Eugene Linden

The Wife Beaters of Kibale

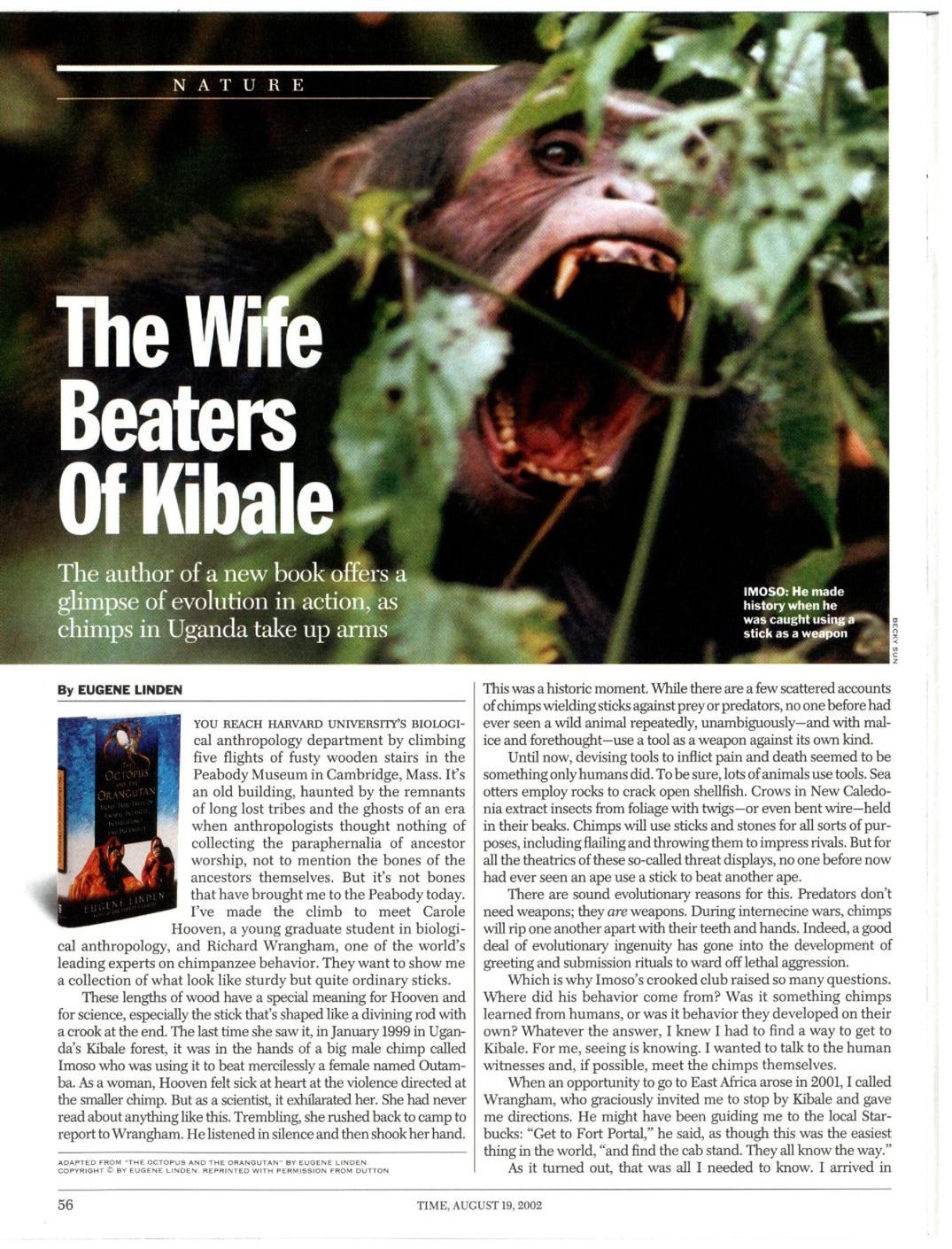

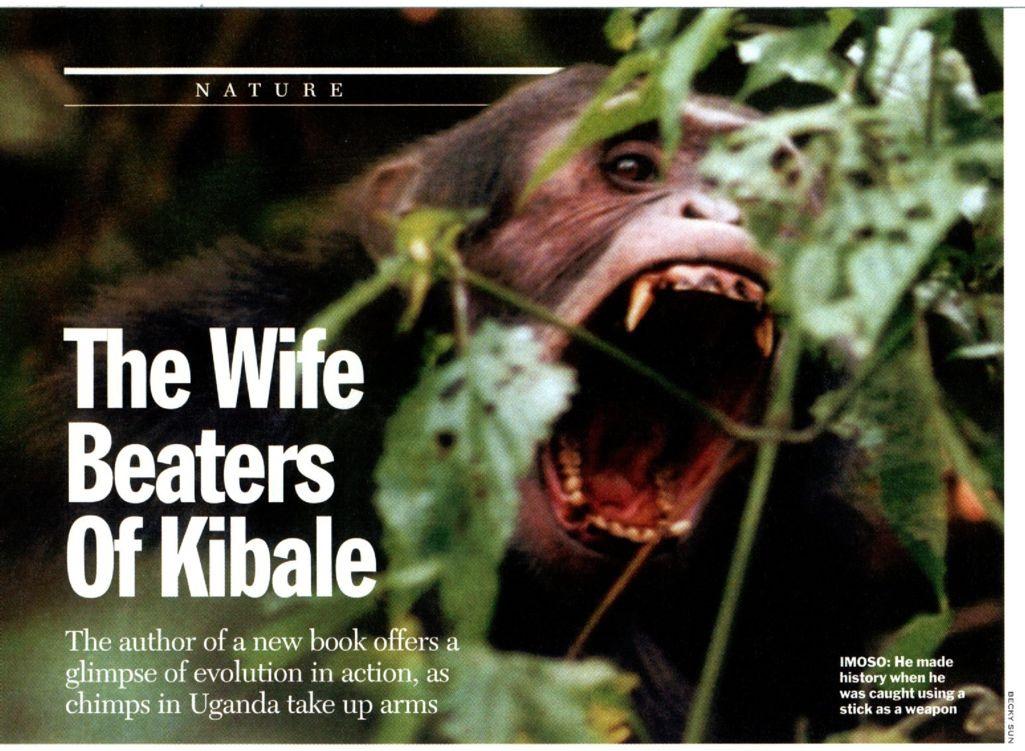

The author of a new book offers a glimpse of evolution in action, as chimps in Uganda take up arms

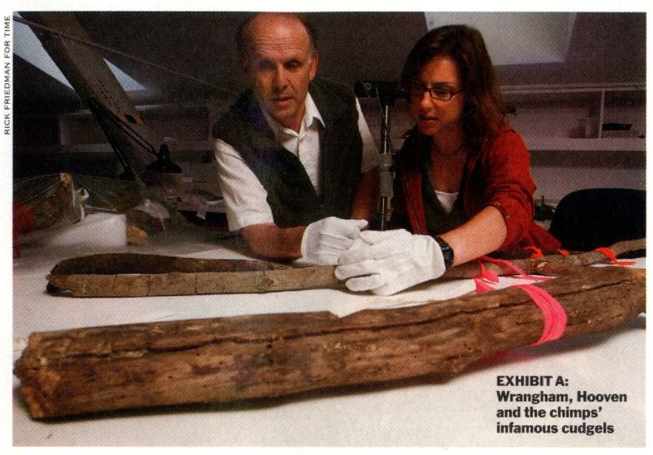

You reach Harvard University’s biological anthropology department by climbing five flights of fusty wooden stairs in the Peabody Museum in Cambridge, Mass. It’s an old building, haunted by the remnants of long lost tribes and the ghosts of an era when anthropologists thought nothing of collecting the paraphernalia of ancestor worship, not to mention the bones of the ancestors themselves. But it’s not bones that have brought me to the Peabody today. I’ve made the climb to meet Carole Hooven, a young graduate student in biological anthropology, and Richard Wrangham, one of the world’s leading experts on chimpanzee behavior. They want to show me a collection of what look like sturdy but quite ordinary sticks.

These lengths of wood have a special meaning for Hooven and for science, especially the stick that’s shaped like a divining rod with a crook at the end. The last time she saw it, in January 1999 in Uganda’s Kibale forest, it was in the hands of a big male chimp called Imoso who was using it to beat mercilessly a female named Outamba. As a woman, Hooven felt sick at heart at the violence directed at the smaller chimp. But as a scientist, it exhilarated her. She had never read about anything like this. Trembling, she rushed back to camp to report to Wrangham. He listened in silence and then shook her hand. This was a historic moment. While there are a few scattered accounts of chimps wielding sticks against prey or predators, no one before had ever seen a wild animal repeatedly, unambiguously—and with malice and forethought—use a tool as a weapon against its own kind.

Until now, devising tools to inflict pain and death seemed to be something only humans did. To be sure, lots of animals use tools. Sea otters employ rocks to crack open shellfish. Crows in New Caledonia extract insects from foliage with twigs—or even bent wire—held in their beaks. Chimps will use sticks and stones for all sorts of purposes, including flailing and throwing them to impress rivals. But for all the theatrics of these so-called threat displays, no one before now had ever seen an ape use a stick to beat another ape.

There are sound evolutionary reasons for this. Predators don’t need weapons; they are weapons. During internecine wars, chimps will rip one another apart with their teeth and hands. Indeed, a good deal of evolutionary ingenuity has gone into the development of greeting and submission rituals to ward off lethal aggression.

Which is why Imoso’s crooked club raised so many questions. Where did his behavior come from? Was it something chimps learned from humans, or was it behavior they developed on their own? Whatever the answer, I knew I had to find a way to get to Kibale. For me, seeing is knowing. I wanted to talk to the human witnesses and, if possible, meet the chimps themselves.

When an opportunity to go to East Africa arose in 2001, I called Wrangham, who graciously invited me to stop by Kibale and gave me directions. He might have been guiding me to the local Starbucks: “Get to Fort Portal,” he said, as though this was the easiest thing in the world, “and find the cab stand. They all know the way.”

As it turned out, that was all I needed to know. I arrived in Kibale one evening just as the sun was setting and introduced myself to Kathi Pieta, a graduate student who ran the research station. Over dinner, she told me a bit about the local chimp community.

The so-called Kanyawara group consisted of about 50 chimps, including about 10 adult males and 17 adult females. Imoso was the top dog. Young and very aggressive, he was not very popular with the human observers, and his reputation did not improve with the discovery that he was a wife beater. The best description of the first attack comes from Hooven’s field notes. Imoso had been trying to get at Outamba’s infant Kilimi, but Outamba fended off his efforts. This seemed to enrage Imoso, who began kicking and punching Outamba. To protect her baby, she turned and exposed her back to Imoso’s fists.

Here is how Hooven described what happened next: “MS [Imoso] first attacks OU [Outamba] with one stick for about 45 seconds, holding it with his right hand, near the middle. She was hit about 5 times ... he beat her hard. (The stick was brought down on her in a somewhat inefficient way ... MS seemed to start with the stick almost parallel to the body and bring it down in a parallel motion. There was a slight angle to his motion, but not the way a human would do it for maximum impact.)”

After resting for a minute, Imoso resumed the beating, this time with two sticks, again held toward the middle. Imoso then began hurting Outamba in a number of creative ways, at one point hanging from the branch above her and stamping on her with his feet. To Hooven, the attack seemed interminable. Toward the end, Outamba’s daughter Tenkere, 2, rushed to her aid, pounding on Imoso’s back with her little fists.

But the trouble didn’t stop there. Imoso’s behavior was observed by other chimps in the community, and he may have inspired imitators. In July 2000 Pieta watched as Imoso’s best friend, Johnny, attacked Kilimi, the infant who figured in Imoso’s earlier attack. Outamba turned to help Kilimi, whereupon Johnny turned on her. Immediately Outamba became submissive, but Johnny was not to be appeased. He picked up a big stick and started striking Outamba. “He was definitely trying to hit her,” says Pieta. “It wasn’t just flailing or accidental.” He used an up-and-down motion. The whole attack lasted about three minutes. After the chimps moved on, Pieta retrieved the stick, which now resides at Harvard.

The next morning I arose at 4:45 a.m. and joined Pieta and two trackers in search of Johnny, Imoso and the battered Outamba. After a vigorous walk we got to the area of a fruiting ficus tree near where the chimps had built their nests the night before.

There were Johnny, Outamba and a number of other chimps. Imoso was not around. When I asked a tracker named Donor why Imoso had attacked Outamba, his answer was straightforward: “Imoso is just a mean chimp.”

That morning, all was peaceful. The principal drama I observed was the struggle of a 3-year-old female chimp whose arms were too short to grab the broad tree trunk. When she finally found a way into the ficus via a nearby sapling, the trackers applauded. The chimps went about their feeding, and then moved off. As they melted into the brush, I asked Pieta which chimp typically made the plan for the day. As one who was familiar with the jockeying for position in the ape community, she laughed and said, “Johnny thinks he does.”

In all, the researchers have documented six stick attacks (the most recent seven weeks ago). The behavior is new to science and raises intriguing questions. Why have all the victims been female? And why sticks, why not stones? Imoso could have killed Outamba by slamming her with a heavy rock.

That may be precisely why they use sticks, Wrangham and Hooven speculate: to inflict hurt rather than injury. Most of the attacks have been directed at sexually active females. Whereas the males might intend to do real harm to the babies, they have nothing to gain by killing their mates. Brutal as it seems, could it be that the use of sticks signifies restraint? That is one of the mysteries Wrangham and his colleagues are trying to solve, in what they view as a snapshot of the evolutionary process in action. This may be a mirror of how we evolved culturally—by the spread of ideas that moved through our early ancestors in fits and starts.

Back in New York City, I experience the familiar sense of relief that comes from returning safely home from an impoverished, disease-ravaged region. Three days later, as I drive my son Alec to nursery school, we hear a radio bulletin announcing that a plane has slammed into the World Trade Center. My son asks, “Is the plane going to be all right, Daddy?” How do I shield a 3-year-old from the enormity of what has just happened? I’m at a loss. I simply say, “I don’t think so.” We humans have ways of killing ourselves that chimps could never imagine.