Echomedia Berlin

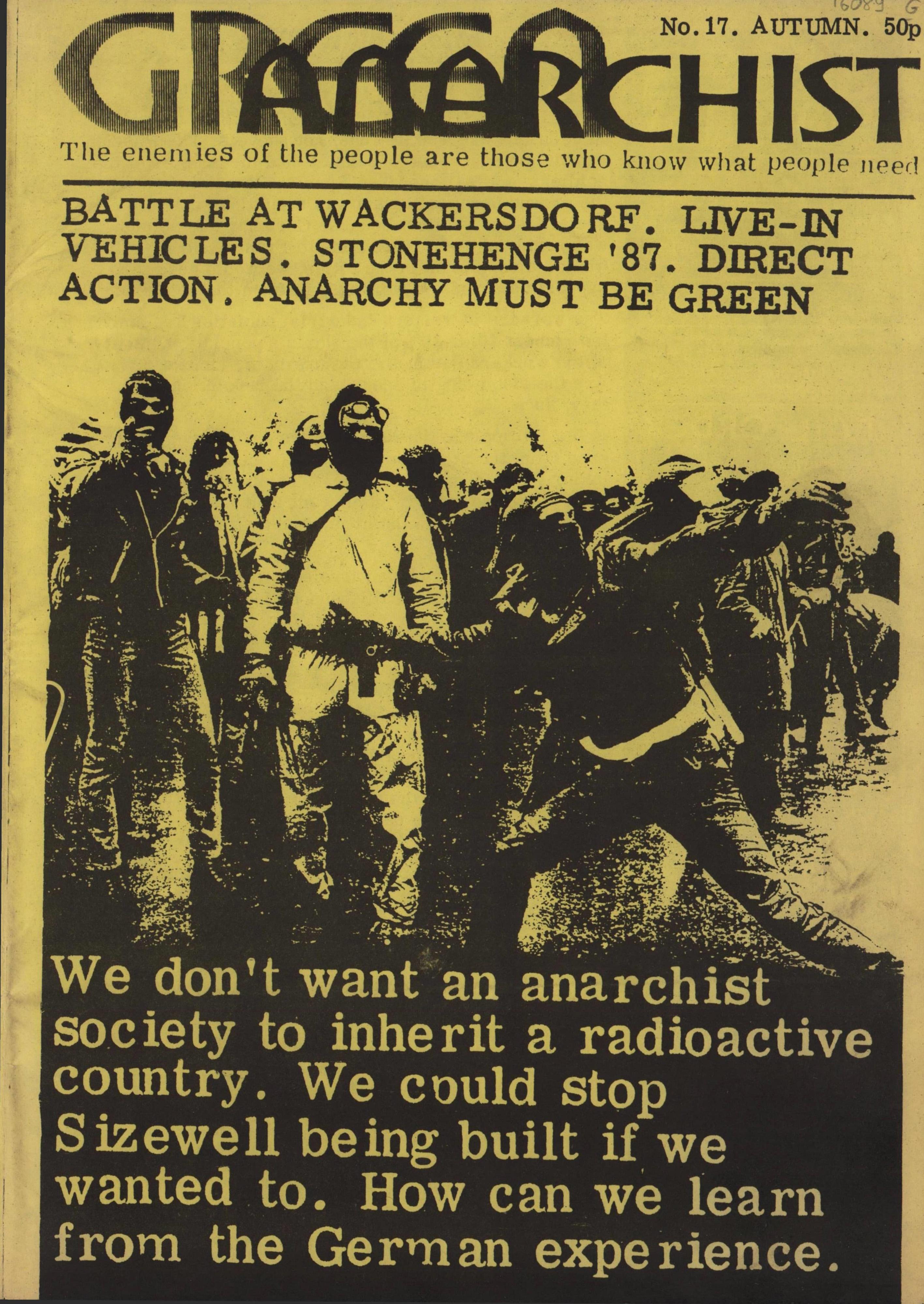

Battle at Wackersdore

We don’t want an anarchist society to inherit a radioactive country. We could stop Sizewell being built if we wanted to. How can we learn from the German experience.

IN THE 70s the SPD/FDP government planned to build a nuclear cemetery and reprocessing plant in the Wendland. The program ne was driven on by autarky and military interests; and the reprocessing plant was meant as a step towards the German nuclear bomb.

However by the late 70s a resistance had developed against the planned plant which was carried out at both local and national levels. The highlight of the resistance was a demo of 120,000 people. The occupation of a research area was proclaimed the ‘Free Republic of Wendland’ in 1980. The Prime Minister declared that it was not politically possible to carry through the building of the reprocessing plant in the Wendland. A victory to the peace movement.

In 1981 news leaked out that the plant was to be built in Bavaria. The Bavarian Prime Minister, Strauss, has played a major role in building up the nuclear programme and remilitarisation. The location chosen for the new plant was Wackersdorf in the Oberpflaz — an area known to be rural, catholic and conservative. As soon as this information was found out, a demonstration of 2,000 was held in the capital of the Oberpflaz.

Citizen Initiatives were set up in nearby villages — resistance at this stage was confined to a local level but was surprisingly active.

In March 1982 a demo of 15,000 took place. Action included: processions to the site, legal proceedings (without any success so far; surprise, surprise), a summer camp with sporadic attempts at building huts, and acts of sabotage against drilling equipment.

In February 1985 the location of Wackersdorf for the new reprocessing plant was announced and the resistance expanded rapidly. Anti-nuclear activists from outside the region made contact with local anti-nuclear protestors. The first action carried out by national groups was a summer camp on the site which was then still a wooded area. Many residents supported this attempted occupation, and the movement became more radical.

After a demo in October in Munich of 50,000 people, Wackersdorf became a national focus of protest. A street festival in the evening was brutally raided by the pigs — with 200 arrested. The state was trying to divide the movement.

On the 14th December, three days after the start of the clearing, 50,000 demonstrated on the site at Wackersdorf. 3,000 started to construct huts — a whole village sprang up. Two days later the pigs evicted the village. 869 (75% outsiders) were charged. A week later a second village of 70 huts was built. On the 7th January 1986 this village was raided by 5,000 pigs. 734 people were arrest and charged. The two villages played an important role in the resistance as a great number of the middle class residents took part in illegal actions.

After a carnival of 10,000 demonstrators in Feb.’86, it was decided to hold a procession to the site every Sunday. 1,000 — 3,000 people participate in these ’Sunday Processions’ every week. During one procession an elderly woman died after being maltreated by the pigs.

On March 31st 100,000. people demonstrated at the now completed security fence. After protesters began to make holes in the fence the police fired CS gas into the crowd for hours. A man suffering from asthma died from the gas.

By this time the state was becoming worried as the resistance threatened to become uncontrollable. Some of the protestors in Wackersdorf decided that, instead of arguing with the government (who would not change their minds even after Chernobyl), they would take direct action against the site. The fence was turned into a Swiss cheese full of holes; water cannons and pigs were attacked with catapults and petrol bombs. The residents gathered stones and handed them to militants.

It was obvious to the pigs that the situation was out of hand. The whole forest around the fence was shot with CS gas grenades; a pig helicopter dropped CS gas on a peaceful crowd of 30,000 people (including kids and elderly people). Panic changed into revenge as activists burnt meat-wagons and a unit of 60 pigs was beaten back. 300 pigs and 600 demonstrators were wounded.

In June ’86 another 30,000 people demonstrated at the fence. The more offensive tactics of the pigs showed the limitations of mass militancy. In the next months the building site was turned into a virtual fortress; the woods which had served as protection against the pigs and water cannons were cleared. Whole hills were removed. Militant actions at the fence became less possible.

At this time the Green Party and the SPD tried to divide the protestors through the question of violence. They said that the peaceful residents should hand over militants to the pigs. Attempts to split the movement could be seen at a commercial concert in July ’86 at which musicians told the audience not to go to the fence and to avoid violent action. Behind the fence police were now prepared with plastic bullets.

The division could also be seen when the Green Party withdrew sponsorship from a demonstration in Munich in October ’86. They were afraid that violent action could lead to losses in the Bavarian elections the following weekend. When the Greens dropped out, the courts prohibited the demonstration; 10,000 people still took part in it.

In October protest took on a new dimension. Because protest at the fence had become futile, the attack was shifted to the companies producing for the site, the site roads, the courts, the cop shops etc. The building companies, after Chernobyl, were more intensely targets of uncontrollable attacks. On the Blockade days the actions ranged from non-violent ‘go-slow blockades’ to blockading factories and burning barracades on the roads leading to the site and chopping down electricity pylons. As the political parties discouraged people from taking part in direct action, activists became more militant.

Today the anti-reprocessing plant movement is in crisis. A lot of the activists are worn out; and a wave of 3,000 charges and sentences has affected the resistance. The local movement itself is torn apart by radicals and conservatives who are even ready to have talks with the pigs. Nevertheless the two currents in the movement are expressed in the planning of mass demonstration combined with blockade actions in the Autumn of ‘87 — a compromise in every respect.

Echomedia Berlin