A depressing story of trauma and complicity in atrocities. Merejildo Grijalva was born in Mexico to the Opata Indian tribe, but he and his mother were kidnapped by Apache Indians when he was a child. After about ten years he fled to the US where he then helped the U.S. Army track down and murder Apaches under the claimed justification of the killings being ‘retaliatory raids’.

If anyone feels like typing up Ted’s Spanish translation, it would be interesting to learn what some Spanish people think of the story and Ted’s translation.

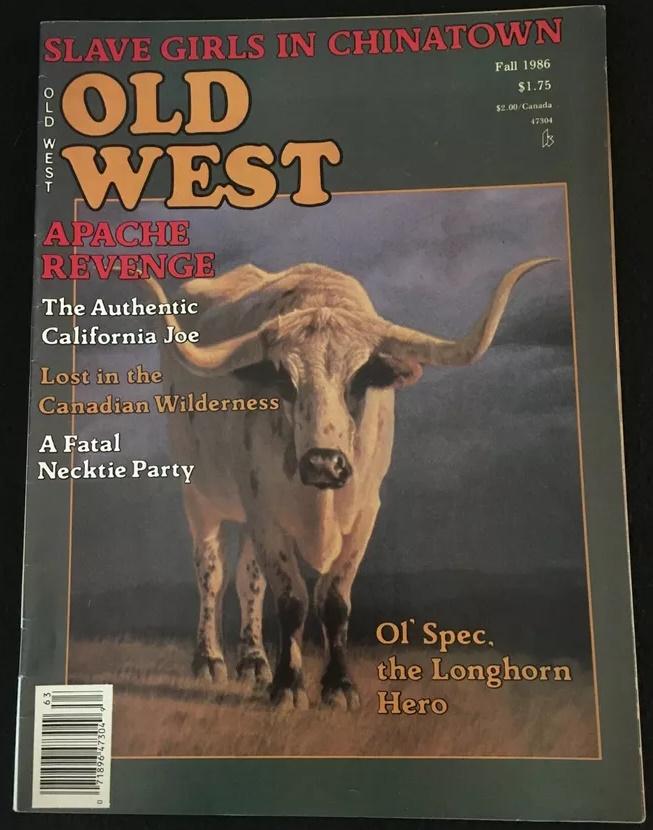

Jacqueline Meketa

Grijalva’s Apache Revenge

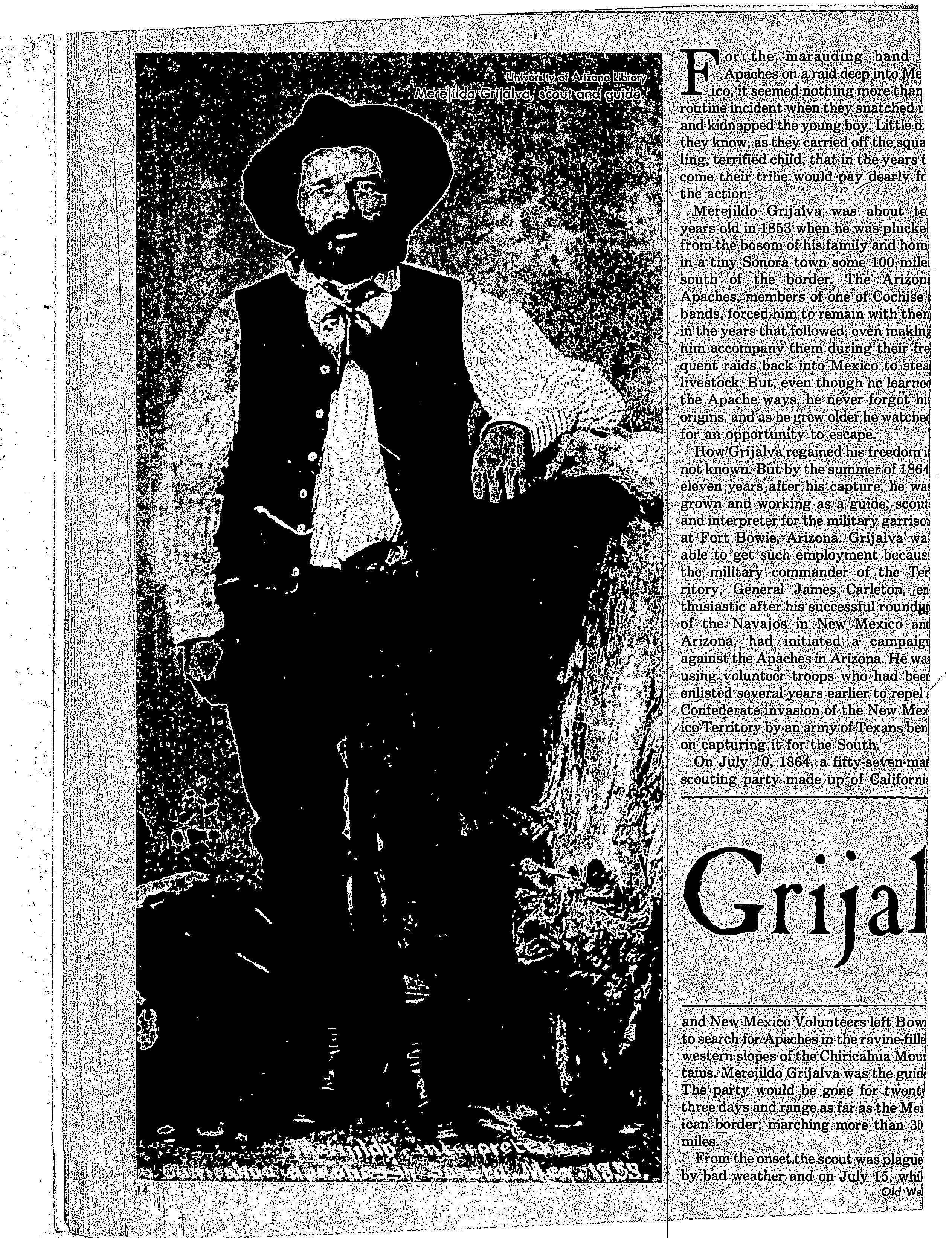

University of Arizona Library

For the marauding band of Apaches on a raid deep into Mexico, it seemed nothing more than a routine incident when they snatched and kidnapped the young boy. Little did they know, as they carried off the squalling, terrified child, that in the years to come their tribe would pay dearly for the action.

Merejildo Grijalva was about ten years old in 1853 when he was plucked from the bosom of his family and home in a tiny Sonora town some 100 miles south of the border. The Arizona Apaches, members of one of Cochise’s bands, forced him to remain with them in the years that followed, even making him accompany them during their frequent raids back into Mexico to steal livestock. But, even though he learned the Apache ways, he never forgot his origins, and as he grew older he watched for an opportunity to escape.

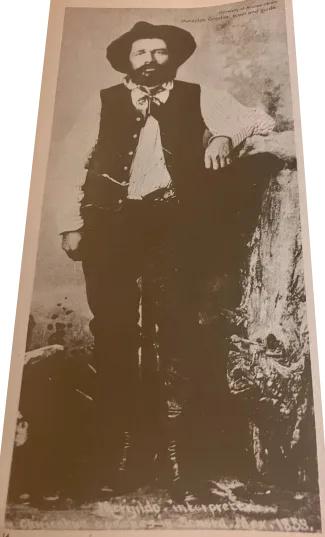

How Grijalva regained his freedom is not known. But by the summer of 1864, eleven years after his capture, he was grown and working as a guide, scout and interpreter for the military garrison at Fort Bowie, Arizona. Grijalva was able to get such employment because the military commander of the Teritory, General James Carleton, enthusiastic after his successful roundup of the Navajos in New Mexico and Arizona, had initiated a campaign against the Apaches in Arizona. He was using volunteer troops who had been enlisted several years earlier to repel the Confederate invasion of the New Mexico Territory by an army of Texans bent on capturing it for the South.

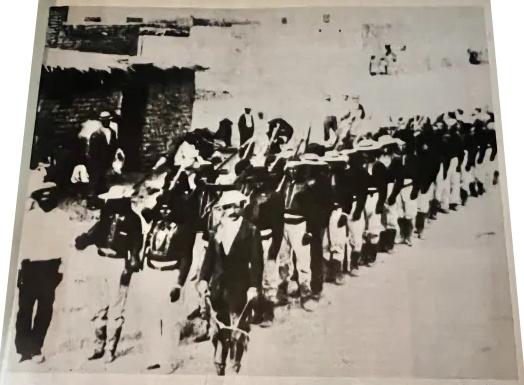

On July 10, 1864, a fifty seven-man scouting party made up of California and New Mexico Volunteers left Bowie to search for Apaches in the ravine-filled western slopes of the Chiricahua Mountains. Merejildo Grijalva was the guide. The party would be gone for twenty three days and range as far as the Mexican border, marching more than 30 miles.

From the onset the scout was plague by bad weather and on July 15, while the soldiers were camped in a heavy downpour, some guards discovered several Indians climbed up a steep mountain about a mile from the camp. Grijalva and a party of twenty-one men were dispatched in pursuit. When they ascended to the area where the Apaches had been seen they were hailed, in Spanish, by a brave standing about 100 feet above them on an almost perpendicular cliff. The Indian shouted down that he was a warrior and a brave one, and he commenced shooting arrows. When the arrows failed to inflict any damage he began to throw rocks, severely bruising the arms of one of the California Volunteers. The troops fired at him and he soon fell. The mortally wounded warrior, called out for Grijalva, whom he had recognized, Grijalva, extremely cautious because of his intimate knowledge of Apache ways, would not approach until he was satisfied the downed man could no longer use his bow and arrows. Grijalva questioned the brave, who refused to divulge anything and soon died. Grijalva identified him as an Apache chief named Old Plume. The scout said the dead man had been guilty of numerous murders and robberies, was sullen and tyrannical among his own people, and was merciless to all others.

The captain in charge of the scouting party, much less knowledgeable about Apaches, viewed Old Plume differently. He speculated that the chief could easily have made his escape and had halted either to cover the retreat of his women and children or because he considered it unworthy of a brave chief to run. In either case, the captain saw it as an act of heroism worthy of admiration “even in an Apache.” ’

The following day, when the troops had traveled only four miles further, they heard Indians hallooing from the cliffs. The commander, sent,Grijalva to .talk to the Apaches and to tell them to’ come into camp and make a treaty! While the troops waited, Grijalva and the Indians, parlayed for four hours. Finally four braves descended as feu- as a grove of trees a mile from the soldiers. One Apache came forward, but not too close. He said some members of their group belonged to Mangas’ band and that the others were with Cochise. He promised they would come into Fort Bowie in eight days to make a treaty. In reality,i the Apaches were only toying with the troops. As the expedition continued they saw the signal fires the Apaches had built along the cliffs ahead of them. This was a sure sign that other Apaches were ahead and were being signaled that the soldiers were on their way.

Over, the next few days, the captain tried various strategies of misdirection and secret ploys to distract the Apaches attention and sneak up on them. None were successful. By July 21, the Apaches had begun taunting.the troops, and the scouting party became aware of two Indians following them on horseback. Again Grijalva was sent out to talk to them. The braves refused to allow him near them until he returned to camp and left his musket, probably an unnecessary demand since Grijalva, was, in fact, an indifferent marksman. Finally one of the Apaches, Ka-eet-sah, an old acquaintance of Grijalva’s, came 1 down to talk, while the other Indian remained back to act as a lookout.

Ka-eet-sah swore there were no Apaches in the mountains except for one small band with him and another little group at another site. He guilefully asked why the troops had gone back to the old camp, referring to one of the captain’s attempted decoy tactics. With equal guile, Grijalva replied their purpose had been to send word to Fort Bowie that the Apaches were coming in within eight days as they had promised and that they were to be received kindly. The. two men briefly continued the lies and banter. The Apache finally agreed to come into the soldiers camp but told Grijalva he wanted to smoke first. The iguide gave the Indian some tobacco and went back to report his success. Ka-eet-sah had his smoke, leisurely enjoying himself, then suddenly jumped, on his horse and rapidly rode off. The outwitted Grijalva was furious with the expedition’s commander, Captain Thomas Tidball. because he hadn’t tried to shoot the deceitful Indians. The rest of the scout was equally unsuccessful. When the party returned to Bowie on August 1, they could take satisfaction only in having kept the Indians occupied and on guard. In his report to headquarters, Captain Tidball acknowledged that Grijalva was thoroughly acquainted with the Chiricahua. Mountains and the habits of the Apaches. But he stated that the guide was “constitutionally timid, knowing as he did, the terrible fate awaiting him if he were ever captured.” He said Grijalva would not venture out of sight of the soldiers and, “if he was compelled to go he allowed his’ fears to overcome his judgement and his regard for the truth.”

Arizona Historical Society

JUST A YEAR or two later, however, another, officer evaluated Grijalva’s character much more charitably. After citing his abilities as an excellent and knowledgeable guide, expert tracker, and responsible leader of the scouting parties, the officer said, he also had a wholesome fear of falling into the hands of the Apaches alive, citing Grijalva’s knowledge that the Indians would recognize him, consider him a turncoat, and reserve their most exquisite tortures for him. He continued, “Of course, if he could prevent it, he would never be taken alive by them, and he strictly adhered to the right rule observed by everyone in those days to always keep one bullet in reserve.”

U.S. Military History institute, Carlisle Barracks

The military apparently was well satisfied with Grijalva’s work. Fort Bowie records show that the following year, in November 1865, still acting as a guide, spy, and scout, Grijalva led thirty-two volunteers from the post to an Indian rancheria about forty-five miles away. They attacked and killed seventeen Apaches and wounded a number of others. In addition some , livestock was captured and the Indians’ winter stores and provisions were destroyed.

By 1866 the California and New Mexico volunteers were gone, having been mustered out when their enlistments were completed. They were replaced by Regular Army troops, and Grijalva was hired to continue as Indian guide and scout. In short order they set out to establish Camp Wallen on the upper San Pedro River, about nineteen miles from Huachuca Pass. Grijalva accompanied them. He built himself a small adobe , house, moved his wife in, and was enjoying all the marital comforts while the troopers were still living under canvas.

One day in October the camp was roused to action when a wounded man was brought in lying in a wagon. A United States mail rider, he had been waylaid by Apaches in an arroyo near the Patagonia mines. They shot him, shattering his kneecap. The Army-surgeon amputated his leg.

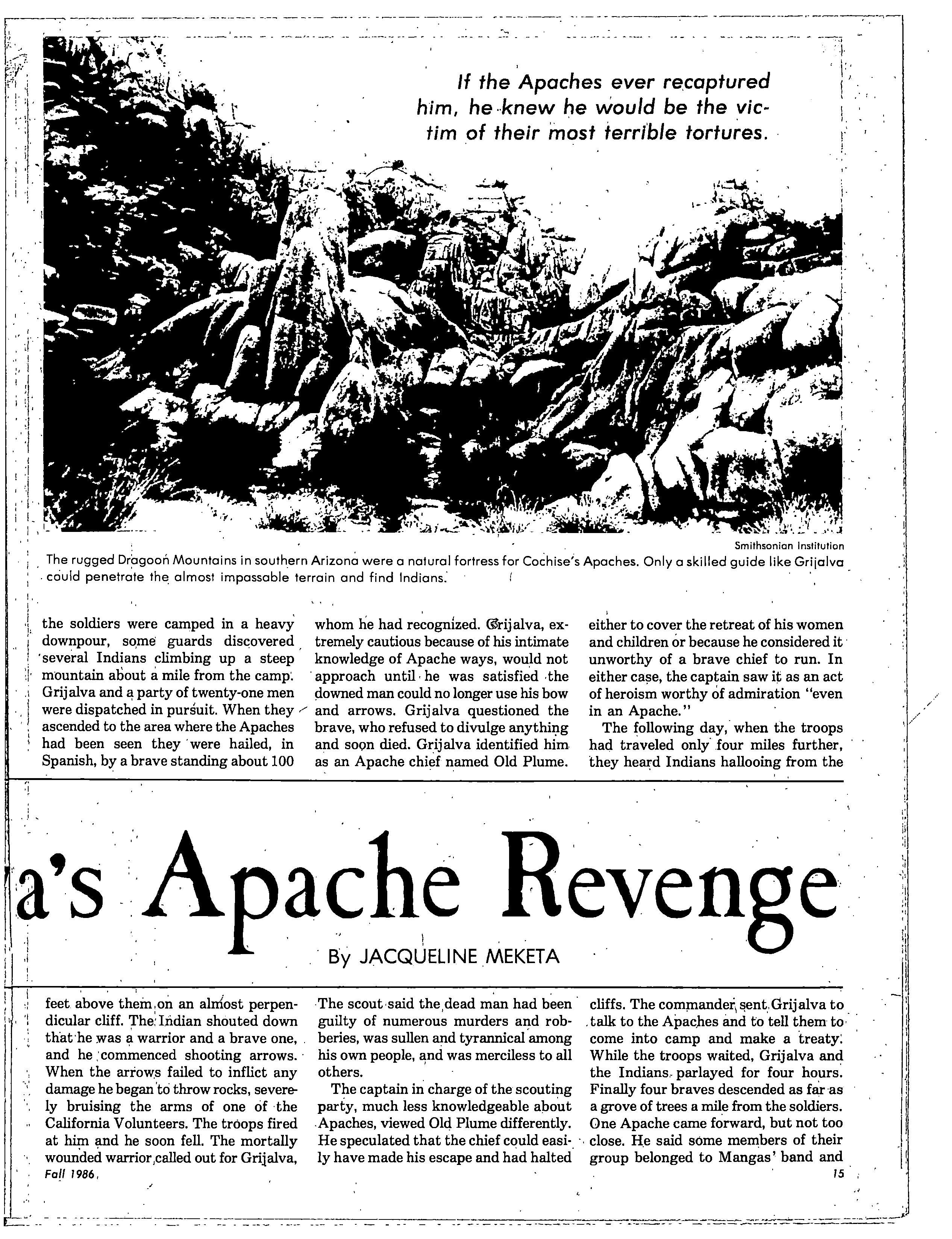

Since more than four days had elapsed since the incident, the camp’s commanding officer consulted with Grijalva about the feasibility of sending a scouting expedition to track down the Apache culprits. Grijalva thought his familiarity with the Apaches’ probable escape route, gained whife he was their captive, would enable him to lead the soldiers to them. A party of twenty-five men set out. They followed the Indians’ tracks from the Patagonia mines, over the foothills on the south side of the Huachuca Mountains, across the San Pedro River, and toward the Dragoon Mountains. Before reaching the Dragoons, the Indians turned sharply east toward the Chiricahuas, where Grijalva knew they always maintained a rancheria and rendezvous point.

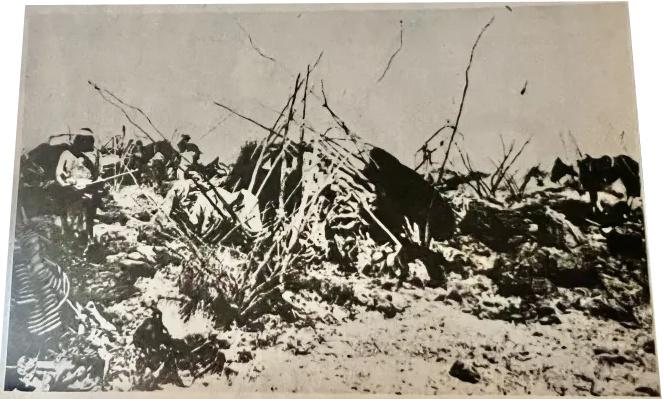

ON THE MORNING of their sixth day out. the soldiers suddenly came upon a squaw getting water in the mouth of a hidden canyon. When she spotted them she raised an alarm. The twenty-five Apaches camped nearby ran from their huts and scampered up the steep, rocky canyon walls like mountain goats. The soldiers quickly dismounted and followed, but it was an uneven contest. Even the Apache women who carried children on their backs leaped from boulder to boulder among the cactus and lava rocks. Stopping from time to time they taunted and insulted the more awkward soldiers, who were laboring upward. Shouting in Spanish, the Apaches used a profane and obscene vocabulary interspersed with the most obviously indecent gestures. The Indians paid particular attention to Grijalva, for many of them recognized him from earlier days. They not only vilified him but also let him know in no uncertain terms what terrible punishments awaited him if they ever laid hands on him.

As the first of the Apaches disappeared over the brow of the hill, Grijalva urged the lieutenant in charge to discontinue the chase upward and return to the canyon floor, where they had left their mounts in the care of several troopers. It was excellent advice. They descended just in time to ward off a number of wily Apaches who had rapidly climbed back down the other side of the ridge and circled back in an attempt to stampede the soldiers’ horses. Because of Grijalva’s expertise, the troops not only retained their mounts but also were able to destroy the rancheria and its stores of food, blankets, and weapons.

About a year later in November 1867, Grijalva again made the Apaches sorry he had ever been kidnapped and taught their ways. A wounded Mexican trader staggered into Camp Wallen. He and his party had been attacked by Apaches in the middle of Huachuca Pass, nineteen miles distant. Immediately ’’boots and saddles” was sounded by the bugler. A party of .thirty soldiers, guided by Grijalva left for the site of the massacre. They found the terribly mutilated bodies of the other three traders where the attack had occurred. Nearby, Grijalva easily located the Apache tracks. They indicated that eight or nine Indians had headed south, driving some stolen oxen before them.

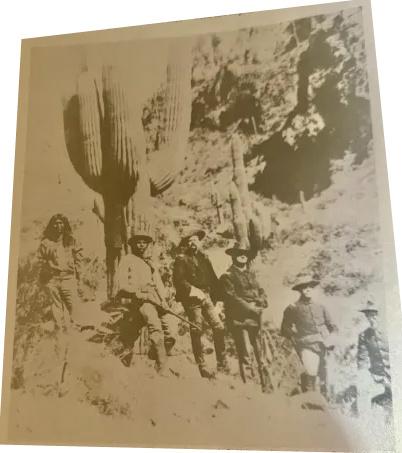

Smithsonion Institution

For four days Grijalva followed the Indians’ tracks, often picking them up again, many, miles after they disappeared in rocky 6r hard packed terrain or in running, streams. Over hills and through steep canyons the troopers followed Grijalva, who allowed no cooking, fires, little rest, and no noise. As the Apaches neared the Chiricahua Mountains they split, into two equal groups. Grijalva’ followed, one set of tracks. After hours of patient, almost silent maneuvering, the soldiers surprised the Apaches. Two of the braves were chased by soldiers on horseback and cut down « by gunfire after nearly reaching the’ mountains. The third warrior’s thigh-; bone had been fractured by a soldier’s bullet in the first fusillade. He crawled into a large fissure and shot arrows at the dismounted soldiers who were firing at him.

Grijalva, returning from helping hunt down the other two Apaches, approached the fissure from the rear. He signaled the soldiers to hold their fire, crawled to the edge of the hole, thrust his revolver in and dispatched the Apache with’ a shot to the head.

Later, unobserved by any of the soldiers, Grijalva sneaked away, and scalped the three dead braves for proof; a civilian hay contractor in the area had promised him $100 for each Indian he killed.

THIS GRIM picture of Merejildo Grijalva had another side. He was warm and friendly and had a sense, of humor. At Camp Wallen he became friends with several of the military men, communicating with them in his broken English. One young lieutenant, smitten by the exceptionally beautiful daughter of a nearby Mexican family,- asked Grijalva for help. For some time,- he had tried unsuccessfully to learn Spanish from the guide so he could-impress the girl. Now he decided.it would be very romantic if he and a friend could learn a simple, Spanish love .song, one they could sing phonetically to the senorita while he accompanied himself on his violin. He wanted Grijalva, who sang quite well, to teach them the words.

The lieutenant was overjoyed to find that no persuasion was necessary. Grijalva enthusiastically agreed to help. For four consecutive days the troubadours practiced ,in two hour, sessions. Over and over again they repeated the foreign lyrics of the tune, which Grijalvi assured them was a love song that would create a great sensation when sung for the Mendoza family and; their daughter.

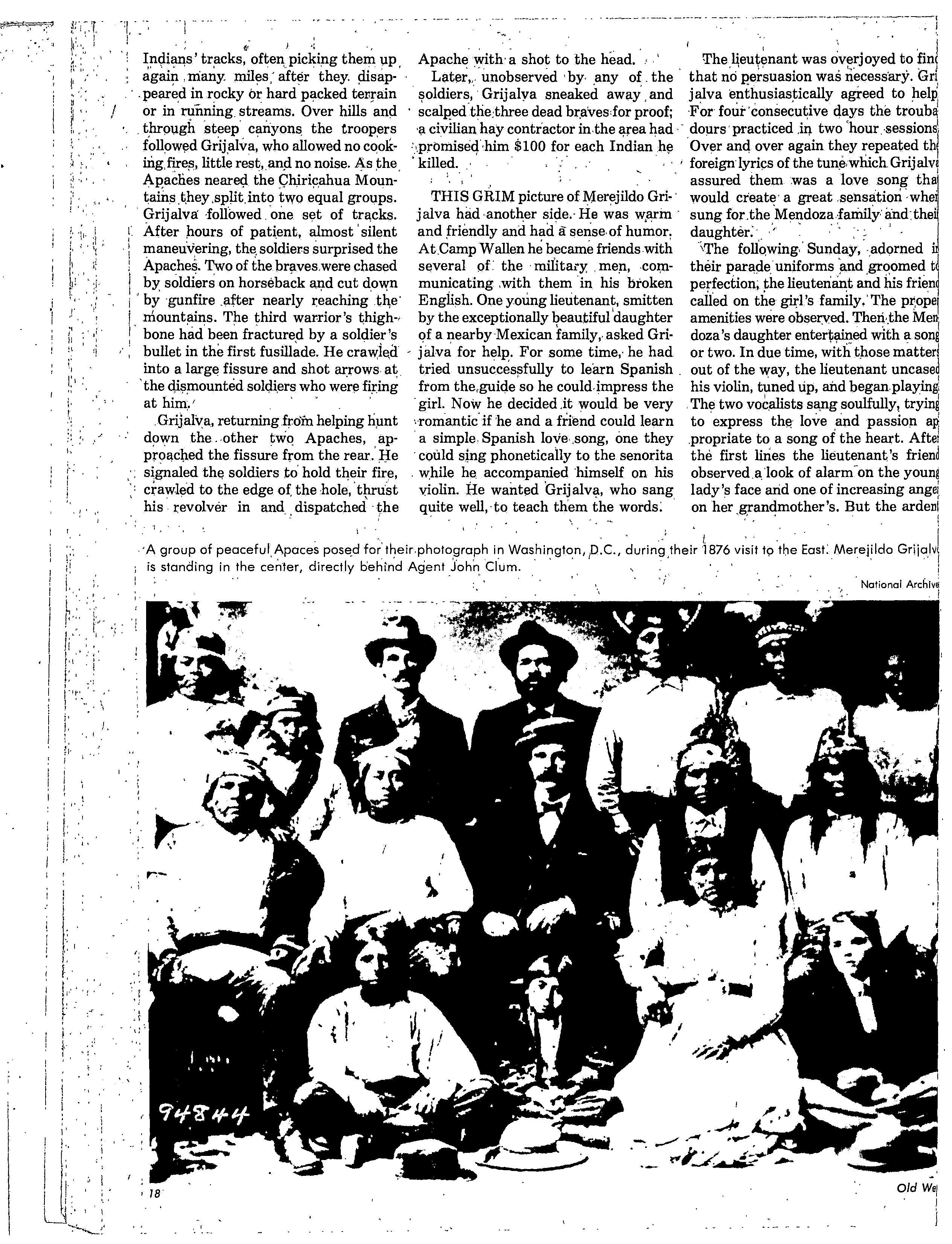

National Archive

The following, Sunday, adorned in their parade uniforms and groomed to perfection, the lieutenant and his friend called on the girl’s family. The proper amenities were observed. Then the Mendoza’s daughter entertained with a song or two. In due time, with those matters out of the way, the lieutenant uncased his violin, tuned lip, and began playing. The two vocalists sang soulfully, trying to express the love and passion appropriate to a song of the heart. After the first lines the lieutenant’s friend observed a look of alarm on the young lady’s face arid one of increasing angel on her grandmother’s. But the ardes officer, busy watching his uncertain fingering. of the strings, missed the telltale signs! and continued to play and sing.

National Archives

BY THE TIME the men had begun the third Tine of the ballad, the distraught-young lady had covered her blushing face with her shawl. Her indignant family was ready to do great bodily harm to two uncouth louts warbling a distasteful ditty. As the girl’s father approached, ax in hand, the two young soldiers bolted for the door and hared down the hill. They were followed by the ax, a firebrand, and the violin case. Not far away, behind a large boulder, they found; Grijalva so overcome with glee that he could no longer stand but was rolling on the ground in uncontrollable laughter. Only after, a drubbing did he I agree; to visit the irate ‘family, explain the whole matter, and make things right once more.

Merejildo Grijalva led many scouts against the Apaches and continued to work, for the government for many years, Records show he was an interpreter at the San Carlos Indian Reservation in 1873 when First Lieutenant Jacob Almy was killed by several renegade Apaches on a day when rations were distributed.

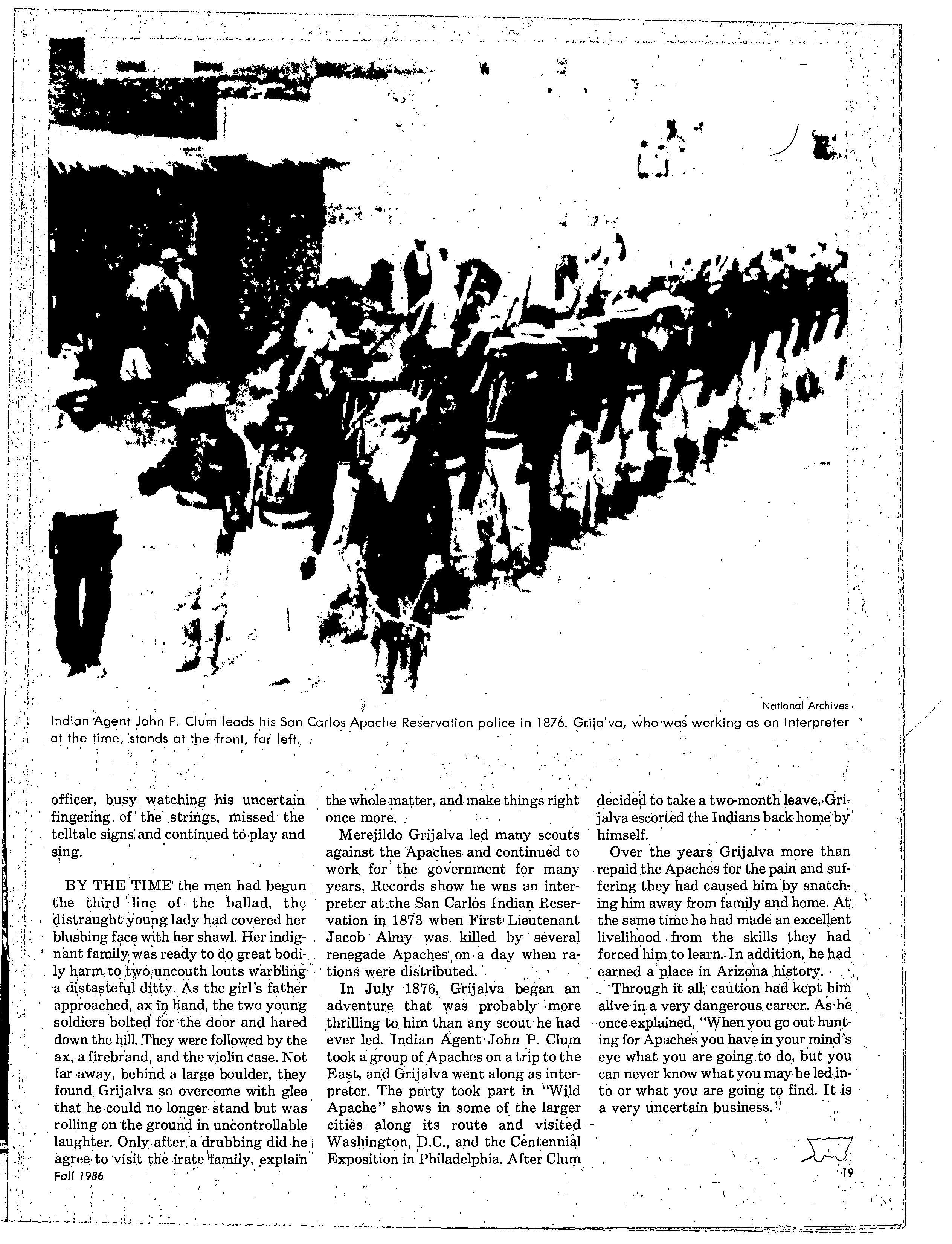

In July 1876, Grijalva began an adventure that was probably more thrilling to him than any scout he had ever led. Indian Agent John P. Clum took a group of Apaches on a trip to the East, and Grijalva went along as interpreter. The party took part in “Wild Apache” shows in some of the larger cities along its route and visited Washington, D.C., and the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. After Clum decided to take a two-month leave, Grijalva escorted the Indian’s back home by, himself.

Over the years Grijalva more than repaid the Apaches for the pain and suffering they had caused him by snatching him away from family and home. At the same time he had made an excellent livelihood from the skills they had forced him to learn. In addition, he had earned a place in Arizona history.

Through it all, caution had kept him , alive in. a very dangerous career. As he once explained, “When you go out hunting for Ap ache’s you have in your mind’s eye what you are going, to do, but you can never know what you maybe led into or what you are going to find. It is a very uncertain business.”

Ted’s Spanish Translation

La Venganza de Grijalva en los Apaches

por

Jacqueline Meketa

A la banda merodeodora de Apaches bien adentrada en Mexico, no les parecia sino un incidente rutinario al nino. Al llevarselo al chico aterrado y griton, no tenian la menor idea de que en los anos venideros la tribu pagaria caro esa accion.

Merejildo Grijalva tenia cerca de diez anos en 1853 cuando se le arrebato al seno de su familia y hogar en una pequenita aldea de Sonora unas cien millas al sur de la frontera estadounidense. Esos apaches de Arizona, miembros de una de las badas de Cochise, le forzaron a permanecer con ellos durante los anos siguientes y aun le hicieron acompanarlos en sus frecuentes correrias en Mexico para hurtar qanado. Pero, aunque aprendio las costumbres y tecnicas de los apaches, nunca olvido su origen, y a medida que crecia, buscaba una opurtunidad de escaparse.

No se sabe como recobro Grijalva su libertad. Pero antes del verano de 1864, a los once anos de ser capturado, estaba crecido y trabajaba de guia, explorador y interprete por la guarnicion de Fort Bowie, Arizona. Grijalva pudo obtener tal empleo porque el comandante militar del territorio, el General Games Carleton, entusiasmado con el buen exido de su redada para prender a los Navajos en Nuevo Mexico por un ejercito de tejanos que se empenaban en conquestarlo por los Estados Confederados....