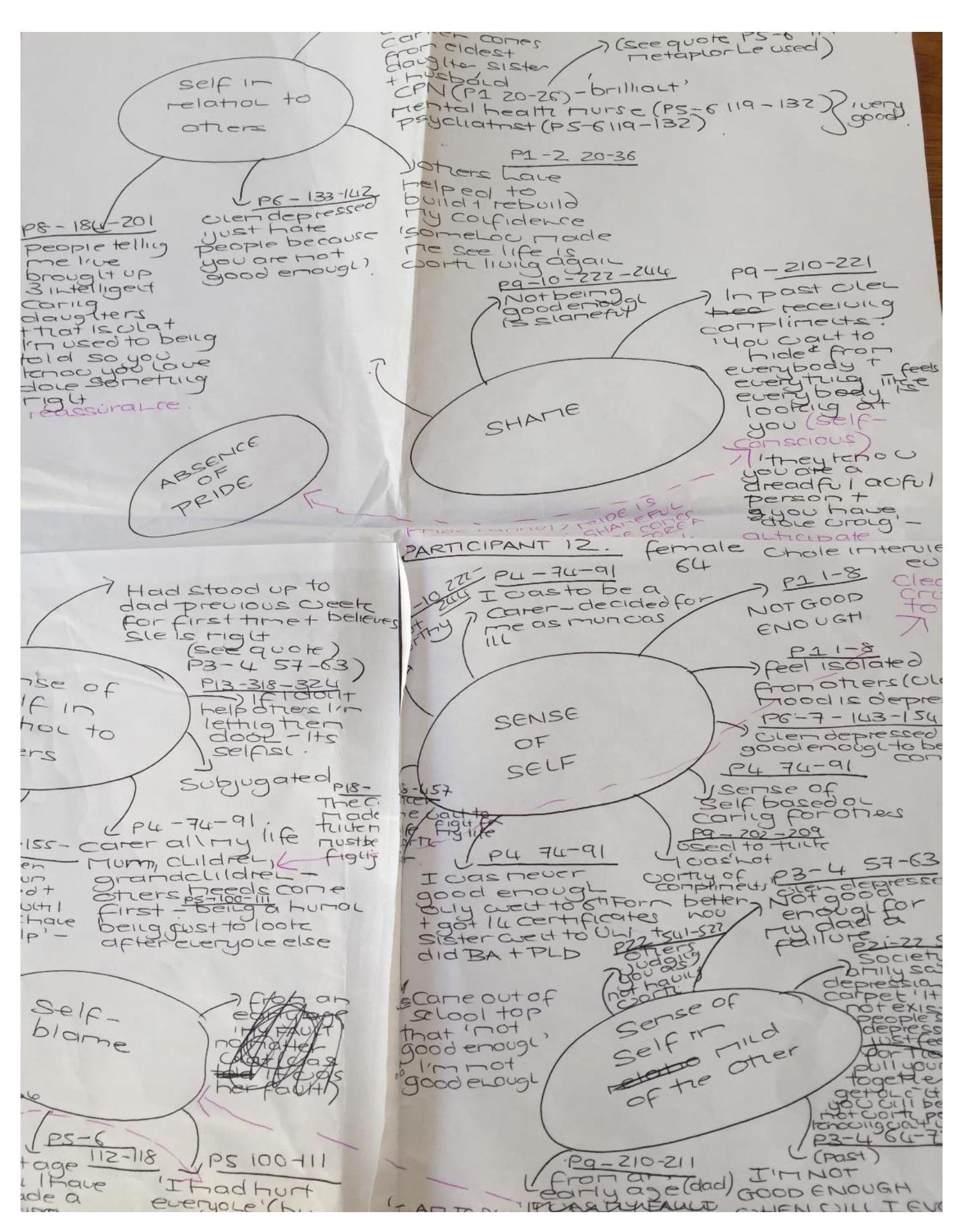

Appendix XXXII: Photographs of an example of a mind map (participant 12)

Appendix XXXIII: Biographies of participants in qualitative arm of this PhD study

Appendix XXXIV: The subscales and items of the OAS

Appendix XXXV: The sub-scales and items of the FSCSR

Abstract

Background

In 2017 the World Health Organisation (WHO), declared depression to be the leading cause of disability adjusted life years lost due to ill-health. Further, it is well established in the research literature that depression is a relapsing illness. In using Cognitive -Behavioural Therapy (CBT) with patients diagnosed with persistent, treatment resistant depression two clinical observations underpin this thesis. Firstly, that shame and self-criticism are key features of depression and secondly that standard Beckian CBT interventions have limited impact in tackling shame and self-criticism in this patient group. Integrating Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) with CBT interventions results in some amelioration of shame and selfcriticism, but this is limited empirically.

Aim

To examine shame, self-criticism and self-compassion in persistent, treatment resistant depression using the framework of Gilbert’s evolutionary psycho-biosocial formulation of emotional disorders.

Methods

Using a convergent parallel mixed methods design, the present study investigated the psychometric properties of three measures: the Other as Shamer Scale (OAS), Forms of SelfCriticism and Self-Reassurance Scale (FSCSR) and the Self Compassion Scale (SCS) in a sample recruited from a large National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT). Internal consistency and test-retest reliability were assessed, and construct validity examined with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Univariate and multivariate statistical analysis was conducted to test the degree to which levels of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion varied according to level of depression as measured on three well validated measures of depression. In addition, using semi-structured interviews, a subset of participants (n=10) from the Treatment as Usual Arm (TAU) of the RCT cohort were interviewed to explore their lived experience of depression, shame, self-criticism and selfcompassion. Interview data was analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).

Findings

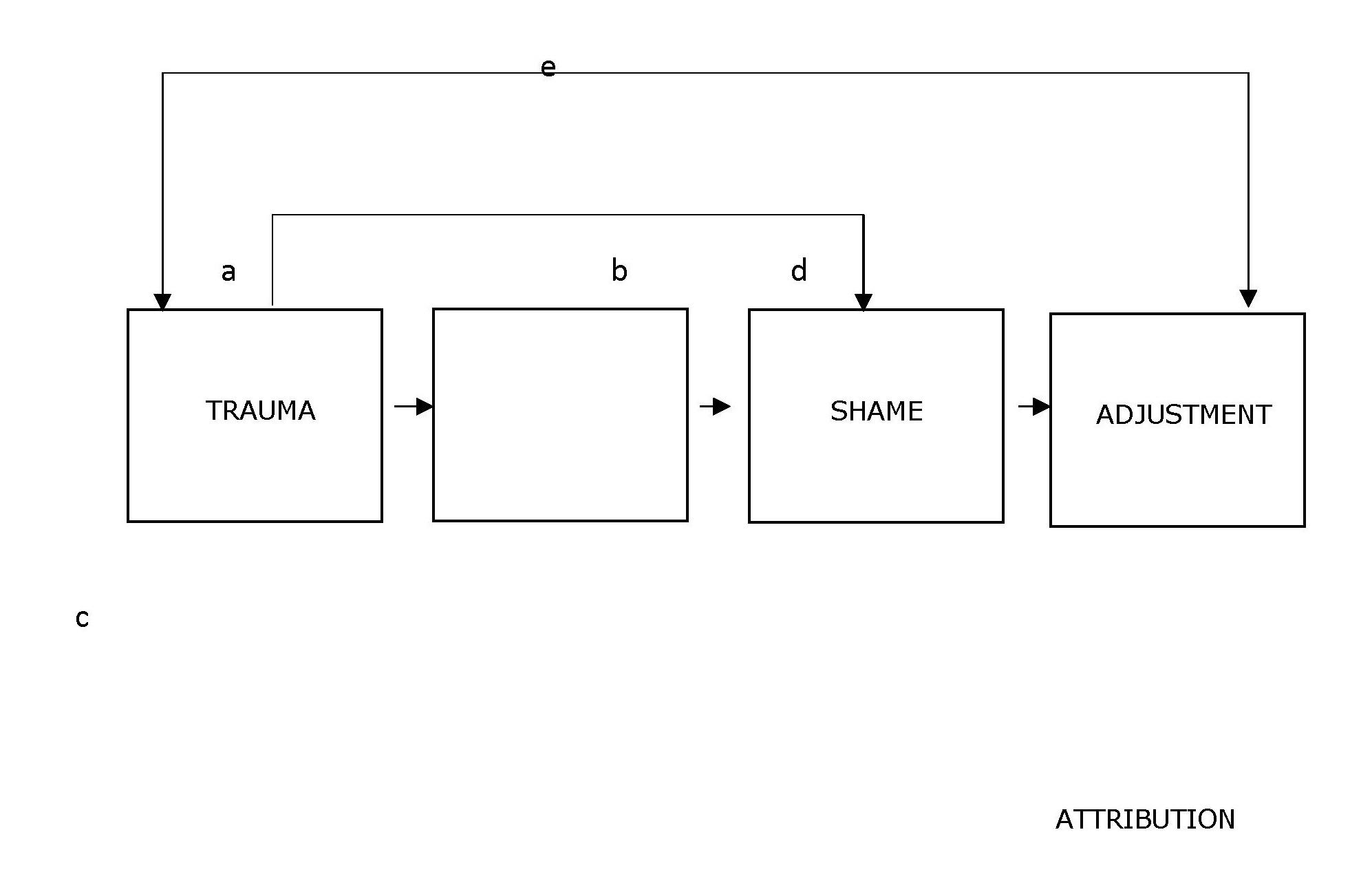

The OAS and FSCSR were found to be both reliable and valid measures when administered to this cohort. The descriptive goodness of fit indices and CFA supported the three-factor model (inferior, emptiness, mistakes) of external shame in the OAS and the three-factor (inadequate self, hated self, reassured self) model of internal shame in the FSCSR. The qualitative data provided evidence to support this conclusion. However, in the OAS the sub-scale emptiness did not perform as well as the inferior and mistakes sub-scales. This was also reflected in the qualitative data with no respondent speaking about emptiness as formulated within the OAS, but rather speaking about worthlessness as an aspect of external shame. Meanwhile, whilst the SCS demonstrated reliability it did not prove to be a valid measure in the cohort under study. The descriptive goodness of fit indices supported the six-factor model proposed by the SCS but the measure showed poor discriminant validity, due to issues of multicollinearity. In addition, the qualitative data analysis suggested the negative sub-scales of the SCS (selfjudgement, isolation and overidentification) appeared to tap directly into the psychopathology of depression. An unexpected finding in the quantitative data analysis was that levels of shame and self-criticism did not appear to be a function of severity of depression but appear to be more stable psychological constructs. However, the qualitative data contradicted this. Both forms of data collected in this thesis highlight the importance of attribution in depression and shame. The qualitative analysis yielded interesting data regarding the relationship between different childhood environments and the different forms of external and internal shame.

Conclusion

The OAS (a measure of external shame) and the FSCSR (a measure of internal shame) are reliable and valid measures when tested on a cohort with persistent, treatment resistant depression. Further, both the quantitative and qualitative results provided evidence to support the formulation of shame tested in this thesis, and the presence of an interrelated, but differentiated relationship between external and internal shame in this population. A model is proposed which integrates attributional theories of depression and shame, and an evolutionary psychobiosocial perspective, which takes into consideration the cognitive science of depression, specifically, the presence of intrusive, autobiographical, shame based emotional memories in depression and the role of rumination, thought suppression and dissociation, as affect regulation strategies. These memories, linked to childhood trauma, are important in the maintenance of persistent, treatment resistant depression. This study extends clinical knowledge of the phenomenology of shame, self-criticism and selfcompassion in the population studied.

Associated outputs

Publications

Guo, B., Kaylor-Hughes, C., Garland, A., Nixon, N., Sweeney, T., Simpson, S., Dalgleish, T., Ramana, R., Yang, M. and Morriss, R. (2017) Factor structure and longitudinal measurement invariance of PHQ-9 for specialist mental health care patients with persistent, major depressive disorder: Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling. Journal of Affective Disorders 219: pp. 1–8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.020 (Accessed 23rd July 2020).

Morriss, R., Garland, A., Nixon, N., Boliang Guo., James, M., Kaylor-Hughes., C., Moore, R., Ramana, A., Sampson, C., Sweeney, T. and Dalgleish, T. (2016) Efficacy and cost effectiveness of a specialist depression service versus specialist mental healthcare to manage persistent depression: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry 3 (9): pp. 821–831.

Morriss, R., Martunnen, S., Garland, A., Nixon, N., McDonald, R., Sweeney, T., Flambert, H., Fox, R., Kaylor-Hughes, C., James, M. and Yang, M., (2010) Randomised controlled trial of the clinical and cost effectiveness of a specialist team for managing refractory unipolar depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 10:100. Available at: doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-100 (Accessed 16th June 2012).

Thomson, L., Barker, M., Kaylor-Hughes, C., Garland, A., Ramana, R., Morriss, R., Hammond, E., Hopkins, G. and Simpson, S. (2018) How is a specialist depression service effective for persistent moderate to severe depressive disorder?: a qualitative study of service user experience. BMC Psychiatry 18 (194): pp. 1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1708-9 (Accessed 23rd July 2020).

Presentations

A defence of pragmatism as an epistemological position in healthcare research 20th April 2013. 1-hour presentation at: Research Saturday Seminars part of School of Health Sciences PhD study programme.

Symposium conveener and speaker: British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) 43rd Annual Conference, Warwick, 2015: ‘It’s Not Just What We Do It’s the Way That We Do It’: Improving clinical outcomes in CBT for complex chronic and recurrent depression through innovation in therapy and service delivery model.

Organiser and speaker at: CLAHRC NDL Mood Disorder Conference 2012/2013/2014. University of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust.

Associated training

Completed Modules (Masters level) University of Nottingham SOCI4074: Philosophy of Research (10 credits level 4).

M14152: Foundations in Qualitative Methods 2011/12 (10 credits level 4).

EPID4022: Data organisation and management in epidemiology (DOME): A practical course in Stata. (10 credits level 4).

SOCI208: Research Design and Practice (10 credits level 4).

B74MMR: Mixed methods in Health Research 2012 (10 credits level 4).

Short Courses

Searching Healthcare Databases 16th November 2011.

Introduction to Good Clinical Practice -National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network 14th December 2011.

Introduction to Multilevel Statistical Modelling- Dr. Boliang Guo, Institute of Mental Health, June 2015.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank the participants in the RCT in which this PhD study was based, alongside the patients diagnosed with persistent, treatment resistant depression, with whom I have had the privilege to share the psychotherapy endeavour over the last three decades. You have shown immense fortitude on this journey and through your determination to persevere have demonstrated that as humans we are wired to survive and thrive, sometimes against the odds. I am honoured to have learned all that I have from you-in no small way you have helped make me the clinician, researcher and educator I am today and to quote Joni Mitchell: ‘Part of you falls out of me in these words from time to time’.

This PhD has been a long time in the making. As with most journeys in my life I have walked the country mile. I have had many educational and professional experiences, that by dint of the place where and the generation into which I was born, I was never destined to have. I am especially grateful to those who have, on this journey, judged me by my merit and not by my gender, my accent, my class or my profession. I am where I am in part, because of you and I hold each of you in my heart always.

Thank you, Chris, my devoted and ever patient husband of thirty years. You have looked after me throughout this journey as you always do and as I always need to be-by watching over me and deploying wit and wisdom in equal measure, PRN. Thank you for the endless cups of tea and coffee and for your patience, generosity and sacrifice, which has, throughout, been immense. I could not have done this without you and I love you with all my heart and soul now and always.

Thank you to my friends and colleagues who have chivvied me along through this PhD and for believing in me, I treasure you all. Marie Armstrong for your constancy in encouraging me and your wise counsel and sound and practical problem solving when needed. Richard Fox, my friend, colleague and CBT clinical supervisor, you are the third eye in this thesis. Jane Lowey our clinical team secretary- you make a difference to all the lives you touch. Tim Carter and Tim Sweeney your empathy and help at key moments has been received with heartfelt gratitude. The managers and clinical leaders in Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust who supported the RCT and subsequently the establishment of the permanent SDS. My good friend Charles, your daily WhatsApp messages of encouragement have helped keep me going over the last 12 months. My friends at book club (in alphabetical order -Catherine, Chris, Lynne, Marie and Mel) our choice of literature, whether bringing edification or ennui (in the case of most of my choices), has been outshone only by our joyous and stalwart companionship. Our literary reveries have brought welcome respite from statistical equation modelling. The grandchildren, Grace, George, Elsie and Emme you have taught me so many things that a PhD never could -shame totems (Grace), Minecraft (George), Shimmer and Shine (Elsie and Emme) -my life is richer for your presence in it -thank you to you and your parents, Sara and Phil-know that you are loved and cherished.

I would like to thank all the members of the CLAHRC-NDL research team who have supported me throughout this PhD study, with special thanks to Boliang Guo and Cath Kaylor -Hughes, you made a big difference when I needed it. Gratitude also to Professor Paul Gilbert for sharing your time and intellect and good humour and for teaching me first-hand the theory and practice of CFT. A special thanks also goes to the staff at Duncan McMillan Library at the Trust who have been unstinting in their assistance in helping me find obscure publications. Your cheerful and willing disposition and tenacity in searching has helped enormously throughout this process.

Finally, with all my heart I wish to thank, in equal measure, my two PhD supervisors (in alphabetical order) Professor Patrick Callaghan and Professor Richard Morriss, who at different times held the role as my primary supervisor. You have both, with immense good grace, constancy and kindness walked these PhD country miles with me, which has been both a privilege and an honour. You have shown generosity in sharing your time, of which, I know, there is never enough. Your intellects are a privilege to behold and your clinical and academic acumen throughout this period of study has at different times, in equal measure, offered both inspiration and solace. We share a common bond in placing patients at the heart of our work, with the determination as clinicians, academics and educators, to advance knowledge and develop clinical interventions for complex mental health problems. With great affection and deep respect, thank you.

Preface

This study was part of a larger National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) funded randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating the clinical and cost effectiveness of a Specialist Depression Service (SDS) offering NICE recommended pharmacological and psychological (CBT and MBCT) treatments, to patients diagnosed with persistent, treatment resistant depression. The RCT was part of a CLAHRC-NDL programme grant which ran between 2008–2013. I was a grant holder on the project alongside Professor Richard Morriss the lead for CLAHRC-NDL and one of my PhD supervisors. At the time of commencing this PhD I was employed as Consultant Nurse in Psychological Therapies in Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, where the study was based. I was clinical lead for the SDS and for the RCT in service.

Regarding the PhD study I designed the research questions, chose the measures to be tested and the qualitative data collection and analysis process. The quantitative data was collected by the trial research associates. However, I completed my own data entry for the three psychometric measures tested in this thesis and under supervision of the team statistician Dr. Boliang Guo and Professor Morriss conducted the statistical analysis for these measures. I collected and analysed the qualitative data under the supervision of Professor Patrick Callaghan.

The ideas tested in this thesis emerge directly from my clinical work and the proposed model presented in the final chapter of this thesis is my own original work building, on the existing evidence base in the field of depression and founded in thirty years of my career working clinically and academically with people diagnosed with depression.

Contents

Abstract

Associated outputs

Associated training

Acknowledgements

Preface

List of Figures

List of Tables

List of Abbreviations

Chapter one

Introduction and overview

The significance of the study

Depression and co-morbid disorders

Motivation for conducting this study

The cognitive science of depression

The evidence base for Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

Defining depression

Defining and treating persistent, treatment resistant depression

CBT Treatments for Depression

The way forward in persistent, treatment resistant depression

Chapter 2

Literature Review

Introduction

ThePracticality of theories: Defining a decision-making process

The conundrum of defining Shame as an affect

Cognitive-affective models of shame

Cognitive-Attributional theories of shame

Lewis’ attributional theory of self-conscious emotions

Standards, Rules and Goals (SRG’s)

Internal versus external evaluations

Attributions about self: Global versus Specific

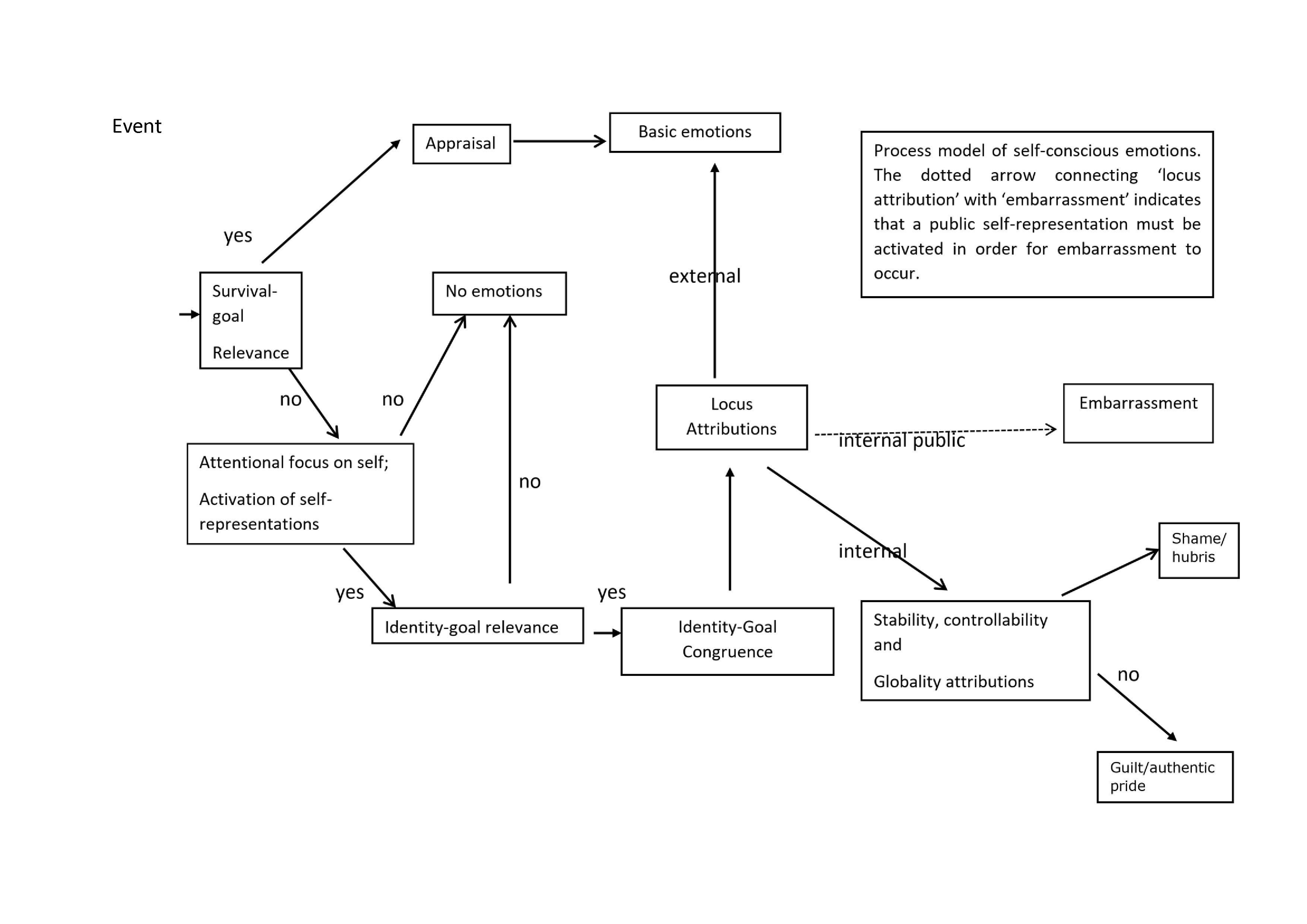

Tracy and Robin’s appraisal-based process model of self-conscious emotions

Step 1: Survival-Goal Relevance

Step 2: Attentional Focus on Self and Activation of Self-Representations

Step 3: Identity-Goal Relevance

Step 4: Identity-goal congruence

Step 5: Internality attributions

Step 6: Stability, Globality, controllability attributions

Applying appraisal-based process models of self-conscious emotions in research

The evolutionary and biopsychosoical psychology model of shame

The definition of self-criticism

The psychoanalytic Formulation of Self-criticism

The Behavioural Formulation of Self-criticism

The cognitive formulation of self-criticism

76 The Attributional Theory formulation of self-blame

The evolutionary formulation of self-criticism

Theories of the nature and origins of self-criticism and self-blame

Defining compassion and self-compassion

An evolutionary formulation of compassion

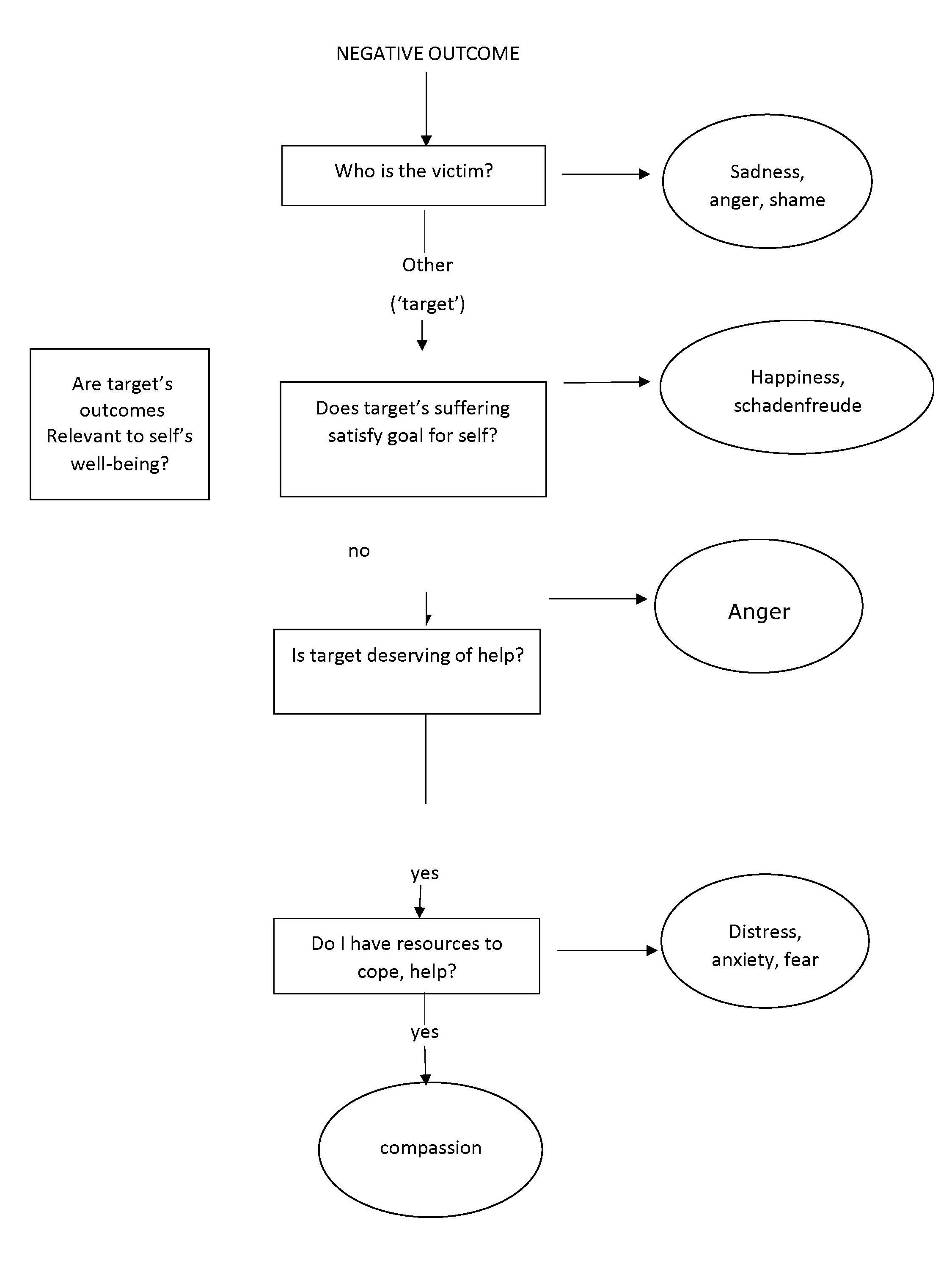

87 Compassion as an appraisal elicited emotion

Compassion as a motivational system

Definition of self-compassion

Self-kindness versus self-judgment

Common humanity versus isolation

Mindfulness versus over identification or avoidance

Examining the Practicality of these theories of shame using Brawley’s criteria

A critique of Gilbert’s theory of shame

Why is the proposed study needed?

Chapter 3

Methods

Introduction

Research aims and objectives

Study Design

Philosophical Pragmatism as an epistemological foundation

Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods

PhD Study Context

The Study Sample

Sampling

The power calculation in this PhD study

Sample size

Recruitment Process

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the RCT

Data Collection Methods

Detailed Description of Quantitative Data Collection Method

Step 1: Testing the psychometric status of OAS; FSCR and SCS

129 Rationale for chosen measures of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion

An overview of each measure

Other as Shamer Scale (OAS)

The forms of self-criticising/attacking and self-reassuring scale (FSCRS)

Self Compassion Scale (SCS)

Step 2: Modelling variance in depressive symptoms against shame, self-criticism and self- compassion

Rationale for chosen measures of depression

An overview of each depression measure

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HDRS-17)

Beck Depression Inventory-I (BDI-I)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Step 3: Exploring patients lived experience of shame, Self-criticism and self-compassion

Procedure for quantitative data collection

Description of Qualitative Data Collection Method

Quantitative data analysis

Establishing reliability and validity of the OAS, FSCR and SCS

144 Defining reliability

Defining validity

Testing reliability

Internal consistency

Modelling variance of depression in relation to shame, self-criticism and self-compassion

The argument for epistemological coherence: The Primacy of Praxis revisited

Ethical considerations

Data Management

Confidentiality

Process for obtaining informed consent

Fieldwork and safety guidelines

Ethics Approval to conduct this research

Chapter 4

Quantitative Results

Introduction

Question 1: To test the psychometric properties of the OAS, FSCSR and SCS in a cohort of patients

diagnosed with persistent, treatment resistant depression:

1. Descriptive statistics

2. Inferential statistics

I. Reliability

155 ii. Validity:

Question 2: To examine the degree to which variance in scores on depression measures taken at baseline can be accounted for by variance in levels of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion157

I. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis

The demographic profile of the study cohort

Healthy

Controls

Descriptive Statistics for Other as Shamer Scale (OAS) baseline

Reliability for Other as Shamer Scale (OAS) baseline

Split-Half Reliability for OAS at baseline

Test-retest reliability for OAS at baseline and 6 months

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Other as Shamer Scale

Descriptive Statistics for Forms of Self-Criticising Self -Reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

Reliability of the FSCSR at baseline

177 Split half reliability for the FSCSR at baseline

Test-retest reliability for FSCSR at baseline and 6 months

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Forms of Self-Criticism and self-Reassurance Scale (FSCSR) 186

Descriptive Statistics for Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) baseline

Reliability of SCS at baseline

Split half reliability for SCS at baseline

Test-retest reliability for SCS at baseline

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for SCS

Objective 2: To determine how levels of shame, self-criticism and self-compassion correlate with

level of depression

Chapter 5

Qualitative results

Reflexivity

215 Emergent themes and sub-themes in the qualitative data

1. Childhood adversity and the social milieu

(i) No expectation

(ii) Every expectation

(iii) Behind closed doors

Reluctance to speak about childhood

3. Sense of self

224 I. Not good enough/inferior/failure-self-criticism

224 ii. unimportant/not counting/not worthy-self-blame

227 iii. Bad/inadequate/insignificant/worthless: self-hate/loathing

3. The function of self-criticism/self-hating

4. Absence of self-compassion

240 i. Intellectual appreciation with good intentions

240 ii. Not understood/incomprehension

Risky

iv. Not deserved

5. Avoidant coping

7. Memory and information processing biases in depression

Summary

[[#_Toc526213][Chapter

[[#_Toc526214][Discussion

[[#_Toc526215][Introduction

Summary of

Findings

Examination of the psychometric properties of the OAS, FSCSR and SCS in the study cohort

Examination OAS by sub-scale

Sub-scale inferior

Sub-scale emptiness

Sub-scale mistakes

Suggested revisions to the OAS

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the OAS

Examination of the FSCSR and its sub-scales in relation to persistent treatment resistant depression

Subscale Inadequate self

Subscale Hated self

262 Subscale Reassured self

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the FSCSR

Examination of the SCS by sub-scale in relation to persistent treatment resistant depression .267

Previous studies of the psychometric properties of the SCS

Summary of quantitative and qualitative data in this PhD thesis in the context of Gilbert’s

evolutionary biopsychosocial model

A continuum of shame and self-criticism and absence of self-compassion in persistent, treatment resistant depression

Defining the parameters of approval and subjugation

Shame of not meeting expectation: Every expectation

Shame, ridicule and humiliation: No expectation

Riven with shame: trapped and defeated

Clinical implications of these findings and avenues for future research

Strengths of this study

Limitations of this study

Conclusion

References

Appendices

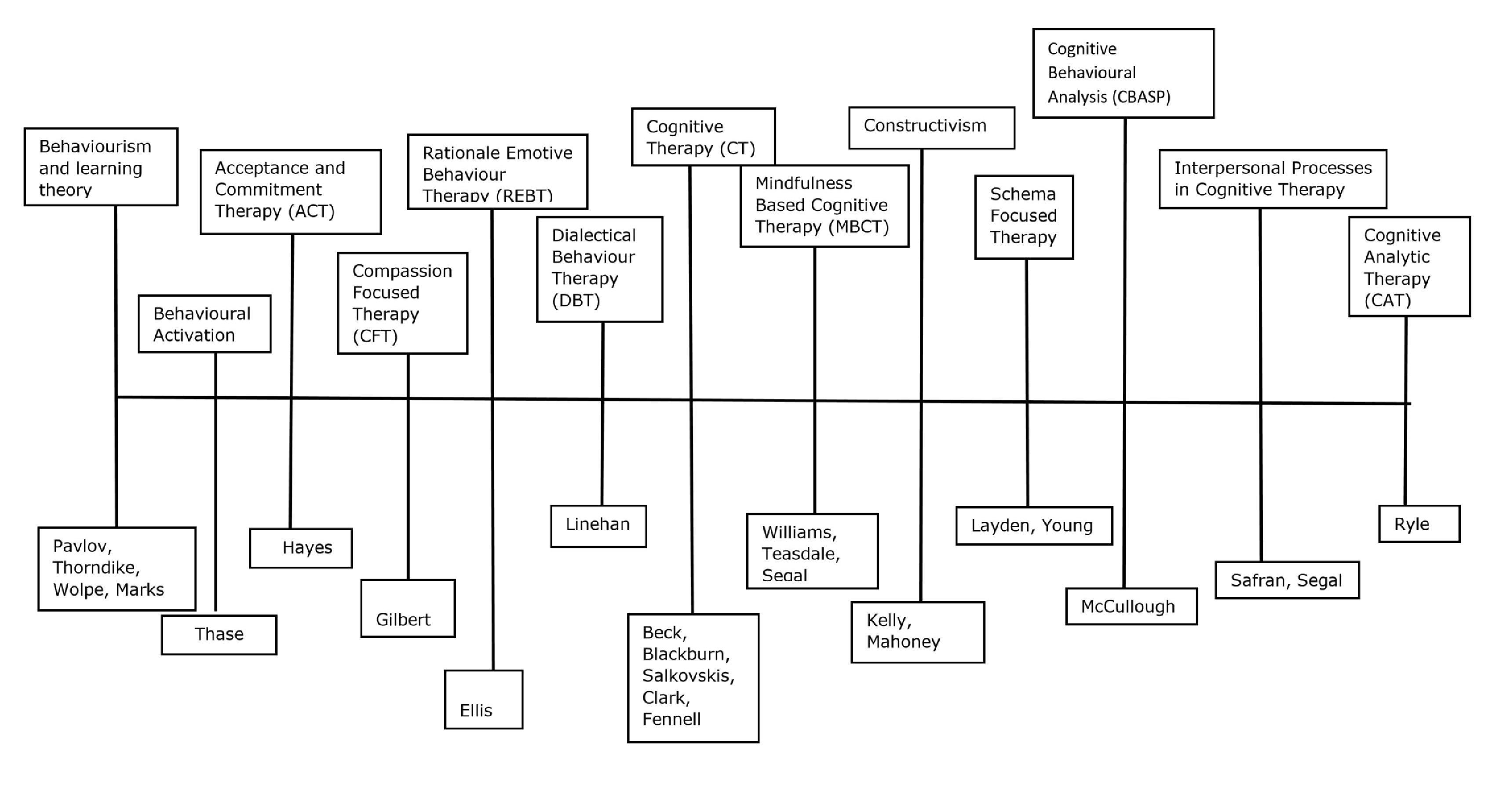

Appendix I: Continuum of Schools of Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapies (adapted from Gilbert 2007b)

Appendix II: Table of summary of the biological, psychological, genetic and clinical correlates of

Treatment Resistant Depression

(from Murphy, Saris and Byrne 2017 p. 4)

Appendix III: Proposed criteria for Multiple-Therapy-Resistant (MTR) Major Depressive Disorder

Appendix IV: A theoretical process model of self-conscious emotions (Tracy and Robins 2007a p10)

Appendix V: Appraisal model of compassion illustrating how witnessing negative outcomes

leads to felt compassion with moderation of relevance to self

(from Goetz, Keltner and Simon-Thomas 2010 p 356)

Appendix VI: Theories of shame measured against Brawley’s (1993) Practicality of a theory criteria

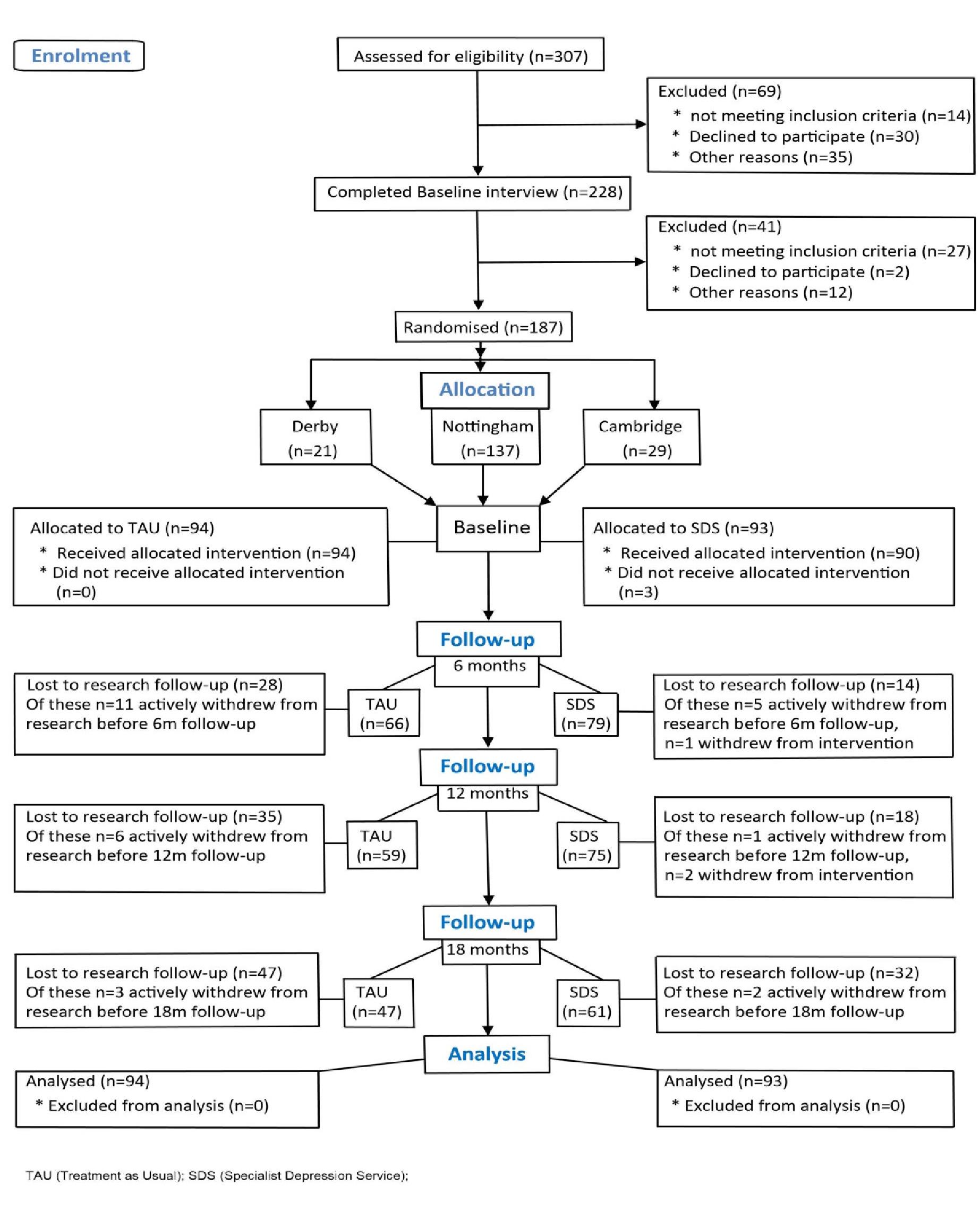

Appendix VII: Consort diagram of participant flow through RCT (from Morriss, Garland, Nixon, Boliang, et al, 2016)

Appendix VIII: Email invitation to participate as a healthy control in the study

Appendix IX: Healthy Controls: Screening Questionnaire

Appendix X: Participant Information Sheet

Appendix XI: Healthy Controls Participant Consent Form

Appendix XII: Other as Shamer Scale

Appendix: XIII: The Forms of Self-Criticising and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

Appendix XIV: Self Compassion Scale (SCS)

How I Typically Act Towards Myself in Difficult Times

Appendix XV: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (Hamilton, 1960)

Appendix XVI: Beck Depression Inventory-I (BDI-I)

Appendix XVII: The Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Appendix XVIII: Qualitative Interview Topic Guide

Appendix XIX: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub-scale inferior at baseline

Appendix XX: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub-scale emptiness at baseline

Appendix XXI: Histogram and box plot for the OAS sub-scale mistakes at baseline

Appendix XXII: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub-scale inadequate self at baseline ....371 Appendix XXIII: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub-scale hated self at baseline

Appendix XXIV: Histogram and box plot for the FSCSR sub-scalereassured self at baseline

Appendix XXV: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale self-kindness at baseline

Appendix XXVI: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale self-judgement at baseline

Appendix XXVII: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale common humanity at baseline 376

Appendix XXVIII: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale isolation at baseline

Appendix XXIX: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale mindfulness at baseline

Appendix XXX: Histogram and box plot for the SCS sub-scale overidentification at baseline ....379

Appendix XXXI: Example of steps of qualitative data analysis (participant 12)

Appendix XXXII: Photographs of an example of a mind map (participant 12)

Appendix XXXIII: Biographies of participants in qualitative arm of this PhD study

Appendix XXXIV: The subscales and items of the OAS

Appendix XXXV: The sub-scales and items of the FSCSR

Appendix XXXVI: The items and sub-scales of the SCS

List of Figures

Figure 1: Empirically Grounded Clinical Interventions (Salkovskis 2002)

Figure 2: Lewis’s cognitive- attributional theory of self-conscious emotions (Lewis 2000 p

Figure 3: Lewis’ proposed relationship between shame and psychopathology (Lewis, 2000, p

Figure 4: An evolutionary and biopsychosocial model of shame (Gilbert 2007a p.301)

Figure 5: Convergent parallel mixed methods design (Creswell and Plano-Clark (2011, p 69)

Figure 6: Confirmatory Factor Analysis path diagram for the Other as Shamer Scale (OAS)

Figure 7: Confirmatory Factor Analysis path diagram for the Forms of Self-Criticising and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCSR)

Figure 8: Confirmatory Factor Analysis path diagram for the Self Compassion Scale (SCS) . 202 Figure

9: Formulation of a continuum of shame, self-criticism and absence of self- compassion in persistent treatment resistant depression

List of Tables

Table 1: DSM-5 Diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (APA 2013 p 160–161)

Table 2: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Persistent Depressive Disorder (APA 2013 p 168–169)

Table 3: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Bi-polar II Disorder (APA 2013 p 132–139)

Table 4: Summary of data collection and analysis methods

Table 5: Types of questions for in-depth interviews

Table 6: Demographic characteristics of the study cohort at baseline

Table 7: Participants clinical characteristics of depression at baseline

Table 8: Secondary clinical characteristics of the study cohort at baseline

Table 9: Mean scores (SD) on HDRS-17 and BDI-I for healthy control group versus study cohort

Table 10: Summary statistics for OAS at baseline

Table 11: Distribution for each sub-scale of OAS at baseline

Table 12: Cronbach’s Alpha scores at baseline for OAS scale

Table 13: Item statistics for sub-scale inferior at baseline

Table 14: Item statistics for sub-scale inferior at baseline

Table 15: Item statistics for sub-scale emptiness at baseline

Table 16: Item to item correlation for sub-scale emptiness at baseline

Table 17: Item statistics for sub-scale mistakes at baseline

Table 18: Item to item correlation for sub-scale mistakes at baseline

Table 19: Summary item means statistics for OAS at baseline

Table 20: Split Half Reliability scale statistics for OAS at baseline

Table 21: Test-retest reliability for OAS at baseline and 6 months

Table 22: The continuous latent variables and indicators tested for OAS, FSCSR and SCS ... 173

Table 23: Model Fit indices for OAS

Table 24: Summary statistics for FSCSR at baseline

Table 25: Distribution for each sub-scale of FSCSR at baseline

Table 26: Cronbach’s Alpha for FSCSR at baseline

Table 27: Item statistics for sub-scale inadequate self at baseline

Table 28: Item to item correlation for sub-scale inadequate self at baseline

Table 29: Item statistics for sub-scale hated self at baseline

Table 30: Item to item correlation for sub-scale hated self at baseline

Table 31: Item statistics for sub-scale reassured self at baseline

Table 32: Item to item correlations for sub-scale reassured self at baseline

Table 33: Summary item means statistics for FSCSR at baseline

Table 34: Split half reliability scale statistics for FSCSR at baseline

Table 35: Test -retest reliability for FSCSR between baseline and 6 months

184 Table 36: Model Fit indices for FSCSR

Table 37: Summary statistics for Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) at baseline

Table 38: Distribution for each sub-scale of SCS at baseline

Table 39: Cronbach’s Alpha for SCS at baseline

Table 40: Item statistics for sub-scale self-kindness at baseline

Table 41: Item to item correlation for sub-scale self-kindness at baseline

Table 42: Item statistics for sub-scale self-judgment at baseline

Table 43: Item to item correlations for sub-scale self-judgement at baseline

Table 44: Item statistics for sub-scale common humanity at baseline

Table 45: Item to item correlations for sub-scale common humanity at baseline

Table 46: Item statistics for sub-scale isolation at baseline

Table 47: Item to item correlations for sub-scale isolation at baseline

Table 48: Item statistics for sub-scale mindfulness at baseline

Table 49: Item to item correlations for sub-scale mindfulness at baseline

Table 50: Item statistics for sub-scale overidentification at baseline

Table 51: Item to item correlations for sub-scale overidentification at baseline

Table 52: Summary item means for SCS at baseline

Table 53: Split Half Reliability scale statistics for SCS at baseline

Table 54: Test retest for SCS at baseline and 6 months (**. CORRELATION is significant at 0.01 level (2 tailed)

Table 55: Model Fit indices for SCS

Table 56: Influence of OAS, FSCSR and SCS on HRSD-17 by univariate and multivariate regression modelling

Table 57: Influence of OAS, FSCSR and SCS on BDI-I univariate and multivariate regression modelling

Table 58: Influence of OAS, FSCSR and SCS on PHQ-9 univariate and multivariate regression modelling

207 Table 59: Definition of ‘cognition’ within IPA

List of Abbreviations

ACT: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

APA: American Psychiatric Association

ATTS: Attitudes Towards Self Scale

ASQ: Attributional Style Questionnaire

BA: Behavioural Activation

BABCP: British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies

BAP: British Association of Pharmacology

BDI-I: Beck Depression Inventory-I

BMI: Body Mass Index

CAT: Cognitive Analytic Therapy

CBASP: Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System

CBT: Cognitive behaviour Therapy

CFA: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

CFI: Comparative Fit Index

CFT: Compassion Focused Therapy

CLAHRC-NDL: Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

CT: Cognitive Therapy

CVD: Cardiovascular Disease

DALY’s: Disability Adjusted Life Years

DoH: Department of Health

DEQ: Depressive Experiences Questionnaire

DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

DD: Double Depression

EFA: Exploratory Factor Analysis

FSCSR: Forms of Self-Criticism/Self-Reassurance Scale

GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning

GBD: Global Burden of Disease

HDRS-17: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17

ICD: International Classification of Diseases

IPA: Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

IPT: Interpersonal Therapy

MBCT: Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy

MDD: Major Depressive Disorder

MSC: Mindful Self Compassion

NEMESIS: Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study

NHS: National Health Service

NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

NIHR: National Institute for Health Research

NIMH: National Institute of Mental Health

NMC: Nursing and Midwifery Council

OAS: Others As Shamer Scale

PFQ-2: Personal Feelings Questionniare-2

PDD: Persistent Depressive Disorder

PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial

RSMEA: Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

SCS: Self Compassion Scale

SDS: Specialist Depression Service

SEM: Standard Error of Measurement

STAR*D: Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relive Depression

SCL-90: Symptom Checklist-90

SPSS: Statistical Package of the Social Sciences

TAU: Treatment as Usual

TOSCA: Test of Self-Conscious Affect

TLI: Tucker Lewis Index

WHO: World Health Organisation

WMA: World Medical Association

WLSMV: Weighted Least Square Mean Variance adjusted

YLD’s: Years Lived with Disability

Chapter one: Introduction and overview

The significance of the study

In 1973 Martin Seligman, in reference to the rate of diagnosis, described depression as ‘the common cold of psychiatry’. Over the proceeding four decades it has been suggested depression is reaching near pandemic levels in terms of both incidence and disease burden (Kramer, 1983). More recent and statistically rigorous epidemiological studies have challenged the idea that depression has reached epidemic proportions. Whilst Baxter, Scott, Ferrari, Norman, Vos and Whiteford (2014) found a 37% increase in prevalence of depression between 1990–2010, this can be predominately accounted for by population growth and ageing (cf: Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos 2013). Following the publication of the findings of the first World Health organisation (WHO) Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2000 depression was declared ‘a major public health problem that affects patients and society’ (Ustun, Ayuso-Mateos, Chatterji, Mathers and Murray 2004). It is estimated depression affects over 120 million people worldwide with a lifetime prevalence ranging from 10% — 15% (Lepine and Briley 2011).

It is well established in the research literature that depression is a relapsing illness. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) conducted a 10-year prospective observational study examining the recovery from and recurrence of major depressive disorder (Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller, Lavori, Shea, Coryell, Warshaw, Turvey, Maser and Endicott 2000). Recovery was defined as experiencing no symptoms of major depression or one or two symptoms at a mild level severity for a period of eight weeks. Meanwhile, recurrence was defined as meeting the diagnostic criteria for full Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) for at least two consecutive weeks. Recovery was only deemed to have occurred after an individual had first recovered from the preceding episode. Episodes of minor depressive disorder and chronic depression were excluded from statistical analysis. The study cohort consisted of 318 participants diagnosed with unipolar major depression who recovered from their intake episode and of these, 202 went on to experience a recurrence. The cumulative risk of recurrence at 1 year was 25%, at 2 years 42% and at 5 years 60%. Of these 202 who suffered a recurrence 172 recovered and were at risk of recurrence. Of these 172, 115 went on to experience a second recurrence and for this sub-group the cumulative probability of recurrence at 1 year was 41%, at 2 years 59% and at 5 years 74% (Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller et al 2000).

Overall, at each time point the cumulative probability of recurrence increased and the time to recurrence between each episode decreased, with the number of lifetime episodes of major depressive disorder being significantly associated with recurrence over the study period. Conversely, as the duration of recovery persisted the risk of recurrence reduced. The authors conclude that the probability a relapse of major depressive disorder is significantly influenced by the number of lifetime episodes experienced before any period of recovery or wellness. Further, with each successive episode the probability of recurrence increases, with the risk of recurrence increasing by 16% with each successive episode (Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller et al 2000). This study built on previous research by the authors (Keller, Lavori, Lewis and Klerman (1983) who examined predictors of relapse in depression and concluded that individuals diagnosed with unipolar depression are, most at risk of relapse following their first depressive episode. Further, if relapse does occur, they have a 20% chance of their illness taking a chronic course and with each subsequent relapse the chance of further relapses also increases. This in turn built on a body of research examining depressive recurrence and relapse across five decades (Murphy, Saaris and Byrne 2017; Fava 2003; Kupfer, Frank, Perel, Cornes, Mallinger, Thase, McEachran and Grochocinski 1992; Belsher and Costello 1988; Lee and Murray, 1988; Nystrom 1979).

Taking this lifetime risk of relapse and recurrence into consideration the human and economic cost of depression is immense. The second WHO GBD study published in 2010 cites that within the mental and substance use disorders group, at 40.5%, depressive disorders account for the highest proportion of burden across all mental disorders both in terms of the most

Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years (DALY’s) and, at 42.5%, the most Years-Lived with Disability (YLD’s). Further, in terms of the ten leading causes of total burden in 2010, mental disorders and substance use disorders accounted for 7.4% DALY’s and 22.9% YLD’s (Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, et al, 2013). A more recent WHO Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (GBD, 2017), identified depression as possessing the greatest global burden of disease and declared it to be the leading cause of DALY’s (DALY’S) lost due to ill-health.

When considering persistent, treatment resistant depression, the focus of this PhD study, then those experiencing this form of depressive disorder are less productive, experience greater medical co-morbidity (see below for a more detailed discussion) and make more suicide attempts (Amital, Fostick, Silberman, Beckman and Spivak (2008). Rhebergen, Beekman, Graaf, Nolen, Spijker, Hoogendijk and Penninx (2010) using data from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS), conducted a study with a cohort of 7076 participants aged between 18–64 years. Data gathered over a three year period between 1996–1999, examined the recovery trajectories for social and physical functioning for participants diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and/or dysthymia and what is termed ‘Double Depression’ (DD), dysthymia superimposed over MDD. The study found that compared to participants with no diagnosed depressive disorder all depressed groups showed significant impairment in terms of social and physical functioning. Dysthymia and DD had lower post-morbid physical functioning compared to MDD, after one year and three years. In addition, the study found that impaired social functioning was determined by neuroticism and impaired physical functioning by age, a co-occurring somatic complaint and neuroticism.

Depression and co-morbid disorders

Depression often exists co-morbidly with other mental health problems, notably, anxiety disorders, and with chronic physical health conditions. A study published in 2007 found that depressive and anxiety disorders were independently related to a range of chronic physical health conditions, with heart disease and chronic pain showing the strongest association with depressive and anxiety disorders (Scott, Bruffaerts, Tsang, Ormel, Alonos, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bromet, Giroamo, Graaf, Gasquet, Gureje, Haro, He, Kesselr, Levinson, Mneimneh,

Okaley-Browne, Posada-Villa, Stein, Takeshmia and Von Korff, 2007). Results from the World Health Survey (Moussav, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun, 2007) compared depression with four other chronic physical health conditions: angina, arthritis, asthma and diabetes and examined how the decline in health status associated with depression (Chapman, Perry and Strine 2005) compared with the decline in health status in these four chronic physical health conditions, alongside, what is the added effect of suffering with depression plus one or more of these chronic physical health conditions. This study showed that comorbidity between depression and chronic physical health conditions is common and that individuals suffering with a chronic physical health condition are more likely to suffer with depression than those with no such conditions. Also, depression is associated with a greater decline in overall health status than any of the four chronic physical health conditions studied. Further, depression co-occurring with any of these chronic physical health conditions results in a significantly greater decline in health status than from suffering from one or more of the physical health conditions alone. This decline in health status is accentuated further where depression and diabetes occur co-morbidly (Moussav, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, et al, 2007).

Chapman, Perry and Strine (2005) conducted a review of the research literature looking at the relationship between depression and asthma, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and obesity. This comprehensive review yields sobering data. Briefly these can be summarised as follows from Chapman, Perry and Strine (2005). Almost 50% of people diagnosed with asthma report significant symptoms of depression, particularly where symptoms are disruptive to day to day functioning or are difficult to control. Similarly, for people with arthritis symptom severity and recurrence and restriction in mobility were correlated with greater severity of depression. The link between depression and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is well established. Depression is associated with risk factors for CVD such as smoking and reduced physical activity. In addition, those suffering with depression are more likely to suffer coronary artery disease and the risk of developing coronary heart disease is 1.6 times greater if the person also experiences depression. Depression is also predictive of a stroke and a person with significant depressive symptoms is twice as likely to have a stroke as someone with fewer symptoms. Depression is also associated with an increased risk for morbidity and mortality for a stroke and the onset of depression is common following a stroke. Equally, a person with a history of major depressive disorder is four times more likely to suffer a myocardial infarction than someone without such a history. In cancer, 21% of cancer patients are reported to be experiencing depression and increased depressive symptoms reduces survival rates. Depression is twice as common among people with diabetes as those without and its occurrence is associated with factors including coming to terms with the illness itself, diabetic complications, unemployment and the degree to which diabetes interferes with activities of daily living. Regarding obesity the authors note that most obese people do not suffer with a mood disorder, but the literature does reveal a significant positive relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and depressive symptoms. The authors conclude by highlighting the reciprocal relationship between chronic disease and depressive disorders and observe that, as discussed above, untreated depression is likely to develop into a chronic condition in its own right.

Motivation for conducting this study

The author of this thesis is a mental health nurse by profession and is trained in both behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy, with 30 years’ experience of using cognitive and behavioural interventions to treat persistent, treatment resistant depression. The author can be described as a clinical academic working in both a National Health Service (NHS) specialist depression service and academia, both as a trial therapist in two randomized controlled trials

(RCT) (Morriss, Garland, Nixon, Boliang Guo, James, Kaylor-Hughes, Moore, Ramana,

Sampson, Sweeney, and Dalgleish, 2016; Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland, Moore, Jenaway, Cornwall, Hayhurst, Abbott and Pope, 1999), a researcher and an educator.

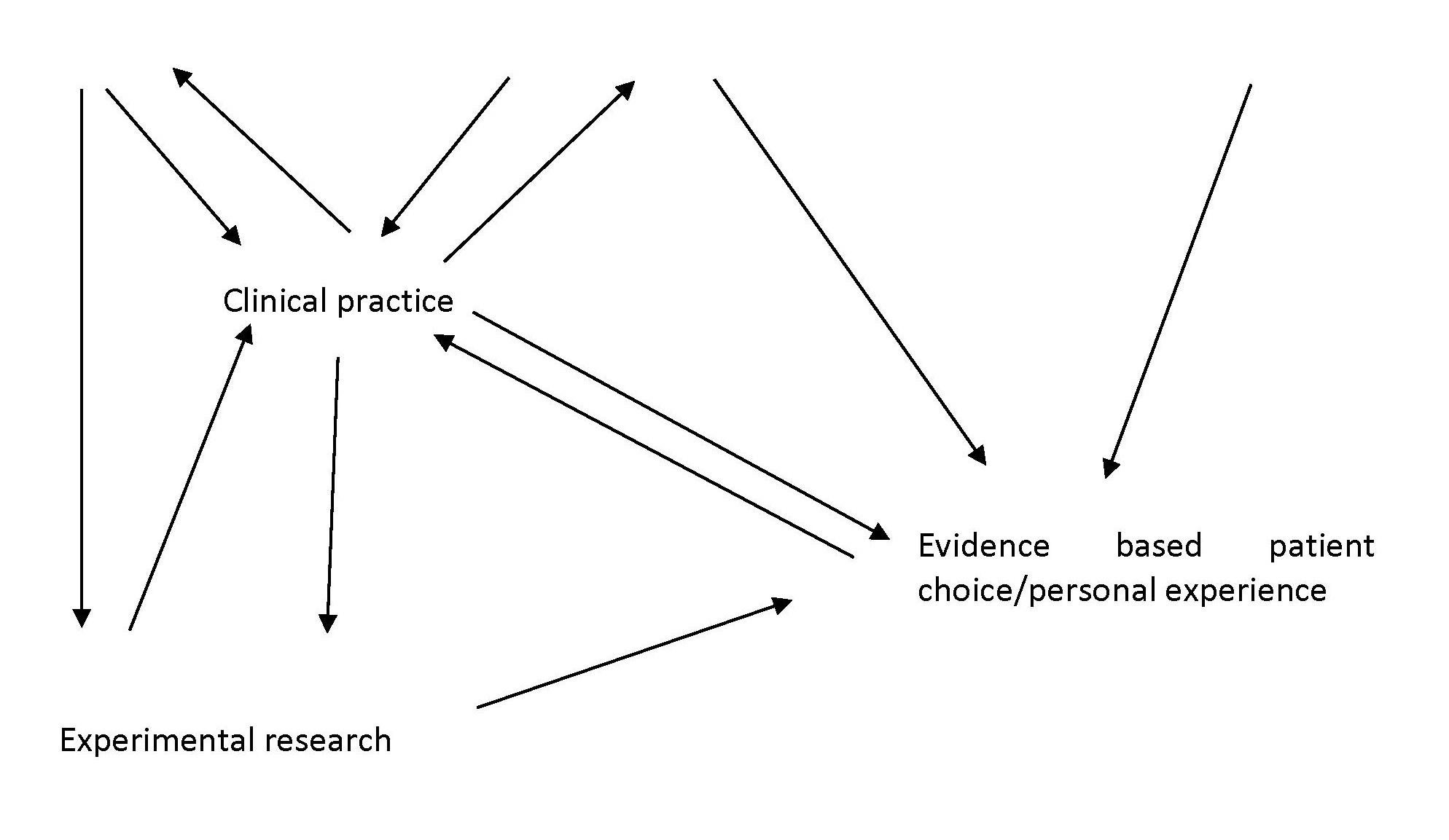

The authors approach to research is founded in the Scientist Practitioner paradigm (Salkovskis 2002) and the motivation for choosing this PhD focus is clinical curiosity regarding the limitations of both cognitive and behavioural interventions when working with persistent, treatment resistant depression. Salkovskis (2002) observes that when a patient does not respond to a specific treatment intervention then the limitation resides in the intervention (not the patient and their clinical presentation) and he advocates utilising ‘empirically grounded clinical interventions’ (Salkovskis 2002) which brings together data from a range of sources (see figure 1 below) to develop more effective cognitive and behavioural clinical interventions.

][<strong>FIGURE 1: EMPIRICALLY GROUNDED CLINICAL INTERVENTIONS (SALKOVSKIS 2002)</strong>

Theory outcome research clinical guideline i.e. NICE

As Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer and Dobson (2013) observe, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is the most researched psychotherapy modality for adult depression. In a recent meta-analysis, the authors observe a fundamental challenge that exists not just for the researcher conducting a meta-analysis but for the practitioner of CBT, namely, how CBT is defined. This debate exists in all aspects of the CBT literature and clinical practice. Gilbert (2007b) identifies at least sixteen schools of cognitive and behavioural psychotherapies (see appendix 1) and describes the acronym CBT as an umbrella term that incorporates a broad church of theoretical orientations and attendant clinical interventions. As appendix I Illustrates this broad church spans a range of orientations from the traditional behavioural theories and models (i.e. Marks 1981) through to the Beckian cognitive perspective (Moore and Garland 2003; Fennell, 1989; Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, 1979) and what are considered to be more integrative approaches such Interpersonal Processes in Cognitive Therapy (Safran and Segal 1996) and Ryle’s Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT)(Ryle and Kerr, 2002). The evidence base for these different schools housed under the CBT umbrella is variable. It can also be said that the more integrative approaches, which draw on a combination of behavioural, cognitive, psychodynamic, gestalt and interpersonal psychotherapy theory and practice such as Schema Focused Therapy (Young, 2003; 1990;

Layden, Newman, Freeman and Eyers-Mors, 1998) Cognitive Analytic Therapy (Ryle and Kerr, 2002) and Dialectic Behaviour Therapy (Linehan, 1993) have, Like Beckian cognitive therapy itself, (see Weishaar 1993 for a biographical account of the development of Beckian cognitive therapy) emerged from clinical observation. This is often in the context of a clinical need to develop interventions for working with more complex clinical presentations where standard cognitive and behavioural interventions delivered within a standard treatment rationale have limited impact in terms of ameliorating symptomatology and social functioning.

The author of this thesis would, under the CBT umbrella, primarily align herself with cognitive therapy (Kinsella and Garland, 2008; Moore and Garland 2003). Further, in keeping with the Scientist Practitioner paradigm, the author would advocate utilising clinical interventions that have a coherent theoretical underpinning in terms of the cognitive and behavioural science (theory) and evidence base (experimental and outcome research) and from this should emerge a cogent clinical treatment rationale that forms the basis of clinical interventions. Frequently within both research and clinical practice behavioural and cognitive theories, rather than being integrated into coherent model, are inelegantly mixed in a way that the science is poorly articulated, and the intervention becomes technique orientated rather than theoretically derived and driven. As a result, there is often a disconnect between the theory underpinning the CBT model and the attendant clinical interventions.

The authors interest in Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) (Gilbert, 2010b) began fifteen years ago following a workshop (Gilbert, 2007b) on the subject delivered by its founder Professor Paul Gilbert. At this time Gilbert proposed that CFT was a method of formulating emotional disorders that can be integrated into any psychotherapy modality. The author also received clinical supervision in the CFT approach over a three-year period (2010–2013) from Professor Gilbert whose own clinical origins lie in CBT. The authors clinical work with patients experiencing persistent, treatment resistant depression led to two important clinical observations. Firstly, that self-criticism was a key feature of their clinical presentation and secondly that standard Beckian clinical interventions that traditionally target self-criticism, notably challenging negative automatic thoughts and modifying conditional beliefs in the context of targeting low self-esteem (Fennell 1998) had limited impact in tackling self-critical thought processes. Further, when using cognitive interventions some patients would frequently articulate, what is referred to as the ‘head heart lag’, namely responding with ‘I see what you are saying (intellectually) but I don’t really believe it (emotionally)’. Among the patients who made such observations, it was often those who described childhoods characterised by sustained emotional abuse (Muris and Meesters 2014; Liu, Alloy, Abramson, Iacoviello and Whitehouse 2009; Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb, and Neeren 2006; Bernet and Stein, 1999) and marked affectionless over control (Patton, Coffey, Posterino, Carlin and Wolfe, 2001), who exhibited high levels of self-criticism and pervasive avoidant cognitive, emotional and behavioural coping strategies. It was these clinical observations that led to the consideration of what factors might be impeding the effectiveness of cognitive and behavioural interventions for clients experiencing persistent, treatment resistant depression and following Paul Gilbert’s work (Gilbert, 2017a; 2007a; 2005b; 2003; 1998; 1995; 1997; 1992)I began to consider the role of shame in depression.

As is discussed in detail in chapter 3, shame and its psychological sequela are articulated across a broad range of academic disciplines and psychotherapy modalities, including Beckian cognitive therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, 1979). However, traditionally in mental health and psychiatry shame is formulated as a symptom of depression. Implicit within this formulation is the assumption that as depressed mood responds to both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic intervention then shame, and its sequela will be ameliorated without the need for targeted intervention. A further area of influence in my clinical and academic work is the cognitive science of depression. The clinical observation that led Beck to develop cognitive therapy was the spontaneous reporting of what he labelled negative automatic thoughts (see Weishaar 1993 p 19). In developing his early theoretical model Beck described negative thoughts as the cause of depression (Beck, 1963). Research in the cognitive science of depression has since demonstrated two well established factors that disprove this assertion. Firstly, the negative content to thought processes observed in depression are mood congruent and therefore a symptom of depression, rather than a causal factor (Bower, 1985; Teasdale, Taylor and Fogarty, 1980). That is, as depressed mood abates so does the negative tone of thought processes. This is a ubiquitous observation in clinical practice and has been demonstrated in experimental studies in cognitive science (see Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and

Shafran, 2004 for a comprehensive account) and in pharmacological studies (Peselow, Robins, Block, Barouche, and Fieve, 1990). The cognitive science of depression has some important observations to make regarding the formulation of self-criticism in depression. These observations are précised below.

The cognitive science of depression

Examining the ‘head heart lag’ phenomena from a cognitive science perspective Teasdale (1999) critiques Beckian cognitive therapy describing the model as a clinical model built from clinical observation and argues that, as a result, it does not account for the cognitive phenomena observed in depression. Here Teasdale is referring to the cognitive science of depression and the processes of self-critical and self-blaming rumination (Teasdale and Barnard, 1993), autobiographical memory bias (Williams and Broadbent, 1986) and over general memory (Watkins and Teasdale, 2004; 2001) which are considered by cognitive scientists to act in concert to maintain depressed mood. This literature is summarised briefly here from (Garland 2016).

When mood is depressed memory more readily recalls past, unpleasant, painful memories and actively screens out pleasant or neutral memories. In the cognitive science literature this is referred to as autobiographical memory (Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Herman, Raes, Watkins, and Dalgleish, 2007). In addition, experimental studies (Raes, Hermans, Williams, Beyers, Eelen and Brunfaut, 2006; Williams and Broadbent 1986) demonstrate that people experiencing depression in comparison to non-depressed controls have difficulty moving through memory hierarchy to a specific level and tend to stop searching at a general description state. This is referred to as over general memory. A consistent finding in the cognitive science literature is that rumination is associated with both intensification and persistence of depressed mood (Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). Further, Watkins and Teasdale (2001) and Watkins, Teasdale and Williams, (2000) found that if rumination is experimentally reduced then memory becomes more specific. This has led Williams and colleagues to conclude that over-general memory and rumination are intertwined in a process where one exacerbates the other and that over-general memory arises in early development and may be linked to early trauma (Henderson, Hargreaves, Gregory and Williams, 2002). Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Herman et al, (2007) conclude that over- general memory arises from a style of processing information in a verbally analytic way which manifests itself as depressive rumination. Importantly this process is outside of conscious awareness and serves the purpose of regulating affect and therefore is negatively reinforced (i.e. maintained) exactly because it enables this affect regulation. Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Herman et al, (2007) therefore formulates over-general memory as an avoidant retrieval style which develops in early childhood and is aimed at reducing the recall of specific distressing memories. Williams,

Barnhofer, Crane, Herman et al, (2007) makes links to the work of Kuyken and Brewin (1995; 1994) who found that over general memory was associated with greater frequency and avoidance of intrusive, depressive memories. Thus, in early childhoods marked by trauma (i.e. emotional/physical/ sexual abuse/neglect) it can be argued that this proposed mechanism of affect regulation would be a useful default survival strategy in order to manage high levels of unregulated fear, anger, sadness and despair. However, this comes at a cost as this process of affect regulation reduces problem solving ability, impairs the capacity to be specific about future events, increases level of hopelessness and prolongs depressed mood (Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Herman et al, (2007). Gilbert’s theory (Gilbert, 2007a) emphasises the role emotional memories play in activating threat systems in the brain, which in turn lead to the implementation of idiosyncratic safety strategies aimed at maintaining relational attachment. Of importance here are shame based traumatic emotional memories (Matos, Pinto-Gouveia and Costa, 2013). This is where this thesis began.

The evidence base for Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

Whilst it is generally considered that the evidence base for CBT for depression is well established (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2009) in recent years there has been questions raised regarding the true effect size of CBT for depression (Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon and Andersson 2010) with specific criticism of the early studies conducted by Beck and colleagues in the 1980’s. Notably, these criticisms include the observation that trials comparing CBT and pharmacotherapy utilised methodological factors that favoured CBT, and as a result, it can be argued such studies may have overestimated the efficacy of CBT for depression relative to antidepressant medication (Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck 2006). Equally, with regards to antidepressant treatment trials some researchers question the veracity of the effect sizes reported on the grounds of publication bias (Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell, and Rosenthal 2008). Such potential for bias has been reported in the CBT literature. Williams (1997) highlights the controversy surrounding the Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky, Collins, Glass, Pilkonis, Leber, Docherty, Fiester and Parloff (1989) research trial comparing CBT with pharmacotherapy and placebo and the lack of transparency regarding questions related to bias in how the data was analysed. In an increasingly politicised research environment, significantly influenced by economic drivers, such issues raise vital questions regarding the ethical practice of research and the dissemination of research findings and how results are utilised at a national and global level. This require researchers to endeavour to be diligent in upholding the principles of the Scientist- Practitioner paradigm and the World Health Organisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Research Practice (WHO 2005) within healthcare research. Hence there has been renewed endeavour to be more impartial and transparent in the reporting of research findings. In their 2010 meta-analysis of psychotherapy for depression study effect size and quality Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon et al (2010) concluded that one of the reasons effect sizes were overestimated in earlier meta-analyses is the inclusion of poorquality studies in those meta-analyses. In their 2010 study, only analysing higher quality studies of psychotherapy for adult depression yielded much smaller effect sizes than previous meta-analyses. This led to the conclusion that even controlling for the type of control group in the study, previous meta-analyses have overestimated the effect size of psychotherapy studies for adult depression (Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon et al 2010).

This led the authors to conduct a further, more robust meta-analysis (Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley et al 2013) of CBT for adult depression both alone and in comparison to other treatments. In conducting the meta-analysis the researchers used a broad definition of CBT and compared CBT with control groups, pharmacotherapy and the following additional psychotherapies: non-directive supportive therapy, Behavioural Activation (BA), psychodynamic psychotherapy, Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), Problem Solving Therapy and what is termed ‘other psychotherapies’. From the 1,237 publications retrieved from the initial literature search, 115 RCT’s on CBT were included in the meta-analysis. Most of the studies used a community sample targeting adults with Major Depressive Disorder as the primary problem and used a Beckian (Beck, Rush, Shaw, Emery 1979) treatment protocol, with two thirds of the CBT treatments offering between 8–16 sessions. Most studies were conducted in the United States. The researchers deployed predetermined quality assessment and data extraction criteria and note that the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis was not ideal in that only 43 of the studies chosen met at least three of the four quality criteria.

Their findings can be summarised as follows:

-

CBT has efficacy as a treatment for adult depression. The researchers compared CBT with wait list, care as usual and placebo or other control group and CBT was shown to be superior to all control groups. However, they note the effect size was significantly smaller in studies that compared CBT with placebo and/or other control groups, compared to CBT with waitlist or care as usual control groups (Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley et al 2013 p 382).

-

The combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy is superior to pharmacotherapy alone in the treatment of depression. However, no difference was found for the efficacy between CBT and pharmacotherapy in direct comparison. The authors note this is not in keeping with previous meta-analyses that found superiority of CBT over antidepressants (Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cuccherat and Blackburn 1998; Dobson, 1989).

-

CBT was no more or less effective than the other psychotherapies included within the metaanalysis. However, the authors note the limitations of some of these comparisons given the small sample size for some of the psychotherapies reported. However, with reference to a previous meta-analysis conducted by themselves they conclude that: ‘differences between psychotherapies for the treatment of depression are small and

unstable across meta-analyses’

(Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, et al (2013 P. 384).

-

The authors also compared Cognitive Therapy (CT) trials with Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy (CBT) trials and concluded CT is no more effective than other forms of CBT.

Defining depression

There is much debate in the health sciences literature as to what is meant by the term ‘depression’ and its associated constructs. Summerfield (2006) observes the following:

‘in everyday usage, as much by doctors as by the general public. ‘depression’ can mean something figurative or literal, can denote a normal or abnormal state, and if abnormal either an individual symptom or a full-blown disorder. And though depression-as-disease may have acquired the status of a natural science category, this was an achievement rather than a discovery’

(Summerfield 2006, p 161)

This observation brings into focus the debate regarding the use of psychiatric diagnosis in both research and clinical practice. Central to modern healthcare and treatment is the concept of diagnosis. That is the classification of specific signs and symptoms of disease in order to define and categorise clinical syndromes. There are two main diagnostic systems used in mental health the WHO International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) (WHO, 1994) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association 2013), the latter being the system most frequently used for defining participant groups in research trials. This tradition of diagnosis also underpins the socalled disorder specific maintenance formulations in the cognitive and behavioural therapies (see Kinsella and Garland 2008) which form the foundations of the protocols designed to use in the randomised controlled trials on which the evidence for their efficacy is predicated. There is much controversy in both clinical and academic circles regarding the concept of diagnosis and how it is utilised in healthcare. Wykes and Callard (2010) offer a commentary on the potential of diagnosis to medicalise the human condition itself and its potential to accentuate feelings of stigma in relation to mental illness. These authors also observe how sole reliance on diagnosis can narrow access to treatment by dictating which treatments are deemed acceptable according to diagnosis.

In this PhD thesis diagnostic criteria have been utilised in order to define the population studied. This decision was dictated by the fact that the group studied in this thesis were a cohort of participants recruited to a research trial which used diagnostic criteria to define the population under study. The study (for which the thesis author was a grant holder) took a ‘pragmatic’ (used here in the everyday sense of its usage rather than philosophical definition described in chapter 3 of this thesis) definition of persistent depression (see Morriss, Garland, Nixon, Guo et al 2016), recruiting individuals who had not responded to treatment in secondary care mental health services for a period of at least 6 months and experiencing a primary unipolar depression which was not a consequence of another psychiatric disorder. The study also included participants who met diagnostic criteria for bi-polar II. The full inclusion criteria for the study sample for this thesis are described in chapter 3 and the study sample defined within the parameters of the concept of diagnosis is shown in table7 in chapter 4.