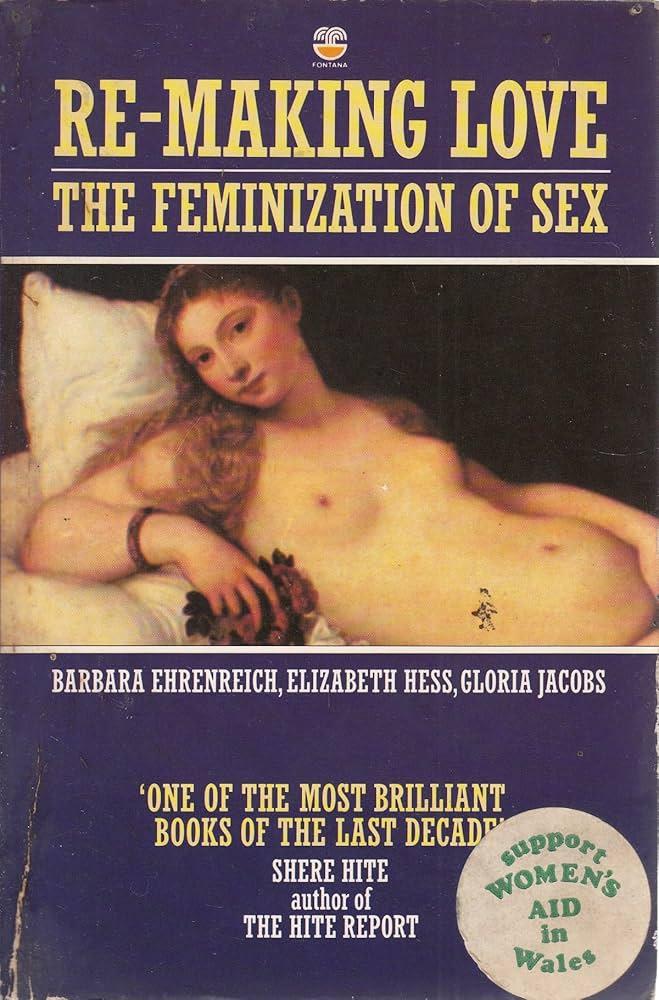

Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess & Gloria Jacobs

Re-Making Love: The Feminization of Sex

1. Beatlemania Girls Just Want to Have Fun

The Economics of Mass Hysteria

The Erotics of the Star-fan Relationship

2. Up from the Valley of the Dolls: The Origins of the Sexual Revolution

Masters & Johnson and the New Sexual Materialism

Feminism and Sexual Revolution

3. The Battle for Orgasm Equity: The Heterosexual Crisis of the Seventies

Sexual Fantasies: The Menu Expands

4. The Lust Frontier: From Tuppenvare to Sadomasochism

5. Fundamentalist Sex: Hitting Below the Bible Belt

6. The Politics of Promiscuity: The Rise of the Sexual Counterrevolution

[Front Matter]

[Synopsis]

The fashionable complaint of the early eighties was that the sexual revolution was a failure, and that sex itself was dead. Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess, and Gloria Jacobs argue that there has been a genuine revolution in sexual attitudes and that it was initiated by women—not men. REMAKING LOVE shows how the sexual revolution has transformed not only our behavior, but our deepest understanding of sex and its meaning in our lives.

This book takes a look at how this once anonymous women s sexual revolution has transformed sexual practices in bedrooms across the country—even in unexpected places like Christian fundamentalist homes or the back rooms of S/M bars.

Re-making Love opens with an enlightening analysis of the repressive sexual mores of the fifties that led to widespread sexual dissatisfaction—and hence, the outburst of sexual experimentation we have all witnessed. Drawing on personal interviews and a wide variety of sources from popular culture, the book goes on to map the current sexual landscape and introduce the people who have shaped it—sexual mavericks, conservatives, “experts,” and the ordinary women seeking to integrate the new sexuality with their growing sense of autonomy as women.

In this original, provocative, and at times startling book, a part of our recent history that is all too often obscured by myth and prejudice has been restored to us. REMAKING LOVE demonstrates how the sexual upheaval of the last two decades has been a primary force in shaping the lives of the baby boom generation and those who followed them. The book tells the story of this controversial sexual revolution: how it came to be, where it has taken us, and where it is going.

Barbara Ehrenreichs most recent book is The Hearts of Men. Her articles have appeared in many publications, including the New York Times, Vogue, The Atlantic, and The Wall Street Journal. Elizabeth Hess is a free-lance writer who has written for the Washington Post, The Village Voice, Art in America, and Ms., among other publications. Gloria Jacobs is an editor at Ms. Her articles have appeared in such publications as Mother Jones, Womens World, and the Daily News.

JACKET COLLAGE BY JOAN HALL

JACKET TYPOGRAPHY BY BILL NAEGELS

Printed in the U.S.A.

Also by Barbara Ehrenreich

The Hearts of Men: American Dreams and the

Flight from Commitment

By Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English

For Her Own Good: 150 Years of Advice to Women

Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers

Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness

[Title Page]

RE-MAKING

LOVE

The Feminization of Sex

Barbara Ehrenreich,

Elizabeth Hess,

Gloria Jacobs

ANCHOR PRESS/DOUBLEDAY

GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK

1986

[Copyright]

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ehrenreich, Barbara.

Re-making love.

Bibliography: p. 217.

Includes index.

1. Women—United States—Sexual behavior.

2. Sex customs—United States. 3. Feminism—United States. 4. Sex (Psychology) I. Hess, Elizabeth.

II. Jacobs, Gloria. III. Title.

HQ29.E35 1986 306.7’088042 86–2074 \

ISBN 0-385-18498-0

Copyright © 1986 by Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess, Gloria Jacobs

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[Dedication]

To our children—Alexa, Gideon, Kate,

Rosa, and Benjy—

and to the memory of Betty Ann Colhoun.

Contents

Introduction

1. Beatlemania: Girls Just Want to Have Fun

2. Up from the Valley of the Dolls: The Origins of the Sexual Revolution

3 The Battle for Orgasm Equity: The Heterosexual Crisis of the Seventies

4 The Lust Frontier: From Tupperware to Sadomasochism

5 Fundamentalist Sex: Hitting Below the Bible Belt

6 The Politics of Promiscuity: The Rise of the Sexual Counterrevolution

7. Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

This book was written during a time of exciting new debate on issues of sexuality; the debate has brought argument and fresh energy to a discussion that had grown moribund. All of this new work, even when not cited directly in our book, has challenged us and helped to clarify our thinking. Writers such as Dennis Altman, Kate Ellis, Jeffrey Escoffier, Lynne Segal, Christine Stansell, Ann Snitow, Sharon Thompson, Carol Vance, and Ellen Willis have expanded the parameters of the debate and reasserted the importance of sexual liberation within the broader context of women’s liberation.

The original idea for this book developed out of an article we wrote for Ms. in 1980, and we would like to thank our many friends there for their encouragement and advice.

The numerous women and men who spoke to us about the intimate details of their lives must feel that their reputations are in our hands. We’d like to thank them for their time and their trust in us. In return we have altered their names and some background information to protect their anonymity.

We would like also to thank all the people who offered varied kinds of help, ranging from hours of discussion and shared reading material to typing assistance, computer hookups or a free room to work in. These include Dick Colhoun, Marilyn Gaizband, Lindy Hess, Deborah Huntington, Karen Judd, Mimi Keck, Ellen Keniston, Nancy Lewis Peck, Virginia Reath, Ruth Russell, Brenda Steinberg, Fannie Steinberg, and Stephanie Urdang. John Russell, Harriet Bernstein, and Susan Butler were our extremely able research assistants. In addition, Barbara Ehrenreich thanks the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C., and the New York Institute for Humanities for providing good fellowship as well as more concrete forms of support.

To our agent, Charlotte Sheedy, and our editor, Loretta Barrett: Both wondered what they were getting into when they took on three authors to do one book. Both knew when to stand back and let us find our way and when to step in with advice and encouragement. We are deeply grateful to each for their deft touch and supportive friendship.

Finally we want to thank Peter Biskind, Jon Steinberg, and Gary Stevenson, who provided sympathetic companionship throughout the many versions of this book. Yes, they changed the diapers, made the dinners, and read and commented on various drafts. Most important, they never considered such support beyond the call of duty.

Re-making Love

Introduction

For most Americans, the “sexual revolution” is what Gay Tálese found when he set out on his quest to see what middle-aged, middle-class men had been missing all these years: wife-swapping clubs, massage parlors, Hugh Hefner’s harem of bunnies, Screw. It was a sexual marketplace that dominated and marginalized women; and if this was all there was to the sexual revolution, then its critics have been right to see it as little more than a male fling and a setback for women. The dark side of the gaudy new industry of pornography and commoditized sex for men has been, as feminists have noted, the exploitation of women as “sex workers” (models, masseuses, etc.) and the deepening objectification of all women as potential instruments of male pleasure.

But the sexual revolution that Tálese found is only half the story, or less. There has been another, hidden sexual revolution that the male commentators and even the feminist critics have for the most part failed to acknowledge: This is a women’s sexual revolution, and the changes it has brought about in our lives and expectations go far deeper than anything in the superficial spectacle of sexuality we have come to identify as “the” sexual revolution.

In fact, if either sex has gone through a change in sexual attitudes and behavior that deserves to be called revolutionary, it is women, and not men at all. This fact should be widely known, because it leaps out from all the polls and surveys that count for data in these matters. Put briefly, men changed their sexual behavior very little in the decades from the fifties to the eighties. They “fooled around,” got married, and often fooled around some more, much as their fathers and perhaps their grandfathers had before them. Women, however, have gone from a pattern of virginity before marriage and monogamy thereafter to a pattern that much more resembles men’s: Between the mid-sixties and the midseventies, the number of women reporting premarital sexual experience went from a daring minority to a respectable majority; and the proportion of married women reporting active sex lives “on the side” is, in some estimates, close to half. The symbolic importance of female chastity is rapidly disappearing.

It is not only that women came to have more sex, and with a greater variety of partners, but they were having it on their own terms, and enjoying it as enthusiastically as men are said to. As recently as the 1950s, America’s greatest acknowledged sexual problem—or as we would now say, “dysfunction”—was female frigidity. Some experts estimated that over half of American women were completely nonorgasmic, or “frigid,” and volumes of speculation were devoted to the sources of this unfortunate condition. But in 1975, a Redbook survey found that 81 percent of the 100,000 female respondents were orgasmic “all or most of the time.” When a Cosmopolitan survey resulted in similar results five years later, writer Linda Wolfe characterized American women, at least those who respond to magazine surveys, as “the most sexually experienced and experimental group of women in Western history.”

The statistics on women’s sexual revolution may be surprising and unfamiliar, but other evidence of it has become as much a part of the American cultural landscape as shopping malls and video-rental shops. We no longer, for example, expect books offering advice on sex to be the remote, authoritarian works of male physicians. More likely today they are written by women, and based on the experiences of women. Nor do we expect women’s sexuality to be simply passive and decorative in its public manifestations. Even in the staid and married suburbs, women flock to male strip joints, provide a market for the new, “couple-oriented” pornographic videotapes, and organize Tupperware-style “home parties” where the offerings are sexual paraphernalia rather than plastic containers. And in media fiction, we no longer find the images of women divided between teasing virgins and sexless matrons: Whether on the prime-time soaps or in the latest teen film, women are likely to be portrayed as sexually assertive, if not downright predatory.

So it is surprising, even somewhat mysterious, that women’s sexual revolution has been so little heralded, discussed, or even noted. Despite all the evidence as to which sex really changed, the phrase “the sexual revolution” is still more likely to conjure up the image of Hugh Hefner rather than, say, the work of Shere Hite, or to put us in mind of the Times Square smut shops than the expanding sexual marketplace for women only. One could think of the predictable feminist explanations for why women’s sexual revolution, and only women’s, has been so effectively “hidden from history.” This would not be the first time men have claimed innovations that were originally wrought by women. Nor would it be the first time men have evaded a feminine innovation they found vaguely troubling— or perhaps even overtly disturbing.

But feminists, for the most part, have not been eager to claim women’s sexual revolution either. When they have acknowledged the change at all, they have tended to be ambivalent about its meaning for women: To have more sex, even better sex with men may be liberating or it may represent no great gain—especially if the men themselves have evolved so little from the era when their word for sex was “scoring.” But on the whole, feminists, much like everyone else, have been content to let “the” sexual revolution mean men’s sexual revolution—and to concentrate on women’s roles as bystanders or victims, not as instigators.

This book is about women’s sexual revolution—its origins in a culture that was repressive not only to sexuality in all its forms but to women as citizens; its connections, often frayed and tattered, to women’s better known, feminist revolution; its evolution from the optimistic sixties to the much more guarded and conservative eighties. Our focus is on the cultural mainstream— not the avant-garde and not the brave members of sexual minority groups, most prominently gays and lesbians, who did so much to broaden the American concept of sexuality. Rather, we are concerned here with the changes as they occurred in the most obvious places, the most visible parts of American mass culture, where strangely, for all their “obviousness,” they have been most thoroughly ignored.

Our emphasis, too, is on the cultural implications of women’s sexual revolution rather than the raw, demographic indicators of deeper change. It will take another Kinsey to sort through, systematize, and verify the disparate sex surveys of the last two decades. We are less concerned with “how much” than with “what” happened, and—perhaps even more important—how Americans understood and interpreted the change to themselves. Thus, one of our major focuses is on how sex itself changed in the process of women’s sexual revolution. It is not that women simply had more sex than they had had in the past, but they began to transform the notion of heterosexual sex itself: from the irreducible “act” of intercourse to a more open-ended and varied kind of encounter. At the same time, the social meaning of sex changed too: from a condensed drama of female passivity and surrender to an interaction between potentially equal persons.

One of our deepest motivating concerns is the relationship between sexual liberation and the larger goals of women articulated by the feminist movement of the past two decades. Feminist ideas, including lesbian feminist ideas, were centrally important to the emergence of women’s sexual revolution—even as it has been experienced by women who would never call themselves feminists and who have no sympathy for the gay and lesbian movements. Yet the women’s sexual revolution has gone its own way and found itself in settings that are indifferent to feminist concerns and, in some cases, actually hostile to them. The result is, to us, an odd and disturbing separation of goals: Women have won a new range of sexual rights—to pleasure, to fantasy and variety—but we have not yet achieved our full human rights. This disjuncture between feminism and women’s sexual revolution affects both movements, as we shall see, in ways that are strange and even painful to relate.

The roots of women’s sexual revolution lie in a set of circumstances that arose with the waning of the fifties: Middle-class women were beginning to experience the malaise so brilliantly documented by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique, and much of their private dissatisfaction centered on marital sex, which fell short of being a glowing payoff for a life of submersion in domestic detail. At the same time, new opportunities were opening up for women. As jobs for women proliferated, young single women crowded into the major cities, and began to enlarge the gap between girlhood and marriage, filling it with careers, romances, and— what was distinctly new—casual sexual adventures. Even very young women were finding, in the burgeoning teen-centered consumer culture, a space of their own between childhood and womanhood. It was these new “spaces”—a teen culture dominated by the heavy beat of rock ’n’ roll and a singles culture populated by young, urban adults—that incubated woihen’s sexual revolution.

We begin, perhaps surprisingly, with “Beatlemania,” that huge outbreak of teenage female libido that so confounded adults at the time. The experts called it “female hysteria,” but it contained the germs of a more serious rebellion against the rules that defined a teenage girl’s sexuality as something to be bartered for an early engagement ring. Rock ’n’ roll offered a new vision of sexuality (female as well as male) that was distinctly undomesticated; and it offered an unprecedented vision of men, not as beaux or breadwinners but as sex objects for women.

In Chapter 2, we move on to the full-scale beginnings of women’s sexual revolution, as young, single women began to challenge both the practice and the social interpretation of heterosexual sex. Masters and Johnson have received most of the credit for the new understanding of female sexuality that emerged in the 1960s, but they were, in a way, only providing a scientific rationale for a new social reality that women were creating for themselves. In Chapter 3, we follow the subsequent transformation in the way American culture thought of sex: from a two-stage encounter divided into “foreplay” and intercourse to a far more complex and varied set of possibilities. With sex redefined, the sexual relationship began to be reimagined—not as a spontaneous burst of (mostly male) passion but as an arena for negotiation where women were no longer the automatic losers.

Chapter 4 examines the growing sexual marketplace for women, and the way that the consumer culture has served to perpetuate and proselytize for the women’s sexual revolution. Novelty is key to the growth of the sexual marketplace, and it actually encourages practices that were once considered to be marginal and perverted, such as sadomasochism. Nothing could be further from the earlier feminist notions of sexual liberation, yet in one form or another S/M has been assimilated into America’s mainstream sexual culture, and not only in its “hard-core,” male-oriented expressions. Even stranger, perhaps, is the development we trace in Chapter 5, the penetration of women’s sexual revolution into the otherwise closed-minded culture of rightwing Christian fundamentalism. In this culture, an unacknowledged kind of sadomasochism is the rule for male-female relationships, yet some covertly feminist notions of sex itself are gaining ground.

While we were researching and writing this book, a backlash against “the” sexual revolution was growing in volume and intensity. The voices raised to denounce the sexual revolution or declare it dead never specify, of course, whose revolution is in question. But it seems to us that what inflames the new rhetoric of sexual conservatism must be women’s behavior, which has changed, rather than men’s, which has barely changed at all. Two or three years ago, the critics of sexual revolution focused on what they saw as a loss of “romance” and “meaning,” as sex became more casual and less attached to the old consequences—marriage and maternity. Today, arguments for “the death of sex” have gained more force, though not always more scientific credibility, by focusing on the danger of AIDS and other venereal diseases. In Chapter 6, we trace the backlash and show how it represents a revival, not only of repressive notions about sexuality but of traditional, sexist notions of women’s role in society. We will also find that even as the backlash spreads in the media, more women—from blue- and pink-collar workers to executives—are waging the sexual revolution in their own lives.

We ourselves see much to celebrate in women’s sexual revolution but also much to reassess and rethink. To us, the greatest problem with this sexual revolution is not that it took away the meaning of sex; if anything, sex has been overly burdened with oppressive “meanings,” and especially for women. Nor is it even the threat of disease; historically, sex has always carried risks for women, not the least of which is unwanted pregnancy. Rather, the problem is that women’s sexual liberation has become unraveled from the larger theme of women’s liberation. For women, sexual equality with men has become a concrete possibility, while economic and social parity remains elusive. We believe it is this fact, beyond all others, that has shaped the possibilities and politics of women’s sexual liberation.

To follow and understand this sexual revolution, we ask you to set aside, at least temporarily, both feminist and conservative dogmas about what is good and bad or right and wrong when it comes to sex. The suburban woman who gets her thrills from watching male strippers is paying, with her admission price, to invert the usual relationship between men and women, consumer and object. The born-again Christian woman who imagines her sex life as a service to Jesus has gained purchase to yet another realm of erotic possibilities. At a different end of the cultural spectrum, a practitioner of ritualistic sadomasochism confronts social inequality by encapsulating it in a drama of domination and submission. Desire takes strange paths through a landscape of inequality; we need to be able to follow them, at least in spirit, before we judge.

1. Beatlemania Girls Just Want to Have Fun

... witness the birth of eve—she is rising she was sleeping she is fading in a naked field sweating the precious blood of nodding blooms ... in the eye of the arena she bends in half in service—the anarchy that exudes from the pores of her guitar are the cries of the people wailing in the rushes ... a riot of ray/ dios ...

Patti Smith, “Notice,” in Babel

The news footage shows police lines straining against crowds of hundreds of young women. The police look grim; the girls’ faces are twisted with desperation or, in some cases, shining with what seems to be an inner light. The air is dusty from a thousand running and scuffling feet. There are shouted orders to disperse, answered by a rising volume of chants and wild shrieks. The young women surge forth; the police line breaks ...

Looking at the photos or watching the news clips today, anyone would guess that this was the sixties—a demonstration—or maybe the early seventies—the beginning of the women’s liberation movement. Until you look closer and see that the girls are not wearing sixties- issue jeans and T-shirts but bermuda shorts, highnecked, preppie blouses, and disheveled but unmistakably bouffant hairdos. This is not 1968 but 1964, and the girls are chanting, as they surge against the police line, “I love Ringo.”

Yet, if it was not the “movement,” or a clear-cut protest of any kind, Beatlemania was the first mass outburst of the sixties to feature women—in this case girls, who would not reach full adulthood until the seventies and the emergence of a genuinely political movement for women’s liberation. The screaming ten- to fourteen- year-old fans of 1964 did not riot for anything, except the chance to remain in the proximity of their idols and hence to remain screaming. But they did have plenty to riot against, or at least to overcome through the act of rioting: In a highly sexualized society (one sociologist found that the number of explicitly sexual references in the mass media had doubled between 1950 and 1960), teen and preteen girls were expected to be not only “good” and “pure” but to be the enforcers of purity within their teen society—drawing the line for overeager boys and ostracizing girls who failed in this responsibility. To abandon control—to scream, faint, dash about in mobs—was, in form if not in conscious intent, to protest the sexual repressiveness, the rigid double standard of female teen culture. It was the first and most dramatic uprising of women’s sexual revolution.

Beatlemania, in most accounts, stands isolated in history as a mere craze—quirky and hard to explain. There had been hysteria over male stars before, but nothing on this scale. In its peak years—1964 and 1965 —Beatlemania struck with the force, if not the conviction, of a social movement. It began in England with a report that fans had mobbed the popular but not yet immortal group after a concert at the London Palladium on October 13, 1963. Whether there was in fact a mob or merely a scuffle involving no more than eight girls is not clear, but the report acted as a call to mayhem. Eleven days later a huge and excited crowd of girls greeted the Beatles (returning from a Swedish tour) at Heathrow Airport. In early November, 400 Carlisle girls fought the police for four hours while trying to get tickets for a Beatles concert; nine people were hospitalized after the crowd surged forward and broke through shop windows. In London and Birmingham the police could not guarantee the Beatles safe escort through the hordes of fans. In Dublin the police chief judged that the Beatles’ first visit: was “all right until the mania degenerated into barbarism.”{1} And on the eve of the group’s first U.S. tour, Life reported, “A Beatle who ventures out unguarded into the streets runs the very real peril of being dismembered or crushed to death by his fans.”{2} When the Beatles arrived in the United States, which was still ostensibly sobered by the assassination of Pfesi- dent Kennedy two months before, the fans knew what to do. Television had spread the word from England: The approach of the Beatles is a license to riot. At least 4,000 girls (some estimates run as high as 10,000) greeted them at Kennedy Airport, and hundreds more laid siege to the Plaza Hotel, keeping the stars virtual prisoners. A record 73 million Americans watched the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show” on February 9, 1964, the night “when there wasn’t a hubcap stolen anywhere in America.” American Beatlemania soon reached the proportions of religious idolatry. During the Beatles’ twenty-three-city tour that August, local promoters were required to provide a minimum of 100 security guards to hold back the crowds. Some cities tried to ban Beatle-bearing craft from their runways; otherwise it took heavy deployments of local police to protect the Beatles from their fans and the fans from the crush. In one city, someone got hold of the hotel pillowcases that had purportedly been used by the Beatles, cut them into 160,000 tiny squares, mounted them on certificates, and sold them for $1 apiece. The group packed Carnegie Hall, Washington’s Coliseum and, a year later, New York’s 55,600-seat Shea Stadium, and in no setting, at any time, was their music audible above the frenzied screams of the audience. In 1966, just under three years after the start of Beatlemania, the Beatles gave their last concert—the first musical celebrities to be driven from the stage by their own fans.

In its intensity, as well as its scale, Beatlemania surpassed all previous outbreaks of star-centered hysteria. Young women had swooned over Frank Sinatra in the forties and screamed for Elvis Presley in the immediate pre-Beatle years, but the Fab Four inspired an extremity of feeling usually reserved for football games or natural disasters. These baby boomers far outnumbered the generation that, thanks to the censors, had only been able to see Presley’s upper torso on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Seeing (whole) Beatles on Sullivan was exciting, but not enough. Watching the band on television was a thrill—particularly the close-ups—but the real goal was to leave home and meet the Beatles. The appropriate reaction to contact with them—such as occupying the same auditorium or city block—was to sob uncontrollably while screaming, “I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die,” or, more optimistically, the name of a favorite Beatle, until the onset of either unconsciousness or laryngitis. Girls peed in their pants, fainted, or simply collapsed from the emotional strain. When not in the vicinity of the Beatles—and only a small proportion of fans ever got within shrieking distance of their idols— girls exchanged Beatle magazines or cards, and gathered to speculate obsessively on the details and nuances of Beatle life. One woman, who now administers a Washington, D.C.-based public interest group, recalls long discussions with other thirteen-year-olds in Orlando, Maine:

I especially liked talking about the Beatles with other girls. Someone would say, “What do you think Paul had for breakfast?” “Do you think he sleeps with a different girl every night?” Or, “Is John really the leader?” “Is George really more sensitive?” And like that for hours.

This fan reached the zenith of junior high school popularity after becoming the only girl in town to travel to a Beatles’ concert in Boston: “My mother had made a new dress for me to wear [to the concert] and when I got back, the other girls wanted to cut it up and auction off the pieces.”

To adults, Beatlemania was an affliction, an “epidemic,” and the Beatles themselves were only the carriers, or even “foreign germs.” At risk were all ten- to fourteen-year-old girls, or at least all white girls; blacks were disdainful of the Beatles’ initially derivative and unpolished sound. There appeared to be no cure except for age, and the media pundits were fond of reassuring adults that the girls who had screamed for Frank Sinatra had grown up to be responsible, settled housewives. If there was a shortcut to recovery, it certainly wasn’t easy. A group of Los Angeles girls organized a detox effort called “Beatlesaniacs, Ltd.,” offering “group therapy for those living near active chapters, and withdrawal literature for those going it alone at far-flung outposts.” Among the rules for recovery were: “Do not mention the word Beatles (or beetles),” “Do not mention the word England,” “Do not speak with an English accent,” and “Do not speak English.”{3} In other words, Beatlemania was as inevitable as acne and gum-chewing, and adults would just have to weather it out.

But why was it happening? And why in particular to an America that prided itself on its post-McCarthy maturity, its prosperity, and its clear position as the number one world power? True, there were social problems that not even Reader’s Digest could afford to be smug about—racial segregation, for example, and the newly discovered poverty of “the other America.” But these were things that an energetic President could easily handle—or so most people believed at the time—and if “the Negro problem,” as it was called, generated overt unrest, it was seen as having a corrective function and limited duration. Notwithstanding an attempted revival by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, “extremism” was out of style in any area of expression. In colleges, “coolness” implied a detached and rational appreciation of the status quo, and it was de rigueur among all but the avant-garde who joined the Freedom Rides or signed up for the Peace Corps. No one, not even Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse, could imagine a reason for widespread discontent among the middle class or for strivings that could not be satisfied with a department store charge account—much less for “mania.”

In the media, adult experts fairly stumbled over each other to offer the most reassuring explanations. The New York Times Magazine offered a “psychological, anthropological,” half tongue-in-cheek account, titled “Why the Girls Scream, Weep, Flip.” Drawing on the work of the German sociologist Theodor Adorno, Times writer David Dempsey argued that the girls weren’t really out of line at all; they were merely “conforming.” Adorno had diagnosed the 1940s jitterbug fans as “rhythmic obedients,” who were “expressing their desire to obey.” They needed to subsume themselves into the mass, “to become transformed into an insect.” Hence, “jitterbug,” and as Dempsey triumphantly added: “Beatles, too, are a type of bug ... and to ‘beatle,’ as to jitter, is to lose one’s identity in an automatized, insectlike activity, in other words, to obey.” If Beatlemania was more frenzied than the outbursts of obedience inspired by Sinatra or Fabian, it was simply because the music was “more frantic”’ and in sorhe animal way, more compelling. It is generally admitted “that jungle rhythms influence the ‘beat’ of much contemporary dance activity,” he wrote, blithely endorsing the stock racist response to rock ’n’ roll. Atavistic, “aboriginal” instincts impelled the girls to scream, weep, and flip, whether they liked it or not: “It is probably no coincidence that the Beatles, who provoke the most violent response among teen-agers, resemble in manner the witch doctors who put their spells on hundreds of shuffling and stamping natives.”{4}

Not everyone saw the resemblance between Beatle- manic girls and “natives” in a reassuring light however. Variety speculated that Beatlemania might be “a phenomenon closely linked to the current wave of racial rioting.”{5} It was hard to miss the element of defiance in Beatlemania. If Beatlemania was conformity, it was conformity to an imperative that overruled adult mores and even adult laws. In the mass experience of Beatlemania, as for example at a concert or an airport, a girl who might never have contemplated shoplifting could assault a policeman with her fists, squirm under police barricades, and otherwise invite a disorderly conduct charge. Shy, subdued girls could go berserk. “Perky,” ponytailed girls of the type favored by early sixties sitcoms could dissolve in histrionics. In quieter contemplation of their idols, girls could see defiance in the Beatles or project it onto them. Newsweek quoted Pat Hagan, “a pretty, 14-year-old Girl Scout, nurse’s aide, and daughter of a Chicago lawyer ... who previously dug ‘West Side Story,’ Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: They’re tough,’ she said of the Beatles. ‘Tough is like when you don’t conform.... You’re tumultuous when you’re young, and each generation has to have its idols.’ ”{6} America’s favorite sociologist, David Riesman, concurred, describing Beatlemania as “a form of protest against the adult world.”{7}

There was another element of Beatlemania that was hard to miss but not always easy for adults to acknowledge. As any casual student of Freud would have noted, at least part of the fans’ energy was sexual. Freud’s initial breakthrough had been the insight that the epidemic female “hysteria” of the late nineteenth century —which took the form of fits, convulsions, tics, and what we would now call neuroses—was the product of sexual repression. In 1964, though, confronted with massed thousands of “hysterics,” psychologists approached this diagnosis warily. After all, despite everything Freud had had to say about childhood sexuality, most Americans did not like to believe that twelve- year-old girls had any sexual feelings to repress. And no normal girl—or full-grown woman, for that matter— was supposed to have the libidinal voltage required for three hours of screaming, sobbing, incontinent, acute- phase Beatlemania. In an article in Science News Letter titled “Beatles Reaction Puzzles Even Psychologists,” one unidentified psychologist offered a carefully phrased, hygienic explanation: Adolescents are “going through a strenuous period of emotional and physical growth,” which leads to a “need for expressiveness, especially in girls.” Boys have sports as an outlet; girls have only the screaming and swooning afforded by Beatlemania, which could be seen as “a release of sexual energy.”{8}

For the girls who participated in Beatlemania, sex was an obvious part of the excitement. One of the most common responses to reporters’ queries on the sources of Beatlemania was, “Because they’re sexy.” And this explanation was in itself a small act of defiance. It was rebellious (especially for the very young fans) to day claim to sexual feelings. It was even more rebellious to lay claim to the active, desiring side of a sexual attraction: The Beatles were the objects; the girls were their pursuers. The Beatles were sexy; the girls were the ones who perceived them as sexy and acknowledged the force of an ungovernable, if somewhat disembodied, lust. To assert an active, powerful sexuality by the tens of thousands and to do so in a way calculated to attract maximum attention was more than rebellious. It was, in its own unformulated, dizzy way, revolutionary.

Sex and the Teenage Girl

In the years and months immediately preceding U.S. Beatlemania, the girls who were to initiate a sexual revolution looked, from a critical adult vantage point, like sleepwalkers on a perpetual shopping trip. Betty Friedan noted in her 1963 classic, The Feminine Mystique, “a new vacant sleepwalking, playing-a-part quality of youngsters who do what they are supposed to do, what the other kids do, but do not seem to feel alive or real in doing it.”{9} But for girls, conformity meant more than surrendering, comatose, to the banal drift of junior high or high school life. To be popular with boys and girls—to be universally attractive and still have an unblemished “reputation”—a girl had to be crafty, cool, and careful. The payoff for all this effort was to end up exactly like Mom—as a housewife.

In October 1963, the month Beatlemania first broke out in England and three months before it arrived in America, Life presented a troubling picture of teenage girl culture. The focus was Jill Dinwiddie, seventeen, popular, “healthy, athletic, getting A grades,” to all appearances wealthy, and at the same time, strangely vacant. The pictures of this teenage paragon and her friends would have done justice to John Lennon’s first take on American youth:

When we got here you were all walkin’ around in fuckin’ Bermuda shorts with Boston crew- cuts and stuff on your teeth.... The chicks looked like 1940’s horses. There was no conception of dress or any of that jazz. We just thought what an ugly race, what an ugly race.{10}

Jill herself, the “queen bee of the high school,” is strikingly sexless: short hair in a tightly controlled style (the kind achieved with flat metal clips), button-down shirts done up to the neck, shapeless skirts with matching cardigans, and a stance that evokes the intense posture- consciousness of prefeminist girls’ phys ed. Her philosophy is no less engaging: “We have to be like everybody else to be accepted. Aren’t most adults that way? We learn in high school to stay in the middle.”{11}

“The middle,” for girls coming of age in the early sixties, was a narrow and carefully defined terrain. The omnipresent David Riesman, whom Life called in to comment on Jill and her crowd, observed, “Given a standard definition of what is feminine and successful, they must conform to it. The range is narrow, the models they may follow few.” The goal, which Riesman didn’t need to spell out, was marriage and motherhood, and the route to it led along a straight and narrow path between the twin dangers of being “cheap” or being too puritanical, and hence unpopular. A girl had to learn to offer enough, sexually, to get dates, and at the same time to withhold enough to maintain a boy’s interest through the long preliminaries from dating and going steady to engagement and finally marriage. None of this was easy, and for girls like Jill the pedagogical burden of high school was a four-year lesson in how to use sex instrumentally: doling out just enough to be popular with boys and never enough to lose the esteem of the “right kind of kids.” Commenting on Life’s story on Jill, a University of California sociologist observed:

It seems that half the time of our adolescent girls is spent trying to meet their new responsibilities to be sexy, glamorous and attractive, while the other half is spent meeting their old responsibility to be virtuous by holding off the advances which testify to their success.

Advice books to teenagers fussed anxiously over the question of “where to draw the fine,” as did most teenage girls themselves. Officially everyone—girls and advice-givers—agreed that the line fell short of intercourse, though by the sixties even this venerable prohibition required some sort of justification, and the advice-givers strained to impress upon their young readers the calamitous results of premarital sex. First there was the obvious danger of pregnancy, an apparently inescapable danger since no book addressed to teens dared offer birth control information. Even worse, some writers suggested, were the psychological effects of intercourse: It would destroy a budding relationship and possibly poison any future marriage. According to a contemporary textbook titled, Adolescent Development and Adjustment, intercourse often caused a man to lose interest (“He may come to believe she is totally promiscuous”), while it was likely to reduce a woman to slavish dependence (“Sometimes a woman focuses her life around the man with whom she first has intercourse”).{12} The girl who survived premarital intercourse and went on to marry someone else would find marriage clouded with awkwardness and distrust. Dr. Arthur Cain warned in Young People and Sex that the husband of a sexually experienced woman might be consumed with worry about whether his performance matched that of her previous partners. “To make matters worse,” he wrote, “it may be that one’s sex partner is not as exciting and satisfying as one’s previous illicit lover.”{13} In short, the price of premarital experience was likely to be postnuptial disappointment. And, since marriage was a girl’s peak achievement, an anticlimactic wedding night would be a lasting source of grief.

Intercourse was obviously out of the question, so young girls faced the still familiar problem of where to draw the line on a scale of lesser sexual acts, including (in descending order of niceness): kissing, necking, and petting, this last being divided into “light” (through clothes and/or above the waist) and “heavy” (with clothes undone and/or below the waist). Here the experts were no longer unanimous. Pat Boone, already a spokesman for the Christian right, drew the line at kissing in his popular 1958 book, ’Twixt Twelve *and Twenty. No prude, he announced that “kissing is here to stay and I’m glad of it!” But, he warned, “Kissing is not a game. Believe me! ... Kissing for fun is like playing with a beautiful candle in a roomful of dynamite!”{14} (The explosive consequences might have been guessed from the centerpiece photos showing Pat dining out with his teen bride, Shirley; then, as if moments later, in a maternity ward with her; and, in the next picture, surrounded by “the four little Boones.”) Another pop-singer-turned-adviser, Connie Francis, saw nothing wrong with kissing (unless it begins to “dominate your life”), nor with its extended form, necking, but drew the line at petting:

Necking and petting—let’s get this straight— are two different things. Petting, according to most definitions, is specifically intended to arouse sexual desires and as far as I’m concerned, petting is out for teenagers.{15}

In practice, most teenagers expected to escalate through the scale of sexual possibilities as a relationship progressed, with the big question being: How much, how soon? In their 1963 critique of American teen culture, Teen-Age Tyranny, Grace and Fred Hechinger bewailed the cold instrumentality that shaped the conventional answers. A girl’s “favors,” they wrote, had become “currency to bargain for desirable dates which, in turn, are legal tender in the exchange of popularity.” For example, in answer to the frequently asked question, “Should I let him kiss me good night on the first date?” they reported that:

A standard caution in teen-age advice literature is that, if the boy “gets” his kiss on the first date, he may assume that many other boys have been just as easily compensated. In other words, the rule book advises mainly that the [girl’s] popularity assets should be protected against deflation.{16}

It went without saying that it was the girl’s responsibility to apply the brakes as a relationship approached the slippery slope leading from kissing toward intercourse. This was not because girls were expected to be immune from temptation. Connie Francis acknowledged that “It’s not easy to be moral, especially where your feelings for a boy are involved. It never is, because you have to fight to keep your normal physical impulses in line.” But it was the girl who had the most to lose, not least of all the respect of the boy she might too generously have indulged. “When she gives in completely to a boy’s advances,” Francis warned, “the element of respect goes right out the window.” Good girls never “gave in,” never abandoned themselves to impulse or emotion, and never, of course, initiated a new escalation on the scale of physical intimacy. In the financial metaphor that dominated teen sex etiquette, good girls “saved themselves” for marriage; bad girls were cheap.

According to a 1962 Gallup Poll commissioned by Ladies’ Home Journal, most young women (at least in the Journal’s relatively affluent sample) enthusiastically accepted the traditional feminine role and the sexual double standard that went with it:

Almost all our young women between 16 and, 21 expect to be married by 22. Most want 4 children, many want ... to work until children come; afterward, a resounding no! They feel a special responsibility for sex because they are women. An 18-year-old student in California said, “The standard for men—sowing wild oats—results in sown oats. And where does this leave the woman?” ... Another student: “A man will go as far as a woman will let him. The girl has to set the standard.”{17}

Implicit in this was a matrimonial strategy based on months of sexual teasing (setting the standard), until the frustrated young man broke down and proposed. Girls had to “hold out” because, as one Journal respondent put it, “Virginity is one of the greatest things a woman can give to her husband.” As for what he would give to her, in addition to four or five children, the young women were vividly descriptive:

... I want a split-level brick with four bedrooms with French Provincial cherrywood furniture.

... I’d like a built-in oven and range, counters only 34 inches high with Formica on them.

... I would like a lot of finished wood for warmth and beauty.

... My living room would be long with a high ceiling of exposed beams. I would have a large fireplace on one wall, with a lot of copper and brass around.... My kitchen would be very like old Virginian ones—fireplace and oven.

So single-mindedly did young women appear to be bent on domesticity that when Beatlemania did arrive, some experts thought the screaming girls must be auditioning for the maternity ward: “The girls are subconsciously preparing for motherhood. Their frenzied screams are a rehearsal for that moment. Even the jelly babies [the candies favored by the early Beatles and hurled at them by fans] are symbolic.”{18} Women were asexual, or at least capable of mentally bypassing sex and heading straight from courtship to reveries of Formica counters and cherrywood furniture, from the soda shop to the hardware store.

But the vision of a suburban split-level, which had guided a generation of girls chastely through high school, was beginning to lose its luster. Betty Friedan had surveyed the “successful” women of her age—educated, upper-middle-class housewives—and found them reduced to infantile neuroticism by the isolation and futility of their lives. If feminism was still a few years off, at least the “feminine mystique” had entered the vocabulary, and even Jill Dinwiddie must have read the quotation from journalist Shana Alexander that appeared in the same issue of Life that featured Jill. “It’s a marvelous life, this life in a man’s world,” Alexander said. “I’d climb the walls if I had to live the feminine mystique.” The media that had once romanticized togetherness turned their attention to “the crack in the picture window”—wife swapping, alcoholism, divorce, and teenage anomie. A certain cynicism was creeping into the American view of marriage. In the novels of John Updike and Philip Roth, the hero didn’t get the girl, he got away. When a Long Island prostitution ring, in which housewives hustled with their husbands’ consent, was exposed in the winter of 1963, a Fifth Avenue saleswoman commented: “I see all this beautiful stuff I’ll never have, and I wonder if it’s worth it to be good. What’s the difference, one man every night or a different man?”{19}

So when sociologist Bennet Berger commented in Life that “there is nobody better equipped than Jill to live in a society of all-electric kitchens, wall-to-wall carpeting, dishwashers, garbage disposals [and] color TV,” this could no longer be taken as unalloyed praise. Jill herself seemed to sense that all the tension and teasing anticipation of the teen years was not worth the payoff. After she was elected, by an overwhelming majority, to the cheerleading team, “an uneasy, faraway look clouded her face.” “I guess there’s nothing left to do in high school,” she said. “I’ve made song leader both years, and that was all I really wanted.” For girls, high school was all there was to public life, the only place you could ever hope to run for office or experience the quasi fame of popularity. After that came marriage—most likely to one of the crew-cut boys you’d made out with —then isolation and invisibility.

Part of the appeal of the male star—whether it was James Dean or Elvis Presley or Paul McCartney—was that you would never marry him; the romance would never end in the tedium of marriage. Many girls expressed their adulation in conventional, monogamous terms, for example, picking their favorite Beatle and writing him a serious letter of proposal, or carrying placards saying, “John, Divorce Cynthia.” But it was inconceivable that any fan would actually marry a Beatle or sleep with him (sexually active “groupies” were still a few years off) or even hold his hand. Adulation of the male star was a way to express sexual yearnings that would normally be pressed into the service of popularity or simply repressed. The star could be loved noninstrumentally, for his own sake, and with complete abandon. To publicly advertise this hopeless love was to protest the calculated, pragmatic sexual repression of teenage life.

The Economics of Mass Hysteria

Sexual repression had been a feature of middle-class teen life for centuries. If there was a significant factor that made mass protest possible in the late fifties (Elvis) and the early sixties (the Beatles), it was the growth and maturation of a teen market: for distinctly teen clothes, magazines, entertainment, and accessories. Consciousness of the teen years as a life-cycle phase set off between late childhood on the one hand and young adulthood on the other only goes back to the early twentieth century, when the influential psychologist G. Stanley Hall published his mammoth work Adolescence. (The > word “teenager” did not enter mass usage until the 1940s.) Postwar affluence sharpened the demarcations around the teen years: Fewer teens than ever worked or left school to help support their families, making teenhood more distinct from adulthood as a time of unemployment and leisure. And more teens than ever had money to spend, so that from a marketing viewpoint, teens were potentially much more interesting than children, who could only influence family spending but did little spending themselves. Grace and Fred Hechinger reported that in 1959 the average teen spent $555 on “goods and services not including’the necessities normally supplied by their parents,” and noted, for perspective, that in the same year schoolteachers in Mississippi were earning just over $3,000. “No matter what other segments of American society— parents, teachers, sociologists, psychologists, or policemen—may deplore the power of teenagers,” they observed, “the American business community has no cause for complaint.”{20}

If advertisers and marketing men manipulated teens as consumers, they also, inadvertently, solidified teen culture against the adult world. Marketing strategies that recognized the importance of teens as precocious consumers also recognized the importance of heightening their self-awareness of themselves as teens. Girls especially became aware of themselves as occupying a world of fashion of their own—not just bigger children’s clothes or slimmer women’s clothes. You were not a big girl or a junior woman, but a “teen,” and in that notion lay the germs of an oppositional identity. Defined by its own products and advertising slogans, teenhood became more than a prelude to adulthood; it was a status to be proud of—emotionally and sexually complete unto itself.

Rock ’n’ roll was the most potent commodity to enter the teen consumer subculture. Rock was originally a black musical form with no particular age identification, and it took white performers like Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley to make rock ’n’ roll accessible to young white kids with generous allowances to spend. On the white side of the deeply segregated music market, rock became a distinctly teenage product. Its “jungle beat” was disconcerting or hateful to white adults; its lyrics celebrated the special teen world of fashion (“Blue Suede Shoes”), feeling (“Teenager in Love”), and passive opposition (“Don’t know nothin’ ’bout his-to-ry ). By the late fifties, rock ’n’ roll was the organizing principle and premier theme of teen consumer culture: You watched the Dick Clark show not only to hear the hits but to see what the kids were wearing; you collected not only the top singles but the novelty items that advertised the stars; you cultivated the looks and personality that would make you a “teen angel.” And if you were still too yoimg for all this, in the late fifties you yearned to grow up to be—not a woman and a housewife, but a teenager.

Rock ’n’ roll made mass hysteria almost inevitable: It announced and ratified teen sexuality and then amplified teen sexual frustration almost beyond endurance. Conversely, mass hysteria helped make rock ’n’ roll. In his biography of Elvis Presley, Albert Goldman describes how Elvis’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, whipped mid-fifties girl audiences into a frenzy before the appearance of the star: As many as a dozen acts would precede Elvis—acrobats, comics, gospel singers, a little girl playing a xylophone—until the audience, “driven half mad by sheer frustration, began chanting rhythmically, ‘We want Elvis, we want Elvis!’ ” When the star was at last announced:

Five thousand shrill female voices come in on cue. The screeching reaches the intensity of a jet engine. When Elvis comes striding out onstage with his butchy walk, the screams suddenly escalate. They switch to hyperspace. Now, you may as well be stone deaf for all the music you’ll hear.{21}

The newspapers would duly report that “the fans went wild.”

Hysteria was critical to the marketing of the Beatles. First there were the reports of near riots in England. Then came a calculated publicity tease that made Colonel Parker’s manipulations look oafish by contrast: Five million posters and stickers announcing “The Beatles Are Coming” were distributed nationwide. Disc jockeys were blitzed with promo material and Beatle interview tapes (with blank spaces for the DJ to fill in the questions, as if it were a real interview) and enlisted in a mass “countdown” to the day of the Beatles’ arrival in the United States. As Beatle chronicler Nicholas Schaff- ner reports:

Come break of “Beatle Day,” the quartet had taken over even the disc-jockey patter that punctuated their hit songs. From WMCA and WINS through W-A-Beatle-C, it was “thirty Beatle degrees,” “eight-thirty Beatle time” ... [and] “four hours and fifty minutes to go.”{22}

By the time the Beatles materialized, on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in February 1964, the anticipation was unbearable. A woman who was a fourteen-year-old in Duluth at the time told us, “Looking back, it seems so commercial to me, and so degrading that millions of us would just scream on cue for these four guys the media dangled out in front of us. But at the time it was something intensely personal for me and, I guess, a million other girls. The Beatles seemed to be speaking directly to us and, in a funny way, for us. ”

By the time the Beatles hit America, teens and preteens had already learned to look to their unique consumer subculture for meaning and validation. If this was manipulation—and no culture so strenuously and shamelessly exploits its children as consumers—it was also subversion. Bad kids became juvenile delinquents, smoked reefers, or got pregnant. Good kids embraced the paraphernalia, the lore, and the disciplined fandom of rock n’ roll. (Of course, bad kids did their thing to a rock beat too: the first movie to use a rock ’n’ roll soundtrack was “Blackboard Jungle,” in 1955, cementing the suspected link between “jungle rhythms” and teen rebellion.) For girls, fandom offered a way not only to sublimate romantic and sexual yearnings but to carve out subversive versions of heterosexuality. Not just anyone could be hyped as a suitable object for hysteria: It mattered that Elvis was a grown-up greaser, and that the Beatles let their hair grow over their ears.

The Erotics of the Star-fan Relationship

In real life, i.e. in junior high or high school, the ideal boyfriend was someone like Tab Hunter or Ricky Nelson. He was “all boy,” meaning you wouldn’t get home from a date without a friendly scuffle, but he was also clean-cut, meaning middle class, patriotic, and respectful of the fact that good girls waited until marriage. He wasn’t moody and sensitive (like James Dean in Giant or Rebel Without a Cause), he was realistic (meaning that he understood that his destiny was to earn a living for someone like yourself). The stars who inspired the greatest mass adulation were none of these things, and their very remoteness from the pragmatic ideal was what made them accessible to fantasy.

Elvis was visibly lower class and symbolically black (as the bearer of black music to white youth). He represented an unassimilated white underclass that had been forgotten by mainstream suburban America—or, more accurately, he represented a middle-class caricature of poor whites. He was sleazy. And, as his biographer Goldman argues, therein lay his charm:

What did the girls see that drove them out of their minds? It sure as hell wasn’t the AllAmerican Boy.... Elvis was the flip side of [the] conventional male image. His fish-belly white complexion, so different from the “healthy tan” of the beach boys; his brooding Latin eyes, heavily shaded with mascara ... the thick, twisted lips; the long, greasy hair.... God! what a freak the boy must have looked to those little girls ... and what a turn-on! Typical comments were: “I like him because he looks so mean” ... “He’s been in and out of jail.”{23}

Elvis stood for a dangerous principle of masculinity that had been expunged from the white-collar, split-level world of fandom: a hood who had no place in the calculus of dating, going steady, and getting married. At the same time, the fact that he was lower class evened out the gender difference in power. He acted arrogant, but he was really vulnerable, and would be back behind the stick shift of a Mack truck if you, the fans, hadn’t redeemed him with your love. His very sleaziness, then, was a tribute to the collective power of the teen and preteen girls who worshipped him. He was obnoxious to adults—a Cincinnati used-car dealer once offered to smash fifty Presley records in the presence of every purchaser—not only because of who he was but because he was a reminder of the emerging power and sexuality of young girls.

Compared to Elvis, the Beatles were almost respectable. They wore suits; they did not thrust their bodies about suggestively; and to most Americans, who couldn’t tell a blue-collar, Liverpudlian accent from Oxbridge English, they might have been upper class. What was both shocking and deeply appealing about the Beatles was that they were, while not exactly effeminate, at least not easily classifiable in the rigid gender distinctions of middle-class American life. Twenty years later we are so accustomed to shoulder-length male tresses and rock stars of ambiguous sexuality that the Beatles of 1964 look clean-cut. But when the Beatles arrived at crew-cut, precounterculture America, their long hair attracted more commentary than their music. Boy fans rushed to buy Beatle wigs and cartoons showing well-known male figures decked with Beatle hair were a source of great merriment. Playboy, in an interview, grilled the Beatles on the subject of homosexuality, which it was only natural for gender-locked adults to suspect. As Paul McCartney later observed:

There they were in America, all getting housetrained for adulthood with their indisputable principle of life: short hair equals men; long hair equals women. Well, we got rid of that small convention for them. And a few others, too.{24}

What did it mean that American girls would go for these sexually suspect young men, and in numbers far greater than an unambiguous stud like Elvis could command? Dr. Joyce Brothers thought the Beatles’ appeal rested on the girls’ innocence:

The Beatles display a few mannerisms which almost seem a shade on the feminine side, such as the tossing of their long manes of hair.... These are exactly the mannerisms which very young female fans (in the 10-to-14 age group) appear to go wildest over.{25}

The reason? “Very young ‘women’ are still a little frightened of the idea of sex. Therefore they feel safer worshipping idols who don’t seem too masculine, or too much the ‘he man.’ ”

What Brothers and most adult commentators couldn’t imagine was that the Beatles’ androgyny was itself sexy. “The idea of sex” as intercourse, with the possibility of pregnancy or a ruined reputation, was indeed frightening. But the Beatles construed sex more generously and playfully, lifting it out of the rigid scenario of mid-century American gender roles, and it was this that made them wildly sexy. Or to put it the other way around, the appeal lay in the vision of sexuality that the Beatles held out to a generation of American girls: They seemed to offer sexuality that was guileless, ebullient, and fun—like the Beatles themselves and everything they did (or were shown doing in their films Help and A Hard Day’s Night). Theirs was a vision of sexuality freed from the shadow of gender inequality because the group mocked the gender distinctions that bifurcated the American landscape into “his” and “hers.” To Americans who believed fervently that sexuality hinged on la diff¿vence, the Beatlemaniacs said, No, blur the lines and expand the possibilities.

At the same time, the attraction of the Beatles bypassed sex and went straight to the issue of power. Our informant from Orlando, Maine, said of her Beatle- manic phase:

It didn’t feel sexual, as I would now define that. It felt more about wanting freedom. I didn’t want to grow up and be a wife and it seemed to me that the Beatles had the kind of freedom I wanted: No rules, they could spend two days lying in bed; they ran around on motorbikes, ate from room service.... I didn’t want to sleep with Paul McCartney, I was too young. But I wanted to be like them, something larger than life.

Another woman, who was thirteen when the Beatles arrived in her home city of Los Angeles and was working for the telephone company in Denver when we interviewed her, said:

Now that I’ve thought about it, I think I identified with them, rather than as an object of them. I mean I liked their independence and sexuality and wanted those things for myself.... Girls didn’t get to be that way when I was a teenager—we got to be the limp, passive object of some guy’s fleeting sexual interest. We were so stifled, and they made us meek, giggly creatures think, oh, if only / could act that way, and be strong, sexy, and doing what you want.

If girls could not be, or ever hope to be, superstars and madcap adventurers themselves, they could at least idolize the men who were.

There was the more immediate satisfaction of knowing, subconsciously, that the Beatles were who they were because girls like oneself had made them that. As with Elvis, fans knew of the Beatles’ lowly origins and knew they had risen from working-class obscurity to world fame on the acoustical power of thousands of shrieking fans. Adulation created stars, and stardom, in turn, justified adulation. Questioned about their hysteria, some girls answered simply, “Because they’re the Beatles.” That is, because they’re who I happen to like. And the louder you screamed, the less likely anyone would forget the power of the fans. When the screams drowned out the music, as they invariably did, then it was the fans, and not the band, who were the show.

In the decade that followed Beatlemania, the girls who had inhabited the magical, obsessive world of fandom would edge closer and closer to center stage. Sublimation would give way to more literal, and sometimes sordid, forms of fixation: By the late sixties, the most zealous fans, no longer content to shriek and sob in virginal frustration, would become groupies and “go all the way” with any accessible rock musician. One briefly notorious group of girl fans, the Chicago Plaster Casters, distinguished itself by making plaster molds of rock stars’ penises, thus memorializing, among others, Jimi Hendrix. At the end of the decade Janis Joplin, who had been a lonely, unpopular teenager in the fifties, shot to stardom before dying of a drug and alcohol overdose. Joplin, before her decline and her split from Big Brother, was in a class by herself. There were no other female singers during the sixties who reached her pinnacle of success. Her extraordinary power in the male world of rock ’n’ roll lay not only in her talent but in her femaleness. While she did not meet conventional standards of beauty, she was nevertheless sexy and powerful; both genders could worship her on the stage for their own reasons. Janis offered women the possibility of identifying with, rather than objectifying, the star. “It was seeing Janis Joplin,” wrote Ellen Willis, “that made me resolve, once and for all, not to get my hair straightened.” Her “metamorphosis from the ugly duckling of Port Arthur to the peacock of Haight Ashbury”{26} gave teenage girls a new optimistic fantasy.

While Janis was all woman, she was also one of the boys. Among male rock stars, the faintly androgynous affect of the Beatles was quickly eclipsed by the frank bisexuality of performers like Alice Cooper and David Bowie, and then the more outrageous antimasculinity of eighties stars Boy George and Michael Jackson. The latter provoked screams again and mobs, this time of interracial crowds of girls, going down in age to eight and nine, but never on the convulsive scale of Beatle- mania. By the eighties, female singers like Grace Jones and Annie Lenox were denying gender too, and the loyalty and masochism once requisite for female lyrics gave way to new songs of cynicism, aggression, exultation. But between the vicarious pleasure of Beatle- mania and Cyndi Lauper’s forthright assertion in 1984 that “girls just want to have fun,” there would bp an enormous change in the sexual possibilities open to women and girls—a change large enough to qualify as a “revolution.”

2. Up from the Valley of the Dolls: The Origins of the Sexual Revolution

Anne Welles’s personal sexual revolution was indistinguishable if om her rebellion, in an unconsciously feminist fashion, against the rigid sex roles of small-town America. Anne was the heroine of Jacqueline Susann’s 1966 best-seller, Valley of the Dolls, and for Anne, like Susann herself, the big city—in both cases, New York— promised freedom and inexhaustible adventure:

She would never go back to Lawrenceville! ... She had escaped. Escaped from marriage to some solid Lawrenceville boy, from the solid, orderly life of Lawrenceville. The same orderly life her mother had lived. And her mother’s mother. In the same orderly kind of a house. A house that a good New England family had lived in generation after generation, its inhabitants smothered with orderly, unused emotions, emotions stifled beneath the creaky iron armor called “manners.”{27}

In no small part, it was the sexlessness of life in Law- renceville that drove Anne to a cramped apartment and an uncertain secretarial career in New York. She recalls asking her mother, “When a man takes you in his arms and kisses you, it should be wonderful, shouldn’t it? Wasn’t it ever wonderful with Daddy?” To which her mother replies stiffly, “Unfortunately, kissing isn’t all a man expects after marriage.”

In 1966–67 the media began to talk about “the sexual revolution,” and the sexual playfulness of the emerging counterculture was only one element of the change. Novels like Valley of the Dolls, which seemed at the time to border on pornography, were themselves a sign of the “revolution.” Human Sexual Response, by Dr. William Masters and Virginia Johnson, also published in 1966, was to become one of its major ideological manifestos. The women’s liberation movement and the mass spread of feminist consciousness were still two or three years ahead, but the designation of a sexual “revolution” implied a change that went beyond manners and mores to fundamental relationships of power. Women’s sexual revolution grew out of the same frustrations and emerging opportunities that inspired the feminist movement and, like it, initially represented the aspirations of the “new woman”—urban, single, educated—who had to overcome both the puritanism of small-town America and the smothering conformity of suburban married life.

By the early sixties, thousands of young women, like the fictional Anne Welles, were rejecting the lockstep sequence that led from college or high school graduation directly to marriage and maternity. They expected to spend a few years on their own, working and dating, and not just as a way of passing time until “Mr. Right” arrived. Being single had its own rewards, especially in a city packed with other young people and far from parental oversight. While the teens and preteens were still shrieking over the Beatles—and anticipating a more adventurous sexuality—young women in their twenties were already carving out a new kind of sexual identity. Sex had been defined as an adjunct to marriage, as a means to getting married, and as proof of a “mature acceptance of the female role.” But for women who were trying out new roles, even on a temporary basis, the old rules and definitions would not do.

The birth control pill, which first became commercially available in 1960, contributed to women’s sexual revolution but by no means caused it. The causes of the sexual revolution were more sociological than technological: Without a concentration of young, single women in the cities, there would have been no sexual revolution. But without the pill, there would still have been the diaphragm; and for many young women who came of age in the prepill years, that first diaphragm, discreetly packed in purse or college book bag, was both the symbol and the instrument of sexual liberation. The pill was more convenient—though, as women were to discover later in the decade, it was also far more hazardous than the diaphragm. But its real function was, in a sense, to legitimize a sexual revolution already in progress: The existence and widespread marketing of a technology for presumably effortless contraception was evidence that millions of women (almost 6 million by 1965), single as well as married, were “doing it”—and, apparently with the blessings of the medical profession, getting away with it too.

The Crisis of Married Love

The sexual revolution reflected not only the opportunities opening up to the “new,” single women, but the discontent of the married majority. The only officially acceptable setting for an active sex life was still the bedroom—in a house, preferably a new suburban split- level, not a makeshift apartment. Outside of a small avant-garde, most young women still expected their single years to culminate in marriage, which, ideally, would be a source not only of financial security but of companionship and sexual fulfillment. But by the early sixties, it was clear that all was not well even within the “ideal” marriages of well-adjusted, educated, middle- class women. To Betty Friedan, who remains our best chronicler of such women’s frustrations on the eve of the feminist revival, it seemed that a sexual revolution, of a fairly nasty and unrewarding type, had already taken place by the early sixties. The housewives she surveyed for The Feminine Mystique seemed to be pouring the energies that might have gone into careers or other “larger human purposes” into a vacant and obsessive search for sexual fulfillment. “The mounting sex-hunger of American women has been documented ad nauseam,” she wrote, and was reflected in the salaciousness of best-sellers addressed to women (Peyton Place was the most egregious example), and what she saw as a “joyless” preoccupation with sexual technique.{28}

The changes Friedan perceived had less to do with actual sexual practice than with the way women thought about sex and the emotional intensity they brought to the subject. She attributed the new way of thinking about sex in large part to the Kinsey reports, both what they reported “and the way they reported it”—which was dryly, and with masses of statistics, as if sex had nothing to do with human feelings. Like most critics of Kinsey (and later, of Masters and Johnson), she believed that a purely scientific approach to human sexuality was necessarily depersonalizing and possibly an invitation to licentiousness. The Kinsey reports (one on male sexuality, in 1948, and one on female sexuality, in 1953) “reduced [sexuality] to its narrowest physiological limits.” In particular, Friedan observed, they treated “sexuality as a status-seeking game in which the goal was the greatest number of ‘outlets,’ [or] orgasms.”{29}

In fact, the “discourse” on sexuality—the collective way of thinking and talking about it—had been shifting decisively throughout the post-World War II period. The vague references to sexual “satisfaction” or “fulfillment” that had characterized sexological writing earlier in the century were being replaced by a one-word description of a physiological event—“orgasm. In part, the new emphasis on the orgasm as the touchstone of sexual experience came from the émigré psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, who attributed the orgasm with a mystical, redemptive power to heal and inspire. His influence, however, was largely limited to an intellectual avant-garde. Most Americans learned to think of sex in terms of orgasms from Kinsey, and his interest in them was far more prosaic than Reich’s. A scientist, Alfred Kinsey was determined to make his study of sex quantitatively precise; and that meant he needed some way to measure the amorphous notion of sexual experience. He needed something to count, and what he chose to count was orgasms.

The Kinsey reports were sensational for their revelations about the sheer volume of extramarital and often deviant sex in pre-sexual-revolution America. But it was his methodology, rather than his findings, that had a lasting effect on how Americans think about sex. His focus on the orgasm count—as opposed to, say, the number of “affairs” or “acts of penetration”—carried with it the implicit notion that all routes to orgasm are somehow equivalent or at least equally worthy of note. Sex, as studied by Kinsey and his colleagues, did not necessarily include love, heterosexual attraction, or even any human interaction. It included homosexual sex, masturbation, and even bestiality—all of which were horrifyingly deviant but which nonetheless showed up in the bottom line, the orgasm count. The latent message, which did not achieve widespread acceptance for decades, was that if we were to be objective about sex, we would have to learn to be a little less judgmental about how it was defined.

Another message, which was much more readily áb- sorbed even in the fifties, was that men and women were not so different sexually after all. In Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, Kinsey and his colleagues asserted that

in spite of the widespread and oft-repeated emphasis on the supposed differences between female and male sexuality, we fail to find any anatomic or physiological basis for such differences.{30}

In particular, “orgasm is a phenomenon which appears to be essentially the same in the human female and male.” These conclusions contradicted the dominant, Freudian theories of female sexuality that still prevailed in most popularly available information and advice, but they were hard to ignore. If sexology was a science, and if the orgasm was its principle “unit of measurement,” then surely women’s orgasms had to “count” as much as men’s.

The Kinsey reports encouraged women to take a more hardheaded—the critics said “selfish”—view of sex. Vaguer descriptions of sexual pleasure, like “satisfaction” or “fulfillment,” could easily be confused with intangible feelings of love and affection. But orgasm was a definite event; it could happen quite independently of any human feeling. Thus sex was not just an extension of love but a separate realm within which a marriage could either falter or succeed. Within this realm, there was little ambiguity: While a woman might be aware of more or less “satisfaction,” she could actually count orgasms. If American women were beginning to think of sex as a “status-seeking game, as Friedan worried, there was now a way to tally the score.