Dasa Bombjakova

The Role of Public Speaking, Ridicule, and Play in Cultural Transmission among Mbendjele BaYaka Forest Hunter-gatherers

Differences between Yaka in Bangui-Motaba and Djoubé

There is regular loss of intervocalic /l/ in Bangui-Motaba

Pronunciation Guide| IPA Symbol

Introducing Mbendjele BaYaka/Pygmies

On Language and Metaphors Herein

“Mosambo” Pleads and Gives Advice

“Massana” — Multiplicity of Play/Ritual

Some Remarks on History and Economics

Ethnic and Linguistic Background

3 FIELDWORK METHODS & CHALLENGES

Balancing Participation and Observation

“Child”, “Adult” and “Forest” in Discourse of Ripening

On Seeing, Doing, Entering, and Following

People Ripen in Their Own Ways

On Deliciousness and Beauty, Noises, Emptiness and Rotting

Sharing Too Much Wisdom Also Leads to Emptiness

“There Are No Bad Children” even if They Grow into Rudeness

“Togetherness” and “Togetherness Passed”

Adulthood or “Being of Enough”

Elipid - Bilo Public Discussion Forum

Mosambo About and for Children

Encouragements to do as requested, showing off and failures to share

Lack of Participation in the Economic Production

Interactions with Non/Mbendjele

Physical and life/and/death impacts of mássáná

lloko enters Djoubé - Everyone Works towards Ripeness

Massana Structured Games - Inculcation of Mbendjele distinct values

9 CONTRASTING “RIPENING” WITH ORA

Outsider/imposed Education in Congo

ORA Methods and Data/collection

Perspective of ORA instructors

Children reasons for liking and disliking the school

ORA imitation games - children's copying strategy

ORA is un/growing people: Contrasting ORA Teaching Practices with the Mbendjele view on ripening

PART ONE - DISCUSSING SOCIAL LEARNING

Mbendjele views on social learning

Contribution to the Debates on Social Learning Processes

Contribution to the debates on modes of cultural transmission

Consolidation of Relations between Humans and Other Beings

PART THREE: SUMMARISING CHAPTERS

Chapter 5 — On Mbendjele Life-Cycle

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

The Role of Public Speaking, Ridicule,

and Play in Cultural Transmission

among Mbendjele BaYaka Forest

Hunter-gatherers

Dasa Bombjakova

A thesis submitted for partial fulfilment for the

Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

In the

Department of Anthropology

UCL

Supervisor: Dr Jerome Lewis

2018

[Declaration]

I, Dasa Bombjakova, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis.

ABSTRACT

This thesis is based on ethnographic research conducted with Mbendjele BaYaka Pygmy hunter-gatherers of Likouala Region, Congo-Brazzaville for eighteen months from 2013 to 2015. The primary goals of this thesis are: (1) to present three key contexts for educating children about Mbendjele practices and values; (2) to analyse ethnographic observations of how these contexts are employed to distinguish the modes of education they exploit; (3) to contrast Mbendjele and outsider-imposed education methods, and how Mbendjele define proper and improper teaching and learning.

Mbendjele BaYaka value three main pro-egalitarian, cultural institutions as the primary means of educating children. They are based on public speaking, ridicule and play. I will examine how these institutions are employed in practice with a discussion of content and context. The results indicate that Mbendjele value mostly transmission of pro-egalitarian values, shaping understanding of gender and sexual roles in children, and teaching ways to deal with Non-Mbendjele outsiders. Corporal punishment is rare amongst egalitarian hunter-gatherers. Despite Mbendjele perceiving of it as an improper way of disciplining children, it is often employed in sedentarized context, in conjunction with increasing domestic violence and alcoholism.

Indigenous institutions for cultural reproduction are central to understanding how hunter-gatherer picture their own future. Despite good intentions foreign enforcement of institutional schooling can have negative affects on the cultural resilience of Mbendjele sociality and egalitarian values. Understanding how Mbendjele value outsider imposed and their indigenous education institutions contributes to a better understanding of cultural resilience among marginalised ethnic groups, such as Mbendjele.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT | 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS | 4

LIST OF TABLES | 7

LIST OF FIGURES | 8

LIST OF PLATES | 9

ORTHOGRAPHY AND PRONUNCIATION | 10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS | 15

INTRODUCING MBENDJELE BAYAKA/PYGMIES | 19

ON LANGUAGE AND METAPHORS HEREIN | 24

Child-rearing and Human Development in the Cultural Context of “èkôndjî”

(JOINT PARENTAL RESPONSIBILITY) | 26

Môsâmbô, MÔÂD3Ô, màssânà | 36

SoME REMARKS oN HiSToRY AND ECoNoMiCS | 48

ETHNiC AND LiNGuiSTiC BACKGRouND | 53

3 FiELDWoRK METHoDS & CHALLENGES | 64

BALANCiNG PARTiCiPATioN AND oBSERVATioN | 64

METHoDS oF LANGuAGE LEARNiNG | 71

“CHiLD”, “ADuLT” AND “FoREST” iN DiSCouRSE oF RiPENiNG | 79

BASiC TERMiNoLoGY oF RiPENiNG | 81

oN SEEiNG, DoiNG, ENTERiNG, AND FoLLoWiNG | 86

PEoPLE RiPEN iN THEiR oWN WAYS | 89

GUARDIANS OF SPECIALISATIONS | 92

ON DELICIOUSNESS AND BEAUTY, NOISES, EMPTINESS AND ROTTING | 94

SHARING TOO MUCH WISDOM ALSO LEADS TO EMPTINESS | 96

“THERE ARE NO BAD CHILDREN” EVEN IF THEY GROW INTO RUDENESS | 101

5 ON MBENDJELE LIFE-CYCLE | 104

EKÎLÂ, ÈKÔND3Î, MÀTÉNÀ | 104

MOTHER’S AND CHILD’S BIRTHING | 117

“TOGETHERNESS” AND “TOGETHERNESS PASSED” | 142

ADULTHOOD OR “BEING OF ENOUGH” | 148

6 MÔSÂMBÔ | 154

Môsâmbô Style and Protocols | 154

Elîjnîô - Bilo Public Discussion Forum | 181

MÔsÂMBÔ ABoUT AND FoR CHILDREN | 184

Encouragements to do as requested, showing off and failures to share | 185

Making a Disorder | 188

Lack of Participation in the Economic Production | 192

Mbendjele-Bilo conflicts | 193

sexual Behaviour of children | 196

7 MÔÂD3Ô | 209

Describing MÔÂD3Ô | 209

Coalitionary môàdjô | 219

Gender-competition Môàdjô | 229

Children’s MÔÂD3Ô | 233

MÔÂD3Ô TO AND FOR CHILDREN | 238

Independency | 240

Non-sharing | 243

Interactions with Non-Mbendjele | 244

8 MÀssÂNÀ | 253

Spirits are children, too | 255

Physical and life-and-death impacts of màssànà | 257

On participation & feedback | 260

ILÔKÔ ENTERS DJOUBÉ - EVERYONE WORKS TOWARDS RIPENESS | 266

Growing up playing | 269

Màssânà Structured Games - Inculcation of Mbendjele distinct values 273

9 cONTRASTiNG “RiPENiNG” WiTH ORA | 283

OuTSiDER-iMPOSED EDucATiON iN cONGO | 283

ORA - “OBSERVE, THiNK, DO!” | 284

ORA METHODS AND DATA-cOLLEcTiON | 287

PERSPEcTiVE OF ORA iNSTRucTORS | 287

ORA imitation games - children ’s copying strategy | 293

PART 1 E - DiScuSSiNG SOciAL LEARNiNG | 300

Mbendjele views on social learning | 300

Contribution to the Debates on Social Learning Processes | 303

Teaching | 303

Participation | 306

Contribution to the debates on modes of cultural transmission | 307

Study Limitations | 310

PART 2 O - OTHER OBSERVATiONS | 311

On (Un)Ripeness | 311

Reflections on Noise | 312

Fullness of Participation | 314

Consolidation of Relations between Humans and Other Beings | 315

PART 3 REE: SuMMARiSiNG cHAPTERS | 316

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Bantu nominal class prefixes | 12

Table 2 Defining “ripening” | 22

Table 3 Modes of cultural transmission by Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman (1981) | 35

Table 4 Some examples of my active participation within màsàmbà, mààdfà, and màssànà | 67

Table 5 Examples offieldwork challenges in Pygmy hunter-gatherer publications | 73

Table 6 List ofprevious researchers in Djoubé | 75

Table 7 “Child” and “adult” in the Mbendjele discourse of ripening | 80

Table 8 Mbendjele terminology of social learning processes | 88

Table 9 Expressions for noise and disorder | 95

Table 10 Children as noise and disorder producers - some of the symptoms of emptiness | 96

Table 11 Ekondfi-like believes in Central African hunter-gatherers | 106

Table 12 Vocabulary of care-taking | 126

Table 13 Expressing agreement with the speaker | 157

Table 14 Expressing disagreement with the speaker | 158

Table 15 Some examples of French and Lingala expressions in màsàmbà | 158

Table 16 Examples of insults in màsàmbà | 159

Table 17 Goals and characteristics of màsàmbà | 175

Table 18 Examples of èliplô discussions | 182

Table 19 Màsàmbà and èlip'iô compared | 183

Table 20 Màsàmbà discussing problems with children | 185

Table 21 Mààdfà goals | 210

Table 22 Demands to start and end mààdfà | 211

Table 23 Audience encourages performers | 212

Table 24 Audience communicates with audience | 213

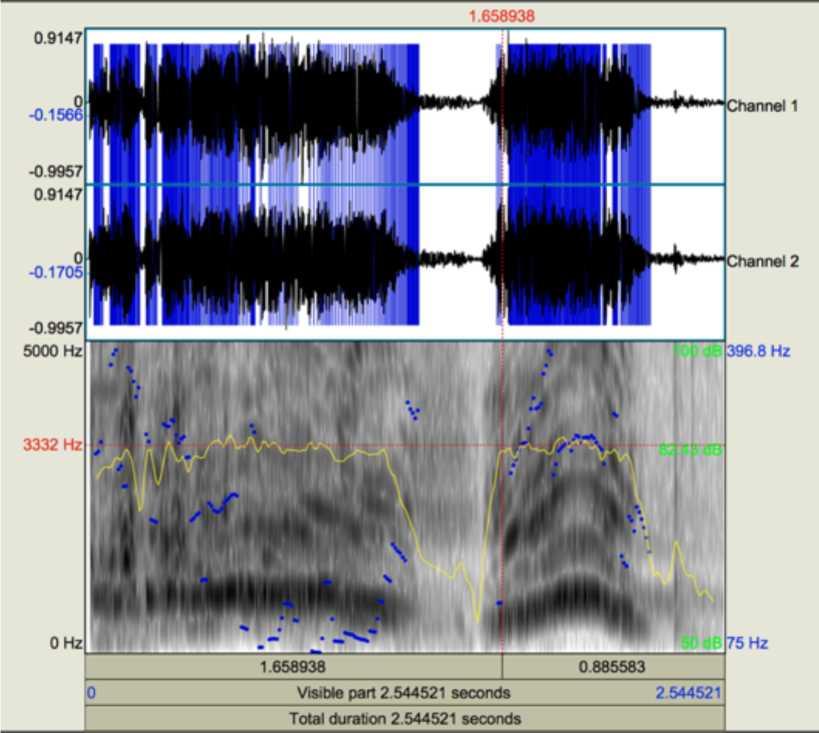

Table 25 Sounds accompanying mààdfà re-enactments | 214

Table 26 Desirable and undesirable emotional reactions to normative mààdfà | 217

Table 27 Examples of manifestations offemale group solidarity | 224

Table 28 Female beauty-enhancing strategies | 230

Table 29 Female collective strategies in securing male’s nutritional provisioning and

infant care | 231

Table 30 Some Mbendjele sayings containing the expression of massana | 254

Table 31 ORA data-collection summary | 287

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Boko with his daughter Bs | 17

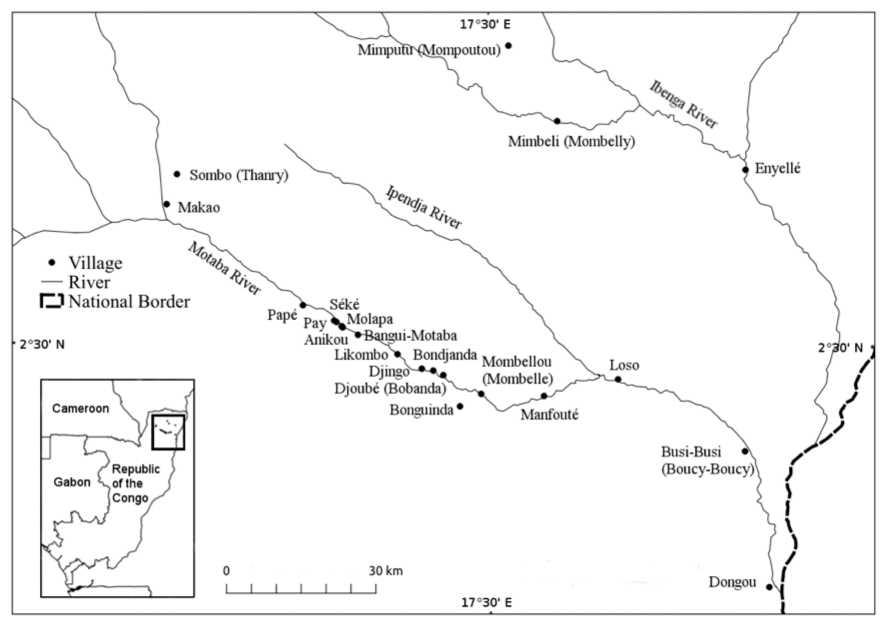

Figure 2 Map of the research area, Likouala, Republic of Congo | 47

Figure 3 The “big” Bilo | 57

Figure 4 Mbendjele girls at the “route nationale” | 60

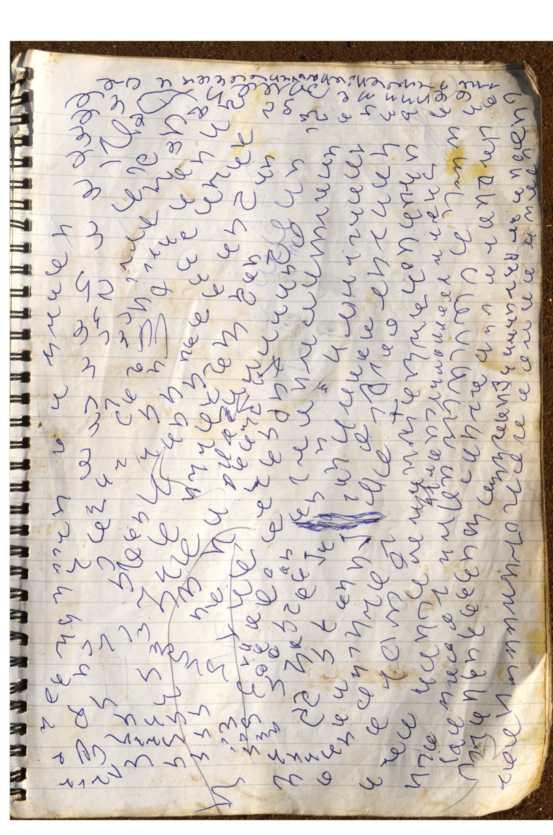

Figure 5 Pointlessness of writing | 66

Figure 6 Mbuma | 78

Figure 7 Young Mbuma | 78

Figure 8 “Bad children don't exist!” | 103

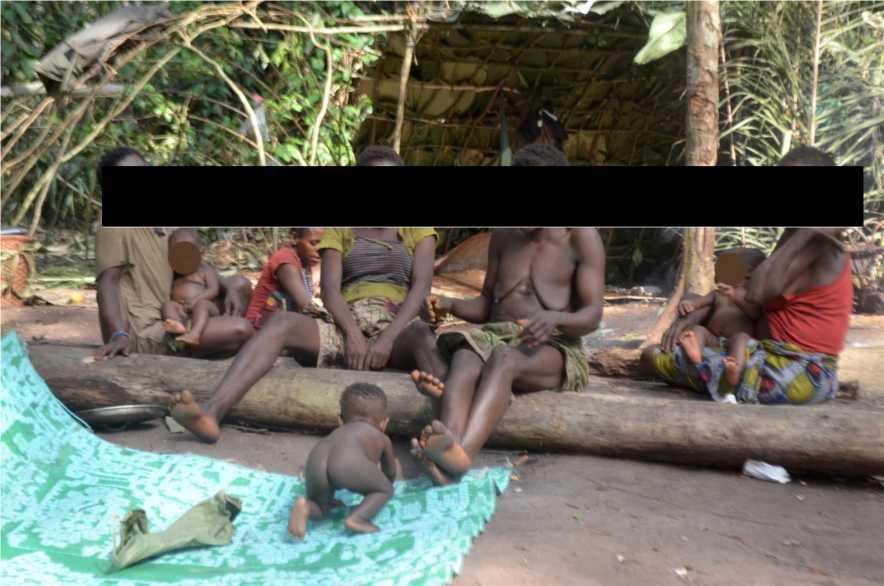

Figure 9 Childless woman breastfeeding | 112

Figure 10 Pretending birth-giving | 119

Figure 11 Mapwanda - baby full of healthiness | 121

Figure 12 My molo child - an Mbendjele Dasa | 124

Figure 13 Toddler make-up | 125

Figure 14 About birth-spacing | 128

Figure 15 Kumu's symptoms of ekondfi | 131

Figure 16 Activities in the forest | 135

Figure 17 Activities in the village | 136

Figure 18 Adolescents flirting | 140

Figure 19 Children’s intimate games | 140

Figure 20 ingdlo | 141

Figure 21 BotSls secures husband’s love | 145

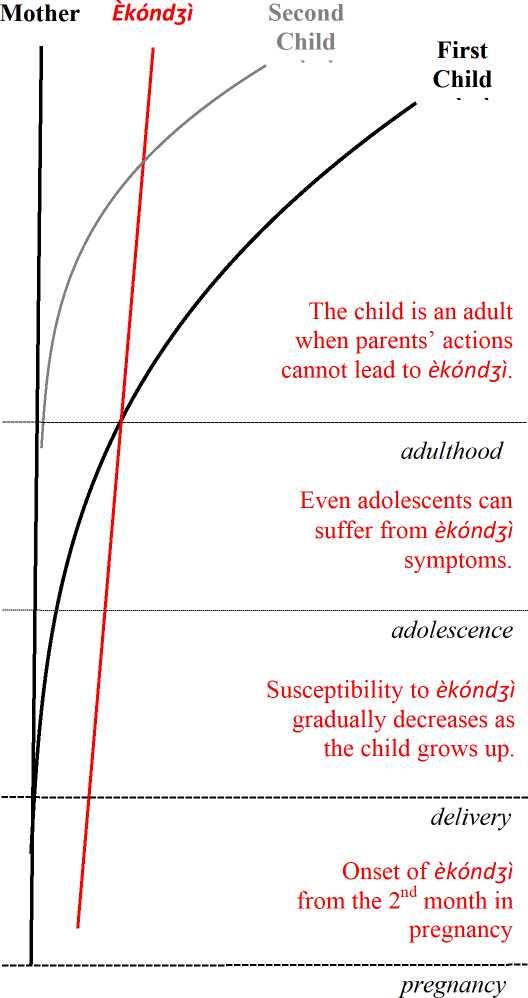

Figure 22 Child development through lens of ekondfi | 150

Figure 23 Conflict-resolution tree | 176

Figure 24 Example offemale conversations | 225

Figure 25 Female beating tools | 226

Figure 26 PataJpata | 227

Figure 27 Example of female synchronised chorusing | 228

Figure 28 Boys’ physical intimacy | 236

Figure 29 Djingo with her daughter Bs | 239

Figure 30 Mbuma’s demonstration and instruction of boys in performing mokond'i massana | 265

Figure 31 Cocoa breasts and babies | 270

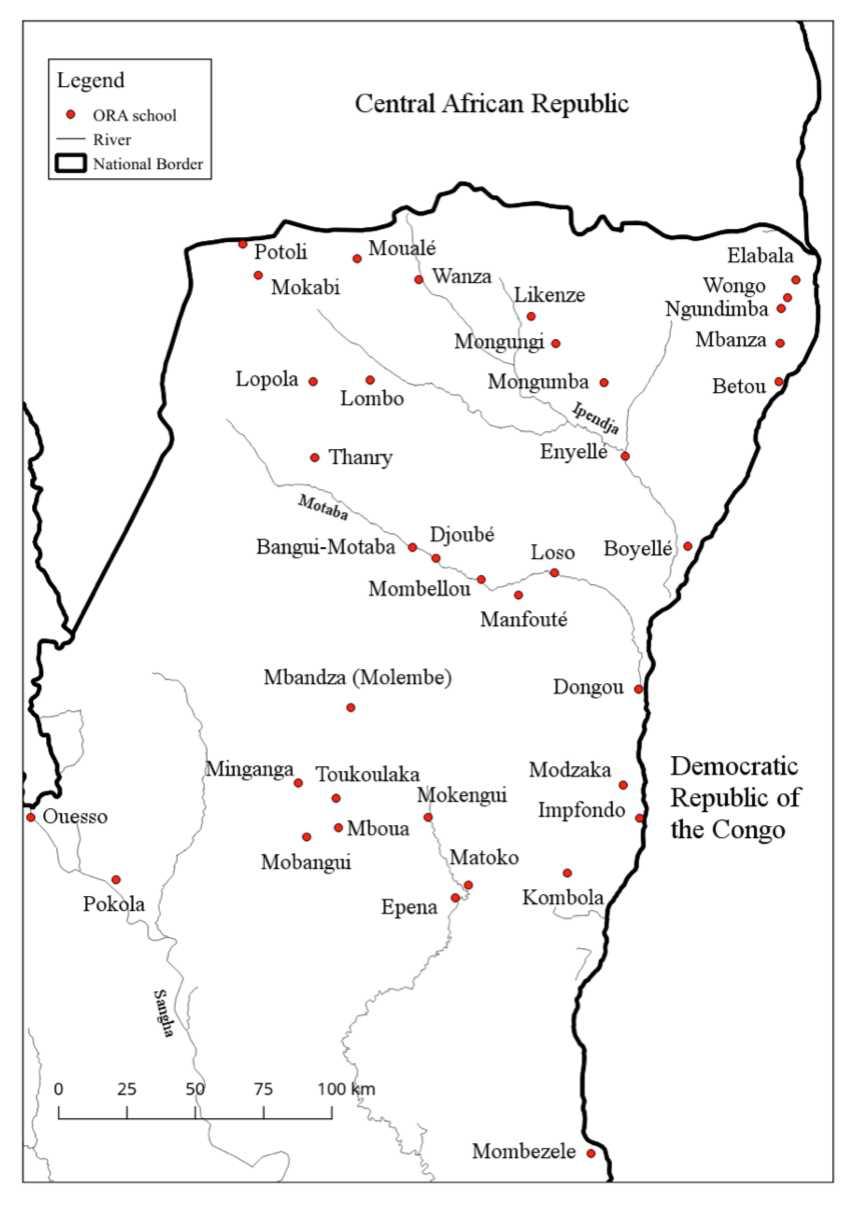

Figure 32 Map of ORA schools in Sangha and Likouala Departments (2015) | 285

LIST OF PLATES

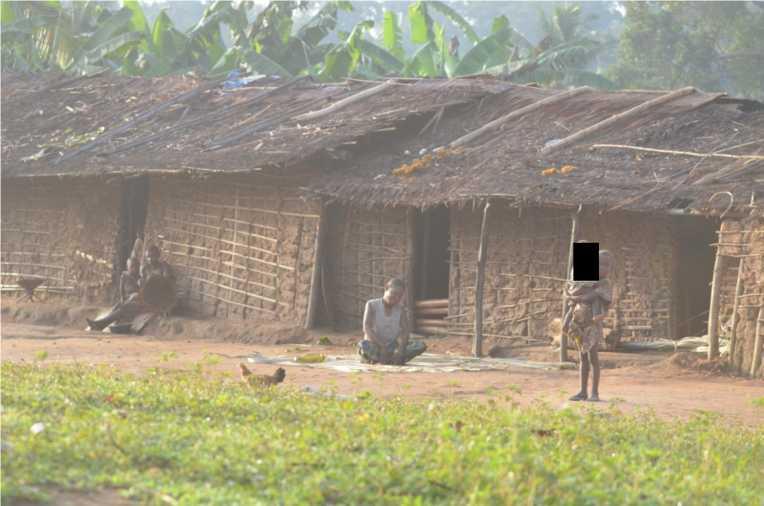

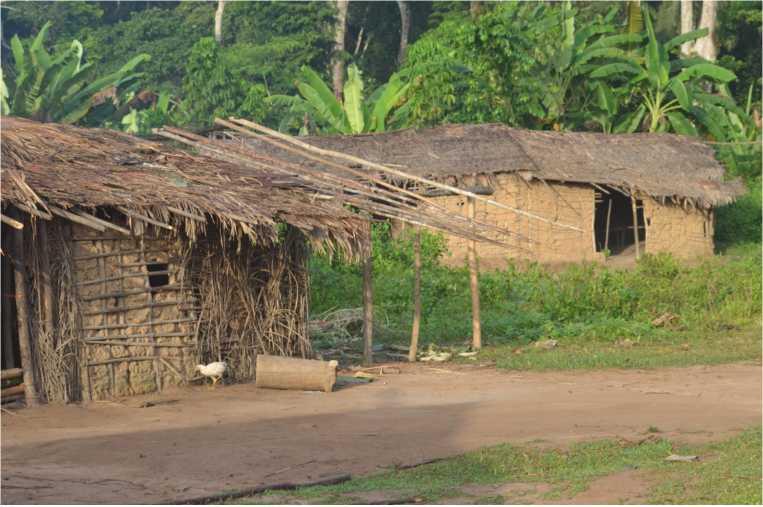

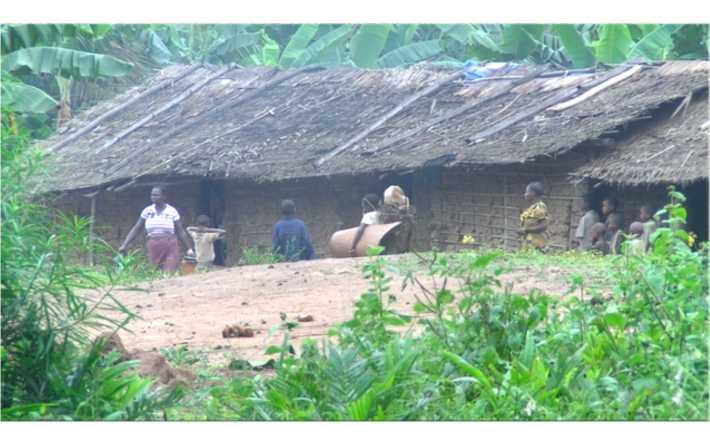

Plate 1 After mosambo | 167

Plate 2 Mosambo — the issue of Milo and her “stolen” cassava | 177

Plate 3 Example of coalitionary moadjo | 221

Plate 4 Botsls and Mbuma lavish Mosuku | 264

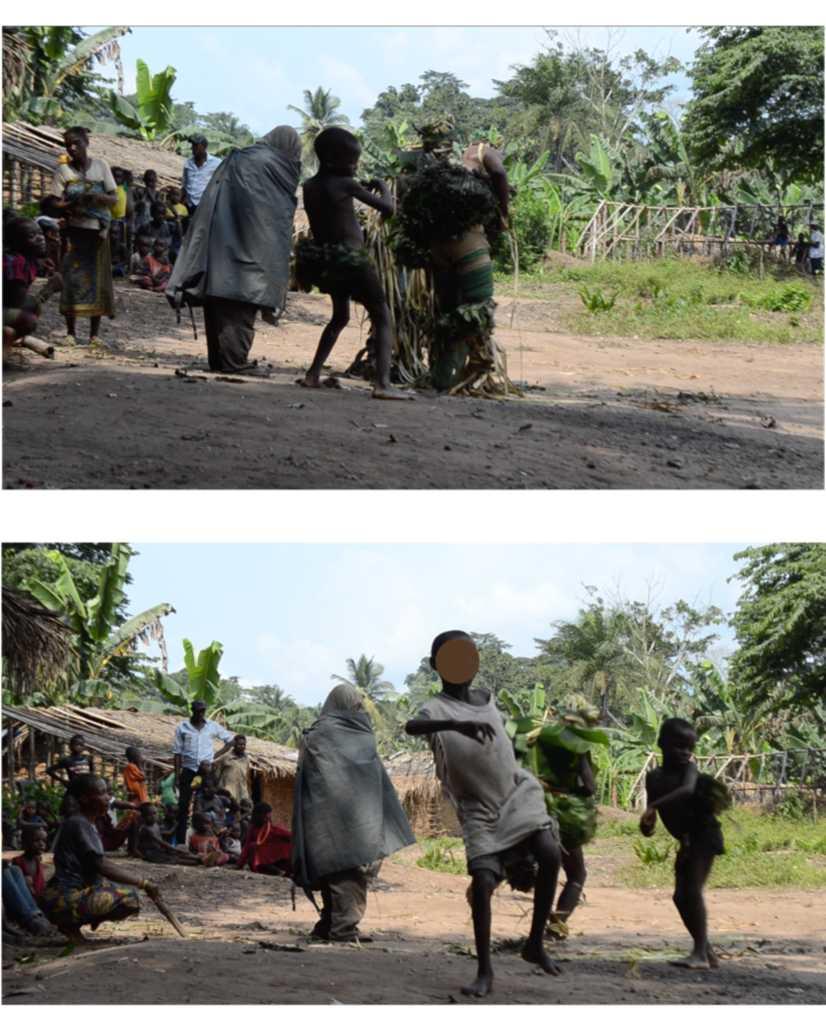

Plate 5 Training lloko | 267

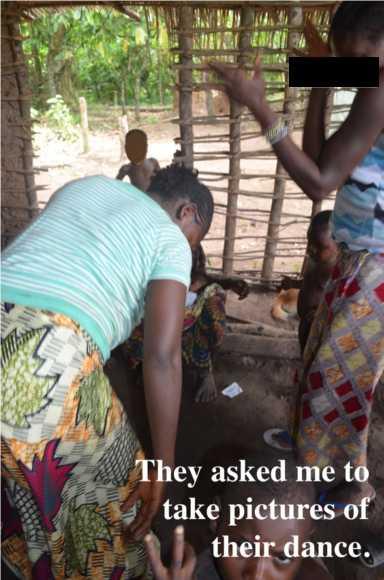

Plate 6 Real lloko mokondl massana event | 268

Plate 7 Toddlers and mokondl massana | 271

Plate 8 Djoube - between unripeness and ripeness | 272

Plate 9 EtundS na koko | 274

Plate 10 Explaining elanda | 277

Orthography and Pronunciation

The employed glossing style follows Leipzig Glossing Rules: Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses (Comrie et al. 2015). I was also inspired by socio-linguistic studies of (Y)Aka language (mainly Combettes & Tomassone 1978;

Duke 2001; but also Thomas 1988; Thomas et al.eds 1993a, 1993b, 1998, 2003a, 2003b, 2004, 2005), and grammar of Bantu languages (Demuth 2000; Nurse 2008;

Nurse & Philippsoneds 2003; Schroeder 2008). During the process of transcribing I was guided by professional linguist Benedikt Winkhart (2016, email communications, May- November).

List of Abbreviations

| 1PL | First Person Plural | FUT | Future |

| 1SG | First Person Singular | GER | Gerund |

| 2PL | Second Person Plural | IMP | Imperative |

| 2SG | Second Person Singular | IPA | International Phonetic Alphabet |

| 3PL | Third Person Plural | LG | Lingala |

| 3SG | Third Person Singular | MY | Mbendjee Yaka |

| CAUS | Causative | NEG | Negative |

| DEM | Demonstrative | ORA | Observer, Reflechir, Agir |

| BM | Bangui-Motaba | POSS | Possessive |

| DIST | Distal | PRF | Perfect |

| DISTR | Distributive | PROX | Proximal |

| DJ | Djoube | PRS | Present |

| EMPH | Emphasis Marker | PST | Past |

| FR | French | RED | Reduplication |

| SUBJ | Subjunctive |

General Rules

-

Original text appears on the first line, linguistic glossing on the second line, and English translation on the third line:

original text

glossing

‘English translation’

-

A dash (-) represents a morpheme break.

-

A dot (.) means that there is more than one morpheme, but they cannot be said apart.

-

Every segment in the original text line is matched by one segment in the glossing line.

-

If the translation consists of several words, those are glossed with a dot (.) inbetween.

-

If one English word is presented by two Mbendjee Yaka words, I use greater-than sign (>).

-

No punctuation marks are used in the glossing line.

-

English translation is marked with a set of single punctuation quotation marks: (‘’).

Yaka and Other Languages

Quotations of informants’ natural speech are in three languages: Mbendjee Yaka, Lingala, and French. French examples follow the rules of written French. If an informant uses non-standard version of French words, I indicate the correct orthographic form in square brackets:

mostivation [motivation] ‘motivation'

For Mbendjee Yaka and Lingala I use IPA phonetic symbols. If Mbendjele informants employ French or Lingala words, I indicate it in the square brackets - [FR] for French, and [LG] for Lingala. Borrowed French words are written phonetically and the standard French word is indicated in square brackets after colon punctuation mark [FR:French.word]. Borrowed Lingala words are also written phonetically, and in the glossing line I indicate its nominal noun class:| mÌ2^gwa | dèsà |

| 4Fsalt[LG:mungwa] | already[FR:déjà] |

| ‘salt’ | ‘already' |

Faunal and Floral Species

If informants refer to concrete names for faunal or floral species, I do not acknowledge that within glossing line. If identified, the name of the species is written in Latin in a footnote.

mè2ló

4Fwatery.yam ‘watery yams'1

1 Dioscoreophyllum cumminsii (STAPF) DIELS

àmé | I |

| 1SG & 2SG | sinó^é | we (dual) inclusive | ||||

| 1SG & 3SG | sinai | we (dual) exclusive |

|

2SG | 1 T ' | ' T L |

O$8, a$8 | you |

| 3SG | ys | he, she, it |

| 1PL | buss, busi | we |

| 1SG & 2PL | ' ' ' sins nu | we inclusive |

| 1SG & 3PL | sins bo | we exclusive |

| 2PL | buns | you |

| 3PL | bsns | they |

Nominal class system

A Bantu noun class is a group of particular nouns - mostly semantic grouping, such as humans, animals, animates, inanimates, long things, round things - any such feature can be a characteristic of a certain noun class.

Table 1 Bantu nominal class prefixes

Some classes are entirely singular; some are entirely plural. A corresponding singularplural pair makes a gender, like mo-na (class 1) and ba-na (class 2) in the table below. Thus, class 1 and 2 make a gender.

| Class | Prefix | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| 1 | mo- | mo-na | 1-child | ‘child’ |

| 1 | 0- | kombe ti | l.elder | ‘elder’ |

| ba-na | 2-child | ‘children’ | ||

| 2 | ba- | |||

| ba-kombe ti | 2-elder | ‘elders’ | ||

| mo- | mo-mbebe leke | 3-wrinkle | ‘wrinkle’ | |

| 3 | mu- | mu-pda | 3-mouth | ‘mouth’ |

| A | me - mbe be leke | 4-wrinkle | ‘wrinkles’ | |

| 4 | me | me-poa | 4-mouth | ‘mouths’ |

| di- | d-iso | 5-eye | ‘eye’ | |

| 5 | di-solo | 5-break | ‘break/pause’ | |

| [low voicing] | gano | 5.sung.fable | ‘sung fable’ | |

| m-iso | 6-eye | ‘eyes’ | ||

| ma-solo | 6-break | ‘breaks’ | ||

| 6 | ma- | ma-kano | 6-sung.fable | ‘sung fables’ |

| ma-sopo | 6-earth | ‘earths’ | ||

| ma-kiki | 6-eyebrow | ‘eyebrows’ | ||

| md-^umd | 6-home | ‘homes’ | ||

| e-kiki | 7-eyebrow | ‘eyebrow’ | ||

| 7 | A | <em>' | L ~ ’</em> |

e-wesu | 7-bone | ‘bone’ |

| e- | e-bebu | 7-lower.lip | ‘lower lip’ | |

| be- | be-wesu | 8-bone | ‘bones’ | |

| 8 | be - | be-be bu | 8-lower.lip | ‘lower lips’ |

| 9 | 0- | _ L _ L sopo | 9.earth | ‘earth’ |

| tyuma | 9.home | ‘home’ | ||

| bo-lingo | 14-love | ‘love’ | ||

| 14 | bo- | bo-mo | 14-fear | ‘fear’ |

| bo-bina | 14-dance | ‘dance’ |

Just like French has the two genders feminine and masculine, Yaka has genders like 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, 7/8, 3/5, 3/8 and 5/8, other gender pairings in Aka should be inchoate, meaning they hold only few exceptional cases. A noun class is defined by the according agreement class. The noun itself with its respective prefix is called head noun class, but a head noun class does not define a class without agreement. An agreement class is defined as the set of other words that take an according affix to mark grammatical agreement with the head noun. A perfect example of class agreement would be:| Bó-nà | bà-sónì | bà-bólè | bà-dìé | nd5. |

| 2Fchild | 2Fsmall |

‘Two small children are | 2Ftwo

over there.’ | 3PLFbe.PRS | DEM.DIST | However, Mbendjee Yaka is exceptionally flexible in dropping head noun prefixes (Duke 2001). In that case the subject agreement marker on the verb is the only indication of the subject. The following example illustrates five different versions of the same phrase:| ÒQÉ | dìé | mò-tò | mò-pìé. |

| 2SG | be.PRS | 1Fperson | ^beautiful |

| ÒQÉ | ò-dìé | mò-tò | mò-pìé. |

| 2SG | 2SGFbe.PRS | 1Fperson | ^beautiful |

| Ò-dìé 2SGFbe.PRS Ò-dìé 2SGFbe.PRS |

ÒQÉ

2SG

‘You are a beautiful person.’ | mò-tò

1Fperson mò-pìé.

1Fbeautiful mò-pìé.

1Fbeautiful | mò-pìé.

| beautiful |

Ideophones & Expletives

Given the complexity in distinguishing ideophones (or ideophonic adverbs) from expletives/interjections (Beck 2008; Dingemanse 2012; Kilian-Hatz 2006), I only provide lexical meanings of such expressions/sensations. One of the features of these sensations is vowel lengthening (Kilian-Hatz 1997). Thus, they can be stretched according to the speaker’s liking. The flexibility in length is expressed by a tie, like in musical notation, indicating that it ‘rings’. For example, the sensation of duration -—' “teeeeeeee” is noted as teee”.

teee

sensation.of.duration

‘for a long time’

These expressions can also be reduplicated to convey the meaning:

té2té2té2té

RED~sensation.of.duration

‘for a long time’

Differences between Yaka in Bangui-Motaba and Djoubé[1]

There is regular loss of intervocalic /l/ in Bangui-Motaba

In the case of front vowels, a glide fills the position between the two vowels:

| DJ | BM | ||

| mbilà | >/l/ >glide> | mbijà | palm seed |

| Míló | >/l/ >glide> | Míjó | Milo |

| Ekilà | >/l/ >glide> | èkijà | taboo |

In the case of back vowels, /l/ is lost and subsequently the back vowel changes into a glide /w/.

DJ | BM

| àbòlé | >loss of /l/> | àbòé | >lenition of /o/> | ábwé | big |

| tàmbòlà | >loss of /l/> | tàmbòà > | >lenition of /o/> | tàmbwà | to walk |

| kéogòlà | >loss of /l/> | kéogòà | >lenition of /o/> | kéogwà | to look for |

Description/Example |

| E | dress [drss] |

| For English-speakers, it is easiest to think of the sound as an f-sound | |

| * | made only with the lips, instead of the upper teeth and lower lip, or a |

| blowing sound. | |

| D | thought [θɔːt] |

| d | geese [giis] in Australian English |

| 3 | vision [ vi3)n] |

| d3 | jam [dʒam]{1} |

| 0 | sing [sig] |

| P | magnifique |

| J | show [[)□] |

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been accomplished without persistent help and support of my supervisor, Jerome Lewis. Thank you, Jerome, for your understanding, for giving me autonomy, and for always being there when I needed it - I deeply appreciate everything you have done for me. Camilla Power played an extremely important role in this journey. Thank you, Camilla, for showing me that I can do more than I could think of.

My special thanks goes to my very good friend Carlos Fornelino Romero, who spent with me eight months in the field and assisted me during my fieldwork. I deeply appreciate your help and support and your interpretations of events, but also for a goodquality audio-visual data that you have collected and taught me about so much.

This work would not have been possible without all the people that I met in Congo. I would like to thank the government of the Congo-Brazzaville for authorizing my research, and especially to Professor Clobite Bouka Biona and Mr Serge Ngouabi for all their efforts in getting all the necessary permits.

My special thanks goes to Lee Johnston Junior who saved my life when I was fighting severe malaria. Thank you again, Junior, it would not have been possible without you!

On my regular journeys from the forest to the nearest towns of Thanry and Pokola, I met a lot of people who helped me and gave me support. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Marianne Reimert and Nicolas Nijhof, at that time based in Pokola, for their warm dinners and invaluable medical advice. Last but not least to Simon Malela and his family and friends, who regularly offered me their shelter and food.

I would like to thank to Benedikt Winkhart for his invaluable advice on linguistic transcription and to Freddie Weyman and Dayna Dawson, who provided me with their commentaries and proofread earlier versions of this work.

My biggest thank you goes to all Mbendjele families that opened their hearts and allowed me to live and work with them. Especially I thank Mbuma who took seriously my desire to understand Mbendjele womanhood and motherhood and my deep interest in understanding issues of rearing children. From many of my Mbendjele friends, I must also mention AQela, Batsls, Djemeni, Andjele, S5p5, Nlslsks, B5k5ba, B5k5, Mab5ta, B5bila. Also children, with whom I shared lots of times of joy and play. Among many: Kw5na, Adiambo, Aijganda, Djambando, Samedi, M'lsala, Mb5l5, Kakandj'i, Bemba, and Anise.

1 INTRODUCTION

[[][Figure 1 B5k5 with his daughter Bé

KombEti a ^5<f)d.

1.elder 3SG talk.PRS

‘Elder talks.’

Mo2to | na | mo2to | na enda y2i.

1Fperson | with | 1Fperson | about 7.thing 7FDEM

‘Person with person about this thing.’

Mo2to | na | mo2to | na | enda | ya | nda.

1Fperson | with | 1Fperson | about | 7.thing | 7.POSS | DEM.DIST

‘Person with person about that thing.’

KombEti | Qatpa | bona.

1.elder | talk.PRS | like.that

‘Elder talks like that.’

KombEti | Qatpa | mo2nda1, | ba2to | b2a | mboka | ba | aka.

1.elder | talk.PRS | 3Fissue | 2Fperson | 2FPOSS | 5.village | 3PL | listen.PRS

‘Elder talks issue, people of his village listen.’

B&to | ba | 5ka | bo | ye | a | kaba | nd5.

2Fperson | 3PL | listen.PRS | that | 3SG | 3SG | share.PRS | DEM.DIST

‘People listen what he shares.’

Ba2to | ba | 5ke | m^ndi | nd5.

2Fperson 3PL | listen.SUBJ | 4Fissue | DEM.DIST

‘People listen to those issues.’

B&na | ba | gadie, | b&na | ba | gadis,

2Fchild | 3PL | other | 2Fchild | 3PL | other

‘Other children, other children:’

Dka! | Dka | me2ndi | ndi!

listen.IMP | listen.IMP | 4Fissue | DEM.DIST

Listen! You listen to the issues!’

Dka | me2ndi | 1^6 | mo2sambo!

listen.IMP 4Fissue 4FPOSS | 3Fpublic.speaking

‘Listen issues of the mosambo.’| Jka! | Jka! | Jka!

listen.IMP | listen.IMP listen.IMP

‘Listen! Listen! Listen! Listen!’ | Jka!

listen.IMP | |

| B&na <strong><em> | ba | dls | na</em></strong> |

2Fchild | 3PL | be.PRS | with

‘Children have unripe heads!’ | me2suku

4Fhead | bud!

9.hardness |

Introducing Mbendjele BaYaka/Pygmies

Before explaining B5k5’s words, I will introduce him. Boko comes from a village called Bangui-Motaba, situated in north-eastern Republic of Congo. In the picture, he is posing with his daughter Be - a long-awaited first child of Boko and his wife D^mgö. Boko is a proud Yaka man.

BaYaka (in plural) are hunter-gatherers of the Congo Basin. They are also known by the name “Pygmies”. Recent studies estimate that there are as many as 920,000 Pygmies living in Central Africa (Olivero et al. 2016: 9) In general, there are four main Pygmy groups: The Western group (Gyeli, Bongo, Kola, Zimba, Aka, Baka), Eastern group - Mbuti (Efe, Asua, Sua, Kango), Twa group (Tua, Toa, Cwa, Boone, Langi, Chua) and the group of BaYaka. In Republic of Congo, there are several different Yaka groups: Aka, Luma, Mikaya, Ngombe, Baka, and Mbendjele (Köhler & Lewis 2002).

Literature-wise, Mbendjele were referred to by different names: People of the Forest, People of the spear, the Little people, People of the dance (Auteroche 1961: 22), Babinga (Bruel 1899; Hauser 1954), Yandingas (Douet 1914), Akowa, Akka (Schweinfurth 1874), Achua (Burrows 1898), Bibaya (Despois 1946) Biaka (Kisliuk 1998), Babenga (Regnault 1911), Bambenga, BaMbenzele, or Babenzele (Bahuchet 2012; Despois 1946).

Such as it is with many hunting and gathering societies (Ikeya & Ogawaeds 2009), all contemporary Yaka groups maintain relationships with “village-dwelling”(Köhler & Lewis 2002: 280) people. They were also called Negroes, Tall Blacks, farmers (Bahuchet & Guillaume 1982; Hattori 2014; Patin et al. 2009), Bantu (Ngima Mawoung 2001), the Village People (Turnbull 1961), cultivators (Kitanishi 1995) shifting cultivators (Hanawa 2004; Komatsu 1998), neighbours (Bonhomme et al. 2012), nonPygmy neighbours (Joiris 1994, 2003), agricultural neighbours (Kitanishi 2003), neighbouring farmers (Matsuura 2011; Takeuchi 2005) or by the language they speak (Grinker 1990, 1994; Hattori 2006; Matsuura 2006; Rupp 2003; Yasuoka 2012).

Boko normally refers to himself as Yaka, but to distinguish himself from other Pygmy groups, he calls himself Mbendjele. Yaka is an Mbendjele self-ascribed endonym, equivalent to “Pygmy” (Köhler & Lewis 2002). Boko refers to all the “village-dwelling”

Non-Pygmy Africans as Bilo (in singular Milo). Throughout this thesis I will follow B5k5's perception (also employed in the work of Kisliuk 2000; Lewis 2002; Noss 1995). This reflects an emic view that posits a radical cultural distinction between forest people (BaYaka) and village people (Bilo), firstly described by Turnbull (1976). By employing this distinction I avoid ascribing names that would refer to the people’s modes of subsistence, language they speak, or whether they are “tall” (Köhler & Lewis 2002: 281). However, it does not necessarily mean that “the forest people” would spend most of their time in the forest and “the village people” most of their time in the village. As explained by Lewis:

“[...] even where forest people no longer have access to forest, even where they speak the same language and have many cultural practices and beliefs similar to those of their farmer neighbours, these ethnic oppositions do not break down.” (Lewis 2002: 53).

On Egalitarianism

There are three key cultural values and practices that influence lives of the Mbendjele: egalitarianism, demand sharing, and personal autonomy (Hewlett 2016: 2). Woodburn made the distinction of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies as immediate-return and delayed-return in respect to people’s work effort which yields either immediate or delayed results (Woodburn 1982). While for example gathering is considered as immediate as it brings food ready for immediate consumption, farming is delayed, as the time must be spent in order to yield subsistence later. In Woodburn's terms, Mbendjele have an immediate-return economic system - they are present oriented and consume most of their production as soon as they produce it.

Immediate-return systems produce the: “closest approximation to equality known in any human societies.” (Woodburn 1982: 431). Such societies are not egalitarian “merely by default” (Béteille 2010: 456). As Woodburn further puts it: “The verbal rhetoric of equality may or may not be elaborated but actions speak loudly: equality is repeatedly acted out, publicly demonstrated, in opposition to possible inequality.” (Woodburn 1982: 432).

Egalitarianism permeates domains of gender, age, and politics (Barry S. Hewlett 2016b: 3). Mbendjele females are autonomous, have active political voice, participate in group’s decision-making, are economically independent from males, have control over their sexual and reproductive bodies, and equal decision in marriage. Amongst the Mbendjele, menstruation is not considered as a sign of female inferiority, tendencies of which were argued elsewhere (Leacock 1978: 247).

Egalitarianism is not “sameness”. While most of their days females engage in gendered, qualitatively different activities - these differences are not valued hierarchically. For instance, the activity of hunting is not considered as more valuable than gathering. As Endicott explained: “There can be many differences in what men and women do in an egalitarian society. What makes it egalitarian is how the activities are controlled and culturally valued.” (Endicott 1981: 2).

While Mbendjele acknowledge the variations in skills and abilities of individuals, they impose egalitarian economic relations through actions that force them to share with anyone who asks. These actions lead to immediate consumption, and prevent accumulation and saving in Mbendjele society. Everyone has the right to demand material objects, and demand sharing is a key way to get material objects. Demand sharing is an institution of distribution and a tool for promoting egalitarianism. This distribution system is recipient controlled. It is the right of members of the group to demand and it is the obligation of donor to give (Lewis 2002; Peterson 1993). Demand sharing is not a simple form of reciprocity, but the “means of both recognizing equality and achieving it.” (Lewis 2002: 237). Mbendjele also value personal autonomy, which means that noone can coerce others, or tell them what they should do, including children (Barry S. Hewlett 2016a: 2).

Thesis’ Goal

Mbendjele egalitarianism shows remarkable persistence despite being surrounded by societies with hierarchical political systems and facing strong discrimination (Bouquiaux 2006; Dehoumon 2011; Lewis 2002, 2005a, 2005b, 2014a; Moise 2011; Woodburn 1997, 2005). According to Woodburn, egalitarianism of immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies persists for: “number of reasons... but one of the major ones is certainly the fact that the systematic nature of their immediate-return institutions makes such a transition [from egalitarian to hierarchical] very difficult for them to accomplish whatever their wishes.” (2002: 16).

This thesis contributes to understanding persistence of the Mbendjele society by a focus on cultural reproduction processes occurring through three Mbendjele social institutions. Social institutions are elements of a social system (Barnard 2004: 210) - e.g. bride service is an institution of kinship system, and màsàmbà mentioned by Biki above is an Mbendjele social institution of a political system (Lewis 2002: 76). While this thesis makes some contribution to our understanding of transmission of egalitarianism - its primary concern is cultural reproduction processes (also known as social learning).

A key aim of this thesis is to offer an Mbendjele account for this cultural persistence through a detailed examination of key cultural institutions such as màsàmbà that they see as crucial for transmitting key cultural values and knowledge down the generations. Biki S quote above grasps the essential goal of this thesis: How people ripen? And How do Mbendjele seek to promote ‘ripening’ of their children? Before moving on to the discussion on how “ripening” sets in the wider literature, it is necessary to define it (see Table 2).

Table 2 Defining “ripening”

| Definition: |

| human development; |

maturing;

growing up;

transition from being immature to being mature

becoming more intelligent, “less hard”, “fuller”, “bigger”, “sweeter”, “redder” |

| Informed by: | ||||

| Key Cultural Values | Perceptions on ripeness / unripeness | Child-rearing beliefs & practices | “wisdom-sharing & taking” (teaching & learning) | Play |

“Ripening” here could be interpreted as a gradual process of maturation, joyful development of both body and mind, which can be enhanced and encouraged by proper means of wisdom-sharing/taking and play. While ripening refers to human development and maturation, wisdom sharing and wisdom taking could be interpreted as teaching and learning.

*

Before moving on to a further discussion of the main aims of this thesis, it is necessary to clarify what influenced the nature and scope of this thesis. During my Master Degree in social anthropology at Comenius University Bratislava, I was interested in understanding cultural transmission. By testing predictions of dual-inheritance theory, also known as geneculture co-evolutionary theory (Boyd & Richerson 1988; Richerson & Boyd 2005), I examined how one’s reputation is influenced by biased transmission of social information - gossip (Henrich & Gil-White 2001). The fieldwork took place in a Western society, in my own maternal tongue (Slovak), and with people of approximately my age - students.

When I began this PhD, I wanted to continue with something familiar, given the challenge of conducting fieldwork in foreign language, in a non-Western, egalitarian, and hunting-and-gathering society. This seemed as a promising idea, since before my departure to the field, there were only two publications concerning cultural transmission among Congo Pygmy hunter-gatherers: “Cultural Transmission among Aka pygmies” by Hewlett & Cavalli-Sforza (1986) and “Social learning among Congo Basin huntergatherers” (Hewlett et al. 2011a). Since then, however, the studies of cultural reproduction increased in popularity (Boyette & Hewlett 2017a; Gallois 2015; Gallois et al. 2017; Bonnie Lynn Hewlett 2013; Hewlett et al. 2011a, 2016, Sonoda 2014, 2016a, 2016b; Terashima & Hewletteds 2016).

This thesis’ approach differs from these studies in two regards. Firstly, I present and describe the Mbendjele metaphors concerning social learning and cultural reproduction. Secondly, I explore how these metaphors are lived, experienced, and applied, through analysis of social learning within the context of Mbendjele cultural institutions - described by my informants as vital for Mbendjele cultural reproduction.

The following seeks to sow these “metaphors” and “lived experiences” into scholarly theoretical grounds, and present how these fields are bridged and inter-related for purposes of the analysis of “ripening”, as hinted on by B5k5.

On Language and Metaphors Herein

All “Pygmy” languages relate either to Niger-Kordofanian or Nilo-Saharan languages. According to Bahuchet (2006), Pygmy communities speak three languages that are not shared with their neighbours: the Bantu language Aka, the Ubangian language Baka, and the Central Sudanic language Asua. According to Guthrie’s (1948) classification system of Bantu languages, Mbendjele speak “Aka” language, categorised as Bantu C10. Among linguists, there was a debate as to whether this language should be referred to as “Aka”, or “Yaka”, which arose from the fact that /y/ in “Yaka” is due a: “phonological rule which inserts a glide where is no consonant onset to a syllable.” (Duke 2001: 10), as well as it reflects: “regional accents and the popular tendency to drop consonants in normal speech.” (Köhler & Lewis 2002: 280).

Throughout this thesis, I use “Mbendjee Yaka” to refer to the language employed by my informants. The expressions of “Mbendjee” or “Yaka” were used interchangeably in reference to their language. By referring to this language as “Mbendjee Yaka”, I avoid confusion with a different Bantu language known as “Yaka” B31, while remaining faithful to Mbendjele emic terms and to scholarly traditions at the same time (“Mbendjee” in the work of Lewis 2002, 2009; and “Yaka” in the works of Kosseke & Kutsch Lojenga 1996).

I heavily use transcriptions and transliterations of informants’ expressions and metaphors. While language transcriptions can be useful in terms of portraying Mbendjele-specific style of communication, presenting its aesthetic quality, manifesting its diversity and richness, and enhancing possibilities for future comparative research - and these are of importance, too - my primary focus lies in presenting the social meanings of people’s expressions, taking its linguistic and ethnographic features as unified, inseparable elements of analysis. This implies the importance not only of the words’ meanings per se, but also how they are utilised, lived, and experienced within the context of people’s everyday lives and in relation to and with one another and with the environment they live in.

Understanding meanings of Mbendjele expressions, as presented here, could not have been achieved solely by studying language in isolation from its social context, e.g. by studying “Aka” lexicon textbooks, or by “hunting and gathering” words’ meanings through explicit interviews, but only through a combination of these with a long-term body and mind participant observation, and shared, co-living experiences with the studied community.

Specifically, metaphors herein should not be viewed conventionally - as: “exaggerated, embellished and exotic language, which can be contrasted with, and distinguished from, the lucidity, precision and literal, everyday, language.” (Smith & Hoefler 2017: 160). They also should not be seen as mere “beliefs”, “products of mind”, or “social constructs”. Instead, they should be understood as “positional truths”, as they are: “conceptually, ontologically and experientially valid and thus true.” (Poirier 2013: 5960). From an Mbendjele perspective, they are true in the mind and the body, in the thought and in the lived, too.

In other words, the metaphors here are presented as “windows” to my informants’ conceptual and experiential world, similar to previously elaborated work by Nurit Bird- David (1990) about Nayaka, and concerning the Mbendjele and other Yaka, in the work of Lewis (2002) and Köhler and Lewis (2002).

Köhler and Lewis interpreted Yaka “core” or “root” metaphors of animals, plants, and humans as living beings in a shared world (ibid: 299), while remaining interactive - there is no prioritisation of “human body or human social institutions” (ibid: 299). “Yaka animal metaphors for human beings point to qualities they share as a resource and/or in their behavior and attitudes to the forest and to others.”

Accordingly, forest is abounding source of analogies for “ripening” processes in plants, animals, and humans, without prioritization one over another. While Köhler and Lewis (ibid) were specifically addressing the Mbendjele conceptual world in relation with Bilo, the metaphors of ripening are also situated within this framework - these metaphors relate to each other by having common core foundation - Yaka intimate, aesthetic, and emotional relationship with “the forest”.

Concerning translation, I agree with Bird-David in that: “while the translation itself is not problematic, that very fact may obscure divergent cultural perspectives and ontologies. It produces a sense of obviousness which allows the readers to insert their own native intuitions and understandings.” (2008: 525). In an attempt to eliminate possibilities of this “sense of obviousness”, in translating key Mbendjee Yaka terms into English, I added another layer of analysis - I deconstruct literal meanings of key terms, while juxtaposing them with their social uses and meanings and with definitions offered by scholars interested in similar issues. In other words, I will look into these Mbendjee Yaka terms to infer their literal meanings; and will look “out” at how these terms are utilised, and see how they relate or not with scholarly terms.

To understand Mbendjele concepts of human development, it is necessary to present and examine their child-care practices and beliefs. The following bridges scholarly traditions of child-oriented studies concerning Central African hunter-gatherers and their child-rearing techniques and child-care beliefs, and situates my contribution to this specific field of study.

Child2rearing and Human Development in the Cultural Context of “ekondfi” (joint parental responsibility)

Early work of Margaret Mead (1990), and later John and Beatrice Whiting (Whiting 1963; Whiting & Whiting 1975) and their students (Harkness et al. 2010; Harkness & Supereds 1996; LeVine 2007; LeVine et al.eds 1998a, 1998b; LeVine & Neweds 2008) raised questions of cross-cultural variability in childhood, and questioned Western trends of universal human development and then the “universal child” (Montgomery 2009: 3). These universalistic theories were majorly built on Piaget’s, Vygotsky’s, and Freud’s psychological studies (LeVine 2007: 249-250).

The interest in studying hunter-gatherer children and childhoods sprouted in 1960s, after “Man the Hunter” symposium (1968) and after the work of James Woodburn on Hadza, Richard Lee on San and Colin Turnbull on Mbuti, as summarised by Hewlett & Lamb (2005: 5). Bowlby’s attachment theory and proposition of evolution of childhood within EEA (Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness), which focuses on motherinfant attachment as a necessary pre-condition for children to grow into emotionally and socially healthy adults, was questioned by Melvin Konner, Patricia Draper and Nick Blurton-Jones and sparked further interest in studying hunter-gatherer childhoods (ibid).

The stress on cross-cultural variability of childhood and human development continues to be one of the major issues in socio-cultural anthropological studies of childhood and human development (Lancy 2015; Montgomery 2009; Tudge 2008). While the studies of Whitings and their students included hunter-gatherers in their analysis, there were tendencies in calling them “pre-industrial”, or “traditional” (Hewlett & Lamb 2005: 4), and thus including them into same analytical categories with farming or pastoralist societies. Scholars whose primary interest lies in studying hunter-gatherers, conducted a number of studies to discern hunter-gatherer child care practices with those of the farming or pastoralist populations (Fouts et al. 2005; Hewlett et al. 1998, 2000; Hewlett & Lamb 2002; Hewlett & Roulette 2014).

Contemporary nomadic immediate-return hunter-gatherer childhoods and child-care practices show striking similarities (for reviews see Hewlett & Lambeds 2005; Konner 2010, 2016; Narvaez et al. 2014). While acknowledging some differences, too (see also Hewlett 1996 for Central African hunter-gatherers), these child-care practices are largely highly indulgent, responsive, and child-oriented. Melvin Konner (Konner 2005, 2010, 2016) has analysed and sheltered them under HunterJGatherer Childhood model (HGC), embracing close physical contact, maternal primacy and dense social context, indulgent and responsive infant care, and variable but higher than cross-cultural average paternal care (ibid 2016: 201).

Central African hunter-gatherer infant and child care practices have been of great scholarly interest in recent decades. The issues of Aka paternal investment, fatherhood, and father-infant bonding was addressed by Barry S. Hewlett (1991a, 1997), scholars were also interested in infant care practices (Hewlett et al. 1998; Meehan et al. 2017), weaning (Fouts et al. 2001, 2005, 2005), as well as alloparenting and multiple caregiving (Hewlett 1991b; Hewlett et al. 1998, 2000; Hewlett & Lambeds 2005; Meehan 2005, 2009; Meehan et al. 2017).

Most of these studies draw on time-allocation data-collection to follow infant and child care behaviours, combined with ethnographic interviews about the specific domains of child caretaking to reveal people’s reasoning or ideologies concerning their infant and child care behaviours (Fouts et al. 2005; Hewlett 1991a; Hewlett & Roulette 2014; Hewlett & Winn 2014; Meehan 2005). These scholars have emphasised that “behaviours” and “ideologies” are both important in understanding hunter-gatherer infant-care, and that the “ideologies” in particular are crucial in understanding what drives people for this hunter-gatherer-specific indulgent care giving. For example, in terms of understanding Aka fatherhood, Hewlett (1991a: 107) remarked that: “understanding of ideology is essential because it directs human actions.” Similarly, Tronick et al. (1987: 97) emphasized that: “caretakers draw on knowledge that is culturally based. These strategies are extremely valuable.” Fouts et al. (2012: 124) noted that: “there is ample evidence that breastfeeding and weaning practices are guided by cultural beliefs about children’s development and maternal states.”

I address these issues from a methodologically different approach - by focusing on metaphor-informed ethnography based on participant observation. My contribution to the understanding of ideologies and beliefs that encompass infant and child care draw from these previous studies concerning “Pygmy” child care - as discussed above - while integrating them with the Mbendjele concept of ekila, defined and described by Lewis (2002: 103-120, 2008).

Ekila, herein phonetically “ekllá”, is an Mbendjele poly-semic complex system of beliefs, that can refer to: “menstruation, blood, taboo, a hunter’s meat, animals’ power to harm humans, and particular dangers to human reproduction, production, health, and sanity.” (2008: 298). Lewis further remarks that ekllá: “establishes hunting and childbirth as prototypical activities, defining people as men and women, and weaves these roles together in a complex set of interrelationships that serve to counter the strong tendency towards autonomy and fluidity in association.” (ibid: 312).

Specifically, my interest lies in those aspects of ekllá which are associated with pregnancy, birth, child care, child development, and which link child’s, mother’s, and father’s well-being and health, crucial to understanding human development - herein “ripening” processes. In the Yaka literature, these beliefs are majorly linked to “dangers of reproduction” or “childbirth complications” (Lewis 2008: 298) - “ekondi” (ibid), “ekundi” (Hewlett et al. 1986: 53), herein “ékóndfi”. I argue that ékóndfi beliefs are anecdotally, but fairly richly represented in the ethnographic, anthropological, and ecological record concerning different Yaka groups, even though they often employ different expressions to describe them (e.g. “ekoni” ,“eke”, “kuweri”, “llmbl”, “behe” in Hattori 2006; Ichikawa 1987, 1998; Sato 1998; Soengas López 2010; Tanno 1981; Terashima 2001) or these expressions are absent in the scholarly record, but yet authors provide descriptive examples of similar beliefs (Agland 2012; Aunger 2004; Carpaneto & Germi 1989; Fouts et al. 2012; Gallois 2015: 106; Hattori 2006: 46;

Leonard 1997: 41; Pagezy 1990: 89; Turnbull 1961: 121).

Without attempting to diminish the importance of people’s individual life-histories (B. L. Hewlett 2012); biological, environmental, historical, political contexts or the interplay of biology, ecology, and culture (Hewlett 2016) that can inform, mould, and impact infant and child-care practices, too, I argue that ekond^i beliefs can explain how and what drives Mbendjele for highly responsive and indulgent child care, symptomatic of “pan-hunter-gatherer” (Meehan et al. 2017: 215) child care characteristics (Konner 2005, 2005, 2010, 2016; Narvaez et al. 2014). Previous studies emphasised how core cultural values, “cultural models” or “foundational schemas” of egalitarianism, sharing, and personal autonomy pervade these practices (Hewlett 2014). Ekond^i, however, naturalises indulgent child-care, and its strength also lies in its explanatory power when these practices are not followed.

Similar to Lewis’s approach in describing “ekila” (2008), I am taking on an ontogenetically-informed course in explaining how ekond^i is woven into people’s everyday realities, since ekond^i means something different for not-yet-born child, toddler, adolescent, or adult. I will also explain that ekila and ekond^i inform the perception of one’s reaching adulthood, or using Baki's words “ripeness”. I draw on ethnographic observations of child-care practices and on how people reasoned about them, as well how they explained people’s “failures” and consequences in (non)following prescribed child care practices.

According to my informants, the ripening can be promoted by appropriate “wisdomsharing”, which is bound by specific characteristics and specific contexts, which are seen as vital for these enhancements. The following is an overview of “wisdom-sharing oriented” studies - studies of social learning.

Social Learning

Culture is transmitted through various social learning processes[2] - processes that contribute to one’s learning through social interactions with others. On the other hand, asocial learning is a type of learning acquired through trial-and-error, individually. Play, participation and observation, teaching, and imitation are major social learning processes (Caro & Hauser, 1992; Crittenden, 2016; Gaskins & Paradise, 2009; Hewlett et al., 2011; Whiten 2017). This thesis focuses on the role of two of these processes Mbendjele social learning - teaching and participation.

While social learning studies in Pygmy groups as well as in other hunter-gatherers increased in popularity among scholars in recent years (Boyette & Hewlett 2017b; Gallois 2015; Gallois et al. 2017; Bonnie Lynn Hewlett 2013; Hewlett, Hillary N.

Fouts, et al. 2011; Hewlett et al. 2016; Sonoda 2014, 2016a, 2016b; Terashima & Hewlett eds 2016), as Hewlett & Roulette pointed out: “little is known about how cultural beliefs and institutions influence the nature, frequency and effectiveness of teaching.” (2016: 12). This thesis aims to address this gap and further our understanding of Congo Basin hunter-gatherer views of social learning. Questions that I address here include: What are Mbendjele views on how culture is reproduced? What are (un)desirable ways of learning? Are there emic categories for teaching and learning? Are there domain-specific ways of learning and teaching?

However, this is not to claim that scholars would not hint on indigenous views of social learning: “Biyaka parents [say] the primary duty of young children is to play. In fact [if] children do not play, they will fail to learn anything” (Neuwelt-Truntzer in David F Lancy 2016: 179). Jarawa hunter-gatherers believe that children should be free to pursue their interest, because adults believe that it is: “the surest path to learning.” (Pandya 2016: 193).

Studies conducted in hierarchical farming societies have shown that nature and employment of teaching and other social learning processes can depend on people’s understanding of growing up and how children are understood as learners (Harkness et al. 2010; Harkness & Supereds 1996; Lancy & Grove 2010a; Rogoff 2003). For instance, Village Learning Model proposed by Lancy and Grove (2010a) presents that in certain societies children are not being taught because they are seen as uneducable, lacking sense, or incapable of learning. These authors, however, discuss mostly hierarchical and sedentary farming societies. In terms of hunter-gatherers, Inuit children are perceived by adults as lacking reason and they are not allowed to employ teasing as adults do (Omura 2016: 272). One of the questions to address here is: How do Mbendjele construct learning capabilities of children? Are children “educable”?

Lancy suggested that some societies proscribe teaching, deeming it harmful as the teaching in a form of instruction can be seen as “infringement” to child’s autonomy (2016). Similar views are held by and Inuit: “direct instruction of children and teenagers is rare because they are assumed to learn what they need to know spontaneously as they mature into reasoning. adults. [It is] absurd to teach, scold, or get angry with children because they have not developed reason.” (Omura 2016: 278279). Nayaka hunter-gatherers actively refrain from instructing, on an example of hunting traps - but that this does not mean that children would be excluded from knowledge about hunting (Naveh 2016: 128). A similar was made among the Aka hunter-gatherers of Congo Basin: “[...] parents also seemed to restrain themselves to minimize their teaching intervention with infants. For instance, in one episode an infant was cutting food rapidly with a knife as a parent sitting next to her watched, but the parent intervened for only a few seconds to adjust the infant’s arm and never said anything during the episode.” (Hewlett and Roulette 2016: 12).

Cautious restrain from instruction was seems to be shared amongst hunter-gatherers cross-culturally (Lew-Levy, Lavi, et al. 2017: 26). However, there are many types of teaching, not instruction only. Instruction that takes on a form of commands (Boyette & Hewlett 2017), instruction in a form of explanation - either verbal or a demonstration. Another type of teaching is evaluative feedback, either positive (e.g. praise, or making simple approving sounds) or different forms of negative feedback, such as teasing, shaming, scolding, criticism, or even a corporal punishment. Another form of teaching is a formal education as is employed in institutions-schools (Barry S. Hewlett 2016b). In this thesis I will address what types of teaching Mbendjele distinguish and if they posses emic terms for these processes of social learning. Also I will look into what forms of teaching Mbendjele employ within the institutions of mbsambb, mbad^b, and massana.

One of the debates concerning teaching is that it does not exist in the small-scale, traditional, or pre-industrial societies (Csibra & Gergely 2011; Garfield et al. 2016; Hewlett & Roulette 2016). Fiske’s (1997) unpublished monograph about “lack of teaching” was particularly impactful (Csibra & Gergely 2011: 1152). Cultural anthropologists continue to emphasise that teaching in small-scale societies is rare (Lancy & Grove 2010b; Lave & Wenger 1991; Paradise & Rogoff 2009; Rogoff 2014; Rogoff et al. 2003) or even non-existent (Lancy 2010). The debate of its existence and non-existence in small-scale societies continues (David F. Lancy 2016a, 2016b), even thought recent studies show strong evidence that varieties of teaching types are employed in small-scale hunter-gatherer studies (Boyette 2013; Boyette & Hewlett 2017b, 2017a; Garfield et al. 2016; Hewlett et al. 2011b; Hewlett & Roulette 2016; Lew-Levy, Lavi, et al. 2017; Lew-Levy, Reckin, et al. 2017).

This polarity of views stems from diverse definitions of “teaching” as such - as the claims of ‘lack of teaching’ were based on the stereotyped understanding of teaching as explicit, Euroamerican-like and direct, or instructive teaching (Csibra & Gergely 2011: 1152; Hewlett & Roulette 2016: 2). For instance, Lancy defines teaching as “active and systematic intervention of a teacher whose goal is to change the behaviour of a learner.” (Lancy 2010: 98). Resembling formalised teaching in Western schools, it is unsurprising that such form of teaching does not exist in small-scale societies (LewLevy, Reckin, et al. 2017).

By defining teaching to instances when“an individual modifies her/his behaviour to enhance learning in another,” Hewlett and Roulette (2016: 4) found regular instances of several types of teaching in Aka Pygmies: natural pedagogy, demonstration, task assignment, positive and negative feedback and opportunity scaffolding. The authors coded teaching behaviours that were videotaped in a naturalistic setting. While one of the questions they were addressing was the existence of teaching, they made a major contribution to our understanding of teaching in Congo Basin hunter gatherer society. The results show, that for example teaching is often very brief and thus, easy to be missed while recording these behaviours simply by an observation in the field. Hewlett & Roulette have also shown that different types of teaching occurred in different domains of knowledge or a skill. For example, demonstration was the most common teaching style of social norms and values, negative feedback was used to address social norms and values and positive feedback was employed in teaching how to dance and

sing. This study however, accounts for infants and does involve teaching of older children or adults.Employing the same working definition of teaching to cross-cultural analysis of social learning processes employed in hunter-gatherer societies, Garfield et al (2016: 30) found that teaching was the most common process of social learning in across various cultural domains. Within this thesis I will employ this definition of teaching.

While I agree with Hewlett & Roulette (2016) in that socio-anthropologists downplayed the role of teaching in small-scale societies by over-emphasising informal social learning - and this thesis does not attempt to do so either - the expressions that these authors employ provoke for nuanced definitions of teaching-like and learning-like processes. For example, “learning guided by others”, “facilitating learning”, “encouragements” (Lancy 2010; Lancy & Grove 2011). Nuanced, culturally-sensitive definitions of teaching are necessary - I will summarise Mbendjele types of teaching in the final discussion of this thesis.

Observation and participation were emphasized as one of the key social learning processes in small-scale societies (Lancy & Grove 2010a, 2010b; Paradise & Rogoff 2009; Rogoff 2003). Rogoff (2003: 135) coined the term “pitching in” which means children’s participation in adult work. Another type of participatory social learning is learning “by osmosis”: “picking up values, skills, and mannerisms in an incidental fashion through close involvement with a socializing agent.” (2003: 324) typical for learning apprenticeship. Intent participation: “learners attend to in- formative ongoing events that are not necessarily designed for their instruction.” (2003: 324). Intent participation involves keen observation of highly motivated individual.

These participatory approaches to social learning emphasise the role of group or community in facilitating learning/teaching (Gaskins & Paradise 2010; Lave & Wenger 1991; Paradise & Rogoff 2009; Rogoff 2003, 2014). Participation in adult activities gives opportunities for children to refine and develop their skills further. This thesis will also address the question of what role participation plays in the Mbendjele institutions. I agree with Rogoff who argued that: “We need to move beyond studying only individual or dyadic aspects of teaching to a broader, cultural view of interpersonal and community ways of fostering learning, at least for humans.” (Rogoff 2015).

Another issue of great interest in studies of social learning and cultural reproduction concerned the question of from whom people learn. By using means of population genetics, Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman (1981) have demonstrated that transmission of cultural traits is not only “vertical” as in the genetics - from parent to offspring (vertical social learning), but also from and among peers - “horizontal social learning” and from non-biological adults, too - “oblique social learning”. The first study that examined modes of cultural transmission in Central African hunter-gatherers was performed by one of its authors in cooperation with Hewlett (1986). This was motivated by the ambiguous claims of social anthropologists in terms of who is plays more important role in the transmission of cultural traits - parents or that everyone in the camp (Hewlett 2014: 265)?

The researchers (1986) analysed reported Aka transmission pathways in learning specific cultural knowledge and skills (e.g. infant care, hunting, dancing). The study has shown the importance and prevalence of vertical cultural transmission in early childhood, identifying that by the age of 10, children acquire 70% of most skills - both social and survival-related (ibid: 933). This study had a major impact on the studies of cultural reproduction in Congo Basin hunter-gatherers and number of studies since then focused on the modes of transmission of specific cultural traits.

However, authors relied on reported transmission pathways, which can be biased towards vertical transmission, influenced by understanding parents as the first teachers (for discussion, see Boyette 2013). This was shown in the study by Boyette (2013) who found discrepancy between reported and observed cases of transmission of specific cultural traits. While reported accounts emphasised the role of the parents, observational part of the study has shown that it was the oblique transmission that was important during middle childhood and adolescence. In a cross-cultural study of acquisition of hunting skills, Macdonald concluded that both parents and other adults are important in learning hunting (MacDonald 2007). Other scholars pointed to the importance of horizontal transmission in children’s learning ethnoecological knowledge a (Boyette 2013; Gallois 2015) and primacy of children’s peer groups (horizontal transmission) in learning about gender norms and values and subsistent skills (Lew-Levy, Lavi, et al. 2017; Lew-Levy, Reckin, et al. 2017). Recent findings, mainly the cross-cultural study of cultural transmission in hunter-gatherer societies has shown, that while vertical transmission remains crucial in early childhood, it is the oblique transmission that predominates over the life-span (2016: 31), a “two-staged model” (Hewlett et al. 2011a). This thesis contributes also to the discussion on modes of cultural transmission. While I am examining social learning by looking at the the institutions that are based on communal activities and interactions of the group, I will look at the role of a group in the modes of cultural transmission (see Table 3) - does mosambo represent a case of one-to-many cultural transmission given the fact that in mosambo one speaks to many? I will attempt to answer this question as well as explore the role of group in modes of the cultural transmission in mOad^O and massana, too.

Table 3 Modes of cultural transmission by Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman (1981)

| Modes of cultural transmission | ||||

| Vertical parent- to-child | Horizontal contagious | one-to-many | many-to-one | |

| Transmitter | Parent(s) | Unrelated | Teacher / leader/ media | Older members of social group |

| Transmittee | Child | Unrelated | Pupils /citizens / audience | Younger members of social group |

| Acceptance of Innovation | Intermediate Difficulty | Easy | Easy | Very difficult |

| Variation between individuals within population | High | Can be high | Low | Lowest |

| Variation between groups | High | Can be high | Can be high | Smallest |

| Cultural evolution | Slow | Can be rapid | Most rapid | Most conservative |

In summary, this thesis’ scope in terms of social learning can be summarised in the following questions: What are the Mbendjele views on social learning processes? What is the role of teaching in Mbendjele social learning? What is the nature of social learning processes employed in màsàmbà, mààdjà, and màssànà?

Màsàmbà, mààd^à, màssànà

Màsàmbà, mààdjà, and màssànà were acknowledged as important in promoting reproduction of Mbendjele egalitarianism (Lewis 2002, 2014a) and my informants highlighted their importance in promoting people’s “ripeness”. This thesis contributes specifically to understanding how these institutions are employed for teaching and learning, as well as what is being transmitted. I do this with analysis of “real-life” ethnographic instances.

Each of these institutions are defined by their formal and aesthetic characteristics and qualities. Consequently, cultural transmission processes that occur within the contexts of these institutions, can be constrained by the nature of their prescribed form: màsàmbà is a form of public speech, mààdjà are also public events, based on merciless ridicule of other’s silly actions, and màssànà are communal joyful actions of play and ritual (Lewis 2002, 2009, 2014b, 2014a, 2016). This thesis provides a detailed analysis of cultural transmission processes that occur within these institutions.

Contemporary Bantu languages - such as Mbendjee Yaka - continue to carry with some semantic productivity (Demuth 2000: 287; Denny & Creider 2010; Katamba 2006). Thus, the prefixes and suffixes of nouns grasp specific meanings. In this section I will look into the expressions of “màsàmbà”, “mààdjà”, and “màssànà” in an attempt to explain in what ways these words’ literal meanings could be interpreted, and present some examples of how my informants highlighted importance of these institutions in teaching and learning processes. Before doing so, I will introduce each concept in terms of how they were described and analysed within Central African hunter-gatherer publications.

Màsàmbà

Mosambo, herein “màsàmbà”, is an Mbendjele public speaking protocol, a problemsolving, organisational, and pro-egalitarian institution (Lewis 2002, 2009, 2014a). “Through mosambo camp members inform the camp of what they have done, express their opinions, advise camp members, share news of general interest, and seek a consensus, or not, about what the camp will do and who should do what.” (ibid 2014: 231).

While Lewis provided coherent view of the Mbendjele mosámbo, it seems that other Yaka groups have a similar institution. Though mostly briefly, speaking similar to mosámbo was mentioned in Central African Pygmy literature (Combettes & Tomassone 1978: 108-114; Fitzgerald 2011: 49; Guillaume 1991; Gusinde 1955: 24; Heymer 1980: 190-191; Kimura 1990; Leonard 1997: 70; Leonhardt 1999: 261-262; Museur 1969: 153; Soengas López 2009: 195; Thomas & Arom eds 1991: 166; Turnbull 1961; C. M. Turnbull 1965). To mosámbo -like speaking, scholars also have mistakenly referred to it as “council of elders” (Gusinde 1955: 24), or “assembly of elders” (Soengas López 2009: 195).

Thomas et al. (1991: 166) observed that Aka have the same institution with identical name “.sámbo”. The authors remarked that it is often spoken by elders, but that the opinions shared through the speech must represent what most people think, which accords with the observation of Lewis (2002: 79; 2014a: 232) about Mbendjele’s mosámbo.

Often, the discussion or mentioning of the speech emerged when scholars puzzled about the issues of “leadership” and “authority” in Pygmy groups, and seeming counterintuitiveness of an individual (“elder”) who gives advice, and yet he is not necessary listened to. These scholars emphasised the role of the speech in problem-solving and work organisation, while remarking its non-authoritarian nature. For example, Heymer observed about Aka (1980: 190-191; my emphasis): “one of the elders from the various camps functions in some ways as leader, giving advice and suggesting possible courses of action, although decisions are made by common consent, not authoritatively.” (for similar descriptions, see Gusinde 1955: 24; Leonhardt 1999: 261-262).

In a footnote of his paper “Everyday conversations of the Baka Pygmies”, Kimura (2014: 94) stated that Baka have a speech protocol, which is similar to Bongando’s bonango - and bonango shows similarities with mosámbo (ibid 1990) - but he did not provide further information about how Baka refer to this sort of speech. Fitzgerald (2011: 49) mentioned Baka’s “speech act of formal counsel” “kálo”, but did not describe its form, content, nor its functions. Combettes and Tomassone (1978: 108-114) translate and transliterate one example of mosámboJlike speech, but being concerned with the linguistic characteristics of Aka language, authors do not discuss its ethnographic features and meanings. Lastly, Turnbull (1961) seems to hint on these speeches descriptively: “sound trashing” (ibid: 110); “making loud remarks across the camp” (ibid: 121); “loud tirades” (ibid: 41) or “striding up and down across the camp” (ibid: 148).

The importance of public group opinions, discussions, and negotiations in huntergatherer societies was emphasised in terms of social control, problem-disentangling, and maintenance of egalitarian politics (Boehm et al. 1993a: 230; Boehm 2000: 92, 2008, 2012: 856; Boehm & Boehm 2009: 335). For example, Konner (2015, e-book, n.p.) observed amongst !Kung: “There might be three or five or eight adults speaking; participation was optional. Voices were active, sometimes argumentative, sometimes lyrical, and they were usually in both male and female registers. It was open airing of difficulties that, if not solved, could affect everyone.”

However, such events did not receive attention in terms of their “teaching and learning” potential. And yet, in societies without hierarchies, freedom in mobility, and respect for personal autonomy, these public group events create specific opportunities for teaching and learning about the economic production, problem-solving, group organisation, or about “goodness” and “badness” of people’s actions. As remarked by Lewis (2014: 231), mosambo: “also provides a forum for children to learn about social and moral values and about the etiquette ofpublic discussion.” Here I present detailed analysis of how and what is being taught and learned through and within the context of mosambo.

“Mosambo” Pleads and Gives Advice

Mosambo, in plural mesambo, shares common verb root “samb-" with Lingala “ koj sambela”. KoJsambela in Lingala is used in meanings of “to pray”, “to conduct religious activity”, “to plead” (Redden & Bongo 1963: 233), or “to advise” (in religious or patron-client context; Lewis 2016: 149). The meaning of mosambo is closest to “to advise” and to “to plead”. However, it cannot be simply translated as “an advice” or “a plea”. In casual, everyday settings, if someone needs help or advice, they like to ask for help directly:

Suqga | (afrnt!

help.PRS | 1SG

‘Help me!’

Or ask others to “share their hands”:

Kabá | búsé | m&bo!

share.PRS 1PL | 6Fhand

‘Share hands with us!’

Even though what speakers do through mosámbo is giving advice and pleading, the expression of “mosámbo” is used exclusively for an Mbendjele-specific institution of advice, that must fulfil certain aesthetic qualities and style that define them as mosámbo, herein a form of public speaking (details will be discussed in the chapter of Mosámbo). Thus, if pleading or advice that does not take a form of public speaking, it is not mosámbo.

Complementary to the Boko’s speech at the opening of this thesis, the following expressions are to illustrate how my informants reasoned about mosámbo:

MÓ2sámbó | ^kab^p'ié | ma2yélé.

3Fpublic.speaking 3SGFshareFDISTR 6Fwisdom ‘Mosámbo distributes wisdom.’

That led me to a conclusion that mosámbo is indeed perceived as a specific venue for wisdom sharing and promoting people’s maturation. The distributive morpheme “pié” is speculated to be a remnant of an ancient “Pygmy” language, since it is not shared with other Bantu languages (Duke 2001: 57). It is used to increase valency of the verb: “by an indefinite number of object beneficiaries” (ibid: 56). While the verb stem “-kab -” means “to share”, if “pié” is attached, it means that sharing goes from “one-to-each”. It means that through “mosámbo” one (the speaker) shares wisdom with each and every one - mosámbo distributes wisdom.

Mó2Sámbó | a2kani2d¡E | me2ndo | mó | iwna | mó2Súkú.

3-public.speaking | 3SG-put-CAUS | 4-issue | in | 1-child | 3-head

‘Mosámbo causes issues to get in the child's head.’

“jd^é” is a causative valency-increasing morpheme (Duke 2001: 56). While “kan” means “to put”, “kán/jd^é” is to cause that something is being put. Thus, through means of mosámbo, speaker causes issues to get into people’s heads.

Modded

Mdadjo are female public mocking events, re-enactments of people’s silly, “stupid”, or inappropriate actions (Lewis 2002, 2009, 2014b). Similar to mosombd, ridicule and teasing were observed and described in Yaka groups, while joking was identified as one of the basic features of Yaka sense of humour. Moodie can incorporate various forms of humour, such as mockery, ridicule, or teasing. Lewis mostly refers to moodid as a event of mocking or ridicule (2009; 2014a). While mockery involves mimicking someone’s behaviour, ridicule is used here in more general terms as to subject to dismissive behaviour . This thesis will illustrate that literal re-enactments involving mimicry is not always the case in moodio. My research also shows that moodio can take a form of teasing, basic feature of which is “provoking in a playful way” or “tempting someone sexually with no intention of satisfying the desire aroused” (Oxford Dictionary of English 2010a, 2010b, 2010c).

Turnbull emphasises the importance of ridicule in Mbuti society. He refers to the employment of ridicule (1961: 34, 114); to the ridicule based on re-enacting someone’s behaviour and to the repetitions of re-enacted events (ibid: 137); to exaggeration of ridiculing actions (ibid: 134); and to the people’s sensitivity if being ridiculed (1961: 114). Similarly, Leonard mentions that ridicule and joking is employed by the Baka Pygmies to settle disputes and disagreements (Leonard 1997: 12). Michelle Kisliuk offered also several examples of performances similar to moodio, which occurred during female eboka performances (Kisliuk 2000). Koulaninga (2009: 80-81) discusses the nature of mockeries of Mbendjele and Aka from Central African Republic, but the author does not specify the gender of performers, nor provides examples of how these mockery events unfold.

Ridicule is one of the major hunter-gatherer social control tools and modes of egalitarian sanctioning (Boehm 2012; Boehm et al. 1993b; Boehm & Boehm 2009; Woodburn 1982). It is known to be employed by various hunter-gatherer groups: Hadza, Mbuti (Turnbull, 1961), and San in Africa, Ngukurr in Australia, and Enga in New Guinea, and Paliyans in India (Boehm et al. 1993b: 230). Teasing, together with beating, shaming, intensive staring, gaze avoidance, leaving the child alone, threats of danger, and isolation of the child from others are common forms of sanctioning unwanted behaviours of children in small-scale societies (Lancy 2015). adults and peers across cultures use diverse forms of ridicule to educate children about the appropriate ways to act, as summarised by Rogoff (2003: 217-221),

In hunter-gatherer societies, Crittenden observed that public mocking and humiliation was used to sanction non-sharing in Hadza children (Crittenden 2016: 66), teasing was employed by Chabu forager-farmers in teaching spear-hunting (Dira and Hewlett, 2016), and Canadian Inuits In this thesis, I will explore the role of moadzo as a specific context wherein teaching and learning occurs, while discussing its similarities and differences of teaching by teasing, mocking, and ridicule employed by other huntergatherers.

“Mdad^d” Does and Re-does

Mbendjee Yaka have two prefixes that sound the same, but have different meanings and create different gender pairings: the prefix "mo-", which can be either referring to people and other animates if in class one, or can refer to inanimates if in class three (see the table “Bantu nominal class prefixes” at the beginning of this thesis). For example, "mo-na" can be interpreted as “a child” in class one, or “state of being a child” in class three. Accordingly, mosambo’s definition above could be more nuanced and interpreted as a specific “state of advice-giving”.

The inanimate word “ moadzo”, thus, refers to the “state of being”. However, the interpretation of the word stem “ ad^jd” is not that straightforward and clear. There are two possible interpretations that come to my mind. My Mbendjele informants utilised two verbs that refer to “to do” and/or “to make”: “kia”/ “gia” or “d^'is”. If “ad^o” relates to “doing”/ “making”, then it accords with “re-enactments” (Lewis 2009) where performers are in the state of re-doing and re-making others’ actions. The second possible interpretation of “ad^o” could be related with the word of “the body” - “nd^o” (or “njo” in Lewis 2016: 151). If this is truth, then “moadso” could be defined as “a specific state of a body”. Whether it is translated as a specific “state of (re)doing” or a specific “state of doing something with the bodies”, it reflects on the interpretation by Lewis, where “mdad3d” refers to specific actions of women who use their bodies to re - enact/ re-do someone else’s inappropriate or stupid behaviour (Lewis 2009, 2014a, 2014b).

Moadzo was seen as potent in promoting people’s maturation. What follows is a view on moadzo by elder Bibila. On one occasion - after his son’s showing-off actions were re-enacted and mocked - he shared with me what are the impacts of mdad^o on child’s learning:

Mo-ad3o | a-dis | na

3Fpublic.mocking | 3SGFbe.PRS | with

‘Moadso is sharp.’

|

|

3PLFwoman | 3PLFtouch.PRS 3Fpublic.mocking with 1Fchild showing.off

‘Women perform moadso about a child who shows off.’ — .XXX | IX ' | X | XX | x | tx ' | X | t f t f

Mo-na | a | dis | na | m-ino, | a | dis | na | kumba,

1Fchild | 3SG | be.PRS | with | 6Ftooth | 3SG | be.PRS | with | running

a | bomba | nd3o.

3SG | hide.PRS 5.body