Deni J. Seymour

Fierce and Indomitable

The Protohistoric Non-Pueblo World in the American Southwest

1. “Fierce, Barbarous, and Untamed”

Dispensing with the Notion of a Hiatus

Reorienting the Protohistoric Problem

From Late Prehistory to Late History

Impact on Prehistoric Populations

Evidence of Mobile Groups: Material Culture

2. Terminal Puebloan Occupation

3. Bison, Trade, and Warfare in Late Prehistoric Southeastern New Mexico

4. Conceptualizing Mobility in the Eastern Frontier Pueblo Area

Conceptualizing Mobility in the Pueblo Area

Distinguishing Puebloan and Mobile Structures

Artifacts in the Pueblo Sphere

Additional Features around Pueblos

Puebloan Shrines around Pueblos

Shepherding Features around Pueblos

5. Eastern Extension of Lehmer’s Jornada Mogollon Ancestors to the Jumano/Suma

Jornada Mogollon—Eastern Extension: Are They Really Jumano?

6. Embracing a Mobile Heritage

Paradigm of Government-to-Government Relationships

Criteria and Standards as Interpretation of History

The Model Tribe versus Mobile Societies

What Constitutes Tribe and Community in Mobile Societies

Tribes Defined by Outsiders and an Outsider’s View of Tribe

Decentralized Leadership versus Contradictory Histories

Mobile People, Changing Profile

“Tribe” versus Flexible Social Organization

Distinct Communities: Enclaves and Reservations

Previous Research of Protohistoric Groups Nearby

Emerging Clusters of Thermal Features

8. From Economic Necessity to Cultural Tradition

Stone Tools and Economic Realities

Comparing Spanish Chipped-Stone Assemblages

9. Protohistoric Arrowhead Variability in the Greater Southwest

The Bow-and-Arrow Weapon System

Approaches to the Study of Arrowhead Variability

A Neutral Approach to the Metrics of Size and Shape

Relating Protohistoric Point Types to Their Shape Measurements

10. Akimel O’odham and Apache Projectile Point Design

Flaked-Stone Projectile Point Design

Akimel O’odham Projectile Points

Projectile Point Design Physical Constraints

Projectile Point Design Summary

Akimel O’odham Historic Period Settlement Patterns

Middle Gila Flaked-Stone Arrow Point Size

Ceramics in Sedentary and Mobile Societies

Archaeological Examples of Ceramic Assemblages of Sedentary and Mobile Peoples

12. Architectural Visibility and Population Dynamics in Late Hohokam Prehistory

Coalescent Communities Database

Two Case Studies: The Rillito Fan and Cactus Forest Sites

The SSNP Narrative on Depopulation

The San Pedro as an Opportunity for Refinement

A More Complete Network Analysis for the San Pedro

15. The Colorado Wickiup Project

Chronometric Analysis of Ephemeral Wooden Feature Sites

Pisgah Wickiup Village (5EA2740)

A Reappraisal of the Final Years of Sovereign Ute Occupancy in Colorado

16. A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage at 42UN5406 in the Uintah Basin

Description of the 42UN5406 Artifact Assemblage

Awatovi Black-on-Yellow (Hopi)

Discussion of the Ceramic Assemblage

Description of the Three Sisters Site

18. A Protohistoric to Historic Yavapai Persistent Place on the Landscape of Central Arizona

Cultural Landscape and Persistent Place Approach

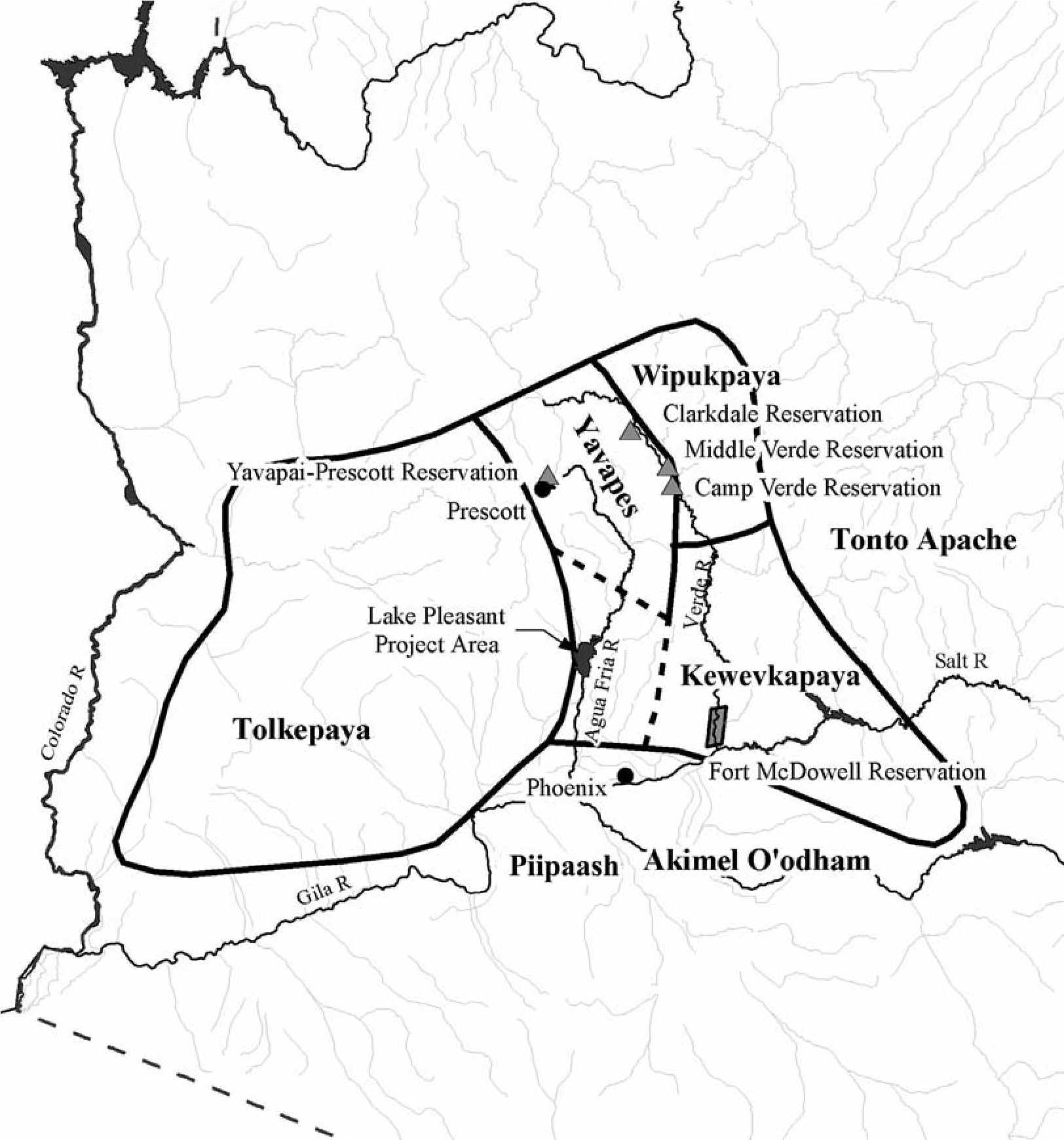

Yavapai Research in Western and Central Arizona

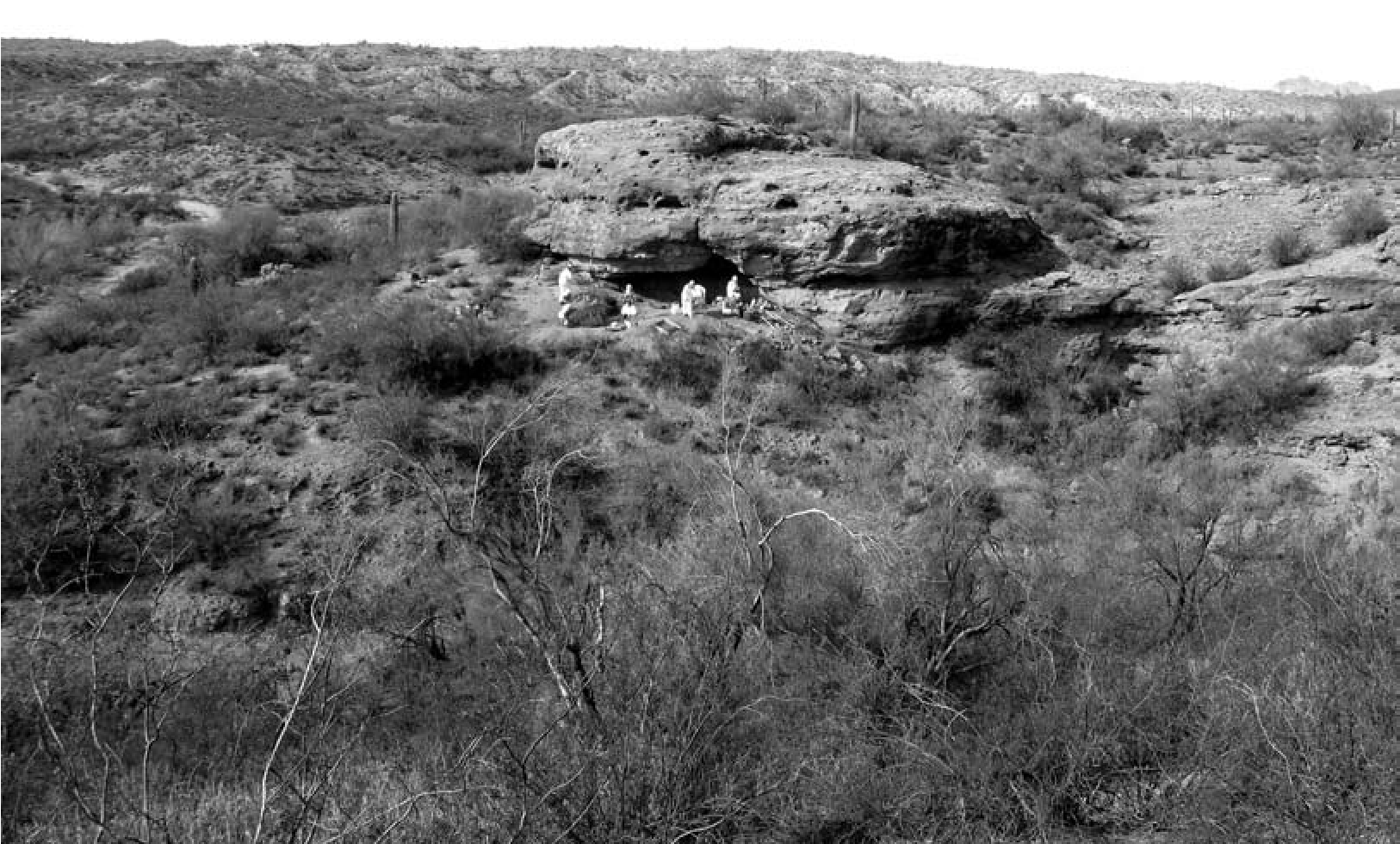

Reclamation’s Role at Lake Pleasant

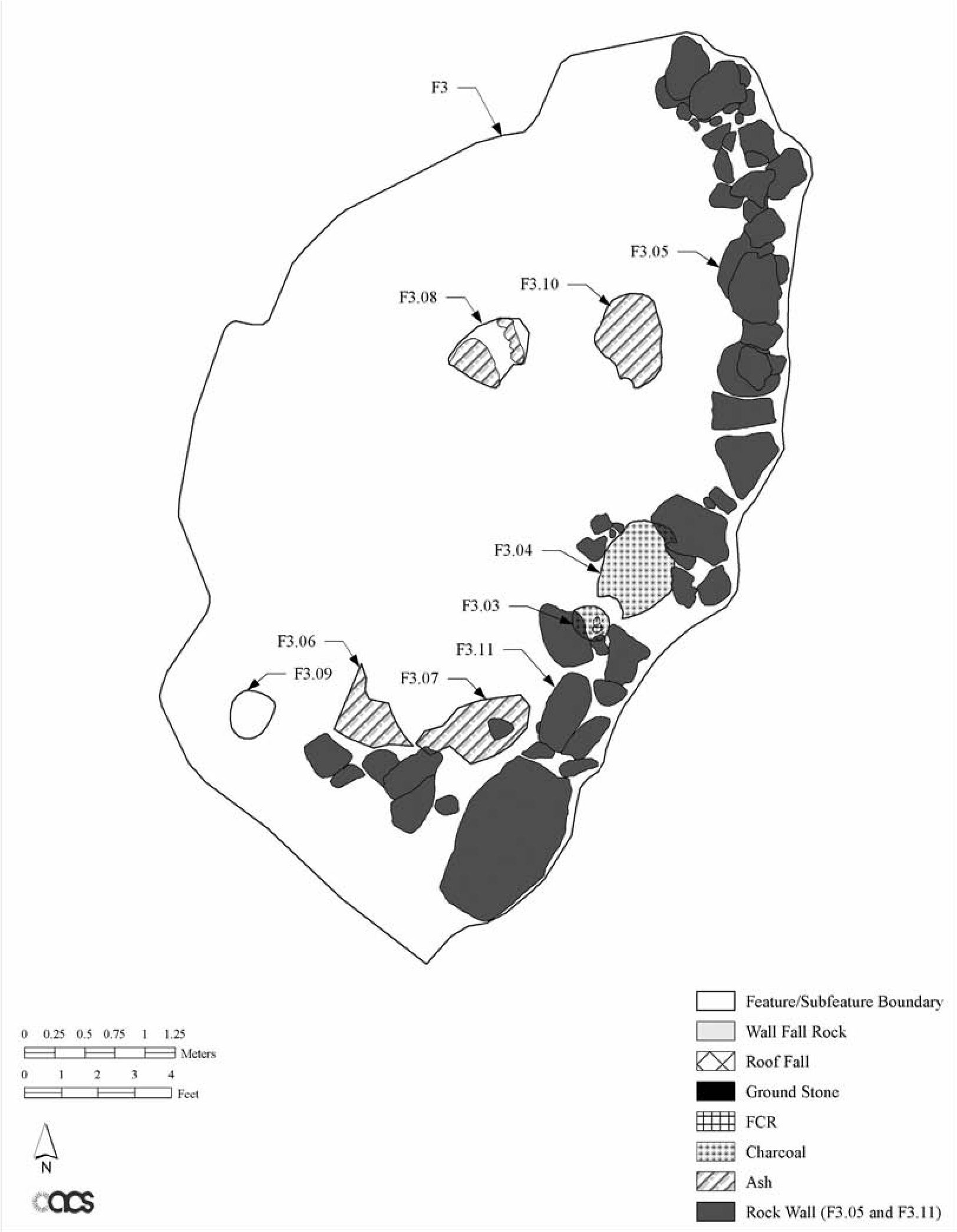

Rockshelter Excavations and Results

Yavapai Material Culture and Subsistence over Time

Lithic Artifacts and Protein Residue Analysis Results

Analysis of Protein Residue on Selected Artifacts

Envisioning a Long-Term Yavapai Persistent Place

19. Now You See ’Em, Now You Don’t

Summary of Yavapai Archaeological Work

Agave Knives (“Tabular Tools”)

AR-03-04-06-745—State Route 89A

Rock-Cleared Areas: Yavapai U-was or Natural Features?

Caveats on “Diagnostic” Yavapai Characteristics

Southern Nevada’s Environment and Chronological Framework

The Archaeological Data (ad 1300–1776)

Settlement Patterns and Systems

Cultural Boundaries and Ethnographic Groups

A Push-Pull Model for Southern Nevada

21. Tweaking the Conventional Wisdom in Southwestern Archaeology

Situating Protohistoric Archaeology

Contextualizing the Protohistoric

Simultaneously Addressing Continuity and Change

Archaeologies of Unexpected Times and Unexpected Places

Refining Protohistoric Chronologies

“Protohistoric” Interactions on the Northern Periphery

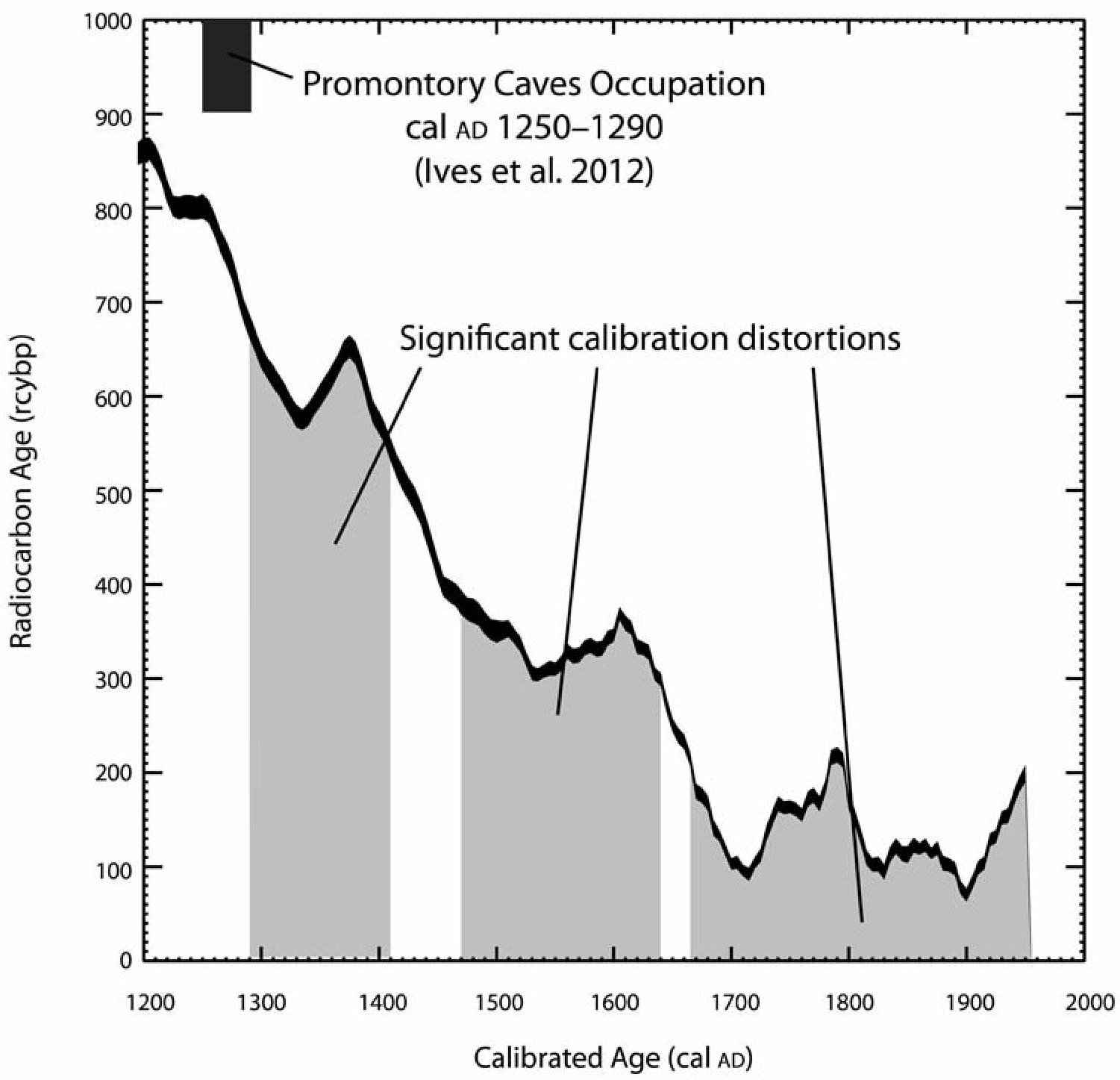

Fresh Approaches to Radiocarbon Dating

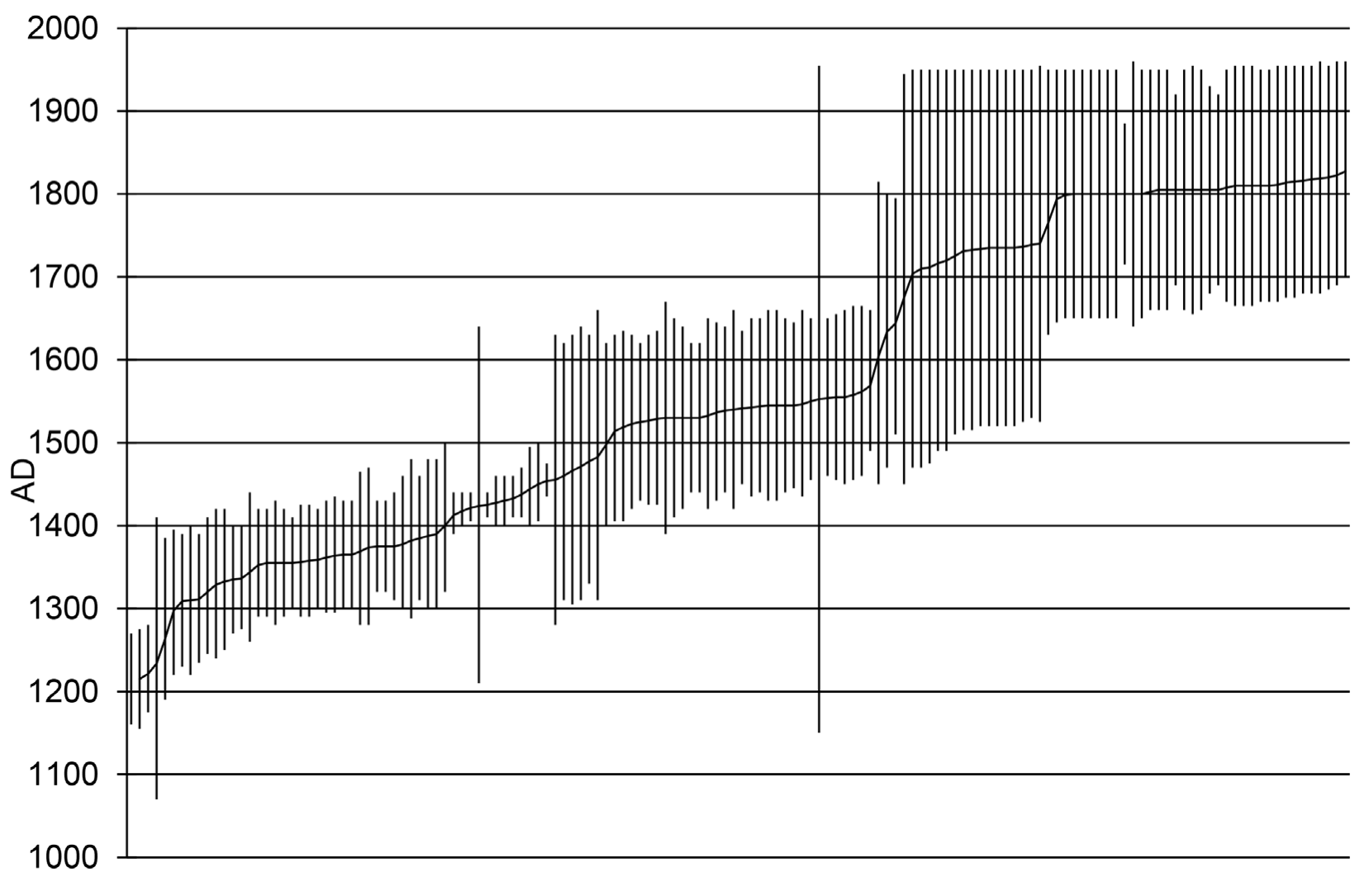

Stochastic Calibration Distortions

Defining Relevant Signatures of Mobility, Sedentism, and Ethnicity

Feature and Artifact Correlates

Defining Signatures of Ethnic Identity

An Impatience with the Conventional Wisdom

[Front Mater]

[Title Page]

Fierce

and

Indomitable

THE PROTOHISTORIC NON-PUEBLO WORLD

IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST

EDITED BY DENI J. SEYMOUR

The University of Utah Press

Salt Lake City

[Copyright]

Copyright © 2017 by The University of Utah Press. All rights reserved.

The Defiance House Man colophon is a registered trademark of the University of Utah Press. It is based on a four-foot-tall Ancient Puebloan pictograph (late PIII) near Glen Canyon, Utah.

21 20 19 18 17 12345

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Seymour, Deni J., editor.

Title: Fierce and indomitable : the protohistoric non-Pueblo world in the American Southwest / edited by Deni J. Seymour.

Description: Salt Lake City : The University of Utah Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: lccn 2016025835 | isbn 9781607815211 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781607815228 (ebook)

Subjects: lcsh: Indians of North America-Southwest, New—Migrations. | Indians of North America—Ethnozoology—Southwest, New. | Indians of North America-Southwest, New—Antiquities. | Indians of North America-Southwest, New-Social life and customs.

Classification: lcc E78.S7 F545 2016 | ddc 979.004/97—dc23

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025835

Printed and bound by Edwards Brothers Malloy, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan.

[Dedication]

This book is dedicated to

the late David Brugge and Jane Kelley.

Both were generous, dedicated, and thoughtful scholars

whose work has been an inspiration to many.

Contents

List of Figures ix List of Tables xii Acknowledgments xiii

1. “Fierce, Barbarous, and Untamed”: Ending Archaeological Silence on Southwestern Mobile Peoples 1

Deni J. Seymour

2. Terminal Puebloan Occupation: An Example from South-Central New Mexico 16

Meade F. Kemrer

3. Bison, Trade, and Warfare in Late Prehistoric Southeastern New Mexico: The Perspective from Roswell 28

John D. Speth

4. Conceptualizing Mobility in the Eastern Frontier Pueblo Area: Evidence in Images 39

Deni J. Seymour

5. Eastern Extension of Lehmer’s Jornada Mogollon Ancestors to the Jumano/Suma 64

Patrick H. Beckett

6. Embracing a Mobile Heritage: Federal Recognition and Lipan Apache Enclavement 77

Oscar Rodriguez and Deni J. Seymour

7. Excavations in the Carrizalillo Hills of Southwestern New Mexico Reveal Protohistoric Mobile Group Camps 89

Alexander Kurota

8. From Economic Necessity to Cultural Tradition: Spanish Chipped-Stone Technology in New Mexico 106

James L. Moore

9. Protohistoric Arrowhead Variability in the Greater Southwest 115

Mark E. Harlan

10. Akimel Oodham and Apache Projectile Point Design 138

Chris Loendorf

11. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Study of the Ceramics of Protohistoric Hunter-Gatherers 154

David V. Hill

12. Architectural Visibility and Population Dynamics in Late Hohokam Prehistory 161

Douglas B. Craig

13. Sobaipuri Oodham and Mobile Group Relevance to Late Prehistoric Social Networks in the San Pedro Valley 170

Mark E. Harlan and Deni J. Seymour

14. Needzu: Dine Game Traps on the Colorado Plateau 188

James M. Copeland

15. The Colorado Wickiup Project: Investigations into the Early Historic Ute Occupation of Western Colorado 198

Curtis Martin

16. A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage at 42UN5406 in the Uintah Basin 212

James A. Truesdale, David V. Hill, and Christopher James (CJ) Truesdale

17. Three Sisters Site: An Ancestral Chokonen Apache Encampment in the Dragoon Mountains 222

Deni J. Seymour

18. A Protohistoric to Historic Yavapai Persistent Place on the Landscape of Central Arizona: An Example from the Lake Pleasant Rockshelter Site 240

Robert J. Stokes and Joanne C. Tactikos

19. Now You See ’Em, Now You Don’t: In Search of Yavapai Structures in the Verde Valley 256

Peter J. Pilles Jr.

20. It’s Complicated: Discerning the Post-Puebloan Period in Southern Nevada’s Archaeological Record 281

Heidi Roberts

21. Tweaking the Conventional Wisdom in Southwestern Archaeology 301

David Hurst Thomas

References 315

Contributors 365

Index 367

Figures

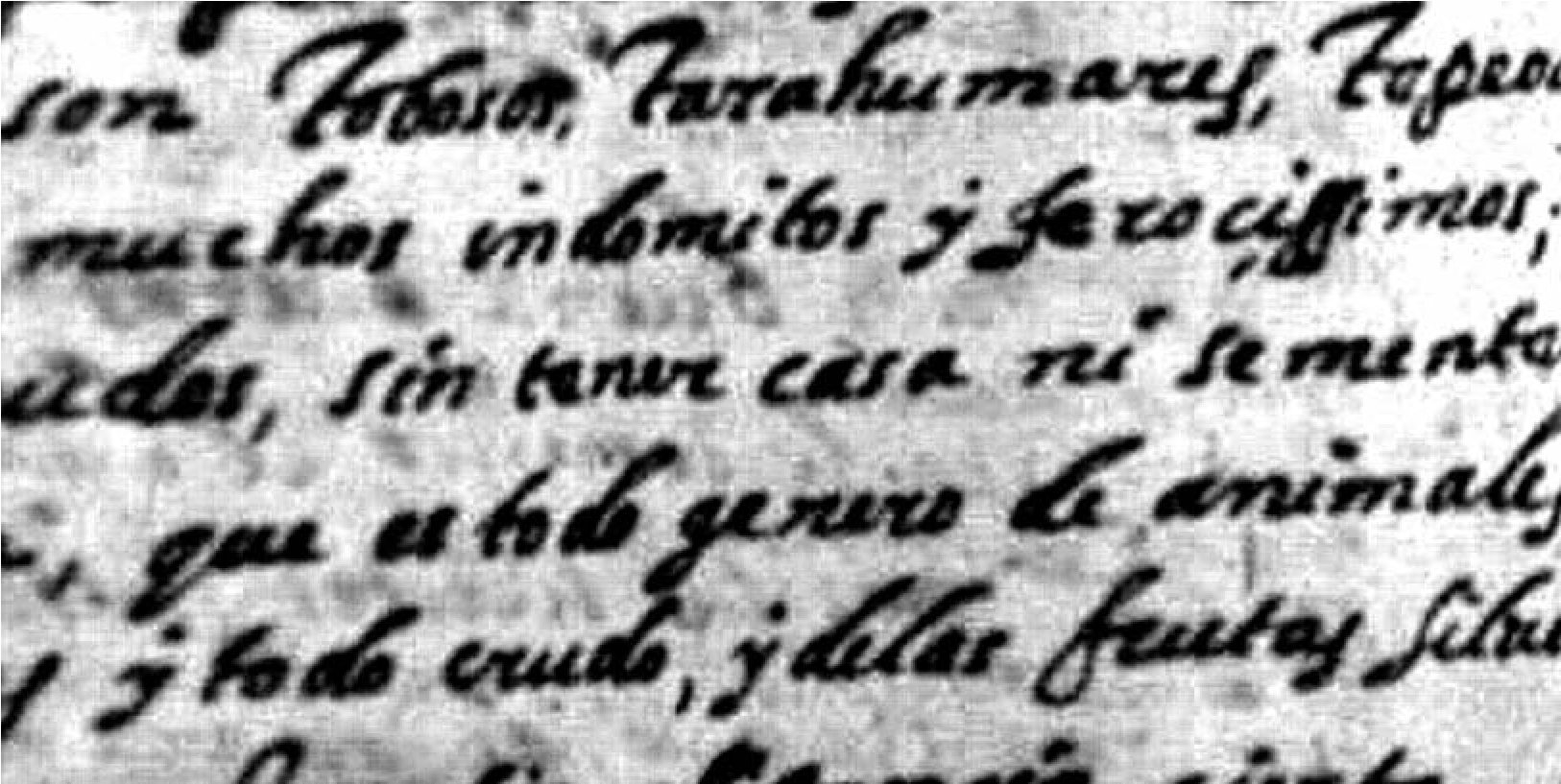

1.1. Fray Alonso de Benavides’s 1634 text describing the indios bárbaros 2

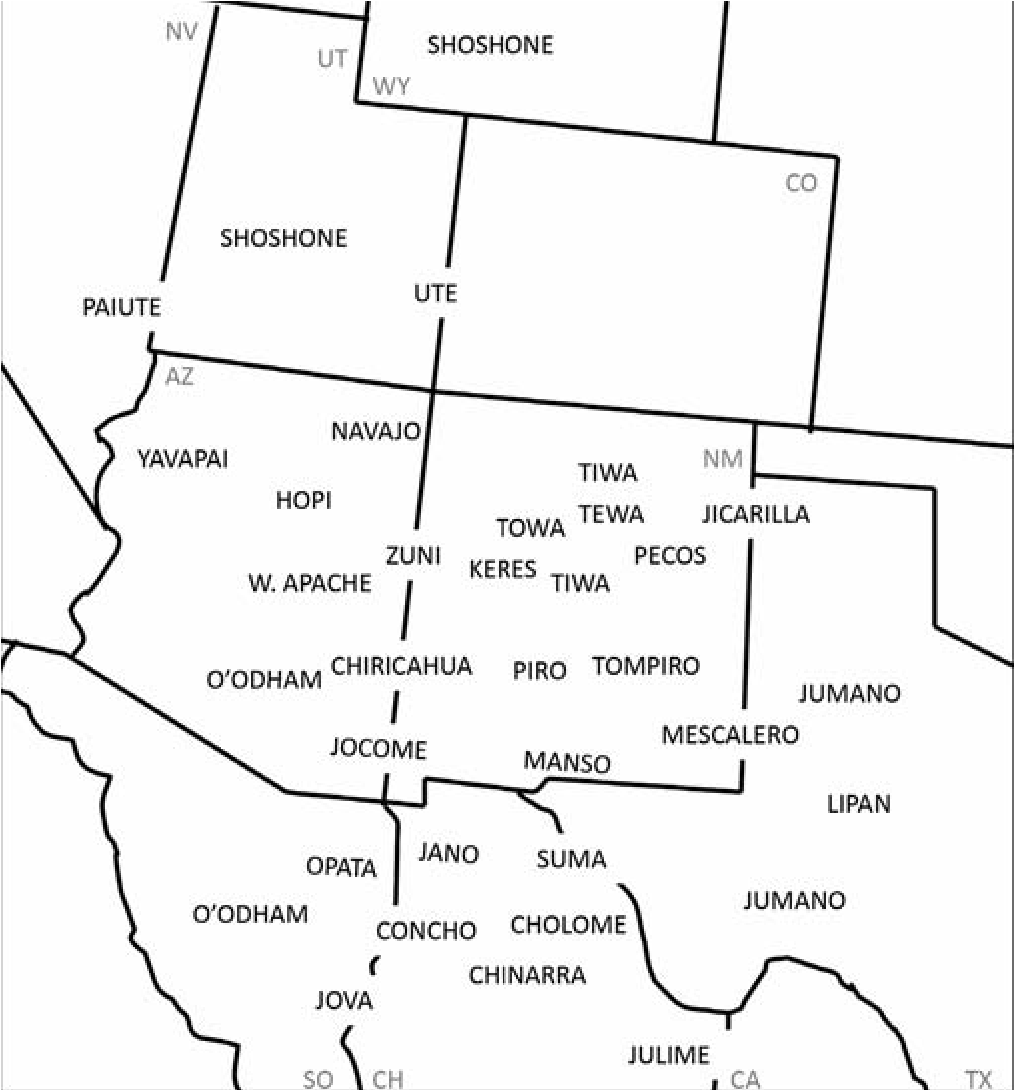

1.2. General distribution of ethnic groups throughout the Southwest 3

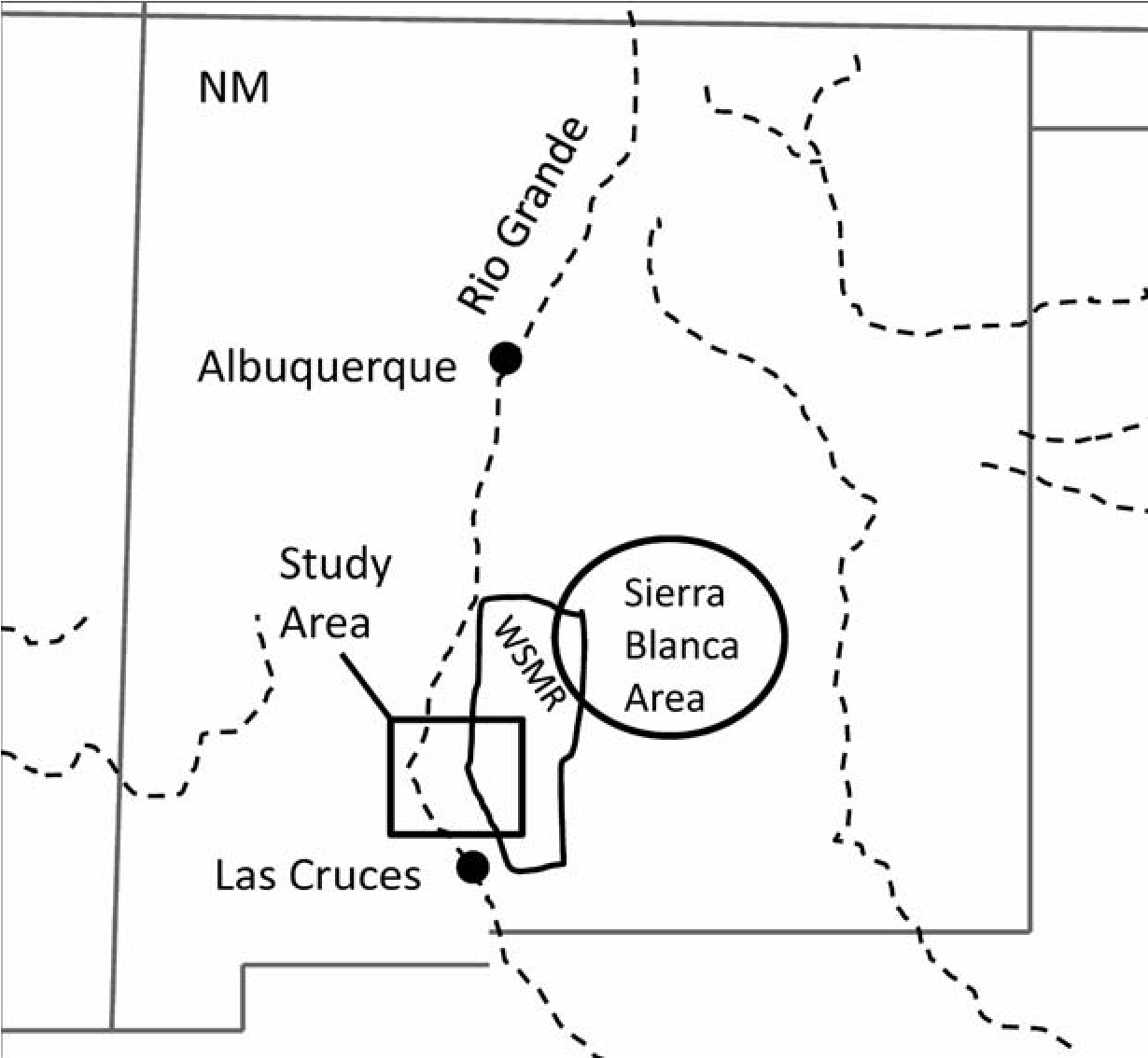

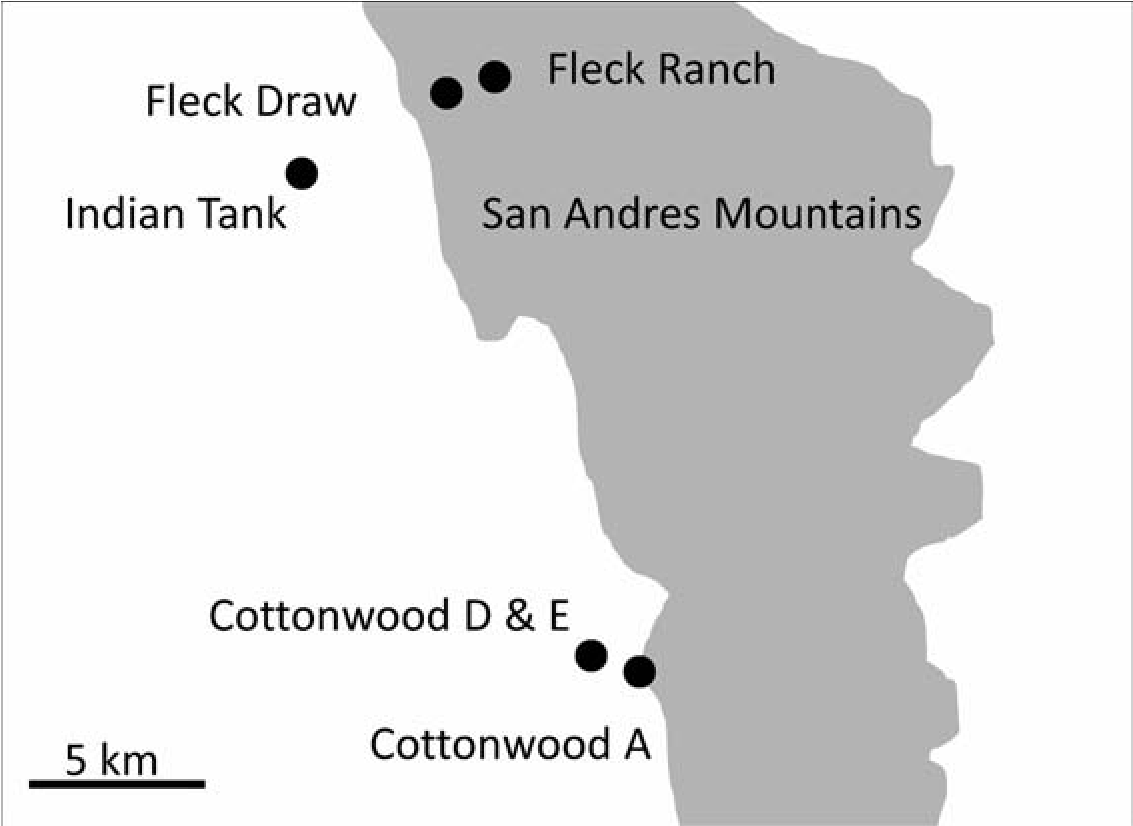

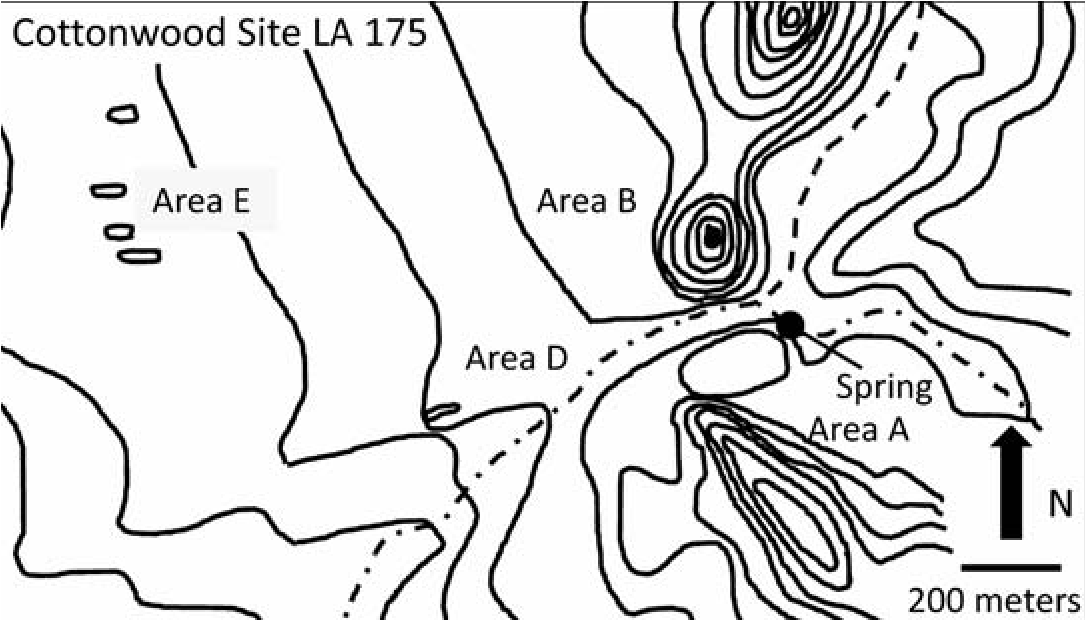

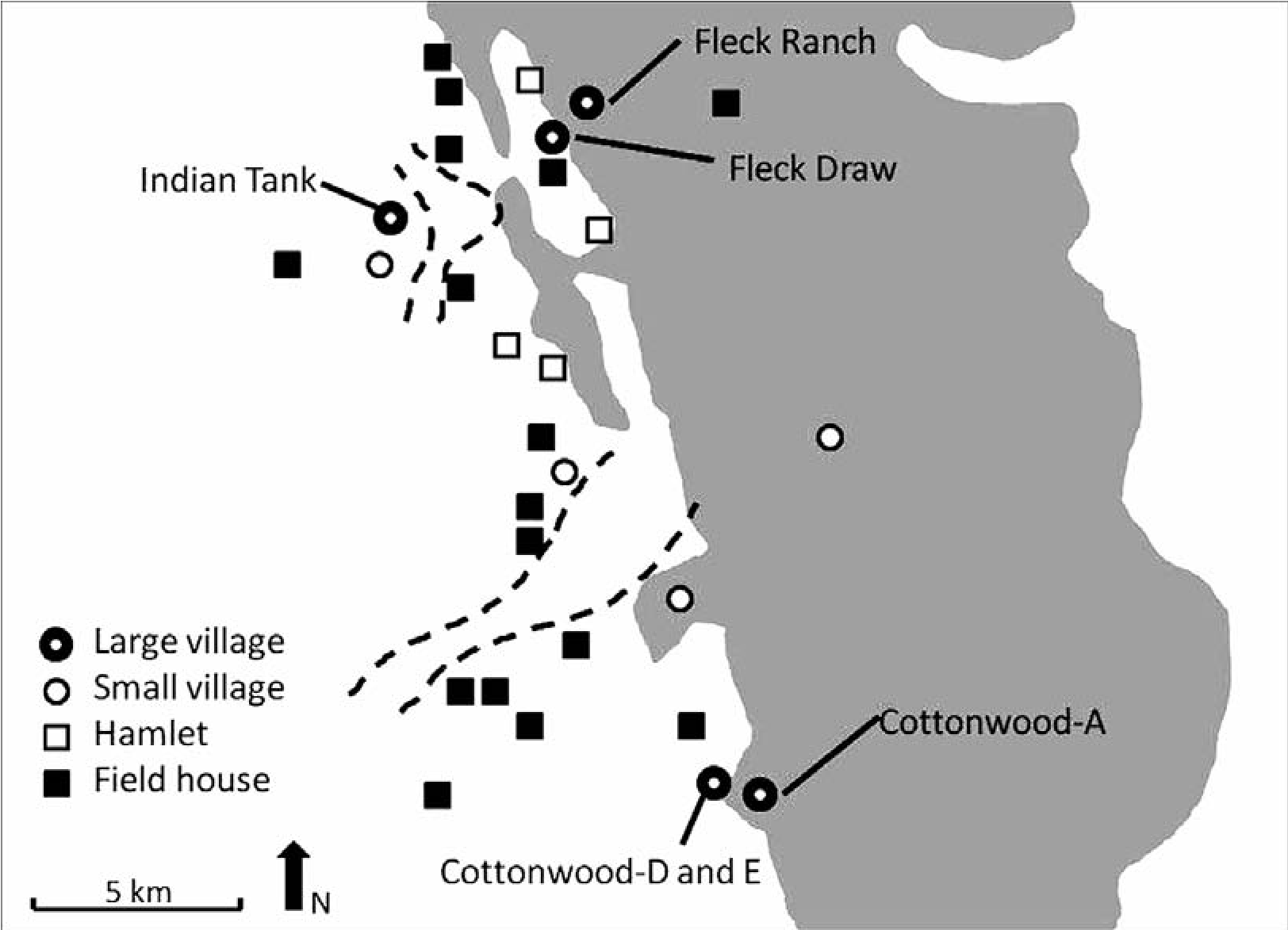

2.1. Location of the south-central New Mexico study area 17

2.2. Major villages in the southern San Andres Mountains area 18

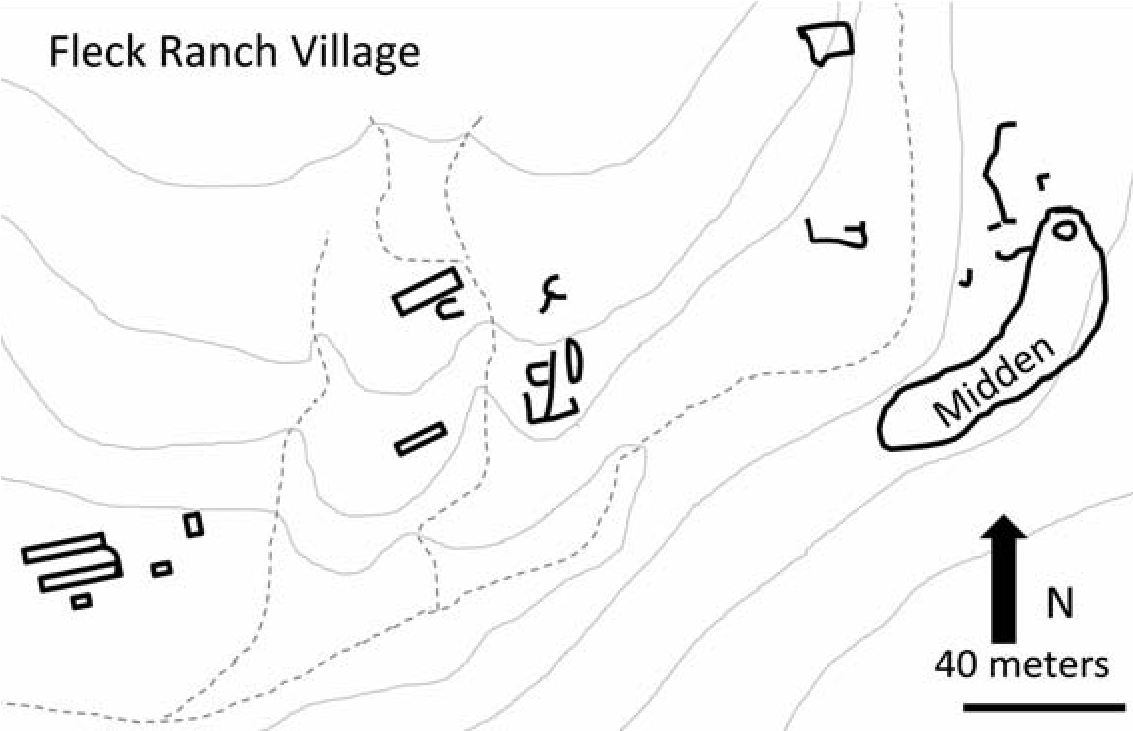

2.3. Fleck Ranch village plan map 18

2.4. Cimiento upright stone foundation at Fleck Ranch village 19

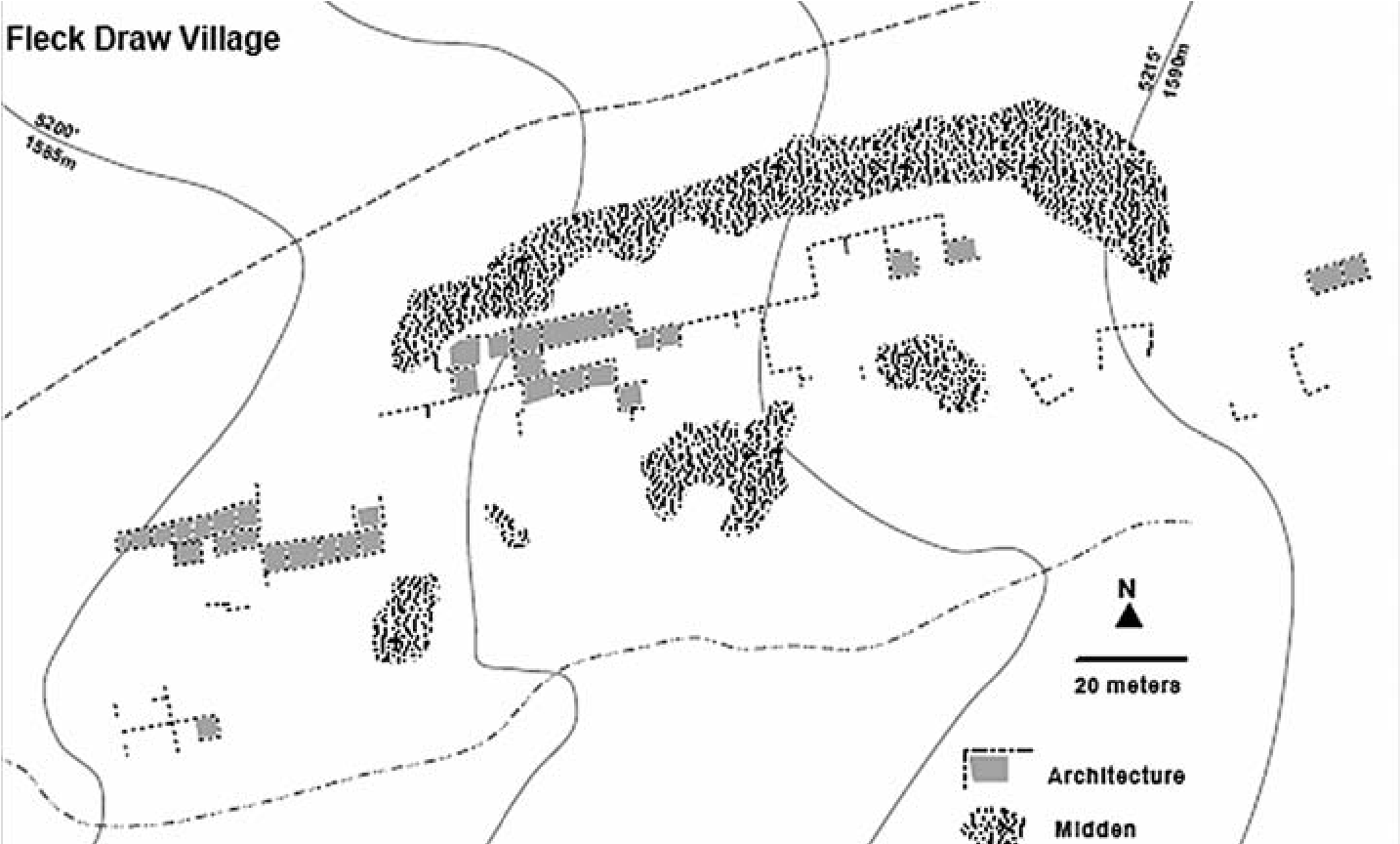

2.5. Fleck Draw village 20

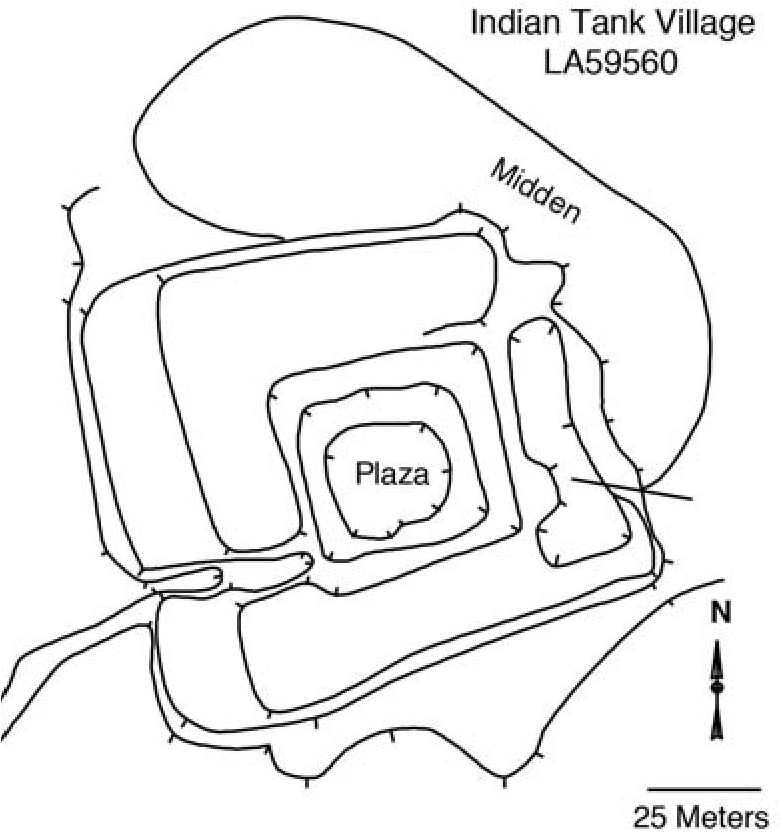

2.6. Indian Tank village 21

2.7. Cottonwood Area A village 22

2.8. The Cottonwood group 22

2.9. Late Pueblo period sites 24

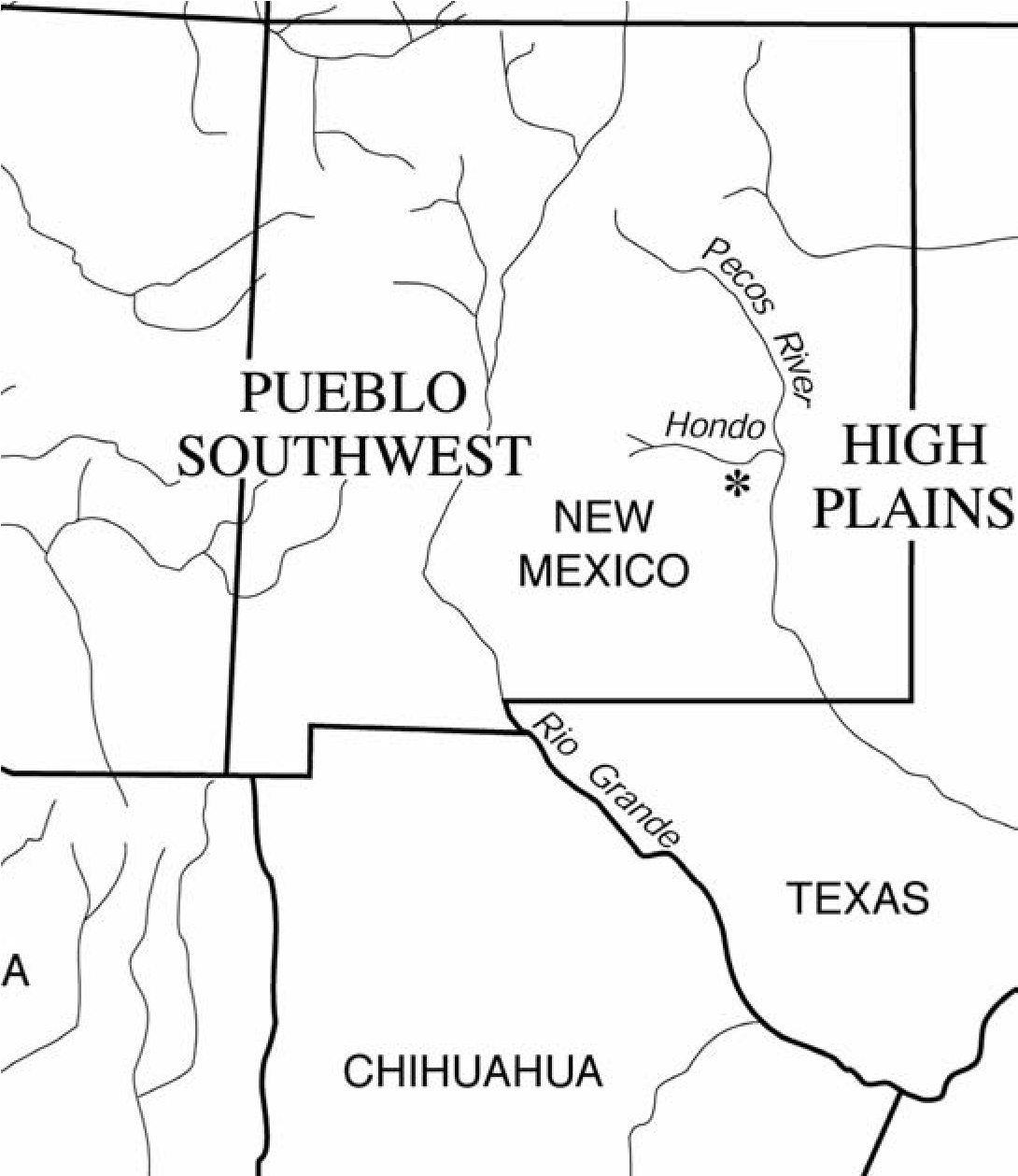

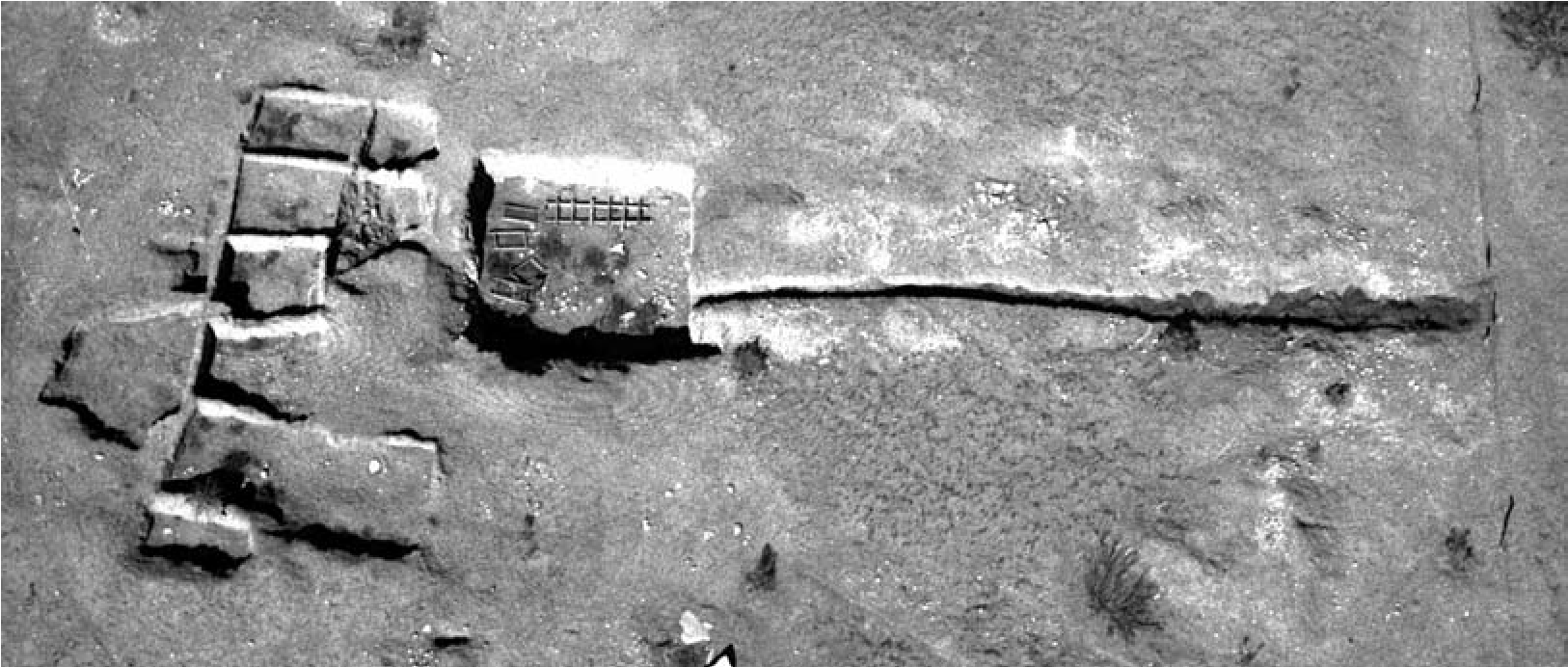

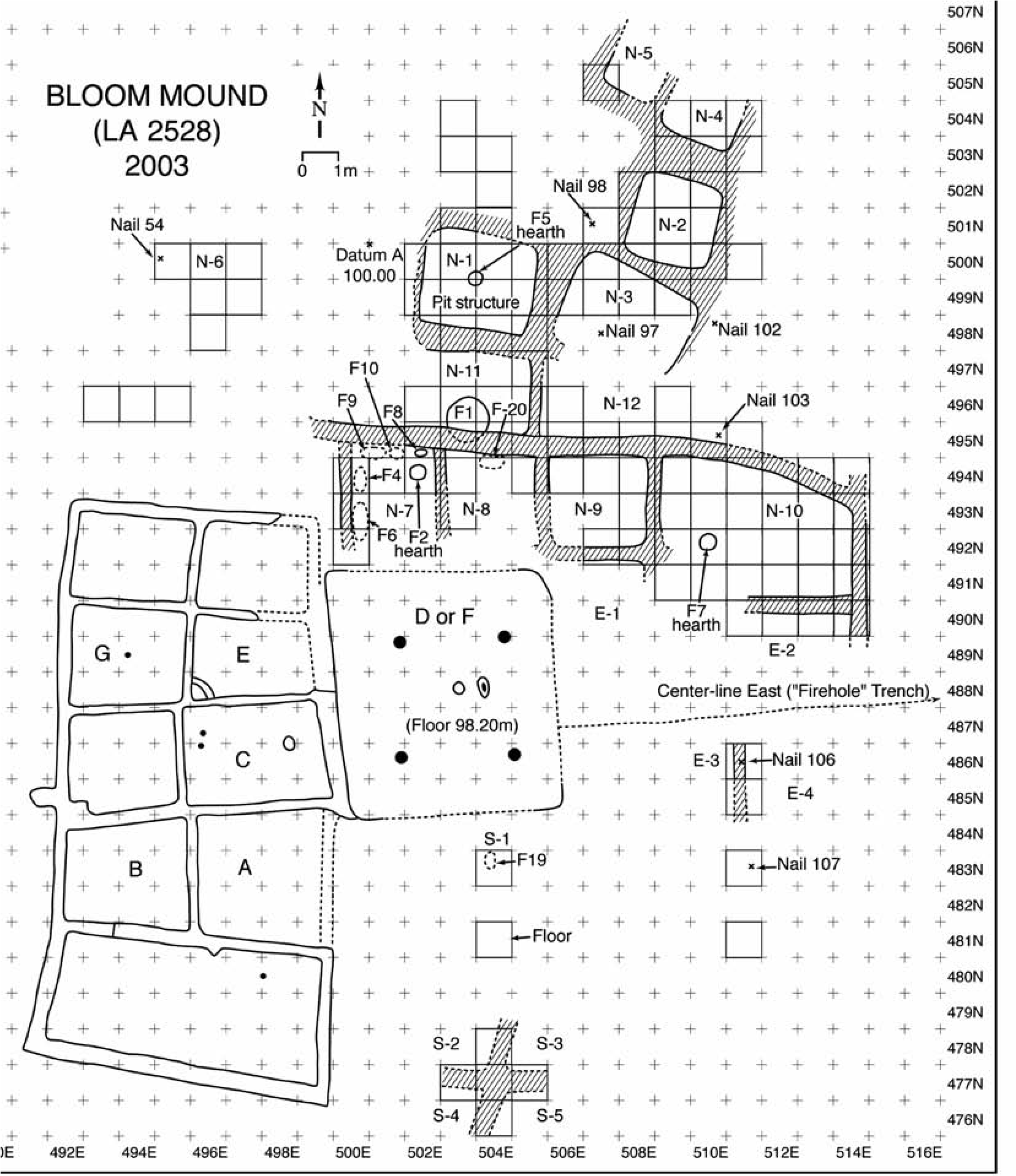

3.1. Location of the Henderson site and Bloom Mound 29

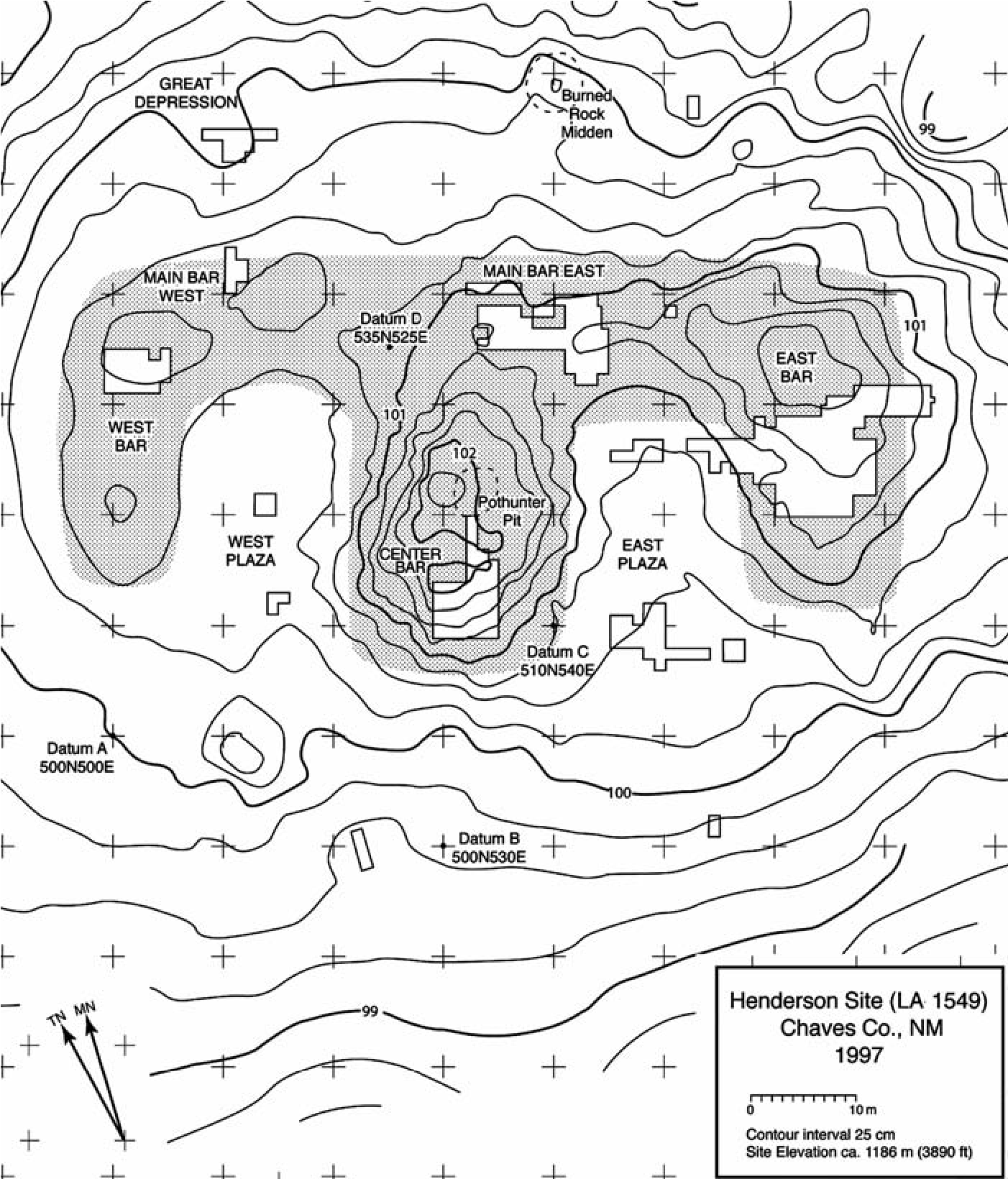

3.2. Map of the Henderson site 30

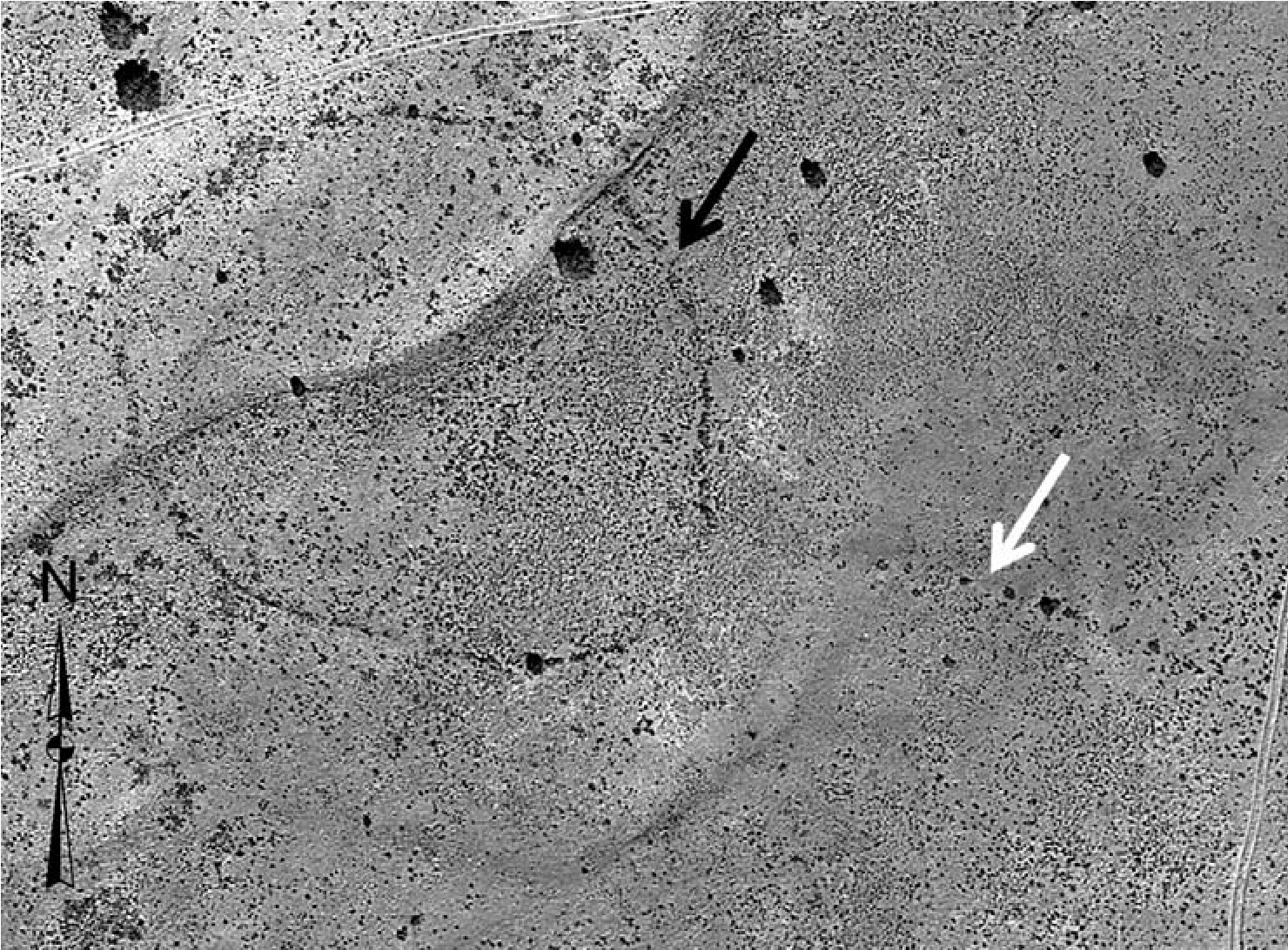

3.3. Aerial photo of Bloom Mound, 1950s 32

3.4. Map of Bloom Mound 34

4.1. Eastern Frontier Pueblos 40

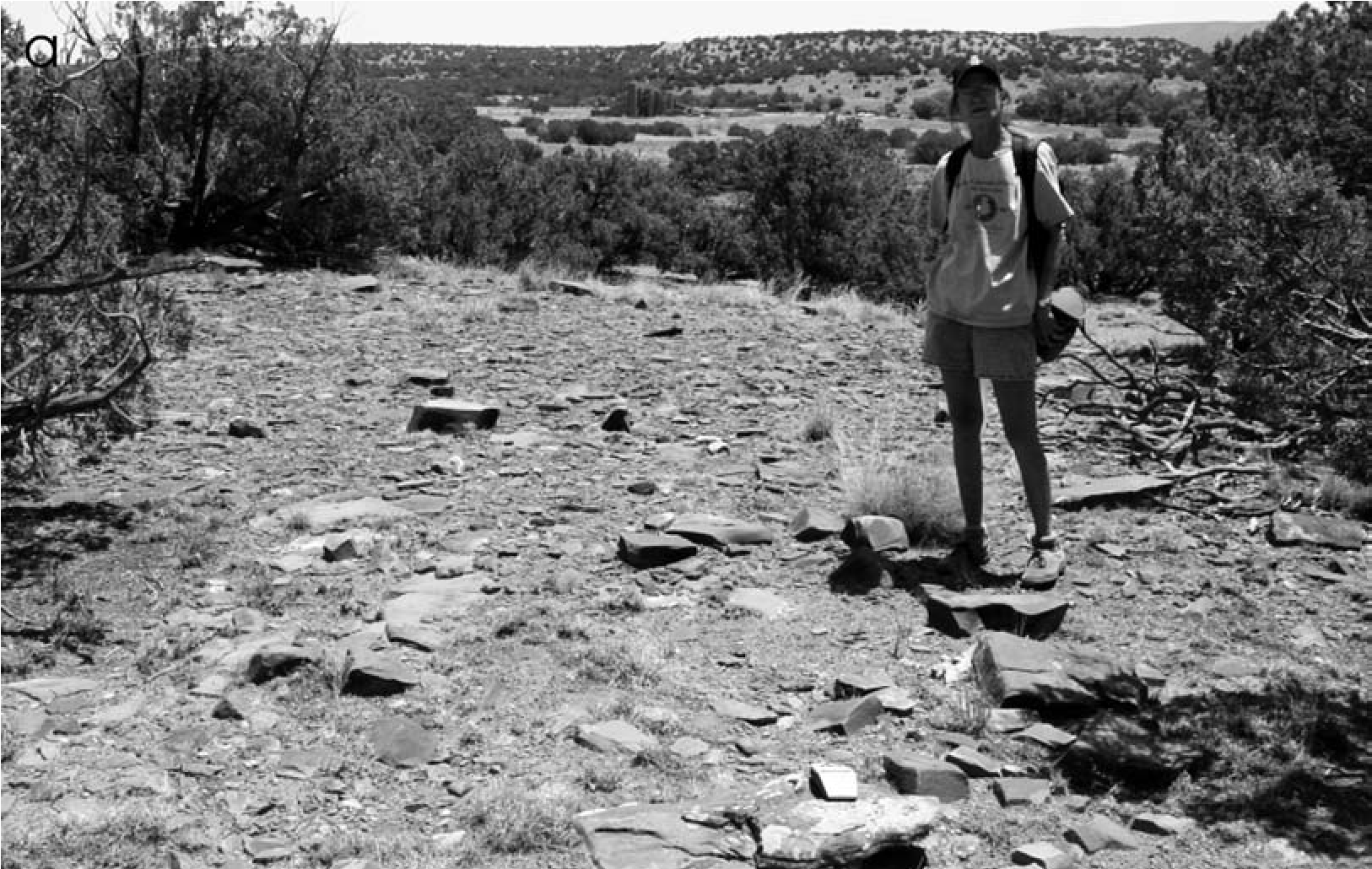

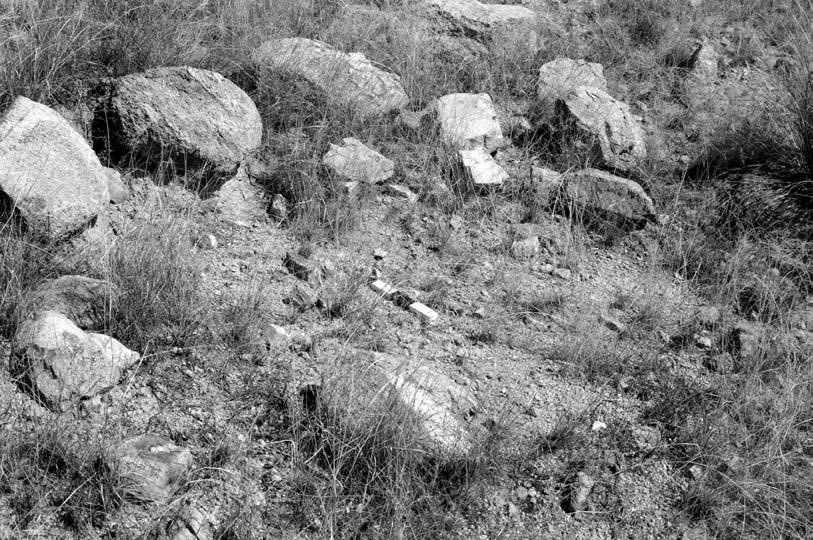

4.2. Prehistoric Puebloan rock alignment and rubble alignment 45

4.3. Prehistoric Puebloan field house and room block 46

4.4. Mobile group structure at LA 152447 47

4.5. Boulder-rimmed circles 48

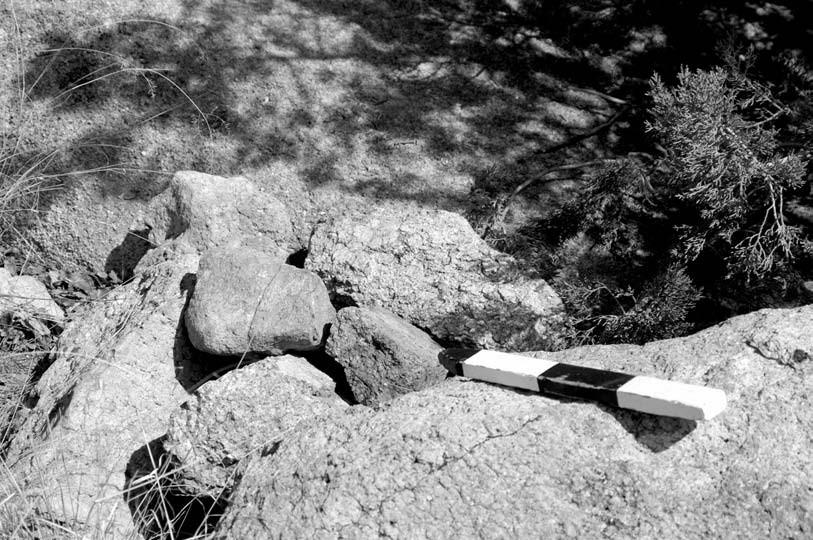

4.6. Upright slabs at LA 152447 49

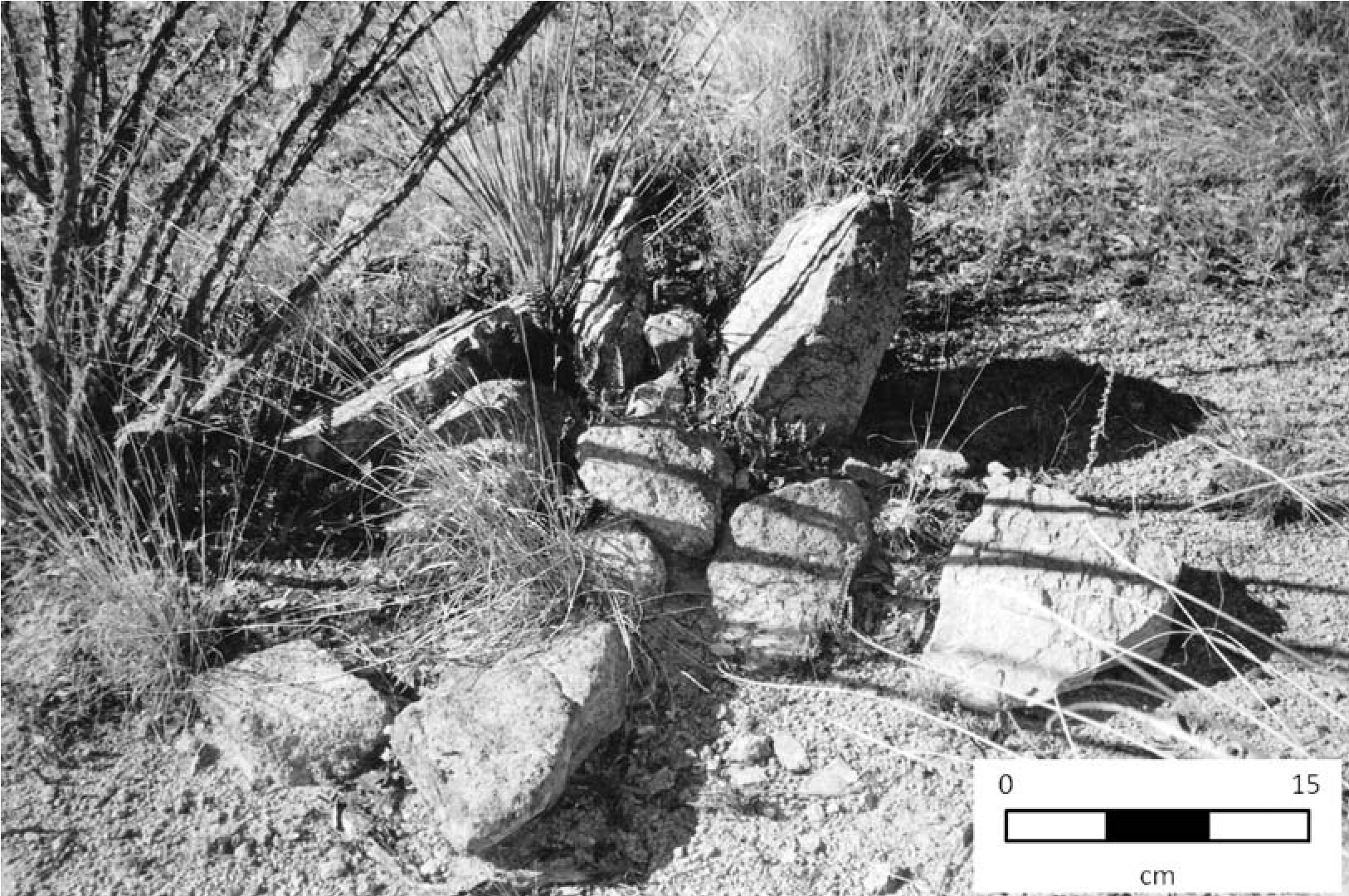

4.7. Rock ring structural features 50

4.8. Mobile group clearing 51

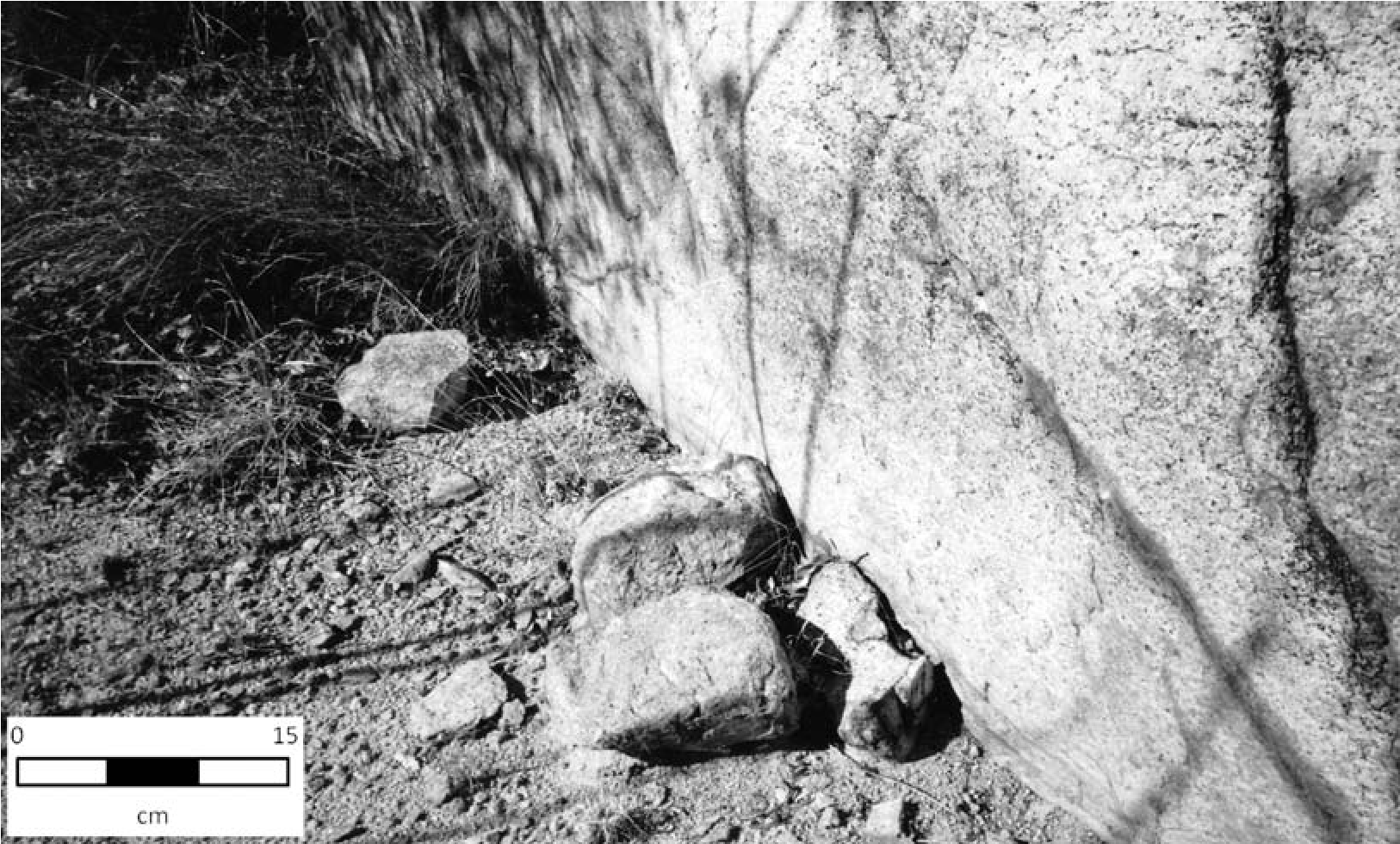

4.9. Structural features against rock face 52

4.10. Structural clearings on rocky slopes 53

4.11. Variable rock sizes forming structure outlines 54

4.12. Tipi rings 55

4.13. Modern modifications to mobile group sites 56

4.14. Agricultural terraces 57

4.15. Puebloan shrines on raised topographic features 60

4.16. Puebloan shrines near Abó 62

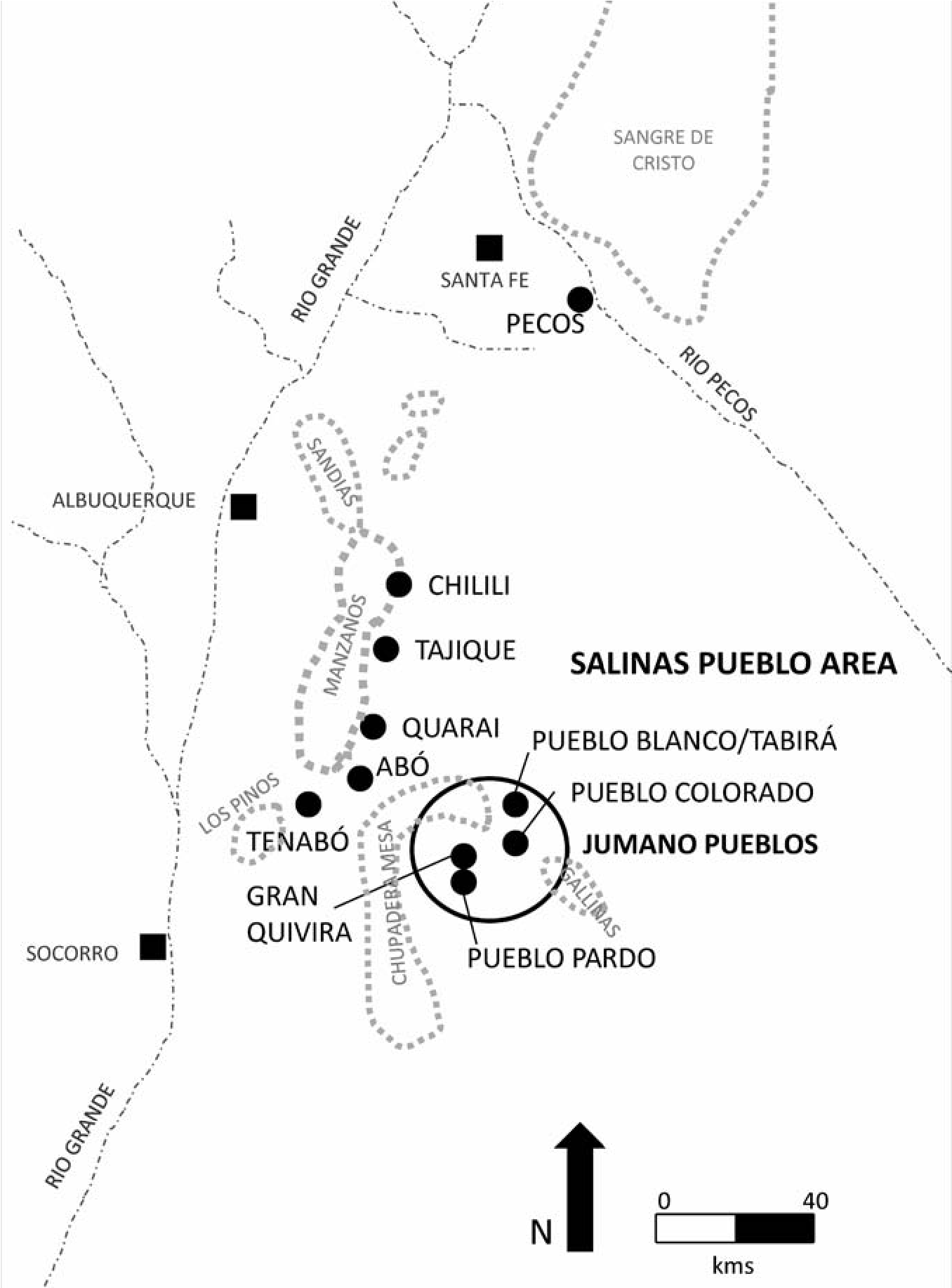

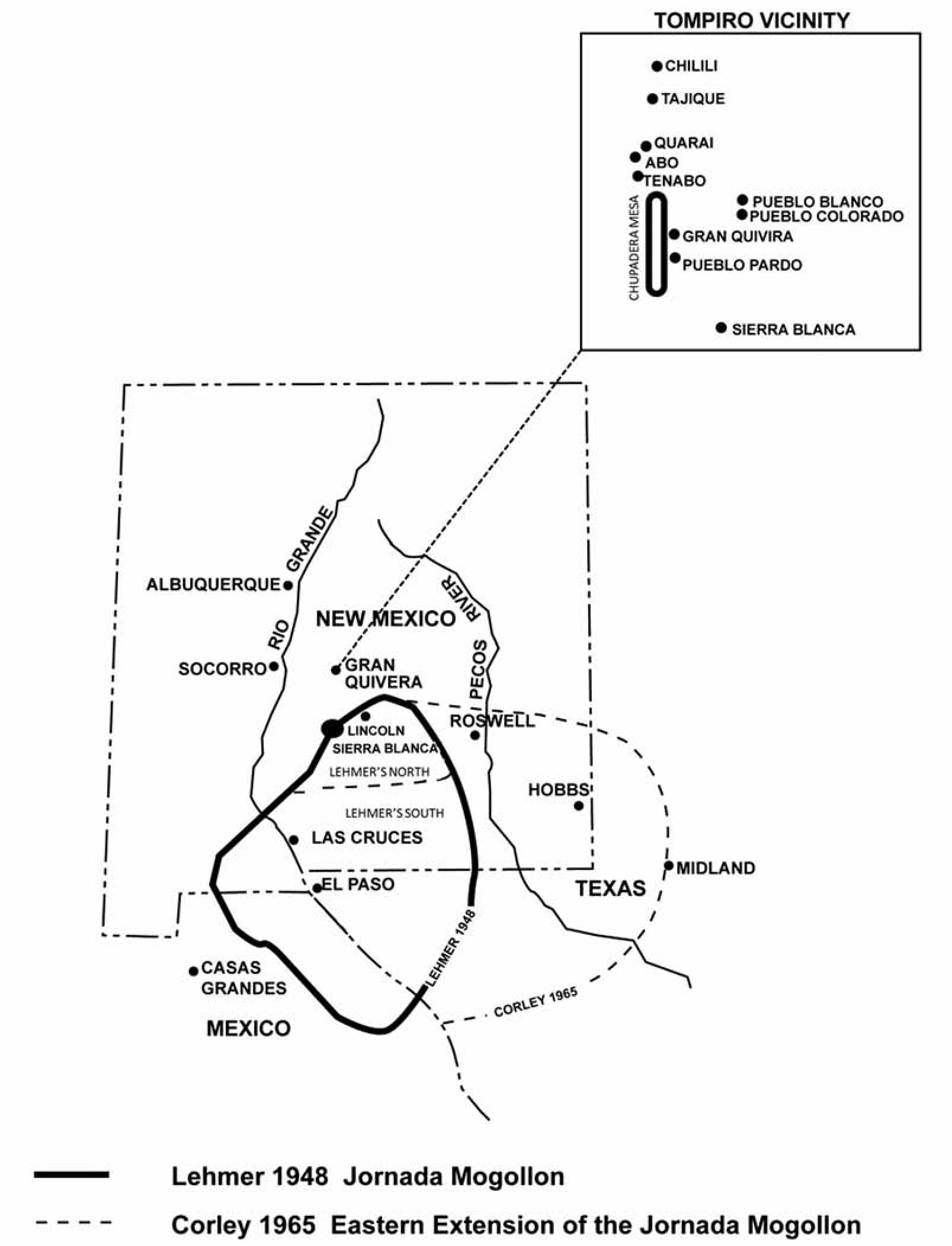

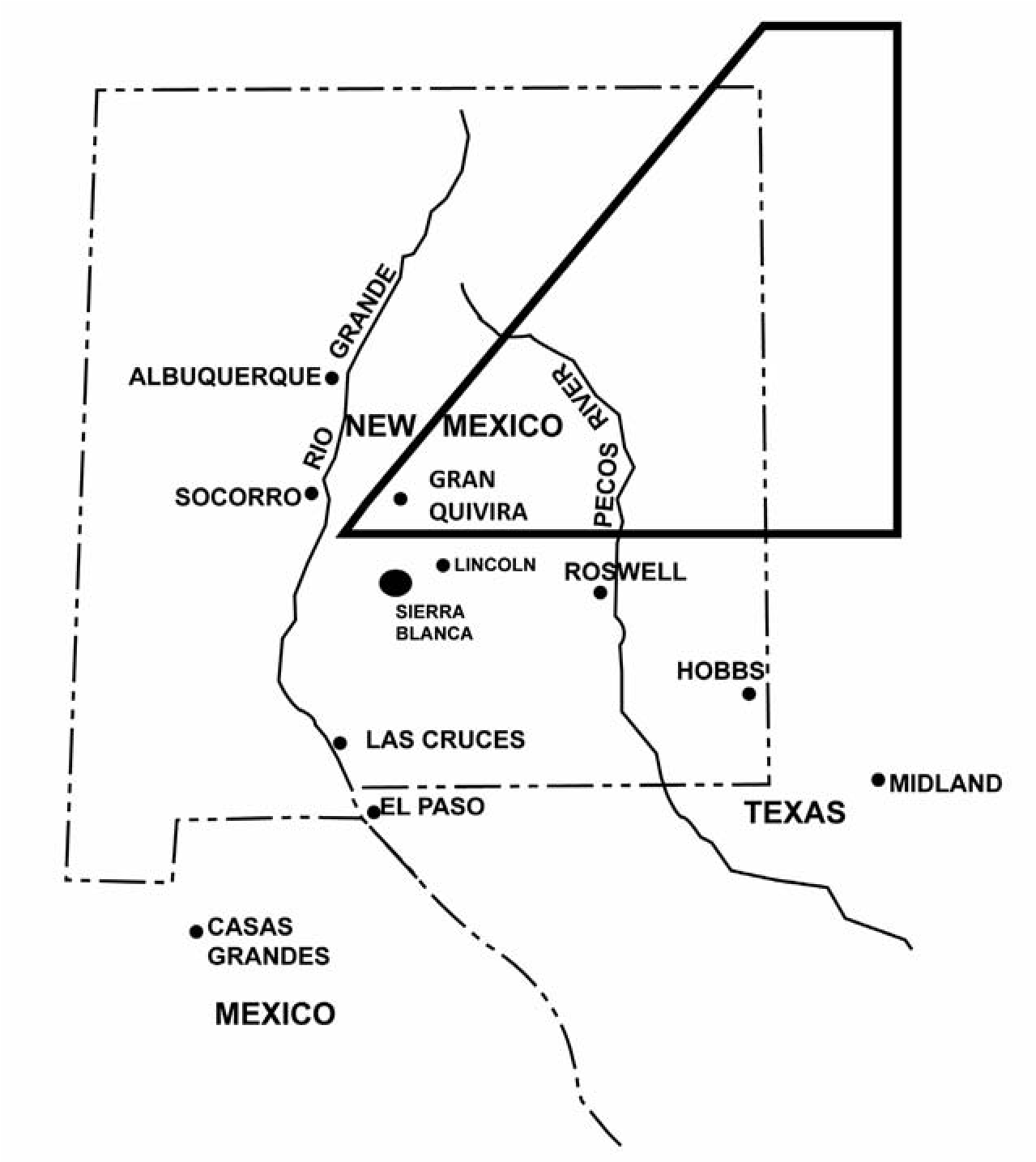

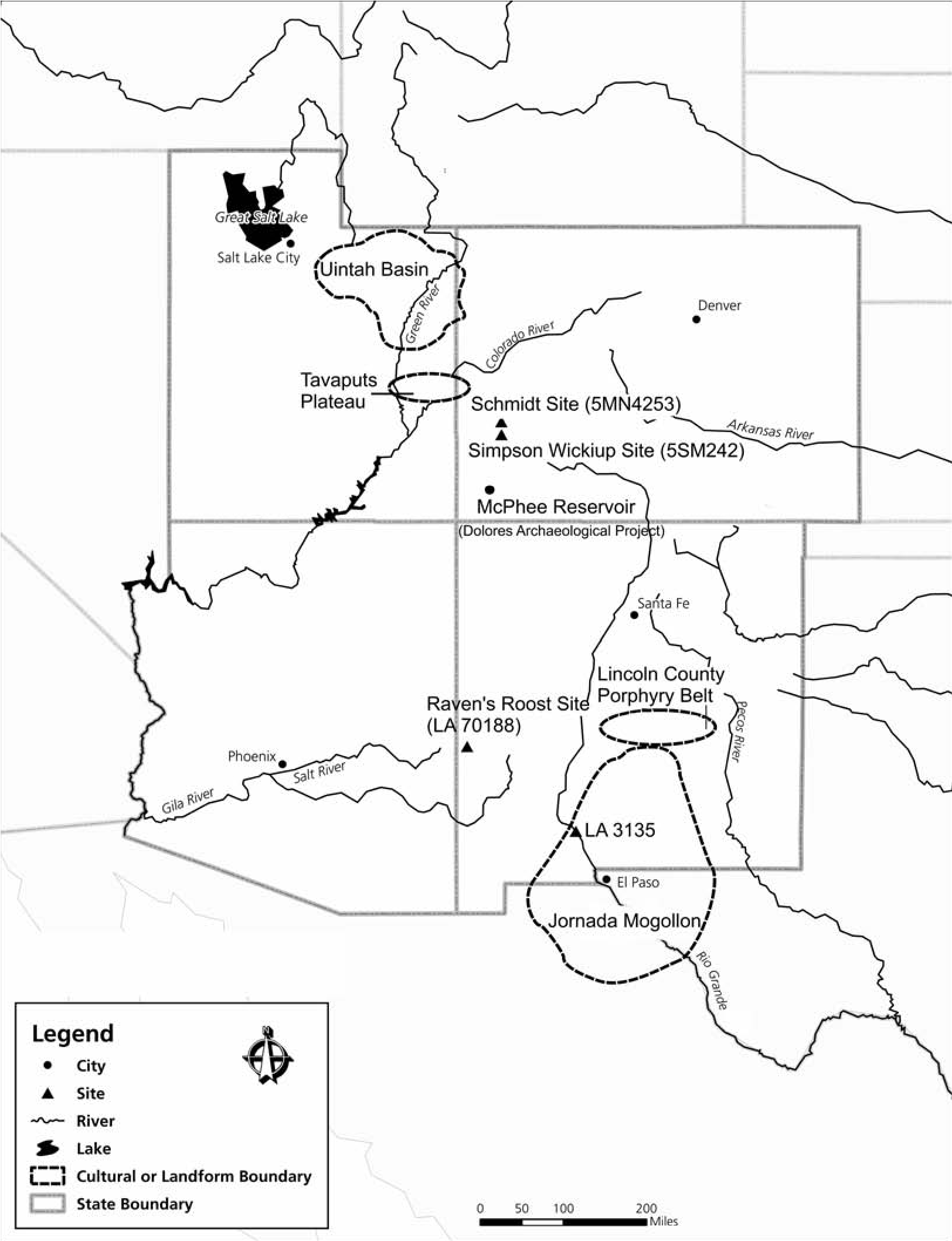

5.1. Culture areas in the Jornada Mogollon area 65

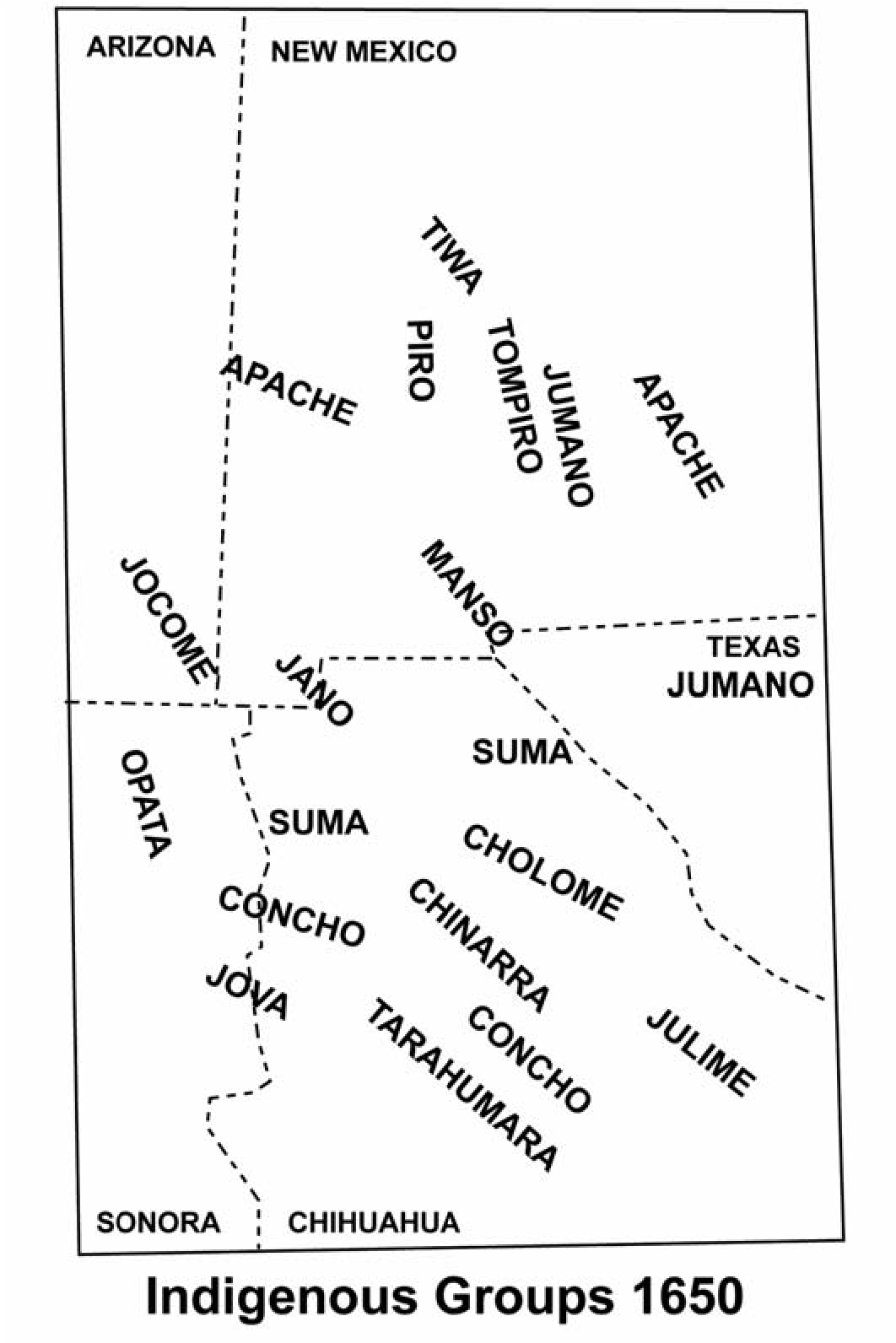

5.2. Distribution of culture groups around 1650 66

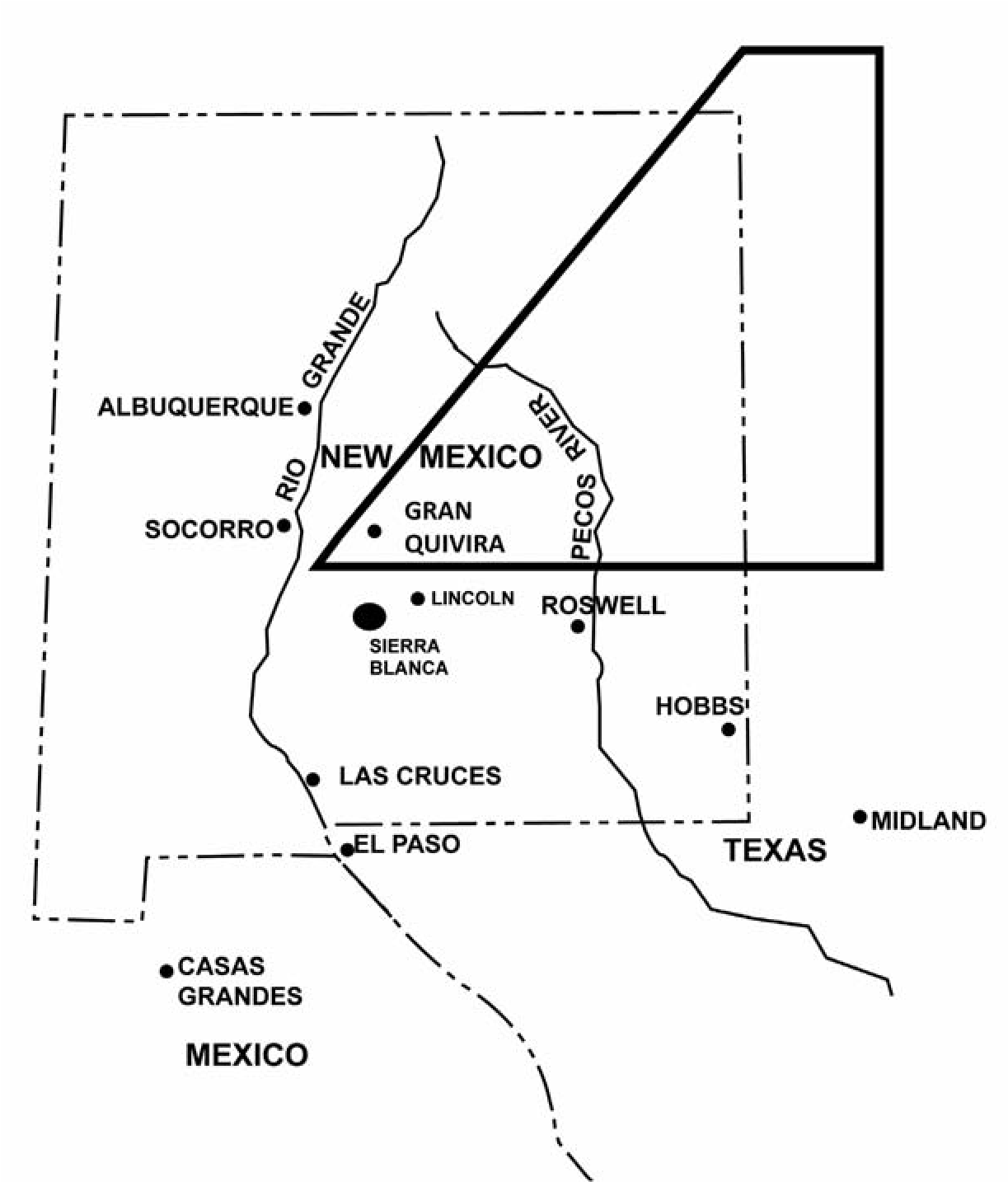

5.3. Chupadero Black-on-white production and distribution from Gran Quivira, ad 1150–1200 71

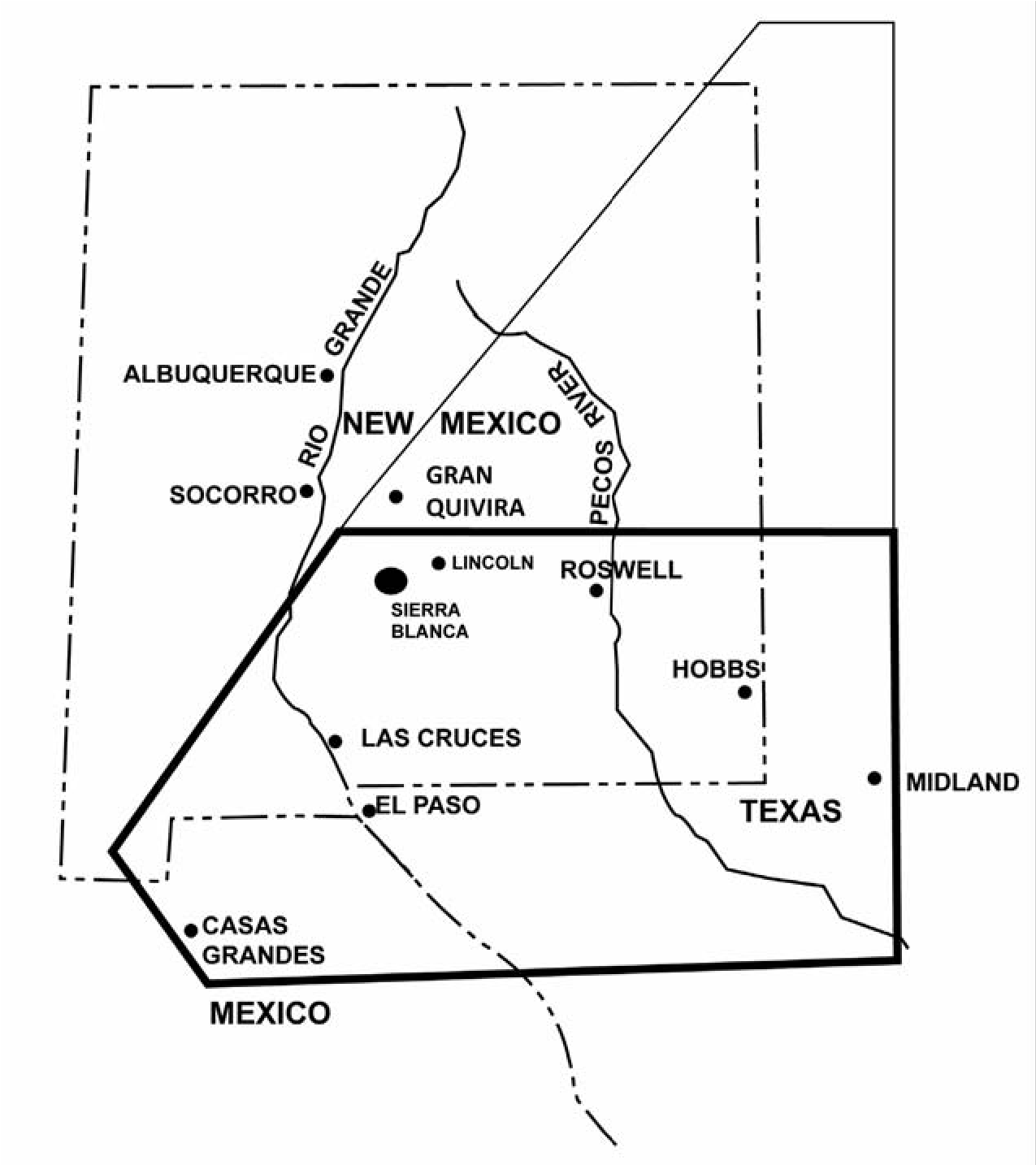

5.4. Chupadero Black-on-white production and distribution from Sierra Blanca, AD 1200–1400 72

5.5. Continued (unchanged) Chupadero Black-on-white production and distribution from Gran Quivira,AD 1200–1550 73

5.6. Possible Chupadero Black-on-white production from Jumano/Suma, AD 1400–1700 74

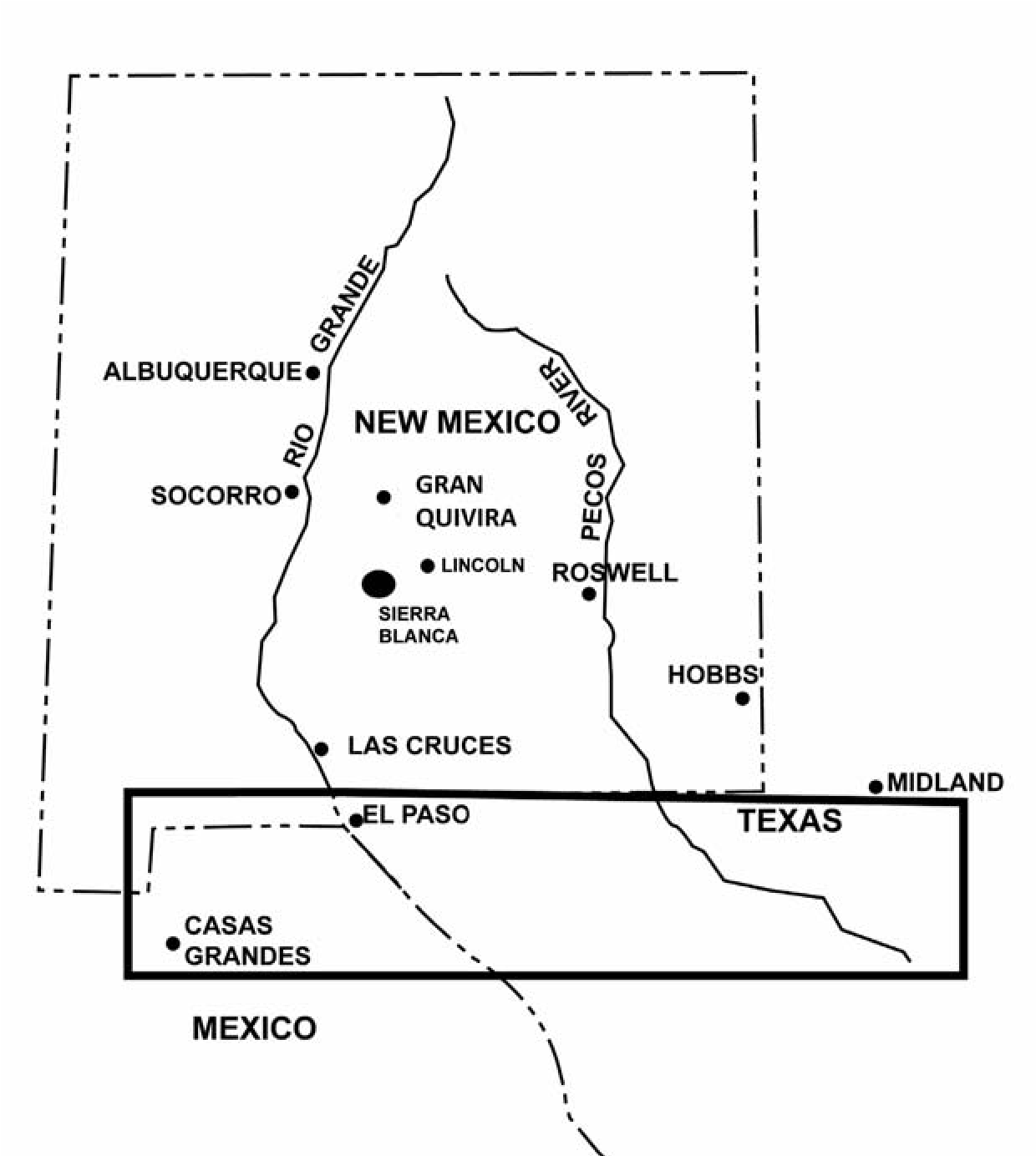

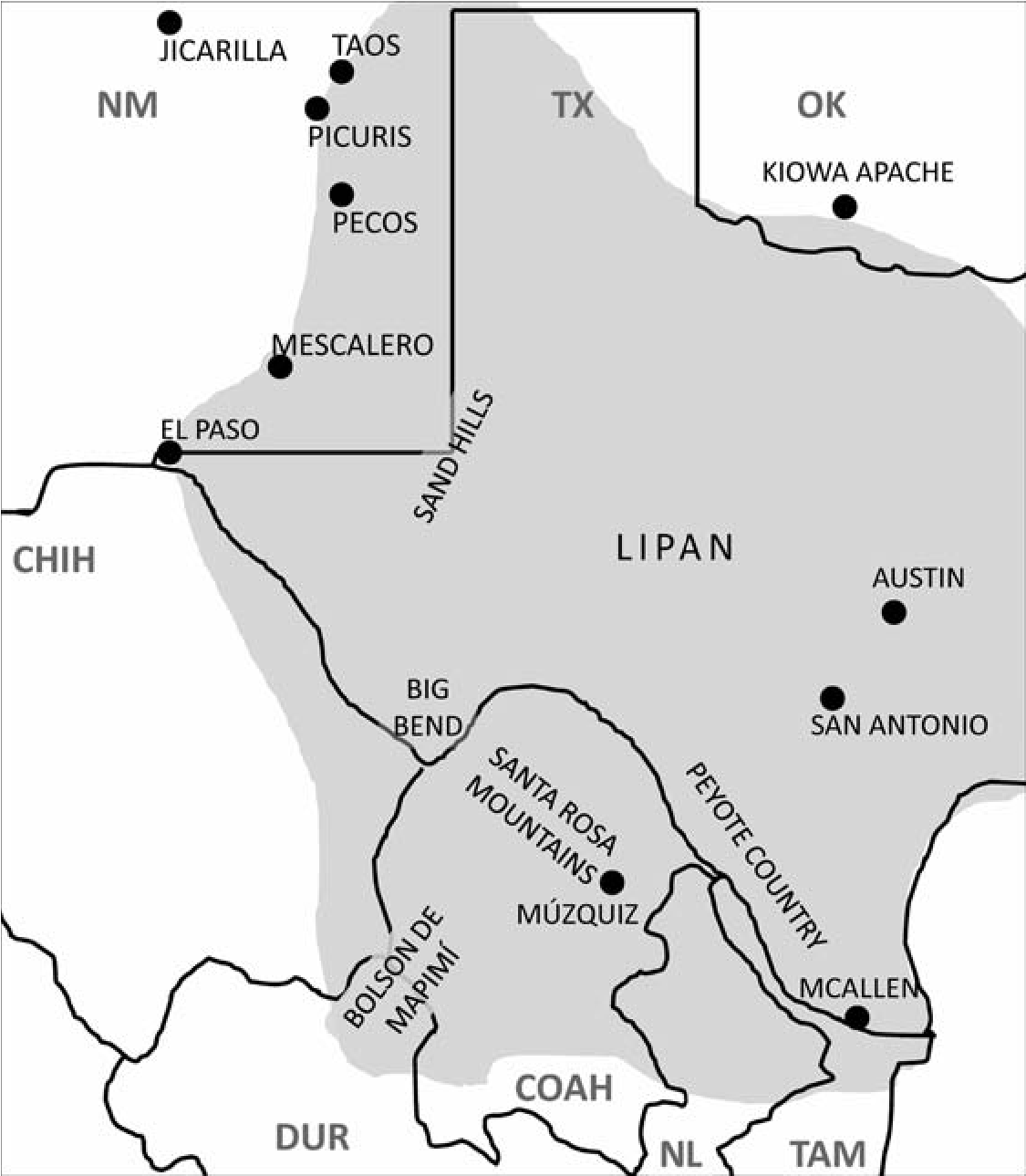

6.1. Key locations in Lipan Apache territory 78

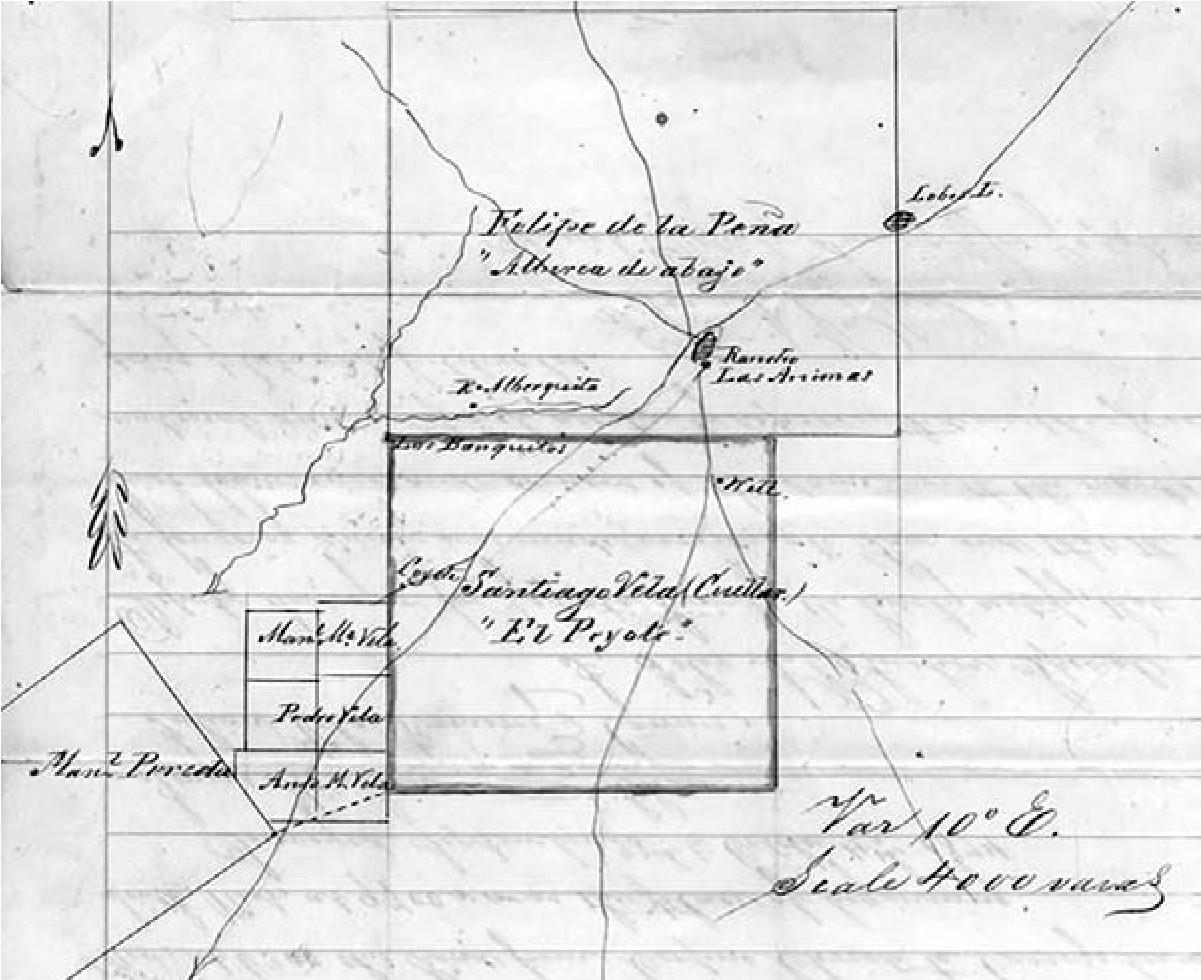

6.2. Plan of Lipan Apache El Peyote Land Grant 87

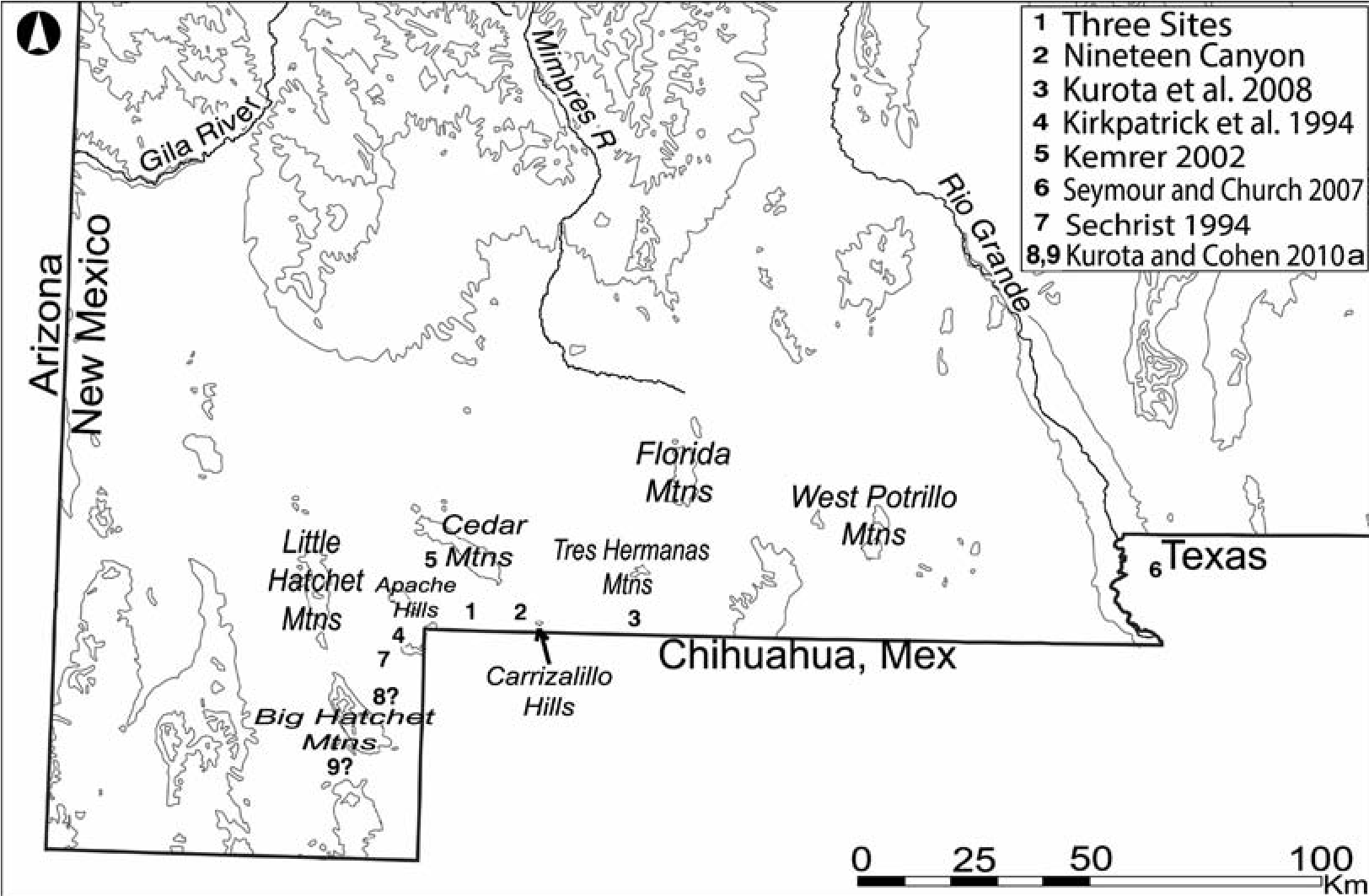

7.1. Southwestern New Mexico Protohistoric period sites 90

7.2. Map of LA 125753 at Nineteen Canyon 92

7.3. Features excavated at Nineteen Canyon 93

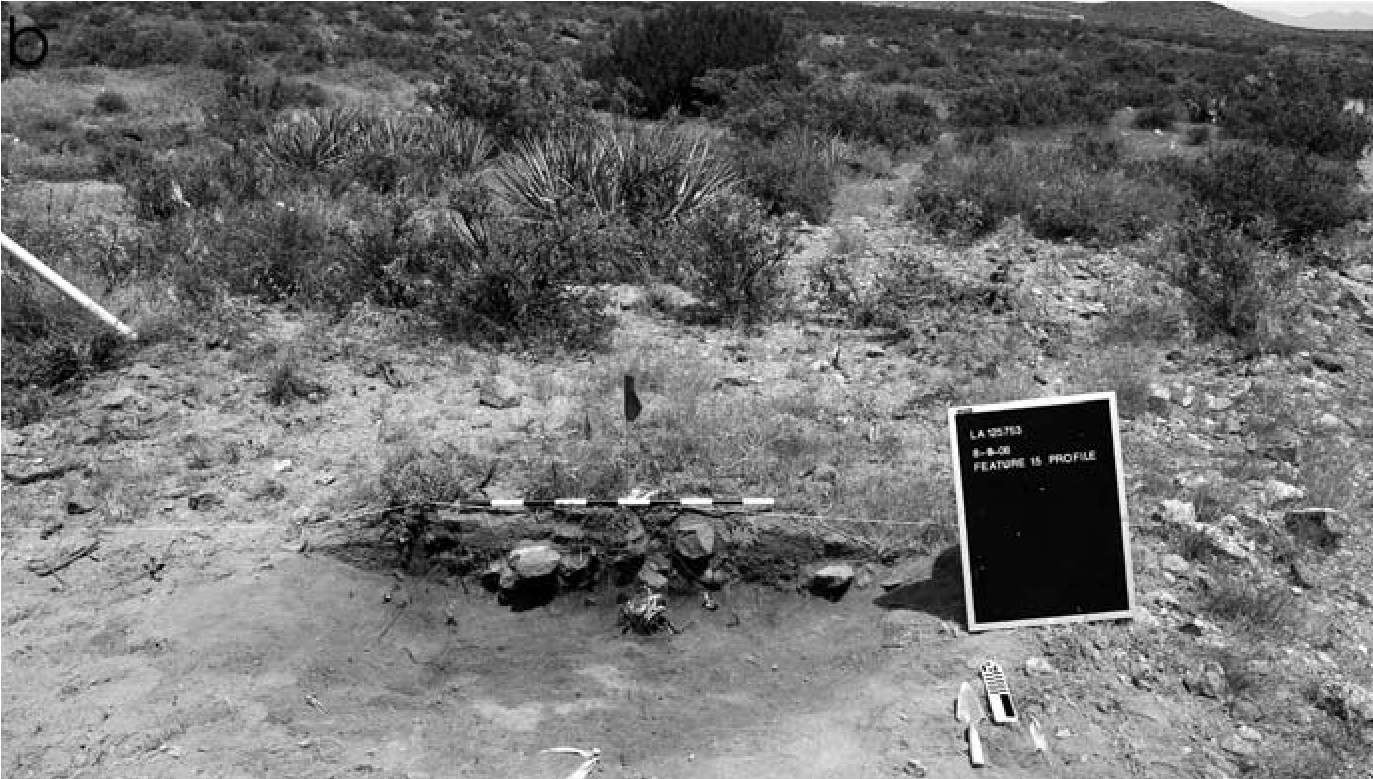

7.4. Overview of large ring midden 94

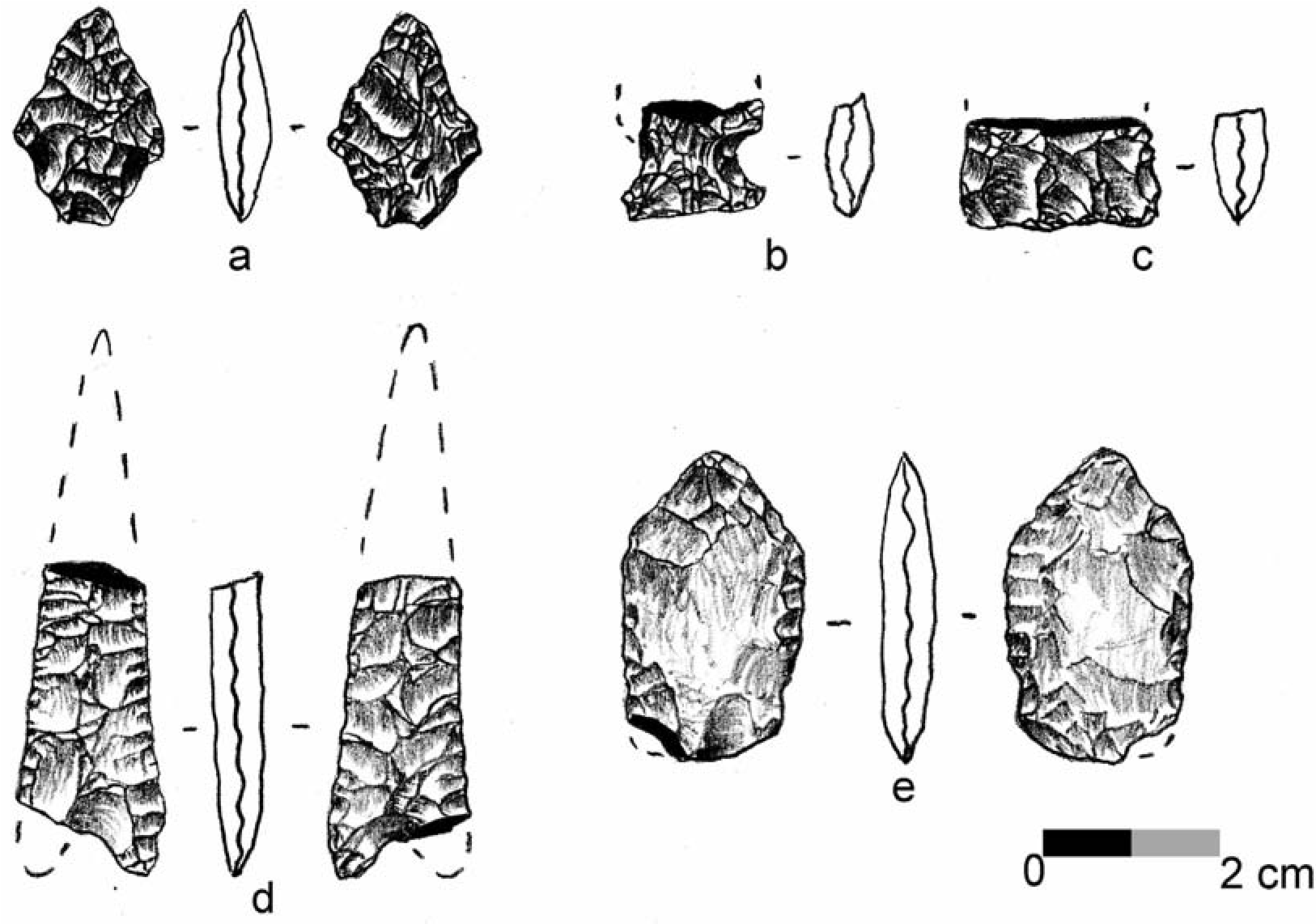

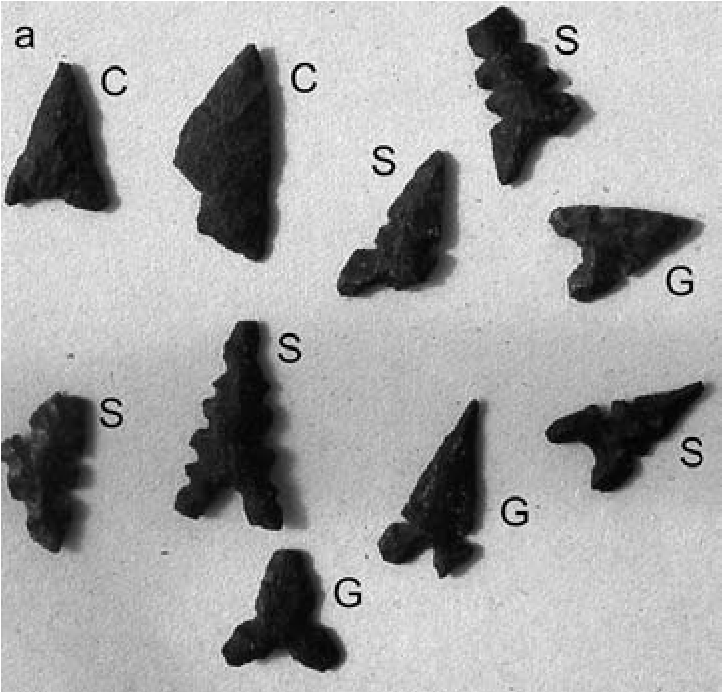

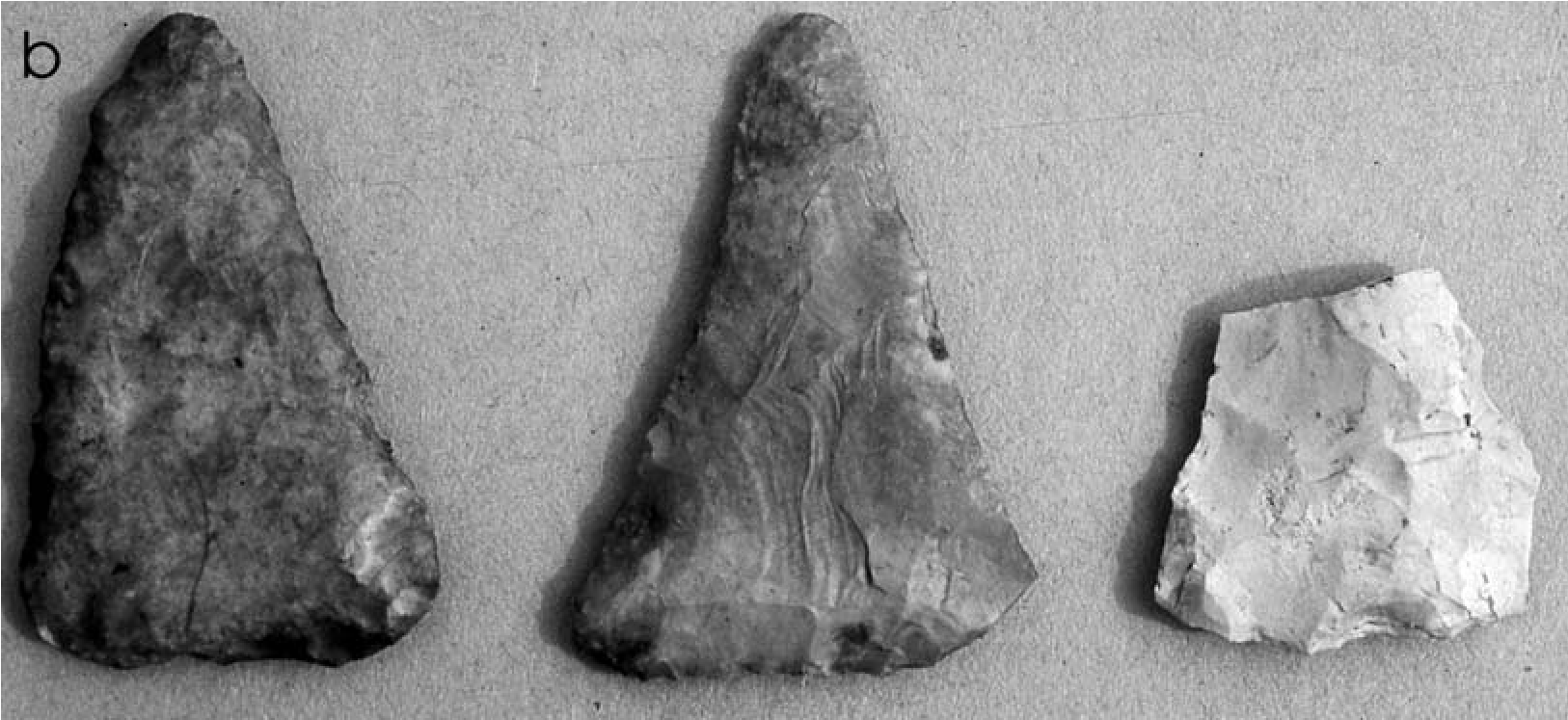

7.5. Projectile points recovered at LA 125753 95

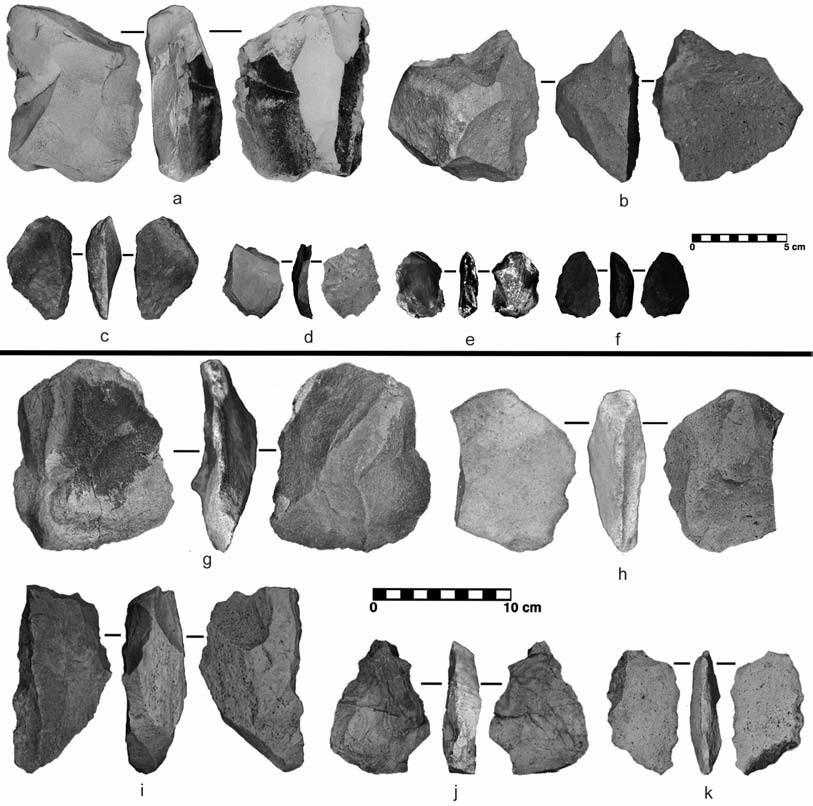

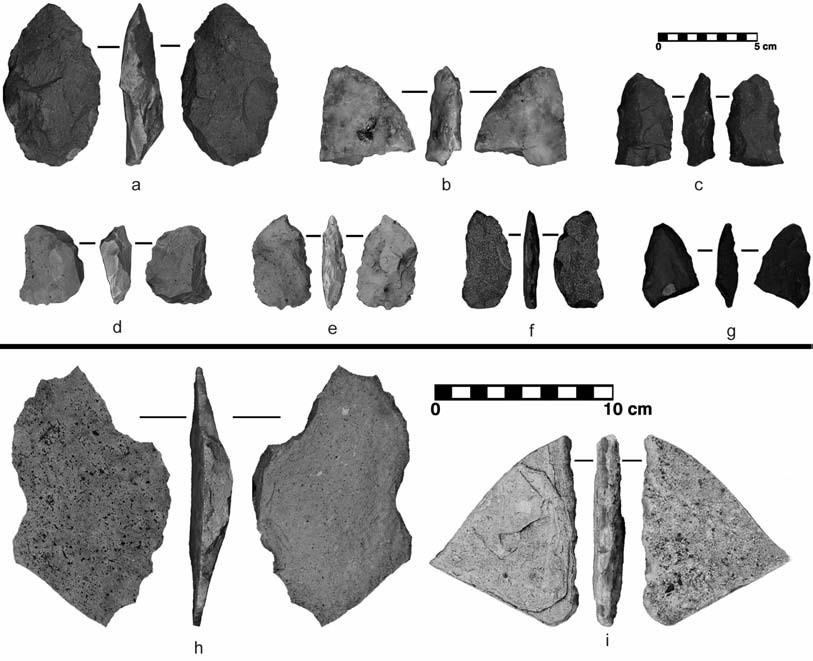

7.6. Scraping tools and choppers recovered at LA 125753 96

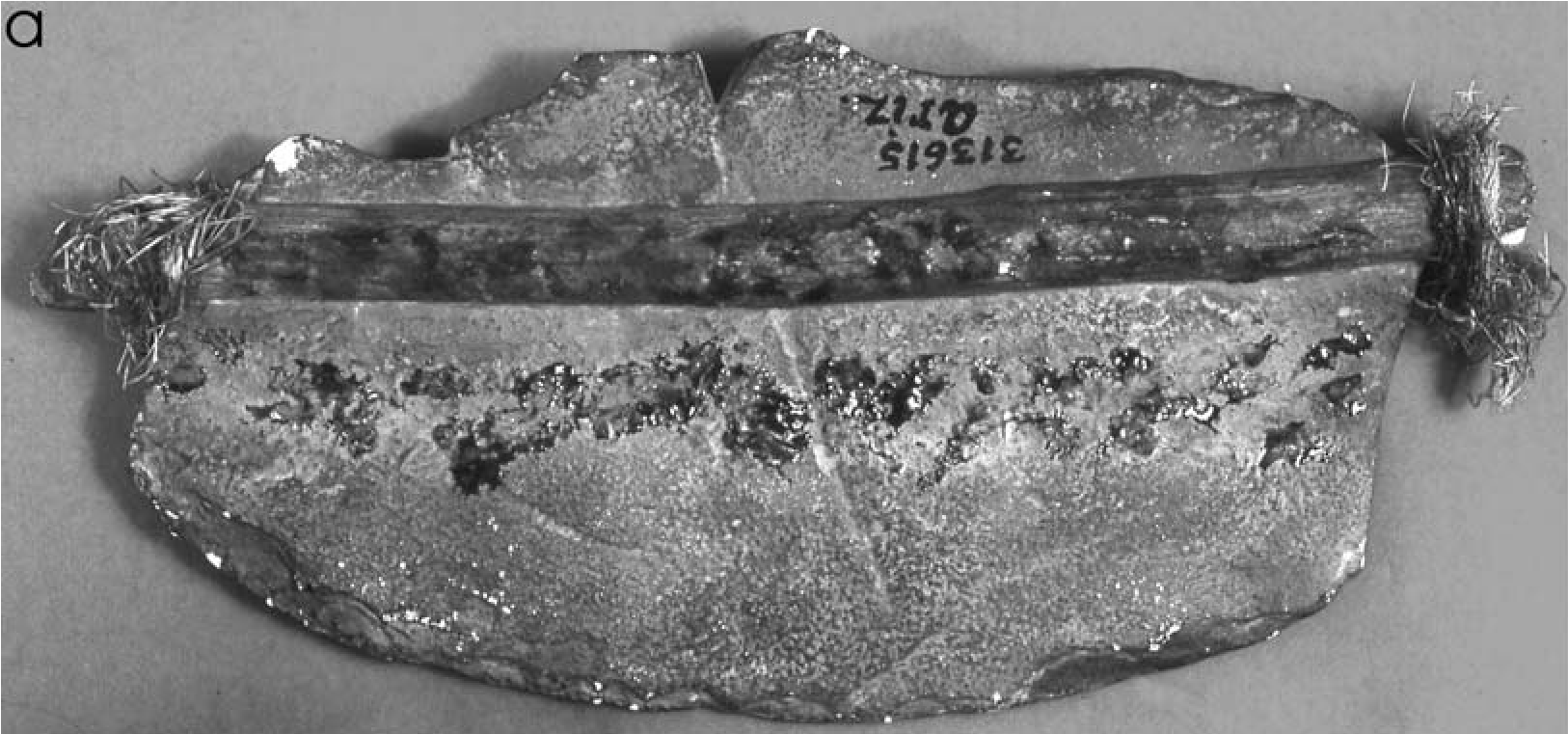

7.7. Bifacial tools and tabular knives

recovered at LA 125753 97

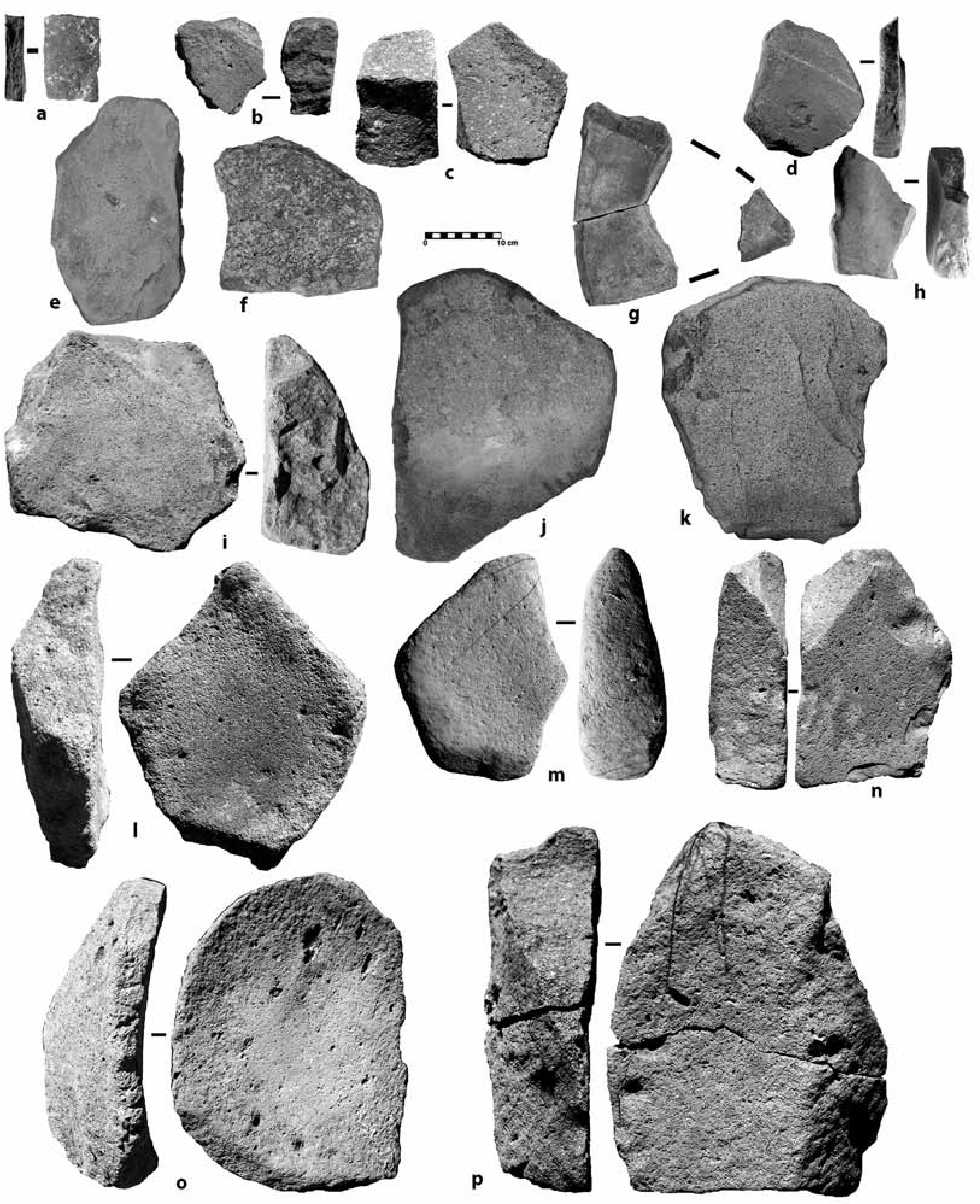

7.8. Metates recovered at LA 125753 98

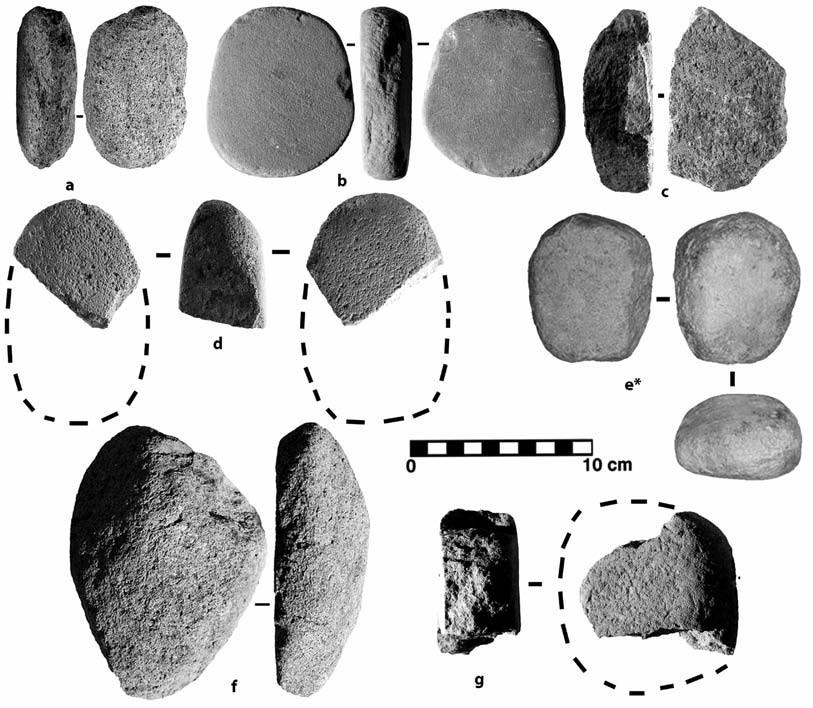

7.9. Manos recovered at LA 125753 99

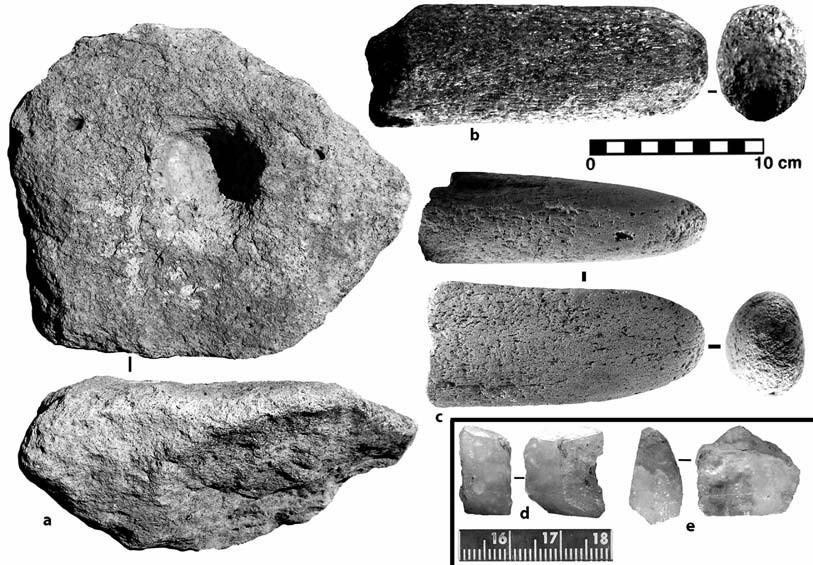

7.10. Mortar, pestles, and quartz crystals

recovered at LA 125753 100

7.11. Small-rock pit thermal features at Three Sites 101

7.12. Projectile points and scrapers recovered at Three Sites 102

7.13. Histogram showing flake sizes 103

7.14. Clusters of thermal features identified at Three Sites 104

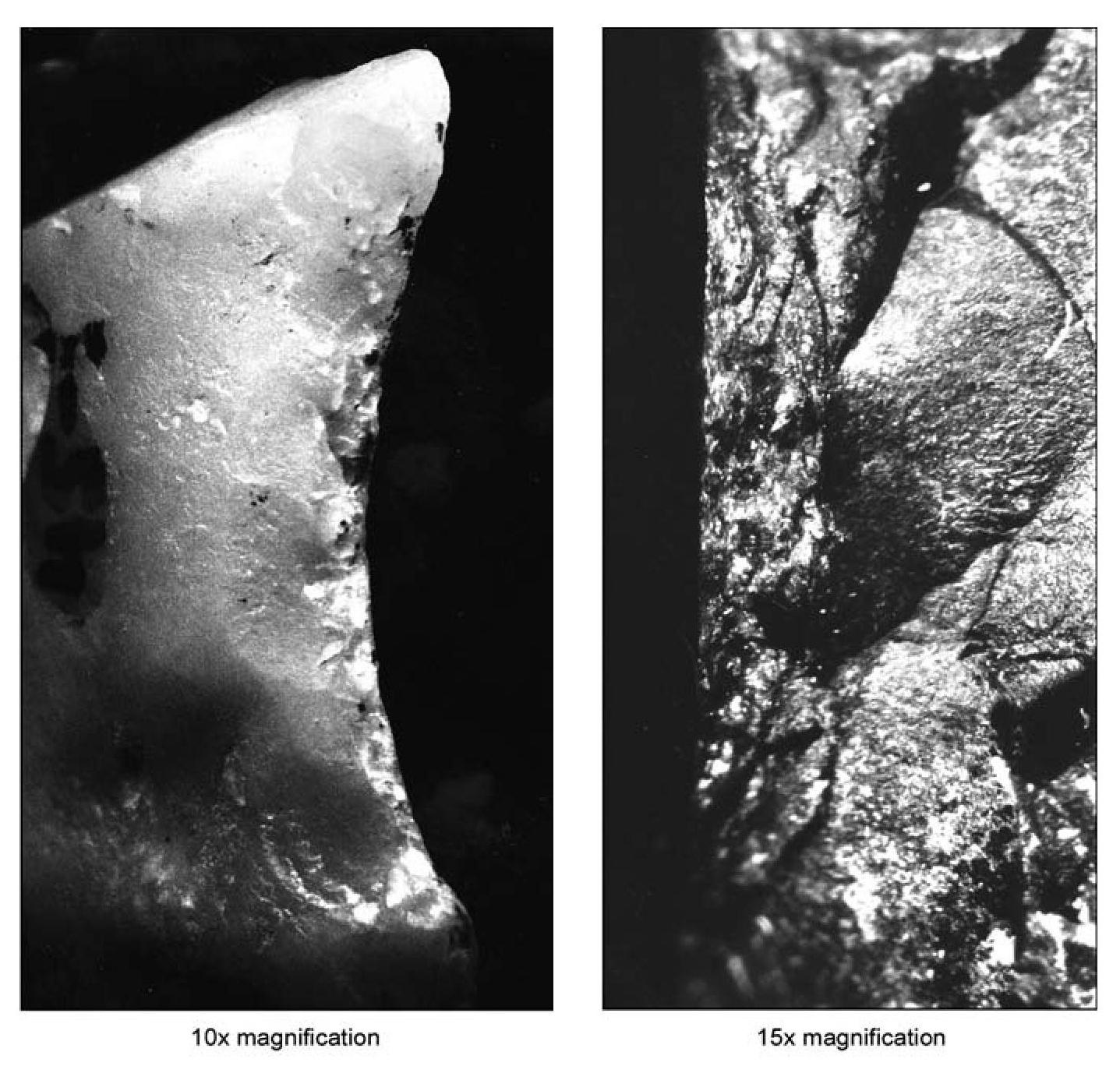

8.1. Edge wear on strike-a-light flints 110

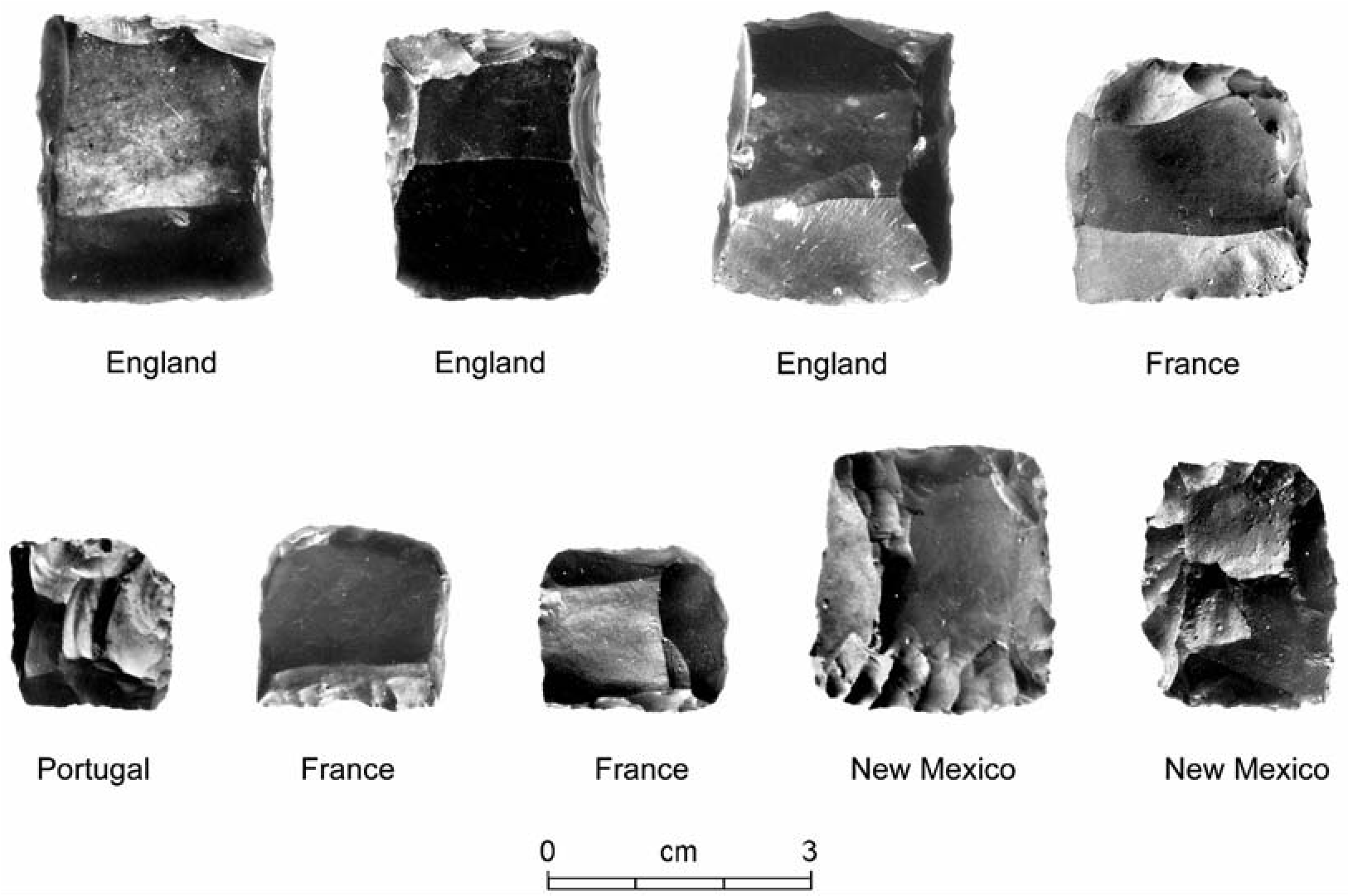

8.2. Various types of gunflints 112

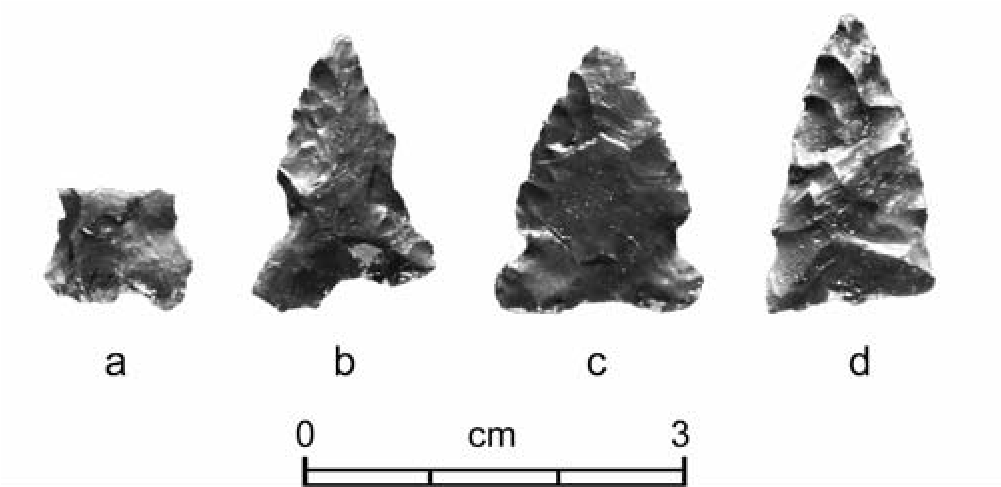

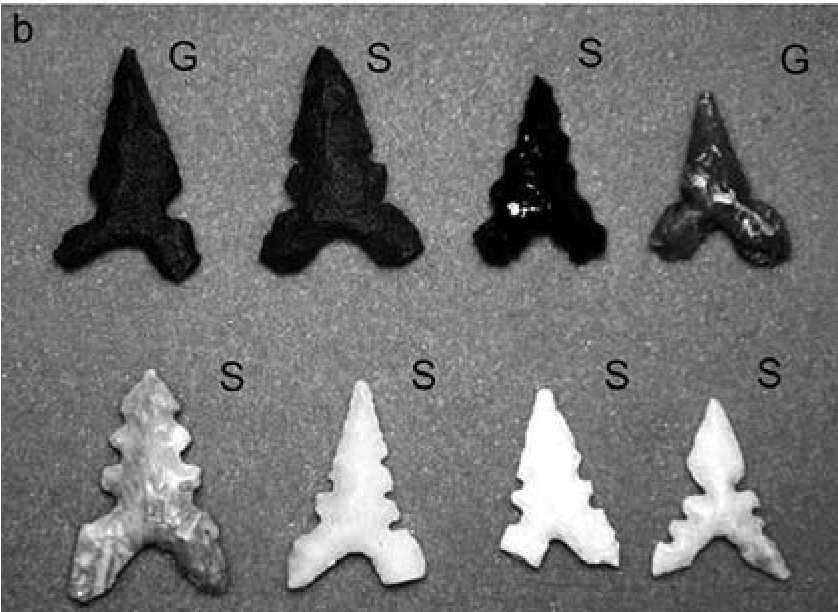

8.3. Spanish-made projectile points from northern New Mexico 113

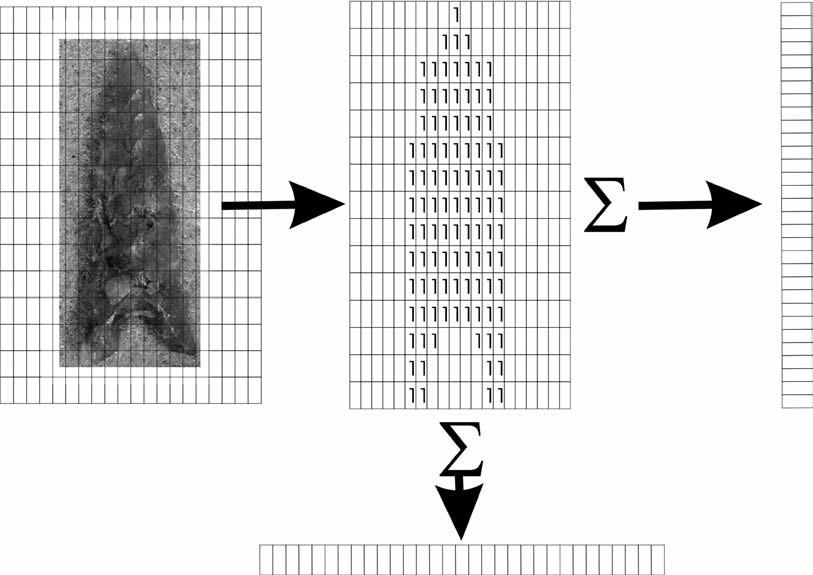

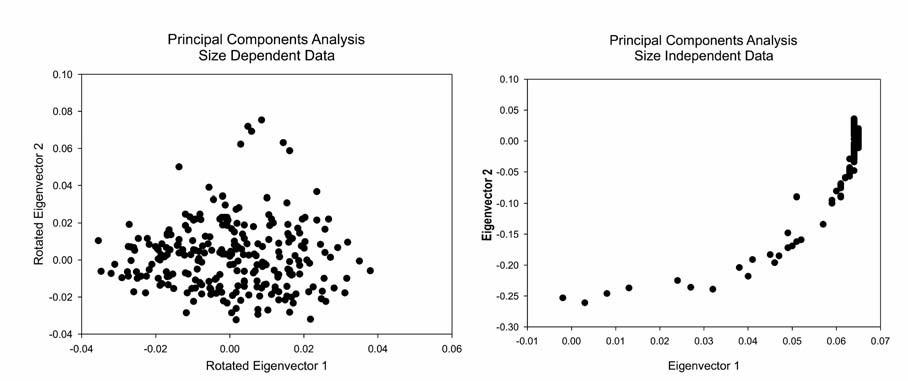

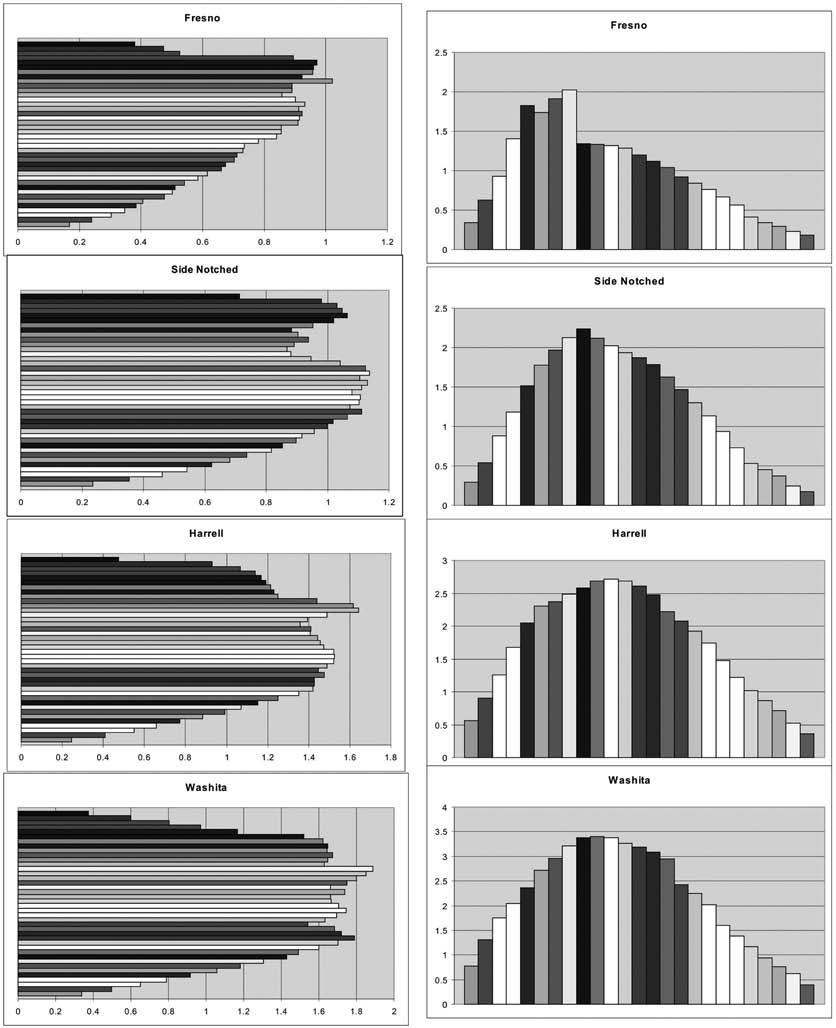

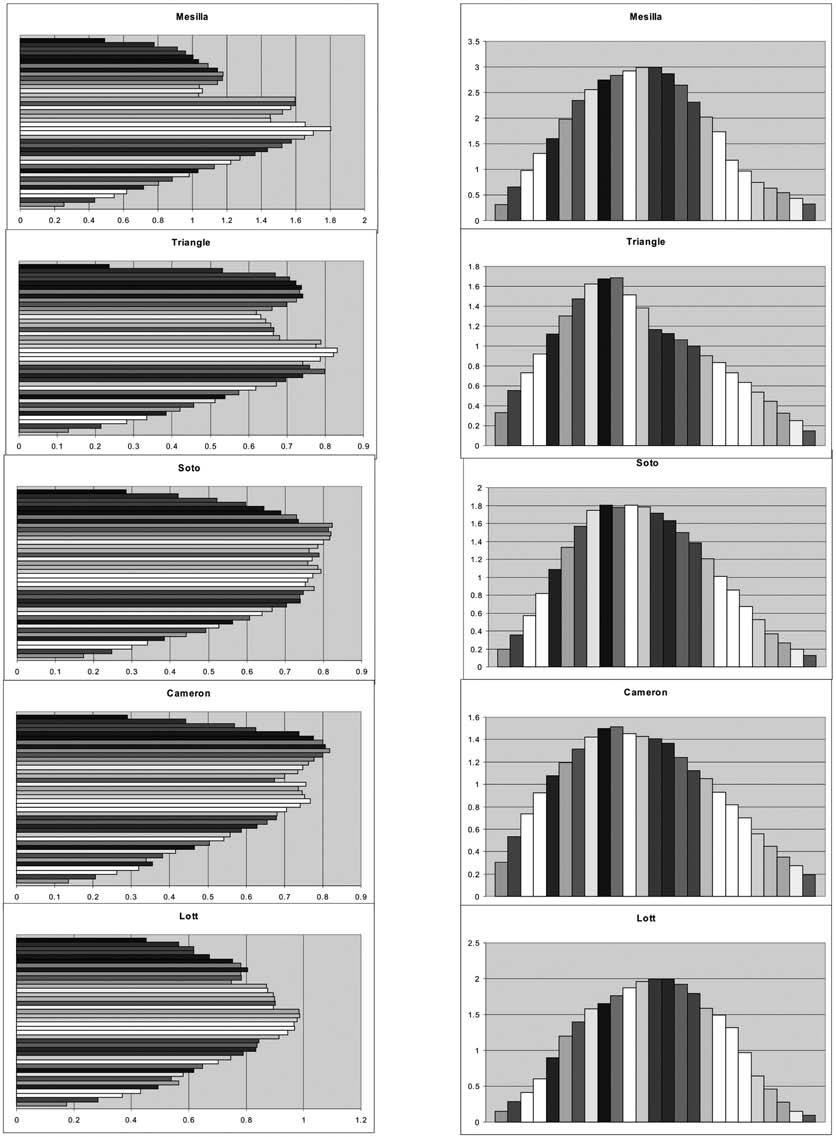

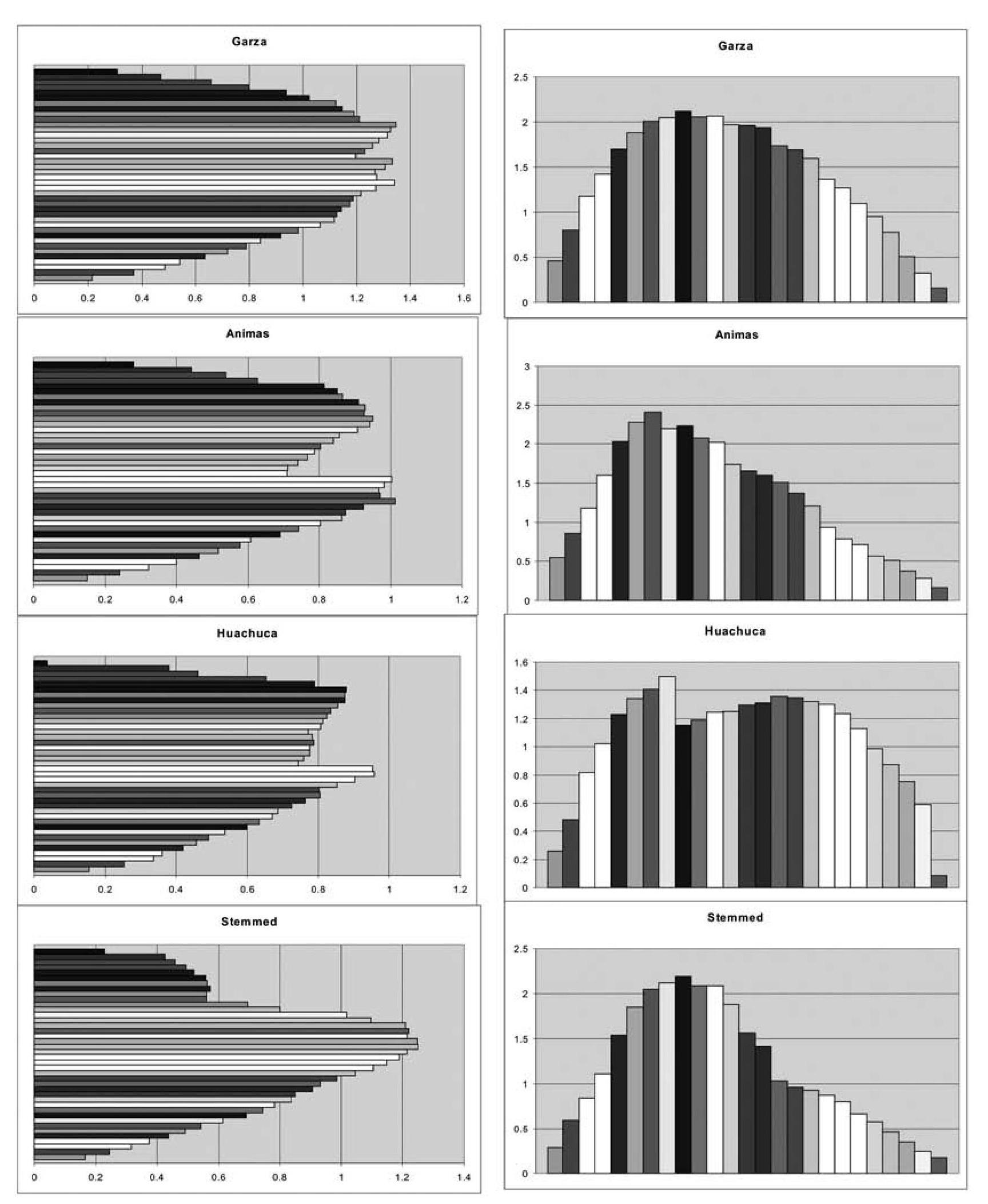

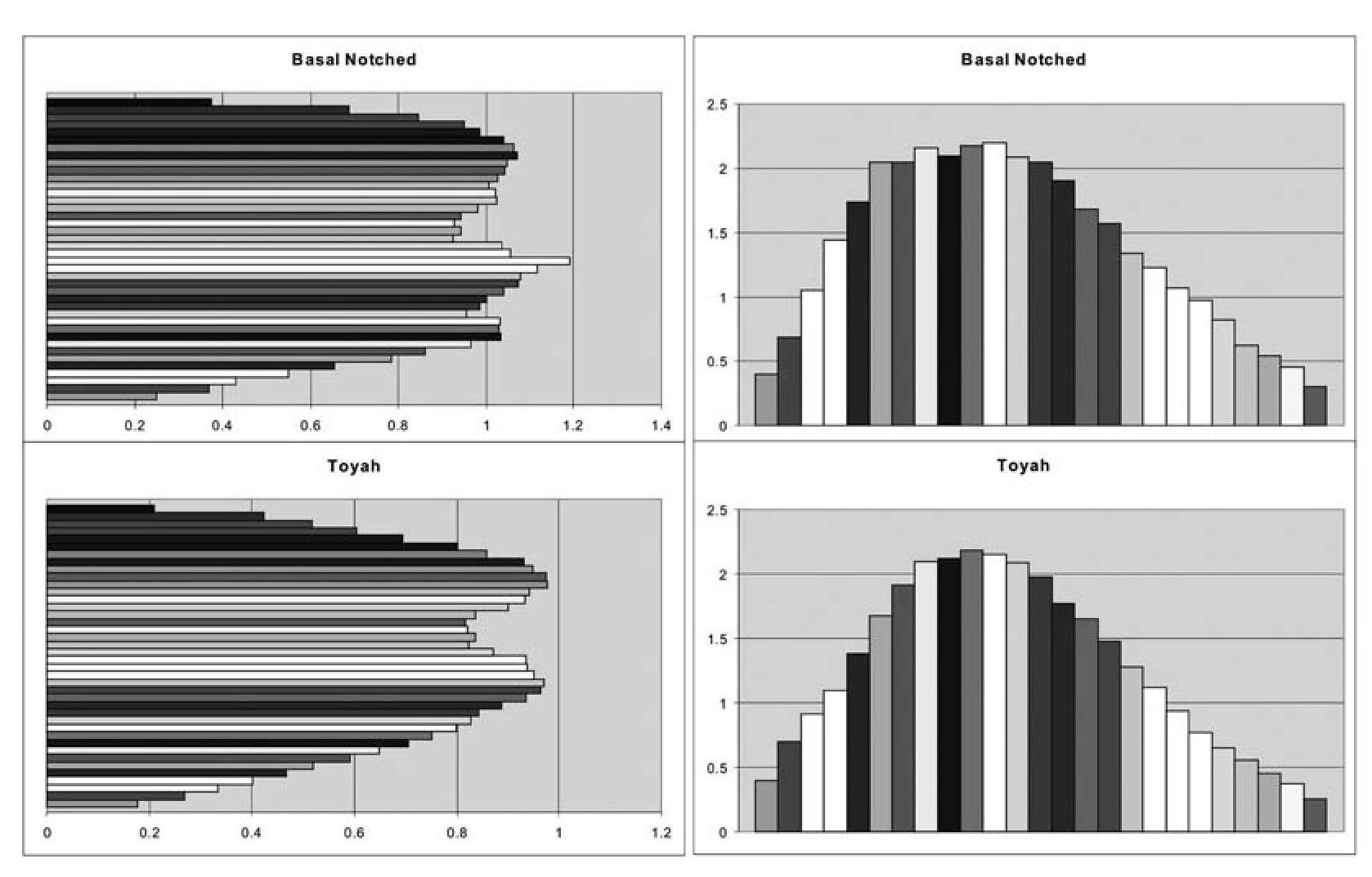

9.1. Reducing arrowhead shapes to metric form 119

9.2. Principal Components Analysis of arrowhead metric data 120

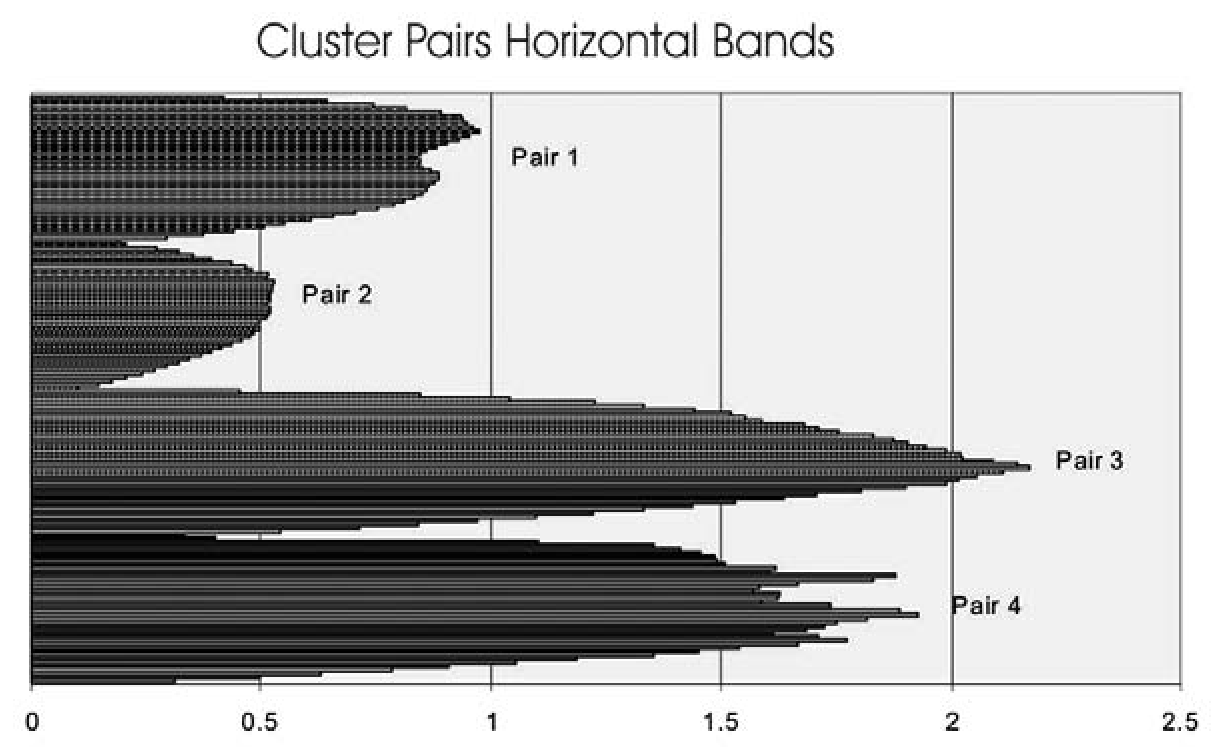

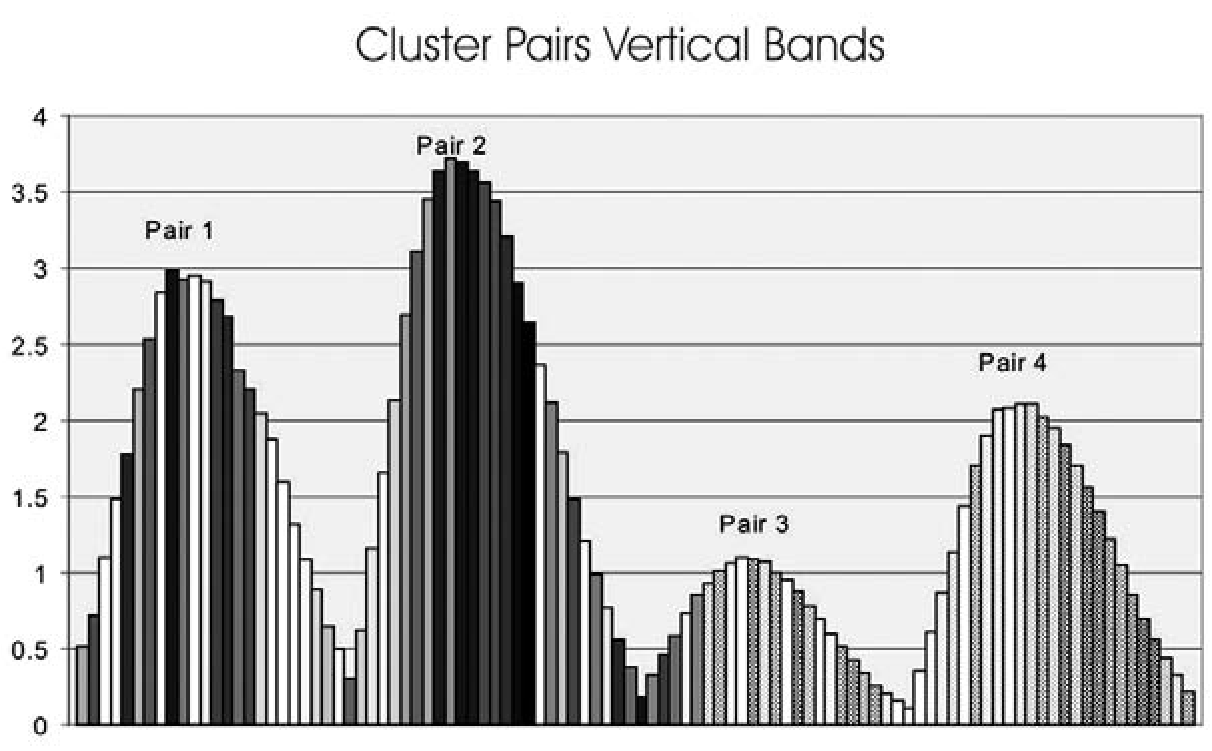

9.3. Metric bands used as inputs for the K-Means cluster analysis 130

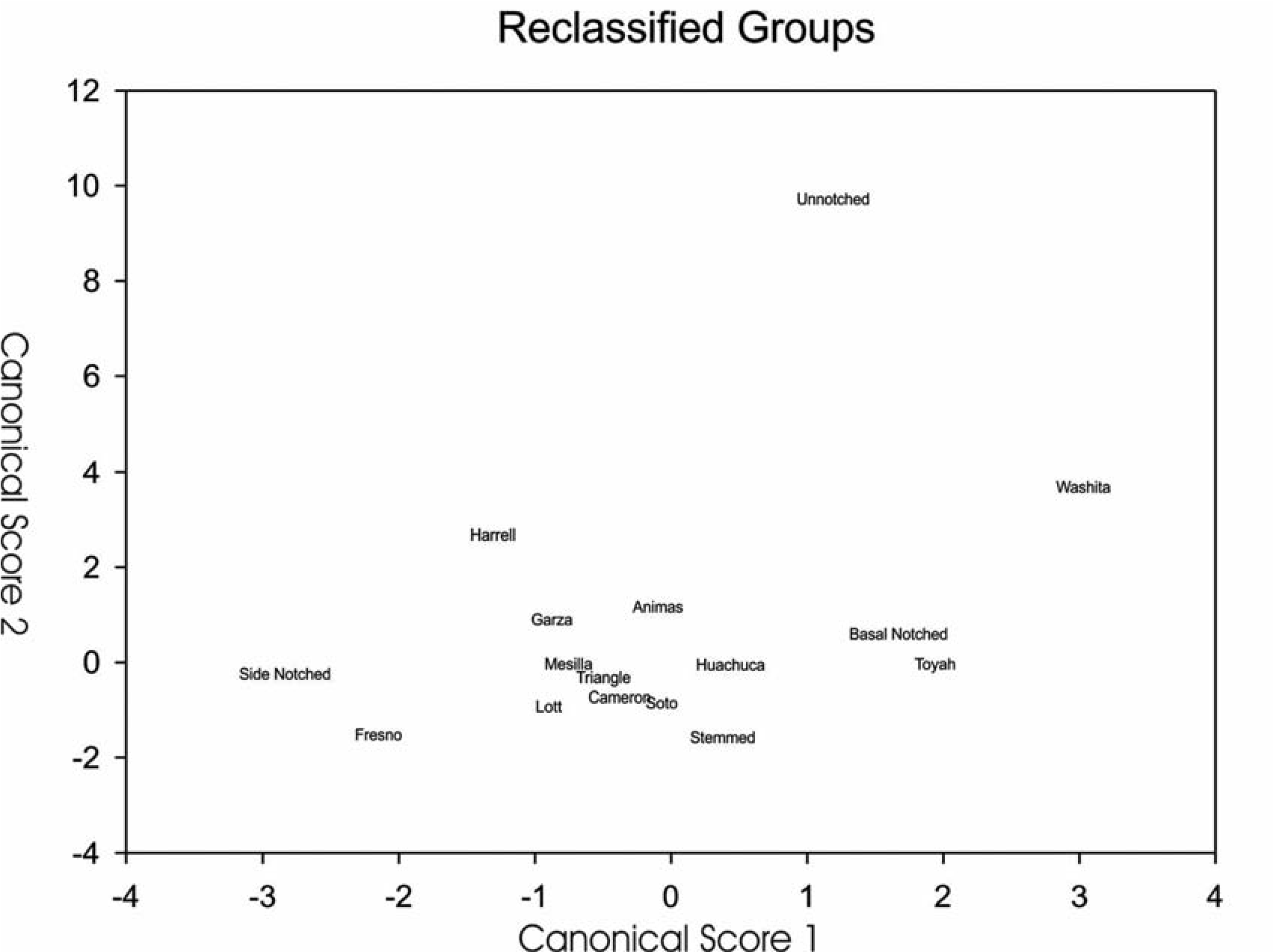

9.4. Relationships among the typological categories 131

9.5. Measurements for the arrowhead categories that are not members of a cluster 132

9.6. Measurements for the arrowhead categories that are members of a cluster 133

9.7. Measurements for the arrowhead categories that are weakly independent in the Discriminant Analysis 134

9.8. Measurements for the arrowhead categories that are paired in the Discriminant Analysis 135

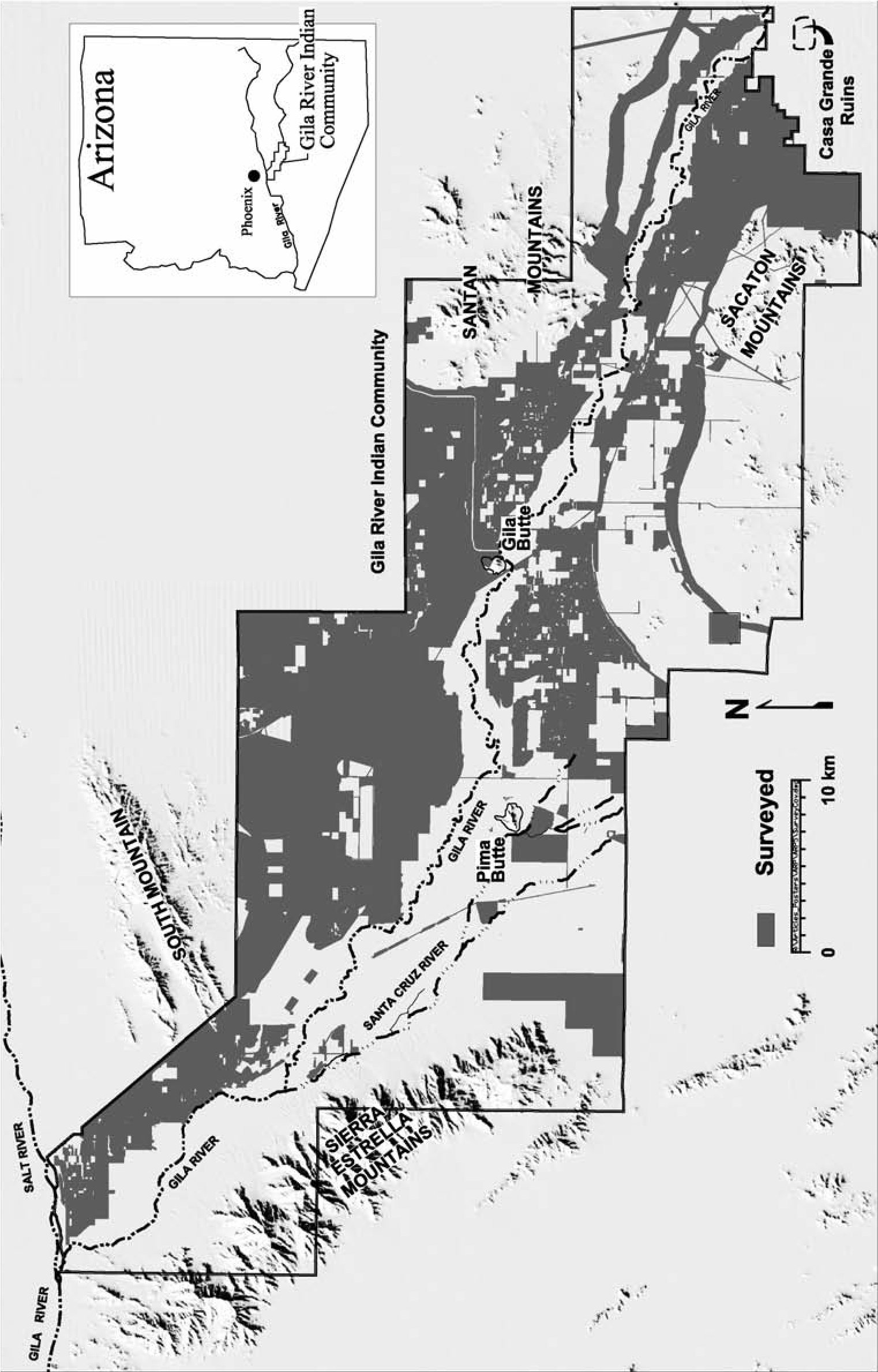

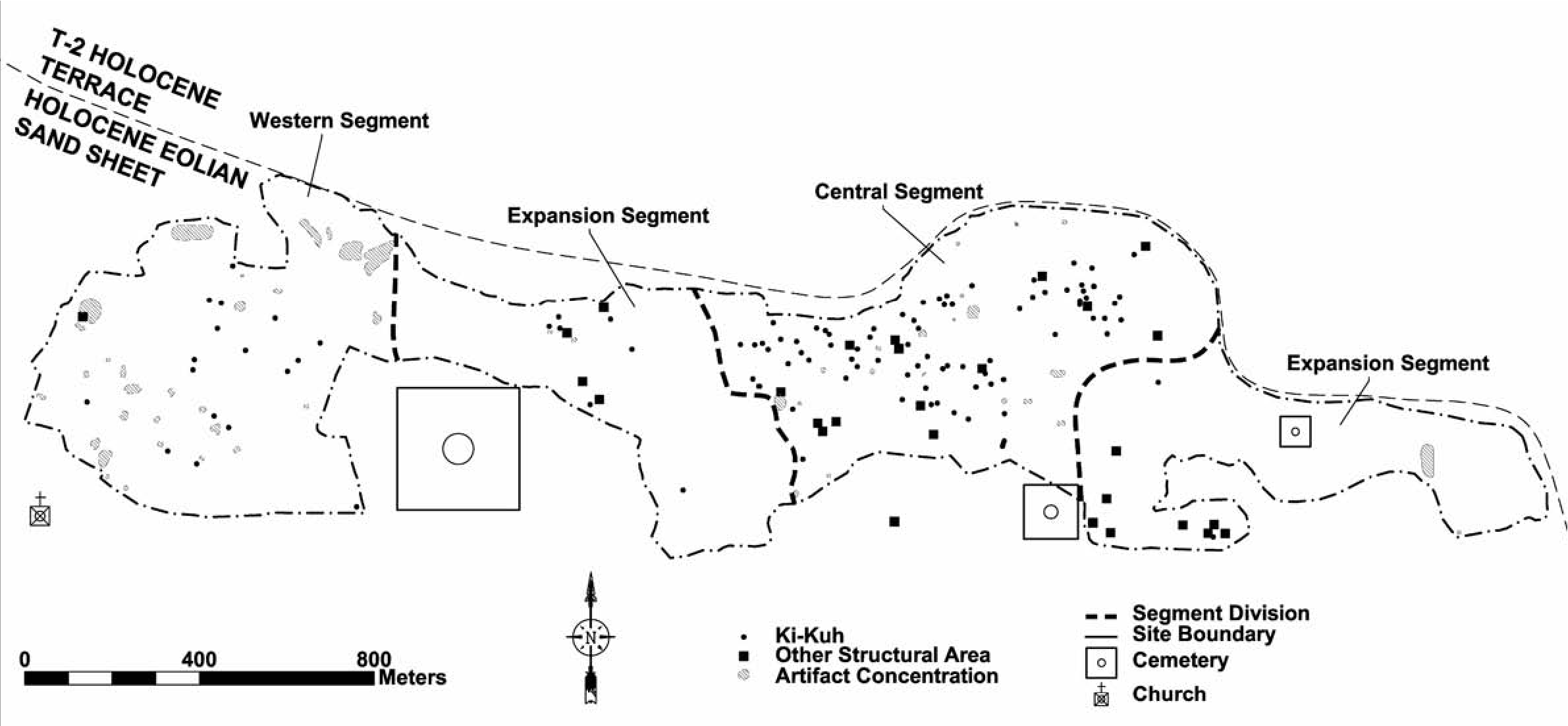

10.1. P-MIP survey coverage within the GRIC 139

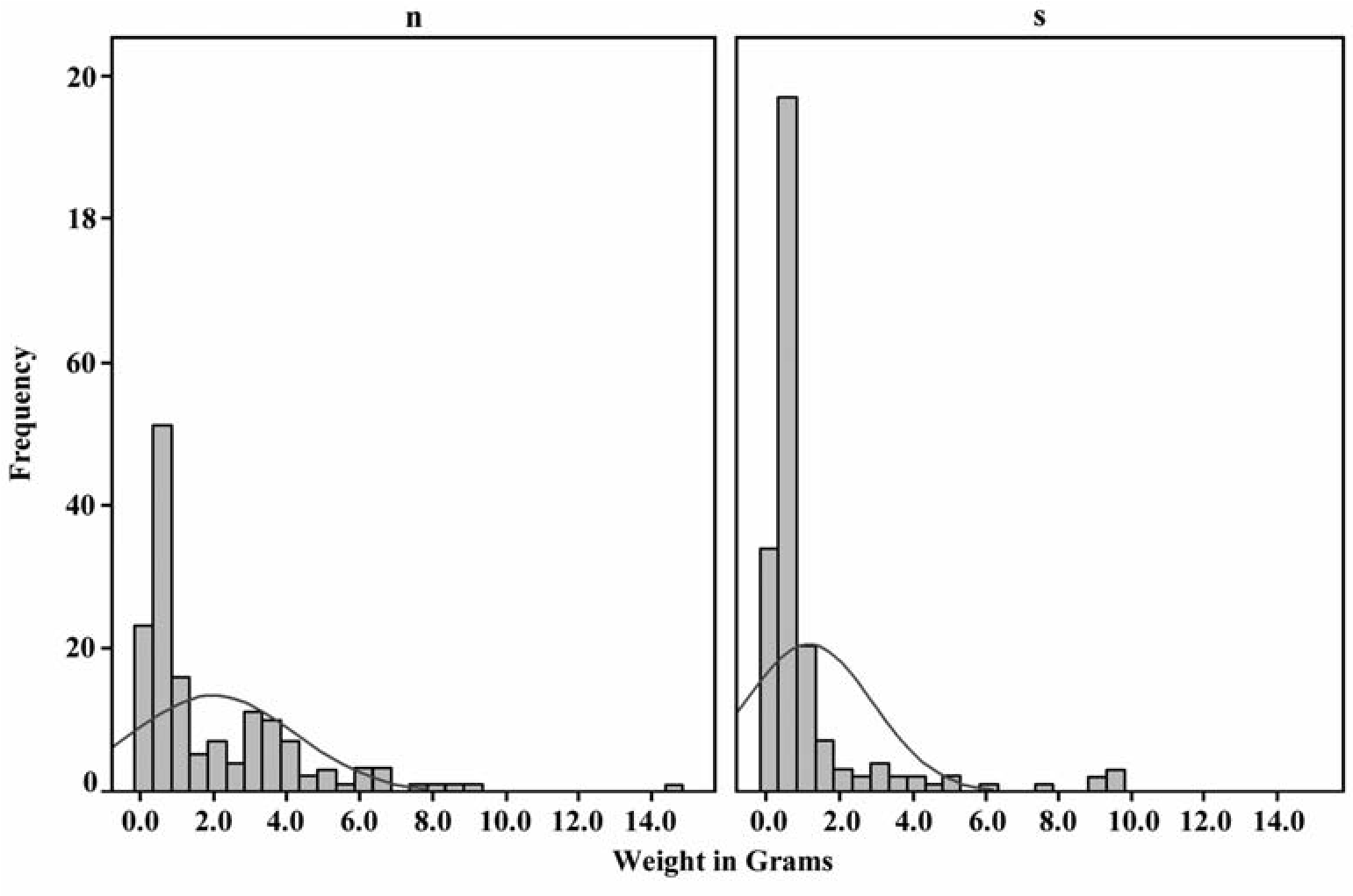

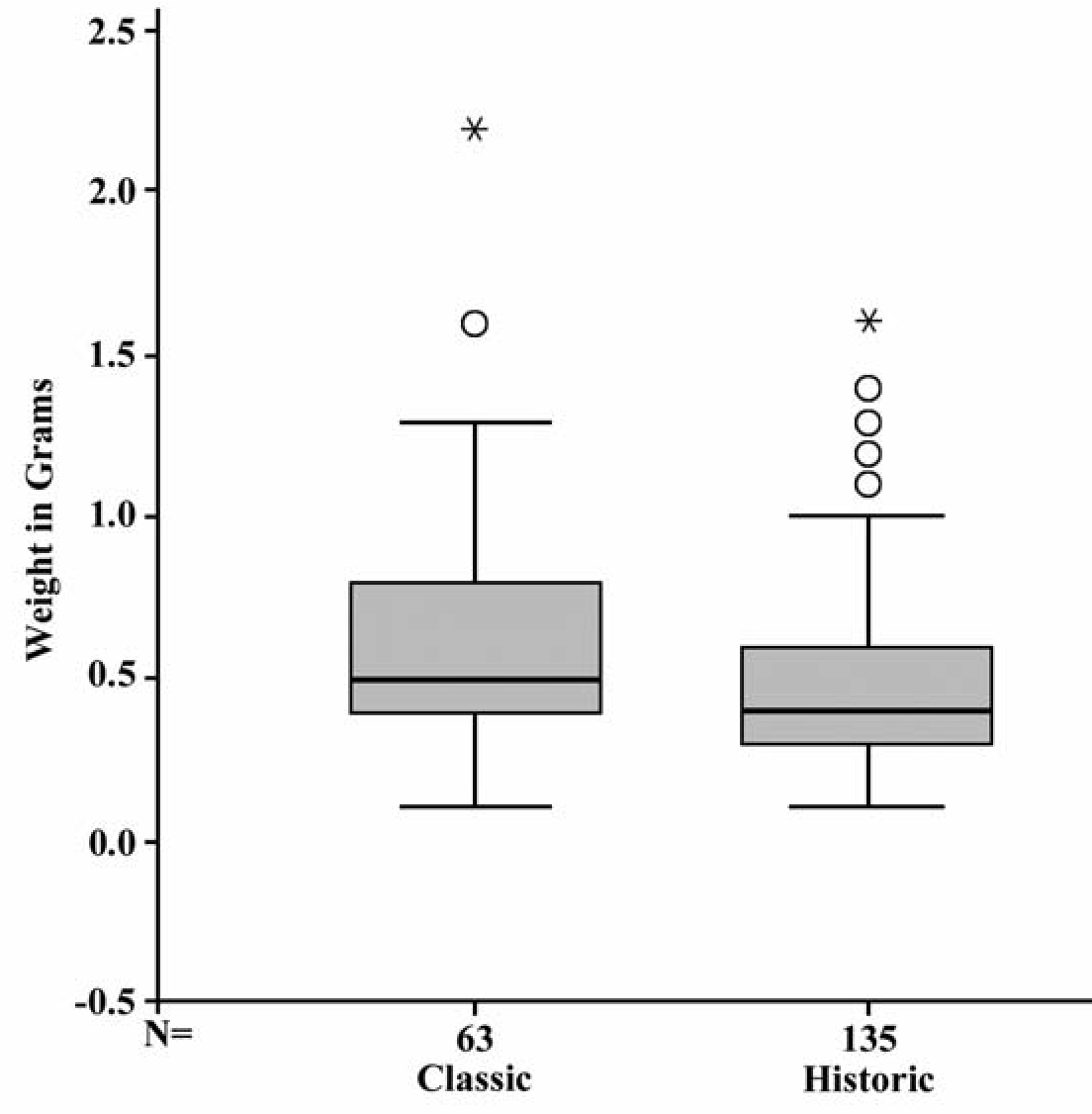

10.2. Histograms for projectile point weights, middle Gila River 146

10.3. Historic point weights, Gila River 146

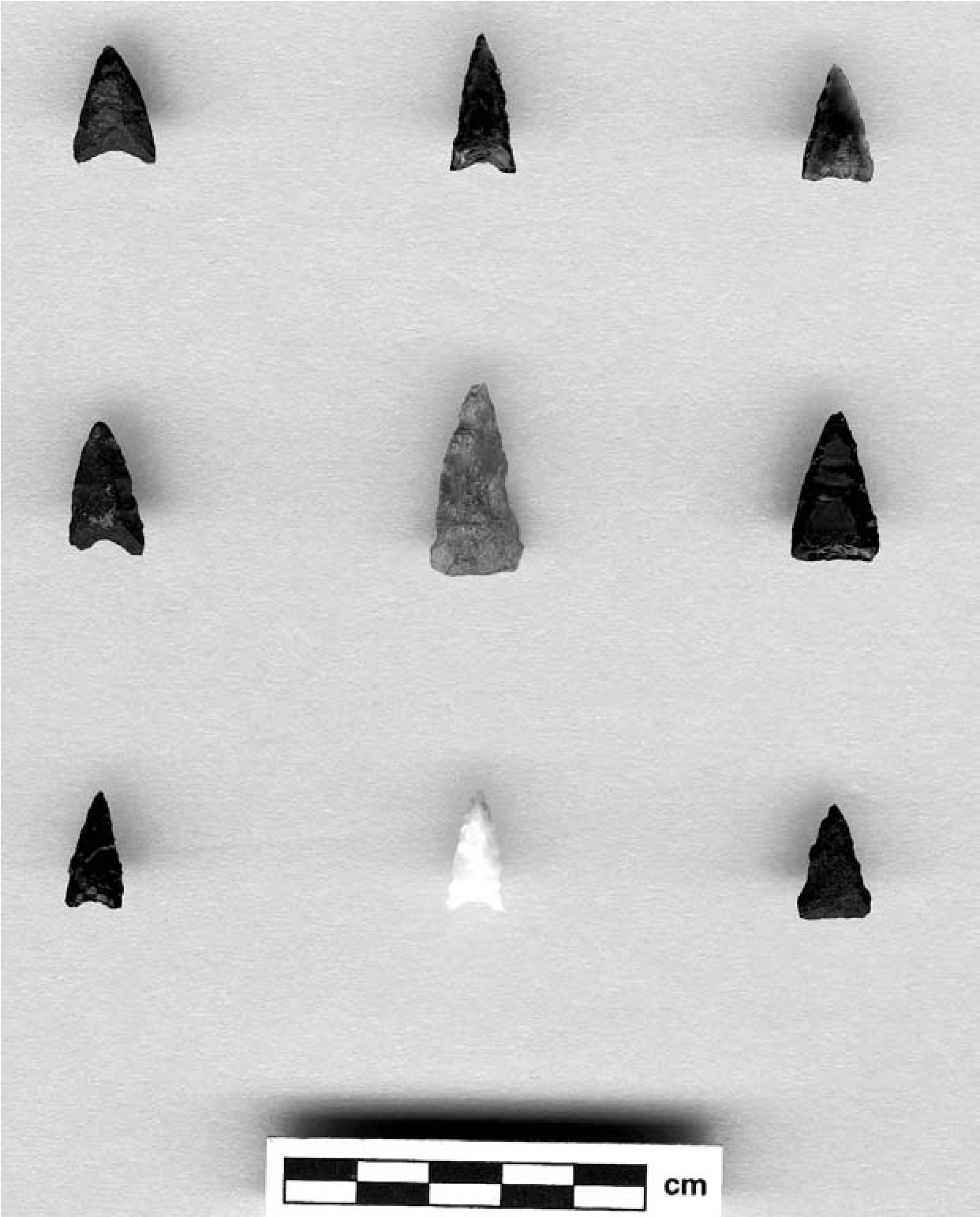

10.4. Projectile points collected from the Sacate site 148

10.5. Feature locations, cemeteries, and site segments at Sacate 150

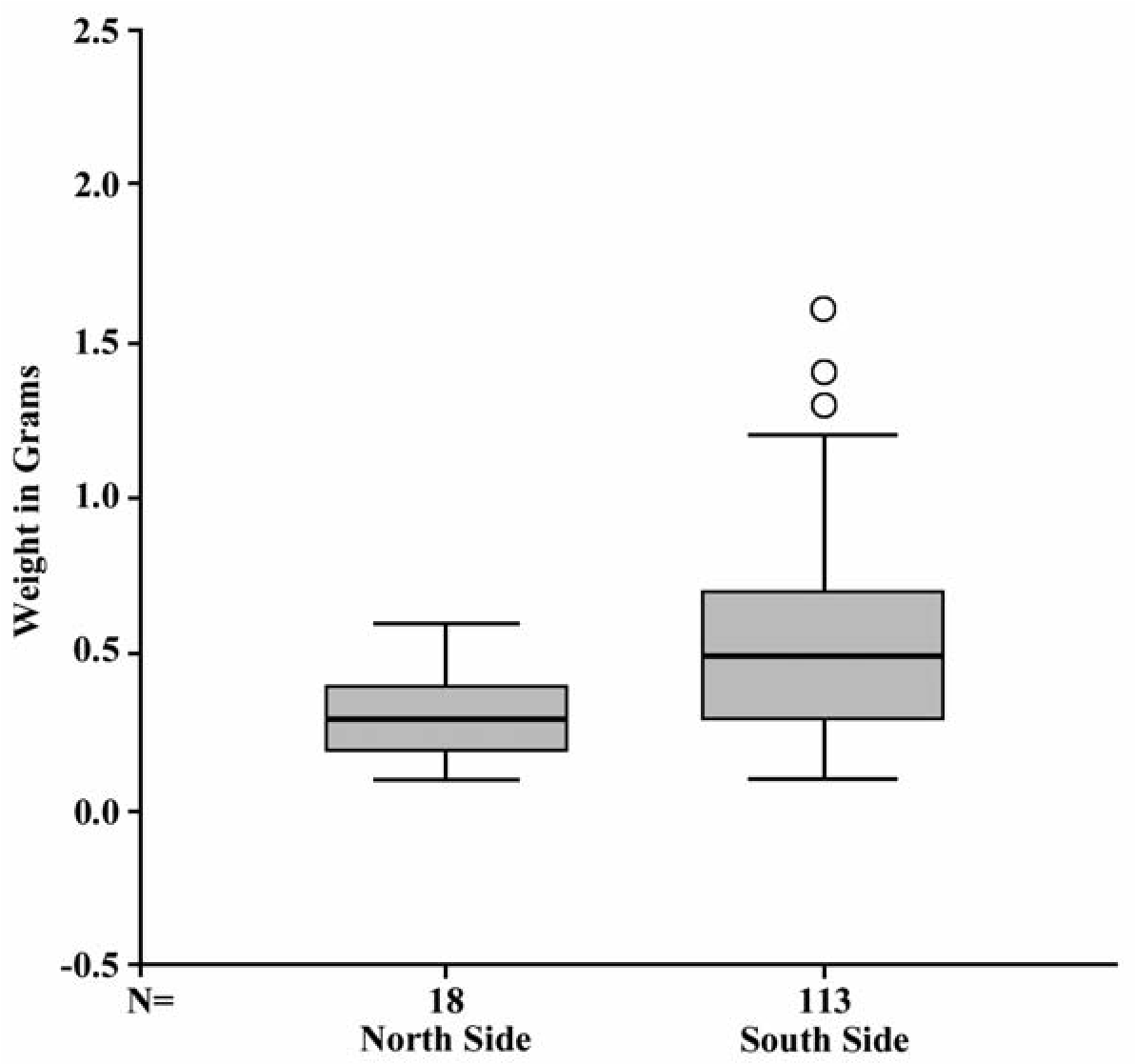

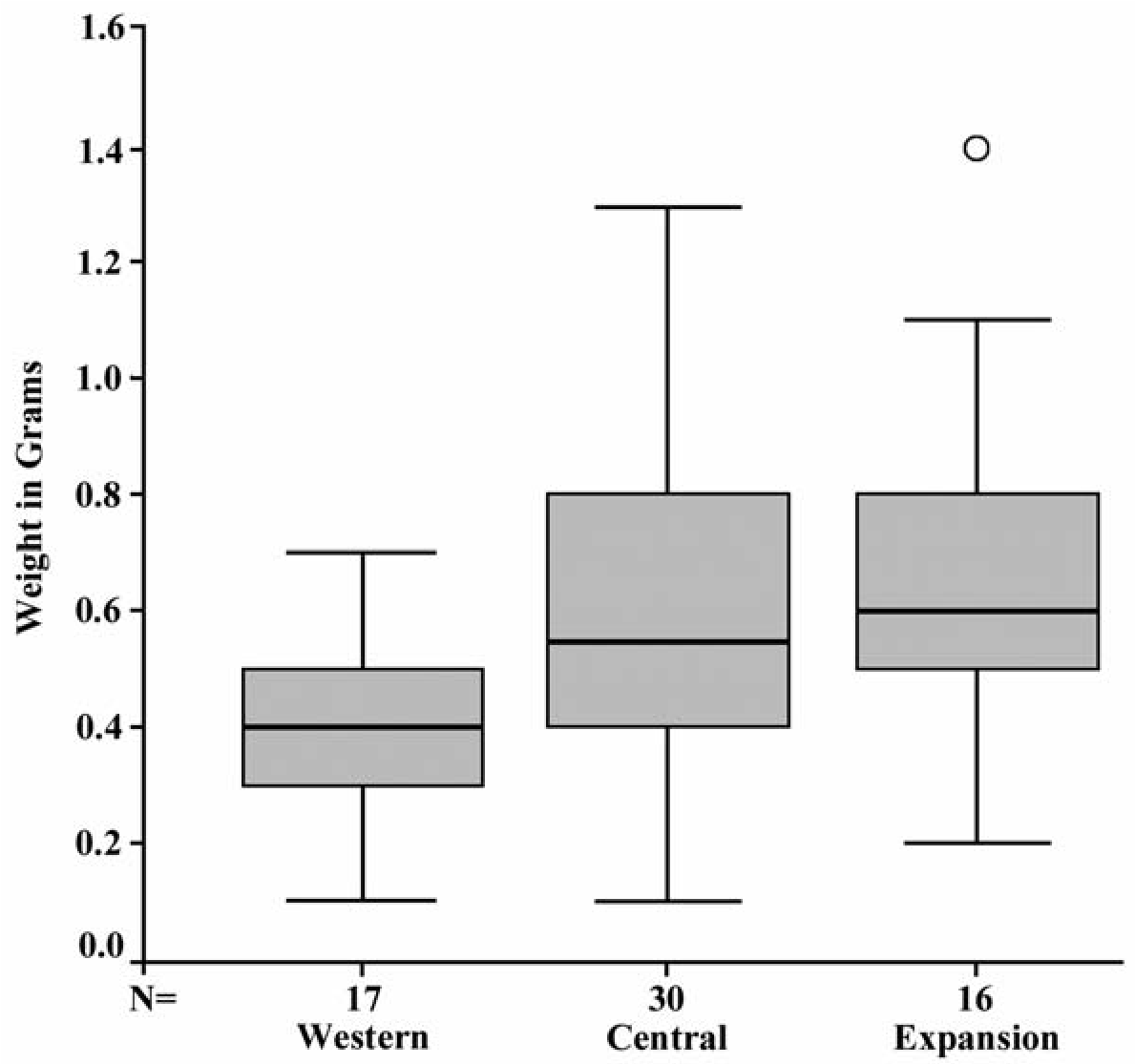

10.6. Point weight by site area at the Sacate site 151

10.7. Point weight for finished and complete projectile points 152

11.1. Sites discussed in the text 156

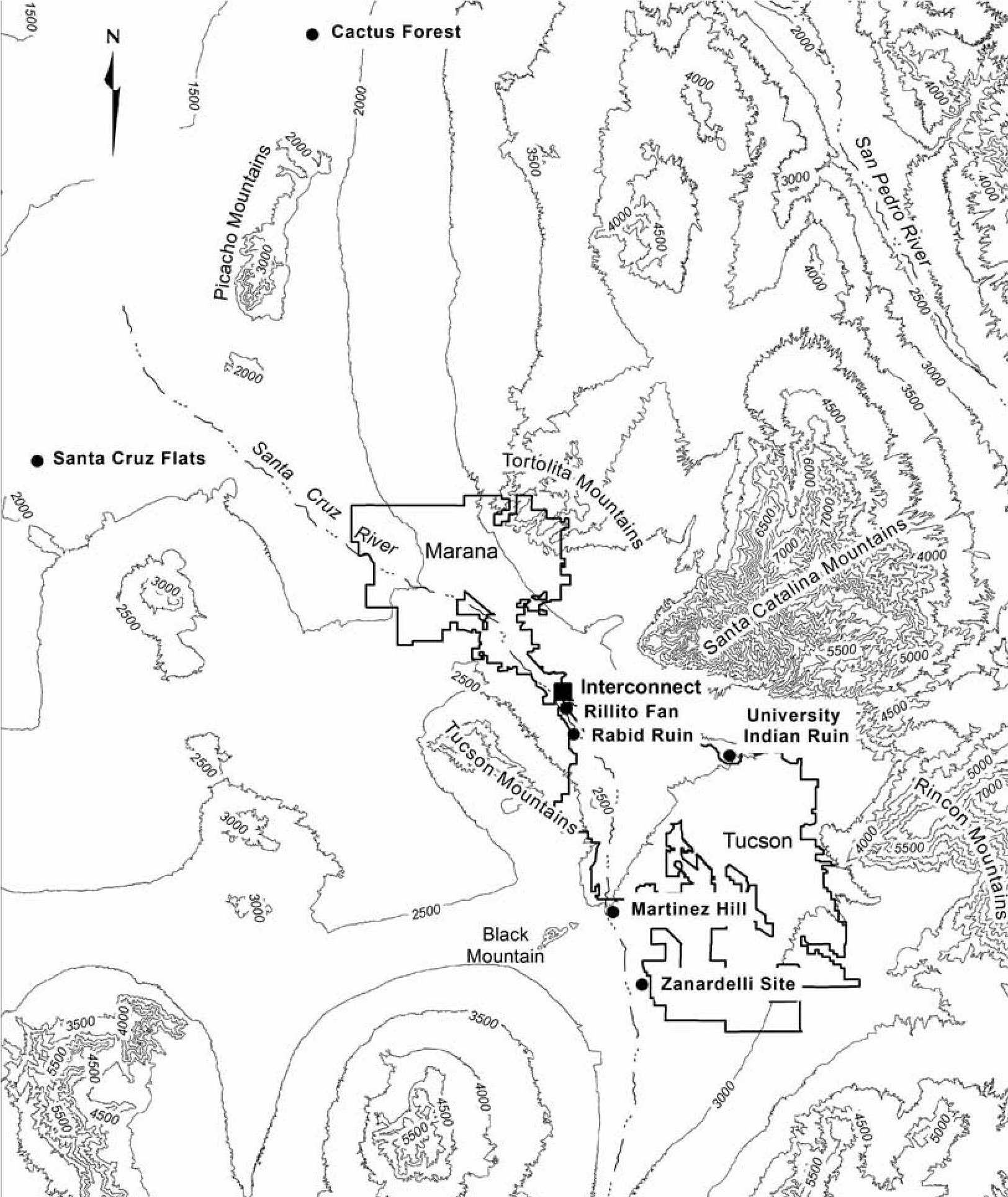

12.1. Locations of key Late Classic period sites in southern Arizona 162

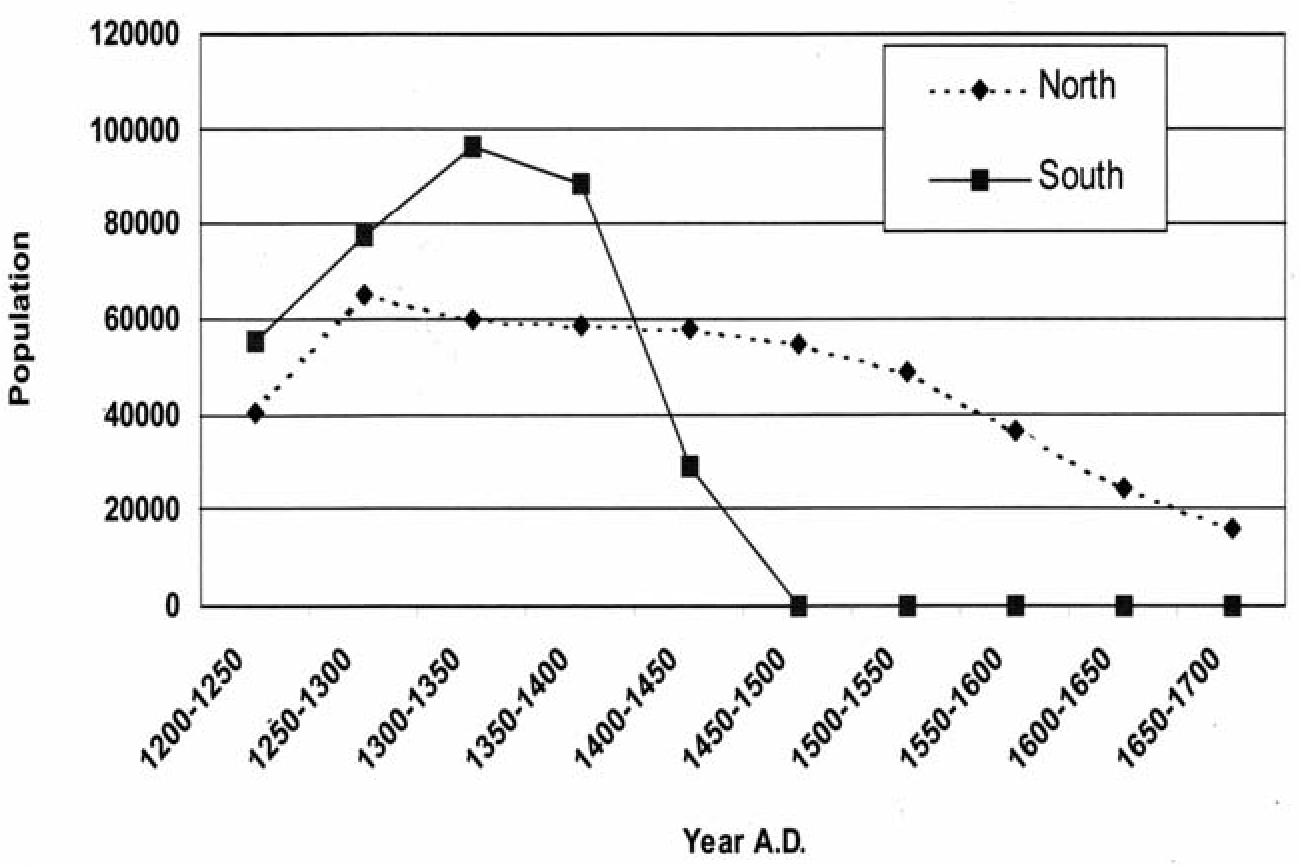

12.2. CCD population trends by region 163

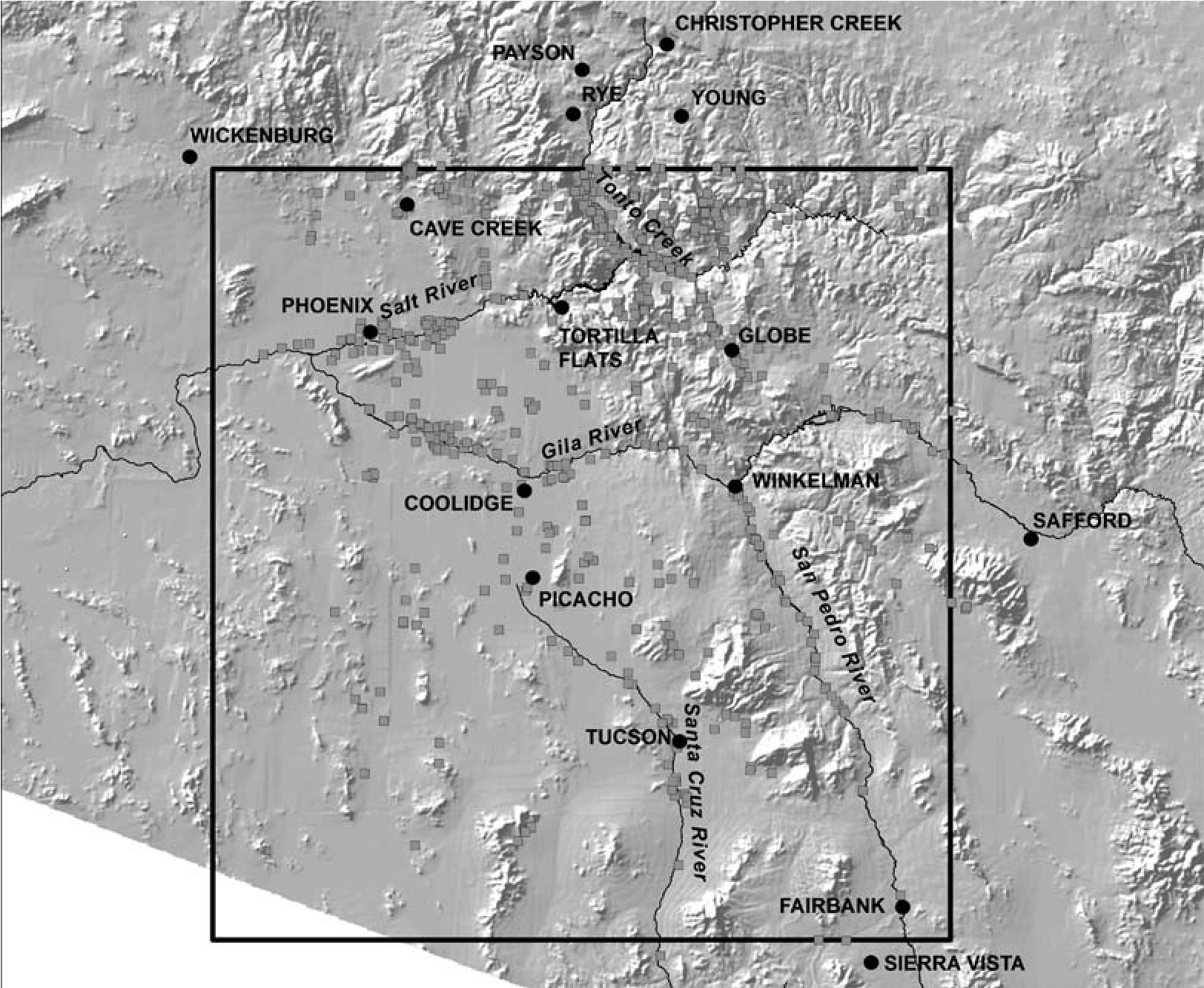

12.3. CCD sites in the Hohokam region 164

12.4. Rillito Fan and Cactus Forest sites 165

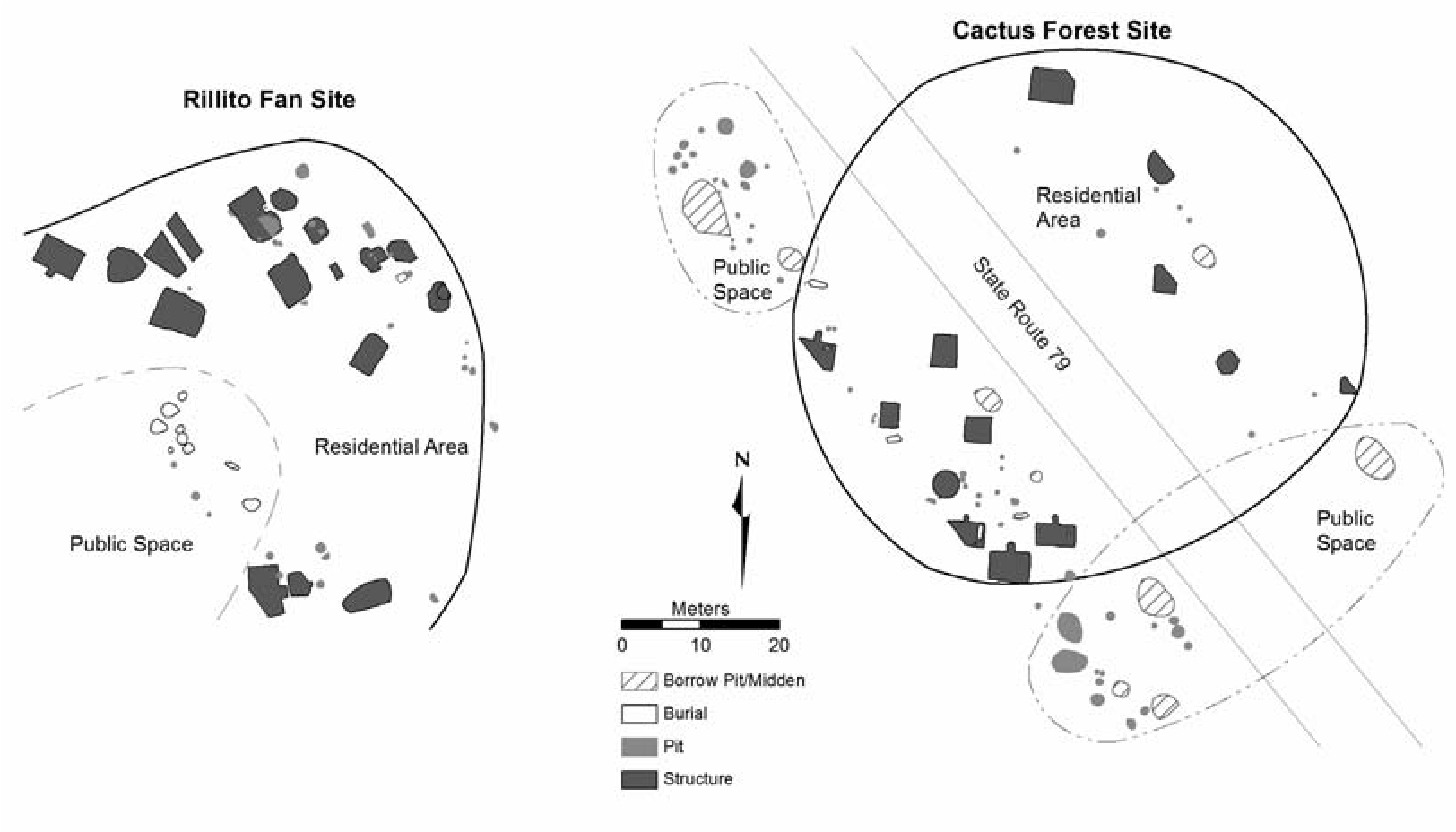

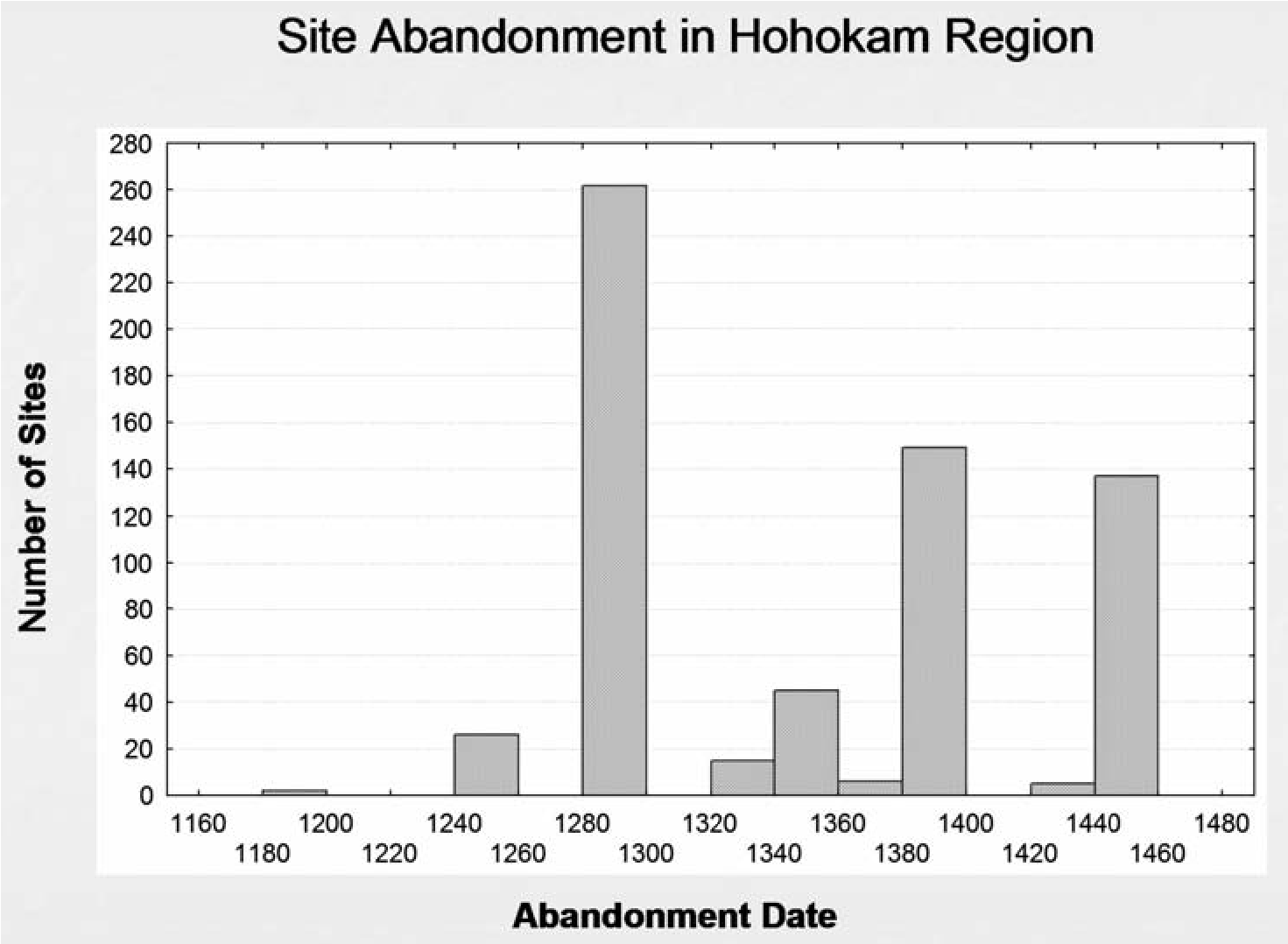

12.5. CCD site abandonment data for the Hohokam region 167

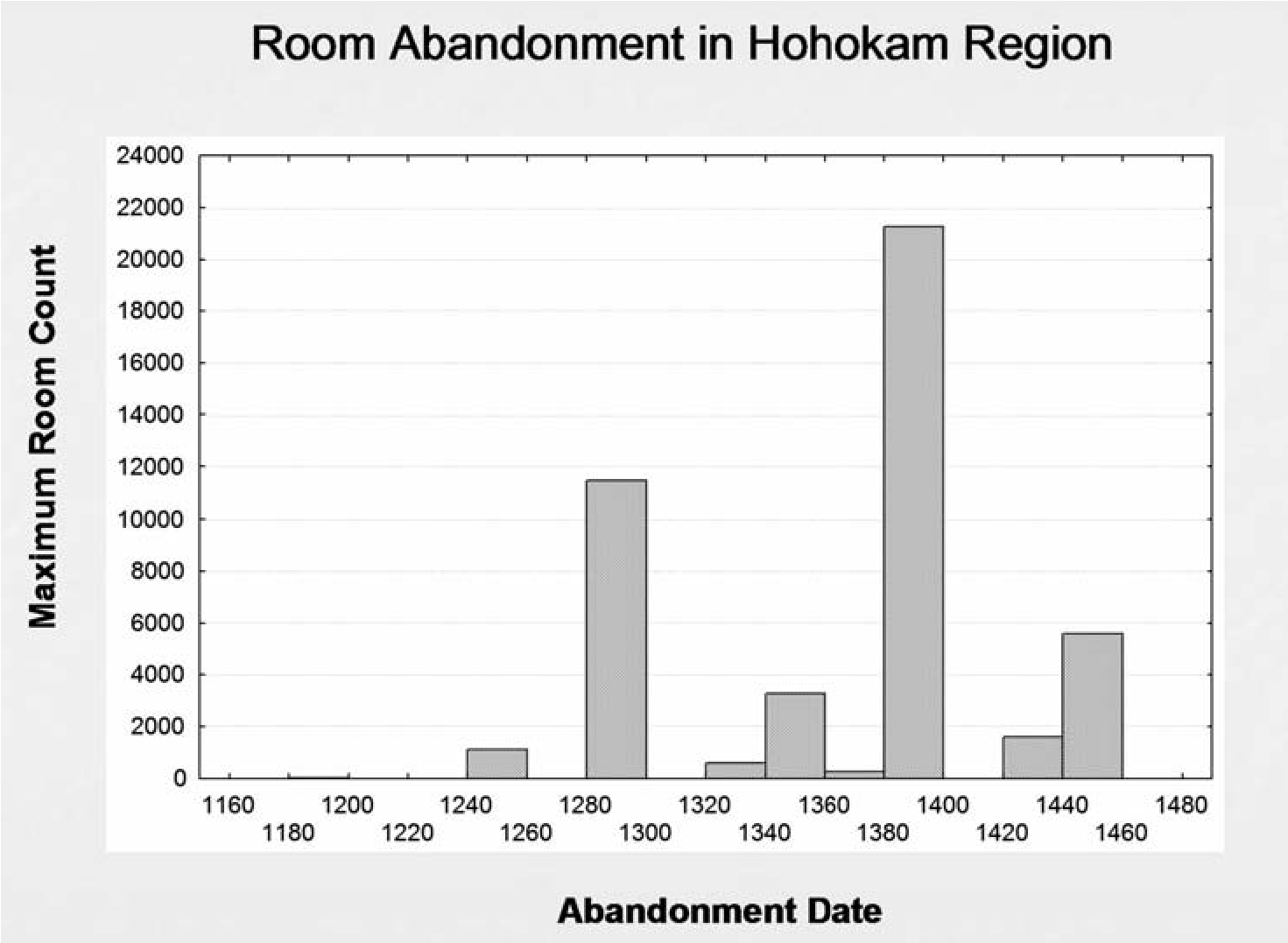

12.6. CCD room abandonment data for the Hohokam region 168

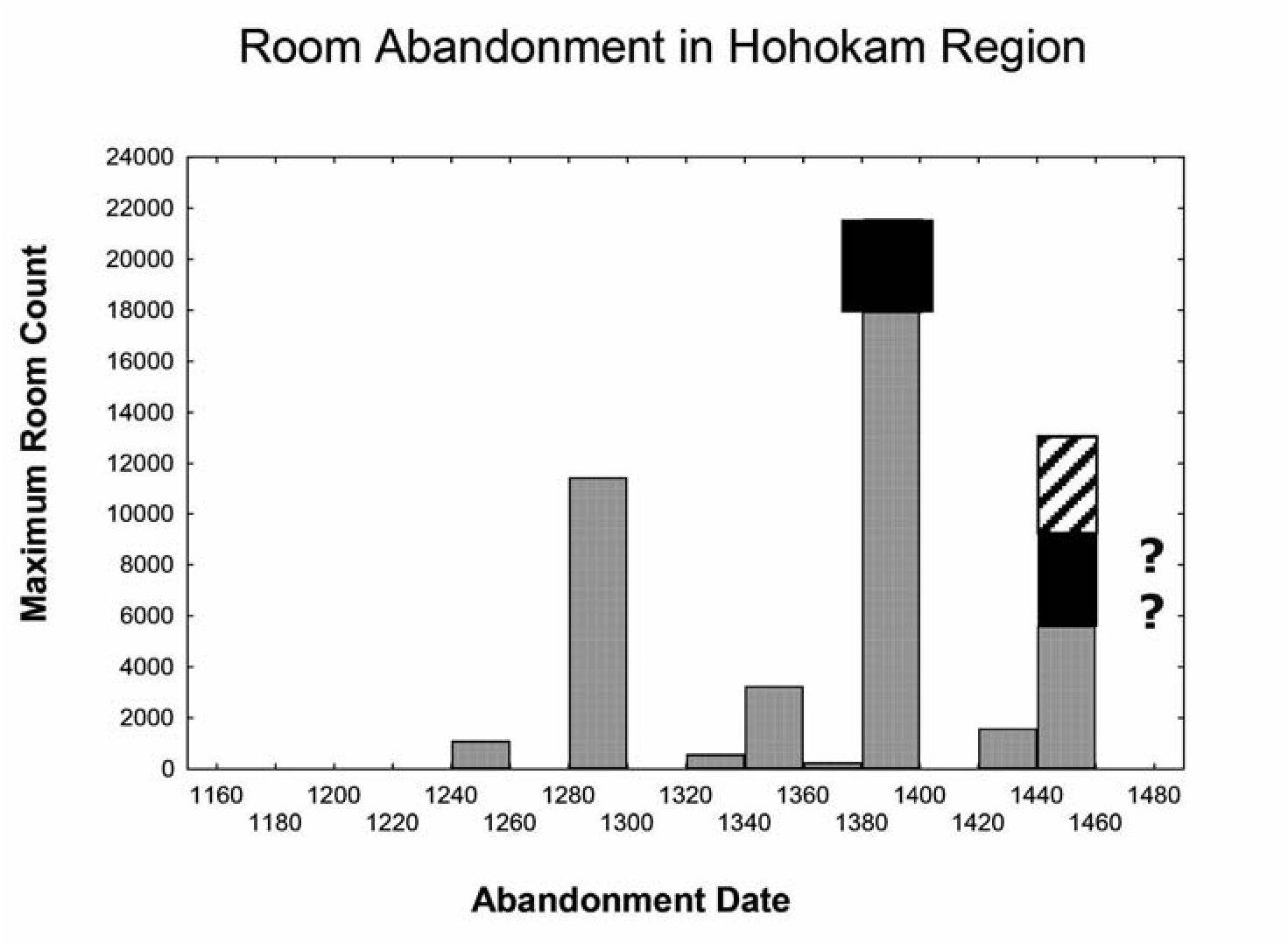

12.7. Suggested modifications to CCD room count data 169

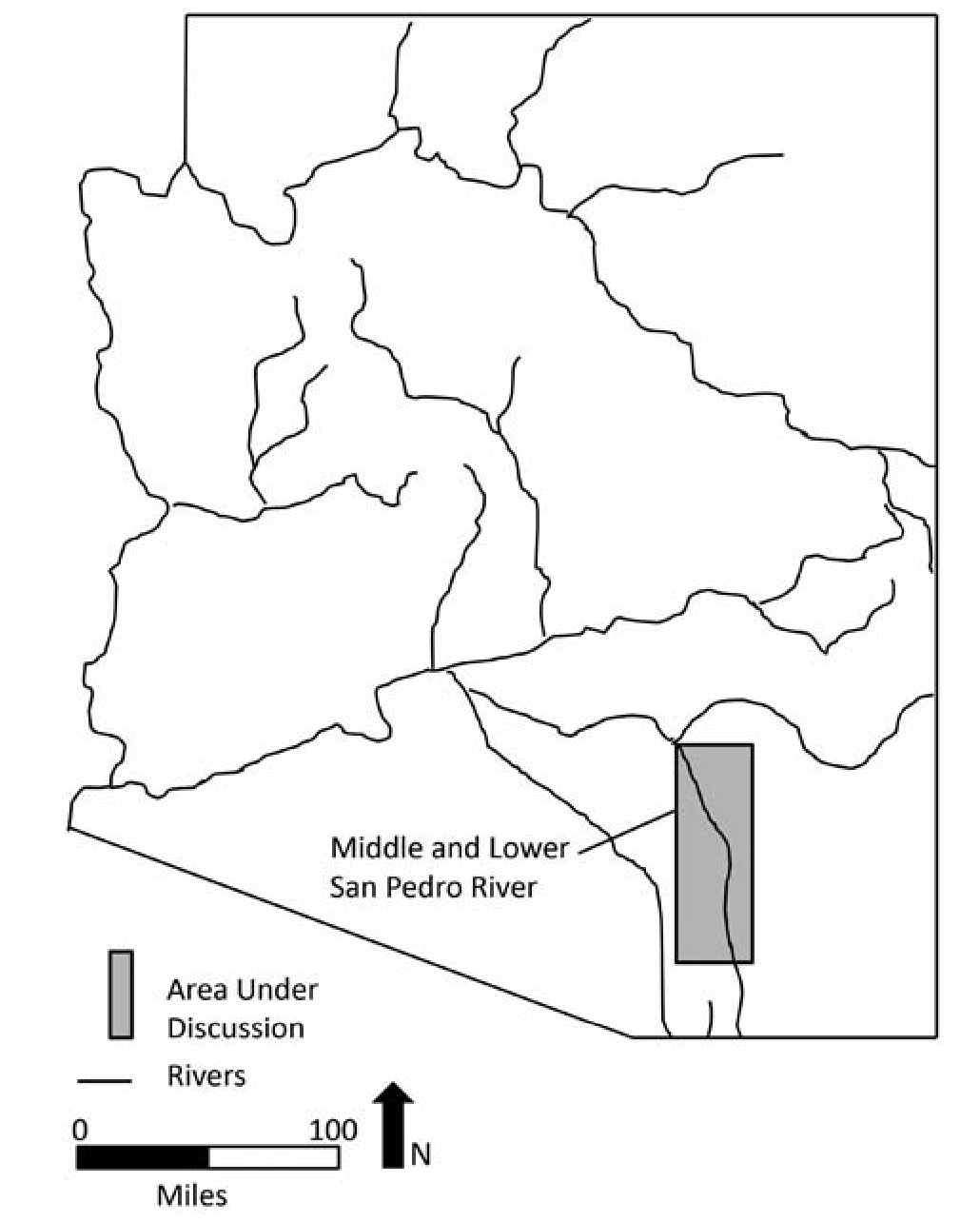

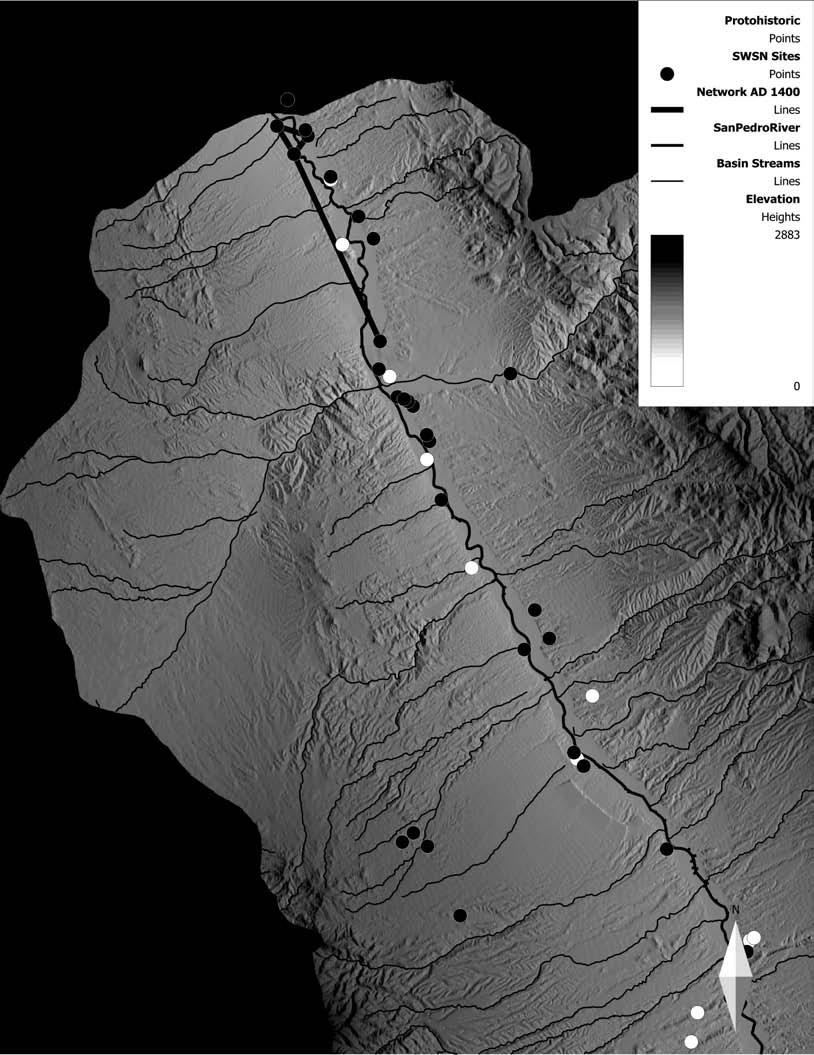

13.1. Location of the middle and lower San Pedro River 172

13.2. Locations of sites on the middle and lower San Pedro River 178

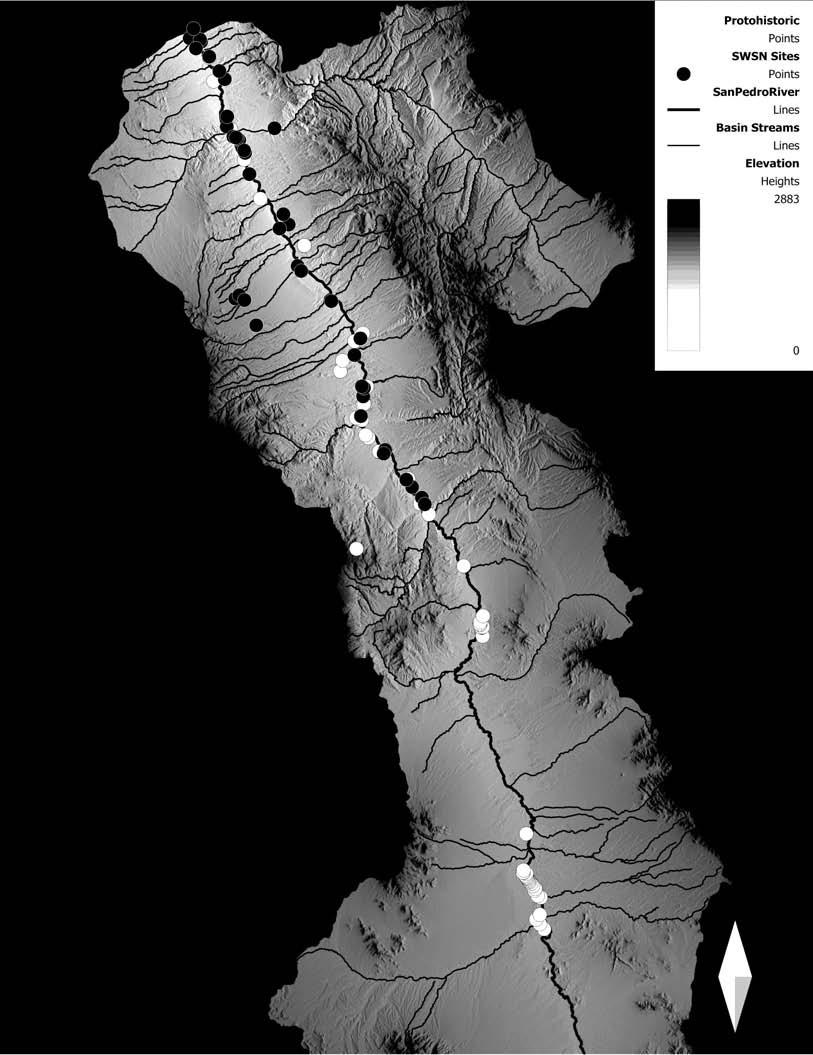

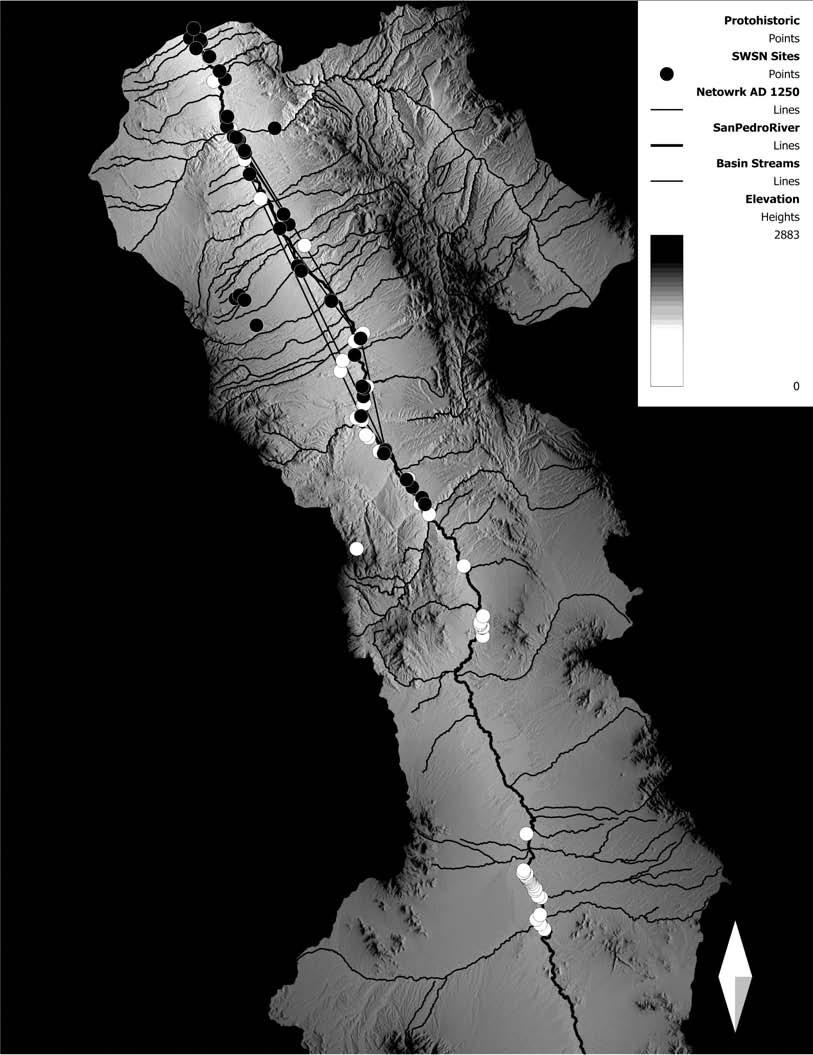

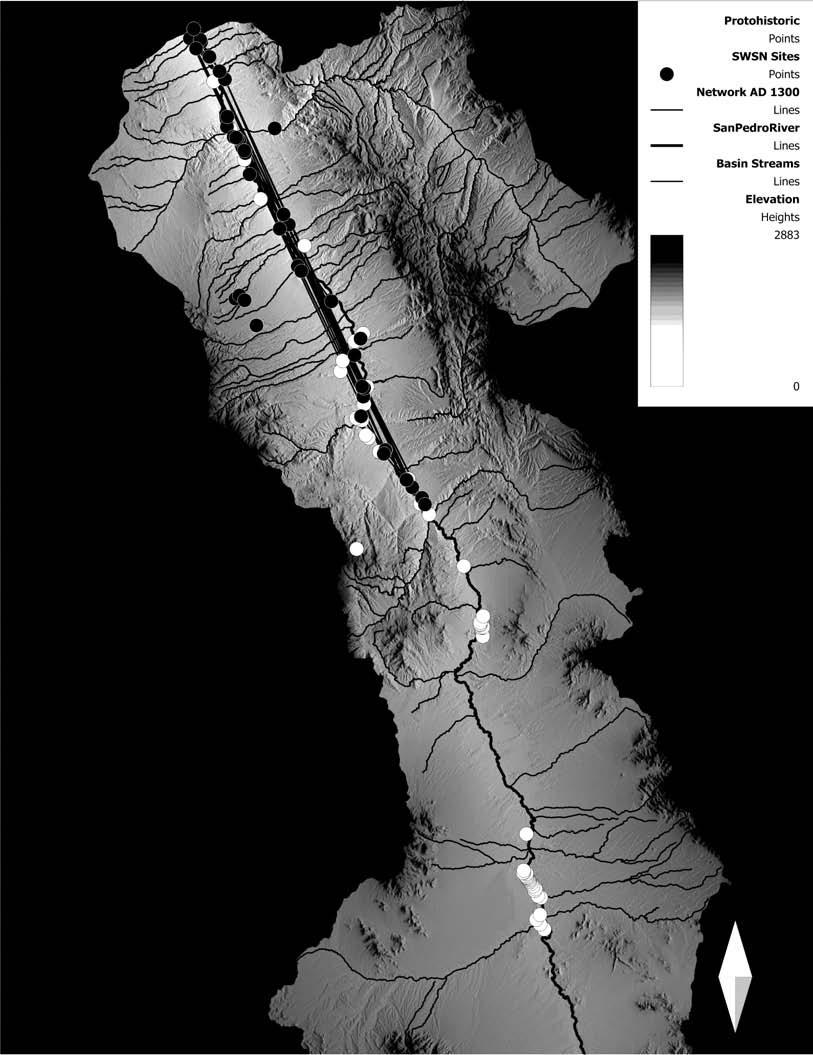

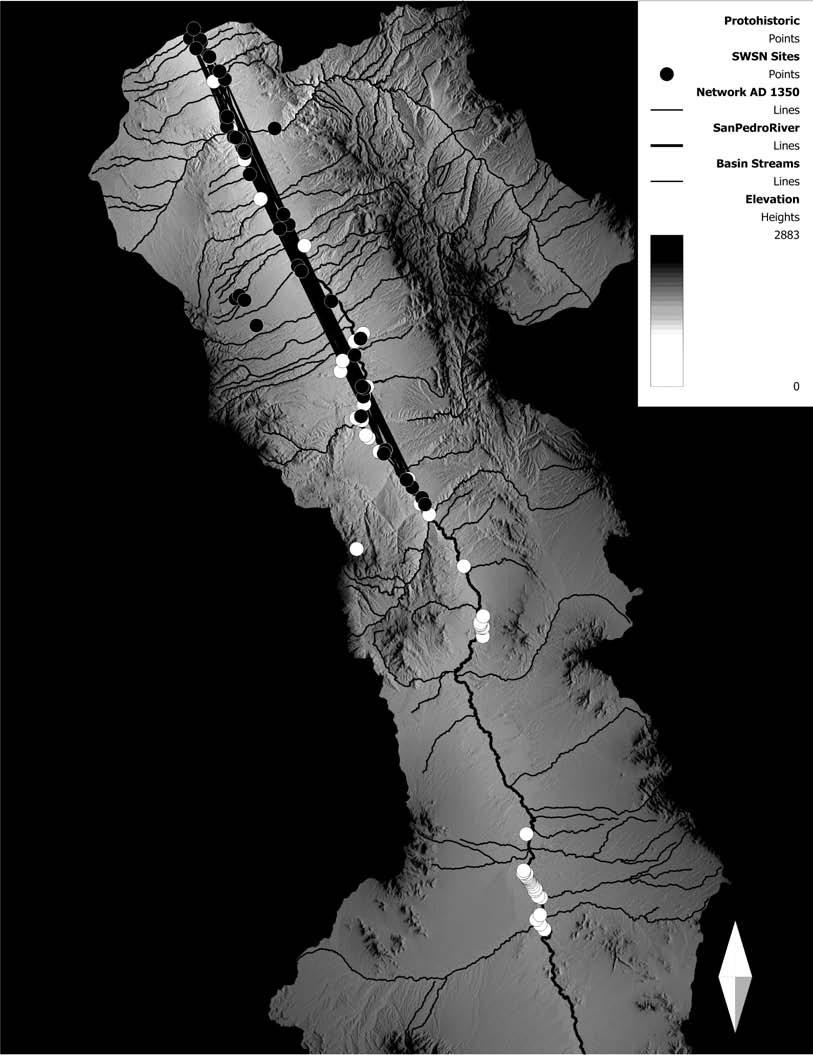

13.3. Network connections among sites in the SWSN database, ad 1250 179

13.4. Network connections among sites in the SWSN database, ad 1300 180

13.5. Network connections among sites in the SWSN database, ad 1350 181

13.6. Network connections among sites in the SWSN database, ad 1400 182

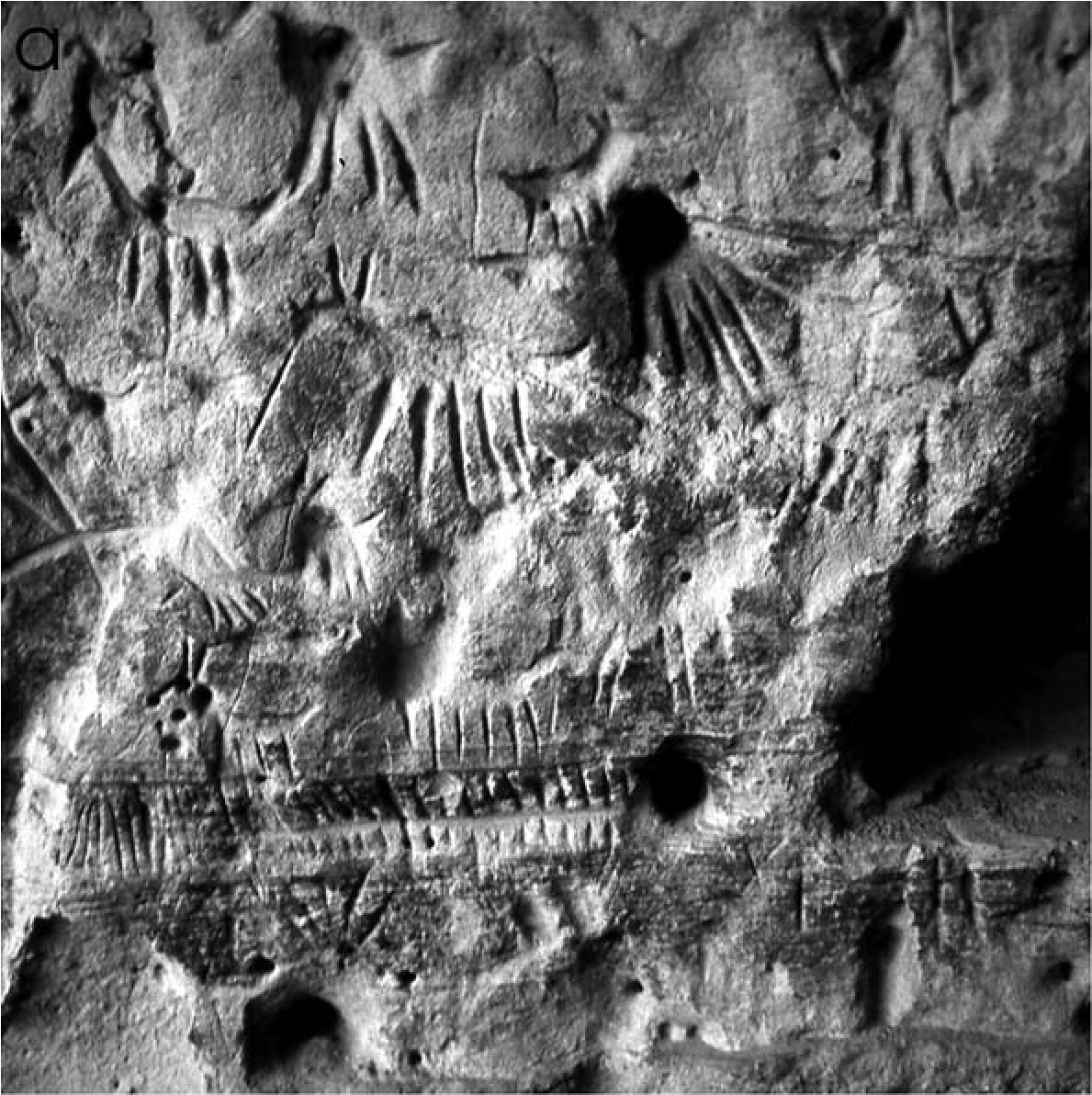

14.1. Antelope trap petroglyph 190

14.2. Navajo deity Monster Slayer with antelope trap 191

14.3. NLC trap site S-MLC-LP-A in Arizona 192

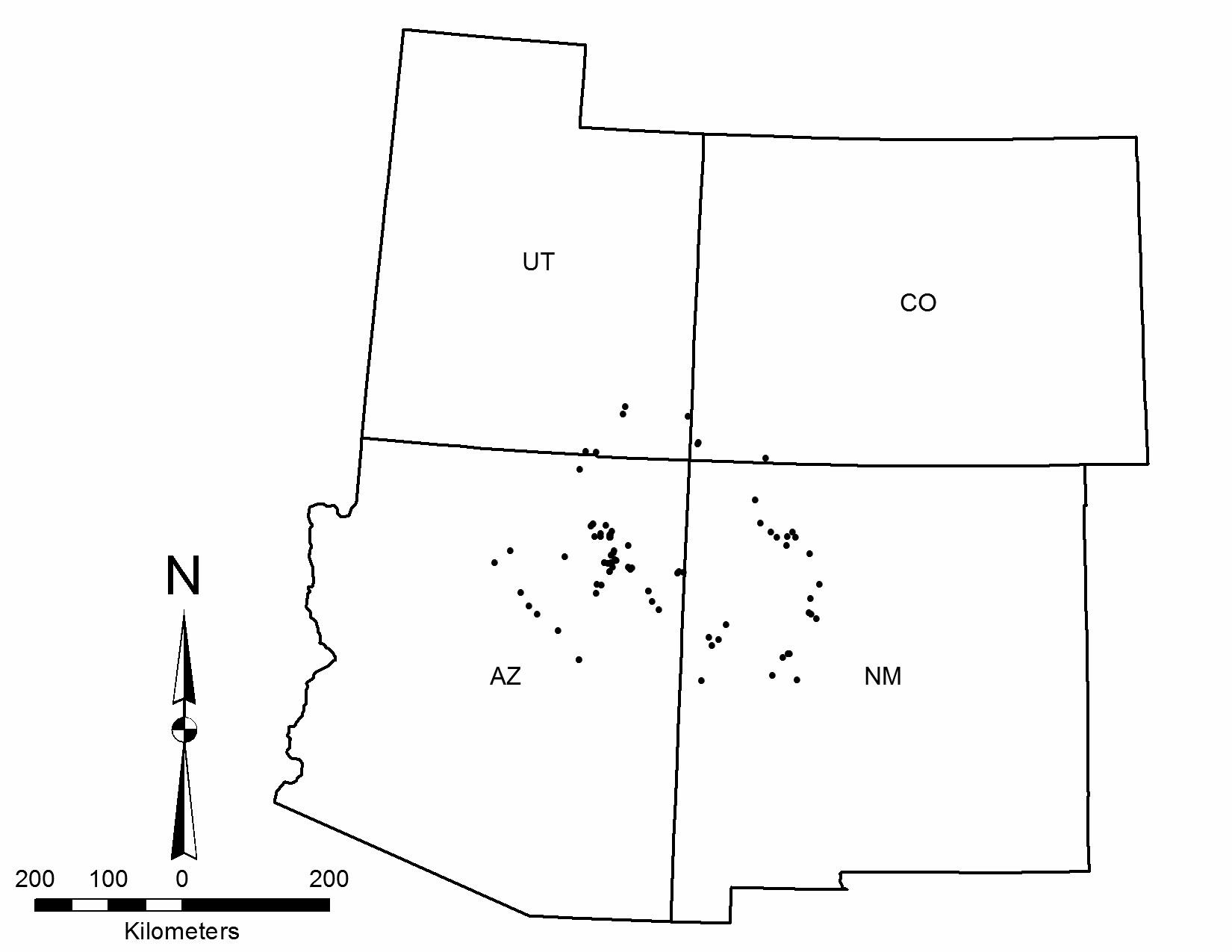

14.4. Distribution of Navajo game traps on the Colorado Plateau 193

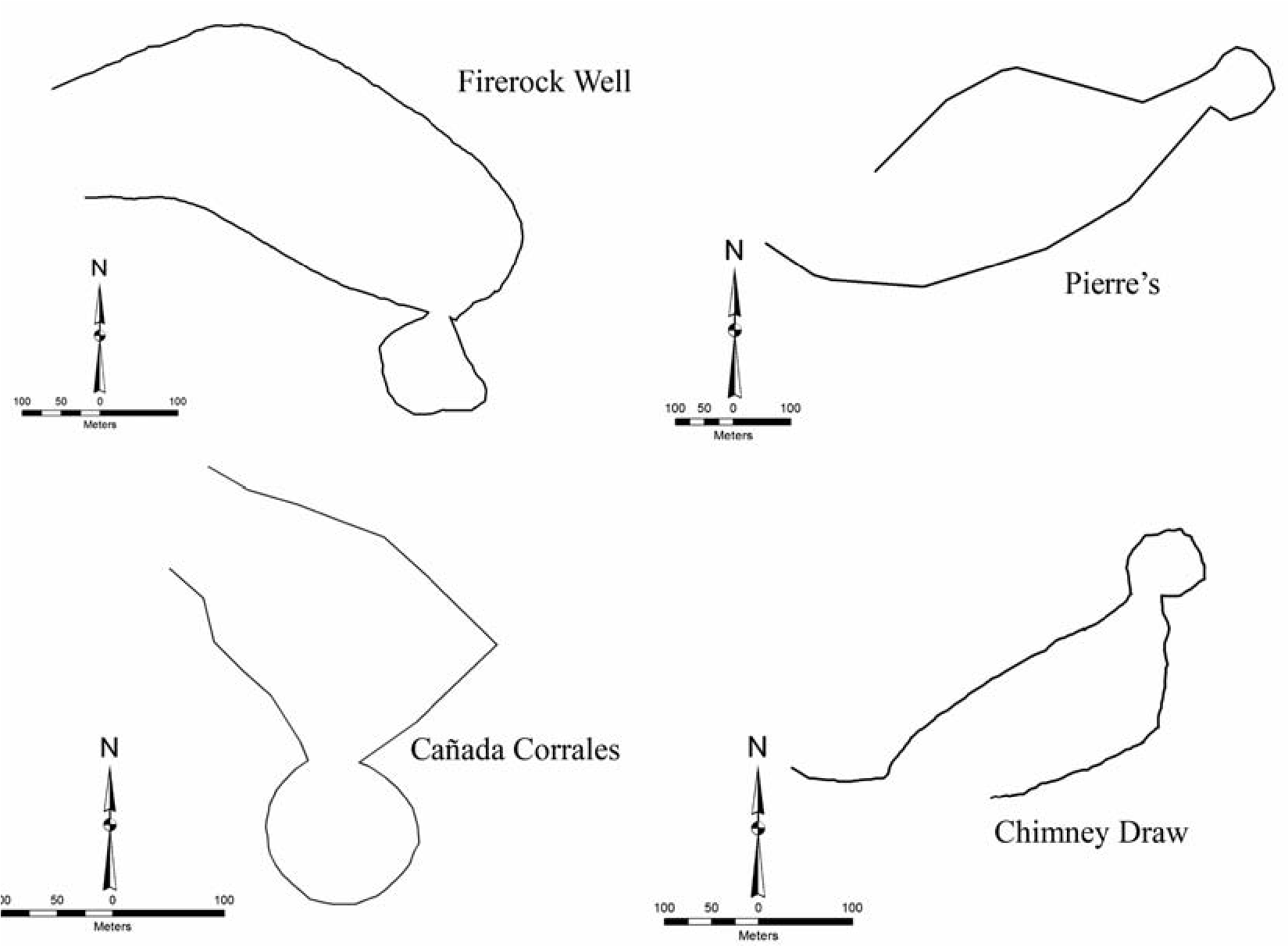

14.5. Game traps from the San Juan Basin 195

15.1. Map of known wickiup sites in Colorado 199

15.2. Plan map of the Ute Hunters’ Camp 204

15.3. Artist’s interpretation of the Ute Hunter’s Camp 205

15.4. Plan map of the Pisgah Wickiup Village 206

15.5. Metal artifacts from the Pisgah Wickiup Village: projectile points 207

15.6. Metal artifacts from the Pisgah Wickiup Village: tinklers 208

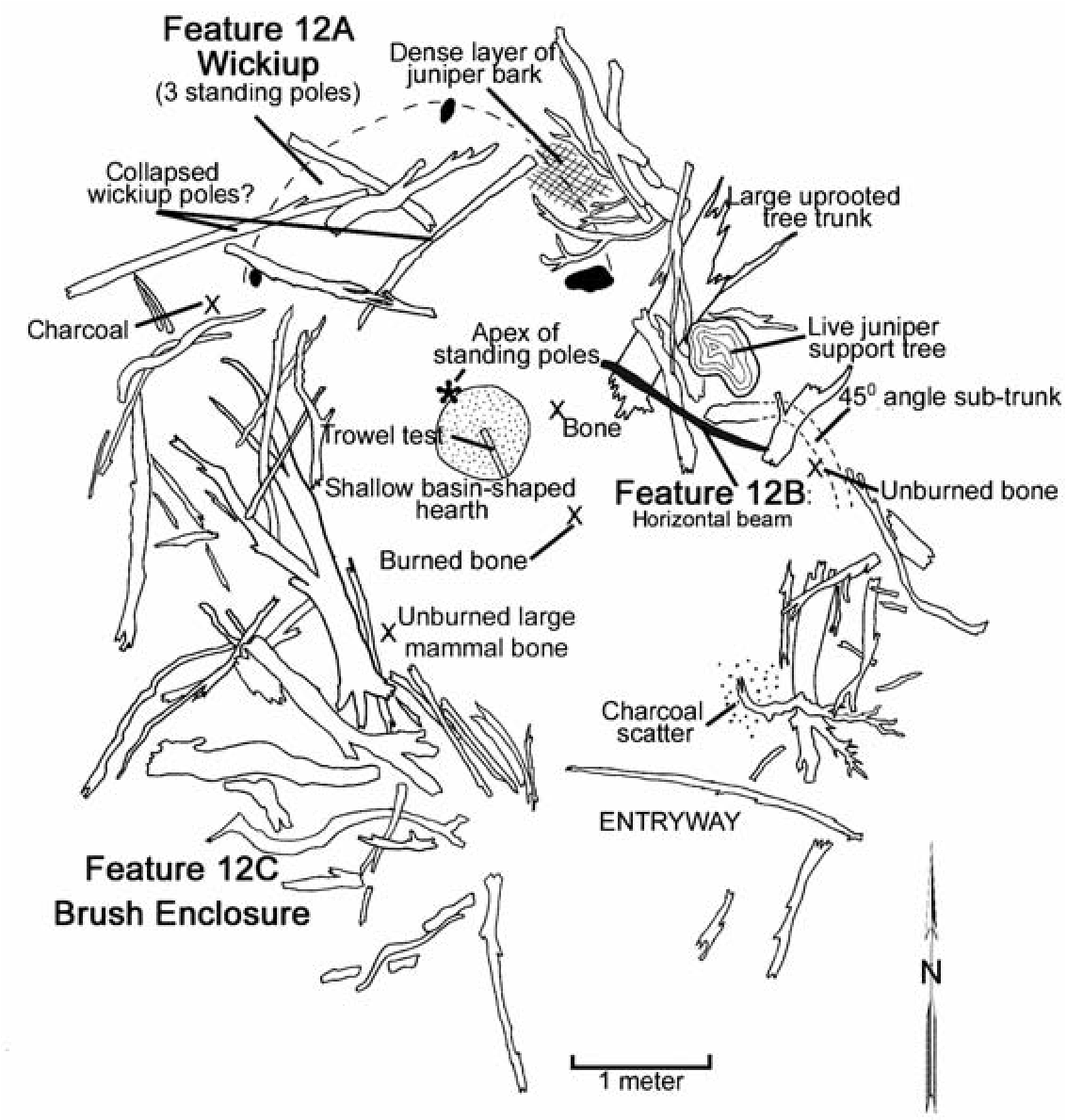

15.7. Plan map of Feature 12 at the Pisgah Wickiup Village 208

15.8. Feature 12 at the Pisgah Wickiup Village 209

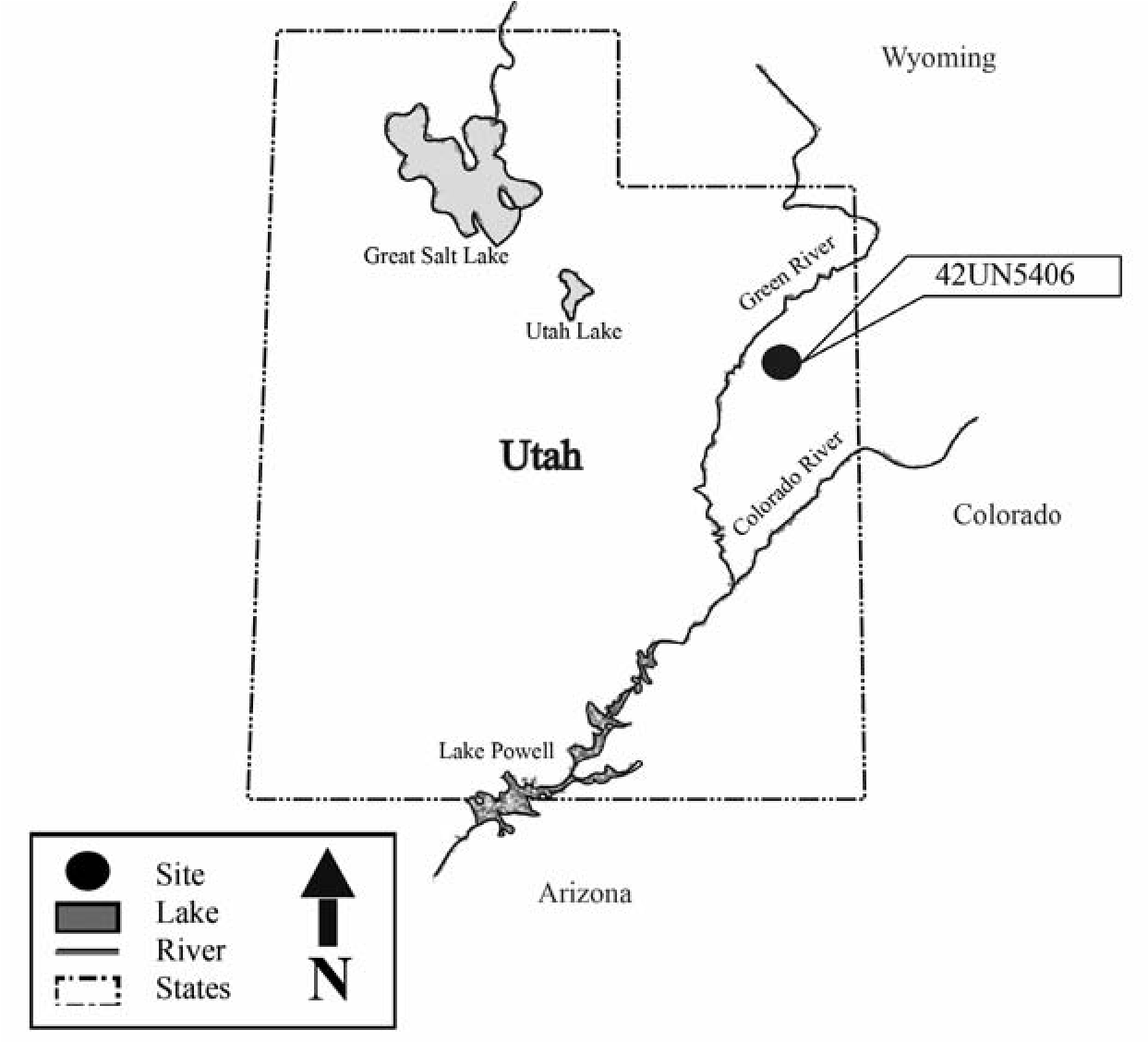

16.1. Location of 42UN5406 213

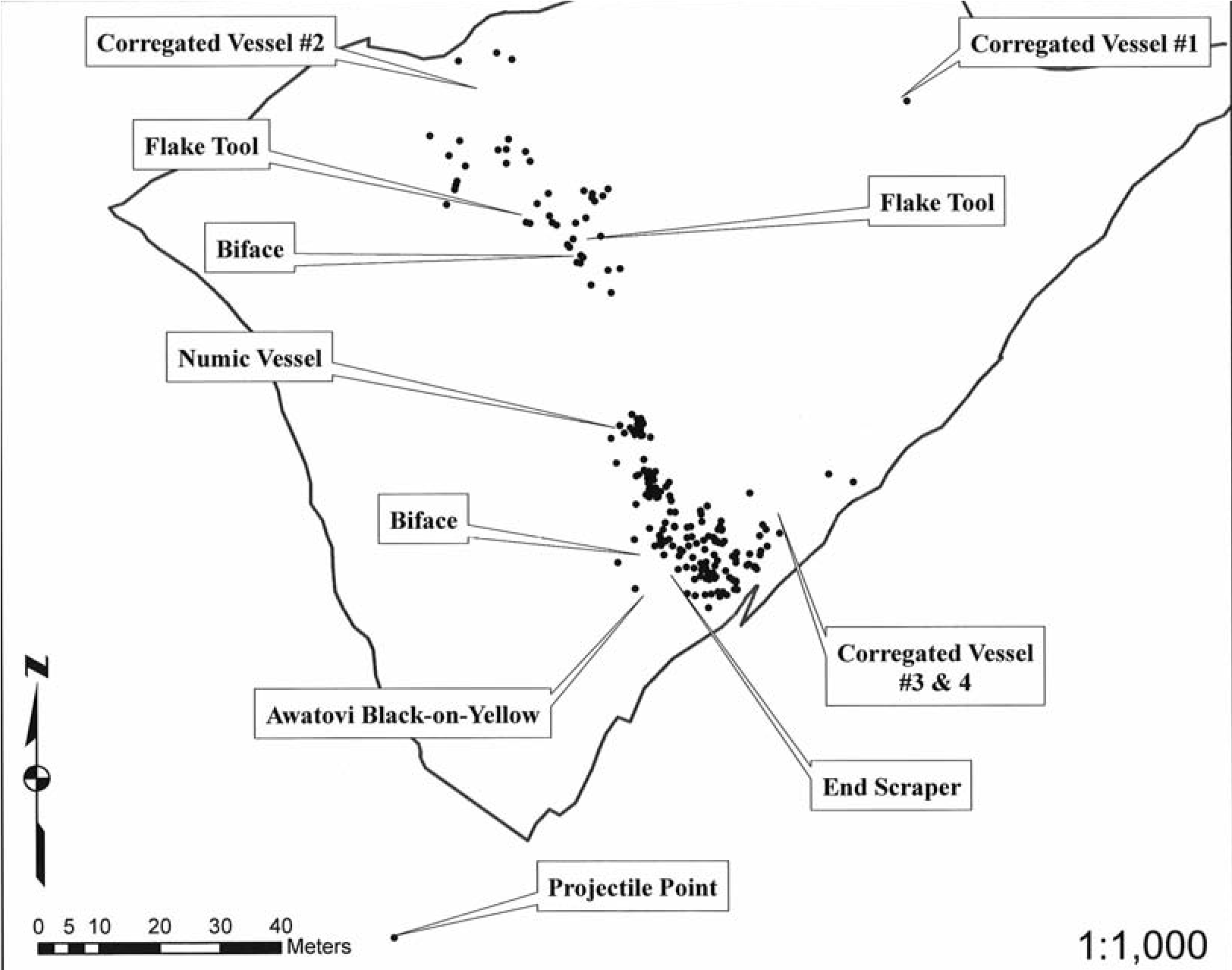

16.2. Overview of 42UN5406 214

16.3. Map of 42UN5406 214

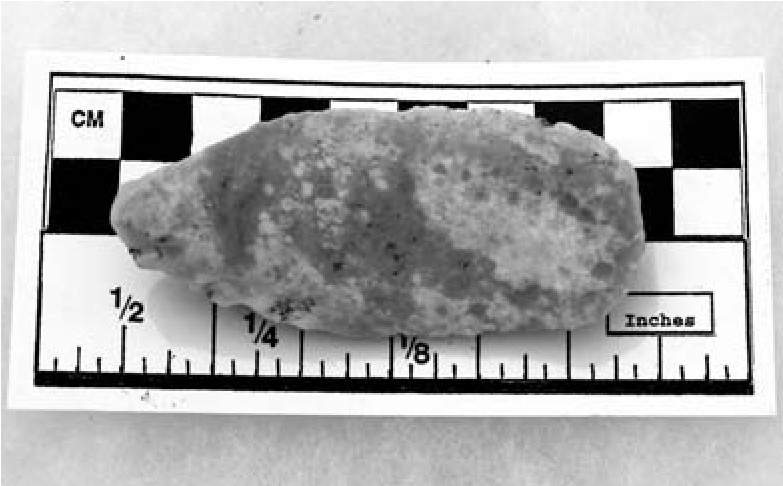

16.4. Desert Side-notched projectile point from 42UN5406 215

16.5. Scraper from 42UN5406 215

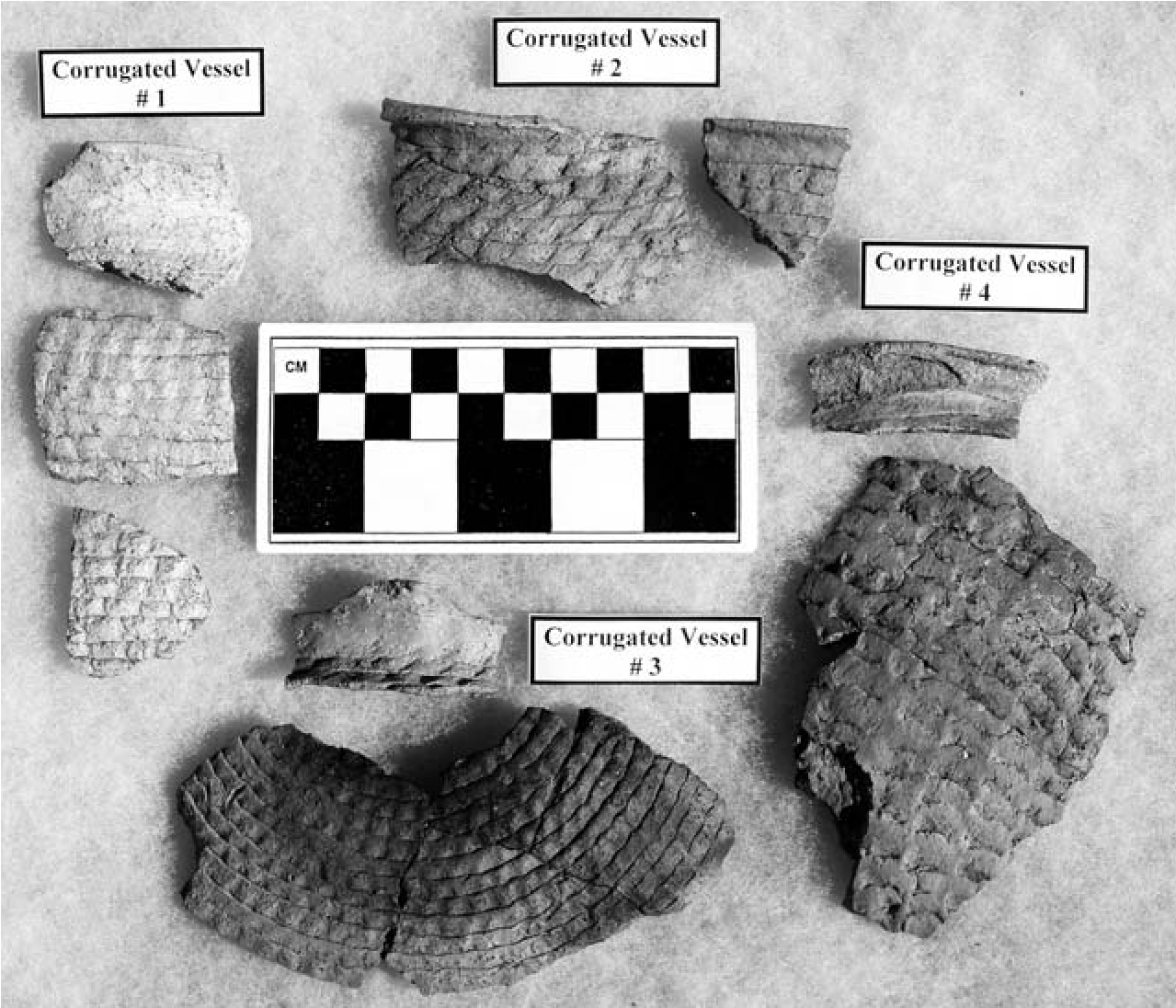

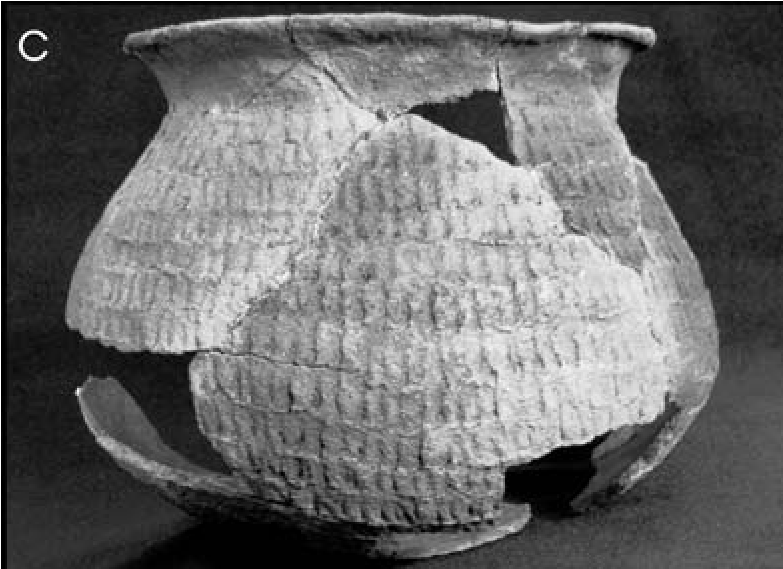

16.6. Rim sherds from corrugated vessels from 42UN5406 216

16.7. Sherds of Awatovi Black-on-yellow from 42UN5406 218

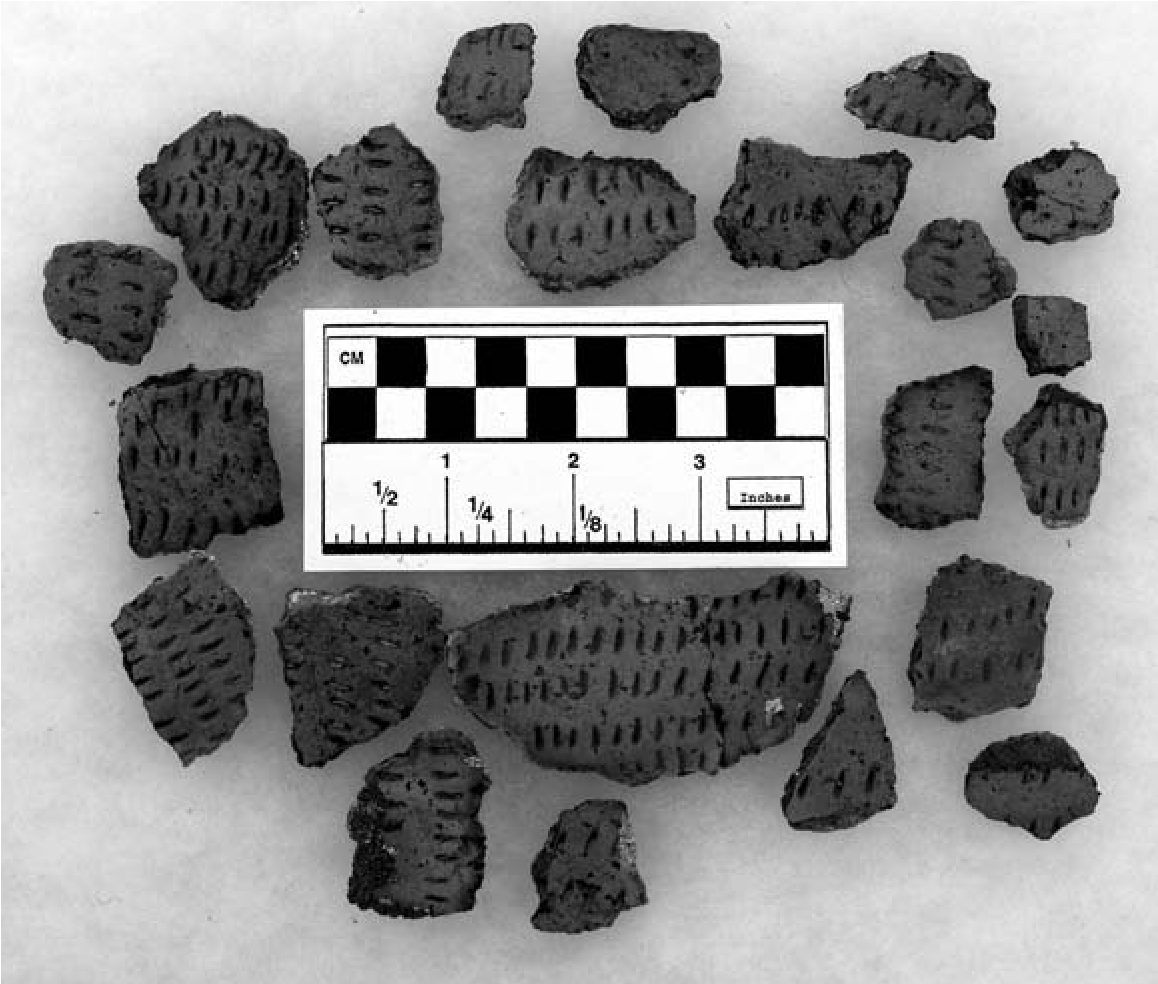

16.8. Uncompahgre Brownware ceramics from 42UN5406 219

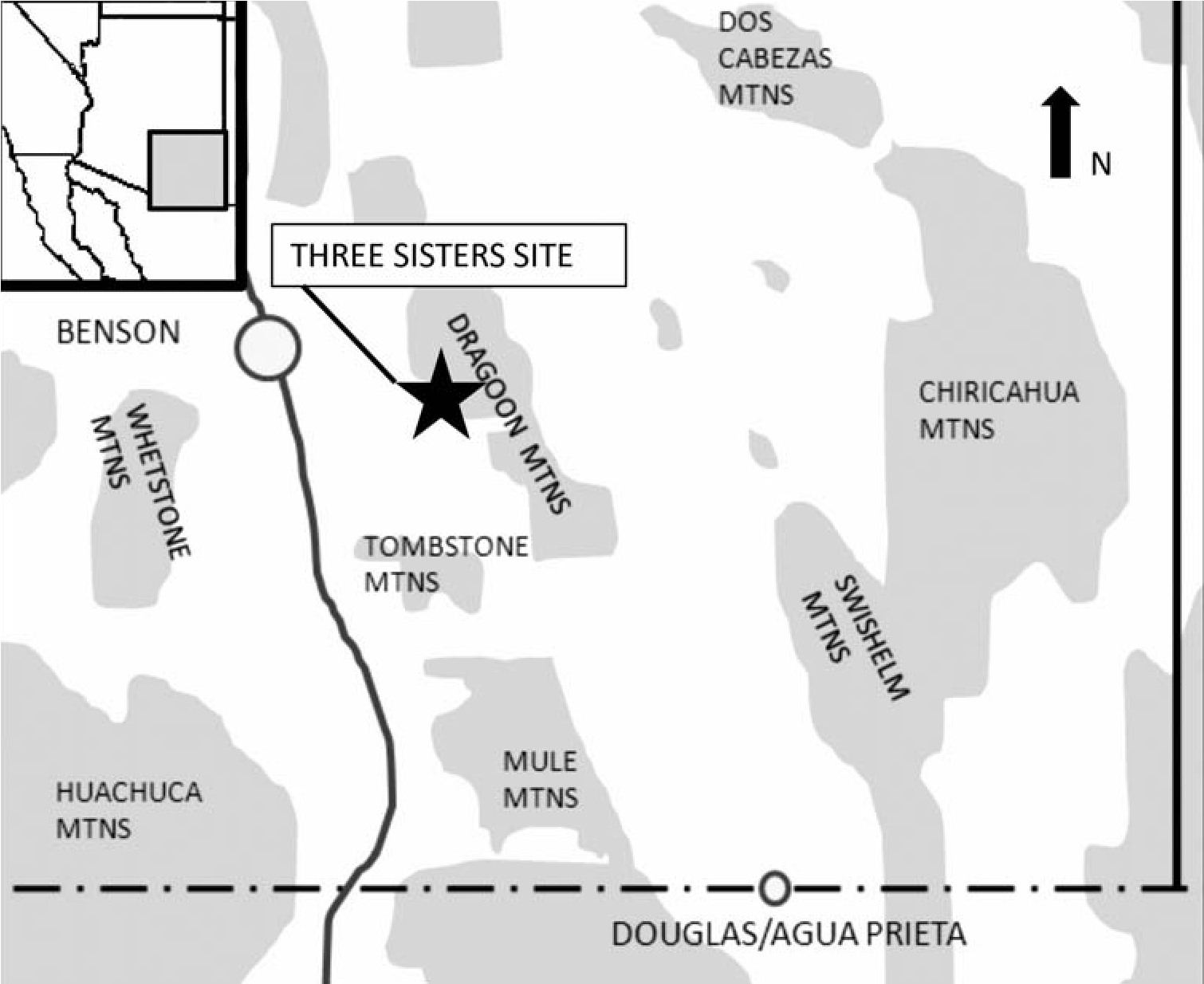

17.1. Area map showing Dragoon Mountains in southern Arizona 223

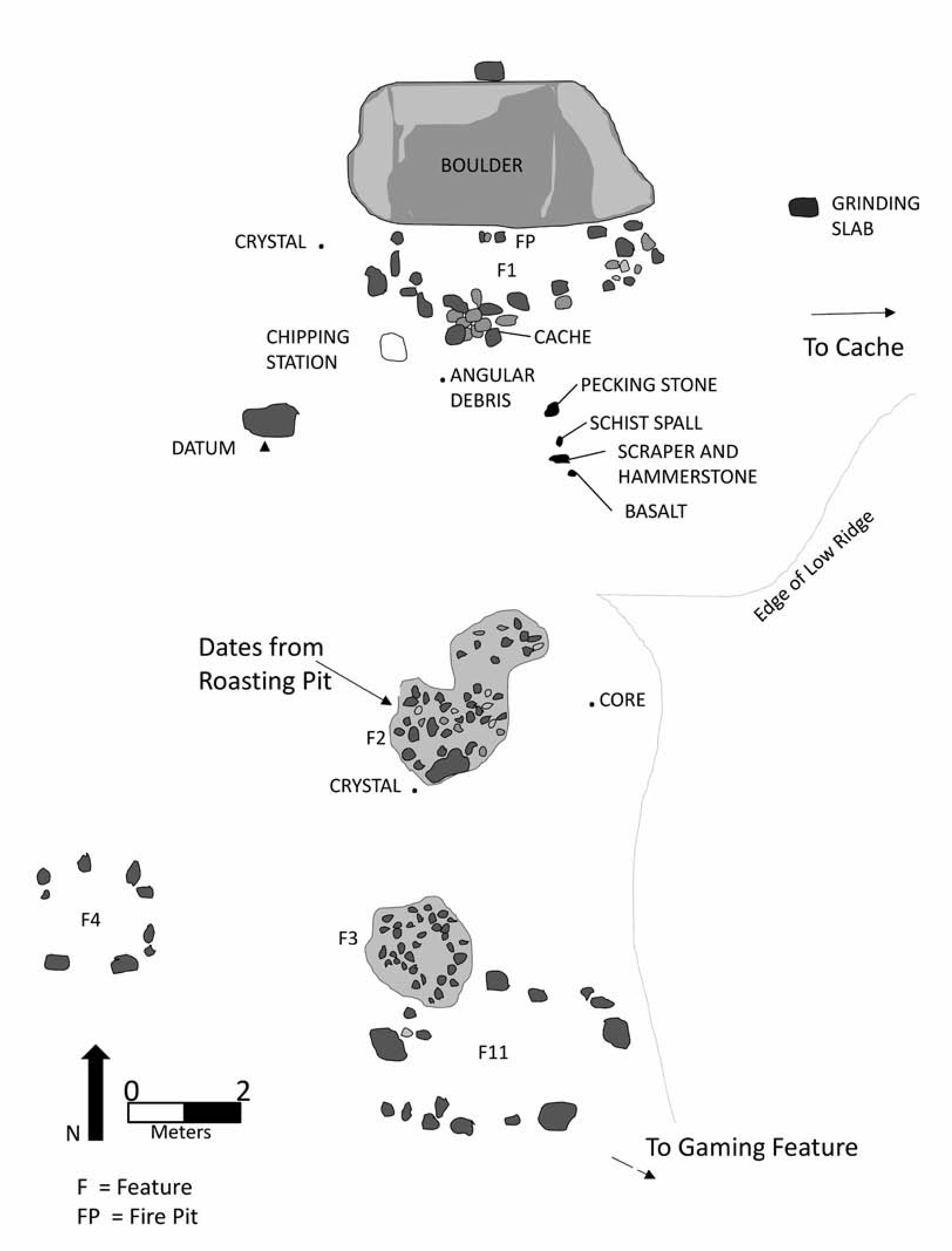

17.2. Locus A, Three Sisters site 224

17.3. Boulder-ring structure, Feature 4 225

17.4. Lean-to, Feature 1 226

17.5. Fire area in lean-to 227

17.6. Roasting pit, Feature 2 227

17.7. Cache in corner of lean-to 228

17.8. Cache in boulder outcrop and manos inside 229

17.9. Grinding slick 230

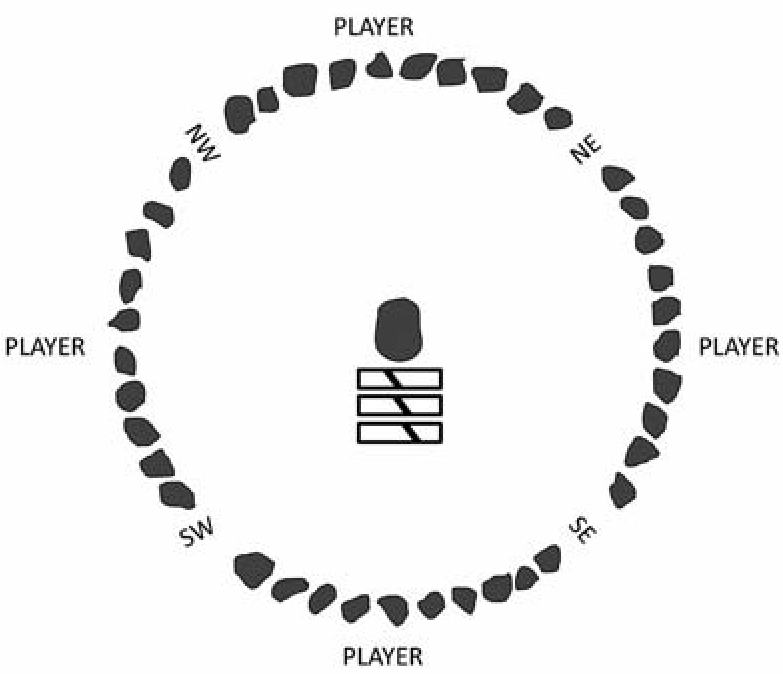

17.10. Possible gaming feature 231

17.11. Idealized drawing of game board 231

17.12. San Carlos Apaches playing stick dice game 232

17.13. Defensive wall at AR 03-0501-600 236

17.14. Cairn at lookout station 238

17.15. Knife from near lookout station 239

18.1. Location of Lake Pleasant in central Arizona 241

18.2. General view of the Lake Pleasant Rockshelter 246

18.3. Landscape view from the rockshelter 246

18.4. Plan map of the Lake Pleasant Rockshelter interior 248

18.5. Yavapai pottery recovered from the Lake Pleasant Rockshelter 251

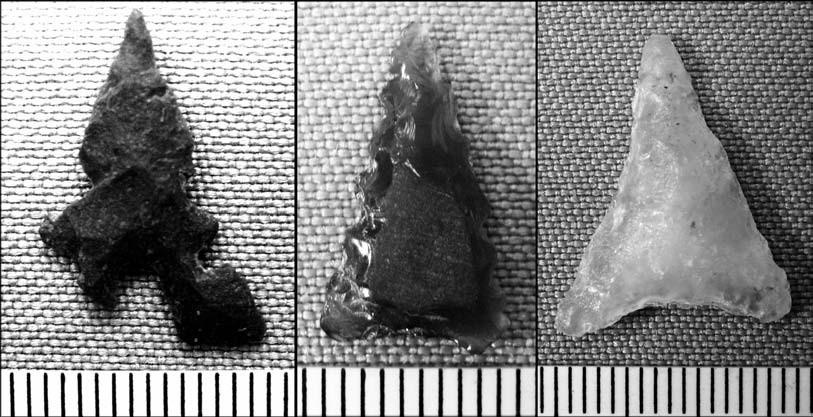

18.6. Hohokam and Pai/Yavapai projectile points recovered from the Lake Pleasant Rockshelter 252

18.7. Lithic tools that registered positive protein reactions 253

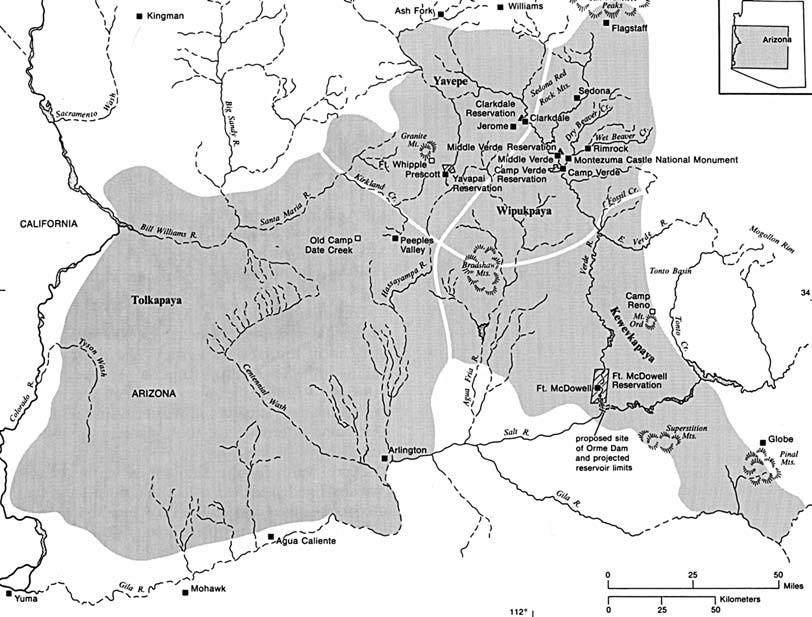

19.1. Ancestral Yavapai territory 257

19.2. Yavapai pottery jars 258

19.3. Yavapai projectile points 259

19.4. Yavapai groundstone tools 260

19.5. Agave knives 262

19.6. Agave roasting pit mounds 263

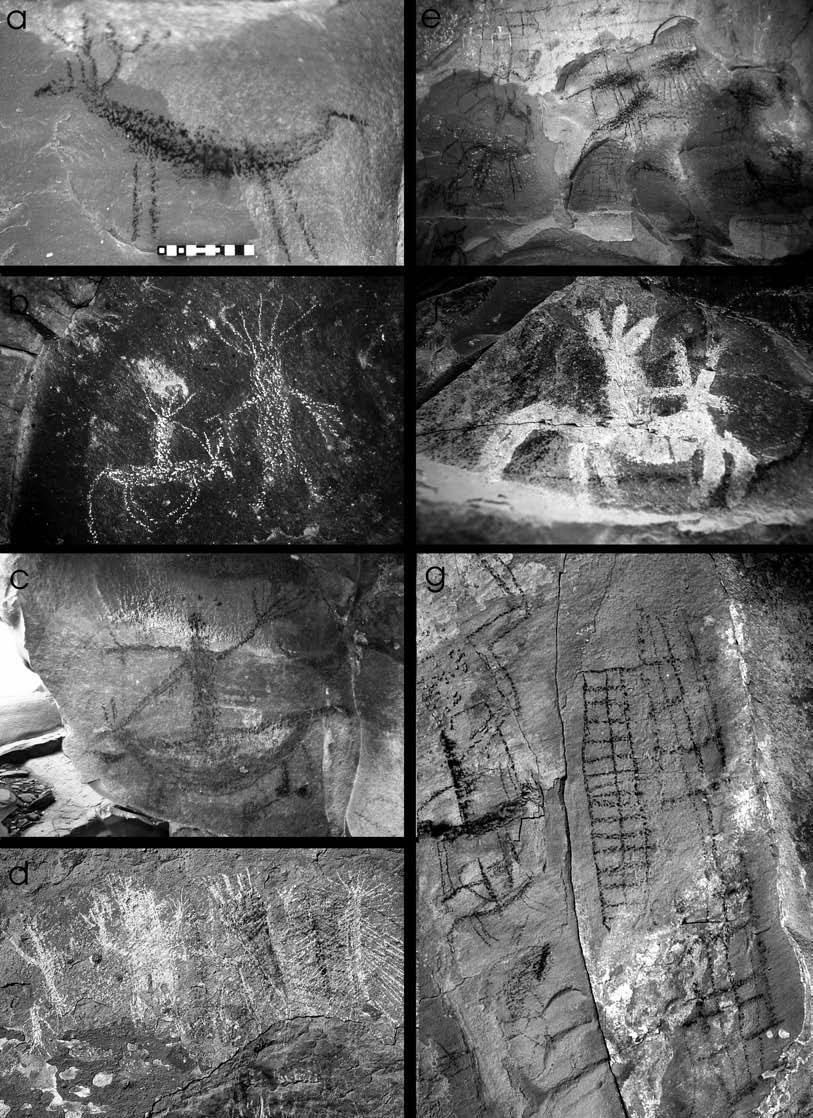

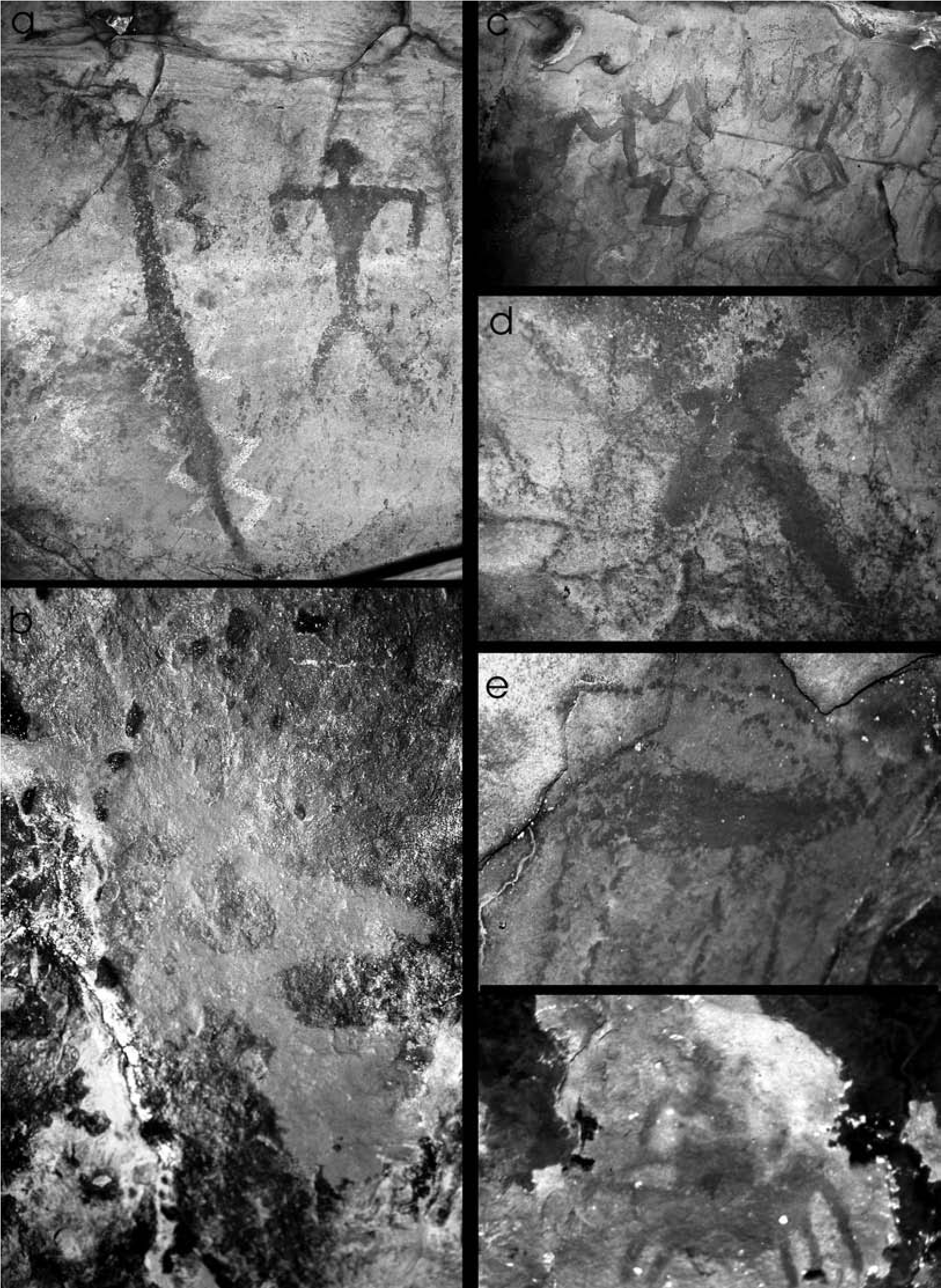

19.7. Wipukpaya Yavapai pictographs 264

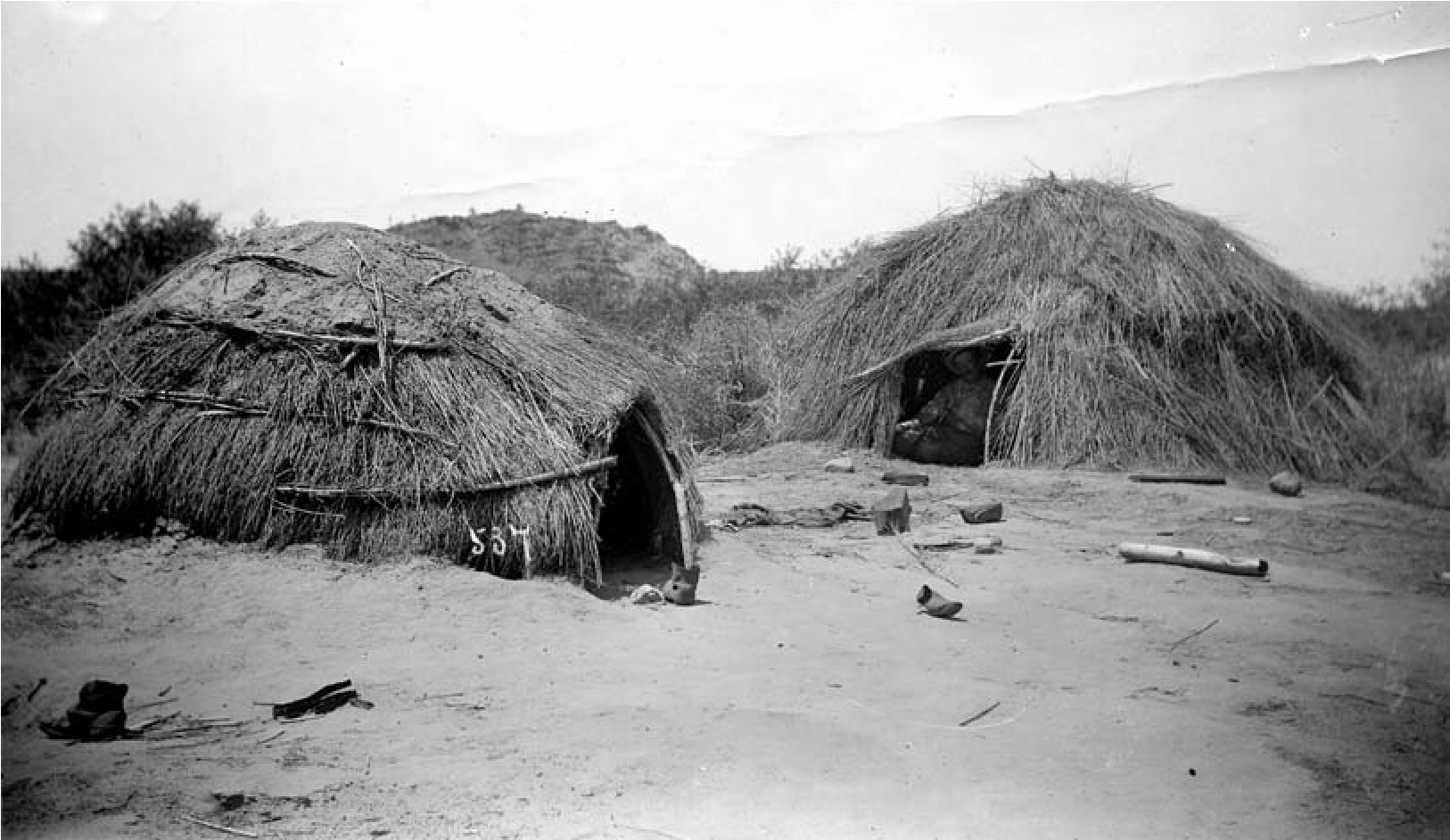

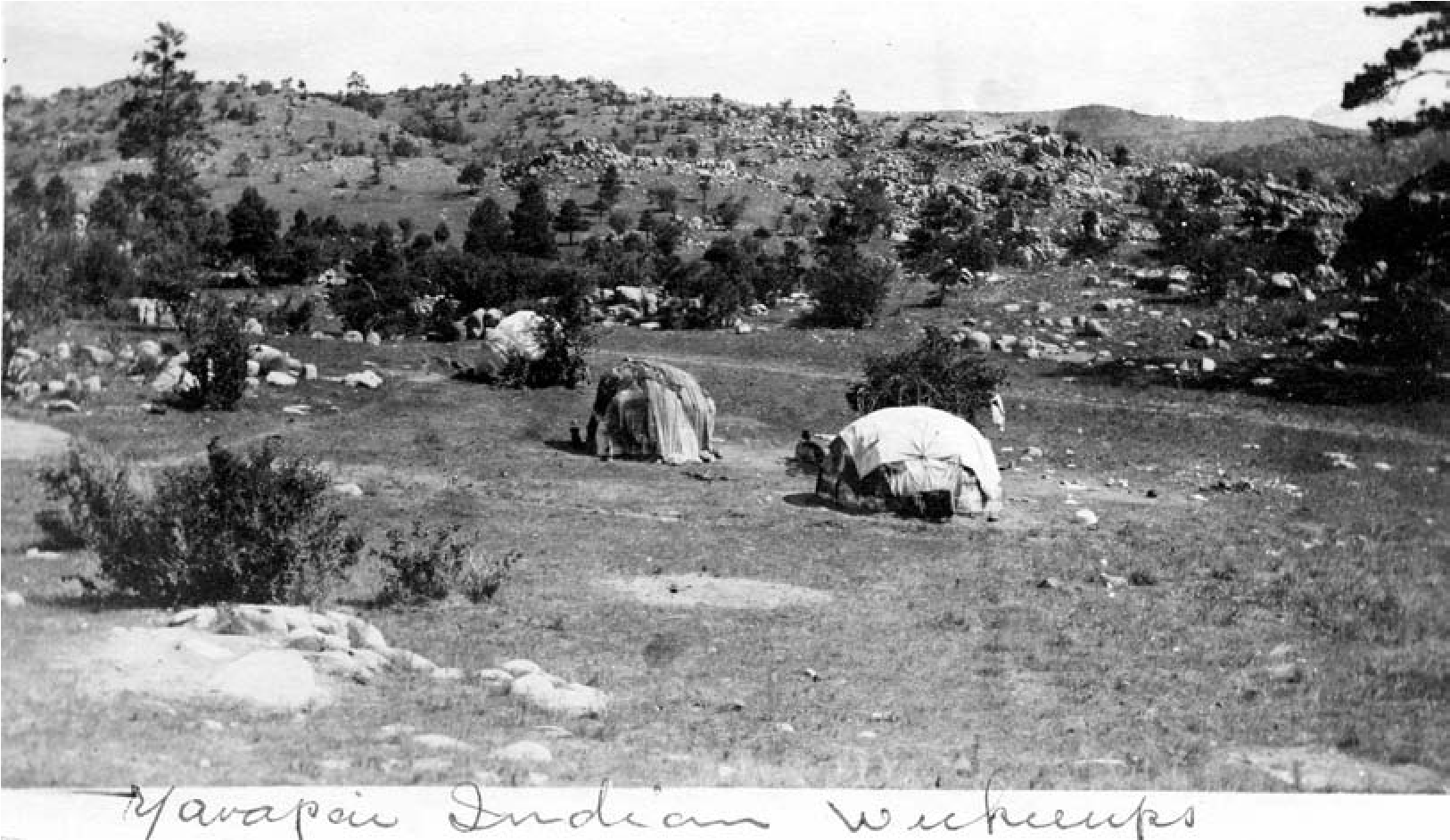

19.8. Yavapai habitation structures 266

19.9. Small u-wa 267

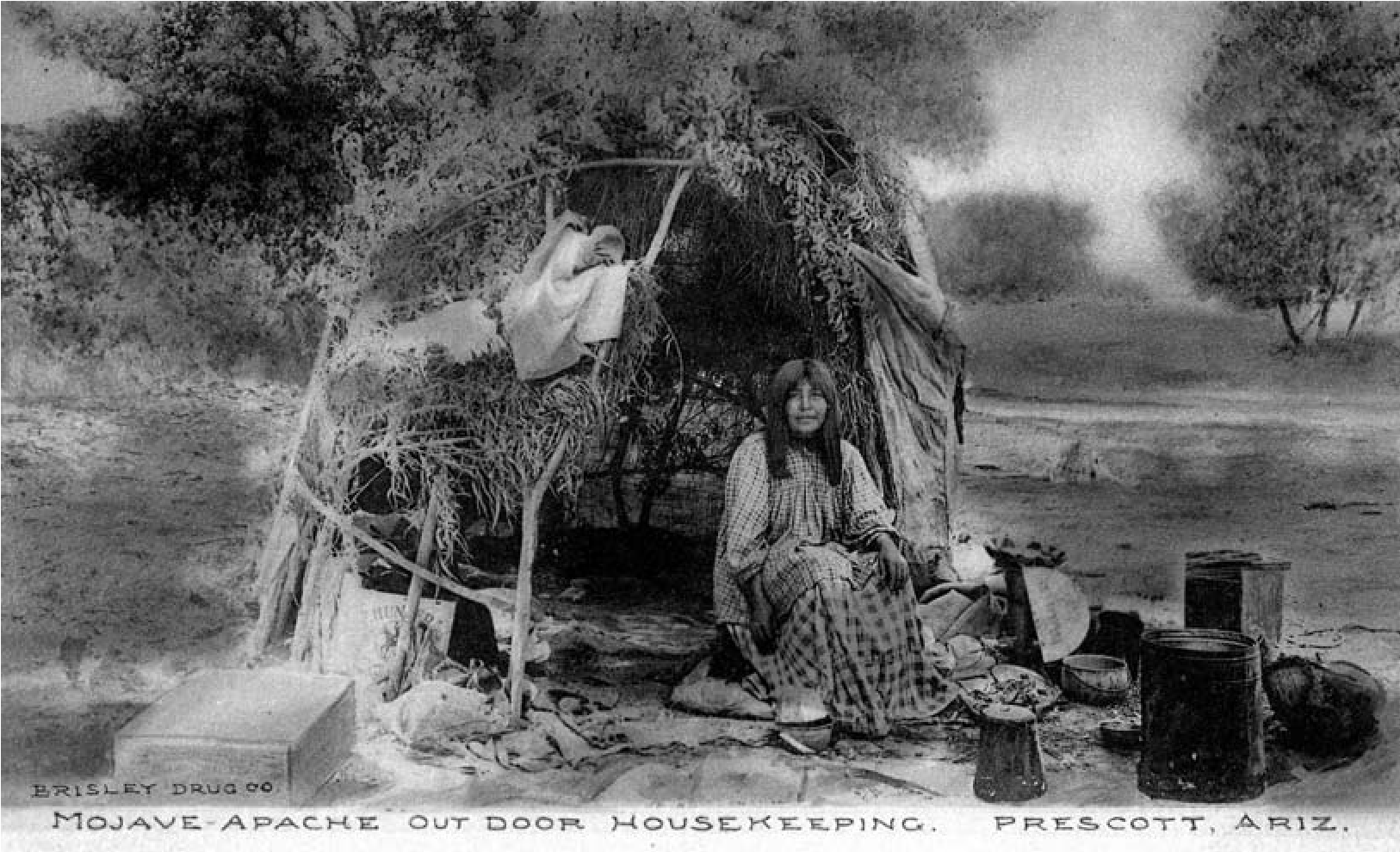

19.10. U-was in Prescott, ca. 1900 268

19.11. Orme School site structures 269

19.12. Structures at AR-03-04-06-745 270

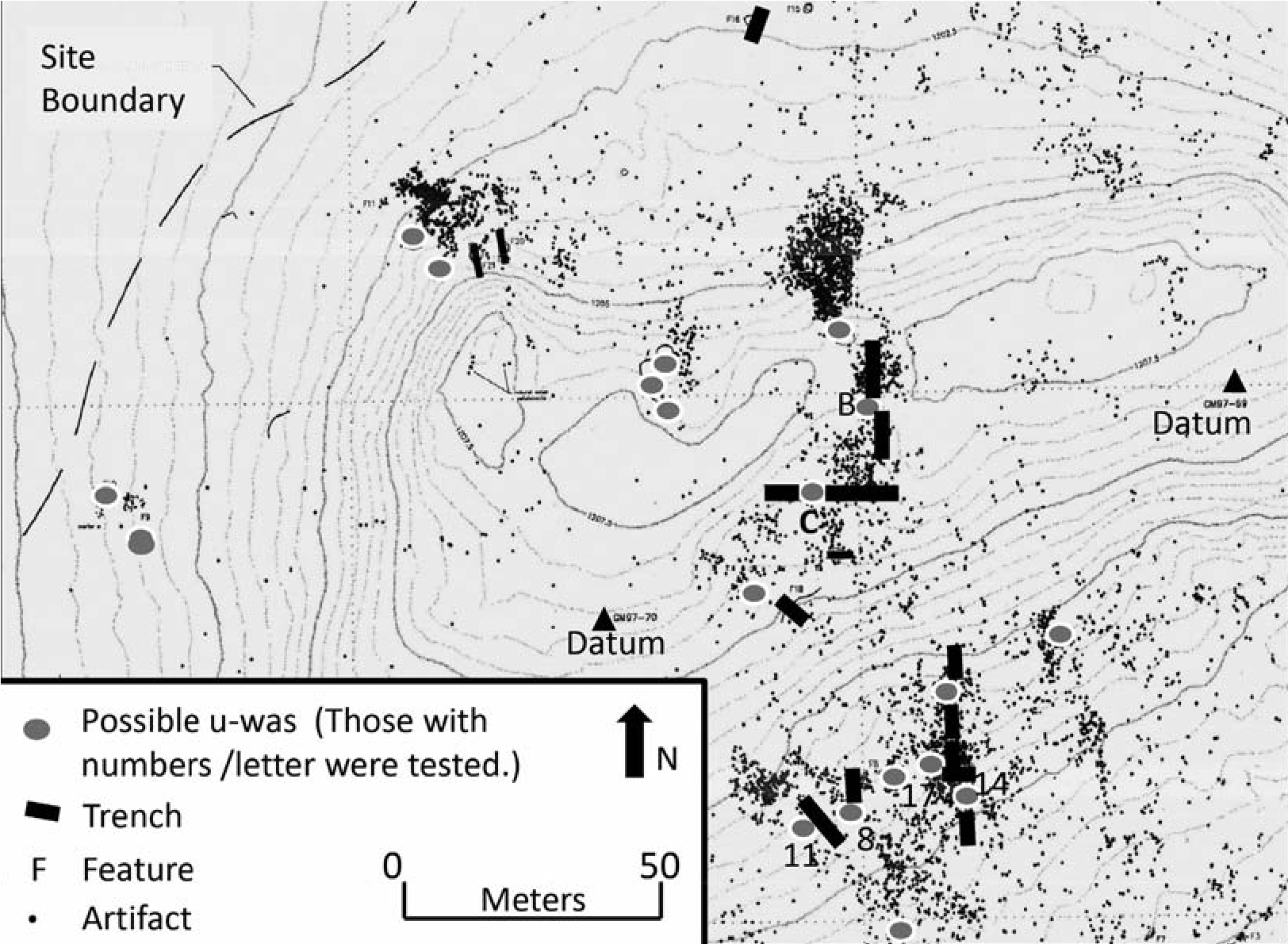

19.13. Map of AR-03-04-06-745 272

19.14. Possible u-was at AR-03-0406-745 273

19.15. Test units at AR-03-04-06-745 274

19.16. Compacted floor surfaces at AR-03-04-06-745 276

19.17. Pictographs attributed to the Dilzhee 278

19.18. “Verde Incised” petroglyphs 279

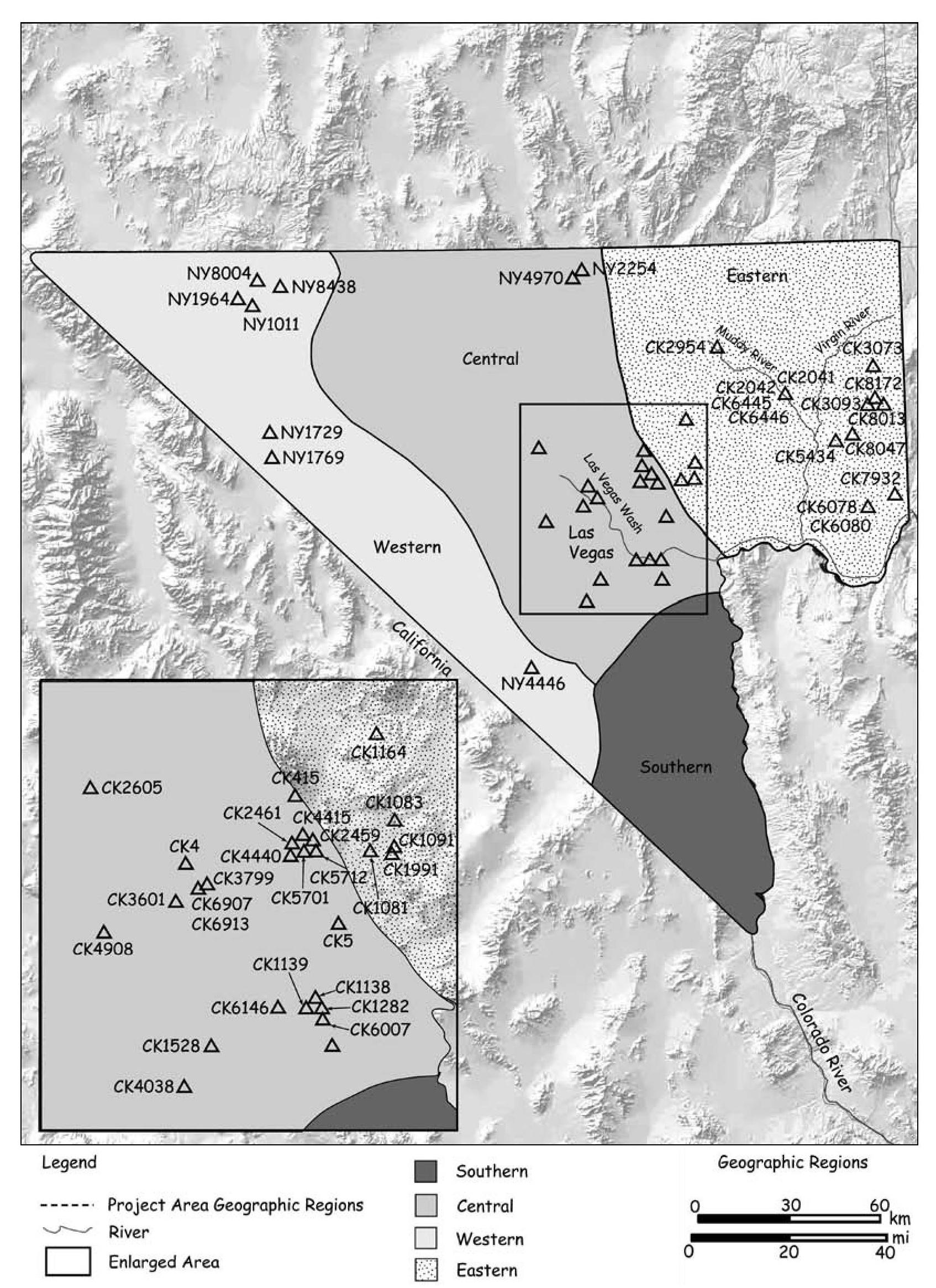

20.1. Geographic regions and radiocarbon- dated Post-Puebloan sites 282

20.2. Southern Nevada Post-Puebloan radiocarbon dates 285

20.3. Fragile-pattern site 286

20.4. Incised stones from the Coyote Springs Rockshelter 298

21.1. Curve of calibration for the postcal ad 1200 interval 307

Tables

2.1. Defensive characteristics among the major villages 24

8.1. Spanish Colonial sites with chipped- stone assemblages 108

9.1. Length/width ratios by K-Means cluster 121

9.2. Correspondence of K-Means cluster pairs to typological categories 122

9.3. Length/width ratios for the typological categories 123

9.4. Discriminant Analysis classification matrix (size-dependent data) 124

9.5. Discriminant Analysis classification matrix (differences between data sets) 125

9.6. Discriminant Analysis classification matrix using reclassified groups 126

13.1. Recent thirteenth-fifteenth-century chronometric dates in the southern Southwest 176

14.1. Game trap dendrochronological dates on the Colorado Plateau 194

15.1. Dendrochronological dating results from the Colorado Wickiup Project 202

15.2. The Baker Model of Ute culture history 210

16.1. Color and diameter of ceramic vessels at 42UN5406 216

17.1. Chronometric dates from the Three Sisters site 233

18.1. Analytic artifact assessment by level at AZ T:4:15o(ASM) 250

20.1. Thermoluminescence dates on pottery from Post-Puebloan components 290

Acknowledgments

This volume has been a long time in coming. Some chapters were solicited specifically for this book to round out its content, but most result from conferences. One chapter dates back to the 1998 Protohistoric conference titled Transition from Prehistory to History, which Pat Beckett and I organized in Albuquerque; the chapter remains pertinent. Others are from a 2006 Mo- gollon Conference session called Transition from Prehistory in the Mogollon Area: An Emphasis on Mobile Groups, while most are from the 2010 New Mexico Archaeological Council Proto-historic conference: Indigenous Mobile Groups of the Protohistoric and Historic Periods. I thank all the participants whose contributions made this book possible and whose patience is commendable. I also thank Dave Snow and John Carpenter for their reviews and appreciate comments from Scott Kwiatkowski with the Yavapai- Prescott Indian Tribe. As always, I am in debt to Reba Rauch, University of Utah Press acquisitions editor, for her open-mindedness regarding this work and her ability to see beyond politics and evaluate the content on its own merit.

1. “Fierce, Barbarous, and Untamed”

Ending Archaeological Silence on Southwestern Mobile Peoples

Deni J. Seymour

When Fray Alonso de Benavides described the indios bárbaros of the 1620s along the road to New Mexico, he referred to them as “people very fierce, barbarous, and untamed” (gente muy feroz, bárbara, y indómita; Ayer 1965:8789; Benavides 1630; Figure 1.1). He also provided his reasoning for this pejorative reference, commenting that they were so barbarous “that they will not even let themselves be talked with,” much less converted or pacified (Ayer 1965:8789; Benavides 1630). Of course, the peoples who embraced the mobile lifeway were not interested in the haughty talk of foreigners. These mobile naciones expressed fierce behavior toward the newcomers to ensure their freedom, for they did not wish to be “tamed.” As part of their conquest rites and initiation of lawful political domination, the Spanish asserted their sovereignty over all Indians and required their peaceful submission to the king. Dire consequences followed if submission was not made or if there was malicious delay (Flint and Flint 2005:616). In the 1512–1573 era Spanish conquistadors read aloud the Requirement (Requerimiento), which was an ultimatum for indigenous peoples they encountered to acknowledge the superiority of Christianity or be warred upon (Seed 1995:70). The Spanish would implore residents they encountered to acknowledge the church, the pope, and the king as superior, and as lord and king, stating that if they didn’t:

I will enter forcefully against you, and I will make war everywhere and however I can, and I will subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and His Majesty, and I will take your wives and children, and I will make them slaves... and I will take your goods, and I will do to you all the evil and damages that a lord may do to vassals who do not obey or receive him... the deaths and damages received from such will be your fault and not that of His Majesty, nor mine, or the gentlemen who came with me. (Seed 1995:69)

In this context it is possible to see that being fierce, barbarous, and untamed meant that these mobile peoples remained unconverted and did not settle down to farm (they are without house, nor any sowing; sin tener casa, ni sementera alguna); they remained, therefore, untamed and untamable. They were indomitable, and part of what made them unconquerable was their lifeway, which led them from hill to hill (mudándose para esto de unos cerros a otros). Because of this way of life, they could not be easily subjugated. These peoples did not wish to be subjects, as testimony in the investigation of the Coronado expedition conveyed: “They were not familiar with his majesty nor did they wish to be his subjects” (Flint 2002:353).[1] They fiercely defended their way of life and their families, and when arrogant Spaniards read the Requerimiento, stating that native women and children would be enslaved if they did not submit to the king’s authority, the fierce defenders may not have understood the words but as time went on they began to comprehend the intent. These fierce, barbarous, and untamed ones are any of a number of peoples who did not submit, nor did they recognize the legitimacy of this asserted domination. When they knelt on bended knees, begging for missionaries and baptism, it was often a ruse to get the Spanish to accompany them through enemy territory, for they knew how easily the Spanish could be fooled (Hodge i9iob:26i; Kelley 1955:984). These are the people who moved around the landscape not only to pursue game (they live off what they catch; viven de lo que cachan) but to evade the “yoke and obedience of the Church and His Majesty” avoiding the deaths and injuries that, although inflicted by the Spanish, would be their fault, according to the Requerimiento. While the Spanish did “all the evil and damages that a lord may do” these mobile peoples melted into the landscape, living as they chose.

It was not always this way. Many of the same groups that Benavides and others described as fierce were initially friendly and welcoming. Members of these small mobile groups hid from the first explorers, as noted by Hernán Gallegos of the Chamuscado-Rodríguez expedition: “On entering the mountainous territory, we saw an Indian brave and two inhabited huts. Taking our horses and arms we went in that direction and discovered many people, who fled toward the mountains when they saw us approaching” (Hammond and Rey 1966:80–81). Others welcomed the Spaniards and helped them along the way. The Tanpachoas, thought to be the people later referenced as the Mansos, provided the 1582–1583 Espejo expedition with “a large quantity of mesquite, maize, and fish” during their seven-day visit (Hammond and Rey 1929:69). As the Yavapai point out today, their ancestors were noted by the same expedition as being initially friendly to the Europeans: “In this locality we found many peaceful, rustic people who received us well” (Hammond and Rey 1929:107). Regional hospitality dictated that locals share their food with visitors and shelter them from harm. Others were looking for new allies in the already war-torn region. But as Europeans imposed their will on the locals, the locals changed their approaches to these newcomers. Their responses were in many instances dictated by how accessible they were to the Spaniards and how easily they could move to more remote locations.

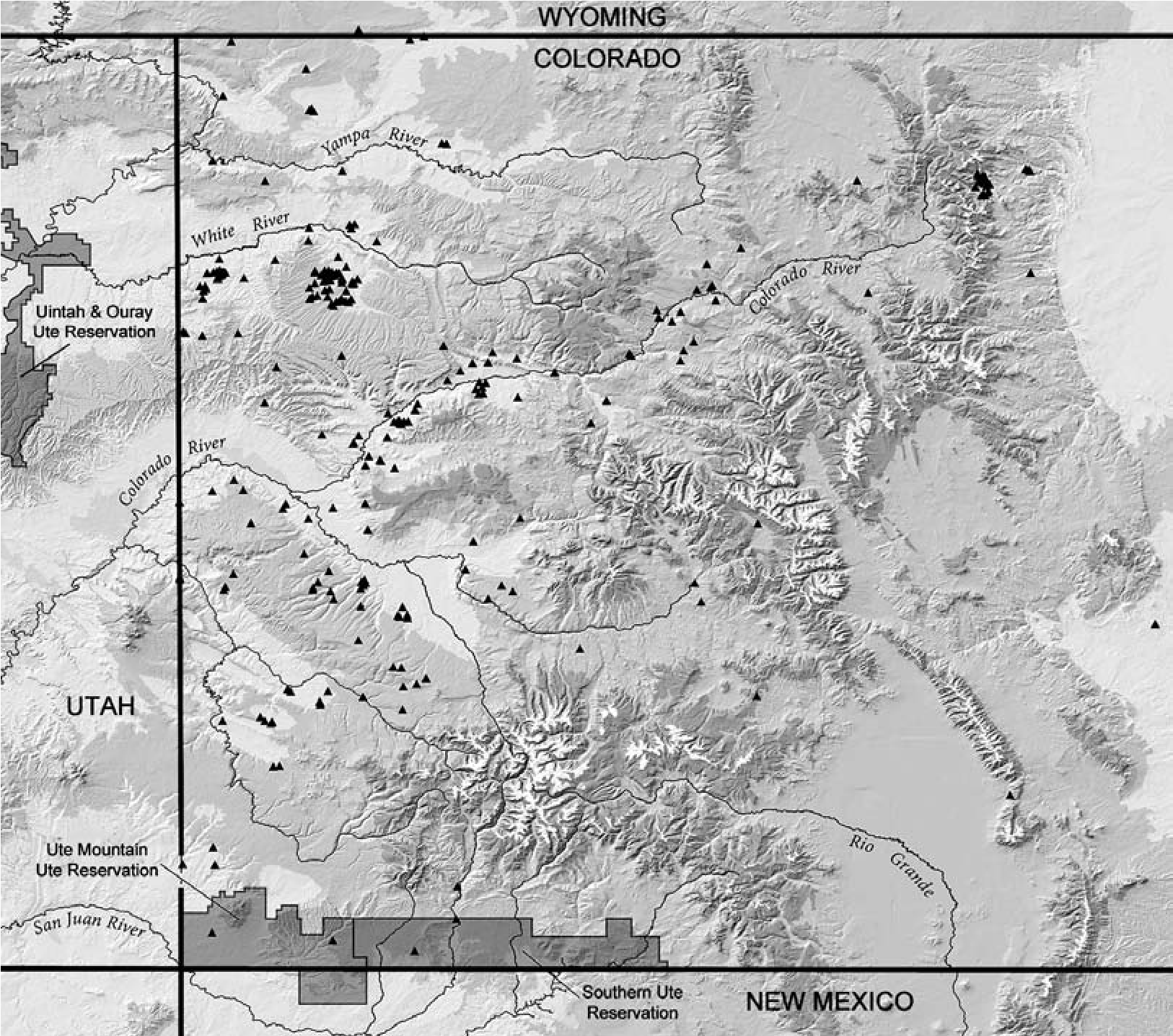

But the chapters in this book are not about the Spaniards, or even about native people’s interactions with the Spaniards. This book is about The People themselves, in their own right, and the archaeology of these mobile people of the Terminal Prehistoric and Native American Historic periods, collectively referred to as the Protohistoric (Figure 1.2).[2]

The People, on the Periphery

Most indigenous groups refer to themselves as The People, the implication being that all those surrounding, even close neighbors, are “others,” less than people.[3] The use of these titles that self-reference as The People (those of relevance) remains true for the vast majority of groups that refer to themselves in traditional ways. The historic and sometimes the current name used to identify a tribe is often not the traditional name it uses for itself. This holds true for the historic Pima and Papago, now known as the Oodham; the Ute, who call themselves Nuutsiu or Nuchu (or a variation on this term, depending on the band); and the Yavapai, who call themselves Pai. The Chiricahua Apache refer to themselves as Ndeh, the Mescalero say Nde, and other Apaches and Athabascan-speaking groups call themselves Dine, Tinde, or Inde, all dialectical variations meaning The People. Each saw themselves as central in their world, their self-reference as The People conveying their sense of belonging in a land fashioned specifically for them by the Creator. Each of these groups is discussed in this book not as isolated entities, as the only real people, but as a mosaic of peoples peripheral in many ways to the better-known Puebloan groups and other settled peoples of the Historic and Late Prehistoric periods.

The peoples discussed in this book are mostly those that have remained at the periphery of Southwestern archaeological investigation. Until recently, little was known about the archaeological signatures of these groups and so they were not available for study, other than through history, oral history, and ethnography. Mystery surrounded the presence of these mobile groups, owing to an insular focus on farming communities. Such limited focus was justified by the absence of evidence and by the much richer material records of many of the farmers, whose decorated vessels and sizable communities with thick midden deposits have attracted archaeological researchers since the beginning of a formally organized discipline (Chapter 13). Early researchers engaged discussion of some of these peripheral peoples by suggesting they attacked the settled farmers and were therefore responsible for key organizational changes late in prehistory (Kidder 1932; Rouse 1958). Chapters 2 and 3 in this book discuss violence, but initially these groups remained on the outside of scholarly inquiry, rarely the focus of study themselves. Even visiting mobile peoples who encamped at the periphery of the pueblos have remained invisible until recently (Chapter 4; Seymour 2015a).

Many of these groups are also at the geographic periphery of the Southwest, such as the Numic-speaking Ute and Paiute, and the Pa- tayan, all of whom were at the northern edge, and the Jumano, who occupied the far eastern edge. Many Apachean groups were in the center but occupied niches that were used by their settled neighbors only tangentially or in narrowly prescribed ways. Other Apachean groups moved throughout a vast territory, usually circumventing settled populations but preying on them when needed. Some of these peripheral groups, such as the Sobaipuri Oodham and other Akimel Oodham, used the same landscapes as their predecessors and practiced a farming way of life, but their material signature is so light that study of their past is challenging and thus they have been marginal to mainstream study (Chapter 13). These are the lesser-known Protohistoric groups of the North American Southwest, who were also many of the peoples encountered by the first Europeans.

Defining a Period of Study

Protohistoric is typically used to denote a vague, poorly defined period in the American Southwest. More often than not it is defined with reference to preceding and succeeding periods.[4] Mostly, it carries with it the assumption that we do not know when or how the grand adaptations of a ceramic-titivated prehistory ended and new or derivative ones formed. It is a period of many transformations, and this problem of how the primary prehistoric manifestations became those of the Historic period remains a key question. In this sense Protohistoric defines a negative, a void, and an absence of knowledge and evidence. For this reason and to set the stage, the book includes two chapters on the Late Prehistoric Jornada Mogollon (Chapter 2) and Hohokam (Chapter 12), along with one that discusses the interaction of existing peoples and newcomers (Chapter 13). These provide a sense of what was occurring locally before and during key turns of events that sent them headlong into the Protohistoric.

Most people think of the Protohistoric as a transitional period between the Prehistoric and Historic periods. Customarily in the southern Southwest this period lies between ad 1450 and 1700, although the temporal boundaries are imprecise. Yet even in this region the dates used to denote the Protohistoric period vary widely (Di Peso 1953; Gilpin and Phillips 1998; Ravesloot and Whittlesey 1987; Riley 1987; Seymour 2011a; Wilcox and Masse 1981). One reason is that history begins at different times in different regions. In northern New Mexico, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s quest for Cibola in the mid-sixteenth century is relevant, while directly to the south the 1581 Rio Grande crossing by Fray Agustín Rodríguez and military escort and expedition leader Captain Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado is seen as the pertinent event. In Utah, Fathers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante established historic contact in 1776, and in 1706 Juan de Ulibarri claimed the territory of Colorado.

Moreover, the actual act of history that spurs the initiation of the Historic period varies among researchers as they choose which contact event to emphasize. Most treatments are imprecise as to when the Historic period begins and whether or not this apparent watershed event depicts the time of continuous occupation or the first recorded contact with Europeans. Initial (documented) contact tends to occur much earlier than sustained contact, but many, for example in Arizona, do not consider history beginning until there is a sustained presence. Before this, numerous undocumented Spaniards and Indians from the south traveled north to obtain slaves and other items worthy of illegal import from the Pueblos and nomadic tribes that occupied this land uncharted by Europeans. Depending on perspective, history may begin in southern Arizona in 1539 with the arrival of Marcos de Niza or, conversely, in 1691 with Father Eusebio Francisco Kino in the southern portion of the state and in 1629 at the ancestral Hopi village of Awatovi on Antelope Mesa in northern Arizona. One implication of this is that the conditions and nature of contact vary widely.

Differences in contact events between drainages and in geographic zones may be pronounced as well. Groups living along major travel corridors, such as rivers and key trails through the mountains, would have encountered many more varied people and much earlier than those who lived in the hinterlands. All of these issues are relevant, yet one important aspect of the Protohistoric concept is that the initial encounter with Europeans was an event of a very different nature and magnitude for local indigenous populations than the encounter with other natives. I am confident that it is time to reevaluate this assumption.

Additionally, our view of when history is initiated varies among groups. For example, the Oodham are generally viewed as being encountered by Niza in 1539, but we think of the Apache as not being contacted until the late 1500s. This apparent absence of direct encounter has led many to continue to argue that Athabascan- speakers, the Dene, were not in the region until long after Spanish presence, despite strong evidence to the contrary (Seymour 2012a, 2012b, 2013a; Chapter 17). Yet even though the ancestral Apache may not have been encountered by the Spanish until much later, it is legitimate to question if and how they might have been affected by European presence much earlier. Disease is one vector by which they might have been impacted, but their interactions with other groups were likely affected as well. Their ability to trade was influenced by the new goods that became available to the Oodham and Pueblo groups. Evaluation of the costs and benefits for raiding would have been altered. New alliances likely created imbalances. Contact with one group could no doubt have profound ripple effects throughout a wider region, affecting groups that did not experience direct encounter for many decades.

People in different geographic areas and cultures experienced this period in unique ways. Because of this geographic component, archaeologists have tended to conflate ethnicity with chronology (Seymour 201^:230–231; Ravesloot and Whittlesey 1987:83). Although such equations originate with archaeologists who study sedentary farmers perceived as residing within distinct territories, the problems with this imprecision become visible among groups with overlapping territories and intertwined histories. In this conception, one geographic area does not equal just one culture group. Conversely, even the larger tribal entities of today are composed of many that were previously distinct groups. The Oodham along the Gila and Salt rivers experienced this period very differently than the Sobaipuri Oodham of the Santa Cruz and San Pedro rivers, just as the more mobile Soba and Tohono Oodham did. Consequently it is expected that there were substantial differences in local or regional processes, specific events of contact, and types and amounts of evidence available. This means that our studies will be most effective when focused on a specific group within a specific geographic area. At the same time, however, we should not ignore adjacent areas because the period cannot be understood without a much broader geographic focus. The historic groupings so important in ethnographic accounts were not necessarily groupings visible archaeologically many centuries earlier.

As data accumulate, our understanding increases, yet Protohistoric temporal boundaries have been based on guesses and lack of data. These vague and varying notions of the Protohistoric period result largely from a lack of archaeological sites and other forms of evidence on which to base assessments, including past uncertainty in chronometric placement of sites. The lack of dates has left a significant period of time unaccounted for between the end of the prehistoric era and the Spanish entrada.

The lack of a coherent and organized body of archaeological evidence has been largely responsible for the widespread use of the term Protohistoric. This catchall period defines a nebulous time when the classificatory rules of the prehistoric periods do not apply, when boundaries change, and when new groups form and migrate in. It is during this time—as much as if not more than others—that assumptions must be examined, theory devised, and methodologies adjusted.

One important part of the problem is that prehistoric periods are based on changes we can see in the archaeological record, while the initiation of the Historic period is marked by a pen stroke, generally with no commensurate alterations visible in the regional or local archaeological record. Even when historical figures proclaimed a fundamental alteration in local practices, in reality it is often many decades before transformations appear in the archaeological record, suggesting that actual practice did not conform to these politically motivated claims (Seymour 20iia:288–289). In other instances, critically important happenings with long-term effects were either not mentioned or purposefully denied (Seymour 2009a, 20iia:23i).

These labels (prehistoric Classic period vs. Protohistoric) are not comparable or compatible classificatory criteria. Although “Protohistoric” can be a helpful term to denote a period of study, it is generally more problematic than useful owing to its imprecision. Conceptually, the term “Protohistoric” makes sense when nothing is known for a block of time and is equivalent to Haury’s (1975:18–21) term “dark age” to reference unknown cultural patterns. Yet as we learn more about this wedge of time, more precise labels seem appropriate because of the diversity of processes occurring and the nature of transformations taking place, which can be seen as a consequence of their impacts on the material and spatial record. Throughout much of this region the Terminal Prehistoric gives way to the Expedition period, and then period and phase labels proliferate to reflect local developments visible in the archaeological record and in historic documents (see Seymour 201^:230–232). “Protohistoric” is still most useful to denote the vague, general, and unknown. As I have noted, the term “should signal to the reader ambiguity in understanding, doubt in accuracy, or imprecision in content.” Nonetheless, it can be helpful as a shorthand reference that acknowledges the substantial changes under way in cultural systems, while allowing temporal considerations and details to be set aside while other issues are addressed (Seymour 201^:230).

Earlier Than Expected

Assumptions of a shallow time depth for many of the groups that define the Native American Historic period has influenced the search for and detection of relevant evidence. The postulated late arrival of many groups has prohibited recognition of earlier-than-expected evidence, which in turn prohibits investigation of the processes surrounding the initiation of the sometimes profound differences manifest clearly a century or two later. Hardened conceptual schemes allow researchers to distrust and dismiss carefully collected chronometric dates that fall before the arbitrary 1450 date (Chapters 7, 13, 16, 17, 19, and 20). This temporal margin is perceived as real and even meaningful, and so it is customary to argue away dates relating to late components that occur on sites thought to be older, because, after all, these dates are presented as probabilities, always with some degree of uncertainty. Similarly, it is common practice to assume that dates in the ad 1200s and 1300s are reflective of the underlying cultural manifestations rather than evidence of new groups. Chapters in this book suggest it is time to reconsider the relevance of late dates on aceramic and multicomponent sites and to remain open to the possibility of nonstandard assumptions about episodes of site use.

A significant number of chronometric dates have been obtained relatively recently from numerous intensively studied archaeological sites. In many instances, these sites were used by the historically referenced groups encountered by the first Europeans even though they date to long before European presence. Earlier-than-expected dates associated with distinctive material culture indicate that fundamental changes in the social landscape and in predominant lifeways occurred over a vast geographic area. Chronometric dates indicate that the Oodham were present perhaps as early as the ad 1200s and their mobile neighbors the Jano, Jocome, Manso, and Suma at least as early as the 1400s (see Chapters 7, 13, 17), and probably even as early as the ad 1200s or 1300s (Seymour 2016). Yavapai and Ute sites are also presenting early dates (ad 1300s), as are Great Basin sites (Chapters 16, 19, and 20).

A growing body of evidence regarding early ancestral Apache presence in the southern Southwest provides chronometric dates in direct association with Apachean material culture in the ad 1300s (Seymour 2008a, 2013a). One of the first ancestral Apache sites found that dated to this early period (discovered in 1994) was the small encampment referred to as Three Sisters; although not published until now owing to its controversial nature (Chapter 17), this site has been foundational for our thinking about an early ancestral Apache presence in Arizona. Its character is consistent with later ethnographic data, indicating stability and temporal depth in some aspects of Apachean lifeways.

Moreover, this site and a Yavapai one discussed by Stokes and Tactikos (Chapter 18) demonstrate that mobile groups may stay only a short time but tend to return repeatedly to favored locations, creating persistent places, places of intervallic use (Seymour 2009b). This understanding of encampment reuse allows for effective chronometric sampling of features (Chapter 17). Other aspects of mobile group behavior seemingly account for the frequency of late dates obtained by Roberts in the Pai area (Chapter 20). Incredibly, 35 percent of the accumulated dates in southern Nevada fall into the target period, which is partially related to the greater number of sites that mobile groups produce as a result of moving around. Also, however, sites with ceramics and other artifacts considered diagnostic do not require the added expense of chronometric sampling, which also likely contributes to the skewed numbers.

The problem of lack of data and dates for this period has been exacerbated by the fluctuations in carbon 14 and cyclic oscillations that result in multiple intercepts and excessively long age estimates. Yet use of a combination of luminescence and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating has exponentially increased the number of chronometric dates available for the post-1600 period. These results indicate that “Protohistoric” adaptations, which begin in the AD 1200s and 1300s, or even before, overlap with prehistoric cultures in the Terminal Prehistoric period. This inability to temporally partition these data sets explains in part why these Protohistoric groups have been so difficult to define (Seymour 2008a, 2008b, 2010a, 2011a, 2011b, 2013a). Recognition that these groups were present much earlier means that we cannot use ad 1450 as a point of departure for investigation. There is no great divide at ad 1450 that separates distinctive adaptations but rather there is an overlap between extant prehistoric cultural entities and those present in the Historic period, even when new groups entered the region (Chapter 13). As shown in Chapter 20, use of the “Post-Puebloan” label, like the term “Protohistoric,” often keeps us from seeing or accepting this overlapping presence and examining the processes when they actually begin.

The Terminal Prehistoric is when new groups and new organizational systems first appear and when changes in existing ones are most visible. Previous focus on the transition to history has masked the timing and impetus behind these transformations. Consequently the explanations for change adopted derive inappropriately from processes that were not relevant until many decades or even centuries later. Much happened in the 100-300-year period that lies between the end of prehistory and the beginning of history, and when the Historic period arrived, these altered lifeways were already well entrenched. Many of these historical groups changed substantially through time as well, which means we must track their archaeological signatures temporally and spatially while recognizing the basis for changes in landscape use, feature characteristics, and artifact types (Seymour 2012a). In many cases these long-established practices provide a basis for the later actions of indigenous peoples when confronted with European practices and conventions.

Dispensing with the Notion of a Hiatus

Recognizing depth of occupation has not been an issue for Puebloan groups, for which continuity is assumed owing to the distinctiveness and high visibility of their material culture. But for non-Puebloan groups the assumption of a late arrival has contributed to the postulation of a temporal hiatus and a substantial break in material culture between prehistory and history. This notion of an occupational hiatus after about ad 1450 remains a dominant theme in the Southwest and accounts for the bracketing of the Protohistoric period between ad 1450 and 1700 in the southern Southwest. It was thought that when the prehistoric cultures in the southern Southwest “ended,” there was an occupational hiatus before the historic groups, such as Apache, Oodham, Jano, Suma, and their neighbors, moved in. This notion originates in a long intellectual tradition, most notably advanced by Haury (1975, 1985), who proposed a hiatus in the Forestdale Valley and also in the Papagueria (now the Tohono Oodham reservation).

This occupational model has lent credence to the idea of the dispersal of the Hohokam and the emptying of the central basins of Arizona. The term “Hohokam,” referring to prehistoric irrigation farmers, originates from the Oodham word Huhugam, meaning “something that is all used up” or finished, from huhug, “to perish, disappear” (Bahr 2009:1). The archaeological distinction between the Late Prehistoric and Historic Native American cultures reinforced this idea, especially in the absence of evidence for the intervening period. Models of a massive die-out or out-migration have remained viable because of lack of knowledge, which has been equated to lack of presence. Unfortunately, positing a hiatus has allowed archaeologists to abrogate the responsibility of explaining this substantial change (Chapters 12 and 13). Migration into an empty niche is a much easier scenario than entry into a contested terrain where complex social processes, such as conflict, must be addressed. Assumptions regarding the occurrence of a hiatus dispense with the need to engage in multifaceted arguments about how the end occurred and new beginnings came about. With the addition of new data, however, simple unicausal environmental or migration-related explanations are no longer warranted.

Some have recognized the unlikely nature of the empty niche scenario and have proposed a reorganization of existing systems rather than a disappearance. Southeastern New Mexico models have accommodated this notion, suggesting that groups went back and forth from stationary village farming to a more mobile hunting adaptation (Hodge 1910^257–258; Jelinek 1967; Speth and Staro 2012, 2013; Sebastian and Larralde 1989; Speth, Chapter 3 this volume; Beckett, Chapter 5 this volume). In southern Arizona similar models are lacking, and some continue to argue for the filling of an empty niche. In this scenario there is no conflict, no resistance, no accommodation, and so only a single process requires consideration: the recognition and timing of migrated groups. There is no perceived need to consider processes for the Terminal Prehistoric that approximate those of contact with Europeans in the Historic period. We have yet to consider the material and spatial consequences when organizations disintegrate and form smaller, independent, self-interested groups. It is reasonable to infer that as the Jornada Mogollon faced stress, their way of life transformed into that characterized by the Ju- mano and others, as Beckett suggests (Chapter 5; Jelinek 1967; Sebastian and Larralde 1989). It is equally important to ask whether there was always a mobile element that has remained archaeologically “invisible” If so, how were these people impacted when newcomers arrived?

When the Pueblo world is viewed as the center of the social universe, it may be difficult to see that, in the Terminal Prehistoric period at least, Pueblos were small nodes of concentrated populations in a sea of mobile people rather than exclusive occupiers within a vast and uncontested Pueblo domain (Seymour 2015a; Chapters 4 and 13). Our ability to see these mobile peoples provides a glimpse into their widespread presence, hinting at the need to consider this element when we discuss social processes. At the same time, in Chapter 3 Speth discusses Plains margin hunters who occupied pueblos, a difference that highlights the conceptual contrast between highly mobile groups and seasonally mobile stationary groups.

The processes under way at this time were complex, involving political and economic reorganization and migration of new peoples. Each area likely experienced this transition differently, and so archaeological evidence is not expected to be consistent on a more widespread basis (Seymour 2011a). Thus while there may have been a hiatus in the Forestdale Valley (still to be demonstrated), people were, in fact, present in nearby areas (Seymour 2012b). As Wilson (1984:44) remarked regarding the Apaches: “The realization that an Indian group could enjoy almost unlimited use of a territory for roughly 300 years and yet leave few traces upon the landscape should sober archaeologists as to the imprecision of their customary tools for interpretation.” Clearly our tools of interpretation require improvement, but the techniques of recognition are also in need of refinement. Now we have evidence to suggest that the Apache had “free reign” for roughly 600 years. New data presented in this book and elsewhere demonstrate that there was no occupational hiatus, nor were the Apache alone.

Reorienting the Protohistoric Problem

One important and misleading aspect of the Protohistoric conceptualization is that initial encounter with Europeans was the seminal event for indigenous groups. Just as indigenous people have seen themselves as The People, historians have viewed that which was written and those initiating the record of encounter as the legitimate focus of study (Rubertone 2000:428). Along with this it has been presumed that our first window into the Terra Incognita was eventful for all, and that this encounter was an event of a very different magnitude than encounter with contemporary natives. New data suggest that it is time to reevaluate this assumption, in part because indigenous people had their own histories with equally varied agendas that played a role in steering the course of events. They were not passive, helpless, and ignorant recipients of outside offerings and threats. No doubt many were superstitious, but so were the Europeans of the time. The first encounters were often violent and intrusive, and indigenous groups were impacted when, for example, Esteban and nearly 200 So- baipuri were killed at Cibola for trespassing (e.g., Flint and Flint 2005:73–75). Yet there had been many such intrusions already, and there would be others. Past conflict was part of the reason Esteban was not welcomed at Cibola, for when the Cibolans saw what were probably Tarascan bells on Esteban’s gourd, they recognized these as being the type made by their enemies. Still, and importantly, it was not until much later that Europeans became relevant to indigenous peoples—when disease, new technologies, crops, and livestock were introduced, when the slave traders arrived, when new alliances formed, when tribute was demanded, and when there was a sustained European presence.

Too heavy a reliance on historic documentary sources has skewed history toward one focused on Europeans (Rubertone 2000:428; Seymour 2011a). Yet the observed people did not immediately change; rather, our ability to access knowledge of them has in the recent past hinged on the presence of a historic record. Thus, with the commitment of ink to paper, Cabeza de Vaca and Marcos de Niza established the conceptual framework used to study indigenous peoples. The view has been from the outside in. In contrast to prehistoric periods, the Protohistoric period is defined by external events and processes that have nothing to do with local and regional developments and everything to do with the arrival of Europeans. It is this conceptual framework that is in need of reconsideration. The data provided in the documentary record are to be welcomed, but our understandings of who these indigenous people were, where they came from, and what events and processes affected them most must be rooted in archaeological data, for it is one of the best sources for examining the long term. Critically assessed oral history can also be of help in this way, especially when the information is passed directly on. Importantly, however, circumstances do not change for the reticent native positioned at the edge of the explorer’s camp when mention of him is committed to parchment. Awareness of smoke in the distance did not alter fundamental lifeways for people who had long resided along ancient travel routes.

The indigenous inhabitants have been viewed through the lens of Europeans whether contact was relevant or not. Once the Historic period begins, scholars tend to focus on Europeans and consider indigenous occupants only in relation to Europeans. This is why I have intentionally excluded contributions that involve using European artifacts as indices of this period. Although as Thomas (Chapter 21) notes, it is important to use the full suite of tools available to investigate sites of this period, Protohistoric Native American historic research has taken a turn where we no longer must rely on European artifacts to identify indigenous components. Significant advances have been made that allow us to identify these components and sites solely on the basis of the indigenous material culture. Previously, native modifications to European artifacts or trade goods were required to identify Protohistoric sites. When we can identify mobile group evidence without metal detecting or European artifacts, we are better able to understand origins, timing, and a host of other processes (Seymour 2010b, 2010c).

Because of the bias toward Europeans and in an attempt to counter it, some scholars extend the Protohistoric period well into the Historic period, terminating it at perhaps the mid-i700s or at 1800, so as to remain focused on natives. Because records of initial contact are usually sketchy and it is difficult to evaluate impacts of European presence, the Protohistoric period tends to include the beginning of the Historic period, a shadowy time when records are sparse and Europeans came and went but did not stay. The Native American Historic period tends to be subsumed into and considered a subset of European colonial history, with European-relevant phases and research themes focused on topics pertinent to Europeans. In mainstream historical archaeology, indigenous happenings are evaluated and valued only with respect to their impact on and as a consequence of European history. Indigenous occupants are not in themselves considered historic peoples! As such, they have generally been outside the course of study for historical archaeologists, relegated to prehistory, protohistory, or Native American studies (Seymour 2013b). It has been agreed for some time that although “the proper concept of American history would not exclude the aborigine,” the field would focus on “the history of white men in North America” (Harrington 1978:3). Native American sites become relevant to historical archaeology “only when their basic cultural and ecological patterns have been altered by contact and when this is displayed in the archaeological data” (Schuyler 1970:85).

Fortunately, most Southwestern scholars consider Native American history part of the Historic period. The chapters herein are concerned with indigenous developments and focus on local sequences and processes. While many rely on historical documents and ethnographic data to frame questions or provide interpretive guidance, they are concerned with understanding the Protohistoric period from an archaeological perspective that focuses on indigenous populations. In doing so, they hope to capture relevant aspects of local and regional sequences and to develop new understandings on which to base more meaningful chronologies and narratives.

From Late Prehistory to Late History

The chapters in this book cover many of the non-Puebloan groups present throughout the American Southwest during the Terminal Prehistoric and Historic periods. The authors are attempting to define these groups, sometimes for the first time (culture history), at the same time placing them in more generalized contexts and attempting to understand a range of larger implications. We can only benefit from thinking more broadly, envisioning a much more encompassing area, and considering cross-regional processes. Because scholars tend to work within modern geopolitical boundaries, there is less consideration of similarities across state and international lines or between regions than would be beneficial. Space and time are used to separate the major prehistoric culture groups, but most of the peoples discussed in this book were mobile, so they moved throughout much larger areas. Consequently our conceptions and understandings of this time period will only be improved by thinking much larger, by comparing regions, and by examining behavioral similarities between distinct groups. Moreover, archaeologists could learn from the methodological developments in adjacent areas that are suitable to these groups, whereas now-current boundaries provide an excuse not to cite relevant literature and to be distrustful of results.

During the Protohistoric period vast expanses of the Southwest were occupied by small groups that moved over hundreds of miles and whose territories overlapped; consequently more than one contemporaneous group was present in each area. Together their territories encompass vast tracts that include Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico, not to mention Nevada, Texas, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Coahuila. In addition to moving throughout broader expanses than their farming neighbors, they traded, raided, scavenged, and intermarried with and kidnapped people from neighboring groups. If we know the patterns representative of groups in surrounding areas, we can isolate those within specific geographic areas. We are also learning that one group, such as the Apache, may be very different when bordered on the west by the Yavapai than when bordered on the east by the Jumano.

One of the most important messages of this book is that the types of sites left by mobile peoples can be identified and studied (Chapters 4, 7, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 19). Many researchers have stated that these types of sites are not discoverable, as their occupations were too short or the impact too light. For example, Spielmann (1982:301–302) comments with respect to mobile group evidence around the Salinas Pueblos: “A combination of highly impermanent structures and probable short-term occupations makes it highly unlikely that much will be recoverable archaeologically.” Discussing the depopulation model following the Jornada Mogollon El Paso phase in southern New Mexico, Lockhart (1997: 115) suggests: “From the ‘abandonment’ to the arrival of the Spaniards in the Southwest, such [mobile group] camps would be archaeologically ‘invisible.’” These are just two of many similar statements that judge the evidence far too ephemeral and unobtrusive to identify. Nevertheless, the chapters of this book present tangible evidence of these peoples across the North American Southwest. There is much to be learned from these sites, including new avenues of research and rethinking of existing research themes. The information contained in these sites is relevant to prehistory and to history, as well as to modern descendant tribes that directly trace their lineage to them.

Recognition of these sites is enhanced when examples are recent enough for perishable elements of features to be preserved. Usually archaeological evidence for hunting is provided only by projectile points and faunal material. It is rare indeed to find evidence of hunting structures used in traditional forms of communal hunting. Copeland’s (Chapter 14) archaeological examples of perishable game traps are an important landscape element regarding cultural subsistence practices. As Copeland notes, when these features deteriorate, there will be little or no physical evidence of their existence.

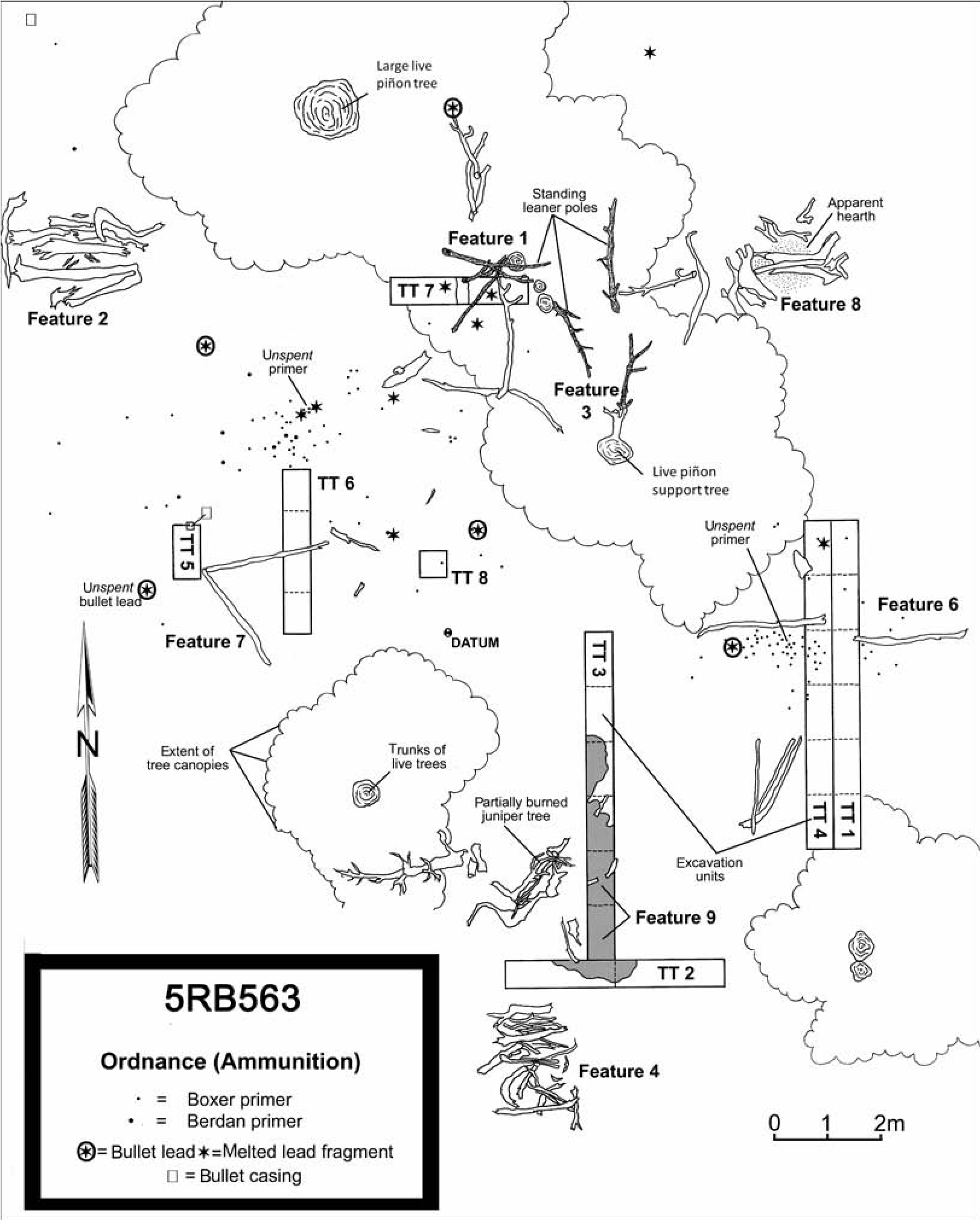

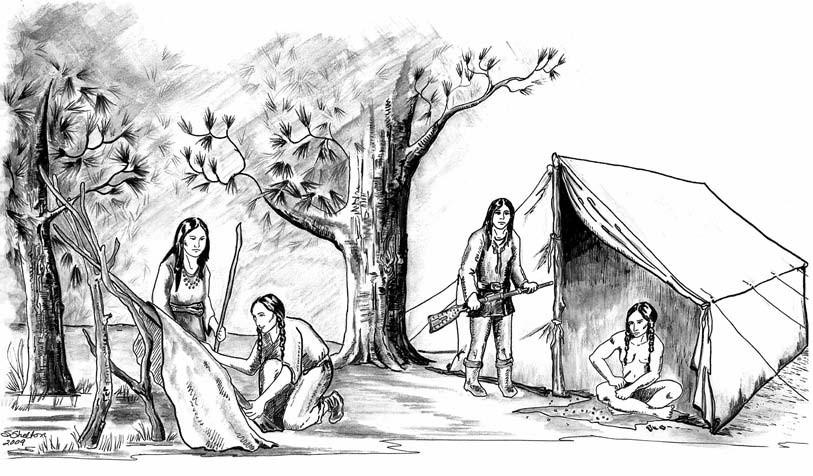

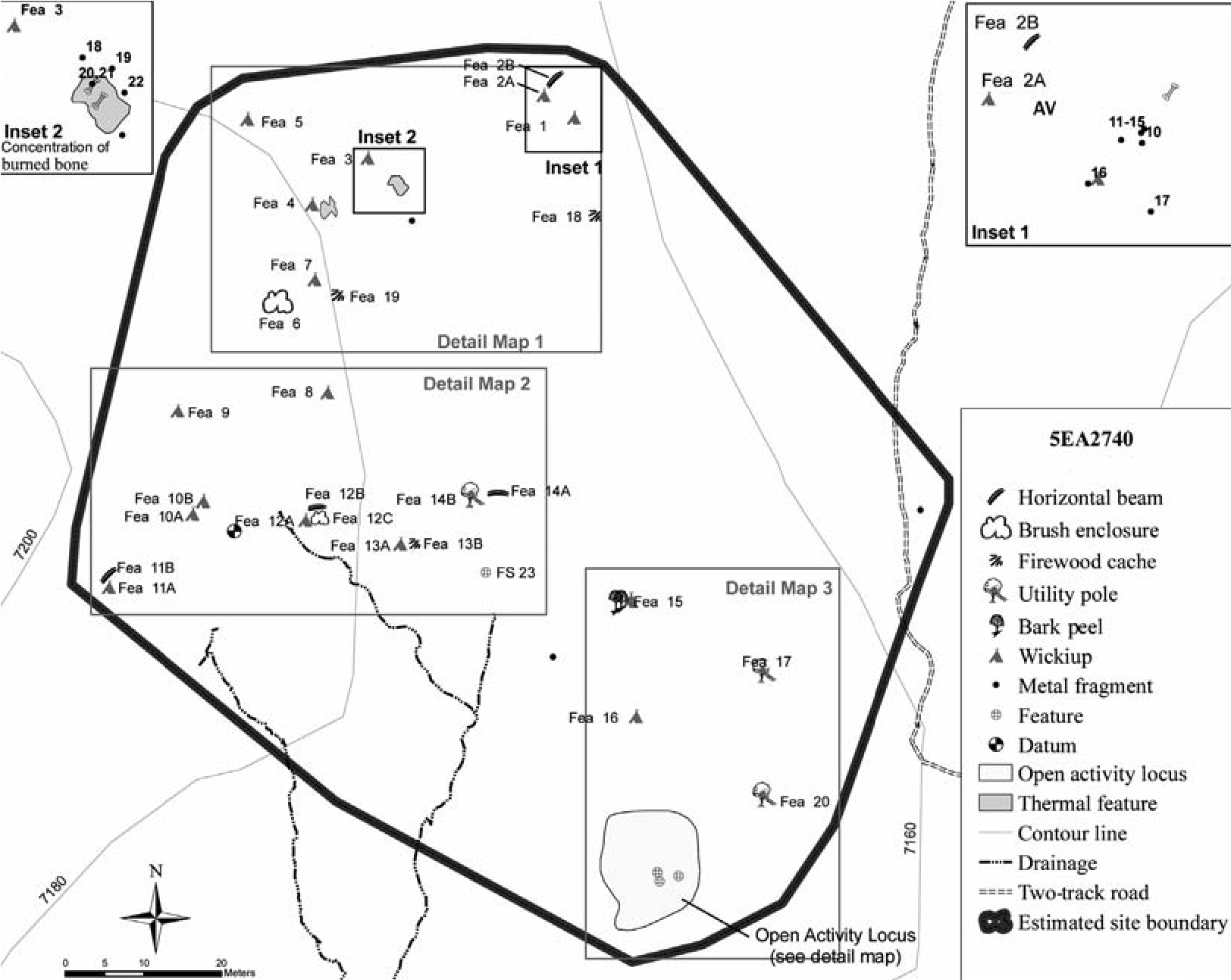

Work on Late Historic Ute sites provides an unprecedented look at material culture, house construction techniques, and the use of space. Martin’s (Chapter 15) study of still-standing wickiups provides rich insights into aspects of the Ute not preserved in earlier contexts, including site structure, the use of space, wickiup construction, and the range of artifacts used.

Such is the case with Promontory Cave, Utah, which represents an exceptional sample with intriguing new analyses, as mentioned by Thomas (Chapter 21). Yet most Protohistoric mobile group sites are in the open, and there is little preserved with relatively few artifacts. We must nonetheless figure out how to make these sites useful, including where little or no datable material is present. Less prolific sites have value, and we must continually work on ways to extract what data they do possess by studying them on their own terms rather than seeking only rarely occurring, exceptionally strong sites as our only focus (Seymour 2010a, 2013a, 2017).

Turbulence usually accompanies the presentation of new findings, a fact to which many authors in this book can attest. This is no less true of the strong new evidence that is mounting regarding the early presence of Numic-speaking peoples in the northern Southwest. Ancestral Ute people were likely in the northern Southwest by the late 1200s and certainly by the 1300s, an inference supported by recent evidence from a fourteenth-century site in northeastern Utah (Chapter 16) and Brunswig’s (2005:227–228, 2013:24, 27) early Ute sites.

Like Ute and Apache archaeology, Yavapai archaeology has long been recognized but is acknowledged with a degree of hesitancy because of its unobtrusive character. Pilles’s contribution (Chapter 19) speaks to the core of the issue of using appropriate conceptual models. The chapter struggles with the question of how to connect what has been found archaeologically to ethnographic and historic entities, how to effectively distinguish the record, and how to make what sometimes seems a monumental step from description to interpretation, from archaeological manifestation to ethnic or cultural entity. Efforts to make sense of the faint footprint have been frustrated by conceptual models brought to bear that are more appropriate for more stationary groups—models that dominate thinking in our region. When we accept the nature of the data as they exist, we can devise more appropriate methodologies and establish effective conceptual frameworks and middle-range theory (Seymour 2010a). With appropriate bridging arguments, speculation can be differentiated from inference building.

Impact on Prehistoric Populations

Defining these groups archaeologically and ascertaining the timing of their arrival or movements and transitions remain key questions for this time period throughout the Southwest. One important implication is the effect of the entrance of mobile groups on local sedentary farming populations and their role in the reorganization of other Southwestern cultures. Kemrer’s and Craig’s chapters (2 and 12) set the stage for the Late Prehistoric period and explore interrelations between established sedentary groups, while others show that the manifestations of later times have their origins in this Late Prehistoric period (Chapters 16 and 17). While the chapters by Kemrer and Craig are not about mobile groups, they are included to show what went before and to demonstrate what the regional landscape looked like from the perspective of the existing peoples. Craig’s contribution (Chapter 12) examines the issue of the Late Prehistoric period in the Hohokam area of southern and central Arizona. The Hohokam did not disappear but rather utilized different environmental settings, and their adobe features are difficult to recognize from surface evidence. This issue is also discussed by Harlan and Seymour (Chapter 13), who reevaluate social network analyses for the San Pedro Valley in southeastern Arizona, supplementing existing databases with information on Sobaipuri Oodham and mobile group sites. The shift to the Oodham pattern occurs at the same time as ancestral Pueblo groups retract to the north.

Because the chapters proceed geographically from east to west and south to north, Kemrer’s contribution begins the book. He discusses a Terminal Prehistoric context and a response to violence that began in southern New Mexico at about ad 1150. Speth (Chapter 3) introduces evidence of both amiable and violent interaction between existing Late Prehistoric semisedentary populations and mobile groups in the first decade or two of the ad 1300s. Seymour’s (Chapter 4) work at the Eastern Frontier Pueblos has produced evidence of mobile group encampments near pueblos, including evidence for short-term visitation and large groups wintering over as early as the ad 1200s. In Chapter 5 Beckett argues that the Jumano and Suma encountered by the Spanish are the descendants of the prehistoric Eastern Extension of the Jornada Mogollon.

Indigenous Perspectives

Indigenous and alternative perspectives of what archaeologists study provide insights into community organization, persistence of cultural entities, identity, meaning, and perceptions of landscape. In Chapter 6 Rodriguez and Seymour discuss how the process of federal recognition does not take into account the unique organizational aspects of mobile peoples. Like other Apaches and mobile groups, Rodriguez’s Lipan ancestors did not organize themselves in tribes as they are presently perceived, but rather resided and operated in small local groups and recognized band associations, only occasionally gathering in larger multiband associations that might be considered a tribe. This traditional practice has considerable implications for seeking official recognition when demonstration of tribal unit persistence is one of the main criteria used in decision making.

Stokes and Tactikos (Chapter 18) show that small places on the landscape may retain significant cultural meaning to indigenous populations, even if they no longer actively visit, use, or occupy these places. Many modern treatments suggest that such places are part of a landscape imbued with multiple layers of meaning and purpose because indigenous people maintain different concepts of linear time, reuse, abandonment, and ownership than others. Seymour (2009b, 20iod, 2011c, 2012c), however, attributes at least part of this to key differences between highly mobile peoples and those that are more settled. Consequently, rather than seeing this as an indigenous versus modern (or Indian versus Western) conception, we may find it useful to examine different types of attachment to the landscape relative to degrees and types of mobility. It is also useful to critically assess whether such concepts are retained in tradition or whether they represent an important aspect of the revitalization of traditional values and connections. Many Apache and Oodham have forgotten their connection to important places, a consequence of the danger awaiting them beyond reservation boundaries, government removal and reeducation efforts, changes in lifeways, and extreme poverty. Nonetheless, they may still be awed and often feel a connection when visiting ancestral sites, as do non-indigenous visitors. People worldwide repurpose, revive, reinvigorate, reinterpret, and maintain interest in historical and ancestral places (Seymour 2011cm. 61, 2012d).

Chapter 19 demonstrates a Yavapai presence after 1870 in an area said to have been abandoned, demonstrating how political and economic factors influence historic accounts of indigenous distributions. A similar narrative exists around the Oodham’s departure from the eastern portion of their traditional homeland along the San Pedro River in southern Arizona. They were said to have abandoned the San Pedro in 1762, but there is clear evidence that many of them stayed (Seymour 2011c). Moreover, archaeological evidence suggests that when land grants were issued in the 1830s along the San Pedro, Oodham residents were still there (Seymour 2011a, 2011c). Likewise, Martin’s (Chapter 15) Ute sites demonstrate a continued presence in areas thought to have been devoid of indigenous occupation, contradicting understandings regarding historic Ute distributions that rely on existing documentary and historical evidence. These sites represent Utes who did not participate in the mandatory 1881–1882 relocation to reservations. Each of these examples highlights the important role archaeology plays in setting the record straight and in contributing to a more prominent voice for the indigenous elements of history.

Evidence of Mobile Groups: Material Culture

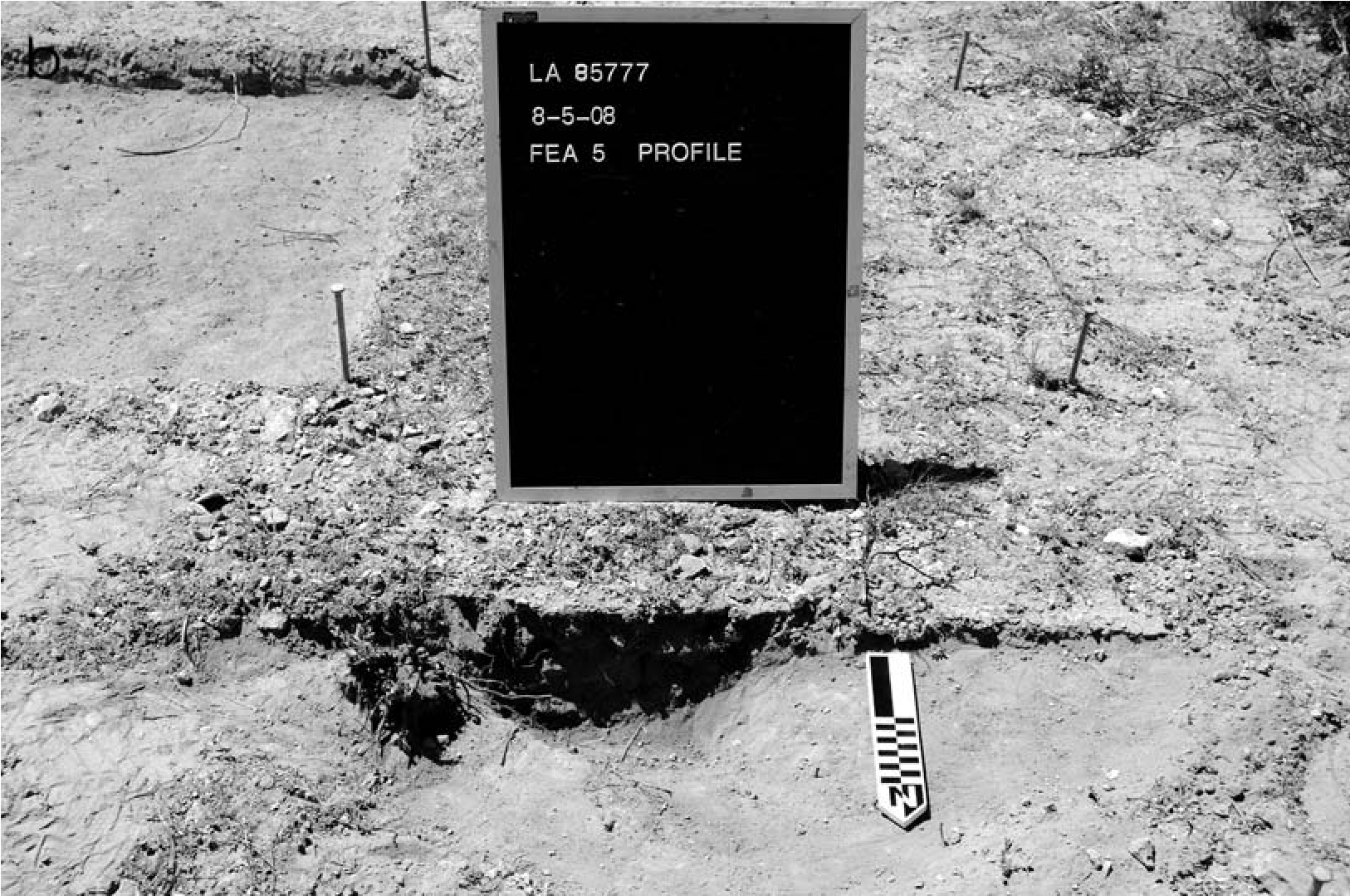

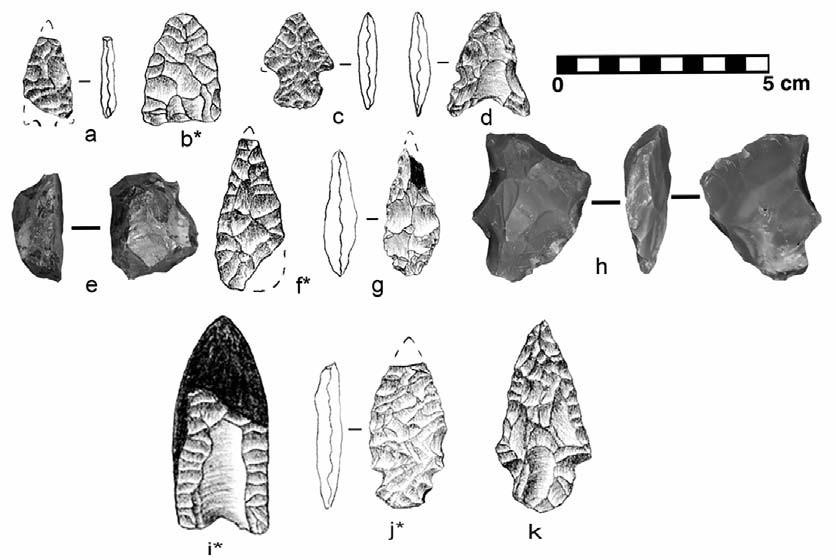

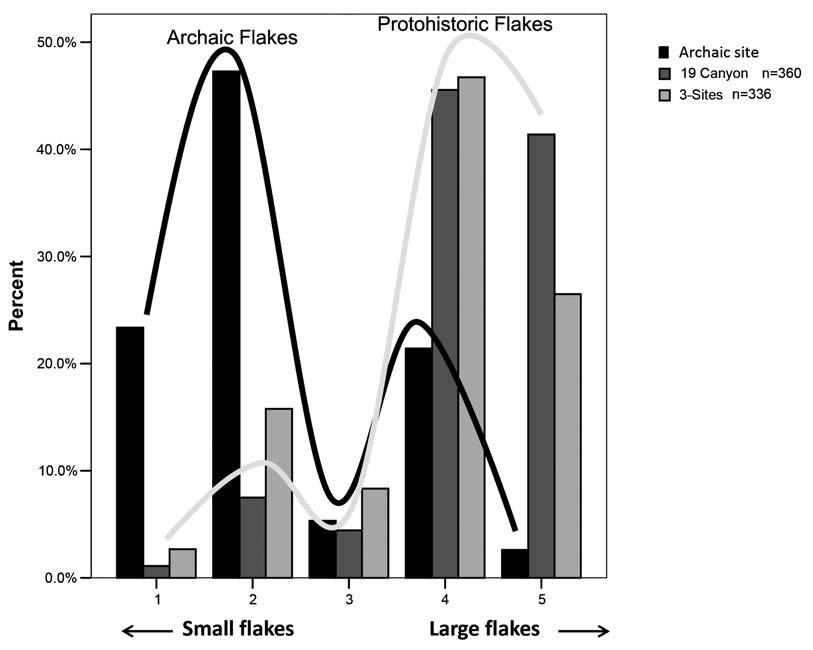

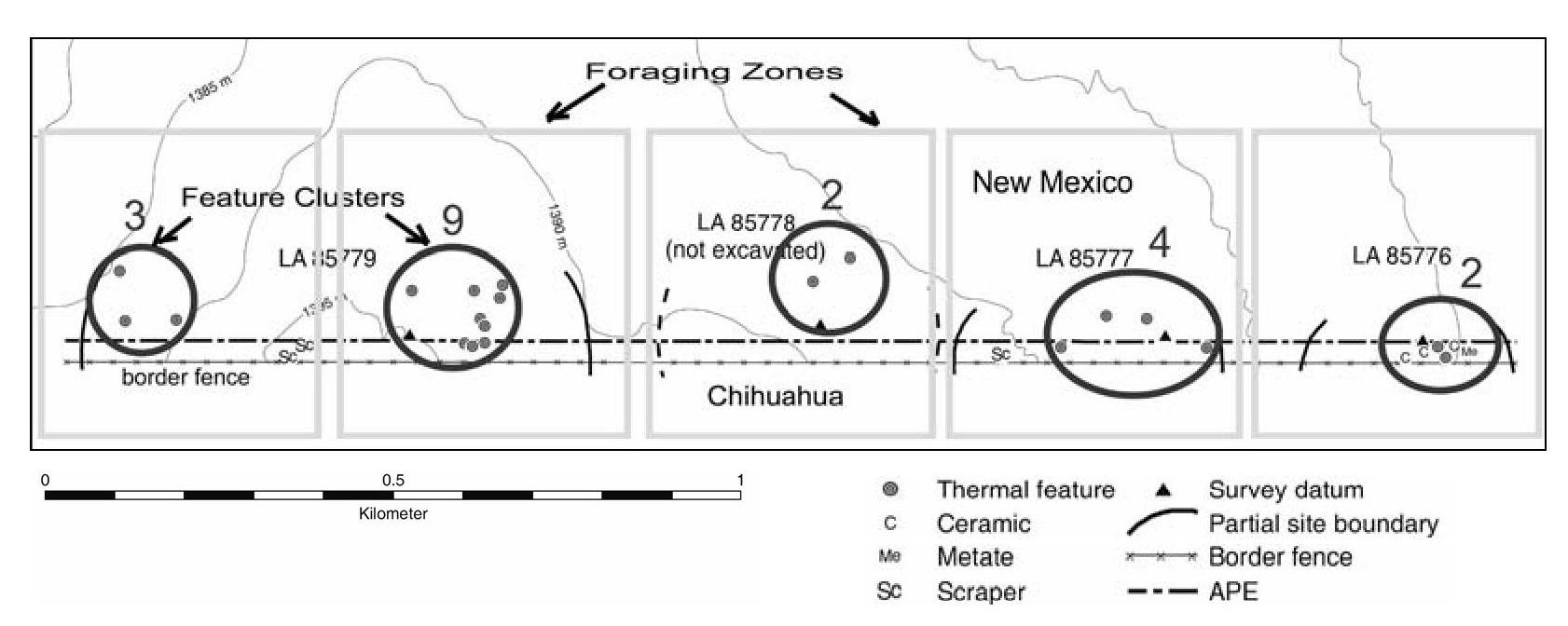

Kurota (Chapter 7) isolated Protohistoric manifestations when all other indications, ceramics and lithic artifacts, at the sites pointed to a prehistoric presence yet every excavated feature dated to the Protohistoric/Early Historic era. As is typical, many of the features were nondescript and vague, and crews were hesitant to record them as cultural, even scoffing at Kurota—reactions that are all too common—only to change their minds when confronted with dating results.

Interpretations rely on basic assumptions, so it is important for these to be sound. Moore’s (Chapter 8) contribution on stone tool use among Spanish New Mexicans provides a basis for questioning the meme that stone tool use is an indication of an indigenous component. With imports such as metal so costly and rare, local residents resort to more economical alternatives, such as stone, reworked glass, and repurposed metal, to carry out daily tasks. I have argued that such use reflects the practices of people living outside mainstream economic systems, showing that human behavior in broadly different contexts often converges when people are faced with similar life circumstances. These commonalities are worthy of study and should not be confounded with inferences about ethnicity.

Many of the archaeological correlates established to define the ancestral Apache—such as structural rings—actually apply to mobile groups in general because these correlates are adaptation-based. They are found crossculturally among mobile peoples, based on degree of mobility, expectation for duration of stay, and a variety of other factors (Seymour 2008b, 2009c, 2009d, 20iod, 2013c, Chapter 4). Consequently, other criteria of affiliation must be considered, given that a number of different mobile groups were present. It is understood that pottery and points are the most commonly used material culture classes to distinguish between groups, but in the Protohistoric period these are frequently absent from sites, including those used for habitation. One reason for this is that sites were used for such a short period that materials did not have a chance to accumulate. Moreover, many groups did not use pottery on a routine basis, and for the Apache there remain questions as to whether pottery was part of their household assemblage when they first arrived in the American Southwest.

When pottery and points are present, they are not always sufficiently distinct to allow us to discern ethnicity. Moreover, artifacts from other groups are often present because of raiding, trading, and scavenging (see Seymour 2014a; Chapter 17), yet all too often their presence leads to misconceptions about cultural affiliation because mobile group assemblages tend to be limited (Seymour 2010a, 2014a, 2017; Chapter 4). For all these reasons, points and pottery are most useful for discerning the correct time period, but additional interpretations must consider the processes responsible for their presence. Equally important, when pottery and points are not present, just as when glass and metal are absent, we must still be able to identify a Protohistoric presence on the basis of other tool forms and styles, technological characteristics, hut construction attributes, site layout, and landscape use. Points and pottery, though, remain the diagnostics of choice, used for discerning temporal and cultural affiliation, and the chapters by Harlan (9), Loendorf (10), and Hill (11) focus on what some of this variation means.

When effective, the material culture studies directed toward mobile groups underscore the unique arrays and forms of data as well as fresh perspectives that engage models specifically adapted to mobile groups. This is nowhere more apparent than with respect to ceramic production. Cross-cultural ceramic studies have shown that clays are obtained within a 5-km radius of settlements, yet mobility brings people in contact with clay and lithic sources many hundreds of miles apart and so the compositions of their tools and pots may be highly variable (Seymour 2008c). Moreover, the use of numerous encampments means that each may be near sources with different clay and inclusion compositions. These are some of the factors that explain the especially high variability in Protohistoric plainwares and the compositional diversity that characterize mobility. Hill (Chapter 11) describes the ceramic assemblages of mobile peoples as smaller than those of stationary groups, with limited vessel forms and with more compositional variability as a result of trading and raiding for vessels.

Concluding Statement

One reason the archaeology of this period has remained undefined is that it differs and is often less obtrusive than that of earlier and later periods. Lack of attention to these archaeological cultures has persisted for decades despite the fact that historical records document their presence and in many cases tell us where to look and what will be found. Although the documentary and archaeological records have different spatial and temporal scales, the processes we infer may be effective in establishing isomorphism between documentary content and archaeological observations, with theory as the connective element. With rigorous evaluation of the correspondences between sources, both implied and direct, it is possible to distinguish groups archaeologically and assess their relationship to historical documents. Documentary content is not the same as systemic context, and the Spanish emic perspective should not be confused with that of the indigenous residents.

Many scholars have assumed that the Protohistoric period is characterized by relatively little variability, whereas in fact the chapters in this book demonstrate that the lifeways and their resulting material record were highly variable. Even nations thought of as single political entities, such as the Oodham, Apache, and Jumano, were actually composed of many different groups that practiced different ways of life in their respective geographic areas.

Other scholars assume that this period was not complex but rather is a temporal backwater to the two more important periods that bracket it, or that the mobile people were of secondary importance to the settled farming groups. In fact, this period may be much more complex than earlier or later periods and is certainly more challenging than Puebloan archaeology. While the often meager material culture is frequently equated with simplistic, this period is far from simplistic, and the peoples represented are highly varied in their representations.

Clearly, it is time to dispense with existing notions that Protohistoric mobile groups are unknowable and that their archaeology is too ephemeral and unobtrusive to find, understand, or be of use. It is time to rescue the archaeology of these transient groups from neglect and integrate them into the mainstream of archaeological inquiry. This requires new conceptualizations of method and theory. While only in the last decade have some of these groups been defined archaeologically, their importance is already being recognized. And while there are sometimes stormy reactions to new findings, a robust body of evidence is amassing that should no longer be ignored. The general reluctance to incorporate new data and to reconceptualize this period is giving way to excitement at the new challenges that these data and formulations pose.

2. Terminal Puebloan Occupation

An Example from South-Central New Mexico

Meade F. Kemrer

This chapter describes the formation, composition, and related organizational characteristics of a Terminal Puebloan occupation in the Jornada Mogollon area in south-central New Mexico (Figure 2.1). Viewed as the outcome of regional integration, this settlement represents a transitional form, a precursor to the fully integrated pueblos dating to the Protohistoric and Historic periods. The sites discussed here represent two architectural forms: those often found in the Sierra Blanca area, consistent with the “Lincoln expression” villages described by Marshall (1973), and local pueblo construction types found farther to the south. Consequently, Whalen’s (1980) generalized ad 1300–1400 Late Pueblo period is a more appropriate cultural/ temporal category for these southern San Andres sites than the “Lincoln phase” or “El Paso phase” terminology. Ceramic assemblages date the Late Pueblo to ad 1275–1400 in the study area.

Background