David Skrbina

Participation, Organization, and Mind

Toward a Participatory Worldview

Part I: Chaos and Mind - Situating the Participatory Worldview

Chapter 1 - The Nature of the Participatory Worldview

1) The Participatory Worldview and the Spiral of Western Civilization

3) The Meaning of Participation

4) Wheeler, Skolimowski, and the Modern Origins of the Participatory Worldview

5) Some Early Elements of Participatory Philosophy

Chapter 2 - Concepts of Mass and Energy in Western Civilization

2) Philosophia Materia — Historical Perspectives

Chapter 3 - Chaos and the Complexity of the World

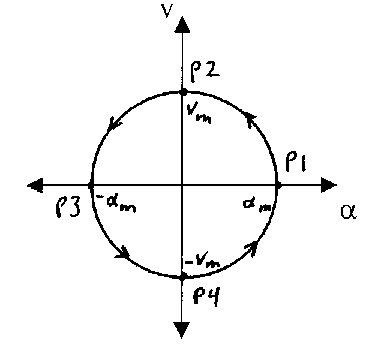

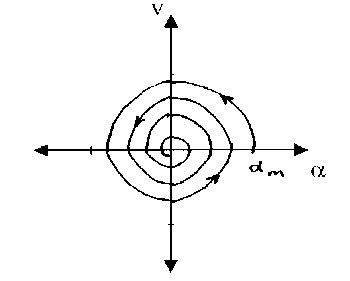

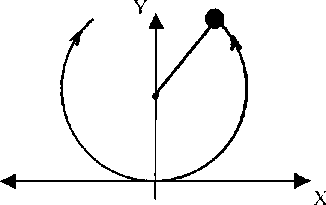

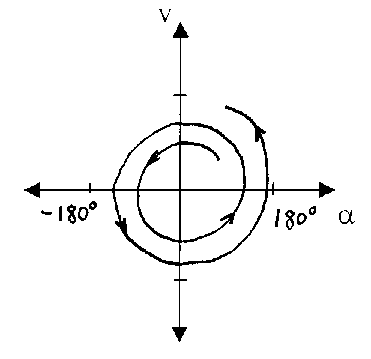

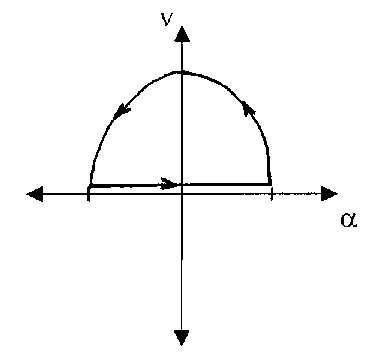

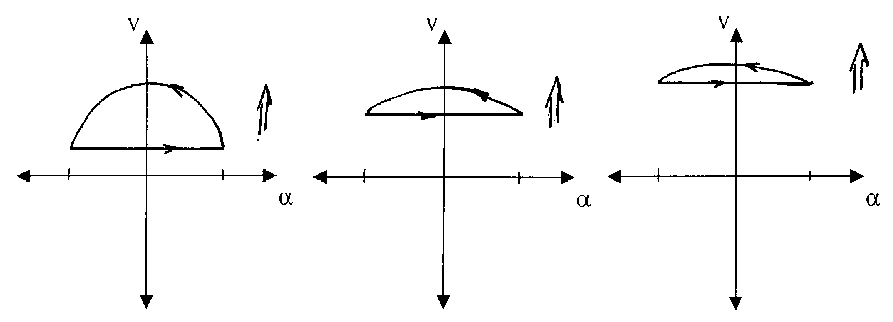

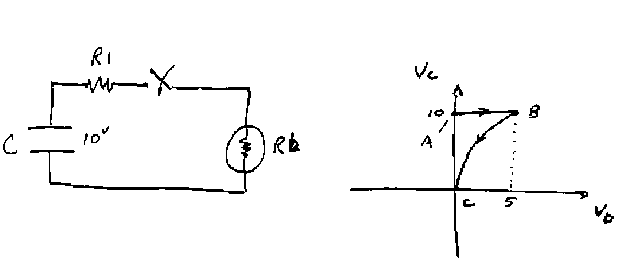

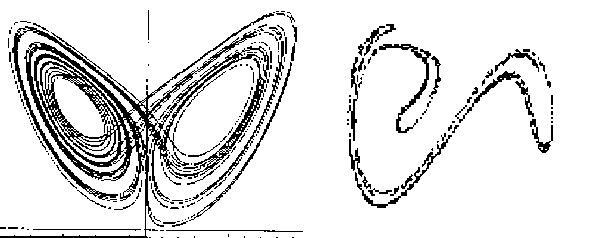

4) Phase Space in More Complex Systems

Chapter 4 - Mind and Brain in Phase Space

1) The System of the Human Brain

3) Mind and Brain in Phase Space

4) Recent History of Mind in Phase Space

5) Characteristics of the Point of Consciousness

6) Hylonoism, Information, and Mind-Brain

7) Cell-Based, Biological Mind

9) Explanation versus Description

Part II: Panpsychism, Hylonoism, and the History of Participation

Chapter 5 - Panpsychist Perspectives from the Ancient World

1) Panpsychism and Participation

4) Panpsychism in Plato and Aristotle

6) Participatory Philosophy in the Early Christian Era

7) Renaissance Naturalism of the 16th Century

8) Campanella and the Transition to the 17th Century

Chapter 6 - The Modern Era of Panpsychism and Participation

1) Emergence of the Mechanistic Worldview in the 17th Century - Spinoza and Leibniz

2) Continental Thinking of the 18th Century

3) 19th Century Developments in Germany and England

4) The Evolution of Ideas into the 20th Century

5) Developments of the past Three Decades

Part III: Toward a General Theory of Participation

Chapter 7 - Scientific Perspectives on Participation and Mind

2) Panpsychism in 20th Century Science

4) Ubiquitous Matter and Zero-Point Energy

Chapter 8 - Social Phenomena, Aggregate Mind, and the Nature of Exchange

1) Historical Ideas of Group Mind

2) Social Mind as a System of Exchange

1) Bataille and the Concept of Superabundance

2) On the Relationship between Capitalism and Technology

3) Qualities of the Social Mind

4) Conclusions and Summary of the Thesis

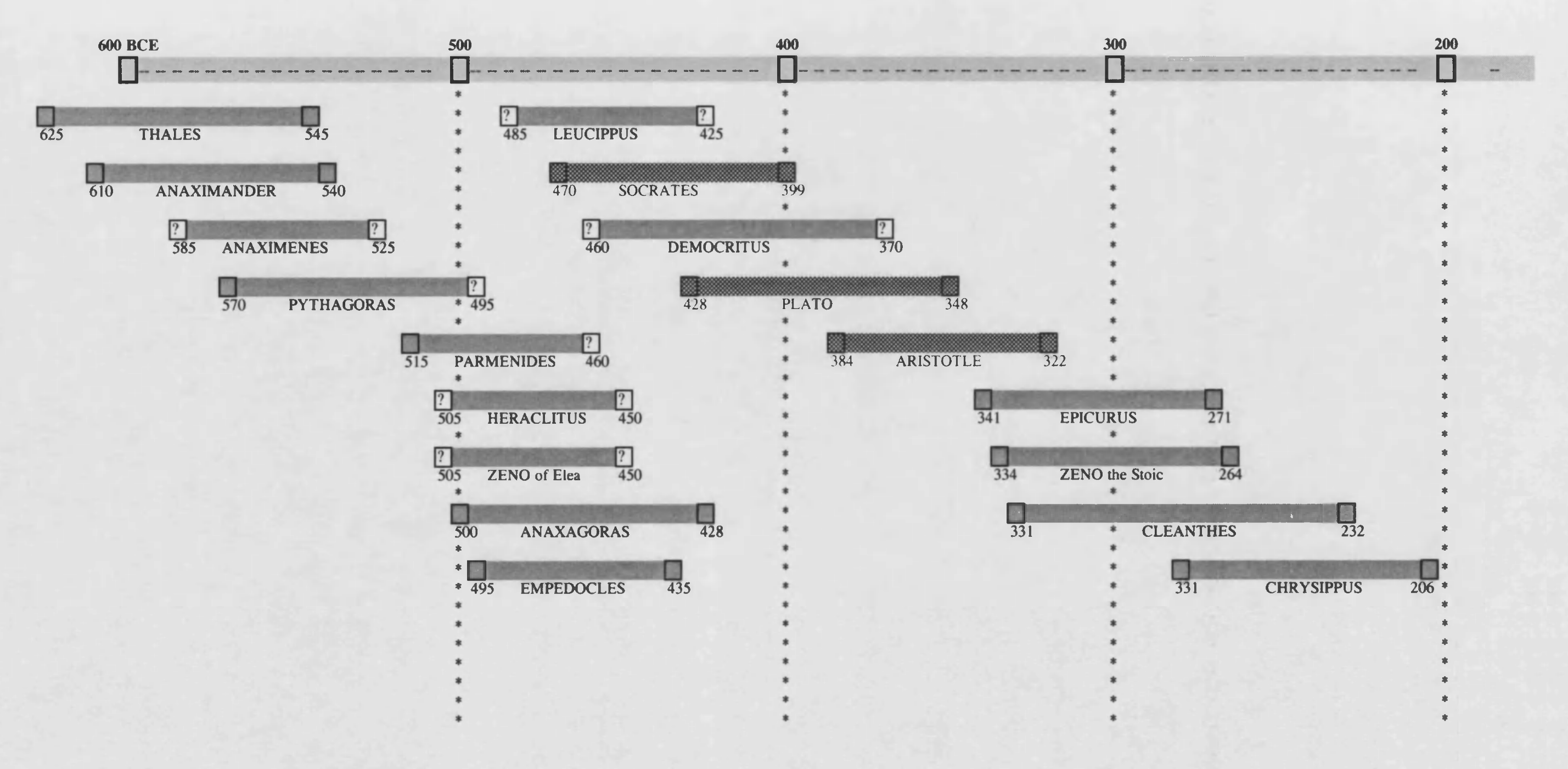

Appendix A – Timeline of Important Greek Philosophers (Pre-200 BCE)

Thesis Summary

The present modern worldview, the Mechanistic Worldview, has become inadequate to handle pressing concerns of society. It has outlived its usefulness, and hence a new worldview is called for. I develop the Participatory Worldview as a promising alternative, and explore various themes of participatory philosophy throughout the history of Western Civilization.

As I conceive it, the concept of 'participation' is fundamentally a mental phenomenon, and therefore a key aspect of the Participatory Worldview is the idea of 'participatory mind'. In the Mechanistic Worldview mind is a mysterious entity, attributed only to humans and perhaps higher mammals. In the Participatory Worldview mind is a naturalistic, holistic, and universal phenomenon. Human mind is then seen as a particular manifestation of this universal nature. Philosophical systems in which mind is present in all things are considered versions of panpsychism, and hence I argue for a system that I call 'participatory panpsychism'. My particular articulation of participatory panpsychism is based on ideas from chaos theory and nonlinear dynamics, and is called 'hylonoism'.

In support of my theory I draw from an extensive historical analysis, both philosophical and scientific. I explore the notion of participation in its historical context, from its beginnings in Platonic philosophy through modern-day usages. I also show that panpsychism has deep intellectual roots, and I demonstrate that many notable philosophers and scientists either endorsed or were sympathetic to it. Significantly, these panpsychist views often coexist and correspond quite closely to various aspects of participatory philosophy.

Human society is viewed as an important instance of a dynamic physical system exhibiting properties of mind. These properties, based on the idea of participatory exchange of matter and energy, are argued to be universal properties of physical systems. They provide an articulation of the universal presence of participatory mind. Therefore I conclude that participation is the central ontological fact, and may be seen as the core of a new conception of nature and reality.

Part I: Chaos and Mind - Situating the Participatory Worldview

Chapter 1 - The Nature of the Participatory Worldview

1) The Participatory Worldview and the Spiral of Western Civilization

As we find ourselves at the beginning of the third Millennium, Western civilization faces an epochal change. This change is far more profound than the mere numerical advance of the calendar. Our secular, dualistic, reductionist view of the world -- our Mechanistic Worldview, also known as the Newtonian or Cartesian worldview -- is showing signs of old age. After 400 years of guiding our inquiry and actions, after many successes and a growing number of failures, the Mechanistic Worldview is increasingly under attack on many fronts: philosophically, ethically, spiritually, even from within itself, from the scientific and technological perspective. Our intellectual and social lives have become vastly more complicated than in past generations. Social and environmental problems are rapidly mounting, and depression and apathy seem increasingly prevalent.

Unfortunately, the Mechanistic Worldview -- the source of our values, the justification for our actions, the framework upon which all our ideas are laid out -- seems less and less able to cope, and less able to provide satisfactory resolution. The time has come to deeply reexamine our present worldview, and, to the greatest degree possible, to creatively transcend it.

Even though the Zeitgeist affects us all, the task of articulating a new worldview falls primarily to those philosophically-inclined thinkers of all disciplines[1]. Traditionally the greatest burden for this task has fallen upon the philosophers proper. Philosophers are, after all, in the business of examining things deeply, of understanding the root causes of our intellectual and emotional deficiencies, and of charting new paths for society. Such has been the role of the great philosophers throughout history. Unfortunately contemporary philosophy seems, at this pivotal moment in history, unable to rise to the challenge. The complexity, obscurity, and irrelevance of much of modern analytic and linguistic philosophy are a powerful indictment. Modern philosophy has slipped, perhaps unwittingly, into the role of defender of the Mechanistic Worldview. In doing so it has created strong inhibitions against deep criticism of mechanism and the need for fundamental change. Perhaps I am overstating the culpability of modern philosophy; after all, every culture must evolve guardians of the status quo. This is how a culture defines and preserves itself. Nonetheless, new worldviews will inevitably emerge, as they must, for this is in the nature of the evolution of society. And in true Kuhnian fashion, the greatest likelihood is that new worldviews will emerge from outside the system of conventional philosophic thought.

A number of people and organizations are responding to this vital challenge of our age. Emerging worldviews come in many variations, whether ecological, spiritual, social, or technological. Many of these, it must be agreed, are utterly incapable of responding deeply to the needs of society and the planet. One in particular, however, seems most promising; one that has been called the Participatory Worldview. It is this worldview that I shall articulate and examine in this dissertation.

In a word, the Participatory Worldview is a response to the increasingly apparent limitations of the Mechanistic Worldview: Where the Mechanistic Worldview emphasizes reductionism, the Participatory Worldview emphasizes holism. Where the Mechanistic Worldview adopts a dualistic, subject-object approach to reality, the Participatory Worldview adopts an interactive, cooperative approach. Where the Mechanistic Worldview focuses on quantitative analysis, the Participatory Worldview focuses on qualitative analysis. Where the Mechanistic Worldview is ethically neutral and detached, the Participatory Worldview incorporates a strong axiological component. Where the Mechanistic Worldview investigates the world via the scientific method, the Participatory Worldview uses new methodologies of participation and action research. Where the Mechanistic Worldview sees a universe of dead inert matter, the Participatory Worldview sees a universe active, animated, and co-creative.

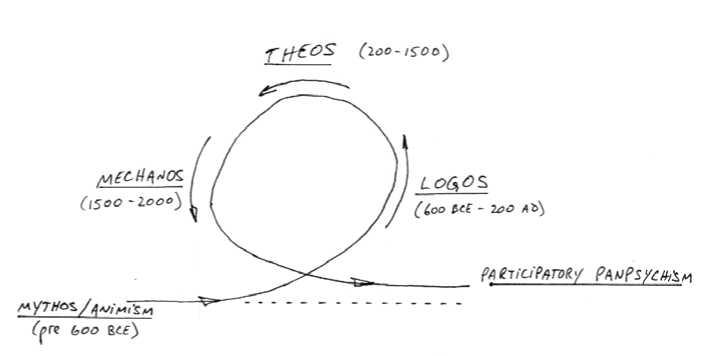

Let me begin by placing the Participatory Worldview in its larger historical context. I will do this via a guiding metaphor, as follows: In the 2500 years since ancient Greece, Western civilization has embarked on a monumental detour of thought. The aboriginal worldview was of a spiritual, animistic, integrated cosmos. We see this in the remnants of ancient cultures throughout the world. We see this in the great stories of Homer and Hesiod, in the Vedas, in the Bhagavad Gita, in the pantheon of Greek and Roman gods, in the myths of the Australian aborigines. Humanity was embedded in a spiritual and divine world. Humanity's role in the cosmic system became articulated in the various myths, religions, and cultures. Such was the state of humanity for many thousands of years. It is this holistic, animated worldview (actually, collection of worldviews) that, historically, represents the 'main path' of human cultural evolution.

But that prehistoric worldview was of a dim, unarticulated, incoherent cosmos.

Knowledge was in some sense superficial, limited, and immature. The natural world was mysterious, arbitrary, and in many ways inscrutable. The gods of nature assumed human form, and became attributed with human-like qualities -- happiness, anger, vengeance, pride, lust.

In the overall evolution of total human culture, such an unarticulated worldview could not persist. The nature of evolution is transcendence, and thus this primitive outlook on mankind and nature was impelled to change. The path of transcendence required a new perspective on the cosmos. As it happened, this new perspective was the one offered by what we broadly call the Western worldview[2]. Western civilization embarked on a long detour from the main path of thinking about the world, a detour that allowed for a new and transcendent perspective on itself and the universe.

The groundwork for this detour was laid by the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, but it began in earnest with Plato and Aristotle (circa 400 BCE). Plato's articulation of the essence of Western philosophy and Aristotle's development of abstract, analytic thinking launched an entire civilization on a path of new ideas, conceptions, and methods - including logical and mathematical analysis, scientific method, and technological innovation.

This detour was essential, and in some sense inevitable. In order to better understand and articulate our cosmos, it appears to have been necessary to pass through a phase of dualistic, analytic inquiry. Only by this means could we have arrived at a knowledge of evolution, of the history of the Earth and universe, and of the nature of physical reality. Humans are a product of universal evolution, and we possess unique capabilities for reflection and articulation. As the medieval Scholastics taught, we are a microcosm that is a reflection of the macrocosm. In other words, this grand detour of the mind allowed the universe, in the form of the human, greater articulation and knowledge of itself. In at least this one dimension, the cosmos 'knows itself' more deeply than ever, through us. Thus this detour served the larger interests of the universe; it was a necessary and fitting part of the greater process of evolution.

And yet now the detour appears to be ending. We can envision a return to the main line of cultural evolution, of worldviews that are holistic, spiritual, animated, and co- creative[3]. But we return not on the same level as before, but rather at a much greater height. In this sense, the path of Western civilization can be seen as a spiral. We have deviated from the great (and largely unwritten) history of mankind, passed through a tremendous epicycle of learning, and now return - hopefully wiser and chastened - to continue our larger cultural destiny. Our return to, and transcendence of, this mainstream of cultural evolution is articulated in the Participatory Worldview.

I offer two general categories of evidence for this view. First, there are persistent traces of the older, deeper worldview all throughout the history of Western philosophy. These occur primarily in the various forms of panpsychism that can be found in the thinking of many of our most important intellectuals - panpsychism being defined, roughly, as the doctrine that all things have a mind-like quality. These traces are largely unknown, unexplored, or outright ignored by modern philosophers. And with good reason: they strongly hint at the ultimate undermining of the Mechanistic Worldview. To fully spell out and document these traces of panpsychism requires book-length treatment, and here I can only give (in Part II) an overview of the most relevant points.

One also finds traces of participatory thinking throughout Western philosophy, and significantly, these tend to occur in conjunction with the elements of panpsychism. I will show that the panpsychist philosophers frequently contributed to advances in the participatory philosophy, either via theories of being (ontology), of knowledge (epistemology), or in methodology. I find this correlation highly suggestive; it indicates that panpsychism has some deep connection with a Participatory Worldview. As these participatory and panpsychist elements tend to occur together, I will treat them jointly in Part II.

The second general category is this: Even from within the Mechanistic Worldview -from quantum mechanics, from aspects of modern biology, and from the study of nonlinear systems and information theory -- we find evidence of a return to an animated, co-creative cosmos. This is manifest in the scientific concept of participation as developed by Wheeler, Bateson, and Bohm, and in certain aspects of chaos theory, as I will explain in detail.

Consequently, my main task will be to illuminate and unify these two general bodies of evidence. In the process I will bring into the discussion a third central theme, my own theory of mind and reality. This theory - which I call hylonoism - is offered as an element of a fuller and more articulated picture of the world. I see hylonoism as contributing to a fusion of the aboriginal intuition of a panpsychic reality with the insights gained by our 2500 year detour of thought. In essence, I will be arguing for a panpsychic interpretation of participatory philosophy.

Following Skolimowski (see his 1994, pp. 120ff), I see the spiral of Western civilization as historically encompassing four general phases: The earliest, pre-historical phase, with its holistic and animated cosmos, is designated "Mythos". The era from ancient Greece through the early Christian era is called "Logos". The rise and dominance of the theological worldview is referred to as "Theos". And the period of the Mechanistic Worldview is labeled "Mechanos". As I have explained, I believe that we are now rejoining the ancient axis at a greater 'height', in a new phase that we may call "Participatory Panpsychism". These phases are shown in Figure 1.

Let me emphasize here that neither participatory philosophy nor the Participatory Worldview require a panpsychist orientation. Participation can be well articulated without recourse to panpsychism; in fact, neither Wheeler nor Skolimowski - two central figures in the recent development of participatory philosophy - are explicitly panpsychist. On the other hand, Bohm, Bateson, Abram, and Berman all have recently put forth elements of panpsychism in their philosophical systems, and all have clearly articulated aspects of participatory thinking. And there are the many intriguing historical connections between participatory ideas and panpsychism. Here I will offer a panpsychist interpretation of participation, both because I see it as representing the more ancient undercurrent of human culture, and because it is a logical outcome of hylonoism and my reading of chaos theory.

2) Setting the Framework

Let me begin with a few very general observations that will serve to frame the subsequent discussion. I offer the following vision: all organization, all structure, bears a common imprint. This imprint is something that is dynamic, interactive, and participatory. It results from the continuous exchange of material and energy amongst the elements of the organization, and between different levels of organization[4]. It is

present in all structured matter, from atoms to rocks to people to ecosystems to stars. It is an inevitable consequence of the physical reality. This core characteristic of reality is manifest in humans as 'mind', and in other things as something analogous.

I will attempt to describe and articulate this common link among all levels of structure. This is not to propose that all structures are the same, or are equal, or are one, but rather that all can be described with common concepts and can be said to share at least some common fundamental characteristics. An analogy can be drawn with the role of DNA in living organisms. DNA is a common means by which all organisms grow, reproduce, and pass along their genetic inheritance. No two organisms have the same DNA, but each one's structure is the same, and is composed of the same basic elements. The action of DNA influences much, but certainly not all, of how the organism behaves in the world. And as a philosophical concept, DNA is vitally important because it demonstrates a common linkage, a common heritage, amongst all living creatures. It unites humans with the world of animals and plants in a way that has a fundamental effect on how we view ourselves and our place in the natural world.

So too, I propose, can we conceive of a common means of describing organized structures. Such a means is clearly more general than DNA because it encompasses not just living organisms, but everything from inanimate structures though collections of structures and organisms. My theory of hylonoism offers up a new way of viewing ourselves and of viewing the world, and has important implications for many aspects of existence. In a nutshell, hylonoism claims that material reality is deeply infused with mind. Such a theory is antithetical to the Mechanistic Worldview, and, I claim, is thus part of a truly new worldview. The concept of hylonoism, based as it is in the dynamic exchange of energy, is a fundamentally interactive picture of the world. It is a picture in which elements of structures interact in a particular way, in which they participate, to create organized wholes, and in which organizations interact to create new, higher-order structures. Hylonoism is an attempt to provide the theoretical and philosophical basis for the emerging Participatory Worldview.

Such an endeavor is necessarily wide-ranging and interdisciplinary. It encompasses philosophy of mind, physics, complexity theory, and systems theory, among others.

Although my main approach will be philosophical in nature, I also draw on scientific, mathematical, and historical sources to help articulate the relevant concepts. I present only the degree of detail necessary to make the point. Needless to say, the Participatory Worldview is a dynamic, emerging concept, and no account of it can be considered final and complete. What I hope to achieve is the creation of a comprehensive framework for this worldview, which will allow us to better understand its development throughout history, and to begin to articulate some of its more important aspects.

My goal is to interpret and articulate the participatory worldview as fully as possible starting from the commonly held assumptions about science, mind, and the nature of reality. It is my belief that there is plenty of room for expansion and articulation in our worldviews from within the present set of conceptual tools. The same set of facts about the world can give rise to many interpretations, and new interpretations, or new paradigms, can change the way we see the facts. I will take the facts of the physical world and reinterpret them in a new light. This new paradigm will lie outside the standard objectivist, materialist paradigm. Anything else would be less than a truly new worldview, a rather minor modification of what presently exists.

There are different levels of assumptions that must be clarified. When discussing fundamental issues of mind, consciousness, and reality, one must make clear both one's epistemological and ontological assumptions. In regards to the first, the traditional split is between rationalist (inquiry using the powers of intellect and reason) and empiricist (inquiry via experimentation and sensory data) approaches to acquiring knowledge[5]. I will follow primarily a rationalist approach, although I will occasionally make arguments based on empirical data and on sensory impressions, particularly when discussing phenomenological concepts.

With regard to ontology, one must be especially clear. The nature and substance of reality that one accepts, or starts from, can clearly affect the whole nature of the discourse. Discussions on the nature of mind in particular are notoriously sensitive to ontological assumptions. It will be helpful, if only for historical comparison reasons, to situate arguments with respect to certain traditional 'branch-points' of ontology, such as monism vs. dualism, or naturalism vs. supernaturalism. For example, we may define the conventional scientific ontology as materialistic monism, or physicalism - nothing exists in the world except for various forms of matter, or mass, and the fundamental forces of physics that arise from, and act on, them[6].

I will begin my discussion within this standard physicalist paradigm. As I explore aspects of my hylonoetic theory, it will point toward the view that materialistic monism is inadequate to describe all aspects of reality. However, the deep integration and connection of all things ultimately requires, I believe, some form of ontological monism. This underlying monism manifests itself in different ways, of which two seem relatively clear (at least since Spinoza): a 'physical' realm, and a 'mental' realm. The second realm that I argue for is in itself non-material, but arises in conjunction with the material aspect of the cosmos. Unlike the Platonic realm of the Forms, it does not exist objectively and unchanging independent from physical reality.

Beyond these two, there may well be one or more other dimensions to reality, as I will explain. However, I deal for the most part only with these two basic aspects of an underlying monistic reality. In other words, I argue that a form of naturalistic, dualaspect monism is the most useful (though not necessarily most complete) way to describe the world as we experience it. Thus, I will attempt to transcend both physicalism and conventional dualism, but without relying on esoteric or supernatural concepts. I seek an entirely naturalistic description of reality, a reality that is ultimately holistic, participatory, and deeply interconnected.

It may be an advantage to begin my arguments from within conventional physicalism, and proceed (at least initially) under conditions of conventional rationalism. It is clearly the more conservative approach, in that my conclusions will be found not to rely upon newly-created or highly-contentious concepts. My assumptions and method of analysis are largely conventional. It is my interpretation and conclusions that are unique.

So to summarize my general approach in this thesis: My primary intention is to make an investigation into the phenomenon called ‘participation’. I want to explore its deeper meaning, its implications and its relevance at the present point in the evolution of Western civilization. As mentioned, I think that participation and participatory philosophy can form the basis of an alternative worldview, one that may help resolve some of the more troubling aspects of our present outlook on society and nature.

To this end, I will weave together three main themes: First there is the concept of participation itself, as it has evolved over the past 2,500 years. Second is panpsychism -from its early manifestation in ancient Greece through the well-articulated philosophical views of the 20th century. Third, I will develop my own theory of hylonoism as an attempt to illuminate and unite the other two strands, and to further articulate the idea of participatory mind. I will demonstrate that hylonoism has a number of important historical predecessors, and is both a continuation and an advancement of many great insights and intuitions about mind.

The process of weaving these threads together is not a simple linear one. It requires a number of loops and iterations, a series of investigations and examinations that may hit upon similar themes a number of times, but from different angles and perspectives. I seek to build up an all-around picture of the Participatory Worldview, and this requires that I set the background, lay out the structure, and then proceed to add the details that give it life -- all with an eye on the relevancy of historical ideas, and placement in the evolution of thought. Thus, the trajectory of this thesis may perhaps be described as a kind of spiral in itself, a circling around of related ideas, each time progressing a bit higher toward an articulated worldview.

Finally, let me note that my process of thinking here has been in itself an attempt at participatory inquiry. Rather than moving toward a preconceived end, I have attempted to follow the looping and weaving of the three main ideas in a somewhat open-ended manner. My research was done in an open and cooperative fashion, with only general objectives to guide me. As such, this thesis reflects the nature of the participatory world itself: it is open, interactive, sympathetic, directed but not restricted -- and never truly complete. If this thesis fails to present any hard definitions or ultimate truths, it is because these things are not in the nature of the participatory world.

Participatory thinking requires a delicate balance. One must allow concepts to be open to their contextual surroundings, and yet still make them as articulate and illuminating as possible. We must communicate with words, and yet recognize that verbal definitions are inherently problematic. From a participatory perspective definitions are fundamentally context-dependent; they are incapable of being usefully stated or appropriately understood in isolation. Definitions, like 'truths', are necessarily incomplete. We find that we have rather a series of evolving, ‘participatory definitions', and 'participatory truths'. Each system of truth reflects a particular state of mind, and a particular state of the cosmos.

The theories I present here -- hylonoism in particular -- are not in any way intended as absolute truths. Nor are they complete and finished products. They are rather open philosophical conjectures: if we look at the world in the way that I suggest, then here are the consequences and implications. They will be fruitful conjectures if they provide greater understanding and illumination of the central issues of existence. My ideas here are intended only as a further step in the articulation of the human condition, and our relationship with the world.

Let me now map out more specifically the approach I take. This thesis is structured in three parts:

Part I introduces the concept of participation, and explores its relation to recent developments in chaos theory. Chapter 1, The Nature of the Participatory Worldview, describes the basic concepts of the discussion, and looks at the history and development of 'participation' as a philosophical concept, particularly in contrast to the modern scientific worldview. In Chapter 2, Concepts of Mass and Energy in Western Civilization, I look at the development of the concepts of 'mass' and 'energy' since ancient Greece. This sets the stage for a broader understanding of the mass-energy universe, and its participatory nature. The third chapter, Chaos and the Complexity of the World, examines the essentials of chaos theory, with an emphasis on how it relates to physical structures of the natural world. The main principles of chaos are seen to be directly relevant to the philosophy of participation. Chapter 4, Mind and Brain in Phase Space, employs chaos theory, and more generally, nonlinear systems analysis, to articulate a new conception of the human mind as it relates to the physiology of the brain. I then use this analysis for generalization to other systems, living and non-living.

Part II explores the concept of panpsychism and its relevance to participation from a historical perspective. It is primarily an inquiry into the mental aspect of the participatory world. Chapter 5 is titled Panpsychist Perspectives from the Ancient World. Here I discuss the historical development of generalized theories of mind, particularly in light of my hylonoism theory. I trace panpsychist theories from the ancient Greeks through the Italian Renaissance period of Telesio, Bruno, and Campanella at the end of the 16th century. Chapter 6, The Modern Era of Panpsychism, continues this historical study, beginning with Spinoza and Leibniz, through the German scientistphilosophers, and up to the present.

Part III examines the scientific basis for panpsychism and participation, and extends the basic insights of hylonoism to consider larger issues of organization and evolution. It primarily investigates the physical aspect of the participatory world. Chapter 7 is on Scientific Perspectives on Participation and Mind, in which I look at arguments in support of both panpsychism and participation from within the scientific worldview, focusing on events of the past 150 years. The works of Bateson and Bohm are central here. In Chapter 8, Social Phenomenon, Aggregate Mind, and the Nature of Exchange, I consider the 'group mind' concept, and its role in a larger hylonoetic world. Processes of exchange, expenditure, and abundance are key. Technology is discussed as a key ingredient in the expropriation of energy for the human species. I then pull together several lines of thinking, and offer up some comprehensive thoughts on participation and structure.

3) The Meaning of Participation

First, I want to explore in some detail the meaning of the term ‘participation’, and how it can play such an essential role in the articulation of a new worldview. The word ‘participation’ generally has a positive, up-beat, optimistic tone; it implies that someone or something is ‘playing along’ with the group, is cooperating, is working with others to achieve some larger goal or objective. I find this aspect of ‘cooperating with others to achieve a joint purpose’ highly evocative and entirely appropriate for use as a basis of a new perspective on the world -- as will become clear later on.

It is enlightening and useful to examine the definition and etymology of ‘participate’. There are three primary definitions[7]. The first is the common usage, "to take part [in]", as, to participate in a group discussion. This clearly involves output on the part of the participator; he or she must proactively exert themselves, speak up, take action, become involved. The second definition is "to have a part or share of something", as when we say 'the employees are now allowed to participate in the profits'. This is a passive sense of the word, and in particular is passive reception; I participate by receiving something, with no essential action required - though of course I (presumably) willingly allow the reception.

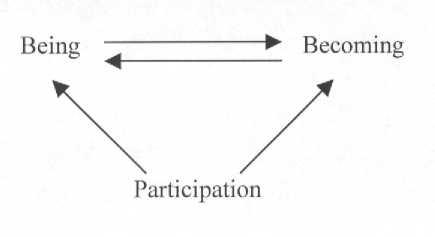

The third is perhaps the most subtle and least used: "to possess something of the nature of a person, thing, or quality". This is subtly dynamic; it implies capturing something of the essence of a thing, incorporating it, and even becoming in a sense changed by it. By this meaning, participation is a state not merely of being, but also of becoming. This meaning derives from the origins of the word 'participate'. To participate is to ‘partake’, literally, ‘to take a part of’. Participate comes from the Latin noun particeps (‘partaker’), which is a combination of part or pars (a ‘piece’) and capere (‘to take’). Particeps came from a translation of the Greek word metokhe, of the same meaning, ‘partaker’. The noun particeps became, in verb form, participare, which in English became our verb ‘participate’. Thus our three standard definitions describe three different states of existence: to give, to receive, and to empathetically incorporate something of a thing's essence.

I suggest that we need to synthesize these three meanings to come up with a fully adequate definition of 'participate', one that is suitable as the basis for a new worldview. They are clearly compatible, and form a complete picture of interaction: I give something of my essence, I receive something from another, and I possess it, I incorporate it into myself. The participator takes something of the essence of that which he participates with, and makes it his own. And likewise in the reciprocal sense, he gives something of himself to the other. This view prefigures one of my central premises, that there is no such thing as one-directional participation, that all participation is bidirectional. It is a simultaneous give and take, an exchange. This exchange is essential to understanding the participatory nature of reality. Exchange is the process by which we are bound to others, by which we are connected with other individuals, with humanity at large, and with nature.

With this expanded notion of participation in hand, I will explore an important point: that exchange, even if of limited duration, causes the 'emergence' of something from the background noise of the universe - both a form of being and a form of mind. To the extent that this emergent being breaks into awareness, we may say that it appears as a new feature of the world. In this way we may say that participation is creation.

As I have already alluded to, participation and the Participatory Worldview can be seen in contrast to the Mechanistic Worldview. A central characteristic of the Mechanistic Worldview is objectivity. Consider by way of comparison the meaning of ‘objective’. It has a dozen or so meanings, including “free from personal feelings or prejudice”, “unbiased”, “dealing with things external to the mind”. Objective is a form of ‘object’, which comes from the Latin sources obicere, or obiectum. This in turn is derived from ob- (‘towards’) and jacere (‘throw’), so the combined meaning is “something thrown towards one”. So in its adjective form, to be ‘objective’ is “to throw a thing in front of someone, to place a hindrance in the way, to oppose”. Thus, by this interpretation, the “objective” Mechanistic Worldview can be seen, literally, as an obstacle, as something put in front of our mind’s eye, which obscures a deeper view of nature.

There is also a more benign interpretation, one that means “to put something in someone’s way so that it can be seen, or made visible”. Perhaps the Mechanistic Worldview began its existence with this more innocent flavor, but over the centuries it has become dominant and oppressive towards other, more sympathetic approaches to knowledge. Now, to be ‘objective’ is to have the strong meaning of being “free from personal feelings” and to treat all things as if they were truly “external to the mind”. The premise of the Participatory Worldview is that this approach is both inappropriate -

nothing is truly external to mind - and damaging - as it has now become destructive of society and the natural world.

Participation is, of course, a fact of everyday life. We all are continuously participating in society and in the larger natural world. We participate in culture, in business, in politics. We exchange our thoughts, ideas, products, wastes, energy. We even exchange ourselves, by physically moving from home to business, to the market, to a favored holiday destination. As a ‘social animal’, our sense of identity and personhood is intimately bound to the manner in which we participate in the world at large.

But participation occurs not only in the human sphere. Taking the expanded definition I offered above ('to possess deeply something of the nature of a thing, and simultaneously to give something of oneself'), then participation occurs throughout the natural world. Clearly all animals, as active, responsive entities, are participators, strongly within their given species, less strongly with other animals and plants in their ecosystem. They even participate to a degree with the soil, rain, and air; animals take in oxygen and water, exhale carbon dioxide and perspiration, and return their bodily wastes to the Earth. And then, by a principle of ‘participatory symmetry’, it is apparent that plants, soil, air, and water also participate in the natural world. They each give something of themselves to other parts of the ecosystem, and they receive into themselves something from the ecosystem.

Thus there is a sense in which all objects in the world participate with other objects around them. The natural world -- the world of physical objects, of matter and energy -is a participatory world. Participation is a completely and entirely natural process. To this statement, one might counter that participation in this sense doesn’t mean very much, that it is the same as saying that the physical world is continuous, is causally connected, and so on, nothing more than what contemporary physics tells us about the world. This would be true, except for two critical, and related, points: one, mind is seen as having a fundamentally interactive role, and two, participation in my sense claims that, through exchange, something emerges from the background: a sense of unity and identity among the participants. The nature of this unity and identity will become clearer as I proceed.

So if the world of matter participates, we can rightly speak of Participatory Matter as being a constituent of reality. By 'matter', here, I mean simply in the sense of modern physics -- the ‘physical matter’ of the universe, considered to consist of mass and energy. Participatory Matter is one fundamental aspect of what we may call Participatory Reality.

There is a second, equiprimordial aspect to Participatory Reality. This is mind -- the mind of the participator, and the mind that emerges through participation. Participation necessarily involves a subject: the one-who-participates. More often than not we use the word in reference to people, occasionally to animals, and only rarely if ever to inanimate things. If we consider the common anthropocentric usage, participation is something done willingly by a person. The person actively and freely chooses to join in with an activity, to share in something, or (more passively) to accept something. Thus there is an element of agency, of deliberate action, on the part of the subject. If we disallow for the moment instances of ‘unknowing’ or ‘unwilling’ participation, we may say that to participate is to make a mental, conscious decision to become involved. Even in this basic sense, ‘mind’ plays a key role.

Furthermore, there is the deeper sense in which the participatory process itself is seen as mind-like. In the human realm, we freely choose to become, if only for a time, one member of a larger group. We give something to others, we receive something from them, and in the process we achieve something not possible without such an interaction. This 'something' that emerges from the group also has a mind-like nature, not unlike that of our own individual minds. Ultimately, I will argue that the mind of the individual and the mind of the process are of one nature, and describable in similar terms.

Thus, despite claims of the 'eliminativist' school of philosophy, I take mind to be an eminently real phenomenon of the world. It coexists with, for example, our physical bodies, yet it itself seems not to be physical. There is the ancient question in philosophy as to whether mind reduces to, or is logically entailed by, the physical, or whether mind is something completely distinct which must interact with the body. I deny both these alternatives, and will pursue a different theory in which they are connected yet distinct aspects of reality. At this point, let me simply state that I see mind as real, as nonphysical, and as equiprimordial with matter. I shall refer to mind in this sense as Participatory Mind.

These two equiprimordial realms seem to dominate our experience of Participatory Reality. However, I do not claim that these are the only aspects of Reality. There may well be others, perhaps infinitely many so. In fact, we have some interesting evidence for at least a third distinct aspect of Reality, as I will explain in Part III. But for the most part I will adopt a rather Spinozist orientation, accepting the view that something like Mind and something like Matter are essentially all we know about the total Reality.

To summarize: in what we may call Participatory Reality, there exist at least two fundamental features -- Participatory Mind, and Participatory Matter. The two are intimately connected. Let me introduce two new terms to address these concepts: taking the Latin bases, we may call the realm of Participatory Mind the ‘Partimens’; and similarly, we may refer to the realm of Participatory Matter as the ‘Partimater’[8]. So we have the Partimater comprising the physical world of mass and energy, and the Partimens comprising the world of mental states and mind, and these two realms together constituting, in essence, all that we commonly call real.

4) Wheeler, Skolimowski, and the Modern Origins of the Participatory Worldview

The philosophical application of the term 'participation' is very old, going back at least to ancient Greece. Plato, for example, explored the ways in which the contingent physical world participates in the realm of the Forms (more on this in the following section).

Other early intellectuals advanced ideas related to participation as well, emphasizing the active power of Mind or the ontological commonality of all things. The concept of participation continued to evolve in various forms up to modern times. Into the 20th century, thinkers such as Schiller, Levy-Bruhl, and Merleau-Ponty saw significance in the idea of participation. Merleau-Ponty, for example, related it to the Heideggerian sense of

'being-in-the-world': "we are linked in relationships with ourselves and others. In short, we experience a participation in the world..." (1945: 395).

But the term ‘participation’ in reference to a new worldview has decidedly modern origins, and goes back to 1972. During the week of September 18, in Trieste, Italy, there was a conference of physicists called the “Symposium on the Development of the Physicist’s Conception of Nature in the 20th Century”. Among those attending was the avant-garde physicist, cosmologist, and philosopher John Archibald Wheeler. Wheeler had been engaged in high level theoretical physics for many years, addressing issues of particle physics, quantum mechanics, black holes, and other esoterica. He was rarely content to perform mere theoretical analysis, and one can find in most Wheeler articles at least some degree of philosophical inquiry, of putting his physical insights into a larger perspective.

Wheeler’s presentation, published the following year, was titled, “From Relativity to Mutability” (Wheeler, 1973). His main point was that the laws of physics are dependent on the structure of space-time, and that, since the universe of space-time is predicted to collapse at some point in the distant future, the laws of physics themselves must ‘collapse’, change, and become transcended: “With the collapse of the universe, the framework falls down for every law of physics.” (p. 241). Therefore, “Ultimate MUTABILITY is the central feature of physics.” (p. 242). Thus, relativity, gravity, black-body radiation, all must be “given up” as ultimate principles of the physical universe.

So, he argues, “almost everything goes”, and , “if law goes, what can replace it but chaos?” (p. 243) Wheeler is led to the belief that the universe must return to a state of “primordial chaos”, a “pregeometry”, from which law can be rebuilt[9]. Interestingly, Wheeler claims that not everything must be cast to the winds upon the collapse of the universe; even amidst this ultimate chaos, “one principle remains, the quantum principle.” (ibid) The reasons for this are partly technical, partly subjective assessment, but he is clear in his conviction on just how central the quantum principle is to any possible universe.

Then on the last page of the article he articulates for the first time a cornerstone of his emerging philosophical vision:

Nothing is more important about the quantum principle than this, that it destroys the concept of the world as ‘sitting out there’, with the observer safely separated from it by a 20 centimeter slab of plate glass. Even to observe so minuscule an object as an electron, he must shatter the glass. He must reach in. He must install his chosen measuring equipment ... Moreover, the measurement changes the state of the electron. The universe will never afterwards be the same. To describe what has happened, one has to cross out that old word ‘observer’ and put in its place the new word ‘participator’. In some strange sense the universe is a participatory universe. (pg. 244)

Thus does Wheeler introduce the modern conception of the Participatory Worldview.

It must be kept in mind that Wheeler’s context is that of physics, and he was not the first to recognize these implications of quantum mechanics. The essential ideas go back to Heisenberg and Bohr. They too argued that 'measurement changes reality'. But they did not fully appreciate the philosophical consequences, and did not articulate the larger implications.

Wheeler refers to quantum mechanics, and in particular, the Schroedinger wave equation. This equation describes the time evolution of a subatomic particle, and it does so, like all other laws of physics, in completely deterministic terms -- until one attempts a measurement. Then, in some interpretations, there is a ‘collapse’ of the wave equation, in which one of many possible futures of the particle becomes realized. Such quantities as the particle’s position or momentum (energy) do not become precise, or perhaps do not even exist, until someone makes a conscious decision regarding what and how to measure, then “reaches in”, takes the measurement, and thus actively affects the state of the particle - and hence the universe.

Wheeler senses the philosophical implications here. He goes on to ask, “Are we ‘actually bringing about what seems to be happening’?” He then quotes Parmenides: “what is, ...is identical with the thought that recognizes it” (ibid). Wheeler’s idea here is that ‘mind’ participates in, and in a sense determines, ‘matter’. Or as I may put it, the Partimens co-evolves with the Partimater, and co-defines it. As a final observation, Wheeler acknowledges that he is at the limit of what can be explained by physics alone: “Now more than ever one is certain that no approach to physics that deals only with physics will ever explain physics.” (ibid). In other words, metaphysics is essential to understanding the universe.

Throughout the 1970’s and early 1980’s, Wheeler continued to promote and articulate his conception of the participatory universe -- see particularly his articles “Universe as a Home for Man” (1974), “Genesis and Observership” (1977), and the compilation piece “Law without Law” (1983). In "Genesis and Observership", Wheeler describes the universe as giving rise to the observer-participator, who in turn brings meaningful existence to the universe. The central point, reiterated in subsequent articles, is that “billions upon billions of acts of observer-participancy [are] the foundation of everything” (1981: 186).

Wheeler does not explicitly tell us who or what is making the observations. To my knowledge, in all his writings Wheeler consistently maintains an anthropocentric stance, never considering whether, for example, animals or plants can act as observerparticipants and create meaningful existence. Nor does he consider the reciprocal effect back on the participator[10]. These seem to me to be key elements of a fully-developed participatory worldview, and hylonoism provides this missing dimension.

I have offered up Wheeler as a leading figure in the development of the terminology and present conception of the Participatory Worldview. Actually, the vision of the participatory universe was anticipated some five years before Wheeler’s 1972 conference by the philosopher who has made the most progress in articulating the philosophy of participation, Henryk Skolimowski. In December of 1967 Skolimowski attended and presented at the 2nd International Colloquium on Biology, History, and Natural Philosophy, in Denver. Skolimowski’s contribution was titled, “Epistemology, the Mind, and the Computer”, which was subsequently published, coincidentally, in 1972 (see Skolimowski, 1972). In this paper Skolimowski argues against materialist reduction of the mind to physics, and instead challenges us “to be bold and imaginative and propose theories which account for the complexity and intricacy of [mental] phenomena but which are less susceptible to direct empirical scrutiny.” (p. 303).

After presenting a number of arguments against the premise of ‘strong artificial intelligence’ -- that a computer can duplicate the capabilities of the human mind -- Skolimowski articulates a theory of interaction between knowledge and the mind. For Skolimowski, ‘knowledge’ is the sum total of our understanding of reality; in a sense, for us, it is reality[11]. He writes in terms of “scientific knowledge”, but the reference is clearly to all fundamental knowledge of reality. Skolimowski’s central point is that there is a continuous interaction between mind and knowledge, such that both are evolving and changing together. He states, “There is a parallel conceptual development of the content of science and the inner mental structures of the mind.” (p. 325). Knowledge works on the mind, and conversely, mind changes knowledge. He lays out his position concisely:

At this point we must assume that there is a parallel conceptual development of our knowledge and of the mind. Knowledge forms the mind. The mind formed by knowledge develops and extends knowledge still further which in turn continues to develop the mind. Thus there is a continuous interaction between the two [K]nowledge and mind are

functionally dependent on each other and indeed inseparable from each other. They are two sides of the same coin ... (ibid)

The linkage between these two is language: “In language we witness the culmination and crystallization of two aspects of the same cognitive development: one aspect related to the content of science [i.e. knowledge]; the other aspect related to our acts of comprehension of this content [i.e. mind].” (p. 324). Thus, via language, mind interacts and co-defines itself with knowledge of reality.

At this early point in his conception of the participatory mind, Skolimowski had not yet substituted ‘reality’ for ‘knowledge’, but this comes out clearly in his later writings. But there are hints of this view even here in his early work: “Every new hypothesis is an invention of a new possible world.” (p. 327). Skolimowski also seems to understand the broader implications that are unfolding. He introduces the term “conceptual net” to represent “the totality of concepts and their relationships” (p. 325). This is a clear reference to the idea of a ‘worldview’, of a total picture of reality. He compares the conceptual net to Kuhn’s “paradigm”, but states that “the conceptual net is more comprehensive than the paradigm; it determines not only the nature of scientific problems but also the nature of scientific frameworks, or paradigms” (p. 328).

Something larger and broader than a paradigm is emerging from this view of mind; it is a total picture of the cosmos, a truly new worldview that was captured five years later by Wheeler with his phrase “participatory universe”.

Skolimowski became aware of Wheeler's ideas in the mid-70's, at which point he was in the midst of developing a highly-original version of environmentally-based philosophy known as 'eco-philosophy'[12]. He returned to the subject of participatory mind in a seminal 1983 article, "A Model of Reality as Mind". Here Skolimowski makes the key replacement of ‘reality’ for ‘knowledge’. He further articulates his theory of mind, called here the “evolutionary transcendental theory” of mind, or more briefly, the “ecological theory”. Skolimowski is clearly laying out a radical new vision of mind, and the role that mind plays: “there is a most intricate feedback between reality and mind; that each codefine the other, and indeed reality can be conceived as a form of mind” (p. 774; my italics). He argues that mind is not just active, it is creative -- or more precisely, cocreative: reality forms and molds the mind, and likewise mind creates meaningful reality. Furthermore, reality, as a "form of mind", possesses certain powers of cocreativity. After all, the brain - which is the central organ of the mind - is obviously a part of material reality, and must play a key role in the process of knowing. One is led to ask, in what sense does this one piece of material reality (the brain) co-create with reality, and how does it compare to other parts of material reality, or matter in general.

Skolimowski does not address this issue; hylonoism attempts to illuminate it.

In Skolimowski's interpretation, the means through which mind co-creates are its sensitivities. The person is conceived as consisting of a “field of sensitivities” through which we interact with our environment. Our evolution is essentially the story of evolving sensitivities, the acquisition of ever-greater abilities to know the world. The sensitivities include the five bodily senses, but also incorporate all our mental abilities for grasping and internalizing the world. Until we absorb into ourselves a piece of reality, that piece, for us, simply does not exist: “No eye to see, no reality to be seen.” And furthermore, the visual reality brings the eye into existence:

The existence of the eye and the existence of the visual reality are aspects of each other. One cannot exist without the other. For what is the seeing eye that has nothing to see? And what is the visual reality that has never been seen? ... There is no more to reality (for us) than our sensitivities can render to us. (pgs. 777-8)

Skolimowski stresses the error of the conventional objectivist view of reality as existing ‘out there’, independent of how it is perceived:

What is beyond the [human] species and the mind of the species may be reality in potentio but not reality as we know it; our concept of reality is reality as we know it In processing [reality], the mind actively transforms reality ... There is no such thing as reality as it is... Reality is always given together with the mind which comprehends it... We have no idea whatsoever what reality could be like as it is, because...reality is invariably presented to us as it has been transformed by our cognitive faculties. (pp. 779-80)

Two other interesting and relevant points in this article: one, Skolimowski denies that his theory of mind is a version of philosophical idealism, preferring to coin a new term: “The ecological theory of mind is not an expression of old-fashioned idealism which denies or mystifies reality. It is rather an expression of suprarealism. For it accounts for all the stages of the real in its evolutionary unfolding...” (p. 782). (Idealism, as a philosophical concept, is the view that all things are fundamentally 'mind', or are reducible to mind).

The other point of interest is that Skolimowski does not cite Wheeler and his participatory universe proposal, choosing instead to make a passing reference to the concept by noting that, in the new worldview of particle physics, “the observer and the observed merged inseparably” (p. 787). This is as close as he gets here to directly citing the concept of ‘participation’, although the meaning and intent clearly permeates his ecological theory of mind.

Things begin to change just one year later when he publishes The Theatre of the Mind (1984). Here one finds explicit reference to the new terminology: “Thus we live in the participatory universe, not in the objective one.” (p. 15). Yet, the concept of participation still plays a minor role here; he discusses it once more briefly at the end of the book (p. 161) where he cites the Wheeler passage quoted above. Skolimowski furthers his commitment to the concept the following year, when he presents (in 1985) a lecture titled, “The Co-Creative Mind as a Partner of the Creative Evolution”[13]. He embraces the new terminology, referring to his theory as the “participatory-evolutionary mind”, and making reference to the “holistic-participatory cosmology” and the “evolutionary-participatory logos” (1988: 58). And, he broaches the concept of a specific mode of investigative inquiry based on this new participatory philosophy, which he calls “the Methodology of Participation” (p. 59). It was in the spirit of this fundamentally new research methodology that programs such as ‘participatory action research’ were initiated in the 1980’s.

Over the next few years Skolimowski continued to develop his vision of a participatory philosophy -- see his (1991, 1992, 1993). His thinking culminated in 1994 with the release of an entire book dedicated to articulating his new philosophy, The Participatory Mind. Along with his Eco-Philosophy (1981), this is probably his most original and profound work. I provide a detailed analysis in Chapter 6, but briefly, Participatory Mind puts forth a radically new ontology in which mind and reality are seen as two aspects of a single entity, "mind/reality"; this theory Skolimowski calls "noetic monism". His

participatory ontology leads to a complete worldview, in which theories of epistemology, methodology, and truth are united under the framework of participation.

Let me just note here that Wheeler and Skolimowski are not the only recent figures to emphasize the philosophical importance of participation. Physicist David Bohm took up Wheeler's suggestive ideas and further explored the role of participation in quantum mechanics - see my discussion in Chapter 7. Berman (1981) examines the importance of the idea of participation, and Abram (1996) also sees it as an essential part of a new worldview. Reason and Rowan (1981; and Reason, 1994), among others, see in it the basis for a completely new approach to research methodology[14]. Again, these works will be explored in subsequent chapters.

5) Some Early Elements of Participatory Philosophy

Skolimowski and Wheeler made explicit the philosophical concepts surrounding participation as I have defined it here, but they each had their own intellectual predecessors. For Wheeler it was the cutting-edge physicists and the architects of the 'new physics', those who had the vision to articulate the deeper meanings of their discoveries -- people like Bohr, Heisenberg, Schroedinger, Everett, and Wigner. For Skolimowski it was the line of philosophers who saw mind as actively engaged in determining the nature of reality, and who challenged the dominant ontology of materialism -- James, Bergson, Whitehead, Popper, and Teilhard; not to mention the inspiration of the early Greek thinkers.

Both Skolimowski and Wheeler represent the culmination of these two broad lines of inquiry -- those of philosophy and the physical sciences, respectively. This split is a relatively recent phenomenon. Prior to the mid-1800’s science and philosophy were much more closely related, and individual thinkers more likely to be expert in both fields -- and to create original and insightful ideas. People such as Gustav Fechner (1801-1887) and Ernst Haekel (1834-1919) were among the last to creatively integrate both the

scientific and philosophical perspectives of nature. It is, in fact, one of my objectives in this thesis to further reunite insights from these two now-divergent lines of inquiry.

An examination of the physical sciences branch requires a detailed look into aspects of physics, and this I defer until later. Likewise, the philosophical branch calls for an examination of the relevant ideas from several individuals. This is best addressed in conjunction with the whole line of philosophical thought known as panpsychism, which stretches from its early origins in ancient Greece, through the Renaissance and Baroque periods, into modern times; the entire of Part II is dedicated to this task. In the remainder of this introductory chapter, I return to the beginning of Western thought. I briefly examine a few ideas of the early Greek philosophers, to see how they set the stage for the development of a Participatory Worldview.

Participatory thought in ancient Greece was, naturally, quite different from that envisioned by Wheeler and Skolimowski. It did, though, possess the general qualities of sharing, of partaking, and of interacting. As such, the Greeks were the first to articulate the beginnings of the concept of Participatory Reality. As with panpsychism, this aspect of their thought is generally under-examined and under-appreciated, in part because it is seen as superficial or irrelevant in light of the physicalist worldview that has dominated modern philosophy over the past 100 years.

Broadly speaking, the Greek concept of participatory philosophy generally, and panpsychism in particular, can be examined in three parts: that of (1) the pre-Socratics, (2) Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, and (3) the Stoics[15]. Here I want to make just a few brief observations on the first two of these groups, beginning with the pre-Socratics. Of the perhaps 20 or so major philosophers who lived before the time of Socrates, three contemporaries stand out as envisioning an active, participatory role for mind -Parmenides, Anaxagoras, and Empedocles.

Parmenides (515-460 BCE) was the leading figure among the group of philosophers known as the Eleatics. He was the first to focus directly on mind and its active role in the world. In his principal work, "On Nature", Parmenides advocates the view that the stuff of the 'objective' world is really an aspect of mind, and is actually in a sense equivalent to mind. Writing on the ancient Greeks, T.V. Smith makes special mention of Parmenides' "concept of Being, which he identified with thought" (1934: 9). In a key fragment, Parmenides states that "thinking, and that by reason of which thought exists, are one and the same thing..." (ibid, pp. 16-17). This identification of being and mind is among the very first hints of a participatory worldview within Western philosophy. Mind, in some sense, is equated with reality; therefore, no mind, no reality. This insight was inspirational to both Wheeler and Skolimowski, and both have cited it.

Anaxagoras (500-428 BCE) expanded on this notion of an active mind, making it the centerpiece of his entire philosophy. For him, mind is the central ordering principle of the world. In the words of Smith, "According to Anaxagoras, there is a countless number of original elements, qualitatively unchangeable, which are combined and separated by the ubiquitous power of mind." (p. 27). This view comes out in the fragments of his writing; the following quotes are from Fragments 6 and 7, as cited in Smith:

And whatever things were to be, and whatever things were, as many as are now, and whatever things shall be, all these mind arranged in order; .

[M]ind ruled the rotation of the whole, so that it set it in rotation in the beginning. . Rotation itself caused the separation. And when mind

began to set things in motion, there was separation from everything that was in motion, and however much mind set in motion, all this was made distinct. (p. 34)

Interestingly, this view of mind as the central ordering principle of the universe was apparently compelling to the young Socrates. In the Phaedo, Socrates exclaims, "[Anaxagoras' theory of mind] delighted me and it seemed to me somehow to be a good thing that mind was responsible for everything ." (97b-c). Even though Socrates later abandoned this view - "this splendid hope was dashed" - it was because Anaxagoras had failed (in the mind of Socrates - or was it perhaps only Plato?) to address certain key implications, and not because of any inherent weakness in the position itself. Intuitively, Socrates (and perhaps Plato as well) evidently felt that this was on the right track.

Empedocles (495-435 BCE) was the dominant figure of the pre-Socratics, from a participatory-panpsychist viewpoint. So many of his ideas were seminal to later thinkers, and there are a number of deep and profound intuitions in his work. His writing focused more on aspects of panpsychism than on the explicit role of the human mind, and I will cover these ideas more thoroughly later. One fragment is relevant for my purposes here, and it is based on Empedocles' belief that we know things by virtue of sharing a like nature. Both we ourselves and the objects around us share in certain common fundamental elements: these are the four material elements of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire (which Empedocles was the first to articulate). It is through our common participation in these basic elements that we are connected to things, and that we, in a sense, bind and merge with them. In a famous and beautiful passage he says:

For by earth we see earth, by water water, by ether bright ether, and by fire flaming fire, love by love, and strife by mournful strife." (cited by Aristotle, De Anima, 404b11).

'Love' and 'Strife' are the two fundamental forces in the Empedoclean system, and again it is through mutual participation that we come to know these. This passage is the earliest known articulation of the view that 'like knows like', and is one of the first formulations of a participatory epistemology. Knowledge is seen as possible only by mutual participation in the common elements of reality.

Turning to the dominant Greek thinkers: Socrates, as we know, was not much of a metaphysician. He dwelt more on the moral aspects of philosophy, and on the nature of the 'good life'. His method of teaching, however, was unique; the famed Socratic Method of inquiry was highly interactive and cooperative, and focused on joint learning in the context of the individual student rather than on the expounding of eternal truths. This approach embodies the essence of participatory inquiry. Socrates was in fact the first practitioner of a participatory methodology, the spirit of which carries on today in the field of 'participatory action research'[16].

Plato (428-348 BCE) was perhaps the first explicitly participatory philosopher. In a number of works he develops his famous theory of the Forms - ideals of Justice, Beauty, Being, and so on, of which each specific instance in the 'real' world is a reflection or image. The relationship between things and the Forms is described by Plato as one of participation, as things partaking or sharing of the Forms.

We find this most notably in two of his dialogues, the Phaedo and the Parmenides. In the Phaedo, Plato writes of "sharing" in the Forms. For example, he says, "[I]f there is anything beautiful besides the [Form of] Beautiful itself, it is beautiful for no other reason than that it shares in that Beautiful" (100c). And a bit later he elaborates:

[Y]ou do not know how else each thing can come to be except by sharing in the particular reality in which it shares, and these cases you do not know of any other cause of becoming [for example] 'two' except by sharing in Twoness...as that which is 'one' must share in Oneness... (101c)

Then in Parmenides he switches over explicitly to the term 'partake' to describe this type of interaction between things and Forms. A youthful Socrates is explaining his ideas to his elder teacher, Parmenides: "[A]ll things are 'one' by partaking of oneness, and that these same things are 'many' by partaking also of multitude ... I’m one person among the seven of us, because I also partake of oneness." (129b-c). Socrates goes on to explain that "these forms are like patterns set in nature, and other things resemble them and are likenesses; and this partaking of the forms is, for the other things, simply being modeled on them." (132d). Participation is thus seen by Plato to have a deep metaphysical significance, as the process by which the Ideal is incorporated into the Phenomenal.

This must suffice as a brief prelude to the concept of participation. I hope to have shown in this cursory introduction something of both the earliest and latest thinking on the subject. As I have indicated earlier, two central precursors of participatory thought - panpsychism and modern physics - require separate and detailed treatment later. It remains for me to connect these temporally and conceptually distant ideas, and form a cohesive picture of participatory philosophy in the 21st century.

At this point I return to recent developments, and explain in some detail the mathematical basis for my hylonoetic theory. Although this is counter to the chronological order, I think it is more helpful to have in mind the main elements of hylonoism as I explore the relevant history of panpsychism. The reason for this is that both concepts help to illuminate the other. Having in place a hylonoetic theory of mind, I can give a new reading to many ancient ideas. In fact, there are a number of surprising similarities between hylonoism and the various panpsychist theories of mind that I examine. I take this as a positive sign; for if there is an underlying truth to panpsychism, we should expect to find similar insights made by thinkers of all ages. And in fact we do.

The basis for hylonoism is centered on the process of exchange between systems of mass and energy. As such, it is helpful to inquire deeper into the history and meaning of these two terms. This is the primary subject of my next chapter.

Deconstructionists argue that all such attempts contain internal contradictions that preempt their validity. They see all larger schemas as culturally and temporally relative (in spite of their own claims that they are not relativists). Ultimately, this is a futile position; worldviews do exist, and they are the set of the largest, deepest shared assumptions about the world within a given culture. There is a grain of truth in the deconstructionist position, in that no worldview is 'ultimate' or absolute. Worldviews evolve, interact, and change. Whether individuals can in fact affect this process is a different issue, which I cannot address here.

PAR is an outgrowth of the older concept of ‘action research’ that originated in the work of Kurt Lewin in the 1930’s and 40’s (for a good overview and history, see Greenwood and Levin, 1998). Lewin began the break from the assumption of ‘dispassionate researcher’ and instead sought to use research to change and improve social systems. He involved himself in the experiment, and made clear his intentions to play an active role. As early as the mid-1930’s he wrote of the importance of “action wholes” (1935: 173), and shortly thereafter he discussed the role of “directed action” and “action toward the goal” (1938: 108, 129) with respect to motivations of human behavior. Later he moved toward a group-consensus approach that sought not just knowledge per se, but an improvement or resolution in a problem situation (see Lewin, 1946); his was an activist methodology.

Less well known is that Lewin’s action research was grounded in the pragmatist philosophy of the late 19th century. Peirce (1878) was the first to argue that the primary end of philosophy is action; truth and meaning were to be found in “practical consequences” (1905/1934: 6). James, Schiller, and Dewey further elaborated this ‘action philosophy’ that emphasized the real-world effects of inquiry. Philosophy was not some pursuit of an abstract, ‘objective’ reality but rather was a process of co-creating reality, one that could be measured in terms of human satisfaction and well-being. Lewin took this philosophical principle and applied it to actual research.

Action research went largely dormant in the 1950’s and 1960’s, but resurrected in the late 70’s. By the early 80’s the term ‘participatory’ came into play, to express the active involvement of the researcher(s) and participants. Additionally, PAR came to incorporate an ideological commitment toward inclusion, empowerment, and social justice. Not only was it “value driven” (Levin, 1999: 27), but it recognized the inherent role of values in all types of research, including the supposedly 'value neutral' approach of the scientific method. PAR embraces the role of values, and as such is able to work toward equitable and life-enhancing solutions. Works such as Reason and Rowan (1981), Whyte (1984), and Reason (1988) were among the first articulations of PAR. In 1997 Heron and Reason (1997) performed a relatively comprehensive study of the philosophical basis for participatory research, drawing upon the work of Skolimowski, Berman, Abram and others.

Chapter 2 - Concepts of Mass and Energy in Western Civilization

1) Matter and Motion

Throughout the remainder of this thesis, I will be making increasing references to basic concepts of physics -- especially, the concepts of 'matter' and 'energy' -- so it is appropriate at this point to go into some detail regarding the meaning of these and other related terms. I will avoid a technical discussion, limiting my approach to the philosophical implications of these concepts. Let me also add that I will take these two concepts in a relatively straightforward manner, as it is not my intention to make a deep metaphysical inquiry into what precisely we mean by the terms 'matter' and 'energy'. I treat these concepts essentially as modern science does, presuming that there is some meaningful sense in which we can quantify them and their effects. My main intention is to develop the philosophical significance of the basic elements of the physical world as it pertains to the emergence of the phenomenon of 'mind' in particular and to the Participatory Worldview in general.

The universe of the contemporary physicist is a world of material objects, and of energy. Matter and energy exist in a realm of 3-dimensional space, and they endure with varying degrees of stability throughout time. Matter and energy have been unified by relativity theory into a single substance, 'mass-energy'. Space and time have been unified, also by relativity theory, into a single 4-dimensional entity, 'space-time'. Thus, the modern physicist sees a universe that is quite simple and elegant: mass-energy (in various forms) moving through space-time.

This is the essence of the materialist worldview. Nothing exists except mass-energy, and space-time. Anything else, and anything not ultimately describable in terms of these elements, is unreal.

To better understand the full implications of a mass-energy universe, I will first explore the history of these concepts. The study of matter and energy goes back to the earliest days of our civilization. The ancient Greeks were among the first in human history to take a deep, rational look at the world around them, and to attempt to draw some general conclusions. In striving to understand the natural world, the Greek philosophers sought out the essential principles of nature; they asked the most basic questions; and they sought to unify the diversity of phenomena into a single comprehensive theory or vision.

Their line of inquiry was shaped by the primordial worldview into which they were born. This determined the starting point. As with many early cultures, the Greeks inherited a worldview of diverse material objects ruled and influenced by a pantheon of gods. This worldview seemed to account for human and natural events in a semi-comprehensible manner. Then around 600 BCE certain Greek thinkers began to depart from this worldview and ask different questions. They took an intellectual 'step back', and adopted a new perspective; they saw a world that consisted, in its essence, of things that move.

Once seeing the cosmos as composed of 'things that move', two central lines of investigation open up. One naturally wants to know: (1) what is the nature of 'things': what do they consist of at root, what are their properties, and how do they acquire these properties; and, (2) what is the nature of 'movement': how and why do things move, and what is the nature of the interaction between any such 'motive force' and material objects. And in fact, much of Greek philosophy is dominated by these two general lines of inquiry. Certainly physis (physics, or the study of nature) was, and even ethics was also to a large degree shaped by one's view of the natural world; as, for example, F. Sandbach said of the Stoics, "The question of right conduct could not be settled without understanding the relation of man to the universe." (1975: 14). Even logic, the third traditional branch of philosophy, was developed in large part to make clear one's arguments about physis.