Gary Greenberg

After Nature

The varieties of technological experience

Discussed in this essay:

Beyond Therapy: Biotechnology and the Pursuit of Happiness, by the President’s Council on Bioethics. ReganBooks, 2003. 328 pages. $14–95.

Life, Liberty and the Defense of Dignity: The Challenge for Bioethics, by Leon R. Kass. Encounter Books, 2002. 313 pages. $26.95.

Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age, by Bill McKibben. Henry Holt, 2003. 288 pages. $25.

Gary Greenberg is a psychotherapist and the author of The Self on the Shelf: Recovery Books and the Good Life.

The Republic was barely a half-century old when Nathaniel Hawthorne introduced his readers to Aylmer, the brilliant alchemist, and his beautiful but imperfect wife, Georgiana, whose “crimson stain” torments the couple in “The Birthmark.” Aylmer manages to eliminate the blemish that mars Georgiana’s cheek with a potion concocted in his laboratory, but this relentless pursuit of perfection kills his wife. Hawthorne begins his story by recalling how the “recent discovery of electricity and other kindred mysteries of Nature seemed to open paths into the region of miracle,” and he proceeds to capture all the fear and ambivalence of a people groping their way through those unexplored landscapes. These were ancient anxieties, no doubt worried at since Prometheus stole fire, but certain questions posed by “The Birthmark” must have held particular resonance for a society newly dedicated to happiness and self-improvement: What happens when the scientist’s attempt to wrest from nature its secrets and “make new worlds for himself ” is turned back upon the human body? What limits, if any, should we impose on the quest to make ourselves better?

For the first official meeting of the President’s Council on Bioethics, in the fall of 2001, Leon Kass, who was appointed by George W. Bush as the Council’s chairman, assigned Hawthorne’s story as the subject of discussion. The scene is jarring: a cautionary tale about hubris, dense in metaphor and allusion, surfaces in an administration not exactly known for its scruples about arrogance or its familiarity with the literary canon. (In his description of what the Council on Bioethics was supposed to accomplish, Bush—with his usual precision and mastery of the English language—expressed the hope that “it’ll help people like me understand ... how to come to grips with how medicine and science interface with the dignity of, the issue of life and the dignity of life and the notion that life is, you know, that there is a Creator.”) Nevertheless, a literary turn is not surprising for Kass, a lapsed physician and a professor at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought. Beyond Therapy, the Council’s most recent publication, includes references to Aristotle and Plato, Descartes and Montaigne, Shakespeare and Bacon, Huxley and Borges. It also approaches its subject in a way not dissimilar to that of certain environmentalists on the left, for whom the question of technology is one not simply of its effects but of the shape and nature of the technological enterprise itself.

Beyond Therapy examines a situation that can arise only in a society with too much time on its hands. Drugs and techniques, such as anabolic steroids and antidepressants, that were developed as therapies for specific diseases have come into use as “enhancement technologies”—means by which to make ourselves, in psychiatrist Peter Kramer’s memorable phrase, “better than well.” How should we understand our ability to enhance athletic performance? to slow the process of aging? to increase our attention span or lessen our melancholy? to choose the sex of our offspring? Should we welcome these technologies as allies in our pursuit of happiness, or snub them as violations of the work ethic that’s supposed to guide the pursuit? Should we take a page from Faust and reject the bargain, or follow Galileo’s lead into a world beyond our imagining? A chapter on steroids is replete with piquant questions like these:

Which biomedical interventions for the sake of superior performance are consistent with... our full flourishing as human beings ... as active, self-aware, self-directed agents? And, conversely, when is the alienation of biological process from active experience dehumanizing, compromising the lived humanity of our efforts and thus making our superior performance in some way false—not simply our own, not fully human?... Can our disquiet about pharmacological and genetic enhancement withstand rational scrutiny? More deeply, what does the prospect of such interventions tell us about the nature of human activity and the meaning of human identity?

Kass and company begin their report with the recognition that the ethical questions raised by biotechnologies are fundamentally moral questions— that is, questions about what makes life worth living and why. You can’t decide whether it’s a good idea to take drugs that will extend the average life span by thirty or forty years without trying to figure out what that life is for in the first place.

Once you start looking at bioethical dilemmas this way,{1} virtually every question raised by new medical technologies becomes difficult. Even a distinction as seemingly simple as the one between therapy and enhancement collapses. It would be comforting if we could simply declare that therapeutic use—such as giving human growth hormone to someone with dwarfism—is acceptable, whereas enhancement use—giving human growth hormone to an aspiring basketball player—is not. But, as acknowledged in Beyond Therapy,

most human capacities fall along a ... “normal distribution” curve, and individuals who find themselves near the lower end of the normal distribution may be considered disadvantaged and therefore unhealthy in comparison with others. But the average may equally regard themselves as disadvantaged with regard to the above average. If one is responding in both cases to perceived disadvantage, on what principle can we call helping someone at the lower end “therapy” and helping someone who is merely average “enhancement”?

This kind of dizzying relativism, which claims that there is nothing in nature that allows us to define with certainty where health stops and illness begins, leads the Council to conclude that today’s enhancement will become tomorrow’s therapy. If, for example, antidepressants can make even nondepressed people happier, then eventually ordinary unhappiness will become a “disease” too.{2} Which means that if we are going to evaluate the wisdom of going beyond therapy, we cannot rely “on the distinction between therapy and enhancement to do the work of moral judgment.... The human meaning and moral assessment must be tackled directly.”

Rather than terrify the reader with hysterical polemics about science-fiction nightmares, Beyond Therapy bases its ethical concerns on plausible or currently available enhancement techniques. The Council even assumes the best about our scientists and inventors, that they can relieve the pain of traumatic memories or extend our life span by several decades without harming us. The book can afford this kind of generosity because its authors’ concerns are larger than the physical side effects of experiments gone awry; it is the concept of technology itself, and the mode of human existence it assumes, that interests the Council.

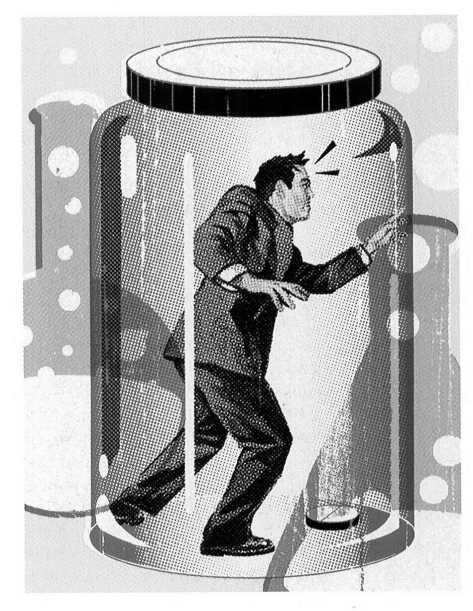

Beyond Therapy borrows heavily from Kass’s Life, Liberty and the Defense of Dignity, in which he notes that technology is not simply a means to an end but “an entire way of being in the world, a social phenomenon more than a merely material one, characterized by the effort, through rational analysis, methodical artfulness and correlative organization, to order all aspects of our world toward efficiency, ease and control.” Technology, in other words, is the culmination of a mind that tries to impose itself on nature, “the disposition rationally to order and predict and control everything feasible in order to master fortune and spontaneity, violence and wildness, and leave nothing to chance.” Before we can fashion our technological devices, we must alienate ourselves from the world around us and see it as something standing by for our use.

This alienation may originate within us, but the techniques it invents soon colonize our consciousness, shaping our expectations and estranging us further from experiences that are immediate and real. So taken are we by our miracles that we become apprentices to technology’s sorcerer. Thus Georgiana’s revulsion for her birthmark develops only after her husband has presented her with the possibility of removing it, and Aylmer’s disgust is the result “of the tyrannizing influence acquired by one idea over his mind.” The body is measured against technology’s potential, rather than the other way around. This brand of technological critique, which is shared by not only Hawthorne and Kass but also Heidegger and Ellul, among others, transcends psychology and even ideology, and forces us to confront the greater questions of existence—of being in this world.

But alienating yourself from the ravages of nature can have its rewards, such as polio vaccines, antibiotics, and fewer cavities. If one is not to conclude, with Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski, that “it would be better to dump the whole stinking system and take the consequences,” one must find a way of distinguishing good technology from bad—technology that serves our purposes from technology that devises purposes of its own. And this distinction, according to Kass and the authors of Beyond Therapy, is where the monstrous implications of bioenhancement lie. Therapy responds to the needs of the body, whereas bioenhancement responds to the aspirations created by therapy: “human nature,” warns Kass, “is on the operating table, ready for alteration.” And the Council sounds a similar alarm: “In wanting to improve our bodies and our minds using new tools to enhance their performance, we risk making our bodies and minds little different from our tools.”

The President’s Council on Bioethics is a seventeen-member panel that includes, in addition to scientists and physicians, Francis Fukuyama and Charles Krauthammer, famous chatterers both, who have elsewhere praised the virtues of the free market and criticized government regulation. So it is perhaps surprising to read how Beyond Therapy admonishes the pharmaceutical industry for manufacturing desires “almost as effectively as pills” and points out that “entrepreneurs not only resist governmental limitation of their work. … The success of enterprise often turns on anticipating and stimulating consumer demand, sometimes even creating it where none exists.” This is not a simple indictment of “cosmetic pharmacology,” which is the Council’s ostensible subject; it seems to be an acknowledgment that the invisible hand alone cannot guide us wisely. And it is also a lament about the consumerism that drives the U.S. economy: when it comes to decrying a marketplace designed to satisfy our open-ended desires and ambitions, why stop at Viagra?

This message, however, is not likely to be heard by the president and his free marketeers, especially since the Council ends up muting its own critique. After delivering a comprehensive diagnosis of what it is about biotechnology that ails us, Beyond Therapy ends with the tepid hope that the book “might spark and inform a public debate, so that however the nation proceeds, it will do so with its eyes wide open”—a move rather like Jonathan Edwards ending a sermon by gently suggesting that his congregation go forth and think about it. The Council settles for nibbling gently at the hand that feeds it: rather than follow its argument to a logical conclusion, which would decisively challenge the market mechanism as yet another technology that seeks “to order all aspects of our world toward efficiency” by creating the context in which enhancement technologies arise and make sense, it seemingly absorbs the unfettered market into the natural order and implies that there is nothing to do but cultivate a sense of repugnance—a notoriously vague and unreliable feeling that has trouble distinguishing between homosexuality and homicide.

Indeed, the Council follows Kass’s lead from a 1997 New Republic article in which he promotes “the wisdom of repugnance” that often accompanies technological innovation as the apprehension of our inherent limits, nature’s way of telling us when to stop. This means, of course, that certain suffering will not be relieved by science, but life—at least-according to Kass and the President’s Council—is suffering, and there are better, more dignified tragedies to be had than those offered by technology’s successes:

A flourishing human life is not a life lived with an ageless body or an untroubled soul, but rather a life lived in rhythmed time, mindful of time’s limits, appreciative of each season and filled first of all with those intimate human relations that are ours only because we are born, age, replace ourselves, decline, and die—and know it. It is a life of aspiration, made possible by and born of experienced lack, of the disproportion between the transcendent longings of the soul and the limited capacities of our bodies and minds.

The pastoral language in Beyond Therapy is meant to evoke a time when we knew where we belonged, when a technologically unmediated life meant that we could be trusted to reject certain challenges to the natural order. Its nostalgic longing also reflects a neoconservative theory of human nature, one that is suspicious of free individuals trying to use extraordinary means to alter their station in life. In Life, Liberty and the Defense of Dignity, Kass complains,

Older ... notions of human dignity, formerly the social counterweight to the political doctrine of rights, have been greatly attenuated—partly thanks to the success of liberalism and its alliance with the modern technological project for the mastery of nature. The right to the pursuit of happiness ... is, as a result, perfectly compatible with utter self-indulgence, mindless pastimes and the factitious gratifications of high-tech amusements and drug-induced euphoria.

The culprit for Kass is not so much the market system that creates the desires as it is “liberalism”—individual freedom run amok. Similarly, the Council declares: “We must live ... as true men and women, accepting our finite limits, cultivating our given gifts.” It is a call to stay in line, to accept things as they are, to resign oneself to the natural order and to circumscribe one’s freedom accordingly.

Restraint isn’t exactly America’s specialty. And the prospect of “a life lived in rhythmed time,” whatever that is, isn’t likely to have harried multitaskers burning their Prozac prescriptions or eighty-year-olds celebrating their failures of memory. If the Council misses its insensitivity to life as it is lived by so many Americans, not to mention the irony of this message issuing forth from an administration not given to humble assent to rules, this must be seen as a function of the essentially homiletic structure of Beyond Therapy, which settles in the end for platitudes about cultivating “given gifts” and respecting “human dignity.” Indeed, it’s worrisome to contemplate this hollow rhetoric in the mouths of politicians who take the term “bully pulpit” so literally and who seem bent on limiting personal freedoms, such as the decision to control one’s own reproductive life.

Yet there is another irony to Beyond Therapy, of which its authors seem altogether unaware: The idylls of harmony and rhythm evoke a time when people returned to the land to set themselves free from the depredations of consumer society, a time that is nearer to ours than the neoconservative preserves of Athens or Eden. The Council’s call to a life “mindful of time’s limits, appreciative of each season” could easily have been posted on the wall of any sixties commune (or, for that matter, of Hawthorne’s own Brook Farm).

It’s a coincidence that the Council, at least those members who are sure that everything bad about this country began in 1965, cannot be comfortable with, but all they would have to do for confirmation of this peculiar overlap is read Bill McKibben’s most recent book, Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age. In it, he treads a path remarkably similar to that of the President’s Council—disconcertingly so, when one considers that Me-Kibben, whose End of Nature was the first important book about global warming, is a leading proponent of the kind of green politics that are perhaps the most vigorous remnant of the sixties upheaval.

Enough puts forth a modest proposal: “We need to do an unlikely thing: We need to survey the world we now inhabit and proclaim it good.” Me-Kibben is no Pangloss; he realizes that there are problems aplenty with which to contend. But, he maintains, we’ve reached a point of diminishing returns on new developments, particularly those in the biotechnology field, which means that it is time to say “Enough”— to allow “the rush of technological innovation that’s marked the last five hundred years [to] finally slow, and spread out to water the whole delta of human possibility.”

McKibben isn’t the first person to worry that the next big innovation will be the end of us all. Like the President’s Council, he claims that because it is directed toward the human body, biotechnology—at least the kind that would genetically engineer our children and grant us immortality (which are the two major bugaboos in Enough)—is a special case; it brings us to “the moment when we stand precariously on the sharp ridge between the human past and the posthuman future.” And we should, he thinks, back away from the abyss as fast as our unengineered legs will carry us, because the new biotechnologies will take away the limited opportunity to make meaning of our lives that has been left by technology’s disenchantment of the universe. So, for example, the child genetically engineered to be a concert pianist would be

a player piano as much as a human, doomed to create a particular context for herself, ever uncertain whether it is her skill and devotion... that move her fingers so nimbly.... She [is robbed] forever of the chance to make music her own authentic context—or to choose something else ... as the act that brings her life to life.

In his assumption that such a player piano can ever exist, McKibben is being much more sanguine about the prospects for genetic engineering than even most genetic engineers; his dire predictions function as straw men, sci-fi scenarios that the President’s Council prudently avoids. Of course, this may simply be a rhetorical device—a technology that threatens to take the choice out of human activity cannot help but rouse people into action— and, whatever it does, it illustrates the enormity of the task of re-moralizing our discussion of technology.

McKibben is not content simply to get us agitated about notions of human dignity; he also insists that we live in a political world, and if biotechnology eventually succeeds in taking away the freedom to choose our destinies, “it will take democracy with it. Forever.” He addresses what the President’s Council remains blind to—political change, which in this case is eschatological. The “weird coalitions” that saying “enough” creates—feminists and pro-lifers, Bill Kristol and Todd Gitlin, Bill McKibben and Francis Fukuyama—only reflect the apocalyptic dimensions of our jeopardy and the revolutionary quality of any possible redemption. When Kristol concurs with Gitlin, a new politics is on the way, one that “coalesces ... around some version of what I’ve been calling the enough point.” And for a political citizenry galvanized by these dangers, resistance to technology may, finally, not be futile.

It makes sense that these books reach toward Armageddon. They are, after all, works of prophecy— not in the classical sense of prognostication but in the biblical sense of trying to awaken a people to a foundational crisis whose tendency is to blind them to its very presence. These writers understand that if you tug hard enough on one of biotechnology’s threads—anti-aging drugs, say, or genetic engineering—you will soon unravel the whole tapestry of modernity. For nothing else holds it together except the sheer effectiveness of our technological apparatus. Heidegger described this as “exactly what is so uncanny” about technology: “that everything is functioning and that the functioning drives us more and more to even further functioning, and that technology tears men loose from the earth and uproots them.” Question what it actually means to drive your car to the store for a loaf of bread, allow yourself to think about the web of practices, the wars and economic injustices and environmental despoliation, into which this simple act is woven, and you will feel that uprootedness, that sense of alienation. It’s enough to make you wish there were a God insisting upon renunciation on pain of damnation.

Which is precisely what these prophets of technology end up doing. In this, too, they follow Heidegger, who toward the end of his life famously told Der Spiegel, “Only a god can save us” from technology.{3} Kass, an observant Jew, at the end of his chapter on “The Problem of Technology and Liberal Democracy,” intones, “Not for nothing does the Good Book say that the beginning of wisdom is the ‘fear of the Lord.’” And McKibben, recognizing that to say “Enough” constitutes some kind of radical remaking of ourselves, also prescribes a dose of oldtime religion:

This idea of restraint comes in large measure from our religious heritage.... It is Yama, the King of Death, explaining in the Upanishads the choice between jyreya, that which is pleasant, and shreya, that which is beneficial.... It is Jesus, tempted in the desert by the nano-technologist of his day: “If you are the son of God, command these stones to turn into bread.” And refusing, in words that still carry a charge: “Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that pro-ceedeth out of the mouth of God.”

Although these turns toward piety seem to ignore the disasters that the faithful regularly perpetrate, it may not be a mistake to see technology in quasi-theological terms. After all, what happens when the individual declares himself an autonomous moral agent, and with that stroke wipes away any overarching sense of the Good capable of holding together our approbations and condemnations? If there’s no God to please, no Hell to fear or Heaven to aspire toward, then why, aside from purely pragmatic concerns, ought anyone to do (or not do) anything in particular? If there’s no master plan for humanity, and if we have the means at our disposal to do so, then why not take matters into our own hands and rejigger the thing—by, say, stopping the ravages of old age and mortality or taking drugs to ward off existential anxiety?

In a sense, then, there is nothing really new in biotechnology. We’ve been on the operating table since the invention of the wheel, taking matters into our own hands and remaking creation, including ourselves. Technology, with its mediation of all experience, is what we are born into, and trying to find a way out of it, as Kass and McKibben want to do, is as formidable a task as ridding Georgiana of her birthmark. If these writers lapse into sentimentality and nostalgia, that may be only because, similar to the rest of us, they don’t have a way of imagining what technology under human control, technology that doesn’t leave its imprint on human nature, actually looks like.

{1} This is decidedly not the way professional bioethicists tend to view these issues. They prefer to stay close to a trinity of concerns— patient autonomy, physician beneficence, and justice—that are procedural guides for resolving ethical dilemmas.

{2} Even the distinction between unhappiness and depression is much less certain than psychiatrists want to admit. “Clinical depression” is a list of symptoms subjectively assayed; there is no recognizable disease entity.

{3} Scholars disagree about the relationship between Heidegger’s philosophy and his Nazism, but the appeal of an ein Volk politics to a person concerned with modernity’s tendency to uproot is at least plausible.