Some paragraphs need work error correcting whilst reading the source PDF on the other half of your screen.

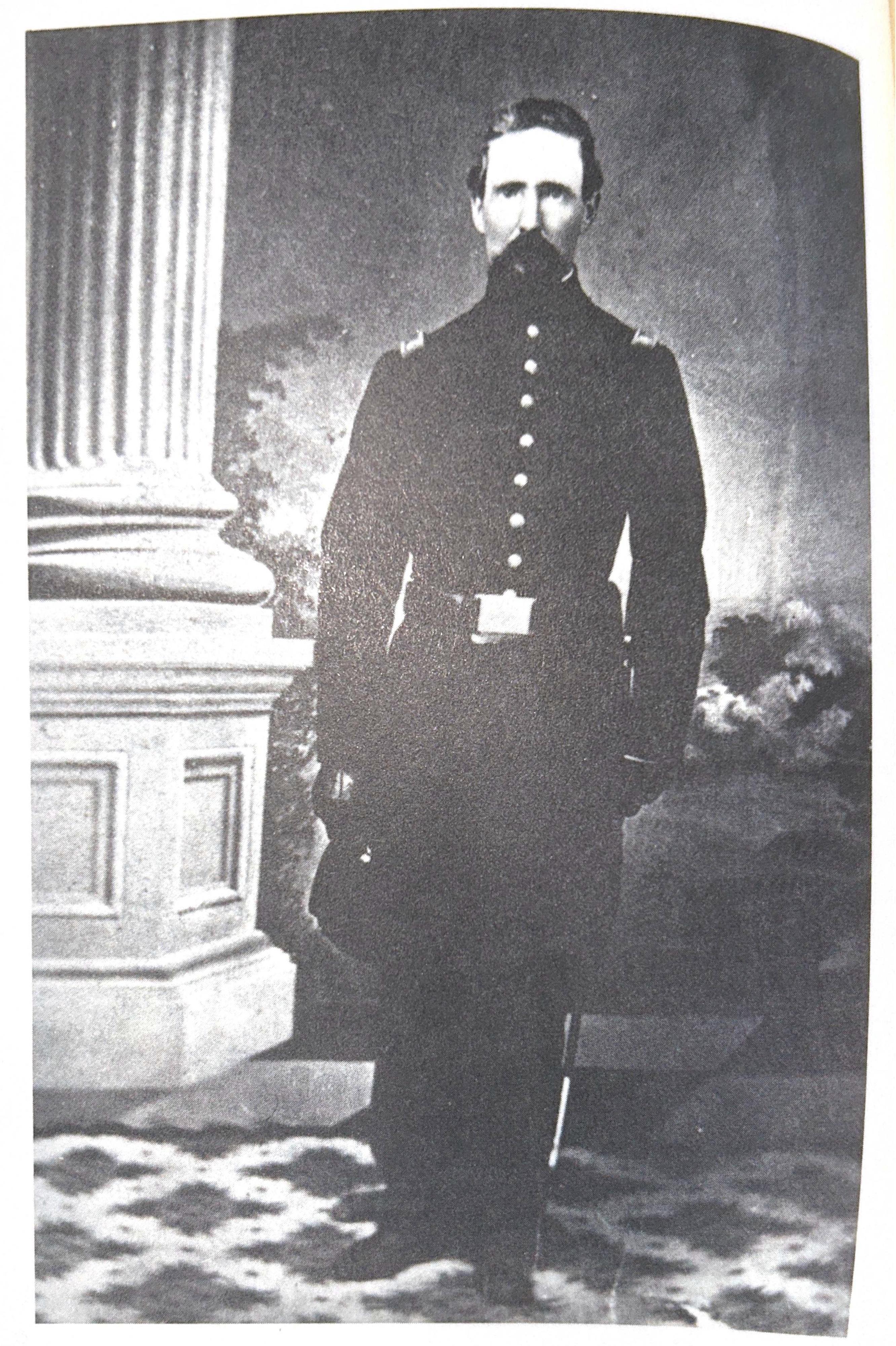

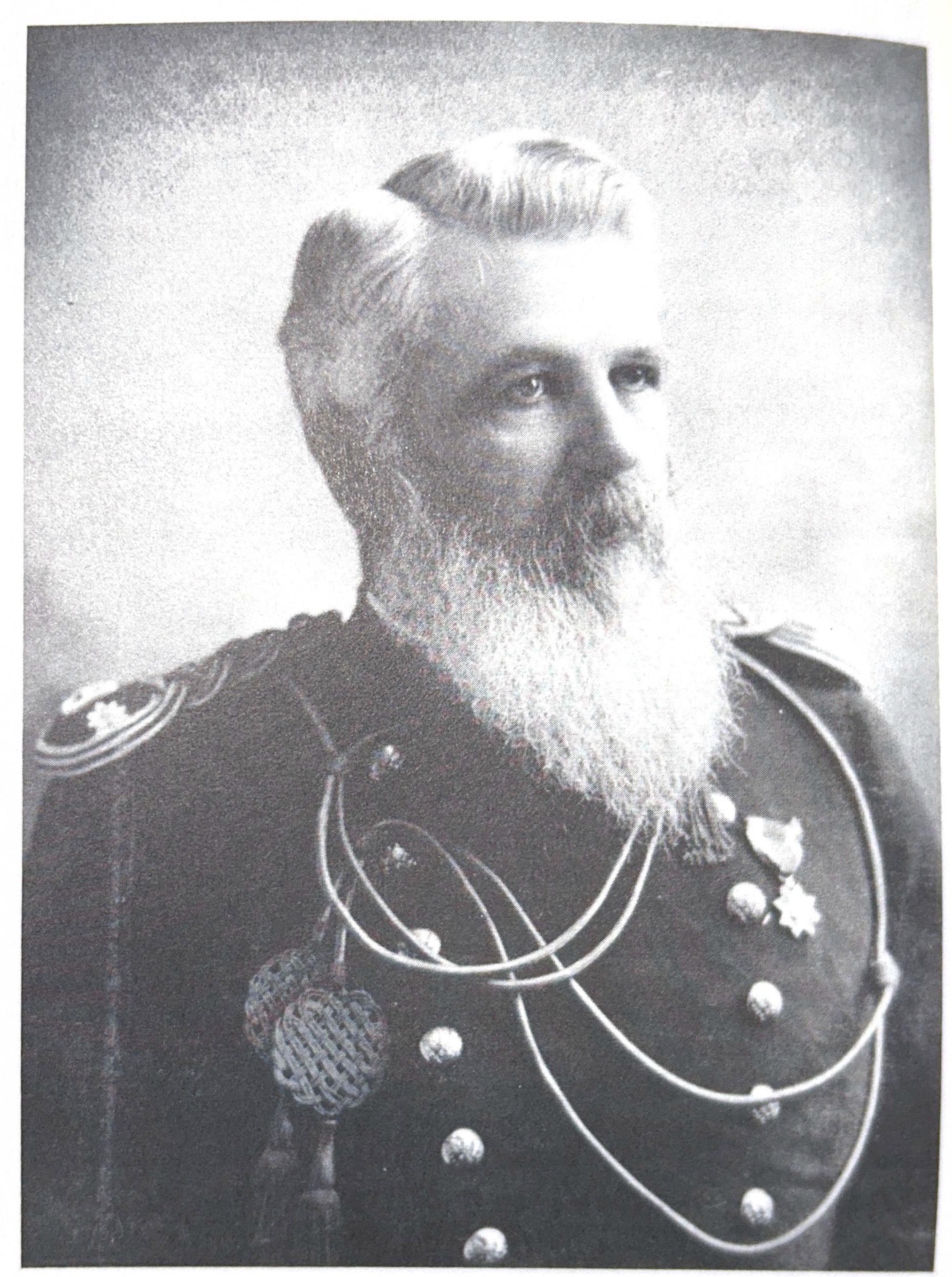

Edwin Russell Sweeney

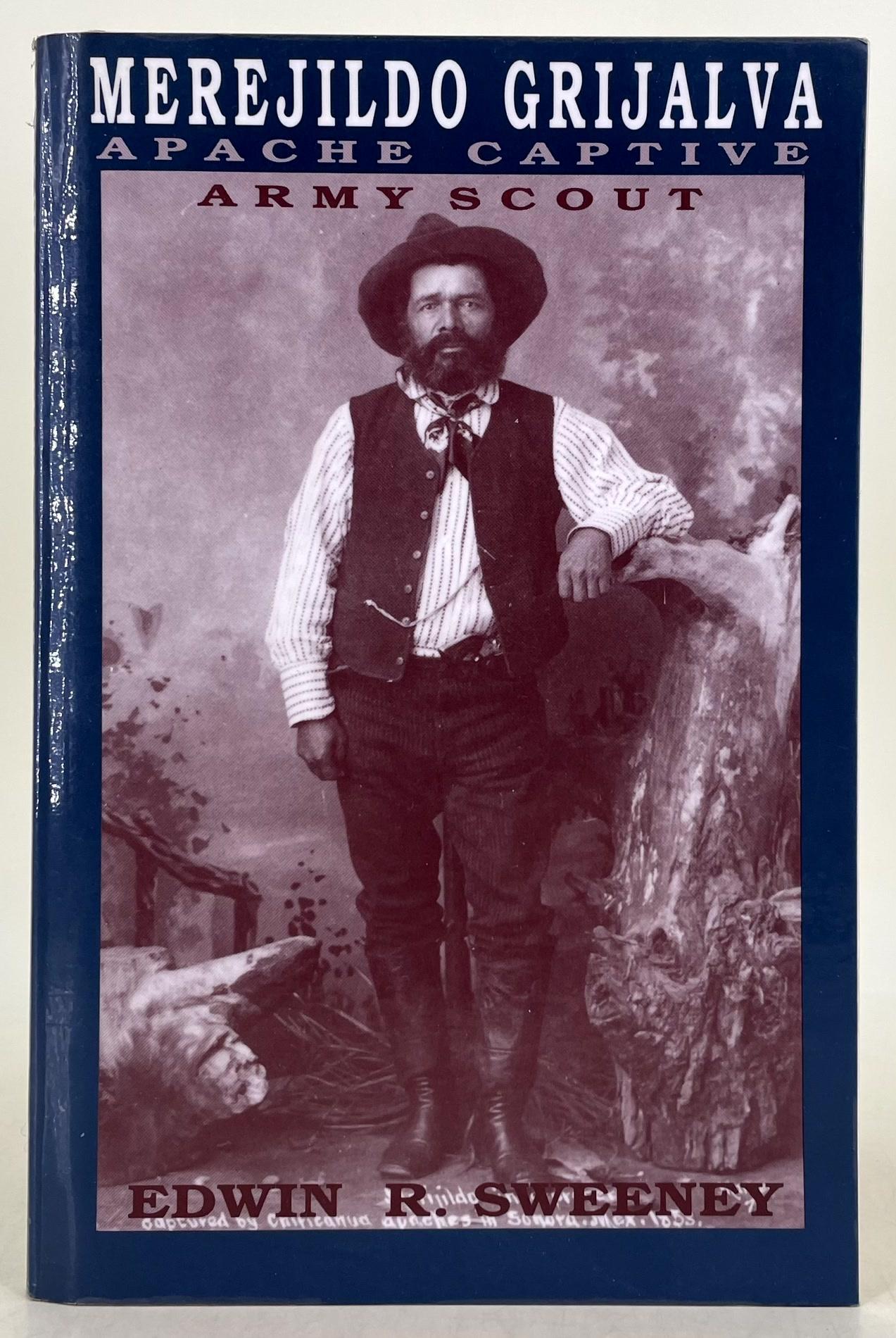

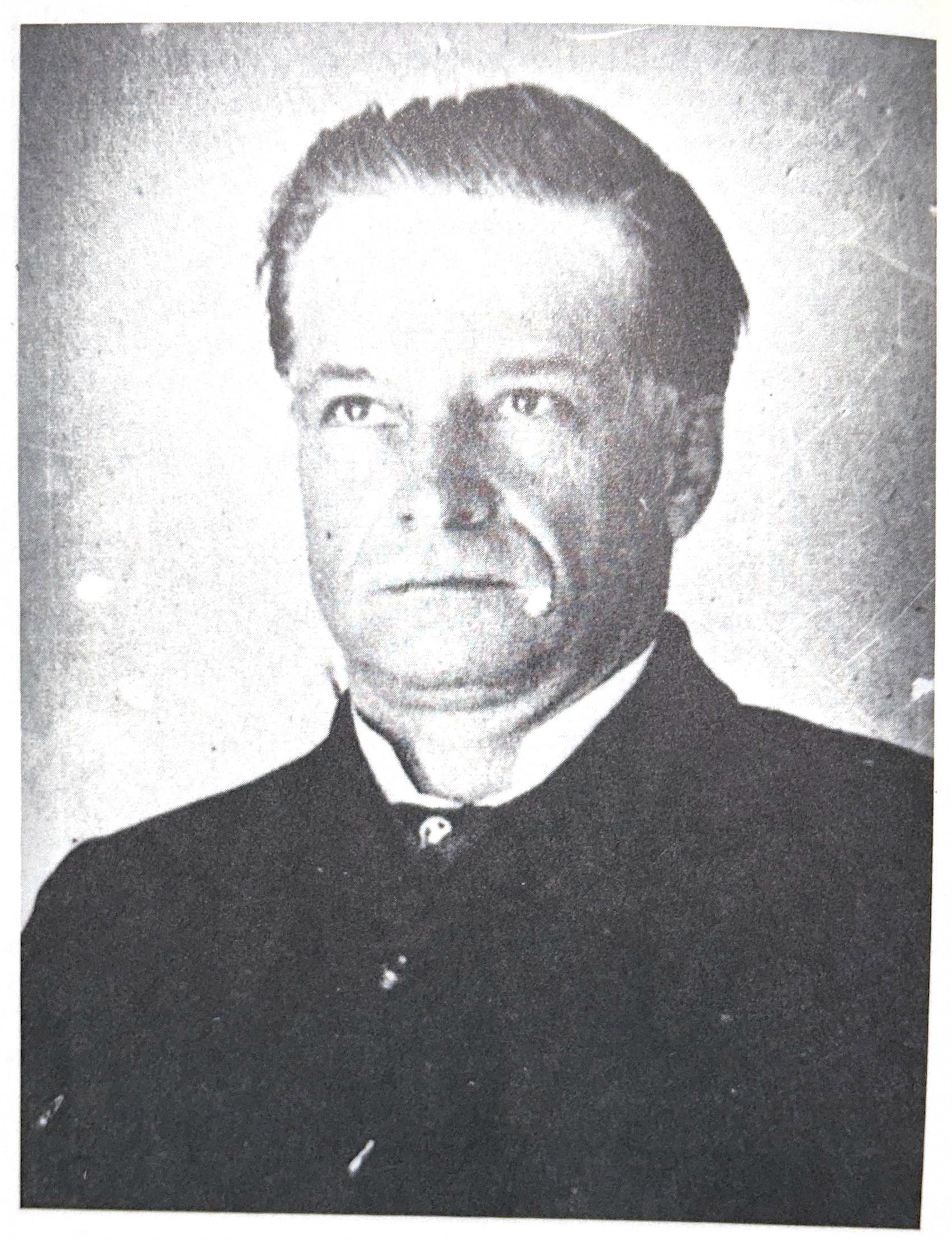

Merejildo Grijalva

Apache Captive, Army Scout

Chapter Two: From Apache to Scout

Chapter Three: With the Sagacity of a Bloodhound

Chapter Four: Duty at Camp Wallen

Chapter Five: Last Years of Scouting

[Front Matter]

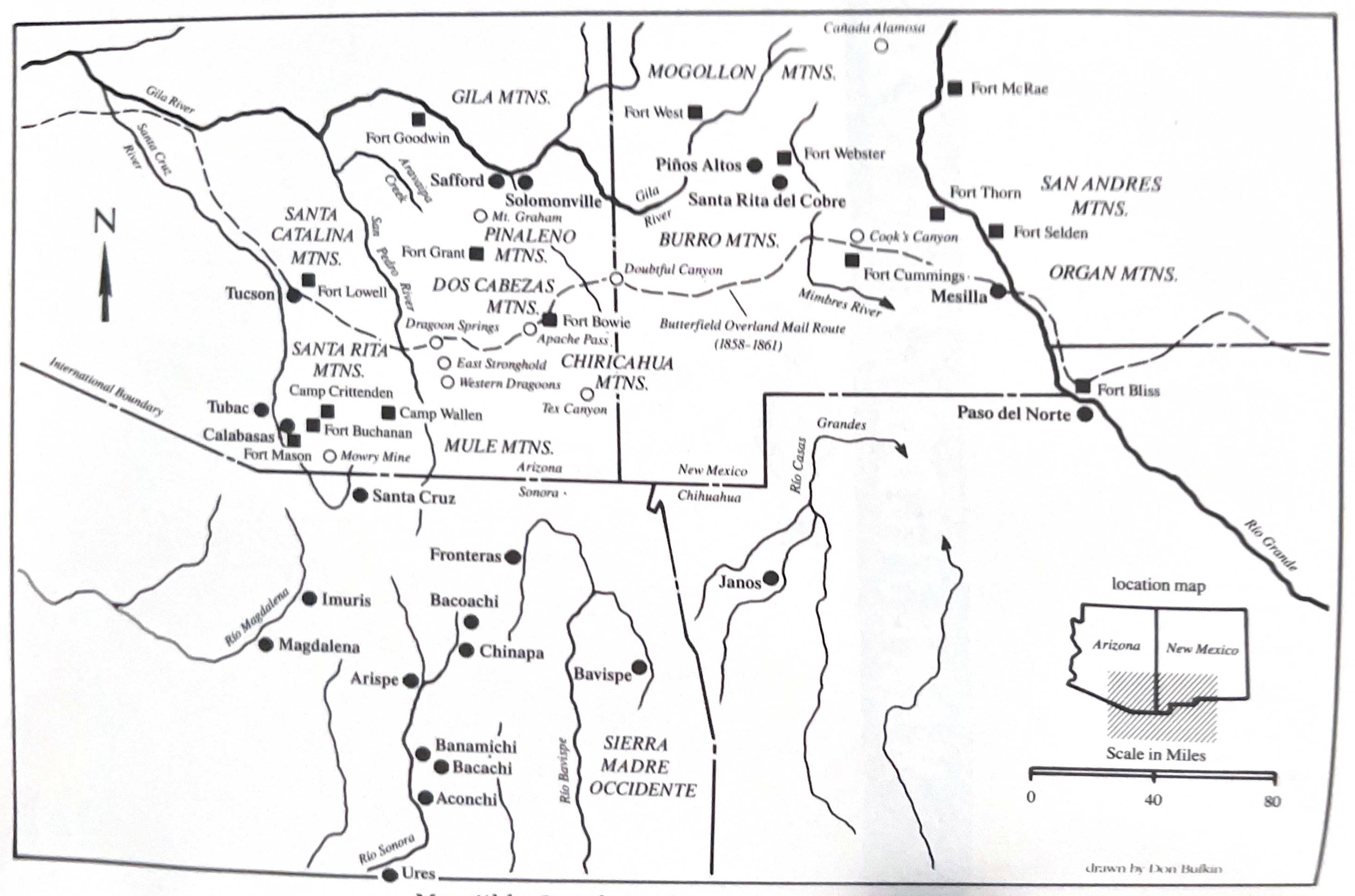

[Map]

[Title Page]

Merejildo Grijalva

Apache Captive

Army Scout

by

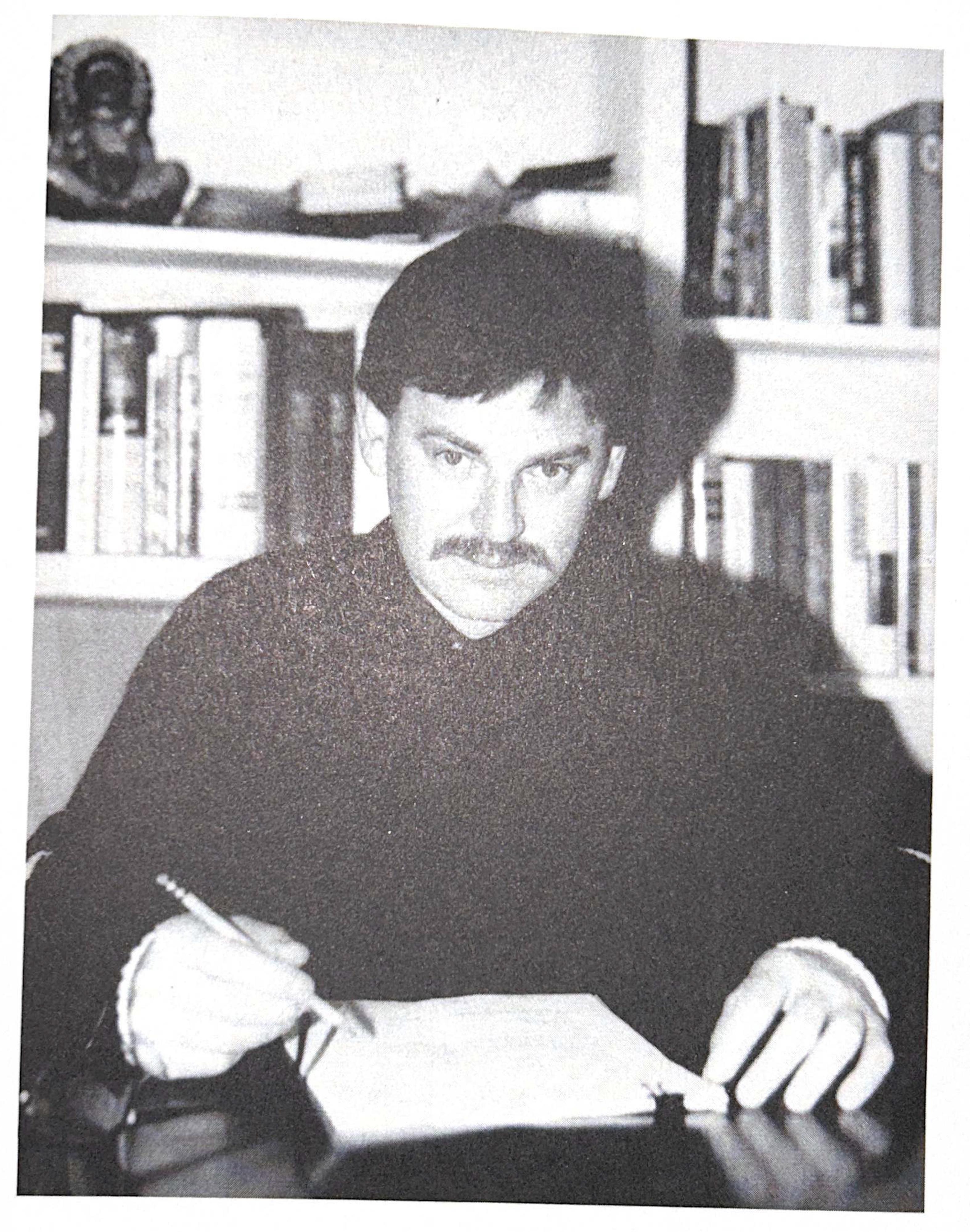

Edwin R. Sweeney

Texas Western Press

The University of Texas at El Paso

Southwestern Studies Series No. 96

[Dedication]

To

Jim & Gwen Ramatowski

of

O’Fallon, Missouri

For Their Friendship

Acknowledgements

I wish to take this opportunity to thank those who have helped me during my research on Merejildo Grijalva. Thanks to Lori Davisson, research historian at the Arizona Historical Society; Allan Radbourne of the English Westerners’ Society; Dan Aranda of Las Cruces, New Mexico; Rick Collins of Tucson, Arizona; Bill Hoy of Bowie, Arizona; and Alicia Delgadillo of Cochise, Arizona.

I am grateful for the help of Dan Thrapp, also of Tucson, and for the support of my wife Joanne and my three daughters, Tiffani, Caitlin, and Courtney.

Chatper One: Early Years

Merejildo Grijalva, the most capable and effective scout employed by United States troops in Arizona during the 1860s and early 1870,[1] was born about 1840 in Bacachi, Sonora. He was captured by Chiricahua Apaches in 1849 and remained with them until his escape in 1859. Four years later he began a career, which would span a decade, as a scout for the army against his former captors, the legendary Cochise in particular. A skillful guide often meant the difference to a campaign’s success or to its failure. This was especially true in the 1860s, before the practice of using Apache scouts to catch Apaches was employed. Virtually every successful operation carried out against Cochise in southeastern Arizona in the 1860s and early 1870s had one common denominator: its guide was Merejildo Grijalva. His invaluable services were recognized by every officer leading detachments into the field against the more mobile Apaches. One post commander, Captain William Harvey Brown, horrified over the prospect of discharging Grijalva because headquarters had decided to release a number of civilian scouts in a cost-cutting move to curtail expenses, implored the Assistant Adjutant General, District of Arizona, to reconsider. In his closing argument, he insisted that twenty soldiers could more readily be spared from the command [than] this guide.”[2] Such was the worth of a scout who completely understood Chiricahua Apache culture, knew their territory and probable camping areas, and was dogged and fearless once a trail was struck.

Most accounts have stated that Grijalva’s birthplace was Bacoachi, an old Spanish town and presidio located about sixty miles south of present day Naco, Arizona. Though, logical, the conclusion was incorrect as these writers were confusing Bacoachi with Bacachi, a lesser known, smaller hamlet near Banamichi. The mistake originated with Charles Poston’s and John Spring’s accounts. Poston, who left behind the most in-depth report of Grijalva’s life, wrote that his native village was Bacoachi.[3] Spring concurred, but he made one important distinction placing it one hundred miles below the Arizona border. This would rule out the presidio of Bacoachi and practically pinpoints Bacachi (approximately one hundred miles south of the line), which is situated a few miles east of Banamichi.[4] In 1891 the Arizona Enterprise, published in Florence, adds support to this argument by stating that Grijalva had been born in Buenachi, probably meaning Banamichi.[5]

Grijalva’s parents were Opata Indians, natives of Sonora. Like their ancestors, they toiled on one of the haciendas in the region. The Opatas had assimilated into Spanish society, becoming loyal and erstwhile allies in fighting the Apaches, their common foe. Bacachi, settled by the Spanish in the seventeenth century, was located a few miles east of Banamichi, another Opata settlement established in 1639. Situated on the banks of the Sonora River, about thirty-five miles south of Arispe, Bacachi was considered sacred to the Opatas, the site of important feasts and events. Renowned for its orchards and fruits, it was temporarily abandoned because of Apache raids during the eighteenth century. By 1800 Bacachi and Banamichi were prosperous settlements as the Spaniard’s military power had compelled the Apaches to make peace with Mexico and to live quietly near Spanish presidios.[6]

This period of tranquility was not destined to continue. In 1831 the Chincahuas went to war and a bloody cycle of revenge and retaliation began. Bancroft attributed these renewed hostilities to American’s War for Independence, which, when achieved in 1821, brought an end to Spanish rule. The newly formed government in Mexico City, winch may have discounted the Apaches as a military force was not responsive to the needs of its northern frontier. Most of Sonora s revenues were diverted to Mexico City for its own needs.

Theretofore successful presidio system, which had controlled the Apaches through a combination of rations and a strong military presence completely broke down. Not only were the Apache’s rations affected, but the state governments were compelled to slash salaries, food, and provisions for its own troops. As a result, by 1831, only one decade after Mexico won her independence from Spain, the Apaches, thoroughly dissatisfied and discontented, left their peace establishments for their old mountain homes. Virtually every Chirica- hua band went to war, a state of affair destined to last more than fifty years between some Apache bands and Mexico.[7]

Even as a youth at Bacachi, Grijalva undoubtedly saw firsthand the devastation wrought by the Apaches, in particular the Chirica- huas under their notorious war chief Miguel Narbona. In some ways these two individuals had parallel careers. Narbona was born a Chiricahua Apache[8] of the Chokonen band about 1800. At about the age of ten, Sonoran troops under Antonio Narbona captured him in a surprise attack on a Chiricahua camp. Miguel was reared in the Narbona household at Arispe, becoming literate and perhaps accepting Christianity. At the age of eighteen he escaped to his people and became among the most feared Chiricahua chiefs in Sonora during the 1840s and early 1850s.[9]

Miguel Narbona and Yrigollen[10] led the Chiricahua onslaught against Sonora’s northern frontier in the late 1840s. The Apache’s objectives were captives, stock, and loot. In addition, they almost forced the total abandonment of Sonora’s northern frontier. As their victories piled up, one after another, haciendas, pueblos, and presidios were abandoned, a direct result of the Chiricahuas merciless war parties. Towns and presidios along Sonora’s northern frontier were systematically assaulted by Chiricahua war parties; almost helpless, several settlements were deserted and left to the buzzards and the snakes. Grijalva’s life would soon be affected.

Their victories began in December 1847, when a Chiricahua war party attacked Cuquiarachi, a few miles southwest of Fronteras, killing fifteen villagers and capturing six. In early 1848 the remaining citizens deserted their homes.[11] That February, Miguel Narbona led a war party, consisting of Western Apaches and Chiricahuas, which obliterated the town of Chinapa, some fifty miles north of Bacachi, killing twelve, wounding six, and capturing an astonishing forty-two.[12] That summer, Miguel Narbona and his Chokonens lay siege to Sonora’s northernmost presidio — Fronteras. Conditions became so serious that farmers feared to work their crops, and its inhabitants were reduced to eating tortillas, the one food available. Finally, their will gone, the famished citizens abandoned the isolated presidio.[13] From 1831 through May 1848, these war parties forced the desertion of twenty-six mines, thirty-nine haciendas, and ninety-eight ranches in Sonora.[14]

These victories seemed to inspire the Chiricahuas and in early 1848 they launched a major campaign into the more populous interior of the state, which possessed more attractive booty and loot. Ravaging the countryside and striking widespread terror as they went, they spared none on their foray which extended as far south as Tepachi, Ures, and Alamos. In their wake, they left nearly one hundred victims. Near Ures they wiped out a party of twenty national troops and in another bloody encounter killed twenty-three and wounded sixteen villagers. Those they didn’t kill they carried into captivity.[15]

Grijalva wasn’t involved in any of these incidents, yet a few months later the Chiricahuas returned, his life would take a dramatic change. The documents aren’t entirely clear as to the date of his captivity because the important sources on Grijalva’s life were written years after the actual events. Yet these accounts, taken in conjunction with contemporary reports from Sonora, provide pieces to rhe puzzle as to the definite date of the incident.

Poston placed Grijalva’s captivity as occurring about 1850 by Chiricahua Apaches under the Chokonen chief Miguel Narbona.[16] One version placed the event as late as 1852,[17] while another source stated that it occurred when Grijalva was nine years of age, which would place the event at 1849.[18] Yet another account claims that he was a prisoner for eleven years, which, given there is no disagreement as to the date of his escape (1859), would place the year at 1848.[19] According to some accounts, his brother and mother were captured at the same time. The primary documents from Sonora clearly indicate that Grijalva was captured in March 1849, when Miguel Narbona led a war party of one hundred warriors w hich pillaged the settlements along the Sonora River south of Arispe.

Like many Chiricahua war parties, this one may have been organized to avenge an attack by national troops from Aconchi which, in mid-February 1849, had surprised a Chiricahua camp killing four, including a young son of a Chiricahua chief.[20] Ten days later, an Apache force of one hundred man struck the first party they encountered. Near Granados, about twenty miles due east of Moctezuma, they ambushed the mule train of Pablo Durazo, killing one man and taking some forty mules. Two parties were immediately dispatched in pursuit: one of forty-six nationals from Huasabas and another of twenty-six men from the Hacienda de San Antonio. The first group overtook the Apaches and in a sharp skirmish killed two and wounded several. The Mexicans suffered a loss of four dead. The second party, seeing they were outnumbered, cautiously kept their distance. Later that day the Indians killed two mail carriers between Bacadehuachi and Huasabas.[21]

Miguel Narbona’s band continued their foray at a leisurely pace to the southwest, breaking up into two or perhaps three groups and extending their raid south of Ures. One group clashed with Seri Indians, probably between Ures and Hermosillo, and killed several. Another band captured three women and two children, before retiring north along the Sonora River. Perhaps their target was Aconchi, to avenge the attack of the previous month. Yet they must have decided it was too risky a venture for they moved ten miles up the river into the mountains east of Banamichi and Bacachi.[22]

It was an opportune time for an attack. Only a few days before thirty men had left the area for the California gold mines. Eight of these were from Bacachi, Grijalva’s home town, which would be the target of the Apache war party. The morning of March 9, 1849, dawned like any other day for Merejildo and his brother Francisco at the ranch of Don Cornelio Felix. By mid morning they were in the fields, tending the ranch’s large flock of goats and sheep. Miguel Narbona’s warriors struck suddenly, and it was Chinapa revisited. The Justice of the Peace at Banamichi described what occurred:

The Indian Miguel [Narbona] with a numerous band surprised a ranch, less than one-half league from here, populate by honest and hard working families. The attack began about mi day when all the men were occupied doing their usual duties. The Indians took advantage of this and succeeded in taking the blood of defenseless people.

The first attack saw the Indians cutting down anyone in their path. Miguel Narbona’s furious assault killed seven men and five women and wounded five other men. Then, like their actions at Chinapa, they burned the town. The captives watched with horror as their homes went up in flames. Among the prisoners were four men, ten women, and a large number of children, including Merejildo, his brother Francisco, and perhaps other relations. Specifically mentioned as captives were three adult females with the surname of Grijalva: Maria, Petra, and Refugia. One of these may have been Merejildos mother. Within two hours the Apache’s work was done, and they gathered their captives and marched north along the Sonora River towards Motepori. Here they had another minor skirmish. From the river’s bank they toyed with the citizens and “fired at random, killing three more men and capturing two more people.

The authorities at Banamichi felt helpless: they could see rhe smoke and flames but were too afraid to send our a rescue party. Hours later, a relief force from Aconchi and Huepac rushed to Bacachi and discovered the awful scene. The buildings were still smoldering and bodies were scattered around the ranch. After burying the corpses, they halfheartedly followed the trail which led to Sinoquipe and into the mountains before they turned back. The Apaches were out of reach; Merejildo Grijalva was beginning a new life.[23]

Chapter Two: From Apache to Scout

According to what Grijalva told Poston, the Apaches carried their captives into Arizona, striking the headwaters of the San Pedro west of present day Naco, Arizona. Here, safe from pursuit, they moved at a more leisurely pace through Mule Pass towards their destination in the lower Chiricahua Mountains.[24]

Soon after arriving in camp, the prisoners were distributed among the band except for the adult males who were killed because it was said, “a mature man is dangerous.”[25] These defenseless captives were bound and turned over to the women, who dispassionately tortured them to death with knives and hatchets. Grijalva later told John Spring that a favorite practice was to whip “their helpless victims with the exceedingly thorny branches of the silvery cactus, called by the Mexicans cholla.”[26] The women prisoners, despite popular legend, were not raped or mistreated sexually. It was the children whom the Chiricahuas considered valuable for they were taken “to increase the tribe.” The boys were made slaves to the chiefs and the girls to the women. The adult female captives also became members of their new households.[27]

Grijalva, who would become known as “El Chivero” [the goat herder] to the Chiricahuas, apparently became a member of Miguel Narbona’s extended family, although his position was more of servant or slave until he gained the trust of his captors. Cochise was a member of this local group, second in command to Miguel Nar- hona. Grijalva soon made his acquaintance and in later years became a member of his extended family group. It is not known what happened to his mother but his brother was reared by the Western Apaches.

Life as an Apache for a young boy who could adapt to Indian ways could be both interesting and challenging. Several of these captives actually became prominent men and even leaders once they proved themselves successful at raid and war. Costales, captured as a youth in Chihuahua, became a leading warrior among the Chi- henne band in New Mexico during the 1850s, and there are other examples of this nature occurring through the 1880s. This phenomenon was probably a function of how early a boy was taken and how thoroughly he assimilated into Apache culture. Many of these young captives were adopted into an Apache family as if they were blood relatives. If the prisoner adapted well, and came to accept his position in the extended family group, he would have the opportunity to mature like any other youth. Some captives were not emotionally strong enough to endure this alien and oftentimes harsh way of life. Yet many did; some because they wished only to survive and others because they became as much an Apache as Cochise’s own sons.

Grijalva later recalled that the “treatment of captives was necessarily harsh.” In the beginning he helped the women gather wood, carry water, and perform menial camp work. Within a year he probably became proficient in the Apache language, and as he matured physically, began his training to be a warrior by fighting other boys to learn “the manly art of self-defense.” At the age of eleven or twelve the older men began instructing him in the use of the bow and arrow’ and horsemanship was also practiced. About the age of fifteen (the mid 1850s) Grijalva was probably accompanying the men on their raids into Mexico, holding their horses, and performing guard and sentry duty.[28]

The 1850s were a decade of tremendous change for Cochise and the Chiricahua Apaches. They continued to wage war against Mexico and by the latter part of the decade had another force to reckon with- Americans. Grijalva was in the middle of it all and experienced firsthand these dramatic events. The Chokonen band ranged from the Gila River in eastern Arizona south to the Sierra Madre in Mexico; occasionally they roamed east to the Rio Grande in New Mexico, while their western boundary was the San Pedro River in Arizona. Grijalva gained a tremendous amount of indispensable knowledge of the Chiricahua homeland during his period with them.

Shortly after Grijalva was captured an important development took । About one half of the Chokonens under Posito Moraga and YrigbUen decided it was time to make peace with Sonora. The other half under Miguel Narbona, Teboca, and Esquinaline continued at war with Sonora, allied with Mangas Coloradas. Mangas, who was Cochise’s father-in-law, was the most important leader within the Chiricahua tribe. His influence extended to every band, particularly Cochise’s Chokonens, and Grijalva soon became acquainted with him.

The split within the Chokonens actually doomed Yrigdllen’s ephemeral truce with Sonora. He eventually moved east into Chihuahua and joined the Chihennes and Nednhis at Janos, where a treaty had been made in June, 1850.

Miguel Narbona’s militant and bellicose Chokonens continued to raid in Mexico, joined occasionally by some of the younger warriors from the peaceful groups at Janos. Eventually someone had to pay the toll for this. Sonora organized a campaign to strike back at the Chiricahuas and the easiest targets were the Chokonens settled at Janos. On March 5, 1851, Colonel Jose Maria Carrasco struck Yrigollen’s Chokonens and Coleto Amarillo’s Nednhis, killing twenty- one and capturing over sixty.[29]

This attack profoundly influenced Chokonen — Mexican relations for the next six years. Each winter Mangas Coloradas joined other Chiricahua leaders and led destructive forays into Sonora. As Grijalva was coming to the age when older boys trained to be warriors, he may have accompanied Cochise or Miguel Narbona in the capacity as a novice or apprentice warrior. If so, the young man was kept out of danger as an injury to him would have been regarded a reflection on his leader’s ability. Undoubtedly, he served as a helper, perhaps cooking for the men or preparing their bedding.

After the death of the intractable Miguel Narbona in 1856 or 1857, Cochise emerged as the dominant leader of the Chokonen band. Grijalva became attached to Cochise’s extended family group, becoming a valuable interpreter for the chief. Almost simultaneous to this development was the arrival of Americans to Arizona. Although the Chokonens had been living primarily in U.S. territory, they had little contact with these interlopers because of the scarcity of traffic and the lack of settlements in their country.

Grijalva told Charles Poston that he first met Americans at Steins Peak, about forty miles northeast of notorious Apache Pass. This encounter may have taken place in the late summer of 1858, when a Chiricahua war party had assembled near the newly constructed stage station. It was here that Cochise, with Grijalva as interpreter, met the station employees. This war party was organized with the intent of attacking Fronteras to avenge a Mexican massacre of the previous July. Grijalva was probably part of the large war party which failed miserably as the citizens’ and trqops repulsed Cochise and Mangas Coloradas with cannon fire.[30]

Cochise returned to his rancheria near Apache Pass, found that another stage station had been established, and soon discovered other important changes in his world. Americans were beginning to make their presence felt in his country. American industrialists had begun developing the rich mines in the Tubac area, and troops had garrisoned a new fort, named Fort Buchanan, some sixty miles south of Tucson. Cochise, at war with Mexico, desired peaceful relations with these newcomers and Grijalva, as Cochise’s interpreter, would play an important role.

In December 1858 Apache Agent Michael Steck left his headquarters in New Mexico for a visit to the Chokonens. Steck born in 1818, had graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Phiiadelphia in 1843. He had come to New Mexico in 1848 as a contract surgeon for the army and in 1854 was appointed agent for Southern Apaches, primarily the Chihenne band. He quicklv gained the trust of their important leaders Mangas Coloradas and Delgadito. Arriving at Apache Pass in late December, Steck, with the assistance of James H. Tevis, the station keeper at Apache Pass, held a parley with Cochise and other Chiricahua leaders. Steck also met Grijalva, acting as Cochise’s interpreter, and the young Mexican evidently made a favorable impression on the honest agent. According to James H. Tevis, Steck had noticed that Grijalva was “a bright boy ... and was desirous of keeping [him] with him.” The agent offered Grijalva considered Steck’s proposal, but apparently the timing wasn’t quite right, for he still had Cochise to contend with. His escape would have to be accomplished when the Chiricahua chief wasn’t around.[31]

Steck returned again in March 1859 to distribute rations. Cochise left the next month on another foray against Fronteras; Grijalva apparently accompanied him for Tevis wrote that only “two warriors and a few women and children remained at Apache Pass.”[32] In June Cochise returned from his foray and later that month moved his band from Apache Pass west to the San Pedro River, probably camping in his favorite west stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. He had become concerned that the troops would charge him with stealing the stock of the Sonora Mining and Exploring Company near Patagonia. He had learned that some of his young men were on the raid, which was led by Parte, a minor leader of one Choko- nen local group. Cochise immediately seized the stock and even killed one warrior who defied him, according to what Grijalva later recalled. Then the chief sent two men, one of them Grijalva, to Fort Buchanan with eleven head of the stolen stock to explain what had taken place. Grijalva met Captain Richard Stoddert Ewell and returned the animals. The date was July 21, 1859.[33]

By this time Grijalva was approaching the age of twenty. For some reasons, not exactly clear, he had become disillusioned with life as a Chiricahua and decided to take Steck up on his offer. The legends abound as to the reasons for his decision; as usual there is little documentation which might reveal his motives. The primary sources — Poston, Spring, Proctor, Williamson, and Hughes, offer few clues as to his grounds which, in itself, may indicate that future historians may have over-analyzed this question when a simple answer might ave sufficed. The frequently unreliable John Cremony, who knew rijalva in the 1860s, said that he left because ‘he loved and was a beloved by a beautiful Apache girl whom he sought and obtained in marriage, was married less than a week, and was obviously enjoying it when a warrior forcibly abducted the object of his attention.”[34] Although this story seems a bit farfetched and is perhaps apocrypha, Grijalva was at the age when a young boy married, and his status as a captive would have had little bearing on this for he had become Chiricahua through and through.

Another version claims that his wife was killed by Chiricahuas while yet another states that Grijalva was angry because Apaches had killed five of his brothers.[35] Each of these stories ignores one important issue: that Grijalva, despite his assimilation into Chirica- hua culture, may have grown weary of life as an Apache and wished to return to his own people. With this in mind, when the opportunity availed itself, he decided to leave just as Miguel Narbona had some forty years before.

With Tevis’s assistance Grijalva was placed on a stage bound for Mesilla and was there met by Steck. According to Tevis, Cochise was absent on a raid into Navajo country. Tevis left the employ of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company between the middle of August and the beginning of September, 1859. He claimed that the mail company tried to convince him to stay and, when he refused, they trumped up charges against him, hiring Samuel Cozzens, a Mesilla lawyer, to make them stick.[36] In mid August Cozzens arrived at Apache Pass with Giles Hawley, Tevis’s superior. They were probably present to investigate Tevis’s alleged wrongdoings. Cozzens wrote a letter from Apache Pass on August 15, 1859, in which he indicated that the principal chief [Cochise] was absent and that Esquina- line’s followers were the only Indians camped at Apache Pass.[37] This would agree with Tevis’s recollections that Cochise was not present at the time of Grijalva’s escape. The Weekly Arizonian reported on September 29, 1859, that Tevis had been arrested earlier in the month but that charges had been dropped. These events are important in order to establish the date of Grijalva’s escape. Taking into account all the available evidence, it would appear that Grijalva left about the middle of August 1859, only a short time before Tevis severed employment with the stage line.

How Cochise reacted was not known; yet in all likelihood, he was disturbed by the arrangement. In 1872, after he had made peace with General Oliver 0. Howard, a longtime captive of his fled to an American settlement on the San Pedro. The chief was upset over this circumstance, and it is reasonable to assume that he had the same emotions when Grijalva escaped.[38]

Grijalva and Steck headed for the Apache agency near Fort Thorn, located on the west bank of the Rio Grande opposite Jornada del Muerto. Although the post had been abandoned the previous March Steck’s headquarters had remained there. Grijalva probably worked at odd jobs around the agency and, since he spoke Apache and Span ish, acted as interpreter whenever Steck required his services He also began to learn English. In 1860 Steck employed a Merejildo Sanches at a salary of $500 per year. One wonders whether Sanches could have been Grijalva’s middle name or perhaps his mother’s maiden name. In any event, in all likelihood this was Merejildo Grijalva.[39]

Grijalva’s activities in the early 1860s are difficult to reconstruct. It appears that he remained in Steck’s employ until 1861, when the need for an Apache agent suddenly disappeared. Two unfortunate and dramatic confrontations between Chiricahuas and Americans led to a bitter and unrelenting war between the two races. The first incident took place in early December 1860, when Grijalva’s former benefactor, James Tevis, led a group of hooligan miners and attacked Chihennes near old Fort Webster. In this unprovoked attack the prospectors killed four Indians and cpatured thirteen women and children, who were turned over to the military and later released. The indians had allegedly been pilfering stock, according to the whites. This wanton assault, in conjunction with the fallout from the notorious Bascom Affair at Appache Pass, were the sparks which ignited an Indian War. In effect, these hostilities created an opportunity for Grijalva and a demand for his services.[40]

The Chiricahuas would control southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico during 1861 and most of 1862. With the onset of the Civil War, troops from Arizona were withdrawn and its posts abandoned. In New Mexico, Union forces were more concerned with fighting Rebels than Apaches. Cochise and Mangas Coloradas seized this opening to completely dominate the frontier, attacking anyone in their path. Although most of their victims were small parties of travellers, there were some piched battles. Their new found audacity and supreme confidence manifested itself when they assualted the mining town of Pinos Altos in broad daylight on September 27, 1861. mining town of Pinos Altos in broad daylight on September 27, 1861. It was a hard fought engagement heavy casualties.[41]

Into this widespread instability some 2300 troops from California, known as the California Volunteers, came to Arizona and New Mexico in the summer of 1862. Led by Brigadier General James H. Carleton, their objective was to drive the rebels from New Mexico and to reestablish federal rule. Yet by the time these troops had arrived the Rebels had retreated to Texas. Now an occupation force, the Volunteer’s primary mission was to restore civil order and to subdue the Apaches. These men were willing to fight Indians if they could find them, which was no small challenge. To accomplish this, they enlisted the aid of civilians to serve as guides. The most effective of these scouts would be individuals who were former prisoners of the Apaches. In New Mexico and Arizona, men such as Juan Arroyo[42] and Merejildo Grijalva would provide indispensable services.

Cochise and Mangas Coloradas hadn’t allowed the Volunteers safe passage through Apacheria. At Apache Pass on July 15, 1862, they had ambushed an advance party of troops, and both sides incurred light casualties. After this fight Carleton ordered the establishment of a new post at Apache Pass, which would be named Fort Bowie, a place that Grijalva would become very familiar with over the next decade.[43]

In late July Carleton marched through Apache Pass en route to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The route was marked by skeletons, graves, and charred wagons — all stark testimonials to the audacity and brutality of the Indians. After reaching Santa Fe, Carleton received reports from the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, emphasizing the critical condition of the Territory because of Apache raids. Furthermore, the Indians had gone unpunished and this galled the stern officer. These frightening pictorials left Carleton with a vivid glimpse of Apache warfare. Thus he turned to the Indians his attention — every bit of it since he knew of no other way of resolving this desperate situation. In the fall of 1862 he directed his enormous energy and indefatigable zeal against the Apaches.

Carleton s most obvious target was Mangas Coloradas, a superb specimen of an Apache leader by any standards. It was against the great Chiricahua that he planned his offensive. On October 14, 1862, e wrote to Colonel Joseph R. West, (soon to be promoted to brigidier general) that it is “desirable to make a campaign against Mangas Coloradas.” He believed that winter would be the best time ‘to operate against these indians.” In conclusion, Carleton recommended that West “gather all the information you can on the haunts of Mangas’ band , its probable numbers, the best guides for the country... ,”[44]

It was at this time that Grijalva’s career as a scout began although he apparently had no direct role in the treacherous capture and execution of the eminent Chiricahua chief.

On November 2, 1862, Brigadier General West responded, writing from Mesilla to the AAG, Department of New Mexico:

The desire expressed by the general commanding to send an expedition against the Indians in the vicinity of Pinos Altos Mines can be attained, and I think with successful results, if troops can be spared from the northern portion of the department. Jack Swilling,[45] is at the mines and is available for service. I have in Government employ here a Mexican boy stolen from Sonora, who was seven years a captive of Mangus Colorado’s band. With such good guides ... a severe castigation could most likely be inflicted upon the Indians... ,[46]

The “Mexican boy” referred to by West was Merejildo Grijalva. A few months later both Swilling and West were involved in the perfidious capture of Mangas Coloradas. West reportedly told the sentries who were guarding Mangas that he didn’t want the chief alive the next day. As a result, in the early morning of January 19, 1863, the chief was shot and killed. According to West s duplicitous report, Mangas was killed attempting to escape. In reality, he was kille in cold blood by the sentries.[47]

According to Poston, Grijalva was with West’s detachment. If so, he played no direct role, as far as can be determined at this late date, in one of the most notorious of all Chiricahua — Anglo incidents. The Chiricahuas called it “the greatest of wrongs.”[48] Yet he may have been involved in the events after Manga’s death, given the success of the troops. Soon after the execution American soldiers launched a search and destroy scout against Manga’s people. One command, under Captain William McCleave, attacked Chihennes near Pinos Altos and killed eleven and wounded a wife of Mangas Colorado. Another, under Captain Edmond D. Shirland, surprised an Apache camp near the Mimbres and killed nine men. In early March Shirland set out on another patrol with some eighty men and three MeX1can scouts, probably including Grijalva. They were joined by a group of twenty-four civilians under well known mountain man Joseph Reddeford Walker. Nothing was accomplished, and the command returned to the newly established Fort West on March 22, 1863.[49] This was the beginning of Carleton’s offensive against the Indians.

In February he had sent four companies of cavalry to establish Fort West to protect the rich mining district of Pinos Altos. The site selected was located on the east side of the Gila River, north of present day Silver City. The post was “situated on a commanding hill on the site of an old Indian Pueblo.” Grijalva’s first assignment would be at this post. No permanent quarters were built; the men lived in Sibley or wall tents and in some cases had constructed wicker or basket houses.”[50]

There were three “citizen spies” on the post’s rolls at the end of May. They were not enumerated on the post returns until the June report filed at the end of that month. Grijalva was listed as Marijildo Bryalba; the other two were Juan Arroyas [Arroyo] and Felippe Gonzales.[51] In all likelihood the three civilians had been at the post from its inception. Grijalva’s recollectio ambiguous on this score as is the sparse documentation. Arroyo and Gonzales were paid seventy-five dollars per month, Grijalva was paid the lesser rate of thirty-five dollars per month, probably because of his youth and inexperience. In addition, he had not yet competence and fearlessness that he would exhibit in later years. At this time he was not a scout who could operate independently because of his fear of being recaptured by the Apaches. They would recognize him, he thought, and if so that would seal his fate to certain torture.

West expected that McCleave, among the best of the armies’ Indian fighters, would crack the whip at the Chihennes and prevent Ul from escaping into the country of the White Mountain bund of ern Apaches, located in east central Arizona. He ordered ththe officer to “make war on the Indians ... Indian women and children are to be taken captives when possible ... but against the men you are to make war, and war means killing.”[52]

The Chiricahuas would strike before McCleave. On March 22, 1863, thirty mounted Indians and a number on foot (“supposed to have been Chiricahua and Gila Apaches”) ran off sixty horses within three-quarters of a mile from the post. One sergeant and twelve men were guarding the stock when the Indians attacked. Sergeant Green “shot one Indian but he got off even after falling from his horse.” McCleave sent Lt. Albert H. French and eight men to cut the trail; he soon followed with eighty-one men and ten days rations vowing to “either retake the horses or Apache blood enough to pay for them.” Although not mentioned, Grijalva was probably present and, if so, it was he who identified the Indians as Chiricahuas and Gila Apaches.[53]

Juan Arroyo and Felippe Gonzales guided McCleave’s command as they followed the trail to Rio Bonita in eastern Arizona. Grijalva remained at Fort West. McCleave’s scout proved successful as he jumped an Apache camp and killed, he asserted, twenty-eight. Notwithstanding this victory, the two guides were sometimes confused because they lacked knowledge of that section of the country. On the return to the fort the command actually became lost and men and horses suffered greatly from lack of water and food. This would have been averted if Grijalva had accompanied the command.[54]

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1863, West and Carleton made plans for what they believed would be the crowning blow to Mangas’s band. In mid-March Carleton reminded West that “I do not look forward to any peace with them, except what we must command. They must have no voice in the matter. Entire subjugation or destruction of all the men are the alternative.”[55] The Apaches would not surrender, however. The Chihennes under Victorio and the Choko- nen under Grijalva’s former captor, Cochise (who also, it will be remembered, happened to be Mangas Coloradas’ son-in-law) organized a war party to avenge the perfidious murder of Mangas. Their boldness and brutality would surprise West, who had discounted the Chiricahuas as too fragmented to take the offensive. The Indians would soon dispel that notion, and Grijalva would see his share of action that summer.

In lune the allied Chiricahuas struck in traditional Apache style, showing no mercy to their enemies. First, along the Jornada del Muerto. opposite San Diego Crossing of the Rio Grande they murdered Lieutenant L.A. Bargie and another man. Three soldiers were wounded. Bargie fought and died heroically. His last orders were, “Sergeant, do your best for our men and save the Government property I am eoine.” The Indians mutilated Bargie’s body, carrying off his head as trophy. In addition “his breast [was] cut open and his heart was taken out” This barbaric treatment duplicated what West’s soldiers had done to the corpse of Mangas Coloradas. At the same time Apaches captured the mail near Fort Craig and killed the courier. On June 20, Apaches attacked another group of Americans six or seven miles west of Fort McRae, killing two men and two women, one the wife of Captain Albert H. Pfeiffer.[56]

West concluded that these acts were committed by “Mimbres River Indians.” Incensed, he ordered McCleave to put his command in the field. The diminutive general’s fury can be inferred from his terse but explicit instructions to McCleave:

This band of Mimbres River Indians must be exterminated to a man. At the earliest possible moment that the condition of your command will admit of it you will undertake this duty. Use every available man ... Scour every foot of ground and beat up all their huants.[57]

On June 27, 1863, McCleave left Fort West on a campaign against the Chihennes. Grijalva, Arroyo, and Gonzales acted as guides. On July 12, 1863, one detachment jumped a Chiricahua group near old Ft. Thorn, killing ten. Based on McCleave’s report, West concluded that he had struck those responsible for the recent depredations. West, respecting the judgment and initiative of McCleave, gave his subordinate a free hand to follow the Apaches wherever the trail might lead. Consequently, he set up a base camp on the Mimbres River. That summer McCleave’s command would be on the move against hostiles. Grijalva was with them, but he apparently played a less conspicuous role than Arroyo or Gonzales.[58]

In the meantime, the Chiricahuas resumed the offensive in July 1863, ambushing two separate parties of troops in Cook’s Canyon, killing a few men and making off with a great deal of loot. Naturally West was displeased; again troops were called in from everywhere, and Grijalva was again out scouting. The Indians eventually moved out of range and the troops were unable to accomplish much in New Mexico for the remainder of 1863.[59]

Grijalva’s tenure in New Mexico was coming to an end. On Christmas Day, 1863, Fort West was ordered abandoned, and the troops left on January 8, 1864. Most of the property and soldiers relocated to Camp Mimbres. Because the Arizona posts lacked experienced guides, Grijalva was ordered to report to Fort Bowie. His stint in New Mexico had not been particularly noteworthy. Yet it was educational as he had gained valuable experience working with Juan Arroyo. By this time he had reached his prime, standing about five feet nine inches tall and “admirably formed, uniting strength, activity and endurance.”[60]

He would begin to make his reputation as an extraordinary scout at his next assignment.

Chapter Three: With the Sagacity of a Bloodhound

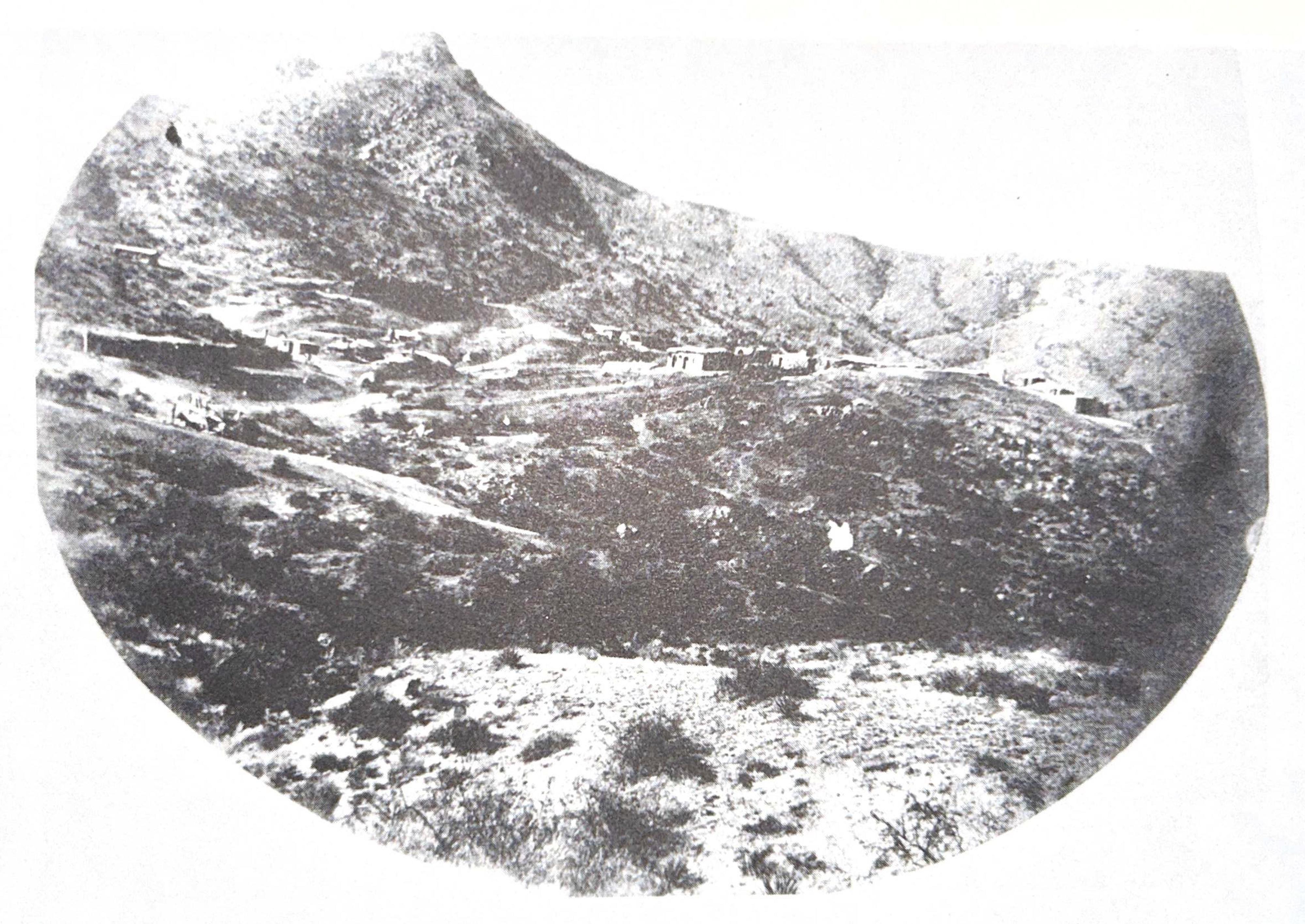

Grijalva arrived to take up his new duties at Fort Bowie in Apache Pass in January 1864. He found conditions there no better than those he had left at Fort West. Bowie had been established July 28, 1862, only thirteen days after the Battle of Apache Pass. Its main responsibility was to keep open lines of communication between New Mexico and Arizona and California. In addition, the commanding officer was to take aggressive action against Cochise’s band. Yet at the time of Grijalva’s arrival no permanent quarters had been built, and the men lived “on or under the ridges of land on the hill’s summit and slopes.” For the most part the soldiers’ only protection were tents. Three months before Grijalva’s arrival, Captain Thomas T. Tidball, the post commander, had described the post in these words:

The quarters, if it is not an abuse of language to call them such, have been constructed without system, regard to health, defense, or convenience. Those occupied by the men are mere hovels, mostly excavations in the side hill, damp, illy ventilated, and covered with the decomposed granite taken from the excavation, through which the rain passes very much as it would through a sieve. By the removal of a few tents, the place would present more the appearance of a California Digger rancheria than a mi i tary post.

Tidball was authorized to begin building a new post, but that fall (1864) he was transferred to a new assignment.[61]

Shelter was not the only problem at the fort. Its isolation and accompanying boredom, combined with the harsh conditions, made life at the post unappealing to most of the men and officers from California. Carleton, recognizing this, had ordered that the garrison be rotated as often as possible. Consequently, the post had six commanding officers during its first year of occupancy. This transience led to instability and inertia.[62] Not one successful patrol had been carried out against Cochise’s Chokonen even though they remained camped in their favorite retreats, thirty or forty miles south of the post Of course, the lack of an experienced scout would have made any such detail a waste of time and resources. Grijalva would change all that, but not overnight.

West had sent Grijalva to Bowie hoping that he possessed the necessary skills to lead the soldiers within striking distance of Cochises Chokonens. He would remain at the post for some two and a half years, becoming the epitome of what was required of a frontier scout. He set the standard for guides, for he was just as much an Apache as those Apache scouts employed by General George Crook two decades later. He knew every trail, every camping site, and every spring, water being the most precious commodity in the arid Southwest. Furthermore, because the Chiricahuas were primarily gatherers, hunters, and raiders, and not agriculturalists, he could anticipate with much certainty their migratory tendencies and probable ran- cheria sites. His presence would prove dangerous to Cochise, who probably rued the years of free education his people had given Grijalva. In turn, the young scout realized what was in store for him if recaptured by the Apaches. As a consequence, he was somewhat cautious in his early years of scouting, not exhibiting the daring which would later become his trademark.

Grijalva s first scout from Bowie occurred in February 1864 when it was reported that Cochise was “about that town,” probably based on signs detected by Grijalva. On February 23, 1864, Captain Tidball, with thirty-seven men, left on patrol and returned on March 1 after traveling 140 miles without seeing Apaches. Although Grijalva was not mentioned, he undoubtedly acted as guide.[63]

That spring Grijalva particiapted in General Carleton’s much publicized Apache campaign which, according to the martinet general, would be “a serious war; not a little march out and back again.” His objective was simple: “to hunt and destroy all but the women and children.” Carleton revealed his obsession with defeating the Apaches when he assured Captain Tidball that he would “do all that mortals can do to bring this Apache war to a speedy and final end.” He would whip them before Christmas, he confidently predicted.[64]

Carleton planned a pincer-like assault against the Apaches along the Gila. Troops were concentrated at Fort Bowie, where a campaign under Major Nelson Henry Davis got underway. Tidball’s command of some thirty-five men were part of the offensive, which struck Western Apaches north of the Gila. Grijalva guided Tidball’s detachment, while his former mentor Juan Arroyo, who had arrived from New Mexico, guided Davis’ command. All told, the troops attacked and destroyed four rancherias. Tidball and Grijalva participated in one combat in which some forty-nine Western Apaches were killed and sixteen captured.[65]

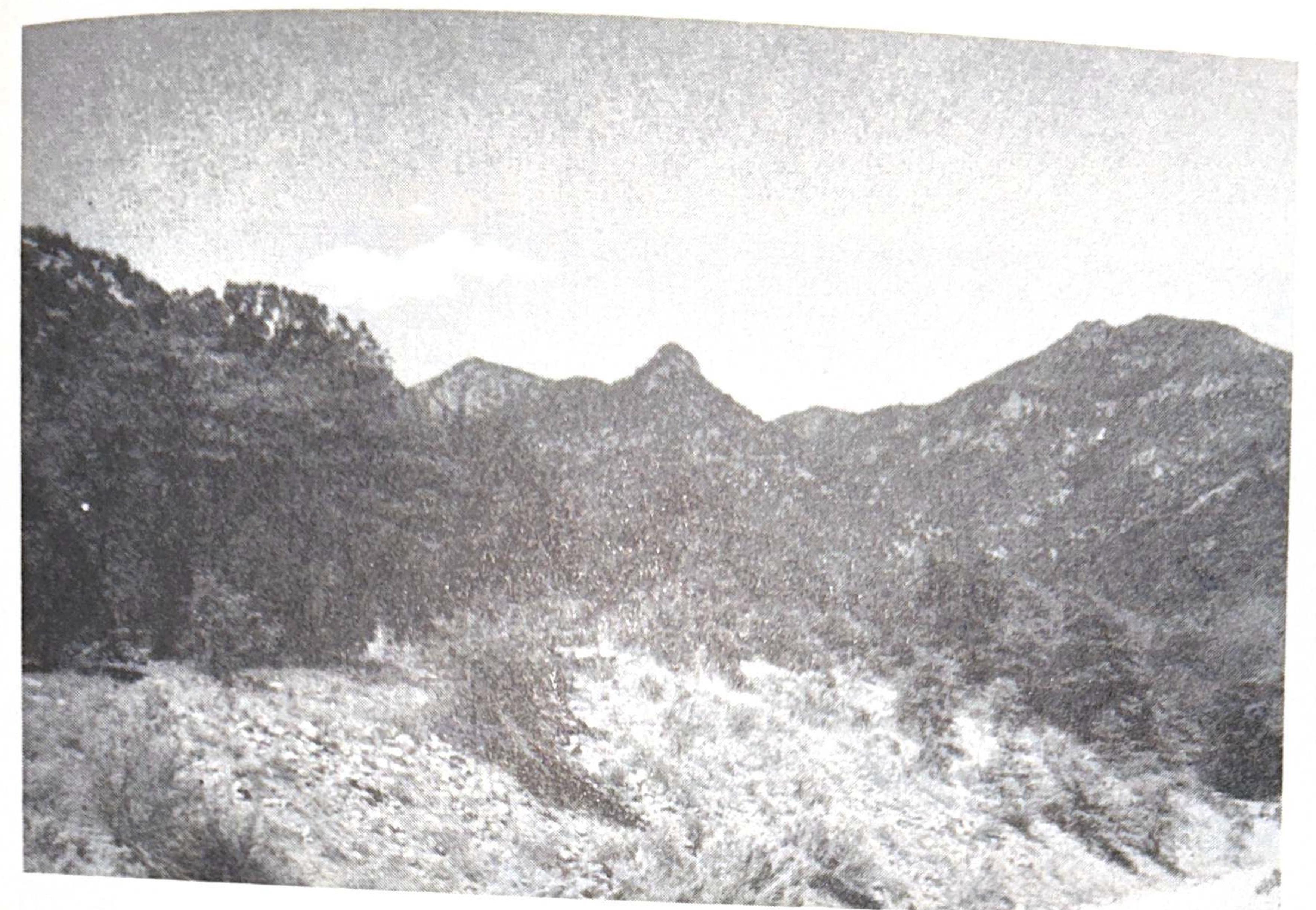

Tidball and Grijalva returned to Fort Bowie on June 21, 1864. After a short rest they sallied once again on one of the more interesting patrols launched from Bowie in the fort’s brief two years of existence. It was also the first patrol in which Grijalva could display his immense knowledge of the Chiricahua Mountains and of the Apaches themselves. In addition, it was probably the first time that American troops actually crossed from one side of the range to the other. This could only have been accomplished with Grijalva as scout.[66]

Tidball’s patrol left Fort Bowie on July 10, 1864, with fifty-eight infantry mounted on mules and twenty-two days rations. That day the command traveled fifteen miles on a southwesterly course and camped in the mouth of Bonita Canyon, near where the Faraway ranch was later built; the second night they halted at Pinery an yon; and the third day penetrated the heart of the mountain via a place that Grijalva called Tierra Blanca [White Land]. This is not identifiable on any map today but it can be locate w enit is u c stood that the scout was converting the place names rom hua and translating it into Spanish. Consequently, this was Turkey Creek Canyon which the Chiricahuas knew as IsetaoolU of white rocks all piled up.”

On July 14 the command had an arduous six hour march b‘ acking on the divide at the base of Fly’s Peak, some 9,000 f^’ altitude. No fresh signs of Indians had been seen. Despite this Captain Tidball seemed to be enjoying the patrol remarking that this “is the most interesting portion of Arizona that I have visited. The change from ragged, barren mountains and monotonous plains is refreshing.” Grijalva told Tidball that the Apaches avoided camping at these heights “on account of the great number of bears which abound there.”

The detachment left camp at 7 a.m. the next day, moving ata methodical pace to the east and striking Rio Ancho (Broad River), which the Apaches knew as Tu-n-tel-jin-li, meaning water broad going.” This was Cave Creek, which as Tidball stated, ran in the direction of the Cienega de Sauz (San Simon Creek), probably its main source of supply.” The soldiers camped here about two miles southwest of the present-day town of Portal, Arizona. Grijalva had not discovered any fresh signs but was taking the troops to favorite rancheria sites. His intuition paid dividends.

Early that afternoon, Indians were seen “going up a steep mountain about a mile from camp.” Immediately Tidball sent out a sergeant, twenty soldiers, and Grijalva in pursuit. After reaching the place where the Indians had been seen, the whites encountered one bold and defiant warrior standing on a perpendicular group of rocks about one hundred yards from the soldiers. “He said he was a warrior and a brave one and commenced shooting arrows,” but without effect. With his options fast dwindling and his supply of arrows depleted, the Indian began throwing rocks, one of which hit a corporal. At this point the soldiers opened fire, mortally wounding the defiant chief, whom Grijalva recognized as Plume, a hard-bitten old Chokonen leader. In turn, Plume acknowledged Grijalva and called for him. Grijalva was less than eager to undertake this risky arrangement and wouldn’t approach until he was sure that Plume “could not use his bow and arrows.” As luck would have it, the chief was near death when Grijalva reached him and refused to say a word.

Tidball respected the old chief, who Grijalva described as “an Indian guilty of numerous murders and robberies, sullen and tyrannical among his own people and merciless to al others.” Plume could have easily escaped but instead had fought a stubborn rear guard action “to cover the retreat of the women and children, or else considered it unworthy of a brave chief to run, and with savage stoicism determined to sacrifice himself.” Grijalva did find a camp of five “jacais” and a recently abandoned mescal pit. Tidball described the rancheria as situated on “a bold bluff standing prominently out into the valley, and commanding a view of every possible approach from the valley.”

The patrol continued the next morning taking a southerly course parallel to the eastern face of the mountains. After a four- mile march the elusive Apaches were again seen; they were “hallowing from the cliffs of the range. Tidball sent out Grijalva to parley, but neither party dared to come close. Finally four Apaches came within a mile and one advanced to have a talk. Neither Grijalva nor the warrior would approach one another, however, and “both were forced to speak at the top of their lungs.” The Indian disclosed that this band belonged to Cochise and to Mangas Coloradas. He agreed to make a treaty at Bowie if the troops would encamp. Tidball consented but as soon as the mules were unpacked the Indians “all fled up the mountain. Tidball at once broke camp and continued his march south.

Nothing of note occurred until the afternoon of July 21, when the soldiers went into camp a few miles east of Price Canyon and discovered that two mounted Indians were on their trail. They called for Grijalva, and he went out for another council. The Indians, apprehensive of Grijalva, wouldn’t agree to talk until he ‘brought his musket into camp.” Grijalva reciprocated this distrust, and requested that Tidball place men in ambush “to shoot this Indian” once he came in to parley. Fortunately Tidball refused to be a party to Grijalva’s undistinguished plan of treachery, which “greatly disgusted” the scout. Another conversation was held with the Chokonen man, whom Grijalva recognized as Ka-eet-sah, a prominent warrior. He lamented to Grijalva that Sonoran troops had surprised a Chokonen rancheria in the Chiricahua Mountains the previous February, killing his wife and children.[67] Ka-eet-sah further claimed that is band and that of old Plume’s were the only two groups living in t e Chiricahuas.

With this information Tidball decided to terminate his scout in the Chiricahuas and cross Sulphur Springs Valley to the Drag00n Mountains. Nothing of note took place the rest of the march, and Tidball’s command returned to Bowie on August 1, 1864.

In writing his report, Tidball paid special attention to the efforts of his twenty-four year old Mexican scout:

To insure success however, at least two good scouts are necessary Berriguildi [Merejildo] is thoroughly acquainted with these mountains, and perfectly familiar with the habits of these Indians; but he is constitutionally timid and knowing as he does the terrible fate awaiting him if ever captured by the Apaches, he will not venture out of sight of the soldiers — or, if compelled to go, his statements cannot be relied upon, as he allows his fears to overcome his judgement and his regard for truth.[68]

Tidball’s comments deserve analysis. On the one hand he praised Grijalva for his knowledge of the terrain and Apaches. On the other hand, his assessment of the scout’s character and almost cowardly actions are difficult to accept since no other complaint of this nature was ever made about Grijalva. One possible explanation might be that since this was one of the first times he scouted alone, he might have shown some trepidation in pursuing the same Indians who had held him hostage for some ten years.

The last five months of 1864 were uneventful for Grijalva. Captain Tidball, the most aggressive of Bowie’s commanders, was transferred to New Mexico in September, and eventually succeeded by Lieutenant Colonel Clarence E. Bennett. Bennett, like Tidball, was initially appalled about the post s quarters. Noting that conditions had not improved on any count, Bennett stated that the “quarters are worse now than then. We have just had a long, terrific mountain storm. These huts presented truly a most wretched appearance.” hey were beyond repair and new construction should begin as speedily as possible.”[69]

Bennett had other, more pressing concerns. Cochise had been active dunng the first few months of 1865. In March he organized a large war party from the Chiricahuas for a foray into Sonora. He aldsosent a few scouts to take a look at Fort Bowies herd. On M irchU, 1865, Indian signs were found at Apache Pass. Bennett sent Grijalva out with a small party to “carefully examine this canyon.” Grijalva believed that “this was a reconnoitering party to see the post and herds.” That evening Bennett, guided by Grijalva, took a patrol to the Dos Cabezas Mountains north of Apache Pass, but failed to find any fresh signs. Bennett vowed to keep the guide “on the alert each day to prevent the Indians from capturing the herd.”[70]

Two months later, on May 28, 1865, Grijalva was ordered to accompany the expressman, John Carroll, to Fort Goodwin to point out the most direct route between it and Fort Bowie. While there he must have learned that Cochise was camped south of the post, information probably obtained from the Western Apaches who were living near Goodwin. Shortly after this trip, he met Brigadier General John Sanford Mason, the new military commander of Arizona, who had arrived at Bowie as part of an inspection tour.[71]

Mason decided to take immediate action on this intelligence. Consequently, on June 26, 1865, Mason issued orders to Bennett to take every available man on a scout to the Sierra Bonita range (Mount Graham) and surprise Cochise. Grijalva would act as scout.[72]

Bennett departed that evening with forty-three men, three citizens, and two scouts, Grijalva and Lojinio, a “tame Apache.” They followed an old Indian trail north, skirting the western face of the Dos Cabezas Mountains. On June 29 they discovered a deserted ran- cheria, believed to have been Cochise’s, which from the signs, had contained between two and three hundred Apaches. Bennett continued on to Goodwin and rested a few days before embarking on his return trip to Bowie. En route Grijalva found two more ran- cherias, one was a Chiricahua camp, perhaps Cochise’s, and the other that of Francisco, a man with whom Grijalva was well acquainted. A close ally of Cochise, Francisco was an incorrigible, powerful Eastern White Mountain leader who shared his friend’s antipathy towards Americans. After the whites had looted his camp, Francisco appeared in the mountains and “abused everybody [declaring] he would never make peace with the whites.” The command recovered twenty seven head of cattle from Francisco’s village before returning to Bowie on July 6.[73]

The Chiricahuas were active during the summer of 1865 but not within the jurisdiction of Fort Bowie. Consequently, Grijalva enjoyed a quiet period at the post, which saw the revolving door continue with yet another officer placed in charge. Bennett left in July and on August 2, 1865, Major James Gorman, formerly stationed at Fort Goodwin, assumed command. Like most officers transferred to Bowie, it was apparently not an assignment that he relished, and he arrived with a less that spectacular reputation and a reported fondness for the bottle. All this aside, however, he did succeed in launching an important campaign against Cochise in the fall of 1865. Naturally, Grijalva played a crucial role.

On October 30, 1865, a large number of Chokonens were reported in the hills near the post; white peace flags and smoke signals were visible everywhere. The next day a Chokonen chief held a long range parley with Gorman; Grijalva served as interpreter. Gorman, who had been ordered to make war, not to talk peace, told the Indians that “he had no authority to make a treaty.” Despite this, during the next few days several Chokonen women entered the post and were fed and clothed. From them Grijalva learned that they were camped in the lower Chiricahua Mountains.[74]

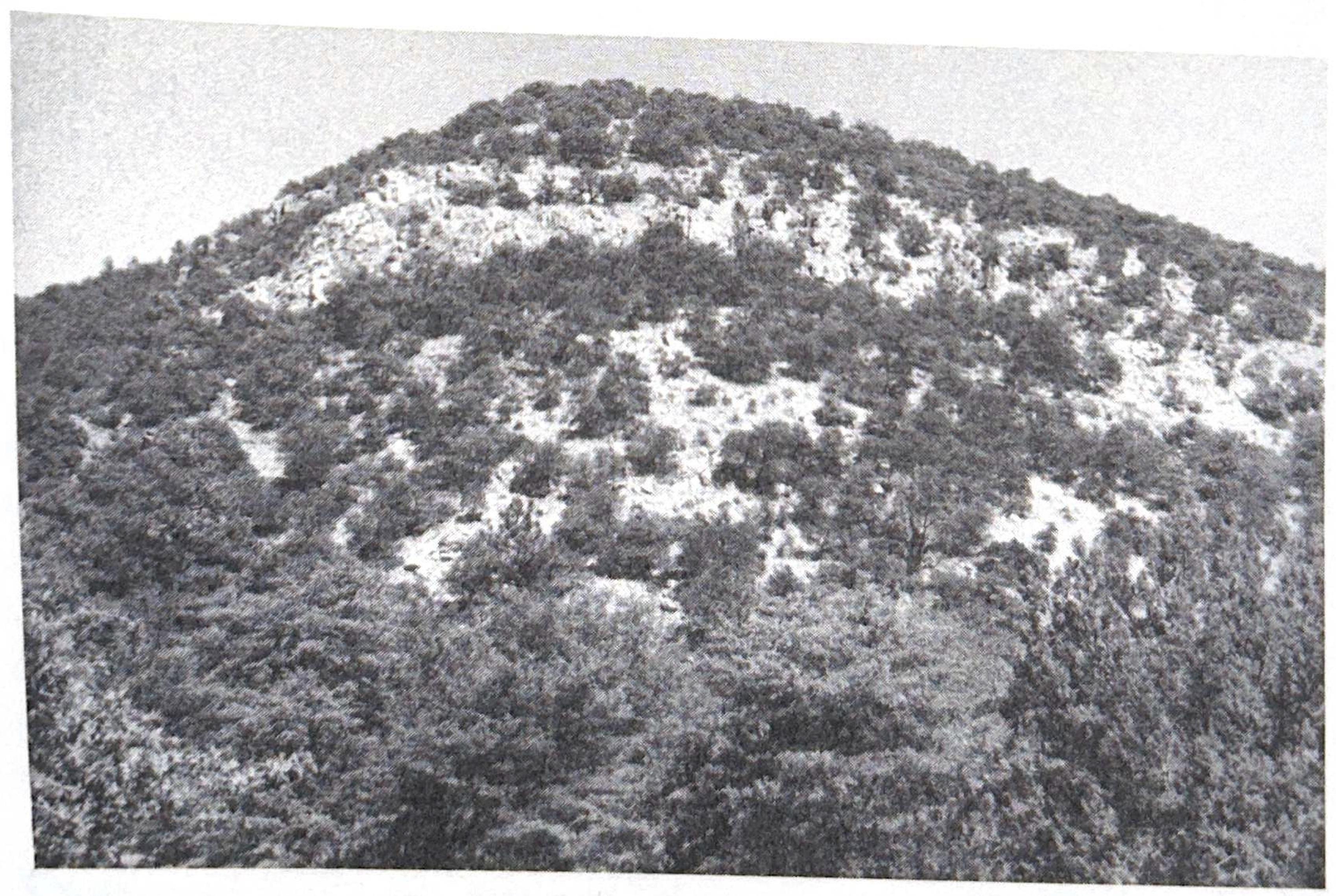

Gorman decided to act on this intelligence. On November 1 he took out a detachment of thirty-four men with Grijalva serving as guide. The patrol, marching by night and camping by day, a tactic which could be used only because of Grijalva’s unsurpassed knowledge of the country, followed the same route as Tidball’s scout, eventually entering the mountains from the west via Turkey Creek. During the day Grijalva found tracks of three Indians about four miles from camp. That evening they “saddled up and travelled until about 2 O’clock a.m. the Guide following the tracks of the three Indians, over a hard and rocky ground with a sagacity truly wonderful.”

At this time the command halted, and Gorman sent Grijalva forward “to reconnoitre.” He displayed none of the timidity which Tid- ball had observed fifteen months earlier. After an absence of one hour, Grijalva returned with the “glad tidings that he had found the rancheria about three miles distant.” Gorman immediately made preparations to attack it by the “peep of day.” Leaving eight men an Jus horses in a deep ravine, the officer took the balance of his command and came upon the rancheria just as “daylight came.” Cochise had taken the precaution of placing a sentinel near his camp, but Grijalva maneuvered the soldiers past him. As a result, the troops were within sight of the village by the time they were discovered and the alarm raised. The date was November 5, 1865.

At once Gorman gave the order to rush the camp and “a fierce and more closely contested quarter race has seldom been seen.” The panic-stricken Indians, astonished at discovering whites in their country, Red up the mountains “like deer, scattering in all directions.” The soldiers had hardly taken possession of the camp when Grijalva found another small rancheria about half mile away. Grijalva, Gorman, and part of the force raced to take control but the “Birds had flown leaving everything behind them.” As the Indians were running up the sides of the mountains the soldiers indulged in target practice, killing seven, or so Gorman reported. An immense quantity of material was confiscated, for this was an Apache camp well provisioned for the coming winter. From all the available evidence, the rancheria was located in the vicinity of Rucker Canyon.

Grijalva confirmed that this was a local group of Cochise’s Choko- nen. In addition, Gorman claimed this was the first time Cochise had been surprised by troops in his country. In fact this was the most successful campaign carried out from Bowie against Cochise until the late 1860s. The credit, he acknowledged, belonged to Grijalva. It was clear from his report that the young scout had shed the timidity which Tidball thought he had observed. He had developed into a first-rate guide; perhaps the only person able to locate and then injure Cochise in his country.[75]

Later that month Grijalva guided Lt. A. N. Norton’s command on a scout north of Bowie but returned without seeing any hostile sign.[76]

His next activity was in early January 1866. Mason had concluded that a major campaign against Cochise was warranted and necessary, and he made plans for simultaneous operations in the Dragoons and Chiricahua Mountains in order to deprive Cochise of using these areas as sanctuary. The campaign got underway from Fort Mason, a new post named for Arizona’s commander established the previous August 21, 1865, on the Santa Cruz River, thirteen miles south of Tubac. The operation left Mason on December 13, 1865, under Colonel Charles W. Lewis. Three separate detachments scouted the Huachuca and Dragoon Mountains without much success. By January 2, 1866, Lewis and part of his force arrived at Bowie and replenished supplies.

While at Bowie, Lewis decided to utilize Grijalva’s services. His guides were two well known scouts, Antonio and Marcial, both of whom were living at Santa Cruz, Sonora. Marcial had been a captive of the Pinal band of Western Apaches for some fourteen years. As he was familiar with their territory but not particularly knowledgeable about Chiricahua range, Lewis replaced Marcial with Grijalva.

He guided the command over the same route he had used two months before during the Gorman scout. Penetrating the range from Turkey Creek, he continued south to Rucker Canyon and then moved into the higher mountains. On January 8 he found a large rancheria, abandoned only two days before. Some sixty or seventy warriors were seen among the high ridges, but they were too wary to come any closer and disappeared into the mountains. The presence of the troops forced Cochise to withdraw into Sonora. Like a bloodhound, Grijalva followed them to Fronteras, some thirty miles below the border, before Lewis concluded to abandon the pursuit. In reality, the campaign was a dismal failure but Mason’s superior, in California, Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, thought it a victory, for Cochise had been driven from Arizona.[77]

His first stint at the isolated post at Apache Pass was coming to a close. In mid February Lt. Norton sallied out once more, probably accompanied by Grijalva, in search of Apaches. After more than two weeks in the field they returned without having seen an Indian.[78] That June Grijalva was in Tucson when he received the following orders:

By the direction of the Colonel Commanding the District of Arizona you will return to Fort Bowie with the express rider today and join an exploring expedition as guide to the Chiricahua Mountains. On your return from the expedition you will report in person to the commanding officer at the new post on the upper San Pedro.[79]

Why Grijalva and not someone else was transferred, was not made clear. His assignment at Bowie appeared, on the surface, logical by all accounts. Yet department headquarters had probably concluded that he could provide better service stationed at the new post south of Tucson, rather than Bowie. If so, the rationale behind this would have been that Cochise’s main area of raiding was the Santa Cruz and Sonoita Valleys, where most of southeastern Arizona’s new settlements and ranches were established. In contrast, none existed in the vicinity of Fort Bowie; hence, Cochise had no reason to raid there except for an occasional sortie against the post’s herd.

Cochise may have been indirectly involved in Grijalva’s transfer. On May 31, 1866, he led a large war party which ran off Camp Wallen’s herd. Troops from Fort Mason unsuccessfully followed the trail with Captain Isaac Rothermel Dunkelberger, the commanding officer, lamenting that because “I had no guide that knew anything of that part of the country, I was compelled to return.” Furthermore, Wallen’s new commanding officer, Captain William Harvey Brown, may have requested Grijalva’s services as he had been at Bowie just prior to receiving orders to move to Wallen.[80]

Chapter Four: Duty at Camp Wallen

The new post on the San Pedro was established at a deserted ranch on the north bank of the Babocomari Creek, about sixty-five miles southeast of Tucson. It was named Camp Wallen, in honor of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Davies Wallen, an officer who served in Arizona. Its commanding officer, Lieutenant John McDonald, gave as his first request upon his arrival on May 9, 1866, “to be furnished a guide as the want of a guide will cripple me in operating against the Indians. Wallen’s primary objective was to “prevent hostile incursions by the Sonora Apaches [Juh’s band of Nednhis] and especially by the band of Cochise.”[81]

The exact date of Grijalva’s arrival to Camp Wallen cannot be etermined, but a good guess can be made. Sergeant John Spring, who arrived on June 4, 1866, recalled that the scout came soon after him. Grijalva had no time to rest as he guided an expedition into the Chiricahuas in late June. Early the next month his services were again in demand. On July 8, 1866, from Fort Mason, Dunkelberger requested that “the guide Merejildo, who was stationed at Fort Bowie, may be ordered to report to me at this Post as he is thoroughly acquainted with the Southern and South Eastern portion of the Territory.” The officer was probably aware that Grijalva had been ordered from Bowie to Wallen, perhaps hoping he could obtain the services of the scout whose reputation was fast growing.[82]

Upon Grijalva’s arrival at Wallen he found most of the men living in either tents or newly constructed adobe buildings. At once he built his own home, made of adobe, with the help of a Mexican named Mendoza. Here the young scout formed a friendship with Sergeant John Spring, a sociable and erudite twenty-one-year-old Swiss native. Spring left behind important recollections and observations of the Mexican guide. From him, we obtain more of a personal view into the character and personality of Grijalva, the man and indispensable scout.

One of his first duties was to accompany Spring on a detail near the post which attempted to break up a domestic quarrel between husband and wife. Grijalva prudently refused to intervene, but the idealistic Spring, believing the abused wife would appreciate his efforts at restraining her husband, opted to do so. For his no e efforts, Spring received a whack on the head with a frying pan, courtesy of the woman he had befriended.[83]

Spring s next involvement with Grijalva came in conjunction wit a “young, lively, and sociable” officer by the name of Lieutenant Edward Johnston Harrington. As Spring and Harrington had much in common, including a tremendous zest for life, an “intimate friendship” soon developed. This flamboyant pair enamored with the daughter of Grijalva’s acquaintance (Mendoza), whom Spring described as “unquestionably — when washed — a very pretty girl, with a clear, olive skin and large, black eyes of unsurpassed beauty and fire — in short, a semi-tropic belle. The family was poor, but, as far as we knew, strictly honest, decent, virtuous.”

As Harrington played the violin, the pair decided to give the Mendoza family a concert. Their problem was that neither Spring nor Harrington knew enough Spanish to compose even one line. So they turned to Grijalva, who to their delight, “entered upon the spirit of the thing with great ardor and gusto. From his ... repertoire of Spanish love-songs we selected one which sounded certainly melodious enough and had furthermore the great merit of being easy and short, consisting only of two stanzas of four lines each.”

They practiced diligently for two hours on four consecutive days — Harrington on the fiddle and Spring on the vocals. They had no idea what the lyrics meant. The love song “sounded Spanish — that was all we wanted.” Grijalva earnestly assured them that they ‘would give the Mendoza people a surprise and create quite a sensation.” That Sunday Harrington and Spring appeared at Mendoza’s humble dwelling and were received “most hospitably.” The object of their attention, Trinidad, “looked lovely” and soon enlivened “the scene ^ith a son$ or two.”

Soon the two soldiers proceeded into their ballad, Harrington “manipulating his bow in the most graceful manner” while Spring “fell into the tune.” At once Spring sensed something was wrong. Reaching the middle of the second line, Spring became alarmed when Trinidad pulled “her shawl violently over her face.” Next the grandmother approached the fireplace, “with the evident intention of seizing a firebrand.” He finally became concerned when Mendoza reached out for an ax. With a cry of “Murder,” Spring pulled Harrington from his seat and the two fled out the door “with sundry missiles being fired after us.” After a mad dash of fifty yards the two men found refuge behind a large boulder. “Here we found the rascal Grijalva, rolling over and over in uncontrollable laughter. He had watched the whole performance through the open doorway ... and saw the ‘grand finale’ of his good joke.”

Spring and Harrington felt like “murdering him on the spot, and I know we kicked him unmercifully.” To save his skin, Grijalva wisely agreed to explain the situation and “exonerate” the two soldiers “from all blame in the matter.”[84]

Life at Wallen wasn’t all frivolity, however. In late July or early August Captain Dunkelberger left Fort Mason on a patrol against Apaches who had stolen stock near Calabasas. Arriving at Wallen in early August, he picked up twenty cavalry and, in all likelihood, Grijalva. On August 8, 1866, they struck a trail of stolen stock near the South Pass of the Dragoons and followed it for five days to a Western Apache rancheria in the Graham Mountains. Here a parley was held with the Apaches presenting Dunkelberger with a pass issued at Fort Goodwin granting them permission to temporarily remain in the Graham Mountains. The warriors had returned to camp with their loot thus implicating the innocent with the guilty. One American claimed that he saw his stolen stock in the Apache camp but that Dunkelberger refused to take any action once the Apaches showed him their certificate. After complaining to the officers at Goodwin, Dunkelberger was authorized to attack any Apaches who had stolen stock in their possession.[85]

Other evidence of Grijalva’s presence comes from Anna Price Western Apache who as a young girl of about fifteen may have been present. Years later she told ethnologist Grenville Goodwin a stor similar to this incident, recalling that it occurred at Mount Graham, ind specifically mentioning that Grijalva was present.[86]

Grijalva returned to Wallen after this patrol. He would have a relatively quiet period as Cochise spent the remainder of 1866 in northern Mexico In December the guide would be in the saddle once more after a small Chokonen raiding party killed two men and wounded another about sixteen miles southwest of Wallen, near the Cando Hills They also carried off three oxen, one horse, and one burro, which proved to be their downfall as Grijalva was able to follow the raiders by their tracks, which led northeast throug e Huachucas and then east towards the San Pedro On December 12, 1866, Lieutenant William Henry Winters (a cavalryman with reputation} with thirty-five men, one citizen, and Grijalva, rushed to the scene of the attack.

Grijalva worked the trail east to the San Pedro where the patrol bivouacked the first night out. They broke camp at four the next morning, crossing the river and following the trail to a range w ic Winters called “Spiral Mountains,” known today as the Mule Moun tly abandoned mescal pit, a deserted rancheria, and a fresh trail which Grijalva followed to Mule Pass, where they encamped the night of December 13. The next morning the dogged patrol continued on the trail of the Indians, who had divided into two groups: one continued northeast into the heart of the Chiricahuas; the other headed east into the lower part of that range.

Winters decided to follow the first trail of three warriors “they being the greater number of the party.” A heavy rain the night before had obliterated the trail. At this crucial stage Grijalva displayed the skills which distinguished him from most Indian scouts. “As he knew the lay of the land and the probable direction the few Indians we were pursuing would take, he proposed to guide us by intuition.” He stuck for a canyon “knowing it to be leading to a high plateu hidden from the valley side by precipitous rocks, where Cochise’s bands had in former years frequently rendezvoused after a marauding expedition.” Spring described a setting that Hollywood would have loved:

[Grijalva] was riding about fifty yards ahead of the column, and had just ascended a small knoll on foot, when all at once he stopped, stepped back, and held up his hand as a sign for us to stop. Then he descended somewhat from from his high position and made signs to Lieutenant Winters to join him. They both crawled together to the top of the little hill, where they lay down flat and looked towards the mountains, using Winters’ field glass. They saw a feeble column of smoke ascending from a grassy plateau in front of the large canyon ... Grijalva said it would be useless to approach them from where we were, as they would be sure to see us ... He proposed to lead us into another parallel canyon in which we could ascend to high ground unseen [and] cut off the Indians’ retreat.

After moving into position, Grijalva saw that there were three Indians “sitting around a small fire in the open.” Winters and Grijalva decided that a “sudden rush” would enable the men to intercept the Chiricahuas before they could make their way to higher ground. Thus the charge was sounded with Winters, Spring, Grijalva, and a citizen named McFarland in the lead. Within two hundred yards of the Indians, twenty troopers stopped and fired, wounding seriously one Indian. The other two warriors were soon cut off and “dispatched pretty well up towards the mountains.” Meanwhile, the wounded man had crawled into an arroyo and “began to shoot arrows with great swiftness,” slightly wounding one man and two horses.

At this juncture Grijalva sized up the situation, deciding upon a daredevil move which he may not have considered a few years before. Making a “sign to the advancing column to withhold their fire”, he slipped into the ravine in the rear of the Indian. “Like a monkey he swiftly crawled down over the edge of the fissure, held his revolver against the head of the Apache, and dispatched him.” The fight over, Grijalva quietly slipped away and scalped the three Indians in order to claim a reward of one hundred dollars per scalp promised him by Conrad Aguirre, the hay contractor at Wallen.[87]

Winters had no illusions as to the key of the campaign’s success. “Much of the success in campaigning against Indians depends upon the guide. The one accompanying this expedition proved to be of great service, having been a prisoner among the Indians, he is well acquainted with their habits and familiar with most of the mountainous country east of the San Pedro River.”[88]

John Spring was just as effusive, if not more so, in his praise for Grijalva. He wrote:

Grijalva was an excellent guide, knew all that country perfectly, even to the most hidden watering places ... and was an expert trailer of tracks; he also knew the wiles and and stratagems of the Apaches, and would never have allowed his party to enter into a cul-de-sac or canyon where the soldiers might have been annihilated ... or where their exit might have been cut off ... His eyesight was almost marvelous in that respect....[89]

Early in 1867 the troops from Wallen went out on another patrol, this one against Western Apaches in the vicinity of Arivaipa Canyon. Grijalva tried to dissuade Lieutenant Harrington from taking men out after a few prowling Indians as “not worth a scouting expedition.” Instead, the impetuous officer persuaded Captain Brown (who was probably happy to get Harrington out of his hair) to allow him to take twenty men on the “coveted expedition.” Spring thought Harrington wanted to leave just to escape the ennui at Camp Wallen.

Grijalva had no choice but to go, though reluctantly. They left on a Monday morning and returned the following Saturday empty handed, having accomplished nothing except to subject most of the command to a case of temporary blindness from the snow. This patrol would forever be known as the “snow scout.”[90]

A few months later Cochise was again raiding in southern Arizona, and Grijalva was once more called to duty. On March 1, 1867, Cochise led a war party which assaulted the Patagonia mine’s, killing one man and wounding two others in a brisk fight. Soon after messengers galloped in to Santa Cruz, which, in turn, sent a dis- nie(ch to Captain Brown at Wallen. Brown immediately mounted “all flie men I had horses for,” some fifty-one, and left the post before March 2. It was a waste of time and resources, however. Brown’s indifferent and ineffective efforts earned him the disdain of General McDowell at Department Headquarters in San Francisco. Spring was in the pursuit, and he recalled that Grijalva served as guide, although he confused some of the details of this scout.[91]

In fact Brown’s endeavor was symptomatic of his efforts when forced to lead men into the field. His courage was never questioned; after all, he had earned two brevets for bravery in the Civil War. Yet his misdirected efforts and poor judgment of what was expected of troops in the heart of Apache country seemed to defy explanation. As Spring observed, Captain W. Harvey Brown

possessed very few soldierly qualification, and a very indifferent school education; he knew next to nothing of of the army regulations; but as the administrator of a recently established colony, he would have been a great success, being a practical farmer, who knew well how to obtain as much work out of the men as their physical development would permit.