Documentation Center of Cambodia

A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)

2020

Chapter 2: Who Were the Khmer Rouge? How Did They Gain Power?

1. The Early Communist Movement

2. The Creation of the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (Kprp)

3. The Workers’ Party of Kampuchea (Wpk)

4. The Communist Party of Kampuchea (Cpk)

Chapter 3: The Khmer Rouge Come to Power

1. The Khmer Rouge March Into Phnom Penh

2. The Evacuation of the Cities

Chapter 4: The Khmer Rouge Come to Power

2. A Voice From a Civil Party Doctor

3. Witnesses in the Eccc on the Massacre at Tuol Po Chrey

Chapter 5: The Formation of the Democratic Kampuchea Government

2. Prince Sihanouk Returns to Cambodia

4. Prince Sihanouk Resigns as Head of State

5. Organizational Structure of Democratic Kampuchea

6. Changing the Party’s Anniversary

Chapter 6: Administrative Divisions of Democratic Kampuchea

Chapter 7: The Four-Year Plan (1977-1980)

Chapter 8: Daily Life During Democratic Kampuchea

1. The Creation of Cooperatives

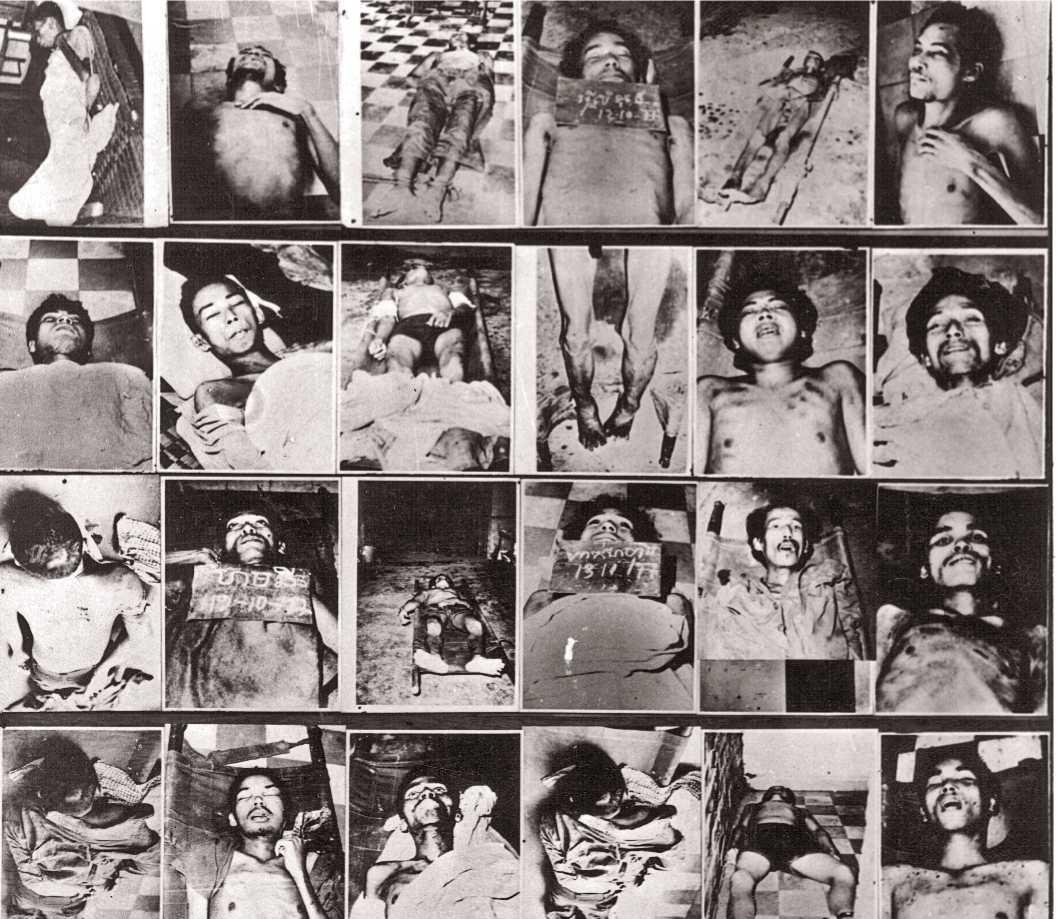

Chapter 9: The Security System

Chapter 12: The Fall of Democratic Kampuchea

1. Three Reasons Why Democratic Kampuchea Fell

1. Eccc Legal Principles, Concepts, and Laws as Derived From the Eccc Law and References

The Accused’s Rights of Defence:

Chapter 15: Apologies by Kaing Guek Eav, Alias “Duch”

Chapter 16: Impact of Mass Atrocities, Genocide, and Human Rights Violations on Individual People

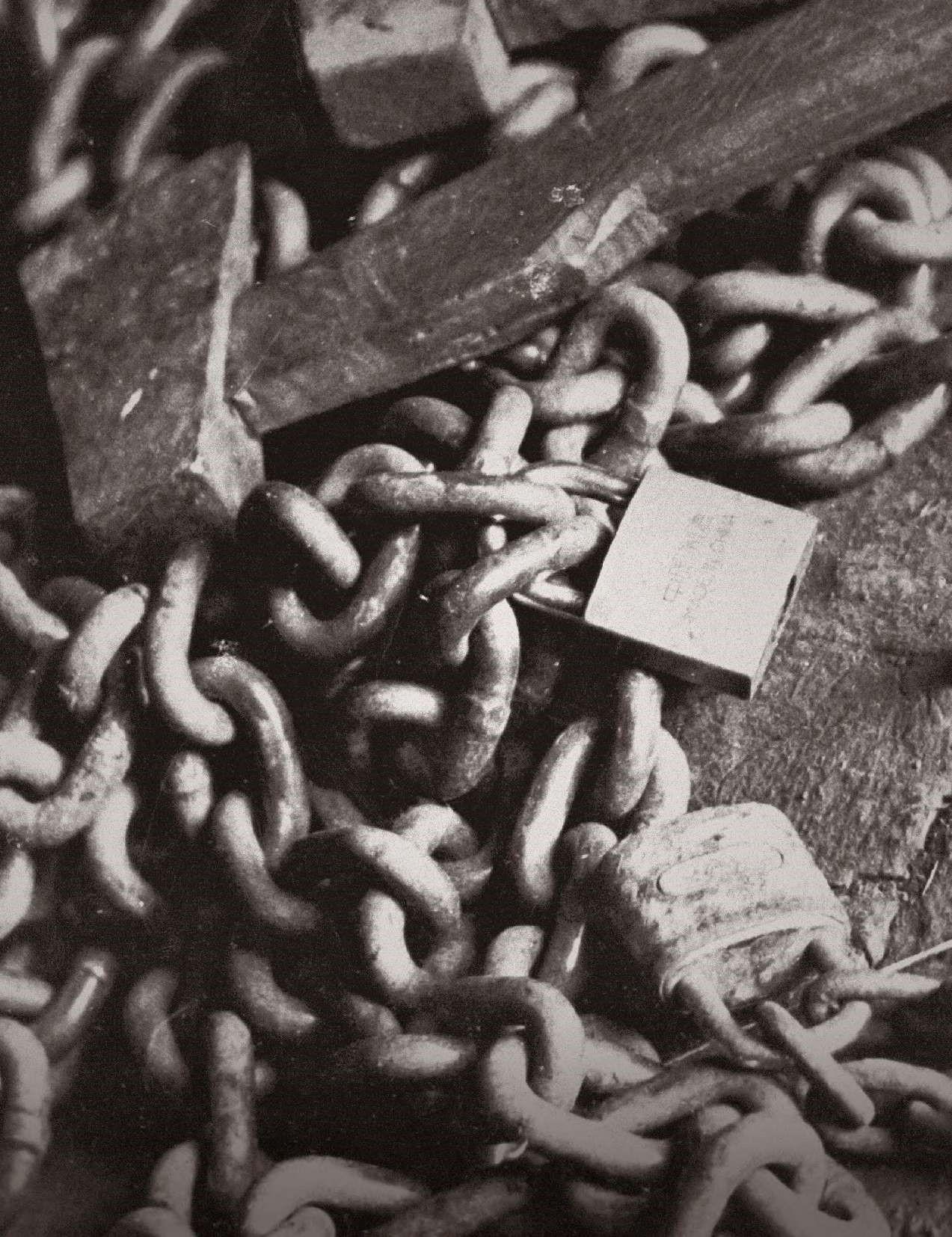

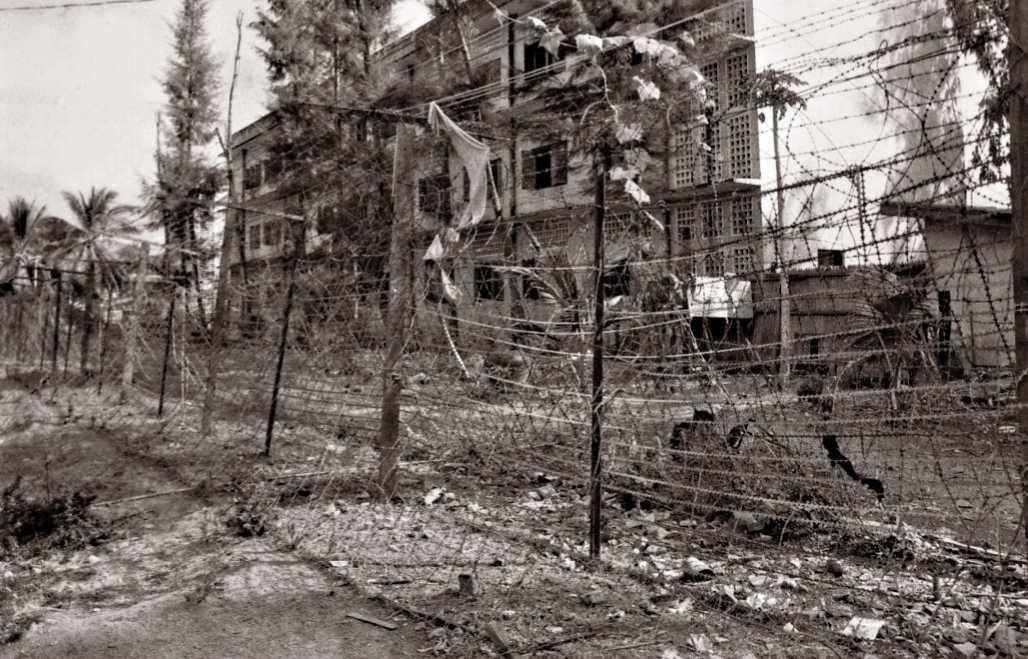

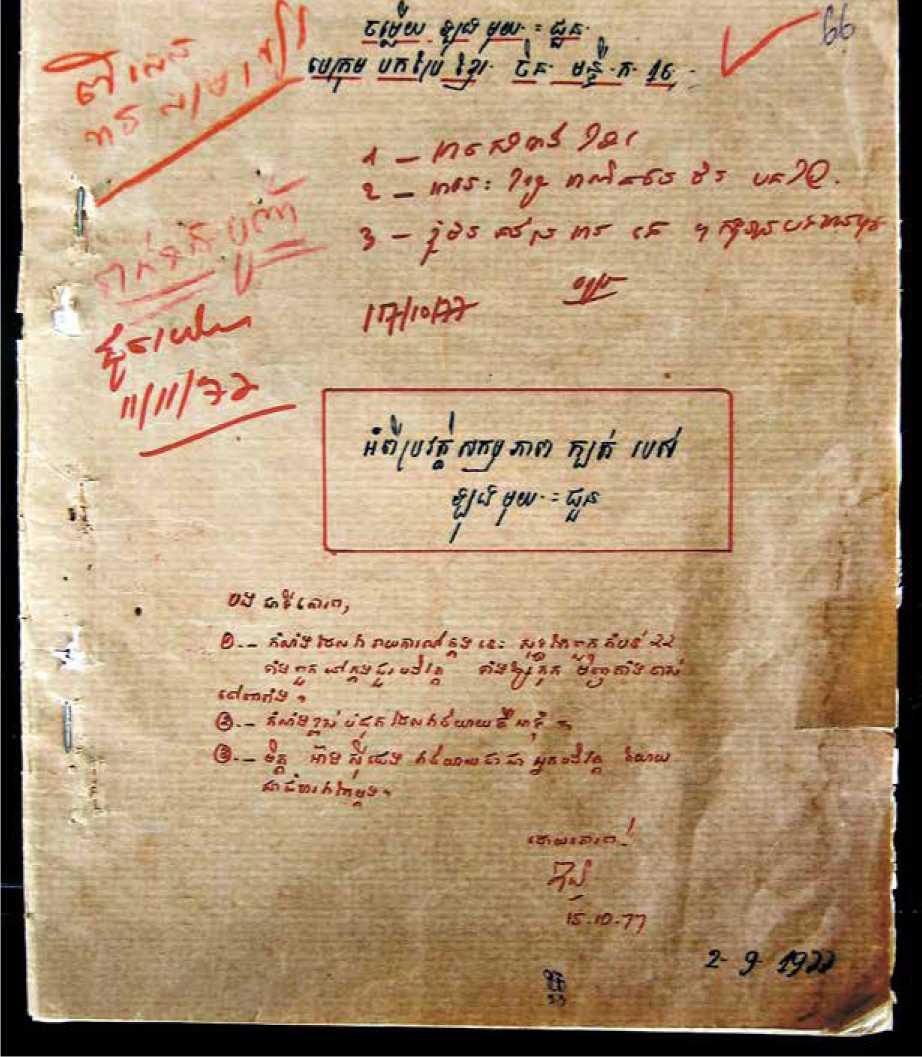

Regulations for Guards at S-21

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

A HISTORY

OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA

(1975-1979)

DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA 2020

2ND EDITION

[Epigraph]

“Cambodia will never escape her history, but she does not need to be enslaved by it”.

[Publisher Details]

JUSTICE & MEMORY

Documentation Center of Cambodia

Villa No. 66, Preah Sihanouk Blvd.,

Sangkat Tonle Bassac, Khan Chamkar Mon

Phnom Penh 12301

Cambodia

t: +855 (0) 23 211 875

e: dccam@online.com.kh

w: www.dccam.org

A HISTORY OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA

1. Cambodia-History-1975-1979

SECOND EDITION, 2020

Pheng, Pong-Rasy

Chandler, David

Dearing, Christopher

Sopheak, Pheana

FIRST EDITION, 2017

Dy, Khamboly

Chandler, David

Cougill, Wynne

Funding for this project was generously provided by Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Civil Peace Service, BMZ and Swedish International Development Agency. Support for DC-Cam’s operations is provided by the United States Agency for International Development.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the authors only.

2020 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Concept and book design: Stacy Marchelos, in conjunction with Double Happiness

Creations, Inc., Ly Sensonyla and Youk Chhang.

Photo captions: Dacil Q. Keo, Youk Chhang, Sopheak Pheana and Try Socheata.

A HISTORY OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA (1975-1979)

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Foreword

Chinese diplomat Chou Ta-Kuan gave the world his account of life at Angkor Wat eight hundred years ago. Since that time, others have been writing our historyfor us. Countless scholars have examined our most prized cultural treasure and more recently, the Cambodian genocide of 1975-1979. But with this book, Cambodians are at last beginning to investigate and record their country’s past. This new volume represents several years of research and marks an updated edition of the original text, which was authored by a Cambodian.

Writing about this bleak period of history for a new generation may run the risk of re-opening old wounds for the survivors of Democratic Kampuchea. Many Cambodians have tried to put their memories of the regime behind them and move on. But we cannot progress—much less reconcile with ourselves and others—until we have confronted the past and understand both what happened and why it happened. Only with this understanding can we truly begin to heal.

This textbook is intended for high school students; however, it can also be helpful for adults. All of us can draw lessons from our history. By facing this dark period of our past, we can learn from it and move toward becoming a nation of people who are invested in preventing future occurrences of genocide, both at home and in the myriad countries that are today facing massive human rights abuses. And by taking responsibility for teaching our children through texts such as this one, Cambodia can move forward and mold future generations who work to ensure that the seeds of genocide never take root in our country again.

Youk Chhang

Director

Documentation Center of Cambodia

Acknowledgements

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is proud to announce the publication of the second edition of its history textbook, The History of Democratic Kampuchea. The second edition includes new chapters that discuss post-genocide justice as well as new information and stories that have come out in proceedings and decisions of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). The second edition provides readers with not only historical information about the Khmer Rouge regime, but also basic facts and concepts about the establishment, organization, and work of the ECCC.

As the authors (Pheng Pong-Rasy, Sopheak Pheana and Christopher Dearing) state in their book, “[t]he ECCC’s judgments helped the Cambodian people and the world come to a better understanding of what led up to and ultimately occurred during the Khmer Rouge regime.” With this book, it is hoped that some of this information can now be incorporated into new classes and lessons for Cambodian students and the public.

None of this would be possible without the incredible support of a number of important stakeholders. DC-Cam would like to thank the Cambodian Government for initiating and supporting the teaching of the Cambodian Genocide since the early 1980s. The Government’s continued support for the education of the younger generation has been crucial to the country’s future.

DC-Cam would also like to thank the Ministry of Education, who has been a long-time partner with DC-Cam. I hope this book will help countless teachers and students study the country’s dark past.

Thank you to the donors, both those who specifically funded the publication of this book as well as those who provide general support to DC-Cam. Funding for this book was generously provided by Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, the Civil Peace Service, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), and the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida). DC-Cam would also like to thank the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which continues to provide generous support to DC-Cam’s work.

Last, but not least, DC-Cam would like to thank the five million Khmer Rouge survivors. Their ongoing effort to re-tell their stories ensures this history will not be forgotten. This book is dedicated to them.

The history of the Khmer Rouge must belong to each and every person in Cambodia, not only as a matter of right, but also obligation. A vibrant democracy depends on the equal rights of all citizens to fully participate in its affairs; however, citizens bear an equal responsibility to be informed stakeholders. A citizenry that is ignorant, dismissive, or unappreciative of its past only invites the hardships and inhumanity that plagued the generations before. Cambodia’s future depends on education, both as a civil right as well as an individual moral obligation. This book will give students and the public one more tool to realize these benchmarks of individual and collective maturity.

Youk Chhang

Director

Documentation Center of Cambodia

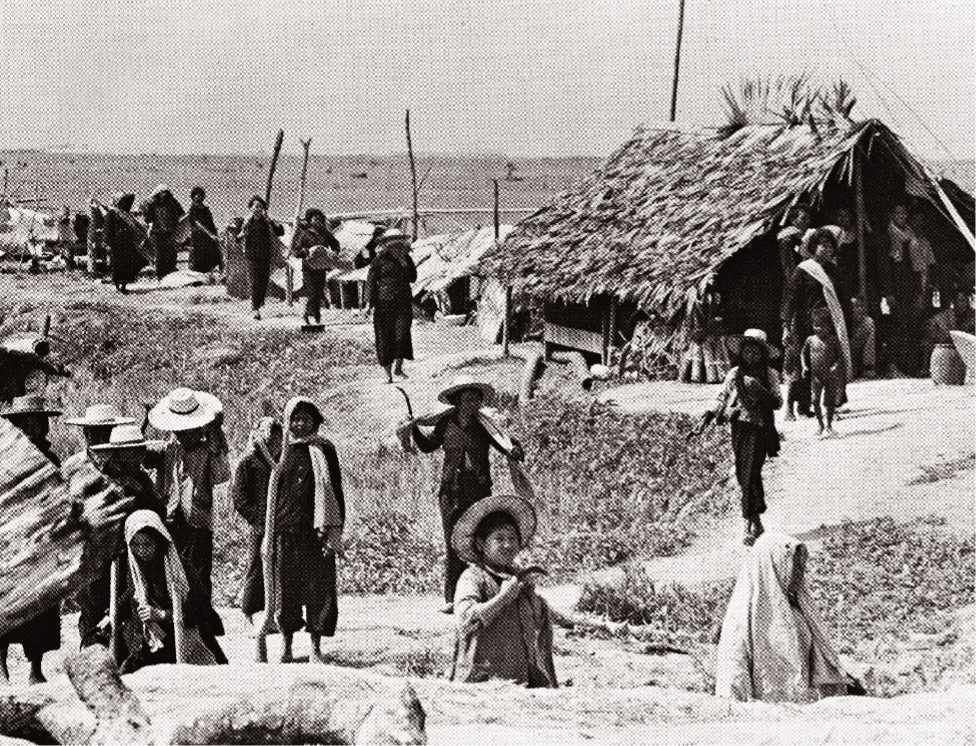

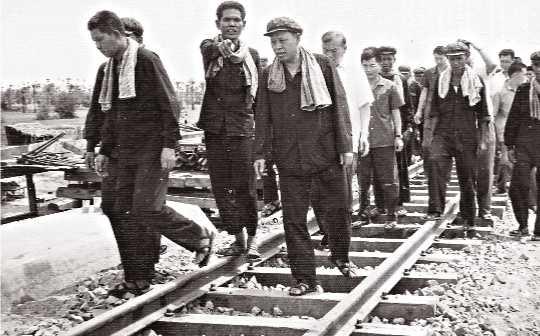

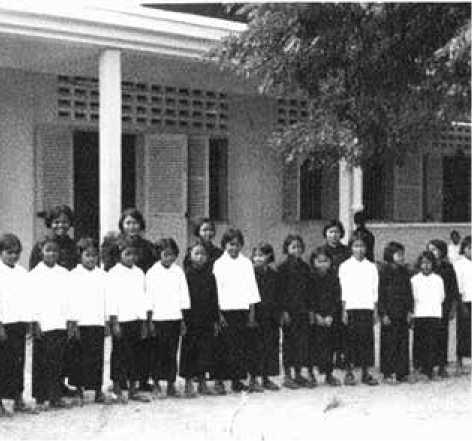

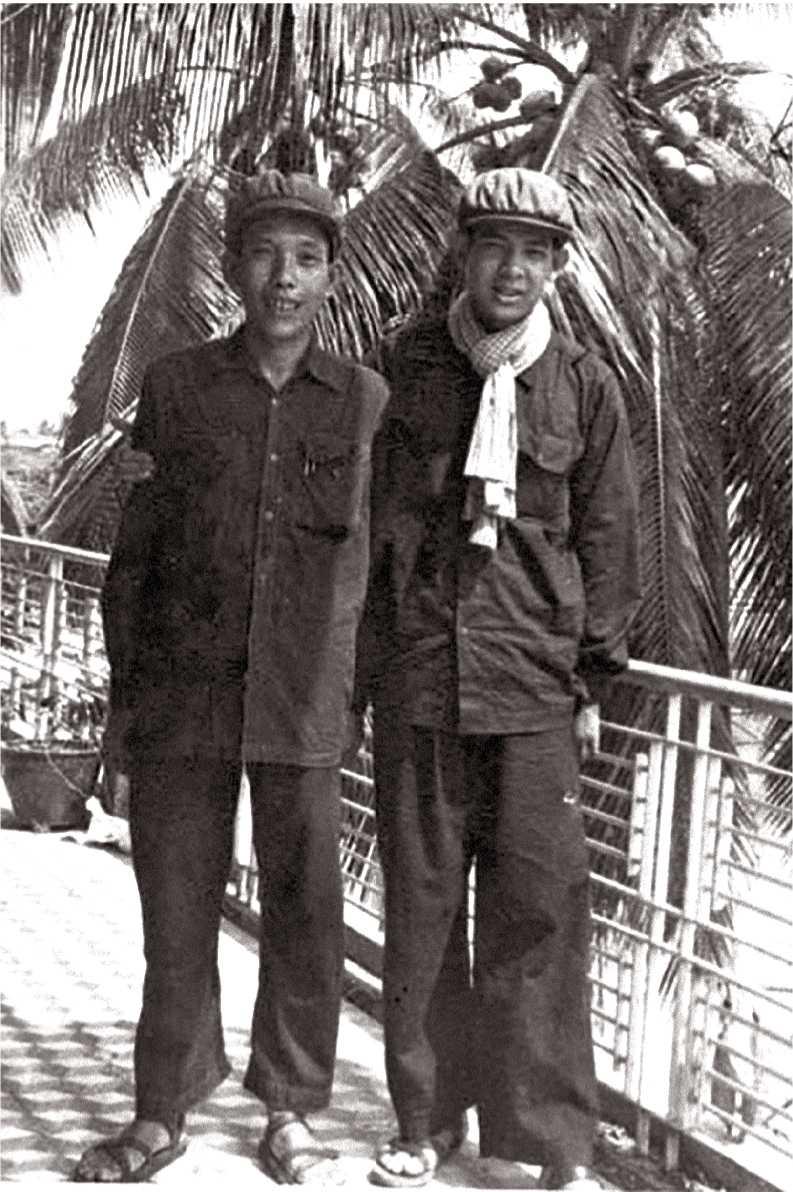

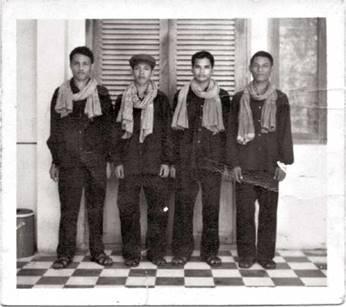

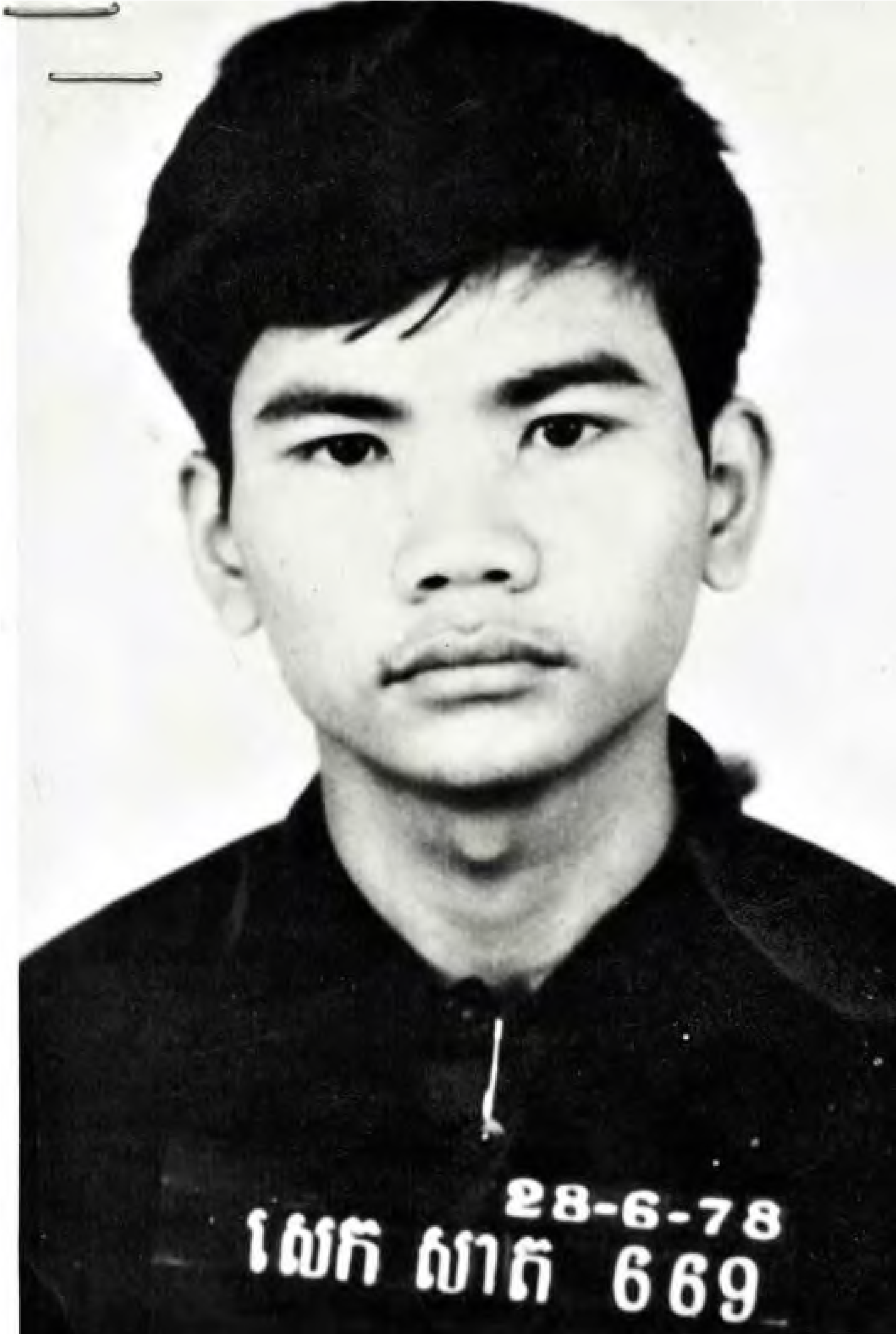

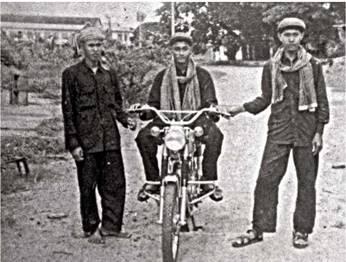

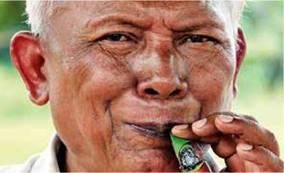

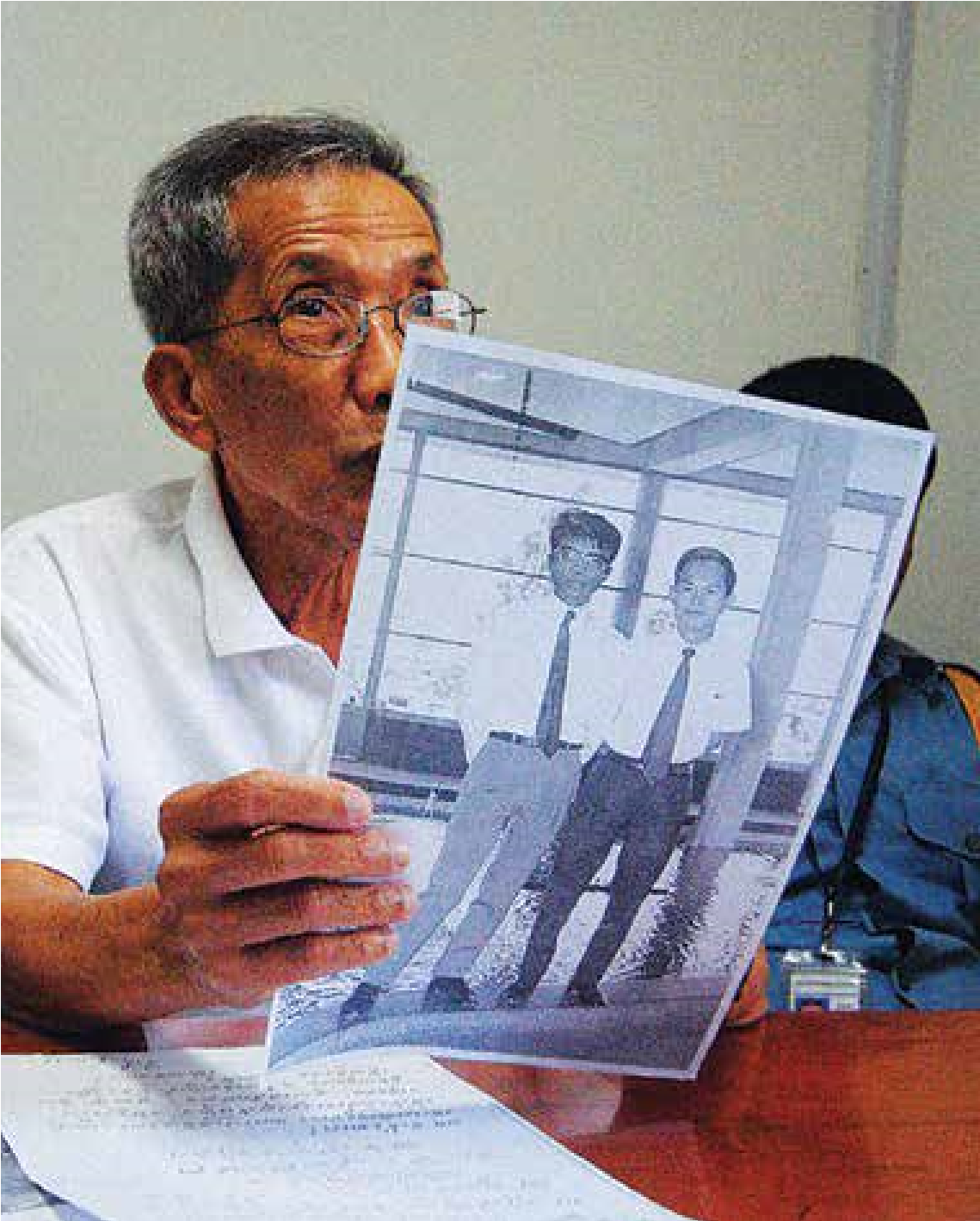

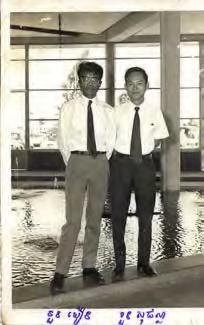

The photo belongs to San Sok who joined the [Khmer Rouge] revolution in 1972.

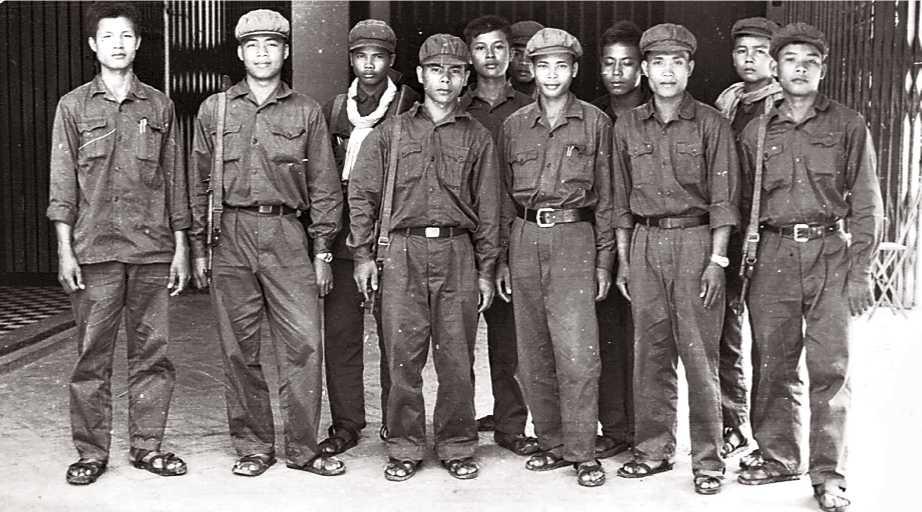

From left to right: Ol, Im, Pheng, Or, Nhep (Sok), San Sok, Phlouch. They were responsible to evacuate the people for Prey Kabas district, (District 55), Takeo province, 1972.

(San Sok Collection/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Second Edition

Christopher Dearing, Pheng Pong-Rasy, Sopheak Pheana

This new edition includes a significant reorganization of chapters to explain new historical facts and stories, as well as to address new chapters related to post-genocide justice. The authors re-organized chapters 3 and 4, which discuss the beginning of the Khmer Rouge regime. These chapters incorporate new information about the forced movement of peoples in Cambodia and they include excerpts of eye-witness accounts of this history with a particular focus on the suffering of the Cambodian people. Using information from the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) Judgment in Case 002, as well as testimony offered by Civil Parties, these chapters will provide a more detailed account on what happened during the early period of the Khmer Rouge regime.

The authors also included new chapters addressing the establishment and operation of the ECCC. Chapter 13 addresses the establishment, organization, and jurisdiction of the ECCC, with a focus on both the circumstances that led up to the ECCC’s establishment as well as the key legal concepts and principles that make up the ECCC’s mandate and normative rules. The chapter also provides a basic overview of the key components, officials and stakeholders in the ECCC’s work. Chapter 14 provides an overview of the four cases of the ECCC, with a summarized description of the alleged crimes, the circumstances of the accused, and any significant judgments and/or sentences rendered up to the date of publication. Chapter 15 provides excerpts of one of the accused’s apologies to victims, the court, and the public, and chapter 16 provides brief excerpts of different testimonies by victims, survivors, and witnesses at the ECCC.

The new chapters addressing the establishment, work, and testimony presented at the ECCC are a critical part of the story of the Cambodian nation’s struggle to confront its past. The work of the ECCC may have principally focused on the criminal prosecution of senior leaders and those most responsible for the crimes committed during the Khmer Rouge regime, but the court’s work has been significant in many other ways that influenced the Cambodian people’s struggle with this history. The ECCC’s judgements helped the Cambodian people and the world come to a better understanding of what led up to and ultimately occurred during the Khmer Rouge regime, and the ECCC’s rules, procedures, and decisions became reference points for improving how the rule of law is practiced and understood in Cambodia.

Finally, the court offered a sense of closure. Closure in this sense, does not mean compensation, reconciliation or reparations (at least on an individual level). Closure is a process that will have a different definition relative to each individual survivor or loved one’s circumstances, and collectively, it can take generations. The ECCC’s work was never expected to achieve national or collective closure, but we should acknowledge its work in supporting the process for closure. This book is dedicated to supporting closure through the memorialization and education of this history for the youth today and the generations to come.

Abbreviations and Terms

| Angkar Padevat | The leaders of the Communist Party of Kampuchea |

| CGDK | Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea |

| CIA | U.S. Central Intelligence Agency |

| CPK | Communist Party of Kampuchea |

| DK | Democratic Kampuchea |

| ICP | Indochinese Communist Party |

| KGB | Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti (Soviet Secret Police) |

| KPNLF | Khmer People’s National Liberation Front |

| KR | Khmer Rouge |

| KPRP | Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party |

| PRK | People’s Republic of Kampuchea |

| RGC | Royal Government of Cambodia |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNTAC | United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia |

| WPK | Workers’ Party of Kampuchea |

Chapter 1

Summary

“Khmer Rouge” was the name King Norodom Sihanouk gave to his communist opponents in the 1960s.[1] Their official name was the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), which took control of Cambodia on April 17, 1975.

The CPK created the state of Democratic Kampuchea in 1976 and ruled the country until January 1979. The party’s existence was kept secret until 1977, and no one outside the CPK knew who its leaders were (the leaders called themselves “Angkar Padevat”).

A few days after they took power in 1975, the Khmer Rouge forced perhaps two million people in Phnom Penh and other cities into the countryside to undertake agricultural work. Thousands of people died during the evacuations.

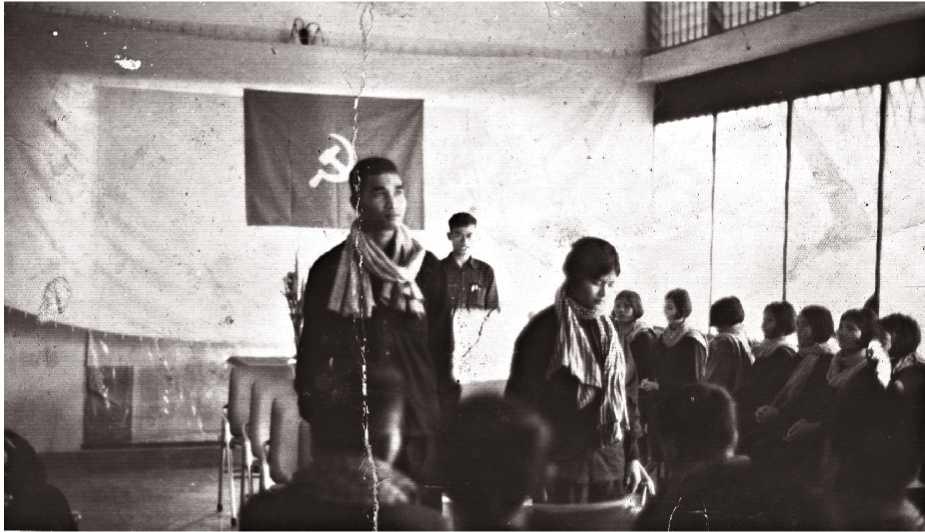

The Khmer Rouge also began to implement their radical Maoist and Marxist-Leninist transformation program at this time. They wanted to transform Cambodia into a rural, classless society in which there were no rich people, no poor people, and no exploitation. To accomplish this, they abolished money, free markets, normal schooling, private property, foreign clothing styles, religious practices, and traditional Khmer culture. Public schools, pagodas, mosques, churches, universities, shops and government buildings were shut or turned into (security centers) prisons, stables, reeducation camps and granaries. There was no public or private transportation, no private property, and no non-revolutionary entertainment. Leisure activities were severely restricted. People throughout the country, including the leaders of the CPK, had to wear black costumes, which were their traditional revolutionary clothes.

Under Democratic Kampuchea, everyone was deprived of their basic rights. People were not allowed to go outside their cooperative or assigned area. The regime would not allow anyone to gather and hold discussions. If three people gathered and talked, they could be accused of being enemies, resulting in their arrest and execution.

Family relationships were also heavily criticized. People were forbidden to show even the slightest affection, humor or pity. The Khmer Rouge asked all Cambodians to believe, obey and respect only Angkar Padevat, which was to be everyone’s “mother and father.”

The Khmer Rouge claimed that only pure people were qualified to build the revolution. Soon after seizing power, they arrested and killed thousands of soldiers, military officers and civil servants from the Khmer Republic regime led by Marshal Lon Nol. These groups of people were regarded as “impure.” Over the next three years, they executed hundreds of thousands of intellectuals; city residents; minority people such as the Cham, Vietnamese and Chinese; and many of their own soldiers and party members, who were accused of being traitors.

Secrecy was central to the operations of Democratic Kampuchea. The Khmer Rouge had a slogan: “Secrecy is the key to victory. High secrecy, long survival.”

Under the terms of the CPK’s 1976 four-year plan, Cambodians were expected to produce three tons of rice per hectare (and sometimes even higher yields) throughout the country. This meant that people had to grow and harvest rice all twelve months of the year. In most regions, the Khmer Rouge forced people to work more than twelve hours a day without rest or adequate food.

By the end of 1977, clashes broke out between Cambodia and Vietnam. Tens of thousands of people were sent to fight and thousands of them were killed.

In December 1978, Vietnamese troops and the forces of the United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea fought their way into Cambodia. They captured Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979.

The Khmer Rouge leaders then fled to the west and reestablished their forces in Thai territory, aided by China and Thailand. The United Nations (U.N.) voted to give the resistance movement against communists, which included the Khmer Rouge, a seat in its General Assembly. From 1979 to 1990, the U.N. recognized Democratic Kampuchea as the only legitimate representative of Cambodia.

In 1982, the Khmer Rouge formed a coalition with Prince Sihanouk and the non-communist leader, Son Sann, to create the Triparty Coalition Government. In Phnom Penh, on the other hand, Vietnam helped to create a new government—the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK)—led by Heng Samrin.

The Khmer Rouge continued to exist until 1999 when all of its leaders had, by this time, defected to the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC), or they were arrested or had died. But their legacy remains. Under Democratic Kampuchea, nearly two million Cambodians died from diseases due to a lack of medicines and medical services, starvation, execution, or exhaustion from overwork.[2] Those who lived through the regime were severely traumatized by their experiences.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Arch

Chapter 2: Who Were the Khmer Rouge? How Did They Gain Power?

1. The Early Communist Movement

The Cambodian communist movement emerged from the struggle against French colonization in the 1940s. In April 1950, during the First Indochina War,[3] 200 delegates assembled in Kampot province and formed the communist-led Unified Issarak Front, known as the Khmer Issarak. This group cooperated with Vietnam in struggling against the French.

The Front was led by Son Ngoc Minh (A-char Mien). He was a lay official at Unnalaom Pagoda. Chan Samay was the Front’s deputy and Sieu Heng was its secretary. Almost all of the Front’s members were Cambodians who spoke Vietnamese. Some of them became members of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP), which was created in Vietnam.[4] Most of the Front’s new members were peasants drawn to the revolutionary cause. Others were nationalist students who became communists while studying abroad.

Some of these students would later become leaders of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). They included Saloth Sar(Pol Pot), Son Sen, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary. These men saw peasants and poor people throughout the world as enslaved and repressed by capitalism and feudalism. They thought a Marxist-Leninist revolution was the only way Cambodia could attain independence and social equality.

2. The Creation of the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (Kprp)

In 1951, as fighting against the French intensified in Indochina, the Vietnamese communists guided the formation of the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party.[5] The members of its secret Central Committee were:

-

Son Ngoc Minh held the top position

-

Sieu Heng was in charge of military affairs

-

Tou Samouth (also known as A-char Sok, a former Buddhist monk from Kampuchea Krom) took charge of ideological training.

-

Chan Samay was in charge of economic matters.

When the first Indochina War ended in 1954, French forces withdrew from Indochina and Viet Minh[6] combatants withdrew from Cambodia. However, some Vietnamese military personnel and advisors remained in Cambodia. Concerned about the revolution’s security when the political system changed, Sieu Heng, Chan Samay and over a thousand KPRP cadres and activists fled to Vietnam, where theyjoined Son Ngoc Minh and others who had gone there earlier.

Sieu Heng soon returned to Cambodia accompanied by Nuon Chea (a member of the ICP who had been trained in Thailand and Vietnam) and other senior cadres. With the party’s leader Son Ngoc Minh in Hanoi, the KPRP was run by a temporary Central Committee. Sieu Heng was secretary and Tou Samouth was his deputy. Nuon Chea ranked number three and So Phim (who became chief of the East Zone during Democratic Kampuchea) was the fourth member. The management of the party was in the hands of a Vietnamese cadre, Pham Van Ba, who lived in Cambodia and claimed that Vietnam should continue to control Cambodian communist movements.

Tou Samouth took charge of the organization’s activities in urban areas, assisted by Nuon Chea and Saloth Sar (otherwise known as “Pol Pot”), who had recently returned from studying in France. The communists in Phnom Penh used Pol Pot as their link to establish a legal party called the People’s Party. This party contested the 1955 national election promised by the Geneva Agreements.[7] It was chaired by Keo Meas, a protege of Tou Samouth.

Pol Pot helped to formulate the party’s statutes and political program. He also made connections with the Democrat Party, which would compete with Prince Sihanouk’s newly established Sangkum Reastr Niyum (the People’s Socialist Communist Party) in the 1955 election. Pol Pot believed that the Democrats, who had anti-feudalist and anti-capitalist tendencies, would win the election and give the communists some political influence.

However, Pol Pot miscalculated badly. The Sangkum Reastr Niyum won all the seats in the National Assembly, while the People’s Party won only 3%. Sieu Heng soon came to believe that the communist cause in Cambodia was hopeless, for nearly everyone strongly supported Prince Sihanouk’s political programs rather than the idea of revolution. Moreover, some Issarak movements gave up their resistance and joined with Prince Sihanouk’s government.

In 1956, Sieu Heng secretly contacted the Prince’s Army Chief of Staff, Lon Nol, who offered him guarantees of safety. In 1959, Sieu Heng defected to the Sihanouk’s government, enabling authorities to pinpoint and arrest many clandestine KPRP cadres. According to Pol Pot, from 1955 to 1959, about 90 percent of the KPRP’s members were arrested and killed. By the beginning of 1960, only about 800 cadres remained active and only 2 rural party branches were still functioning fully:

-

The East Zone with its base in Kampong Cham province (led by So Phim); and

-

The Southwest Zone with its base in Takeo province (chaired by Chhit Choeun alias Ta Mok).

Tou Samouth, Pol Pot and Nuon Chea continued to run the party’s activities in Phnom Penh, with assistance from Ieng Sary and Son Sen, two other intellectuals educated in France.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

POL POT

(original name Solath Sar)

Pol Pot was born in 1925 (year of the ox) in Kampong Thom province. His father was a prosperous landowner. At the age of six, he went to live with his brother, an official at the Royal Palace. In Phnom Penh, he was educated at a series of French language schools and as a Buddhist novice.

In 1949, he was awarded a scholarship to study in Paris, but failed to obtain a degree. While in Paris, Pol Pot became a member of the French Communist Party and devoted his time to political activity.

Upon returning to Cambodia in 1953, he taught history and geography at a private high school and joined the clandestine communist movement. He married Khieu Ponnary in 1956. In 1960, he ranked number three in the then-Workers’ Party of Kampuchea. He was named its second deputy secretary in 1961 and party secretary in 1963. He later led the Khmer Rouge army in its war against the Lon Nol regime.

Pol Pot became prime minister of Democratic Kampuchea in 1976 and resigned in 1979, but remained an active leader of the Khmer Rouge.

He lived in exile, mainly in Thailand, until his death on April 15, 1998. His body was cremated on April 17, 1998.

NUON CHEA

(original name Runglert Laodi or Lao Kim Lorn, Nickname Khnuoch)

Nuon Chea was born in 1926 in Battambang province. In 1942, he attended high school in Bangkok, where he stayed in Benjamabopit Pagoda. In 1944, he studied law at Thammasat University in Bangkok, where he joined the Communist Party of Thailand.

He returned to Cambodia in 1950 and transferred his membership to the Indochinese Communist Party. He attended a training course in Hanoi in 1954 and returned home in 1955. He was elected deputy secretary of the WPK in 1960.

During Democratic Kampuchea, Nuon Chea was appointed president of the People’s Representative Assembly. He was also deputy secretary of the party’s Central and Standing Committees. He played a key role in security matters and as the second-highest party member, was responsible for enforcing the harsh policies laid down by the Standing Committee.

He went into exile on the Thai- Cambodia border in 1979 and defected with Khieu Samphan to the Royal Government of Cambodia after Pol Pot’s death in 1998. He was arrested in September 2007.

Over a decade later, Nuon Chea was tried by the ECCC, and he was found guilty of crimes against humanity, which was upheld by the Supreme Court Chamber in Case 002/01. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Nuon Chea was also found guilty by the Trial Chamber for crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and genocide of the Vietnamese and Cham people. He appealed to the Supreme Court Chamber, which has not ruled definitively on his appeal given his death on August 4, 2019.

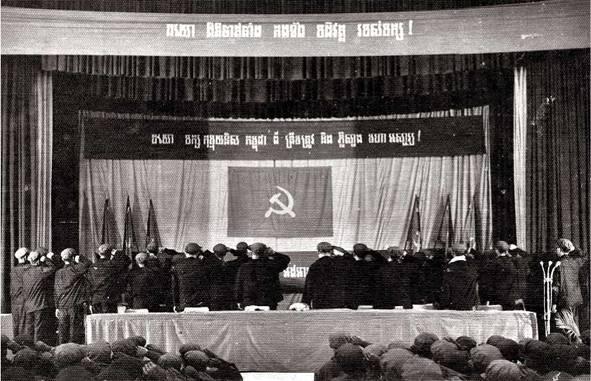

3. The Workers’ Party of Kampuchea (Wpk)

A secret KPRP congress was held on the grounds of the Phnom Penh railroad station on September 28-30, 1960. It was attended by seven members from the organization’s urban branches and fourteen members from its rural branches. The congress reorganized the party, set up a new political line, and changed its name to the Workers’ Party of Kampuchea (WPK). Tou Samouth became its secretary and Nuon Chea its deputy secretary. Pol Pot ranked number three at that time, and in 1961 he became the second deputy secretary.

After Tou Samouth disappeared in 1962, the party held an emergency congress in February 1963.[8] The congress elected Pol Pot as secretary. Nuon Chea, who had a higher position in the party, was not chosen as secretary because he was related by marriage to the defector Sieu Heng. Moreover, Nuon Chea was a loyal communist who wanted the WPK to be strong, so he did not compete with Pol Pot for the position. He remained deputy secretary and a powerful figure in the communist movement for over thirty years.

Soon after being named party secretary, Pol Pot took refuge at a Vietnamese military base in the northeast part of the country called “Office 100.” In 1965, he walked up the Ho Chi Minh Trail to Hanoi for talks with the North Vietnamese. He also visited China and North Korea. Pol Pot was treated more cordially in China than Vietnam and resented the idea that his party had to continue to be subservient to Vietnam.

4. The Communist Party of Kampuchea (Cpk)

In September 1966, after coming home, Pol Pot changed the party’s name to the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) because he wanted to lessen Vietnamese influence and strengthen relations with China. The Central Committee at this time consisted of Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Vorn Vet (a former teacher at Chamroeun Vichea High School in Phnom Penh), and Son Sen.

During the late 1960s, the CPK(whom Prince Sihanouk had dubbed the Khmer Rouge) gained more new members. Many of them lived along the Vietnamese border in remote areas out of the reach of the Prince’s armed forces. The party’s headquarters from 1966 to 1970 was in Ratanak Kiri province.

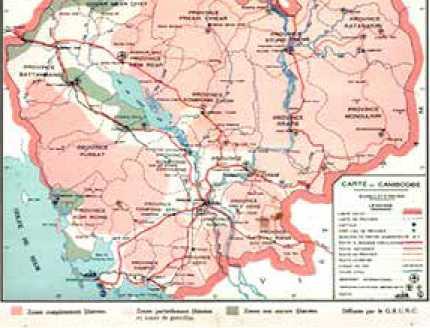

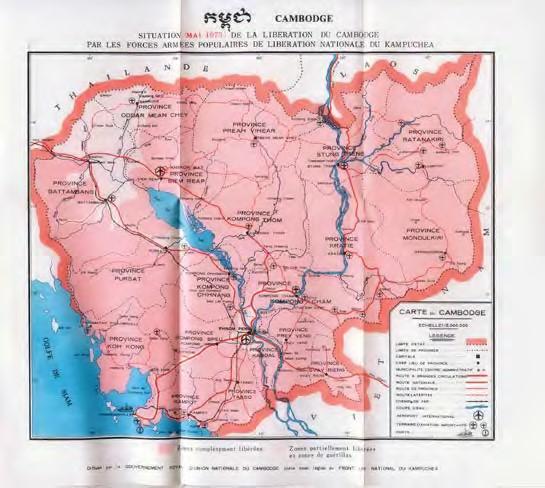

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

In March 1970, Marshal Lon Nol and his pro-American associates staged a successful coup to depose Prince Sihanouk as head of state. Soon after, the Viet Minh and Khmer Rouge gained control over much of the country. Tens of thousands of people refused to support the American-backed government—Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic—and joined the Khmer Rouge to help restore Prince Sihanouk to power. At this time, Prince Sihanouk went into exile in China. With the encouragement and support of China, North Vietnam and the CPK, he formed a National United Front of Kampuchea and a government in exile called the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea.[9] Members of the CPK were members of this government.

These developments created opportunities for the Khmer Rouge. North Vietnam and China supported them, and Prince Sihanouk appealed to the Cambodian people to run into the marquis (forests) to help overthrow the Lon Nol government. And the heavy bombing of communist supply lines and bases by the Khmer Republic government, with assistance from the U.S., created more support for the Khmer Rouge, whose armed forces were increasing in number.

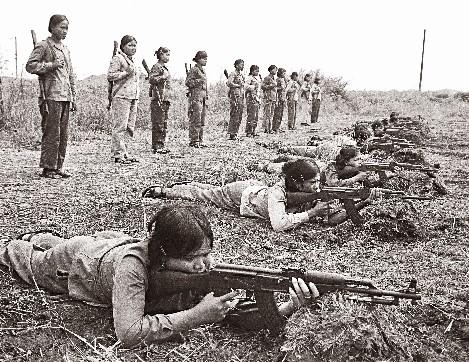

Vietnamese communist forces moved deep into Cambodia in 1970 and worked with the Khmer Rouge to recruit and train soldiers for the insurgent army, which grew from about 3,000 soldiers in 1970 to over 40,000 soldiers in 1973. Aided by the Vietnamese, the Khmer Rouge began to defeat Lon Nol’s forces on the battlefields. By the end of 1972, the Vietnamese withdrew from Cambodia and turned the major responsibilities for the war over to the CPK, although several thousand Vietnamese remained behind as technical advisors.

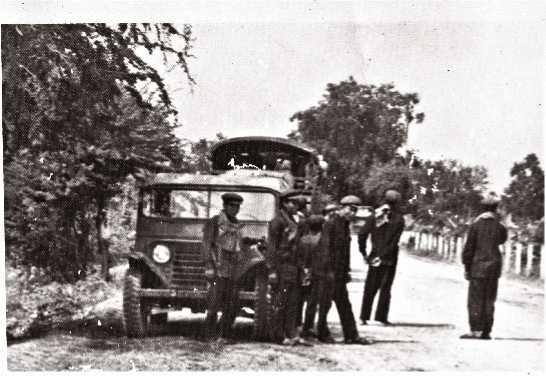

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

(General Les Kosem Collections/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

From January to August 1973, the Khmer Republic government, with assistance from the U.S., dropped about half a million tons of bombs on Cambodia, which may have killed as many as 300,000 people. The bombing postponed the Khmer Rouge victory, while many who resented the bombings or had lost family members joined their revolution.

Khmer Rouge soldiers were more active and disciplined than those of the Khmer Republic government, and they were able to withstand shortages of food and medicine. Moreover, some “Khmer-Hanois”[10] returned to Cambodia to assist the Khmer Rouge. These men and women were given junior positions throughout the country, but by 1973, after most of the Vietnamese advisors had returned home, they were secretly assassinated under orders from the CPK leadership, who wanted the party to be free of Vietnamese influence.

By early 1973, about 85 percent of Cambodian territory was in the hands of the Khmer Rouge, and the Lon Nol army was almost unable to go on the offensive. However, with U.S. assistance, it was able to continue fighting the Khmer Rouge for two more years.

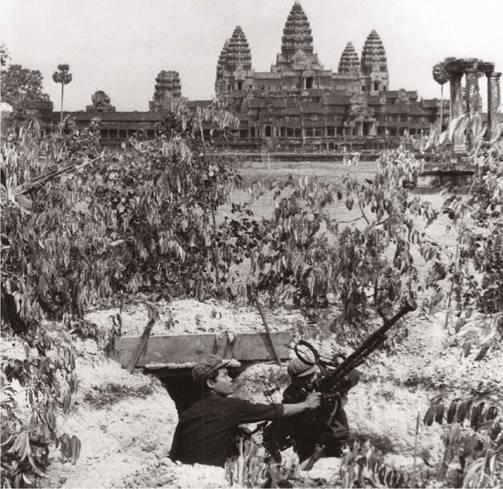

(Roland Neveu/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Chapter 3: The Khmer Rouge Come to Power

THE EVACUATION OF CITIES, FORCED TRANSFER AND THE MASSACRE AT TUOL PO CHREY

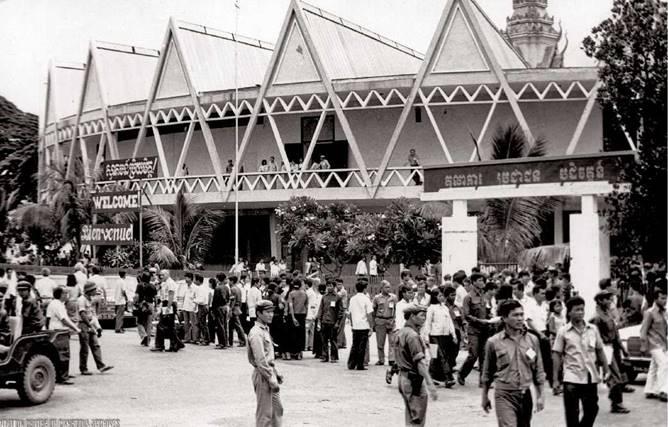

1. The Khmer Rouge March Into Phnom Penh

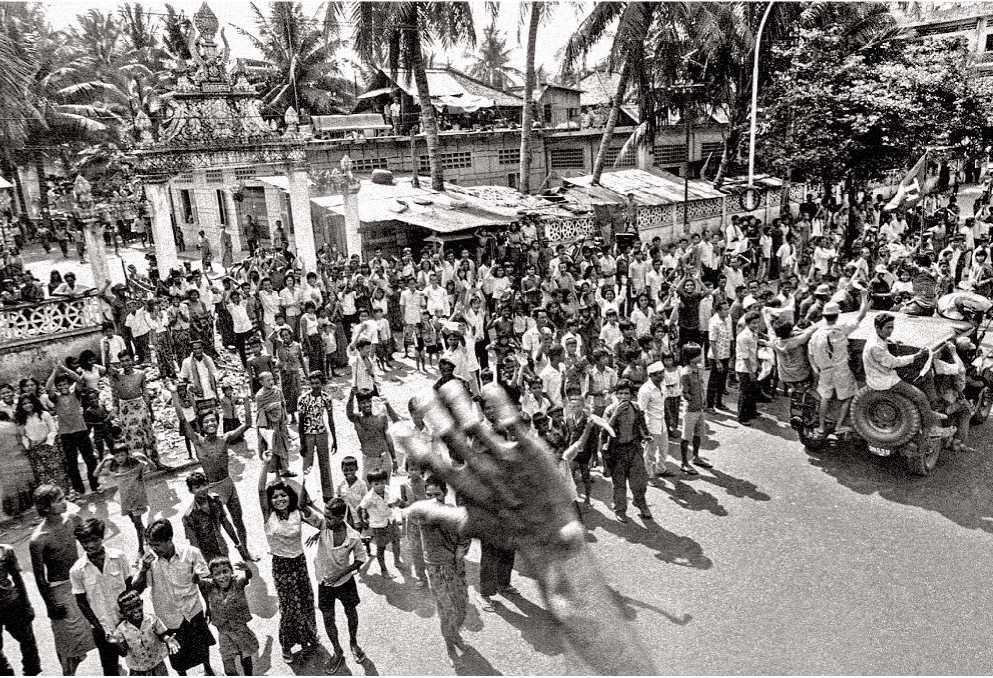

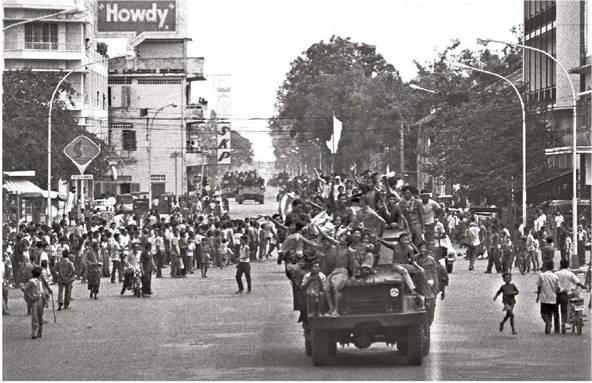

April 17, 1975, ended five years of foreign interventions, bombardment, and civil war in Cambodia. On this date, Phnom Penh fell to the communist forces.

(Roland Neveu/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Black and green-uniformed rebels entered the capital from every direction. The city’s people crowded on the roads, cheering and waving white cloths. However, many people hid in their houses for fear that they would be arrested or shot, for the Khmer Rouge soon declared over the radio that they did not come to talk to anybody and would execute high-ranking officials and military commanders from the former government.[11]

Hundreds of foreigners and some Cambodians sought refuge in the Hotel Le Phnom (now Hotel Le Royale), which the International Red Cross had declared as a neutral zone. But when the Khmer Rouge invaded the hotel, foreigners, journalists, and perhaps a hundred Cambodians fled to the French Embassy. The Khmer Rouge ordered the Cambodian nationals taking shelter there to go to the countryside to work as peasants. Some 610 foreigners spent two more weeks in the embassy before they were taken to the Thai border by truck.

Soon after liberating Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge executed three senior leaders of the Khmer Republic government and hundreds of other officials and military officers. The three leading figures were Prime Minister Long Boret, Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, and Lon Nol, brother of Lon Nol, who had left the country earlier with U.S. $1,000,000 as a pension. The United States had offered to take these three men to the U.S., but they refused to leave. Prince Sirik Matak wrote a letter to the U.S. Embassy:

I thank you sincerely for your letter and your offer to transport me to freedom. I cannot, alas, leave in such a cowardly fashion. As for you, and in particular your great country, I never believed for a moment that you would have the sentiment of abandoning a people which have chosen liberty. You have refused us protection and we can do nothing about it... I have only committed the mistake of believing in Americans. Please accept, Excellency, my dear friend, my faithful and friendly sentiments.

2. The Evacuation of the Cities

Most of the people in Cambodia’s cities believed they would live in peace under their new rulers, and that everyone would work together to reconcile the country. But a few hours after they captured Phnom Penh, Khmer Rouge soldiers began firing into the air as a signal to leave town. Residents were notified—very often at gunpoint—that they had to leave their homes immediately. Many of those residents with cars attempted to drive out of the city, but with little access to fuel, vehicles were soon abandoned in heavy traffic or confiscated by Khmer Rouge soldiers.

The movement out of Phnom Penh in April 1975 was chaotic, terrifying, and by force. People were told that they had to leave their homes without exception. Scattered fighting between Lon Nol and Khmer Rouge forces

(Roland Neveu/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

continued amidst the mass exodus, cutting off whole sections of the city and preventing family members from leaving the city together. And everywhere one walked one saw dead bodies and abandoned property. Checkpoints were set up intermittently to identify former Lon Nol soldiers and officials. Many people had to hide their identity because they feared arrest.

The Lon Nol army was known to have executed many of its prisoners and the Khmer Rouge responded in kind. Anyone identified with the former regime was promptly arrested and executed. Intellectuals, people with wealth, and many people who appeared suspicious, were also taken aside and killed.

The Khmer Rouge forced about two million Phnom Penh residents, including over a million wartime refugees, into the countryside. Within a week, the people of Phnom Penh and other cities that had been controlled by the Khmer Republic government were moved to rural areas to do agricultural work.

There were no exceptions to the evacuation. Hospitals were emptied of their patients. Thousands of the evacuees, especiallythe veryyoung, old and sick, died while on the road. Many pregnant women died while giving birth with no medicine or medical services. Some children became separated from their parents. Most people had no idea of what was happening.

As one would expect, people asked the questions: “Where should we go?

What should we bring? And, when will we return?”

Photo by Roland Neveu. Source: The Fall of Phnom Penh: 17 April 1975

While the Khmer Rouge gave varying answers, the dominant reason provided by most soldiers was the Americans were going to bomb Phnom Penh so inhabitants had to leave. Another reason provided was that the Khmer Rouge had to cleanse the town of enemy forces. Most people were informed to pack lightly because they would return in three days. Many people believed this and they left with little food, water, or medicine.

Many people left their entire lives behind in Phnom Penh, carrying perhaps some jewelry, cash, or other valuables to use in the event that they needed supplies. No one had any idea about how long they were leaving their homes, and those who suspected it would be longerthan three days, certainly did not know it would be the last time they would see Phnom Penh (or their city or hometown) for the next three years.

The majority of residents who left the city were sent to villages outside the city, where they stayed and worked for several months. In many cases, they went to places where they had relatives or some other connections. After several months, the Khmer Rouge, again, forcibly moved people, often bytrucks and trains, to cooperatives that were being set up across the country.

The Democratic Kampuchea’s vice premier in charge of foreign affairs, Ieng Sary, laterjustified the evacuation in terms of the lack of facilities and transportation to bring food to the cities. Pol Pot, visiting China in October 1977, said that the evacuation was to break up an “enemy spy organization.”

After the evacuation, Phnom Penh became a “ghost city,” with only about 40,000 inhabitants. Those who remained were administrative officers, soldiers, and factory workers. The only shop in the city (Central Market) was a store that catered to diplomats. The Khmer Rouge isolated the country from the outside world. They did not allow any foreigners into the country and no Cambodians were allowed to leave.

A few days later, after Pol Pot and other CPK officials entered Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge held a ceremony to pay homage to those who had died during the war. In Beijing, more than 100,000 people and many Chinese leaders celebrated the victory of the communist forces over the U.S.-backed government.

However, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the figurehead leader of the insurgents, did not attend. He was at the bedside of his mother, Queen Sisowath Kossomak Neary Roth Serey Vattana, who was dying in Beijing. Prince Sihanouk had been in exile in Beijing since 1970, where the Chinese government had given him both political and emotional support, as well as a comfortable villa. The Prince later made a statement praising the Khmer Rouge victory.

3. Forced Transfer

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

The common purpose of the CPK was to implement rapid socialist revolution in Cambodia through a “great leap forward” and defend the Party against “internal and external enemies.” One major way of achieving this goal was the repeated movement of the population from towns and cities to rural areas, as well as from one rural area to another.

This policy of forcibly moving people from one location to another (i.e., forced transfer) without giving them advance warning, compensation, or any legal means to object, caused incredible suffering and strain on people and communities.

Over a period of forty-five months, the Khmer Rouge regime engaged in many forced transfers of people between regions. Families were broken up, husbands were separated from their wives, children were taken from their parents, and countless loved ones disappeared without a trace. Many members of the Lon Nol regime and many people who were suspected of having sympathy or association with the ‘enemy’ were arrested and executed.

The CPK policy of forced transfers sought to break apart the human relationships and institutions that had governed most of Cambodian life before the revolution. In addition to the Lon Nol government, these included the traditional family unit, religious organizations, ethnic minority communities, and networks of intellectuals and business merchants. Without these relationships and institutions, it would be more difficult for opponents of the regime to mount an organized resistance. It would also be easier to convince Cambodians—especially children—to pledge loyalty to Angkar if forced transfers prevented them from being loyal to parents, ethnic kin, religious figures, or other traditional community leaders.

Overall, the regime orchestrated three general phases of population movement:

-

The movement of people out of cities, such as Phnom Penh, Battambang, Siem Reap, and a few other towns starting on April 17, 1975 (including six months later by train);

-

The movement of people within the countryside in the Central, Southwest, West, and East zones from late 1975 to other parts of Cambodia; and

-

The movement of people out of the East zone in 1977.

The forced transfer of so many people can be termed a tragedy for many, and the beginning of a new totalitarian era for all Cambodian people. As a consequence of their rural upbringing and their connections to the countryside, many people were able to obtain shelter with relatives and friends, which helped them avoid the worst aspects of the forcible transfer. To many other Cambodians, particularly those with an urban or middle/ upper-class background, the forcible transfer caused great suffering and thousands of deaths.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Throughout history, repressive governments have used forced transfers to expel unwanted populations or to weaken, punish, or control certain groups living in their territories. Forced transfers are prohibited by modern international law, however, because they violate people’s basic human rights, including the right to live in one’s home in safety and dignity. Governments may only transfer people from their homes when the people agree to move without undue pressure or, in some cases, when the government gives them fair financial compensation and a chance to challenge their transfer in a sound legal process. The mass program of forced transfer in Democratic Kampuchea offered victims no compensation and no opportunity forjustice. There is no doubt among legal experts that it was illegal.

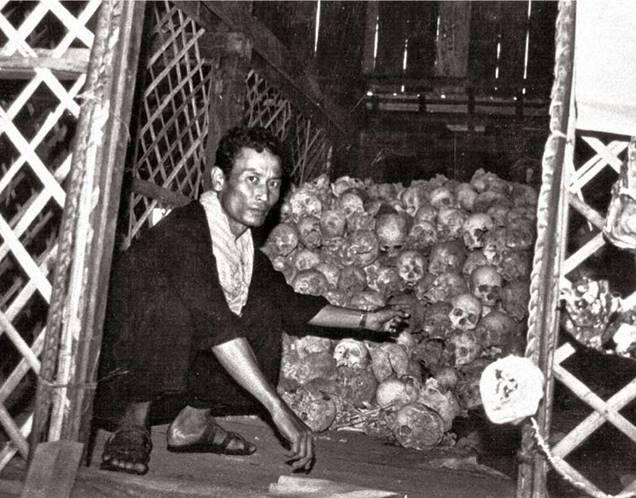

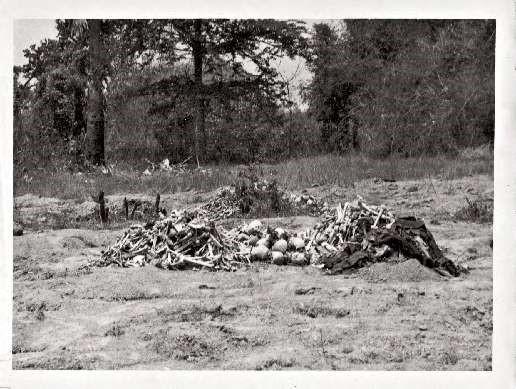

4. Tuol Po Chrey

In 1975, Tuol Po Chrey was a big, open field close to the Tonle Sap river and next to a swampy forest. In April 1975, however, it became known as an infamous killing site for thousands of Lon Nol soldiers and civilians. It was the site of one of the worst massacres during the period of the first major forced transfers in Democratic Kampuchea, when the Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and “screened out” former Lon Nol officers and sympathizers.

On April 17, 1975, the Lon Nol army in Pursat had received an instruction overthe national radio from Phnom Penh to disarm. By April 19, the Khmer Rouge took control of Pursat province. Shortly thereafter, the Khmer Rouge brought Lon Nol soldiers by truck to the provincial town office to meet with Khmer Rouge leaders. The meeting lasted three or four hours, and as many as five hundred soldiers and civil servants attended.

At the meeting, the Lon Nol soldiers were given political indoctrination training in preparation of meeting Angkar the next day. The Khmer Rouge also urged residents in the provincial town of Pursat to leave. The Lon Nol soldiers were informed that they would be sent to training sessions and to meet Prince Sihanouk. They were also told that they would resume their former ranks after the training. Meeting attendees included Lon Nol military officers with the ranks of second lieutenant, captain, and up to general. After the meeting, the Lon Nol soldiers seemed happy, chatting with relatives while waiting, telling them they were going to study and meet with the King.

According to testimony by Mr. Sat Lim, following the Khmer Rouge meeting, Lon Nol soldiers were returned to the trucks that brought them to the meeting, and were driven in the direction of TPC. According to another person, Mr. Ung Chhat, it appeared that Lon Nol soldiers boarded the trucks voluntarily. At the Po village fort, the Khmer Rouge had set up checkpoints to prevent people from traveling to the area. The Khmer Rouge only allowed one car at a time to enter the fort.

Vehicles full of Lon Nol soldiers left the Po village fort, one by one, about every 20 minutes. Some reports claimed that the trucks contained Lon Nol soldiers and civil servants. The Khmer Rouge would not allow the next vehicle to leave for TPC until they saw the previous one return. Villagers noted that the Lon Nol soldiers seemed relaxed on the trucks on the way to the site, as they had been told they would be meeting Angkar and the King. The vehicles, however, returned empty. Villagers reported hearing gunfire and artillery shells near the village. Lon Nol soldiers sent to TPC had been executed. It is unclear how many Lon Nol soldiers were killed at TPC, and estimates range from as low as 2,000 soldiers to as high as 8,000.

The Tuol Po Chrey execution site was operational intermittently from late 1975 until about 1977, during which time large-scale killings of the ex-military and civilian population were carried out.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Chapter 4: The Khmer Rouge Come to Power

VOICES FROM CIVIL PARTIES AND SURVIVOR ACCOUNTS

1. Voices From Civil Parties to the Eccc and Other Survivor Accounts on the Forced Transfer of Populations

Ms. Yim Sovann, a civil party to the ECCC proceedings in Case 002, described the forced transfer of people out of Phnom Penh:

It was at about 3 p.m., and her father initially refused to leave. “They came with rifles and some dry rice, and they told my father: ‘You must leave, or the Americans will drop bombs on Phnom Penh.’ My father rushed to pack our bags and collect some rice before moving out of our place. It was very miserable to leave.”

Ms. Sovann also recalled, “They were all armed - men and women. They wore black uniforms with red scarves. They told her family that the ‘upper Angkar’ had asked them to leave and they must go to their home village for three days or else the Americans might drop bombs and kill them. The soldiers only gave us fifteen minutes to leave and if we refused, measures would be taken.”

She described witnessing soldiers shoot a lock off a house door in O’Russey market and then the soldiers shot the people as they ran out of the house. She also saw wounded Lon Nol soldiers at a military hospital in Borei Keila, which belonged to the Lon Nol army.

The Khmer Rouge soldiers pushed them off their beds. Some of the wounded were taken by their relatives, but others were left behind to die.

Nobody who died during the evacuation was given a funeral. The bodies were merely put into a ditch or left on the road.

Mr. Chhum Sokha, a civil party to the ECCC in Case 002 testified on his family’s journey out of Phnom Penh:

Sokha described seeing dead bodies along the roadside illuminated by the headlights of vehicles and smoke-damaged houses and burned bodies around Pochentong Airport and in front of the transport department.

Mr. Sokha explained that he, his mother, sister, uncle, and grandparents went ahead on foot and his father and uncle caught up with them after about two kilometers. His father told him he was to be detained but noticed people tied up in a line, so he fled, telling the family to hurry, Mr. Sokha testified. He described how the family rested at Ang Krouch pagoda for several days because his younger sister had swollen legs and could not walk, and they were later told by Angkar that they were permitted to return to their native village, which was Tbong Kdey village in Prey Veng province.

The civil party explained that his sister still had problems with her legs, so his mother exchanged jewelry and good clothes to allow his sister to travel on a cart. The family then reached a village near a lake in Bati, where they stayed overnight before proceeding to Boeung Khchak village.

After about a month of travelling from Phnom Penh, Mr. Sokha testified, the family reached Tbong Kdey village in Prey Veng province—the family’s hometown.

Sim Soth, aka Koy, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime, was a cyclo driver in Phnom Penh during its evacuation. Koy recalled what he saw during the evacuation:

On April 17, 1975, I went out to earn a living as usual. A few hours later, I witnessed Khmer Rouge soldiers entering Phnom Penh. People came out, waving white cloths and white shirts, welcoming the Khmer Rouge. Suddenly, they fired into the air, ordering people to leave the town, alleging there would be American bombing. Like other people, I hastily departed at 10 o’clock with my brother, my colleagues from the pagoda and the monks. On the crowded road, I heard the voices of people asking for their parents and relatives, and the voices of hungry children asking for food. The Khmer Rouge confiscated people’s belongings. Those people who refused would be killed or taken away. While I was walking, a female Khmer Rouge soldier grabbed my collar and asked if I was a soldier. She pushed me backward when I told her I was a student. I continued my journey to Takhmau. On the way, I saw a lot of recently swollen dead bodies. After three days of walking, I reached Takeo province.

(Mok Sin Heang Collection/ Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

So Ry of Takeo province also recalled the evacuation of Phnom Penh. Her husband was a Lon Nol soldier whose thigh was injured while fighting the Khmer Rouge. He was sent to a hospital in Phnom Penh.

The Khmer Rouge soldiers asked us to leave town. I said, “I cannot go because I am pregnant and my husband is seriously injured.” They forcibly insisted that we had to go. We were crying a lot because my husband could not walk. Then we found a horse cart, so I carried my husband on to the cart. I tied the cart with my scarf, put the scarf around my neck and towed it. We wanted to go to Takeo, but the soldiers forced us to go forward on National Road 5. We passed Prek Kdam and stopped in order to cook rice. After eating, they told us to go forward. I towed the cart until my groin became inflamed. On the way, my husband was taken and killed.

I cried a lot, but I could do nothing. Finally, I arrived at Chamkar Leu district, Kampong Cham province. One month later, I gave birth to my daughter.

Mr. Lay Buny, a civil party to the ECCC in Case 002 also testified about the forced transfer out of Phnom Penh:

Khmer Rouge soldiers told people to leave by whatever means they had, Ms. Buny testified; they did not tell them what belongings to bring. Her family did not bring rice, she said; they only brought money, which they thought could be used along the way. She added that the Khmer Rouge soldiers did not tell her that money would be useless, and she “became hopeless” when she learned this en-route.

People who could not travel independently, like hospital patients, “would be pushed by a wheeled hospital bed or carried in stretchers or hammocks. Somebody who was seriously ill could also be carried on someone’s back while walking,” Ms. Buny explained. People gave birth along the wayside, and evacuees could hear their cries, she recalled, adding that the evacuees eventually found midwives to assist them.

Ms. Buny was forcibly transferred with her five-year-old daughter. As to the fate of the civil party’s five-year-old daughter, Ms. Buny recounted:

When we reached Ksach Kandal, my daughter had been ill for a few days already. She had severe diarrhea I was asked to pick some leaves for her to treat her illness. Every family member

got ill with fever ... When [my visiting aunt] saw this, she wanted to take my daughter to live with her so that she could be treated I agreed to let her go ... I believed that my daughter would be properly treated or taken care of, only to learn that she died.

Ms. Buny was also forced to move again from Ksach Kandal district to Pursat where she described the food as being bad. The evacuees “ate on the road [and the food] was not good for us, it was bad for our stomachs.”

2. A Voice From a Civil Party Doctor

Mr. Meas Saran was a doctor working in Phnom Penh in the days before the Khmer Rouge military victory over Lon Nol’s forces. He explains the situation shortly before the evacuation.

At Borey Keila at that time, I [Mr. Meas Saran] was working at a surgical center. There were five surgical sections that were meant to receive wounded people. This was the first place that the wound- ed people would be admitted to.

On April 16, there were bombs dropped at Duymex market. People got injured and were sent there. I cannot remember the number of patients, but each center kept receiving the wounded and the beds could not accommodate all the wounded, so we had to use the floor for further incoming wounded people

Some people were not seriously injured and they could move about. Some were injured at their legs, and indeed they could not walk and had to remain in bed. I could recall a seven-year-old child who was seriously injured. She told me that she got injured by a bomb. That child was lying on the ground. I couldn’t save that person when I was evacuated from the hospital.

On the morning of April 17, when we were told that we had to leave, the people who were in the hospital were told to walk out.” Some of the patients in beds had to be pushed.

Mr. Saran elaborated on how he felt about these events as a medical professional:

My mother told me to become a doctor, not a soldier. I dedicated my life to helping the patients, including the wounded Khmer Rouge soldiers. Two of them were treated by me. I, at the moment when I was asked to leave the city, had a difficult feeling, because at that time, I thought that the sick, the wounded, would be well-assisted during the evacuation, but at the same time, I was not clear in my mind as to whether these people would be properly treated. I could recall a girl who had been seriously injured begging me, asking me to help her out. I was helpless. I was obliged to help her as a doctor, but I couldn’t help her beyond what I could at that time.

Mr. Saran continued:

At that time, no Khmer Rouge medical staff or soldiers were there to take charge of the hospital. I didn’t know what happened after this, but during that time, it was sure that no one was there to assist the medical staff during the evacuation.

Mr. Saran went on to describe how he felt when he was forced to leave his patients.

In my capacity as a medical staff, it was my obligation. Frankly speaking, I felt uncomfortable to leave the patients behind. In my mind, if I left them behind, one, they would die, and two, if the Khmer Rouge would come to help them, they would survive. But the thing was, how could I assist them in my capacity? I couldn’t help them much. When I left, I left with an uneasy feeling ... and I was still thinking about my wife. I felt uneasy when I left, because I left the patients behind, in particular the young girl, and I am still haunted by her image.

Initially, we were instead to leave Phnom Penh for three days, and during these three days, it was so difficult while we were en-route. Then we crossed the Monivong Bridge. After the three days passed, there were still a large number of people on the other side of the bridge. I was still waiting for my wife, and I still had hope that I would be allowed to return after the three-day period. I was very worried about my wife as she was pregnant and she did not know Phnom Penh that well. After the three days passed, I was looking for my wife among the crowd of people who was still crossing the bridge. In the end, I became hopeless and I had to find any means to find my wife in her native village. After the three days passed, there was an announcement on the loudspeaker from Phnom Penh

appealing for officials to return to work in Phnom Penh. I saw some people returning to Phnom Penh. But those people went by themselves without members of their families and I did not see them return. With that, I thought something wrong happened in Phnom Penh, and I was concerned about that issue.

The doctor goes on to explain how he passed numerous checkpoints along the road to his wife’s village. He was questioned at each checkpoint, and he learned quickly to lie to the Khmer Rouge because he did not trust them.

Frankly speaking, I did not trust them. I did not trust them because I saw that people who were called to Phnom Penh never returned. I did not trust them because they talked about the imminent bombardment and that we had to be evacuated for three days only, but they lied. That did not happen. Of course, if people had been allowed to return, they would have survived. But that did not happen So ... I decided I had to lie to them.

Moving to events that occurred after he arrived at his wife’s hometown, Mr. Saran said:

When I arrived at that village, my mother-in-law cried because she did not see my wife. I myself was also disappointed as I did not see my wife.

3. Witnesses in the Eccc on the Massacre at Tuol Po Chrey

Mr. Sat Lim, a former Khmer Rouge soldier and witness in the ECCC in Case 002 testified about what he saw and heard when he was in the Tuol Po Chrey area in April 1975.

Mr. Sat testified that some 3,000 Lon Nol soldiers had been killed during the final Khmer Rouge attack on TPC of April 17, 1975. Mr. Sat noted that the Lon Nol soldiers surrendered by raising white flags at the TPC fortress. He believed there were about 100 soldiers wearing military clothing, and several commandoes in civilian dress. After they surrendered, they had their weapons taken away and were gathered into groups. Lon Nol soldiers were eventually transferred from the provincial town hall to TPC where they were killed.

Ms. Yim Sovann, a civil party in the ECCC in Case 002 testified about what she saw and heard when she was in the Tuol Po Chrey area in late 1976. Ms. Yim frequently passed by TPC commune in late 1976 and early 1977 to collect thatch. Villagers in Pursat told her that Lon Nol soldiers had been executed at TPC. Ms. Yim heard from the Khmer Rouge soldiers that Lon Nol soldiers, following instructions from Khmer Rouge soldiers, were loaded into a truck and were sent to TPC for execution in April of 1975. The villagers told Ms. Sovann that the killing took about “half a month”. She also saw a hill of mounded earth at TPC that she assumed to be a “cover up” and met people from Kbal Chhae Puk cooperative whose relatives had been killed there. She described the area as a big, open field close to the Tonle Sap river and next to the swamp forest. Ms. Yim noted that she did not know exact figures of how many Lon Nol soldiers had died at TPC, but that villagers had told her they saw a truckload of people sent to TPC. She noted that the villagers said it was not only Lon Nol soldiers; civil servants from the former regime were also gathered and sent to TPC for execution.

car at a time to get in there. I saw hundreds of the Khmer Rouge troops surrounding those Lon Nol soldiers. They also set checkpoints onsite to ban people from travelling through that area. I was stopped and searched by them, but since I had a permission slip, they let me through. While I was there, I saw them letting a vehicle leave that place one by one in about every 20 minutes. The Khmer Rouge would not allow the next vehicle to leave for Tuol Po Chrey unless they saw the previous one, which had transported Lon Nol soldiers to Tuol Po Chrey earlier, returned. Later I saw the vehicle, which had transported Lon Nol soldiers there earlier return empty.”

Later, Mr. Ung went with two villagers to see the corpses inside the Tuol Po Chrey fort.

He reported that all of the soldiers’ bodies were on the ground with their heads pointing north, wearing civilian clothes rather than military uniforms. The corpses were bound together by rope in groups of 15-20, with their arms tied behind their backs.

Mr. Sum Alatt, a former Lon Nol soldier and witness in the ECCC for Case 002 testified about what he saw and heard when he was in the Tuol Po Chrey area during April 1975. “In the meeting in the provincial town office, they educated us about the policy of reconciliation and about country building, and lastly, they spoke about placing our trust in going for the reception [to meet Angkar]. That was their approach so that we would trust them. In general, we did not know what was going to happen in the future but we all agreed to go for the reception.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Tuol Po Chrey was about 20 kilometers away. When we were gathered to go to Tuol Po Chrey—that is in the reception of Angkar—I personally agreed to go through but then the car that I traveled on was stopped half- way. So, in fact, I wanted to go on that car but because it was fully loaded, I was told to go in a later vehicle. So I, myself, did not reach Tuol Po Chrey. However, three days later, I heard that those people had been killed.

To recollect the event in terms of Angkar, we never heard of Angkar when we heard of the administrative side, so we were told that we would go and greet Angkar. And we wanted to meet Angkar because we hoped that after we reconciled with one another, then we would gather our strength to build the country but I never knew who Angkar was.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Chapter 5: The Formation of the Democratic Kampuchea Government

1. The Angkar [12]

Although the Khmer Rouge had fought against Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic for five years, very little was known about the movement or its leaders. The CPK maintained this secrecy for most of the time that it ruled Cambodia.

Angkar Padevat, “the revolutionary organization,” was made up of men and women who were members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea. They were led from the shadows by Pol Pot.

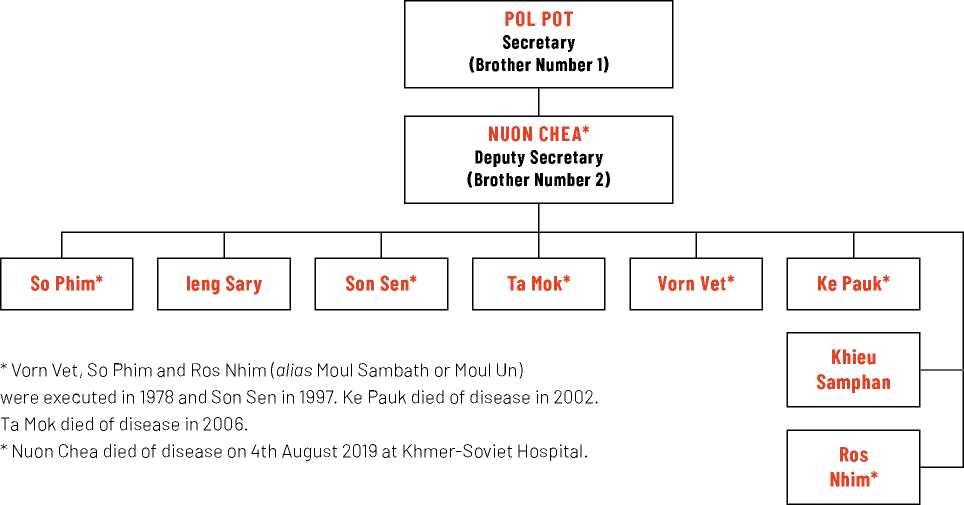

In September 1975, the CPK’s Central Committee comprised Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, So Phim, Ieng Sary, Son Sen, Ta Mok and Vorn Vet. In 1977, three other members (Nhim Ros, Khieu Samphan and Ke Pauk)were added to this committee. Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Son Sen and Khieu Samphan were educated in France, while Nuon Chea was educated in Thailand and Vietnam. The other members of the Central Committee, although literate, had less education.

MEMBERS OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE IN 1976-1978*

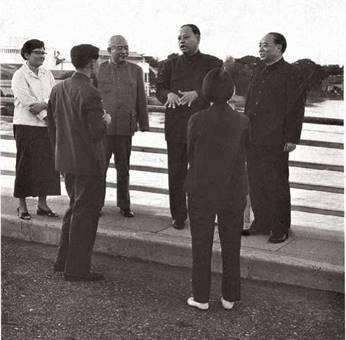

2. Prince Sihanouk Returns to Cambodia

Until the end of 1975 the Khmer Rouge called itself the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea (this was the organization that had been founded in Beijing in 1970 with Prince Sihanouk as head of state). By 1972, they controlled almost all the resistance, but for the sake of international recognition and internal support, they continued to operate behind the facade of Prince Sihanouk and his government in exile.

In July 1975, the Khmer Rouge invited the Prince, who was then living in exile in Pyongyang, North Korea, to come home. Before returning to Cambodia, he flew to Beijing to meet Chinese President Mao Zedong and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, who was in the hospital. He later said, “My decision to return to Cambodia did not express the fact that I agree with the Red Khmers, but I have to sacrifice myself for the honor of China and his Excellency, Zhou Enlai, who helped Cambodia and myself so much.[13] He returned with his wife in early September, accompanied by Pen Nuth (premier of the Royal Government of the National Union of Cambodia), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Thirith and some members of the royal family.

(Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Archives)

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

The Prince soon presided over a cabinet meeting, but was not allowed to speak. The communist rulers had given him the title of chief of state, which carried no power. Three weeks after his return, the Prince was sent to the United Nations to claim Cambodia’s seat at the General Assembly, inside the country, many of his supporters had vanished without a trace. About twenty members of Prince Sihanouk’s family died during Democratic Kampuchea, and at least seven other members of the royal family were executed at Tuol Sleng.

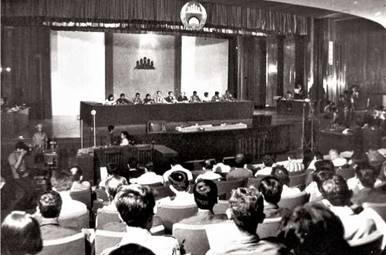

3. The Constitution

From December 15-19, 1975, the text of a constitution was approved by a 1,000-member National Congress in Phnom Penh and was promulgated on January 5, 1976. The country was officially renamed Democratic Kampuchea. The constitution established a 250-seat House of Representatives, with 150 members representing peasants, 50 members representing laborers and other working people, and 50 people representing the revolutionary army. The constitution said nothing about the CPK. The Assembly met only once in April 1976.

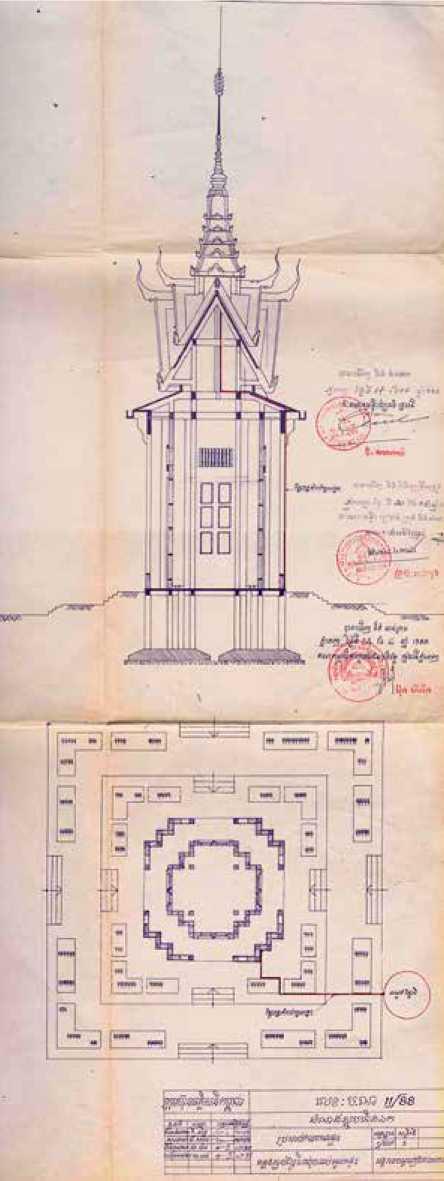

Article 16 of the DK Constitution describes the design and meaning of the national flag: The background is red, with a yellow, three-towered temple in the middle. The red background symbolizes the revolutionary movement, the resolute and valiant struggle of the Kampuchean people for the liberation, defense, and construction of their country.

The yellow temple symbolizes the national traditions of the Kampuchean people, who are defending and building the country to make it ever more prosperous. (Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA’S NATIONAL ANTHEM

17 APRIL, THE GREAT VICTORY

Glittering red blood which blankets the towns and countryside of the Kampuchean motherland! Blood of our splendid workers and peasants!

Blood of our revolutionary youth! Blood that was transmuted into fury, anger and vigorous struggle! On 17 April, under the revolutionary flag! Blood that liberated us from slavery!

Long life 17 April, the great victory! More wonderful and much more meaningful than the Angkar era! We unite together to build up Kampuchea and a glorious society, democratic, egalitarian, and just; independentmaster; absolutely determined to defend the country, our glorious land; Long life! Long life! Long life new Kampuchea, democratic and gloriously prosperous; Determine to raise up the revolutionary red flag to be higher; build up our country to achieve the glorious Great Leap Forward!

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

The new national anthem was called “17 April, the Great Victory.” Its words were written by Pol Pot. The new national flag was red with a yellow three-towered image of Angkor Wat in the middle.

(Julio Jeldres Collections/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

4. Prince Sihanouk Resigns as Head of State

On March 11, 1976, the CPK’s Standing Committee met to discuss the resignation of Prince Norodom Sihanouk. They agreed that they would accept his resignation, but they would not allow him to leave the country, to speak out, or to meet foreign diplomats. Cambodia’s monarchy, which had existed for nearly two thousand years, had ended.

In April 1976, the Kampuchean People’s Representative Assembly held its first and only session. The Assembly unanimously agreed to Prince Sihanouk’s retirement request, giving him an annual $8,000 pension that was never paid. He and his family were put under house arrest in a small villa in the Royal Palace compound.

Structure of the State of Democratic Kampuchea

The Prince remained there until January 1979, just before the collapse of Democratic Kampuchea.[14]

KHIEU SAMPHAN (aka comrade Hem)

Khieu Samphan was born in 1931 in Kampong Cham. After being awarded a scholarship to study in France, he finished his doctorate in economic science and returned home in 1959. The Prince Sihanouk appointed him Secretary of State for Commerce. In 1964, he resigned from his post, but remained in the National Assembly for four more years.

In 1967, accused of being a communist agent, Khieu Samphan went into hiding in the jungle. In 1976, after the resignation of Prince Sihanouk, he was appointed President of Democratic Kampuchea’s State Presidium. He joined Pol Pot in exile from 1979 to 1998, when he defected to the Royal Government of Cambodia. In November 2007, he was arrested.

Over a decade later, Khieu Samphan was tried by the ECCC, and he was found guilty of crimes against humanity, which was upheld by the Supreme Court Chamber in Case 002/01. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was also found guilty by the Trial Chamber for crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and genocide of the Vietnamese people. He appealed to the Supreme Court Chamber, which has not issued a judgment as of the date of this publication.

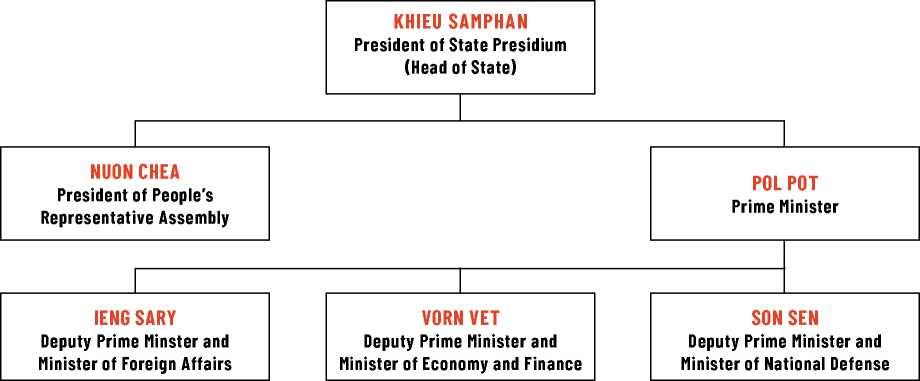

5. Organizational Structure of Democratic Kampuchea

The only active organization in Democratic Kampuchea was the concealed Communist Party of Kampuchea. The ministries with high volumes of work established in Phnom Penh included the Ministry of Foreign Affairs headed by Ieng Sary, the Minister of Defense under Son Sen, the Ministry of Industry led by Cheng An, and the Ministry of Economy chaired by Vorn Vet. The only committee that had the authority to make decisions and government policies and statutes was the CPK’s Standing Committee, with Pol Pot as the secretary and Nuon Chea his deputy. The CPK leaders never paid attention to the constitution or regulations that they themselves had adopted. Members of the Standing Committee and Central Committee also had ministerial responsibilities.[15]

6. Changing the Party’s Anniversary

In March 1976, the Central Committee decided to set the date of the CPK’s birth to 1960 rather than 1951. The leaders decided that anyone who joined the party before 1960 would no longer be considered as a party member. They did not want to admit the importance of Vietnamese guidance before 1960. They wanted to deny Vietnam’s influence on the party and to break any links with Vietnam.

The CPK continued to lead the country secretly under the name of Angkar. In September 1977, however, just before visiting China, Pol Pot publicly admitted the existence of the Communist Party of Kampuchea and his own position as the prime minister of Democratic Kampuchea.

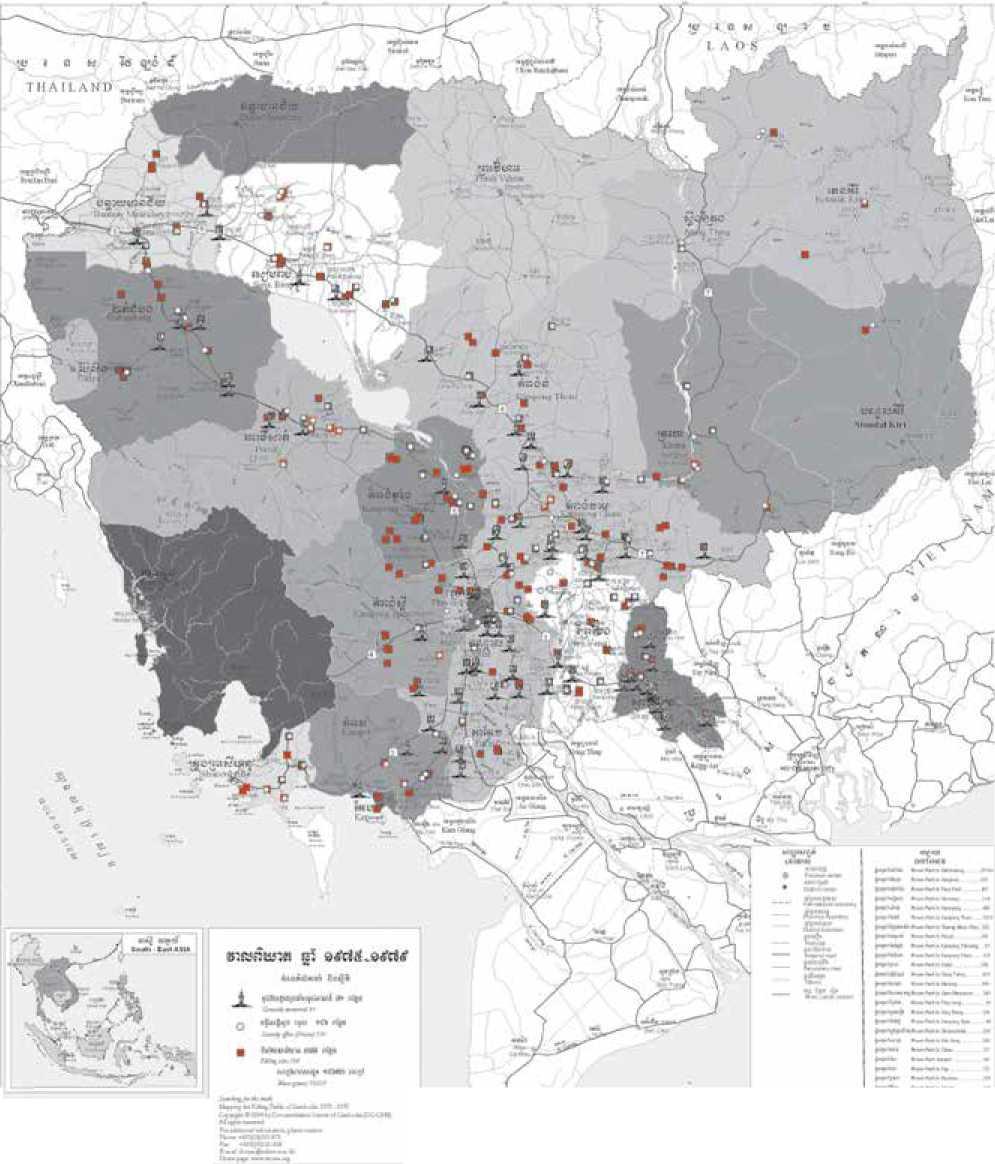

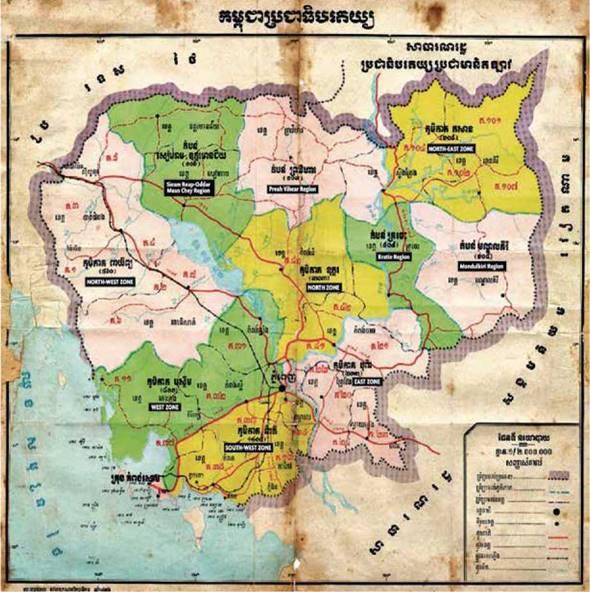

Chapter 6: Administrative Divisions of Democratic Kampuchea

In 1976, the CPK divided Democratic Kampuchea into six geographical zones. The zones incorporated two or more provinces or parts of old provinces. The CPK then divided the zones into 32 regions and gave all the zones and regions numbers. Below the regions were districts, sub-districts, and cooperatives.

East Zone (Zone 203). So Phim was the secretary of this zone; he committed suicide in May 1978. The East Zone consisted of Prey Veng and Svay Rieng provinces, part of Kampong Cham east of the Mekong River, one district from Kratie province (Chhlong) and some parts of Kandal province (Khsach Kandal, Lvea Em, and Muk Kampoul). The zone was divided into five regions: Regions 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24.

North Zone (Zone 303). Koy Thuon, alias Thuch, was the zone’s secretary from 1970 to early 1976. After he was arrested and executed at Tuol Sleng in 1976, Ke Pau became the secretary until 1977, when he was assigned to the newly established Central Zone. At that time, Kang Chap became the North Zone secretary. This zone consisted of Kampong Thom province, part of Kampong Cham (west of the Mekong River), and one district of

Kratie (Prek Prasap). Its regions were 41, 42, and 43.

Northwest Zone (Zone 560). Ros Nhim was this zone’s secretary. The zone comprised Pursat and Battambang provinces, and had seven regions: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

West Zone (Zone 401). Chuo Chet was its secretary. It consisted of Koh Kong and Kampong Chhnang provinces, and parts of Kampong Speu province. Its five regions were 31, 32, 37, 15, and 11.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Northeast Zone (Zone 108). This zone secretary, Ney Sarann, aka Ya, was purged in 1976. It comprised Rattanak Kiri and Mondul Kiri provinces, parts of Stung Treng west of the Mekong River, and part of Kratie province. Its six regions were 101, 102, 104, 105, 107, and 505.

In 1976, Democratic Kampuchea also created two autonomous regions, which reported directly to the Central Committee, not through a zone: Siem Reap-Oddar Meanchey Region (Region 106) and Preah Vihear Region (Region 103). Kampong Soam (now Preah Sihanoukville) was organized separately from the zones.

The Central Zone was established in 1977. It occupied the former North Zone, while the new North Zone was moved to the Siem Reap-Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear regions. Kratie Region (Region 505) and Mondul Kiri Region (Region 105)were taken from the Northeast Zone and made autonomous regions.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

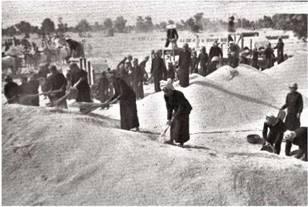

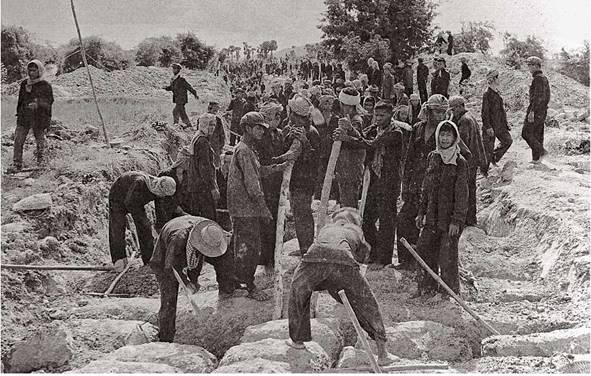

Chapter 7: The Four-Year Plan (1977-1980)

The Khmer Rouge emptied the cities in order to abolish urban living and to build a new Cambodia based on the expanded production of rice. In early 1976, the CPK hastily wrote the first four-year plan (1977-1980), which called for the collectivization of all private property and placed high national priority on the cultivation of rice. After national defense, collectivization was the most important policy of Democratic Kampuchea.

People in Cambodia had never been collectivized in the past. But in 1976, everyone was required to bring their private possessions (including kitchen utensils) to be used collectively. As part of the process, Cambodian families were split up and people were assigned to work groups. Husbands and wives were separated, and children were separated from their parents.

The four-year plan aimed at achieving an average national yield of three tons of rice per hectare. This was an impossible task because Cambodians had never been forced to produce that much rice on a national scale before. Moreover, the country had been devastated by war and lacked tools, farm animals and a healthy work force.

The four-year plan also included arrangements to plant vegetables, and hoped to generate income from timber, fishing, animal husbandry, tree farms, etc. The leaders of Democratic Kampuchea hoped to make Cambodia completely independent in both the economic and political spheres and turn Cambodia from an undeveloped agricultural country to a modern agricultural country.

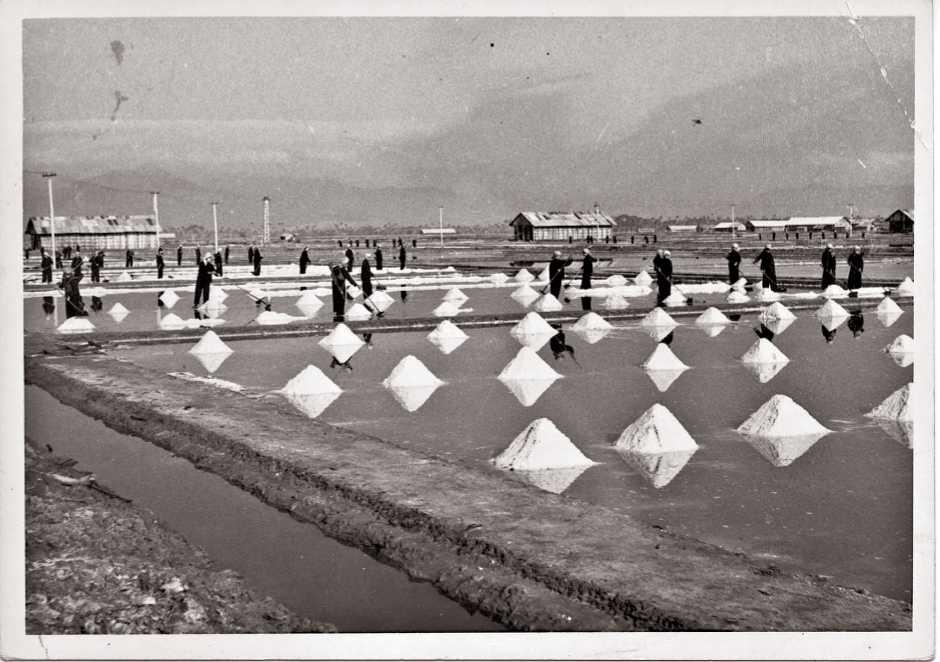

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

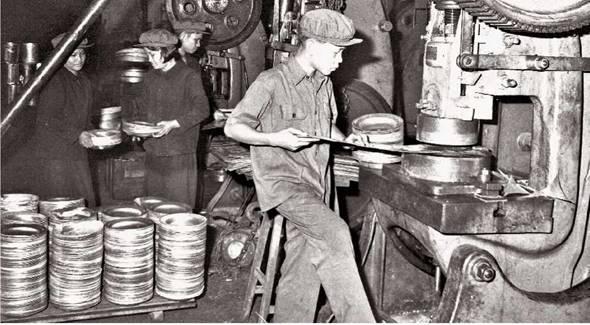

However, the leaders ignored the difficulties of implementing this plan and the miseries that flowed inevitably from overwork, poor living conditions, and malnutrition, lack of freedom and basic rights, and untreated diseases. Throughout the period of Democratic Kampuchea, the living conditions of people were very poor. In addition, the regime robbed nearly all Cambodians of their happiness and dignity. Most people know that a country needs educated people to develop. However, the Khmer Rouge killed many intellectuals and technicians, and closed all universities, schools and other educational institutes throughout the country. They then brought poor peasants from the countryside with no technical experience to work in Phnom Penh’s few factories.

The leaders of Democratic Kampuchea divided the country’s rice fields into number-one rice fields and simple rice fields. For the simple rice fields, the required yield was 3 tons per hectare, while farmers in the number-one rice fields were required to achieve 6 to 7 tons per hectare. In addition, the yields were to increase every year.

In theory, the crop was divided into four portions. Some of it was intended to feed people; everyone was entitled to receive 312 kilograms of rice a year or 0.85 kg a day. Some of the remaining crop was to be retained as seed rice and some was to be kept as a reserve. The last and biggest portion of the crop was to be sold abroad to earn foreign exchange, which could then be used purchase farm machinery, goods and ammunition.

Unfortunately, because production almost never reached the required levels, almost no rice was saved for the people or for seed. Instead, most of the harvest was used to feed the army and factory workers or was exported to China and several other socialist countries.

In Democratic Kampuchea, almost no one ever had enough to eat; in most cases, they only had rice porridge mixed with corn, slices of banana trees, or papaya tree trunks. Most people received less than half a milk can of rice a day. Only the Khmer Rouge cadres and soldiers received cooked rice. All survivors of the regime agree that what they remember the most, aside from hard labor and executions, was the extreme shortage of food.

father caught tadpoles for food. He thought that they were small fish. One day, a Khmer Rouge cadre killed a poisonous snake and placed it on the fence. Though he knew that it was poisonous, he still ate the snake, which killed him. My sister and her children died of starvation. My own family was in the same condition. We had done a lot of farming, but never had enough rice to eat. Being too hungry, I picked wild arum as food. After eating, all of us became very itchy. My children cried a lot. One day, I went to fish. The unit chief said, “You behave with very low character. Be careful!

Angkar will take you for execution.” Because of inadequate food, one of my children became seriously sick, so I exchanged my last necklace for rice and cooked it for her. She ate a lot but became sicker. She died as a result. The other two children and my husband also became sick because of malnutrition. However, we miserably managed to survive.

(Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

(Gunnar Bergstrom/Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

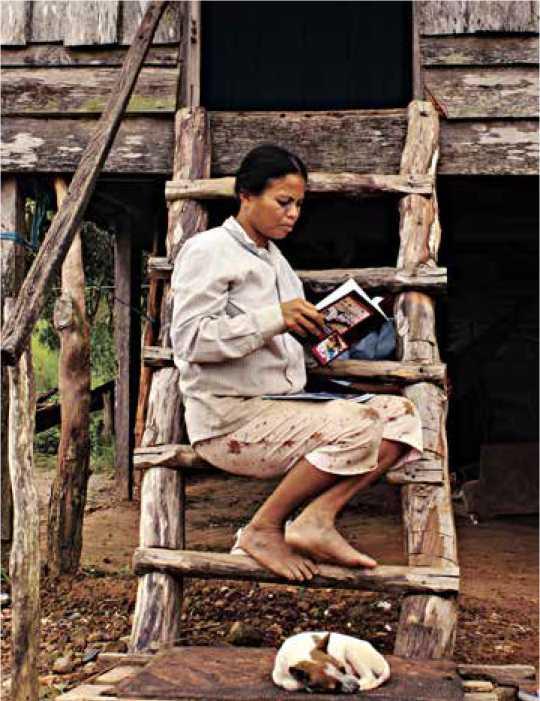

Chapter 8: Daily Life During Democratic Kampuchea

1. The Creation of Cooperatives

During the 1970-1975 civil war, most of the people living in the areas liberated by the Khmer Rouge were organized into “mutual aid teams” of 10 to 30 families. However, starting in 1973 and especially after the 1975 victory, mutual aid teams were organized into “low-level cooperatives,” which consisted of several hundred people or an entire village. By 1977, low-level cooperatives were reorganized into “high-level cooperatives,” which consisted of about 1,000 families each or an entire sub-district.

The CPK’s leaders established cooperatives as part of their move to abolish private ownership and capitalism, and to strengthen the status of workers and peasants. To the Khmer Rouge, a cooperative meant that people were supposed to live together, work together, eat together, and share each other’s leisure activities. This resulted in severe restrictions on family life. Cambodian families had eaten together for thousands of years, so eating in cooperatives, especially when food was scarce, was unpleasant and cruel. In addition, everyone in a cooperative had to give all of their property, which was their important means of production, to be used collectively. Such property included tools, cattle, plows, rakes, seed rice, and land.

The cooperatives were designed to be as self-sufficient as possible. The Khmer Rouge leaders described cooperatives as “great forces” for building up the country and as “strong walls” for protecting Democratic Kampuchea against its enemies.

2. Two New Classes

Although the Khmer Rouge claimed they were building a nation of equals and tearing down class barriers, they in fact created two new classes in Cambodia. They named these “the base people” and “the new people.”

The base people, or old people, were those who had lived in rural areas controlled by the CPK prior to April 17, 1975.