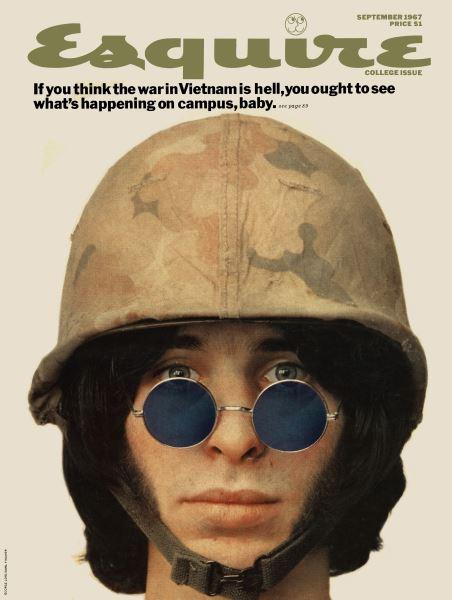

Esquire – College Issue – September 1967

An Open Letter to Flunk Outs & Patriots

The Student as Potential Assassin

Zen Basketball, etc. at San Francisco State

Painting the Ocean Red, Etc. At Colombia University

Confessions of a Campus Pot Dealer

Mapping the Varieties of Innocence From Antioch to Bob Jones

An Open Letter to Flunk Outs & Patriots

Hey, G.I.! How do you like it over there in Vietnam, tiptoeing between the punji spikes, woofing up all those good C-rations. nearly getting zapped by your own artillery? Last year the campus, this year the camp—and you've only yourself to blame. Wish you hadn't flunked the 2-S test, don’t you? Sorry about that, soldier. Too late now. But we've got news for you: you're better off where you are.

During your junior-year abroad, baby, all hell has broken loose back home. That clean-cut. sociable student president: gone. New prexy wears a beard and probably got elected on an anti-fraternity platform. The football captain is finished as the local hero, replaced in the hearts of your old classmates by the campus hippie who sells marijuana. Anarchy reigns; restrictions, requirements, rules are all going up in banana smoke. Equality for ail; even the valedictorian has disappeared along with the abolition of class ranks (actually a draft-dodging plot).

The pot party has replaced the beer blast; and the top rocks sing more about being high than of being in love. Love, incidentally, has been appropriated by a new bunch of Love Cultists who wear daffodils in their hair while they protest against the war you have to fight. Forget J.R.R. Tolkien: Frodo’s dead. Stranger in a Strange Land is grokking it to the top of the campus best-seller list, followed by its psychedelic buddy, the I Ching. Marvel Comics? Passe: this year the tops in pulp are the Underground newspapers which carry the latest word on flipping out. And flipping out is exactly where it’s at. Students at Harvard have taken to climbing over the roofs of the tallest buildings in the Yard; at the University of Oklahoma they are blowing bubbles; at Columbia they are flying kites from the top of the building in which the Pulitzer Prize Committee has convened. The Civil Rights movement is dead, replaced by the narcissistic Student Rights hassle—baby, they think they've got troubles.

All in all, fella, you got out just in time. But if you really want to serve your country you'll come back. Back to the American campus, armed to the teeth.

This section drawn by Mouse Studios

Defenders of the Faith

While you’re off fighting in Vietnam, you may be wondering who's back home minding the university. Sharp eyes, keen minds and sturdy patriots, that’s who. J. Edgar Hoover, for one: his F.B.I. agents regularly dip into student files (at Berkeley, Michigan and elsewhere) looking for tinges of pink, and pay student informers from $100 to $450 a month for information. They are aided by members of "Red Squads" (Intelligence Divisions) of local police forces who circulate during student demonstrations taking photographs of leaders and other faces in the crowds. California’s Governor Ronald Reagan, like other hard-core realists, maintains a cautious surveillance of intellectuals. He once criticized a Midwest college for "subsidizing intellectual curiosity.". It was also Reagan who proposed tuition for the University of California, explaining that it would “get rid of undesirables might think twice how much they want to pay to carry a picket sign.” The marijuana watch falls to undercover agents and university presidents like Cornell’s James A. Perkins, who turns over to the law anybody who's been caught with marijuana on campus. Congressman L. Mendel Rivers sees to the draft objectors, once proclaiming angrily, “College deferments may be a thing of the past. This is fair warning to every college student in America." And Rivers (Chairman House Armed Services Committee) has power.

The adults on the opposite page would be helpless without the aid of second-story men. And there is no dearth. R.O.T.C. men at the University of Washington have been trained by the U.S. Army to spy on fellow students, particularly members of left-wing organizations. Charles Ode- gaard, the President of the University, protested that the future Army officers were told not to take notes at a training session, during which they were shown a map of the West Coast with various left-wing headquarters marked. Odegaard also charged that R.O.T.C. men were to collect files on radical students, being warned that “If it walks like a duck, talks like a duck and lays eggs like a duck, then it’s a duck.” At Brigham Young University, anti-duck President Ernest Wilkinson asked eleven like-minded students to give him information on leftish faculty members, according to student Ronald Hankin, a former Bircher. On the pot front, non-student Linda Hobbie was asked to pose as a student at Fairleigh Dickinson University and entrap an undergraduate. She failed. At the Air Force Academy, three unnamed Air Force cadets blew the whistle (same one heard two years ago) and grounded thirty-two cheaters and eight others who knew but kept silent. And, finally, it was Michael Wood of the National Student Association who singlehandedly broke the cover on the story of C.I.A. subsidies of student organizations.

The Student as Potential Assassin

Nobody wants another Dallas, least of all the Secret Service. So when the Feds got wind that somebody had written on the outside of an envelope, "Johnson's war in Vietnam makes America puke," they swung into action. The handiwork was traced to Chuck Papke (above), a Zoology student at the David campus of the University of California. Soon Papke began to notice strange things: a helicopter circling over his apartment, a peculiar noise on his telephone line, an Oakland collection agency filing suit and freezing all the money in his bank account. Two Secret Service agents, Larry Sheafe and Roger Grunwald, arrived at the door one evening and told him he was being investigated, because the statement he wrote on the envelope had been interpreted as a threat on President Johnson's life. "If enough people puked on the President," Agent Sheafe claimed, "it would kill him."

The New Student President

David Harris of Stanford. He preached peache, oppposed the draft, tangled with fraternities, fought for educational reform, and then quit. His phone is tapped

by Gina Berriault

On the night of Octobor 20, 1966, twenty masked Delta Tau Delta men surrounded their student body president on the street of the Stanford campus, escorted him to an empty lot and, with electric clippers plugged into an outlet inside a dormitory, shaved off the abundant hair of his head. "They expected me to fight back," Harris recalled when I spoke to him about the incident. "I figured I had a captive audiance so I had a fifteen-minute conversation with this guy with a wolf mask who was holding my right leg--talking about education. After they shaved my head I said, 'Look, I've cooperated with you so far so we'll make a deal--you spare my beard.' And they did, after a big debate. I had to go to Michigan the next week and it was freezing cold."

Fraternity men find themselves confused by changing times. If those masked twenty were laboring under the biblical superstition that when the locks are shorn the strength ebbs they must have been surprised to learn that the strength increased. Or if the assault was a diversionary tactic, an attempt to make the issue the length of their adversary's hair because the real issue was even more intolerable—changing times—one, at least, among them, traced and questioned by a reporter from The Stanford Daily, admitted some decree of self-probing: "Harris really showed the Delts a lot of class. He made us feel sorry we did it.” It was his way of conceding that the men. bearded or unbearded, elected these days to the presidency of the student body in more universities than a few may be men of courage and conscience.

Students in these changing times are challenging the arbiters of the academy and of the hierarchical regions above and beyond. Within the past year or so several dignitaries have been met on the campuses by large and vociferous demonstrations. At Stanford, Vice- President Hubert Humphrey, emerging from the auditorium into his protective wedge of police and Secret Service men, ran for his car to escape some thousand angry students; Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara was forced from his car—a police wagon—and onto the hood of another car by eight hundred Harvard students who wanted to ask him a few questions before he left the campus; while students at Berkeley, some silently, some not, greeted U.N. Ambassador Arthur Goldberg with picket signs and a walkout by five hundred persons when that gentleman came by to pick up an honorary degree. A solid wall of one hundred fifty students blockaded the Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin in his office until he wrote the check that bailed out eighteen students arrested earlier for demonstrating against the campus-recruitment campaign of the Dow Chemical Company, manufacturers of napalm. At the University of Michigan, the Student Council lifted itself right out of the administrative Office of Student Affairs after administrators, during summer vacation when most students were away, handed over to the House Un-American Activities Committee the membership lists of student organizations opposed to the war in Vietnam. And so it follows that the men elected to student offices now. at universities around the country, are not keepers of those sacred flames of ritual and protocol and administrative decree.

Columbia’s David Langsam, Cornell’s David Brandt. Berkeley’s Dan McIntosh, Amherst’s Steve Cohen, San Francisco State's Jim Nixon. University of Minnesota’s Howie Kaibel, University of North Carolina’s Robert Powell. University of Houston’s Richard Gaghagen, University of Michigan’s Ed Robinson range from the “thoughtful middle,” as distinguished from the old unthinking middle, to the Far Left, and their force has been felt in everything from the structuring of the new experimental colleges within the universities to the refusal by several university administrations to comply with the ranking mechanism of Selective Service. And among these leaders, David Harris—the young man tackled by the twenty old guards—is the one most often cited by student editors and other presidents. “He gathers disciples around him wherever he goes,” said one disciple, and since he has spoken at so many campuses across the country he has gathered quite a number.

After meeting Harris for the first time at the 1966 National Student Association Congress at the University of Illinois, Neil Reichline, editor of the U.C.L.A. Daily Bruin, kept his staff up night after night to discuss Harris’ ideas on education, and through the pages of the Bruin brought about a great surge of interest in reform. “I was confronted by him and he blew my mind,” Reichline recalls. “Dave’s views on educational reform, on the Vietnam war, on the draft, are not based on political expediency. They follow naturally from his life-style, his mentality. His concern for his ‘soul,’ for his values, and for himself as a valuable person are manifested in his concern for the communities that he exists in, whether they are his school, city, or nation. He confronts you with this mentality, this concern for community, and you just can’t pass over it without some self-examination, some thought on your role as a human being and how you’re going to relate to other human beings. You can’t meet Dave Harris and not change your life in some way." Ed Robinson, the president who cut the cord between the student government and the administration at the University of Michigan, describes him this way: “Not only is Harris intelligent, he takes the next step and applies that intelligence to thinking about his surroundings, and then he takes another step and draws some conclusions, and then he takes the farthest step and acts on the basis of those conclusions. In this step-by-step progress we fall down somewhere, most of us.” The students are not alone: David Harris was one of several persons invited to participate in a meeting on students and the draft, called by Kingman Brewster, President of Yale. And in the editorial offices of The Stanford Daily, a file card, on the wall for months after David’s resignation, read: “I don’t know what Dave’s reasons are for resigning and maybe that’s beside the point. His A.S.S.U. administration has taken its toll on him and, I think in the long run beneficially, on official Stanford. But he’s been there long enough for all of us to see his real stature, his authentic qualities of greatness. How often do you see a man who. in being himself, can help you be and find yourself; in whom you’re able to detect no deviousness at all; whose compassion is no less compassionate for being unsentimental; who cares like hell about the world he lives in and can somehow go on loving and believing in the people who inhabit it, even while he protests the ways we go on lousing it up? For all his sharp, unremitting criticism—in part, of course, because of it—all of us, and all of Stanford, and the whole college and university scene in America are better for having him where he’s been.” The card was signed B. Davie Napier, Dean of the Chapel and Professor of Religion.

On the front door of the pale-green shingle house in the Negro neighborhood of East Palo Alto hung a penciled sign reading: Go Around to the Back Door. (His study room is in the back of the house, I learned a few minutes later, and if any other tenant of the house had been playing a record loudly, my knock would have gone unheard.) He opened the front door anyway, because two neighbor children, roaming in and out, saw me from an upstairs window as I made my way through the high grass; I heard them calling to him. He is a tall and strongbodied young man with thick, blond hair, sideburns—the beard is gone, he shaved it off one day for whatever significant or insignificant reason— pale blue eyes, rimless glasses, and a substantial moustache that makes him appear a few years older than his twenty-one. He had interrupted his part-time job at Kepler’s bookstore, owned by a prominent pacifist, to meet me. On the bright yellow wall of the living room hung a large photo of Charlie Chaplin with cane and derby, and a restaurant stove took up a good part of the floor space, a relic of the time Harris and the other tenants of the house were implementing plans— failed ones—to open a small cafe in Palo Alto. The window of his study looked out on a huge, fallen tree, an old blue bus with flowered curtains, serving as bedroom for one of the students of that communal house, and more high grass. The two neighbor boys, grammar-school age and loud talkers, gazed in from the hallway until they were asked to close the door. Out in another room a Bob Dylan record began and someone shouted from the kitchen, “The water's boiling!” An old suede jacket, mended carefully in a dozen places, hung from the closet door, boots were strewn on the floor, and a mother cat and four kittens lay atop a soft pile of clothes in a corner of the open closet.

The young man in the sagging, upholstered chair under the small photograph of Gandhi was scheduled to address in four days a massive peace mobilization in San Francisco. A senior, one of five students majoring in Social Thought among thirty in the Honors Program, an independent study program for self-motivated students, he was also teaching a class at the Free University of Palo Alto called “A Life of Peace and Liberation in the U.S.” Ashes fell from his cigarette into the crevices of the chair—his fingers are nicotine stained down to the middle knuckles—and as we talked books slid from the chair's wide curved arms. On the windowsill and on the shelf were Nietzsche. Kierkegaard, A.J. Muste, the Upanishad. I asked him about his use of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese Book of Changes.

“We never just open it and read it like a book.” he said. “We treat it like a friend around here. We treat it like a living thing.” Would he turn to it before his speech? To oblige me he turned to it then, first tossing three Chinese coins onto the rug six times. The result of this encounter with chance led him to the hexagram that in turn directed him to a page of the text:

"The weight of the great is excessive. The load is too heavy for the strength of the supports. ... It is an exceptional time and situation; Therefore extraordinary measures are demanded. It is necessary to find a way of transition as quickly as possible, and to take action. This promises success. For although the strong element is in excess, it is in the middle, that is, at the center of gravity, so that a revolution is not to be feared. Nothing is to be achieved by forcible measures. The problem must be solved by gentle penetration to- the meaning of the situation. . . . Then the changeover to other conditions will be successful. It demands real superiority: therefore the time when the great preponderates is a momentous time."

“It’s like taking a sighting off the top of a wave,” he explained. “It gives you a sense of the forces of life around you and finds your relationship to those forces for that moment."

His heavy build. Levis and sideburns suggest a farm laborer in the town of Fresno. California, where he grew up. the son of an attorney, and worked in the packing sheds; or they suggest a figure in an old labor photograph of the West, posing by dray horses and by timber. "He used to wear a big buckle on his belt.” one of his friends was later to tell me. “and when he spoke he was always shifting it up because his Levis were over-washed and loose. They were washed so much they were faded out to grey.” He probably resembles his grandfathers and probably hopes that he does. One was a wood craftsman in Fresno—“1 go over to his workshop—he’s dead now but his workshop is still there—and pick up scraps of what he'd been doing. 1 have a goblet he made on a lathe, the walls of the wood are thin as glass— all out of one piece.” The other grandfather worked in the open-pit copper mines in Utah. He talks with a fast mixture of beat jargon, academic terms, and words in common usage, and there is an accent that’s Southwest. the rural parts.

Up to a few years ago a university for the offspring of California aristocracy, Stanford—its arcaded yellow stone buildings on an almost unbelievable number of acres of thick grass, oaks, and date palms—now has endowment funds sufficient to grant scholarships to the sons and daughters of the less affluent, and Harris is one of these recipients. When he came to Stanford in 1963 he was, according to his own description, an all-American frosh type, a state finaljst in competitive speech from Fresno High who made innocuous speeches of no content, and a three-year veteran on the football team. Mississippi hit in that year, and the freshman dormitory at Stanford became a communication center for the South. In the Fall of 1964. in his sophomore year, he went South with a carload of Stanford students. With four others he entered Quitman County, Northwest Mississippi, wilderness territory. Their lives were constantly threatened and one of that group was kidnapped and beaten. "Essentially, when I was in Mississippi it wasn’t as big a thing as when I got back, because when I got back I really started thinking about what I’d done there. Mississippi blew my mind. From there I got involved in the whole antiwar activity, from there it was a natural educational progression. The South wasn’t just a boil on the face of America. The hate and brutality there were indigenous to the way America lives.”

At evening programs on the campus he spoke about Mississippi, he spoke against the draft, against the war in Vietnam, and he criticized the educational system at Stanford. “It’s all one thing. Once someone gets involved in Peace there’s no turning back from it. it’s a style of life, not something considered politics removed from one. It makes dealing with others a very direct expression of one’s being.” In his junior year he was approached by a group of students to run for president of the student body. He agreed to run in order to force the other candidates to face the issues, but he preferred to lose. He won. in the largest balloting in Stanford’s history. "The platform was a long list of changes based on the attitude that Stanford is not educating and has no understanding of what education is. Students have no right of control over their own lives. It's a system calculated on the impotence of the students in that it makes everything the student does something outside himself. What that does is teach people to be powerless. We started from the initial statement that education is something that happens in your mind, the mind learning itself, learning how to use itself. It’s a very inner process and the function that teachers traditionally serve in most of the cultures of the world—where they haven’t gotten to modern industrial teaching which is essentially a training mechanism—is one of spiritual guidance. Not only should a teacher know things but ho should have an understanding, a wisdom about things, beyond simply knowing them. So that a teacher provides himself as a mirror to the other person’s mind and gives that person a glimpse into his own mind SO he can then start educating himself. That’s what education is and it isn't this whole social system at Stanford, the superficialities. They rigidify the students here into cogs for the great American wheel. Most people who teach at colleges are doing it for very simple security reasons and they don’t like people to rock the boat even though they make a big thing ibout intellectual inquiry and all that. A professor will allow you to put down the administration but will get offended f you say the faculty is irrelevant, which they are. by and large, except for maybe ten people, and they're relevant as people because they’ve developed a •nyle of living that really has relevance to other lives. Then we talked about who runs the universities, that they shouldn’t belong to the trustees because they should belong to the people who are really involved in the spiritual process of learning, they should belong to the students and anyone who wants to enter into it.” One of the other planks of the platform was the abolition of fraternities. "It’s all one thing." Nothing is separable from the rest.

After his election, Harris met for the first time with J.E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford. He went into the latter’s office with beard, work shirt, I a? vis, and moccasins. "He has a smooth way of dealing with people.” Harris told me. “He never made it clear to me that he might have been dismayed by me."

As president of the student body, Harris led a Stanford delegation to the National Student Association Congress and proposed to the liberal caucus— roughly about one half of the five hundred people there—a resolution calling for immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam. Debate in the caucus lasted until four-thirty in the morning. The resolution failed; the one that passed the caucus and eventually the Congress called for a ceasefire and negotiations, and drew this comment from Harris: “If you come out with this resolution, you will be raying that you feel strongly about the war but you don't want to say it.” Another resolution proposed by Harris, calling for abolition of the draft and formation of a draft-resistance movement. was also softened by the liberal caucus and passed by the Congress. After some "soul sessions” a radical caucus was formed and walked out on the liberal caucus. For liberals Harris has no favorable word. “They recite all the American virtues—‘We are :oyal American citizens who believe in America. La de da de da de da. . . They fall on their knees to President Johnson and say, ‘Please reconsider, there may be something wrong with the war.’ That way of doing things— bribing people, getting to their egos, all kinds of insidious things. What they’re doing is further entrenching the whole attitude that brought this war about.” On the N.S.A., in particular: “The only time members ever get together is for that Congress where they pass policy declarations and no- body does anything about them. The rest of the time it’s run by a kind of oligarchic bureaucracy. Most of the people who go to N.S.A. and involve themselves look upon themselves as future Congressmen and Senators.”

At the end of February, 1967. Harris resigned from the presidency of the Stanford student body. "The job had >ecome a trap for my mind,” he explained to me. “I’d done my bit for •uucation, I’d given over two hundred speeches at Stanford and was repeat- ng myself. I'd lost real communica- tion with students because they treated me like a famous figure, they’d just sit and watch me do it and weren’t putting themselves on the line.” Another reason he gave at the time of resignation was: "My contribution has basically been to say things to the community that up to this point the community was afraid to say to itself. I was just a spokesman for a basic way of seeing the university that 1 felt had to be articulated if there was going to be any health}’ notion of education.”

I asked him to name the literature that was most meaningful for him. The list was long, including "almost every religious document,’’ among them the Buddhist scriptures, the Bible, Lao-Tzu’s The Way of Life. Gandhi. Jung. Fromm, Marcuse. Marx, as sociologist rather than economist, Cassirer. Of the novelists—Faulkner, Joyce, Conrad, and of the poets— Tagore, Lorca. “They all come closer to understanding man than anyone else, in their own unique fashion." He writes poetry himself and some of it has been used in a poetry class that another of the student-tenants, Bill Shurtleff. teaches in the garage, where he also sleeps. A small volume of the combined poetry of Jeffrey Shurtleff. an honor student in the humanities, and David Harris is being put together within a cover designed for it by the photographers of the group, students Lary Goldsmith and Otto Schatz; the name given this enterprise—The Peace and Liberation Commune Press.

Harris came to his decision about the draft alone. He belongs to no organization, only the one he and some other students at Stanford and Berkeley have founded—the Bay Area Organizing Committee for Draft Resistance. His first step against the draft was his participation in the sit-in in President Sterling’s office, protesting Stanford’s acceptance of draft tests. "Student deferments are immoral,” he said at that time. "They weed out the people who can afford an education.” In June. 1966, he sent back his student deferment, intending to apply for a conscientious-objector status, but not on a religious basis. A few months after he gave up his deferment, he made his decision about the draft, alone one summer night in his study. "I was just sitting there when all of a sudden, just out of the back of my mind, came the statement: Well, you’re not going to cooperate with them. My first thought about jail really frightened me. I'd never thought about going to jail for a principle against the draft. But from then on I knew what my principle was. I sent them a letter, then, saying I believed myself to be more of a conscientious objector than the law allows because I didn’t believe in the law. I said I was going to break that law. The law is immoral and there's no being moral within an immoral law.”

Reclassified 1A. Harris took his preinduction physical in his hometown, Fresno. “I knew I wasn't going to go along with them, but I wanted to see what they did, who went into the Army. I got to the last table and the doctor there said, ‘Hey, Mac, this is this guy Harris, he’s the guy who’s going to refuse.'” Harris was informed by mail that he was fit; a month later he was informed that he was not. The board had changed its mind, classifying him 1Y— temporary physical or psychological disability—until September. 1967, at which time it will reconsider classifying him back to 1A and Harris will fail to honor the directive to appear for another physical. “What I think about Peace in my own mind, how fully I’m understanding it, helps the growth of Peace in the world. In that sense what I’m doing is a very religious thing. I can't go out and talk about Peace if I don't feel in my own mind that I’m living it as fully as I can. So it's simply a question for me of keeping my own sense of integrity, which is what allows me to do all this against the war and against American society as it is now. It’s essentially my own feeling of integrity. I think that any movement is better for the fact that the people in it are following their highest understanding, and if that means going to jail ... I feel that I couldn't talk about the draft if I wasn’t out in a position facing jail. We have an obligation to speak to the people of the United States, and the act of going to prison is itself a statement ami a much more powerful one to the American consciousness than taking a C.O. or going to Canada. I have a basic hang-up about being run out of any place. 1 was run out of too many places in Mississippi.”

I asked him if he had his speech prepared for the mobilization on Saturday. He said that he never prepared speeches. “I don’t speak about anything that has no relevance to my life. I usually meditate before I speak. You get your mind down to a single point, a pinpoint, and when you reach the pinpoint you go through and come out clean, everything starts opening up and filling out, a fresh vision of everything. In speaking, I try to get to that pinpoint and then I get up and speak. Two years ago meditation was far from my life. I developed it from more and more contact with Eastern thinking, Eastern music. They have a whole different rhythm to their thinking, a much slower, a more cyclical kind of rhythm, and my life just started getting into that kind of rhythm. I'm calmer now, I used to get frenzied. Everything that happens isn’t earth- shaking. It’s like a quantum jump, you break through into a new world. I think there’s a danger, though, in the American, the Western, reaction to Eastern thinking. They try to make themselves Easterners, which to my mind is illegitimate. You can't run around being an Indian if you’re an American, you’re not part of that culture. You go to the Haight-Ashbury, it’s all very speeded up. very hectic, which is the exact opposite of what I associate with Eastern thinking. I’m not saying you can’t learn from it. but what they take is the rote form and they think they've reached Eastern thought when all they've got are the cultural mechanisms. American society understands life in terms of fetishes and can only understand the spirit as a fetish. The people of Haight- Ashbury should ask themselves how much of what they're doing is fetish ridden. Then the culture there is organized around drugs and I think drugs are not a spiritual vortex. There’s a great danger in their seeing things in terms of drugs. Love exists regardless of acid. Drugs can be useful but the nature of that activity is a minimal one. Acid stands knee-high to Peace. The son of a British Prime Minister—about a month before he died of an overdose of heroin he was talking to some friends about shooting smack and he said, ‘At Cambridge everything is just around the corner. But when you go into your room and tie-off and shoot-up. everything is right there in your lap.’ The real problem is how you can make a culture that’s right there in someone's lap.”

He talked about the war in Vietnam: "Johnson is having a hard time holding the whole thing together. I think his next move is a big escalation, invade Laos and Thailand and Cambodia and North Vietnam, and to do that he’s going to have to double his manpower there and that's when the big climax is going to come, because all those people who are on student deferments are going to get called. If they escalate, there's not going to be a student deferment for anybody except engineers and medical students, and all those people in school now are going to be faced with that question by next year. He’s going to try doing it first without being repressive, then he’s going to get this opposition from the youth and he’ll try to clamp down. The chances of anybody saying the kind of things we’re saying now in a year—they'll harass you and bust you. That is, if you start getting people, and it’s clear we’re starting to get people."

He is positive their phone is tapped. "I know from Mississippi how it sounds, anything can foul up your phone when they put a tap in. In Mississippi we could hear the sheriff moving around in his office. I don’t know who they're tapping for—one of the guys who lives here was subpoenaed by H.U.A.C. last summer in Washington for organizing that Stanford blood drive for the North Vietnamese civilians and I'm doing my Peace thing. They interrogated me when I came back from Mississippi because I was saying things about an agent back there who called me a nigger lover. They're meticulous. Every time we have a rally at Stanford there’s always an F.B.I. agent there with his camera, with telescopic lens, taking pictures of everybody."

On Saturday morning, April 15. the marchers gathered at the foot of Market Street, filling up all the side streets for blocks, and when I found David Harris he was with his friends from Stanford and Berkeley, handing out, each from an armload, the Draft Resistance Committee’s “We Refuse to Serve" declarations. By the time the students, numbering one-half to two- thirds of the 65,000 marchers, got started, the head of the procession had already reached Kezar Stadium, four miles away. Long hair and beards, if not the rule, were common in that massive contingent, along with fringed buckskin boots and the heavy kind, sheepskin vests, massed strings of beads. The placard, America, go back, you’re going the wrong way, may have verbalized one meaning, at least, of the costumes: they were out of the West of the last century, of a time before this country went that wrong way —if any reckoning can be made of the time when any country took that turn —and the new frontier these students were advocating was way out beyond the one the late President gave that name to. The rest of the world was no territory for a General by the Dr. Strangelove name of West! More Land! but a great frontier for the spirit. The fragrance of incense sticks drifted through the air that was sometimes misty, sometimes clear and warm, and the Eye of God. the diamondshaped colored-yarn symbol the Mexican Indians carry through their fields, was carried here down the main street. I saw Harris first on one corner, then another as he moved along between the students and the spectators. He was usually findable, being taller than most, but sometimes obscured by the placards and banners.

From a high-sided truck, Country Joe and the Fish, with beards, sheepskin vests, shoulder-length hair, a fur cap on one, and green peace signs painted on their cheeks, rolled out a tremendous rock dirge that set an hypnotic, solemn pace for the mass of students and resounded against the grey facades down the side streets and up Market Street and against the nudie movie where life-size cutouts of a soldier and marine were up on the marquee along with. "This is U.S. Service-men Appreciation Week,” and where A Good Time with a Bad Girl was showing. Further along the way, out near the stadium, musical accompaniment was furnished by three young men beating pots and pans up on a sixth floor balcony and by a Bob Dylan record blaring full volume out of wide- open apartment windows where two elderly women sat with their elbows on the sills, and by a girl serenely sitting on a concrete wall and singing in a high, clear voice “Krishna . . . Hari.”

By the time Harris reached the stadium most of the marchers were already in the bleachers and the speakers assembled on the platform out in the center of the green oval field. With him up there were Mrs. Martin Luther King, Julian Bond, the Georgia legislator, Robert Vaughn, the Man from U.N.C.L.E., Judy Collins, several clergymen, others. He was the only one in Levis and Levi jacket. He spoke very little to those on either side of him, then not at all as he began his meditation. While the others rose and spoke to the filled stadium, their voices blaring out in several directions through the clusters of red loudspeakers on the field, I saw him bend his head to his knees for a time. When I looked again he was sitting upright, his legs crossed, and one foot shaking restlessly.

Country Joe and the Fish, out of their truck and down on the track, struck up with electric organ, guitars, and voice their I-Feet-Like-Fm-Firin'- to-l)ie Rag, familiar to students since the early Vietnam march in Berkeley in 1965 that was halted at the Oakland border by a line of helmeted police. On the track before them a crowd gathered and couples danced to that ragtime mockery of wartime acquiescence.

Come on all of you big wrong men;

Uncle Sam needs your help again,

He's got himself in a terrible jam;

Way down yonder in Vietnam.

So put down your books and pick up a gun;

We’re gonna have a whole lot's fun.

'Cause it's one. two. three. "What are we fightin for?”

"Don't ask me I don't give a damn”;

Next Stop is Vietnam

And it's five, six, seven, open up the pearly gates

There ain't no time to wonder why,

Whoopie! We're all gonna die!

Just before Harris began to speak, down across the field and into the parking lot out of sight behind the stadium wall drifted a black-clad parachutist from an unseen source, his white and black and yellow chute inscribed with the word LOVE.

Harris loomed over the microphone, his face and voice impassioned: “We have to realize we’re mistaken if we call this war Johnson’s war or if we call this war the Congress’ war. This war is a logical extension of the way America has chosen to live in the world. This war is the logical end of the American system that we’ve built, and I think that as young people facing that war, as young people who are being confronted with the choice of being in that war or not, we have an obligation to speak to this country, and that statement has to be made in this way: That this war will not be made in our names, that this war will not be made with our hands, that we will not carry the rifles to butcher the Vietnamese people, that the prisons of the United States will be full of young people who will not honor the orders of murder. . . .”

When he had finished his speech he strode out across the green field to an exit, like a man with no time to lose.

Roommates

Harvard

The traditional college roommate has always been a 280-pound bathless behemoth chosen for you by a sadistic dean of admissions. When you tried to sleep, he snored; when you were studying, he played records, and by the end of the year you really learned how to hate. But the love generation is finding a way out, in ever increasing numbers. In Cambridge, for instance, Anne McConnell. Radcliffe '67, moved off-campus with Paul Mattick, Jr., a Harvard student. The parents who knew made no objection: Harvard didn't seem to care and Radcliffe, because Anne was officially in residence at one of the dorms, didn't know. “About a third of our friends are married." says Paul, “another third just live together, and the rest are. well, still looking for each other." Paul and Anne have come to no conclusion about marriage; he cooks, she irons and they do the laundry together.

Cornell

According to Cornell's records this girl whom we'll call Carol lives in a frame house in Ithica and he ("Mitchell") lives around the corner. Actually they both live here, together with another couple, two other guys and two girls. "We aren't trying to put anything over on Cornell; it's just that we want to live together," Mitchell says. Carol, Cornell '67, majored in Philosophy; Mitchell is a junior in Honors English. The only real problem has been the landlord, who, like Cornell, doesn't know the setup. "One morning he came barging in while I was in bed," Mitchell remembers. "I threw the covers over my head just as he came in, and for five minutes he talked to me thinking I was Carol. I just mm-hmmed in a falstetto." Neither knows how long they will live under the same roof: marriage is only one of many possibilities.

Harvard

"Our parents know." says Ned Shure. He and Patsy Pepper share an apartment with another couple two blocks off-campus at the University of Michigan. An English major. Ned dropped out after two years and now runs the Student Book Service. Patsy is still enrolled in Education. At Michigan male students may move out of the dorms after they have completed their sophomore year, and women when they are twenty-one. Some of them take apartments together. Ned and Patsy share domestic responsibilities with the other couple in a six-room apartment in Ann Arbor. They have a casual relationship: marriage is not really a question yet: at least they never discuss it.

Photographed by Dan Wynn

Berkeley

The way Steve Brauch tells it. one fall night during his junior year at Berkeley he and some friends were walking down the street singing, when Maureen's room-mate leaned out of her window and joined in. Banter followed. the boys invited themselves in. and that's how Steve and Maureen met. Eventually Steve moved in permanently He and Maureen like living together without the legal binds of marriage: they found the one nude party they went to a bore: they have moved a few times, and they live at their present address because the landlord allows dogs.

Zen Basketball, etc. at San Francisco State

by Herbert Wilner

Who knows how to play? The student? The teacher? Who cares?

A guided tour through the hippiest college

Of the more than eighteen thousand students now attending San Francisco State College, only a handful will join the Alumni Association after they graduate. Of the more than one thousand faculty members, most of whom teach here with a provincial pride of place, only a few would insist that San Francisco State should be the college of choice for their own children. Of the wealthy great-name families in the Bay Area who make financial contributions to the institutional life of the community, none contributes substantially to San Francisco State. They give generously, however, to the established empires, Stanford and the University of California at Berkeley. In highway miles, San Francisco State lies almost exactly between these two neighboring academic countries, and the shadows they cast would have seemed large enough to keep the in-between place forever in the shade.

But for a variety of reasons, many of them more nationally important than the recent instant history of the college itself, S.F.S. is worth looking at. It is, in fact, with peeps here and there in professional journals and even in the mass media, being looked at. There is more to its picture than the present prominence of its ninety-four-acre city campus as a second neighborhood for the hippies of Haight-Ashbury who haven’t yet dropped out. It might well be that S.F.S.’s newness, its lack of traditions, its unpredictable and generally older streetcar students, its young faculty and its young come-and-go administrators, its compulsion to be anti-Establishment, its willingness out of conflicting necessities to absorb and to improvise, it might be that this unformed character is the source of its brash and eccentric spirit. And it might be true that this spirit is peculiarly suited to a noisy confrontation with some of the unanswered questions about the new industry we call college education in America.

The necessities confronting S.F.S. are of essentially different kinds, and they grind against each other like gears which were never designed to mesh. In the first place, there is the monstrous bureaucracy which presides over the State College System in California. It has so many offices and officers, so many bureaus and boards and channels, so many regulations, and produces so many tons of mimeographed material full of unreadable statistics and incomprehensible prose that one has to believe there is a clerical factory here large enough to have run the British Empire—Gilbert and Sullivan fashion—a century ago. What is hard to believe is that all of this Kafka-machinery was designed to reach the individual student who comes to class at S.F.S.— bearded, long-haired, or plain—and demands nothing more complicated of his education than that it should interest him and mean something. If it doesn’t, he may drop the particular course. If he drops enough of them, he drops out. The clerks and computers of the college’s own huge bureaucracy will record his vanishing. The figure will be forwarded to the higher stations of the bureaucracy off campus. Added to other such figures, it will finally issue forth as another unreadable document.

To expect S.F.S., which is at its new campus a child of thirteen years, to emerge from the bureaucratic maze which governs the seventeen other state colleges, as well as itself, into an identifiable character and spirit is like asking of a State Department staff member that he speak in his own voice. But it has happened. It has been going on steadily for the ten years I have taught at S.F.S. and it points to the other necessity which the college confronts: an intense desire to make its own destiny in its own character and by its own spirit, the bureaucrats be damned. (But when you damn them openly, the gears of the opposing necessities grind with a public noise. As they did last fall when several members of the English Department joined in a reading on campus of a published poem banned by the San Francisco police for being obscene, the reading making local headlines which prompted one member of the off-campus governing boards to suggest that proposed faculty raises had something to do, after all, with proper faculty behavior. The character and spirit of the college cannot be tagged in a phrase, for there is no long-lasting tradition with which to associate it. But it certainly has something to do with San Francisco itself, and it is surely affected by the life-entangled histories the students bring with them to the campus.

A glance at the campus itself returns something unmistakably and unimpressively institutional. Its ninety-four acres are located on what used to be sand dunes in the southwestern comer of the city. It is not far from the zoo, the Pacific, an artificial lake, and a municipal golf course. It is bordered on two of its sides by the nests of modem housing projects. Its own twenty or so new buildings, if you are sensitive to architecture, are offensively unimagined. On the other hand, they might be regarded as unfortunately suited to the traditionless spirit of the place. They are all so ruthlessly functional, so arrogantly plain, so insistently rectangular or square, so regularly banded or punched with windows that it is easy to believe they all arrived on the same day in huge cartons marked Easy-to-Assemble New Campus. Not one of the buildings bears a personal name. They are all designated by the faculties and subjects they house—Humanities, Natural Sciences, Education, Psychology—as if that too had been stamped on the original cartons. They give off a timid quality of being subject to recall, as if the cartons might be hauled out again, the buildings recrated, and the whole campus shipped back to the manufacturer. But if one is disposed to look at the brighter side of his own metaphors, he can pretend the buildings were designed to make the human condition prevail over the masonry which houses it.

The most telling feature of the physical arrangement doesn’t belong to the college. It is the municipal streetcar marked “M" which passes one of the college’s comers on a main artery of the city’s north-south traffic. For S.F.S.—despite its two new Residence Halls on campus which house eight hundred overprotected students—is essentially a streetcar college. As such, it shares some of the characteristics of similar institutions throughout the country: a higher average age for its students; a full program of evening courses; part-time jobs in the city for most of its students: a sense of personal connection with the college that is limited for many of its students to individual professors and a particular department; a general lack of interest in the college’s sensibly modest athletic programs.

Above all, S.F.S.’s identity as a streetcar college ignores the idea of the campus as a fortress, or a retreat. By way of that overcrowded “M” car, or the student’s own auto, some of the city’s living implications are brought to the college, and some part of the college is returned to the city. More than anything else, this transportation accounts for the living day working its influence upon the general academic intention.

I came to S.F.S.’s English Department and Creative Writing Program after two years of teaching at ...

Painting the Ocean Red, Etc. At Colombia University

by Dan Carlinsky & Bernard Lefkowitz

Why not?

Every day is Christmas for members of the Warmth Movement, and anything is possible

Inside the elevator a Phi Beta math major in a faded blue work shirt leans against his rake. Columbia: 37 divisions, 17,000 students. A short girl with a tawny complexion and almond eyes threads her needle. Columbia: annual budget, $127,500,000. An Exeter alum in a wrinkled Brooksweave stares into his orange- painted barrel filled with clothing. Columbia: twenty-one Nobel Prize winners. A varsity wrestler spins the wheels of the caboose of his electric-train set. Columbia: landlord, Rockefeller Center.

Seventh floor. The elevator door slides open, the four turn left, climb a short flight of stairs. They stand now at the always open door to the attic of the Columbia Journalism Building. They stand under a simple crayoned sign: warmth.

A year ago the walls were a dirty beige color and hundreds of dust-covered volumes were stored here. Now the color scheme is red with irregular splotches of orange. In one comer a rabbit named Gandalf munches lettuce, and a monkey named Milton chews the cover of An Introduction to Organic Chemistry. In the center of the attic, a theology student performs a mock-serious marriage. “Do you think it'll last?” asks the groom. “Until we get bored,” says the bride, in mini-skirt. Red and blue light bulbs flash forty times a minute and twin graffiti proclaim: Satan is DEAD and WE LUV.

At the doorway, the four students announce their arrival. Rake: “Why were there only two guys down at the collective farm? There are thousands, millions of rocks to pick up. I can’t do it all.” Needle: “I need help. I’ve got four shirts to mend from the last sew-in.” Barrel: “He gave me everything. His records, his socks, his shoes, his razor, his sarape. It’s all his love offering. Everything." Caboose: “I need a motor for a Lionel chief. Anybody got a motor for a Lionel chief?"

They are plotters, these four, and all the rest who have painted daffodils on barren walls and raised com where weeds grew. Here at the warm core of cool Columbia, they plot the gentlest of social revolutions.

What is revolutionary about electric trains and Monopoly games; about mending tom shirts and distributing clothes in orange-colored barrels to the poor of Harlem and Bedford- Stuyvesant; about tending a collective farm next to the birthplace of the Manhattan Project; about renting bicycles to students for fifteen cents an hour, designing an outdoor cafe on a crowded urban campus or painting an attic bright colors? On the surface, nothing, really. In fact, the idea—the word philosophy brings a blush—behind this movement is so straight, so square, so feverishly romantic, that it would embarrass the creator of Search for Tomorrow. “Our values are truth, beauty, love,” says Ronald Lane, the twenty-one-year-old sociology major who founded the organization called Warmth. “We want people to think differently about what’s important to them," says Jonathan Krown, son of a wealthy Long Island builder. “Why shouldn’t you trade a mink coat for a nice red apple? Why hasn’t somebody cleaned up the Lower East Side? Why hasn’t anyone dyed the Atlantic Ocean red? It would be so beautiful.” Or, as Jim Gagne, fraternity man, psychiatrist-to-be, explains, “I was looking for a Christmas spirit. Here’s where it’s at”

Thus powered by its own version of Life Can Be Beautiful— at Columbia or in Harlem—encouraged by the dedication of fifteen or so true believers, inspired, partially, by the mystics of Haight-Ashbury, and financed with a $300 subsidy from the university. Warmth proceeds in its revolution. Perhaps a year is too short a time to reshape embedded values, but this is the way one organization has begun the task:

Love offerings for the ghettos: Warmth negotiates to buy a bus (“$200 is our top price”), plans to paint it in favored hues and load it with barrels filled with clothes and appliances, solicited from teachers, students and residents nearby. (“Remember, this is not charity. They must give away something that they like, too, even if it's a ball of yam in exchange for a fine pair of pants. The idea is that giving and taking become beautiful in themselves.”)

Sweep-ins: the target is those New York parks missed by former Parks Commissioner Thomas Hoving, starting with Morningside Park, adjacent to the Columbia campus. Several hundred students arrive with brooms, inexhaustible supplies of Day-Glo paint (pink for rocks, blue for garbage pails) and half a truckload of fertilizer. Object: to discover the green that lies beneath a carpet of broken bottles, orange peels and other, more exotic, garbage. “It’s such a beautiful idea,” Mayor John Lindsay said recently. “I plan to pitch in on some of the sweep-ins myself. Beautiful.”

Happiness graduation ceremony: in Riverside Park on Manhattan’s West Side, presentation of diplomas ("This is to certify that you have graduated from mediocrity to happiness”) followed by a scream-in at which thousands “yell as long and as loud as they have to.”

Collective farm: on a 95- by 120-foot dirt plot on the Columbia campus, fifteen students on their knees pick up rocks and toss them into metal tool chests. It is the only farm, collective or capitalist, in Manhattan. Object: to grow com, potatoes, beans, radishes and carrots. Says Yale Psychology Professor Kenneth Keniston, author of The Uncommitted, a major study of alienated youth, “The idea of a collective farm on a campus is absolutely delightful. It’s the perfect cry against the machine.”

Making Columbia livable: a bike-rental stall; an outdoor cafe designed by architecture students; for anyone who wants it, free breakfast in the Warmth attic, served on dishes donated by the university dining rooms; a woodworking shop; a do-it-yourself restaurant where students will cook their own meals; ice-cream shacks where a dozen flavors are sold at discount; Operation Warm Welcome, a service to match visitors with Columbia apartment dwellers willing to put someone up overnight without charge; quick-cash soda-bottle return (“Please leave deposit bottles when you’re through with them. If someone needs money he can pick up a couple of bottles and cash them in”).

Making Columbia lovable: kite-flying from the roof of Butler Library (3,700,000 volumes); nonverbal communication sessions, in which two hundred students gather in the attic to carry on silent discussions through finger-painting, the rhythm of raga rock, and bubble-gum sculpture, while two floors below student journalists practice verbal communication in a TV studio; Sadie Hawkins Fortnight, a magic time when “girls ask guys out and friendliness is not aggressiveness.”

And more: alienation booths for the bugged to sit in, punching bags for the hostile to slug at; a student ombudsman for the aggrieved: the complete collection of Parker Brothers games for mind-weary intellectuals.

For John Sloma, an editor of the undergraduate literary magazine and a prime Warmth attic addict, it all adds up to a convenient retreat. “I first came to the attic sew-ins, at which Barnard girls mend the torn shirts and buttonless jackets of Columbia undergraduates, attract two hundred or more participants. Many of Warmth’s casual members say they are drawn to the attic because of the relaxed, undirected atmosphere there, and incidentally because it can be a good place to make a date.

David Rynerson. an eighteen-year- old apple-cheeked freshman from Portland, Oregon, helped Lane paint the entire Warmth attic during one weekend last December. “I’m kind of a shy guy," he says, “and my social life at Columbia was pretty much limited to the laundry agency, where 1 worked. 1 mean, you don’t meet too many girls there. 1 don’t do too well at dances and mixers because 1 don’t have much of a line. I came up here because I thought, well, you don’t need much of a line at a nonverbal communication thing or to play Monopoly with a Barnard girl or to ask a young lady to sew a button on your shirt. You know, I ripped three buttons off my shirt once so I could go to a sew-in. But the funny thing is, I’ve almost forgotten that I came up here just to meet girls. I’ve worked on the farm, and painted the attic and built things. The Warmth attic is a very nice place to just go and do your thing.”

Although Warmth has gained a mass following on campus as a localized non-organization, there are some who would make it into a collegiate complement of the Diggers who live in San Francisco’s hippie Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Jonathan Krown. a sometime Warmth leader who has initiated most of its off-campus explorations, believes the amorphous Diggers are powering a social revolution in America: “It's really what’s happening. Their love is destroying the great coldness floating around us. You have to be close to a place like ‘Hashbury’ to understand it. It's a tremendous feeling. The Diggers—those are the ideas we need here."

It was Krown who served as catalyst for the public Happiness Graduation Ceremony, the Harlem program, and the Park Sweep-in. But not without some small resistance from those who are afraid of spreading Warmth too thin. "I don’t approve of the Diggers,” says Barnard student Janet Tang. “They’re out trying to save the world. A lot of that type might bring the pot element into this. If we got busted. . . .” One disaffected Warmth organizer, Robert Levine, says. “I just don’t think the world is ready for this. They might want to change the world but they can’t act as if it’s already changed. I got nothing against love . . but I just can't believe these people.”

It’s two weeks before spring planting on the collective farm. The sunny Saturday afternoon has brought a dozen students out to till the soil. The only implements they use are two pitchforks and two rakes, purchased with the proceeds from a light show. Piled under a tree are many packages of vegetable seeds contributed by a seed company.

In one corner of the field a mophaired eight-year-old boy is busy picking up pebbles. A student looks up from his raking and says, "That’s Peter. He lives near here and one day he asked us if he could plant flowers. So we gave him that little corner. It’s our best soil." On the sidewalk outside the campus, an elderly woman in a blue suit, wide- brimmed hat and veil stops to watch. “I guess,” she says to no one in particular, “that’s the way they earn money. I used to do gardening after school when I was young. . . . You’re getting paid, aren’t you?” A pretty, dark-haired girl looks over her shoulder at the woman. "Oh no, we're not taking money for this,” she says. "You're not? Isn’t that wonderful!” Raising one gloved hand she points to a kid with a beard. “Isn’t he just too cute for words? A farmer."

On the sidelines a girl has arrived with a pitcher of lemonade. A few feet away another girl in corduroy pants and a sweat shirt picks up rocks and gathers them into a small pile. She plows up the dirt with her hands. Two boys passing by shout at her, “What’s this?” The girl says, “It’s Warmth.” “What are you doing?" they ask. “I'm planting morning glories. They let you plant whatever you want here. It's great for us poor displaced country girls.”

Ronald Lane, graduate of the Bronx High School of Science, sociology student at Columbia University, watches.

"Isn’t this amazing?” He laughs. “Isn’t it amazing. Just like I thought it would be. You know what someone called our attic yesterday? The world's largest tree house. And this is the world’s largest sandbox.

“It’s unbelievable what you can do with love. Do you know, we could go around the country and get thousands of loving people, wonderful people, and all move to like, Nevada. We could take the state over. It would be our state. We could open our own stores, and build our own communities. . . . We could work together and help everybody and laugh and give things away and be given things out of love and change our names and laugh at fear. We could make it the warmest place in the world." W-

Confessions of a Campus Pot Dealer

I turned on 200 fellow students at U. of Mich

by "Ric"

This isn’t a confession. It’s more like letting you in so maybe there’ll be a slight chance you won't walk around spilling all that typical misinformation I hear and read wherever I go. For instance, after the big midwinter bust in Detroit, some professor came on the late news and gave his sixty-second serious-dangers-of-narcotics speech, which he picked up from a 1937 ad. After four years of college I can tell. You’re flying blind, middle-class-land, and it’s fear and Plymouth Rock hardheadedness that makes you tear down Maypoles. Not much of a change since Sixteen-twenty. Anyway I’ll lay off the message. Don’t get scared so soon—let me entertain you.

I’m a pusher. I should say I was a pusher. Attention system: I am no longer. Just in case you’re interested. I quit because it became a hassle. Too much business—I developed this real capitalist outlook. Sitting in my room with the door locked making stacks of my money. I caught myself and got out. Like Hesse’s Siddhartha. He went to the river. I just went straight. Good boy me, diploma in hand ready to step into my slot—but that’s another story.

I pushed in my senior year at the University of Michigan, starting I remember after I quit this incredibly boring job showing early-morning educational movies. We were sick of buying lousy grass at exorbitant prices around Ann Arbor, so over Thanksgiving we all chipped in and bought a pound in New York through one of our business associates who lived there and knew a fairly reliable contact. It cost four of us about thirty-five dollars apiece and after weighing it on these great homemade blind-justice-type scales we each wound up with four honest ounces. Then the idea hit—we could sell a couple, make back our investment, and still have buckets to smoke ourselves. So, we cut the stuff up—this is a technique we eventually got down to a real science— and packaged the ounces in baggies. Now we had to find a market. At the time, see, we were just looking for a few friends who might want a decent deal, and we’d come out with free grass. So I phoned up a chick I knew who smoked quite a bit and asked her to look around. About a half hour later she called back with an order for three ounces. We were in business. Our pound went within two days and people were lined up begging for more. What could we do? You have to understand that this is a pretty common way for pushers to get started. They’re not these crummy, slinky, little junkies you read about turning school kids on to pot and dirty pictures. It’s the puritan ethic, people, the capitalist way—make a buck. Sure, simple supply and demand—like loan companies and bootleg liquor—hell, like used-car lots and Gimbel’s basement. Nobody’s a nonprofit organization. One of my partners is an economics major. He filled us in on the real story: just business as usual in the true American tradition.

Before I started pushing I was a long-haired sometime-student Ann Arbor fringe member, cashing my monthly check from upper-suburbia home, and after I started I was just the same—only I was independently wealthy, my parents could save their money for Miami Beach. I mean I didn’t make a fortune—just enough for records and repairs on my car and of course reinvestment. After our first success we decided the market could easily bear a kilo at a time—which is two-point-two pounds (thirty-five ounces) and costs usually around two hundred and fifty dollars—naturally the more you buy the cheaper it is. We got hold of a Detroit contact through an amazing kid—a Wanderer dropout who knew everybody and everything that was happening, especially the younger hippies and old-time hard-core heads. See, each of us eventually developed his own clientele, from the Wanderer’s friends to fraternity straight people just getting into the thing. Anyway, we TyJ began in full swing after Christmas with a trip into Detroit for two W kilos. I didn’t go along and I didn’t ask questions so I can’t tell you ° much about it. Except that it was bad sugar-cured grass that dried up to nowhere near four and a half pounds, but got sold eventually for a not-too-disappointing profit. Fact is, the New Yorker and the Wanderer had to put up the cash, so they took charge of the whole bit. During that time all I got was free grass and lots of customer inquiries. Then rumor filtered in about a big bust, snow started pouring down, and Midwest winter doldrums hit us. Everybody was still jumpy about the fifty-six heads they hauled in in Detroit—we locked up all the grass, pipes and paper in a sympathetic sorority house and sat uptight. This was very safe but I remember one slushy night we drove all over Ann Arbor looking for the silly chick who had the stuff in her room while customers complained and we pined for a pleasant high. In short the situation got a bit grim, and the New Yorker decided now was a good time to make it down South—with Wanderer, who grabbed a ride just out of the clutches of the local narcos.

A few days before they left we gathered up some money and drove into Detroit so that I could be introduced to our contact and start a regular transaction while the others were in Florida. We drove through a few streets of Jesus Saves churches and parked next to a typical grey row of Victorian monstrosities turned into student apartments. Looked pretty much like the rest of Detroit, I guess. We knocked on an upstairs door of one of these places and a skinny chick answered. I was nervous the contact would close up because he didn’t know me, but the chick said he was sick anyway and wasn’t selling. We argued for a while about telephone arrangements that had been made and the hassle to drive here in rush hour, but she held her ground and stared us down. After a few minutes we left, pissed off. The whole place smelled like chicken soup. See, big pushers are real too.

Well, now we were in sort of bad shape—not even a joint to smoke ourselves. We killed time drinking cough syrup for about a week, and then one day our fraternity partner got a great surprise package from the capital city—an almost full kilo of beautiful grass in a plain brown wrapper. Maybe a little risky but it did get through addressed to Zelda Zero or something. And we were back in business. This was just before the University of Michigan's two-day spring break at the beginning of March and we wondered if anybody would be around to buy. We opened up sales with a few discreet phone calls after spending half a night cutting and weighing and smoking (for testing purposes) and by suppertime the next day we were clean. Not even a pipeful left between us. Our enterprise was really rolling. It gave us enough money to fly East for the vacation—half fare of course. I mean we weren’t lighting our cigarettes with dollar bills. In fact, after every sale I got tighter and tighter, like J. Paul Getty. I told you that’s why I quit.

Time in college is measured between vacations, so I called the two months after Christmas until spring break our building-up period, and after that, from March till we went home at the end of April, our solid establishment time. We started pushing with comfortable regularity. We got a motto: Buy low. Sell Highs—sort of cute. The important thing was we made a name for ourselves in town. Sometimes it got a little out of hand. One night my straight room-mate brought back incredibly blown-up reports of our business from a sorority house I didn't even know existed. Our big boast was that we never promised, we delivered. There were endless stories circulating about the kilo of Acapulco Gold (supposedly good grass) somebody’s gonna get for seventy dollars, but these same characters always showed up for a few ounces whenever we sold, complaining about our prices and our small amounts. Next week, forever ma liana he’d be in the Gold—just doing us a favor for the time being. Also we were strategic. Like G.M. stockpiling for the big year, we’d hold up on our sales until we were sure that the market was empty and then we’d open up shop to lines of ten-dollar bills.

We alternated buying between Detroit and New York, and although New York City was more chancy, because of the distance, the grass was infinitely better and a lot closer to the real weight—never more than an ounce or two off. Detroit was dishonest through and through. One time sticks in my mind. The contact —he’d gotten over his flu I guess— called us later in March with a great deal on good grass. And he was anxious to get rid of it. All three of us drove in the next afternoon bulging with money and went up to his crummy room. He had a friend along, a dark greasy guy with his two-year-old daughter, who cried the whole goddam time. There’s a technique to buying; first you bullshit, sit around and talk about business, busts, play the guitar, look at his psychedelic pictures. Everybody’s real friendly and phony. Nervous. Then you say, "Well, we'd like a kilo.” They go, "Yeah, sure, fine”—give you some wine. You wander around a little bit more and finally you ask what’s the price. You look at their eyes which start to sneak all over the place.

"Two ninety,” they say.

"What? Two ninety! Come on, we never pay more than two and a half. That’s the standard rate.”

And you hassle. So after we’ve made it clear, they give us a line about the guy who owns the stuff wants two ninety. It’s not their fault, but the greasy guy goes, "I'll put up twenty bucks.” This guy won’t call marijuana any of the regular names like grass or pot—he’s gotta call it "weed” and "boo” (I was waiting for "maryjane”). And the contact says, “Sure, I'll put up another twenty and we’ll take, lemme see”—he figures it out too fast—"one seventh of the kilo." But what the hell, we wanted the grass. It was a prime time to push in Ann Arbor. Wanderer had left New York by then, leaving us without a contact there. And the little kid’s crying was really bringing us down. So of course we gave in. They took the money and disappeared for a half hour. I figure they went to the greasy guy’s place where they had it stored—probably around the corner—laughed for a half hour, and came back. It’s not hard to figure. They poured out this damp pile of seeds and stems, “It’s good weed, man.” Yeah, it looked like the Sequoia National Forest. Then they took a coffee jar and measured out their one-seventh—five "cans” (he wouldn’t call it ounces), packing it in so they got at least six. And that was it. Friendly good-byes all around. We were still hopeful on the way home that we’d get anyway around thirty ounces. It looked like quite a bit sitting in its week-old National Enquirer wrapper. We rushed in and put it on the scales: a bare twenty-five “cans.” We got burned. It meant in sales a hundred and twenty-five dollars short. That hurt. And we felt bad that all our customers were going to get a mighty weak amount for their parents’ money. What do you expect? Dishonesty breeds dishonesty. For instance, later on we got a real kilo from New York and sold whopping real ounces —almost. A pusher is not without a conscience. One consolation is that we heard those two got busted big later on. Which I guess I wouldn’t wish on anybody.

Obviously we stopped buying from Detroit then and there and the rest of the year was relatively normal. Quiet, steady pushing to our quiet, steadily complaining, no-face, noname clientele. It’s funny. On my rare trips to campus and classes from my almost upper-suburban instantelectric apartment just down the road, the only people I ever recognized among the thirty thousand were my customers. But it’s not like the local merchant who tips his hat to his clients as he walks to church. There wasn’t even the slightest bit of recognition shown between us. Not a glance. Strictly business—a different world entirely when I was a pusher than when I was a student. And not a chance the twain ever met.

Anyway the snow finally melted in Ann Arbor and the temperature soared to sixty during the last few weeks and I took to sunning myself. I explained it all in the beginning. I closed the store, got stoned, and relaxed on my roof—spent all my money on nothing and went back to being poor. Believe me, businessman, it’s just as good.

Now, let me explain. I’ve sort of mentioned a lot of terms I figure you should be conversant with after all those Time and Saturday Evening Post stories about the worthless addicted New Generation, but I’ll fill you in anyway from my side of the fence.

Grass—marijuana—is a minor psychedelic weed, grows almost everywhere. You always hear about police burning a vacant lot full of it in some big city. And when we get it from the big suppliers it’s either in a pile of loose stems, seeds and leaves, or compressed into different-size blocks. Our job is to cut it and clean it and package it for sales. We chop it up first on a grater then push it through a strainer until it's fine. Seeds can be mashed between two bricks and mixed in, but the stems are a problem. If we were going to sell only top-rate pot we'd take out all the seeds and stems, and market just the finely ground leave?, but that would cut our profit a few hundred percent. The trick is not to cut the stuff too fine because the customer would much rather buy a fuller bag of crap than a thinner bag of really beautiful stuff. We measure ounces by eye—that is if we get an honest deal and there are around thirty-five ounces in the kilo, we split the stuff into thirty-five piles and pour them into little manila envelopes. Most often though, we get burned to some extent, so we have to create arbitrary ounces—anywhere from a half to almost a full ounce, and sometimes we’ve really been taken, like the time I told you we got two kilos of grass that was cured in sugar (an expedient to dry it) and still damp. It looked big and weighed a lot, but in less than a week it dried up and shrank away to some fluffy, gluey, worthless waste in the bottom of a shopping bag. In such cases we’re forced to beef it up with green tea, which makes your throat into raw meat after a couple joints, but otherwise not even an old-time hard-core smoker can tell the difference. See, we figure on a three-hundred-percent return on our investment. An ounce sells for twenty-five dollars. That means we pay no more than eight bucks for the same amount—no matter how thin it is. Smaller quantities are even more dishonest. A nickel bag—five dollars' worth—should be a fifth of an ounce but we always get at least seven nickels to one ounce, or three dimes—ten dollars’ worth each. If you stretch it you can make forty or even fifty dollars on one ounce by selling it in nickels and dimes. I can never understand the guy who comes in every other day for a skimpy nickel instead of saving a while and getting a whole ounce at half the price. I mean it's not like he’s hooked on it. Customers are funny. Some hassle for an hour before they buy and some don’t even open the envelope. We always give them the same blurb: “It’s good grass, man, and it cost us a fortune—you’re getting a good deal.” They usually pay.

You wouldn’t believe the cross-section of people coming in to buy. It’s impossible to type our customers—they’re not all long-haired dropouts by any means. You figure: there are thirty-one thousand students at the university plus a couple thousand hangers-on and a few hundred highschool hippies—all potential customers. And we four businessmen had our finger on the whole action. My clientele revolved around one intellectual sorority and their non-student very hippie friends. I also took care of a lot of people just getting into the thing. See, our business wasn’t just sales, we were our own promotion men. We turned newcomers on by the living room full—even the straightest, strictest Wasp chick would come out after an evening of logical argument and pipes of grass convinced and stoned. And back for more soon. My fraternity partner turned on half his house overnight and when I saw these ultraconservative kids a few weeks later their hair was already starting to grow. What an influence. The frat-head’s customers also were two or three other fraternities and sororities, mostly beginners who didn’t argue about price and quality, but smoked in huge quantities—because they were beginners it took them a lot to get high. Every once in a while we’d run into a real case—someone who just couldn’t get high. So we’d empty out a closet, give him a huge pipeful, a couple packs of matches, and stick him in. The closet would fill up with smoke and after an hour of breathing pure grass instead of air he’d stumble out completely stoned. Success. People know when they're high. It’s when they stop asking how they should feel—and start smiling. We turned on one very orderly crabby type straight man with about a nickel bag (enough for about five heads to get stoned on) and he sat there grinning like an idiot, listening to an incredible Ravi Shankar raga, just saying very quietly, “Yeah. That's nice.”

New Yorker’s clientele was quite different. They were the real smokers, mostly from one arty-type section of town that has withstood the modern cement-cube apartments, and from the M.U.G.—the Michigan Union Grill—where the high-schoolers and the more showy hippies hang all day. Half of them are students, if that many, and they’d usually follow Wanderer for grass back to New Yorker’s apartment, which was strategically placed between their psychedelic pads and the Union.