Eve Byron

10 years ago, Unabomber arrested

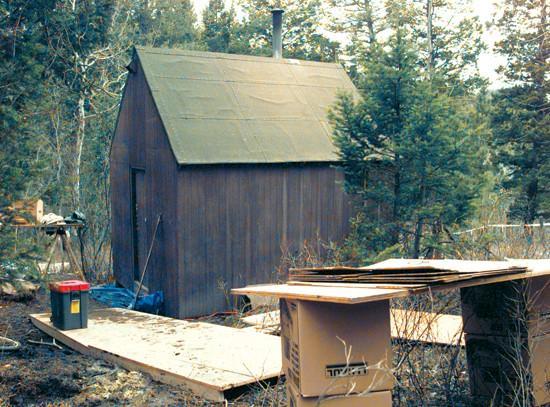

Ex-Forest Service worker pulled Kaczynski by the arm from his Lincoln-area cabin

Jon Ebelt/Independent Record

Elaine Thompson/Associated Press

Jerry Burns’ hands were shaking slightly as he and two undercover FBI agents walked toward a small shack in the mountains south of Lincoln on the afternoon of April 3, 1996. An orange surveyor’s vest and Carhartt coat covered Burns’ bulletproof vest.

“Ted, are you home?” Burns called out, in the manner a woodsman would do when walking toward someone’s hunting camp.

“I heard some scurrying in the cabin, and when Tom (McDaniel) and I got next to the door, Ted opened it.”

“Ted” was Theodore Kaczynski, who later confessed to murdering three people and injuring 23 others with mailed bombs during a 17-year crime spree.

Burns, who recently retired from law enforcement with the Helena National Forest, can smile now as he recalls his encounter with the man known as the Unabomber.

That wasn’t the case on that crisp spring morning 10 years ago. No one knew how Kaczynski would react when approached, whether his home was booby-trapped or whether he had other bombs in his 10-by-12-foot cabin.

“I’m thinking there’s 60 FBI agents here, and I’m the one who’s going up to the door. Either they’re really smart or I’m really dumb,” Burns said. “(Kaczynski) put one hand on the doorsill and stuck his head out the door. It was a little bit of a shocker, this wild hair and all.

“I said we were with the mining company and asked if he would show us his property boundaries. He said, ‘Just a minute,’ and went to step back indoors. I grabbed his wrist — he weighed only about 130 pounds because he was living off snowshoe rabbits — and between that and the adrenaline, he came flying out of the house.

“I put a wrist lock on him, and Ted was kind of struggling like you would if someone pulled you out of your house. Tom and I were trying to handcuff him, and I told him, ‘Ted, you act like a gentleman and we will.’ The wind just went out of him.”

It’s been 10 years since the world was shocked by the news of the arrest of Kaczynski, a reclusive mathematical genius who terrorized the public and frustrated law enforcement officials during a bombing spree from 1978 to 1995.

He was called the “Unabomber” for his early propensity of targeting academics associated with universities — “un” for university — and people connected to the airline industry — “a” for airline. He used bombs, either mailed or placed around the nation, to kill or maim unsuspecting victims. He later broadened his horizons to include people within the timber or technology industries.

Many of the people who were involved in Kaczynski’s arrest and legal proceedings were prohibited from telling their stories while he awaited trial. But now that Kaczynski has confessed to his crimes and is in prison, they’re able to talk about their experiences.

Burns is a Lincoln native, lanky and laid-back. He wasn’t surprised in early February 1996 to get a phone call from Tom McDaniel, a regional agent with the FBI, because they had collaborated previously on cases.

“He called me one night and asked me if I could come into his office the next day because something big was going to go down in Lincoln,” Burns said. “He told me not to even tell anybody that I was coming into his office.”

McDaniel and a handful of other FBI agents asked Burns what he knew about Kaczynski, which wasn’t much. Burns knew where Kaczynski lived and had run into him in the forest a few times, but hadn’t talked to him much.

They wanted to know whether Kaczynski was at his home, a ramshackle cabin without running water or electricity.

Kaczynski’s whereabouts and activities would consume much of the next two months for Burns.

Tom McDaniel was “up to my neck in alligators” that February.

“We had the (anti-government) Freemen going on, and were we rotating in and out of Eastern Montana. And I was a member of the Missouri River Drug Task Force, getting ready to go to court on some drug cases, when I got a telephone call from the Unabomber task force in San Francisco,” McDaniel said.

“The guy said they had a great suspect in the Unabomber case, a guy in Lincoln, and my first thought was ‘oh, crap.’ Basically, when you have a lead like that, 99.9 percent of them just don’t develop. But sometimes, when you get a lead in a major case like the Unabomber, you have to drop everything and flesh it out to see if there’s any substance to it.”

He was told that the case needed absolute secrecy because of the fear that Kaczynski would flee if he got wind that anyone was onto him. But McDaniel knew Burns and brought him in on the case as soon as he learned the task force needed someone who knew the Lincoln area.

“I can’t say enough about Jerry,” McDaniel said. “He was an extremely important figure in the arrest of Kaczynski, and I’ve always had a lot of respect for him. There was no one else I would rather have had in on this.”

If Kaczynski was the Unabomber, the task force first had to learn as much as possible about him, including where and how he lived.

So McDaniel, Burns and another agent took snowmobiles to the top of Mount Baldy, then walked down the mountainside in thigh-deep snow, trying to sneak up on Kaczynski’s cabin. It took awhile to locate the small structure nestled among towering pines, but as they neared the cabin, McDaniel heard a squeaking sound, similar to wood-on-wood.

McDaniel later learned it was Kaczynski opening his door.

“The next time I heard that noise was the day we arrested him,” McDaniel said. “He later asked if we were up there on snowmobiles, and said he had seen the tracks and followed them to the top. He let us know it was an area that was closed to snowmobiles and we had violated the law.”

Burns knew he couldn’t even tell his boss, the head of the Lincoln Ranger District, about the potential bust going down, but said he had to tell his wife, Laura, since FBI agents started coming to his house at night to talk strategies.

“It was kind of hard to keep it from her, but nobody else in the Forest Service knew,” he said. “At that time, Ted was just a suspect.”

He recalls elaborate ruses set up by the federal agents to cover their activities. The FBI wanted to move agents into Lincoln, so it set up a man and woman as a husband/wife couple in a hotel room at the Sportsmen motel. They said they were journalists doing a story on the proposed Phelps Dodge gold mine.

“They said they were doing a human interest story on how the mine might impact people,” Burns said. “So they would ask about unusual people, and Ted would come up.”

They also were strategically housed near the bus depot to make sure Kaczynski didn’t leave town.

The FBI also put an agent in a cabin near Kaczynski’s to do surveillance. Kaczynski stayed put, not even leaving to get his mail, but it turned out that the agent was watching the wrong cabin, Burns said.

But the agent did have a good view to see whether Kaczynski was coming into town, he added.

The FBI also needed to get better radio communication in the valley and decided the Granite Butte lookout would be the best place.

“So we told the (Forest Service) tech that the FBI was doing a radio repeater survey and wanted to temporarily use the Granite Butte tower,” Burns said. “You can usually get there by snowmobile in about half an hour.”

But the FBI technicians from Sacramento hadn’t ever ridden snowmobiles and needed to haul about 500 pounds of equipment to the site. Burns said the trip took them four hours and once they got to the tower their equipment wouldn’t work.

“They got pretty stewed, and then on the way back one radio guy flew off his machine and lost it down a gully. It took us three days to get it out.”

Meanwhile, McDaniel had rented an office off Cedar Street in Helena for incoming FBI agents, saying he didn’t want anyone to notice increased activity at the bureau’s office on the second floor of the Arcade Building in downtown Helena.

As agents gathered evidence, more signs seemed to point to Kaczynski, and talk turned to how an arrest would go down.

“We wanted to make the arrest when he was on his bike, away from the cabin,” Burns said. “We knew he had firearms and access to firearms because of hunting, and if he was the Unabomber, he probably had bomb-making materials, or even a bomb in his cabin.”

Yet the FBI still didn’t have enough evidence for an arrest warrant.

Then, on the night of April 2, 1996, McDaniel called Burns. Apparently, a news crew had gotten wind that the FBI was searching for the Unabomber somewhere between Helena and Missoula. The news crew agreed to hold the story for 24 hours.

“He told me it was going down tomorrow, and to meet him at the Seven-Up Supper Club early in the morning,” Burns said.

That night and the next morning, SWAT teams, bomb units and FBI agents from throughout the nation flew into Missoula, Helena, Great Falls and even North Dakota and drove to the supper club in Lincoln.

They still didn’t have enough evidence for an arrest warrant, but Assistant U.S. Attorney Bernie Hubley and Attorney General Janet Reno made out the search warrant on April 2. The inch-thick document was read and digested overnight by U.S. District Court Judge Charles Lovell, who signed the search warrant the next morning.

April 3 was a Wednesday, a typical spring day in the Rockies, with snow still on the ground and a hint of it in the air. Burns and McDaniel met with FBI agents, including Max Noel, one of the lead Unabomber investigators, at 5:30 a.m. to devise a plan to get to Kaczynski. Burns said the California SWAT team wanted to sneak up on the cabin and pounce on Kaczynski when he came out, but the locals knew that wouldn’t work.

“They had this urban SWAT team, but we told them they can’t go covert. We weren’t going to be able to sneak up on him,” Burns said.

So a plan was hatched to outfit Burns, McDaniel and Noel as surveyors who would try to get Kaczynski outside to show them the boundary lines of his property.

“We were concerned that Ted was a recluse, and what if he didn’t open the door?” McDaniel said. “We decided that the next action Jerry and I would take was to get a chain saw and start cutting trees. We knew that would get him out.”

Meanwhile, about 50 FBI agents headed into the forest to surround the cabin, in case Kaczynski decided to flee into the woods.

Burns figured this might be a good time to tell his boss at the Lincoln Ranger District, Gilbert Zepeda, that something big was about to happen.

“I told him some things were going to pop on the forest here today, and that we were going to arrest the Unabomber,” Burns said. “He got a funny look on his face.”

Burns, McDaniel and Noel checked to make sure they didn’t have any radios that might squawk and give them away. Then they started the 200-yard hike to Kaczynski’s cabin.

“The plan was that Jerry and I would get our hands on him and take him down,” McDaniel said. “Max was our trigger man, if we needed that.”

The men started talking about mining surveys as they walked toward the cabin.

“At 50 yards, I started yelling to Ted,” Burns said. “We didn’t want him to think we were sneaking up on him.”

That’s when McDaniel heard the wood-on-wood scratching sound for the second time, and Kaczynski stuck his head out the door.

“I thought, holy cow,” McDaniel said. “This guy looks like he’s dead. His skin was dirty, he had this grey hair all over the place.”

As Burns pulled Kaczynski out by the wrist, McDaniel grabbed his other arm and bent it behind Kaczynski’s back in a hammer lock. The men fell to the ground.

“I asked Jerry to cuff him because I wasn’t going to let go,” McDaniel said. “Ted’s immediate reaction was to scream. I think we spooked him.”

The men walked a handcuffed Kaczynski to a nearby cabin to interview him, while other agents cautiously peered into the house.

“Over the radio, I heard them say, ‘It’s him. Everything is in here,’” Burns said.

“Everything” was later found to include a bomb, Kaczynski’s largest and most sophisticated, hidden under a bed. Kaczynski also had a loaded .25-caliber automatic pistol near where his hand was on the doorsill.

By late afternoon, the media had descended upon Lincoln and the FBI was ready to transport Kaczynski to Helena. Noel, Kaczynski, and a postal inspector piled into the back seat of Burns’ white Ford Bronco, and they began the hourlong trip, trailed by vehicles full of photographers, reporters and gawkers.

As they neared Birdseye, all but one or two of the media vehicles passed the Bronco. McDaniel theorized they were headed to the Lewis and Clark County jail to set up cameras for a picture of Kaczynski.

But a question arose in the back seat of the Bronco as to whether Kaczynski would ever be booked into the jail.

“This was a real donnybrook,” McDaniel said. “As soon as we got telephone reception, Max is on the phone with some high officials from the Justice Department. Somebody from back east was of the opinion that until we went through and found stuff in the cabin, we couldn’t hold him and had to let him go. We thought, ‘Are you nuts?’ ”

The agents ushered Kaczynski into the downtown Arcade Building. It was getting near dinner time, so McDaniel picked up some food for the group from the Rialto bar across the street. As the heated debate continued over what to do with Kaczynski, he and McDaniel made small talk.

“I asked him how much it would cost him to live for a year, and he said about $250 to $300,” McDaniel said. “He would talk about just about anything, except when we asked him about the Unabomber.”

By 11 p.m., the FBI decided they had enough evidence to tie Kaczynski to the Unabomber cases and incarcerated him at the county jail. He stayed there until June, when he was flown to Sacramento for trial. Kaczynski eventually acknowledged he was the Unabomber and is spending the rest of his life in a maximum security prison in Colorado.

Burns and McDaniel are retired now, but the former FBI and Forest Service agents call each other at least once a year on April 3 to wish one another a happy anniversary.

The men say they enjoyed the integral roles they played in arresting the Unabomber, but McDaniel noted that it wasn’t the most interesting or important case for him in his 21-year career with the FBI.

“It was really fun to be a part of that case, but there’s others I had with the bureau that were more satisfying,” McDaniel said.

And Burns almost wishes that Kaczynski would have gone to trial so that people wouldn’t romanticize the Unabomber as some kind of “hermit genius.”

“In reality, he’s a cold-blooded, cowardly killer who devastated three families,” Burns said. “Since it didn’t go to trial, a lot of that didn’t get out.”