Author’s contact: ishkah at protonmail dot com

Theo Slade

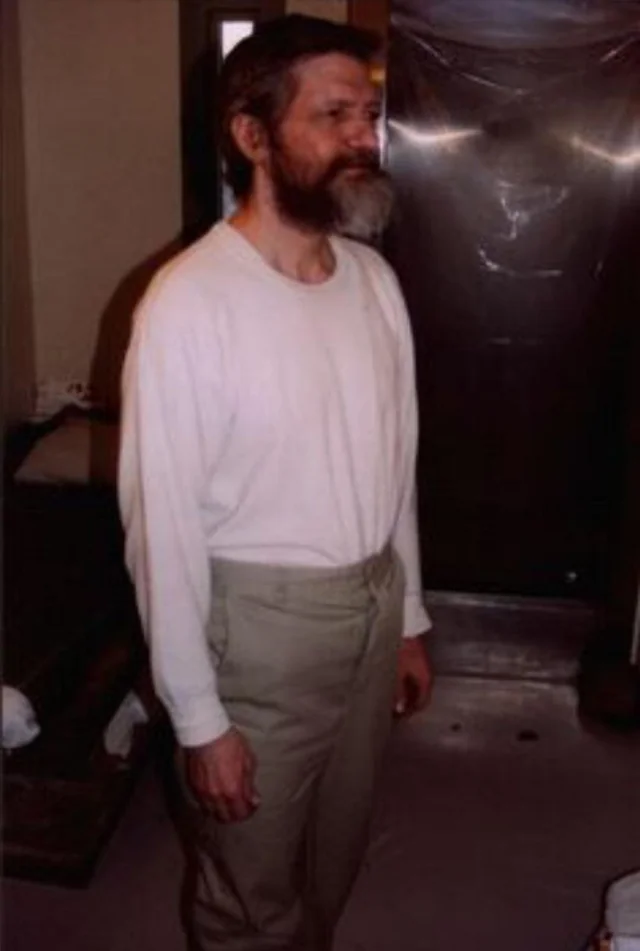

Frequently Asked Questions about Ted Kaczynski

What were the main reasons Ted became a terrorist?

A socially alienating culture + a neurological diversity

A desire to return to a more innocent time in his childhood

How did Ted’s violent desires evolve?

When did Ted first decide to become a terrorist?

1. Humiliation at a therapists office (1967 – Aged 24)

2. An aborted terror attack (1971 – Aged 28)

3. The first mailbomb (1978 – Aged 35)

Fall 1977: Destroying another cabin

Prepared to start killing people

May 1978: Northwestern Security Guard Opens Mailbomb

Desires to go out in a Murder-Suicide

A short note on Ted’s misleading answers to this question

Did Ted ever regret his actions?

Did the CIA turn Ted into a terrorist?

How did Ted attempt to justify building the unsent bomb under his bed?

Was Ted a compassionate person?

What were Ted’s politics & philosophy?

How low-technology did Ted wish everyone would live?

Did Ted ever really think of himself as an anarchist?

Was Ted ever actually an anarchist though?

What were his politics at the end of his life?

What, if any, were Ted’s philosophical and literary influences?

How much technology did Ted use?

How much did Ted rely on others for money?

Did Ted take anti-depressants?

Did Ted carry on playing around with math?

Did Ted enjoy his hermit life?

What kind of education did Ted value?

What reading did Ted recommend?

The wait for the search warrant

The FBI’s first conversation with Ted

Ted is finally charged with being the Unabomer

Could his family not have risked Ted striking again by saying nothing or threatening Ted?

Could his family not have risked Ted getting the death penalty by saying nothing?

What was Ted’s state of mind?

What were the main reasons Ted became a terrorist?

Quoting Ted’s brother David:

When something like what happened here happens, people all over the world question; how could any human being do this? And when somebody like my brother does this from our family, the question becomes extraordinarily, existentially intense, like how could my own brother do this.[1]

I think it was likely a combination of these four main reasons:

-

A socially alienating culture + a neurological diversity

-

A desire to return to a more innocent time in his childhood

-

An uncompromising idealism

-

Human nature

A socially alienating culture + a neurological diversity

Ted used to worry about getting heart attacks from the anger at dirt bikes passing by his cabin and would write letters to his family that were read as manic. Quoting Ted’s bother, David:

There’s a fight or flight syndrome, he had gotten as far away from his stressors thinking that they were external.[2]

Ted wanted to be a hermit. He wanted to read a lot of books undisturbed in a very small, one room cabin. He would take short breaks to bathe in the beauty of the forest. But, he had a perfectionist mindset about desiring to find mental well-being in the forest. This meant never being disturbed by other people. So, it is interesting to note that, short of buying vast acres of wildlife habitat for him, guarding it so no one could get in and not letting planes fly overhead, we pretty much helped him achieve the next best thing in a prison cell as far as he is a manifestation of his traumas.

The same is true for violent people who get to extort and be violent with other prison inmates without much consequence.

Ted just presents a really interesting problem for conservatives who like to think prison is retribution, because sometimes prison can be what the traumatized person desires, so they don’t have to wrestle with as much choice. And although that may only be true of a minority of people, it can be reflective of emotional states of mind within the majority of us.

So, the only real solution I can see is not to be satisfied with giving traumatized people to an extent emotionally what they want, but to heal the trauma and learned patterns of behavior that lead them to that point in their life.

I don’t think all unjustified bombings are the result of mental illness, but I do think there is a probability of a neurological diversity such as autism, due to the nature of his lone bombings, where he was driven to murder through externalizing his pain and not simply swept up in some separatist terror campaign.

An FBI agent on his case I think suggested rightly that:

One of the reasons that he gravitated towards math [is that] it’s something he could do in isolation. It’s not a team project.[3]

As his brother neatly summarized:

There were parts of him that were a little different. … Ted did not have many friends. There were periods of time when nobody ever came to the house to visit Ted.[4]

So, potentially he was drawn to math as the most entertaining way to make the most out of the long amount of time kids must spend studying:

I was identified with the “Briefcase Boys” (academically-oriented students).[5]

Pure mathematics is useless from a practical point of view and that’s what I studied (laughs). I mean, a lot of people don’t understand what mathematicians really do, you know? They think they sit there adding up columns of figures or something like that. But that isn’t what it is. It’s more like puzzle solving. I just got a kick out of it. I enjoyed it.[6]

It wasn’t until long after he’d felt alienated by the elite levels of academic society that he made a conscious effort to take an interest in subjects like anthropology, and even then it was with the goal of studying them in order to find answers to how societies change, so that he could know the best way to contribute towards bringing about a revolution that would, even if just by happenstance, destroy recent high-tech cultural evolution.

One potential reason for his personal anti-tech philosophy then is that he developed a kind of gaming addiction to mathematics and narrowed down what niche field within it he found entertaining further and further until it had hardly any value to him anymore. So, having been pressured to do well at school for ‘being good at schools sake’, he never learnt the internal value of the high-tech cultures he was studying.

In the book After Virtue, MacIntyre tries to explain this importance of perusing tasks for their internal value:

The teaching process may begin with the teacher offering the child candy to play and enough additional candy if the child wins to motivate the child to play. It might be assumed that this is sufficient to motivate the child to learn to play chess well, but as MacIntyre notes, it is sufficient only to motivate the child to learn to win – which may mean cheating if the opportunity arises. However, over time, the child may come to appreciate the unique combination of skills and abilities that chess calls on, and may learn to enjoy exercising and developing those skills and abilities. At this point, the child will be interested in learning to play chess well for its own sake. Cheating to win will, from this point on, be a form of losing, not winning, because the child will be denying themselves the true rewards of chess playing, which are internal to the game. The child will also, it should be noted, enjoy playing chess; there is pleasure associated with developing one’s skills and abilities that cannot come if one cheats in order to win.[7]

A desire to return to a more innocent time in his childhood

Quoting Ted’s brother, David:

One thought is, it’s connected to hatred, it’s that hatred of the self and hatred of others really do go together. And so my biggest fear for many years actually after a friend’s brother committed suicide was that Ted seemed so miserable I was afraid someday I’d hear that he had committed suicide and I think that was likely in his diaries he actually had some sort of scenario that involved murder-suicide, I think some of his aggression toward our family our parents which I really couldn’t understand was emotionally violent, in some sense metaphorically it was killing mom and dad, but it had some of that flavor.

When I ultimately ended up reading my brother’s diaries it was like opening a window on hell, I had no idea he was suffering to this extent, so part of his dynamic and maybe with other mass murderers there’s this this incredible intense psychological isolation, so then I think well if only teddy had a friend a mentor and then of course I realized many people could have been but he pushed them away, but how do you reach that person that’s really hard to reach? Certainly we see some correlation like with bullying in the school, so the kid is isolated, the kid feels absolutely powerless, this is not to excuse violent acting out, but it strikes me we have to create a different kind of communal consciousness as well, it’s not just our individual minds it’s the candle lighting the candle a thousand times, that somehow we have to make this idea of compassion, we have to find a way to spread it and not give up and not fail to spread it with people who seem resistant to it.[8]

After being moved up a year in school, Ted was bullied and found an escape fantasy in books about Neanderthals living a primitive life.

I think his desire to kill scientists was a kind of murder-suicide fantasy, to kill in others that which he hated in himself. For instance because he didn’t have the capability to actually escape into primitive life as a child, he said he developed a ‘perverse pride’ in being anti-social and dedicating himself to mathematics, which he later regretted.

You can also think about the contrast he makes in his mind between the ‘normal’ desire to return to primitive life and the ‘abnormal’ desire to pursue ‘surrogate activities’ like scientific research as him kind of glorifying ignorance as a character virtue and rejecting any divergence from that, because in ignorance we can find an authenticity matched to our environments, connected to a long period of our evolutionary history, which he thinks we have the ability to return to:

Living in the woods, once you get adapted to that way of life, there’s almost no such thing as boredom. You can sit for a while, and just for hours, you can just sit and do nothing and be at peace.[9]

Fundamentally the desire for a primitive way of life is often simply a desire for a more innocent time in one’s childhood:

Where Zerzan’s argument becomes problematic is in the essentialist notion that there is a rationally intelligible presence, a social objectivity that is beyond language and discourse. To speak in Lacanian terms, the prelinguistic state of jouissance is precisely unattainable: it is always mediated by language that at the same time alienates and distorts it. It is an imaginary jouissance, an illusion created by the symbolic order itself, as the secret behind its veil. We live in a symbolic and linguistic universe, and to speculate about an original condition of authenticity and immediacy, or to imagine that an authentic presence is attainable behind the veils of the symbolic order or beyond the grasp of language, is futile. There is no getting outside language and the symbolic; nor can there be any return to the pre Oedipal real. To speak in terms of alienation, as Zerzan does, is to imagine a pure presence or fullness beyond alienation, which is an impossibility. While Zerzan’s attack on technology and domestication is no doubt important and valid, it is based on a highly problematic essentialism implicit in his notion of alienation.

To question this discourse of alienation is not a conservative gesture. It does not rob us of normative reasons for resisting domination, as Zerzan claims. It is to suggest that projects of resistance and emancipation do not need to be grounded in an immediate presence or positive fullness that exists beyond power and discourse. Rather, radical politics can be seen as being based on a moment of negativity: an emptiness or lack that is productive of new modes of political subjectivity and action. Instead of hearkening back to a primordial authenticity that has been alienated and yet which can be recaptured – a state of harmony which would be the very eclipse of politics – I believe it is more fruitful to think in terms of a constitutive rift that is at the base of any identity, a rift that produces radical openings for political articulation and action.”[10]

An uncompromising idealism

What often goes along with a desire for ignorance is a cult-like desire to force others into your fundamentalist belief system or treat others rejection of your belief system as a personal insult to your revelation.

Consider for example this line from his manifesto: “In any case it is not normal to put into the satisfaction of mere curiosity the amount of time and effort that scientists put into their work.” It’s a fairly clear admission that he simply intuitively values primitive life as holding more value, and therefore any value a person does derive from modern life is not even counted.

Throughout Ted’s writings is often the hidden premise that he holds an evaluative asymmetry whereby anything that happens in wild habitat is automatically less bad than anything that happens in an industrialized society:

When one reads ‘Industrial Society and its Future’ and Anti-Tech Revolution, it is hard not to notice that Kaczynski evaluates problems caused by technology very differently than how he evaluates problems that arise in technology’s absence. This is most apparent in the middle paragraphs of ‘Industrial Society and its Future,’ in which Kaczynski compares industrial and pre-industrial life. After he has given an elaborate account of human powerlessness in industrial societies, he makes a concession: ‘It is true that primitive man is powerless against some of the things that threaten him; disease for example.’ Kaczynski does not, however, seem to think that this is a very significant problem. Instead he writes: ‘But he can accept the risk of disease stoically.’ This response invites a follow-up question: If the badness of the problems faced by ‘primitive man’ can be avoided if one accepts them stoically, then why can’t the badness of the problems faced by people in industrialized societies also be avoided through stoicism? The only explanation given by Kaczynski is that whereas a problem caused in the absence of technology ‘is part of the nature of things, it is no one’s fault,’ a problem caused by technology is ‘imposed.’ Of course, it makes sense to hold that while no-one is responsible for what nature does, someone might be responsible for what humans do. Kaczynski, however, does not seem to be concerned with assigning responsibility or blame; he is concerned with comparing the quality of human life in industrial versus pre-industrial societies. It seems, therefore, that Kaczynski holds that while a problem caused by technology is very bad indeed, a problem caused by nature, though it can be frustrating, is not nearly as bad, at least not in an ethically relevant way. It appears that on Kaczynski’s view, two equally hopeless situations can differ dramatically in how bad they are depending on whether the situation is caused by technology or caused by things in nature that count as non-technological.

This evaluative asymmetry can help explain several of Kaczynski’s priorities and areas of focus. It can explain why he is worried that our lives now depend on the operation of power plants that might fail, but not worried that pre-industrial lives depended on rain showers that might fail to come as expected; worried that people today are oppressed by bureaucracies, but not worried that people were previously oppressed by their tribes; worried that people now do tedious office work but not worried that work in pre-industrial societies could also be tedious. The picture that emerges is that in Kaczynski’s view, the harms that are averted by technology were not ethically relevant harms to begin, and that what we gain from technology today does not count as ethically relevant benefits. Given this picture, it makes sense why Kaczynski counts only the downsides of technology: There are few or no ethically relevant upsides to count.[11]

* * *

Quoting Ted’s brother, David:

I see the Kaczynski family as holding certain symmetries. For as far back as I can remember we were paired up based on certain similarities and differences in our looks and temperaments. Dad and I had lighter hair and brown eyes; Mom and Ted had dark hair and blue eyes. Dad and I were more social and easy going; Mom and Teddy tended to be anxious and somewhat withdrawn. On the other hand, Dad and Ted both expressed a strong commitment to reason over emotion, whereas Mom and I (increasingly as I grew older) tended to trust intuition over analysis. When upset, Mom and I reacted emotionally and then mostly got over it, whereas Dad and Ted (increasingly as he grew older) tended to withdraw. Dad, unless you count his suicide, never lashed out; Ted, after nursing his wounds through years of silence, lashed out in a big, big way, expressing his pent-up rage through angry, hyperbolic letters that marred his parents’ happiness, and finally through murderous bombs accompanied by elaborate (I want to say “tortured”) justifications.

When I was young, I tended to see Mom as the outlier. In contrast to Dad and Teddy (and me too, as a would-be member of a conventionally male club that prized rationality over feeling), Mom at times celebrated strong emotions.

My most vivid memory of this comes from a family vacation we took when I was in middle school. On a long drive to some forest camping spot in another state, Mom began to expound with enthusiasm on the classical Greek tragedies. She was fresh from reading Sophocles’s Antigone. Mom explained the drama’s plot, which entailed suicides, a sibling rivalry, an intense conflict between Antigone’s sense of justice and the law, and a blood bond stronger than life itself. I found the story inexplicable and troubling. Antigone’s irrational need to sacrifice her own life in defense of her dead brother’s honor seemed gratuitous, disproportional. It accomplished nothing; it only spread more misery. At every turn and twist of the story, I thought there surely could have been a way out of fate’s trap, if only the characters had had the foresight and sense to make rational choices.

I remember that Dad at some point lit a cigarette (one of the thousands that would eventually doom him) and Teddy rolled down his window and waved the smoke outside with exaggerated gestures. I wanted to do the same with Antigone.

How could Mom find nobility in such conflict and violence? Mom’s emotional exuberance clashed with my need for emotional stability, my grounding in what I regarded as reality.

How could following one’s principles lead to disaster? How could Antigone’s (or anyone’s) vital life force be converted into a death force?

I tried to be dismissive: Mom was a female given to emotional ex- cess; the story took place a long, long time ago; it was, after all, just a story. What could it possibly have to do with us?[12]

* * *

Quoting an FBI Report:

Dave then discussed at length an on-going “discussion and debate — a dialectic, in fact,” which he and Ted began in approximately 1978 concerning the nature of reality in the universe. They debated around a “core argument” for years, the essence of which concerned Ted’s belief that scientists had a truer picture of the universe than artists did, because of their reliance on the “Verifiability Criterion.” Ted defined this criterion as holding that a “fact” was valid only insofar as it could be proven “true or false.” Dave, on the other hand, believes that reality is not necessarily “black and white,” but includes many “mystical unknowables” which are a part of human experience not easily quantifiable, or even identifiable. Dave includes “Art” as part of this type of experience. Dave emphasized that Ted has long been committed to rationality as a guiding principle, and noted that a particular characteristic of Ted’s debating style was that he placed special emphasis on making his arguments compelling. In doing this, Ted characteristically stressed that since his ideas were based on a “rational ideal,” any action in support of them was justifiable. Dave expressed sadness in commenting that this type of justification would enable Ted to feel fully justified and even visionary in killing people to accomplish his “rational objectives.”[13]

Quoting Ted:

In a letter that I wrote my parents while I was at Harvard, I taped to the page a clipping … which read, in part: “… ‘I have been painfully forced to the belief,’ [Bertand Russell] once remarked, ‘that nine tenths of what is commonly regarded as philosophy is humbug. The only part that is at all definite is logic, and since it is logic, it is not philosophy.’ ” Below … I wrote: “I noted with triumph the above quotation of Bertand Russell in the Crimson. I have long maintained that philosophy is humbug and now I find that even a philosopher admits it.”[14]

* * *

Quoting Ted:

In the summer of 1982, Dave wrote me:

“I don’t remember finding it difficult as a youngster to admire you, and I don’t think my will was consciously frustrated by coming under the influence of your way of thinking, since I thought I came willingly, drawn by its intrinsic persuasion. I hope you will appreciate, in light of this, what a significant being you must have represented to me ... On a personal level, however, I felt a problem arose insofar as it appeared to me I could appear in your world ... [only] by assuming a shape appropriate to this world, but not wholly expressive of my own experience and consciousness. In other words, what I thought of as the openness on my part which made your thought-process accessible to me, was so little reciprocated that I could abide there only by forsaking a certain freedom of spirit.”

In brief, my brother was saying that he admired me but felt dominated by me. In 1986 he wrote:

“[Our parents] always encouraged me to look up to you, especially with regard to your intellect.... One unhealthy side of this, as we’ve discussed before, is that I may have learned to look up to you too much, to take your criticisms too much to heart, and to feel a little over-shadowed intellectually. I think one reason I became ego-involved in our philosophical discussions a few years ago was because I was still trying to establish myself on a plane of intellectual equality with you.”[15]

* * *

Quoting Ted:

To answer my brother’s question, yes, I could forgive him—under certain conditions. Basically, he would have to undo his treason by detaching himself permanently from the consumer society, from the system and everything that it represents. In order to do this, he would have to break off all connection with Linda Patrik, because her dominance over him is such that he could never make a lasting change in himself as long as he maintained a relationship with her.[16]

In taking David’s marriage to Linda so hard, and making his separation from her a requirement of his reconciliation, I think Ted was showing his desire to regiment people close to him into this cult-like uncompromising idealism which entailed seeing ignorance as a virtue.

Many conversations were treated as a fight where David had to stay away from subjects that would make Ted frustrated, and also run the risk of being deemed a coward for not expertly walking that line. All with the goal of scoring points against the other for simply scoring points sake:

“I received your last letter and note that it shows your usual generosity of character. Instead of being sore over the negative parts of my attitude toward you, you were favorably impressed by the positive parts.”

My brother does have a good deal of generosity in his character, but I now think that the nature of his reaction to my letter was less a result of generosity than of his tendency to retreat from conflict.[17]

Well, obviously I resented it. There was another strain to my feelings there. I don’t know if I can explain it properly. But in a way I was almost glad because my own brother turning me in in a sense made me look good. I mean, if A screws B, then it tends to make B look good, even if otherwise he might not look so great. I don’t know. So maybe that’s — That was perhaps an ignoble thought on my part. But that thought was present, I have to admit.[18]

Human nature

I think there is a naturally wide capacity in everyone to either be intensely cruel or radically compassionate, and so a person’s character is almost always going to be dependent on how we construct our environments and whether we receive an element of moral luck.

Quoting Ted’s bother, David:

[I] think we’re not being honest with ourselves if we don’t look at human history and say there’s something somewhat normal about violence in human beings, we have murders, we have genocides and we have wars.

I remember my father telling a story from his father who had been born in Poland and pressed into the polish army and he said ‘well, we went to fight this battle and I don’t know what happened, but we started killing everybody in the town and then men started raping women’.

And these were normal family, how did this happen? We know that part of the training of soldiers is to desensitize to the humanity of the enemy so it’s true we can be trained for compassion, we can be trained to shut down compassion, so I think the highest teachings of all religious traditions is to try to create an antidote to this nihilistic possibility that probably lives to some extent in all of us, to smaller or greater degrees.[19]

How did Ted’s violent desires evolve?

I’ve attempted to list out some of the possible answers below. Included in this list are some potentially missed opportunities to have set Ted up to be able to handle better the trials and tribulations life throws at people. Also, potential missed opportunities in which Ted maybe could have been influenced to stop his bombing campaign earlier. For example, we don’t know what year he began regretting trying to bomb an airliner full of people out of the sky, but doubts about the reasonableness of his actions such as this could have been a turning point. There was even a point where he went to see a therapist and planned to go back, but one reason he didn’t was the cost of each session.

The Timeline

-

Separated from parents as a sick baby at a key time for attunement and attachment with parents. His mother felt this was key to the man he became. Ted felt his parents used this event to avoid responsibility for the impact their inadequate parenting had on his character.

-

Moved forward a year at school whilst failing to make sure he maintained friendships, rather than for example seeing his advanced analytical learning capabilities as an opportunity to take a year off to travel with family and develop his emotional intelligence.

-

After he skipped 6th grade he “began feeling a great deal of hostility toward many of my schoolmates, I developed a habit of trying to find ways of justifying my hatred in terms of my moral system ... One day when I was 13 years old, I was walking down the street and saw a girl. Something about her appearance antagonized me, and, from habit, I began looking for a way to justify hating her, within my logical system. But then I stopped and said to myself, ‘This is getting ridiculous. I’ll just chuck all this silly morality business and hate anybody I please’ Since then I have never had any interest in or respect for morality, ethics, or anything of the sort”

-

Parents/teachers/counselors failing to talk through his desire for escape in primitive life as a desire to escape bullying, plus a lack of classes offered in politics and philosophy.

-

Killed a small bird by crushing the bird in his hand because he felt embarrassed by the pity he felt for the bird. Ted felt this pity conflicted with his desire to live a primitive hunter-gatherer life. But, after killing the bird he instantly felt even more sick with pity.

-

Attended Harvard a year early without taking the time to travel and explore the world.

-

Unwittingly participated in psychological experiments at Harvard which were later used by the CIA to demonstrate the efficacy of torture. These experiments would be considered unethical today and could not take place.

-

Angry with himself for being unable to move from social interaction with women, to romantic or sexual involvement, he projected his feelings of inadequacy onto all women, blaming them for his frustration.

-

Inability to discuss his sexual fantasies of becoming a woman in order to get to be intimate with a woman to a councilor. Coming away with stronger suicidal ideation, and his feelings of desire to kill through a murder suicide. His shame at not being able to find a relationship turned into hatred at society for regimenting his life and making him this way.

-

Kaczynski showed a letter to his brother, parents and romantic interest that he planned ‘violence of a serious nature’ against the romantic interest who had broken off their romance, but no steps were taken to either get him help or report him. His journal entries later revealed that he brought a knife with him in a paper bag, to disfigure her face.

-

Kaczynski proposed founding an organization dedicated to stopping federal aid to scientific research, thereby preventing the “ceaseless extension of society’s powers. He sent this essay, similar to the manifesto he’d later write, to a few politicians. He would often write anti-technology essays to newspapers and favorite authors. If the FBI had put more focused callouts for information, then one of these people may have tipped off the FBI sooner.

-

Initially felt remorse about having crippled the arm of a man who was an airline pilot.

-

Felt remorseful a long time later about the innocent people he would have killed on an airliner he attempted to blow up, as well as the secretary of a computer scientist.

-

Felt remorseful a long time later about his sadism towards animals.

When did Ted first decide to become a terrorist?

There are three different dates that could be argued over for which was the most defining moment in time when Ted expressed a will and plan to terrorize people:

-

Humiliation at a therapists office (1967 – Aged 24)

-

An aborted terror attack (1971 – Aged 28)

-

The first mailbomb (1978 – Aged 35)

I think the first date in the list above fairly meets this standard. But, some might argue for example that the third date is the most accurate because it was the first time in which he actually followed through with a plan to do a terrorist act.

1. Humiliation at a therapists office (1967 – Aged 24)

Quoting the author Eileen Pollack:

Alone in his room, he was driven crazy by the sounds of the couple next door making love. Finally—and this is what broke my heart—Kaczynski decided to convince a psychiatrist to allow him to undergo the surgery and chemical treatments he thought would transform him into a woman, not because he was transgender, but because, as a woman, he might wrap his arms around himself and be held by someone female.

Kaczynski kept his appointment with the psychiatrist, only to realize he was going mad. Furious at a society that had pushed him to excel in academics at the cost of his ability to find love and connection to other human beings, he vowed to stop being such a good boy and learn to kill. Only later did he come up with an ideology that justified his murderous rage, lashing out at science and industrialization for destroying our environment, pressuring us to conform, depriving us of our privacy, and robbing us of our humanity.[20]

Quoting the court appointed mental health expert, Sally Johnson:

While at the University of Michigan he sought psychiatric contact on one occasion at the start of his fifth year of study. As referenced above, he had been experiencing several weeks of intense and persistent sexual excitement involving fantasies of being a female. During that time period he became convinced that he should undergo sex change surgery. He recounts that he was aware that this would require a psychiatric referral, and he set up an appointment at the Health Center at the University to discuss this issue. He describes that while waiting in the waiting room, he became anxious and humiliated over the prospect of talking about this to the doctor. When he was actually seen, he did not discuss these concerns, but rather claimed he was feeling some depression and anxiety over the possibility that the deferment status would be dropped for students and teachers, and that he would face the possibility of being drafted into the military. He indicates that the psychiatrist viewed his anxiety and depression as not atypical. Mr. Kaczynski describes leaving the office and feeling rage, shame, and humiliation over this attempt to seek evaluation. He references this as a significant turning point in his life.[21]

I think because he didn’t know how to have relationships with women, so he wanted to explore desires for women which he hadn’t had the space to learn to understand. I definitely don’t think it was out of any felt emergence that he was a woman. They’re called autoerotic fantasies, where you get turned on imagining how other people will view you in different situations, and it can be as common as when you’re imagining yourself in a situation where someone is admiring a specific item of clothing you’re wearing that makes you feel confident.

So anyway, he made an appointment to go see the university psychologist and at the last minute decided he didn’t want to talk about having a sex change or his sexual fantasies. And just said he was depressed instead.

Years later he would begin writing an autobiography as frustrations were reaching a pinnacle because he wanted to commit a murder-suicide and leave behind an explanation. Here’s how he explained the first desire to kill happened:

As I walked away from the building afterwards, I felt disgusted about what my uncontrolled sexual cravings had almost led me to do and I felt humiliated, and I violently hated the psychiatrist. Just then there came a major turning point in my life. Like a Phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope. I thought I wanted to kill that psychiatrist because the future looked utterly empty to me.

I felt I wouldn’t care if I died. And so I said to myself “why not really kill that psychiatrist and anyone else whom I hate.” What is important is not the words that ran through my mind, but the way I felt about them. What was entirely new was the fact that I really felt I could kill someone. My very hopelessness had liberated me. Because I no longer cared about death. I no longer cared about consequences, and I suddenly felt that I really could break out of my rut in life and do things that were daring, “irresponsible,” or criminal.

My first thought was to kill somebody I hated and then kill myself before the cops could get me. (I’ve always considered death preferable to long imprisonment.) But, since I now had new hope, I was not ready to relinquish life so easily. So I thought “I will kill, but I will make at least some effort to avoid detection, so that I can kill again.” Then I thought, “Well, as long as I am going to throw everything up anyway, instead of having to shoot it out with the cops or something, I will go up to Canada, take off into the woods with a rifle, and try to live off the country. If that doesn’t work out, and if I can get back to civilization before I starve, then I will come back here and kill someone I hate.”

What was new here was the fact that I now felt I really had the courage to behave “irresponsibly.” All these thoughts passed through my head in the length of time it took me to walk a quarter of a mile. By the end of that time I had acquired bright new hope, an angry, vicious kind of determination and high morale.

It’s not a question of preserving my life and health; getting out of the power of civilization has long since become an end in itself for me. By now I have practically lost all hope of ever attaining this end. There my happiness in my Montana hills is spoiled every time an airplane passes over or anything else happens that reminds me of the inescapability of civilization. Life under the thumb of modern civilization seems worthless to measure and thus I more and more felt that life was coming to a dead end for me and death began at times to look attractive—it would mean peace. There was just one thing that really made me determined to cling to life for a while, and that was the desire for—revenge—I wanted to kill some people, preferably including at least one scientist, businessman, or other bigshot. This actually was my biggest reason for coming back to Illinois this spring. In Montana, if I went to the city to mail a bomb to some bigshot, [driver’s name] would doubtless remember I rode the bus that day. In the anonymity of the big city I figured it would be much safer to buy materials for a bomb and mail it. (Though the death-wish had appeared, it was still far from dominant, and therefore I preferred not to be suspected of crimes.) As mentioned in some of my notes, I did make an attempt with a bomb—whether successful or not I don’t know. In making a second bomb I have only barely made a start…[22]

Quoting Ted:

I often had fantasies of killing the kind of people I hated — i.e., government officials, police, computer scientists, the rowdy type of college students who left their beer cans in the arboretum, etc., etc., etc.,[23]

2. An aborted terror attack (1971 – Aged 28)

In April, 1971 he planned to kill a scientist in person. Quoting from one of Ted’s journals:

My motive for doing what I am going to do is simply personal revenge. I do not expect to accomplish anything by it. Of course, if my crime (and my reasons for committing it) gets any public attention, it may help to stimulate public interest in the technology question and thereby improve the chances of stopping technology it is too late; but on the other hand most people will probably be repelled by my crime, and the opponents of freedom may use it as a weapon to support their arguments for control over human behavior. I have no way of knowing whether my action will do more good than harm. I certainly don’t claim to be an altruist or to be acting for the ‘good’ (whatever that is) of the human race. I act merely from a desire for revenge. Of course, I would like to get revenge on the whole scientific and bureaucratic establishment, not to mention communists and others who threaten freedom, but, that being impossible, I have to content myself with just a little revenge.

These days it is fashionable to ascribe sick-sounding motivations (in many cases correctly, I admit) to persons who commit antisocial acts. Perhaps some people will deny that I am motivated by a hatred for what is happening to freedom. However, I think I know myself pretty well and I think they are wrong.[24]

Ted left a note to his parents that felt like a suicide note:

[D]uring the fall of 1970 my brother set himself up in an apartment in Great Falls, Montana. He knew that I was still looking for land, and that winter he mentioned in a letter to our parents that he would be interested in going fifty-fifty with me on a piece of property if I cared to locate in his part of the country. My mother passed this information on to me and, about June 1971, I drove out to Great Falls and dropped in at my brother’s apartment.[25]

THE PROFESSOR’S MOTHER, a constant early riser, went downstairs one morning and caught him leaving.

“There’s a note for you on the table,” he said.

“Aren’t you going to say goodbye?” she said.

“It’s easier this way.”[26]

Quoting the book Hunting the Unabomber:

In his memoir, David recalled a frantic phone call from his parents, asking if he had been in contact with his brother.[27]

Quoting the podcast Project Unabom:

David: I didn’t have a telephone, I was a little averse to technology myself perhaps, or maybe wanting to isolate, but my landlord came to me and said, your father is on the line, he wants to talk to you. He says it’s urgent. So, I went to my landlord’s apartment and got on the phone with Dad and dad said have you seen Ted to his left?

Eric: Ted hadn’t let anyone know where he was going. But he had left a note that was vague reflective.

David: And in this note, he said don’t feel bad, you’ve been good parents. Don’t ever think you’re to blame, but I need to go. And my father and mother were concerned that it sounded like a suicide note. So, they said “well please let us know if you hear anything from Ted. Let us know right away ‘cause we’re really worried. He didn’t tell us he was going. He’s just gone and there’s this note.”[28]

Quoting one of Ted’s Journals:

CHRISTMAS DAY, 1972:

About a year and a half ago, I planned to murder a scientist—as a means of revenge against organized society in general and the technological establishment in particular. Unfortunately, I chickened out. I couldn’t work up the nerve to do it. The experience showed me that propaganda and indoctrination have a much stronger hold on me than I realized. My plan was such that there was very little chance of my getting caught. I had no qualms before I tried to do it, and thought I would have no difficulty. I had everything all prepared. But when I tried to take the final irrevocable step, I found myself overwhelmed by an irrational, superstitious fear—not a fear of anything specific, merely a vague but powerful fear of committing the act. I cannot attribute this to a rational fear of being caught. I made my preparations with extreme care, and I figured my chances of being caught were less than, say, my chances of being killed in an automobile accident within the next year. I am not in the least nervous when I get into my car. I can only attribute my fear to the constant flood of anticrime propaganda to which one is subjected. For example, murderers in TV dramas are always caught.[29]

We know that part of his impulse to live in the wild was to slip into anonymity, to depend on as few people as possible day to day, who could then suspect what crimes he was engaged in. But now the wilds took on the further character of being proving grounds for him to attempt to rid himself of the impulse to cherish human life in all his actions.

Either way, another major reason was an attempt to escape stressful social experiences around people who he didn’t understand.

He planned a few more times to kill people in person, but as far as we know, never went through with it:

Nov. 1 [1974]: I have dreamed about that Sandi girl a couple of times before, and I dreamed about her again last night ...

... After I awoke I felt for awhile very heavy and melancholy. That melancholy feeling was augmented from another source — as I mentioned before, things are pretty well ruined around here, and there are plenty of difficulties in the way of my getting that cabin in the far north — would still be plenty of difficulties even if I had lots of money. I am just sick of the burden of dealing with people and feel like taking to the woods and seeing how many people I can pick off with my rifle before the cops get me.[30]

OCT. 23, 1979

I am about to stash these notes in a hiding-place, so I will record now some things that I didn’t like to write here when the notes were not hidden. Before I left on my hike this summer I put sugar in the gas tank of one of [name]’s snowmobiles. So hopefully [name] will have some trouble with it this winter. When I went out on my hike this summer I was planning to lie in ambush by some roadside (dirt by-road) a long way from home and shoot some trail-bikers or other mechanized desecrators of the forest, without too much regard for consequences. But once I was out in the woods I started to reconsider, for two reasons. One was that once I was out in the woods I felt so good that I started to care about the future again—I wanted to have more years to spend in the woods. The other reason is that I thought of an excellent scheme for revenge on a bigger scale and didn’t want to screw it up by getting caught for something else before I had a chance to carry it out. Considering technological civilization as a monstrous octopus, the motorcyclists, jeep-riders, and other intruders into the forest are only the tips of the tentacles.

I was not really satisfied with striking at these. My other plan would let me strike perhaps not at the head, but at least much further up along the tentacles.[31]

3. The first mailbomb (1978 – Aged 35)

Fall 1977: Destroying another cabin

Quoting Ted:

Fall ‘77 I went to some cabins along Dalton Mountain Road. There was one pretention ‒ looking cabin still not finished on the inside. There was a small house‒trailer parked on the lot, immaculately furnished inside. I stole a rusty animal trap I found outside the cabin. Overcoming my earlier inhibition, I smashed most of the windows in the trailer, then reached inside with my rifle and smashed a Coleman lantern and 2 gas lamp fixtures. I smashed 6 pains on the cabin. At the cabin next door I shot a hole in a new line on a trailer. Then I got the hell out pretty quick, because all this was noisy of course, and close to the road.[32]

Prepared to start killing people

Following on from the above, in the Fall of 1977 Ted wrote:

As a result of indoctrination since childhood I had a strong inhibition against doing these things, and it was only at the cost of great effort that I overcame the inhibition. I think that perhaps I could now kill someone (and I don’t mean just set a booby trap having only a fraction chance of success), under circumstances where there was very little chance of getting caught. But I’m not sure I could, because often one’s brainwashing turns out to be stronger than one thought.

As for motivation: I hate the technological society because it deprives me of personal autonomy. The technological society may be in some sense inevitable, but it is so only because of the way technological society may be in some sense inevitable, but it is so only because of the way people behave. Consequently I hate people. (I may have some other reasons for hating some people, but the main reason is that people are responsible for the technological society and its associated phenomena, from motorcycles to computers to psychological controls. Almost anyone who holds steady employment is contributing his part in maintaining the technological society.) Of course the people I hate most are those who consciously and willfully promote the technological society, such as scientists, big businessmen, union leaders, politicians, etc., etc. I emphasize that my motivation is personal revenge. I don’t pretend to have any kind of philosophical or moralistic justification. The concept of morality is simply one of the psychological tools by which society controls people’s behavior. My ambition is to kill a scientist, big businessman, government official, or the like. I would also like to kill a communist.[33]

Quoting the podcast Project UNABOM:

… after years of escalating violence in Montana against property and one poor cow. He was ready.[34]

May 1978: Northwestern Security Guard Opens Mailbomb

Quoting forensic linguist, Donald Foster:

Ted Kaczynski chose his designated victims (those whose names he actually put on a parcel) by searching for them in academic reference works. … While Professor Smith of RPI was not widely published, nor well known in his field, nor known personally to Kaczynski, his name and field of expertise appear in a reference work called Dissertation Abstracts International (the DAI), a useful research tool containing a trove of information about newcomers to academic disciplines.

The DAI identifies “Edward John Smith (1966), RPI” as a computer and aerospace engineer with a pilot design for “Attitude Control” intended for guiding the pitch of large orbital spacecraft.

If there’s one phrase that Ted Kaczynski had hated since childhood more than any other (even “technological society”), it was “attitude control.” Edward John Smith, the “attitude control” engineer, was a perfect first target for Ted the Iceman, a.k.a. coolheaded logician Kaczynski.[35]

So, despite attitude control not having the same meaning here, perhaps the term caught his eye whilst searching through the catalogue for scientists advancing high-tech research. As he would write later:

All the university people whom we have attacked have been specialists in technical fields. (We consider certain areas of applied psychology, such as behavior modification, to be technical fields.) We would not want anyone to think that we have any desire to hurt professors who study archaeology, history, literature or harmless stuff like that. The people we are out to get are the scientists and engineers, especially in critical fields like computers and genetics.[36]

Writing in August after having arrived back at his cabin, Ted explained:

I came back to the Chicago area in May, mainly for one reason: So that I could more safely attempt to murder a scientist, businessman, or the like. Before leaving Montana I made a bomb in a kind of box, designed to explode when the box was opened. This was a long, narrow box. I picked the name of an electrical engineering professor out of the catalogue of the Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute and addressed the bomb — a package to him.

I took the package to downtown Chicago, intending to mail it from there (this was in late May, I think around the 28th or 29th), but it didn’t fit in mail boxes and the post-office package-drops I checked did not look as if they would swallow such a long package except in one post-office (Merchandise Mart); but that was where I had bought stamps for the package a few days before, so I was afraid to go there again because, going there twice in a short time, my face might be remembered.

So I took the bomb over to the U. of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, and surreptitiously dropped it between two parked cars in the lot near the science and technology buildings.

I hoped that a student ‒ preferably one in a scientific field ‒ would pick it up, and would either be a good citizen and take the package to a post office to be sent to Renssalaer, or would open the package himself and blow his hands off, or get killed.

I checked the newspapers carefully afterward but could get no information about the outcome of what I did ‒ the papers seem to report only crimes of special importance.

I have not the least feeling of guilt about this ‒ on the contrary I am proud of what I did. But I wish I had some assurance that I succeeded in killing or maiming someone.

I am now working, in odd moments on another bomb.[37]

Desires to go out in a Murder-Suicide

After the first bombing failed to maim or kill anyone, Ted doubled down on his commitment to try and kill again:

… my motives for writing these autobiographical notes.

I intend to start killing people. If I am successful at this, it is possible that, when I am caught (not alive, I fervently hope!) there will be some speculation in the news media as to my motives for killing (As in the case of Charles Whitman, who killed some 13 people in Texas in the 60’s). If such speculation occurs, they are bound to make me out to be a sickie, and to ascribe to me motives of a sordid or “sick” type. Of course, the term “sick” in such a context represents a value-judgement. I am not very concerned about the negative value — judgements that will be made about me, but it does anger me that the facts of my psychology will be misrepresented. For that reason I have attempted to give here an account of my own personality and its development that will be as accurate as possible.

Desire for self-expression. From my early teens, I have never had any strong desire to communicate with another another human being on an intimate level, or to “unload” any of my troubles by talking about them, except in 2 cases. One was when I was so desperately in love with Carol Wolman. The other has been over the last few months, after my desire for women was strongly brought to life by Ellen Tarmichael. This so strongly roused my life-long frustration at not being able to get a girl, that I wished very much that there were someone I could talk to about it.

So I partly relieved myself by writing about my past social life — or lack of social life, I should say....[38]

One thing that our society demands is that you have a recognized place in the system. By quitting my job [at Prince Castle Spice Packing Plant], I’ve made myself again an outcast, a good-for-nothing, a bum—someone whom “respectable” people can’t view without a certain element of suspicion. I can’t feel comfortable in this respect until I get away into the hills again—away from society. Besides, in quitting I feel as if I have signed my own death-warrant. Drifting along indefinitely in that job would have been the path of least resistance—and that, in a way, was the only thing remaining between me and the finish of everything. Now the path of least resistance is simply to go back to Montana, and once I’m there, I’ll kill, because, as I decided before I left Montana, if I ever went back there I’d have to kill, because I had too much accumulated anger over the inroads of civilization. I’m not likely to change my mind and go looking for another job—job hunting, going to sleep, and getting up for work again the next morning. (Maybe there would still be something better I could still strive for, some corner of the world where there’s still some wilderness, or other things, but again, I’m so terribly—tired—of struggling.)

For those reasons, I want to get my revenge in one big blast. By accepting death as the price, I won’t have to fret and worry about how to plan things so I won’t get caught. More over, I want to release all my hatred and go out and kill. When I see a motorcyclist tearing up the mountain meadows, instead of fretting about how I can get revenge on him safely, I just want to watch the bullet rip through his flesh and I want to kick him in the face when he is dying. You mustn’t assume from this that I am currently being tormented by paroxysms of hatred. Actually, during the last few months (except at a few times) I have been troubled by frustrated hatred much less than usual. I think this is because, whenever I have experienced some outrage (such as a low flying jet or some official stupidity reported in the paper), as I felt myself growing angry, I calmed myself by thinking—just wait till this summer! Then I’ll kill! Thus, what I’ve been feeling in recent months is not hot rage, but a cold determination to get my revenge. But I want to be in my home or hills in Montana, not here in the city. Death in the city seems so sordid and depressing. Death in these hills—well, if you have to die, that’s the place to do it! However, it would have been very tempting to just hang onto my job at Prince Castle indefinitely, even though I have nothing to look forward to.

The truth is, I don’t want to die![39]

A short note on Ted’s misleading answers to this question

In a June 1999 interview with Theresa Kintz, Ted talked about his political development in the following way:

I read Edward Abbey in mid-eighties and that was one of the things that gave me the idea that, ‘yeah, there are other people out there that have the same attitudes that I do.’ I read The Monkeywrench Gang, I think it was. But what first motivated me wasn’t anything I read. I just got mad seeing the machines ripping up the woods and so forth ...

The honest truth is that I am not really politically oriented. I would have really rather just be living out in the woods. If nobody had started cutting roads through there and cutting the trees down and come buzzing around in helicopters and snowmobiles I would still just be living there and the rest of the world could just take care of itself. I got involved in political issues because I was driven to it, so to speak. I’m not really inclined in that direction.[40]

And then in 2009 Ted answered the question; ‘How/when did you decide to bomb?’ like so:

It would take too much time to give a complete answer to the last part of your ninth question, but I will give you a partial answer by quoting what I wrote for my journal on August 14, 1983:

The fifth of August I began a hike to the east. … [I]t had been a long time since I had seen the beautiful and isolated plateau where the various branches of Trout Creek originate. … What I found there broke my heart. The plateau was criss-crossed with new roads, broad and well-made for roads of that kind. The plateau is ruined forever. The only thing that could save it now would be the collapse of the technological society. I couldn’t bear it. That was the best and most beautiful and isolated place around here and I have wonderful memories of it.

The next day I started for my home cabin. My route took me past a beautiful spot, a favorite place of mine where there was a spring of pure water that could safely be drunk without boiling. I stopped and said a kind of prayer to the spirit of the spring. It was a prayer in which I swore that I would take revenge for what was being done to the forest.

My journal continues: “[...] and then I returned home as quickly as I could because I have something to do!”

You can guess what it was that I had to do.[41]

However, Ted had already sent 7 bombs by this point, and as discussed earlier, had set off in his car with the plan to murder a scientist before he ever even moved to Montana. So, I think statements like these have contributed to a mythology around Ted that he was an ‘academic savant who rejected society to live in the wild, and only struck back at technology because of its continued encroachment on his wilderness life’. But obviously, the timeframe for Ted feeling lost and first planning to kill started long before that.

Interestingly, I think this archetypal mythologising is a mirror image of Euro-American narratives of the ‘last wild Indian and the noble savage’. The ‘noble savage’ is admired for starting out a Wildman fighting a justified war against his oppressors and who then becomes someone who could teach the white man his wisdom; whereas Ted is perceived by some as having gone in the opposite direction, of being someone who had all the capabilities and drive to become well accomplished academically early on in life in advanced society, but who chose to reject society to go into the wilds and fight a justified war.

Regardless of the truth or usefulness of these noble savage stories, when we see people who even vaguely resemble them, they are often very emotionally impactful because it’s a striking reminder on such an intuitive level that this fight to preserve wildlife habitat and low-impact ways of living are being lost. How we have failed to organize well-thought-out and sufficient resistance to the powers that bring about this environmental destruction.

Did Ted ever regret his actions?

I think at the beginning of his bombing campaign he thought taking ‘revenge’ on people and animals who annoyed him was simply a right owed to him as a ‘wild animal’. For example, he would lay traps to kill small animals like a flying squirrel keeping him up at night, then torture them slowly in order to ‘get revenge’ on these squirrels. So, I think targetting an airplane in the beggining of his bombing campaign reflected a personal desire to know that any time he would get annoyed at airplane noises where he lived, he could take some ‘comfort’ in the knowledge that he’d tried hard to take one down.

He later came to regret both these actions due to feeling it wasn’t well directed anger and unjustifiably involved harming innocents:

... we will say that we are not insensitive to the pain caused by our bombings.

A bomb package that we mailed to computer scientist Patrick Fischer injured his secretary when she opened it. We certainly regret that. And when we were young and comparatively reckless we were much less careful in selecting targets than we are now. For instance, in one case we attempted unsuccessfully to blow up an airliner. The idea was to kill a lot of business people who we assumed would constitute a majority of the passengers. But of course some of the passengers would have been innocent people-maybe kids, or some working stiff going to see his sick grandmother. We’re glad now that the attempt failed.

But even though we would undo some of the things we did in earlier days, or do them differently, we are convinced that our enterprise is basically right. The industrial-technological system has got to be eliminated, and to us almost any means that may be necessary for that purpose are justified, even if they involve risk to innocent people. As for the people who willfully and knowingly promote economic growth and technical progress, in our eyes they are criminals, and if they get blown up they deserve it.

Of course, people don’t kill others and risk their own lives just from a detached conviction that a certain change should be made in society. They have to be motivated by some strong emotional force. What is the motivating force in our case? The answer is simple: Anger. You’ll as why we are so angry. You would would do better to ask why there is so much anger and frustration in modern society generally. We think that our manuscript gives the answer to that question, or at least an important part of the answer.[42]

Series II, #5, p.130. I now (Feb, 1996) feel very sorry about the fact that, in a few cases, I tortured small wild animals (two mice, one flying squirrel, and one red squirrel, as far as I can remember offhand) that caused me frustration by stealing my meat, damaging my belongings, or keeping me awake. There are two reasons why I tortured them. (1) I was rebelling against the moral prescriptions of organized society. (2) I got excessively angry at these animals because I had a tremendous fund of anger built up from the frustrations and humiliations imposed on me throughout life by organized society and by individual persons. (As any psychologist will tell you, when you have no means of retaliating against whomever or whatever it is that has made you angry, you are likely to vent your anger on some other object.) When I came to realize that I had taken out on these little creatures the anger that I owed to organized society and to certain people, I very much regretted having tortured them. They are part of nature, which I love, and therefore they are in a way my friends even when they cause problems for me. I ought to reserve my anger for my real enemy, which is human society, or at least the present form of society. I have not tortured an animal for many years now. However I have no hesitation about trapping and killing animals that cause problems for me, at least if they are animals of the more common kinds.

Series II, #5, p.117. Here’s something that I remember pretty clearly about catching that rabbit alive; I don’t know why I didn’t mention it in my notes. In pulling the rabbit out, I tore loose a large patch of his skin (snowshoe hares! Skins are very fragile). I had wanted to let the rabbit go, from pity, but I was afraid that I might be doing it a disservice if I let it go, because the wound probably was very painful, and with so much of its body deprived of fur the rabbit might die of cold anyway.[43]

In prison Ted felt that he had hardened and experienced even less regrets as a result of the prison situation he had ended up in:

Probably the biggest reason why you find my actions incomprehensible is that you have never experienced sufficiently intense anger and frustration over a long enough period of time. You don’t know what it means to be under an immense burden of frustrated anger or how vicious it can make one.

Yet there is no inconsistency between viciousness toward those whom one feels are responsible for one’s anger, and gentleness toward other people. If anything, having enemies augments one’s kindly feelings toward those whom one regards as friends or as fellow victims.

Do I feel that my actions were justified? To that I can give you only a qualified yes. My feelings at a given time depend in part on whether I am winning or losing. When I am losing (for example now, when the system has me in jail) I have no doubts or regrets about the means that I’ve used to fight the system. But when I feel that I’m winning (for example, between the time when the manifesto was published and the time of my arrest), I start feeling sorry for my adversaries, and then I have mixed emotions about what I’ve done.

Thomas Mosser, for instance, was a practitioner of what I consider to be the slimy technique of public relations, which corporations and other large organizations use to manipulate public opinion, but it does not necessarily follow that he was ill-intentioned. He may simply have felt that the system as it exists today is inevitable, and that he could accomplish nothing by going into another line of work. And of course his death hurt his wife and children, too.

I suppose that to sympathize with my actions one has to hate the system as I hate it, or at least one has to have experienced the kind of prolonged, frustrated anger that I’ve experienced. I think you have the good fortune never to have gone through anything like that.[44]

Later in a partially available letter, making a reasonable guess as to what the missing page contained, he wrote:

[‘As for if I had the opportunity to kill Gilbert Murray again, I would have’] no more compunction than I would have in squashing a cockroach.* Yet Judy Clarke thinks the Murrays were just wonderful people....

* In contrast, I take very seriously the suffering that David Gelernter underwent. Gelernter is no cliche, but a highly intelligent, thoughtful, talented, and sensitive man whom no one could describe as a mere stereotype. I consider that he deserved what he got, but that is a judgement that I do not adopt lightly and it is one about which I have mixed feelings.[45]

Finally, in a letter to his lawyers, Ted wrote:

As for winning the sympathy of a jury, bear in mind some of the things that my early (1970’s) writings indicate: indiscriminate, homicidal hostility toward society in general, not just toward the corporate-governmental technological elite; I hunted game illegally and in a few cases even wasted meat; in a few cases I tortured small animals that had made me angry.[46]

Did the CIA turn Ted into a terrorist?

Quoting Ted’s Wikipedia page:

In his second year at Harvard, Kaczynski participated in a study described by author Alston Chase as a “purposely brutalizing psychological experiment” led by Harvard psychologist Henry Murray. Subjects were told they would debate personal philosophy with a fellow student and were asked to write essays detailing their personal beliefs and aspirations. The essays were given to an anonymous individual who would confront and belittle the subject in what Murray himself called “vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive” attacks, using the content of the essays as ammunition. Electrodes monitored the subject’s physiological reactions. These encounters were filmed, and subjects’ expressions of anger and rage were later played back to them repeatedly. The experiment lasted three years, with someone verbally abusing and humiliating Kaczynski each week. Kaczynski spent 200 hours as part of the study.

Some sources have suggested that Murray’s experiments were part of Project MKUltra, the Central Intelligence Agency’s research into mind control.[47]

Quoting a CIA officer, Glenn Carle:

I was a career operations officer in the CIA, who became involved, for a time, in the interrogation of one of the top members, we believed, of Al-Qaeda. And thereby was involved for that time, in the enhanced interrogation program, which is torture and is mind-altering procedures. My experiences, tragically, are directly relevant to the experience Kaczynski went through because the methods used by the CIA were directly derived from — not just inspired by — what Murray was trying to do in the ‘50s and early ‘60s. And that is that you can break somebody down and you can alter their mind. The theory was, you will be psychologically broken down and dislocated so that you can then be reformed as a cooperative source.[48]

Michael Sperber:

As a student, Kaczynski in 1959–62 participated in psychological research on the subject of stress devised by Professor Henry A. Murray of the Department of Social Relations. Murray, researching two-person interactions (the “dyad”), described the experimental procedure in American Psychologist (1963):

First, you are told you have a month in which to write a brief exposition of your personal philosophy of life, an affirmation of the major guiding principles in accord with which you live or hope to live your life. Second, when you return to the Annex [Murray’s workshop] with your finished composition, you are informed that in a day or two you and a talented young lawyer will be asked to debate the respective merits of your two philosophies.

Murray did not tell the research subjects that they would be debating an aggressive lawyer who was instructed to surprise, deceive, and ridicule them, disputing the respective merits of their philosophies. A biographer of Kaczynski at Harvard wrote:

As instructed, the unwitting subject attempted to represent and to defend his personal philosophy of life. Invariably, however, he was frustrated, and finally brought to expressions of real anger by the withering assault of his older, more sophisticated opponent while fluctuations in the subject’s pulse and respiration were measured on a cardiotachometer.

It is difficult to imagine a better way to humiliate, disrespect, and discredit another human being than by invalidating his or her philosophy of life, the major guiding principles by which that person lives. Kaczynski, however, denied that Murray’s experiments had any important effect on his psyche:

I experienced a lasting resentment of Murray and his co-workers. This resentment was not primarily due to the “dyadic disputation” that Chase makes so much of. What I mainly resented was the fact that I had been talked into participating in studies that involved extensive invasion of my privacy—and by people whom I disliked personally. I am quite confident that my experiences with Professor Murray had no significant effect on the course of my life.[49]

Quoting Ted:

Actually there was only one unpleasant experience in the Murray study; it lasted about half an hour and could not reasonably have been described as “traumatic.” Mostly the study consisted of interviews and filling out pencil-and-paper personality tests. The CIA was not involved.

About 15 or 20 years ago a TV journalist named Chris Vlasto … looked up some of the other participants in the study and found that nothing had happened that was worth reporting in the media…[50]

Quoting an author, Michael Sperber:

Perhaps the impact of Murray’s deliberately disrespectful encounters had more of an effect on Kaczynski’s psyche than he realized. He told a court-appointed psychiatrist, Dr. Sally Johnson, who conducted competency hearings prior to his trial in 1998, that while he was at the University of Michigan, where he was studying for a doctoral degree in mathematics, he began having nightmares, which continued for several years:

At the age of 19 I began having nightmares (3 or 4 times a year?) that were accompanied by a strange aura of fear and disgust.[51]

Quoting from one of Ted’s Journals:

In the dream I would feel either that organized society was hounding me with accusation in some way, or that organized society was trying in some way to capture my mind and tie me down psychologically or both. In the most typical form some psychologist or psychologists (often in association with parents or other minions of the system) would either be trying to convince me that I was “sick” or would be trying to control my mind through psychological techniques. … I would grow angrier and finally I would break out in physical violence against the psychologist and his allies. At the moment when I broke out into violence and killed the psychologist or other such figure, I experienced a great feeling of relief and liberation.[52]

Ted writing from prison:

During my sophomore year I was talked into becoming a participant (against my better judgment) in a psychological study directed by the late Professor Henry A. Murray. Along with a couple of dozen other Harvard students, over a period of almost three years I went through a series of interviews and filled out many questionnaires. My brief 1959 autobiography was written for Murray’s group. The assessment arrived at by the psychologists would be very useful in determining how people saw my personality, but up to the present (March 14, 1998) the Murray Center at Radcliffe College has refused to release any of the psychologists’ conclusions to my attorneys; and most of the individual psychologists involved have declined to cooperate with the investigators, who to my knowledge have obtained no information concerning any conclusions that were drawn about me. One wonders whether the Murray Center has something to hide. Anyway, all I know at the moment about the psychologists’ conclusions is that I was included in an “ideologically alienated” group that was discussed by Kenneth Keniston in his book The Uncommitted.

“One of the psychologists who participated in [the Murray] study, and who interviewed me a few times, was a youngish instructor who lived at Eliot House. He was a member of the house master’s inner clique. Two or three times when I met him at Eliot House I said ‘hello’. In each case this psychologist answered my greeting in a low tone, looking off in another direction and hurrying away as if he didn’t want to stop and talk to me. I’ve thought this over, and the only half-way plausible [explanation I can think of for this behavior] is that this man didn’t want to be seen socializing with someone who wasn’t dressed properly and wasn’t acceptable to the clique of which he was a member.”[53]

Ab. Autobiog of TJK 1959. This is a brief autobiographical sketch that I wrote, probably in the fall of 1959, for Professor Henry A. Murray as part of a psychological study in which I participated. Its trustworthiness is impaired by the fact that I resented having been talked into participating in Murray’s study and therefore tried to avoid revealing too much about my inner self. I tended to downplay problems rather than speaking about them frankly; specifically, I understated the problems I had during adolescence with my parents and my school mates.[54]

Quoting from the documentary Unabomber: In his own words:

RECORDING: (Researcher #1:) Please begin your discussion when you hear the buzzer sound, alright? (Researcher #2 [Mr. C.]:) Just give me a second. Do you think we ought to decide how we’re going to go about it or… (Kaczynski:) I suppose it’s supposed to be a spontaneous discussion (laughs)

SASHA: This experiment basically was an experiment run by Henry Murray, At the Harvard psych department. But when it comes to these interviews with Ted, the files are sealed. You can’t get access to them.

RECORDING: (Mr. C.:) I ought to warn you before I start this, that I was not… I do not have a very favorable impression of you as a result of reading your philosophy. But, let me just tick off a few preliminaries and then we’ll get into what I really didn’t like.

SASHA: What we do know for certain is that Henry Murray was looking into the effects of stress on human beings, specifically he was looking at interrogation strategies and techniques and how human beings are able to kind of be resilient to aggressive interrogative tactics.

RECORDING: (Mr. C.:) First, I mean, in spite of the fact that you’ve explained this subjective reality, I mean I think this is essentially an asinine point of view. (Kaczynski:) Yeah.

FORREST: Murray subjected them to harsh critiques of their ideas and he was very interested in seeing how they responded, how they performed when there was really a stressful situation.

ROY: Ted was told he was gonna be debating political philosophy with a fellow student. How tempting that would have been.

SASHA: It was not a debate. It was a full-on aggressive attack of Ted as a human being, as Ted as an intellect.

FORREST: You couldn’t do those experiments today. But you certainly could in 1958 to 1962. There was nothing at the time of an objection to what Harry was doing. It was simply taken for granted that that was how you had conducted research of that kind.

DAVID: Ted was deceived. He didn’t know that this person had a script and the person’s objective was to humiliate and traumatize him.

Colin A. Ross M.D. — Author of ‘The CIA Doctors’

COLIN: Henry Murray was a very high ranking academic, very successful career with well established expertise in interrogations. And he was very involved in developing interrogation techniques for the OSS, which is the Office of Strategic Services. The Second World War precursor of the CIA. So, interrogation, as we all know, is questioning somebody to try and find out, Did they commit a crime? Enhanced interrogation is when you add on all these mind control methods, drugs, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, sensory isolation, good cop/bad cop techniques. Whatever you could dream up to try and get something out of somebody.

FORREST: Henry Murray was not an evil scientist. There are some plausible arguments to be made that he had some connections with the CIA. But he was very proud of his service to the country and took working with the CIA, if he did, as part of that responsibility, he was a responsible citizen. And the country needed good assessment of personnel. So, he could provide that better than anyone else could.

Glenn Carle — Former CIA Officer