Dale F. Eickelman

Ideological Change and Regional Cults

Maraboutism and Ties of “Closeness” in Western Morocco

This study presents an account of the main structure of the ties between the Sherqawi religious lodge (zawya) of western Morocco and its clientele, the idealogical base for the maintenance of these ties, and how both the actual ties and the values on which they are based have altered and, in turn, have been altered by changing historical and political contexts.[1] Through these topics I pursue a more general concern with the classic sociological theme of the interrelation between symbolic representations of the world and patterns of social conduct. In particular, I am concerned with maraboutism, a predominant (although not unique) version of Islam as locally received in Morocco. I argue that like most implicit ideologies (or in a sense that is explained shortly, a part-ideology), maraboutism is closely tied to basic Moroccan conceptions of the social order, notably the notion here translated as “closeness.” I further argue that such ideologies must be understood as socially maintained activities and related to specific historical contexts. I seek to place maraboutism in such a perspective and to indicate how this approach is more satisfactory than alternative ones which treat maraboutism as analytically “timeless” or which posit a stable interrelation between the realms of ideology and social action.

Ideologies and the Social Order

Because the relation between symbolic representations of the social order and patterns of social conduct is such an enduring sociological problem, I think it useful to indicate what I regard as the shortcomings of certain earlier approaches. An older academic tradition asserted a correspondence between the two realms without regarding the exact nature of their interrelation as problematic. Thus Robertson Smith (1919) related successive modifications in the messages of Old Testament prophets to the specific historical circumstances in which they originated. Smith clearly perceived both social changes and inconsistencies in the prophetic ideologies, yet regarded Victorian notions of progress and Christian assumptions about the gradual enlightenment of mankind as sufficient to account for them (Beidelman 1974: 38). Similarly, the “simple” societies that Durkheim and his collaborators chose to investigate allowed them to presume an elegant one-to-one correlation between ideology and social action (Durkheim 1915; Mauss 1966; see also Evans-Pritchard 1940). Edward Shils is a contemporary representative of the “correspondence” tradition to the extent that he regards the core symbols, values, and beliefs of a society as concretely represented by such physical manifestations as capitols, cult centres, and social and political boundaries (Shils 1975: 3).

In some contexts the straightforward postulate of an at least partial reflection between the two realms still possesses analytical utility. In Shils’ case it is applied in an original way to the symbolism which underlies modern nation states. Yet, in general, it is now competent but sterile to reiterate that ideologies sometimes support actual social arrangements and vice versa. Or, in the less hyperbolic language of Sally Falk Moore, one consequence of accepting such a straightforward correspondence between the two realms is to imply that “social arrangements” are “simply imperfect approximations of ideal models” (1969: 400).

The notion of correspondence masks the two-way interaction which occurs between symbolic conceptions of the social order and patterns of social action. The idea of interaction, as opposed to correspondence, necessarily implies a lack of fit between the two analytical levels at any given moment. Relatively few anthropologists have sought to trace out in concrete detail the consequences of such interaction. Those who have tend to be concerned with only one direction of it, the manipulation of ideological principles at the level of social action. Below I briefly analyze one such approach because it places my ensuing discussion in a more meaningful perspective. In an excellent article entitled “Descent and Legal Fiction” (1969), Moore argues that systems of descent, legal systems, and religious ideologies describe and explain the nature of the social universe. At the same time they provide a means for manipulating it. To illustrate her general argument, she argues that any descent system should be seen “as an ideology of identities that can be adapted for use as an organizing principle, rather than as an organizing principle in the first place” (Moore 1969:381). When adapted as an organizing principle, descent ideology or any other system of symbolic representations can vary considerably as it is manipulated for practical ends. Even when jural rights are ideologically claimed to emanate from a single principle such as descent, they usually derive from several and cannot effectively be traced to a single source (Moore 1969: 396).

In anthropological analyses which are concerned primarily with the ramifications of symbol systems as they serve as practical guides to and rationalizations for social action, there is a tendency to simplify the argument by treating symbol systems analytically as “timeless.” Occasionally this is made explicit (e.g., Schneider and Smith 1973: 6). A consequence of this approach is that what might be regarded as the communicative aspects of the relation of symbol systems to social action remain unstressed. After all, ideological systems are social activities that are maintained through various forms of expression, including ritual action. In the course of being expressed, such ideologies become modified and in turn modify the direction of social action. Thus, to be fully comprehended in relation to social action, such ideological systems must be seen in at least some of their successive historical modifications.

There is a closely related issue which it is appropriate to introduce here. Moore (1969: 400) implies that most ideological systems are analogous to the descent systems which directly concern her. As difficult as the analysis of descent systems might appear in some respects, I would argue that from an analytic point of view some ideologies, especially those considered religious, are often less distinctly bounded. Thus in most world religious traditions there is an inherent tension between formal ideological tenets propagated and accepted by an educated, religious elite and, coexisting with them, an implicit ideology of religion as locally practised and understood. The latter substantially overlaps with equally implicit, locally held assumptions about the nature of the social world. From an analytic point of view it is difficult to categorize such beliefs as “religious” and as Runciman has indicated, labelling such beliefs as ideology or simply as beliefs about the conduct of life is just as adequate (1970: 75–76). Indeed, from the viewpoint of the social elite in most religious traditions, the religious practices and attitudes of subordinate groups or persons frequently are considered uncivilized, pathological, or, in the case which concerns this article, un-Islamic. Yet for those who maintain such beliefs, they usually are taken for granted as authentic expressions of the religious tradition in which they participate. North African maraboutism is one such ideology. Precisely because it appears so closely tied to aspects of local society, maraboutism affords a particularly useful means of tracing the interaction between ideology and the social order.

Maraboutism as a Part-Ideology

Since the terms marabout[2] and maraboutism have been used in a variety of ways, I specify my own usage below and then indicate how marabouts form a part of Islam as locally understood. In the Moroccan context, marabouts are persons living or dead (dead, that is, only from an outside observer’s point of view) thought to have a special relation toward God which makes them particularly well placed to serve as intermediaries with the supernatural and to communicate God’s grace (Baraka) to their clients. Maraboutism is the usually implicit ideology and the ritual activities associated with such beliefs. Like any successful ideology, maraboutism and the ritual comportment associated with it have been flexible enough to accommodate changing historical situations. Marabouts and similar holy men elsewhere in the Muslim world are seen by their supporters as elements in a particularistic hierarchy through whom the supernatural pervades, sustains, and affects the universe. In a Weberian sense such a conception might be seen as a “magical” accretion to Islam; but from the viewpoint of tribesmen, peasants, and townsmen who hold such beliefs and act upon them, intermediaries with God are an integral part of Islam as they understand it. They regard themselves as Muslims, pure and simple, although they are aware of the disfavour in which such beliefs are held by Muslim scripturalists and reformists. Consequently, clients of marabouts often dissimulate their beliefs in front of such persons, especially in contemporary contexts.

Now and in the past, those who express and accept maraboutism are consciously aware of an alternative, formally articulated vision of Islam antithetical to their own. For this reason, maraboutism can be considered a part-ideology. It is never found in isolation, but co-exists with formal Islamic ideology. Further, it largely overlaps with locally maintained assumptions concerning the social order. Because of its implicit patterning upon (and patterning of) existing social realities, maraboutism can be considered a conservative ideology in Mannheim’s sense of the term (1971: 152–153). It does not have to be consciously articulated and defended in order to be maintained since it takes as its legitimation “the way things are,” to use a popular Moroccan expression to refer to the social present. This implicitness undoubtedly is one of the reasons why there have been relatively few discussions of maraboutic ideology in North African ethnographic literature, as opposed to police-dossier style accounts of the leadership, genealogical claims and mystic ties, and regions of influence of maraboutic orders (e.g., Depont and Coppolani 1897; Drague 1951).

The conjuncture of conflicting patterns of belief can be found in most world religions. Along these lines, Ernst Troeltsch (1960) has argued that Christianity can be seen as constantly in tension with social reality. Consequently its social history is one of shifts at various levels of compromise and noncompromise with the world. I think that a similar argument is critical to comprehending maraboutic beliefs. The Islamic tradition as it has emerged in various societies has generally contained conceptions of man’s relations with God both as comprising and lacking intermediaries. The Qur’an, as scripturalists and Muslim reformists vigorously stress, portrays all men as equal before God with no privileged intermediaries toward him.

In contrast, the strength of maraboutism rests on the implicit assumption that relations between men and God work just like all other social ties. Moroccans who act upon maraboutic beliefs explicitly see the relation of God with his marabouts as nearly analogous to patron-client ties in ordinary society. As one informant related, God, like a minister or the king, is too powerful to be approached directly, so the client works through a marabout who is “close” both to him and to God (Eickelman 1976: 161–162).[3]

Taken together in various syntheses according to historical context, the antithetical notions of formal Islam and maraboutism (or similar part-ideologies elsewhere in the Muslim world) have enabled Islam, analytically considered as a religious tradition, to encompass many varieties of social experience and to be regarded by its adherents at any given time as a meaningful religious representation of reality.

The Sherqawi Zawya

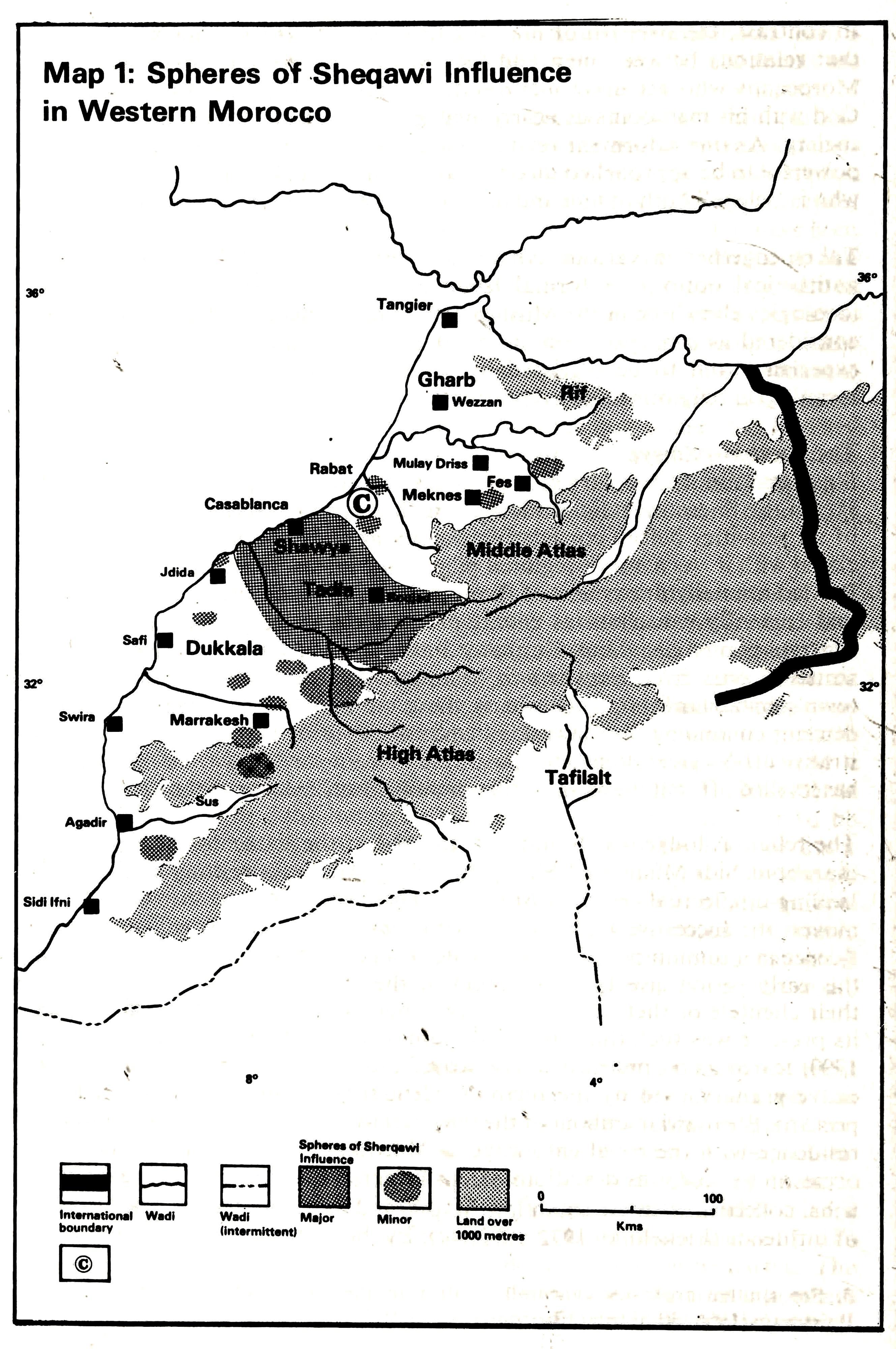

Since maraboutism is largely tied to specific social contexts, here I briefly sketch the Sherqawi religious lodge’s social history and the changing scope of its activities before considering the maraboutic ideology and cult associated with it. Asa major regional pilgrimage centre, the Sherqawi zawya of Boujad annually draws tens of thousands of pilgrims, singly and in groups, and currently can claim as clients most of the tribal collectivities of the western plains (see Map 1), many individuals from nearby towns, and scattered ones from elsewhere in Morocco. Approximately one-third of the town’s inhabitants, roughly twenty thousand as of 1970, claim Sherquawi descent; continuing Sherqawi dominance of the town’s economy and administrative offices gives Boujad the flavour of a “company” town. This dominance has levelled off, but the town is still primarily identified with the zawya.

The religious lodge was founded at the end of the sixteenth century by the marabout Sidi Mhammed Sherqi (d. 1601). Within a century it became a leading intellectual centre in Morocco. Through a series of shrewd political moves, the successive lords (Sid-s) of the zawya managed to enhance its influence in a tumultuous political climate. Hagiographies and court histories of this early period give little indication of the relation of the Sherqawa with their clientele or their internal rivalries, but by the end of the 18th century its prestige was such that Sultan Muhammed ben ‘Abdallah (reigned 1757–1790) feared its prominence and destroyed most of the town, including a collective granary used by the region’s client tribes. The Sultan also led the principal Sherqawi marabout of the time, Sid i-Hajj l-‘Arbi (d. 1819), to forced residence with the royal entourage in Marrakesh. The marabout used the occasion to accept as donations extensive agricultural estates (‘azib-s) from tribal collectivities in the south (see Map I) and to extend the Sherqawi sphere of influence (Eickelman 1972–1973: 44). By the early 19th century Sid 1-Hajj l-‘Arbi was considered one of the two most powerful marabouts in Morocco (Ali Bey 1816:1, 176–177).

A fuller picture of the activities of the zawya emerges by the latter half of the 19th century. Leading Sherqawa were able to influence the sultan and his entourage and in turn were considered significant enough to be watched, accommodated, and carefully manipulated by them. The Sherqawa exercised intermittently a de facto control over Makhzen (central government) appointments in the area, acted as intermediaries to the Makhzen on behalf of clients, secured the safe passage of commerce through the area, mediated tribal disputes, and performed a myriad of other roles. Clients from Rabat, Sale, Fes, Meknes, and the Tafilalt area to the south regularly sent offerings to leading Sherqawi marabouts, as did rural local communities (dawwar-s) and tribal sections (fakhda-s). Most collective client relations with the Sherqawa were in the area indicated on the map, but there were also a few groups as far south as the Sus and in the High Atlas mountains. These links, as with those in the main sphere of Sherqawi influence, depend largely upon the social landscape as perceived by the Sherqawa and their clientele at any given moment, as in the case of the lands acquired by Sid l-‘Arbi (d. 1819). His descendents still possess these lands and maintain ties with clients in the area.[4]

Client allegiances frequently shifted among various internal Sherqawi factions and occasionally away from them entirely. The vicissitudes of Sherqawi agricultural estates and subsidiary religious lodges, especially those located on the Shawya plain (for which documentation is more abundant), indicate how fragile and shifting was the balance of power among competing persons and factions. The sultan, his entourage, and local Makhzen officials often were at odds with each other. Each calculated the possibilities and advantages to themselves of enhancing or detracting from Sherqawi prestige, depending upon their estimation of interests at any given moment. Rival Sherqawa, merchants, rural strongmen, men of learning (‘ulama), and religious lodges elsewhere in Morocco made similar calculations of their own interests, the strength of the Sherqawa (or more accurately, of individual dominant Sherqawa), and the immediate opportunities available to them (Eickelman 1976: 31–64).

Growing French influence in the early 20th century at first added only another component to this multicentered shifting of alliances, but the social and political roles of the Sherqawa abruptly altered with the imposition of the protectorate in 1912. Prominent Sherqawa lost many of their preprotectorate privileges but were given local administrative sinecures, preferential access to French educational facilities, and favourable treatment as notables in administrative matters. The bases for social honour (in Weber’s sense of the term) rapidly shifted. For instance, to the end of the 19th century, leading Sherqawi marabouts maintained reputations as men of religious learning and were acknowledged as such by ‘ulama in Morocco’s leading cities. Yet by the 1920’s only a few isolated Sherqawa held such reputations. Still, given their competitive edge as notables, leading Sherqawa were generally able to shift their social, political and economic roles so as to maintain their social honour and elite status during the protectorate and after independence in 1956. Even as some leading educated Sherqawa deliberately dissociated themselves from maraboutic practices, clients of the Sherqawa continued to regard the success of some Sherqawa in any significant activity as a consequence of their maraboutic status and sought out those Sherqawa willing to maintain maraboutic ties with them.

Although the scope of activities performed by marabouts or kinsmen acting as proxies on their behalf has contracted and the size of offerings and sacrifices to them also has diminished, most rural Moroccans in the sphere of Sherqawi influence and a large number of urban Moroccans continue to maintain ties with the Sherqawa. In a few cases, as I have indicated, new ties have been established. The pattern appears to be the same for at least some religious lodges elsewhere in Morocco (e.g., Hatt 1974). Competition for acquiring a maraboutic reputation is no longer a principal means of maintaining social honour or power in Morocco, so few men actively seek reputations as living marabouts. But enshrined marabouts are another matter, and some persons who claim descent from them continue to “work” (ta-ykhdem) clients and to receive substantial donations of cash and produce for their efforts. Educated Sherqawa prefer to emphasize the piety, scholarship, and illustrious descent of their maraboutic predecessors rather than the popular conception of marabouts as “close” to God an J thus capable of efficaciously conveying his grace. In some contexts the association of the Sherqawa with maraboutism can be a distinct embarrassment. Yet maraboutism is far from residual in Moroccan society, for reasons that are described below.

Maraboutism and “Closeness”

Any ideological system is influenced by the social order in which it is expressed, and part-ideologies such as maraboutism are so closely tied to existing social arrangements that they cannot be comprehended without reference to them. Maraboutism is especially linked to two key concepts through which Moroccans make sense of existing social arrangements: obligation (haqq) and closeness (qaraba) (Eickelman 1976: 96–99, 141–149). Obligations are contracted and exchanged through services or offers of support. They are the culturally accepted means by which persons bond themselves to each other in Moroccan society and which determine the social honour of persons in relation to each other. Moroccans speak of having obligations “in” or “over” other persons, indicating the asymmetrical nature of the ties so created. All relationships impose obligations of calculable intensity. There is a considerable latitude within which such obligations can be contracted; thus ties of kinship and descent in themselves do not determine the nature and intensity of such ties. In general, persons strive for flexibility in relations where they are under obligation to others, while at the same time fixing as firmly as possible relations in which they hold obligations “over” other persons. Their goal is to preserve autonomy whenever possible and to be free to shift obligations as opportunities arise to enhance their social position.

“Closeness” is a form of relationship which is said to exist between persons bound together by multiple personal obligations and common interests and who regularly can be expected to act on each other’s behalf. Closeness is acting as if ties of obligation exist with another person which are so compelling that they are generally expressed in the idiom of kinship. This is because kinship ties, at least those involving common descent (‘blood’),were considered at the symbolic level to be permanent and unbreakable. Some relations of closeness are based upon kinship, although as stated, closeness based upon kinship is generally not sharply differentiated from closeness based upon other grounds. Closeness also develops out of patronage and clientship, residential propinquity or neighbourliness, membership in rural local communities or other “tribal” entities, and common occupation. Quite frequently these bases for closeness overlap and persons deliberately seek to make them do so. A brother can also be a client and a neighbour may seek to be considered a kinsmen, if it will enhance his status or secure practical advantages.

Ties involving marabouts are a particular instance of the concept of closeness. Below I first discuss the closeness said to exist between marabouts and their clients, then the complementary issue of the maintenance and legitimation of elite status within a maraboutic descent group.

The primary consideration in the client’s eye view of marabouts is that they are close (qrib) to God and therefore capable of influencing him or at least of relaying his grace. Having or acquiring a reputation for grace is sufficient for being a marabout, but the most-influential of them are distinguished by a number of complementary attributes. One of these is the claim of patrilineal descent from long-established marabouts such as Sidi Mhammed Sherqi, who have descendants actively maintaining their shrines and other cultic apparatus and thus indicating closeness to their ancestor. Marabouts claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammed, or, in the case of the Sherqawa, from Sidi ‘Umar (d. 644), the second caliph in Islam, are especially prominent. Such persons intermarry as equals but do not give their daughters in marriage to “commoners” (fawam), those who cannot claim either type of privileged descent. Second, marabouts are generally attributed with some degree of religious knowledge (‘Urn) and always with mystic insight. Both of these qualities are reputedly transmitted to them through dyadic ties with earlier generations of maraboutic scholars and mystics.[5] Finally, marabouts must be willing to transmit their baraka to their clients or to have someone claiming closeness to them who does so on their behalf.

Despite the formal ideological claim that only God knows who is “close” to him, clients necessarily seek this-wordly signs to determine who marabouts are. Within the limits of their prosperity and other considerations, clients seek ties with those marabouts or their descendants thought most capable of sustaining-or enhancing their interests. A primary contemporary sign of baraka is the ability of marabouts or some of their descendants to maintain a prosperous life-style based at least in part upon their clients’ offerings. In the past another sign of the mystic powers of marabouts was their ability to act politically on behalf of their clients. Sherqawa can still occasionally do so, as I have indicated above. Such political successes are popularly attributed to Sherqawi baraka whether or not the Sherqawi involved actively seeks to be regarded as a marabout or takes material advantage of Boujad’s pilgrim traffic.

Like other social ties, those with marabouts are thought to depend upon continuing exchanges of obligations. The principal problem for believers in marabouts is how to create and maintain such ties with marabouts or those “close” to them (descendants or other persons) in order to ensure a flow of grace to sustain their particular concerns. They seek to contract personal, dyadic bonds of obligation with marabouts in order to compel marabouts to act on their behalf.

Maraboutic Descent

Marabouts with descendants and with established cults are considered the most prestigious, since the well-being of their descendants and their cult is a concrete indication of the benefits of closeness to them. A maraboutic descent group is one which shares certain rights and prerogatives on the basis of a recognized claim to common maraboutic descent. The concept of closeness is crucial to understanding such claims. Ideologically, Sherqawi status is expressed in the idiom of patrilineal descent from the marabout Sidi Mhammed Sherqi. Yet such formal determination of status is rarely invoked and is frequently impossible on a practical basis. Hence it is possible to acquire Sherqawi status, even in Boujad itself, and not have such claims directly challenged, by “known” Sherqawa. In practice, one is “known” (me‘ruf) asaSherqawi on the basis of a combination of attributes. These include residence in a Sherqawi quarter, marriage patterns, political and economic alliances, and other aspects of comportment. Most Sherqawa are known through face-to-face relations among themselves and to their clients.

The acquiesence of known Sherqawa to such assertions of Sherqawi status can be explained on two levels, the analytical and that of social practice. Analytically, it is useful to employ Scheffler’s distinction between descent categories and descent groups (1965: 62). The idiom of descent in itself gives form only to categories of persons which can remain only vaguely bounded. Membership in such a category does not imply an obligation to act in common with other members of that category. However, perceived common interests can encourage the formation of descent groups out of such categories. On the related practical level of actual social arrangements, I already have indicated that Moroccans constantly re-evaluate their ties of closeness in terms of maintaining and whenever possible enhancing their social status. Thus in some instances the attribute of being a Sherqawi is a relatively minor component of social identity; in others it can play a major role.

Sherqawi descent groups show the same flexible patterns of boundary as do other collectivities in Moroccan society. Currently, the Sherqawa are divided into eight descent groups.[6] Six are considered to descend from sons of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi, although no one claims to know the intervening genealogical links. Some persons refer to written records which legitimize such links, but these never are produced and cannot be located. The remaining two groups are the most prominent. They claim descent from another of the marabout’s sons, but in addition claim as eponymous ancestors 19th century Sherqawi “lords,” so designated because they effectively controlled the zawya or at least a substantial part of its resources. Each of these descent groups has a quarter (derb) in the town where the core of its membership resides, although non-Sherqawi also reside in these quarters. Each descent group possesses a shrine of its common ancestor, although this is not necessarily located in its quarter and many Sherqawi shrines are not directly linked to any specific descent group.

The same concept of closeness underlies claimed relations of kinship among the Sherqawa as among commoners. Substantial material and social benefits are associated with Sherqawi descent for at least some Sherqawa. Hence the genealogies tracing their descent are generally more complex than is the case for commoners. Or so the Sherqawa assert. Yet the only component of their genealogy which the Sherqawa commonly know is the name-chain (silsila) of the “lords” of the zawya. This name-chain stretches in an unbroken line back to Sidi Mhammed Sherqi, with variants occuring only over the “lords” of the last century. Earlier factional disputes are not socially significant and are not reflected in the name-chain.

All Sherqawa point to this name-chain as legitimating their status, but only members of the two most prominent “mainline” descent groups can actually trace agnatic ties with the Sherqawi lords. With few exceptions, the most prominent Sherqawa of the past century come from these two descent groups. For reasons of shared material interests and prestige, members of the two “mainline” groups show a much greater concern over the boundaries of their groups than do other Sherqawa. They generally can trace in detail their genealogical ties over at least three generations and possess a more precise knowledge of the scope of their kinship ties with contemporaries. They sharply distinguish between persons who claim closeness to them solely on such bases as residential propinquity and those related through agnatic and affinal ties. These two mainline groups have substantial common interests and in general have managed to defend them. They have kept largely undivided estates from their prominent ancestors of the last century. Through Islamic inheritance many of them are thus entitled to substantial revenues in addition to their shares in the offerings at the main shrine (shares available in principle to all Sherqawa).

Sherqawa active in the maraboutic “trade” seek to manifest closeness to leading Sherqawa before their clients. This is despite the fact that most prominent Sherqawa of today, even when popularly regarded as marabouts, no longer take an active part in maraboutic enterprises. Identification with the two mainline descent groups gives persons a competitive edge in maintaining status, but participation in the aristocracy or inner elite of the Sherqawa (or esteem in clients’ eyes) is not determined exclusively by descent group membership. For example, a member of one of the non-mainline descent groups, a textile merchant, successfully entered politics shortly after independence. At first he actively dissociated himself from Sherqawi maraboutic activities (because the mainline Sherqawa failed to support him in election campaigns) and in fact became prayer leader (imam) of one of Boujad’s two principal mosques. In recent years he has consolidated his influence by claiming, at least away from Boujad, to be lord of the zawya and of the mainline Sherqawa. He employs his visible hold over a rural clientele as a means of legitimating his political influence.

Until the beginning of this century, Sherqawi descent and maraboutic status were largely coterminous. The principal means for a Sherqawi to acquire social dominance was to seek to be regarded as a marabout and to attract a clientele. The means of acquiring social prominence are now more varied. The immediate descendants of late 19th and early 20th centuries Sherqawi marabouts have often maintained elite status, at least when they have acquired an education or adapted successfully to modern commercial and political activities. Through these activities it is possible to maintain a social position that identity primarily as a marabout no longer allows. Many of the Sherqawi elite dissociate themselves from the maraboutic interests of some of their kinsmen because such activities would open them to attack and ridicule from educated persons. Such Sherqawa seek to redefine the activities of some of their kinsmen and ancestors in light of the formal doctrines of reformist, modernist Islam. By any criteria, some Sherqawa have been prominent in Morocco for centuries. — as marabouts, counselors of sultans, religious scholars, and recently as educators, merchants, ministers of state, doctors, judges, administrators, and in one case, as a sociologist. The very success of these Sherqawa is taken by maraboutic clients as a sign of continuing Sherqawi religious prominence. The elegant Sherqawi shrines are maintained through their donations.

Ideology and Practice

The analytic distinction has already been made between maraboutism as an ideology and maraboutism as a concrete set of social practices. The contracting economic bases of marabouts, especially living marabouts, has had an impact on the ideology of maraboutism. It is this impact that I now wish to discuss in reference to the Sherqawi maraboutic cult. Ideologically, marabouts and maraboutic cults form a symbolic base for order in society. Maraboutic cults such as that of the Sherqawa are identified with specific towns and regions, although the correlations between maraboutic cults and specific rural or urban local communities are not immutable and some groups may even divide their allegiances among several maraboutic cults. The implicit ideology of such cults also provides a bridge between the divine template for human conduct as revealed in the Qur’an and periodically renewed by reformist movements in Islam, and the realities of “the way things are” in Moroccan society. Maraboutic cults are linked to specific social forms but are more than a reflection of such forms. This is indicated by the analysis of the means through which specific ties with marabouts are maintained.

There are both collective and individual ties with Sherqawi marabouts. Presently, only tribal groups maintain collective ties with the Sherqawa, although in preprotectorate times urban quarters and occupational groups in western Morocco also did so. In certain parts of Morocco, including Marrakesh (Jemma 1971), collective urban ties still exist. Individual ties are maintained by both townsmen and tribesmen.

Personal and collective ties of obligation with marabouts rest on a similar base, so that the form which collective and personal ties take and their distribution are not sharply distinguished. In both cases the fundamental unit of social structure is the person rather than their attributes or statuses as members of groups. Thus, persons participating in collective sacrifices and offerings say that they do so because in that manner they are able to present a more substantial sacrifice or offering to a marabout and thus more forcefully indicate their faith in him. In other words, persons deal with marabouts collectively rather than individually in order to have more “word” with the marabout. Of course, such ties also denote the boundaries of particular social groups at any moment.

The accompanying map indicates a large, contiguous sphere of Sherqawi influence covering the Shawya and Tadla plains. In rural contexts, the Sherqawa are the dominant religious lodge in the area, although to a lesser extent other maraboutic orders also are represented. The urban situation is slightly more complex, but only due to post-1912 developments (with the exception of a few coastal towns including Casablanca). It also should be kept in mind that Boujad was the only town of significance in the interior of the area prior to 1912. An important earlier form of ties with the Sherqawa took the form of urban religious brotherhoods[7] (tariqa-s), whose members met weekly, usually on Friday afternoons, in a local lodge (zawya) maintained for that purpose. There are indications that these lodges may have been related to trading networks based upon Boujad in the late 19th century (Eickelman 1976: 199). They exist alongside non-Sherqawi religious lodges, most of which gained adherents in the early years of the protectorate, when merchants and craftsmen joined them as a means of asserting independence from the Sherqawa. From the early 1930s onward these brotherhoods declined in face of reformist Islam and the emerging nationalist movement.

Personally contracted ties with the Sherqawa are much more widespread than those of brotherhoods in the urban setting. Significant numbers of townsmen occasionally travel to Boujad to visit Sherqawi shrines there, as well as prominent non-Sherqawi shrines elsewhere. Generally, however, only townsmen of rural origin in western Morocco make regular offerings to the Sherqawa over extended periods of time. More substantial in terms of aggregate value are the donations of animals and cash irregularly made by persons who seek the intervention of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi or other principal Sherqawi marabouts in cures of illness and infertility. These offerings occur only at times of personal or household crisis and to a lesser degree are also made to non-Sherqawi marabouts.

The ties between the Sherqawa and specific tribal groups in western Morocco at first appear more stable than the amorphous, discontinuous ones sustained in urban settings. The major sphere of Sherqawi influence has remained relatively constant since at least the 1880s. This is in large part because a succession of sultans in the late 19th century deliberately sought to extend Sherqawi influence in the area at the expense of other maraboutic lodges. In 1901 this policy was formally reversed, but by then the sultanate was unable effectively to impose its will in the area. From 1907 onward the French used Sherqawi influence for their own ends. Once the pax gallica was formally established in 1912, spheres of maraboutic influence were largely frozen in place. This is in contrast with the 19th century and what is known of earlier periods, when the geographical sphere of Sherqawi influence expanded and contracted with political and economic currents. In the 1880s, for instance, the Sherqawa had clients in the Middle Atlas mountains and actively sought to extend their influence in that direction (Eickelman 1976 : 55). The existence of Sherqawi agents, holdings, and clientele in key Moroccan cities outside their main sphere of influence, such as Fes, Meknes, Marrakesh, and Sale can similarly be explained in terms of their seeking to widen the scope of their activities. Of course, the geographical pattern of Sherqawi influence is partially related to ecological constraints. Some geographical features tend effectively to impede communication in certain directions. Consistently more important, however, were the patterns of social and political alignments at any given moment. This explains in part the patterns of Sherqawi influence in an area as far away as the Sus valley. Certain Sherqawa were effectively able to create and maintain ties with groups and individuals there and the development of ties with the Sherqawa was considered more advantageous than the development of ties with local maraboutic descent groups. Such decisions depend upon judgements of the efficacy of particular marabouts and the availability of particular marabouts or their descendants.

Myths relating the exploits of particular marabouts are a crucial element in maraboutic ideology. Those for the Sherqawa are known throughout western Morocco and resemble in form those associated with marabouts and maraboutic descent groups elsewhere. To the extent that these myths frequently invoke place names and other features peculiar to specific geographic divisions, they are localized. Yet these characteristics are almost incidental to the stress in the myths upon how marabouts become tied to specific groups or persons. For example, one myth relates how the entire area that surrounds Boujad was wilderness when Sidi Mhammed Sherqi first arrived there (Eickelman and Draioui 1973: 201–205). The marabout located water, cleared the forest, and forced wild animals out of the area. Then he called upon various groups to settle there and establish a covenant ('ahd; bay'a) with him. So far I have collected roughly sixty myths, including variants, dealing with Sherqawa. Virtually all of them concern the means by which covenants are established and honored between named groups and Sidi Mhammed Sherqi and his sons. Such covenants are represented as being maintained through such means as sacrifice, the giving of women to the Sherqawa, the claim of a common, distant ancestor between the marabout and his clients, and the claim of mere physical propinquity in the distant past.

In exchange for sacrifices and the renewal of the covenant, Sherqawi marabouts appear as guarantors of the moral order insofar as it affects their clients; in some cases the clients are made Muslim at the same time a covenant is established. One common theme in the myths is that of Sherqawi marabouts defending covenanted groups from unjust tyrants. The ties of the Sherqawa with other maraboutic centres and with Mecca are also frequently stressed. Although in real life Sherqawi marabouts and other Sherqawa have made the pilgrimage to Mecca, there are few sustained ties with other maraboutic descent groups. The social order depicted in the myths is constructed out of particularistic bonds of obligations, but the myths also depict the submission of both marabouts and clients to an Islamic code of conduct.

Covenants with the Sherqawa are particularistic but far from being primordial. Most client tribal groups in western Morocco claim that their covenant with the Sherqawa was sealed in “early” times (Bekri). “Early” is that range of time, internally atemporal, which forms a backdrop to the ordinary, fully known social horizon (see Eickelman 1977). Events that occurred in early times are thought to have a significant impact upon current social alignments but the full social context of such early events is considered unknown and unknowable. Significantly, the tribal groups mentioned in the covenants of the myths are not “real life” collectivities in the sense of being effective units of social action either now or in the historically known past. Tribal names mentioned in the myths are generally those from which many existing groups claim to have derived, but even this is not always the case. It is useful to think of the names mentioned in these myths as together forming a conceptual grid through which covenants can be legitimated as well as shifted as occasion warrants through the “discovery” of alternate formulations of the grid.

The notions of obligation and closeness underlie the dyadic bonds through which marabouts and their clients remain “connected” (mtesslin). A “connection” can be accomplished in three complementary ways. The first is through offerings and communal meals with those living descendants of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi, not themselves considered marabouts, who claim specific ties with certain tribal sections and rural local communities. These descendants are called “visitors” (zewwar-s)[8] because they literally visit clients’ households and tents twice each year — in spring when herds are traditionally divided and in early summer just after harvesting — to collect the offerings (zyara) considered the due of the marabout. When they make donations or offer communal meals, clients specifically remind the visitor that he is to accept them on behalf of his ancestor. In return, visitors offer an invocation (da‘wa) to their maraboutic ancestor in front of their clients. Visitors know each individual involved and carefully specify the particular concerns of each household: the desire for male offspring, good harvests, the wellbeing of persons and animals. In the past, visitors also mediated tribal disputes and brought major matters to the attention of more influential Sherqawa. When clients are in town, their Sherqawi visitors occasionally assist them in various matters, but in general the visitors no longer can serve as efficacious intermediaries in practical matters. An interesting consequence is that clients now explain their offerings to visitors as alms to the poor (sadaqa) and treat the visitors in an offhand way. Still, contact with visitors is considered necessary in order to maintain ties with their maraboutic ancestors.

The second way of remaining connected is through annual sacrifices at the shrine of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi and those of certain of his descendants. These are made in the presence of living Sherqawa, as well as the visitors associated with particular pilgrims and pilgrim groups who again act on behalf of the marabout. Such sacrifices can be made by individuals who seek specific favours from marabouts and are made regularly throughout the year. Here I discuss primarily the collective offerings that are made. Most collective sacrifices are made each fall during the festival of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi. This is not a single event, but a period of roughly two weeks during which client groups make a pilgrimage to Boujad. For transhumant groups, the festival generally coincides with the move from summer to winter pastures. Especially over the last two decades, the Sherqawa have discouraged actual sacrifices, although many still occur. One reason for their discouragement is pressure from other townsmen, including Sherqawa, who are embarrassed by what they consider the more “primitive” forms of maraboutism (although a similar argument is never made concerning the sacrifice of an animal for feast days recognized by “formal” Islam). Another reason is the desire on the part of the Sherqawa involved in the pilgrim “trade,” as they refer to it, to live from the proceeds of the pilgrim traffic. To this end, they persuade pilgrims whenever possible that the offer of a sacrificial animal or the equivalent in cash has the same benefit as a sacrifice.

In some cases, sacrificial animals are slaughtered but immediately sold at regular prices at a butcher’s shop; in most cases, however, Sherqawa dispose of the animal (or offerings in kind) through regular market channels.

An unanticipated consequence of the gradual abandonment of actual sacrifices and the greater demand for marketable offerings is the rapid attrition of client donations. Traditional offerings of cereals and of animals to a lesser extent were considered largely outside of the domain of the cash economy prior to the severe economic dislocations of the Second World War. It is true that to a certain extent obligations to marabouts were always thought of in terms analogous to the market situation. In all forms of “remaining connected,” acrimonious bargaining often occurs over the size of an offering or sacrifice. Nineteenth century correspondence attests to the fact that such bargaining is not recent. I stress analogous because informants emphasize that a cash value cannot be placed on any bond of closeness or obligation, including those with marabouts.

Yet under current conditions the scope of maraboutic powers is much more circumscribed than it was in the past and virtually inexistent in the realms of politics and economics. Clients get less out of maintaining such obligations than they did in the past. In addition, when Sherqawi visitors and the caretakers of major Sherqawi shrines convert offerings into cash at the market, often before the eyes of their clients, the latter are encouraged to consider their ties with marabouts as identical with those of the marketplace. Doubt in the prevalence of marabouts has always been present (cf. Firth 1974), but under present conditions this doubt becomes systematic and encourages consideration of the tenets of formal Islam as the only valid religious expression.

The final means of remaining connected with the Sherqawa is through offerings and communal meals with living marabouts. I have already mentioned why this practice is rapidly disappearing. Living marabouts have difficulty in maintaining their reputation due to decreasing influence and revenues and are stigmatized by educated Muslims. Unlike enshrined marabouts, living ones are not insulated from direct calculations of their efficacy and comments upon the lavishness, or baraka, shown by their hospitality. Once again, as the benefits of maintaining obligations with marabouts become more vague and indistinct, not only do pilgrims place less value in maintaining such obligations, but maraboutism as an implicit ideology ceases to make sense in terms of the concepts of obligation and closeness.

Sacrifices and Social Groups

Another dimension of maraboutic ties is the means by which groups are formed that collectively sacrifice and make offerings. As an example I use the Sma’la of the upper Tadla plain, located about twenty kilometers to the north of Boujad. They are one of the most “traditional” tribes of the area in that they remain largely transhumant (as were virtually all the tribes of the area prior to the 1920s) and vigorously maintain their covenants with the Sherqawa. Therefore their current practices (and those documented for the protectorate and the pre-1912 period) provide more insight into precolonial practices than is the case for groups that have been more radically affected by subsequent political and economic transformations. The nature of tribal society in this early period is significant because maraboutism has been primarily linked in Morocco to “segmentary” tribal societies. Here I present an alternate account of traditional rural society as it existed in some parts of Morocco and which does not necessitate postulating a radical dichotomy between past and present social forms.

The pasture lands of the Sma’la are still collectively owned; only recently has legislation been passed which, when eventually implemented, will convert all “tribal” lands into private ownership. Agricultural lands are owned by individuals, as was also the case in the region during the preprotectorate period. Herds are also individually owned, although in practice the head of each tent (household) or herding unit exercises effective control over the disposition of animals owned by individuals residing with him. Agreements over grazing rights were made with neighbouring groups both on a person-to-person basis and on the basis of larger collectivities. Even among the “traditional” Sma’la, therefore, individuals had a considerable area of latitude in which they could manipulate their social identities. Such latitude is administratively inconvenient, so the colonial administration and its post-1956 Moroccan successor discouraged small-scale, informal pastoral agreements, sometimes using the pretext that only agreements binding on the larger, administratively recognized tribal subdivisions were really “traditional.” Neat administrative organigrams of tribal organization and administrative jurisdictions would be damaged by acknowledging a continuous flux in social alignments.

Tribesmen employ the idiom of agnation to describe relations among themselves, but political relations are conceptualized in other idioms as well. Nor was the idiom of agnation more pervasive in the historically known past, which in this case means since the late 19th century. Tribesmen often use the analogies of the tree and the human body to describe their interrelationships. To follow through the first analogy, as one tribesman said: “We are like the branches of a tree, but each branch is on its own.” Similarly, in some contexts tribesmen assert that they are all linked through ties of blood, but explicitly deny that the claim of such ties obliges them now or obliged them in the past to act in specified ways. In other words, social and political action flows along numerous lines: kinship, patron-client relations, and other bonds of necessity or mutual interest. The area of latitude in which rural Moroccans can shift their social ties is more circumscribed than in an urban milieu, but it is still fairly considerable.

When tribesmen are asked to describe their relations with the Sherqawa, they frequently begin by discussing the nature of the rural local community (dawwar). The term literally means “circle.” In the era of preprotectorate insecurity, household heads of local communities pitched their tents in a circle during transhumance. They collectively agreed upon pastoral movements and upon the tenor of their relations with other groups. Members of local communities claim to be linked through agnatic ties but are unable to demonstrate specifically that such ties encompass all members of their group. When asked to trace such relations in detail, tribal informants invariably responded that only someone older could do so. In turn, elderly informants vaguely referred to “earlier times” as the period when the local community was entirely linked through traceable agnatic relations. In actuality, local communities commonly consist of several agnatic cores linked by complex affinal and contractual ties.

There are two significant criteria for the existence of a rural local community. First is the general willingness of its members to support each other in mutual interests. Second is the capacity to act collectively on certain ritual and political occasions. The comparison with the earlier discussion of maraboutic descent groups (or for that matter any other such groups in Morocco) should be clear. Each local community has a council (jma’a), although this is not a formal body as has frequently been assumed by protectorate administrators or their Moroccan successors. Any adult male household head who has an interest in the issues at hand participates, although the opinions of those who are economically or politically weak tend to be discounted or ignored in favour of those with more substantial material interests and persuasive skills. When necessary or convenient, such councils informally agree upon a spokesman (mqaddem) to represent them to outsiders. Each local community also has its own mosque, burial ground, and maraboutic tomb. The latter is usually a derelict structure to which no offerings are made except for candles and small coins left by the local community’s women and children. At any time, each household or tent belongs to only one local community. Membership is demonstrated by sustained ties of “closeness,” a concept which I earlier illustrated in relation to the urban Sherqawa.

The refusal or inability of a tent to contribute to certain collective obligations does not in itself indicate dissociation from a local community, but it affects the capacity of a household head to have a say in the community’s affairs. When a definitive break occurs a household shifts its allegiance to another local community, although its rights in agricultural land remain unchanged. When a group of tents or households breaks away and forms a separate local community, it is distinguished by its own mosque, burial ground, and maraboutic tomb. One of the numerous unused structures usually is appropriated for the purpose, although new tombs occasionally are built.[9]

When Sherqawi visitors arrive in local communities, they usually deal with a spokesman agreed upon for that purpose. He sees that the offerings of grain and animals are forthcoming from the households of his group and cajoles recalcitrant members. A similar informal arrangement is made at the level of tribal sections (fakhda-s) in jointly contributing sheep or bulls for sacrifice (for all Sma’la tribal sections refuse substitutes for sacrifices) at the main Sherqawi shrine in Boujad. No such sacrifices are made at the level of the Sma’la acting as a “tribal” collectivity, nor were they in the known past.

Existing social alignments can be discerned through the clusters of persons that contribute to various maraboutic obligations. More specifically, the conduct of individuals and groups at the annual festival of Sidi Mhammed Sherqi constitutes a publication of new social alignments. These are revealed in the arrangement of tents, patterns of offering and sacrifice, and the part taken by local communities and tribal sections in “powder plays” (tehrak-s)’ competitive displays of horsemanship. Such “powder plays” among the Sma’la, as with groups participating in similar activities elsewhere in Morocco, are always accompanied by heavy, serious betting between the groups involved. In part these competitions reflect the lack of formal rules inherent in the Moroccan concept of closeness. I he judgment of their outcome is left to the competitors themselves and to any support they can muster among onlookers. Differences that develop during the annual festival often themselves engender new lines of social demarcation.

Once such shills in the composition of groups are effected, appropriate realignments are made in how these groups conceive of their relations with one another. Similar adjustments occur when groups or individuals decide that their link to a specific Sherqawi “visitor” can or should be replaced by one more efficacious.

Available evidence for the preprotectorate past suggests that the rural social order and its relation to maraboutism was basically similar in pattern to what I have described above. Of course, it can be argued that the political and economic transformations of the last sixty years have been so substantial that tribal organization described primarily from contemporary ethnographic evidence or the contemporary remembrance of things past differs fundamentally from that of the preprotectorate era. Some basic shifts have occurred. Since the protectorate, for instance, administrative intervention has greatly restricted the possibilities of intergroup hostilities. Matters previously settled among the tribes themselves or through maraboutic mediation now almost inevitably involve government intervention.

Two sets of events involving the Sma’la and other groups in western Morocco during the preprotectorate era are known in sufficient detail to suggest an essential continuity in local conceptions of the social order. One was the manner in which resistance was organized against the French for three years beginning with 1910. Rapid shifts of alignment occurred that indicate a flexible, opportunistic perception of the mechanics of alliance formation. A similar flexibility is evident in examining the repercussions of the struggle for the sultanate between the brothers Mulay Abd l-‘Aziz and Mulay Hafed which began in 1907. Protracted local disputes over water rights and other matters, maraboutic allegiances both to Sherqawi factions and other maraboutic centers, the attitudes of local communities and tribal sections about the legitimacy of the two rival sultans, and assessments of the wisdom of resistance to the French all entered into consideration. The alignments of the various collectivities involved bore minimal relation to asserted agnatic relationships.

My concern with extending my argument to at least the known precolonial past is to indicate that there is no need for a “special” explanation of the relation of maraboutism to the tribal social order. The most widely known discussion of this issue in English is contained in the writings of Ernest Gellner. He is primarily concerned with the role of marabouts in social structures which qualify as “segmentary” and which no longer prevail in Morocco. Thus Gellner’s argument is necessarily relegated to the precolonial past when he considers it reasonable to assume that the society in the High Atlas region which he studied was in a stable “kind of Social Contract situation” over an indefinite period (1963: 146; 1969: 158–159). Insofar as present-day institutions can be assumed to have been in “a kind of sociological ice-box” (Gellner 1973: 59), he argues that they can be taken as reliable indicators of past situations.

A principal drawback to this set of assumptions is that it offers no explanation for the role of marabouts and the ideology of maraboutism in non-segmentary situations in the past or for the continuing, albeit modified, significance of both the ideology of maraboutism and the activities of maraboutic cults in the present. Prior to the appearance of the Islamic reform movement in Algeria in the early decades of this century, maraboutism was so persuasive that most urban and rural Algerians took it for Islam pure and simple (Merad 1967: 58). Merad’s statement can be applied even more firmly to Morocco. As for the present, as indicated earlier, rituals associated with marabouts have held their own in many urban and rural milieux (Hatt 1974: 25; Pacques 1971; Jemma 1971; Eickelman 1974a: 229). Contrary to the fervent desires of some Muslim reformists and other educated Moroccans, the ideology and practice of maraboutism has not just melted away in the face of recent social and economic transformations. At least with respect to religious belief and practice, these facts argue against assuming a radical discontinuity between past and present in Morocco’s social history, and especially against any one-to-one relation of ideology with the social order at any historical moment.[10]

Conclusion

The Moroccan concept of closeness relates to maraboutism on two levels. As an organizing principle for social arrangements, it underlies such diverse social forms as descent groups (including maraboutic ones), urban quarters, tribal sections and rural local communities, and ties between marabouts and their clients. Closeness as an organizing principle is essential for comprehending the particular implicit ideology and social relations described in this paper. I have indicated the diversity of historical and social-contexts in which closeness operates to suggest its variable relation to maraboutism taken as social ideology and practice. Any one set of “social arrangements” considered in isolation with maraboutism as an ideology would lead to an analytically unjustified assumption of a one-to-one link between them.

Maraboutism like any other ideology is socially maintained. It is based partially upon an implicit analogy between ordinary social relations and those which prevail between men and the supernatural. In fact, for those who accept maraboutism, there has traditionally been no sharp division between the two realms. Persons considered “close” to marabouts, especially members of their descent groups associated with cult activities, are thought to have a special influence over them. The notions of obligation and closeness make these ties comprehensible.

This paper has been concerned with two sorts of transformations which occur in relations between marabouts and their clients. First is the continuous revaluing of the utility of specific social ties, including those which exist between marabouts and their clients. These can lead to the rise or fall in the fortunes of specific marabouts, maraboutic descent groups, or regional pilgrimage centres such as Boujad. In themselves, this form of realignment does not substantially modify the content of maraboutism as an implicit ideology.

The second form of transformation directly modifes the form of maraboutic ideology and analytically is the more interesting (and neglected) form. It concerns shifts in social action which engender ideological change. Put succinctly, my position is that to be understood sociologically, maraboutism has to be considered in a range of historical contexts. In the preprotectorate past, now only a lived experience for the most elderly of Moroccans, marabouts had a much greater range of social action than they have had in later periods. Living marabouts complemented enshrined ones and directly or through proxies could choose to affect the circumstances of their clients. More recently, the political and economic activities of marabouts became markedly circumscribed, until what remains to them is primarily a “religious” sphere of influence distinct from practical concerns. In earlier periods such an explicit distinction did not exist. With marabouts in the past, the intercession of the supernatural in such concerns was a daily occurrence. Now the benefits which derive from sustaining ties with marabouts and their descendants are vague and ill-defined.

The form in which ties between marabouts and clients are established and reaffirmed has also shifted and this has had more radical consequences for maraboutism as an ideology. Few persons can sustain reputations as living marabouts, and clients in any case have less to do with them. Both living marabouts and maraboutic “visitors” have encouraged the substitution of sacrifices for other forms of offering, and when offered goods in kind have directly converted them for cash through regular market channels. A consequence of this shift has been to encourage clients to consider their transactions with marabouts just as they would all other transactions. When viewed in this fashion, there is no perceptible benefit in maintaining ties with marabouts. Maraboutism ceases to make sense as part of “the way things are.”

Finally, the strength of maraboutism is precisely in its being taken as an implicit ideology. Those who support marabouts are aware in outline of the tenets of “formal” Islam and indicate their support for it through building mosques — most rural local communities have one — and hiring Qur’anic teachers. Although formal Islam also claims to be related to all aspects of life, there is no direct, personified means by which the supernatural can pervade the social order as is the case with maraboutism. Formal Islam thus requires no direct analogy with the nature of the local social order. In contemporary Moroccan society this disjuncture allows it increasingly to be taken as a religious representation of the world more meaningful than maraboutism.

References

Ali Bey (Domingo Badia y Leblich)

1816 The Travels of Ali Bey. 2vols. Philadelphia. M. Carey

Beidelman, T. O.

1974 W. Robertson Smith and the Sociological Study of Religion. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Berque, Jacques

1949 Ville et universite: Aper?u sur I’histoire de l’ecole de Fes. Revue Historique de Droit Francais et etranger (4th series) 27: 64–117.

1953 Qu’est-ce qu’une “tribu” nord-africaine? In Eventail de I’histoire vivante: Homage a Lucien Febvre. Vol. I. pp. 261–271. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

1955 Structures sociales du Haut-Atlas. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

1957 Quelques problemes de I’lslam maghrebin. Archives de Sociologie des Religions 2: 3–20.

Boissevain, Jeremy

1966 Patronage in Sicily. Man (n.s.) 1: 18–33.

Christian, Jr., William A.

1972 Person and God in a Spanish Valley. New York and London: Seminar Press.

Depont, Xavier and Octave Coppolani

1897 Les confreries religieuses musulmanes. Algiers: A. Jourdan.

Drague, Georges (Georges Spillman)

1951 Esquisse d’histoire religieuse du Maroc. Paris: J. Peyronnet.

Durkheim, Emile

1915 The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: Allen and Unwin.

Eickelman, Dale F.

1972–1973 Quelques aspects de l’organisation politique et economique d’une zawya marocaine au XIXe siecle. Bulletin de la Societe d’Histoire du Maroc 4–5: 37–54.

1974a Islam and the Impact of the French Colonial System in Morocco. Humaniora Islamica 2: 215–235.

1974b Is There an Islamic City? The Making of a Quarter in a Moroccan Town. International Journal of Middle East Studies 5: 274–294.

1976 Moroccan Islam: Tradition and Society in a Pilgrimage Center. Austin and London: University of Texas Press.

1977 Time in a Complex Society: A Moroccan Example. Ethnology (in press) Dale F. Eickelman and Bouzekri Draioui

1973 Islamic Myths from Western Morocco: Three Texts. Hesperis-Tamuda 14: 1925–225.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E.

1940 The Nuer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Firth, Raymond

1974 Faith and Scepticism in Kelantan Village Magic. In Kelantan: Religion, Society and Politics in a Malay State. William R. Roff, ed. pp. 190–224. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford

Gellner, Ernest

1963 Saints of the Atlas. In Mediterranean Countrymen. Julian Pitt-Rivers, ed. pp. 145–157. Paris and The Hague: Moulton.

1969 Saints of the Atlas. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

1973 Political and Religious Organization of the Berbers of the Central High Atlas. In Arabs and Berbers. Ernest Gellner and Charles Micaud, eds. Pp. 59–66. London: Duckworth.

Hatt, Doyle

1974 Skullcaps and Turbans: Domestic Authority and Political Leadership among the Idaw Tanan of the Western High Atlas, Morocco. Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology Department, University of California at Los Angeles.

Jemma, D.

1971 Les tanneurs de Marrakech. Algiers: Centre de Recherches Anthropologiques, Prehistoriques, et Ethnographiques.

Mannheim, Karl

1971 From Karl Mannheim. Kurt H. Wolff, ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mauss, Marcel

1966 Essai sur les variations saisonnieres de societes Eskimos: Etude de morphologic sociale. In Sociologie et anthropologic. Marcel Mauss, ed. pp. 389–477. Paris* Presses Universitaires de France.

Merad, Ali

1967 Le reformisme musulman en Algerie de 1925 a 1940. Paris and The Hague: Mouton.

Moore, Sally Falk

1969 Descent and Legal Position. In Law in Culture and Society. Laura Nader, ed. pp. 374–400. Chicago: Aldine.

Pacques, Viviana

1971 Les fetes du Mwulud dans la region de Marrakech. Journal de la Societe des Africanistes41: 133–143.

Renan, Ernest

1887 Discours et conferences. 5th ed. Paris: Calmann-Levy.

Runciman, W.G.

1970 Sociology in its Place and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scheffler, Harold W.

1965 Choiseul Island Social Structure. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Schneider, David M., and Raymond T. Smith

1973 Class Differences and Sex Roles in American Kinship and Family Structure. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Shils, Edward

1975 Center and Periphery: Essays in Macrosociology. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Smith, W. Robertson

1919 The Prophets of Israel and Their Place in History to the Close of the Eighth Century A.D. London: A. and C. Black.

Troeltsch, Ernst

1960 The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches. New York: Harper and Row.

Turner, Bryan S.

1974 Weber and Islam: A Critical Study. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

© Dale F Eickelman 1977

[1] This paper is based on fieldwork in Boujad, Morocco, and its environs from October 1968 until June 1970. It was sponsored by the Foreign Area Fellowship Program and the National Institute of Mental Health, to whom I am deeply grateful. Additonal fieldwork ensued in the summers of 1972 and 1973 and was sponsored, respectively, by the Foreign Currency Program of the Smithsonian Institution and the Social Science Research Council. The transliteration of Arabic terms in this text is based upon colloquial usage. The plurals of most Arabic words are indicated here by the addition of to the singular forms, except for those few which frequently occur in Western literature. However, to avoid awkward circumlocutions, the maraboutic descent group discussed in this paper are Sherqawi in the singular and adjectival forms, Sherqawa in the plural, as they are in Arabic. Because of publishing economies, I have been unable to indicate emphatic consonants by the use of special transliteration marks. For comments on this paper I wish to thank Karen I. Blue, T.O. Beidelman, Nicholas S. Hopkins, and especially Richard P. Werbner.

[2] Although rarely used as such marabout is an English word. I deliberately use this term rather than saint to avoid facile analogies to the Christian context. Although both North African marabouts and the saints of Mediterranean Europe serve as intermediaries to the supernatural and frequently are associated with specific places and clientele, they occur in significantly different cultural contexts which cannot usefully be equated, as Turner has persuasively argued (1974: 56–71).

[3] For similar analogies concerning saints in the European Mediterranean, see Boissevain (1966: 30–31) and Christian (1972: 44).

[4] The acquisition of clientele independent from immediate ecological considerations continues to be the case. In recent years a Boujad Sherqawi active in electoral politics (when they are possible) has successfully sought maraboutic status in certain villages in the Sus area and has collected substantial donations. These are provided in part by wealthy Casablanca merchants who originate from these villages and seek to facilitate their business enterprises in return. Other villagers sought to become his clients on the basis of less practical “religious” ends.

[5] This baraka, as these attributes are popularly considered, can be acquired equally from kinsmen and nonkinsmen. The “closeness” through which these qualities are transmitted is frequently envisaged in highly concrete terms in maraboutic myths. In one case, bread is prepared by a marabout and eaten by his disciple. In another instance, a Sherqawi child sucks the fingers and toes of a sleeping marabout.

[6] I specify currently because a number of other sons of the marabout are recognized, some of whom have shrines in Boujad. Both in the past and today, Moroccans recognize the possibility of other descent groups being “discovered” (or sociologically speaking, of descent groups crystallizing out of descent categories).

[7] For a further discussion of these brotherhoods, see Eickelman (1976: 224–227).

[8] The same descriptive term designates pilgrims who visit maraboutic shrines.

[9] A similar process takes place in the formation of urban quarters (Eickelman 1974b). By rough calculation, there is a maraboutic shrine for every six square kilometres, or one for every 150 persons, on the western plains of Morocco. Comparable figures prevail for the High Atlas mountains (Berque 1957: 7). It is futile to place much faith in such a census, but it does indicate the prevalence of maraboutism. Of course, the vast majority of such shrines draw only miniscule offerings and clientele.

[10] Because Jacques Berque’s interpretation of maraboutic cults is the most prominent one in French literature on Morocco, it is useful briefly to analyze it here. While Gellner relies upon the logically elegant imagery of segmentation to describe “tribal” social structure, Berque elaborates a botanical metaphor to conceptualize Moroccan social forms, especially those of High Atlas Berbers. For Berque, these forms resemble “a hopelessly tangled undergrowth, formed of miniscule twigs, with the roots of each extending to all points of the horizon” (1953: 263). Having extracted full value from the botanical metaphor, Berque proceeds to an incendiary one to describe historical shifts in the distribution of power: “tribal hegemonies, personal power, spiritual or dynastic expansion flame up and die out like torches. Their radiation lacks depth. It is spread out over a milieu diverse and diffuse at the same time, fragmented but universal” (1953: 269). Berque sees maraboutic cults as an integral part of Moroccan social identity from at least the eighteenth century to the present (1953: 270). The title of the article, “Qu’est-ce qu’une ‘tribu’ nord-africaine” is probably meant to evoke Renan’s “Qu’est-ce-qu’une nation?” (1887) and thus suggests the significance which Berque attributes to the study of “tribal” social identities. Unfortunately, however, his general argument, as opposed to his Ethnography of the Seksawa (1955), is limited to a presentation of his key metaphors and an analysis of prior scholarly assumptions toward local and tribal identities. Yet in various other writings, Berque acknowledges the persistence of maraboutism in diverse historical and social circumstances (e.g. 1949: 82–84; 1957).