Claude Gabriel

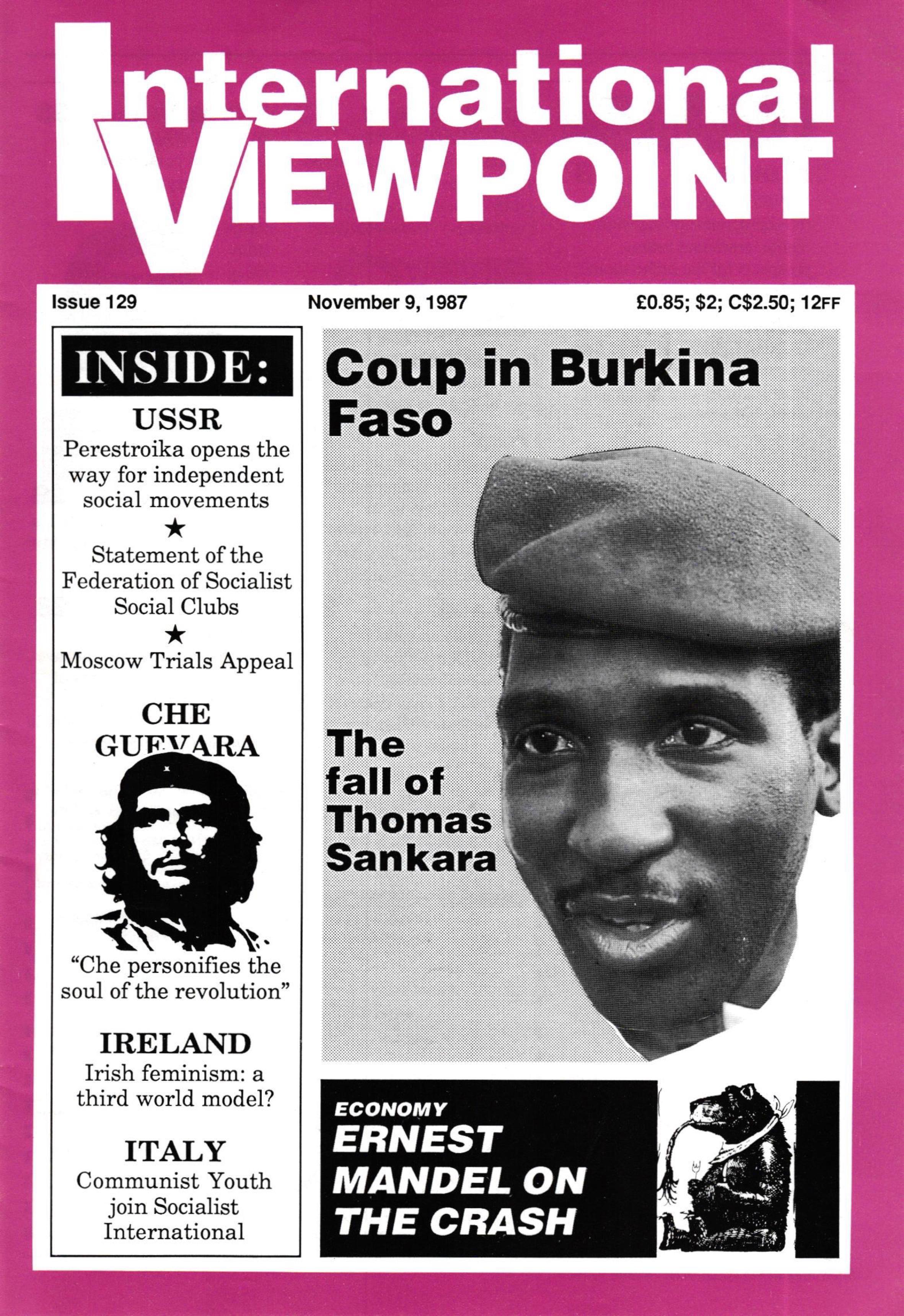

Thomas Sankara killed in coup d’etat

Democratic and national reforms

Social base for the revolution

Differences between town and country

Four years after the revolution, Captain Thomas Sankara was killed on Octobe l5 during a putsch led by his main collaborator, Captain Blaise Compaoré. The coup d'etat resulted from a conflict between factions in the army, and does not seem to have involved any section of the population.

On the contrary, as soon as Sankara's death was announced many thousands went to his grave. Utter confusion seems to have hit all the militant layers involved in political action over these last years.

An official communique announced, “sincere revolutionaries, foiling a plot and at the same time preventing our people from being plunged into an unnecessary bloodbath, have decided to assume their historic responsibilities and act.” According to the instigators of the coup, Sankara would not accept being in a minority in the leadership. He planned to ban independent parties and unions and set up a single party. The coup instigators made it clear that, for them, the action was necessary to put an end to methods that reflected “eccentricity and immaturity”.

Coming as the culmination of the differences inside the leadership team and a settling of scores, Thomas Sankara’s demise shows the limitations of the political process that has been underway in Burkina for four years. His sudden execution illustrates very well the gulf that existed between the real power and the masses, in spite of the honest efforts by a section of die leadership team.

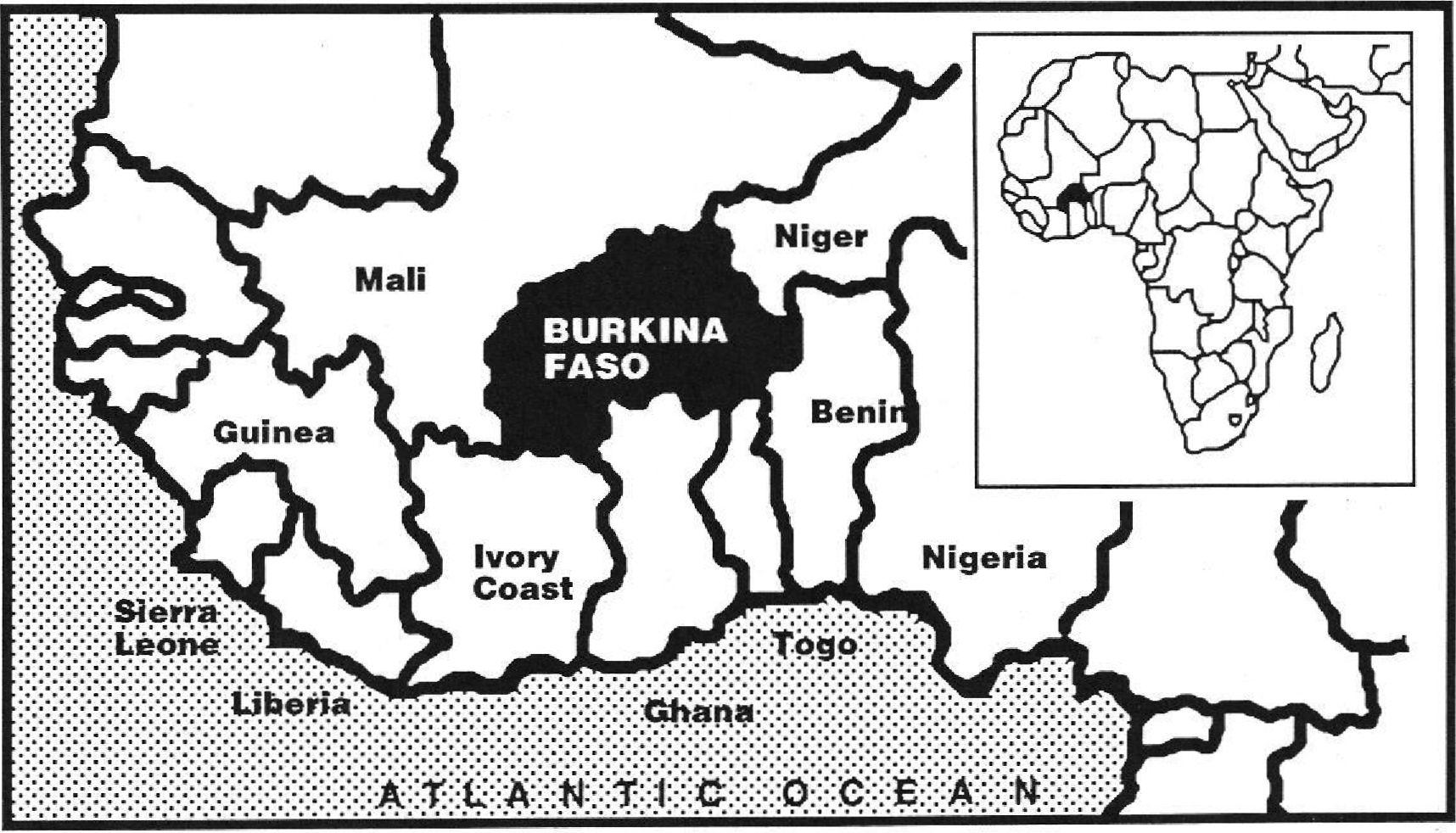

Burkina Faso (previously Upper Volta) gained independence from France 27 years ago. The Burkinabe revolution began on August 4, 1983, when Thomas Sankara took power at the head of a “National Revolutionary Council”. Prime minister in the Ouedraogo regime, he had been imprisoned in May 1983 for “plotting”. Two months later, an uprising at the Po parachute base led by Blaise Compaoré put an end to the regime and freed Sankara.

The National Revolutionary Council was proclaimed, basing itself on denouncing corruption and neo-colonial submission. Very quickly, the government benefited from Sankara’s charisma — he alone came personify the revolution. This personalization of the government can be explained by the leading group’s fragility and its weakness.

A strong personality

But Sankara also symbolized “the new man”, a goal for all to reach in order to get the country out of its crisis. The battle for development was often presented as dependent on a massive redemption of the society, in which everyone was to keep their patch clean. For example, the appeal to spread sport to all workplaces reflects this view of the revolution as a purifier.

At an international level, Sankara astonished everyone by his simple language and fair judgements. It was this personality, somewhat unusual among African leaders, that made such a strong impression among the young people of West Africa.

Over and above Sankara’s personality, the revolution aroused enthusiasm and sympathy among all anti-imperialist layers. The complexity of, and doubts about, the political process itself could take nothing away from the desire to see this little country succeed in the face of imperialist pressures. But while the specificities of the Burkina case must be pointed out, its similarities with all the other “progressive” or “Marxist-Leninist” regimes in Black Africa also have to be understood.

The first, or underlying similarity, we might say, is the socio-economic backwardness of these states. This backwardness greatly limits the possibilities for revolutionary developments on a regional scale.

Africa today is not the same as Latin America, the Middle East or Asia. Particularly in West Africa, there has not been any political regional interrelationship that could substantially break down the compartmentalization of each country, and which could open the way for international political developments operating to reduce unevenesses.

Such a backwardness also restricts the development of the class consciousness of a still tiny industrial proletariat and, owing to the lack of a real collective consciousness, the possibilities for a peasant revolt. Sankara spoke of “the inexistence of a conscious working class...and, consequently, of an organized working class”.

Dependence on French aid

At the same time, this backwardness finds its reflection in weak ruling classes, tom apart by regional and ethnic interests and rotten with corruption. Finally, it also resulted in Burkina in a state apparatus largely dependant for its everyday functioning on French aid (40% of the current budget), and on imperialist programs. Here we find the ultimate expression of combined and uneven development in the internal structure of the state itself.

In this context, the revolutionary antiimperialist project came up against a number of big problems: What sort of mass mobilization could be counted on, and which layers or social classes would really be able to serve as the backbone a revolutionary process?

The “revolution” here was not conducted by a progressive bourgeoisie anxious to put an end to national oppression and the vestiges of the old society. Nor was it conducted by an embryonic proletariat expressing its initial radicalization on democratic and anti-imperialist issues.

Contrary to what Sankara wrote, the mass demonstrations of May 20 to May 22, 1983, (after he was arrested) did not “help to reveal the sharpening class contradictions of the Upper Volta society”. Progressives in the military, in concert with a certain number of left groups, seized opportunity to carry out a coup d’etat. But this “revolution” was organized from above, in the very limited spheres of young officers and intellectuals.

The new regime based itself on some sectors of classes. But no real revolutionary social bloc had been systematically built up for struggle. It was a “revolution” without class candidates for power. Therefore, within it all sorts of social substitutes for a real ruling class were to compete and be telescoped together.

One of the paradoxes is that although the “democratic revolution” was installed by a military putsch, it had a leadership influenced by Marxist-Leninist conceptions. This gap between objective reality and the ruling ideology can only be explained by the backwardness of the social formation in a capitalist-dominated environment

The Sankara regime stretched itself severely to try to reconcile the needs of struggling against under-development in a socially backward country with the need for a Marxist interpretation of the world corresponding to the international reality of capitalist development.

National, popular revolution

The revolution’s leaders claimed to be inspired by the theory of a national popular revolution. To follow the threads of this position it is not enough simply to retrace it to Stalinist position or Maoist writings. It is necessary above all to refer back to the Byzantine debates of African students from France’s ex-colonies in the 1960s and 1970s. All these discussions have to be placed in the context of the debates between Maoist and pro-Soviet currents in the Federation of Black African Students in France (FEANF), and the particular social and political frameworks of these currents.

Thomas Sankara added a personal touch to this theory. Above all, unlike most of the principals in these debates, he tried in practice consciously and firmly to cany the position to its logical conclusion. The difference between the African students’ obscure and confused debates in the 1970s and Sankara’s regime is that the latter dropped some of the formal rhetoric in order to follow a more pragmatic path.[1] Moreover, in this respect, Burkina differentiated itself from the “Marxist-Leninist” regimes in Benin or the Congo — or even from that in Ghana — where, for a very long time, Marxist verbiage has covered up a total abdication in the face of neocolonial pressures.

Sankara’s militant empiricism was reflected in simple language, rather agreeable for those who cannot stand the “progressive” African regimes’ pompous professions of faith. It was this empiricism that allowed him to develop a lucid analysis of the situation of his country in Black Africa.

In such a context, the national and popular revolutionary project was designed to be realist. The Burkina “revolution” in August, 1983, was only possible because of the extreme fragility of the state, a state at the hub of many modes of production but which, in reality, was dispossessed from regulating the dominant capitalist relations by France and foreign companies.

Once in power — that is, once the “revolution from above” had been accomplished — Sankara’s team was confronted by the problem of “how to trigger” the revolution at the base. The state apparatus was unchanged. Some of its cogs could be reformed, but its functions would stay the same, until alternative social relations appeared in the villages and countryside. Therefore the destruction of this apparatus had to be the next step after the military take-over.

Even if “democratic and popular”, the revolution had to take up the question of the state apparatus and its army. However the army was not turned upside down after August 4, 1983. It was purged, and then surrounded by the Revolutionary Defence Committees (CDRs). But it remained a 6,000-strong force of which only commander and government had been changed. The problem is well-illustrated by the way in which Sankara was overthrown, and the apparently “praetorian” character of the debate and its tragic culmination.

So the new regime ran up against its own contradictions. It came to power with a revolutionary project without having first built a mass movement, without having organized the labouring classes and without having united a conscious vanguard. There was no class candidate for power, nor a party!

Democratic and national reforms

Manipulating words could not in itself resolve the difficulty through putting the conventional label of “national-democratic revolution” on something that looked like a revolution, but in reality did not have the social base for carrying one through. Realism first of all called for democratic and national reforms. But isn’t utopianism precisely trying to make a revolution, of whatever kind, without a potential ruling class?

For some months, there has been a certain readiness among the people for action. The struggle against corruption, the development project, the denunciation of imperialism and the appeals for steps towards women’s liberation opened the way for the beginning of a social mobilization. But this process had to be speeded up and to the Burkinabé people had to be roused.

Social base for the revolution

The creation of the CDRs fitted in with such a scheme. Initially, this was based on a spontaneous growth of social activism, but the formation of these committees reflected a fundamentally voluntarist project over the long term. Very quickly, too quickly for the equilibrium of the regime itself, the CDRs took on at the same time the tasks of grouping an vanguard and forming a broad social base for the revolution.

Besides tendencies towards bureaucratization and careerism that developed as a result, a feeling arose in the CDRs that all layers in society were holding back from commitment to the revolutionary project — the wage-earners who had a standard of living much higher than that of the peasants; the petty-bourgeoisie worried about their incomes; and even the small peasants, who clung to their way of living and their prejudices. Here, authoritarianism gets the upper hand over persuasion. A society paralyzed by conservatism has to be given a shove.

Jean Zeigler (a Swiss sociologist, and member of the executive of the Socialist International) wrote the following about this problem: “The CDRs are rather unreliable and fragile instruments. I don’t criticize Sankara’s strategic choice. After 1983, he probably didn’t have any other option than to confront the traditional powers, and obviously no other choice than to resist the attempts of this or that left party or trade-union organization to impose their hegemony.”

“A partially useless weapon”

“But the weapon that he forged to implement his strategy seems to me, I repeat, a weapon that is partially useless. The CDRs are composed mainly of young people, who are linked to Sankara by spontaneous enthusiasm. But how can the CDRs be controlled? Their exactions are numerous, their organization fragile, their leadership rudimentary and their ideological education often non-existent.”[2]

This raises a discussion about what social forces you could base yourself on in such a situation. When the military took power in 1983, no alliance of the toiling classes had been brought about through a convergence of struggles for concrete demands. The “workers’ and farmers’ ” alliance that was objectively necessary had not appeared at all in practice, even in an incipient way. There was no external danger threatening the national territory and unifying popular resistance. There was no civil war against the former ruling classes, the former “landed chiefs” and the speculators. In these conditions how could the toiling classes be galvanized and their revolutionary unity realized?

In the absence of strong prior mobilizations, it was therefore after the taking of power that the decision had to be taken on what social layers or classes the regime would base itself, and how they could be mobilized.

At this point two historical processes became juxtaposed. First that of the military coup d’etat and the appearance of the CDRs; and second the development long before that of small pro-Soviet or Maoist left-wing groups, based in the towns on a series of trade unions, among teachers, civil and public servants.

This trade unionism had both the virtues and the vices of the political currents that inspired it. It supported a certain number of traditional demands relating to wages and jobs, but had no credible political project for the country. But in Burkina, where the majority of the population is rural and outside the classical wage-earning sector, should these layers of wage-earners be considered as a conservative, or indeed, as a counter-revolutionary labour aristocracy? Should the trade-union leaderships be regarded as a brake on the revolutionary project?

Thomas Sankara was visibly tempted to draw such a conclusion. Would not the real African proletariat be the peasants, because in general they are the only producers of wealth in the country?

This is an old discussion, which goes back to Franz Fanon. But it took off again in the 1970s with the growth of studies on the town/country relationship. The pauperization of the rural zones, the crisis of the peasantry and the fall of agricultural productivity revealed the wildly unequal exchange between town and country in Africa. It was only a step from taking note of this to viewing all the urban layers as exploiters of the peasantry, in the strict sense, and certain African specialists took it.

In his speech of October 2, 1983, Sankara gave a much too classical and dogmatic analysis of African society: “The Upper Volta working class, which is young and not very numerous, but which has been able to prove through its incessant struggle against the bosses that it is a really revolutionary class”, and “the Upper Volta peasantry, which is linked to small production and embodies bourgeois production relations.”

Differences between town and country

But in 1986, his position had definitely changed, and contained a more precise social project: “The poverty surrounding the towns brings out the difference that exists between town and country. This is true to such an extent that we in the towns run the risk of experiencing the fate of those who have the nerve to sit down at a well-laid table in front of starving spectators. These spectators one day could well mount an assault on this table and this injustice.”

Moreover, on the civil servants, he made a what amounted to a speech for the prosecution: “The national budget devotes 60% of its resources to paying civil servants, and they represent 0.035% of the population. And to them, and their like, we devote more than 60% of the national budget. Although it is difficult to maintain a standard of living in the towns that would enable us to chase after more and more the European or other mother countries that we have known, it is possible to build basic health centres for the peasants. With this approach we could build a new society.”

Asked about the project of equalizing wages, he replied: “It is incontestable that hundreds, if not thousands of our people have been severely hit, in the sense that the privileges that they have been used to for a long time have been withdrawn.”[3]

In any case, Sankara’s dilemma could only lead to terrible disillusionment. In the specific conditions of the Burkina “revolution”, how could one get out from under the pressure of the urban layers and go looking for a peasant mobilization? The “democratic, popular revolution” could not become a simple revolution of the impoverished, a revolution of the “wretched of the earth”, pulling urban wage-earners along behind. All the more in revolution made from above, it is very difficult to create and maintain a peasant mobilization.

Decisive social questions

In other words, despite the demographic and economic weight of the countryside, the political relationship of forces and the decisive social questions continued to be determined by the urban areas. Failing to master the socio-political relations governing the life of the towns meant ending up very quickly in crisis and disorder. Sankara paid for that failure with his life.

The problem of keeping a grip on sociopolitical relations in the towns was all the more important because there were a certain number of small political “Marxist” organizations in Burkina. The main one was the Patriotic League for Development (LIPAD, pro-Soviet). There were other other pro-Chinese, pro-Albanian groups, and so on.[4]

Coming out of the student debates in the 1960s and 1970s, these groups essentially existed in the towns. They themselves had no other strategic project in the long-term than the same reference point of a national and democratic revolution. Their respective divergences were over what such a revolution would involve and where it should set its sights internationally. Sankara and his friends evidently mixed with these militants and groups over a long time, and some of them came from these circles.

Shackles of neo-colonialism

Before the advent of Sankara, Burkina was one of those rare African countries where — in spite of the authoritarian shackles of neo-colonialism and military governments — a multi-party system was maintained officially or de facto. The new regime had to incorporate this heritage into its own project, which it did partly by including specifically the LIPAD and the Union of Communist Struggles (ULC) in the government. But inasmuch as these small left parties had no national perspective, Sankara’s politics appeared definitively more audacious than theirs.

However, very quickly coexistence with the LIPAD became difficult, leading to the departure of its ministers. The problems arose in particular because Sankara’s projects sometimes collided with the interests of the base of these groups.[5]

Sense of proportion and prudence

Sankara however had a sense of proportion and of prudence. He had the intelligence to understand that his country could not afford the sort of grandiose formulas we have become used to hearing from other African regimes. He was anxious to avoid just producing rhetoric for domestic use by the leading strata. And he quite explicitly drew a balance sheet of other “sister” regimes. Recognizing the error of trying to build monumental industrial projects on the Soviet model in countries like Angola, Madagascar and Benin, he explained that: “the National Revolutionary Council will not delude itself with gigantic, sophisticated projects.”

Conscious that he needed of a stable political base, he preferred for a time to back a multi-party system, rather than rush headlong, like others in Ethiopia, Angola or Mozambique into proclaiming the “proletarian party”:

“In the future, a party may see the light of day, but we cannot focus our thoughts and our preoccupations on the notion of the party. There would be a danger in doing that. [In that case] the party might be formed to pay homage to revolutionary principles (‘a revolution without a party has no future’), or it might be set up in order to meet a sine qua non precondition for joining one International or another....The condition [for forming the party] will be that the party play its role as leader, guide, as an vanguard element. It must lead the entire revolution, be rooted in the masses and, to this end, the elements making it up must be serious. They must be elements who hold sway, who can convince people unambiguously by their example. But a prior condition for building such a party is that people struggle without a party, forge their tools without a party. If not, we will fall into the nomenklatura system.”[6]

But, nevertheless, the regime did not avoid “leftism”. Sankara wanted to steer a course between Scylla and Charybdis: neither to seek to construct a utopian revolutionary party, nor to adapt to the pressures of the old society. The instrument that he thought adequate for this difficult navigation was the CDRs, which were at once “authentic people’s organizations in the exercise of revolutionary power” and “assault battalions” (speech on October 2, 1983). These Committees symbolized the voluntarist character of the Burkina “revolution”. To this extent, they were able to accomplish tasks that the public administration by itself was incapable of assuming. That was true for the literacy campaign and above all for the “commando squads” for vaccinating children.

But the CDRs did base not themselves on a big popular mobilization; little by little they came to substitute for it. That is why over the past two years, as some CDR leaders themselves admitted, conflicts multiplied over the past two years between the CDRs and public service workers, and between the CDRs and some sectors of the population.

The national conference of the CDRs, which was held from March 31 to April 4, 1986, revealed these problems to a considerable extent, and the documents coming out of it were full of self-criticisms. Sensitive to this crisis of the CDRs and their revolutionary project, Sankara wrote in February 1986:

“In their economic, political, cultural, military and sporting activities — in brief, in every area — we have seen our CDRs engaged in a tough battle, sometimes with very little gratitude from people, even from those who have benefited from the CDRs actions”.[7]

The idea of the “democratic and popular revolution” by definition is supposed to be prudent and pragmatic, opposing all conceptions of a more radical revolution. But the problem is unhappily not between “realism” and “utopia”. Even if careful, the revolutionary project has to attack the roots of evil. How can this be done in a country where it appears quite difficult to give to Peter without taking from Paul, in a country where at the end of the day the subjective conditions for revolution could not be prepared?

Even realism becomes utopia

This is why Sankara’s fine-tuned thinking did not avoid the missteps, the “leftist” errors, if one wishes to refer here to the communist vocabulary. Conditions are such in Burkina that at certain times, even realism becomes utopia.

The agrarian reform of August 9, 1984, nationalized both the surface and what lay under it. But at the same time it eliminated the traditional system of “landed chiefs”, which amounted to taking on a project of overturning the whole social system in the countryside.[8]

Were the peasant masses ready for such changes of attitudes? Unquestionably, the answer is yes for a section of them during the first period. But in the longer term, in the absence of a real mobilization, the chiefs were to regain ideological and social control of the villages and families, and the affair would become much more difficult.

The first five-year plan explained that “the goal basically aimed at by the agrarian reform is to destroy the socio-economic fetters on production, to create a framework for production corresponding better to the conditions for real social advancement for the disinherited masses.” However, among these fetters was the traditional structure that placed women and “younger sons” in a position of subordination to the “elders”.

In a society like this, a revolution must also mean that women and “younger sons” take power. This revolution, an indispensable one, turned upside down the traditional circles, their lineage structure and their social hierarchies. It was at the same time a social and a cultural revolution. That indicates the difficult and long-drawn-out character of the process. Trying to speed things up could lead to terrible disappointments. But in order to succeed, it was necessary first to form a very extensive revolutionary movement including hundreds of cadres well implanted in their areas and able to gauge every day advances and setbacks in the peasants’ consciousness. Such a revolution cannot be conducted in the same way as the expropriating a big feudalist or seizing a big capitalist plantation! “Class struggle” in a village or within a clan is far more difficult to master.[9] Every African regime that has sought to “revolutionize” the countryside has broken its teeth on this obstacle!

Initial popular enthusiasm

In the towns also, the vigorousness of of the social measures did not fail to pose grave problems. Cutting rents and school fees, eliminating the head tax, actions in favor of public transport and social housing promoted an initial popular enthusiasm. But at the same time, in order to come up with the money, the government “retrenched,” retiring about 10 per cent of its functionaries, or 2,000 people.

Once it had saved a few billion CFA francs as a result of trials against corrupt and speculation, the regime called on wage earners and students directly to make a big financial contribution. It called on the better paid wage earners to give a month’s wages and to accept lower benefits. It called on students to contribute 2,5000 CFA francs a month. At the same time, taxes on merchants were increased.

On January 4, 1984, Sankara decided to suspend payment of residential and commercial rents to the owners and to have these sums turned over directly to the state. All this led to a certain disorder, discontent on the part of the wage earners and students, a loss of credibility among the petty bourgeoisie, a drop in general buying power.

“Main enemy left-wing reaction”

Confronting such discontent and resistance from the trade unions, the CDR of the Ouagadougou garrison demanded “extremely stiff penalties against all the renegades and their allies in the pay of imperialism.” On February 6, 1985, before an assembly of high-school students, Sankara explained that “the main enemy is not right-wing reaction but left-wing reaction.”[10]

But what was to most strain the alliances the government built up in the urban strata was the firing of hundreds of teachers who struck on March 20–21, 1984, demanding the release of two of their union leaders, who had been characterized as “counterrevolutionaries” by the CDRs. From that date on, relations between a Sankara and a part of the traditional left became conflict-ridden.

The break was to be consummated in recent months after the arrest on May 23, 1987, of Soumane Touré, the general secretary of the Burkinabé Trade-Union Confederation (CSB) and a member of LIPAD. It was his second arrest since 1983. The CDRs called for his execution, and LIPAD protested that the military were simply trying to “resolve contradictions by force.”

A trade-union common front had already taken May 1 as an occasion for denouncing the austerity, firings and restrictings of union rights. Numerous leaflets and united appeals were circulating, calling for the right to “commemorate May 1 in tranquility and independence.” On April 30 the army had occupied the Ouagadougou Labor Exchange, inviting the unionists to organize a rally under the government’s aegis. According to the unionists, the employment minister at the time characterized the union leaders as “outright feudalists,” “corrupt politicians,” and “bureaucrats.”[11]

On June 6, LIPAD published a statement arguing notably that “material and economic achievements can never be a justification for doing away with democratic freedoms or a substitute for them.” Thus, a very grave crisis existed in recent months in Sankara’s relations with his ‘natural allies.” Caught between the CDR and the unions, he was visibly looking for a way out, but he ran up against the contradictions of the “Burkinabé Revolution” itself.

Was it this risk of isolation that convinced Campaoré and the majority in the CNR to eliminate him? Over and above the personal quarrels and clique conflicts in the government, it seems that the real problem was what class alliances to build around the army. Could the revolution of the poor do without the unions and the urban wage earners? May not Thomas Sankara’s tragic end revive the debate on the unfinished revolutionary processes that have now become a well-known phenomenon in Black Africa? ★

[1] Some traces of these debates remain, notably in the reference to “democratic centralism” for the functioning of state bodies. Sankara said he was personally influenced by Che Guevara and the Nicaraguan Sandinistas.

[2] Un nouveau pouvoir africain, Editions Pierre-Marcel Favre, Paris, 1986.

[3] Interview in L’Autre Journal, March 26, 1986.

[4] A number of groups exist in Burkina. One is the LIPAD, which came from a pro-Soviet current in the African Independence Party (PAI). (There are still three factions of the PAI today in Senegal). There are also the Maoist, Pro-Albanian Union of Communist Struggles (ULC); the Assembly of Communist Officers (ROC); the Burkina Communist Union; the Upper Volta Revolutionary Communist Party.

Moreover, until now there have seemed to be possibilities for taking important independent initiatives, on the condition of positive identification with the government’s projects. An example is the Anti-Apartheid Committee that held the recent international conference on South Africa. A CDR was recently formed in this committee, indicating thereby that the Anti-Apartheid Committeee as a whole was not simply an appendage of regime.

[5] L’Humanité, the French Communist Party’s paper, wrote on August 21, 1984, about the CDRs: “An organization that recruits the worst and the best”. This was a way of supporting the LIPAD thesis whilst maintaining global support for the Sankara regime.

[6] Un nouveau pouvoir africain, ibid, pp.86–7.

[7] Lolowullen, the CDRs’ journal, February 28, 1986.

[8] Moro Naba, emperor of Mossi, at one time had his electricity cut off because he didn’t want to pay for it.

[9] In Lolowullen, ibid, an article on agrarian reform explained: “It is therefore a question of sparking off the class struggle between the peasants and feudal and backward forces. In fact, this form of class struggle seems now to be predominant in the countryside.”

[10] Le Monde, February 23, 1985. At the end of 1984, the regime — in spite of good official relations with Moscow — expelled the first advisor of the USSR embassy, accusing him of having too open relations with the LIPAD.

[11] Union front. Appeal dated May 18, 1987, and signed by nine unions. (Duplicated document).