Flagg Miller

The Audacious Ascetic

What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal About Al-Qa’ida

4. The Genie and the Bottle: on Authority and Revelation Through Audiotapes

5. Our Present Reality (waqi ‘Una Al-mu ‘asir)

6. Dangers and Hopes (makhatir W-amal)

7. Taking Gandhi to Jerusalem Through Oslo, Norway

8. Dawn Anthems (anashid Al-fajr)

9. I Have Scorned Those Who Rebuked Me

10. New Bases Near an Ancient House

11. An Intimate Conversation (jalasa)

12. A Pragmatic Base (al-qa ‘ Ida)

13. Listen, Plan, Carry Out “al-qa ‘ida

Appendix a: Top Thirty-five Speakers in Audiotape Collection

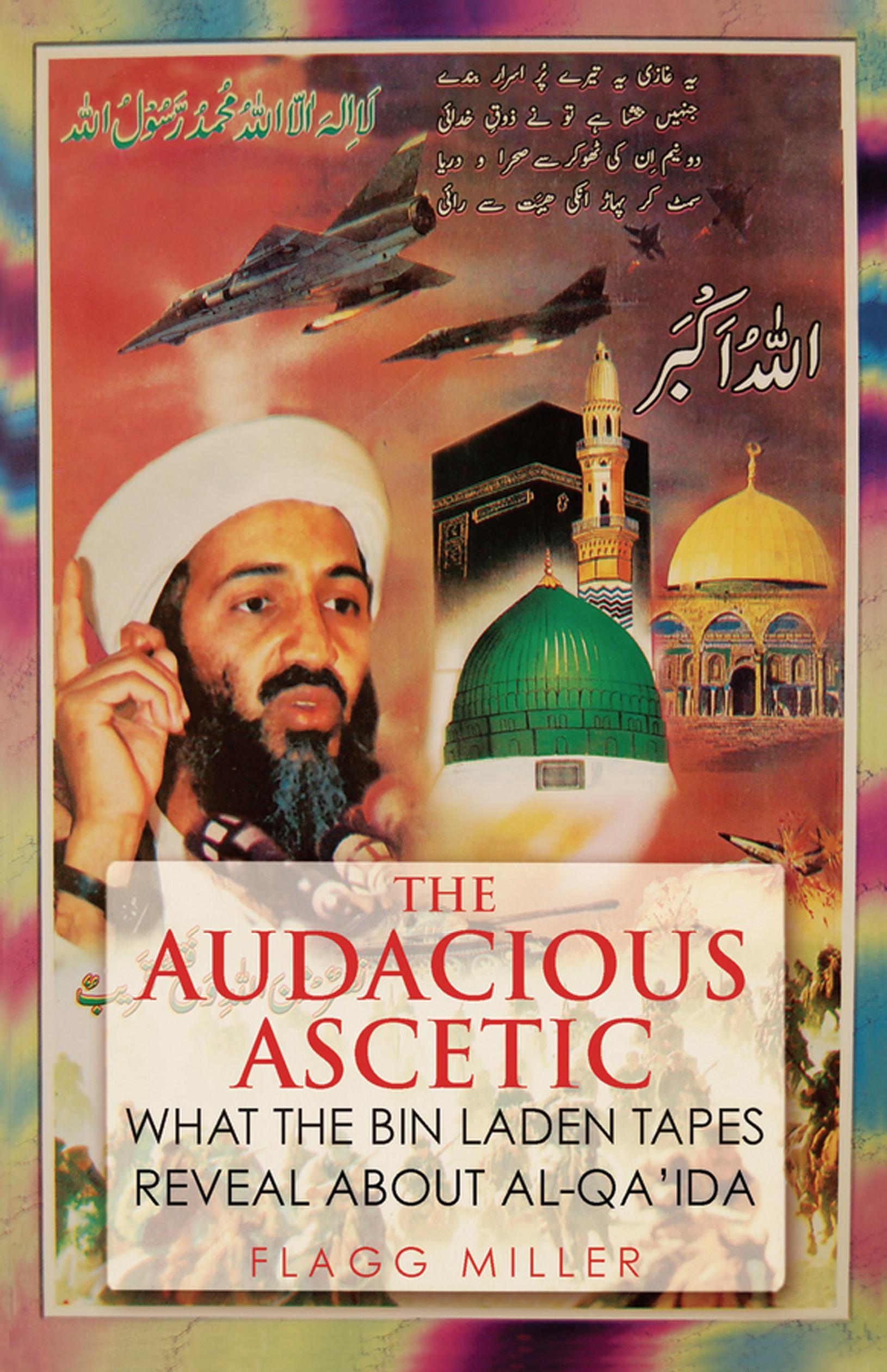

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

FLAGG MILLER

The Audacious Ascetic

What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal

about al-Qa[c] ida

OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

[Copyright]

OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford University Press is a department of the

University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective

of excellence in research, scholarship, and education

by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Copyright © Flagg Miller 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with

the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning

reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the

Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Miller, Flagg.

The Audacious Ascetic: What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal

about al-Qa’ida.

ISBN 978-0-19-026436-9

Acknowledgements

There are many to whom I owe thanks for the development of this book. Their patience and generosity kept me aloft when lonelier paths of research seemed interminable. For their support throughout, my wife and seven-year-old son deserve special mention. They have been steady companions in exploring the complexities of human experience everywhere.

My access to bin Laden’s former audiotape collection beginning in 2003 was made possible through collaboration with anthropologist David Edwards, director of the Williams College Afghan Media Project. I am forever indebted to his confidence in me and to Williams College for facilitating my early archival and research efforts. I conducted my first stint of fieldwork and research for the book through a grant from the American Institute of Yemeni Studies in 2005. The following year, gratefully employed at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, I spent a semester developing chapters one, nine and twelve as a fellow at the university’s Institute for Research in the Humanities. In 2007, I had moved to the University of California, Davis where I continued work with a new assembly of colleagues. I am especially grateful to former dean, Jessie Ann Owens, and my department chairs for allotting me the time and resources necessary to complete my work. A grant from the Hellman Foundation supplied rare funding for an Arabic research and translation assistant, Nour-Eddine Mouktabis, without whose labors my archival efforts would have been far less thorough. UCD staff members proved as adept in addressing my professional anxieties as they were convivial. They include members of the university’s news and media relations team, Karen Nikos and Claudia Morain.

The book’s organization, thesis and relevance would have been more modest were it not for invaluable support from beyond UC Davis. In 2009—10 I joined fellows at the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, D.C. for a year of earnest discussion about pressing issues at home and abroad. Chapters eight and thirteen are indebted to my interactions while at the center. Two subsequent years of fellowship allowed me to refine the book’s contributions. They were secured through support from the American Council of Learned Societies’ Charles A. Ryskamp Fellowship in 2010—11, and through a University of California President’s Faculty Research in the Humanities Fellowship in 2013—14. During this period, I had the privilege of submitting my research for consideration to a range of audiences both within academia and beyond. Host institutions included, roughly in order, the Modern Orient Center (ZMO) in Berlin, the University of Michigan’s Near Eastern Studies department as well as its Linguistic Anthropology Group and Islamic Studies Program, Oxford University, Emory University’s departments of anthropology and religion, George Washington University’s Institute for Middle Eastern Studies, Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, Qatar University, New York University, the Foreign Service Institute (Arlington, VA), Cornell University’s Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, the University of California, Davis’s anthropology department and militarization research cluster, Wesleyan College’s Middle East Studies department, Dartmouth College, the University of Chicago’s Middle East History and Theory Graduate Workshop, the National Defense University, Stanford University, Florida State University’s department of religion, Harvard University, and most recently Yale University’s anthropology department and Council on Middle East Studies.

Special thanks are due to a range of interviewees, readers, co-translators and facilitators. Paramount among them are Hurst’s two anonymous readers as well as Michael Dwyer, without whose perspective and assiduous labor none of this would have been possible. To others’ enormous generosity I can only gesture: ‘Umar bin Laden, Abdullah Anis, Alexander Knysh, Zaina Bin Laden, Valerie Billing, Jean Sasson, Deputy Commissioner John Miller, Massa, Joe Brinley, Deborah Grosvenor, Katherine Zimmerman, Friedhelm Hoffman, Neil MacFarquhar, Henry Schuster, Esther Whitfield, Alex Strick van Linschoten, the Institute of Education (London), faculty colleagues in UC Davis’s religious studies department and Middle East/South Asia program, and research assistants Ahmed Mahmoud, Rabeah Hammood, Mohamed Amin, and Fatna Ballouchi.

Audio-recordings used for all translated excerpts featured at the start of each chapter can be heard on the website www.audaciousascetic.com. I am grateful to Charlie Turner and his colleagues at UC Davis’s Academic Technology Services for their assistance with website development and the time-coded synchronization of audio material with translations.

Introduction

15 April 1998. Lahej governorate of southern Yemen.Village feast celebrating the Festival of the Sacrifice that concludes the holy month of Ramadan. Meal conversation with ‘Abdalla, leader of an al-Qa‘ida front called the World Islamic Organization.[1]

‘Abdalla: Hey dog.

Me: Who’s the dog?

‘Abdalla: You. You’re the dog.

Me: I am not a dog.

‘Abdalla: My name is ‘Abdalla. In Islam, the name ‘Abdalla is the most revered of names. God created mankind to obey and serve him under the banner: ‘There is no God but God alone and Muhammad is His Messenger.” The British, on the other hand: We used to call them Red Dogs since their faces were red.

Me: Well I’m not British and my face is not red.

‘Abdalla: You are not welcome here. America hatches the greatest plots in the world. No power is more corrupt and sinister. No one wants you in our Muslim lands, so you would best head back to where you came from.

Me: That’s not true. Many people have welcomed me here. They know perfectly well that I’m conducting research that will benefit the region.

By most measures, the outdoor feast for hundreds of villagers was an occasion for celebration. An hour later, tribal dancing broke out in a nearby market square. Delegations of dancers entered the square brandishing curved daggers and twirling in unison as they chanted poems. ‘Abdalla’s darker mood was not his alone. One disgruntled elder, fresh back from Afghanistan, broke out a Klashnikov and swung it wildly at the first row of dancers. Before south Yemen’s independence from the British in 1967, his own clan had customary rights to lead the parade. They were religious sayyids, men who could trace genealogical descent to the Prophet Muhammad’s own Quraish tribe. Three decades later, a Soviet-backed communist regime having killed or exiled religious elites and banned status hierarchies, everything had changed. To the relief of terrified parade goers, the assailant was coaxed away from pulling the trigger. He was tackled by whomever could lend a hand.

Such unnerving encounters were fortunately rare for me during my graduate fieldwork in Yemen. Pursuing a degree in linguistic anthropology, I had chosen to focus my research on changing traditions of tribal poetry. The topic was welcomed by Yemenis across the board. That afternoon, while sitting with an assortment of tribal shaikhs and guests, I had discovered that ‘Abdalla had more to say. Although the Cold War had ended, he predicted that Moscow was on the verge of a comeback. Within one year Russian forces would re-invade Yemen, beginning in Aden and continuing their advance across the Arab world. While America and “the Arabs” were enemies today, he insisted, they would join forces against this global front, struggling side by side in a third world war that would end in God’s final Day of Judgment. ‘Abdalla smirked at me as my Yemeni colleagues in the room gave him a cold shoulder. “Perhaps we’ll win you over one of these days.”

The events of 11 September 2001 seemed adequate proof of ‘Abdalla’s hair-brained predictions. Far from uniting Americans and Arabs, the attacks and their aftermath created even greater distrust. In the United States, Arabs, Muslims, and many people held to resemble them, experienced an increase in hate crimes that, in some cases, exceeded 1700 per cent.[2] Ten years later, a Pew research poll reported that more Americans held an unfavorable opinion of Islam (35 per cent) than those who held a favorable view (30 per cent), in contrast with findings just five years earlier.[3] In the Arab world, meanwhile, the ensuing militarization of America’s foreign policy yielded even more dramatic trends in hostility. Already suffering from public anger over the crippling effects of U.S.-led sanctions in Iraq, and the unprecedented scale of Israeli settlement expansion, America’s reputation garnered some of the strongest criticism from our long-term allies. A poll in 2004 showed a dramatic decline in favorable opinions of the United States among Egyptians (95% unfavorable versus 75% in 2002), Jordanians (78% versus 61%), Moroccans (88% versus 61%), and Saudi Arabians (94% versus 87%.)[4]

Still, if public opinion defied ‘Abdalla’s predictions, the decades of the 1990s and 2000s opened an epoch of bolstered military and economic ties between the United States and the Arab world that brought them even closer together. Beginning with the Gulf War of 1990—91, American-led coalition troops fought with Saudis, Egyptians, Syrians, Moroccans, Kuwaitis, Omanis, as well as some twenty-five other nations to drive Saddam Hussein’s army out of Kuwait. In the years that followed, Qatar hosted the growth of America’s two largest military bases in the region. Its Al-Udeid air base would become headquarters for the United States Central Command, the chief hub for managing American military operations in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. In the two years after 11 September, America’s military budget increased by 73 per cent, totaling some $417.4 billion, half of the total U.S. discretionary budget.[5] Wars launched in Afghanistan and Iraq during this period would not only add further billions to the ledger. They would also ensure the centrality of these regions to Americans’ sense of place and identity in a twenty-first-century world marked by heightened security concerns. Record-breaking arms sales to Arab allies, some of which topped $919 million by 2013, deepened and complicated a long-term American-Arab relationship.

Amidst the many currents of political and economic change that defined America’s role in the post-Cold War period, Osama bin Laden came to acquire extraordinary power. Born in Saudi Arabia to a family made fabulously rich by construction and commercial ventures, he had already risen to celebrity by the time the first Gulf War occurred, as a result of his avid support for Arab freedom fighters struggling to liberate Soviet-occupied Afghanistan. To be sure, by most accounts, he faced decided setbacks through the 1990s. Opposing King ‘Abdulla’s decision to rely on American coalition forces to help drive Saddam’s forces from Kuwait, he fell out of favor with the Saudis and their allies. So persistent were his demands on the Saudi monarchy that by 1994, he was stripped of his citizenship and family inheritance. A growing pariah across the Arab world for inciting Islamic resistance to authoritarian Sunni regimes elsewhere, he appears to have lost the vast remainder of his fortune through poor investments. In 1996, he became stateless after being kicked out of the Sudan. Curiously, however, his political and financial leverage not only survived these misfortunes but actually grew stronger. Described by the American Central Intelligence Agency in 1995 as the “Ford Foundation of Sunni Islamic terrorism,” his power seemed to transcend the surveillance and security mechanisms of the world’s wealthiest states.[6] His capacity to threaten Western interests, especially American, tapped shadowy financial networks whose resilience puzzled the most acute observers. Even while being forced to retreat into Afghanistan’s most rugged highlands, he was reported to have maintained steady access to tremendous wealth supplied to him by Arab political elites, private donors, charity organizations, foreign banks, shell companies, and a decentralized network of money brokers. With the attacks of 9/11, the full scope of bin Laden’s exceptional capabilities were apparent to world audiences like never before. In the words of New York Times journalist Thomas Friedman, he was a “super-empowered angry man,” one of a new class of individuals who took advantage of globalization’s market, transportation, and communication networks and used them to challenge traditional state arrangements.[7] So extensive was his influence that top American officials viewed Iraq, a country without a notable al-Qa‘ida presence prior to 2003, as dangerously subject to his sway. While Americans prepared for war, links between al-Qa‘ida and Iraq became “accurate and not debatable.”[8]

This book explores bin Laden’s rise as both an ascetic adversary of Western globalization and an important rationale for expanding America’s transnational security commitments within Arab and Islamic worlds especially. I focus, in particular, on the history of the concept of al-Qa‘ida. Contrary to predictions of its elimination after bin Laden’s death or the routing of what was called “al-Qa‘ida Central” from Afghanistan in the decade following 9/11, al-Qa‘ida remains very much in the news. Given conflicts during 2014 in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Yemen, we might speak of the organization’s “rejuvenation.” To do so, however, requires assuming that al-Qa‘ida’s apex was under bin Laden and that splinter groups and affiliates arising after 9/11 were successfully forced into retreat by virtue of being prevented from attacking the United States on its own soil, with the exception of a few isolated cases. I argue that the concept of al-Qa‘ida has a longer and messier history. My encounter with Yemeni operative ‘Abdalla in 1998 provides a snapshot of how this history would unfold. Not only were Arabs and Muslims fast in becoming al-Qa‘ida’s primary victims, but bin Laden and his focus on the American “far enemy” would be comparatively marginal.

Al-Qa‘ida’s organization and ideology have been vigorous subjects of debate. According to political scientist Richard Jackson, scholars in the West have typically held four perspectives.[9] First, there was the idea that al-Qa‘ida is a hierarchical organization defined by a core group of top leaders, a secondary cadre of loyal operatives, and a wider coalition of supporters and ties with other groups.[10] Second, came the argument that al-Qa‘ida’s hierarchy changes according to circumstances and reflects the priorities of a diffuse and adaptive web of both state and non-state actors.[11] From this perspective, al-Qa‘ida was a “network of networks” and often worked through self-radicalized “lone wolves.” A third approach, especially for those with an eye for political history, was that al-Qa‘ida was one fairly short-lived branch of a much broader international jihadist movement.[12] Finally, came the argument that al-Qa‘ida was more an ideological framework or source of inspiration that drew upon pan-Islamist vocabularies while trying to steer recruits toward specific conflict settings.[13]

I venture in new directions by exploring the ways in which al-Qa‘ida works as discourse. Rather than unpacking al-Qa‘ida’s organizational structure, network capacity, or ideology, I focus instead on how its leaders, supporters, and even detractors have talked about al-qa‘ida in its Arabic sense as a “base” or “rule.” In the Muslim world, such foundations (qawa‘id in the plural) are invoked by speakers in different contexts of reasoning and argumentation. In discussions of Islamic law, for example, jurists invoke these rules through catchy legal aphorisms: “Acts are judged by their intention” (al-umuru bi-maqasidha); “No harm shall be inflected or reciprocated in Islam” (la darar wa la dirar); “‘The law should work to alleviate people’s hardships” (al-mashaqqa tajlibu al-taysir); and so forth. In discussions of theology, a basic qa‘ida states that “Whatever exists can be seen” (kullu mawjudinyura), a rule that emphasizes empirical observation before metaphysics. In discussions of Arabic grammar, subjects come before predicates except in certain cases (taqaddum al-mubtada’ ‘ala al-khabar). Since the eighth century Muslims had compiled vast compendia of such rule books (qawa‘id) that guided the faithful in aligning themselves with divine will. To a great extent, these tomes helped to bolster the authority of state establishments. Al-qa ‘ ida discourse could focus very much on proper orders of power and knowledge: know the rule and its norms and all will be well. I’ll suggest, in fact, that this rendition of al-qa‘ ida has made the concept far more conducive to furthering state interests than is typically thought plausible. I will also focus on how Muslim militants and reformers have disagreed with one another over what qawa‘id are and how they are to be applied.

I draw my insights primarily from a never before-studied collection of over one thousand five-hundred audio tapes that were formerly deposited in bin Laden’s own residence in Kandahar, Afghanistan. The collection served as an audio library for those who gathered under bin Laden’s roof between 1997 and 2001, during the years of al-Qa‘ida’s most coherent organizational momentum. Some of the speakers are al-Qa‘ida’s best-known militants, including twenty-four tapes of bin Laden himself, as well as tapes by ‘Abdalla ‘Azzam, Abu Mus’ab Al-Suri, and Abu al-Walid Al-Misri, among others. Most of the tapes, however, contain speeches by figures known more for sticking to their books than their guns (see appendix A). These individuals were never members of al-Qa‘ida, although as specialists in Islamic law, theology, ritual practice, and history they were held in great esteem by militants. Saudis rank foremost among them, followed by Egyptians, Peninsular Arabs (especially from Yemen, Kuwait, and Bahrain), Afghanis, Palestinians, Syrians, and Sudanese. Almost all speakers are Sunni Muslims, a branch representing the vast majority of Muslims in the world, although their traditions of legal interpretation are many. Some are established state clerics such as the former Chief Jurist (mufti) of Saudi Arabia, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Baz, the leader of Yemen’s largest Islamist party, ‘Abd al-Majid Al-Zindani, and Kuwait’s unabashedly pro-West entrepreneur and intellectual Tariq Al-Suwaidan. The latter figure represents a breadth of thought contained on the tapes, and the ways militants found certain figures compelling—in Al-Suwaidan’s case, his lectures on such leadership skills as “honor,” painted in monumental golden letters forming an ocean ship on one cassette jacket— despite overt differences in political affiliation.

The tapes were originally acquired by the Cable News Network (hereafter CNN) in early 2002, a few months after al-Qa‘ida and the Taliban had been routed from the city by American Special Forces, alongside Afghan troops and tribal leaders. CNN informed U.S. intelligence officials of the existence of this material. While they appear to have reviewed the tapes, they declined stewardship of the collection. Inundated after the fall of the Taliban with printed documents, computer hard drives, video cassettes, and other materials of more immediate intelligence value, officials advised CNN to pass the collection on to an academic community. A year later CNN arranged for the cassettes to be shipped to Williams College with the understanding that they would be made available for researchers.[14] In 2006, the tapes were moved to Yale University where they have been converted into digital format and can now be heard.

Thanks to an anthropologist colleague at Williams, I first got involved in conducting research on the tapes when they arrived from CNN’s Islamabad office. Since no inventory or description of the archive existed at the time, my main task over the next several years was to develop a report that could explain the significance of the collection for further studies of al-Qa‘ida and bin Laden’s role in particular. My first publication on the collection, released in 2008 in the Journal of Language and Communication, was accompanied by an article in the New York Times, and thereafter by media attention worldwide. At the outset of my article, I expressed surprise that after reviewing a great many of the tapes, some of which date to as late as November 2001, I had yet to find a single instance in which al-Qa‘ida was spoken about as bin Laden’s worldwide militant organization. Years later, after studying the collection exhaustively, I can update my findings: one tape, a recording produced in late October 2000 featuring a wedding celebration in honor of one of bin Laden’s bodyguards, begins with an advertisement by “al-Qa‘ida’s publicity committee” (al-lajnat al-i‘laniyya li-l-qa‘ida). Chapter fourteen is devoted to my analysis of this tape. It is preceded by a chapter about another recording that, while not mentioning bin Laden or any organization associated with him, features a cartridge label whose title, “Listen— Plan—Carry Out ‘al-Qa‘ida,’” (Isma‘—Dabbir—I‘mal ‘al-Qa‘ida’) suggests provenance from around 1999—2001.

I consider the audiotape collection’s near complete silence on al-Qa‘ida’s association with bin Laden’s global terrorist network in the years before 9/11 to be an opportunity rather than a loss. When I first began reviewing the tapes, I listened carefully for bin Laden’s voice and any mention of al-Qa‘ida’s objectives by those most closely associated with the organization. What I heard instead a was range of lectures and discussions by over two hundred different speakers, most of whom were known to be established legal scholars with scant regard for bin Laden’s style of reasoning. I also heard a vast range of amateur and extemporaneous recordings that were not designed for broad circulation: taxi cab conversations, chats over breakfast in make-shift kitchens, sounds of live battles as militants communicated on two-way radio transceivers, wedding ceremonies, celebrations before and after combat missions, poetry competitions, trivia games, lectures in training camp classrooms,

THE AUDACIOUS ASCETIC interviews with leaders, telephone calls, studio-produced dramas of mock battles and their aftermath, and Islamic anthems sung late into the night. Much of this material was quite familiar to me and brought back memories of conversations and songs that I had come across while working with close friends in Yemen, the Arab Gulf, and the United States. I also heard ordinary views co-opted by heinous extremism. To help make sense of such shifts, I listened to the tapes with dozens of native Arabic speakers in the Middle East and United States, some of whom were ex-fighters themselves who had known bin Laden intimately. In time, I discovered not just how different bin Laden’s world had been from that familiar to most of us. I learned much about what drew these worlds together.

A conventional view of al-Qa‘ida maintains that the organization’s ultimate goals are to drive America out of the Muslim world, to destroy Israel, and to create a jihadist caliphate larger than the Ottoman empire at its height.[15] Many statements by top al-Qa‘ida leaders support just this formula. Questions arise, however, about how well these long-term objectives translate into the real concerns of people who might be inclined to take these leaders seriously. While militant ambitions to establish a caliphate are readily trotted out for non-Muslim audiences, speakers exercise far more restraint when lobbying for the notion among Muslim activists, as I discuss with respect to Palestinian militant ‘Abdalla ‘Azzam later in the book.[16] For ‘Azzam, struggling toward a pan-Islamic caliphate should take a back seat to more immediate and everyday objectives, among them seeking justice in one’s own homeland. Muslims must cultivate a far broader repertoire of strategies, tactics, and methods for ensuring that the good fight isn’t lost or perverted before it even begins. In this respect, al-Qa‘ida theoreticians must position themselves within in-house debates about founding principles and practices. What makes a good Muslim? What is the nature of sin? How can the righteous remain vigilant against injustice? How much effort should one devote to seeking knowledge of other faiths and cultures? Which research topics are worth pursuing? What was the path of the pious forebears? What are the qualities of a good leader? How can a believer survive in the modern world while abiding by the Prophet Muhammad’s example to his community? Such questions yield no easy answers. Different points of view and public disputation constitute the very terrain on which speakers engage with each other in attempts to find common cause. By linking

these debates to changing discourse about al-Qa‘ida’s past, present, and future, I move beyond the tendency to lump Arab-Afghan radicals together under a single overarching narrative.

My greatest challenge in writing this book has been to find ways to accommodate the very thing that has come to define al-Qa‘ida after roughly two decades of its making, namely, its leaders’ adherence to a distinctly anti-American platform. Bin Laden was, of course, one of the most vocal and assiduous proponents of this message. Especially from 1996 onward, he branded himself as an ascetic warrior dedicated to a global Islamic struggle against the United States. He was not alone, however. Much of his discourse echoed sentiments among Saudi reformers mobilized during the 1980s and 1990s by a religious movement called “the Islamic Awakening” (al-sahwa al-islamiyya). Although the Saudi state had jailed, exiled, or co-opted the movement’s most critical members by 1994, bin Laden’s notoriety in the West continued to provide leverage to Saudi activists as they continued to jockey on various fronts. His calling card proved felicitous for similar reasons in other, largely Muslim-majority, countries whose state leaders worked to maintain legitimacy even as they defied popular resentment against deepened economic, political, and military collaboration with the United States. These countries included Afghanistan under a nascent Taliban leadership as well as Pakistan, India, Uzbekistan, Yemen, Qatar, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Malaysia, and others. Bin Laden’s message played best among global television and print audiences. Given the United States’ increasing pressure on an international community to stiffen sanctions against Iraq, his outbursts provided good copy as American, British, and Arab journalists sought to communicate the concerns of an increasingly angry Arab public. Beyond mass media scheduling, however, Western officials found purchase in a consistent message about bin Laden’s global anti-American terrorist organization. As I show in later chapters, foremost among them were American federal prosecutors, intelligence analysts, law enforcement agents, foreign policy makers, and scholars who faced a new era of security challenges.

Bin Laden’s exceptional role in global affairs was not immediately apparent to Muslim audiences familiar with his career. According to Egyptian American sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, when interviewed for Al-Jazeera’s first documentary on bin Laden in 1999:

With regards to bin Ladin, he is the exception that proves the rule (al-istithna ’ alladhi yu ’ akkid al-qa ‘ ida). He was the youngest child, and since his family, despite its considerable wealth, is from the Hadramawt [in Yemen] and thus still considered marginal in Saudi Arabia, he was not fully accepted in Saudi society. Such marginalization sometimes explains a desire to rebel against the system. If one is unable to do this on the inside, one does it from the outside.[17]

Bin Laden’s appeal to Arab audiences lay in what he shared with many a rebel. His rage against “the system” stemmed from a generational conflict between the young and the old, discrimination against ethnic minorities, entrenched status hierarchies, inequalities in citizenship, and a yearning for justice that one’s own community could not deliver. Bin Laden’s life story reminded audiences that money alone could never solve these problems. A well-stocked treasury could in fact make things worse. This was a universal message that invited rebellion on many fronts, beginning with those at one’s doorstep. This book attends both to the religious mooring of such struggles and to how this foundation was overturned.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

The idea of a “base” (qa‘ida) set against outside forces of perceived economic and material corruption proves central to my argument. Accordingly, I devote the first three chapters to the ways Muslim discourses of self-abnegation or asceticism (zuhd) informed bin Laden’s early life and views of his leadership. As throughout the book, each chapter begins with a translated excerpt from a selected audio recording in bin Laden’s former collection. The opening excerpt in chapter one is taken from a speech bin Laden delivered in Tora Bora, Afghanistan in the summer of 1996. Since the speech was his first to be translated into English for Western audiences, it represents a key moment in perceptions of his vitriol. Dramatized with images of ruthless desert warriors, the oration came to be known as a “Declaration of War against Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries.” Much of the chapter provides an introduction to bin Laden’s relevance among political reformers and opposition leaders in Saudi Arabia, whose “two holy mosques” of Mecca and Madina provided an anchor for his speech. I attend closely to audio recorded themes of zuhd left out of English translations as well as to complementary lectures on the topic elsewhere in the tape collection. While zuhd places value on leaving one’s wealth and belongings aside in preparation for the afterlife, more important is self-discipline in this life, especially when in the presence of wealth close to home. Chapter two probes further into the productive relationship between wealth and self-abnegation through details of bin Laden’s childhood, adolescence, and early years in the Islamic jihad against Soviet occupiers in Afghanistan. Entitled “Heart Pains,” the chapter begins with an audio recording from 2000 in which, after a host of statistics detailing the proliferation of American military bases and personnel across the Middle East and North Africa, bin Laden levies a charge of fraud against the Saudi monarchy. Bin Laden’s animosity toward an amalgamated “Crusader-Jewish occupation” needs contextualization. In 1979, the first year of bin Laden’s involvement with the Arab-Afghan struggle, the Saudi state found ample reason to support a firebrand whose ascetic battle against an ostensible hoard of non-Muslim others also contained seeds for his own later isolation. Bin Laden’s emphasis on the works of eighteenth-century Saudi reformer Muhammad Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, draftsman for the state’s own ideological charter, for example, as well as on Arabian tribal virtues played to the state’s hand. All the more so when leveraged by security officials against political reform and opposition efforts from both Sunnis and Shi‘as.

Chapter three begins with the earliest of bin Laden’s speeches in the collection and sets the tone for the book’s subsequent chronological progression. Recorded in 1988, the featured speech addresses Saudi audiences’ interests in the Arab-Afghan war effort. I focus on the first of bin Laden’s training camps in Afghanistan and consider how his leadership and public perceptions of his work were tailored to narratives about this site. As a prelude to later chapters, I discuss relations between Arab and Afghan leaders who worked with bin Laden at the time and consider their various intellectual and political orientations. Before further unpacking the significance of bin Laden’s original bases and their misconstrual by Western interpreters, I devote chapter four to the medium of the audio cassette. No study of al-Qa‘ida is sufficient, I argue, without a serious consideration of media technologies and their political deployment. In contrast with clean genealogies of al-Qa‘ida’s founding theorists and their profiles, formative events and chronologies, the work of mediating Islamic jihad for specific audiences and occasions makes “bases,” “rules,” and their sponsors answerable to social projects whose histories and entailments are far more polyglot than is typically assumed. The chapter begins with an excerpted recording by a Muslim genie (jinni) who employs an audio recorder to win support for controversial views among Arab-Afghans. Using the genie’s reflections on asceticism to inquire about the nature of the archival project underway in bin Laden’s Kandahar residence between 1997 and 2001, I lay the groundwork for subsequent critical assessments of al-Qa‘ida studies that have relied primarily on written, printed, and electronic records.

The next three chapters feature excerpts from public speeches made by bin Laden in Saudi Arabia and Yemen between 1989 and 1993. I focus on the ways audio recorded copies of bin Laden’s speeches help situate his discourse amidst Islamic reform movements, whose relation to state authorities could not always be openly confrontational. Chapter five expands on earlier discussions of al-Qa‘ida’s origins by considering a lecture that identifies Islam’s principal enemies as Shi’a and Arab communists stretching from Afghanistan to the Arabian Peninsula. By comparing key themes in the speech with evidence from American federal prosecutors, journalists, and early al-Qa‘ida analysts, I contest the common view that al-Qa‘ida was founded by bin Laden in 1988 with the aim of preparing recruits for post-Soviet combat against non-Muslim enemies and, within a few years, the United States especially. I suggest, instead, that the organization emerged from plans to establish the Al-Faruq training camp in Afghanistan under Ayman Al-Zawahiri and Egyptian commanders who were dedicated primarily to supporting insurgencies against authoritarian regimes within the Muslim world itself. Chapter six, featuring a speech most likely delivered in Yemen, explores how bin Laden harnessed this focus on the near enemy by using doctrinal vocabularies familiar to his chief audiences in the region. While criticism of the Saudi regime remains acute, bin Laden’s location outside the kingdom licenses a more radical denunciation of Muslim “hypocrites” across the world along with a call to take up arms against their leaders. Chapter seven explores the ways in which bin Laden was forced to mollify his critique of the Saudis in light of internal divisions within the Saudi Awakening movement. The price for such collaboration, I suggest, is a far more strident stance against the United States and its policies toward Israel and the Palestinians. Even this salvo requires muffling, however, given Saudi and Gulf Arab state sensitivities.

I explore the implications of bin Laden’s recourse to the example of Mohatma Gandhi as he tried to navigate these currents.

Chapter eight fleshes out tensions introduced in previous chapters between bin Laden’s gestures toward more ecumenical forms of modern Islamic activism and his growing Arab-centric focus on the American enemy. Featuring a jocular, and at times irreverent, conversation between anonymous Arab militants as they prepare breakfast in an Afghan kitchen, the chapter draws attention to the ways bin Laden’s own militant version of asceticism contrasts with its more pliant and accommodating counterpart among kitchen participants. With notes on the tape drawn from my interviews with bin Laden’s son, ‘Umar, I explore the tape’s significance in mediating ideological differences that emerged in the early 1990s between a first generation of Arab-Afghans whose primary goal had been to defeat the Soviets and a second generation of younger, less experienced militants of uprooted transnational backgrounds who looked to broader horizons of militant engagement.

Chapters nine, ten, and eleven explore the ways in which bin Laden’s rising notoriety among global television networks informed his speeches and shaped his role among militants from 1996—8. The first of these chapters begins with a longer excerpt from bin Laden’s 1996 “Declaration of War” introduced in chapter one. Revisiting common assumptions, I show how bin Laden’s unambiguous designation of the United States as Islam’s prime enemy is couched in a tradition of in-house dissent against corrupt Muslim rulership. The last third of the speech, a section whose fourteen poems are delivered with stirring oratory on audio tape, though they are expurgated from most English translations, lays out the uncompromising tenor of such dissent. The chapter focuses on how bin Laden’s message was downplayed or altered by Western political activists, intelligence analysts, and journalists in ways that found broader uptake by militants themselves. Chapter ten examines the first of bin Laden’s recorded speeches from Kandahar, Afghanistan where he moved in March 1998 under the watchful eye of the Taliban. Evoking the theme of an “ancient house” in Mecca besieged by sixthcentury Abyssinian Christians, bin Laden conjures up an image of pan-Islamic unity. The image, I argue, reflects modeling by CNN following its interview with him several weeks earlier. Most of the chapter explores the implications of bin Laden’s much advertised anti-American ideology for Arab-Afghans and Taliban leaders. Chapter eleven delves further into the ways bin Laden’s growing status as a media sensation was contextualized by ordinary Arab-Afghan volunteers. It draws upon a recording featuring what is likely former Yemeni Guantanamo detainee, Salim Hamdan, as he cross-examines ABC Nightline news correspondents John Miller and Tarik Hamdi during their trip to one of bin Laden’s camps in May 1998. The conversation provides insight into the mechanisms by which early depictions of bin Laden and his worldwide terrorist organization, drafted largely by American federal prosecutors, found their way back to bin Laden and his associates as they crafted talking points for their cause.

The final three chapters explore the ways al-Qa‘ida’s top commanders, advisors, and media consultants situated bin Laden’s “far enemy” discourse, now amplified by global news coverage especially in the United States, in relation to the constraints of regionalized struggles and Islamic law in particular. Chapter twelve examines a lecture by Egyptian militant Mustafa Hamid (aka Abu al-Walid Al-Masri) on the tactics and virtues of establishing a militant “base” (qa ‘ ida). Recorded in October 1998 at a Kandahar training camp, the tape reveals Hamid expressing doubts about the future of the Arab-Afghan struggle and urging recruits to return home and canvass the merits of applying Islamic law among broader audiences. I explore Hamid’s discourse on al-qa‘ida in relation to those of two other prominent Muslim jurists in the tape collection in order to show how he deploys the concept toward militancy. Chapter thirteen considers a more theological rendering of the qa‘ ida by the collection’s top featured speaker, Syrian jurist ‘Abd al-Rahim Al-Tahhan. Focusing on a tape labeled “Listen, Plan, and Carry Out ‘al-Qa‘ida’,” I attend to the ways Al-Tahhan’s discourse on Islamic law and creed lends itself to an existential reading that militants found useful, among them Saudi audiotape producers who re-branded his lectures in support of bin Laden’s extremism during the late 1990s. Chapter fourteen examines the only other tape in the collection that is explicitly marketed under the “al-Qa‘ida” label. The recording features a wedding celebration for one of bin Laden’s bodyguards in October 2000. As I show, bin Laden and al-Qa‘ida’s increasingly controversial status among would-be followers after the 1998 United States Embassy bombings in East Africa, the victims of which were mostly Muslim, compelled them to try to reach broader audiences through innovative and more cosmopolitan renditions of an ascetic Arab ideal.

In an epilogue, I review the lessons of the book for understanding and studying al-Qa‘ida. Greater attention to the diversity of al-Qa‘ida’s primary enemies and targets is crucial to developing effective trans-national collaboration in fighting terrorism, especially given al-Qa‘ida’s horrific legacy among Muslims themselves.

1. The Message (al-risala)[18]

(August 1996 speech by Osama bin Laden.The Hindu Kush mountains, Afghanistan. Opening remarks, cassette no. 506.)

Praise be to God. We show Him gratitude, seek His help and ask for His pardon. We take refuge in God from the evils within us and our wrongful deeds. Who ever is guided by God will not be misled, and who ever is misled will never be guided. I bear witness that there is no god except God (Allah), Who has no associates, and I bear witness that Muhammad is His Slave and Messenger.

“O, you who believe! Be careful of your duty to God with the proper care which is due to Him, and do not die until you have rendered due submission.”[19] “O mankind! Be careful of your duty to your Lord, who created you from a single being and created its mate of the same kind and spread from these two a multitude of men and women. Be careful of your duty to God, by whom you demand your rights of one another and attend to the ties of kinship; surely God ever watches over you.”[20] “O you who believe! Be careful of your duty to God and speak the right word; He will make your conduct virtuous and will forgive you your faults; and whoever obeys God and His Messenger, he indeed achieves a mighty success.”[21]

Praise be to God, it has been reported “I desire nothing but reform so far as I am able. My success in this task depends entirely on the help of God; in Him do I trust and to Him do I turn for everything.”[22] Praise be to God, it has been reported “You are the best of the nations brought forth for mankind; you command what is right, forbid what is wrong and believe in God.”[23]

God’s blessing and salutations on His Slave and Messenger who said “If people see the oppressor and fail to restrain him with their hand, they draw close to an all encompassing punishment from God,” as has been reported by Abu Da‘ud Al-Tirmidhi.

Now then:

It should not be hidden from you that the people of Islam have suffered from injustice, oppression, and aggression by the Judeo-Christian alliance and their collaborators, to the extent that Muslims’ blood became the cheapest and their wealth and natural resources loot in the hands of their enemies. Their blood was spilled in Palestine and Iraq. The horrifying pictures of the massacre of Qana, in Lebanon are still fresh in our minds. The same is true for the massacres in Tajikistan, Burma, Kashmir, Assam, the Philippines, Fatani, Ogadin, Somalia, Eritrea, Chechnya, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the massacres against Muslims that took place send shivers through the body.

Not only was all of this in full view and earshot of the entire world, but a clear conspiracy has developed between America and its allies to prevent the dispossessed from obtaining arms under the cover of the iniquitous United Nations.

The people of Islam realized that they are the main targets for the aggression of the Judeo-Crusader alliance. All false propaganda about “human rights” vanished under the blows and massacres that took place against Muslims everywhere. The latest of these aggressions on Muslims, a calamity that matches the greatest confronted since the death of the Prophet, God’s blessings and salutations upon him, is the occupation of the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries—the foundation of the house of Islam, the place of the Revelation, the source of the message and the place of the noble Ka‘ba, the direction of prayer for all Muslims—by the Christian armies of the Americans and their allies. “There is no power and might except through God.”

In the shadows of this reality in which we live, in the shade of this blessed and sublime awakening that has extended over patches of this world and the Islamic world in particular, I meet with you today, after a long absence has been imposed on the scholars and preachers of Islam by the iniquitous Crusader campaign under the leadership of America. The latter fears that the Islamic community will be incited to rise against its enemies by the scholars and preachers of Islam who follow in the path of their pious forebears, may God be pleased with them, among them [the thirteenth-century scholar Taqi al-Din] Ibn Taymiyya and [the seventh-century judge] Al-‘Izz Ibn ‘Abd Al-Salam. Therefore the Crusader-Jewish alliance resorted to killing and arresting the most emblematic of sincere scholars and hard-working preachers. We need not commend any specific one of them to God.

They resorted to killing the struggler Shaikh ‘Abdalla ‘Azzam, God have mercy upon him. They arrested the struggler Shaikh Ahmad Yasin at the site of the ascension of our Prophet, God’s blessings and salutations upon him, as well as the struggler Shaikh ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Rahman. In the same way, through America’s determination, a very large number of scholars, preachers, and young people in the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries were imprisoned, among them the prominent Shaikh Salman Al-‘Awda, Shaikh Safar Al-Hawali, Shaikh Ibrahim Al-Dubayan, Shaikh Yahya Al-Yahya and their brothers. “There is no power and might except through God.”

In the wake of this injustice, we have suffered by being prevented from addressing the Muslims. We have been exiled from Pakistan, the Sudan and Afghanistan, hence this lengthy absence. But by the Grace of God, a safe base has become available in Khurasan on the summit of the Hindu Kush, this summit where by the Grace of God, the largest infidel military force of the world was destroyed, and the myth of the superpower withered before the strugglers’ cries “God Is Greater.”

Today, from atop the same summit of Afghanistan, we work to lift the injustice that had been imposed on the Islamic community by the Judeo-Crusader alliance, particularly after they have captured the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries. We ask God to bestow us with victory, for He is victory’s patron and is most capable of it.

In the summer of 1996, Osama bin Laden was not a figure much known in the West. Few newspapers had published much about the man, despite his status as one of the most successful and well-financed recruiters of Arab fighters during Afghanistan’s struggle against Soviet occupation during the 1980s.[24] Two years earlier, he had acquired notoriety for being expelled from Saudi Arabia. He had not only violated his promise to Saudi security officials not to continue supporting armed insurgents in Yemen. More urgent to Western officials, he had expressed opposition to the royal family’s decision to host American and Western military forces in its defence against Saddam Hussein’s forces during the Gulf War in 1990. Much of what Americans knew about bin Laden at the time was restricted to a handful of Central Intelligence Agency analysts who began focusing on bin Laden’s activities in 1991.[25] Still, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, including the program responsible for tracking security threats abroad, had yet to open a file. This speech provided the FBI with the rationale to do so.[26]

A wind-blasted mountain eyrie, well removed from centers of power, was an unlikely place to launch a war on the eve of the twenty-first century. The technology on hand for public documentation, a simple tape recorder loaded with a Sony ninety-minute cassette, was hardly more auspicious. In fact, bin Laden was confronting the bleakest prospects of his career. During the late 1980s, as the Soviets prepared to withdraw from Afghanistan after nearly a decade of occupation, he had become Saudi Arabia’s cause célèbre. His leadership of Arab volunteer fighters who had traveled to Afghanistan, “Arab-Afghans” as they were called, was considered to be a tribute to the extension of Islam’s banner over infidel lands. By 1990, however, the Soviet Union had not only withdrawn from Afghanistan, but had ceased to exist. The war was over, the struggle, or jihad, victorious, and bin Laden’s relevance in the postSoviet world increasingly uncertain. Throughout his life, bin Laden’s primary leverage had been financial, whether through membership in his father’s multi-million dollar engineering and trading company or through his talents as a fund raiser. Once the first Gulf War began, however, his financial backers showed increasing restraint. Bin Laden’s primary state sponsor, the Saudi royalty, redirected its wealth to shoring up regional security in collaboration with the United States. His opposition to foreign troop presence in the Saudi kingdom hardly helped, and, after King Fahd stripped him of his citizenship in 1994 for his maverick political views and financial support of militants, his own family disinherited him and he subtracted another $20 million of inheritance from his net worth. His biggest blow came in 1996, when after four years living and working in the Sudan, he was forced to leave the country, made stateless for the first time in his life. What hope he had in recovering $165 million in debts was soon dashed by the Sudanese, who informed him of their inability to pay back their loans. Six weeks before his mountain declaration, an unexpected cache of $5,000 had been met with unimaginable joy because he, his family, and his followers were ravenous and could not afford basic amenities.[27]

If bin Laden’s material woes were acute, the challenges he faced in leading a militant struggle anywhere in the Islamic world were unprecedented. By mid-1996, favored battlefields in the Middle East and North Africa had dried up, God’s warriors having been either co-opted by states with promises of Islamic reform or shamed into withdrawal by communities sick of bloodshed and puritanical zeal. Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, long the state’s principal opposition movement, had renewed its commitment to non-violent reform in efforts to distance itself from a four-year streak of militant attacks on Egyptians and foreigners alike; Algeria’s horrific civil war in the early 1990s had led to a popular referendum in favor of the state and a military crackdown on

Islamic extremism; in the Palestinian territories, widespread protesting under the first Intifada, or “uprising,” had subsided as the Palestinian Liberation Organization began a new round of peace negotiations with the Israeli government; in Yemen, a war with southern separatists in 1994 had given way to a period of state consolidation and the quelling of militant attacks against the socialist opposition; and in Saudi Arabia, the Islamic “Awakening” (al-sahwa) movement, so outspoken a critic of state abuses and capitulation to foreign interests during the 1980s and early 1990s, had dissipated under equally aggressive state consolidation and co-optation. Beyond the Middle East, frontiers of armed jihad were not much better. In the Balkans, war-torn communities that formerly had been privileged destinations for Arab militants deprived of their Soviet enemy in Afghanistan after 1990 were being patrolled by North Atlantic Treaty Organization peacekeeping forces. Southeast Asia’s economic boom was being accompanied by public support for a Muslim corporate ethics that eschewed militant jihad. In Afghanistan itself, the Taliban, a popular armed resistance movement launched just two years earlier by ethnic Pashtun “students” (taliban in Pashto) of God’s law, were open allies of the United States, despite their opposition to Afghanistan’s standing government.[28] Among the American administration’s top reasons for such support was to establish a regional front against Iran and China, whichever Afghan administration should come to power. More particular was the matter of securing a natural-gas pipeline through the Taliban heartlands that could deliver Central Asia’s vast natural gas reserves to Western-bound ships in the Indian Ocean without Russian or Iranian interference. The United States hoped that the project would be awarded to the Union Oil Company of California (UNOCAL), an optimism that was backed by the support of Mulla ‘Umar, paramount leader of the Taliban, who appreciated the revenues that UNOCAL could bring to southern Afghanistan’s beleagured people. Seven months later, bin Laden would present himself at Mulla ‘Umar’s doorstep in Kandahar in hopes of a favorable hearing.

These obstacles to leading a war against the United States were further complicated by a growing array of reports that bin Laden was not, in fact, a very good fighter. Throughout his life, many who encountered him found him to be shy, hesitant to talk, and persistently adolescent. His advocacy for armed jihad in Afghanistan, including his own brief experience combating the Soviets in 1987, certainly toughened his image. By 1990, his reputation as Lion of Jihad had been secured through tireless efforts by Arab-Afghan propagandists supported by the powerful Saudi media industry. Such efforts included the use of audiocassettes; in 1990, a single speech by bin Laden sold 250,000 copies in Saudi Arabia alone. As he grew more controversial, however, copies of heroic speeches and narratives about him gradually disappeared. Compromising accounts of his leadership and military achievements began circulating among a growing number of Arab-Afghans who had fought alongside him or heard stories about him. The 1989 siege of Jalalabad against the communist Afghan government, newly liberated from the Soviets, had gone badly. Spearheaded by Pakistan’s security apparatus, the Inter-Services Intelligence, with support from America’s own Central Intelligence Agency, long the ISI’s benefactor, the siege proved to be a virtual bloodbath for bin Laden’s men.[29] Recruits at bin Laden’s training camps complained about his poor organizational oversight and were put off by his tendency to refer even basic questions to Egyptian lieutenants.[30] Others were frustrated by his tendency to shirk deeper questions about the religious merit and ethics of jihad.[31] The seriousness of such reports was underscored by a more crippling trend: fewer and fewer recruits were coming to bin Laden’s camps. Who exactly was the enemy now that the Soviets had left? The prospect of fighting other Muslims was deeply concerning to many, quite apart from the dwindling of financial support for the Afghan cause by Saudi and other Arab states. Bin Laden himself acknowledged as much when, in 1992, he and his supporters in Peshawar, Pakistan, packed up and headed to the Sudan, announcing to anyone who would listen that “al-Qa‘ida is finished.”[32]

Four years later, bin Laden sought a makeover. He hoped to be seen as someone who, despite his statelessness, personal shortcomings, and lack of funds, could command a war against the United States. What resources did he have to be taken seriously? What leadership style would he cultivate in trying to overcome the obstacles that confronted him? What was the nature of al-Qa‘ida for militants and potential supporters during its most coherent years leading to the 11 September attacks in the United States, and what could bin Laden do to mobilize these views in his favor?

In exploring these questions, I rely in this book on a collection of audiotapes that were deposited in his residential compound in Kandahar, Afghanistan. Containing over 1,500 volumes, the collection functioned as an audio library for Arab-Afghans in bin Laden’s coterie between 1997 and 2001. Featuring roughly 2,000 hours of lectures, speeches, and conversations, the tapes provide a record of the issues and debates that informed the worldviews of those who gathered in bin Laden’s own home. Many of the collection’s most represented speakers are among the Arab world’s most esteemed Muslim jurists and preachers. The top seven include Saudi shaikhs ‘A’id Al-Qarni, Salman Al-‘Awda, Muhammad Ibn Salih Al-‘Uthaimin (second, fourth, and sixth most featured speakers respectively), Kuwaiti scholar Ahmad Al-Qattan, Palestinian jurist and militant ‘Abdalla ‘Azzam, Yemeni shaikh ‘Abd al-Majid Al-Zindani, and Syrian scholar ‘Abd al-Rahim Al-Tahhan, the most well represented speaker in the collection. Given these individuals’ accolades, the collection offers a unique resource for considering the ways Islam has been co-opted by what many have come to think of as history’s most sophisticated terrorist organization. The cassettes provide an archive, however, not primarily of bin Laden’s own distorted views and efforts to craft leadership, although I focus much on these in this book. The archive preserves a much more eclectic range of voices. Some are well known while others will never be identified. Some venture unequivocal support for bin Laden’s goals while others express criticism. Some speak from generations past, including a preacher who died in the 1960s, while others recorded themselves as late as 18 November 2001. While roughly 98 per cent of the tapes are in Arabic, evidence on cassette cartridges and accompanying jackets contain printed and handwritten words betraying diverse origins and stages of transmission. Some of the tapes contain handwritten messages. “A gift to Shaikh Osama bin Laden,” wrote one anonymous admirer in Arabic on a tape composed of anthems in a foreign tongue in tribute to his host. Other tapes contain notes for other recipients. Given the social and decentralized nature of audiocassette production and consumption in the Islamic world, and the ways tapes are regularly swapped among friends and would-be associates, the value of the collection is perhaps best understood as a collaborative audio recording archive that was given shape through bin Laden’s stewardship by virtue of its location in his Kandahari residence. These and other observations on the culture and use of audiocassettes, and this archive in particular, are the topic of chapter four. In assessing the significance of the tapes for shaping al-Qa‘ida’s worldview, we should remember that while we cannot know exactly which tapes bin Laden himself listened to, we can safely say that these tapes were a communal resource, an audio “library” with borrowing privileges for residents, guests, and visitors in bin Laden’s residence who wondered what to make of Arab-Afghan initiatives being mobilized under his roof. The vision of al-Qa‘ida under bin Laden’s leadership that emerges from these tapes, and that is the subject of this book, is more than one of his own making. It is a composite, tentative, and at times deeply conflicted vision, the inconsistencies of which reflect the circumstances of its place and time. If these inconsistencies are no less endemic to al-Qa‘ida today than they were during its halcyon years, the archive provides a definitive record of how people closely involved with the world’s most notorious militant movement sought to manage dissension through recourse to venerable traditions of Islamic theology, law, and cultural interpretation broadly writ.

Observers of al-Qa‘ida’s history and development have pointed out that its essential anti-Americanism was not, in fact, intrinsic to the organization itself but rather developed between the years 1996 and 2001.[33] Given the tape collection’s assemblage during this important period, the tapes offer special lessons on why and how the United States became enemy number one. As noted by others, al-Qa‘ida’s militant founders and original charter, drafted in 1988, make no mention of America.[34] Neither, for that matter, was Russia or any of the Soviet republics mentioned as a target for the organization. Rather, al-Qa‘ida’s goals were broad to the point of inspired diplomacy: “To lift the word of God; to make His religion victorious.” Under such a banner might sparring Islamic factions be reminded of common ground. As bin Laden himself looked into a future beyond Soviet control of Afghanistan, toppling the socialist government of South Yemen remained his primary militant objective, even as late as 1994.[35] America’s threat to the Islamic world concerned him, of course, and was spoken about in no uncertain terms as early as the late 1980s, as evidenced on cassettes that I examine in later chapters. It was only after his expulsion from the Sudan, however, and most starkly in his summer speech from the peaks of the Hindu Kush, that the United States would become the principal subject of bin Laden’s fiery discourse.

The tapes document the steady rise of anti-Americanism among Muslim militants through the 1990s. To some extent, militants draw from broader critiques of Western secularism and cultural depravity that had been a recurrent theme in the writings and sermons of conservative Muslim reformers since the nineteenth century. As Muslim scholars under European colonial rule in countries like India, Egypt, and Algeria, such reformers invoked clean ideological boundaries between the political aspirations of an Islamic civilization, a superior form of modernity, and its predecessors. Central to these aims was the establishment of a moral community based on Islamic law, one that could, as bin Laden puts it in his opening supplications, “command what is right and forbid the wrong.” Justice in such a community would ideally be secured by an Islamic state. For Sunni militants, however, the likelihood of securing an Islamic state had become increasingly remote over the course of the twentieth century, the 1924 abolition of the caliphate by Turkish nationalists having been a decisive blow. Iran’s revolution against the United States-supported regime of Shah Reza Pahlavi in 1979 offered a shining example of statehood from the Shi‘a world, and many Sunni militants would take inspiration from the Shah’s successor, the Ayatolla Ruholla Khomeini. More auspicious were recent events in the Sunni pale. In the Sudan, a Revolutionary Command Council had seized power in 1989 with heavy support from political parties committed to Islamic law. In Afghanistan, Mulla ‘Umar’s Taliban leadership had been secured in 1994 with his appointment as the Commander of the Faithful (amir al-mu’minin), a title long reserved for Muslim caliphs. Still, state powers and their clerical representatives had, throughout the 1990s, secured an extraordinary compliance among Muslim revolutionaries across the Islamic world, as evidenced by bin Laden’s own forced exile from the Sudan earlier that summer. Islamic states, however ideal, were still part of an international system of state regulation and surveillance. For these reasons, as we will learn throughout this book, militants’ speeches frequently drift toward more emancipatory horizons of territorial reclamation by righteous minorities.

In the tape collection, militants cite the presence of American-led troops on the Arabian Peninsula as a principal reason for waging armed war against the West, though close behind this event lies their own leaders’ servitude to American and “Jewish” interests in the region. For those sympathetic with bin Laden, few events confirmed the seriousness of his pitch about America’s threat to Muslim lands, and the need to take up arms, more than the expanding scope of United States military operations in the Islamic world’s historic heartlands. More broadly, of course, the United States was seen as the world’s sole superpower after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, an opinion bolstered by the steady growth of America’s arms industry and United States-led military operations across the globe. Muslim populations increasingly experienced these operations directly, most notably in the Persian Gulf war of 1990 when Iraqi forces were driven out of Kuwait by American-led coalition forces based mostly in Saudi Arabia. In the shadow and aftermath of the war, American troops along with a growing arsenal of private military subcontractors expanded operations in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt, Oman, Yemen, and Somalia. Each initiative gave rise to debates and controversies that informed the consciousness of an expanding transnational Muslim community. For many Muslims, the United States’ positive role in the Islamic world was deeply compromised by a lack of progress in Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. Especially vexing was its $3 billion annual aid package to Israel, a sum which, for many Muslims, seemed all the more egregious given nightly televised broadcasts showing Palestinian suffering and the rapid expansion of illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza.

In his summer of 1996 speech, bin Laden tapped these sentiments in presenting his case, the effect of which I’ll consider further in chapter nine. Humble supplication sets the tone of the speech as bin Laden cites Qur’anic verses along with revered narratives of the Prophet Muhammad’s words and deeds (ahadith, singular hadith). Islam requires Muslims to “speak the right word,” but also to use physical force when necessary: “If people see the oppressor and fail to restrain him with their hand, they draw close to an all encompassing punishment from God.” Immediately, bin Laden clarifies the enemy at large:

It should not be hidden from you that the people of Islam have suffered from injustice, oppression, and aggression by the Judeo-Christian alliance and their collaborators, to the extent that the Muslim’s blood became the cheapest and their wealth and natural resources as loot in the hands of the enemies.

Military and economic attacks rank paramount, whether in Palestine, under Israeli suzerainty; in Iraq, whose population was suffering under United Nations’ economic sanctions and American bombing sorties designed to unseat Saddam Hussein; or in a host of other settings in the Middle East and beyond. The theft of vital elements—blood and natural resources—is made more unconscionable by the United Nations’ “clear conspiracy” to deprive Muslims of weapons. Omitting the fact that, by 1990, the Saudis had become the United States’ principle arms market, surpassing even the Israelis, bin Laden ventures further to locate the final culmination of Judeo-Christian aggression in the “Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries,” an epithet for Saudi Arabia employed by those who contest the house of Saud’s claims to leadership and that refers instead to founding mosques in the cities of Mecca, the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad, and Madina, site of the first Islamic community and Muhammad’s tomb. Especially grievous for bin Laden is the “long absence” imposed on the “scholars and preachers of Islam by the iniquitous Crusader campaign under the leadership of America.” Included among its ranks are clerics jailed by Saudi authorities such as Salman Al-‘Awda and Safar Al-Hawali, as well as those from other countries who received training in Saudi Arabia but who were later jailed or killed on foreign shores. These include the alleged Palestinian militant cofounder of al-Qa‘ida, ‘Abdalla ‘Azzam, and the Egyptian shaikh ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Rahman, imprisoned in the United States for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombings. “In the wake of this injustice,” announces bin Laden, inserting himself into the ranks of these widely recognized scholars, “we have suffered by being prevented from addressing the Muslims. We have been exiled from Pakistan, the Sudan, and Afghanistan, hence this lengthy absence. But by the Grace of God, a safe base has become available in Khurasan on the summit of the Hindu Kush.” Bin Laden’s “safe base” (qa‘ida amina), hovering over battlefields where Arab-Afghan fighters had wrested victory from godless Soviet infidels, would become the symbolic touchstone of his revolution.

Al-Qa‘ida’s spectacular base aside, bin Laden had a recruitment problem. In trying to build what would necessarily be a transnational corps of Muslim militants, he needed to convince audiences that efforts were best directed to attacking the United States rather than the more familiar arsenal of enemies at home, foremost among them their own authoritarian leaders. While many militants sympathized with those who worried about an expanding American empire and dreamed of its collapse, few could envision diverting resources from struggles in their homelands, or—imprisonment and exile having delayed the likelihood of near-term victory—in other Islamic countries perceived to be suffering under the occupation of infidels. Bin Laden himself had been among these skeptics just two years earlier. For every speech identifying America as a prime target are dozens of other speeches identifying other more classic enemies of Islam. These include idolators (mushrikun), ingrates who have rejected God’s mission (kufar), communists, secularists, people electing submission to economic and material orders (jahiliyya), and “freemasons”. All of these are more likely to characterize individuals or communities who would self-identify as Muslim than to characterize Jews, Christians, agnostics, or members of some other confessional group. The clerics and intellectuals who had appealed to militants throughout most of the twentieth century had developed their most critical vocabularies in opposition to those within the house of Islam, not beyond. Bin Laden’s task would become no easier given the growing supply of volunteers from Saudi Arabia after 1997. As others have shown, few Saudis felt that attacking the United States was part of Islam’s master plan.[36] While militants from countries lacking Muslim majorities also increasingly enlisted in camps by the late 1990s, they typically sought to drive infidel occupiers from Islamic lands rather than to take the fight back to their own countries. Especially after 1998, when al-Qa‘ida’s bombings of United States embassies in East Africa greatly amplified bin Laden’s reputation across the world, militants who had been born in the West, or who had lived, worked, and received education in Western countries, were prone to make distinctions between one Western “enemy” and another. Abu Mus’ab Al-Suri, for example, whose lectures to recruits are featured on nine cassettes in the collection, lived in Syria, Pakistan, Spain, and London before moving to Afghanistan to fight alongside bin Laden. He decried bin Laden’s attacks against the East African embassies, feeling that bin Laden’s blanket antiWestern tirades had distracted militants from more important strategic victories that would unite the Islamic community worldwide.[37] Even when prioritizing strikes against Western interests, for example, Al-Suri took pains to rank targets according to their likely success in uniting the Islamic community, beginning with “Centers of missionary activity and Christianization, the cultural envoys, and the institutions in charge of the American-Western civilizational and ideological invasion,” followed by their regional economic assets (oil reserves, mines, then ocean facilities), diplomatic institutions, military entities, intelligence and security entities, and so forth.[38] Among cosmopolitan militants looking for tactical guidance in diverse locales, bin Laden’s Declaration risked conflating American territory with America’s perceived geopolitical war on Islam, the latter of which represented a more diffuse and urgent set of “missionary,” “cultural,” “civilizational,” and “ideological” threats to Muslims. Bin Laden’s inspired pledge to defend his sacred homeland from American occupiers was appreciated. Perhaps attacks within the United States would be a necessary corollary. But to what extent could he lead the larger war for oppressed Muslims everywhere? Could he set aside his own priorities in the Arab world, such as his own thirst for cleansing Saudi Arabia of foreign influences, in the interests of a more transnational Muslim community? Given that his ascendancy as a leader had been inextricably linked to his financial connections in the Kingdom, whether as the son of a multi-millionaire or as a gifted fundraiser, could he truly represent “the dispossessed,” as he claimed to do in his late summer speech in 1996?

In 2002, the Qatar-based Al-Jazeera television channel broadcast an interview with Saudi scholar Muhsin Al-‘Awaji, in which he was asked about the reasons for bin Laden’s popularity among supporters.

Bin Laden is perceived to be a man of honor, a man who abstains from the pleasures of this world, a brave man, and a man who believes in his principles and makes sacrifices for them...what the Saudis like best about bin Laden is his asceticism (zuhd). When the Saudi compares bin Laden to any child of wealthy parents, he sees that bin Laden left behind the pleasures of the hotels for the foxholes of jihad, while others compete among themselves for the wealth and palaces of this world.[39]

Throughout the book, I explore the ways in which bin Laden’s reputation for asceticism helped define his leadership. Through the latter years of his life, bin Laden’s worldly seclusion was animated for global audiences by his reluctance to release videos of himself and by a widely circulated photograph of him sporting a white turban and a controlled smirk. When pressed for his whereabouts, most experts pointed to his likely refuge in the Afghan-Pakistan borderlands. Others insisted that he had withdrawn to the deserts of Yemen or was dead. Traces of his continued existence reached audiences only through sound, in a voice that, deprived of its bodily host, seemed very eerie. When I mentioned my work to people during the years before bin Laden’s death, I often get the reply “Are you listening to his actual voice?” followed by “What’s that like?. Creepy?” The attacks of 11 September lent bin Laden a haunting shade.

And yet, how exactly was bin Laden’s withdrawal construed by his different audiences? By his ability to elude capture by the world’s most sophisticated and coordinated security networks? By his desertion of family and friends in pursuit of an enemy in far away lands? By his quest for an ideal Islamic order beyond the “wealth and palaces of this world”? Veils of withdrawal come in many folds, each with its cultural history. In Islam, asceticism has a venerable legacy in the examples of holy men and women, reformers as well as warriors, who found the attachments of this world too heavy. In the final section of his Declaration speech, bin Laden invokes this tradition, exhorting women, in particular, to lend support to male military and security personnel by “practicing asceticism from the world, and by boycotting American goods.” He ventures further: “If economical boycotting is combined with the strugglers’ military operations, then the defeat of the enemy would be even nearer, by God’s permission.” In bin Laden’s speech, women’s ascetic discipline, practiced through warfare against a Western economic order led by the United States, is not peripheral. As I discuss in chapter nine, their example inaugurates his call to every Muslim, and especially the youth, to launch armed jihad against the West. English-speaking audiences have been prevented from understanding the significance of asceticism in his Declaration given the poor quality of its original hasty translation. His statement “We expect the women of the Land of the Two Holy Sanctuaries and elsewhere to carry out their role by practicing asceticism from the world, and by boycotting American goods” has reached English readers without the reference to asceticism (italicized here). The function of asceticism is unambiguous in the audio recorded version of the speech in the collection. Shortly later, bin Laden underscores the urgency of asceticism, and its gendered undertones, when commending the leadership of Islam’s second caliph ‘Umar Ibn alKhattab. One of Islam’s earliest fighters, ‘Umar was renowned for his spartan table of bread, olive oil, barley and coarse salt. Zealous to defend his new faith, most prominently in battles on Islam’s expanding frontiers, ‘Umar was also famous for his generosity, commending this virtue to his warriors on the eve of en epic battle with the Persians: “Zuhd is taking what is due from everyone who owes it and giving what is due to anyone who has a right to it.” Bin Laden would regularly speak of ‘Umar’s leadership. When rallying Muslim listeners to martyrdom in the final section of his 1996 challenge to the Americans, bin Laden found natural recourse to ‘Umar’s example, noting that ‘Umar’s own sister Fatima had converted to Islam even slightly before him.