Gus Tyler

Can Anyone Run a City?

Gus Tyler, assistant president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, is author of The Political Imperative: The Corporate Character of Unions, published last year by Macmillan, and a frequent contributor to magazines and other periodicals. He is currently writing a book on labor in the metropolis.

Can anyone run a city? For scores of candidates who have run for municipal office across the nation this week, the reply obviously is a rhetorical yes. But if we are to judge by the experiences of many mayors whose terms have brought nothing but failure and despair, the answer must be no. “Our association has had a tremendous casualty list in the past year,” noted Terry D. Schrunk, mayor of Portland, Oregon, and president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors. “When we went home from Chicago in 1968, we had designated thirty-nine mayors to sit in places of leadership.... Today, nearly half of them are either out of office or going out ... most of them by their own decision not to run again.” Since that statement, two of the best mayors in the country—Jerome P. Cavanagh of Detroit and Richard C. Lee of New Haven—have chosen not to run again.

Why do mayors want out? Because, says Mayor Joseph M. Barr of Pittsburgh, “the problems arc almost insurmountable. Any mayor who’s not frustrated is not thinking.” Thomas G. Currigan, former mayor of Denver, having chucked it all in mid-term, says he hopes “to heaven the cities are not ungovernable, [but] there are some frightening aspects that would lead one to at least think along these lines.” The scholarly Mayor Arthur Naftalin of Minneapolis adds his testimony: “Increasingly, the central city is unable to meet its problems. The fragmentation of authority is such that there isn’t much a city can decide anymore: it can’t deal effectively with education or housing.”

Above all, the city cannot handle race. Cavanagh, Naftalin, and Lee— dedicated liberal doers all—were riot victims. Mayor A. W. Sorensen of Omaha had to confess that after he’d “gone through three-and-a-half years in this racial business,” he’d had it.

Although frictions over race relations often ignite urban explosives, the cities of America—and the world—are proving ungovernable even where they are ethnically homogeneous. Tokyo is in hara-kiri, though racially pure. U Thant, in a statement to the U.N.‘s Economic and Social Council, presented the urban problem as world-wide: “In many countries the housing situation ... verges on disaster.... Throughout the developing world, the city is failing badly.”

What is the universal malady of cities? The disease is density. Where cities foresaw density and planned accordingly, the situation is bad but tolerable. Where exploding populations hit unready urban areas, they are in disaster. Where ethnic and political conflict add further disorder, the disease appears terminal.

Some naturalists, in the age of urban crisis, have begun to study density as a disease. Crowded rats grow bigger adrenals, pouring out their juices in fear and fury. Crammed cats go through a “Fascist” transformation, with a “despot” at the top, “pariahs” at the bottom, and a general malaise in the community, where the cats, according to P. Leyhausen, “seldom relax, they never look at ease, and there is continuous hissing, growling, and even fighting.”

How dense are the cities? The seven out of every ten Americans who live in cities occupy only 1 per cent of the total land area of the country. In the central city the situation is tighter, and in the inner core it is tightest. If we all lived as crushed as the blacks in Harlem, the total population of America could be squeezed into three of the five boroughs of New York City.

This density is, in part, a product of total population explosion. At some point the whole Earth will be as crowded as Harlem—or worse—unless we control births. But, right now, our deformity is due less to overall population than to the lopsided way in which we grow. In the 1950s, half of all the counties in the U.S. actually lost population; in the 1960s, four states lost population. Where did these people go? Into cities and metropolitan states. By the year 2000, we will have an additional 100 million Americans, almost all of whom will end up in the metropolitan areas.

The flow of the population from soil to city has been underway for more than a century, turning what was once a rural nation into an urban one by the early 1900s. Likewise, the flow from city to suburb has been underway for almost half a century. “We shall solve the city problem by leaving the city,” advised Henry Ford in a high-minded blurb for his flivver. But, in the past decade, the flow has become a flood. Modern know-how dispossessed millions of farmers, setting in motion a mass migration of ten million Americans from rural, often backward, heavily black and Southern counties to the cities. They carried with them all the upset of the uprooted, with its inherent ethnic and economic conflict. American cities, like Roman civilization, were hit by tidal waves of modern Vandals. Under the impact of this new rural-push/urban-pull, distressed city dwellers started to move—then to run—out. Hence, the newest demographic dynamic: urban-push and suburban-pull. In the 1940s, half the metropolitan increase was in the suburbs; in the 1950s, it was two-thirds; in the 1960s, the central cities stopped growing while the suburbs boomed.

Not only people left the central city; but jobs, too, thereby creating a whole new set of economic and logistic problems. Industrial plants (the traditional economic ladder for new ethnic populations) began to flee the city in search of space for factories with modern horizontal layouts. Between 1945 and 1965, 63 per cent of all new industrial building took place outside the core. At present, 75 to 80 per cent of new jobs in trade and industry are situated on the metropolitan fringe. In the New York metropolitan area from 1951 to 1965, 127,753 new jobs were located in the city while more than three times that number (387,873) were located in the suburbs. In the Philadelphia metropolis, the city lost 49,461 jobs, while the suburbs gained 215,296. For the blue-collar worker who could afford to move to the suburbs or who could commute (usually by car) there were jobs. For those who were stuck in the city, the alternatives were work in small competitive plants hungry for cheap labor and no work at all.

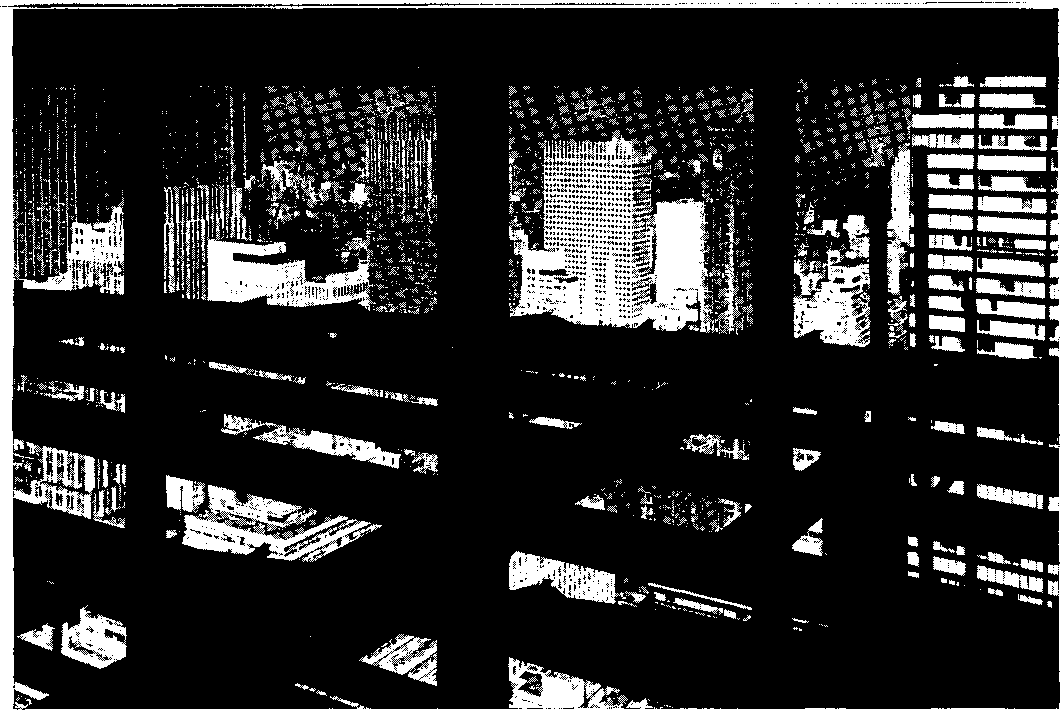

Ironically, the worthwhile jobs that did locate in the cities were precisely those most unsuited for people of the inner core, namely, white-collar clerical, administrative, and executive positions. These jobs locate in high-rise office buildings with their vertical complexes of cubicles, drawing to them the more affluent employees who live in the outskirts and suburbs.

“Increasingly, the central city is unable to meet its problems.”

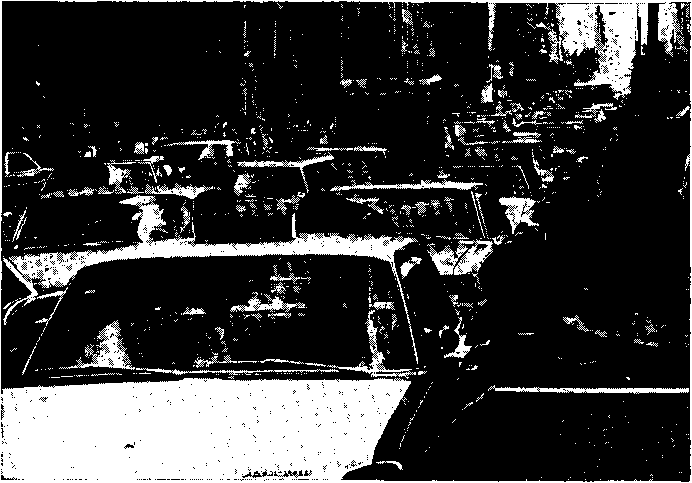

This disallocation of employment, calling for daily commuter migrations, has helped turn the automobile from a solution into a problem, as central cities have become stricken with autoimmobility; in midtown New York, the vehicular pace has been reduced from 11.5 mph in 1907 to 6 mph in 1963. To break the traffic jam, cities have built highways, garages, and parking lots that eat up valuable (once taxable) space in their busy downtowns: 55 per cent of the land in central Los Angeles, 50 per cent in Atlanta, 40 per cent in Boston, 30 per cent in Denver. All these “improvements,” however, encourage more cars to come and go, leaving the central city poorer, not better.

Autos produce auto-intoxication: poisoning of the air. While the car is not the only offender (industry causes about 18 per cent of pollution; electric generators, 12 per cent; space heaters, 6 per cent; refuse disposal, 2.5 per cent), it is the main menace spewing forth 60 per cent of all the atmospheric filth. In 1966, a temperature inversion in New York City—fatefully coinciding with a national conference on air pollution—brought on eighty deaths. In 1952, in London, 4,000 people died during a similar atmospheric phenomenon.

The auto also helped to kill mass transit, the rational solution to the commuter problem. The auto drained railroads of passengers; to make up the loss, the railroads boosted fares; as fares went up, more passengers turned to autos; faced with bankruptcy, lines fell behind in upkeep, driving passengers to anger and more autos. Between 1950 and 1963, a dozen lines quit the passenger business; of the 500 intercity trains still in operation, fifty have applied to the ICC for discontinuance. Meanwhile, many treat their passengers as if they were freight.

Regional planners saw this coming two generations ago and proposed networks of mass transportation. But the auto put together its own lobby to decide otherwise: auto manufacturers, oil companies, road builders, and politicians who depend heavily on the construction industry for campaign contributions.

The auto is even failing in its traditional weekend role as the means to get away. On a hot August weekend this year, Jones Beach had to close down for a full hour, because 60,000 cars tried to get into parking lots with a capacity of 24,000. The cars moved on to the Robert Moses State Park and so jammed the 6,000-car lot there as to force a two-hour shutdown.

Overcrowding of the recreation spots is due not only to more people with more cars but to the pollution of waters by the dumping of garbage—another by-product of metropolitan density.

Viewed in the overall, our larger metropolises with their urban and suburban areas are repeating the gloomy evolution of our larger cities. When Greater New York was composed of Manhattan (then New York) and the four surrounding boroughs, the idea was to establish a balanced city: a crowded center surrounded by villages and farms. In the end, all New York became citified. Likewise, the entire metropolitan area is becoming urbanized with the suburbanite increasingly caught up in the city tangle.

“The auto drained railroads of passengers; to make up the loss, the railroads boosted fares; as fares went up, more passengers turned to autos ...”

The flow from city to suburb does not, surprisingly, relieve crowding within the central city, even in those cases where the city population is no longer growing. The same number of people—especially in the poor areas— have fewer places to live. In recent years, some 12,000 buildings that once housed about 60,000 families in New York City have been abandoned, with tenants being dispossessed by derelicts and rats; 3,000 more buildings are expected to be abandoned this year. The story of these buildings, in a city such as New York, reads like a Kafkaesque comedy. For the city to tear down even one of these menaces involves two to four years of red tape; to get possession of the land takes another two to four years. Meanwhile, the wrecks are inhabited by human wrecks preparing their meals over Sterno cans that regularly set fire to the buildings. By law, the fire department is then charged with the responsibility of risking men’s lives to put out the fire, which they usually can do. However, when the flames get out of hand, other worthy buildings are gutted, leaving whole blocks of charred skeletons—victims of the quiet riot.

Other dwellings are being torn down by private builders to make way for high-rise luxury apartments and commercial structures. Public action has destroyed more housing than has been built in all federally aided programs. As a result, the crowded are more crowded than ever. Rehabilitation instead of renewal doesn’t work. New York City tried it only to discover that rehabilitation costs $38 a square foot— a little more than new luxury housing.

The result of all this housing decay and destruction (plus FHA money to encourage more affluent whites to move to the suburbs) has been, says the National Commission on Urban Problems, “to intensify racial and economic stratification of America’s urban areas.”

While ghetto cores turn into ghost towns, the ghetto fringes flare out. The crime that oozes through the sores of the diseased slum chases away old neighbors, a few of whom can make it to the suburbs; the rest seek refuge in the “urban villages” of the low-income whites. Cities become denser and tenser than they were. In the process, these populous centers of civilization become—like Europe during the Dark Ages—the bloody soil on which armed towns wage their inevitable wars over a street, a building, a hole in the wall. Amid this troubled terrain, the freelance criminal adds to the anarchy.

All these problems (plus welfare, schooling, and militant unions of municipal employees) hit the mayors at a time when, according to the National Commission on Urban Problems, “there is a crisis of urban government finance ... rooted in conditions that will not disappear but threaten to grow and spread rapidly.” The “roots” of the “crisis”? The mayor starts with a historic heavy debt burden. His power to tax and borrow is often tethered by a rural-minded state legislature. He has lost many of the city’s wealthy payers to the suburbs. His levies on property (small homes) and sales are prodding Mr. Middle to a tax revolt. The bigger (richer) the city is, the worse off it is. As population increases, per capita cost of running a city goes up—not down: density makes for frictions that demand expensive social lubricants. Municipalities of 100,000 to 299,000 spend $14.60 per person on police; those of 300,000 to 490,000 spend $18.33; and those of 500,000 to one million spend $21.88. New York City spends $39.83. On hospitalization, the first two categories spend $5 to $8 per person; those over 500,000 spend $12.54; New York spends $55.19.

Expanding the economy of a city does not solve the problem; it makes it worse. Several scholarly studies have come up with this piece of empiric pessimism: if the gross income of a city goes up 100 per cent, revenue rises only 90 per cent, and expenditures rise 110 per cent. Consequently, when a city’s economy grows, the city’s budget is in a worse fix than before. This diseconomy of bigness and richness applies even when cities merely limit themselves to prior levels of services. But cities, unable to cling to this inadequate past, have had to step up services to meet the rising expectations of city dwellers.

The easy out for a mayor is to demand that the federal coffers take over cost or hand over money. But is that the real answer? The federal income tax as presently levied falls most heavily on an already embittered middle class—our alienated majority. Unable to push this group any harder and unwilling to “soak the rich,” an administration, such as President Nixon’s, comes up with revenue-sharing toothpicks with which to shore up mountains. Nixon has proposed half a billion for next year and $5-billion by 1975, while urban experts see a need for $20- to $50-billion each year for the next decade. A Senate committee headed by Senator Abe Ribicoff calls for a cool trillion.

But even if a trillion were forthcoming, it might be unable to do the job. To build, a city must rebuild: bulldoze buildings, redirect highways, clear for mass transportation, remake streets— a tough task. But even tougher, a city must bulldoze people who arc rigidified in resistant economic and political enclaves. The total undertaking could be more difficult than resurrecting a Phoenix that was already nothing but a heap of ashes.

What powers does a mayor bring to these complex problems? Very few. Many cities have a weak mayor setup, making him little more than a figurehead. If he has power, he lacks money. If he has power and money, he must find real—not symbolic—solutions to problems in the context of a density that turns “successes” into failures. If a mayor can, miraculously, come up with comprehensive plans, they will have to include a region far greater than the central city where he reigns.

A mayor must try to do all this in an era of political retribalism, when communities are demanding more, not less, say over the governance of their little neighborhoods. In this hour, when regional government is needed to cope with the many problems of the metropolitan area as a unity, the popular mood is to break up and return power to those warring factions—racial, economic, religious, geographic— that have in numerous cases turned a city into a no man’s land.

Is there then no hope? There is—if we putter less within present cities and start planning a national push-pull to decongest urban America. Our answer is not in new mayors but in new cities; not in urban renewal but in urban “newal,” to use planner Charles Abrams’s felicitous word.

We cannot juggle the 70 per cent of the American people around on 1 per cent of the land area to solve the urban mess. We are compelled to think in terms of new towns and new cities planned for placement and structure by public action with public funds. “All of the urbanologists agree,” reported Time amidst the 1967 riot months, “that one of the most important ways of saving cities is simply to have more cities.” The National Committee on Urban Growth Policy proposed this summer that the federal government embark on a program to create 110 new cities (100 having a population of 100,000, and ten even larger) over the next three decades. At an earlier time, the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations proposed a national policy on urban growth, to use our vast untouched stock of land to “increase, rather than diminish, Americans’ choices of places and environments,” to counteract our present “diseconomies of scale involved in continuing urban concentration, the locational mismatch of jobs and people, the connection between urban and rural poverty problems, and urban sprawl.”

New towns would set up a new dynamic. In the central cities, decongestion could lead to real urban renewal, starting with the clearing of the ghost blocks where nobody lives and ending with open spaces or even some of those dreamy “cities within a city.” The new settlements could be proving grounds for all those exciting ideas of city planners whose proposals have been frustrated by present structures —physical and political. “Obsolete practices such as standard zoning, parking on the street, school bussing, on-street loading, and highway clutter could all be planned out of a new city,” notes William E. Finley in the Urban Growth report. These new towns (cities) could bring jobs, medicine, education, and culture to the ghost towns in rural America, located in the counties that have lost population—and income—in the past decades. Finally, a half-century project for new urban areas would pick up the slack in employment when America, hopefully, runs out of wars to fight.

The cost would be great, but no greater than haphazard private developments that will pop up Topsy-like to accommodate the added 100 million people who will crowd America by the year 2000. Right now we grow expensively by horizontal or vertical accretion. We sprawl onto costly ground, bought up by speculators and builders looking for a fast buck. Under a national plan, the federal government could buy up a store of ground in removed places at low cost or use present government lands. Where private developers reach out for vertical space, they erect towers whose building costs go up geometrically with every additional story. On the other hand, as city planners have been pointing out for a couple of decades, “it has been proved over and over again by such builders as Levitt, Burns, and Bohannon” that efficient mass production of low-risers “can and do produce better and cheaper houses.” Cliff dwellings cost more than split-levels.

The idea of new towns is not untested. “There is little precedent in this country, but ample precedent abroad,” notes the Committee on Urban Growth. “Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, the Scandinavian countries—all have taken a direct hand in land and population development in the face of urbanization, and all can point to examples of orderly growth that contrast sharply with the American metropolitan ooze.” To the extent that the U.S. has created new communities it has done so as by-products: Norris, Tennessee, was built for TVA to house men working on a dam; Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Hanford were built for the Atomic Energy Commission “to isolate its highly secret operations.”

What then is the obstacle to this new-cities idea? It runs contrary to the traditional wisdom that a) where cities are located, they should be located, and b) that the future ought to be left to private enterprise. Both thoughts are a hangover from a hang-up with laissez faire, a Panglossian notion that what is, is best.

The fact is, however, that past reasons for locating cities no longer hold—at least, not to the same extent. Once cities grew up at rural crossroads; later at the meeting of waters; still later at railroad junctions; then near sources of raw material. But today, as city planner Edgardo Contini testified before a Congressional committee, these reasons are obsolete. “Recent technological and transportation trends—synthesis rather than extraction of materials, atomic rather than hydroelectric or thermoelectric power, air rather than rail transportation—all tend to expand the opportunities for location of urban settlements.” Despite this, the old cities, by sheer weight of existence, become a magnetic force drawing deadly densities.

Furthermore, concluded Mr. Contini and a host of others, “the scale of the new cities program is too overwhelming for private initiative alone to sustain, and its purposes and implications are too relevant to the country’s future to be relinquished to the profit motive alone.” The report of the Urban Growth Committee stresses the limited impact of new towns put up by private developers such as Columbia, Maryland and Reston, Virginia. “They are, and will be, in the first place, few in number, serving only a tiny fraction of total population growth. A new town is a ‘patient’ investment, requiring large outlays long before returns begin; it is thus a non-competitive investment in a tight money market. Land in town-size amounts is hard to find and assemble without public powers of eminent domain. Privately developed new towns, moreover, by definition must serve the market, which tends to fill them with housing for middle- to upper-income families rather than the poor.”

The choice before America is really not between new cities and old. Population pressure will force outward expansion. But by present drift, this will be unplanned accretion—plotted for quick profit rather than public need. What is needed is national concern for the commonweal in the location and design of new cities: a kind of inner space program.