Don Cox & Steve Wasserman

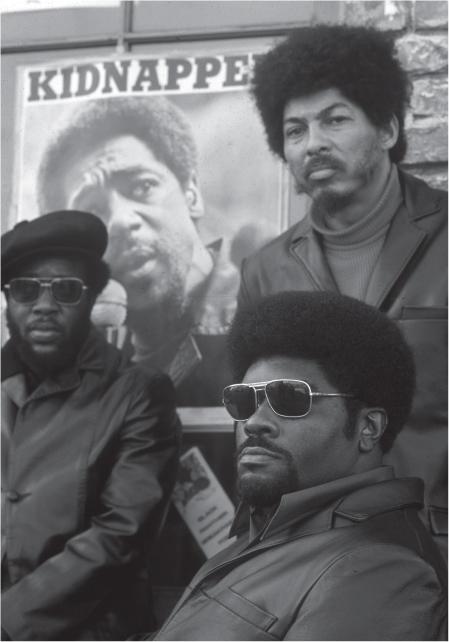

Just Another Nigger

My life in the Black Panther Party or use what you got to get what you need

Foreword by Kimberly Cox Marshall

Introduction by Steve Wasserman

5. Use What You Got to Get What You Need

Front Matter

Title Page

Publication Details

Organised in 2019 by Kimberly Cox Marshall

Introduction written in 2019 by Steve Wasserman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cox, Donald, 1936-2011, author.

Title: Just another nigger : my life in the Black Panther Party or use what you got to get what you need / Don Cox.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004946| ISBN 9781597144599 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781597144605 (e-pub)

Subjects: LCSH: Cox, Donald, 1936-2011. | Black Panther Party--History. | African Americans--Missouri--Biography.

Classification: LCC E185.615 .C692 2018 | DDC 322.4/20973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004946

Book and Cover Design by Ashley Ingram

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to: Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549–3564

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Epigraph

“In my own country for nearly a century

I have been nothing but a nigger.”—W. E. B. Du Bois

Foreword by Kimberly Cox Marshall

PROMISE MADE, PROMISE KEPT. I didn’t know that when he put his manuscript in my hands and made me promise to publish it after he passed, that would be the last time I saw him. But now it’s done: promise made, promise kept. And, yes, Daddy, I kept the title you wanted.

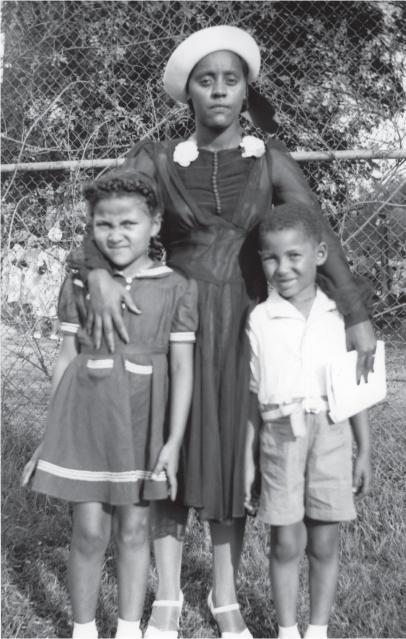

My first memories of Daddy are of the time we spent with his family. It seemed like almost every weekend we were either at his sister Irene’s or his aunt and uncle’s in Mountain View, about forty miles south of San Francisco, where we lived. His two sisters that lived out here in California, Irene and Mary Jane, doted on their younger brother, and that affection trickled down to me. How I loved my aunts! When I would visit, they would always have grapes with the skin peeled off, because “Donald’s daughter didn’t like the skin.” Every year until she couldn’t, my Aunt Irene sent me two dollars, and then five dollars (for inflation, as she said) for my Birthday Ice-Cream Cone. They were like that until they passed.

And then there was Daddy himself.

I have so many good memories of us together. I remember him picking me up from the San Francisco School of Ballet, and there he would be in his Austin-Healey, always with the top down. He would drive through Golden Gate Park so I could sit in the back and throw kisses like I was Miss America. When I would say I was going to hang out on the beach, like I saw girls doing in the movies, he never said anything to stop me. I realize now that I was never going to be in the San Francisco production of The Nutcracker, I wasn’t going to be Miss America, and most beaches had signs to keep me and my kind out, but Daddy never told me I couldn’t do any of those things. For him, I had no limitations.

I also loved our weekend outings to the movies as I got older and he started getting political. I didn’t recognize it then, but I do now: all of the movies were war movies. And as it turned out, watching all those tactical storylines paid off for me, and for him. I remember one time, during the years Daddy was in the Black Panther Party and I was going to private school in the Richmond District of San Francisco, there was a man known for accosting and molesting young girls in the area. That same man had followed me to school one day, and as soon as I was inside the building I called my family to tell them about it. A week later, as I was getting off the bus, there was Daddy waiting at my stop, dressed in his old Brooks Brothers suit and with his afro cut off. He gave me a look that said I should be quiet and opened his jacket to show me he was carrying. I got off the bus and went on ahead to walk the five blocks to school, and although Daddy was nowhere to be seen, I knew he was watching my every move.

Another time, when I was going to a Lutheran school, I wore my hair in a curly afro one day. How proud I was—until I got to school. The principal told me my hair looked a mess. I promptly called Daddy, and I don’t remember what I told him, but the next thing I knew, here comes Daddy and about four or five Panthers looking fine and sharp in all-black turtlenecks, pants, leather coats, and berets. I never heard my Daddy raise his voice—I think I would have crapped in my pants if I did—and when he spoke, he always spoke eloquently and softly and looked you directly in the eyes. For people who didn’t know him, that alone could make them crap in their pants. I didn’t hear what he said to the principal that day, but at the end of the year I left that school for good.

When I was ten or twelve years old, we lived down the hill from Alamo Square, and whenever I heard the helicopters, I would ride my bike looking for friends to come with me to the Panther office. We would ride to the top of the square to see if there were more than two “eyes in the sky” (helicopters), and if so we would ride our bikes to the Panther office—us dumb kids figuring the cops wouldn’t shoot if there were kids around.

Here are some things I learned from Daddy:

My family taught me empathy, and Daddy was never one to shy away from showing it.

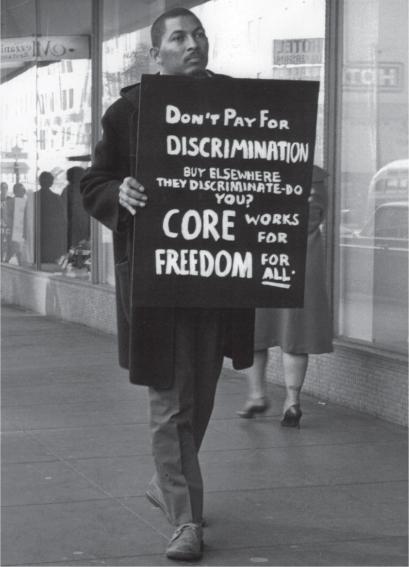

I loved marching with him in the CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) protest marches of the early sixties, and even though I was probably too young for it, I was exposed to many important things there.

During events put on for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, in 2016, I had men search me out to tell me that if it wasn’t for Daddy they don’t know where they would have ended up in life—that he taught them so much.

He and my mother also taught me we have to invest in our young people, as they are our future.

Among all the things I’m grateful for, one thing that stands out is this: I got to meet Stokely Carmichael (later, Kwame Ture) and his wife, Miriam Makeba, when they came to dinner at my grandparents’ house. I didn’t realize it at the time (but I so cherish the memory now) that I was being taught about apartheid literally at the knee of “Mama Africa.” I remember she told me a story of how her brother wasn’t legally allowed to ride his bike at night in their native South Africa because they had to come indoors when it got dark. I was about twelve at the time and could hardly believe my ears, such a story was so foreign to my experience. I always remember that conversation because everyone around me got so quiet. I can imagine where those memories took my grandparents and great-grandmother, who were from the South.

No matter how proud I was of Daddy’s activities, though, there was also a flipside. Schoolmates stopped playing with me and inviting me to their parties because of Daddy’s politics. A relative that had the same last name changed it for a time so they would not be associated with our family. Our phone was tapped. The eye in the sky would flash its spotlight into my bedroom window, and sometimes we would come home and find the FBI surrounding the house or Daddy’s car—the GTO he drove to Nevada to buy guns. My mother would literally shoo the police away like flies. I heard once Daddy had even used a dead baby’s death certificate to get a fake passport. When things started to go bad in the party, there were two kidnapping attempts on me, and one night a woman came to our house to kill my mother, brother, and me. We can only thank goodness that she was so high she couldn’t go through with it. My mother talked her down and she left. By then things were so bad that Daddy left the United States and started his life in exile. I would not see him for thirteen years, and I communicated with him only about five times before I saw him again in 1984.

By then I had become a woman, gotten married, had a child, and divorced. When I saw him again in Paris, I wasn’t that wide-eyed girl anymore. I had taken off the rose-colored glasses and realized that Daddy was just a man, faults and all. I was taken aback to learn that even though he had married a wonderful woman after divorcing my mother, he still saw the need to have a mistress, whom he wanted me to meet. I assumed this was the French way at the time, but I was American, and anyway, if it wasn’t wrong, why did he ask me to keep it quiet? I mention this now because it was one of the things he despised about his own father—that his father would give money to his mistress to give to the church but wouldn’t give money to his own mother. It was also eye-opening to read his manuscript and see how he treated women when he himself had a daughter who he was raising to have the views I have. These are things I wish we could have talked about.

As you read this book, you will realize that this man was like two sides of a coin. At the forty-fifth anniversary of the Black Panther Party, a close comrade confessed that he didn’t know my father even had kids (myself and two brothers) until he read his obituary. It seems he had some success keeping his family away from the party, but, although he tried, he couldn’t completely keep the party away from his family. As I grew up the daughter of Donald Cox, the Panthers and their dramas were never far away.

Introduction by Steve Wasserman

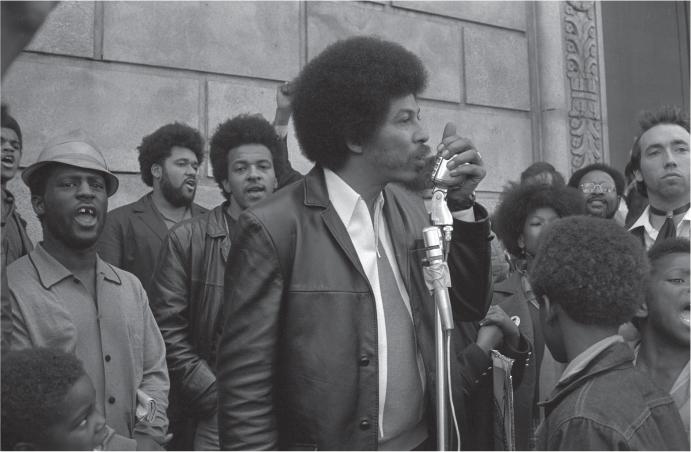

MORE THAN FIFTY YEARS AGO, in October 1966, back in what seems at this remove the Pleistocene era, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, brash upstarts from Oakland, California, founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. They quickly garnered a reputation for their willingness to stand up to police harassment and worse. They made a practice of shadowing the cops, California Penal Code in one hand, twelve-gauge shotgun in the other. Soon they were holding street-corner rallies and confronting officials, arguing that only by taking up arms could the black community put a stop to police brutality. Newton and Seale were fearless and cocky—even reckless, some felt—and itching for a fight.

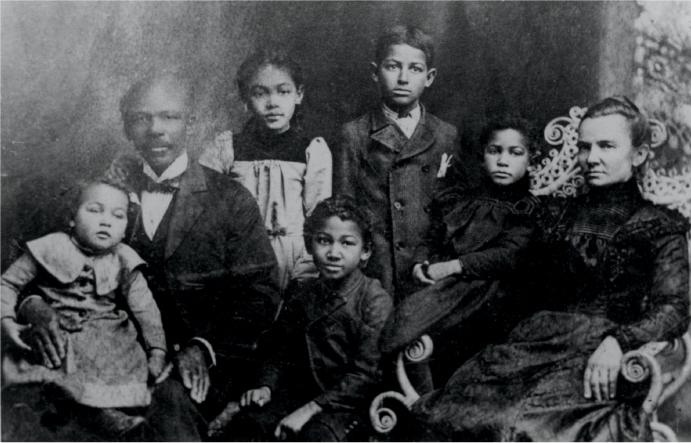

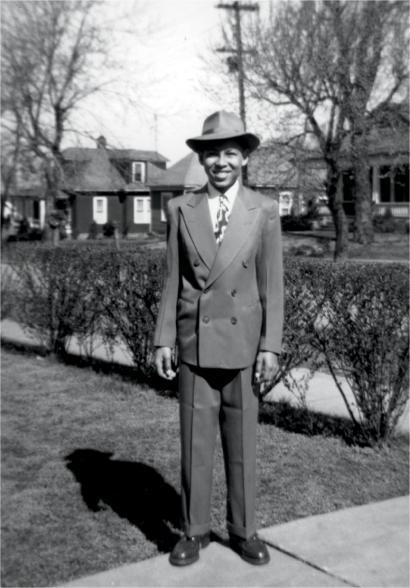

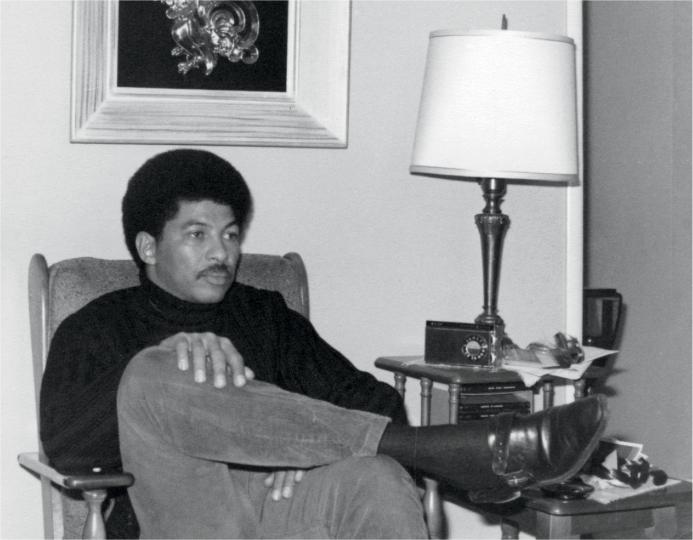

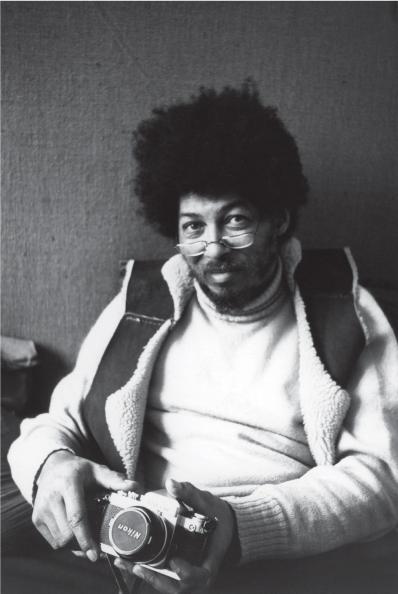

Don Cox, thirty-two years old, married with two young children, and working in San Francisco as a commercial photographer, had participated in numerous Bay Area civil rights protests, but, over time, his discontent with the slow pace of change had deepened while his desire for more militant action mounted. He greatly admired how Newton “practiced what he preached,” how “with gun in hand he faced down armed, racist policemen,” how the Panthers were “ready to kill.” Born in Missouri, Cox was proud of his rebel lineage. According to family lore, his grandfather, Joseph A. Cox, rode with Jesse James and was well known for his independent streak, which included marrying a young Swiss immigrant, Maria Müller, at a time when interracial marriage risked not just racist condemnation and social ostracism but even lynching. The family was no stranger to guns, and young Don Cox gained a deserved reputation as something of a sharpshooter.

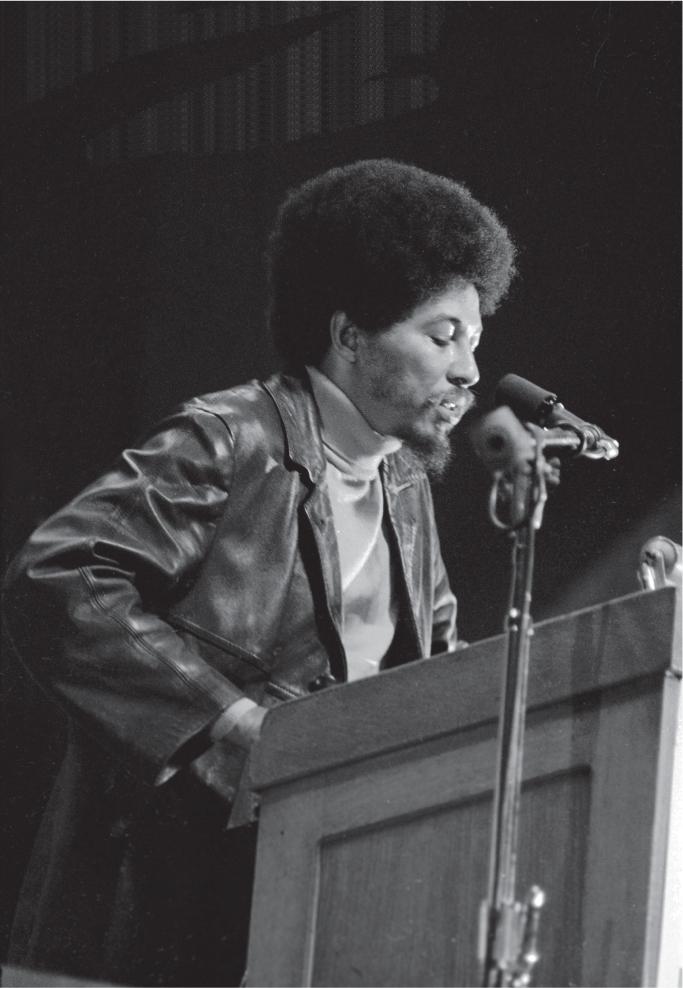

Alarmed by the Panthers’ growing prominence, in 1967 California legislator Donald Mulford introduced a bill to ban the carrying of loaded weapons in public. Newton responded by upping the ante, and in early May of that year he dispatched thirty Panthers, most of them armed, to Sacramento. They showed up at the state capitol building as the bill was being debated. The police confiscated their guns soon after they arrived, but later returned them, as the Panthers had broken no laws. The Mulford Act passed, but the Panthers became instantly notorious, with images of their armed foray splashed across the nation’s newspapers and shown on television. It was a PR coup. Soon thousands of black Americans joined the party, among them Don Cox. By the end of 1968, seventeen Panther chapters had opened across the country. One enthusiast quoted in a major feature story in the New York Times Magazine spoke for many, including Cox, when he said: “As far as I’m concerned it’s beautiful that we finally got an organization that don’t walk around singing. I’m not for all this talking stuff. When things start happening I’ll be ready to die if that’s necessary and it’s important that we have somebody around to organize us.”

THE RISE AND FALL of the Black Panther Party is a heartbreaking saga of heroism and hubris that, in its full dimension and contradiction, has long awaited its ideal chronicler. The material is rich, some of it still radioactive. A good deal of it can be found in the clutch of memoirs by ex-Panthers—inevitably self-serving but valuable nonetheless—that have appeared sporadically over the years, including those by Bobby Seale, David Hilliard, and Elaine Brown, and lesser-known figures such as William Lee Brent, Flores Forbes, and Jamal Joseph, and in books and articles by non-Panthers, especially those by David Horowitz, Kate Coleman, Hugh Pearson, and by sociologist Joshua Bloom and historian Waldo E. Martin, Jr., whose Black Against Empire is a flawed but indispensable history of the party. All are to be read with care.

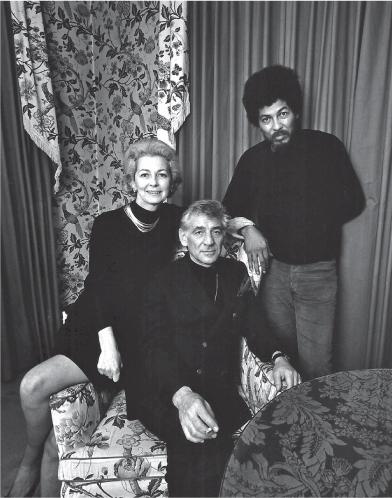

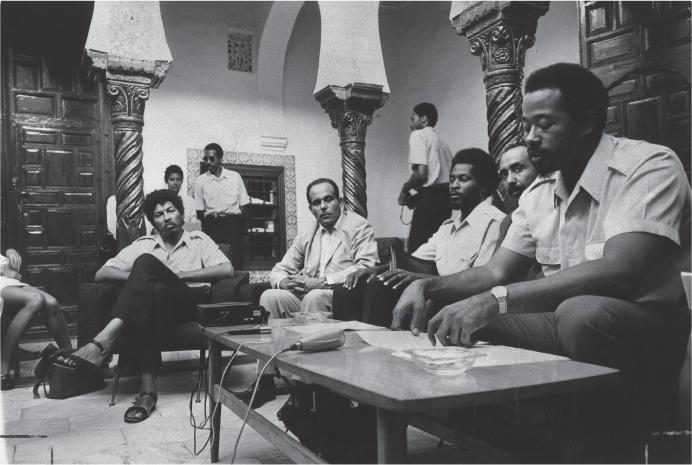

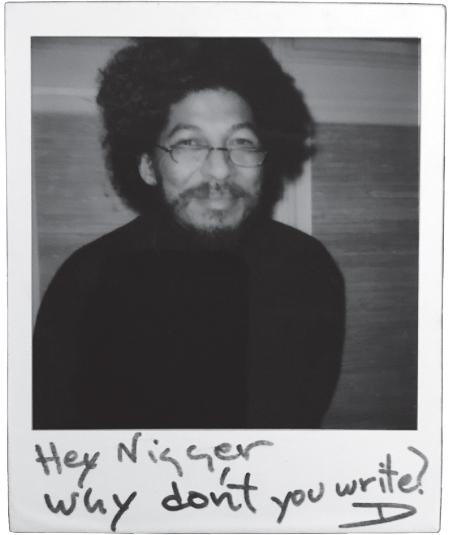

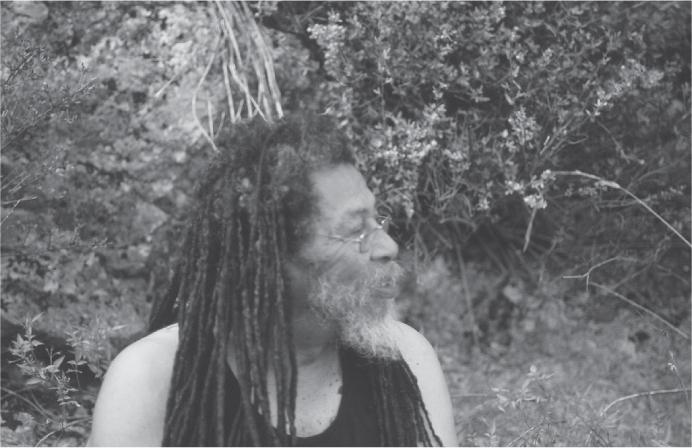

To this literature we may now add Don Cox’s revelatory, even incendiary story of his five years in the Black Panther Party, from his work as Field Marshal in charge of weapons procurement, gunrunning, and planning armed attacks and defense—including tales told for the first time in this memoir—to his star turn as a party spokesman raising money at the Manhattan home of Leonard Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, for which he was famously mocked by writer Tom Wolfe, to his eventual flight to Algeria to join Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, to his decision to leave the party in 1972, following his disillusionment with Newton’s leadership. Cox would live out the rest of his life in self-imposed exile in France, in the mountain village of Camps-sur-l’Agly, where he wrote these unrepentant recollections in the early eighties, enjoining his daughter, Kimberly, to promise him she would do everything she could to have them published after his death. Cox died in 2011 at age seventy-four.

The Panthers were controversial in their day and remain so. Peopled by outsize characters—starting with magnetic and headstrong founder Huey P. Newton, eulogized at his 1989 funeral as “our Moses”—the party’s complicated history, replete with Byzantine political schisms, murderous infighting, and a contested legacy, has eluded sober examination. Its story is swaddled in propaganda, some of it promulgated by enemies who sought assiduously to destroy it, and some spread by apologists and hagiographers who lionized the party’s admirable efforts to bring education, food, clothing, and medical treatment into America’s impoverished ghettos while refusing to acknowledge the party’s crimes and misdemeanors, preferring to attribute its demise almost entirely to the machinations of others. Cox is not among them. His memoir is notable for his unsentimental and, by turns, self-critical approach.

One of the things that attracted Cox and others to the Black Panther Party was its refusal to go along with the narrow cultural nationalism that appealed to many African Americans at that time. The party’s dispute with Ron Karenga’s US Organization, for example, was rooted in this profound disagreement. The Panthers fought tremendous battles, some turning deadly, with those who thought, as the saying went, that political power grew out of the sleeve of a dashiki. By contrast, the Panthers embraced a class-based politics with an internationalist bent. Inspired by anti-imperialist struggles in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, they began by emphasizing local issues but soon went global, ultimately establishing, as Cox vividly recounts, an International Section in Algiers. Their romance with the liberation movements of others would eventually become something of a fetish, reaching its nadir in the bizarre adulation of North Korea’s dictator Kim Il-sung and his watchword Juche, a term for the self-reliance that the Panthers deluded themselves into thinking might be the cornerstone of a revolutionary approach that would find an echo of enthusiasm in America.

In the beginning, little about the party was original. Even the iconic dress of black leather jackets and matching berets was inspired by earlier Oakland activists, such as the now-all-but-forgotten Mark Comfort. As early as February 1965, the month Malcolm X was assassinated, Comfort had launched a protest to “put a stop to police beating innocent people.” Later that summer, Comfort and his supporters demanded that the Oakland City Council “keep white policemen out of black neighborhoods” and together took steps to organize citizen patrols to “monitor the actions of the police and document incidents of brutality.”

This wasn’t enough for Newton and Seale. Inspired by Robert F. Williams’s advocacy and practice of “armed self-reliance”—for which he’d had to flee the country in the early 1960s, seeking sanctuary in Castro’s Cuba—Newton and Seale decided to break entirely with “armchair intellectualizing,” as Seale would later call it. Propaganda of the deed, they believed, would arouse the admiration of, in Newton’s words, the “brothers on the block.” They’d had it with bended-knee politics. It was time, as a favored slogan of the party would later urge, to “pick up the gun.” Drawing up a ten-point program with demands for justice and self-determination, the Panthers represented a rupture with the reformist activism of the traditional civil rights movement, and it wasn’t long before the party saw itself as a vanguard capable of jump-starting a revolution. For some, including Don Cox, it was an intoxicating fever dream. I, too, was not exempt, and I hope I shall not exceed the bounds of readers’ indulgence if I share my own stake in the story that Cox so ably tells.

IN EARLY NOVEMBER 1969, I left Berkeley for a few days and went to Chicago to support the Chicago Eight, then on trial for the bloody police riot that had marred the anti–Vietnam War protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. I knew some of the defendants: Jerry Rubin, organizer of one of the first teach-ins against the Vietnam War, whom I’d met four years before while organizing the first junior high school protest against the Vietnam War; Tom Hayden, a founder of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and principal author of The Port Huron Statement, who’d taken an interest in my rabble-rousing posse at Berkeley High School during the People’s Park protest of May 1969; and Bobby Seale, whom I’d encountered through my close friendship with schoolmates who’d joined the Panthers, especially Ronald Stevenson, with whom I coled a successful student strike in 1968 that established the first black studies and history department in an American public high school. It was Bobby who’d let a group of us use the party’s typesetting machines in its Shattuck Avenue national headquarters to put together an underground newspaper, Pack Rat.

In the Chicago Eight trial, Seale had been bound and gagged in the courtroom—a “neon oven,” activist and defendant Abbie Hoffman had called it—and the country was riveted by the appalling spectacle. I arrived at the apartment rented by Leonard Weinglass, one of the defense attorneys, who was using it as a crash pad and general meeting place for the far-flung tribe of supporters and radical nomads, unafraid to let their freak flags fly, who sought to muster support for the beleaguered defendants.

Sometime around midnight, Fred Hampton, leader of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party, clad in a long black leather coat and looking for all the world like a gunslinger bursting into a saloon, swept in with a couple of other Panthers in tow. You could feel the barometric pressure in the room rise with their entrance. At the time, the favored flick was Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, an epic Western revenge fantasy that inflamed the overheated imaginations of a number of unindicted coconspirators like my friend Stew Albert, a founder of the Yippies. Hampton was already in the crosshairs of the FBI and Chicago mayor Richard Daley’s goons, to whom he’d been a taunting nemesis. He had an open face, and his eyes flashed intelligently. He had the Panther swagger down pat, yet his voice was soft, welcoming. He radiated charisma and humility. He seemed tired, and somehow you knew he was already thinking of himself as a dead man walking. He was famous for having proclaimed, “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution.” You could see how people fell for him, and you could well imagine how his enemies hated and feared him. A month later he was murdered, betrayed by a paid undercover informant and shot dead by police while sleeping in his bed. He was twenty-one.

Hampton seemed destined for greatness, having already eclipsed in his seriousness Eldridge Cleaver, the party’s minister of information and an ex-con who’d written the bestselling Soul on Ice. Cleaver was regarded by many of the younger recruits within the party as their Malcolm X. A strong advocate of working with progressive whites, Cleaver was a man of large appetites, an anarchic and ribald spirit who relished his outlaw status. After years in prison, he was hell-bent on making up for lost time and wasn’t about to kowtow to anyone—not to Ronald Reagan, whom he mocked mercilessly, nor, as it would turn out, to Huey Newton. Like so many of the Panthers, he also had killer looks, inhabiting his own skin with enviable ease. (The erotic aura that the Panthers presented was a not inconsiderable part of their appeal, as any of the many photographs that were taken of them show. In this department, however, Huey was inarguably the Supreme Leader, and he never let you forget it.) Eldridge was the biggest mouth in a party of big mouths, and he especially loved invective and adored the sound of his own voice, delivered in a sly baritone drawl. He was the joker in the Panther deck and a hard act to follow. He was a gifted practitioner of the rhetoric of denunciation, favoring such gems as “fascist mafioso” and given to vilifying the United States at every turn as “Babylon.” He was a master of misogynist pith, uttering the imperishable “revolutionary power grows out of the lips of a pussy,” and he was fond of repeating, as if it were a personal mantra, “He could look his mama in the eye and lie.” He was notorious in elite Bay Area movement circles for his many and persistent infidelities and for his physical abuse of his equally tough-talking and beautiful wife, Kathleen. About these failures, however, a curtain of silence was drawn. He was, all in all, a hustler who exuded charm and menace in equal measure, as Cox’s memoir confirms. Cleaver would ultimately flee the country, rightly fearing a return to prison for parole violation following his bungled shootout with Oakland police in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968. (Don Cox, who was ostensibly in charge of the party’s clandestine military operations, apparently had little to do with Cleaver’s abrupt and ill-conceived decision to ambush the officers.) The debacle had given the Panthers their first martyr, seventeen-year-old Bobby Hutton, the nascent party’s first recruit, gunned down by the cops as he sought to surrender. His funeral was front-page news; Marlon Brando was a featured speaker. Cleaver was arrested, released on bail, and then disappeared, heading first to Cuba and then to Algeria, where Cox and other Panthers and sympathizers would later join him.

When Cleaver fled, Newton was still in prison, awaiting trial for killing an Oakland cop. Now Bobby Seale was fighting to avoid a similar fate in Chicago. David Hilliard, the party’s chief of staff, was left to try to hold the group together. Hoover’s FBI, sensing victory, ratcheted up its secret COINTELPRO campaign, in concert with local police departments across the country, to sow dissension in the party’s ranks and to otherwise discredit and destroy its leaders. Hoover was a determined foe; he too had seemingly embraced Malcolm X’s defiant slogan “By any means necessary.” He cared a lot about order and about the law not a whit. With King gone, he worried, not unreasonably, that the Panthers would widen their appeal and step into the breach.

The suppression of the urban rebellions that erupted in many of the nation’s cities in the hinge year of 1968 underscored the Panthers’ fear that the United States had entered a long night of fascism. Nonviolent protest struck a growing number of activists as having run its course in the face of unsentimental and overwhelming state power. The Vietnam War, despite the upwelling of the Tet Offensive, seemed endless. Richard Nixon’s election on a platform of “law and order” made a generation of reform-minded progressives seem hopelessly naïve. Fires were being lit by a burgeoning and increasingly despairing discontent. For some time, Jim Morrison had been singing of “The End.” Soon, Gil Scott-Heron would intone that “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” and from his California prison cell, Huey P. Newton began to dream of “revolutionary suicide.”

THE PARTY BEGAN TO CRACK under persistent government pressure, and internecine quarrels became ferocious and sometimes deadly. There were fierce clashes, large and small, over personalities and politics. Only later would the details emerge. For example, former Panther leader Elaine Brown gave a hair-raising account in her autobiography A Taste of Power (1992) of how Newton viciously turned on Seale, his comrade and peerless organizer (some details of which are disputed by Seale). She recalled how Newton succumbed to his cocaine-and-cognac-fueled megalomania; how he ordered Big Bob Heard, his six-foot-eight, four-hundred-pound bodyguard, to beat Seale with a bullwhip, cracking twenty lashes across Bobby’s bared back; how, when the ordeal was over, Newton abruptly stripped Seale of his rank as party chairman and ordered him to pack up and get out of Oakland. David Hilliard, too, Newton’s friend since they were thirteen, would be expelled, as would his brother, June. Also ousted was Seale’s brother, John, deemed by Newton to be “untrustworthy as a blood relative of a counterrevolutionary.” Newton became what he arguably had been from the start: a sawdust Stalin. About this transformation Cox is remarkably forthcoming.

Still later, Flores Forbes, a trusted enforcer for Newton, came clean. He was a stalwart of the party’s Orwellian “Board of Methods and Corrections,” and a member of what Newton called his “Buddha Samurai,” a praetorian guard made up of men willing to follow orders unquestioningly and do the “stern stuff.” Forbes had joined the party at fifteen and wasted no time becoming a zombie for Huey. Forbes was bright and didn’t have to be told; he knew when to keep his mouth shut. He well understood the “right to initiative,” a term Forbes tells us “was derived from our reading and interpretation of Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon.” What Forbes took Fanon to mean was that “it is the oppressed people’s right to believe that they should kill their oppressor in order to obtain their freedom. We just modified it somewhat to mean anyone who’s in our way,” like inconvenient witnesses who might testify against Newton, or Panthers who’d run afoul of Newton and needed to be “mud-holed”—battered and beaten to a bloody pulp. Newton no longer favored Mao’s Little Red Book, preferring Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, which he extolled for its protagonists’ Machiavellian cunning and ruthlessness. Newton admired Melvin van Peebles’s movie Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the tale of a hustler who becomes a revolutionary. Military regalia was out, swagger sticks were in. Newton dropped the rank of minister of defense in favor of other titles. Some days he wanted to be called Supreme Commander, other days Servant of the People or, usually, just Servant. But to fully understand Huey’s devolution, you’d have to run Peebles’s picture backward, as the story of a revolutionary who becomes a hustler. To these horrors, Cox adds his own story of self-inflicted wounds revolving around the cult of personality and the murderous megalomania of his erstwhile comrades, including Eldridge Cleaver.

SOME YEARS AGO, I spent an afternoon with Bobby Seale, renewing a conversation we’d begun months before. He’d moved back to Oakland, living once again in his mother’s house, and was contemplating writing a book—the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, as he put it to me, about the rise and fall of the Panthers—on the very dining room table where almost a half century ago he and Newton had drafted the Panthers’ Ten-Point Program. No one was getting any younger, and he felt he owed it to a new generation to speak frankly. At his invitation, we jumped into his car and, with Bobby at the wheel, drove around Oakland, visiting all the neighborhood spots where history had been made. Here was the corner where Newton had shot and killed Officer John Frey in October 1967; and there was the former lounge and bar, the notorious Lamp Post, where Newton had laundered money from drug deals and shakedowns; and over there were the steps of the Alameda County Courthouse, where thousands, including myself, had assembled in August 1970 to hail Newton’s release from prison and where, beneath the blazing summer sun, Huey, basking in the embrace of the adoring crowd, had stripped off his shirt, revealing his cut and muscle-bound torso, honed by a punishing regimen of countless push-ups in the isolation cell of the prison where he’d done his time, a once slight Oakland kid now physically transformed into the very embodiment of the powerful animal he’d made the emblem of his ambitions.

As Seale spoke, mimicking with uncanny accuracy Huey’s oddly high-pitched and breathless stutter, virtually channeling the man, now dead more than two decades—ignominiously gunned down at age forty-seven in a crack cocaine deal gone bad by a young punk half his age seeking to make his bones—it became clear that, despite everything he’d endured, Bobby Seale was a man with all the passions and unresolved resentments of a lover betrayed. There could be little doubt that, for Seale, the best years of his life were the years he’d spent devoted to Newton, who, despite the passage of time, still loomed large. Seale, like the party he gave birth to, couldn’t rid himself of Huey’s shadow.

AMONG THE CHALLENGES in grappling with the Panthers and their legacy is keeping in reasonable and proportionate balance the multiple and often overlapping factors that combined to throttle the party. The temptation to overemphasize the role of the FBI is large. It should be avoided. There is no doubt about the evil that was done by Hoover’s COINTELPRO: It exacerbated the worst tendencies among the Panthers and did much to deepen a politics of paranoia that would ultimately help hollow out what had been a steadily growing movement of opposition. It sowed the seeds of disunity. It cast doubt on the very idea of leadership. It promoted suspicion and distrust. It countenanced murder and betrayal. But the Panthers themselves were not blameless. Newton, for his part, provided fertile ground for reckless extremism and outright criminality to grow and take root. Cockamamie offshoots like Donald DeFreeze’s so-called Symbionese Liberation Army and even the lethal cult of Jim Jones’s benighted Peoples Temple owed an unacknowledged debt to Newton’s example. His responsibility for enfeebling his own and his party’s best ambitions, gutting its achievements and compromising its ability to appeal to the unconvinced majority of his fellow citizens, is too often neglected in any number of books purporting to tell the party’s story. Don Cox’s memoir is an exception. It is precisely the sort of postmortem that is necessary for any proper and just understanding of the party’s politics and history. It is a brave and honest book and a welcome contribution to a historical reckoning that is long overdue.

1. Joe Cox’s Grandson

IT WAS A COOL DAWN April 14, 1936, when I tore my way into this world—feet first and weighing twelve pounds—my delivery further complicated by some difficulty in getting me to breathe. The umbilical cord, wrapped around my neck, was strangling me. Mine was a troubled introduction into life.

We lived on a small subsistence farm close to a village called Appleton City, Missouri, about eighty miles southeast of Kansas City. It supplied us with our vegetables, poultry, eggs, smoked pork, milk, and butter. Occasionally Mama sold some eggs or an extra pound or two of butter, but it wasn’t anything systematic. In winter about one meal a week came from hunting.

I was preceded by one brother, Junior, and three sisters, Irene, Mary Jane, and Marleeta. Papa worked in town at the Ford garage as a mechanic. He had taken a correspondence course to learn the trade, and proudly displayed his huge framed diploma on the living room wall. He worked the land, slopped the hogs, and fed the cow in the morning and evening, before and after work and on weekends. Mama held down the house, the poultry, and the vegetable plot, plus cooked three meals a day and did the Monday washing. And every minute in between was spent sewing something—creating an article of clothing for someone in the family or making patchwork quilts, masterpieces worthy of any museum.

My memories begin during the Second World War, after Pearl Harbor. Junior was away in Parsons, Kansas, doing public-works jobs at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, and when he came home on leave in his sharp uniform, I assumed he was a special kind of a soldier. Irene was about two hours away in Sedalia, attending high school. I thought she was the most beautiful woman in the world; she was my standard of beauty. Mary Jane, the oldest at home, worked right alongside Mama, and Marleeta and I just played every day. Her year-and-a-half seniority over me gave her the edge in decision-making, so whatever she decided to do, I did. When she played with dolls, I played with dolls. When she sewed dolls’ clothes, I sewed dolls’ clothes. When she learned to embroider, I learned to embroider. When she decided to dress up in Mama’s old clothes, I dressed up in Mama’s clothes.

I remember when I got my doll. The store had many sizes and shapes, and I chose the colored one. It was rather small and had three tufts of black hair sticking out, one on top and one on each side. I named her Kinky Lee-Andre. I’ll never know how I came up with a name like Lee-Andre in the cornfields of Missouri.

When I was around five years old, my mother told me that from then on it was my job to dry dishes. I was upset. I protested and cried but, in the end, I dried dishes. In those days you could yowl and protest all you wanted as long as you did what you were told. If you rebelled you were sent out to fetch a switch, which Mama would use to whip your behind. She could make a switch sing. If you brought in one too light and flimsy, she would go back out and get one that always seemed to me more like a branch. And these weren’t just symbolic beatings, either. When she was through, you had welts on your behind. In those days I cried and protested a lot.

Then came the ultimate humiliation. It was now my job to empty the chamber pot. For those of you who know only urban or modern environments, the chamber pot was a kind of enamel bucket with a lid that everyone used to piss and shit in at night or during real bad weather, instead of making the trip out back to the outhouse. It’s surprising how many times it was full to the brim, and at that age I didn’t have the physical strength to carry it in a way that would avoid the inevitable spills. I was condemned for life. Being the youngest, there was no one coming up behind me to pass the buck to as I grew older. Until I went to California, when I was seventeen, we never had an indoor bathroom.

Mama was a saint. She taught me that there were no bad people in the world, only those who made mistakes or stumbled along the path of righteousness. That naïve simplicity touched me to the marrow. Even today’s state of the world hasn’t dampened my hope in the future of our species. Mama and Papa believed that all one had to do was work hard and go to church and everything would be all right. And, of course, it didn’t hurt to have a good dose of the patriotism that any other peasant from Missouri had during that time of world war. What mattered was to carry yourself in a manner that would earn the respect and approval of everyone.

That’s probably why I never liked watermelon. At that time, stereotyped images of colored people always showed them with a big slice of watermelon, and I didn’t want anyone to see me like that. I remember one winter, after we had moved to Sedalia to be close to a school, I went down to J. C. Penney with Mama to buy a pair of mittens. Naturally, I grabbed the red pair, my favorite color, but Mama insisted on a gray pair. I protested. Without a word or so much as a glance at me, she gave me one of the most vicious backhands in the mouth I’d ever got. It was many years later before I understood why she did that. At the time, I didn’t know that red was supposed to be all niggers’ favorite color.

The only music allowed at home was religious or classical. Jazz and blues was the music of the devil. Papa was an excellent tenor. Too bad he was confined to backwoods obscurity. He sang in the church choir and in a quartet of friends, and later became the director of the church choir. He would work all year long preparing for the annual Christmas and Easter cantatas. He would send off for the sheet music and then make copies by hand to distribute to members of the choir. We had an upright piano at home, and all my sisters at one time or another took piano lessons. It never appealed to me, so I was never pushed to do the same.

Papa was stern. My relationship with him consisted of hello; goodbye; yes, sir; and no, sir. Period. He was sort of a mysterious ogre that was often invoked by Mama and my sisters if I didn’t behave. In other words, whatever I was doing wrong, they said they were going to tell Papa about it when he came home. That made me take on a defensive attitude toward him, and whenever he was at home I would keep as much distance between him and me as possible. Because I was always trying to do what I wanted, rather than what Mama or my sisters wanted, I was never really certain when they were going to carry out the threat to inform on me, so as far as I was concerned, Papa was someone to avoid.

The only time my fears were realized, he was home sick with something and Marleeta and I were messing around, like kids do. On all the windows and doors of the house there were fine mesh screens to keep out the flies, and Marleeta and I liked to press our lips against them as hard as we could so that when we withdrew, our lips would bear the pattern imprint of the screen. That day, Marleeta was pressing her lips into a full spread and I was standing on the other side. Looking at her like that, I just couldn’t resist picking up a wooden yardstick and holding one end while pulling back on the other, aimed at her lips. She never thought I would be so callous as to let it go, but, naturally, I did.

The instant the yardstick hit her mouth I knew I had made the mistake of my life. She let out the most blood-curdling scream. Papa bounded out of bed. I froze. I knew what lay in store for me. Papa seized the yardstick and I started screaming, fearing he was going to skin me alive. He had finished whipping me and was back in bed before I realized that he hadn’t hurt me at all. It was the only whipping he ever gave me. But my fear of him had kept me screaming anyway.

All social and cultural activity back then was centered on church. Sunday school and church services took up half a day on Sunday, and then there were Wednesday night prayer meetings, Friday night choir practices, and one night for the usher board. The colored church in Appleton City was one of the sources of pride for our family because it was Grandpa Joseph Cox, Papa’s father, who had started it. Papa had two black metal boxes that seemed to contain all the family treasures, and among them was Grandpa Cox’s preacher’s license and the correspondence from the district superintendent of the Methodist church asking Grandpa to send fifty cents for a license so he could start a church.

Grandpa Cox was a special case. He was born in 1845. Someone on the plantation where he was born kept a record of when the slave women gave birth, and the page recording Grandpa’s birth was also in one of the black boxes. The wife of the plantation owner taught Grandpa how to read and write—a move that was progressive at the time, and an offense punishable by law. Upon his “liberation,” the simple fact of his literacy gave him a relative power and self-respect that labeled him an “uppity nigger.” It was always a source of great pride in the family that a hole in the wall of a store in Osceola, Missouri—put there by a shotgun blast—bore testimony to Grandpa’s objection to that appellation. He was a righteous uppity nigger, all right. As ultimate proof, he married a white woman. To do so, they had to go to the state of Kansas because interracial marriage in Missouri was illegal. Maria Müller had been brought to the States by her mother from the German-speaking part of Switzerland after her father, Jacob Müller, had died.

Unless they were ignorant of racial problems, I don’t see how an eighteen-year-old Swiss immigrant would end up marrying a thirty-seven-year-old ex-slave, but somehow it happened. And the fact that Grandma Cox was white and Grandpa wasn’t—the reverse of how it usually was when you had yellow niggers in the family—was held up as a source of pride in our family. These differences were strongly emphasized in the family education. I didn’t grow up with any complexes about being less than anybody.

Also tucked away in the black treasure boxes was a certificate authorizing Grandpa to teach school. Here and there on the printed certificate from the Board of Education, the word “colored” had been inserted by hand to clearly define the boundaries of Grandpa’s maneuverability.

For me, the fact that coloreds and whites had their own schools and churches seemed the most natural thing in the world. I used to hear the grownups talking about slavery times and lynchings, but somehow I felt insulated from all that by either time or space.

In the immediate surroundings of Appleton City there were a couple of hundred people, and everyone knew everybody else. When everyone would go into town on Saturday nights to do shopping, I didn’t see any difference in the relationships between coloreds and whites. There were white friends who visited us and whom we visited. I never felt inferior to anybody. I didn’t even know we were poor. One of the local families, the Braunbergers, owned the town’s drugstore and had a son a couple of years older than me. His clothes were always passed on to me and were a source of happiness and anticipation; for me, such generosity did not mean that we were poor but rather that the Braunbergers were exceptionally nice people. The only time I felt lacking was the year Santa Claus forgot to drop by our house on Christmas Eve. But really, that was his fault and had nothing directly to do with us.

Mama worked hard all summer long growing everything she could, and she would spend fall canning what she had grown. Then there were the chickens and ducks, as well as the hogs that Papa butchered every now and then. I never felt we were poor, since there was always something to eat in the pantry and the smokehouse.

Finally, the great day came when I could start school. I had already spent some time there, as Mama would send us with Mary Jane whenever she had to go somewhere. It was one of those country schools that combined all the grades in the one and only classroom. The teacher would teach each grade in turn and everyone else in the room would hear what was being taught, no matter their level. This preschool experience, plus my constant presence in the same room at home where my sisters did their homework, allowed me to learn how to read and write before I officially started school. And when I did, I skipped first grade and went right into second. I started out being a proud nigger.

Because many of our neighbors had gone north, there were only three of us in class during my first year of school: my sister Marleeta; Shirley Burton, the daughter of our neighbors; and myself. We were literally being tutored privately, a state of affairs that did not last. I don’t know if the funds were cut or what, but in the summer of 1943 Papa sold the farm and we moved about seventy miles northeast to Sedalia, where he started working at the Ford garage.

Sedalia was the town where Scott Joplin lived when he wrote “Maple Leaf Rag,” although we hadn’t heard of him yet. The only ragtime musician I had heard of was Blind Boone, and only for the simple reason that a distant relative of ours was his wife or girlfriend.

Sedalia at that time was a town with a population of about ten thousand. I don’t know what percentage was colored, but at school there were around three hundred students, all classes combined, first grade through twelfth. The colored part of town was on the north side of the Missouri Pacific railroad tracks, and the line ran through town in a north-south direction, on its way between Chicago and Denver.

The railroad line had run by our house in Appleton City, too—right along the edge of the big field where Papa grew cereals to feed the animals. All the hobos moving around in those days must have marked our place because there was not one who didn’t come to the house and ask for a meal. Mama never turned anyone away. She would feed them enough to last a couple of days. I remember her ritual of making up a package of ground coffee to give them when they left.

There was also a lot of military traffic on the railroad line in those days. Fort Leonard Wood was in the southern part of the state, and occasionally a train of prisoners would go by with guards on top and hanging off the sides with machine guns. I would run out with my wooden Tommy gun and pretend to mow down everyone on the train while waving my tiny American flag.

All along the edge of the field there were blackberry bushes separating our land from the railroad line. Mama made jelly, jam, and mouthwatering blackberry pies. At one time or another Junior worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant at the junction about twenty miles away. The trains stopped there to take on fuel and water while those who wanted refreshment could eat during the stopover. He would grab a freight to come home every night; they always slowed down just a little before our house before passing through Appleton City. One night he came in torn to shreds, bleeding all over, as if a lion or tiger had gotten hold of him. Having made the mistake of grabbing an express that didn’t slow down, he had jumped off anyway and landed, full force, in the blackberry patch.

Junior was the hunter in the family. In Sedalia he hooked up with a couple of friends and sometimes they would go hunting several times a week. All that their respective families could not consume was sold to make a little pocket change. I was eight years old when Junior finally let me start going along to carry the game bag. The main catch was cottontail rabbits, squirrels, and quail. Heading home after the hunt, they would stop along the way and do some target shooting with Junior’s .22. One day when they had all missed the target on the first shot, I asked for and was afforded a chance to try it out myself, and to everyone’s surprise, including my own, I hit it! So began my love affair with guns. From then on Junior let me carry the .22 while he carried the .410. I became a fairly good shot and began to knock off my share of cottontails, breaking from their cover, moving relatively fast.

When I was ten years old, I joined the National Rifle Association. I devoured any literature dealing with firearms I could get my hands on. Even as an adult the passion stayed with me, and after I moved to California I possessed a real arsenal. It included a beautiful Winchester Model 70, caliber 30.06, with a four-power telescopic sight. Up to two hundred yards, I could pick the hairs off a gnat’s ass. I used to go target practicing at a range just south of San Francisco. Most of the people on the shooting stands were members of the San Francisco Police Department, and I was always impressed with their ability. When they finished shooting at the end of the day on the pistol range of fifty yards, the centers of their targets were nothing but big holes. I shot a tight group myself and my results were as good as theirs.

The years rolled by uneventfully in peaceful Sedalia. I had good grades in school but didn’t learn much, especially about anything that was going to help open doors usually closed to colored people. The dream of all young colored kids was to finish high school and move to some big city and find a job. For us, the closest was Kansas City, followed by St. Louis and, if you were really lucky, perhaps Denver or Chicago. The alternative was to enlist in a branch of the military, a sure ticket out of flat, boring Sedalia.

The summer I graduated from high school my father’s brother and his wife and daughter—Uncle Harry, Aunt Rose, and my cousin Dolores—came to Sedalia on vacation from California, where they had moved about twenty years before. Dolores and I hit it off real good, and when Uncle Harry and Aunt Rose went back to California, Dolores stayed to spend the rest of the summer with us. When it was time for her to return home, Uncle Harry sent me a ticket as well as an invitation to live with them in California. Manna from heaven! California? That was like talking about going to the moon. That was someplace you never dreamed of reaching. That’s the land of milk and honey, where the streets were paved with gold.

2. Long Way from Missouri

I STEPPED OFF THE TRAIN in Oakland, California, at five in the afternoon on August 27, 1953. I was wearing my best mail-order clothes, straight from Chicago: a gray tam with a blue tassel on top, a gray shirt with a blue collar and sleeves, and gray pants. I also had on my gray suede and blue-alligator wingtip shoes with two rows of white stitches. I was ready to conquer the West.

Aunt Rose was there to meet me and take me to the house in San Mateo. Just seeing the Oakland–San Francisco Bay Bridge was frightening enough, but with all that water underneath, my asshole was sucking wind. When we got to the San Francisco side of Treasure Island, the usual afternoon fog was rolling in—the kind that’s thick, hugging the ground, moving fast, and enveloping everything in its path. I noticed no one else was getting excited, but my instincts were telling me to run the other way. Back home, when you saw thick clouds close to the ground like that, you knew to take cover because it meant a violent storm was coming—a tornado or something. I got up enough nerve to ask what it was, and when they told me it was just fog, it didn’t help much because I’d never actually seen fog before. I wanted to know what it did. They only laughed, but that was enough to convey their lack of concern, so I calmed down.

When we arrived at the house in San Mateo, my cousin Billy opened the door and frowned at the sight of me—hardly a warm welcome, to say the least. He was seventeen, the same age as me, and I learned right away that he would refuse to be seen with me in my current outfit. To go out with him I would have to wear some of his clothes, which, to me, were the latest thing in square: cashmere V-neck sweaters, khaki denims, and brown-and-white Oxford shoes. When he took me to the barbershop he really put one over on me. The barber was a friend of his, and without my knowledge, and without my consent, he had him cut off practically all my hair. He chopped off my rooster comb; I could have cried. Back home we kept our hair pretty short, but without ever cutting the hair right up front. We would load it up with grease and smooth it down over the top of our head, giving us the illusion of having long, wavy hair.

The next thing was to teach me how to walk. Billy didn’t seem to appreciate or be impressed with my Kansas City crawl, which to me was the latest thing in cool. He and a friend, Macao Porter, would walk on each side of me, and whenever I would forget and start rocking they would pull on each shoulder to make me walk straight. After a time, the two of them got my physical appearance to where it was acceptable to them. I went along with it all because I always wanted to be hip and fit in.

San Mateo was a middle-class suburb of San Francisco, not far from San Francisco International Airport. The first thing I wanted to do was to get a job washing dishes or something at the airport, but Uncle Harry said if I wanted to stay with them I would have to enroll in the local college. If I wanted to work I would have to move out and get a place of my own. So naturally I enrolled in San Mateo Junior College.

For the first time, I was going to school with whites. Out of three thousand students there were only three blacks the first year—it was very uncomfortable, to say the least. Each new class was invited to tea by the college president, and as always, I was the perfect example of timidity. We were so many that everyone stood, and when servers came around and handed us each a cup of tea on a saucer and another small plate with a piece of cake, I didn’t know what to do. As I glanced around, it seemed as if everyone else was eating and drinking, but in my nervousness and embarrassment I couldn’t figure out how they were doing it with both hands full. So I just stood there and suffered. Finally, I managed to put everything down and slip away.

One Saturday night shortly after I arrived, Billy got permission to use the car. We got sharp—by his standards—and headed for San Francisco. My first impression can be summed up by one word: wow! In 1953, the North Beach section of San Francisco was like a magnet or a drug for me. I was fresh from the country and didn’t understand much of what I was seeing, but the ambiance was such that I loved it at first sight. The sculptor Alexander Calder was the rage, and there was not a bar or club that didn’t have a mobile or stabile in his style hanging from the ceiling. The hungry i and the Purple Onion were relaxed, cool spots in those days, and inexpensive. Soon, one of my favorite places was Miss Smith’s Tea Room, up on Grant Street. I think it was a gay bar. At that time I didn’t know what that meant, but I liked the warm, friendly atmosphere. Then there were the jazz clubs, the Downbeat on lower Market Street and the infamous Black Hawk. I became a regular.

To finish our evenings, we always made the pilgrimage to Fillmore Street to down some hot links or ribs and sweet potato pie at Leonard’s or the Kansas City Hickory Pit, and then on to Jimbo’s Bop City. After the clubs closed to the public at two in the morning, the musicians in town would stay up and jam way into the next morning. I loved it all.

The area in North Beach originally called the Barbary Coast was going by the name “the International Settlement” when I got there, and it had become a street of striptease clubs and bars. That’s where I first met jazz musician John Handy. He was playing tenor sax in one of the clubs. We always stopped by to holler at him.

To earn pocket money I started cleaning houses after classes and on weekends. After a few months I chanced upon a job washing dishes in a restaurant at night. It was there that I met “Doc.” He had recently come out of prison, where he’d served time for a drug charge; in those days the repression was fierce when it came to drug arrests. I quickly joined the fraternity and discovered the benefits of reefer, ganja, the killer weed. Together, we discovered peyote after reading Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, recounting his experience with peyote.

In those days peyote wasn’t illegal; ten dollars sent to an address found in a magazine would get you a bagful. We sent off for some to conduct our own experiments. When it arrived, the bag was huge—enough to last for months. Take it from me, there is nothing on earth that tastes worse than peyote, and we would always have to struggle to get it to stay down. After about an hour, when we started feeling the effects, we would listen to records—Charlie Parker and other way-out contemporary stuff. Doc had one record of someone playing a prepared piano that made weird sounds. Doc and his friends used to talk about Sartre, philosophy, and stuff like that. I’d be sitting there, stoned out of my head, not understanding anything I heard, but it was hip to me, so I dug it and hung in.

During summer vacations I got a job at Lake Tahoe washing pots in a restaurant. Doc couldn’t get hired because he had done time, so we split the peyote and I left him behind in San Francisco. I wouldn’t see Doc again for another five years. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to us, peyote had been outlawed; maybe if we’d known, we would have made different choices. Doc wrote a friend in prison asking him if he’d like some cotton candy—code for peyote, which looks like eucalyptus seeds with a tuft of white cotton—and when the authorities who screen the letters sent to prisoners saw that, the pigs staked out Doc’s pad and, while he was at work, broke in and tore the place up to find out what exactly “cotton candy” was. They found the peyote. At this same time, I had constructed a mobile of peyote buttons and had it hanging in the middle of my room in Tahoe, in the place I shared with a Liberian student, Edwin Harmon, who was a fellow dishwasher. (He was studying criminology, and upon returning to his country he eventually became head of the police.) One day when I came in from spending some time at the beach, he showed me a headline in the San Francisco Examiner. Doc was making history. He was the first person busted for peyote after it was outlawed. He had already done time, so they hung a heavy sentence on him; he served five years before he got paroled. I was alarmed, in part because I was uncertain whether they knew that I had the other half of the stash. My mobile and the rest of the peyote went swimming, quick, in Lake Tahoe.

San Mateo Junior College only covered the first two years of university, and after I finished my second year I decided to move to Oakland. In my free time, I hung out at the California Hotel on San Pablo Avenue near Thirty-fourth Street, where they had mambo sessions every Sunday and I ran into people like dancers Ruth Beckford, Zack Thompson, and Kaye Dunn.

I’d gone to Oakland in part because it was where my sisters Irene and Mary Jane had settled. Mary Jane was a medical secretary, and Irene’s husband, Billy, was a mailman, notwithstanding his degree in business administration and experience as the director of a hospital in Kansas City. I found a room in Irene’s building for twenty-five dollars a month, and since my unemployment benefits were twenty-five dollars a week, it wasn’t too bad. That carried me through until I too got a job carrying mail, in December of 1955. In those days, civil service was one of the few places coloreds had a chance to get a job.

It was a funny coincidence that I became a mailman considering that the first time I was ever called “nigger” was in San Mateo by a Japanese mailman. I had leaned on his car and he shouted, “Take your hands off my car, nigger!” Remembering Mama’s philosophy, I dismissed him as someone stumbling on the path of righteousness. I didn’t know then that it had been only eight years since people of Japanese descent had been released from the camps they had been held in during the Second World War, after the U.S. government had made the racist decision to imprison them in the name of national security. What with that racial slur and the challenges I had faced being surrounded by whites at college (most of my white friends were gay, liked jazz, or smoked dope), I was beginning to become conscious of the dichotomy in American society. I remember the day in 1954 when the United States Supreme Court finally declared school segregation unconstitutional. We were sitting at the dinner table when we heard the news, and then Uncle Harry made a speech about how we were witnessing history being made. The real impact of that decision did not begin to sink in for me until much later, however, when Little Rock began to make headlines in the struggle for integrated schools.

Before Little Rock, though, was Montgomery, Alabama. It was there in 1955 that Rosa Parks, tired after a day’s work, refused to get out of the seat she had taken in the white section of the bus. This was the spark that started the prairie fire of the civil rights movement. A young colored minister, Martin Luther King, Jr., was elected head of the boycott committee, and the Montgomery bus boycott eventually led to the Supreme Court decision, in November of 1956, that bus segregation was unconstitutional. After the court’s ruling, many black churches were bombed in Alabama, but that didn’t stop the momentum. After the success of the Montgomery boycott, a new civil rights organization was formed, called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Martin Luther King, Jr., was elected as its head.

I was hearing about all those things beginning to happen in the South, but, as before, I was insulated from getting involved, both by geography and by my own ignorance. For me, these were more or less just interesting events in the news. The one story that had really jolted me was when Emmett Till, of Chicago, was visiting relatives in the South and was lynched for supposedly whistling at a white woman. He was fourteen years of age. That was the first time I felt that maybe Mama’s philosophy might be wrong. That was in the summer of 1955.

In the fall of 1957, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state national guard to prevent Negro students from entering Central High School in Little Rock. The conflict became so tense that President Eisenhower was obliged to send in federal troops to force the desegregation of Central and to protect the nine Negro students who were involved. The guard remained there for the school year of 1957–58, and Faubus finally closed all schools the next year rather than desegregate them. But the process had begun and would soon spread to most of the South. Another significant event occurred in 1957, in Africa. Ghana, the former “Gold Coast,” became independent.

Now that I was making what I considered real money, I got clean. My cousin Billy’s taste had really worn off on me, and now I looked Ivy League all the way. If it wasn’t British, I didn’t want it. I wore all my hair cut off and was going around with a clean head. According to Iris Vaughn, whom I later married, that was the reason she was attracted to me at a party and had wanted to meet me. We couldn’t seem to cool off our hot pants, so we got hitched after a short courtship.

Iris was from a rather economically secure family and was the only child at home. She had a brother, a dentist in Texas, and her mother had big plans to send her only daughter off to some bourgeois Negro university to find a “good” husband, but then here came a mailman. The night we told her we were married, my new mother-in-law chased me out of the house with the biggest butcher knife I had ever seen. She started throwing Iris’s clothes out the door, into the rain that was coming down like cats and dogs. We scooped up everything and split to my pad on Fifty-third Street in Oakland—one room with a Murphy bed.

Iris was a student at San Francisco City College, and every day after classes she would go by her mother’s house to see if things had improved. Every time, her mother would open the door, hit her in the mouth, then slam the door shut. After a few weeks of that I felt the need to do my husbandly duty and defend my wife, so I went with her. Not wanting to stretch things, I parked the car a few houses away. This time, when her mother opened the door, she pushed past Iris, jumped into her car, and burned rubber until she had pulled up just beside me. I thought I would shit. I didn’t know if she was going to pull out a gun. To my surprise, she smiled and said, “Why don’t you come on in?” It was clear she had made her peace with our marriage.

Financially, we weren’t making it at all with the $110 I was getting every fifteen days. Iris’s mother offered us a room in her home in San Francisco, and we accepted. Those were strained times. By now Iris was getting fat with pregnancy.

In the meantime I was getting quite expert at detecting which letters had cash in them. Some letters had that special spongy feeling when there are several loose bills together in an envelope. I quickly began to supplement my miserable income.

After about a year my employers were on my case. And I knew it. They started planting letters with cash in them, but I was so cocky by then that I was ripping off even the plants. Usually, I would go to a toilet somewhere, open the letters, put the money in my pocket, and flush everything else down. When the fatal day arrived, I had ripped off two letters but only opened one and put the other in my pocket to open later. That was the day they decided to see if they could catch me dirty.

That wasn’t the first time I had been busted. Back in Sedalia, during my four years of high school, I had worked at the grocery store on our side of the tracks. During the school year I was paid six dollars a week for four hours of work a day, plus twelve hours on Saturday. In the summer, I was paid ten dollars a week for twelve hours a day, six days a week. For that I did deliveries and also worked as a stock boy, janitor, and cashier. I never got a raise, so I regularly supplemented my income from the cash register. My boss, Mr. Kantor, knew it. He accepted it because I never exaggerated and I was a good worker, and everything went fine for four years, until it was time for my graduation ceremonies from high school. There were expenses that I just couldn’t cover with my salary, and I didn’t even consider asking Papa, since I had started working at the age of thirteen and had always had to pay for anything I wanted or needed. So, when I closed the store the night before the graduation ceremonies, I left the back door open and returned after midnight. That time I took the whole moneybag. I knocked stuff around to make it look like a burglary, then stashed the bag in the weeds in the alley behind the house and went to bed.

The next morning I decided to take my shoes downtown for a professional shine. I wanted to be as sharp as possible for my graduation. In going up the alley, I couldn’t resist picking up the moneybag and putting it in my pocket. On my way back home I saw a police car coming and didn’t really pay it any attention until it approached and I saw Mama in the backseat. They pulled alongside of me and Mama said that Mr. Kantor wanted to see me. The two policemen were silent. As soon as we entered the store the policemen started searching me and pulled out the bag. They immediately put my hands behind my back and put on the handcuffs. Mama started screaming, “My baby, my baby!” I started crying and the police drove off with me, siren wailing. What a drama! While everyone was at high school for the ceremonies, I was in the city jail, in a cell straight from the Middle Ages: dirty, worn stone walls and a floor that looked like it hadn’t ever been cleaned. Hanging from the wall on chains there was a cot made from metal strips woven together, and a hole in the middle of the floor for a toilet. Whoever had been in the cell before must have been crazy or something because there was dried shit all over the walls, ceiling, and floor, with feathers stuck in it. I don’t know what that was about.

That evening my uncle—the only black doctor in town and highly respected—came to get me out of jail. The policeman released me to him and he drove me home. When we pulled up in front of the house it looked like someone had died. All the relatives and neighbors were there. They were fanning Mama, and I guess they thought they were giving me words of encouragement, but all I wanted to do was hide. I didn’t leave the house until the family insisted that I return to school. Even though classes were over, school was not officially out until Friday, but I was really ashamed to face my friends. On Wednesday I finally went back, and when I arrived I was, to my amazement and confusion, welcomed as a hero. That was my first brush with the law. But the second time, in Oakland, things were different.

I spent twenty-four hours in jail before Iris managed to raise the hundred dollars of bail money. She couldn’t ask her parents; we weren’t about to tell them what had happened. After that, I immediately got a job driving city buses in San Francisco. When I finally went before a judge, I think it helped that I had a job and Iris was pregnant. I got five years probation.

During that time, I made friends with another bus driver, who lived half a block down the street. He drove San Francisco cable cars and had dreams about making films. One day he asked me to go with him to the Marina’s Yacht Harbor to help him try to simulate some underwater scenes. We were only in knee-deep water, but he was trying to film in such a way as to give the illusion of being in deeper water. He had an old Bolex camera wrapped in plastic bags held closed with rubber bands to try to keep it watertight. His name: Melvin Van Peebles, the man who went on to write, direct, and act in dozens of movies and plays, including the groundbreaking Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song from 1971.

My career as a bus driver came to an end a year later when the department of personnel ran a check on me and found out I had lied on my application. I said I hadn’t been busted before, but of course that wasn’t true. Inspectors came and pulled me off the bus I was driving.

By that time, my daughter, Kimberly, was born, and I couldn’t find a job, and neither could Iris. We had no marketable skills. I was getting forty dollars a week in unemployment compensation when I decided to go back to the university to acquire some skill that would allow me to be independent and not have to worry about the fact that I had been busted. With so many doors closed to Negroes, to be a professional was to become a doctor, dentist, or lawyer. I didn’t like the idea of working in a court, for obvious reasons, so I decided to register as a predental student at the University of California at Berkeley. I had been taught by my parents that if you were determined to do something, nothing could stop you from doing it. I truly believed that.

At the beginning of my second semester at Cal, I was forced to take a job or lose my unemployment check, and I was convinced I could deal with both a job and my classes. A friend, Willie Little, got me a job as an offset press operator in the place he worked. The job paid forty dollars a week, which was exactly what I was getting from unemployment. That hurt, but I had no other choice. It was hard to both work and go to class, and after a couple of months, I was about dead from exhaustion. That was when I lost my first illusions and it became obvious to me that determination is no guarantee of success. I applied for and received an honorable dismissal from Cal with every intention of returning at the first opportunity—which never materialized.

Working a lot of overtime, Iris and I were able to finally stand on our own feet. The first priority was to get our own pad—a two-room apartment across the street from Iris’s mother. Then Iris got a job as a keypunch operator at Union Oil. Finally, we could breathe for a minute. We even bought a car—a Triumph TR3. We hardly ever put the top up. As Edith Austin once said, “You might be cold, but you’re cool.”

About that time I met Mark Hanson, a tall, thin, slightly round-shouldered, mustachioed white man who wore thin metal-rim glasses. He had moved to San Francisco from Los Angeles because of the McCarthy anticommunist witch hunts, since every time he found a job or a pad, the FBI would pay a visit to his boss or landlord and he would find himself out on the streets. So he moved to San Francisco. He started to work with us as an Addressograph operator, working the machine that stamped addresses on envelopes. We hit it off immediately, even though I didn’t understand a lot of the political stuff he was talking about all the time.

Mark was surprised and disturbed when he discovered I was ignorant of so much of what was going on around me. He started bringing me books to read about the history of Negroes in America. Most were by the historians W. E. B. Du Bois and Herbert Aptheker. When he brought me Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, I was a little discouraged because I had never picked up a book that big before. It took me six months to get through it. I am forever grateful to Mark for opening this world to me.

In December of 1959, Fidel Castro’s revolutionaries seized power in Cuba (their work for the enfranchisement of blacks was widely admired by this country’s civil rights movement), and then in February of 1960, four Negro college students sat in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, demanding to be served. And with that, the civil rights movement in the United States was under way in earnest. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began to organize “Freedom Rides” into the South with the purpose of desegregating interstate transport and terminals. At the end of 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) finally decreed that all racial segregation on interstate trains and buses must end. That also applied to waiting rooms, and carriers were forbidden to use segregated terminals.

Walking on Market Street close to my work one day, I ran into my old friend Doc, who had just gotten out of the joint. It was a warm reunion, and as we talked, we found we had something new in common. Doc had been bitten by the photography bug, and through my job at the printing shop, I had too. We began stalking the streets of San Francisco together on weekends, looking for subjects, and I rented a flat and turned it into a lab and studio. The great Henri Cartier-Bresson was my idol, and his book The Decisive Moment held me spellbound. I was disturbed, however, by his disdain for doing his own lab work. I got so much pleasure from seeing my images develop that I couldn’t conceive of a photographer not doing his own lab work. In those days, I was a fan of Ansel Adams’s technical series, The Camera, The Negative, and The Print, and Adams too believed that doing one’s own lab work was sacred.

When a rare-photo exhibit came to the Museum of Modern Art on Van Ness Avenue, that was my first chance to see professional photographic prints. I took one look and was speechless. Up until that time I had only seen our own prints, and now before me were eight-by-ten contact prints made from eight-by-ten negatives by pioneering photographer Edward Weston. I almost decided to throw my cameras away.

Out in the world beyond my studio, the civil rights movement was really picking up steam. Negroes were sitting in all over the place. In the fall of 1962, whites rioted in Oxford, Mississippi, when James Meredith entered the University of Mississippi as its first Negro student. President Kennedy sent in five thousand army troops and federalized the state’s national guard to patrol the streets of Oxford.

I was also reading more. While I was laid up a couple of months with a case of pericarditis, I got into an author I hadn’t heard of before: James Baldwin. I was given a couple of his books—The Fire Next Time and Nobody Knows My Name—by my friend Nancy, who had come from New York after marrying my friend John Handy, who had just returned from a several-years’ stay on the East Coast playing with Charles Mingus. John and Nancy had met at the Blue Note jazz club, where she was working. Baldwin’s writings were real eye-openers. Up until then most everything I had read was history, but Baldwin was dealing with today. I had never heard the situation of Negroes articulated in such an eloquent, forceful manner. Fortunately, I had recovered enough to attend his event when he swung through San Francisco on a speaking tour. Nancy, John, Mark, Willie—we all went to hear him.

The big March on Washington was being planned at that time, and of everyone in our group of friends, it was John who made the trip in August of 1963. He had hardly been back a week when the church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, blew four little Negro girls out of this world. That was the straw that broke my back. That was too much. I had never felt such a sensation of impotency. Action was the only thing that could soothe my feelings, and I had to figure out what I could do. Willie, Mark, Nancy, John, and I decided to try to raise some money to send down to the SCLC in Alabama. John knew most of the musicians in town, and those he didn’t, Nancy did. So it was a natural idea to do a benefit concert. With one week’s work we managed to draw enough people to raise $1,300. Singer Carmen McRae, pianist Ahmad Jamal, saxophonists Sonny Rollins and Brew Moore, and John made up the program. Too bad it wasn’t recorded.

The benefit relieved some immediate pressure, but what could we do for the long run? At the time, CORE appeared to be the most dynamic civil rights organization in San Francisco, so we all joined.

It was around this time that I had begun to hear of Malcolm X, the Black Muslim minister. He seemed to be a bad nigger. They were always putting him on TV or the radio with some Uncle Tom or an endorsed spokesman for the system. I really admired the way he would eat them up and spit them out in little pieces, all the while remaining cool, calm, and polite. I didn’t know it then, but his ideas would become important to our later efforts in the struggle.

I didn’t last long in CORE—maybe around six months—but it was long enough to be elected as chairman of the public-relations committee. It was one of those elections where someone is nominated and then nominations are immediately closed because no one wants the job. You’re in by acclamation. We did manage to turn out some nice newsletters, in part because we went to my job after-hours, going in after dark and working all night to produce our pages before the employees arrived the next morning.