Dwight Garner

Rachel Kushner’s ‘The Mars Room’ Offers Big Ideas in Close Quarters

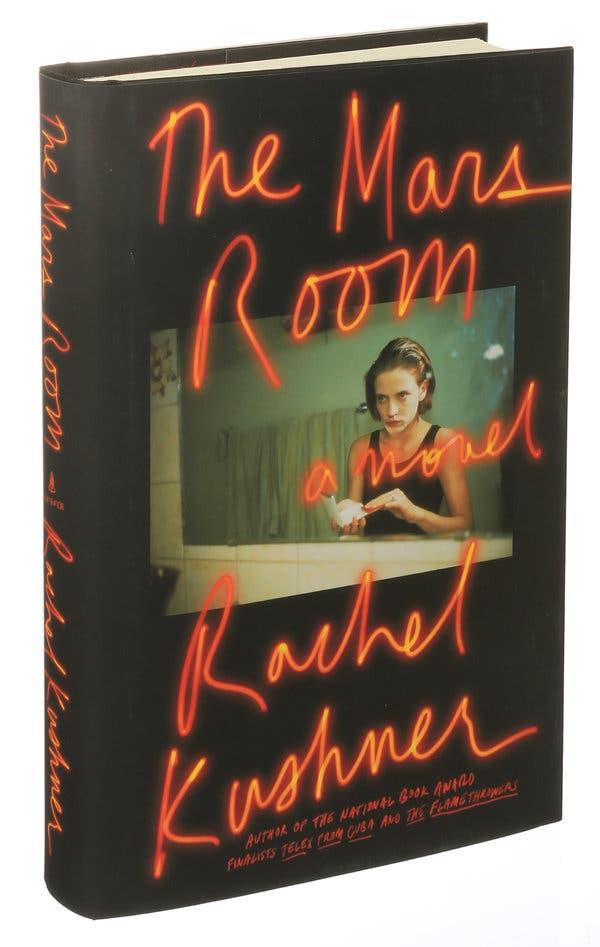

The title of Rachel Kushner’s new novel, “The Mars Room,” refers to a San Francisco strip club. It’s not just any strip club, either. The Mars Room is “the worst and most notorious, the very seediest and most circus-like place there is.”

The book’s central narrator, Romy, works there giving lap dances. She has a sense of humor about the place. “If you’d showered you had a competitive edge at the Mars Room. If your tattoos weren’t misspelled you were hot property. If you weren’t five or six months pregnant, you were the it-girl in the club that night.”

You sense early in this novel that you’re entering Mary Gaitskill, Denis Johnson and Charles Bukowski territory. Sexual and moral boundaries will be transgressed; every shirt sleeve will be a crusty shirt sleeve, every piety an impiety, every angel a grievous angel.

That the novel’s cover image is a well-known photograph by Nan Goldin, the downtown laureate of sex and death and youth and needle tracks, is another tell, at least for those readers who don’t mistake the young woman in the 1992 photograph for the actress Elisabeth Moss.

“The Mars Room” is the follow-up to Kushner’s “The Flamethrowers” (2013), one of this decade’s indelible novels. That novel has a sense of escape, of IMAX Western vistas. Its protagonist, Reno, is a young woman who races a Valera motorcycle on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

“The Mars Room,” on the other hand, is all about constriction. Like Alfred Hitchcock in many of his best films, Kushner works here in close quarters. This novel shifts from the strip club to a more claustrophobic venue: a women’s prison in California’s Central Valley where Romy is sent — she gets two consecutive life sentences — after killing a sicko who stalked her.

This novel has many angles, many tempers. We witness Romy’s anarchic, drug-addled, near-orphaned childhood in San Francisco. Kushner offers a great, subversive portrait of that city. This section reads a bit like a left coast retelling of Jim Carroll’s classic about teenage life on Manhattan’s mean streets, “The Basketball Diaries.”

Romy’s San Francisco “was not about rainbow flags or Beat poetry or steep crooked streets but fog and Irish bars and liquor stores all the way to the Great Highway, where a sea of broken glass glittered along the endless parking strip of Ocean Beach.”

Like Reno, Romy knows cars. Before she is sent away she only slightly improbably drives a 1963 Chevrolet Impala, as magnificent a thing as God ever deposited onto four wheels.

Before long, heartbreak is piled upon heartbreak. When she’s imprisoned, Romy is a single mother with a young son named Jackson. Her mother cares for the boy until she dies in a car crash. After that, Romy has no idea what happens to him, nor do we. She’s lost her parental rights; Jackson vanishes into foster care.

Other characters are folded into the mix. Chief among them is Gordon, a stalled young academic who teaches in Romy’s prison. He brings her books; he begins to have feelings for her. Also there’s Doc, an imprisoned cop who went rogue. The scenes of his nasty past life are so pulsing you start to think that Kushner has a hard-boiled, Charles Willeford-type thriller in her.

Kushner’s portrait of life inside the women’s prison is grainy and persuasive. It’s all here: the lice treatments, the smuggling of contraband in rectums and vaginas, the knifings, the cliques, the boredom, the heinous food. About a grim hunk of Thanksgiving Day meat, one inmate comments, “People say it’s emu.”

Kushner smuggles her share of humor into these scenes. Like Denis Johnson in “Jesus’ Son,” a book this novel references, she is on the lookout for bent moments of comic grace.

In one scene, the inmates decide to throw a party and begin to surreptitiously save their meds in order to crush them into a punch. Romy gives this tipple a name: “a short island iced tea.” Another of this novel’s memorable characters, a butch lesbian named Conan, goes on a woozy riff about how cows are righteous because they dress in nothing but leather.

If these prison scenes have a flaw, it’s that Kushner has clearly done so much research that it weighs her down a bit. It’s as if she feels compelled to report everything she’s learned.

“The Mars Room” is a major novel, a sustained performance, one that broods on several exigent ideas. The sense of constriction I mentioned above plays out in many ways. Nearly every character has had radically limited options from birth.

Romy had academic promise as a kid but threw away her chance to go to college. After high school she waits tables in an IHOP. When she goes to Walmart to buy shoes for the job, she can’t help but deliver a profound, class-based riff on the type of shoes sold there, made for dead-end jobs and just a step above the footwear issued in institutions like prison. They’re nearly training shoes, she thinks, for incarceration.

There have always been echoes of laconic but resonant writers like Robert Stone and Don DeLillo in Kushner’s prose. In “The Mars Room,” she dwells as well on Dostoyevskian notions of evil. There are so many types; so few are recognized.

“There were stark acts of it: beating a person to death,” Gordon, the academic, thinks. “And there were more abstract forms, depriving people of jobs, safe housing, adequate schools.” In “Naked Lunch,” William S. Burroughs put this idea in slightly different words: “The face of ‘evil’ is always the face of total need.”

There’s an extended and winning juxtaposition, in “The Mars Room,” of the writing of two men who sought escape from society’s constraints: Henry David Thoreau and Theodore J. Kaczynski, the Unabomber.

Kushner quotes Kaczynski at some length, and the idea is floated that these men are not so different as it might seem. Kushner makes one want to learn about Kaczynski all over again.

“The Mars Room” moves cautiously and slowly. It prowls rather than races. It is like a muscle car oozing down the side roads of your mind. There are times when you might wish it had more velocity, more torque, yet there are reasons it corners cautiously.

Like someone wary after a bad accident, Romy says, “I did not see any doom in the road.”

Follow Dwight Garner on Twitter: @DwightGarner.

The Mars Room

By Rachel Kushner

338 pages. Scribner. $27.

A version of this article appears in print on , Section C, Page 6 of the New York edition with the headline: From a Strip Club To a Prison Cell. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

See more on: Rachel Kushner