Anti-Tech Collective Journal

Selections from a Book Review of Endgame, Vol. 2 by Derrick Jensen

Possible Reactions of the Techno-Industrial System to Climate Change

“Man is a Wolf to Man” - Necrology of a Curse

I - A Commonplace for the State

II - From the State to Mercantilism

III - An Axiom to Justfy the Obsolescence of Man in the Face of Technology

IV - Corrections on War and Human Nature

IV: B - Correction on Human Nature

V - Human Needs Rather Than Human Nature: the Nature of Our Freedom

Welcome

This is the first issue of the Anti-Tech Collective Journal, a project evolving out of ATC’s previous publication projects. Within you will find four essays offering different perspectives on different aspects of the Technological Question from four contributors from across the (Western) World.

It is worth letting interested readers know that ATC’s future is uncertain. ATC at its inception and out of necessity adopted a highly decentralized approach for the group. Since then, its main functions have been networking within the “anti-tech” network and some amount of public education through hosting public discussions and producing written material for public consumption (such as this).

All of these functions were and are performed by active members of the group volunteering their time, energy, and resources. As time goes on, the Technological Crisis worsens and things become increasingly unstable. Accordingly, most of the group’s active members have had to withdraw their support and direct it instead to other more centralized projects, pressing personal matters, and so on.

Putting together and attempting to edit this collection of essays has been my main contribution to the group over the past few months. It has been a largely solo project on which I’ve had to learn a lot as I’ve went. Please be forgiving of both small and glaring imperfections of which I am either unaware or about which I can do nothing at the moment due to various limitations.

After this publication, it is unclear if enough energy will remain in the group to keep it even semi-regularly producing material. If the energy dissipates, we will place the ATC website in ‘stasis’ either until the funding for the website dries up or until one of the remaining members revitalizes it. The ATC email account will remain active so long as there is at least one person keeping an eye on it and willing to respond to possible inquiries. We will be sure to update both our email subscribers and the website should we decide to decommission or pause either.

If you would like to more definitely see that ATC keep going, consider contacting the group or even becoming an active member. These are the main requirements: a working mind; some self-motivation; a genuine appreciation of Wilderness; and an unfavorable opinion of Technology.

Editor of and contributor to this anthology,

Darrell

Contents

Selections from a Book Review of Endgame, Vol. 2 by Derrick Jensen

Possible Reactions of the Techno-Industrial System to Climate Change

“Man is a Wolf to Man” - Necrology of a Curse

A Reaction to Kaczynski

Selections from a Book Review of Endgame, Vol. 2 by Derrick Jensen[1]

Squalor

[...][2]

Introduction

In a rather revealing letter from Derrick Jensen to Ted Kaczynski dated November 6th, 1998, Jensen writes: “...one of the things I really like about our correspondence is that normally I am always the one who pushes people to think more deeply and to push more radically and/or militantly, and you do that for me.” At first glance, one could draw some superficial parallels between Jensen’s anti- civilization and Kaczynski’s anti-tech ideologies, since it seems that the two share the same overarching message: the industrial system must be brought down in order to save wild nature. However, when one familiar with Kaczynski’s works goes on to read Jensen’s Endgame, they will see that the problem isn’t just that Jensen is far less radical than Kaczynski, but also that Jensen gets bogged down by self- indulgent philosophizing, obsessive moralizing, and a strong fixation with victimization that fails to approach the core issue of the technological system in a rational and analytical fashion. This failure to rationally approach the root of the problem taints everything in Jensen’s writing, from his faulty understanding of the issues inherent to the technological system to his vague, confused, and bare-bones attempt at offering any practical steps for those who want to do something productive about it. Quite possibly his most egregious error is his strong tendency towards leftist thinking, which is fundamentally incompatible with his environmentalist goals. While Jensen’s work arrives at one of the same conclusions as Kaczynski—that in order to save wild nature the industrial system must be brought down, sooner rather than later—it misses the mark entirely in nearly every other respect. In the opinion of this writer, this book is actively harmful, in that it could draw in readers that may sense that there is something wrong with the modern world and feel that something needs to be done about it, and then leave them with a confused understanding of the root problem (that is, the technological system) and what needs to be done about it.

Jensen, “the philosopher poet of the ecological movement,”[3] has made a name for himself in certain environmental circles as a writer that opposes industrial civilization. He is a founding member of the organization Deep Green Resistance (DGR),[4] a group that aims to bring down industrial civilization in order to save the planet. While this sounds well and good on its own, even the quickest glance at DGR reveals that the group is happily repeating many of the exact same mistakes that the Earth First! movement made decades ago. Though the media likes to prop up Deep Green Resistance as an organization that is an actual threat to the current system, or even something akin to the type of organization that Kaczynski outlines in Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How,[5] Deep Green Resistance is nothing more than another leftist organization that will mislead and ultimately discourage and burn out individuals who want to actually do something about the system. A thorough takedown of Deep Green Resistance warrants an entire essay on its own, but in short, the group makes four irredeemable errors:

-

They do not have a single, primary, concrete goal. They are pulled in many directions, aiming to “dismantle gender and the entire system of patriarchy which it embodies”, and bring down “[class inequality], white privilege, misogyny, and human supremacism.”[6] By focusing on multiple goals, rather than the overarching goal of ending the technological system, the group pulls itself into many different directions and renders itself ineffective.

-

They believe that they can build “just,” “sustainable” societies after the collapse of the industrial system. In addition to this, they adopt a paradoxical and self-contradictory approach in advocating a reform of industrial society while also the destruction of it.[7]

-

They focus on victimization issues that are irrelevant to a group whose aim is to bring down industrial civilization in order to save wild nature. In fact, it is worse than irrelevant, since such a focus: (a) attracts leftists that will corrupt the movement and shift the focus to social issues rather than ending the system, and (b) distracts vital energy and attention from what should be the only goal.[8]

-

They encourage the formation of underground cells that carry out acts of industrial sabotage. Although these cells are (in theory) supposed to be composed of individuals that are not involved in the DGR organization, this tacit endorsement of incitement is a foolish strategic error that risks serious sanction by the system’s authorities. An above-ground group opposed to the technological system must remain strictly legal and have no association with any sort of “underground,” so as not to compromise the security of the entire movement.

[...] The thesis[9] of Jensen’s work essentially boils down to this: we live in a “culture of abuse,” and industrial civilization itself is akin to an abusive partner. Since you cannot reason with an abusive partner in order to get them to see the error of their ways, we can infer that we also cannot reason with those “in charge” of the industrial system in order to get them to voluntarily stop destroying wild nature. Since we live in a “culture of abuse” that seeks to dominate wild nature, women, children, indigenous people, etc., even if the people “in charge” were replaced, their replacements would also seek to dominate wild nature since those that live in industrial civilization are taught from birth[10] to hate wild nature and see it as theirs to dominate. Thus, in order to stop the ravaging of the planet, Jensen argues that we have no choice but to engage in violence, and therefore dismantle industrial infrastructure. Jensen’s worldview highlights the major flaws we will be looking at in this work, namely: his masturbatory philosophizing, his strong propensity towards victimization, and his strict view of cultural beliefs as being the main culprit of environmental destruction.

Now, let’s take a deeper look at each of these flaws.

Refuting Pacifist Arguments

[...]

It is a bizarre choice, spending most of the first half of the book attacking the foundations of pacifism rather than the actual issue at hand: why the technological system itself must be destroyed and how to go about it. Jensen spends over two hundred pages making long, droning arguments about how pacifism will accomplish nothing, presumably aimed at the average reformist who has been brainwashed their whole life to believe non-violence is among the highest virtues. It’s incredibly unlikely that these types will be stirred out of their conditioning through counterargument after counterargument, as any devout pacifist will be completely turned off by the amount of human suffering that the collapse of the technological system will entail so as to be useless to a revolutionary movement that seeks to end it.[11] [...] Despite his claims otherwise, when reading this work one gets the sense that Jensen simply enjoys engaging in these long-winded philosophical arguments and does not want to put in the work to come to any significant conclusions about the practical application of his ideas. This book doesn’t exist to sway the average pacifist, it exists because Jensen does not want to take practical action against the system but merely gets a kick out of philosophizing, and perhaps feeling like he is delivering a truly revolutionary message in the process. He openly admits time and time again that practical action frightens him. Repeatedly Jensen reminds the reader: “I’m glad I’m a writer”[12] (and nothing more).

It should be obvious that a blind adherence to non-violence is pushed by the mainstream media, taught in schools, and instilled in modern individuals through other means of propaganda because a meek and docile population will never be a threat to the system (and because an obedient population is necessary for the smooth and orderly functioning of the system). Abiding by the morality that the system itself sets forth for its own preservation will accomplish nothing to bring down the system itself, that’s why such morals are touted by the system in the first place. It takes Jensen over 200 pages to argue something that can be done in a page or less. Allow me to argue for the (strategic) use of violence (when necessary) in a much more straightforward and simplistic way:

Technological progress has caused extensive damage to the natural world, and if left to continue unabated will result in biosphere collapse, spelling the end for all complex lifeforms on Earth. The only way to circumvent this fate is to bring about the collapse of the technological system. In order to bring about this collapse, revolutionaries will need to use all available means at their disposal and act without hesitation. Due to the fact that the technological system uses violence in order to sustain itself, and during its disruption various organizations will use violence in ruthless competition for power, revolutionaries will need to use violence when it is strategic to do so in order to achieve their goal of taking down the technological system. Those that disagree will be useless as revolutionaries, for their irrational commitment to nonviolence is emblematic of their enslavement to the values of the system or the fact that they do not truly want to see the technological system eliminated, at least not to the extent that they are willing to take the necessary measures to save the biosphere.

In engaging so deeply with pacifist arguments, even if to refute them, Jensen offers them more weight than they are worth. Cowards and conformists with a deep- seated aversion to violence won’t be convinced to abandon their values through rational argument and should not be the audience that a group truly opposed to the technological system should dignify or attempt to reach. It’s a waste of time for everyone involved. In order to form a truly radical, revolutionary movement against the technological system, one needs to reach a small minority of individuals[13] that will have no qualms about getting their hands dirty. These people will not need to be endlessly preached to, and will only be turned off by arguments for the obvious that do not respect their intelligence and only waste their time.

[...]

[For the rest of the review, visit the Wilderness Front website:

https://www.wildemessfront.com/blog/endgame]

[Copyright 2023 by Anti-Tech Collective. All rights reserved. This is published with

the permission of the copyright owner.]

Possible Reactions of the Techno-Industrial System to Climate Change[14]

Karaçam

The techno-industrial system faces a grave danger: climate change.[15] It is dependent on the resources of the biosphere to function. For this reason, the stability of the biospheric functions is crucial for its effective functioning. Climate change means a sudden change in the conditions of the biosphere. According to The Economist’s October 30th (2021) issue, it is changing the rain patterns, water cycles and will have adverse effects on crop yields. It is increasing the frequency, intensity, and duration of droughts and heatwaves. The great ice sheets of Greenland and Eastern Antarctica are destabilizing and this, in turn, makes it easier for mid-sized hurricanes to intensify into powerful storms causing enormous damage. Sea levels are rising and threatening coastal cities. The biodiversity of the oceans is under stress due to ocean acidification and sudden change in sea temperatures. The tropical zones are becoming virtually unlivable. Massive wildfires burning huge areas are becoming more and more frequent. All these are happening extremely fast and forcing the adaptive capabilities of the techno-industrial system. It should either adapt itself to these new conditions by changing itself (its energy infrastructure, the consumption level of its members, etc.) or try a desperate move in its fuite en avant and take on its own hands the governing of the atmosphere.

The Economist’s October 30th (2021) issue dedicates a special report to this dilemma, and it investigates some possible answers to this urgent threat. The Economist represents the ideological orthodoxy of the techno-industrial system.

For this reason, following its arguments and suggestions on this issue might help discern the techno-industrial system’s possible reactions to climate change.

As The Economist mentions, the use of fossil fuels was the most transformative event after agriculture. It brought a massive growth in population and people’s “wealth.” But the side-effect of this development, the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, has a “potentially show-ending role.” Thus, world governments should embark on a vast project. They should stabilize the climate. In The Economist’s words, this project will entail:

The curve-flattening climate stabilization will be the result of deliberate interventions in both the economy and nature on a global scale. And it will be maintained, if it is maintained, by human institutions with the astonishing, and possibly hubristic, mandate of long-term atmospheric management.

The Economist explicitly declares that to ensure the existence of the techno- industrial system, it is necessary now to embark upon a comprehensive transformation not only at the level of economic infrastructure but also on Nature on a global scale. The system should embark upon long-term atmospheric management. In the special report, other, more traditional answers are also evaluated and suggested, but these evaluations are always ending with implicit desperation about the shortcomings of the “traditional” solutions or with a reminder of the fact that it is now too late to rely only on these “traditional” remedies. Let’s look with The Economist at what these more “traditional” remedies are.

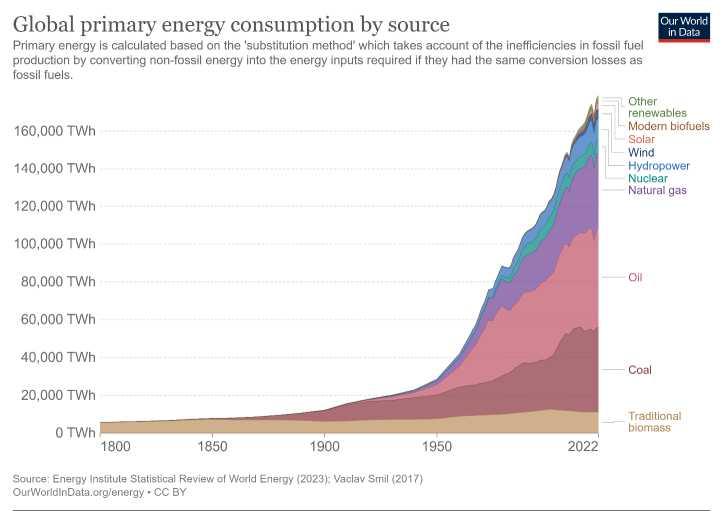

The most publicized of these “traditional remedies” is that the techno-industrial system should quit its fossil fuel addiction. Things don’t look good in that regard. Despite the global UN Conventions and pledges to decrease fossil fuel consumption, it increases year by year. According to The Economist, “in 1992 78% of the world’s primary energy -the stuff used to produce electricity, drive movement and provide heath both for industrial purposes and to warm buildings- came from fossil fuels. By 2019 the total amount of primary energy used had risen by 60%. And the proportion provided by fossil fuels was now 79%.” Therefore, after all the pledges to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere” in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 to Paris in 2015, the absolute consumption of primary energy sourced by fossil fuels increased by 62%!

The Economist tries desperately to appear hopeful about the “new,” “alternative” energy sources: wind and solar. It boasts about the reduced cost of wind turbines and solar panels. But there is no indication that wind and solar are replacing fossil fuels. The Economist gives only statistics on their absolute growth. “In 2020, the share of the world’s energy generated by solar panels grew by 21%, which points to a doubling every four years. Wind, which now supplies twice as much energy as solar, is growing more slowly, by 12% a year.” These figures only represent the absolute growth in solar and wind energy production; they are typical considering the ever-expanding energy hunger of the techno-industrial system. They don’t indicate that wind and solar power are replacing fossil fuels. As can be seen in the graph below, energy consumption increases for all the sources in absolute numbers. The trend of the traditional biomass (woodfuels, agricultural by-products, and dung burned for cooking and heating purposes) in the below graph is illuminating. It is the source of energy humans have been using since they discovered the use of fire. But as we can see in the below chart, it hasn’t been replaced by coal or oil after the industrial revolution. It continues to be consumed at its peak level. In energy supply, one source of energy doesn’t replace the other. As far as there is available energy, the techno-industrial system adds one source on top of the other and increases its total energy consumption. This is and will be the case with the solar, wind, and other “alternatives;” they will be added to the total (increasing) energy consumption without replacing the fossil fuels (which still represents the gross majority).

It is clear that fossil fuels will continue to be burned in the foreseeable future, and the absolute consumption of these fuels hasn’t peaked yet. The Economist suggests carbon pricing as a remedy. Carbon prices would artificially increase the cost of fossil fuel energy generation and make it more expensive than solar and wind. It is such a pipe-dream. Applying this strategy with the necessary rapidity and brutality to cut back emissions drastically in the required time is virtually impossible without shaking the foundations of the system. It would mean economic collapse, enormous decreases in living standards, and extreme backlash from the population. Much more timid policies encountered angry backlash in recent times.

Apart from carbon dioxide, there are other greenhouse gases: Methane (from the natural gas industry, rubbish heaps, and livestock), nitrous oxide (mostly from agriculture), and chlorine-bearing industrial gases. Again, there is no hope of a timely solution to these emissions. “Big reductions in agricultural emissions of methane and nitrous oxide emissions will take time,” says The Economist. Apparently, the recent propaganda campaign in favor of veganism isn’t producing the expected results.

Another problem is “sulfur-dioxide emissions which are mostly associated with burning coal and heavy oils.” Burning coal and heavy oils produce small airborne particles of sulfate, offsetting greenhouse warming. Therefore, decreasing the consumption of coal would exacerbate in the short term the climate change. The system is on the horns of a dilemma here.

In Paris in 2015, governments made pledges of voluntary reduction in CO2 emissions, so-called “nationally determined contributions (NDCs).” NDCs are not binding commitments, and there isn’t any regulatory power that would ensure the fulfillment of these pledges. They are castles in the air. But even these pledges wouldnt be enough to limit global warming to 2° C, let alone to 1.5° C. “ [E]ven in Paris, it was clear that the 1.5° C limit could not be met by emission reductions alone. They would have to be supplemented by something else: the withdrawal of CO2 from the atmosphere by means of ‘negative emissions.’” But again, despite all the noise regarding the need for negative emissions, there isn’t any effective method today to achieve it. “Mechanisms which can provide lots of reliable CO2 removal remain, at best, embryonic,” sighsThe Economist. We will come back to this below.

Besides, there is “the Asia problem.” More than half of the global population lives there, and Asian countries constitute a great part of the so-called “developing countries.” They aspire to raise their citizens’ living standards; it can only be done by increasing energy consumption. On top of that, these countries have increasing populations. They have to grow economically in order to absorb the new generations into the economy. Otherwise, they might experience economic crises, massive unemployment, and social instability. The Economist says that “two-third of global coal produced there” and “Asia produces most of the world’s cement and steel.” As if this is a vice unique to Asian countries, and the developed countries of Europe and North America extricated themselves from this nasty habit of coal, cement, and steel. But this is far from the truth. If developed countries seem “better” in that regard, the reason is that they mostly shifted their manufacturing sectors to Asia for lower production costs. They have exported the emissions; their economies continue to depend on coal, cement, and steel.

In this special report, we witness inside-the-system debates on capitalism and degrowth. Third-wave leftists,[16] like Naomi Klein, claim that it is impossible for capitalism to wean itself from fossil fuels. Since capitalism is driven solely by profits, the fossil-fuel industry will insist on putting profits ahead of the threats of climate change. Therefore, to get rid of fossil fuels, it is necessary to get rid of capitalism. As good first-wave leftists, the writers of The Economist refute this claim. According to them, to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, new technologies and new investments are necessary. And capitalism has proven itself the most successful economic system to provide both. “All that is needed is to find ways to ensure that growth does not have to be linked to rising CO2.” The Economist uses the below formula to demonstrate the relationship between development, energy, and CO2 emissions.

CO2= population x (GDP/capita) x (energy/ GDP) x

(CO2/energy)

According to this formula, to decrease the CO2 emissions, one has to cut back either population, GDP per head, energy used per unit of GDP, or carbon emissions from that energy. The Economist explains that reducing population using a long-term strategy “is not a course of action that governments can effectively and decently pursue.” We also agree with that. First, it is impossible to implement a long-term population control globally as a concerted international effort. Second, as long as the system needs mass human labor for its functions, population control is detrimental to the economies of individual countries. As we have witnessed in China’s one-child policy, in addition to problems such as destroying the balance of sex ratio in a population, population control increases the dependency ratio enormously. Increased dependency ratio has enormous adverse effects on the economic performance of a country. For these reasons, besides the impossibility of a concerted international effort of population control, individual countries also won’t implement a drastic population control strategy that would be rapid enough to curb the CO2 emissions in time.

What about GDP per head? It has increased enormously since the Industrial Revolution thanks to the concentrated energies humanity obtained from fossil fuels. As The Economist also mentions, if GDP per head continues to increase, the improvements in energy efficiency and carbon intensity would merely keep carbon emissions stable. So is it necessary to decrease GDP, roll back the growth to save the system from climate change? The Economist gives several reasons why it would be impossible to implement degrowth consciously according to a strategic plan. These reasons are not wrong in themselves, but they miss the fundamental, underlying causes why it is impossible to implement these kinds of long-term comprehensive plans. But first, let’s look at the reasons The Economist gives for the impossibility of such an action:

1. To implement a long-term reversal of growth, everyone else (i.e. the entire human population) should be persuaded to consume less. Anybody who has a modicum amount of common sense will know that this is impossible. Therefore, governments should implement a dictatorial policy to ration the consumption of their citizens. However, as The Economist puts it, “[a]n overt policy of deliberately slowing, stalling or reversing long-term growth, even if presented as being for the good of the world, is a highly unpromising platform on which to win elections.” From this citation, it sounds like only “democratic” countries would face problems rationing the consumption of their citizens. Authoritarian regimes also need to seek the consent of their populations as long as human labor power is necessary for the functioning of the economy. The consent is primarily produced in today’s modern world (where humans live in a modern zoo separated from their natural habitats) by consumption possibilities (electronic gadgets that isolate people in a virtual world to make them forget their dismal existence, the pursuit of commodities that offers people a pseudo purpose in this purposeless world, etc.) which require growth. In the short term, in which a response should be given to climate change, mass human labor will continue to be necessary for the system’s functioning. Therefore, it would be impossible to play the degrowth card that would affect immensely the living standards of the masses.

2. Decarbonisation can only be realized by massive investment in renewables[17]; this is especially true for emerging economies. Much of the investment necessary to build the new “renewable” energy infrastructure should come from the developed countries, and without growth, there won’t be any incentive for investment.

3. Decarbonisation process will require accelerated innovation. As an economic system, capitalism has the best record of fostering innovative ideas and implementing them on a broad scale. The system will need capitalism’s that feature. According to The Economist, “better ways of storing energy, of heating houses, of cooling houses, of processing crops, of growing crops, of powering large vehicles, of producing plastic and more” will be needed to reduce the CO2 emissions. These cannot be done in the framework of a “contracting, low-demand, low-investment economy.”

The reasons that The Economist gives for the impossibility of planned degrowth misses the most fundamental reasons. First, it is impossible to direct the development of a complex system -especially a system as complex as the global techno-industrial system- by devising a long-term plan and implementing it in real life. Complex systems are composed of numerous components. It is impossible to know the myriad of relations between these components; how they affect each other in self-reinforcing feedback loops. Planned degrowth would require a long- term plan that should be implemented globally. One has to know the consequences of this plan on the global system, and this is impossible. There will always be unforeseen consequences of the actions taken to reach the planned intention. Besides, the aim or the determination of actors who undertake this plan can change in time, and even the actors themselves can change or disappear.[18]

The other reason that makes impossible the implementation of long-term degrowth is the existence of the “self-propagating systems.”[19] A self-propagating system is a system that tends to promote its survival and propagation by either indefinitely increasing its size and/or power[20], giving rise to new systems that possess some of its own attributes or doing both of these. Nations, corporations, labor unions, churches, political parties, mafia organizations, etc. are all self-propagating systems. The Darwinian selection processes that function in biology (natural selection) are also operative in environments where these systems are present. This selection process favors self-propagating systems that have the most conducive characteristics for self-propagation. As a result, these systems tend to propagate themselves and squeeze out or absorb other self-propagating systems that don’t have these characteristics. They are in constant “competition” with each other. This competition isn’t so much a deliberate antagonism but more of an unconscious process. Self-propagating systems that expand their functions by incorporating more energy and material into their metabolisms will increase their material power; thus, they will absorb or side-step other self-propagating systems. Therefore, implementing a voluntary degrowth strategy would be a sure recipe of disaster for the systems that pursue it. They would relinquish the advantage to the systems that relentlessly seek their aggrandizement and expansion by absorbing each passing day more energy and materials. Systems implementing degrowth would be eliminated, devoured, or side-stepped.

We find the discussion on capitalism and all the noise the third-wave leftists make on it utterly meaningless. First of all, it is not clear what they exactly mean by “capitalism.” But it seems that they imply an economic system designed, created, and managed by some selfish, greedy people (financial speculators, big oil, one percent, etc.) who try to maximize their profits whatever may come. But “capitalism” is not something consciously designed, created, and managed. The things that are generally associated with “capitalism” (financial instruments, modes of property ownership, social classes, economic theories, etc.) have developed during the evolution of complex human societies. They aren’t consciously designed and implemented by anybody for a definite result. They are the result of the Darwinian selection process that is operative on human societies. Those properties that are more conducive for the growth/development of a society end up being selected by this blind selection process. And the phenomenons that are generally associated with “capitalism” came into being through this process. They developed and spread globally with the advancements in technology and accompanying complexification of human societies. By pointing out as the main culprit to “capitalism” as if it is consciously preferred and deliberately continued by some people, and therefore it can be eliminated and replaced by the decision of some other people, they deflect the attention from the real problem: The existence of a most complex human society that is primarily grounded on material conditions (energy and material resources, the technological infrastructure that makes use of these resources, and the resulting consequences in demography, ecosystems, etc.), not on the property relations, class structure of the society, financial speculation, greedy oil businessmen, etc. Besides, despite their endless rhetoric about alternatives to “capitalism,” it is impossible to hear any alternative from them. Apart from the tried and abandoned command economies of socialist countries, what is the alternative to “capitalism”?

In sum, according to The Economist, the techno-industrial system isn’t capable of affecting a change at the first two variables (population and GDP per capita) of the above CO2 equation. Population control is impossible. It will continue to rise until the middle or the end of the century and will continue to be an increasing factor of CO2 emissions, let alone a decreasing factor. Implementing a degrowth strategy and decreasing the second factor is also impossible for the techno-industrial system. On the contrary, growth is necessary to face climate change. Since the techno-industrial system can’t shut itself off, to restrain its effects on the earth’s atmosphere and save itself from the abrupt changes that would cause, it should implement a colossal transformation in its energy infrastructure. This transformation will require accelerated technological development and the implementation of these new technologies on a global scale. The only way to realize these are investments and economic growth. “Grid-linked gigawatt world of sky-scraper-topping turbines and solar farms” should spread over the landscape. The technological advancement should find remedies to their intermittency problem (wind turbines and solar panels can’t function at the unsuitable wind and cloudy weather, respectively). But, these “traditional” remedies won’t be enough to limit the effects of climate change to the acceptable levels for the system, at least in the period it is needed. Therefore, something more is necessary.

One option for “something more” is the so-called negative emissions. The following numbers given by The Economist demonstrate the necessity of negative emissions for the system: “The cumulative CO2 emissions budget consistent with a 50-50 chance of meeting the 2° C goal is 3,7trn tonnes. The budget for 1.5° C is just 2,9trn tonnes. With 2,4trn tonnes already emitted, that leaves a decade of emissions at today’s rates for 1.5° C, maybe 25 years for 2° C.” That means there is no place to go. If the system can find a way to suck back some of the CO2 already emitted, it can gain more time to change or adapt itself to climate change. Several methods are floating in the air for “negative emissions.” But most of them, like direct air capture or increasing the alkalinity of oceans by adding lime to it to increase the dissolution rate of carbon in seawaters as carbonate ions, are science fiction and fantasy right now. They would create more problems than solutions: They would need massive amounts of energies to implement and have unforeseen adverse effects on ecosystems.

A more plausible method of negative emissions for the system would be biomass energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Plants that capture carbon from the atmosphere through photosynthesis would be burnt in power stations as fuel, and the resulting carbon emissions would be captured and stored. Negative emissions scenarios in the climate models (such as United Nations’ IPCC models) rely on this method. But one can easily imagine the enormous dangers that this method would create for wild Nature. As The Economist also mentions, “its large- scale deployment requires vast amounts of land be turned over to growing energy crops: in some estimates, an area equivalent to up to 80% of that now used for food crops would be needed.” When one considers the ever-increasing energy demands of the techno-industrial system, the area needed to grow the plants that will be burned in power stations would only grow. Large tracts of wild ecosystems such as forests and prairies would be turned into fast-growing, industrial tree plantations. Since this method would have the “green” and “sustainable” image, it would be done with more impunity and even with a claim of restoring “nature.” In fact, according to The Economist, this has already happened in Chile: “In Chile, government subsidies helped establish 1.3m hectares of tree plantations since 1986-but a rule requiring that this expansion should not happen at the expense of native forests was not enforced. As a result, the program actually reduced the amount of stored carbon by some 50,000 tonnes.” But even the large-scale deployment of BECCS doesn’t look promising enough to solve the system’s climate change problem in time. The area needed for the large-scale deployment is too big. The system needs its agricultural land to feed its enormous population. As the above example from Chile demonstrates, if tree plantations replaced wild forests, the net result would be more carbon in the atmosphere, contrary to the aims of the negative emissions program.

The other possible reaction, and possibly the most dangerous one for the wild Nature, is that the techno-industrial system might attempt to “govern the atmosphere.” As we said, The Economist represents the orthodoxy of the ideology of the techno-industrial system. In this special report, the chain of argument implicitly points toward the “governing of the atmosphere” as the best (or even the only) possible option to “fix” the climate change in the short time frame that it should be dealt with. Geoengineering is still controversial; there are many uncertainties regarding its consequences, who has the authority to implement it, etc. That is why we don’t see (yet?) blatant advocacy of geoengineering in this special report or the media in general. But we see it discussed more and more as a possible option, and a magazine like The Economist defends and proposes it as a solution shows us where the trend is going.

There are several proposed methods of geoengineering, but the most popular and the most studied one in the models is solar geoengineering: Spraying reflective particles in the stratosphere so that they reflect sunlight into space and create a cooling effect that balances the greenhouse effect of CO2 in the atmosphere. According to The Economist, geoengineering is cheap, “it seems likely that putting a veil into the atmosphere would be comparatively cheap,” and it could be undertaken “by a relatively small fleet of purpose-built aircraft.” The Economist sees the application of a solar-geoengineering program implemented with global cooperation as the miraculous solution. If only the world as a whole could come together and implement a solar-geoengineering scheme collectively, it would provide “climate benefits to almost everyone and serious problems to almost nobody.” It would give the system breathing time to adjust its energy infrastructure accordingly. And when the CO2 level was low enough, “the governing of the atmosphere” would be phased out, leaving behind a stable climate.

Of course, this optimistic scenario of “fixing” the climate ignores some crucial and insurmountable obstacles that such a venture would inevitably face. Even if we assume that the whole world could come together and implement a global solar geoengineering scheme, we can be pretty sure that the consequences of such a scheme would be quite different than expected. Earth’s atmosphere is a complex system. We don’t know exactly how it functions, the feedback loops among its components, and the relationships it has with the rest of the biosphere. Our models of atmosphere or climate aren’t the reality itself but an approximation and simplification of it. When such tinkering with the atmosphere begins, there would be inevitably unforeseen consequences. To mitigate the effects of these unforeseen consequences, more tinkering would be necessary. And this process would go on in a self-reinforcing feedback loop until the natural mechanisms that keep the chemistry of the atmosphere and climate in certain limits lose their function. When that happens, the stability of the earth’s atmosphere and climate would be dependent on the artificial governing of the techno-industrial system. In an eventual collapse of the techno-industrial system, the artificial governing of the atmosphere would cease, and its composition might reach a state where it can’t sustain complex living organisms.

On the other hand, mitigating the effects of climate change with the artificial cooling of geoengineering would relieve the pressure of reducing CO2 emissions. The techno-industrial system is still essentially dependent on fossil fuels for its energy needs. With an artificial method of suppressing the effects of burning fossil fuels, companies and governments would increase their CO2 emissions with more impunity. That, in turn, would create the necessity of more intense intervention to the atmosphere and so on.

But more probably, solar-geoengineering won’t be implemented as a globally concerted collective endeavor. It is improbable that all the world governments come together in concerted action to implement such a plan. Solar geoengineering would have different effects on different countries. Some will oppose such an endeavor, some will be more reticent, and some will want an immediate implementation. They will have diverse ideas about how to implement it. Since the application of geoengineering is relatively cheap, one or a group of more eager countries might choose to implement it on their own and can do it with their own resources. As we have said, we can’t know the precise consequences of geoengineering beforehand. One possible consequence would be the changing of the water cycles. Countries that implement unilaterally solar-geoengineering would choose to pursue primarily their own benefit; they might cool part of the planets while disrupting water cycles in other parts producing negative consequences for other countries. That might elicit reprisals in the form of more solar- geoengineering, and the atmosphere’s chemistry might be devastated more rapidly with every country tinkering with the atmosphere for its own benefit. But regardless of how it is carried out, “governing the atmosphere” would represent the most comprehensive attack on the autonomy of wild processes.

The techno-industrial system is in a relentless fuite en avant.Its functions create disruptions in the processes of the biosphere. But since it still is dependent on wild Nature for its existence, these disruptions also create threats to its effective functioning and survival. To mitigate those effects, it comes up with palliatives in the shape of techno-fixes. But these techno-fixes, in the end, create deeper problems. In its headlong escape from the problems its existence generates, the system keeps getting more complex, bigger, and bulky. Its disruptive effects on biospheric processes get more intense, destructive, and numerous. Climate change and the system’s reactions to it is one representation of this process. The techno- industrial system has already littered and continues to litter the environment and the wild ecosystems with the wind turbines and solar panels in its quest of adapting its energy infrastructure to climate change. It created enormous damages with the mining operations necessary to procure the needed metals to produce wind turbines, solar panels, electrical batteries, etc. It plans to turn massive areas into industrially produced tree plantations to feed its never-ending hunger for energy with more “sustainable” methods. But all these aren’t enough for its timely adaptation to the new climate that it is creating. Therefore, it is getting ready to attempt the most daring of its endeavors yet: “governing the atmosphere.” Apart from its complete destruction, nothing will stop it; its fuite en avant will only continue with accelerated speed and devour the remaining autonomous wild processes.

“Man is a Wolf to Man” - Necrology of a Curse[21]

Romuald Fadeau

Introduction

The proverbial habit soon poisons thinking and uttering just these few words is usually enough to put an end to discussion and to ignite endless debate characterized by awkward binaries: “is man good or evil?” The answer is bound to overlook the fact that our opening quote carries within it a far more technical implication than a simple moral judgment: man’s self-image had to be destroyed in order to engender the historic rise of the State first and then of the liberal Market, both of which were necessary developments in the process leading to global Technological control.

I - A Commonplace for the State

The end to civil war was Liberalism’s promise at the time of its philosophical birth. With the specter of the Wars of Religion and the First English Revolution looming large, the desire to redirect the warlike inclinations of human beings towards economic satisfaction was absolutely understandable.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) in On the Citizen (1642)—ten years before Leviathan —writes the chiasmus that inspired our title:

That Man to Man is a kind of God; and that Man to Man is an arrant Wolfe. The first is true, if we compare Citizens amongst themselves; and the second, if we compare Cities.[22]

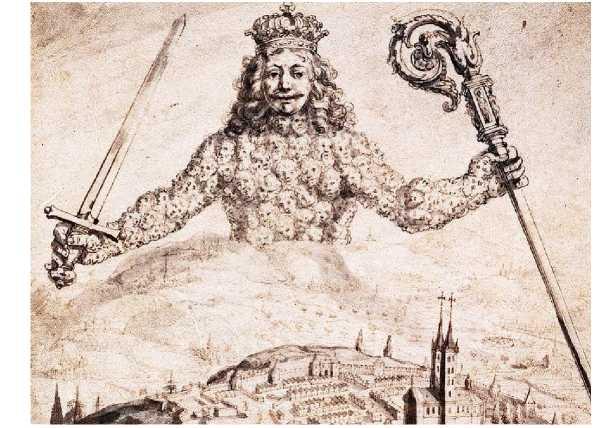

This oft-repeated quotation quickly takes on richer meaning: as a pioneer in political science, Hobbes created the concept of the “state of nature” in opposition to the social state. This conceptual fiction served to clarify the meaning of civilized life which depends on the State for internal peace. What could be more normal for an exiled author, fleeing a civil war in England, than to act in his own way in favor of peace? But the foregoing would be incomplete without a brief look at the nature of the State as theorized by Hobbes. As a picture is worth a thousand words, here is the frontispiece to The Leviathan, illustrated by Hobbes himself:

As Hobbes wrote:

This submission of the wils of all those men to the will of one man, or one Counsell... is called UNION... Now union thus made is called a City, or civill society, and also a civill Person ; for when there is one will of all men, it is to be esteemed for one Person.[23]

This giant wielding both a sword (military power) and a bishop’s crozier (religious power) symbolizes the union of two previously opposed powers: temporal and spiritual. In doing so, Hobbes heralds political modernity and the absolute triumph of the State. However, the devil is in the details. Play close attention to what makes up this giant’s skin: human heads. In the political union, humanity is set aside to make way for the State, which in turn becomes this Wolf-Man. In Hobbe’s politics, State is a wolf to State, and the much-vaunted internal peace is in fact nothing more than the submission of the human mass to the absolute power of the sovereign. Bernard Charbonneau (Jacque’s Ellul’s best friend) captured the nature of the State:

The State creates the isolated, interchangeable individual. Instead of considering the diversity of men, it reduces them to what is identical; at the outset, all individuais are equal - before the law of the sovereign. And it is from there that he classifies them according to their usefulness. [...]

The vigorous State is one animated by the will to power, the decrepit State is one from which it withdraws. The State is power; to speak of an authoritarian, centralized or hierarchical State is to commit a pleonasm; to speak of a liberal State is to enunciate a paradox. Pluralism and freedom are not in its nature, and creative activity is not its business, but that of individuals and groups. A State may be officially federal or democratic, but left to its own devices it will soon become centralized and authoritarian. Every President of the Council is an aspiring dictator, just as every policeman is an adversary of individual freedoms. Because their raison d'être is not people, but efficiency in action. And it is not the day when the sovereign commands to act that tyranny threatens, but when, weary of asserting themselves in the face of the State, men give the name of Liberty to the necessity: political constraint.[24]

Louis XIV, reader of Hobbes, gave his letters of nobility to the State and was the perfect gravedigger of small communities’ freedom.[25] The land that had become a “nation” through State action was reduced to perfect servility under the pretexts of peace and order. But the peace of the State is equal to the peace of the prison. Disoriented by the belief that he is the natural enemy of his fellow human beings, man has no choice but to see himself stripped of any real control over his existence —individual or collective. All that’s left for him to do is watch time fly by without ever having a grip, as if held behind bars, in complete submission to power, itself condemned to competition.

II - From the State to Mercantilism

Hobbes’ quote should not be understood solely in terms of rivalry between states. What he says about the origin of societies is imbued with this same selfish distrust. His conception of the state of nature is based on mutual fear of men, not on the social nature of political animals:

We must therefore resolve, that the Originall of all great, and lasting Societies, consisted not in the mutuall good will men had towards each other, but in the mutuall fear they had of each other [...]

Manifest therefore it is, that all men, because they are born in Infancy, are born unapt for Society. Many also (perhaps most men) either through defect of minde, or want of education remain unfit during the whole course of their lives; yet have Infants, as well as those of riper years, an humane nature; wherefore Man is made fit for Society not by Nature, but by Education.[26]

For Hobbes, the way we are born conditions natural distrust which makes discipline necessary at the foundation of human society. Does this mean that if we were oviparous mammals that this natural fear could not have arisen? Are twin brothers a factual contradiction of Hobbes’ theory? If these hypotheses seem absurd, they’re absurd for the same reasons as the liberal postulate: that is, it commits the fallacy of appealing to a totally fantasized nature (to which we’ll return in part IV-B). Refusing the Aristotelian conception of human nature[27] but also ignoring our psychic and biological make-up, Hobbes largely paves the way for political economy to extol the virtues of market egoism. But we can’t reproach him for having been ignorant of the existence of mutual aid as a factor in human evolution[28] or that of mirror neurons. On the other hand, to believe in the above myths today is, at best, naive, and, at worst, downright dishonest.

Moving past the State, the naturally egoistic subject had to be transferred to the economic realm in order to provide a theoretical foundation for the novel Liberal Market. Bernard Mandeville (1670-1733) was the precursor to this market egoism and a major influence on Adam Smith. Known for his Fable ofthe Bees which he used to formulate his moral-economic doctrine, Mandeville asserted that private vices make public virtues. In short, if thievery gives work to the locksmith, if gluttony stimulates trade, and if vices of all kinds allow for better access to luxury for a mass of bees, then choosing honesty and simplicity would lead the hive to poverty and death. Take a look at the moral of this fable:

when it’s by justice lopped and bound;

nay, where the people would be great,

as necessary to the state,

as hunger is to make them eat.

Bare virtue can’t make nations live

in splendour; they, that would revive

a golden age, must be as free,

for acorns, as for honesty.[29]

For Mandeville, the anti-social has market value that makes it intrinsically superior to the existence of healthy community. It’s hardly surprising, then, that the major economists who followed such as Adam Smith and David Hume renewed their promises of happiness and peace through trade. And it has to be said that this view prevailed for centuries.[30] This philosophical filth—that the worst of men would benefit society best—could not go on for long without running up against its own contradiction. Faced with the triumph of capitalism, the State itself had to bow down. Marx emphasized this when he wrote about the revolutionary role of the bourgeoisie:

Only under the dominance of Christianity, which makes all national, natural, moral, and theoretical conditions extrinsic to man, could civil society [bourgeois society in the original text] separate itself completely from the life of the state, sever all the species-ties of man, put egoism and selfish need in the place of these species- ties, and dissolve the human world into a world of atomistic individuals who are inimically opposed to one another.[31]

To partly conclude, we will summarize our point: the forced integration of the individual and the community into the State has forced their disintegration through the stimulation ofegoism. But in overestimating the value (market) exchange as a palliative to war proper—a mistake often made in anthropology—room was left for war of ego against ego. By means of a negative mythology as appealing as a curse, liberalism crafted the breed of men it needed to legitimize its reign. This new base was the ideal breeding ground for deadly technological development. For, in order to tear the Earth to shreds, human beings had to be transformed into calculating, selfish machines.[32]

III - An Axiom to Justfy the Obsolescence of Man in the Face of Technology

Placed first in the cold hands of the State, then orphaned, and then gathered up by the economy and driven to selfishness, to what saint could humans now vow? To the one whose forms have made the Earth a stranger to us: to the fire that fell upon the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; to the sheet of glass and steel that haunts our pockets; to those night lights that mask the twinkling of the stars; to those towers that have replaced the trees; to those gray, smoking roads; to the clouds of its power plants. If our sketch is too subtle, it it technology that we are talking about. That “ghost” that haunts our every moment, and whose incessant solicitations have cause to lose a significant part of our humanity:

Nothing alienates us from ourselves and the world more disastrously than to spend our lives, now almost constantly, in the company of these falsely intimate beings, these phantom slaves whom we bring into our living room with a hand numbed by sleep - for the alternation of sleep and wakefulness has given way to the alternation of sleep and radio - to listen to the morning broadcasts during which, first fragments of the world we encounter, they talk to us, look at us, sing to us, encourage us, console us and, by relaxing or stimulating us, set the tone for a day that won't be our own. Nothing makes self-alienation more definitive than continuing the day under the aegis of these apparent friends: for afterwards, even if the opportunity arises to enter into a relationship with real people, we prefer to remain in the company of our portable chums, our portable buddies, since we no longer feel them as ersatz men but as our real friends.[33]

Faced with the technological ersatz, what might our future hold? Anders asks himself and us:

Haven't we already reached a state where we are no longer "ourselves" at all, but merely beings daily force-fed ersatz? Can we strip the already stripped? Can we strip the already naked? Can we still alienate mass man from himself? Is alienation still a process, or has it already become an accomplished fact?[34]

What is the human race when caught in the net of the Technological System? An imperfect being perpetually confronted with a destroyed and artificialized world filled with “manufactured” objects and feeling inferior to them. Why push the development of artificial “intelligence”, why fall in love with transhumanism, why deny our own naturalness if not to quickly evacuate this suffocating, asphyxiating feeling of inferiority to the machine and incompatibility with such a negative human nature? This is how Anders defines “Promethean shame”:

If he wants to make himself, it's not because he can't stand anything he hasn't made himself, but because he refuses to be something that hasn't been made; it's not because he resents having been made by others (God, deities, Nature), but because he isn't made at all and, not having been made, is thereby inferior to his products.[35]

However, we do not agree with Anders when he wrote that “the possibility of our definitive destruction constitutes the definitive destruction of our possibilities.”[36] He would return to this point some twenty years later, though this time explicitly calling on human beings to enter a state of self-defence in the face of omnipresent threat of nuclear death.[37]

By dint of internalizing that man was a wolf to man, all attempts to resist technological “progress” were discouraged. How can we resist such a force when we’re told all day every day that “we” are responsible for climate change, that “we” are destroying the planet, and so on? We do nothing to help ourselves or restore dignity to a self-doubting humanity by accepting fault instead of those who profit with impunity from the ravaging of the Earth. Those responsible are clearly identifiable: scientists, engineers, industrialists, the institutions and organizations that fund them, and so on. So, rather than acquiescing the consequences of what is “our” fault, it’s time to explicitly name those whose power derives from the rape of the living.

Before we present a viable response to the problem raised by Hobbes’ commonplace, we will take a short detour.

IV - Corrections on War and Human Nature

War and human nature are the two themes underpining Hobbes’ conception of the Wolf-Man. Studying them will reveal what is lacking so often and so much in the usual reflections about this peculiar subject.

IV: A - Correction on War

We have already seen that far from annihilating the phenomenon of war— including civil war—the unfolding of the liberal plan has, on the contrary, been accompanied by some of the most horrific undertakings known to man. There’s no need to list them all here, but let’s bet that the children on the 20th century had plenty of reasons to believe in the truth of a Wolf-Man. The camps, the nuclear bombs, the Stalinist terror; there is no end in sight. They had been promised peace and luxury, but then the storms of atoms and steel came crashing down on them. Thoroughly conditioned by liberal doctrine, why should or how could they have been led to believe in anything else?

What they may not have known is that even the most noble of social plans never come to fruition as Theodore Kaczynski reminds us:

Unfortunately, however, not everyone does know that the development of societies can never be subject to rational human control; and even many who would agree with that proposition as an abstract principle fail to apply the principle in concrete cases. Again and again we find seemingly intelligent people proposing elaborate schemes for solving society’s problems, completely oblivious to the fact that such schemes never, never, never are carried out successfully. In a particularly fuddled excursion into fantasy written several decades ago, the noted technology critic Ivan Illich asserted that “society must be reconstructed to enlarge the contribution of autonomous individuals and primary groups to the total effectiveness of a new system of production designed to satisfy the human needs which it also determines,” and that a “convivial society should be designed to allow all its members the most autonomous action by means of tools least controlled by others” — as if a society could be consciously and rationally “reconstructed” or “designed.”[38]

To understand the essence of war better, it is a good idea to take a closer look at what war meant to primitive peoples. As Hobbes based his thesis on a hypothetical state of nature—on the savage state of mankind—it is perfectly justifiable to respond to him on the same ground.

First of all, let’s remember that, as far as primitive peoples are concerned, the word “war” is more a linguistic convenience than a lived reality. This is simply because they fail to match the sheer scale and atrocity of modern wars. It’s hard to see war as anything more than a punitive expedition led by a handful of warriors (not soliders[39]) armed with bows and arrows. As Kaczynski reminds us:

It is important, too, to realize that deadly violence among primitives is not even remotely comparable to modern warfare. When primitives fight, two little bands of men shoot arrows or swing war-clubs at one another because they want to fight; or because they are defending themselves, their families, or their territory. In the modern world soldiers fight because they are forced to do so, or, at best, because they have been brainwashed into believing in some kook ideology such as that of Nazism, socialism, or what American politicians choose to call "freedom." In any case the modern soldier is merely a pawn, a dupe who dies not for his family or his tribe but for the politicians who exploit him. If he's unlucky, maybe he does not die but comes home horribly crippled in a way that would never result from an arrow - or a spear - wound. Meanwhile, thousands of non-combatants are killed or mutilated. The environment is ravaged, not only in the war zone, but also back home, due to the accelerated consumption of natural resources needed to feed the war machine. In comparison, the violence of primitive man is relatively innocuous.[40]

For Pierre Clastres, three hypotheses concerning the origin of war in primitive societies must be ruled out. In a convincing demonstration (of which only the conclusions will be presented here), he asserts that war is due to:

- nether the inherent warlike appetite of the species (a false biological justification);

- nor the scarcity of resources (an erroneous economic justification since primitive societies have been described as societies of abundance, even if this argument could falsely lead us to believe that primitive peoples do not devote the majority of their time to meeting their basic needs);

- nor is it the result of a failed exchange between groups (this is Lévi-Strauss’ position, according to which war signals the impossibility of exchange, with each group taking care not to depend on others to ensure its survival).

For Clastres, war in primitive society is a fact of culture and not of nature. This has obvious implications for Hobbes’ proposition. War in such societies has a political character. Here’s an extract from Clastres’ thesis on the reasons for primitive warfare[41]:

War as the external policy of primitive society relates to its internal policy, to what we might call the intransigent conservatism of this society, expressed in the incessant reference to the traditional system of norms, to the ancestral Law that must always be respected, that cannot be altered by any change. What does primitive society seek to preserve through its conservatism? It seeks to preserve its being. But what is this being? It is an undivided being, the social body is homogeneous, the community is a We. Primitive conservatism therefore seeks to prevent innovation in society; it wants respect for the Law to ensure the maintenance of indivision; it seeks to prevent the appearance of division in society. In economic terms (the impossibility of accumulating wealth) and in terms of power relations (the chief is there not to command), this is the internal policy of primitive society: to preserve itself as an undivided We, as a single totality. [...] In other words, the permanent state of war and periodically effective war appear to be the main means used by primitive society to prevent social change. (p. 202-203)

"Social division, the emergence of the State, is the death of primitive society." (p. 205)

War in primitive societies cannot be thought of in moral terms; the question of right and wrong is irrelevant. Bereft of moral connotation, the aim is to ensure the continuity of an autonomous existence for the group devoid of the internal divisions that usually lead to the construction of a social hierarchy:

Thus, while social stratification was absent or slight in many or most nomadic hunting-and-gathering societies, the sweeping assumption that all hierarchy was absent in all such societies is not true.[42]

With this clarification in mind, it bears repeating that primitive and modern warfare are absolutely different. On the one hand, primitive warfare, very limited in its duration and its effects, aims to defend against any unification and establishment of hierarchy; on the other hand, modern warfare is waged between entities that have already completed this process of unification and hierarchization (i.e. States). Mass eradication in the name of unification is certainly the great novelty of modern warfare, and this was only feasible because of the technological advances resultant from the breakdown of traditional communities, the destruction of their natural environments, and the condemnation of the bulk of mankind to a life of slavery in the name of imagined security and superficial comforts.

IV: B - Correction on Human Nature

The work of Pierre Clastres sheds a singular light on this subject. Throughout his all-too-short career, Clastres studied the culture of primitive peoples. To speak of culture among primitive peoples means, consequently, that classifying them as in a “state of nature”—as Hobbes and so many others have—is a mistake: ifprimitive peoples live in a state ofculture as opposed to a state ofnature, then all reasoning based on assuming the latter is in error. By claiming that man is a wolf “by nature” and simultaneously denying or ignoring the cultural quality of primitive societies as a basis for his assertion, Hobbes and his epigones are mistaken. Drawing the conclusion that man if a wolf by nature solely from the observation of a society living in a state of culture—not of nature—could only lead to error.

The question of man’s natural goodness or badness only serves to stimulate endless debate: if you tell me he’s good, I’ll prove you wrong, and vice versa ad infinitum. It’s a trap that only raises questions without ever answering any. If we accept after Darwin and Kropotkin that the struggle for survival finds its perfect analog in mutual aid, then neither the noble savage nor the Wolf-Man can provide satisfactory answers. The human core is undoubtedly complex, and within it exists all kinds of contradictions: joy and fear; love and anger; life and death.

The Aristotelian conception of man as a political animal (see note 6) at least has the advantage of engaging the question on philosophical, social, and biological levels. Life in a group corresponds to a human psychological need, and our need for otherness to characterize us as human beings has nothing to do with morality.

In short, the human nature that our Hobbesian phrase purports to uncover is nothing but a big bad wolf designed to frighten us and to justify out collective enslavement to the State, the Market, and, ultimately, Technology. To go further, it’s best to set aside the polemical and incapacitating notion of “human nature”[43] and to focus instead on human needs which are very real but denied by the technological system.

V - Human Needs Rather Than Human Nature: the Nature of Our Freedom

Let’s not forget that the continuous and deadly development of technology has only been possible by presenting itself as condicio sine qua non. Thus, the symbol of our times is not the James-Webb telescope but the Foxconn factories[44] in which hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants work and die to produce technological devices, whose raw materials were acquired through the rape of the Earth, forced labor and death of hundreds of thousands of other slaves to extract, and which, once transformed, will end up in the hands of billions of slaves in order to soften their servitude.

But it is precisely in the dissatisfaction and peril generated by the technological system that the purest element of our condition is revealed: the need to live our lives autonomously. From ISAIF:

44. But for most people it is through the power process — having a goal, making an autonomous effort, and attaining the goal — that self-esteem, self-confidence and a sense of power are acquired. When one does not have adequate opportunity to go through the power process the consequences are (depending on the individual and on the way the power process is disrupted) boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behavior, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc.

75. In primitive societies life is a succession of stages. The needs and purposes of one stage having been fulfilled, there is no particular reluctance about passing on to the next stage. A young man goes through the power process by becoming a hunter, hunting not for sport or for fulfillment but to get meat that is necessary for food. (In young women the process is more complex, with greater emphasis on social power; we won’t discuss that here.) This phase having been successfully passed through, the young man has no reluctance about settling down to the responsibilities of raising a family. (In contrast, some modern people indefinitely postpone having children because they are too busy seeking some kind of “fulfillment.” We suggest that the fulfillment they need is adequate experience of the power process — with real goals instead of the artificial goals of surrogate activities.) Again, having successfully raised his children, going through the power process by providing them with the physical necessities, the primitive man feels that his work is done and he is prepared to accept old age (if he survives that long) and death. Many modern people, on the other hand, are disturbed by the prospect of physical deterioration and death, as is shown by the amount of effort they expend in trying to maintain their physical condition, appearance and health. We argue that this is due to unfulfillment resulting from the fact that they have never put their physical powers to any practical use, have never gone through the power process using their bodies in a serious way. It is not the primitive man, who has used his body daily for practical purposes, who fears the deterioration of age, but the modern man, who has never had a practical use for his body beyond walking from his car to his house. It is the man whose need for the power process has been satisfied during his life who is best prepared to accept the end of that life.[45]

The only way to achieve our power process is to act against the technological system and to fight for its extinction without devastating everything in its fall. Our aim is not to plan a future society and take control of the State to achieve it—this has never worked. Our positive ideal is one of nature regenerated by the dismantling of the technological system and of life made possible once again. It is because we want to remain human in a world conducive to the flourishing of life that we see no other way than the anti-tech revolution.

Conclusion

In closing, it would be best to return to where this paper began. Thomas Hobbes, exiled, horrified by civil war, believing he could change the world for the better, asserted that “man is a wolf to man.” Unsurprisingly, this phrase is a truncated borrowing: it was, in fact, borrowed from Plautus, a Latin comic author of the 2nd century BC. Hobbes should have read it more than once because for Plautus: “Man is a wolf to man, when you don’t know him.”[46]

A Reaction to Kaczynski

Darrell Bolin

tldr;

Because of Kaczynski’s actions he became the symbolic leader for anti-tech ideas within mass culture. While he was alive, this inhibited the formation of an anti-tech movement because cultural conditions influence organizational conditions and the cultural burden of Kaczynski was (and still is) too high for meaningful action to spring up around him. Now that he is dead, there is an opportunity for collective action to the degree that members of the public can sublimate the various aspects of their idea of Kaczynski according to strategic considerations. In other words, meaningful action against the technological system becomes increasingly possible the more people manage to get over TK and it will become increasingly easy for people to get over TK the longer he is dead.

Overview

We live in a decidedly post-Kaczynski reality—or should, at least. The reaction to this news has been somewhere between apathetic, nonexistent, and trivializing. This applies to both the general public and our vague anti-tech network. In our case, this is unfortunate because we miss an opportunity. That opportunity is a cultural and developmental one. Consider: society’s reaction to TK’s actions is what introduced anti-tech thinking to public consciousness and mass culture, thereby causing a development in mass culture which in turn allowed for the ideas to reach some members of the mass—us. The cultural development during his time was awareness; the possible one of our time is collective action. We will look at the cultural interaction between Kaczynski and Industrial Society to explain the opportunity.

Industrial Society’s Reaction

Begin with one of the first criticisms (read: copes) that people employ in the face of Kaczynski’s ideas (at least as they were laid out in ISAIF), assuming that they have managed to get past the author himself. This is that he was unoriginal, specifically in regards to criticizing technology. Let’s grant that Kaczynski did not exist in a vacuum and that he was exposed to various intellectual influences over his life, including some then-existing criticisms of technology. A question, then, is why no anti-tech movement developed around the various thinkers that TK supposedly plagiarized. More importantly, if originality is truly at stake, why hasn’t any purely anti-tech movement ever existed in history? Surely if his ideas are or were so widespread as to be plagiarizable, there would have been more than just Kaczynski trying to bring it to the public’s attention through bombs.

The most reasonable response is that, on a mass cultural level, his ideas were original, or novel, or just plain different. At minimum, combining technological criticism with revolutionary theory was an original contribution. Who had heard of such a thing before? One of the only other cultural artifacts that even comes close is the Luddites. But they, of course, did not advocate for the removal of technological infrastructure as such, only their immediate technological replacements.

Anyhow, let’s just assume that Kaczynski’s “anti-tech” was in some way new to the public. What happens when a person (i.e. the massified human) receives novel information? Depending on the presentation, content, and the interest of the parties, they usually react in some fashion. TK’s presentation—anonymous publication in the Washington Post by ultimatum—forced the public to be interested in content they hitherto had no interest in hearing.

The public’s reaction to Kaczynski was natural. Being shocked, appalled, traumatized by bombs and the damage done by them to humans or other living things is intuitive. No one is instinctually equipped to process bombs; no one should be building bombs; no one should be mailing bombs; no one should be being blown up by bombs; no one should learn about mail bombings through electronic media; etc. Yet it must be said that one should not be in an environment where building bombs is even a material possibility, let alone being in an environment where building bombs is even an idea that can even cross one’s mind and become part of their solution to a problem.

The specific historical reaction employed was primarily denial through character assassination. This doesn’t necessarily imply specific intent on anyone’s part: it was simply a matter of shooting the messenger. It was natural (and right) that Kaczynski was “shot” in this sense as it is hoped that some people retain some natural aversion to bombing other lifeforms. While it’s easy to imagine and even likely that some of those with a vested interest in this System were incentivized to fan this primal reaction as a means of further suppressing the associated ideas, there is also no need to be overly conspiratorial: it is easy enough to just accept that the population of the time had every natural right and reason to deny, negate, or otherwise just not to listen to Kaczynski on account of his actions.

Since Kaczynski was messenger and his message was original and his own, ending Kaczynski meant ending his message—at least for a time. This was because TK was culturally the only representative symbol for his ideas (i.e. anti-tech ideas); he was functionally identical to those ideas as far as the average person could tell. Of course, this is all happening on the cultural level: a minuscule proportion of the living world population has ever actually directly humanly interacted with Kaczynski, yet some of us still think we know something about him. What do we know? For most of us, technologically mediated audio and visual information that has the name “Kaczynski” attached to it. This phantom is the symbol of Kaczynski.

Given the nature of our mass society, the amount of information being both processed and presented by it, and the inherent limits of human cognition, it is easier for symbolic representations to enter culture than the complete set of facts that they represent. Thus, it was easier, for example, for sketches of Kaczynski to become memes spreadable around an atomized population than it was for, say, the entire manifesto or Kaczynski’s entire life and intellectual history.