Bernard Charbonneau

The Garden of Babylon

Nature, a Revolutionary Force

Editor’s Note from the 2002 French Edition

Part One: The City in the Countryside

2. From the city to the urban agglomeration

4. The city dweller isolated from the cosmos

Part Two: Towards the Total City

2. The threat of ischemic stroke

III The birth of the rural suburb

1. Agricultural “revolution” and industrial “revolution”

2. Agricultural “revolution” and political “revolution”

3. The Plan and the countryside

IV Aspects of the new garden suburb of Greater Paris

3. Rural France faces its own end

Part Three: The “feeling of nature”, an industrial product

1. The feeling of nature, a sign of contradiction

2. The song of the bucolic dreamers

3. The intellectual and the noble savage

1. Back-to-nature myths: the myth of the island

2. From the Garden of Eden to the national park

IV Views of the sea and the mountains

Part Four: The failure of the “feeling of nature”

1. How, as a reaction against organization, the feeling of nature leads back to organization

3. The trout and the oxygen level

III Large-scale planning and green spaces

VI The failure of the back-to-nature revolt

1. The failure of individual escapism

2. The failure of back-to-nature communities

Editor’s Note from the 2002 French Edition[1]

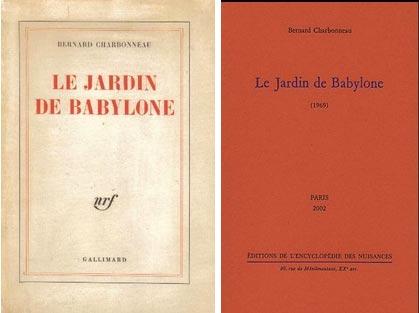

Of the twenty or so books written by Bernard Charbonneau (1910-1996), all devoted to what he called the “Great Transformation” of the 20th century, it was in The Garden of Babylon that he most effectively demonstrated how, after having devastated nature, industrial society ended up annihilating it by “protecting it”, organizing it; and how, at the same time, with this artificialization, opportunities for human freedom also disappeared. This book originated from a fifty-page text that Bernard Charbonneau circulated in 1937-1938 among circles associated with the magazine, Esprit: “The Feeling of Nature, a Revolutionary Force”. In this text he attempted to establish the basis for a Federation of the Friends of Nature, whose statutes were included at the end of the text. The outbreak of the war ruined any hopes for this project, and it was during the solitude of those years that he returned to the text, which he completed in 1944—under the title, Pan Is Dying—with a phenomenology of the city and the countryside that would become the first part of The Garden of Babylon, published twenty-five years later by Gallimard. Since then, along with the “total suburb”, a kind of environmental protection ruled by the recipes of façadism has spread everywhere, as in those forests of the Great Canadian North devastated by the paper industry, where a fringe of trees about twenty meters wide is left intact to preserve appearances for ecotourism and color photography. And it is not the least merit of The Garden of Babylon that it so precociously denounced what the “defense of nature” would necessarily become as soon as it separated its cause from that of freedom; the disgraceful regression that political environmentalism constitutes from this point of view was therefore judged long in advance.

***

The Garden of Babylon

Upon the dust of Eden a city was founded, a city whose empire spanned the Earth. But the marvel of Babylon is a garden, suspended at the summit of its masses of stone. Some trees and flowers, fallen from the hands of God, that men may gather some day….

There was a time when there was no nature for men; and we are now living at the dawning of that other time in which nature will certainly cease to exist. At the beginning—for some individuals and some countries, it was not so long ago—there was no nature. No one had a name for it, because man had not yet distinguished himself from nature and was incapable of conceiving it. Individuals and societies were then encompassed by the cosmos. An omnipresent power, sacred because it was invincible, everywhere lay in wait for human weakness. Civilization was only a flickering light maintained at the price of an overwhelming effort in the midst of the jungles. Floods seething with monsters proclaimed their reign. Life, like fire, was nothing but an uncertain flame, lost in an ocean of darkness. The sun’s victory is in vain; every sunset brings the defeat of the day and the triumphant return of the infernal powers. How could our ancestors have spoken about nature? They lived it, they were themselves nature: brute force, feral instincts. They did not know things, but spirits; in the shadow in which they were still submerged, the trees and the rocks confusedly acquired superhuman forms and life. Peasants and heathens, they were incapable of loving nature; they could only fight against it or worship it.

Everything changed; but at first imperceptibly. It might have been under the sun of Greece. In that arid land where even the night was transparent, the plains were broken up by mountains and the sea was sprinkled with islands, man and the individual found a space and an environment that was suited to his measure; and in the clarity of reason, monstrous forms petrified into objects. However, it was above all in Judea where nature was born, with the Creation: when light was separated from darkness, spirit from matter. From then on, God was only God and things were only things. By creating it, Yahweh had profaned the cosmos and man could set his hands on it. The cosmic order could still have its impact; but it no longer had authority over the human spirit: it had lost its soul. It became possible to understand it and to act on it. Necessity was only necessity; even provisionally crushed, the revolt of human freedom was unleashed forever.

Then, the rule over and the feeling of nature grew in parallel. Science penetrated the mechanism of the cosmos and technology made it possible to transform it. But this transformation, gradually accelerating, was at first limited to particular places in certain countries. In the West, man lived in the artificial environment of the cities, but at his doorstep the countryside began and, with it, nature. Thus, up until the Second World War, the people of France knew a transitional society where the past and the future coexisted: which allowed the enjoyment of the pleasures of nature thanks to progress.

Thus, along with the city, the need to escape from the city also grew. The feeling of nature appears where the bond with the cosmos has been broken: when the land is covered with houses and the sky is filled with smoke; where industry, or the State, imposes its reasons and its disorder. The feeling of nature is not at home among primitive peoples or the peasantry, but among the bourgeoisie; it began with the “industrial revolution” and gradually spread to the countries and classes that were engulfed by that revolution. Because machines exist, man boards a machine to flee from the machine. From the hill to the mountain and from the mountain to the peak; from the fields to the desert and from the coast to the high seas, the crowd flees from the crowd, the civilized from civilization. This is how nature disappears, destroyed by the very sense that discovered it, as much as by the expansion of industry.

Today, however, the countryside is being urbanized and Europe is becoming a single unified suburb. A new stage is therefore taking shape in which, because nature will no longer exist, the feeling for it will have to disappear, too. Since the bulk of the population will be concentrated in a diffuse expanse of cities, the countryside will no longer exist; there will only be zones devoted to industries of labor, or to those of leisure. Nature will no longer exist; just as in the past man was part of the cosmos, he will now exist within the space organized by Regional Planning. A single system will define the gestures of the worker in the factory and his vacations in the countryside. The same scientific explanation will be applied to spirit and matter, and technologies will be assigned the task of imposing order on man instead of his environment. Thus, everything that one once thought was distinct and separate will be reintegrated.

This is the cycle that will be described in this book. But before beginning, and in order to prevent any misunderstandings, I owe the reader some clarifications with respect to my method. The author of this work is neither a scientist nor a writer, nor even a philosopher; he is simply a man who puts his capacity for thought into practice. This will not involve knowing facts in detail, but reflecting totalities whose enormity is imposed as evidence and which every conscious individual with a minimum amount of education is in a position to discover in his own life. This reflection implies making use of reason; however, insofar as the splendor and decline of nature are not ideas, but realities—among others, that human reality that is manifested in mythology—their representation is just as important as their analysis. Colors and song, whose use is today a monopoly of literature, just as reason is the monopoly of science, are indispensable for the outward, and above all, the inner description of the phenomenon. The reader will forgive me, then, if I do not adhere to the currently accepted genres. Believe me, it is not from ignorance.

And, finally, since real objectivity is based on the consciousness of one’s own points of view, I have to confess that the author is a human being and undertakes his critique from that perspective. In the final analysis, “nature” is only one of the names that man has given it: it was no mere coincidence that the century that discovered nature was also the century of the individual and his freedom. Nature is at the same time the mother who has given birth to us and the daughter we have conceived; if it disappears, it is man who will regress into chaos. Therefore, it is nature that must be taught and defended.

Part One: The City in the Countryside

Until the great wave of expansion of the mid-twentieth century, industrial societies were characterized by the confrontation between the future and the past: this translates, from the geographical point of view, into the contrast between the city and the countryside. On the eve of the Second World War, the center of the metropolis was already ablaze with the glow of neon lights and a sea of automobiles was beginning to flow through its streets; on the heights of Ahusquy, however, one only heard the sound of a trickle of water falling on a pile of rocks; and the gestures of the shepherd who kindled a fire under his iron pot were still the same as those of Adam. And this contrast was manifested not only on the terrain, but also in the spirit of the men who lived during that time. Peasants who dreamed of the city, and urbanites who dreamed of the countryside; that is what we were.

During the first stage of the industrial transformation there were only cities scattered in the countryside: islands, at most an archipelago, of stone, asphalt and steel; rare were the countries where, as in Lancashire or the Ruhr, these islands merged and formed a province of factories and houses. The wilderness then extended infinitely like the sea and the city rose up from it like a reef: its monuments hardly stood out among the trees and only a short climb was needed to reach their summits, a fruit of stone coiled in the bosom of immensity. There were few cities, like London or Paris, that were so large that the eye or the powers of thought could not grasp their form.

The city, a microcosm created by man, which petrified his dreams into towers and columns, his reason into squares and avenues; or even into gardens, although we had to wait until the classical era and above all until Romanticism for man to dare to introduce his old enemy, nature, within the walls of Troy, which had been besieged up until that time, on every side, by that sea of green. The city of men: all of it well defined by walls or boulevards, where everything, like its streets, has a meaning that leads to the center. Fruit of another nature, human nature, like a hill rising towards the sun; a tangled labyrinth clustered around a bell tower; a solemn project in which reason, crystallized reason, is a palace. The city of men, although not yet the city of automobiles. The city of individuals, and of their speech, whose heart is a forum rather than a parking lot. But between the city and the countryside something has already begun to proliferate, something that does not have a name: the vague limbs of the outskirts, neither city nor countryside, neither nature nor culture, but a chaotic half-finished work, a front on which the labor of man advances so rapidly that it does not acquire a form.

The city in the countryside: two antithetical worlds, but for that very reason complementary. It is the green immensity that gives its value to the closedoff universe built of stone; and it is the closed-off and artificial universe that gives its value to the changing enormity that besieges it. Nature is beautiful for the man of the city, culture is priceless for the peasant! Perhaps never before, in a few minutes by rail or by car, was it possible for man to thus change his world and his century. Never before could he play on two boards, and give two dimensions to his thought and his life. But this state of affairs lasted only an instant, and I fear that we have allowed it to pass us by. What could have been elements for a decision are now only testimonials of the past.

For the city, just like the countryside, is now tending to dissolve into a single industrial or residential suburb. A world in which the last farms and the last cities will sink into an ocean of apartment complexes, factories and “green spaces”, just as villages were once lost in the forests. The confusion of the city and the countryside is only the geographical aspect of the constitution of a total metropolis: in the future there will no longer be any way to escape from either Babel or the belly of Great Pan.

I. The Death of Great Pan

1. Far from Eden

Nature is an invention of modern times. For the Indian of the Amazonian jungle, or—closer to home—for the French peasant of the Third Republic, this word has no meaning. For both of them are still connected to the cosmos. At first, man was not distinguished from nature; he was part of an unbroken universe where the order of things was the continuation of the order of his spirit: the same breath gave life to individuals, societies, rocks and springs. When the breeze caressed the crowns of the oaks of Dodona, a symphony of voices resounded in the forest. For the primitive heathen there was no nature, there were only gods, beneficent or terrible, whose forces, as well as mysteries, surpassed human weakness from infinite heights.

In opposition to the irresistible current of natural forces, the individual and human society could only survive by fighting against those forces. They could not yet allow themselves the luxury of contemplation and love. They had to devote themselves body and soul to struggle, and mercilessly repel the always renewed attack of the green tide: cut, burn, give order to the chaos. If there were beautiful, lovable things, they were at first the precarious works of man. But this permanent war against nature was at the same time characterized by respect. The enemy was too great and too terrible not to be regaled with constant honors. To fight against him one needed his consent, because one needed to use his own forces against him. The order of things was a sacred order, in which man, forced to intervene to survive, labored in fear and trembling. Strict rituals dictated his conduct and served to exculpate it.

Of course, this equivocal respect for the cosmic order demonstrated that the seed of rupture and revolt appeared very early in the human species. By personifying the powers of nature in human forms, Greek paganism preserved the continuity between the cosmos and man, but began to strip the former of its mystery. When the storm was only the anger of the deceived husband, its objective examination was aborted. Later, Prometheus would try to steal the fire of heaven. He was too premature, however, and his sacrilege was punished.

Today, now that Prometheus unbound has become God, the modern individual recalls that lost childhood with nostalgia. More or less conscious, the memory of Eden still torments industrial societies. It is the yearning for a magical universe in which everything was alive, where everything had a

meaning and man was unacquainted with the curse of labor and time. Our revolutions and our pastimes aspire to nothing else. But an angel still guards the gates of these untimely paradises that were so laboriously constructed. He is called a soldier, a policeman, a warden. They are the guardians of the gates and prohibit us from entering; for to guarantee the security of this reconquered nature and freedom we must multiply the laws. We have been expelled from Eden forever. Now we can only look at it from the outside: never again shall we tread its flowery lawns. For us it is now only a dream or an image, a promise or a yearning: it will never be present again. Our lot is to grow old, die, reflect and struggle. If, some day, we are tempted to live this dream to its ultimate consequences, it is likely that we shall awaken imprisoned in this total universe and that what we shall discover will be hell.

For after Year One, everything changed. Whereas Prometheus, the ManGod, failed, the God-Man was victorious; only a being who was more divine could defeat Zeus. Great Pan died; and it was probably the God of the Christians who killed him: everything sacred, and at the same time everything human, was withdrawn from things. Starting with Genesis, the cosmos ceased to be God in order to become the creation of a divine person. He made the light, which separated day from night; there was an evening and a morning. The land emerged from the waters and from its nocturnal dream: a world that was innumerable yet exact, in which each object had its form and its own being. And God created Adam; and although he drew him from the dust of the Earth, he created him in His image and semblance. His body could participate in the universe, but his spirit belonged to another realm. And God made him the sovereign of His creation: a subject.

In the Garden of Eden, however, man and things nonetheless continued to live in God: there was not yet any sin or consciousness of Good and Evil. For this it was necessary for man, by destroying part of the work of his Creator, to create himself by sinning. Abiding by the counsel of Eve and the serpent, he ate the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil. He was now capable, just like God, of knowing them. But he was expelled from Eden, and cast upon the Earth, and plunged into need and into the evil that his spirit had recognized. And from then on, while the human spirit arduously attempted to once again find order in the chaos, his body had to endlessly reconquer it at the price of hard work. Thus, shackled by the weight of the flesh at the very summit of things, while his spirit was stretched taut towards God, Adam, like Prometheus, was abandoned to fundamental suffering and anxiety.

After this rupture, however, he had to once again be created by divine Love. If the Incarnation of the God-Man sealed a new alliance between God and his creature, it also established a link between God, man and his creation. The New Testament does not invest the forces of nature with divinity any more than the Old Testament; yet it is nonetheless pervaded with love for them. Mistrust of and Puritanical hatred for a nature that bears the stigma of sin, characteristic of the Reformation and the Counter-reformation, are completely absent from the Gospels. To the contrary, evangelical simplicity is draped in all the colors of spring. The universe of the Christian word and life is not that of the city, or that of the factory, but that of the vineyards and shepherds. Creation is not the enemy, but the work of God: an immense parable in which, if one knows how to read it, one can discover His will. In the parable of the birds of the field, nature—spontaneity, childhood, rather than work or worries—is set forth as an example. “Look at the birds of the air…” is a scandalous response to the curse of Genesis: “You shall earn thy bread with the sweat of your brow.” And since that time, we have sometimes obeyed the will of God by forgetting his curse.

Christianity still directed its faithful to deserts and sacred places, but in a different spirit. The desert is no longer just the refuge of demons. Ever since the Exodus prescribed by Jehovah exorcised it, it became the place of retirement of prophets and hermits, the symbol of the deprivation and solitude of the new Adam. And the forests that were the refuges of wild animals became the refuges of hermits. Christian faith did not abolish sacred places, it only changed their meaning: Sinai and Tabor were still holy mountains. But the Ascension expelled the gods from their summits, and man could now climb and stand upon their vacated pedestals. Even so, he did not make this ascent without due respect, for it is ultimately based on his own efforts that he can measure the whole depth of the heavens: the enormous void that separates him from the transcendent God.

Thus, the Christian creation is one of the hidden sources of the idea and the feeling of nature. It establishes a living relation between man and nature, for it is a paradoxical and ambiguous relation. Like God, in whose image he was created, man is distinguished from creation. He is no longer within it, and it is no longer within him, but presented to his consciousness: deprived of soul, it is present before the subject as an object. Man can act on it and transform it in his own way: his relation with it is no longer one of submission, but of combat. The flaming sword of the Archangel was capable of casting man upon the Earth, but it did not cast him into Hell; despite everything, he is not entombed in matter. And while he is still a determinate, finite and mortal being, Christ has granted him the freedom of the children of God. Thus, human freedom would discover and domesticate nature. However, the old bond is succeeded by a new one. Man begins to love the cosmos because it has become nature: because it is different from him, and because it is no longer populated by spirits. The oaks of Dodona are silent; only the wind still arouses the murmur of the leaves, and now their murmur consoles our anxiety. Dawn has broken, Olympus has lost its superhuman form; it has petrified into a pile of rocks. And man, curious, approached it. His hands grasped the lifeless stone; to get a better look, he ascended the mountain, attracted to the summit by a kind of intoxication. He had to look for a path, force his way, scoff at the abyss. And in this hand-to-hand fight with the mountain he found peace.

2. From Creation to Nature

Creation has become nature. For as man distinguished himself from the cosmos, he experienced the need to reintegrate with it. As his knowledge and dominion over things increased, his nostalgia for the time when these things had a magical dimension was awakened. As the individual asserted himself in the face of the universe and society, his need to cease to be alone and to find himself in harmony with both the universe and society increased. As the unbearable sun of consciousness reached its zenith, the nostalgia for the original innocence was awakened: the nostalgia for the time of nature.

Just like progress in the sciences and technology, nature is the daughter of the affirmation of the person and his freedom. Just as the personal God is the author of creation, the modern individual is the author of nature: it is no accident that the most important of its inventors was the Protestant, Rousseau. Since Eden is lost, it has to be recovered. Because the individual cannot rule his passions and escape the Fall of Man, Rousseau had to reply that the original state was the state of nature—of innocence. Rousseau’s good and rational man was the invention of a Calvinist sinner. Removing from the Christian faith its contradictory signs—evil, the personal and incarnate God—the Savoyard curate tried to reintegrate God into the cosmos, but he was too late. Nature is man’s mother: the model of all society. The end is the beginning. The goal of civilization is the noble savage; the goal of the revolutions, the return to natural law. The ideal constitution is only a return to the primitive social contract. Rousseau’s nature is only the projection of the demands of the human spirit upon what exists. Ultimately, it is nothing but a Christian super-nature that does not dare to speak its name.

In a way, the solitary wanderer was not mistaken: a profound bond links freedom and nature. In a civilized society, in which social constraints have replaced the adversities of nature, in a society in which “that is the way it is” no longer designates the will of God and the fact that there is no court of appeal against his afflictions, but the decrees of History, the demand for freedom ends up being the demand for nature. It was inevitable that man, once he was no longer the sacred being made in the image of God, would become a natural being, one that society cannot touch without meddling with the perfect work of the great architect. But this intangible and fundamental nature, these natural rights: this human nature—does it still live up to its name?

When the weight of social conformism replaces the natural environment, the rights and duties of the free being become for the individual the rights and duties of the “natural” being—today we would say, the “authentic” being. When the vestments of the social being fit him like a second skin, primitive nudity becomes liberation; when morality becomes a new fate, sometimes the individual must break the rules in order to follow his instincts. This nature—is it not an ethic?

It is true that there is a relation between nature and freedom, but it is a paradoxical relation. There is no freedom without nature; more than anyone else, the free man needs space, time and silence. He needs the desert, the seas and the forests, the authenticity of creation in the form that it had when it first came from the hands of God: but this is because he has lost it. He needs to once again find spontaneity, simplicity; but these qualities now lie beyond, and no longer within, material and intellectual progress. We can reproach Rousseau, like all of his contemporaries, for not having been aware of this paradox, for having associated, for example, as something that was self-evident, nature and revolution, when revolution is above all an act of violence against nature, especially against human nature. And those who seek to lead human nature by force to primitive innocence are those who attack it most profoundly.

The mistake of Rousseau and of his contemporaries lies in the fact that they tried to reconstruct, by way of their discourses, the unity that Christian faith had destroyed at its root: the good, rational and abstract man of the Social Contract is the response to the real sinner of the Confessions. They could only end up with a “feeling of nature” and a vague pantheism, like that of Victor Hugo, that makes nature, against all evidence, the generous and benevolent mother of man. The fact that they did not grasp the paradox of nature, its intimate connection with freedom and the individual, led them to disconnect the two terms of the contradiction. Love for and hatred of nature thus developed simultaneously in the heart of the modern individual. That is why, under the pretext of liberating it, he accepts destroying it.

Man having emerged from the cosmos, this is how he dominated nature, both intellectually as well as practically. And this is how, by distinguishing himself from it, he has learned to distinguish it and love it. There is no nature without civilization: one must live amidst the cement of the cities to marvel at the sky and the trees. But there is no civilization without nature, either. To build a civilization is only a passionate game for men if it is necessary to conquer it, as the pioneers of the past were forced to do, in a universe that rejected them. And the refuge that society offered them only preserves its value if, on the other side of the walls of the house, the wind blows and the rain rattles against the windows. Where would the splendor of the day be without the night to give it all its brilliance?

3. The war against nature

A new God profaned the universe; and this God was also man. At that moment Jupiter and Neptune vanished to leave man alone in creation; participating in it, and nonetheless free within nature, which is what it was called by man because he no longer perceived it in the guise of his human hopes and fears. He no longer personified it because he knew it and loved it for itself. Nature was no longer sacred, but from then on, it was not respected, either. In a way, at the very moment when it was spoken of there was no more nature, but only things to exploit, from which one could extract power or derive enjoyment; esthetically, for example. Man, who had in another time lost himself by merging with nature, today runs the risk of destroying himself by rejecting the bond that connects him to nature.

His first victories were due to his capacity for association, to human society. Civilization or culture is an anti-nature, especially at its beginnings, when man felt too weak to have any sympathy for the enemy. Man began to dominate nature even before he possessed effective machines, when state organization allowed him to accumulate the forces of an enormous number of men. Nature was dominated at first, and very precariously, by the great empires, especially Rome. Rome managed to rule an area that was in the human sense much more vast than our contemporary world, and it did so without airplanes or railroads, thanks to its great roads and, above all, the perfection of its army and its administration. But this victory was superficial, because the Roman state was incapable of creating a spiritual and technical infrastructure. Almost everywhere, man was still the man of old: the pagan peasant. A tiny layer of high functionaries and educated people was papered over the primitive lava of the rural masses. An endless ocean of barbarism battered the fragile levees of the limes; and another barbarism, much more profound, threatened to sweep away the superficial order of official rationalism and academicism from within the empire. Classical culture and reason were victorious in the metropolises where, from the thickets of Baetica to the peat bogs of Caledonia, the same model proliferated: the City. But these rootless populations, isolated in the moorlands or the settled countryside, lacked an economic base and the instrumentalities that would have allowed them to dominate their surroundings. They were administrative centers, without any life of their own, unlike the Greek cities. A blank, inert order, transplanted over vast areas in which forests, epidemics, and magic still reigned. A superficial order, condemned by its own victory. For while the Pax Romana was able to dominate nature, and subdue tribes and spirits, it sterilized the forces of life at the same time.

This is why the forces of life rose against it and Rome was swept away by barbarism from within and from without. The barbarian peoples launched the assault, while the Empire decomposed from within under the combined attacks of men and gods. The Empire was shattered and divided into numerous kingdoms and, later, into countless fiefs; the cities were largely abandoned and the encroaching forests erased the last traces of the Roman roads. The Middle Ages were a kind of return to nature; perhaps it was necessary for man, like Antaeus, to once again touch the Earth in order to derive from it the powers that would allow him to be victorious. And the Middle Ages, unlike Rome, were capable of progress because they were

Christian. Christianity, which, in order to adapt to the societies that it had won over, had become paganized, never ceased to bear within itself the principle of a desacralization of things: the scientific spirit. And despite the Church, the personal God called persons to freedom: to research, to initiative and to battle. This time the obscure vitality of barbarism would inspire the organization of the world.

As of old, progress began first of all with political organization: with the reconstruction of the State. The medieval kingdoms rediscovered the tradition of Rome: law, and administrative, financial and military techniques. While they ruled much smaller areas than the Empire, they were nonetheless capable of penetrating those areas much more deeply, right to the heart of the peoples, paving the way for the Nation-State. In association with the monarchs, the bourgeoisie, for its part, embarked on the conquest of the Earth. Separated from the cosmos by the walls of his city, the bourgeois, unlike the priest or the feudal lord, could only perceive the rest of the universe as a place to exploit. His Christian faith justified reason and revolt, restlessness and adventure, which combined with the older traits of the quests for power and profit. Thus, thanks to the kings and the bourgeoisie, the cities once again prospered. But this time they were animated by a spirit of freedom. And, just like the Greek cities in another era, they possessed an economic infrastructure. They were alive, and they were numerous; mutually hostile, the very forces that they employed to destroy one another caused them to grow. The small States would disappear, and were generally absorbed by larger and more efficiently organized States. And the Christian Middle Ages finally bore their fruit; science discovered its autonomy, man made an inventory of his planet and the first mechanical slaves began to engender other, increasingly more powerful and more docile, slaves. Under the impact of human intelligence and activity, the old ice was broken and set in motion, at an increasingly higher velocity. It took five centuries to advance from the stern-mounted rudder to the steamship; it would take a

little more than one century after that to invent the airplane; and half a century later the first satellites were launched into orbit around the Earth.

Today we have the world in our hands; but although we have learned how to exploit it, we do not know what to do with it. With respect to nature we can consider ourselves free, and without regrets, if we are capable of accepting the responsibilities that this freedom implies. We are no longer trapped in a remote wilderness, and the night no longer imprisons us under its impenetrable blanket. The old fears no longer haunt the thresholds of our houses, and the monsters that once populated the forests are now penned up in cages in our public parks for the amusement of our children. Only death is still present, and it is all the more disorienting insofar as from now on it shows its naked face. We can build enclosures for artificial seas,[2] and bombs that are more terrible than volcanoes; in the future we will change the climate. Man has become the most active natural force on Earth; before him, forests retreat and species disappear. We are no longer pagans; we no longer worship the rain, we make it. We no longer venerate the hippopotamus or the eagle; our tanks and our airplanes are much more impressive. The forces that we worship are called Steel, Crisis, Peace; all it would take is a tricolor poster on the walls of our cities to make the Earth tremble. Our cataclysms are Revolution and War; because it is no longer the soil that sustains us, but the body of the social titan. We are no longer pagans; but if being a pagan means that you worship idols, then we are pagans twice over, since our gods are made in the image and semblance of our tools.

We have vanquished nature. Therefore, we must learn to no longer view it as the enemy that we must annihilate. This victory was sometimes restrained, as in the rural world such as it existed in some old civilized countries. In Europe, in Asia, and in a few regions of Africa and America, man gradually submitted to nature, even as he subjugated it. And the rural landscape was born from this union, in which the fields and hedgerows follow the natural contours of the land, in which the valleys hosted farms and villages in the same places where the plants bore their fruits. The meadows penetrate the woods, and the woods intrude into the vineyards. And just as it is not possible to say where man begins and where nature ends in the rural landscape, it is impossible to distinguish the rural landscape from the countryside.

It is more common, however, for man to have only been able to defeat his old enemy by annihilating it. An increasingly larger part of humanity lives in cities where no trace of nature subsists, except the sky, or parks that are distinguished by their artificiality. The Earth is buried under concrete, the horizon closed off by walls. When night comes, a symphony of lights sparkles in the black diamond of the metropolis to enclose it in the heart of darkness, in a closed world that receives all of its life from machines, except the inexhaustible flow of men who endlessly come and go like robots. Because it is in man where life and nature still irreducibly subsist: in the anonymous crowd of the sidewalks, where love and death are still looking for their chosen ones. It is true: when nature is penned in to this extent, even this verbal phantom that stalks the tomb of the real will have disappeared.

4. Nature is man

And in fact, nature is man; it is just one of the names of his freedom. The feeling that we can have of nature is nothing but the consciousness of our life. All of man’s life is the expression of nature, nothing essential can be added to it: in the best case, artifice will only be able to camouflage a void. The blue sky shines over our heads, and the clear water flows through our hands; our hearts beat and our eyes open wide. What more can we ask? What is most beautiful and most intense about our existence, from the most simple to the most sublime, was invented by no one: new inventions, in the best cases, are nothing but new pretexts for old pleasures. Drink when you are thirsty and eat when you are hungry; step into the waves and catch a fish, have a few laughs with a friend or kiss your girlfriend’s eyes. Everything we can acquire is an added bonus, the essential things were given to us the day we were born. Nature…. We moderns are beginning to discover the meaning of this word, which awakens an irresistible nostalgia in us: in this defeated nature where death reigns, but which still bears the mark of the creator of Eden.

Man came from the dust; therefore, although he distinguishes himself from it, he is still part of creation. When we disturb nature, we are cutting our own flesh; in this domain as well we must exercise our freedom with fear and trembling. Our spirit is free, but our body binds us to the cosmos: in it burns the same fire that ignites the stars. And if the Earth is nothing amidst

infinity, man is small potatoes on Earth. All it would take is an imperceptible change in the salinity of the oceans, or a minuscule change in the impalpable atmosphere, for man to disappear like a breath of air. Man is only one form of living nature, which, for its part, is nothing but the result of a prodigious conjunction of all the forces of the universe. A supreme accident, a miracle. Thus, in this limitless expanse of nothingness, man is nothing; but if he becomes aware of his nullity, he discovers this nothingness in the center of infinity. And this is perhaps the most terrible thing about freedom: in that bright splendor that rends the night when we open our eyes. Man—and at this instant every one of us is this man—is situated at an equilibrium point at which all the nebulous tides converge to sustain him. On the scale of the cosmos, it would take very little to destroy him; and then the same terrible forces that cause the rose to bloom would reduce the planets to dust. But our weakness has become strong enough to threaten this equilibrium. Oppressed in the past by the natural order, will we be destroyed in the future by its destruction?

Such is nature, whose fragility is our fragility. If our actions become too powerful and are not attenuated by common sense, we risk bringing about our own physical destruction. And, in any event, we would destroy our freedom, which is even more fragile than life. Every blow that we deliver against nature affects our body, and therefore our spirit. This is why our impact on nature has a limit, since nature is precisely the mother from which man physically proceeds. Alas, Earth! Your master is your son.

The risk of physical destruction is still uncertain, but it is not insignificant. First of all, nothing guarantees that the increase of the population, associated with the endless increase of production, will not threaten us with an exhaustion of the planet’s resources: the modern experiment is too brief to predict the future. Reserves of oil and coal might be exhausted, in the best case scenario, within a few centuries: not even as long as an Empire lasts. And in some cases, there are already shortages of the most basic products, such as, for example, water for our big cities. Paris has to consider diverting some of the water of the Loire for its own needs; and New York, which consumes 25 cubic meters per second, must distill sea water at a very high cost. The use of atomic energy might allow us to compensate for the exhaustion of some of our resources, but this is only a possibility, and not at all certain. There are many cases in which it is likely that we will have to produce very expensive replacements for the goods that nature once provided us; and this at the price of a great deal of discipline and hard work.

The most elementary prudence would demand that, at the very least, we should address this question. All too often, when someone points out that we are exhausting the natural environment, the believers in progress will respond with a profession of faith: “We will find a solution.”

And if production continues to increase indefinitely, then another problem will arise: that of waste disposal. Under a sky contaminated by car exhaust, the Earth will become a place overflowing with garbage, with its rivers serving as sewers and the ocean being used as the universal dump. Above all, however, the powerful, and blind, intervention of man can end up destroying the fragile equilibrium that gave birth to him. We have not evolved much since the time when we worshipped the forces of nature. Confronted by nature, we have, at most, the attitude of a rebellious slave. Since it is no longer oppressing us, we no longer see it as anything but an instrument: the soil is only of interest with respect to its yield per hectare; the river, for its kilowatts, without our ever even suspecting that economic utility is a very limited aspect of the role that nature plays in our life. The most essential bonds that tie us to nature are invisible, because they are too numerous and too profound for our poor reason. The zeal for exploitation, and the lack of any sense of the gratuitous, could turn against us and even threaten profits. The preoccupation with productivity is too attached to the present, it does not sufficiently take the future into account; and then the day will come when productivity declines. Twenty years ago, nothing would have seemed more rational than to cut down the hedgerows and woodlots to allow the tractor to plow a straight line across the countryside. If someone were to oppose this, he would have been stigmatized as a reactionary. Since then, advances in agronomy and the terrible lessons of experience have taught us that as old-fashioned that patchwork of hedges, terraces and woodlots may have been, it was also wise. Had 19th century man been capable of doing so, he would have destroyed all the “varmints”, because he did not yet possess the expertise to realize how profoundly useful they are. Today, biology has shown us the role that predators play in the natural equilibrium, and fish farmers release pike into their fish ponds so that the carp will grow larger. The splendor of nature is not useless, it presents our senses with reasons that our minds have not yet been able to grasp. The blueness of the sky and the purity of the waters are not mere decorations on a stage set; in the transparent glance of a beautiful woman a terrible enigma shines: our relation with the cosmos.

In any case, however, we are sure that we are going to lose our freedom. Man’s freedom was once buried in nature, and now it is separated from it; but it still proceeds from nature. Now, when nature must be conquered and defended, anyone who says freedom, says nature: spontaneity. It is no longer within, but outside of our civilization. And our civilization itself will only bear living fruit if it penetrates deeply enough into us to become nature.

Knowledge frees us from natural determination; but it does not eliminate it. To the contrary, it is conscious of it and is based on it in order to help us counteract it. All it does is divert the weight of the physical environment to the pressure of the social organization; to a need that although no less brutal is less frightening, since it is manufactured by and for man. We cannot escape our condition, our fate no longer depends on the progress that turns its back on nature; it resides exclusively in a precarious equilibrium between nature and artifice, which must be maintained forever by the vigilance of consciousness.

Man is born from nature as from the body of a mother. Wherever nature has disappeared, modern society is obliged to manufacture a super-nature: the land and the forests, and even its animals and men. But then the law must be implacable, since it must reproduce nature even in the most subtle of its details. The Dutch girdle their dikes with artificial breakwaters that mimic the capricious contours of natural rocky shorelines. Russian and American agronomists break up the steppes and prairies with strips of woodlands and hedges planted with bushes: science invents the countryside. In the future, man will have to repopulate the seas the same way you might toss fish into a tank; with respect to some species threatened with extinction, governments have now reached agreements to carefully monitor them as if in a nursery. Since our power has grown to the scale of the Earth, it is the world that must be governed, even to its most remote confines and the most profound aspects of its complexity. But in this case man must impose upon his fellow man all the rigor of the order that the Creator imposed on him. The net of the law will have to be cast over every square inch of the planet’s surface. And in this new creation, the inhumanity of a totalitarian police state will replace that of an all-embracing nature.

There is no more nature, except in the heart of man, except in that growing feeling for nature that we find so pleasing in a certain kind of literature, when it is a vital instinct, a profound wisdom. For it is nothing but the intuition, intense but vague, of our connection with the universe.

Nature has been defeated, and this is why we are becoming aware of it. We have freed ourselves from it; what we have to do now is not only continue by going beyond nature, but also beyond progress. Our power must accept the limits that in other epochs were imposed by our weakness. In the past, we had to defend man’s position against the powers of nature; today, we have to defend the position of nature: we must respect the rules of its game, its mystery, when necessary. Then man will not only have broken his chains, he will have chosen to set things in order, and will have become the real king of the Earth: the lord of the universe as well as of himself.

II The City

1. The era of contradiction

For a long time, man’s struggle against nature was difficult and its outcome uncertain. Even when human victory seemed obvious, the past was not immediately abolished by the future. Nature subsisted alongside civilization and, above all, within man: within society and individuals. At least until the present generation, we were still peasants living in a technocratic era; the ethnologist who records the dances of the “primitives” is modern only because of his tape recorder and his cameras; he, too, participates in the myths and rituals of his tribe. And his consciousness, which is usually asleep, is not aware of them, no more than the Nambikwara are aware of their own myths and rituals.

Up until now, the contradiction between the future and the past has been manifested under the objective form of the opposition between the city and the countryside. This opposition, which is currently dissolving, reached its maximum intensity in France between the two World Wars. But as always in such cases, the men who lived through that transition thought that the situation was eternal, when it was nothing but a brief instant in the transformation of humanity as a whole. The progress of the cities seemed to be endless and the countryside, changeless: in a large part of Europe, at least, machinery did not really transform agriculture. The generations of that era lived on the frontier between two worlds; peasants who went to the capital, and urbanites who returned to the land of their fathers, benefited from both worlds, without being aware of it.

Thus, first of all, I will state that, until the acceleration of the economic and technological expansion that followed the Second World War, the citycountryside opposition, or the opposition between industrial society and traditional society, was more profound than the opposition between classes. If this has not been noticed by the theoreticians of society it was only because it was too obvious; too enormous and too simple, too concrete and therefore too complex to merit the attention of the experts. You would have had to have been a child to feel in one’s own flesh the clash of these two worlds whose frontlines then passed through the last stop on the streetcar line: where the walls ended and the fields began and you can walk on the grass. Two worlds in which space and time, and the density, and, consequently, the character of human relations, were no longer of the same nature; in which the ways of life and therefore of thought had nothing in common, except their opposition: in politics, for example, the contrast between the conservative inertia of the rural world and the progressive movement of the cities.

In the chapters that follow, some aspects of this contradiction, which are still being manifested, will be illustrated; for even when the things themselves have disappeared, they still live on in man. And it is advantageous to pause to consider this contradiction, since it is most fruitful for those who address it. It gives us an opportunity to look at two worlds instead of enclosing ourselves in only one; to shed light on the city from the perspective of the countryside, or on the countryside from that of the city; to therefore examine their vices and their virtues, which are simultaneously antithetical and complementary. An examination of this contradiction can serve an attempt to exercise freedom and to envision a society capable of synthesizing the countryside and the city without destroying either; capable, to the contrary, of instilling them with their full meaning. A society that would augment the virtues of the peasant by adding those of the city dweller, and augment those of the city dweller by adding those of the peasant. Surely, never before has a generation had the opportunity to live in two eras at the same time; just as no other generation has had the opportunity to reflect on this, and to decide. Unfortunately, in the man of those times of transition, neither the oldfashioned rustics nor the new urbanites were prepared to question themselves, and both lived right next to one another without ever noticing each other. In this way, the past is succeeded by a future that is equally blind and indifferent.

The man of the past, whom we find in the man of the future, denies the contradiction by saying that the countryside is changeless anyway. For city dwellers, the countryside is a kind of inexhaustible bank account from which they can tranquilly withdraw reaction, or progress. It is the reserve of open space, fresh air and clean water that is indispensable for the development of industry; for providing the energy and traditional virtues from which the factories derive their labor power and the barracks their infantrymen; the national park in which the man of the cities is sure of being able to enjoy, in total freedom, the pleasures of the old days. The capitalist bourgeois, who had hardly even begun selling a few tools or textile products to the peasants, had not yet undertaken the liquidation of the countryside; at least in France, he even contributed to its survival by means of agricultural price supports and protectionism, in order to interpose the inert masses of the peasants between him and the proletariat. Thus, against a green background, the cities can proliferate undisturbed. There is a whole bucolic literature, written by urbanites for urbanites, that nourishes the myth of the eternal countryside; everything can change, since nothing changes.[3] And when he goes on vacation, after leaving his house in the Sixteenth District, the bourgeois returns to the springs to reassure himself that they are still running just as clear.

In France, the countryside can therefore be a literary theme; it is not a social problem. Up until quite recently, the prestige of socialism and Marxism, characteristic of a rural nation that is still in the first stage of urban culture, that is, in that of ideology, reduced the social question to the opposition of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. And, in effect, this point of view is justified if one remains on the plane of intellectual and political expression: the point of view of the city. However, the conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat is itself proof of an antagonism that is taking place on a common level. Both belong to an urban society. They do not have the same standard of living, but they do have the same idea of life; and it is the bourgeoisie that provides the proletariat with the principles and models—the standards—of life. On the other hand, there have been bourgeois thinkers who have theoretically examined the class struggle: professor Karl Marx, among others; and the bourgeoisie has often contributed its management personnel to socialism. Marxism was the first tendency to emphasize the dialectical relation that unites capitalism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. The merciless struggle that characterizes their opposition must not make us forget the common features of these two poles of industrial society, which explains the mutual borrowings which have been taking place since the war. These two sides profess, in effect, the same religion of industry, and share the same battlefield: the city. For each, the countryside is a foreign body that it can somehow tolerate, while awaiting its chance to eliminate it violently by way of the revolution, or systematically by way of technology.

On the other hand, during this transitional era, the peasant is still living, for the most part, outside not only the ideas but also the economy of the bourgeoisie. The peasant is a proletarian if judged by certain aspects of his standard of living, but he is rich with respect to certain goods that even the bourgeois in the city lacks. The peasant is always conservative, regardless of how he votes: monarchist, radical or communist. An embryonic political science, which does not know which of its urban categories he should be included in, tosses him into that box of odds and ends called the “middle classes”, thus assimilating him to white collar employees and civil servants; as if there is not a greater distance between a Gascon tenant farmer and a professor than there is between a professor and a factory foreman! The Marxist-Leninists, on the other hand, unabashedly assimilate the peasant and the worker and include him in that totality that constitutes “the people”; a confusion that exacted a high price from the revolution as well as from the peasants, and would clearly reveal the difficulty of integrating the latter in an industrial society. The peasant is not distinguished from the bourgeois because he has a higher or a lower standard of living, but because he has a different way of life; he is not opposed to the bourgeoisie, because he plays by other rules. And if a bourgeois finds it difficult to understand a proletarian, he would find it at least as difficult to understand a peasant. It is highly significant that the peasant class, in the Marxist sense of the term, that is, as an economic class that competes with the other classes in the industrial system, and which fights for power and for the improvement of its standard of living, was only constituted when the modernization of agriculture had already begun to liquidate the countryside: the peasant class was born when the peasantry was dying.

This fundamental characteristic of the city-countryside distinction, the distinction between the city-dweller and the inhabitant of the rural areas, is now beginning, with industrial progress, to flourish at the level of theory. Today we are aware of the fact that the distinction between developed and under-developed, that is, predominantly agricultural, peoples, may very well be fundamental. However, while the adjective “developed” designates a very concrete society, that is, industrial society, the adjective “under-developed” embraces in a confused way everything that is not industrial society: from the pygmy hunter-gatherer to the Chinese coolie and the Alsatian farmer. Nullified at the national level, the contradiction is manifested on the world scale. Africa, South America and Asia are becoming the gardens for a Europe and a North America that are undergoing the process of urbanization. And we find between these two kinds of societies the same ambiguous relation of aid and exploitation, of scorn and admiration, that has always existed between the bourgeoisie and the peasants in the countryside. And in their poverty, the under-developed countries are also the last reserves of that wealth that industrialization has destroyed everywhere else: reserves of raw materials, reserves of water and space; and reserves of nature, especially human nature. And tourists from the continental cities travel to admire the wild animals and the traditional festivals of the rural people. Not for long, of course; for the rural world, whose increasingly more fragile social structure is confronting an increasingly more powerful urban society, is decomposing at an accelerating rate. The under-developed world is becoming a suburb: a residential suburb in the case of Polynesia and, above all, an industrial zone in which the shantytowns precede the factories. When the city—sociology—discovered the countryside, the end of the latter was at hand. Surveys and questionnaires for the peasants followed the invasion of the tractors, and pitchforks and harnesses have begun to adorn museums and lobbies instead of hanging in stables. The heir of bucolic literature, rural sociology plays the same role that ethnology plays with respect to primitive peoples. It performs the last rites, or an autopsy.

2. From the city to the urban agglomeration

The city always embedded man in an apparently closed world, separate from nature. However, the ancient city is distinguished from the modern city not only by a difference of scale, but also by a qualitative difference. The ancient cities were much less numerous and much smaller than ours. In 1939, there were already more than fifty urban agglomerations with more than a million inhabitants, whereas Bruges—the medieval New York City— barely had sixty thousand. They lacked technological means: a monster like Rome, fed by the imperial administration, was at the mercy of a delayed fleet. Men could associate with one another, crowd together behind walls to assure themselves that there were neither wild animals nor death, but this did not obviate the fact that the city was still besieged by the cosmos. Hence that energy, that aggressiveness, that was characteristic of the bourgeoisie; they had to go on the offensive in order to defend themselves. Our cities, on the other hand, dominate the surrounding area. They are authentic centers:

economic and administrative centers, centers where the threads of a network of highways and railroads meet, centers of financial relations and laws that shackle their subjugated surroundings. Now it is the countryside that is besieged by the city; and since it lacks walls and the will to defend itself, the rising urban tide will soon overwhelm it.

The ancient cities were lost in the midst of nature. In the winter, at night, the wolves would come and sniff around their gates and at dawn one heard the roosters crowing in their courtyards. But the main thing was that they were the products of human nature; they did not lead, but followed it. Associations sprang up spontaneously: the cities had their own life, sometimes they were independent, like the free cities or the medieval municipalities. Even when their function was to serve as the capital of a kingdom, like Paris, they aspired to freedom: to an autonomous existence and self-government.

This living unity was expressed in an organic style. The apparent disorder of the medieval cities (the Romantics’ “picturesque”) concealed a profound order that a map reveals. The labyrinth of alleyways inevitably converges on a central point, a castle, a cathedral or a royal plaza. In these cities, everything is spontaneous, yet necessary: just like the sinuous network of veins and arteries that flow to and from the heart. And the apparently disorderly torrent of men, work and festivals conceals necessary relations, full of meaning, between individuals and groups and things; or, in other words, a society. Later, when the West began to discover the disjunction between nature and the human spirit, the monarchs and the architects created cities that were adjusted to human reason—which for them was nature. They opened up broad avenues through the densely packed network of the old city; and where they could do so, they built administrative centers according to symmetrical plans: and this time it was not a god, but a king who was at the center of this geometry.

Until the 19th century, the cities grew just as a tree or a man grows; and each new expansion, new wall, or new ring of boulevards, delimited a larger form. Then, eventually, with the progress of industry, the cities exploded, creating a surrounding zone of construction projects and crowds of people, without any attempt to envelop them with a circle of roads or walls. The city engendered by the industrial revolution is no longer a finished product, or a work in progress, but a chaos. Its plan—one hesitates to use this term—is formless. It is an expanding cloud whose rate of growth exceeds that of man; it is no longer the expression of human deeds materialized in stone, but a kind of geological upheaval, a social earthquake, which neither human thought nor human action can now control.

And at the same time that the urban chaos was proliferating, so too, did the theories of urban planners. Phalansteries in response to the shacks of 1840; plans for the Paris of 2000 that serve to expiate the disorder of 1960. Perhaps urban planning arises when the city ceases to exist: not being able to live in it, we dream of it. And on the blank page, or on the terrain cleared by bulldozers and bombers, the geometric design of a Babel, whose towers rise up from amidst the trees, will take shape, realizing the synthesis of nature and progress. A shining city whose plan must be the matrix of the life we have dreamed of where men will immediately and willingly take up lodgings. For a long time, the city was an article of clothing that was gradually cut to the right measure; chaotic slum or ideal society, from now on the urban environment is becoming the Procrustean Bed to which men must adapt or disappear.

We are speaking of the city, but the city has changed. It is hard to continue to use that same word to refer to the cement disasters that have ended up swallowing various cities. The geographers propose the somewhat inelegant name of “conurbation”, while I prefer “urban agglomeration”; I think that the common language expresses much more accurately the cumulative nature of the phenomenon. After the primitive style, after the monarchist order, the disorder of the individualist period—while awaiting the monolithic beehive of a totalitarian collective. The urban agglomeration is no longer the product of either human nature or human reason. Let us take a look at the map of a big European city. In the center, a dense nucleus crowded around a major landmark; then, contained by the innermost ring of boulevards, the modern city. Beyond that, a built-up zone that spreads in every direction into the countryside. The arrangement of the tentacles of the new districts irremediably recalls the infiltration of cancerous tendrils throughout the circulatory or nervous system. An animated map that would retrace the evolution of the city would show us how buildings accumulated in increasingly more compact layers along the transport routes: highways, railroads and canals. And where these routes converge—train stations, factories, docks—the built-up strip becomes more dense; sometimes squeezed between a hill and a river, the built-up surface merges into a more compact mass. And around the central mass, the urban fabric decomposes into residential areas and industrial zones, forming around the urban agglomeration a dismal ring characterized by the outbreak of a scattering of satellite agglomerations.

The continent proliferates: but it has no contents. The outskirts are nothing but a built-up void: a refuge for men or machines. It is nothing but a bloated extension of the city, lacking a center and a life of its own, or market districts, palaces or theaters, and hardly more than a bar or two where the seed of an embryonic social life can begin to germinate. And because it lacks a center, it lacks relations; when a suburb wants to merge with another suburb, its proposal must be approved by the city. To live, to conspire, to pray, you have to return to the past and return to the heart of the old city. The suburb can be a swarm of persons, but it is only alive when they leave it, in the morning and then again in the evening, to go to the city. As soon as night falls, however, the streets are rapidly deserted. Then the outskirts of the city are nothing but a desert, where dangerous wild beasts prowl.

Up until now the cities were societies; hence their style and their limits, which they could not exceed without forfeiting their reasons to exist. The urban agglomeration, however, grows mechanically. The expression of political progress, and especially economic progress, it grows at a constantly increasing rate, as if in free fall under the sway of natural forces. Even on the map it seems to be in motion, and this impression of proliferation that is conveyed by the map is the image of its profound reality: once unleashed, the process grows like an avalanche. Man is added to man, house to house, undifferentiated unity to undifferentiated unity to form the mass. The agglomeration has no form, no limits and no style; it develops, so it would seem, in a disorderly way, and in its immensity it conveys an overwhelming impression of anarchy. In reality, however, it obeys implacable determinations: real estate prices and access to transportation, which are more strictly necessary than the sacred perimeter that once fixed the form of the city, since they are of a material and economic order. The city is a fait accompli, the gods can no longer do anything about it; men, even less.

The urban agglomeration…. For the spirit, an indistinct blur; and for man, an oppressive weight, in that place where the strongest determinations in the universe reign.

3. The suburb

The city, or rather whatever took the place of the city, is expanding.

Transforming the fields into vacant wastelands, and the vacant wastelands into lots, and the lots into an apartment complex. By surrounding the farm with a network of bungalows, the developer deprives it of its reason to exist before making it disappear; by transforming the countryside into a garden, the forest into a park, the hedgerow into a concrete wall, the riverbank into a pier; transforming the pond into a dump before converting it into an inground swimming pool. Throughout the countryside, beyond the last stops on the streetcar lines and bus routes, various broken down old houses of the “My Refuge” and “Villa María” type are scattered here and there. Like those watercourses that, following subterranean passages, suddenly rise to the surface far from their points of origin, in an enormous area where the expansion of its outskirts is being planned, the city destroys the countryside, transforming the peasant into a civil servant or a worker, and the servant into a slave; the council hall into a dance hall, the local inn into a hotel. By cutting off the rural path with a wall; by posting the verges of the forest with rude notices of suburban ownership. And by the time the first big construction projects are finished and the first sewers are built, the countryside is already destroyed from within.

The suburb is undefinable. It is not quite a city, but it is not the countryside, either. It is a countryside whose natural order has been destroyed and a city whose monumental order has not yet been constructed. The inorganic aspect of the suburb is impressive when you compare its plan with that of the neighborhoods of the ancient city: it seems to be more relaxed—the buildings are constructed at a certain distance from each other—and more chaotically—its roads no longer obey a general plan and divide and go in any direction; they obey, unlike the streets of the ancient city, a centrifugal force; it is no longer the harmony of order, but the blind rush forward of an elemental force. When one crosses the suburb on foot, the impression of monotonous confusion reaches paroxysm. It is, first of all—and this is what generally strikes the explorer—the manifestation of misery: the suburbdump. The pond, which in other places is covered by water lilies, is here covered by a suspiciously iridescent film, it is full of gases that burst from bubbles when you stir the water with a stick; the waste ground is covered with bottles, jars, mattress springs, toothless forks, that industrial decomposition that our civilization leaves in its wake, fertilized with tires and rags in every stage of decomposition, from humus to almost edible carrion. The unhealthy suburb, more unhealthy than the equatorial jungle; the greasy soil of its hills fertilizes dense thickets, less dense, however, than the iridescent waters of the river, whose current slowly drags mountains of bloated, livid dead fish that epidemics cause to float downstream in enormous quantities. The dead fish take on a rosy coloring, like a sentimental whore. This suburb that was once elegant, whose rococo luxury ended up rotting in the damp shadow of hundred-year-old chestnut trees. The whole zone is a swamp into which all kinds of junk is tossed: the broken bottle, the car without wheels, the unemployed worker or the off-duty prostitute, the Bolivian cabinet minister who ended up becoming an alcoholic. A world defeated, busy picking through the mountain of garbage to snatch some scrap of flesh from the bones of misery. A humanity that has hardly risen above the level of the ground, except at the crossroads where the solid edifice of the bar rises, the place for encounters and escape. The suburb of shantytowns made of cardboard boxes or oil drums, built with all the wastes vomited up by the city. The suburb that the city wants to forget, which its motorists cross as fast as they can by the most direct roads so they do not notice it.

Just as the castle rises above the hovel of the serf, the silhouette of the factory rises above the asbestos roofs and the rags hung out to dry in the sun. The silent misery is broken by the whistle of trains, the hum of the trucks, the strident or serious rhythm of the running machinery, which spreads throughout the whole zone, the industrial outskirts. The intensity of its force gives it its own style and its own reasons. There is a grandiose desperation in the industrial outskirts, characteristic of a Babylonian enterprise; the gigantic laboratory of an alchemist where, in a labyrinth of steel tubes, chains and hooks, among clouds of smoke, in towers of bronze in which a secret fire burns, the magic spells are cast that allow men to dominate the world. There, all uncertainty dissolves: forces as implacable as they are precise do what must be done; they forge effective machines and a hard proletariat. One would have to be blind not to see that what is made there is not the mediocre comforts of insignificant individuals, but a collective effort that defies the universe. It is the cave where the thunder and lightning of world wars is forged.

The tragic element of the industrial suburb is salutary; unless one is the victim of a particular esthetic, it is impossible not to see that its scale is no longer human. It towers above us, bellowing its challenge. Perhaps this is why the bourgeois who is coming home from his house in the country drives as quickly as possible through this upside down version—this hell— profoundly repressed, of the city. Here we find ourselves face to face with our origin and our destiny; when the cobblestones gleam under the downpour, when the wind picks up and dispels the smoke that pours out of the smokestacks, the air that one breathes is the same as in the lost places of the mountain peaks and the headlands of the sea: we stand before an abyss that man will never be able to penetrate. Such as the cosmos might have looked like at the dawn of time.

If we want to gauge the scale of the beings who frequent these cyclopean constructions, we must refer to the residential suburb. Behind the grandiose edifice of the economy, the misery of individuals; behind the materialized audacity, the interminable extension of horizontal mediocrity. The suburb to which one returns at night while reading the newspaper, the suburb of relaxation and spiritual emptiness; the suburb where one sleeps, and where one daydreams in the eternal return of the everyday routine. The suburb without monuments and without history. Why talk about it? We know these people, we live in these houses—how can we recount the tale of nothingness? The residential suburb prior to the “social housing complexes”. A report on the amorphousness of the city. Anyone who has seen ten meters of its streets has already seen the kilometers and kilometers through which the labyrinth winds: no Ariadne’s Thread will allow you to escape from it. Anyone who has seen ten of its inhabitants has already seen the millions of others who populate it. A city? No, an immense scattering of cheap buildings where, now and then, one can make out the simulacrum of a focal point: a café, a grocery store, a hardware store, a movie theater. The corner store is a subsidiary of Potin;[4] the movie theater, a subsidiary of Paramount, where the inhabitant of the outskirts of the city can find, for a somewhat lower price although only after some delay, the same entertainments that are provided downtown; this is what the people of the outskirts call “living in Paris”. Surely, this explains the atmosphere of vacuity and superficiality of the outskirts of the city; these neighborhoods populated by tens of thousands of inhabitants have less of a life of their own than any mountain village. The residential suburb is the realm of mere dormitories.

No order rules over the disposition of these thousands of single-family houses except possibly the allure of the street. Each homeowner has built his house and decorated it in accordance with his own fantasy. Wrought iron fences and walls embedded with broken glass protect these fortresses of French individualism. Yet, if we follow these endless roads, we are rapidly submerged in an ocean of monotony, as if this multitude of particular details pertaining to each individual were nothing but a vast accumulation of grains of sand. Little by little, this embittered individualism reveals the same basis: the green doghouse, the miniature garden so that each homeowner can take advantage of even the smallest scrap of land, a solitary lettuce protected by the whole family against a single slug; the tree pruned with extreme care, so that the neighbor cannot gather its fruit and because one must comply with the municipal regulations; and also because you have to have something to do on Sundays, and because here the passion to do something on the part of an idle humanity can only be consummated on a few square meters where everything is raked, neat, trimmed and polished; and as for the ground, every centimeter counts, because you had to pay for every centimeter. The soil harassed by this feverish activity is sometimes compressed as hard as cement under the weight of the daily traffic, and its entire surface has been covered with a layer of sterile gravel: a domestic desert, a reflection of the interior world of its owners, who pursue here the vocation of generations of peasant-plowmen. Sometimes, eccentricity and grandiose airs: a gleaming glass ball, an exotic palm tree or a zinc awning, since an awning ennobles its owner. Nowhere do you find a single completed building that has its own dimensions; everywhere you see imitations, imitations and imitations…. And then we come across the false turret, the Chinese-style fish pond, the proliferation of a conventional style of baroque.