Joshua Farrell-Molloy

From blood and soil to ecogram

A thematic analysis of eco-fascist subculture on Telegram

1. Introduction: The renewed relevance of Eco-fascism

2.1. Defining and understanding Eco-fascism

2.2. Eco-fascism online: existing work

Prominent figures associated with eco-fascism

3.1. Aims and justification of methodology and case study

3.4. Ethics and research safety considerations

4.1. Outlining eco-fascism: nature, outgroups/ingroups and militancy

GUID: 2571784F

Trento ID: 225124

CU ID: 93557873

Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of International Master in Security, Intelligence and Strategic Studies

Word Count: 21987

Supervisor: Dr.Vit Stritecky

Date of Submission: August 10th 2022

Front Matter

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Allison, my parents and all those who have supported me.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Bucolic landscape in France

Figure 2. Isolated cabin in nature

Figure 3.Tree depicting ‘human eyes’

Figure 4.“Nature is my Church”

Figure 5. Algiz rune

Figure 6. Sonnenrad as a rising sun

Figure 7. Sonnenrad moon

Figure 8. ‘Nature as

Figure 9. “Protect nature”

Figure 10. Antisemitic violence

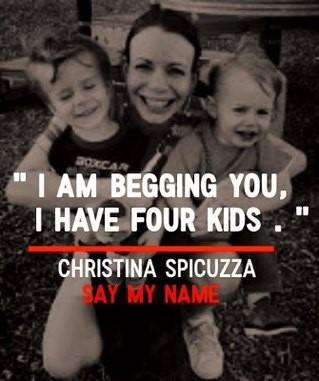

Figure 11. Christina Spicuzza

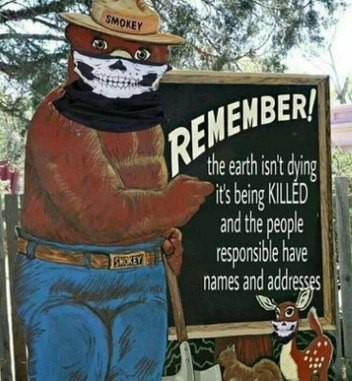

Figure 12. Siege-culture edited ‘Smokey Bear’ mascot

Figure 13. Burning substation

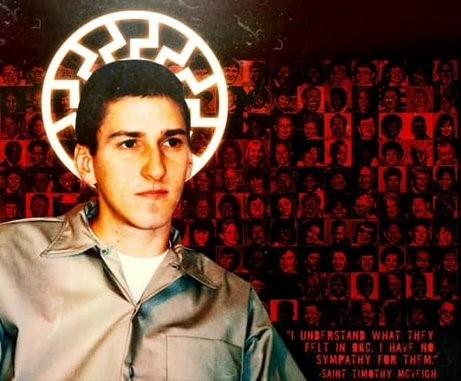

Figure 14. ‘Saint’ McVeigh

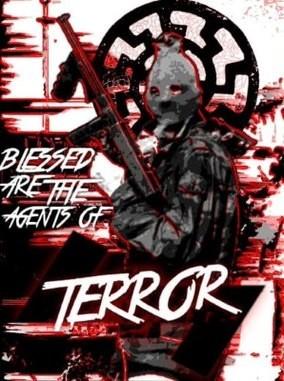

Figure 15. Terrorwave

Figure 16. Siege IRA

Figure 17. Kaczynski “Defend The Wild”

Figure 18. Kaczynski in Siege-culture skull mask

Figure 19. Kaczynski quotes

Figure 20. “Saint Ted”

Figure 21. Kaczynski: “I speak for the trees”

Figure 22. Smashed computer

Figure 23. “Stay forever”

Figure 24. “Return to Nature and Beauty”

Figure 25. SS flag alongside harvest of chicken eggs

Figure 26.“Reject the concrete jungle, come home to nature and beauty”

Figure 27.“Goin back to a simple life […]”

Figure 28. Cottagecore male gaze

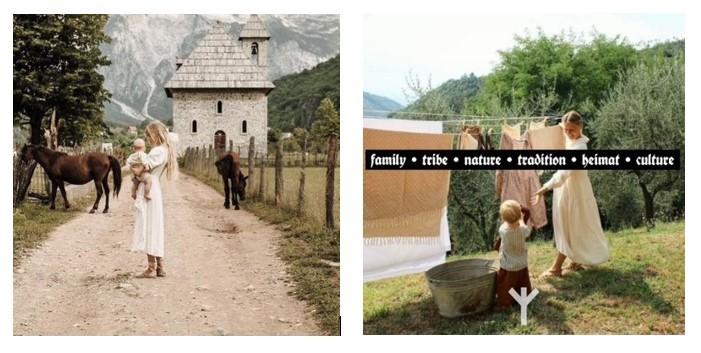

Figure 29. Tradwife

Figure 30. Ancient warrior

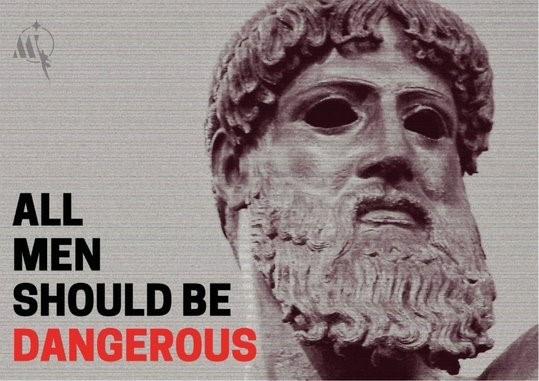

Figure 31. Zeus: “All men should be dangerous"

Figure 32. Lyndon McLeod

Figure 33. ‘Great Reset’

Figure 34. Raw Milk

Figure 35. Pure raw masculinity

Figure 36. Folk art illustrations

Figure 37. Woman wearing deer antlers

Figure 38. Gnomecore

Figure 39. "Make Europe Pagan Again"

Figure 40. Utopian eco-fascist imaginary.

1. Introduction: The renewed relevance of Eco-fascism

Climate change is here, and its effects are already being felt across the world. The future looks bleak, with extreme weather events, rising sea levels, increased global instability, crop failures, water scarcity and the risk of millions of climate migrants, all of which has the potential to exacerbate another growing problem: the rise in far-right extremism.

In this context, the concept of eco-fascism has become the focus of renewed attention in both scholarly work as well as mainstream media coverage, spurred on by two developments. First, an emergence of online far-right communities expressing environmental views. Secondly, three high-profile terrorist attacks carried out by individuals declaring themselves as eco-fascist.

In March of 2019, in Christchurch, New Zealand, White supremacist Brenton Tarrant murdered 51 Muslim worshippers during a livestreamed shooting attack at two mosques. In his manifesto, ‘The Great Replacement’, Tarrant showed his obsession with birth-rates and demography, as he claimed that immigration was functioning as a form of “environmental warfare” (Darby, 2019) endangering white ethnic autonomy. Tarrant further expressed that he wished to “ensure the existence of our people and a future for white children, whilst preserving and exulting nature and the natural order” (Campion, 2021), declaring there was “no nationalism without environmentalism” (Darby, 2019).

Nearly five months later in the US, Patrick Crusius, who claimed to have been directly inspired by Tarrant, killed 22 people during a shooting attack targeting Latinos at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas. In his manifesto, ‘An Inconvenient Truth’, Crusius referenced Al Gore’s 2006 documentary of the same name about climate change. Crusius also blamed immigrants for environmental degradation (Owen, 2019) and advocated for mass population control, stating that “If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can become more sustainable (Achenbach, 2019).

Finally, on May 14, 2022, 18-year-old Payton Gendron murdered ten African Americans and wounded three others in a live-streamed shooting attack at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York (Amarasingam, et.al, 2022). In his 180page manifesto, he referred to himself as an eco-fascist and plagiarised sections of Tarrant’s manifesto including passages in which he expressed ideas linking immigration to environmental degradation while also quoting a section from Ted Kaczynski’s 1995 manifesto ‘Industrial Society and its Future’. Kaczynski is a popular figure among eco-fascists. (Farrell-Molloy and Macklin, 2022).

These attacks and manifestos led to dozens of special features on ecofascism in the media, including numerous explainer pieces providing an overview of what to most people appeared to be two irreconcilable and contradictory ideas: environmentalism and fascism (Ajl, 2019; Bennett, 2019; Black, 2019; Corcione, 2020; Kaufman, 2019; Lawrence, 2019; Lennard, 2019; Sparrow, 2019; Wilson, 2019). In tandem, the attacks inspired a steady flow of new research aimed at exploring and understanding eco-fascism, from historical accounts of the relationship between fascism and environmentalism (Campion, 2021) to warnings against fascist entryism into green movements (Ross and Bevensee, 2020).

If far-right environmentalism is understood to be a possible major threat of the future (Rettman, 2022), then digital enclaves where adherents congregate must be understood fully. While eco-fascism is not necessarily a cohesive ideological movement, the Ecogram subculture is where environmental thinking is most concentrated within the far-right. Understanding what the main topics and themes are within this group is crucial to understanding not just ideological underpinnings, but how dominant narratives could potentially react to coming climate shocks and trends in far-right violence.

In this sense, this dissertation aims to identify which key themes emerge within eco-fascist subculture discourse on Telegram and, where possible, situate these themes within a distinct eco-fascist ideological framework or militant accelerationist subculture. The analysis will incorporate all formats, from text posts to files and visual content. Particular attention will be paid to distinct ideological tendencies, their construction of masculinity and engagement with spirituality to measure the salience of certain values and beliefs held by the community.

The following chapters will address the topic at hand, first, by conducting a literature review on eco-fascism. Second, by detailing the methodology used for the analysis. Third, by describing the findings after the thematic analysis and, at lastly, stating the conclusions, limitations, and suggestions for further analysis on the field.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining and understanding Eco-fascism

Eco-extremism has historically been regarded as an issue far-left actors are most likely to be preoccupied with (European Commission Directorate General for Migration and Home Affairs, 2021). From the use of ‘monkeywrenching’ sabotage tactics against machinery by early ‘Earth First!’ activists from the early 1980s onwards (Taylor, 1998), to the use of arson by the much more radical Earth Liberation Front, a radical offshoot born out of the milieu of far-left and anarchist activists frustrated with the ineffectiveness of Earth First! tactics (Loadenthal, 2013), the eco-extremism landscape been dominated by far-left activists while eco-terrorism was typically characterised by a principle of non-violence towards people (Foreman and Abbey 1993, Leader and Probst, 2003). Although high profile cases of equipment and infrastructure sabotage still occasionally continue to take place (Cecco, 2022; Flock, 2021), the number of violent eco-extremist attacks and incidents has generally been steadily declining (Izak, 2022).

Nonetheless, while eco-fascism's place in the spotlight may be recent, it must be noted that ecology and racism have often intersected with one another throughout history. From early colonial nature management practices (Moore and Roberts, 2022) to the emergence of thinkers such as Thomas Malthus, whose ideas on population growth were used to argue against providing aid during the Irish Famine, to eugenicists like Madison Grant and Ernst Haekel, there is long tradition of thinking in relation to the environment and population and race. In fact, the founding fathers of environmentalism and conservationism in the US often harboured racist or eugenicist views, dehumanising the indigenous population (Brave, 2019).

More recently throughout the 20th century, the Nazi Germany notion of ‘Blood and Soil’ (Staudenmaier, 2011) denoting a mystical connection between race and nature, promoted a form of traditional agrarian romanticism alongside a strong sense of anti-urbanism. The roots of Blood and Soil came in part from the völkisch movement, which had emerged in late-19th century Germany as a ''response to modernity'' and the dislocations produced by industrial capitalism, promoting the simplicity and harmony of an idealised rural life.

After the Second World War, this theme of anti-modernity continued to be carried forward by pre- and war-time fascist thinkers such as Julius Evola, while other key figures within eco-fascism include Savitri Devi, who incorporated animal rights advocacy into her Nazism (Macklin, 2022). Far-right actors attempted entryism into ecological groups during and after the Cold War, with several far-right attempts to infiltrate and gain hegemony within modern green movements across Europe and the US (Ross and Bevensee, 2020).

In recent years, identarian and far-right activists have started engaging in ‘clean-ups’, collecting litter from the countryside or embarking on group hiking trips (Owen, 2022). The promotion of these activities online from these groups is becoming increasingly common. One such post on New Zealandbased far-right group Action Zealandia’s website features members hiking in a forest with the caption: “Spending time amongst nature is vitally important, especially in times where we live so wholly disconnected from the natural laws of the world” (Action Zealandia, 2020), highlighting an expressed need to reharmonise with the land. While other ethno-nationalist far-right parties, such as the Ireland-based National Party have also held clean-up events in the Irish countryside (An Páirtí Náisiúnta, 2022), declaring that nationalism and environmentalism “go hand in hand”. While these activities do not constitute eco-fascism and can perhaps be best characterised as forms of far-right ecologism, they represent a growing trend and present spaces in which ecofascist ideology could potentially grow into.

To date, much of the scholarship on the ecology and right-wing politics nexus can be regarded as a mostly definitional debate. Alternative labels to ecofascism have emerged from nationalism studies such as “right-wing ecology”, proposed by Olsen (1997) to describe the nature and nationalism nexus in late1990s Germany. Olsen’s concept referred to an environmentalism which rejected enlightenment universalism. It was understood as setting human beings within a nature that determined them and holding the belief lessons of ecology and the laws of nature applied to the social world. While left-wing ecologists would feel a shared sense of humanity, right-wing ecologists view people as divided by natural differences and rooted in homelands, which meant that constructing a sense of natural rootedness within right-wing spaces could quickly evolve into politics of exclusion.

Another label to describe the nature-fascism nexus was Huq and Mochida’s “environmental fascism” (2018), which encompassed the resurfacing of the bio-politics associated with the ‘Blood and Soil’ notions of Nazi Germany, but later became appropriated by the far-right to describe what was viewed as the over-zealous environmental protections brought by mainstream environmentalists. Huq and Mochida argued for reappropriating the label to describe emerging environmental policies based on the assumption that nature should be open to be exploited for exclusive white nationalist interests.

In contrast with these previous labels, the term “Eco-fascism” has become more broadly popular and often constitutes our understanding of farright environmentalism today. It has been defined in its simplest form by Amend, as “The devaluing of human life—particularly of populations seen as inferior—in order to protect the environment viewed as essential to White identity” (Amend, 2020).

Within the eco-fascist ideology, overpopulation in the Global South is blamed for the over-use of natural resources and increased pollution. Immigration to White homelands is held responsible for the further despoiling of the environment in the West. Drastic depopulation through mass murder and a halt on immigration is thus hailed as a solution to the climate crisis, with what Naomi Klein has termed “environmentalism through genocide” (Corcione, 2020). In this regard, and as outlined by Wegener (2021), eco-fascism aligns with “The Great replacement” theory in there is a preoccupation with ‘native’ white demographics and a construction of non-white migrants and the elites, often characterised as Jewish, as conspiring to undermine the white race.

Campion (2021) has made the most valuable contribution to developing a proper definition of eco-fascism. She considers eco-fascism a “sub-form of fascism”, rather than a merger between environmentalism and fascism. She advances the definition of eco-fascism as a “reactionary and revolutionary ideology that champions the regeneration of an imagined community through a return to a romanticised, ethnopluralist vision of the natural order” (p.2). To do this, ecofascists imagine a romanticised past that emphasizes a sense of natural ecological harmony between populations deemed to be native and rightfully entitled to the land. Modernity, immigration, urbanisation and multiculturalism are all deemed to be disruptive forces which shatter this harmony and the only way to repair it is to return to the land, to nature and restore the purely natural order which excludes those deemed to be non-natives. Her definition focuses on the past and emphasises the feeling of rootedness.

While Lubarda (2020), has proposed using the ‘Far-right Ecologism’ framework to account for the complexity of the interaction between the far-right and ecologism, for this thesis, the term eco-fascism will be used for several reasons. Firstly, despite confusion and disagreement over what label is most appropriate and which definition best describes eco-fascism, the author considers Campion’s (2021) definition as the most well-developed attempt to describe the tendencies present within the eco-fascist subculture on Telegram. The thematic analysis which will aim to both characterise the community while testing her definition and potentially building upon it with further findings.

Secondly, while eco-fascism may have conceptual deficiencies as a label, and terms such as far-right ecologism may better describe broader phenomenon including white nationalist co-option of environmental causes, for the sake of the distinct fringe subculture which is the subject of this study, ecofascism is the most suitable term. This investigation of the community is not an attempt to understand how the broader radical right interacts with the environment, but to understand this small community and distinct subculture on a deeper level.

Thirdly, the author agrees with Moore and Roberts’ (2022) belief that the label eco-fascism can also serve as a warning of what potential future movements may arise in the years ahead and characterizes some of the possibilities that could materialise as the climate crisis worsens. So, while the label eco-fascism does not account for broader environmentalist tendencies among the far-right, it is an appropriate label to describe what is currently the most extreme manifestation of far-right ecology in existence. Hence, when anticipating the possible far-right environmentalist threats of tomorrow, this community offers a valuable starting point for analysis.

2.2. Eco-fascism online: existing work

While in previous years the scholarship regarding eco-fascism mostly consisted of a definitional debate, early media articles offered the first at Ecofascist communities online. Manavis’ (2018) New Statesman article reported on the emergence of an online community of “nature-obsessed, antisemitic, white supremacists” on Reddit and Twitter, who believed racial purity was necessary to avoid environmental catastrophe and deployed a visual culture steeped heavily in Nordic rune symbols, nature landscapes and Norse mythology.

Likewise, Hanrahan (2018) observed the emergence of so-called ‘Pine Tree Twitter’, a loose subculture made up of a mixture of followers of Unabomber ‘Ted Kaczynski’ who used pine tree emojis in their usernames and bios to identify one another and were suggested to have first emerged shortly after the airing of the 2017 series Manhunt: Unabomber, about the FBI hunt to catch Kaczynski (although several of the Pines dispute their arrival was anything to do with the release of the series) (Redux, 2018). The Pine Tree community was noted to be made up of self-declared “primitivists” and “neoluddites”, but had increasingly included “eco-fascists”, influenced by Finnish deep ecologist Pentti Linkola.

The article provided the genesis for Hughe’s (2019) qualitative analysis of the Pine Tree community, with an examination of 100 randomly sampled Pine Tree Twitter accounts. He identified five micro-cultures across Pine Tree Twitter: ‘Skullmasks’ who deployed a visual grammar and aesthetic associated with neo-Nazi ‘Siege-culture’ groups, ‘Ted Gang’, meaning those who idolized Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, and three other groups associated with Christian orthodoxy, paganism and occultism and those who used 4chan and 8chan iconography, representing a broad coalition of online subcultures. However, as Hughes himself noted, a major shortcoming of the study was that in only focusing on the community on Twitter, an insight the most extreme far-right apocalyptism from those such as Atomwaffen or the Base, who are best observed on encrypted messaging apps such as Telegram, was missing.

Journal publications examining the eco-fascist subculture on Telegram were scant, no doubt due to its somewhat fringe status. When far-right communities on Telegram were studied, ecofascist subcultures were never the focus. It can be argued that the ecofascist community’s lower profile allowed their “in” crowd language, visual cues and symbols to escape scrutiny and algorithm removal on mainstream platforms (Walther and Mccoy, 2021).

In this sense, Shajkovci’s (2020) profile on the online movement of the now-deleted official Pine Tree Party Telegram channel was illustrative for the purposes of providing an overview of the origins of the movement. Yet, a deeper understanding of contemporary eco-fascism requires understanding the main narratives and themes across the broader subculture and community which have since emerged and remained persistent.

A recent article has provided the most valuable contribution towards examining Ecogram. Hughes (et.al, 2022) examined eco-fascist communities on Telegram and Twitter and demonstrated the distinctness of their subculture from other far-right communities. They concluded the eco-fascist subculture departed from Siege-culture mostly in their approach to gender, eco-fascists tended to portray white women as idealised mothers who needed to be protected, as opposed to the violence and vulgarity shown towards women in Siege-culture, which has spawned Telegram channels with names such as Rapewaffen (Hermansson 2020).

Despite Hughes (et.al, 2022) study as the most significant contribution to understanding the eco-fascist subculture on Telegram. It must be noted that their analysis is limited to only visual material, the discounting of other content such as text posts, and files that were shared limits the ability to detect prominent patterns of discourse. Likewise, it limits the ability to contextualise certain themes, as text posts can provide valuable insights into the salience or construction of values. Additionally, while their analysis of key thinkers provides another key contribution, in illuminating the centrality of Kaczynski to eco-fascist identity, the context of his thematic presence is not described or explored in detail, missing a valuable opportunity to explore the largest point of cohesion among the eco-fascist subculture.

Loadenthal (2022) contributed to filling this gap with an examination of discourses formed by accelerationist eco-fascists in visual and text-based communications on Telegram. He highlights the ideological convergence of fascism associated with neo-Nazi James Mason with the anti-technology ideas of figures such as Ted Kaczynski. However rather than conducting a broader thematic analysis of the eco-fascist subculture to contextualise the ecosystem in which Kaczynski is worshipped; Loadenthal's analysis instead focused more narrowly on the articulation of an eco-fascist strategy aimed at exacerbating tensions within systems which uphold the socio-political and economic orders, such as posts which advocated for targeted strikes against infrastructure and technological systems.

Finally, two additional MA dissertations have examined eco-fascism on Telegram. Smith (2021) analysed circulatory networks of ecofascist discourses and how rhetoric and arguments of eco-fascism were developed within digital enclaves and tactically bridged to broader audiences. In doing so, he concluded that while eco-fascist rhetoric and discourse differed across platforms, they were bound together by messaging that fascism is inherent within nature. He further examined multiple case studies including Twitter and 4chan and devoted a chapter to ecofascist memetic communication on Telegram, describing Telegram as a “space for the avant-garde of far-right environmentalism” (p.22). Likewise, his research focused on the use of memes which appropriated the Dr. Seuss character “The Lorax” as a messaging device in eco-fascist propaganda and the promotion of ‘seed bombing’ tactics in another channel. However, his analysis of the Ecogram community was limited to just these two artefacts, taken from only two ecofascist channels.

The second thesis, authored by Heinrich (2021), asked how emotional resonance emerged in far-right content that aimed to incite violence within Ecogram, concluding they established connections between framings and the context of environmental degradation. Heinrich extracted five values from Lubarda’s (2020) Far-right Ecologism framework: Naturalism, Spirituality and Mysticism, Authority, Organicism and Autarky, and Nostalgia and Manicheanism, mapping them on to the core framing tasks of frame analysis, diagnostic framing, prognostic framing or both. However, in using the FRE framework to select and collect her data, her analysis was narrow and failed to examine the community more broadly. Likewise, as outlined by Hughes et.al (2022), the eco-fascism subculture as it exists on Telegram can be distinguished from Lubarda’s (2020) FRE framework.

Furthermore, as she noted when reflecting on potential limitations of her study, images featuring expressions of masculinity were noted to have often appeared during her analysis, as were images of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. Neither of these topics/themes, which account for a significant bulk of ecofascist content, were explored due to the nature of her study, which only selected data based on it meeting the criteria of the FRE framework.

Guided by the above-mentioned scholarship and aware of the existing gaps in the literature, this dissertation will seek to conduct a wider thematic analysis that allows a deeper exploration of these very important themes to the eco-fascist subculture identity. To this end, the next section will address additional essential concepts that will guide our analysis.

2.3. Conceptual Section

In this final section of our literature review, the concepts from which the key themes are derived will be discussed, followed by a brief contextual background on key thinkers expected to have a presence in Ecogram who can be associated more closely with the subculture, as well as a final section on Siege-culture and militant accelerationism.

Concepts

The concept of ‘Kaczynskian anti-technology radicalism’ is borrowed from Fleming (2021), who analysed the communiques of Mexican terrorist organisation ‘Individualists Tending Toward the Wild’, characterising their ideology as “a distinctly Kaczynskian form of anti-tech radicalism” (p.219). The concept is used to account for Kaczynski’s ideological presence. Kaczynski believed humans were maladapted to technological society, had become subordinate to the technological system and that living under it caused psychological problems both in the individual and society. Furthermore, he advocated for the revolutionary overthrow of the techno-industrial system while arguing leftism offered only a pseudo-rebellion. Based on an analysis of confiscated materials taken from Kaczynski’s cabin by the FBI, Fleming finds that Kaczynski’s ideological formation, which took place alone outside of any radical movement, was constructed from a combination of “Ellul’s philosophy of technology, Morris’s sociobiology, and Seligman’s cognitive psychology”. It is an ideology so distinct to him that Fleming characterises him as the potential future Marx of anti-tech, hence why Kaczynski is incorporated into the theme by name (p.220).

‘Anti-urbanism’ is included as a schematic component of fascist antimodernism by Bellassai (2005), in her examination of the connections between masculinity and anti-modernist discourse that characterised Italian fascism.

This concept has been borrowed to account for the belief that urban life is impure and evil, while rural life is pure and good, in both fascism and ecofascism, as outlined by Campion (2021). Anti-urbanism describes the belief that urbanisation is one of many forces of modernity which has disrupted the ecological harmony between race and nature and that towns and cities are corrupt, alienating, materialistic and weaken the White race. It is a term that can be considered distinct from ‘ruralism’, in that it is extremely hostile to urbanisation.

‘Atavism’ represents the core characteristic which binds together a cult of masculinity in the eco-fascist subculture. Atavism is the tendency to revert to something ancestral, and in the context of masculinity expression, can be characterised as the presentation of an atavistic fantasy of manhood, informed by ancient warrior cultures. For eco-fascists, this is deemed to be a pathway of personal development towards returning to a natural order. This concept is informed by Connell's theory of ‘protest masculinities,’ (Maguire, 2021) which outlines how the most marginalised men in society can construct hyper-macho identities to compensate for the lack of resources available to them. The use of this concept does not make the claim that these men face socio-economic deprivation but highlights their worldview of a suppressed masculine energy submerged under modernity. Overly masculine aggressive performances of masculinity are rooted to an effort to re-establish a perceived natural order and hierarchy in a parallel world which violence and physical strength ruled.

The theme ‘Neo-Völkisch’ relates to the revival of völkisch movement ideals. The original völkisch movement was a defensive ideology of German identity which emerged in late 19th century Germany in response to modernity. It was typically characterised by a patriotic grounding of German ethnicity in esoteric spirituality and sentimental interests in folklore and paganism. Neovölkisch refers to a “defensive ideology of white identity against multiculturalism, affirmative action and mass Third World immigration”, which emerged in response “to the high tide of liberalism and globalization from the 1980s onward” (Goodrick-Clarke, 2002 p.6). Its adherents are drawn toward the same “esoteric themes of Aryan origins, secret knowledge and occult heritage” as their 19th century völkisch counterparts.

Prominent figures associated with eco-fascism

The most referenced individual was Theodore John Kaczynski, also known as the ‘Unabomber’, a worshipped figure among eco-fascists. Kaczynski resigned as a mathematics professor at the University of California, Berkely to deliberately live alone in the wild in rural Montana in a self-built cabin, where he began a mail bombing campaign, targeting those whom he regarded as promoting technology (Barnett, 2015) at the expense of “wild nature”. His targets included computer scientists, aviation and industry leaders.

In 1995, national publications including the New York Times caved into his demand to publish his manifesto titled: “Industrial Society and Its Future”. In the text, Kaczynski called for destroying the techno-industrial system and railed against the negative impacts caused by the industrial revolution upon human society. Kaczynski was later captured and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole from where he has continued to correspond with followers and release further works, including Technological Slavery (2010) and Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How (2016).

Kaczynski has since become a well-known figure in pop culture, and his manifesto and later writings have helped him retain a legacy within different movements. His ideas also served to enthuse, at least in part, a violent anarchoprimitivist insurrection movement ‘Individualidades Tendiendo a lo Salvaje’ (ITS – Individualists Tending towards the Wild) a Mexican terrorist group founded in 2011. The group is responsible for violent attacks including the use of bombs and aimed to kill and maim people.

Another key figure who was often associated with eco-fascism is Finnish deep ecologist Kaarlo Pentti Linkola (Protopapadakis, 2014). Linkola controversially advocated for extreme population control, including culling by mass murder, as a means of saving the environment. In Linkola’s works, such as “Can Life Prevail”, he promoted his arguments rooted in so-called “lifeboat ethics”, to justify his idea that mass killing was justifiable to save the environment, asking what should be done “when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and there is only one lifeboat?” Linkola’s answer was that when the lifeboat fills, “those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship’s axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides.” (Wilson, 2019).

His ideas have been described as the “epitome” of eco-fascism (Protopapadakis, 2014), while websites promoting his works even use the ecofascism label to describe his thinking (Pentti Linkola Fansite [PLF], 20062017). However, while Linkola’s ideas can be characterised as ‘pure’ ecofascism, and there is no doubt that his ideas have been influential within the ecofascist community, (Ross and Bevensee, 2020) there were relatively few mentions of Linkola in the dataset of collected posts from Telegram. This was a surprising finding, as he was expected to be much more prominent.

A final key figure was Mike Mahoney, also known as Mike Ma, who is the most well-known contemporary figure associated with the eco-fascist subculture. Ma has been described as both “a product of the emerging ecofascist tendency…. as well as an inspiration for it”, whose work “exhibits the blurry contours of ecofascist tendencies in far-right movements” (Hughes, Jones and Amarasingam, 2022 p.1006). His 2019 self-published Harassment Architecture novel is a Patrick Bateman-esque style rant against the modern world which sits alongside Siege and other far-right manifestos as required reading across farright networks on Telegram (Amend, 2020). In it, Ma dangles violent possibilities in front of his readers, including blowing up power stations and cell towers, precluded with the cynical disclaimer to not do any of these things, when the intention is clearly to plant an inspirational seed in the mind of the reader. There are noted to be many parallels in Harassment Architecture with Kaczynski’s ideas, which “holds out a panacea” in nature (Macklin, 2022 p.986).

Mike Ma is a founder of the Pine Tree Party, a loose movement whose goal is to encourage returning to nature, promoting self-sufficiency and opposing what is perceived as going against natural law (Dysart, 2019). A Telegram channel named after the party was created in 2020 and was one of the first eco-fascist channels on the platform. It was noted to use Nazi symbology and terrorwave aesthetics in propaganda content while heavily promoting violence and infrastructure damage (Shajkovci, 2020).

Ma’s most recent novel, Gothic Violence (2021), is a dark comedy which follows similar themes and followers a gang of jihadist surfers in Florida who take out the national electrical grid. The novel ends with Ma fantasising about a violent revolution which ultimately sees the establishment of a breakaway state named ‘New Atlantis’, in which the internet and power grid is entirely removed along with all forms of modern technology in a world which appears to share a strong affinity with Kaczynski’s anti-technology utopia.

As the above three figures have been broadly considered key to ecofascism, (Macklin 2022) a deep familiarity with their writings was gained prior to the analysis phase in anticipation of their influence in order to better contextualise various themes and attribute to what extent their tendencies indicated a distinct eco-fascist subculture. Mike Ma glorifies militant accelerationism in his writings and occupies a murkier grey area between Siegeculture and Ecogram. However, for the sake of this analysis he will be considered distinct to the latter as he is the only contemporary figure to emerge from eco-fascism.

Siege Culture

The eco-fascist subculture analysed in this thesis inhabits a space which overlaps with the ‘Terrorgram’ community (DFRLab, 2020), the same ecosystem as Siege-culture, which takes its name after neo-Nazi James Mason's book ‘Siege’ based upon a collection of newsletters written by Mason throughout the 1980’s. Mason had previously (Southern Poverty Law Center [SPLC], no date) been involved with the American Nazi Party but eventually grew disillusioned with attempts to build political parties and organizations, believing the way forward for a White revolution lay in an underground movement and the use of terrorist attacks. ‘Siege’ advocated for any action violent or otherwise that would destroy ‘the system’. Mason believes societies are currently in a period of decay and the collapse of society and destruction of The System is inevitable. Thus, followers of Siege wish to hasten the collapse of society as fast as possible through violent means.

Such ideas subsequently became known as “militant accelerationism” which is defined by Matthew Kriner (2022) as “a set of tactics and strategies designed to put pressure on and exacerbate latent social divisions, often through violence, thus hastening societal collapse.” Siege-inspired accelerationism aims to usher in societal collapse through strategically well-placed attacks to dismantle the government and liberal democracy and establish a white ethnostate. Although not all accelerationists are inspired by Siege, the term has become closely associated with the subculture (Lee, 2022).

Networks linked to Siege-culture include The Base, The Green Brigade and Atomwaffen Division (Newhouse 2021). The groups have been identified operating in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia and as far afield as Argentina (Johnson and Feldman, 2021) and have been connected to murders, attack plots and several terrorism prosecutions. Siege-culture originally emerged online out of short-lived neo-Nazi forums like Iron March and Fascist Forge, where the works of Mason were rediscovered and popularised by neo-Nazis.

Siege culture can be characterised as the most “extreme interpretation of fascism and national socialism yet seen”, with “Militancy and ‘edginess’” core elements of the scene’s aesthetic (Lee, 2022). The distinct aesthetic associated with Siege-culture memes and propaganda can be largely credited to the style popularised by Siege-culture activist ‘Dark Foreigner’, whose influence on creating the cohesive glue behind Siege-culture cannot be understated, as explained by Vice journalists Ben Makuch and Mack Lamoureux: “In much the same way slickly-produced ISIS videos from the mid-2010s, with their visceral gore and all-black uniforms. helped attract recruits, Dark Foreigner’s art created the brand and aesthetic for Siege followers, aiding the ideology in festering across the internet into the national security problem it is today” (Makuch and Lamoureux, 2021).

In order to be able to identify the salience Siege-culture influence on the themes which emerged, a close reading of Siege was complemented with ethnographic research on Siege-culture material. The distinct aesthetic and branding of Siege-culture makes its influence easy to identify, as does its reference to ‘Saints’ and various other unique attributes such as the strong presence of glorification of terrorism.

3. Methodology

3.1. Aims and justification of methodology and case study

The aim of this thesis is to identify which key themes emerge within eco-fascist subculture discourse and, where possible, contextualise these themes by situating them either within eco-fascist ideological frameworks, or trace the influence of other ideologues or online spaces, such as accelerationist subcultures. As the study aims to also unpack and discuss the importance and relevance of these themes, it will also fill gaps in the literature, by providing an analysis of tendencies within eco-fascist subculture which have not yet been explored, such as the prevalence of Ted Kaczynski as a key figure or examining how masculinities are expressed.

In doing so, this thesis seeks to provide three contributions. Firstly, while the label eco-fascism is a contested concept with varying definitions, less is known about the fringe eco-fascist subculture on Telegram which constitutes the clearest manifestation of contemporary eco-fascism. Analysing this community will thus increase and clarify our understanding of ‘proper’ ecofascism. Campion’s (2021) definition informs our foundational understanding of the concept. A thematic analysis will aim to test it against dominant themes to investigate whether there is scope to build upon our understanding of ecofascism.

Secondly, the eco-fascist subculture on Telegram has been examined, but confined by methodologies which restrict our understanding of the broader community. In conducting a thematic analysis, this thesis sets out to contribute significantly to what is so far a very specific but relatively sparse area of research.

Thirdly, this study aims to promote more investigations into fringe subcultures within the field of online extremism. Much of the research focuses on propaganda or focuses on specific research questions, missing crucial perspectives. A thematic analysis may be broad in scope but provides important insights. Furthermore, it can provide a useful for tool for further research in the field, such as comparative studies examining communities and subcultures across different platforms.

Answering this question requires a qualitative thematic analysis of the online platforms in which eco-fascists are active, in tandem with a familiarisation of the core texts and ideas often circulated within the subculture to detect and recognise the various ideological tendencies which surface. While eco-fascist networks are also active on Twitter and TikTok, the community on Telegram is the focus of this case study as it is home to a highly concentrated and distinct eco-fascist subculture isolated from mainstream platforms and for its role as a space for the “avant-garde of far-right environmentalism” (Smith, 2021). The eco-fascist subculture on Telegram is unique as it sits close to neoNazi and accelerationist networks, attracting what are the most radical and extreme supporters of far-right environmental politics, providing a more ideologically committed eco-fascist community for analysis as well as potentially having implications for understanding the nature of potential threats posed by eco-fascism.

3.2. Telegram

Telegram is an encrypted messaging app that became particularly notable in the mid-2010’s for its popularity among ISIS supporters and propaganda networks (Bloom, Tiflati and Horgan, 2019; Yayla & Speckhard, 2017). Nonetheless, it later became known as a go-to platform for far-right activists, with an increase in far-right channels detected from 2019 onwards (Bedingfield, 2020; Conway, Scrivens and Macnair, 2019; Owen, 2019a). Farright ecosystems on Telegram continued to grow following the removal of Parler and the de-platforming of prominent far-right activists after the violent storming of Capitol Hill (Feldstein and Gordon, 2021). However, networks linked to neo-Nazi groups (and, in turn, the eco-fascist subculture) remain a fringe within the broader far-right ecosystem on Telegram (Puyosa and Ponce de Leon, 2022).

Telegram has several options for messaging, including sending personto-person direct messages and group chats which can hold a maximum of 200,000 members (Burgess, 2021). The app is often used to create public and private channels, in which administrators can post to a feed followed by an unlimited number of subscribers. These channels are the subject of analysis for this case study. Administrators of channels can post text, images and video content, as well share files including PDFs and create anonymous polls. Posts made in other channels can also be forwarded to their channel feed, making Telegram a highly networked platform, in which content travels across networks from other channels quite easily. Comments can also be turned on under posts, but typically administrators use the Telegram channel option only to broadcast through a feed to subscribers, rather than foster any type of discussion.

3.3. Data collection

This research involved data collection from public Telegram channels affiliated with eco-fascists. These channels often identify themselves using ‘pine tree’ emojis in their titles. Once a number of these channels were identified through the search function on Telegram, they were double-checked to ensure that the content included posts related to the environment or eco-fascist discourse. Any channels which had not posted in more than a week or failed to post content more than ten times per month were eliminated, to ensure channels rich with data for analysis. The next stage was then to expand the initial seed list of channels through a round of snowballing, identifying other similar and connected channels from which content had been shared and subsequently ensuring that they were also active and there was a presence of similar content.

Forwarded posts from other channels were incorporated into the thematic analysis, regardless of whether the origin channels were eco-fascist affiliated, as they constituted a significant number of the posts in the feeds of eco-fascist channels and were regarded as equally important for gauging the influence of ideological tendencies or subcultural influences. While it could be argued only including posts made by the administrator of explicitly eco-fascist channels would have delivered a much more focused dataset for examination, Telegram is by its nature a highly networked app (Walther and Mccoy, 2021) and this must be considered when analysing communities on the platform. Discounting the ecosystem that eco-fascists inhabit, and the content they promote, and share would limit our overall analysis.

Finally, 21 channels were identified. Fifteen of these were randomly selected and data was collected from a period between February 8, 2022 to May 8, 2022. This decision was taken to both make analysis more feasible due to time constraints and to reflect what is often available for data collection, with some far-right Telegram channels often having a short lifespan, particularly those linked to calls for violence. The data was collected through screenshots on the mobile Telegram app from an Android device. Sometimes this was not possible, due to restrictions implemented by the Google Play store on Telegram, which prevents access to certain channels displaying harmful content from a device which has downloaded the app from Google Play (Rivera, 2022). In this case, the channel was viewed through the desktop version of Telegram and collected through the option to export data on the application.

3.4. Ethics and research safety considerations

Several precautions were taken to ensure researcher safety and adherence to ethical guidelines. A VPN was used when searching for Telegram channels and precautions were taken to ensure no links were ever engaged with. An account was set up specifically for this project and no identifiable indicators were used in the profile picture or username. These precautions were taken to ensure researcher safety from both far-right users active within the networks, and for protection from legal issues arising due to the nature of some of the content encountered (such as manuals for making explosives etc.). No attempts were ever made to contact other users, this was adhered to both for ethical reasons and security precautions as well as being irrelevant for the nature of the research project. Likewise, no private chat groups were monitored, and comments were not included from channels which did allow comments under their posts. These posts were always automatically hidden in the feed, a user would have to select the option to view comments to make them visible, meaning they were never inadvertently collected.

The primary method of data collection used was through manual screenshots. This was preferred as it allowed reviewal of the data as it was collected, to ensure that no personal or identifiable information was gathered. In one such case, personal information in the form of a ‘kill list’ appeared in a channel, featuring the names and addresses of public figures and politicians and calling for assassinations. This information was not collected but it was noted and later coded as relevant for the theme of militancy which was identified during the analysis phase. When data had to be exported from the desktop Telegram application instead, as a result of Google Play restrictions on certain channels, the content was manually and carefully reviewed to ensure that no identifiable information would be collected. Only three of the channels in the dataset required access through the desktop application. All images, videos and other files were then saved individually.

Next the data was transferred from the Android device to a Windows laptop and backup protocols were followed, while a password protected folder was created for storing the data for analysis, as well as the backup folder, to ensure security of all data. A full anonymisation of the files in the folder was carried out, with the use of a script which renames all files to randomised sets of numbers. The files were then viewed under the “sort by” option of “names” which allowed all the data to be aggregated for analysis. This prevented certain tendencies or inclinations of individual channel admins from distorting the thematic analysis, with some channels more focused on particular themes than others. It also served to avoid any future attribution and protect the identities of those in the channels, despite all users hiding their identity. After the analysis was complete, all data was to be deleted.

For ethical reasons the names of the channels were not identified or shared for this project, and all example images used were to be cropped or edited if the name of the channel was visible. Core texts which are circulated among eco-fascist networks were studied to make sense of findings during the analytical phase. Many of these texts are published by far-right publishers or self-published by white supremacist activists. It would be considered ethically wrong to financially support extremists by purchasing these texts, so PDF versions were used instead.

3.5. Thematic analysis

The data was analysed through a qualitative approach and using thematic analysis as method. Thematic analysis is an effective tool for analysing data from the internet and social media. It structures the data and prepares it for interpretation. Thus, while broad in scope, conducting a thematic analysis on online extremist content can offer valuable insights. In this regard, the use of this method can produce findings with very real policy implications, ranging from better understanding how the group conducts micro-recruitment efforts targeted towards different audiences, to understanding how the group transmits certain themes and narratives in their messaging, helping better to tailor countermessaging efforts, and even for horizon scanning for international security threats posed by strategic shifts made by the organisation.

When researching extremism, thematic analysis has mostly been used in the understanding of ISIS propaganda (Winter, 2017; Johnston, 2022). Nonetheless, as noted by Conway (2017), determining the role of the internet in violent extremism and terrorism requires branching out beyond the study of jihadism, and paying attention to other ideologies. In this sense, the growing emergence of far-right online subcultures with their “own distinct norms, values, traditions and even languages” (Brace, 2022) presents researchers with an area which increasingly requires more attention. This is even more crucial in an extremism landscape increasingly characterised by post-organisational threats “where the fluid boundaries between organisations and movements, direction and inspiration, and online and offline are becoming more and more ambiguous” (Comerford, 2020).

Research that conducted thematic analysis on far-right communities include an examination of the r/The_Donald subreddit (Gaudette, Scrivens, Davies, & Frank, 2021) to an analysis of the neo-Nazi forum Stormfront, (Bowman-Grieve, 2009) to a comparative review of the ‘/pol’ boards of the various ‘chans’ (Baele, Brace, and Coan, 2021). In Telegram, the research of the far-right tends to have a narrow and specific focus, such as discussions about the military (Davey and Weinberg, 2021), antisemitism (Gunz and Schaller, 2022). As such, Guhl and Davey (2020) have provided the most extensive contribution to our understanding of the broader far-right ecosystem on Telegram with their quantitative and qualitative analysis of 208 white supremacist Telegram channels. Their findings revealed the highly networked nature of the ecosystem, with over one fifth of the posts recorded having been forwarded from another channel as well as the extent to which violent tendencies existed within the discourse of the community.

For this research, the analysis followed the six-phase approach to thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clark (2006). Phase one involved a familiarisation with the data, reviewing the data several times, noting any ideas or initial patterns and trends which appeared to be prominent. Phase two was the generation of initial codes, seeking out interesting features of the data and collating relevant data for each code, to save time, this process was handwritten in a notebook with tally marks corresponding to each code to indicate prevalence of various patterns and provide an initial useful visual representation. Phase three involved the search for initial themes, a broader interpretative phase in which the most prominent codes were sorted into potential coherent themes. The codes themselves also formed various subthemes within each theme.

Phase four was the reviewal of the themes by refining and reviewing them. This took place in two steps. First at the level of the collated data for each theme, ensuring that the data formed a coherent pattern, and then secondly at the level of the entire data set, ensuring that the initial themes reflected meanings within the whole data set. Phase five was the defining and naming of themes, in which working titles and notes taken during the analysis were reviewed and a broader definition and title was considered. Phase six, producing the report, was the final step with a write up of the analysis, telling the story of the data in a concise, coherent and logical manner, going well beyond a descriptive account of the data, and providing a deeper analytical argument which engaged with the research question. To make sense of the data and themes in this latter phase ethnographic research, observation and a thorough familiarisation with literature, subcultural and ideological material became necessary to identify the relevance of the content.

4. Analysis of data

The present chapter will present the study’s findings through two sections. The first, ‘Outlining eco-fascism: nature, outgroups and militancy’, will outline buckets of data which were gathered in order to better understand core attributes of the community, namely how nature was portrayed in visual culture and propaganda, outgroup and ingroup construction and elements of militancy.

The second section, Thematic Analysis, will further address the main themes found: Kaczynskian anti-technology radicalism, anti-Urbanism, Atavism and neo-völkisch. As such, each sub-section will outline one theme and connect it to either eco-fascism, Siege-culture or other of the conceptual frameworks previously discussed. In both sections, images and quotes taken from the dataset will not be attributed to an author for ethical considerations regarding confidentiality.

4.1. Outlining eco-fascism: nature, outgroups/ingroups and militancy

The first section of the analysis will focus on the buckets of data relating to nature, outgroups and militancy. While not forming the basis of the core categories identified in our thematic analysis, these three categories provide us with an introduction and starting point for understanding the eco-fascist subculture and can be further drawn upon later in the analysis when they overlap with the identified themes.

4.1.1. Nature

The most striking distinction between the eco-fascist subculture and other networks in the far-right ecosystem on Telegram is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the prominence of nature imagery throughout their visual culture. These images often transmit a sense of nostalgia and loss while simultaneously depicting an imaginary eco-fascist utopia of what could be again. Nature imagery is representative symbolically of a white spiritual homeland, in which race, soil and spirituality are deeply connected. For this stage of the analysis, the imagery which emerged has been divided into four sub-themes, notably: idyllic imagery, spirituality and mysticism, far-right symbolism, and messages of ‘Return, Embrace and Defend’ nature.

Idyllic imagery

Images of forests, bucolic landscapes and idyllic pastoral scenes are universal across all eco-fascist channels. These representations of nature can vary from photographs of forests, mountains, valleys, rivers and wildlife from across Europe. Artworks, such as paintings depicting pleasant and peaceful scenes of rural life or folk traditions are also commonplace. Even though most of this content is posted without any text, the context of the imagery can be regarded as inherently political. It always represents landscapes native to Europe (Figure 1) and North America with what is a showcasing of beautiful ecosystems of White populations to foster a sense of pride and establish an ingroup identity tied to natural environments.

Several other images from this set were identified, showcasing European countries.

There is also a sense of nostalgia to much of the representations as they can also depict a pristine or pre-modern world unblemished by industrialisation. This worship of the rural, with a back-to-the-land idyllic focus on pastoral ways of living before the disruptions caused by modernity, shares many commonalities with the Nazi German notions of ‘blood and soil’ (Biehl and Staudenmaier, 1996).

Images portraying isolated cabins or idyllic homesteads (Figure 2) surrounded by wild nature appeal to a strong anti-urbanist sentiment within the eco-fascist subculture as well as a personal desire to be anchored within the scenery. With much of this imagery going back in time there is a sense of nostalgia for before industrialisation, immigration and multiculturalism, when native white populations were the sole custodians of the land and lived immersed in nature. Traditional white families foraging for food or tending to animals, display romantic fantasies of an idealised lifestyle. Together, these images encapsulate what is being mourned for and what is desired to be restored in the eco-fascist utopian vision.

Spirituality and Mysticism

Nature is also characterised in spiritual or mystical terms. Images include clouds or lightning bolts shaped like humans, animals, or ancient pagan spiritual figures. Trees which bear a striking resemblance to a human heart, or shapes on tree bark that appear as human eyes (Figure 3). It is unknown how much of this content consisted of edited images, but while lacking any context, they seemingly serve to offer proof that elements of spirituality are inherent within nature. This was clearly articulated in a post featuring an image of an ancient olive tree known as “The Thinking Tree” in Puglia, Italy, which strongly resembled a man deep in thought, with the accompanying text entertaining such ideas, stating: “Things like this would make it very easy to be Animist” (Animism relates to the idea that all natural objects contain their own spirit and are alive).

Images like this depicted spiritual elements inherent within nature.

Continuing the attachment of supernatural qualities to the natural world, some images are clearly edited, portraying tree branches or roots which tangle together to form the shape of doorways or portals to another realm. This mystification of the environment serves to ‘spiritualise’ nature as powerful and deeply connected to something beyond the material world. Images of forests or mountains in the dataset also included captions explicitly related to vague senses of spirituality such “Nature is my Church” (Figure 4), or “Worship Nature”, depicting nature as a form of spiritual sanctuary and homeland.

Another prominent representation of spirituality and mysticism in nature often related to paganism and folklore, with pagan style art and folk culture imagery typically featuring a natural setting, serving to invoke the connection between the White race and their ancestral traditions through connecting their spirituality to the natural environment. In reinforcing this exclusive connection, the content also reinforces an external ‘othering’ of those deemed to be nonnatives.

Far-right symbolism

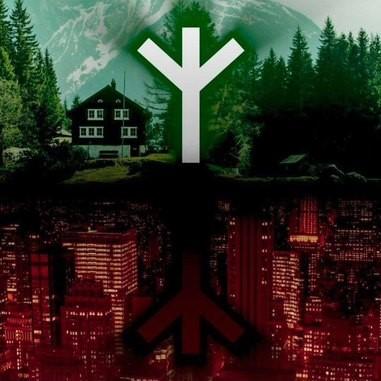

There is a heavy use of far-right symbols and messaging accompanying depictions of nature. The visual effect of these images is they appear to represent a neo-Nazi ‘stamp of ownership’ on natural landscapes and are so distinct to the eco-fascist subculture they incorporate its ‘brand’. The most common symbol to appear is the Algiz or ‘life rune’(ᛉ), a Norse rune once appropriated by Nazi

Germany (ADL, 2022) and used for the SS’s Lebensborn project (which focused on promoting the increase in Aryan population birth rates). During the post-war era the rune became popular among neo-Nazis.

The Algiz rune has become the primary insignia of choice for the ecofascist community, and commonly appears in their propaganda imagery alongside nature scenery, frequently superimposed over woodlands and natural landscapes. In some contexts, it appears to carry an almost religious-like reverence, representing a fascist spiritual infatuation with the natural. In one striking example (Figure 5), a green Algiz rune appears standing upright like a crucifix alongside a solitary wooden house with a forest and mountainous landscape background. Directly below, in dark red, an inverse Algiz rune, associated with ‘death’ (Reporting Radicalism, no date) appears against a city backdrop of skyscrapers and apartment buildings, illuminating how the symbol has been co-opted to represent an idealised way of life in opposition to modernity.

Anti-urbanism messaging expressed through inverse Algiz rune.

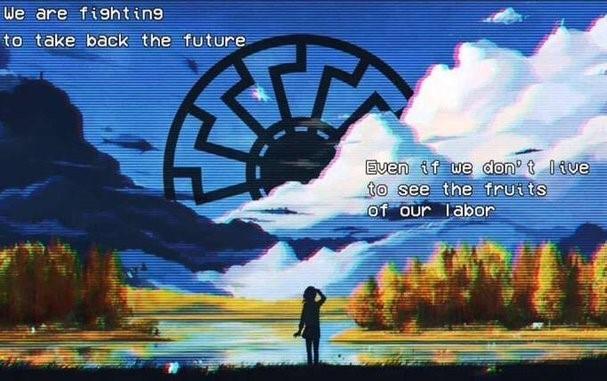

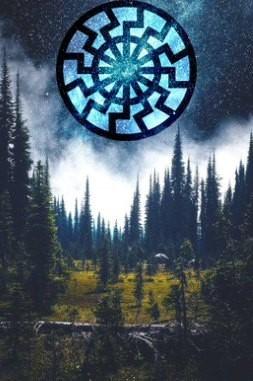

The Sonnenrad symbol, also known as the Sunwheel or Black Sun, is the second most common symbol to appear in eco-fascist imagery and propaganda. The distinct wheel insignia featured as a design on a marble relief in Heinrich Himmler’s Wewelsburg castle, which was set to be the spiritual home of the SS (Hinde, 2021). Today it is widely popular among neo-Nazi’s, even being used by the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion in Ukraine (Miller, 2018) and displayed on the front cover of Tarrant’s 2019 manifesto. More recently it was also worn by Gendron, the Buffalo shooter, during his May 2022 shooting attack (ADL, 2022a). In eco-fascist propaganda, however, the Sonnenrad wheel often appears looming in the sky (Figure 6) or floating over mountaintops or forests with a cosmos-like aura as if taking the place of a rising sun or moon (Figure 7).

Sonnenrad appearing like a rising sun, promising a new dawn. The glitchy aesthetic invokes the feelings of nostalgia while the message promises of a future utopia.

Nature imagery featuring the sonnenrad often casts the symbol with an almost planetary quality.

The use of these fascist symbols, which serve as stamps of ownership upon various depictions of the environment, make an explicitly political ‘blood and soil’ statement about white identity and the natural landscapes. They also seed an idea of fascism as an inherent force within nature, casting the environment as the key battleground, within which a fascist spirit can be reawakened. Together, these images constitute the eco-fascist ‘brand’, as they remain the most distinct form of eco-fascist propaganda imagery which can distinguish itself from other far-right material across the Terrorgram ecosystem.

Return. Embrace. Defend.

Finally, much of the messaging accompanying propaganda imagery of nature can be summarised as calling on followers to ‘return’, ‘embrace’ or ‘defend’ nature. These calls seem to outline a pathway towards salvation by rejecting modern urban life, living closer to nature and reconnecting with a spiritual connection lost to modernity, before finally committing to defend what is thus rightfully theirs.

Captions urge followers to “return to nature” or to simply “return home”, claiming ownership over nature as the rightful natural habitat of those deemed native to the land, while also characterizing nature as a spiritual homeland. To live in nature is to return ‘home’ (Figure 8), to the natural order and way of life, rejecting the alienation of suburbs and cities and getting back in touch with ancestral roots.

Other variations used the German word ‘Heimat’.

Calls for followers to “embrace”, “commune” or “connect” with nature or simply to “go outside” seek to reawaken what is seen as a lost connection with nature. Messaging accompanying representations of nature speak to a sense of spiritual ‘wholeness’ which can be attained in nature when removed from modern urban life, with captions including: “create a life you don’t need a vacation from”.

Indeed, there is a strong and significant body of research which points to the benefits of experiencing nature for mental health and wellbeing (Berman, Jonides and Kaplan, 2008; Keniger, Gaston, Irvine and Fuller, 2013; Robbins, 2020) yet calls to return to nature often aligns with their more extreme messaging, such as a call to “revolt against the modern world”. Another iteration relates to encouraging followers to learn how to grow food, hunt or fish, with slogans calling on followers to get “back to basics” and “become selfsufficient”, sometimes tied closely to a means of getting back at the system by dropping out to “starve the beast”.

Alongside this messaging of returning to, embracing, and connecting with nature is the call to “defend nature”. Graphics and propaganda feature Nazi symbols imposed onto images of landscapes alongside captions calling on followers to “defend the wild”, “protect” or “save” nature and seek to characterise the threat as an ‘other’ which must be fought through violent means. One such image with the slogan “protect nature” features a German Wehrmarcht infantryman crouched in a woodland (Figure 9), while others call for more direct militancy and violence against those responsible for harming forests. One main cipher for this form of messaging across the ecofascist community is Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, whose image is prevalent across eco-fascist networks. Kaczynski will also be discussed in a later section, as will a more detailed exploration of his overlap with themes of militancy.

Images such as this appear to equate nature with race. The ‘other’ in these contexts is never explicitly identified.

While depictions of nature vary across the dataset, they can be broadly summarised as portraying both a past world lost to modernity and a possible future white supremacist utopia. They transmit both feelings of loss, pride, and emphasise the exclusiveness of the relationship between race and nature through casting the natural environment as a spiritual homeland for Whites. The message broadcast to followers is to return and embrace nature, in what Staudenmaier has referred to as “racial salvation through a return to the land” (2011 p.26). The final stage and logical conclusion of this relationship requires a commitment to ultimately defend nature through violent means. Nature in this sense is instrumentalised for identity formation and weaponised to mobilise actors to commit to violence on its behalf.

4.1.2. Outgroups/Ingroups

Rhetoric targeting specific outgroups appeared alongside discourse forming a White ingroup identity. Outgroups were also defined through what Berger refers to as a “narrative process of identity construction that parallels the construction of the in-group definition” (2018 p.57) in which ingroup formation ‘pushes out’ the other.

What emerges is a typical worldview of hate consistent with neoNazism, with little to distinguish the eco-fascist subculture from other far-right movements. The two dominant outgroups to appear were Jews, followed by African Americans. A White ingroup identity was repeatedly reinforced throughout the dataset, often through the promotion of ancestral pride and historical connections to nature, by linking Whites to what is characterised as their native ecosystem.

Jews were by far the most common outgroup to emerge within the dataset, with antisemitism appearing frequently in the form of tropes common across the broader far-right. Jews were characterised as conspiring to undermine the white race, using corrupting influences such as pornography, communism, and feminism to weaken and subjugate whites. They were portrayed as having total control of the US media and the US government and were accused of using their economic and political power to weaponize the Black community and “colored hordes” of the developing world against White populations. Violence against Jewish people was often encouraged (Figure 10).

Antisemitic content attempting to attach itself to animal rights message. This font and style are typical of Siege-culture material.

Calls for followers to become self-sufficient or live in nature were promoted as a means of breaking free from Jewish control, with one user declaring: “Don't let the jew in the box take hold of you”. Others accused Jews of being out of sync with the environment, accusing them of “heavily modifying nature and the world to suit their needs.” Or believing “themselves to be above the world, instead of among it.” Meanwhile, narratives also emerged regarding health, with conspiracies casting Jews as behind the spreading of false information about certain food products deemed by the eco-fascist community to be naturally good for Whites, such as raw milk. A similar logic informed antivaccine narratives.

The second most referenced outgroup in the data set was African Americans. They were typically labelled with racial slurs and dehumanising language. Much of the content related to Black on White crime in the US, such as screenshots of news articles reporting on black men killing or raping Whites. White victims of Black violence were appropriated as martyrs (Figure 11) and Blacks were described as a “threat to white nations”. They appeared in cherrypicked CCTV footage or fight videos committing violent assaults, murders, and robberies. One typical video included a compilation of footage of brutal violence carried out by Black men against White victims, while the accompanying audio featured a mash up of voices discussing White privilege and threats posed by White supremacy. The purpose of such content was clearly geared towards provoking a strong emotional reaction. One such piece of content was labelled “hatefuel”.

An Uber driver murdered by an African American man in 2022 was featured alongside a quote recorded from her in-car camera shortly before she was killed. This type of material was intended to provoke a strong emotional response.

It is notable the outgroup discourse indicates a notable focus on USbased Jews and African Americans in particular, suggesting a significant proportion of channel admins appeared to be in North America. This was further highlighted with another distinct outgroup singled out, namely US-based police.

A second observation is prominent, this is, outgroups in the dataset indicate no strong animosity towards those who work for fossil fuel companies or the logging industry, for example. In fact, there was hardly anything in the outgroup discourse to differentiate eco-fascism from other far-right ideologies. Other than several posts directed towards ‘urbanites’ or ‘technophiles’, the ecofascist subculture failed to produce a distinct prominent outgroup in relation to the environment. Posts which focused on individuals deemed to be responsible for harming the environment failed to explicitly tie the message to a particular group (Figure 12).

A rare example of threats directed towards those responsible for environmental harm fails to identify targets. Statements such as this were typically vague.

However, a sentiment more distinct to eco-fascism emerges when reinforcing a link between the natural environment and ingroup ‘indigenous’ white populations that excludes non-natives. A focus on ancestral links to the land through reviving folklore and paganism serves to reinforce the link between the territory and the White race. Meanwhile, a sense of pan-racial solidarity is encouraged as users are urged to support their “fellow whites” and be proud of their identity by reminding followers of their ancestral legacies with apparent motivational statements, including: “The blood that runs through your veins is unstoppable”.

However, the majority of ingroup discourse revolves around the naturalness of Whites to their native ecosystems, thereby highlighting outgroups also in the process. This was particularly present with discourse related to Europe, take for instance the below text:

“The reason why Whites have a special bond with nature. A soul incarnates in a specific body having specific genetic attributes and traits in order to grow in a given environment that will stimulate and further the spiritual evolution of that individual. Each race is designed for/by a particular habitat...

A Black person per se is misplaced in a continent like Europe, and spiritually deprived. Lost. In my years of hiking and wandering in the many European forests and mountains, never do I recall encountering a dark-skinned individual. Blacks don’t camp nor hike, ski, or climb mountains. They're even known to make fun of us for it. They cannot grasp any of it.

The reason is that the mountains and European nature more generally, does not call them. Europe speaks and calls her children. Our Gods who live in our blood, are calling us back home”.

The above excerpt explicitly exclaims what is typically heavily implied through much of the representations of nature within eco-fascist visual culture: the land is a natural ecosystem of whites, and other races do not belong there. In this regard, the same black men who are seen committing violent crimes in the streets, either against whites or one another, are easily portrayed as a foreign and invasive species, harmful to the white ecosystem. Likewise, the Jewish globalist elites portrayed as using immigration and corrupting influences to harm White homelands quickly become characterised as a foreign parasite, surviving by weakening their host.

It is arguable there is a major contradiction with this narrative for USbased eco-fascists however, who may struggle to claim the same native ties to

North American natural ecosystems as Europeans. Although this issue was never confronted or discussed in the dataset, Campion (2021) has noted that in settler societies a select community can make the same privileged claims on territory.

This message merges within the broader context of returning, embracing and reconnecting with nature. Whites are called upon to return to what is deemed to be their spiritual homeland, their natural environment. In urging followers to defend, protect or save nature, the message is accompanied with weapons of violence, such as rifles. In this sense, the threat is portrayed as an ‘other’ who must be fought. The message to defend nature is not calling for petitions, climate change activism or protests. The message is calling for killing an invader who, through the outgroup formation, is characterised as a foreign species, disrupting the harmony between Whites and their ecosystem.

4.1.3. Militancy

The appearance of what is categorized as militancy had a strong presence in the dataset indicating a high degree of overlap with accelerationist and Siegeculture networks. The militancy label accounts for an umbrella group of narratives and messaging surrounding violence, ranging from calls for sabotage to the sharing of tactical skills knowledge and the glorification of terrorism, all the way up to directs calls for targeted killing. Also categorised under the militancy label is a category of visual culture called ‘terrorwave’ (@Jake_Hanrahan, 2018) comprised of militant aesthetics and broadly popular across the Terrorgram subculture.

The most distinct form of militancy to eco-fascist subculture was sabotage. Examples ranged from guidance on ‘ecotage’ taken from scanned pages of “Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching”, a manual used by early ‘Earth First!’ activists, detailing equipment and gear required for tree spiking, which demonstrated an interesting engagement with reading material beyond far-right texts.

Other examples of sabotage focused on the targeting of infrastructure sustaining modern civilization, with an extensive array of posts calling for attacks on the power grid, particularly electrical substations, and transmission towers. Many of the posts went well beyond inspirational material, but outlined practical steps for action, like highlighting vulnerabilities to the US power grid.

One such post pointed out that if nine key substations were to be taken out and disabled, the US would suffer a coast-to-coast blackout. The purpose of these posts was to inspire others to carry out such actions. The content aligned with militant accelerationist aims, with the overall strategy for such actions aimed at provoking societal collapse (Figure 13).

Image accompanied by the below text: “📺 No matter how bad it gets, as long as the modern man has his TV and his paycheck things will never change. 🧨 Therefore the only solution is to take these things from him. [REDACT] your local power substation. [REDACT] your local railway. [REDACT] your local amazon center. [REDACT] your local grocery store”.

Other content praised far-right terrorists like Dylann Roof, who shot and killed nine black worshippers at a Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in the US in 2015, or Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the 2019 Christchurch Mosque attack. Posts included montage videos celebrating shootings and acts of terror, such as the 2019 El Paso attack targeting Latinos or the 2018 Pittsburgh Synagogue shooting. Infographics also celebrated older far-right terrorists such as David Copeland, the 1999 London nail bomber who targeted black, Bengali and LGBT communities.

The glorification of terrorism within the broader Terrorgram subculture was so prevalent that a Siege-culture calendar dubbed the ‘Saints Calendar’ commemorating important ‘Days of Action’ existed celebrating anniversaries of far-right terrorist attacks, the birthdays of perpetrators or the dates of their arrests. The calendar itself was a private dedicated channel not included in the dataset. But the highly networked nature of Telegram meant that posts were regularly forwarded across the far-right Telegram community, including Ecogram, ensuring the glorification of terrorism was heavily ritualised (Figure 14).

Post commemorating the Oklahoma bomber on the anniversary of his attack. Similar posts were identified for other terrorists on the anniversary of their attacks, including Christchurch attacker.

A channel admin posting on April 18h, the day before the Oklahoma bombing anniversary, demonstrates the anticipation of these dates and how the process of collective commemoration serves to goad others into carrying out similar actions, or contribute to the collective ritual of glorification: “IT'S

SAINT MCVEIGH DAY EVE, TERRORBROS! CAN'T WAIT TO SEE EVERYONE'S OC TOMORROW!!! 🚚💣😀” (“OC”, stands for ‘original