David Johnston and Janny Scott

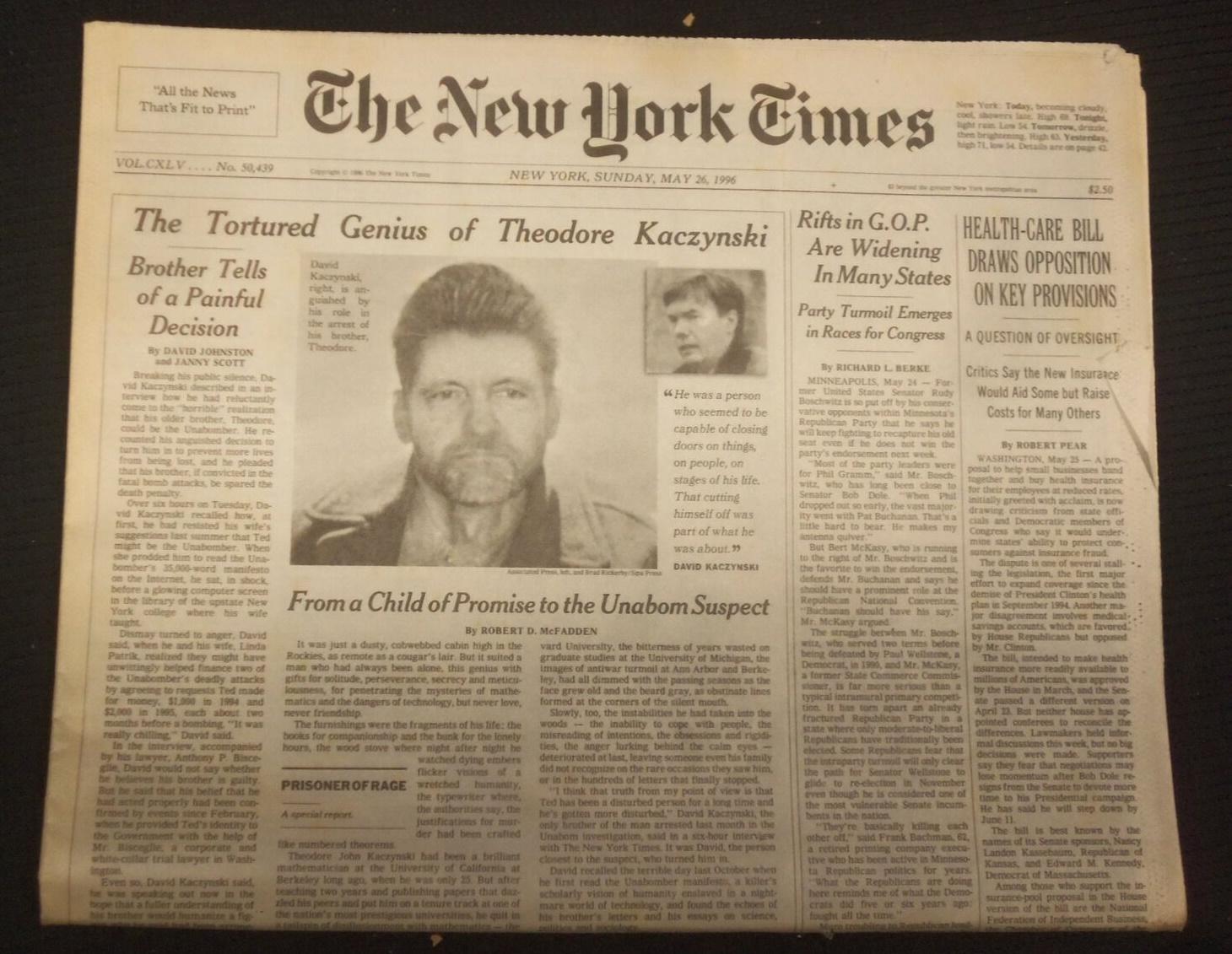

The Tortured Genius of Theodore Kaczynski

Brother Tells of a Painful Decision

Breaking his public silence, David Kaczynski described in an interview how he had reluctantly come to the "horrible" realization that his older brother, Theodore, could be the Unabomber. He recounted his anguished decision to turn him in to prevent more lives from being lost, and he pleaded that his brother, if convicted in the fatal bomb attacks, be spared the death penalty.

Over six hours on Tuesday, David Kaczynski recalled how, at first, he had resisted his wife's suggestions last summer that Ted might be the Unabomber. When she prodded him to read the Unabomber's 35,000-word manifesto on the Internet, he sat, in shock, before a glowing computer screen in the library of the upstate New York college where his wife taught.

Dismay turned to anger, David said, when he and his wife, Linda Patrik, realized they might have unwittingly helped finance two of the Unabomber's deadly attacks by agreeing to requests Ted made for money, $1,000 in 1994 and $2,000 in 1995, each about two months before a bombing. "It was really chilling," David said.

In the interview, accompanied by his lawyer, Anthony P. Bisceglie, David would not say whether he believes his brother is guilty. But he said that his belief that he had acted properly had been confirmed by events since February, when he provided Ted's identity to the Government with the help of Mr. Bisceglie, a corporate and white-collar trial lawyer in Washington.

Even so, David Kaczynski said, he was speaking out now in the hope that a fuller understanding of his brother would humanize a figure who he said had been erroneously depicted in some accounts as an evil genius who had lashed out at the technological world he abhorred. And, he said, by agreeing to talk now, he might help save his brother's life later in a case in which the death penalty could be imposed.

"Clearly, part of my whole involvement in coming forward in this whole thing was a respect for life, that human life is really valuable, that certainly Ted did not in my mind have adequate justification," David said. "If he did attack people and kill people, that was wrong. But by the same token, I feel it would be very wrong if he were killed in the name of some notion or principle of justice. I think it's important that people see him as a human being."

He added: "I think the interests of justice are best served in this case by the truth, and I think that truth from my point of view is that Ted has been a disturbed person for a long time and he's gotten more disturbed. It serves no one's interest to put him to death, and certainly, it would be an incredible anguish for our family if that were to happen."

So far, Ted Kaczynski, a Harvard-trained mathematician who was arrested on April 3, has not been charged with any Unabom crimes. He is being held in a Montana jail on Federal charges of possessing explosive components. But based on the trove of evidence discovered in Mr. Kaczynski's mountain cabin, law-enforcement officials said, Federal prosecutors are preparing to charge him in the nearly 18-year-long string of package bombings, which killed 3 people and injured 23 others.

In the interview, conducted in a 45th-floor hotel suite with a sweeping view of midtown Manhattan, David said he had been closer than anyone to his brother until Ted angrily spurned him in 1989 for deciding to get married. David said he had been profoundly influenced by Ted's uncompromising intellect, his love of wild places, his compassion for children, even what he described as his brother's startling moments of kindness.

David, a 46-year-old social worker from Schenectady who works in a shelter for runaways, sought to keep the interview focused on his brother rather than himself. He also declined to be photographed.

Thoughtfully, and at times emotionally, David detailed the life history of his 54-year-old brother and cast new light on the suspect's personality, mental problems and troubled relationships, on the evolution of his ideas and even on the sources of money that allowed him to travel around the country.

But David said part of his brother's mind remained obscure even to him, partly because of Ted's extremely private nature and the disparity in their ages.

"He's quite a mystery to me," he said. "I work with people all the time. His dynamics I never followed."

David, a powerfully built man who, at the interview, wore a short-sleeved shirt with his tie askew, spoke quietly, with a gentleness and compassion that contrasted with his account of Ted's stridency and anger. He traced his own role in his brother's life -- from an admiring kid brother to a vagabond companion in the wilderness and eventually, to a bewildered victim of his brother's inexplicable rages and rejection. And finally, David, who had watched his brother grow increasingly unbalanced, struggled with a dilemma: whether to turn in his brother, knowing that doing so might place Ted's life in jeopardy, either at the hands of Federal agents sent to capture him or through a sentence of death.

David said he had paid little attention to the Unabom case until last year and had not suspected that his brother might be the long-sought serial bomber until after The New York Times and The Washington Post jointly financed the publication of the bomber's manifesto in The Post last September.

At first, David had ill-defined inklings: the places to which the Unabomber had been linked seemed vaguely familiar.

It was his wife, Linda Patrik, who had never met Ted, who was the first to mention the possibility, initially as a small joke between them. "Hey, you've got this screwy brother," he recalled her saying. "Maybe he's the guy." But the banter planted a kernel of doubt in David's mind.

Then in the summer of 1995, on vacation in Paris, Professor Patrik heard about a rash of terrorist bombings in France and read a surge of news accounts about the Unabomber. The articles told of the fatal mail bombing of Gilbert Murray, a forest industry executive, on April 24, 1995, in Sacramento and a flurry of letters sent by the Unabomber to The Times, the mailing of the manifesto and the Unabomber's promise to cease the bombings if the manuscript was published. Her questions about Ted grew more serious, and she told David her suspicions when he joined her in France.

"She was actually taking it seriously by the time I got there," David said. "She said, 'I think we need to look into this.' I pretty much said, 'Yeah, if the opportunity arose.' I dismissed it."

But the thoughts refused to go away. "I didn't put it out of my mind," David said. "It was kind of there. We heard that the manifesto was going to be published."

The manifesto was published on Sept. 19, but David put off reading it because of visits by relatives, including his mother, Wanda. He avoided questioning her, even in a veiled way, about Ted's past. "I didn't want to play that game," he said. Eventually, one day in early October, the couple went to a library at Union College in Schenectady, where Professor Patrik teaches philosophy, to find a copy of the document.

The newspaper copy of the manifesto was missing, so a librarian helped them find it on the Internet. The computer version contained only the introductory section of the manuscript. "But Linda, she was looking at my face when I was reading those six pages," David said. "My jaw dropped."

Could he remember those feelings? he was asked.

"Chills, I think," he said. "Felt some anger. I was prepared to read the manifesto and be able to dismiss any possibility that it would be Ted, but it continued to sound enough like him that I was really upset that it could be him."

David said he and Linda had thought about the dates of the two most recent -- and fatal -- bombings. Then they thought about the money they had sent Ted. "I just felt awful about that," he said. "My wife expressed a great deal of anger that money was sent, partly hers, that might have killed other people."

Later, when he read the full text of the manifesto, his dread deepened, David said. On the advice of a lifelong friend, he wrote to Ted. "I told him that I regretted very much the strain in our relationship and said I would like to come visit him," David said. "I wanted to see him after all these years."

But Ted "wrote back that the very suggestion made him feel awful and made him feel angry," David said.

David agonized over what to do next. "It was horrible, there's no question about that," he said. "One concern was if, God forbid, I were in a position to prevent more lives from being lost, I couldn't do otherwise. The other concern was for Ted himself, his psychological well-being. It was horrible to me that I was considering my brother to be this person."

Meanwhile, David and Linda had agreed to approach Susan Swanson, an old friend from Chicago who was a private investigator, to evaluate the couple's anxious questions in confidence. "We went to her first asking for information, how she would go about handling a potential case, someone we knew committed a serious crime," David said.

David's biggest worry was Ted's reaction: Could he keep his investigation secret from Ted? And if investigators approached him, how would he react? "If he were guilty, he likely would be silent or say little," David said. "If he were innocent, the emotional upheaval would be devastating to him and might have some irrevocable effect that would be disastrous to his well-being."

Then David and Linda found old letters by Ted that seemed to match the prose style of the Unabomber -- "certain kinds of phrases" with epithets mixed in. Ted seemed to fit the Federal Bureau of Investigation's profile of the suspect as a loner and an angry academic.

Ted's antipathy toward technology seemed to resonate through the manifesto.

But in some ways, Ted and the Unabomber seemed mismatched. For example, the Unabomber derided leftists, a subject that David had never known to be important to Ted. "I knew that he disapproved of socialism or leftist ideas, that he was far from being a leftist, that he had criticized some of those ideas, but I never thought it was a major piece," David said.

There were other incongruities. David knew his brother had taken bus trips, but he seemed to dislike travel and could not easily afford the long bus rides to the cities in Northern California from which some of the bombs and letters to news organizations were mailed.

But in January, after comparing the manifesto to samples of Ted's writing, the investigator and other analysts concluded that there was a significant chance he was the author. David and Linda decided to make contact with the authorities. "I guess it's fair to say I felt compelled," David said. "The thought that another person would die and I was in the position to stop that -- I couldn't live with that."

Approaching the F.B.I., with Mr. Bisceglie as their representative, was still a difficult step. They worried about Ted, "his psychological and physical well-being." But in mid-February, they went ahead and turned over Ted's name. Within days, the ring began to close.

Undercover agents, hiding in the woods, staked out Ted's cabin. Other agents fanned out across the West, interviewing desk clerks, bus drivers and postal employees to determine whether Ted's travels had coincided with the postmarks on the package bombs.

Just hours before investigators were scheduled to arrive at his mother's new home in Schenectady to interview her and pick up more of Ted's letters, David visited her and, after the long months of shielding her from his fears about her older son, he confessed his suspicions.

"I was very anxious how she was going to react," he said. He told her of the last few agonizing months.

"The first thing she did," he said, "was to hug me for what I'd been going through." Then she voiced disbelief: "It couldn't be Ted." Then she said, "You could be right."

"The first concern was for me, I think," David said. "I believe she knew me well enough. I did not do this lightly."

'It's Important That People See Him as a Human Being'

Following are excerpts from an interview by The New York Times with David Kaczynski, as transcribed by The Times. Mr. Kaczynski's brother, Theodore J. Kaczynski, is the suspect in the Unabom case.

I've had a chance to see some of the things on TV, to read a number of things in print that describe Ted, that portray Ted in a certain way, and I had a strong sense that the real person was not coming through those portraits, that there was emphasis placed on things that made Ted seem especially heartless or mean. I wanted people to have a fuller picture of the kind of person he was, including contradictions, the mysteries that I'm not able to sort out at this point. Clearly, part of my involvement in coming forward in this whole thing was a respect for life, that human life is really valuable, that certainly Ted did not in my mind have adequate justification. If he did attack people and kill people, that was wrong. But by the same token, I feel it would be very wrong if he were killed in the name of some notion or principle of justice. I think it's important that people see him as a human being. . . . I think the interests of justice are best served in this case by the truth, and I think that truth from my point of view is that Ted has been a disturbed person for a long time and he's gotten more disturbed. It serves no one's interest to put him to death, and certainly it would be an incredible anguish for our family if that were to happen. It was not an easy decision to come forth with the interview. There are a lot of risks in it. The sole purpose is to help people to see Ted as a human being. . . .

I think I love his purity. I think he's a person who wanted to love something and unfortunately, again, it gets so complex. He failed to love it in the right way because in some deep way, he felt a lack of love and respect himself. That he could have done so much. He had incredible potential. He was so bright. I think some of the outpouring of sympathy can be seen when our cousin was in an automobile accident. Ted was the first one to write to him. He was so touched by his letter; it was so real, so tender. He had this incredible capacity to show human sympathy. Unfortunately, he was unable to integrate it into his personality. It was a kind of richness that was seldom tapped and did not ultimately play a role in relieving his own sense of injury. The point is, at the end in some ways he is able to face difficult truth more so than most of us. On the other hand, he never quite circles back and makes the connection and learns from these things. . . .

Let me state an incident that really was very touching to me. . . . I remember visiting him in '86 when I had been using a saw to cut some wood that we were going to burn in his stove. I made some attempt to set up the saw when the table gave way. I fell down. Ted came running up to me. "Are you O.K?" "Oh, yeah, I'm O.K., but I hope I didn't break your saw." I knew he had very little money, and he kept and cared for his things for years. And he said, "The hell with the saw; are you O.K.?" He touched my shoulders. It was incredible and touching and human. There was a closeness between us as brothers. He is the only brother I will ever have. He would understand it at times. Whatever reason, it wasn't a regular relationship he could reconcile with. The other aspect of the personality was that he was capable of it at moments. . . .