Helen Lackner

P.D.R. Yemen

Outpost of Socialist Development in Arabia

Chapter One: The Colonial Period

The Rationale of British occupation

Southern Yemen from the 1850s to the First World War

The transformation of the hinterland

Intervention in the interior from the 1930s onwards

Constitutional changes in the 1950s and the Federation of South Arabia

Chapter Two: The development of nationalism and the struggle for independence

2. The Aden Trade Union Congress and the People’s Socialist Party

Anti-British movements in the hinterland

1. The Origins of the National Liberation Front

4. The Conflict with FLOSY and victory

Conclusion: The NLF takes power

Chapter Three: The first 10 Years of Independence

1. The Fourth Congress of the NLF

The Corrective Move and the Fifth Congress

1. The 22 June Corrective Move

2. The first years of Revolutionary Government

6. Relations with the Northern Part of the Homeland

UPONF and the Power Struggle 1975–78

2. Decline and fall of Salmine: the 26 June events

Chapter Four: The State in the 1980s

The Presidency of Abdul Fattah Ismail

1. The First Congress of the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP)

3. The question of Yemeni Unity

4. The ‘Retirement’ of Abdul Fattah Ismail

The leadership of Ali Nasser Mohammed

1. The Extraordinary Congress of the Yemeni Socialist Party

2. The development of the Party

5. Recent developments in foreign relations

1. Representative and mass organisations

Chapter Five: The Transformation of Society.

Chapter Six: Social Policies and their Influence on Social Change

1. Initial situation and problems

3. Developments in health since independence

2. Economic policy of the First Congress of the YSP

3. The Second Five Year Plan and the Extraordinary General Congress of the YSP.

The Second Five Year Plan, how is it doing?

Agriculture before independence

Independence and the Agrarian Reform

The problems of agriculture and new policies for the 1980s

Agricultural and self sufficiency

Chapter Nine: Fisheries and Industry

1. Development of the fisheries cooperatives

2. The Industrial Fleet, and Fish Processing

2. Industry before Independence

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

P.D.R. Yemen

Outpost of

Socialist Development

in Arabia

Helen Lackner

Ithaca Press London 1985

[Copyright]

® 1985 Helen Lackner

First published in 1985 by

Ithaca Press 13 Southwark Street London SEI IRQ

Printed in England by

Biddles Ltd, Guildford & King’s Lynn

Typeset by EMS Photosetters Rochford Essex

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lackner, Helen

PDRYemen: outpost of socialist development in Arabia.

1. Yemen (People’s Democratic Republic) —

Economic conditions 2. Yemen (People’s

Democratic Republic) Politics and government

I. Title

330.953’3505 HC 415.342

ISBN 0-86372-032-3

Acknowledgements

As anyone who has ever undertaken any research will know, such work is not done in isolation. Innumerable people have assisted me throughout the many years of this project, and it would be impossible to list all of them. Will those whom I have omitted please forgive me and still accept my gratitude for the information and insights they have given me. My colleagues at work provided a background of knowledge of the daily life of the country and its problems and I particularly want to thank the staff and students of Al Gala Secondary School in Khormaksar, the Higher College of Education in Khormaksar and Zinjibar and the Institute of Fisheries in Khormaksar. In the Ministry of Education and the University of Aden, Dr Said Abdul Khayr an Nuban, then Minister, and Dr Salem Omar Bukayr, Rector of the University, and their staff both assisted my research and dealt with the problems of my employment. Similarly my gratitude goes to my colleagues at the Yemeni Centre for Cultural Research, Archeology and Museums and in particular to its Director Abdullah Ahmad Muheirez who has supported me throughout and honoured me with his friendship.

Research for this book would have been impossible without the active cooperation and assistance of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Yemeni Socialist Party, who organised visits for me and gave me introductions to the various ministries, as well as providing fascinating discussions. In particular I want to thank the following officials: the late Mohammed Saleh Muti’ and Abd al Aziz Abdul Wali, both at one time members of the Political Bureau, who assisted me in the early years of my work. More recently, Political Bureau members Salem Saleh Mohammed, Anis Hassan Yahia and Abdul Ghani Abdul Qader provided invaluable advice, assistance and information. My thanks also go to all the staff of the Foreign Relations, Ideological, and Economic departments who assisted me at different times, particularly Farouq Ali Ahmed and Abdul Gabbar Sa’d.

In the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform I must thank the late Mohammed Awad Ba’amer, Deputy Minister Naguib Qudar and the staff of the Planning and Statistics Department; at the Ministry of Fish Wealth, the Department of Planning and Statistics, the Cooperative Department and the various corporations; the staff of the Statistics Department in the Ministry of Industry and in particular my gratitude goes to Deputy Minister Othman Abdul Gabbar whose assistance went well beyond the call of duty, and to his family whose friendship has meant a great deal to me. In the Ministry of Labour, Deputy Minister Ali bin Thabet dealt sympathetically with my questions, in the Ministry of Local Government I had interesting discussions with Deputy Minister Farouq Shamlan and with Mohammed Husayn Shamsan. At the Ministry of Planning, then Deputy Minister Abdul Qader Bagammal was helpful as well as the staff of the Economics department. In the Ministry of Health, I had stimulating meetings with Dr Ahmad Ghazy Ismail, Dr Ahmad Abdul Latif and Dr Ali Obeid Sallami. Thanks also go to Mahmoud Said Madhi, Minister of Finance and to Salem al Ashwali, Governor of the Bank of Yemen and his staff for steering me through the complexity of financial statistics.

On my visits to the countryside I have always benefited from considerable assistance and advice from the local authorities and the local Party Organisation, particularly on my many visits to Hadramaut governorate and in particular to Wadi Hadramat. I want to thank the staff of the As Salam hotel in Seiyun for running such a delightful establishment. Everywhere ordinary people showed patience and were friendly. I particularly want to pay tribute to all the peasants, fishermen, factory workers, men and women everywhere, who generously gave me of their time and assisted in a project without any benefit to themselves.

During my stay in Aden, the French community supported and encouraged me although they almost universally disagreed with my positions and aims. In particular I want to acknowledge the support of my friend the late André Fourcade who lived there between 1977 and 1979. The Sudanese community, specially Dr Farouq Ibrahim, and Mohammed Magdoub and his family gave me valuable advice and assistance. Tiger and her extended family made demands and gave me affection which structured my life there; they also improved my understanding of fish marketing and feline social organisation.

The staff of the PDRY embassy in London have always been helpful. I owe particular gratitude to Ambassador Mohammed Hadi Awad who originally arranged employment and made it possible for me to go to Democratic Yemen in 1977, and to Ambassador Saleh Husayn Muthanna and the current staff who have helped me with data which I had failed to obtain while in the country.

The development of my ideas about the country has benefited from the expertise in different fields of the following who have read all or parts of the manuscript at different stages and provided useful comments. I thank them and apologise for not always taking their advice. They are John Gittings, Fred Halliday, Bengt Kristiansson, Dorothy Lewis, Michael Maguire, Martha Mundy and Suleiman Yeslam. Dr Khaled Ibrahim Hariri read the manuscript and made many valuable comments. I am grateful for his criticism and advice on many points and for the support he has given me. David Wolton steered me through the final draft of the book, his emphasis on readability and his positive editing have added a broader perspective to this work and his encouragement and patience helped me to persist through difficult times. Since my return to London the writing of the book has been made possible by a one year fellowship from the Centre of Arab Gulf Studies of the University of Exeter. I am extremely grateful to the Centre and especially to Professor M. A. Shaban for the confidence and trust he has shown in my work, which has made completion possible, within a reasonable time span and in comfortable conditions. In London I also want to thank Hermione Harris and Mukrid for providing moral support in the lonely exercise of writing, and my mother for patiently accepting many years of absence.

Finally, and this is no mere traditional formula, I alone am responsible for all assertions, ideas, positions, interpretations, conclusions and errors to be found in this work. I am sure that no one shares all the positions expressed here but though I do not in any way claim to have all the answers, I have tried to ask many questions. Despite its failings, I hope that this book will help readers to greater and more sympathetic understanding of Democratic Yemen, its people and their recent history, and to better awareness of the difficulties of socialist development in a poor Third World country.

Helen Lackner

March 1985

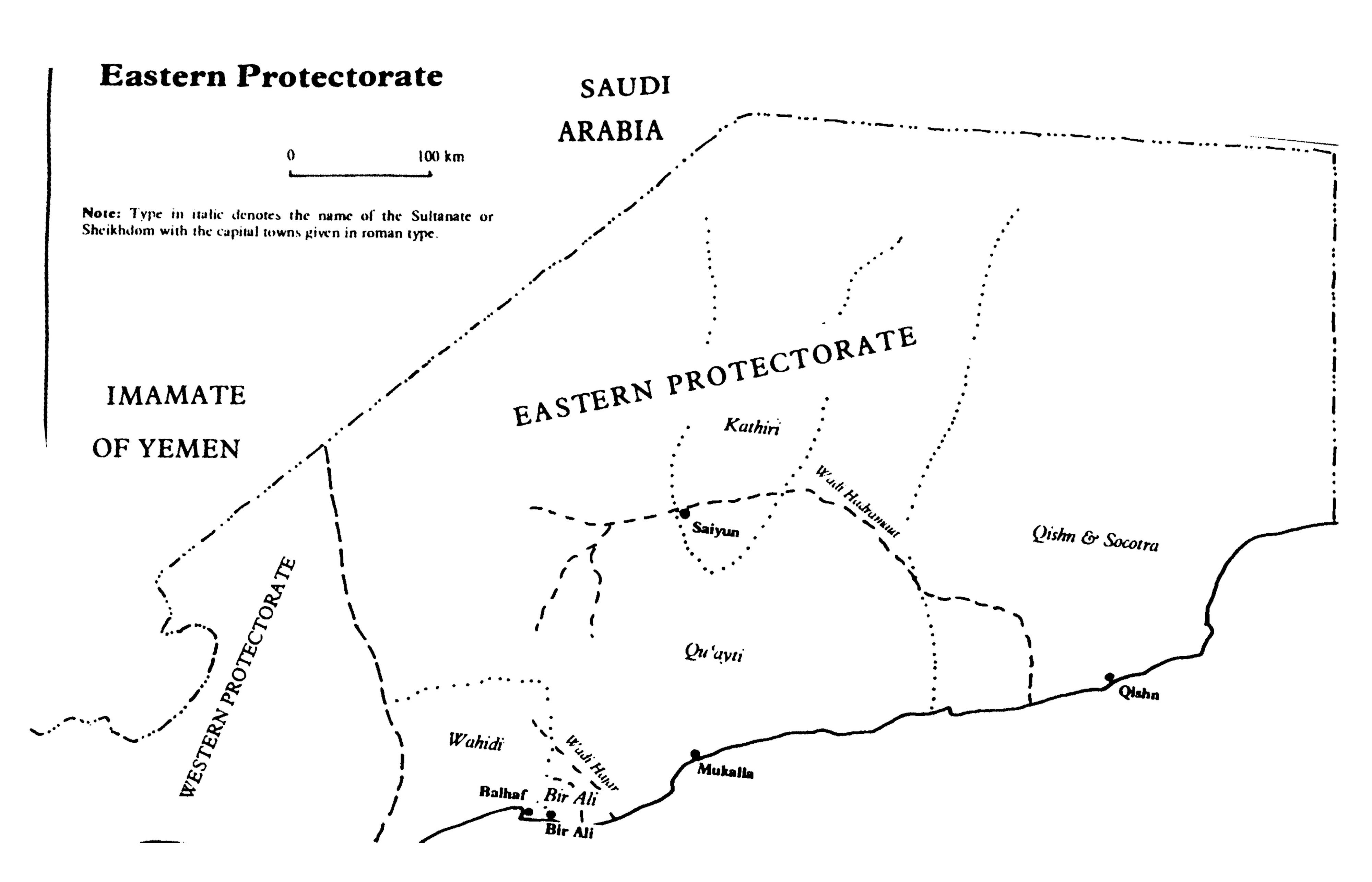

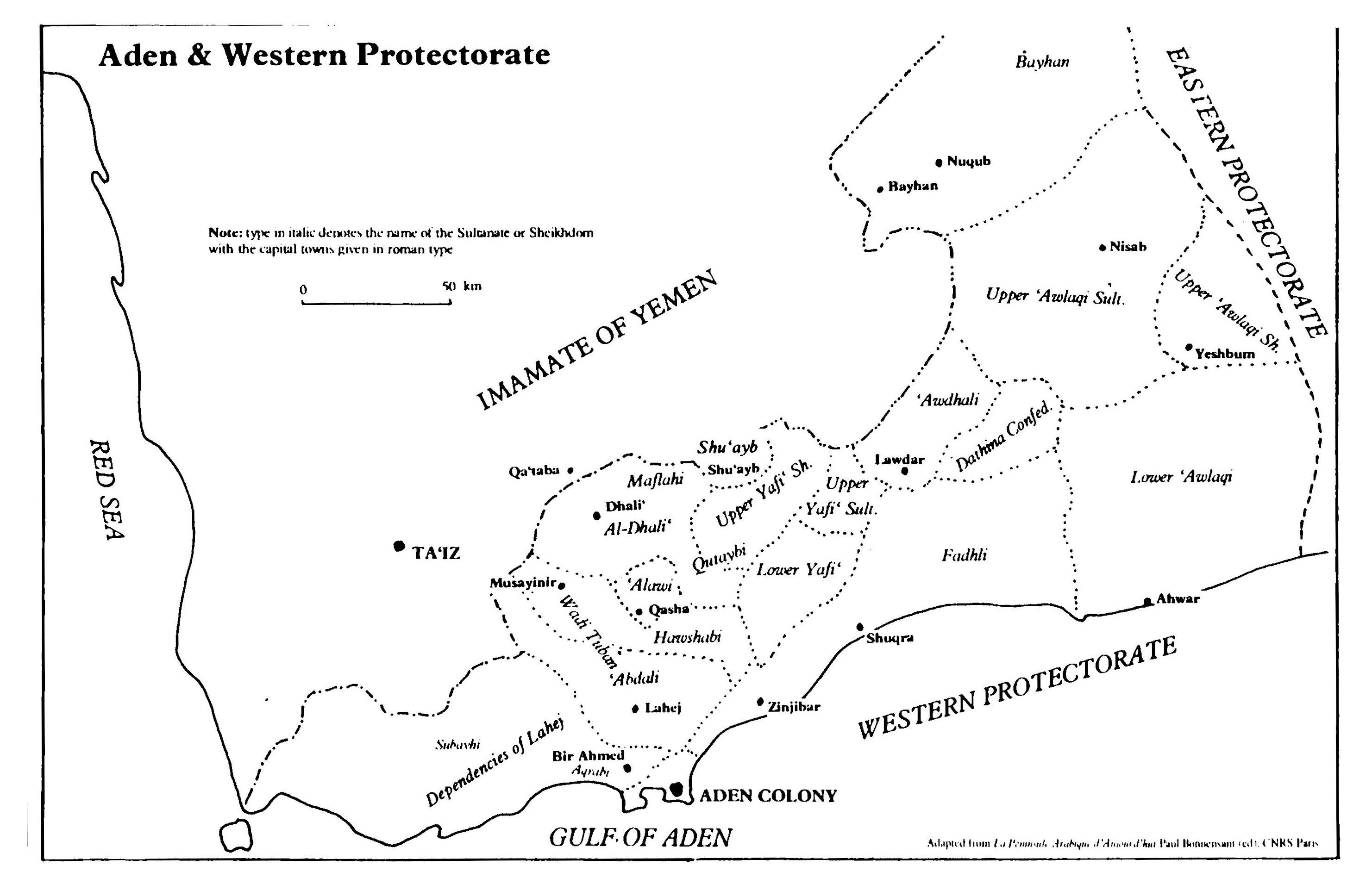

Names and transliteration

A number of points need to be made. Yemen is now a country divided into two states, the Yemen Arab Republic and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. The latter, subject of this book has, to say the least, an unwieldy name; at home the official abbreviation is Democratic Yemen which I use here by preference to South Yemen more commonly used in the West. I have tried to be consistent in this and when I talk of Yemen I mean the whole country. When talking of North Yemen I mean either the Imamate for the pre-1962 period or the Yemen Arab Republic thereafter. When discussing the PDRY I use either that term or Democratic Yemen, but occasionally South Yemen, usually when referring to other writers or when it contrasts with North Yemen. Before independence the country was in the 1960s known as the Federation of South Arabia which was composed of the Colony of Aden and the Eastern and Western Aden Protectorates. In discussing these I have used the terms amirates, sultanates, shaykhdoms and statelets almost interchangeably; when discussing the countryside in contrast to Aden, I use the terms hinterland and interior. Finally when I use southern Yemen, I refer to the PDRY and the southern part of the YAR, more or less the Shafi’i part of Yemen which shared a similar culture with the PDRY’s side of the border.

As all readers of books on the Arab world will know, transliteration from Arabic is a major problem. I make no claim to adopt academic convention on this. On the whole I have used the commonly accepted English terms for geographic names. Although there is, I hope, internal consistency in my transliteration, is does not include the more obscure diacritical signs. Many institutions in the PDRY have official English translations for their names which may at first appear strange to the reader. I have chosen to accept and to use these names even when they are not those I would have translated myself. Similarly in many quotations I have preferred to use the available ‘official’ translation, rather than provide an alternative.

Units

| 1000 fils | = | YD 1 | ||

| Yemeni Dinar (YD) | = | USS 0.345 | ||

| feddan | = | 1 acre | = | 0.405 hectare (ha) |

| ton | = | 1000 Kg | ||

| b/d | = | barrels per day |

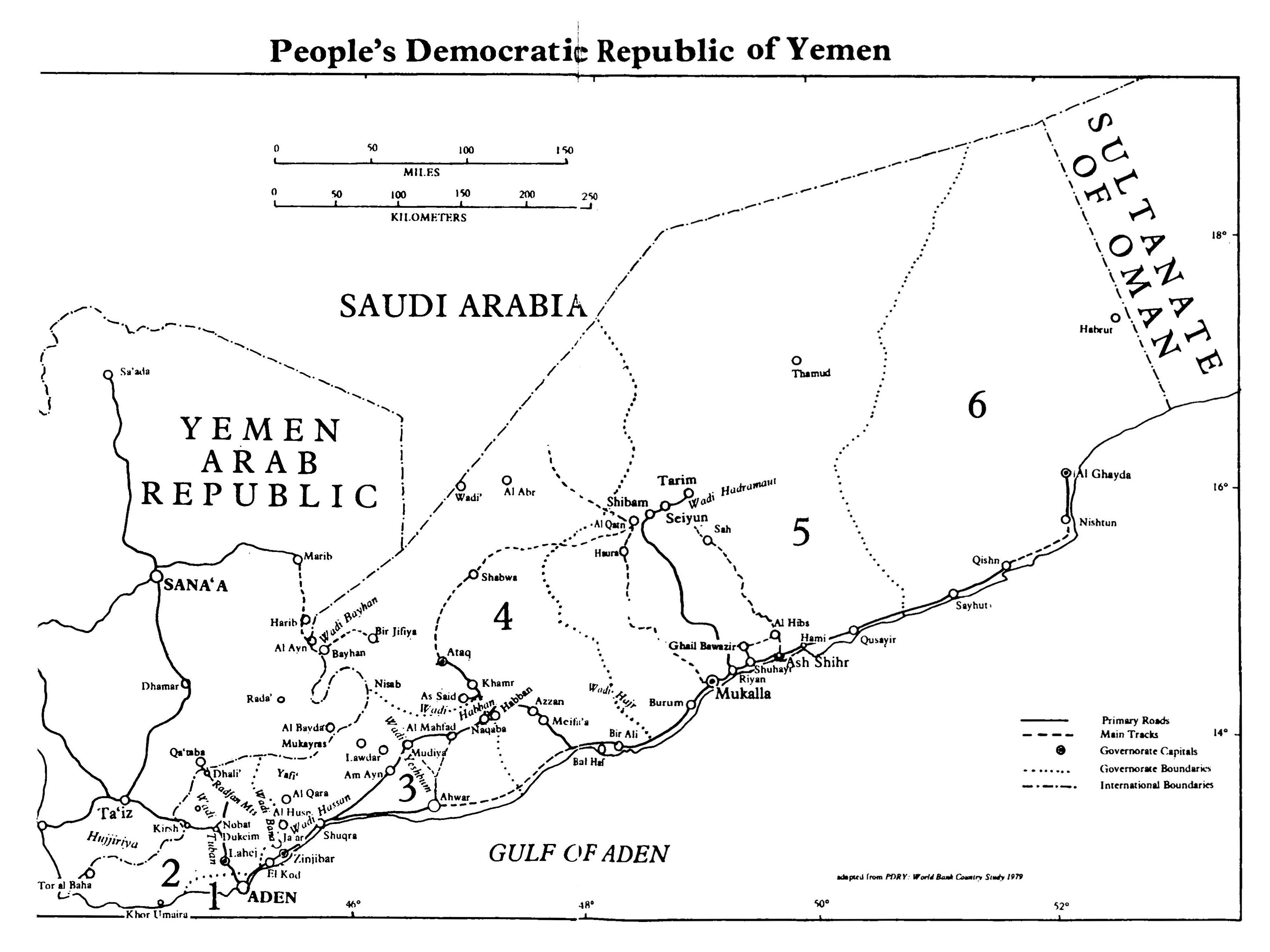

General Map of P.D.R. Yemen

Abbreviations

| ATUC: | Aden Trades Union Congress |

| BP: | British Petroleum |

| DFLP: | Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (successor to PDFLP) |

| EEC: | European Economic Community |

| FLOSY: | Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen |

| FFYP: | First Five Year Plan |

| FMC: | Fish Marketing Corporation |

| FAO: | Food and Agriculture Organisation of the U.N. |

| GCC: | Gulf Co-operation Council |

| GUYW: | General Union of Yemeni Women |

| GUYW: | General Union of Yemeni Workers |

| IDA: | International Development Association of the World Bank |

| IFAD: | International Fund for Agricultural Development |

| IMMD: | Institute of Health Manpower Development |

| IMF: | International Monetary Fund |

| KFAED: | Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development |

| LPC: | Local People’s Councils |

| MAN: | Movement of Arab Nationalists |

| MAAR: | Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform |

| MCH: | Mother and Child Health |

| MRS: | Machinery Rental Station |

| NDF: | National Democratic Front |

| NFPO: | National Front Political Organization |

| NLF: | National Liberation Front |

| OLOS: | Organization for the Liberation of the Occupied South |

| OPEC: | Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries |

| PCAS: | Public Corporation for Agricultural Services |

| PCMFV: | Public Corporation for the Marketing of Fruits and Vegetables |

| PDC: | People’s Defence Committees |

| PDFLP: | Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine |

| PDU: | People’s Democratic Union |

| PFLO: | People’s Front for the Liberation of Oman |

| PFLOAG: | People’s Front for the Liberation of Oman and the Arabian Gulf |

| PFLP: | People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine |

| PHC: | Primary Health Care |

| PLO: | Palestine Liberation Organization |

| PRSY: | People’s Republic of South Yemen |

| PSP: | People’s Socialist Party |

| SAL: | South Arabian League |

| SFYP: | Second Five Year Plan |

| SPC: | Supreme People’s Council |

| UAR: | United Arab Republic |

| UNESCO: | UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation |

| UNICEF: | UN Children’s Fund |

| UNF: | United National Front |

| UPONF: | Unified Political Organization, the National Front |

| WHO: | World Health Organisation |

| YAR: | Yemen Arab Republic |

| YSP: | Yemeni Socialist Party |

Introduction

The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen is the only country in the Arab world where a socialist group fighting for the overthrow of the old order actually achieved power. When evaluating any aspect of Democratic Yemen’s development since 1967 it is essential to bear in mind the internal and external circumstances which form the background to the regime’s policies. First internal conditions. The movement which gained control at independence has been trying to ‘build socialism’ in the 1970s in a country with a population of only 2 million distributed over a large geographic area, with an average population density of less than 5.1 per square kilometre, and a rural density of 4 per square kilometre, making the per capita cost of all services and infrastructure particularly high.[1] The poverty of the land is absolute: there are no significant natural resources. Cultivable land represents 0.3% of the country’s surface. There are no commercial quantities of minerals: the significance of the 1982 oil strike remains unclear at the time of writing, but whatever it may turn out to be, it is not relevant to the 1980s. It may turn out to make self-financed development possible and also solve the growing debt-repayment problem, but this is as yet mere speculation. The country’s fishing waters were at first seen as the panacea, and as a result they were overexploited in the 1970s and in future can only reasonably be expected to improve the national diet and play a minor role in the acquisition of foreign exchange through exports. Unlike many other very poor countries, Democratic Yemen does not even have a large reserve of labour: emigration has for centuries, but particularly in recent decades, removed labour which might otherwise have been available for local development.

While in the 1950s and 1960s Aden, but not the hinterland, lived in prosperity, the total absence of resources was revealed at independence with the simultaneous collapse of the port following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and the destruction of the economy of Aden dependent on the military base. The country was left with only its traditional hinterland subsistence agriculture and fisheries. The emigration of the professional and commercial middle classes with their capital aggravated the situation. Furthermore the hostility which the new state encountered almost everywhere meant that it had great difficulty in raising finance for development projects which the population expected from independence. On the contrary, the immediate effect of the departure of the British and the closure of the Suez Canal was a drop in living standards in Aden with no significant improvement in the hinterland. These were the materials on which a new state and society were to be built..

The international context is relevant at the broad political level in explaining the background against which the NLF developed, while the regional context has had direct political, economic and ideological impact. There is no doubt that Democratic Yemen was born in a particularly hostile world. For the Third World the 1970s brought increased poverty and deprivation for the majority of the people; in most countries raw or semi-processed materials were exported at falling prices in real terms while those of imports rose. This situation benefited both the transnational companies of the capitalist countries and the small national bourgeoisies which rule most Third World countries. Increased exploitation of Third World resources was one way to alleviate the effects of the recession in the capitalist world which began in the early 1970s. Deteriorating terms of trade are one aspect of the impoverishment of Third World countries. Another became clear in the 1980s. While in the 1970s governments were encouraged to borrow vast amounts and interest rates relatively low, these rose to exorbitant levels by the 1980s, thus crippling the economies of many Third World countries who found themselves making net transfers to the capitalist countries in the shape of debt service payments. A third, lesser but still significant, factor is labour migration in particular that of professionals, giving another example of free aid from the Third World to the capitalist countries, as skills acquired at the expense of their home country go to the benefit of the labour importing country.

The Arabian Peninsula has been an exception to the general trend of increased poverty in the Third World in the 1970s. The oil price rises in 1973 created an unprecedented boom in the economies of the oil-producing Peninsula states who all had small and little qualified native populations. Their sudden rise to the top of the per capita income league allowed them to make ambitious development plans which necessitated the import of labour, while those who could afford it adopted the lifestyles of the international idle rich. These developments in the Peninsula took place after the 1967 defeat of the Arabs in their war against Israel, which also had a major impact on people’s thinking throughout the Arab world. Blame for the defeat was placed by the left as well as by the right on the so-called socialism of Nasser, which became discredited for both sides. All these factors were crucial to the development of Democratic Yemen, making the context even more unfavourable than it would have been merely through the circumstances prevailing internally.

The boom in the Peninsula affected Democratic Yemen in a number of ways. Emigration has had a profound influence economically, culturally and even politically. By the 1970s Saudi Arabia and the Peninsula mini-states had been receiving Yemeni immigrant workers for decades: they started working in the oil industry in the 1950s and were also found in the armed forces of the then Trucial States. By the 1970s the Peninsula had become a far better option for Yemeni migrant workers than further afield where they had earlier emigrated: Indonesia and India in the 19th Century, Britain and the USA in the earlier part of the 20th. As recession hit the heavy industries where they worked in these countries, the oil-export induced boom of the Peninsula provided alternative employment. While in the early days of oil extraction Yemenis had been working in an environment which was not substantially different from home and where the standard of living was comparable, the situation changed in the 1970s as oil prices rose and per capita income for nationals of the Peninsula states rocketed. The earnings of Yemeni migrant workers rose dramatically with a number of consequences. Positively their higher level of remittances provided the government in Aden with some of the foreign exchange desperately needed to finance development projects. Emigrants were also able to improve significantly the standard of living of their families who lived mainly in the remote rural areas and who therefore suffered less from the urban-rural gap than they would have otherwise.

Emigration also has a considerable impact as a result of the gap in income between home and abroad: the high rates of pay prevailing in the Peninsula states meant that relatives at home do not find it necessary to work at the low public sector salaries and many prefer to remain idle. It is also difficult for the public sector to retain staff and to obtain hard work from them as they find little incentive from their salaries. A secondary but related effect was some neglect of traditional agriculture and fisheries whose returns in the 1970s could not compete with those of emigration. Emigrants and their families continued to use the developing social services while their productive life was spent abroad.

The negative effects of the boom in the Gulf are very important. They are noticeable mainly indirectly in their ideological influence. Similarities of culture and language resulted in a disproportionate increase in expectations which was totally unrealistic given objective conditions in PDRY. As the standard of living of emigrant workers and their families rose, the expectations of their neighbours rose also. Being aware of what was available in the Gulf states in the 1970s, Yemenis expected independence to provide the same at home particularly as in the 1960s Aden had been the most modern city in the Peninsula, quoted as an example throughout the region. Its decline in the 1970s, taking place while ultra-modem cities were rising out of the desert at meteoric speed elsewhere, was explained in political rather than economic terms. In this respect the propaganda war waged against the régime in Aden was successful. Yemenis came to blame the poverty of their country on socialism rather than on the objective differences in financial circumstances which separated Democratic Yemen and the Gulf states. This propaganda success was made easier by two factors: the excesses of the régime in the early 1970s and the fact that many of the régime’s social policies challenged traditionalist beliefs.

Those Yemenis who blamed socialism for the difficulties of Democratic Yemen in the 1970s ignored the most important difference between their country and the Gulf states they wanted to emulate: while in the latter all forms of development and unproductive expenditure could be financed from revenue derived from oil exports, in Yemen no such possibility existed. Another deceptive feature of the 1970s was the apparent boom in the Yemen Arab Republic where cash incomes were high and where foreign aid was pouring in. Looking at these facts alone ignores that many had little access to cash and that the cost of living was incomparably higher than in Democratic Yemen, thus cancelling the advantage: while a minor government employee in Aden could live modestly and support his family on his official salary, his equivalent in Sana’a would earn ten times as much in cash but this would barely pay his rent, let alone food or other necessities. Further he had no guarantee that his salary would be paid regularly as this depended mostly on foreign subsidies which were often cancelled when the régime in Sana’a took an independent political line. Foreign aid programmes, whose long term benefit is open to question, were also clearly initiated for political reasons in Sana’a.

While comparison with the Peninsula oil-exporting states is understandable due to their proximity and because most Yemeni workers emigrate there, comparison with other Third World states with similar income is far more appropriate. There is no doubt that living conditions for ordinary people in Democratic Yemen are better than those prevailing in countries whose per capita GNP is similar, for example Sudan, Mauritania, Liberia and Senegal. In most poor Third World countries there are vast differentials in incomes between the numerically small bourgeoisie and the mass of the people at or below bare survival level. Corruption is everywhere the norm and efforts to improve poor people’s standards of living are symbolic or nonexistent. Unfortunately many Yemenis ignore this and forget that in a decade which has seen a serious fall in standards of living of the poor throughout most of the Third World, in their own country social services have been created, the gap between the privileged and the masses remains negligible in comparison with elsewhere, and corruption is effectively nonexistent. In brief, while standards of living elsewhere have deteriorated, in Democratic Yemen they have improved and at the same time the bases for future development have been laid. An ordinary unprivileged person in the PDRY has a better life than would be available in other Third World countries of whatever ideology, despite the country’s almost total lack of resources, largely thanks to emigrants’ remittances.

In the late 1970s a public sector worker, be he in a factory in Aden, a state farm in the countryside, or a fisheries cooperative on the coast could expect a basic income of YD 50 per month, which might be supplemented by overtime of another YD 20 or more. If his wife was also working for cash, but in a less responsible position, her income might be YD 35–40. Out of this they would expect to pay YD 5 on rent, another YD 15 for electricity and water if connected to the national supply, and would need another YD 50–60 to feed a family of 5 a fully nutritious diet. This is not wealth, but it is a long way from not knowing where the next meal comes from. Food, although expensive, has been heavily subsidised by the régime since independence, as are other basic necessities, as must be obvious from these figures. Education and health services are available to these families, though for many access may be difficult due to remoteness. These achievements are not to be belittled and have taken place in a particularly unfavourable environment.

This book is an attempt to understand what led the struggle for liberation to take the shape it did, what political influences directed the NLF towards a socialist ideology and how the regime has chosen and implemented policies in the state’s first 17 years, as well as the problems it has faced and those it ignores.

Some will argue that political developments in Democratic Yemen cannot be discussed in isolation from parallel developments in the Yemen Arab Republic in the past twenty years, and there is no doubt that the two parts of Yemen are intimately connected at all levels. Despite this argument I have only dealt with events and developments in the Y AR insofar as they narrowly and directly affected Democratic Yemen. A full comparative study would have demanded more research and time than I had. I also believe that the current division of the country into two states creates a reality which must be dealt with as such. While many Yemenis in the west of Democratic Yemen feel a deep and urgent attachment to a united Yemen, there are others, in Hadramaut and Mahra, for whom this is hardly a concern.

Because my primary concern is with internal developments and in particular how they affect the population I have dealt with international relations only briefly, concentrating instead on the political changes which have laid the basis for a tranformation of the social structure and the creation of a new society.

Chapter One: The Colonial Period

The British occupied Aden in 1839 as a useful staging post on the route to India, a coaling station, and a supply depot where fresh food and water could be acquired for the onward journey. Its main assets were the excellent natural harbour and later on its position at a point where steamers needed a fresh load of coal. Otherwise Aden presented no intrinsic interest to the British for it had no hinterland for trade, no wealth which could be extracted either as raw materials or as manufactures, nor had it any significant agricultural potential. Even its strategic value which was later asserted by some to be so valuable was questionable.

By 1839 the town of Aden had dwindled from its best days as an international port in the 16th century to become an impoverished fishing village of about 600 inhabitants. Thanks to its major advantage as a natural harbour, Aden had played a significant role whenever there was international activity in the region. Its decline was partly due to the loss of Portuguese ascendency when the Ottoman Turks finally gained the upper hand in southern Arabia. The latter chose Mokha as their main port, which was closer to the areas where they had greatest control and to coffee, the only export crop. Coffee was shipped north up the Red Sea, again giving Mokha the advantage, and Aden could not compete as it had to bear the costs of the longer overland routes and the greater number of tribal groups which had to be paid off on the way. Turkish control over areas very distant from the centre of power and of little strategic interest was always loose and Aden was not a priority in Ottoman strategy. Ottoman control over Yemen relaxed with the decline in the coffee trade in the early 18th Century when competition from other coffee growing areas became significant, and this led to greater autonomy for the tribes. It was as early as 1730 that Aden regained its independence under the ‘Abdali sultan of Lahej supported by the tribes of Yafi’.

That Aden’s new independence did not lead to a revival of the port was due to the poverty of the areas controlled by both the ‘Abdali and the Yafi’i. Aden was able to export Yafi’i coffee to the east and to trade with Somalia where Berbera was a major international marketplace. International interest in the region remained low and Aden continued to decline, the city falling into ruins. Much of it was abandoned, though the ‘Abdali made some efforts to revive it and even attempted to interest Britain in the port, long before the British were willing to take any stake in it.

Since the decline of the incense empires of Southern Arabia in the 5/6th Centuries AD, the hinterland had been reduced to bare subsistence. Most lived off coastal fishing and subsistence agriculture in the few areas where there was sufficient water, while the nomadic tribes survived by seasonal grazing and the imposition of heavy customs duties on the few remaining trade caravans and other travellers, and from raiding the travel routes. The area was of no interest to outsiders who ignored disputes between local rulers over the domination of impoverished communities. All the communities in the region were already familiar with emigration which was recorded in antiquity as already being the only means of improving the standard of living of the migrants’ families. The small mountain tribes on the highlands close to what later became the Y AR also survived by imposing customs duties on trade, and from taxing the craftsmen and sharecropper peasants. None of these régimes was very stable: power would shift from one part of a family to another within the same tribe, from family to family, from tribe to tribe, and tribes which lost out soon found themselves becoming subject to stronger neighbours. Thus the politics of the region were in constant flux according to the vagaries of trade, raiding, or the natural disasters of drought and flood.

In the eastern part of what was to become the PDRY, there were many important nomadic tribes who also controlled trade routes and limited the authority of the sultans who were the nominal leaders of the sedentary people. Whereas in the west settled agriculture, herding and ‘trading’ nomadic life were closely interwoven, and nowhere was there a significantly large and exclusively sedentary culture, in the east the situation was very different. That area is a large barren plateau and desert with a few large pockets of watered lands, mainly the Wadi Hadramaut; and on the coast the regions around Ghayl Bawazir and Maifa’a, as well as a few smaller ones east of Wadi Masila in the Mahra area. This brought about a clear division between on the one hand sedentary rural and urban populations and on the other nomads who herded animals, transported goods and levied duties on travellers and goods. The settled people were mostly in Wadi Hadramaut, where in the 16th and 17th Centuries the Kathiri sultans had a fair degree of control over the Wadi and its population and resources. In addition the main ports on the coast, Shihr and Mukalla, had their own rulers who claimed to control the trade routes between the coast and the Wadi as well as, at times, the coastal towns and their neighbouring agricultural pockets. Between 1650 and 1680 the Ottoman Turks sought to control the area, but after only 30 years of occupation the Kathiri reasserted their independence, shortly before falling into decline themselves in the 1720s. They were obliged to compromise with the nomadic confederations and to share power with the major tribes, the Humum, the ‘Awamir and the Ahl Tamim, while trying to retain control of the towns, though even there they had to share power with the religious notables, the sada (see below), and in some cases Yafi’i immigrants. The wealth of Hadramaut was sent back by emigrants and although the surplus which could be extracted from the settled peasantry there was higher than elsewhere, tribal strife made it difficult for any single authority to accumulate significant wealth. Migration was a major feature of life throughout known history in all classes of society: it was the sada who tended to travel east[2] to become traders and merchants in Indonesia, while peasants were more likely to emigrate to East Africa and other Arab areas. Even nomads worked abroad in low status occupations when no other source of income was available.

By the early 19th Century two factions of the immigrant Yafi’i were in control of the Hadrami coast, in rivalry with each other: the Ahl Barayk held Shihr while the Kasadi held Mukalla. In Wadi Hadramaut power was disputed between two families whose strength originated in their role as law enforcement officers for the Nizam of Hyderabad in India. These were the Kathiri, longstanding rulers in Wadi Hadramaut, and a new family of Yafi’i immigrants, the Qu’ayti.

The Rationale of British occupation

As was often the case in like situations, there were in Britain factions supporting the occupation of Aden and others opposing it.[3] Aden was not in any case under direct control from London, but from India, where the central authority was in Delhi but immediate orders concerning Aden came from Bombay. Thanks to the slowness of communications in the early 19th Century (a reliable telegraph service was only introduced in the 1870s) all sorts of contradictory policies could be pursued simultaneously over long periods; action could also be taken without due authority, giving individual officials the possibility of going their own way.

In the 18th and early 19th Centuries Britain ignored the Red Sea and the northern part of the Indian Ocean as these areas did not control access to India. The French invasion of Egypt in 1798 was a shock which changed this perception and thereafter they no longer allowed local shipping or the French open access to the area. The threat to British interests presented by the French occupation of Egypt was very clear both in London and India and steps were soon taken to counter it and re-establish British dominance in the Red and Arabian Sea areas. In the late 18th Century when Mokha was more significant as a port than Aden, British ships had tried to gain access there to obtain supplies for the island of Perim which they had occupied to forestall the French. They were not welcome in Mokha and were encouraged by the invitation of the Sultan of Lahej to come to Aden, so the troops went there and remained until early 1800 before returning to India.

Local shipping organized by the sea-faring tribes of the Peninsula had developed and their trade reached further afield than ever. Their actions against European ships, described by the British as ‘piracy’ also affected maritime trade, and their increasing commercial influence and significance made them a threat. To reassert their dominance, the British started charting the waters of the Red Sea in the early years of the 19th Century; they also again bought coffee at Mokha and encouraged merchants to use British ships in the region, relying on their presence to counteract other influences. As steamships took over, the distances that could be covered between supply stops increased, and created the need for coaling stations. In 1829 the British tried Mukalla as a coaling station, after considering Perim, Socotra and Aden.

In the 1830s Muhammad Ali, the Khedive of Egypt, invaded the Peninsula adding a new threat to the earlier expansion of Wahhabism in the region and gave the British the opportunity of stating and confirming their interest in Aden. In 1837–8 the British negotiated with Sultan Muhsin Fadi al ‘Abdali, ruler of Aden and Lahej, who thought that the British would offer a better deal than the threatened Egyptian occupation. Negotiations were conducted on the British side by Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines whose aim was occupation. Muhsin wanted a protection treaty in exchange for giving the British authority to build a factory and a garrison, but he did not wish to give up sovereignty, directly conflicting with Haines whose ambition and life work was to bring Aden under the British flag.

While Muhsin and Haines attempted to make a deal, various justifications were developed in different sections of the British establishment. Everybody agreed on the need to secure a coal depot for the steamships, which included both mailships and military craft. However it was justifiably argued that a coaling depot could be obtained without the expense and responsibility of military occupation, by reaching agreement with the ‘Abdali Sultan of Lahej and Aden, as was desired by Sultan Muhsin. That military and coaling were separate concerns was later demonstrated by the planning of Aden’s defences which left the coal depot outside the defence perimeter. The argument between those for and against involvement continued for decades: different factions were at various times located in London, Delhi and Bombay. The interventionists were spearheaded on the ground by Haines whose early attachment to Aden began when he took part in the charting of the Red Sea. To him Aden represented a major goal and his occupation was supported by Sir Robert Grant, the Governor of Bombay. In London, the main argument for gaining sovereignty of Aden was strategic. However authorization for a military takeover was not forthcoming and Haines was instructed to negotiate even after the capture and looting of a British ship. However thanks to poor communications Haines took the initiative and landed troops, forcing the ‘Abdali Sultan to abandon Aden in January 1839. Reluctantly Haines’s superiors accepted the fait accompli.

After its occupation, Aden did not change dramatically. In the first years the neighbouring Sultanates of ‘Abdali and Fadli made various attempts to recapture the town, despite some form of agreement between the British and the ‘Abdali who were paid regularly for the use of the town by Britain. Haines’s ambition to restore Aden to its legendary prosperity as a major trading centre was not achieved during his tenure, when it was little more than a military garrison.[4] In the 1840s Haines tried to undermine Mokha as a trading centre by negotiating with the leaders of the Hujjiriyah and the Imam’s representatives, to persuade them to transfer the coffee trade to Aden, but it came to nothing. Aden’s role as a port remained limited, playing a supporting role for the Berbera trade fair which took place from October to March, but which it failed to replace.

Haines’s autocracy was such that he alienated most of the British military commanders during his period as governor; in his relations with the interior he played the tribal rivalry games according to much the same rules as the Yemeni leaders. The fact that he remained governor, when normally such a post would have been given to a more senior person, indicates what little importance was attached to Aden by the authorities in India and London. Although Haines’s treatment of leaders in the hinterland showed some understanding of the dynamics of intertribal relations, to the tribal leaders he, and therefore Britain which he represented, appeared to be just another participant in local power games. They failed to identify the fundamental difference between British intervention and earlier invasions, such as the Ottoman and Portuguese. This difference was one of historical period, rather than of nationality and Britain’s impact was unprecedented as it represented industrial capitalism, a mode of production far more threatening to pre-capitalist formations than the mercantile capitalism of Portugal for example. Britain both challenged the traditional leaders as independent rulers and the social and economic structures which they had dominated and fought over.

In the 1840s and 1850s, having failed to repel the British by direct assault, the rulers of ‘Abdali (Lahej) and Fadli (Shuqra), ‘Aqrabi, Hawshabi and others combined in an attempt to cut off Aden’s supplies of water, firewood and food. This failed as merchants increasingly succumbed to the temptation of selling to the British to gain commercial advantage over their competitors. Attempts by the ‘Abdali to regulate and control trade with Aden by imposing fixed customs duties also failed. The ever greater solidity of the British presence in Aden seriously undermined the authority of the tribal rulers, while the British learned that they could manipulate and manoeuvre the rulers who were unable to unite to face a threat of whose real importance they had no conception. While the blockade and embargo continued there were incidents of petty harassment of the British, including the murder of some Europeans who had ventured beyond the limits of British Aden. These murders were indiscriminate and were implicity supported by all the local rulers who repeatedly failed to catch and punish the perpetrators, claiming that they had escaped to another territory.

Neither delegating power nor informing others of his plans and activities, Haines did not lay the foundations for a competent administration. He was constantly in conflict with other British, particularly the military authorities, and his relations with the hinterland rulers were hardly better, though he approached them as equals. He dominated Aden until his departure in 1854, when he was recalled to Bombay on charges of malpractice relating to his inability to account for substantial expenditure. With his departure efforts were made to bring Aden’s administration into line with that of other British dependencies, and the improvement of communications soon made it possible for policy to be more strictly controlled from Bombay, and eventually from London.

Southern Yemen from the 1850s to the First World War

In the second half of the Century, the strategic importance of the new shipping routes increased the military emphasis placed upon Aden by the British, reversing the policy of the early years when they would have liked to see more commerce and less garrison. An official policy of ‘Fortress Aden’ was developed and priority was given to Aden’s defences and their strengthening against attack from both sea and land. Aden soon came to be seen as the gateway to the Suez Canal and its first line of defence against enemy attack. Once again voices were raised to suggest that Aden was of no intrinsic military value and that protection of the route to India lay elsewhere. These voices did not prevent the authorities from strengthening the town’s sea defences to the west of the rock particularly in Tawahi, or Steamer Point as the British later called it. This area therefore developed rapidly, thanks to the dredging of the port and other modern facilities created around ‘Back Bay’ as it was at first known. Development of Back Bay took place at the expense of Front Bay, in Crater, which was soon abandoned as being too shallow, but the main commercial and productive activities remained in the old Aden town, in the crater. To turn Aden primarily into a military outpost implied increasing control and restriction of the civilian population which the army called for, without much success.

The Suez Canal opened in 1869 changing the course of Aden’s history by ensuring its transformation into a merchant city, well placed at the crossing of a number of international trade routes, and it rapidly replaced Berbera as the regional international trade centre. In 1891 with the arrival of faster steamships, work began on dredging the port giving further impetus to the city’s expansion which had started in the 1880s with the purchase of land north of the isthmus from the Sultan of Lahej. This land was used to build Shaykh Othman, initially meant to be a dormitory town for the commercial parts of Aden. It was too far away for this and although it developed autonomously, did not take this role till a century later. In the late 19th Century Tawahi and Crater remained the places where people lived and worked and their overcrowding increased. Merchants of different nationalities dealing in a variety of commodities settled in Aden establishing it as a major trading centre both for the region and further afield; trade was dominated by cotton goods, coal, grain, coffee and increasingly hides and skins.

The population increased by immigration from abroad, including Indians who worked in the administration and various others involved in the higher levels of trade, but mainly by the arrival of unskilled people from the interior and Somalia who came out of season to work as labourers and who returned home for harvest and planting. Labour was brought to Aden by contractors known as muqaddam from each emigrant area or village. They brought in men from home and then acted as brokers, mediating between the employer and the workers; supposedly responsible for the welfare of the workers they collected their wages, fed and housed them, retaining a heavy percentage on the way and ensuring rapid enrichment for themselves. This system remained in force throughout the period of British occupation. As the town developed, rudiments of social services were introduced with the opening of the first school in 1856. Teaching was in English and exclusively aimed at the higher classes of Indian and other immigrants, although by 1890 almost half the population was Yemeni and included people from the British-dominated areas as well as from regions which subsequently became part of the YAR such as the Hujjiriyah, al Baydah, Qa’taba etc.

The development of Aden did not, however, have a significant direct effect on the interior, as most trading was of import-export variety. The interior expanded its traditional role as a supplier of water and of animal fodder which, as the demand increased, was produced further into Fadli and later in Yafi’ territory. The only other side-effect was that increased quantities of grain, vegetables and supplies were imported from further afield,, Lahej, Abyan and Dhali’. Despite its increased exports of food to Aden, the interior suffered from very dramatic and natural disasters of drought, flooding and animal disease. In the 1860s there was famine throughout the area, and although British views of relations with the hinterland changed in the same period towards a more interventionist approach to promote economic and social ‘progress’, no effort was made to alleviate the immediate conditions of famine or to develop the hinterland.

Politically, by contrast, there was considerable development. This was prompted on the one hand by Turkish Ottoman advances from northern Yemen towards areas controlled by rulers who had relations with the British in Aden. Between 1870 and 1872 the Turks tried to obtain the subordination of Lahej, where they failed due to the ruler’s faith in the British. With the Subayhi they succeeded as the ruler hoped to gain greater benefits. Earlier, in 1867 in the course of a struggle for power between two factions in Hadramaut, one side had appealed to the Turks who officially claimed control over the area and sent warships to Shihr and Mukalla, to the considerable irritation of the British. In those days British policy was to reach agreement with the Ottomans who were considered to be allies in other parts of the Middle East particularly against the Russians. Consequently negotiations took place in Istanbul rather than on the spot, in this case resulting in the withdrawal of the warships and the shelving of the issue. The Turks were clearly pursuing an active policy in the region and claimed sovereignty over most of the hinterland though they did not attempt to enforce it, except when local rulers willingly submitted to them.

Britain was encouraged to be more interventionist in the interior as in Europe colonialism became the dominant mode and the trend shifted away from a mercantile concern to hold ports and strategic positions, towards occupation and full control over lands and peoples. This became clear in the Berlin Congress of 1885, when Africa was ‘carved up’ between the different European colonial nations. The context of the Congress was an international race to leave no area of the world unassigned. In the face of both international competition and direct Ottoman claims over the area, Britain found it expedient to take a more active interest in the political affairs of the hinterland. The first move was in 1873 when Britain insisted that the Ottomans respect the ‘independence’ of nine tribes: the ‘Abdali, Fadli, ‘Awlaqi, Yafi’, Hawshabi, Amiri, ‘Alawi, ‘Aqrabi and Subayhi.[5] It was also in 1873 that the first plan for the establishment of a Protectorate over the area was drawn up; it was ignored by the authorities in India and in London, and the draft was shunted around for the following 15 years from desk to desk, but the idea survived this treatment and eventually protectorate treaties were signed.[6] In 1886 the Government of India started a protectorates scheme with the signature of the first Treaty with the sultan of Qishn and Socotra. Areas closer to Aden were left till later, largely because of fears of protests by the Turks. These proved groundless when in 1888 the Resident in Aden went on a treaty-signing tour of states along the coast and the following year this policy was applied to inland states. Further treaties were signed in 1903 and 1904, and these continued to be revised and agreed throughout the period of British occupation. Their significance was greater in the long-term than in the short, as they officially designated who could and who could not have direct relations with Britain and consequently who did and who did not have access to weapons and other gifts. We shall return to this later when discussing the dynamics of tribal-British relations.

The treaties however did not put an end to Turkish intervention, and competition with the Ottomans continued till their final defeat in the First World War. Various commissions were set up to determine the borders between British and Turkish dominated areas, and these debates culminated in the nomination of boundary commissions, and an agreement reached in 1905. During the First World War, the Ottomans advanced as far as the suburbs of Aden in 1915, and were repelled to Dar Sa’ad where they remained for the duration. When they were finally defeated and withdrew, Imam Yahia Hamid al Din of Sana’a took over and declared Yemen to be an independent state; in 1919 he also occupied much of Aden’s hinterland which had previously been under British protection and refused to withdraw. Yahia believed that he could retain control over these areas. He had not lost any of them by negotiations with Britain and after 1926 his relations with Italy gave him further confidence. But in 1934 he felt seriously threatened by King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia whose troops were advancing into Asir in the northwest of his country, and Imam Yahia found it expedient to reach agreement with Britain by withdrawing over the border and a Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Cooperation was signed in February 1934.[7] This was to be the basis of all future border discussions and disagreements between Britain and North Yemen which it failed to solve definitively due to the different understanding of the word ‘border’ in English and Arabic, the former treating it as a line and the latter as an area. It was however agreed that temporarily all forces should withdraw to their earlier positions and Britain recovered its protectorates, which thereafter suffered no more than various incursions and threats, but were not reoccupied by the Imam’s troops or administrators.

The Ottomans and the Imams had little part to play in what became the Eastern

Protectorate; after the withdrawal of the Turkish ships in 1867 and despite various appeals to them by the Naqib of Mukalla and the Kathiri of Seiyun at various times, their intervention on the ground was at an end.

The transformation of the hinterland

Although the influence of the British in penetrating and transforming the dynamics of southern Yemeni society was paramount, other factors played a significant role, in particular those which were products of the growth in industry world wide which rendered obsolete many of the features of Yemeni economic and political relations. One was the introduction of accurate rifles to replace the traditional matchlock, another was the arrival of motor transport to replace the camel. Both had an influence comparable to that of British intervention, and the three factors combined fundamentally to undermine traditional tribal structures and intertribal relations.

The new types of weapons were the Le Gras, Remington and Martini-Henri rifles which made it possible to conduct blood feuds at a distance of hundreds of metres rather than face-to-face and resulted in dramatically increased bloodshed. Starting in the 1880s, these weapons rapidly replaced the older types throughout Yemen and by 1902 had reached as far as Wadi Hadramaut and soon after even Marib. They were imported illegally through all the accessible ports on the Red Sea coast and although there are no definite estimates of the total number imported in the last 20 years of the 19th Century, it is clear that most men acquired them, even members of classes which were not traditionally arms bearing. ‘During the thirtyyear period from 1880 to 1910 the traditional tribesman with his dagger at his belt and a slow match for his matchlock bound round his turban was replaced by the now familiar figure of the Arab with his faithful rifle slung across his shoulder.’[8] Groups of ordinary tribesmen were thus encouraged to challenge the rule of their traditional leaders and to use their weapons to collect tolls independently on established trade routes, giving no more than nominal allegiance to their former leaders. This contributed to a further fragmentation of society into smaller and smaller tribal segments and it was often in such a period of flux that the British would arrive to sign a protectorate treaty and reach agreement with the ‘Chief of the tribe.

At the best of times tribal leadership was fluid, and could shift from one branch of a family to another according to their relative power and influence and the personal qualities of the individual contenders. Relations between tribes varied according to the balance of diverse factors: control over economic resources such as agriculture and Ashing, the strength of the group in armed men, the control of trade routes for the imposition of customs duties or the organization of caravans, the profits of cattle raiding, the level of local and international trade from which levies could be collected, harvests, droughts, floods and other ‘natural’ cycles. When the British arrived in search of signatories to treaties, they were looking for tribal ‘leaders’ and these were not always easy to find nor necessarily willing to co-operate. On the other hand the tribes saw the British as just another faction, not unlike the Ottomans, entering the complex politics of the area, and thought they could be used and manoeuvred within the traditional patterns of inter-tribal relations. By the time it became clear that they represented a greater danger to the system it was too late: the tribes were deeply enmeshed with the British authorities and no longer had the strength to ignore them.

Starting with the signing of protectorate treaties with whoever appeared to be the main leader of what appeared to be the dominant tribe in any given area, Britain unwittingly laid the basis for its own future problems and for the rapid collapse of traditional intra- and inter-tribal relations.[9] How wrong things could go was shown by the example of the Amiri of Dhali’. Britain had problems with them from the earliest days, and added to these were the claims of the Ottomans and later the Imam to sovereignty over some or all of the so-called Amiri area ranging from the Radfan mountains to Qa’taba. This was one of the areas whose independence the Ottomans were forced to recognize in 1873. The first conflict occurred when the British recognized one chief Ali Muqbil in the course of a succession dispute; the Ottomans supported his rival and imprisoned the British nominee who soon escaped and was only reinstated three years later. In the following years the Turks manoeuvred among sub-sections of this group and the Amir of Dhali’ lost much of his influence and territory to ‘lesser’ chiefs. In the later years of the Century, the Amir had increasing difficulties with the Qutaibi, who were supposedly his vassals but were heavily armed and considered that they had the right to levy tolls on the Dhali’-Aden road where it passed through their territory. By the mid-1930s Belhaven reported that the situation had reached a high degree of absurdity, although this was no more than an extreme example of what was going on elsewhere:

‘The Qateibi tribe, through whose territory ran the road from Qataba and Dhala’ to Aden, had been subjected to a prolonged operation of air blockade. This method, much favoured at that time, entailed the subjection of a territory to desultory bombing of a harassing nature, until a fine was paid. Great satisfaction was felt when, after several weeks, the Qateibi paid the fine levied on them and agreed to give the Amir of Dhala’ hostages from their leading families, as a surety of their future good behaviour. The operations formed the subject of lengthy dispatches and much self-congratulation in Aden. To no one, however, did the conclusion of these operations afford more wholehearted delight than to the Qateibi, who had paid not one penny of the fine themselves and who had forced the Amir of Dhala’ to receive and to entertain up to twenty of their number as permanent unpaying guests at Dhala’.

That the Amir of Dhala’ had any influence over the Qateibi tribe was a delusion of the Aden Secretariat. He had none, unless he paid handsomely for it and, since he had frequent occasions to visit Aden, and his only road lay through Qateibi country, he paid often. The Qateibi were a virile, independent tribe, having no treaty with the British and owing allegiance to none. As soon as they had received the Aden Government’s ultimatum, they had passed it to the Amir, with threats. They had closed the road to him; but they allowed him to pay a visit to Lahej where, after long bargaining, he managed to borrow sufficient money from the Sultan to pay the fine levied on Qateibi and the additional fíne which they had levied on him. When the government suggested that the Amir should take hostages from them, he burst into tears; but they somehow heard of the suggestion and forced on him some twenty hungry savages, who lived in his best guest-rooms and threatened him with death and dishonour whenever the catering fell below their high standard. The Qateibi hostages at Dhala’ were some of the happiest men I have known. They would rock with laughter when they loosened full ammunition belts and puffed away at the Amir’s hookers, after a mutton stew of shocking dimensions. At last the Amir fled to Aden refusing to return to his country until the Qateibi hostages returned to theirs which they eventually agreed to do on the payment of a lump sum.’[10]

Having chosen a certain family as the supreme leaders of an area, the British were later forced to back up their choice against others who were often more powerful locally, had equal or greater resources, and firmly rejected the supremacy of the British nominee. By insisting on making a choice, British room for manoeuvre was restricted to seeking a candidate whom they considered most likely to serve their interests within the ‘ruling’ family and they then forced their choice onto the tribal council. Since their candidate was often challenged they would often find themselves using threats and force to support him.

This clientage soon developed into a system of subsidies which was originally introduced when the Government Guest House was opened in 1870. By 1880–81 it received 1,395 guests who were entertained and given presents on departure which in the same year amounted to Rs 46000 (£2,300 or twenty times that in today’s values).

‘The role it played in British relations with the tribes may be gathered from the sums of money spent and the fact that a carefully graded hospitality was offered. Tribesmen were divided into three categories for the purposes of entertainment... The whole system was geared to the pattern of social relationships in the hinterland, modified by the degree of friendliness of the individuals concerned towards the British authorities. Here was a fertile field for offering slights or flattery to tribal potentates.’[11]

Subsidies sometimes took the form of cash, but were most often in the form of rifles and ammunition:

‘The other major chiefs, and this meant, above all, the chiefs who had signed the various protectorate treaties, were also accorded special treatment by the Aden Government. Contact with tribesmen was channelled through them and, much to the disgust and anger of many tribesmen, only those who received a recommendatory letter from the appropriate chief were welcomed and entertained at the Aden Government Guest House — an institution which was now more active than ever before.

... Since the 1880s, Aden had been issuing rifles and ammunition to approved potentates in the hinterland, especially the Sultans of Lahej, and in 1897 these arms issues had been liberalised to enable British protégés to keep ahead of those with access to smuggled weapons ... Of course the method of issuing arms was modelled upon the system of paying subsidies and making presents. They went in the first instance to the chiefs, indeed many of the presents to the chiefs took the form of rifles and ammunition rather than cash.’[12]

Policy towards the hinterland was determined in the higher spheres of the British colonial establishment, but their instrument was the Arabic Department which later became the Arabic Office. The following account written in 1931 reveals both British attitudes to the hinterland tribesmen and how decisions on what appeared to be minor points to the British could affect the situation on the ground:

I remember with awe when first I entered this file-strewn place. On a high chair, such as those in use in eighteenth-century accounting offices in London, before a minute, elevated desk, sat a thin, elderly Arab, the interpreter. Desk and floor were littered with rustling papers. Two windows were blocked with contorted Oriental faces and a pandemonium of threats and insults filled the air, which was thick already with the fumes of the interpreter’s hubble bubble pipe, the long tube of which coiled among the discarded files. It seemed that the interpreter had refused, to recommend a grant of rifles to the bearded faces in the window, but had granted one to another lot of faces, thereby giving the latter a deadly advantage over the former in a private war; for which the interpreter was now being threatened with instant disembowelment. As I stood there, amazed, the police arrived and a messenger, in a red turban, delivered a box full of papers from Lake. The top one fell into my hands and, before I placed it on the interpreter’s desk, I read it. ‘After compliments’, I read, ‘the Arwali demand a gift of arms and gun powder. If they do not receive this they will make a pillage on the road.’ Below this I read, in a neat hand, ‘refused, M. C. Lake’. So far the interpreter had remained statue calm, his eyes on his desk, his pen poised, the mouthpiece of his hubble-bubble held in his left hand; just then one of the policemen, pressing forward to expel the faces from the window, stepped on the tube of the pipe and deprived the interpreter of his smoke. He exploded with a scream of rage and rose, papers cascading right and left. I backed out of the room. I asked the young clerk who was showing me round what was the meaning of the uproar we had just witnessed.

“It is the Indian System,” he said.’[13]

Intervention in the interior from the 1930s onwards

Under the leadership of Sir Bernard Reilly who governed Aden from 1930 to 1940 a new policy of intervention and promotion of ‘progress and development’ in the hinterland was developed by which protectorate treaties were replaced by advisory ones. Aden and the Protectorates up to that time were a department of the government of Bombay, with more remote control from Delhi and eventually by the India Office in London. Policy was directly oriented to support the specific interests of the British in Bombay, not even of those in India generally, for the perspective of those administrators was totally different from the expansionist and interventionist policies prevailing in the Colonial Office which controlled other parts of the British Empire. Various British officials in Aden had tried to disengage the towns and Protectorates from Bombay’s grip and eventually Reilly succeeded. In 1932 Aden was removed from the authority of the Bombay Legislative Assembly and put under that of the Viceroy of India as a Chief Commissioner’s Province, and in 1937 it was finally transferred to the Colonial Office and divorced from anything that happened or might happen in India.

Intervention in the Protectorates and in Aden continued till the last years of British presence in the area, except for a break during the Second World War, when Aden was restored to its primarily military role. Although expansion took place both in the town and in the Protectorates the pace was greatly accelerated particularly in Aden town which prospered and rapidly became a major international commercial centre, as well as an ever-developing naval and air force military base with the consequent services industries. The hinterland experienced little material benefits even in the more interventionist phase of the 1950s.

Despite the border settlement following the defeat of the Ottomans with the First World War trouble continued with the Imamate of Yemen, the Imam insisting on his sovereignty over the Protectorates, and this was only inconclusively solved in 1934 with the Sana’a Agreement which called for the withdrawal of the Imam’s troops from the various border areas of the Protectorates which they had occupied. Thereafter the Imam and his agents promoted dissidence against the British in the various sheikhdoms by supplying arms, ammunition and other necessities to groups who wanted to fight the British presence. Continuous dissidence against the British-supported leaders in the tribal areas was attributed by many to the conspiracies of the Imam whose aim was to create a united Yemen under his authority. However, although rebel tribesmen might accept money, weapons and ammunition from the Imam and his agents, that did not mean that they supported his political aims. On the contrary, their aim was invariably independence at the tribal level as national aspirations had not reached the hinterland in the 1940s, and only gradually did so in the 1950s. By the late 1950s the aim of all dissidence was ‘independence’ from colonialism, even though it is likely that in many cases this was defined as nothing more than the elimination of British interference in the internal affairs of the tribe, and the removal of the leaders imposed by the British. It was, of course, convenient as well as good public relations for British spokesmen to claim that the root of the troubles was the Imam, but such statements were no more than propaganda ploys. As reliable an authority as a former High Commissioner of Aden who was in office in the 1960s admitted that the aim of the rebels was independence and not unity with the Yemen under the Imam.[14]

The fragmentation of southern Arabian society in recent centuries was manifest in the rivalies between tribes and within tribes. As we have seen this was exacerbated by the new status acquired by petty rulers as a result of their Protectorate treaties with Britain in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Life became more dangerous with the introduction of more powerful and accurate firearms but also through the undermining of the traditional economy. Trade had in the past supported nomadic tribes in different ways: the caravan leaders and camel owners transported goods, other tribes levied customs duties to allow the goods to go through their territories, and finally some raided caravans. From the 1930s onwards three major factors put an end to this system: first the British claimed to control caravan routes and demanded free passage on the roads, coming into conflict with the tribes over customs dues and over raids. Further, although the Yemenis had obtained the new firearms, the British outdid them with airpower with which they were unable to compete. The second major influence was the introduction of motorised transport of goods which destroyed the livelihood of the camel owners and caravan leaders although the British introduced some ineffective measures to protect the camel caravans.[15] For example when, in 1937, the first road suitable for motor vehicles between Mukalla and Seiyun in Wadi Hadramaut was opened:

‘the fees for the use of the road were designed not only to give revenue but also, in conjunction with minimum fares, to protect the beduin camel traffic. In fact goods were not allowed to be carried by road unless they were perishable, too heavy for camels, or urgent, in all of which cases the freight charged had to be higher than that which would be charged for camel transport.’[16]

The third significant factor of change was the new interventionist ‘advisory’ type of treaty signed with the British; unlike the earlier ‘protection’ treaties, these stated that the local rulers would ‘take British advice on matters not related to religion.’[17] The first of these was signed with the Qu’ayti sultan in 1937 and the last was signed in 1957 but a number of statelets never accepted an advisory treaty, including Upper Yafi’ and Dathina. These advisory treaties meant the end of the independence of the rulers as they had to accept advice on internal affairs and in exchange could expect some crumbs in the form of financial aid for symbolic development projects in the fields of health, education and agriculture. The paucity of development which took place up to independence can be seen in the state of the country in 1967, discussed below. With the advisory treaties often came resident British advisers and daily interference in tribal politics, sustained with financial and other inducements, so for example a leader who was reluctant to take certain advice concerning traffic along a route would find that aid to build a school or weapons for his tribesmen were not forthcoming till he changed his mind.

Development expenditure was supposed to be financed by local taxes and British involvement was either symbolic or with a clear political purpose, as for example in the opening of the School for the Sons of Chiefs. The meagre resource base of most of the statelets was such that they were unable to finance any of the projects their populations needed. What little surplus the rulers succeeded in extracting went towards tribal support, ie the supply of arms and ammunition to their tribesmen, and to maintain the standards of hospitality required by their position. Their lifestyle was hardly different from that of their tribes-people, indicating that their wealth was not substantially greater, though they usually managed to have slightly larger houses than anyone else.

Against this background of turmoil, it is not surprising to find that at no time during the period of British occupation was the entire area at peace. Somewhere there was always some kind of armed rebellion on a smaller or larger scale. The character of this struggle changed over time: appearing at first to be just another form of inter-tribal dispute typical of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, it gradually worsened thanks to the introduction of rifles, motor transport and competition for control over trade routes. These contradictions eventually developed into an organised struggle for independence under a nationalist leadership in the 1960s. It is clear, however, that Britain’s main impact on the interior was the undermining of traditional structures by imposing an artificial rigidity which distorted their movement, by the support of certain leaders against others, effectively creating certain statelets at the expense of others which might have emerged had there been no treaties. More positively it was British influence which served to reduce the bloodshed caused by the new rifles in tribal feuding by forcing truces on the rival groups, whose relations had deteriorated to a state of permanent warfare and paralysis by the 1930s. How far the situation had deteriorated before the British intervened is best illustrated in the case of Wadi Hadramaut where by the 1930s families had been locked inside their houses for literally years for fear of being shot in a feud if they came out, and where for the same reasons agriculture had almost disappeared as people were unable to go and cultivate their land. In some cases they had gone so far as to dig tunnels so they could travel from house to field without being shot.[18]

Free access for all to the roads, and allowing motor vehicle traffic destroyed the economy of the caravan tribes and of those who controlled the trade routes without giving them any alternative economic activity, as there was no systematic expansion of agriculture and fisheries which were left to their traditional practitioners. These now had the advantage of not being shot, but the disadvantage of being taxed by rulers who had the support of the British administration. It is little wonder that the nomads who had previously controlled trade were hostile to the new régime.

While the interior stagnated and rebelled, Aden saw a phase of unparalleled expansion which was also to affect the future and the perspective that the people of the interior had of both the British and themselves. Aden was expanded as a military base when the British handed over defence of the protectorate to the Air Ministry in 1927 allowing the hinterland to be controlled more effectively with fewer men, as clearly the tribesmen could not respond in kind to airborne attack. In this way, the British needed very few men on the ground in the form of political officers who carried out negotiations with the tribesmen and called on airstrikes when military action was needed. This was yet another feature which favoured the development of Aden at the expense of the interior, as RAF personnel resided in the town where they could live in the style usual to colonial people, namely luxury beyond the wildest imagination of the average tribesperson.