Henrietta Moore, Todd Sanders & Bwire Kaare

Those Who Play With Fire

Gender, Fertility and Transformation in East and Southern Africa

London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology

Approaches to Symbolism and Ritual: The Impact of Phenomenology and Praxis Theory

Bemba initiation and bodily praxis

Ritual and quotidian praxis as interpretation

Gender symbolism and gender complementarity

Sex and reproduction or cooking and hunting

Gender Performance and Gendered Agency

What kind of agency does ‘performing’gender involve?

Part II: Ritual Symbols; Performances and Narratives

Gender and the Ihanzu Cultural Imagination

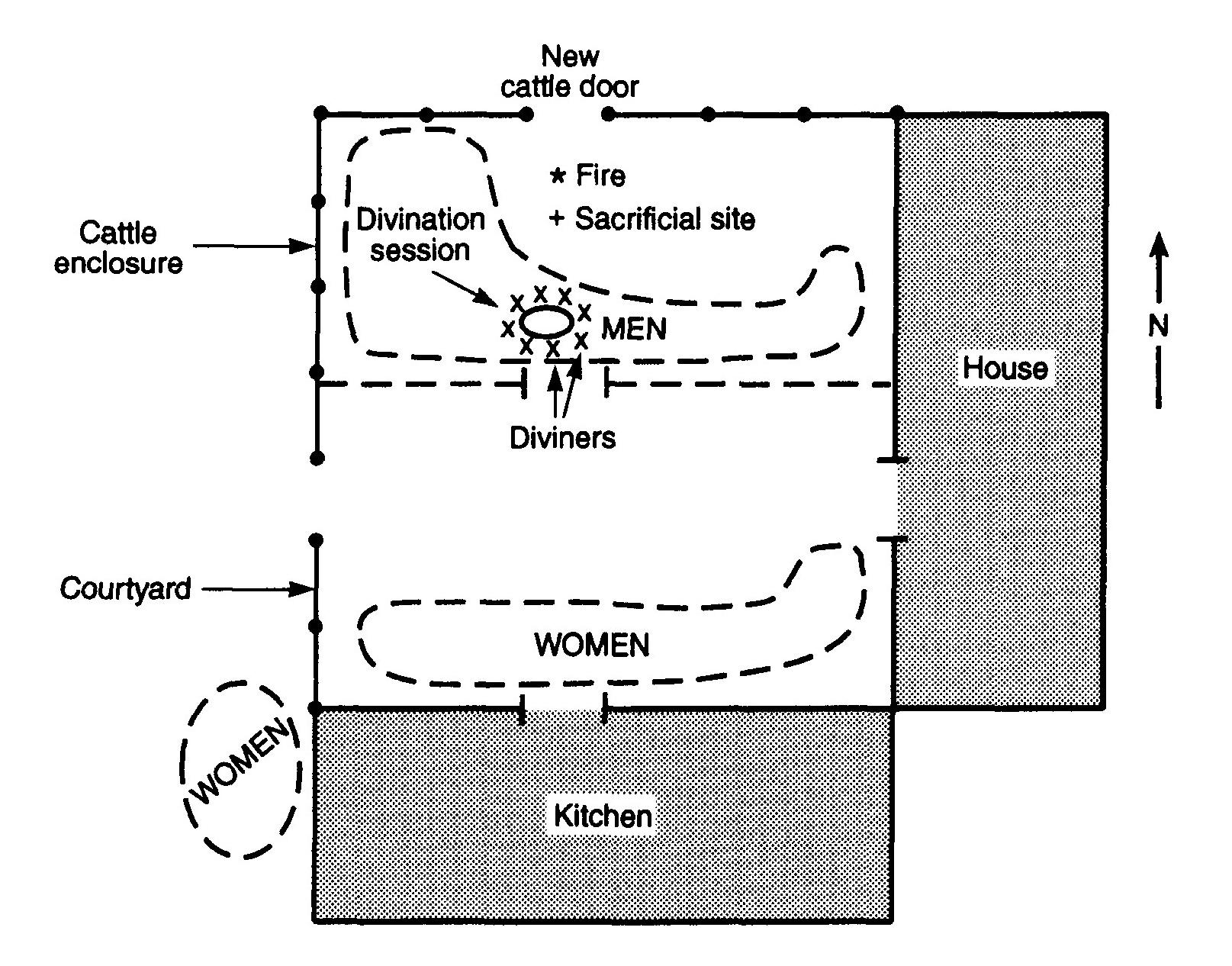

Ihanzu Ancestral Offerings for Illnesses

Initiating the offering (kukumbTka)

The sacrificial sheep and ancestral beer brewing

Meat for the spirits (kutagangila)

Beer for the spirits (kulonga shalo)

Gendered Performers, Gendered Performances

Ancestral addresses, offerings and the spirits

Chapter 3: The Lion at the Waterhole

The Body of Experience: a Conclusion

Chapter 4: First Gender, Wrong Sex

Is Sex to Gender as Nature to Culture?

Ideological Continuity Among the Khoisan

Khoisan Ritual Construction of Gender: Female Initiation

Male Aspects of the Maiden: Liminality and Counter-reality

Male Initiation: Parallels With Menarcheal Rites

Nature, culture and counter-dominance

Communitas: unity or multiplicity of experience?

The Discourses of Myth and Ritual Practice

God Above and God Below: Gendering the Divine

The Origin of Hunting and Gathering

Chapter 6: Creation and the Multiple Female Body

The Problem of the Feminine Divine

The Body Spiritual, the Body Social and the Body of Nature

Bodily Stories and Bodily Practices

Procreation, Production and Power

Part III: Gender, Fertility and Social Agency

Chapter 7: Dealing With Men’s Spears’

Situating the Girgweageeda Gadeemga

Ghoghomnyeanda: the Vulnerability of Labour

Offences Against the Fertile Female Body

Mobilizing the Girgweageeda Gadeemga

Case I. The Offence of Gidamuhaled

Case 2: The Offence of Tanzanian Politicians

The Power of Female Withdrawal and Re-emergence in the Compound

The Transformative Dynamics of Girgweageeda Gadeemga

Chapter 8: Gender Ideology, and the Domestic and Public Domains Among the Iraqw

Spirits, Ghosts, and the Divine

Circumcision, Marriage and the Household

Chapter 9: Women’s Work is Weeping

Gender and the Division of Labour

Human Reproductive Capacity and the Fertility of Women

Contained Power and Empowerment

Cumulative Compassion and Christianity

Gender, Emotion and Experience

Chapter 10: Chaos and Creativity

Creative Thinking and Cultural Imagination

London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology

[Front Matter]

London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology

Managing Editor: Charles Stafford

The Monographs on Social Anthropology were established in 1940 and aim to publish results of modern anthropological research of primary interest to specialists.

The continuation of the series was made possible by a grant in aid from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and more recently by a further grant from the Governors of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Income from sales is returned to a revolving fund to assist further publications.

The Monographs are under the direction of an Editorial Board associated with the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

[Title Page]

THOSE WHO PLAY WITH FIRE

GENDER, FERTILITY AND TRANSFORMATION IN

EAST AND SOUTHERN AFRICA

HENRIETTA L. MOORE TODD SANDERS BWIRE KAARE

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS MONOGRAPHS ON SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Volume 69

Routledge

Taylor &. Francis Group

LONDON AND NEW YORK

[Copyright]

First published 1999 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© The Contributors, 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form

or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including

photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only

for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Those who play with fire : gender, fertility and transformation in East and Southern Africa I editors, Henrietta L. Moore, Todd Sanders, Bwire Kaare.

p. cm. — (London School of Economics. Monographs on Soci< Anthropology; no. 69)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-485-19569-0 (cloth)

1. Rites and ceremonies-Africa, Eastern. 2. Rites and ceremonies-Africa, Southern. 3. Sex role-Africa, Eastern. 4. Sex role-Africa, Southern. 5. Body, Human-Symbolic aspects-Africa,

Eastern. 6. Body, Human-Symbolic aspects-Africa, Southern.

7. Africa, Eastern-Social life and customs. 8. Africa, Southern- Social life and customs. I. Moore, Henrietta L., 1957- II. Sanders.

Todd, 1965- . III. Kaare, Bwire, 1954- . IV. Series:

Monographs on social anthropology: no. 69.

GN658.T46 ... 1999

306’.09676-dc21 ... 99–1220

CIP

Distributed in the United States, Canada and South America by

Transaction Publishers

390 Campus Drive

Somerset, New Jersey 08873

Typeset by Acorn Bookwork, Salisbury, Wilts.

ISBN 13: 978-0-8264-6367-8 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-4851-9569-9 (hbk)

Contents

Notes on Contributors

PART I: INTRODUCTION

1. Gender, Symbolism and Praxis: Theoretical Approaches

Henrietta L. Moore

PART II: RITUAL SYMBOLS: PERFORMANCE AND NARRATIVES

2. ‘Doing Gender’ in Africa: Embodying Categories and the Categorically Disembodied

Todd Sanders

3. The Lion at the Waterhole: The Secrets of Life and Death in Chewa Rites de Passage

Deborah Kaspin

4. First Gender, Wrong Sex

Camilla Power and Ian Watts

5 Saisee Tororeita: An Analysis of Complementarity in Akie Gender Ideology

Bwire Kaare

6 Creation and the Multiple Female Body: Turkana Perspectives on Gender and Cosmos

Vigdis Broch-Due

PART III: GENDER, FERTILITY AND SOCIAL AGENCY

7. ‘Dealing with Men’s Spears’: Datooga Pastoralists Combating Male Intrusion on Female Fertility

Astrid Blystad

8. Gender Ideology, and the Domestic and Public Domains among the Iraqw

Katherine A. Snyder

9. Women’s Work is Weeping: Constructions of Gender in a Catholic Community

Maia Green

PART IV AFTERWORD

10. Chaos and Creativity: The Transformative Symbolism of Fused Categories

Anita Jacobson-Widding

Index

Notes on Contributors

Astrid Blystad is Associate Professor at the University of Bergen, Norway, in the Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care. Her most recent publications include ‘Peril or penalty: AIDS in the context of social change among the Barabaig’ in K.- I. Klepp, P.M. Biswalo and A. Talle (eds) Young People at Risk: Fighting AIDS in Northern Tanzania (1995), ‘La chant qui reveille la terre’, in T. Dom (ed.) Houn-Noukoun: Tambours et Visages (Paris, 1996) and (with O.B Rekdal) “‘We are as sheep and goats”: Iraqw and Datooga discourses on fortune, failure and the future’ in D.M. Anderson and V. Broch-Due (eds) ‘The Poor are not Us’: Poverty and Pastoralism in Eastern Africa (forthcoming).

Vigdis Broch-Due currently holds positions at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, and the Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala, where she heads a research programme entitled ‘Poverty, Gender and Conflict’. She has written a number of articles on the pastoral Turkana of Kenya, and has co-edited Carved Flesh/Cast Selves: Gendered Symbols and Social Practices (Berg, 1993).

Maia Green has been a Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Manchester since 1994, and has published several articles on conceptual systems among the Pogoro Catholics of southern Tanzania. She is currently co-editing (with F. Cannell) Words and Things: Power and Transformation in Local Christianities.

Anita Jacob son- Widding is a Professor at the University of Uppsala. She has published extensively on African cosmology, belief and ritual. Her forthcoming book, Chapungu: The Bird that Never Drops a Feather, explores gender identities in an African context.

Bwire Kaare studied anthropology at the London School of Economics, and is currently Lecturer in Sociology and Research Methods at the Institute of Finance Management, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He has conducted research among the Akie and Hadza (both also known as Dorobo) hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. He has written on Hadza relations with the state and the construction of their identities as minority groups in Tanzania.

Deborah Kaspin is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Yale University. She has published ‘A Chewa cosmology of the body’, American Ethnologist, 23 (1996) and is currently working on a book on Chewa ritual and political history.

Henrietta L. Moore is Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Gender Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her publications include Space, Text and Gender (1986), Feminism and Anthropology (1988), A Passion for Difference (1994), Cutting Down Trees: Gender, Nutrition and Change in the Northern Province of Zambia, 1890–1990 (with Megan Vaughan, 1994) and The Future of Anthropological Knowledge (1996).

Camilla Power is a Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of East London, in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. She is currently completing her thesis on cosmetics and gender performance in African initiation ritual, and has published several articles on gender, cosmetics and the evolution of ritual.

Todd Sanders is a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science, in the Department of Anthropology and the Gender Institute. His most recent publication, on rainmaking in Tanzania, appeared in Africa (vol. 68, 1998). Currently he is writing a book on witchcraft and modernity in East Africa.

Katherine Snyder is Assistant Professor at Queens College, City University of New York, in the Department of Anthropology. Her recent publications include ‘Elders’ authority and women’s protest: the masay ritual and social change among the Iraqw of northern Tanzania’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 3 (1997), and ‘Agrarian change and the farmers’ land-use strategies among the Iraqw of northern Tanzania’, Human Ecology, 24 (1996).

Ian Watts has recently completed his PhD at University College, University of London, having undertaken research into the archaeology of early modern peoples in southern Africa. He has published (with Camilla Power) a chapter in J. Steel and S. Shennan (eds) The Archaeology of Human Ancestry (1996) and ‘The woman with the zebra’s penis: gender, mutability and performance’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 3 (1997). His most recent publication is a chapter in R. Dunbar, C. Knight and C. Power (eds) The Evolution of Culture (1999).

Part I: Introduction

Gender, Symbolism and Praxis

THEORETICAL APPROACHES

HENRIETTA L. MOORE

In reality — there are no religions which are false. All are true in their own fashion, all answer, though in different ways, to the given conditions of human existence (Durkheim 1964: 3).

In many African societies, there is an abiding concern with sexual morality, with the power of sex and with issues of sexual access and denial (e.g. Heald 1995; Beidelman 1971). The larger context for this concern is the relationship between body processes and social processes, the way that the inner rhythms and functions of the body have an established set of concordances with social structures and cosmological understandings (e.g. Devisch 1985a; 1985b; Jacobson-Widding 1991; Kaspin 1996). Such concerns are mirrored in a wide range of ethnographic studies from all over the continent, and have formed the basis for structuralist and symbolist interpretations of a broad spectrum of ritual practices. An earlier division of intellectual labour within anthropology characterized a ‘French approach’ to African systems of thought as one based on the analysis of ideational systems, as opposed to a ‘British emphasis’ on social structure and action (cf. Fortes and Dieterlen 1965; Karp 1980; B. Morris 1987: chs 3 and 5). The validity of this division of labour between national traditions has been considerably eroded, if it was ever actually valid, by recent studies of African systems of thought and ritual practices (see Kaspin, ch. 3, this volume). However, Durkheim’s legacy in anthropology — in its most attenuated form — has been to leave his inheritors with the question of whether categories of thought are socially derived.[1] There might be few anthropologists at the present time who would accept this proposition uncritically, but the legacy of Durkheim as percolated through the works of Radcliffe-Brown (1952), Victor Turner (1967; 1969), Douglas (1966; 1970), Levi-Strauss (1966) and others continues to have a marked influence on theoretical orientations in the discipline. Hence, it is commonplace to find contemporary scholars of Africa asking questions about the relationship between forms of descent and gender symbolism, and enquiring as to how positive symbolic valuations of female fertility or gender complementarity can be related to systems of patrilineal descent and/or to the importance of uterine links within agnatic descent systems (e.g. Devisch 1988; Hakansson 1990; Houseman 1988; Jacobson- Widding 1985; Udvardy 1990).[2]

The studies collected together in this volume present new and recent ethnography on East and Southern Africa which extends and updates our knowledge of gender, ritual and symbolism in the region. The authors utilize recent theories on gender, subjectivity, agency and performance to examine their ethnography and suggest new directions for research. However, while all these studies take fresh theoretical approaches to their material, they nonetheless continue to struggle with aspects of the Durkheimian legacy and thus their contributions should be understood both as an attempt to develop new theoretical perspectives relevant to the changing nature of gender and symbolism in Africa, and as part of the developing historiography of anthropology in Africa.

Approaches to Symbolism and Ritual: The Impact of Phenomenology and Praxis Theory

Approaches to the analysis of symbolism in anthropology are extremely diverse when viewed in terms of their often self-avowed and detailed comparisons — scholars frequently and necessarily clarify their own positions by differentiating them from those of others.[3] But the basic theoretical orientations can be summed up as those which privilege underlying formal patterns or structures (structuralist), those that see social structure as the basis of symbol systems (socio-structuralist/symbolist), and those that prioritize local understandings and practices (phenomenological/ experiential). In practice, many writers have developed approaches over time that combine aspects of all three approaches, and frequently adopt the theoretical emphasis most appropriate to the material they are dealing with. The tension between abstract, comparative models and detailed empirical and experiential ethnography is a necessary condition of the domain of enquiry. No set of cultural symbols or ritual practices can be seriously analysed out of context, but neither can the similarities of existential struggle, cognitive capacities and physiological processes be ignored. The latter difficulty explains the prevalence of such terms and phrases as ‘the meaning of life’, ‘primordial unity’, ‘the ineffable’, ‘the sacred’ and ‘the divine’ in anthropological writings on ritual and symbolism. Such phrases and terms do not by their nature have clear-cut meanings or standard emotional correlates, and thus when subjected to critique by unsympathetic sceptics almost any writer on religious symbolism can be made to look foolish.

The issue of plausibility is further complicated by the fact that many anthropological explanations of ritual and symbolism exceed local exegesis (cf. Gell 1975; Lewis 1980). This is particularly the case when the explanation is comparative in nature, and in recent years the comparative project of anthropology has been subject to critique on this point as part of the turn away from ‘grand theory’ and ‘grand narratives’.[4] However, the larger principle is that any description of a culture is implicitly comparative because it is simultaneously a description of what it is not (Hastrup 1995: 7). It is axiomatic in anthropology that cultural symbols and rituals — in fact all aspects of culture — must be described in terms of the culture’s own epistemological concerns, and in that sense every description must remain faithful to local understandings. However, this is not the same thing as saying that all anthropological explanations can be or should be exact renditions of local exegesis. For one thing, this would ignore the problem of unequal distributions of power and knowledge, and fail to investigate how both of these work in the service of vested interests.

In the study of ritual and symbolism, there are also other theoretical and methodological difficulties. Language may provide a very indirect route to experience, and there are many cultural concerns that cannot be elicited from spoken words (Hastrup 1995: 42). The ability to make links between different cultural domains, different aspects of social experience, is frequently embodied in performance. The experience of engagement with a life-world this provides constructs practical activity as an interpretation of that world without necessarily engaging in philosophical discussion or the construction of articulated all-embracing models. This is why it is misleading to refer to ‘folk models’ if by this we intend to reduce such models to spoken exegesis (Holy and Stuchlick 1980; Jacobson-Widding and van Beek 1990). To privilege performance in this way is clearly not to imply that local exegesis does not exist or should not be privileged where it does, but simply to point out that not all forms of exegesis are linguistic, if by this we mean sets of articulated propositions (Jackson 1996).[5]

All over East and Southern Africa, gender and ritual symbolism are concerned with a series of tensions embedded in basic sets of oppositions: male/female; cold/hot; sour/sweet; sun/moon; dry/wet; day/night; raw/cooked.[6] These oppositions are connected to elements of the natural world — fire, blood, water, sex — that emphasize the transformative power of symbol systems and their technological relation to the world. ‘Those who play with fire’ are those engaged in living bodily, social and cosmological worlds constructed in terms of such oppositions. Not all oppositional pairs have equal prominence in all social contexts, and each society constructs and lives out the particularities of its symbolism in a specific way, but the major concern of ritual practice is to manage relations within and between these oppositions — sometimes through harmony, sometimes through mediation and transcendence. What is significant about these oppositions is that they are corporeally embodied and stem from corporeal experiences (McDougall 1977). It is the body that provides the most immediate and physical point of reference for the individual’s relation with herself, with others and with the world (Devisch 1985b: 591). The experiences and sensations of the body thus provide concrete images for other processes and forms of connection. In order to ground these assertions, it is necessary to review some of the theoretical assumptions and consequences of recent writing, and provide some ethnographic examples.

The larger context in which symbolic oppositions are powerful and find meaning in East and Southern Africa is a concern with the continuity and maintenance of the social and natural worlds and their relation. In this context, it is ideas about gender and reproduction that both undergrid and encompass the larger set of symbolic oppositions. The bodily engagement with gender distinctions and social and biological reproduction provides a mechanism for the externalization and transposition of symbolic oppositions onto the spatio-temporal structuring of the environment, social structures and relations and the cosmos. The Yaka of Zaire, for example, see gender categories and gender relations as associated with birth, death and the succession of the generations. These processes they liken to various processes of plant growth — rising of sap, flowering, bearing of fruit, and decay. This gives rise to ideas that some foods are appropriate for women and some for men, and links certain colours to the genders. Motifs of death, regeneration and birth are thus intertwined with aspects of the natural world, and these motifs form the basis for the transition rituals of initiation, enthronement and burials/funerals (Devisch 1988; 1993: ch. 2; see also De Boeck 1994b; Stevens 1995). The Yaka case is specific in its particularities, but is otherwise paradigmatic for the region, as its comparison with the ethnography presented in this volume shows.

However, it would be a mistake to see Yaka symbolism as purely a form of representation, or to imagine that anthropological analyses of symbolism and ritual that identify pervasive oppositions that are extended and transposed across many domains are simply idealized or ideational accounts. Recent anthropological accounts of symbolism and ritual in the region (e.g. Devisch 1993; Beidelman 1997; Taylor 1993; Kratz 1994) have emphasized that the sets of oppositions identified in analysis are part of a symbolic logic that underpins a philosophy of social and natural continuity and reproduction that is forged by the demands and requirements of ecology and ways of life. This is a point made forcibly by Kaspin and Broch-Due in their articles in this volume. Symbolism in these contexts is about a concrete relation with a physical world where the fertility of humans, plants and animals has to be managed in ritual as well as in day-to-day activities. Recent work on symbolism and ritual in the region should thus be distinguished markedly from earlier structuralist analyses which dealt with symbols as if they were abstracted from the material realities of day-to-day living. The intimate relationship between knowledge and power, on which the parallel management and regeneration of the natural and social worlds depends, links cosmology to a knowledge of the forces that effect outcomes in the world (Herbert 1993: 1–3; Sanders, this volume; Kaare, this volume). The social and symbolic manipulation of gender — as the basis for reproduction and continuity — legitimizes and disguises social orders of inequality, distinction and reciprocity (Devisch 1985a: 697; Snyder, this volume; Blystad, this volume; Green, this volume).[7] Symbolism and ritual are thus about the management of a lived world and its material conditions, and not just about its representation, and that process of management is sensuous, physical and practical, and not simply ideational and intellectual.

Thus, this contemporary work — which has been profoundly influenced by praxis theory and phenomenology — should also be distinguished from an earlier anthropology (see Douglas 1970; Leach 1976; Tambiah 1968; 1979) that viewed bodies as representations, and symbols and rituals as means of communication. The main problem with this work is its assumption that symbols and rituals represent, dramatize or enact prior concepts, meanings and codes. The primary focus of enquiry is ‘What does this symbol/ritual mean or stand for?’ This is true even for those scholars who espouse a performative approach to ritual, where symbols and ritual dramatize or enact key social values, or conflicts between such values or between aspects of social structure (e.g. V. Turner 1967; 1969). Performance theorists might be more concerned with ‘what do symbols and ritual do?’, but they still approach that question through a hermeneutic of meaning that privileges the linguistic.

The notion of performance has obvious links and continuities with praxis theory in anthropology (Ortner 1984). Praxis theorists emphasize that the world is both structured and structuring, the aim is to mediate, or, at least, comprehend the dialectic between the dichotomies of structure/agency, material/symbolic. In its most useful formulation, praxis theory forces a confrontation with the act itself, and marks a move away from an over-reliance on linguistic interpretation. A focus on acting has necessarily been conjoined with a return to the body, where this concern helps to mediate, but not resolve, a further set of dichotomies between individual/society, subject/object and mind/body. In anthropology, theorists have drawn on the work of Pierre Bourdieu (1977; 1990) and more recently on that of Merleau- Ponty (1962; 1963) as a means of combining praxis theory with phenomenology. The resulting theoretical perspective has some interesting consequences for the analysis of ritual and symbolism, and, in particular, gender.[8]

There are some tensions in melding together the work of Bourdieu and Merleau-Ponty. Bourdieu has little time for phenomenology which he views as a form of naive subjectivism that ignores the historical and cultural conditions under which individuals come to self-consciousness (Bourdieu 1990: ... 25–6).[9] However, the value of theoretical approaches which draw, to greater or lesser extent, on the writings of these two theorists is a concern with forms of knowledge as incorporated in physical activity. Merleau-Ponty argues that bodily actions are not to be understood as expressing or objectifying meanings originating in the mind. The meaning is in the action itself, and should not be reduced to what can be thought and said (Merleau-Ponty 1962). Michael Jackson’s work on the Kuranko develops this perspective and shows that the meaning of body praxis is not always reducible to cognitive and semantic operations, and that body movements can make sense, and make sense of the world, without being intentional in the linguistic sense (Jackson 1989: 123; Blystad, this volume). ‘The meaning of practical knowledge lies in what is accomplished through it, not in what conceptual order may be said to underlie or precede it’ (Jackson 1996: 34).

Social praxis from a phenomenological viewpoint is concerned with the experience of self as part of the experience of the relation of self and other. Thus, phenomenology is never about individuals acting alone, and the question of consciousness, of subjectivity, is always an issue of intersubjectivity, of relating to others. To live in a life-world is to continually adapt to and be subject to conceptual orders and social discourses, but this is not the same thing as saying that experience is only constrained to, or faithful to, such orders. Experience of the world is the result of a project of physical engagement with the world and can thus never be the result simply of rule-following or subject to final closure.

Bourdieu takes a slightly different approach because, while he is concerned with practical knowledge and with the practical mastery of schemes of perception and action (habitus) learnt through practical engagement with the world, he is less interested in the sensory and inter subjective basis of much bodily knowledge. In many societies in Africa, different kinds of knowledge are associated with different parts of the body and much is made of the sensory and practical acquisition of knowledge (see Broch- Due, this volume). For the Yaka, for example, the ear is how the child learns of the world, and the heart is the centre of moral vision and social responsiveness, while the liver is the seat of negative and inward-turning feelings (Devisch 1993: 139–41). The way that the body is literally orientated towards, and physically engaged with, the world is an important part not only of knowledge acquisition, but of the very understanding of knowledge itself and of its effects on the world, on self and on others. But Bourdieu’s interest in the body is more narrowly confined to an analysis of kinaesthetics as a form of mnemonics.

The habitus is defined as a set of generative cognitive and motivating schemes produced within a particular set of material conditions, but for Bourdieu these conditions are those of historically produced social divisions and distinctions linked primarily to productive relations. The schemes comprising the habitus are ‘structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures’ for cognition and action (Bourdieu 1990: 53). Practical knowledge of the world is generated through the engagement of the habitus with the world, but this form of practical knowledge is embodied in the knowledge of how to proceed, it does not necessarily come into language. Cultural distinctions and cultural values thus produce and are produced by daily activities, but in a way that is not recognized, or only rarely, by those who carry out those activities. It is possible to

instil a whole cosmology, through injunctions as insignificant as ‘sit up straight’ or ‘don’t hold your knife in your left hand’, and inscribe the most fundamental principles of the arbitrary content of a culture in seemingly innocuous details of bearing or physical and verbal manners, so putting them beyond the reach of consciousness and explicit statement (Bourdieu, 1990: 69).

But, in spite of his concern with unthought practical action in the world, Bourdieu’s emphasis is still on the logic of the generative schemes (habitus) and thus behind his theory of practical knowledge lies a theory of cognition very close to that of Levi- Strauss.[10] However, because Bourdieu is less concerned with the individual and more concerned with the conditions for social reproduction, his work incorporates an analysis of the material conditions of existence and maintains an emphasis on ideology, dominance and power that is quite absent from the work of Merleau-Ponty. This materiality is crucial for an understanding of gender, ritual and lived symbolism.

However, what anthropologists have elicited — and the reason they draw together these somewhat divergent theorists — is the potential for understanding symbolism and ritual in a way that integrates social structure and individual experience through an engaged knowledge of the world that is practical, unthought and sensuous. The result of such an approach is a focus on the body and on how the experiences and capacities of the body produce symbols that operate across different cultural domains, setting up homologies among diverse levels and experiences, social categories and values. What is distinctive about the approach is that it does not treat the relationship between embodiment and symbolism as one of semantics, nor does it view the body either as a tabula rasa for cultural representations or as an object of representation (see Blystad, this volume).

Bemba initiation and bodily praxis

An example here can be provided through a rethinking of Audrey Richards’s analysis of the initiation rite for Bemba girls, chisungu (Richards 1982).[11] The chisungu ritual involves, like all other initiation rites in Africa, a great deal of practical mimesis, in which symbolic elements relating to several domains of Bemba life are enacted and worked over. The women in charge told Richards that the purpose of the ceremony was to teach the girls and make them clever. The women claimed to be teaching the girls how to bear and bring up children, keep house, manage food supplies and garden. But all Bemba girls know how to cook, garden, collect firewood and so on long before they go into the chisungu ceremony. It is clear that they do learn secret words and songs, and primarily they learn the secret songs and multiple meanings associated with the mbusa, the ‘sacred emblems’, which include clay figurines, wall paintings, and small bundles of objects representing the domestic and productive life of the Bemba people. These ‘sacred emblems’ are shown to the girls on various occasions during the ceremony. They also learn the special language and taboos associated with relations between women and men, and on which the successful fertility of a Bemba marriage, and indeed the fertility of society and the land, depend.

This represents a substantial body of knowledge, but Richards notes that in many of the rituals associated with the month-long rites, the meanings and symbolism employed were not only obscure to her, but also apparently to the participants (Richards 1982: 55). Moreover, the ritual does not have a fixed script: the order and timing of its component parts vary from one occasion to another, the verses of the songs and the dance performances change, and, whilst saying that they are adhering to the way of the ancestors, the performers insist on the ambiguity and multiplicity of meanings. In view of the absence of any formal instruction in the course of the rite, and the fact that on various occasions the initiates were kept out of the thick of activities apparently so that they could not participate or look too closely at what was going on, Richards was puzzled by exactly what the girls were learning, and concluded in characteristic style: ‘If any useful information was handed out during the chisungu one would be inclined to think that the candidates themselves would be the last people to have a chance of acquiring it’ (Richards 1982: 126).

What Richards did not see was that the bodily praxis of the initiation ritual literally incorporates its moral teachings. The preparation, presentation and handling of the mbusa take up much of the time given to the ritual. Mbusa literally means ‘things handed down’ and these objects act as mnemonics for a series of songs and dances appropriate to each object, and for the moral and spiritual precepts contained in the multiple sets of meanings associated with each mbusa. In many of the individual rites of the chisungu, instructors and initiands use their mouths as much as possible, rather than their hands, to handle the mbusa and complete various tasks. During the ‘honouring of the mwenge tree’, the senior women sing a refrain: ‘Pick up what you have, Pick up things with the mouth’ (Richards 1982: 93). The concrete nature of the knowledge which is passed from senior women to young girls in the chisungu ceremony is embodied in the transfer by mouth from one woman to another, in order of seniority, of the corporate knowledge contained in the mbusa, which is literally the ‘thing handed down’. In various contexts, the senior women in charge of the ceremony open containers with their mouths to reveal hidden mbusa (Richards 1982: 78–80), while the girls acknowledge the truth of the knowledge handed down to them through the mouths of senior women through such acts as opening bundles of firewood with their teeth (Richards 1982: 107), and placing a marriage purification pot on the fire with their mouths (Richards 1982: 77–8).

It is a mistake to underestimate the importance and power of an embodied knowledge which does not require precise linguistic referents. This does not mean that language and linguistic interpretations are not important in the ritual or that the Bemba do not use the mbusa as straightforward mnemonic devices which assist initiates and others in remembering various moral precepts. However, the Bemba make use of bodily metaphors that indicate how general precepts are to be understood as sensible truths, that is as a form of knowledge which has a concrete, sensuous relation to the world through the body. The fact that symbols are concretized in the body in forms which have no direct linguistic referent accounts perhaps for Audrey Richards’s puzzlement about what the girls were learning and for her assertion that some of the meanings of the rites were obscure. The ambiguity of meaning associated with embodied experience is something which can only be incompletely copied in language, and hence the women’s insistence on the multiplicity and fluid nature of the linguistic meanings associated with the mbusa. The mbusa act as mnemonics not for the linguistic meanings embodied in verbal exegesis, but for the physical experiences which make up the lived world of sexuality, fertility and gaining a living, as well as for the long reflection on those activities which is the chisungu rite.

Thus, what the rite achieves is a physical and symbolic manipulation of the body in relation to the world, and of the world in relation to the body. The rite becomes part of a lived relation to the base metaphors of Bemba culture which are themselves evident in the productive and reproductive relations of Bemba life. This is what Bourdieu intends when he says that ‘the mental structures which construct the world of objects are constructed in the practice of a world of objects constructed according to the same structures’ (Bourdieu 1977: 91). This in turn makes sense of his assertion that ‘The mind is a metaphor of the world of objects which is itself but an endless circle of mutually reflecting metaphors’ (Bourdieu 1977: 91). However, it would be a mistake to move from this statement to the assumption that the movement of the body in space or the set of embodied actions of an initiation rite have a ‘meaning’ beyond the acts themselves, to assume, in other words, that the act stands for something else. The act is not the representation of symbolic principles, but rather a lived interpretation of them, an interpretation which does not require a linguistic exegesis or have to enter into discourse. The meaning of the act can be the act.

This explains how homologies and hierarchies are created among and across diverse levels and domains of experience, social structures and values. Body space is integrated with social and cosmic space by virtue of the fact that they are all constructed in terms of the same symbolic principles. One of the major songs of the chisungu ceremony that is sung throughout the rites is one where seniority between senior and junior women, between women and men, and between chiefs and commoners is grounded in the make-up of the human body: Kuapa takacila kubea (the armpit is not higher than the shoulder). This statement does not require elaboration or exegesis, it is itself the interpretation, and the evidence for its veracity is given in the body. Statements such as this are verbal correlates of patterns of social interaction and sets of bodily dispositions within a particular environment (Jackson 1989: 147). They are not just metaphors for social relations: they are also the material bases of individual lives. Relations of seniority and respect maintain economic and political life within families, villages and chiefdoms. The Bemba draw on base metaphors in the chisungu ritual and elsewhere which refer to practical and bodily activity within their environment. An uninitiated girl, for example, is referred to as a ‘weed’ or an ‘unbred’ pot, and this relation of likeness is not a mere figure of speech, because these allusions to domestic and agricultural life disclose real connections between personal maturity and knowledge, and the ability to provide for others (Jackson 1983: 132).

Ritual and quotidian praxis as interpretation

This last point is an important one because it emphasizes that when we speak of body, social and cosmic space as constructed according to the same symbolic principles, we should understand that this process of construction is achieved practically, through physical engagement with the world, and does not have to rely on verbal exegesis or enter into discourse, as noted earlier. This does not mean that symbolic principles or the homologies established among domains cannot become the subject of discourse under specific circumstances. The fact that discursive interpretation and disputation is possible alongside physical engagement is one reason why some individuals are much more knowledgeable — in the sense of intellectually coherent — about symbolism and ritual than are others.[12] However, the homologies established between different levels of experience and different domains of life are not overdetermining. The repetition and analogical extension of basic symbolic principles, based on the body’s orientations and movements in the world, provide a loose sense of systematicness without ever fixing or defining in any one specific way the meaning of symbolic contrasts, relations and transformations.[13] The contrasts, relations and transformations are the result of daily and ritual practice. I argued in my analysis of domestic space among the Marakwet of Kenya that the organization of space has no meaning outside practice, outside the activities of knowledgeable social actors who invoke meanings, some intended and some not, through their actions (H.L. Moore 1996: ch. 5). In this sense to speak of ‘structuring structures’, ‘sets of oppositions’, ‘dual classification’ systems is not necessarily to reduce social and symbolic systems to some kind of formal taxonomy or abstract ideational system, whether owned by the ethnographic subjects or only by the anthropologist. The aim rather is to give the same weight to embodied action and embodied cognition as a form of interpretation, as to language and linguistic exegesis (see Kaare, this volume; Kaspin, this volume; Sanders, this volume).

As a way of comprehending the theoretical shift this entails, we might usefully term — in a formal sense — many contemporary analyses of African ritual and symbolism (e.g. De Boeck 1991; H.L. Moore 1996; Devisch 1993)[14] that draw on aspects of praxis theory and/or phenomenology ‘post-structuralist’, in the sense that the analysis they provide depends upon a prior recognition of oppositions, symbolic codes or base metaphors — a move that looks very structuralist — but also emphasizes that constellations of meaning are only invoked in practice, that signs and symbols only have meanings in specific contexts, and that those meanings are not fixed or closed. It is because the interpretations given to body practices in one context are never entirely separable from those invoked in others that meanings are implied, but never fixed. This form of analysis depends upon a play of differences among certain elements, but one where signification is deferred.[15] Thus, in ritual and in day-to-day activity, oppositions and symbolic principles are invoked, brought into play, but never resolved, never finalized. There is no necessary logical end to the significations set in motion, but only a processual movement through them. This does not exclude the processes of disputation, strategy and violence which are moments when actors seek to freeze process and impose particular interpretations. The paradox is that the apparent systematicness of the symbol system comes from its very fluidity, from the fact that everything appears to refer to everything else in an endless process of deferred meaning. Anthropological models, like local exegesis, are just abstractions of this process or attempts to freeze one moment of it. This is one reason why symbolic principles and ritual practices appear so consonant with social structures, with conflicts within and between structures and values, and with vested interests and distributions of power.

Gender symbolism and gender complementarity

A vast literature exists on gender in Africa, and much of it is concerned with the revaluation of women and women’s role in society.[16] Topics include the impact of colonialism on women’s status and political participation, how women seek to advance their economic and political interests, the impact of poverty and urbanization on women, the changing nature of the sexual division of labour and the effect of development policies, agricultural intensification and the economic organization of households, the changing nature of marriage and kinship ties, and the role of women in ritual and religion. However, in spite of the mass of available material, the cultural construction of gender and sexuality has remained somewhat underdeveloped.[17] It is instructive in this regard to compare the data from Africa with that from New Guinea, for example. Where ideas about femininity and masculinity, and their connection to notions of fertility and social transformation, have been explored in East and Southern Africa it has mostly not been by scholars concerned with gender, but by scholars writing on ritual symbolism and cosmological/ideational systems (e.g. Devisch 1993; Jacobson-Widding 1985; 1991; Beidel- man 1993; 1997). This should come as no surprise, since it turns out that it is impossible to write about symbolism, ritual and cosmology in the region without writing about gender. Gender is the key structuring principle and base metaphor of cosmologies and symbol systems, and thus many anthropologists writing on African societies in the period 1930s-1970s were analysing aspects of gender rituals and gender symbolism long before there was any imperative in anthropology to consider gender or reevaluate the data on women.[18] Much of the early writing focused on initiation where anthropologists at once noted that such rituals make use of male and female symbolism, and that male initiates may be explicitly feminized or associated with feminine powers and symbols in the course of the ritual, while girls may be masculinized or associated with masculine symbols and powerful productive and regenerative forces in the world (e.g. Vansina 1955; V. Turner 1967: ch. 5; Krige 1968; White et al. 1958). This breaking down of symbolic classification immediately caught the attention of ethnographers who saw these processes as being at odds with patrilineal and/or patriarchal ideologies and practices in the societies they were studying. The explicit reference to boys as women or wives in initiation (e.g. Vansina 1955; V. Turner 1967) and the wearing of men’s clothes and the mimicking of male activities by girls and women during certain rites (cf. Power and Watts 1997; Power and Watts, this volume) led inevitably to a discussion of ritual role reversal and ritual transvestism. Gluckman interpreted such reversals as rituals of rebellion, where women literally rebelled — albeit symbolically — against their inferior status. Kaare (this volume) and Power and Watts (this volume) provide recent ethnography with which to criticize this thesis, thereby extending the earlier criticisms made by Rigby (1968) and Krige (1968), as well as providing alternative interpretations for these apparent processes of reversal.

One issue that the symbolic manipulation of gender roles and cosmological principles raises — and one which demonstrates how pertinent the inherited Durkheimian dilemma remains — is the problem of whether evidence for gender reversal, equality or complementarity in ritual and/or other contexts is really at odds with dominant ideologies of patrilineal and/or patriarchal dominance. There are a number of points to be made here. The first concerns anthropological interpretation or anthropological bias. Broch- Due points out in this volume how myths celebrating the creative force of the female divine have failed to find their way into various anthropological accounts of the Turkana. It is quite clear that in spite of much recuperative ethnography that anthropologists have routinely misunderstood the female nature of the various creative forces associated with cosmological principles and systems in many societies in the region (Burton 1991). The result, in the past, has been to express some disquiet or surprise when female and male principles are revealed as equally powerful and/or as complementary. In her critique of Gluckman, Krige pointed out that the Zulu girls’ puberty rite could not be analysed in isolation, but had to be seen as part of a larger ritual cycle associated with fertility, involving rainmaking and the health of animals and crops. Central to these rites was the female deity Inkosazana whom Krige complained had never received serious anthropological attention (Krige 1968: 183; cf. Berglund 1976). More recent ethnography of the region has emphasized both gender complementarity in many ritual contexts, and the importance of seeing individual rites as part of a larger set of ritual practices (cf. Kratz 1994; Werbner 1988). Several writers in this volume stress that initiation rituals have to be seen as part of a larger set of rites associated with fertility, including death rituals (Blystad, Green, Kaspin, Snyder, all in this volume).

The issue of anthropological interpretation is not however restricted to the domain of the cosmological and the divine. This is perhaps unsurprising because the larger problem is one about allowing a western conception of the dualistic nature of the categories ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ to overdetermine ideas about power, potency, life force and fertility. This difficulty is revealed in a variety of studies in the region through a discussion of kinship. The issue can be neatly summed up as the ‘problem of the maternal’. Recent anthropological accounts have seen a resurgence of feminine symbols, women’s agency, uterine links, women’s reproductive power, and the feminine principles of the cosmological and natural worlds. I use the term ‘resurgence’ because evidence for all these things can be found in earlier ethnographies of the region concerned with ritual. However, what is of interest is the impact this resurgence/re-evaluation has had on the study of kinship. Societies which were unilineal suddenly appear to acknowledge uterine links or dual lines of descent, and in some cases anthropologists are even unable to agree on the appropriate classification of the descent system (e.g. Feldman- Savelsberg 1995; Stevens 1995; Broch-Due, this volume; Snyder, this volume; Udvardy 1990).

Of course, Wendy James remarked twenty years ago that matrifocal ideas are present even in the most ‘notoriously patrilineal societies’ (James 1978). She attributed the tendency of anthropologists to overlook this point to an overemphasis on jural structures, but this explanation ignores the paradoxical fact that matrilineal societies have also been subject to the same interpretative bias. Matrilineal societies in the region have frequently been portrayed as subject to specific structural conflicts. The implication here is that descent in the female line — sometimes with resources held or controlled by women — causes understandable conflict with patriarchal ideologies and the desire of men for control over their children. If this is the case, then how do we explain the existence of matrilineal societies? It might be useful here to start with the role of the mother’s brother.

The mother’s brother is most often portrayed as exemplifying male control and male dominance in matrilineal contexts, but several societies in the region refer to him as the male mother or mother without breasts. De Boeck points out in relation to the Aluund that the avunculate represents the uterine location of the vital life-flow (mooy), and that the maternal uncle should be seen as a life-giving body, as the point for the intergenerational transmission of the life-flow that perpetuates the lineage (De Boeck 1994a: 262). It is interesting in this regard that anthropologists habitually refer to this male individual as the mother’s brother (a sibling relation) rather than as the mother’s son (a parent/child relation); the latter emphasis might arguably be of more relevance to an understanding of matrilineal kinship.

All the societies of the region are concerned with the creative life forces of the world and their manifestation through fertility and reproduction. Yet, anthropologists, with some exceptions, have found it difficult to understand the nature of these life forces.[19] Devisch points out for the Yaka that ngoongu, the regenerative forces, are embodied by the chief and metaphorically transferred during various rites from the cosmic to the bodily and social orders. Ngoongu, according to Devisch, is a higher-order principle of fertility that comprises genitor, genitrix and ancestor or child: that is, two genders and two generations (Devisch 1988: 263). The important point here is the relationship between gender and generation, and I would argue that the ngoongu might be better understood as a principle of fertility embodied within the transformative potential of reproduction. It is the fact of reproduction, and its often precarious nature, that accounts for the focus both on gender and on fertility in the cosmologies, rituals and quotidian practices of many societies in the region (see Broch-Due, this volume; Blystad, this volume). What reproduction introduces is the centrality of the maternal and, in particular, of the maternal body. This body encapsulates and encompasses the regenerative life forces of bodily, social and cosmic continuity, and the maternal must therefore be present in some form in all kinship systems.[20] However, the maternal image is a complex figure and it is probably a mistake to view it as purely ‘female’ in terms of a fixed dualistic categorization which opposes male and female principles. The maternal body contains both genders, not just because indigenous theories of procreation speak of the mixing of male and female elements to form the foetus in the womb, but also because the maternal body is the only body with the capacity to reproduce both genders. More than this, the maternal body has the capacity, through pregnancy, to become two bodies, to produce the offspring that will guarantee bodily, social and cosmic continuity: future reproduction. In this sense, the maternal encapsulates division in unity, but as a symbol it can no more be reduced to the bodies of actual women than it can be disassociated or disconnected from them. This raises the old question — which I have characterized as one of Durkheim’s legacies to anthropology — what is the relationship between the symbolic and the social, and how should we understand it? One way to answer this question is to return to the ethnography and to the way the societies of the region handle the relationship between the social and the symbolic.

Sex and reproduction or cooking and hunting

A focus on reproduction and the maternal body may help to explain the importance of uterine links in all forms of kinship systems (see Snyder, this volume; Broch-Due, this volume),[21] but only when the wider links between sexuality and reproduction are taken into account. A pervasive set of associations between sex and eating are characteristic of the societies of the region. The result is that symbolic ideas concerning reproduction and the maternal body are woven together with quotidian activities and the practical arrangements of managing a household, gaining a living and maintaining social relationships (see Kaspin, this volume; Blystad, this volume; and Broch-Due, this volume). In the ideal Bangangte household economy, the husband provides his wife with meat, oil and salt which she mixes with the ingredients she produces herself (maize, beans and peanuts) to produce a cooked meal (Feldman-Savelsberg 1995: 488–9). The complementary contributions to the reproduction of children and household are further concretized in the associations established between certain objects, practical activities, and parts of the human body. In the case of the Kaguru, for example, the male centre-post of the house and the female hearthstones next to it symbolize coitus and the complementary contributions of women and men to the maintenance of the household, family and kinship. A similar pairing is evident in the relationships between other paired objects necessary for production and food preparation, and parts of the body. Metaphors for the penis include a spear (mugoha), stone pestle (isago) or wooden pestle (mtwango); a vagina is a stone mortar (luwala), wooden mortar (ituli), calabash, pot or basket. Euphemisms for sexual intercourse also link human sexuality to the transformation of foodstuffs and the management of modes of livelihood: to pound flour (kutwanga), to grind flour (kusanjila), to make fire (kuhegesa) are all euphemisms for the sexual act (Beidelman 1993: 39–40).

Throughout the region, children are spoken of as the product of cooking or firing, the result of a transformation brought about through fire. Fire is a dominant base metaphor for social transformation and hence the title of this book. Children are frequently said to be cooked in their mother’s wombs, a fact which produces a pervasive and seductive culinary symbolism relating to procreation and reproduction (e.g. De Boeck 1994a: 271). Children are the product of the mixing of male and female fluids/ substances: the blood/semen of the man and the menstrual blood of the woman (Beidelman 1973: 136). Both these substances carry life itself, part of the vital flow, and consequently a set of common associations links semen and/or the moistness of the vagina (and sometimes blood) with rain, thus establishing an intimate connection between the proper management of human sexuality and the fertility of the human, natural and cosmological worlds (Sanders 1998).

If the maternal body and images of cooking underpin both the female contribution to fertility and childbearing, and the complementarity of the genders in the successful maintenance of life, hunting is an activity that marks the male contribution to lifer giving. In this sense it is represented as the symbolic equivalent of giving birth. For the Yaka, for example, fertility involves fermentation or cooking. A man’s semen rots in the woman’s womb and the odour of sexual intercourse, representing the welding together of life forces, is likened to the smell of the game carcass which, through cooking, will also be transformed into life-giving nourishment (Devisch 1993: 136). Hunting in many societies in the region is associated with mastery of the wild/bush, with the bringing into the social domain of part of the vital force of the natural world (cf. Beidelman 1997: 251; Kaspin, this volume; Power and Watts, this volume; and Blystad, this volume). Hunting, like menstruation and childbirth, sheds blood to bring life. Death and decay are thus part of the process of regeneration (cf. Devisch 1988: 264; Kaspin, this volume). The association of women with prey and men with hunters is represented in many initiation rites (e.g. V. Turner 1967; Richards 1982; Kaspin, this volume), and establish links across domains of production, linking human sexuality to the natural world and the powerful forces of death and regeneration.[22] This explains, amongst other things, the explicit links between death, fertility and initiation rites (see Green, this volume; Sanders, this volume; and Kaspin, this volume). However, Kaspin, Power and Watts (both in this volume), demonstrate that while initiation rites involve aspects of gender complementarity, they also involve moments of symbolic reversal, when what is male is contained in the female, when women no longer bleed, and when women become hunters and men prey. These reversals continue to be of interest to anthropologists and especially given the fact that in day-to-day contexts women are forbidden contact with a man’s hunting implements, and hunters themselves must regulate sexual contact with women, and avoid menstruating women.[23]

There are a number of ways of understanding the evident contradictions and apparent reversals in gender symbolism. One is to speak of alternative models. In the case of the Aluund, De Boeck (1991: 40) defines a (male) political model of masculine dominance and female subordination as against a (female) body-linked model of feminine regenerative powers and male dependence. The co-existence of two such models is well supported by the data from many of the societies in the region. An approach based on multiple models of gender certainly moves us away from the idea that relations between the genders can be characterized in a single, monolithic fashion.[24] It also allows us to deal with such questions as whether evidence for gender complementarity or female powers is at odds with patrilineal and/or patriarchal ideologies by asserting that discrepant models co-exist, whilst acknowledging that in certain contexts one may dominate over the other.

However, what the symbolic systems of the region principally alert us to is that gender systems, far from being merely ideational, are in fact technological systems for engagement with the world. What initiation rituals — and indeed rituals of all kinds — do is to bring individuals into relation with others. They present an opportunity to understand one’s own experience and relation to the world through understanding that of others. This world is, of course, one in which the human body, its feelings, postures and orientations, extend into the natural and cosmic worlds through physical engagement and linguistic reflection. The body is both the starting point of one’s own experience and the origin of a set of culturally constructed imaginative domains (cf. Beidel- man 1993). Bodily experiences are thus tied to the imaginative and practical possibilities of being a gendered individual in a specific context. This means that while metaphoric associations can never be fixed or finalized or brought to a point of closure, neither are they completely free of dominant cultural understandings (H.L. Moore 1996).

But, the converse is equally true. Rituals present staged narrative sequences of symbols, opportunities for reflection and enlargement of understanding (cf. Beidelman 1997). Hitherto separate images, sounds, colours, emotions and aspects of life are brought into relation with each other in ways that reveal new connections and understandings. However, each individual experiences these connections for him or herself, and some no doubt reflect on them more than others. Experiences in ritual are powerful and over time, as Bloch (1992: 34) says, they may fade, but they do not disappear completely. Other aspects of life apparently unconnected to the ritual experience may thus take on new significance. Interpretation is a process, not a single event. African societies make this explicit in the way they link knowledge to age, in the way understandings of gender shift over the life course in response to a changing relation to knowledge (see Snyder, this volume; and Green, this volume). Language, like embodied praxis, has no single meaning. The words and songs of many initiation and fertility rites are apparently obscure, highly metaphorized, and not self-evident. It takes experience to understand them because exegesis is a matter of making connections.

Reflections on bodily experiences and their metaphoric transpositions — whether through practice or linguistic exegesis — enlarge one’s sense of agency and of self. It is one of the paradoxes of gender that, because it is relational, it is only possible to understand the gender of the other through reflection on one’s own gender, and to comprehend one’s own gender through engagement with that of the other. This should not surprise us, since this is anyway the paradox of subjectivity. However, what an emphasis on relations and connections alerts us to is a problem with the dualistic classification of gender employed in anthropological analysis. Dominant Western conceptions of gender emphasize the boundedness of gender categories, their difference from each other, and their hierarchical relation. In spite of recent theoretical work in anthropology that emphasizes the cross-cultural variation in gender constructs and categorizations, the implicit assumptions underlying Western concepts of gender are still evident in African ethnography in terms of the way some authors write about ‘women’s models’, ‘symbolic reversals’ and ‘women’s power’. The same implicit assumptions underpin questions about how to reconcile gender complementarity with patrilineal and/or patriarchal ideologies. The mistake here is to see gender categories in African societies as discrete and bounded, and as held together in a relationship of dualism such that one must always negate the other.

The problem, as Marilyn Strathern (1988: 64) identified, lies with the assumption of autonomy, with assuming that reflection on masculinity proceeds without any reference to femininity, that privileging agnation does not involve taking a position vis-a-vis uterine links and so on. The paradox is that many anthropologists, in asking for example whether evidence of female power is at odds with patrilineal ideology, are effectively reducing the representations of gender to actual women and men, even as their data informs them that the social and the symbolic are not mirror images of each other (Sanders, this volume). Gender symbolism in the contexts discussed in this book, and in the region as a whole, is better understood relationally, as something that manifests itself as division in unity, a fact that accounts, of course, both for the importance of the maternal body — encompassing two genders and two generations — and for the preoccupation with fertility.

Gender Performance and Gendered Agency

Anthropologists often refer to initiation rituals as events relating to the acquisition of gender identity, where the biological body is transformed into the socially gendered body. This is perhaps just another way of saying that initiation involves the imposition of the signifier onto the body, a fact that is often made concrete through the physical transformation of the body during initiation. In most societies in the region, male initiation is thought to make the boy dry and thereby to distinguish him from female moistness and fluidity. What is evinced is that the biological is somehow never enough; there is always a symbolic form to masculinity — and indeed to femininity — which must be assumed. The paradox this produces is that there is always an important, indeed essential, element to sexuality which is not human, in the straightforward sense that it is symbolic, and thus exceeds individual experience. It is for this reason that the symbolic categories ‘woman’ and ‘man’ cannot be reduced to women and men, and that the relation between the social and the symbolic is not isomorphic.

In many African societies, what exceeds the human dimension, and therefore human agency, is associated with the creative powers of the world, with the manifest fact that humans do not control the forces of the natural world. And yet, human society depends on maintaining a relation with that world, one that is productive. The symbolic and cosmological systems of the region represent this problem not just in terms of epistemology, but in terms of ontology. As Sherry Ortner has argued, the relationship between what humanity can achieve and a natural world that sets limits on those achievements must be a universal problem, even if the solutions to that problem vary historically and cross-culturally (Ortner 1996: 179). The ontological nature of the problem can be revealed through an examination of origin myths.

In many societies in the region, human society comes about through human agency which results in two things: the separation of humans from the sphere of the divine (see Broch-Due, this volume; and Kaare, this volume) and the emergence of reproductive human sexuality. Symbolic praxis and interpretation in relation to gender and fertility are thus philosophical reflections on the ontological nature of being, on the origins of gendered difference and human society itself. The severing of the human world from the sphere of the divine, often represented as a severing of a link between them (a strap or rope) provides the first of a series of tropes where one becomes two. Human sexuality arises in the same moment and is often represented as a process involving the killing or banishment of a mythical mother figure (e.g. Maxwell 1983: ch. 2; De Boeck 1994a: 276) and sometimes includes the theft by men from women of the origins of something representing culture or circumcision (e.g. De Boeck 1991; S.F. Moore 1976). What this theft signifies is the imposition of a socially reproductive sexuality onto a previously multiply constituted maternal figure who has the potential to reproduce on her own since she contains both sexes. De Boeck implies that this is repeated in the structural problematic of matriliny, where cross-cousin marriages (a male ego with his mother’s brother’s daughter) are sometimes preferred because they retain resources and offspring within the lineage, as well as recreating an autonomous maternal ‘body’ that is not dependent on outsiders for its regenerative capacities. This autonomy is encapsulated in the maternal uncle who becomes wife-giver and wife-receiver, the uterine life-source and the affinal link. However, such marriages may also be problematic because of the heightened possibility of sorcery between uterine kin, and because the uterine womb is enclosed and fails to exchange with others. Thus the Aluund refer to these marriages as ‘a dog eating its own placenta’ with all the connotations of incest, destruction and auto-consumption this implies (De Boeck 1994a: 263–4).

The management of fertility, like the management of a human world that is separate from the divine sphere yet subject to it, depends on creating gendered differences, revealing the division within unity, and productively supervising the interdependence of the female and the male. This is one reason why rituals and symbolic practice frequently involve the recombining of male and female attributes and categories. In so doing, they recall the ‘primordial unity’ both as a way of appropriating an aspect of the divine, of the forces beyond human agency, but also as a mechanism for recalling the origins of human society and of gender, the moment when difference is introduced into unity (see Kaare, this volume). For the secret of fertility, and indeed of reproduction, is to be able to make two out of one (gender), and then one out of two (generation) (Sanders 1998). In this sense, African societies are much like those Melanesian societies described by Strathern (1988) and others, where the problem of gender is revealed not as one of construction, but of decomposition (cf. Broch-Due 1993).

What kind of agency does ‘performing’gender involve?

What a reflection on the mythic and cosmological origins of gender reveals is that gender is the result of actions, not the origin of them. Current positions in anthropology and feminist theory assert that gender is not simply culturally constructed, but must be performed (Butler 1990; Sanders, this volume; Blystad, this volume; and Power and Watts, this volume). The notion of performance opens up gender, as a construct and as a lived relation, to historical change and cross-cultural variability. But, many writers assume — quite erroneously — that an emphasis on the performative aspects of gender implies a significant degree of voluntarism and free choice, in other words, that individuals can change their gender and make of it what they will. This interpretation is quite at odds with the approach of Judith Butler whose work is most often cited as the origin of performative theory in anthropology (cf. R.C. Morris 1995).

Butler’s theoretical work is inspired by psychoanalytic thinking and thus she does not suppose that one can choose to live one’s gender as one will because of the role of the unconscious and the importance of unconscious desires. More pertinently, in a psychoanalytic framework, the matrix of sexual difference must be prior to the gendered subject, since to come into subjectivity and language is to be subjected to the imperatives of sexual difference: ‘there is no “I” prior to its assumption of sex’ (Butler 1993: 99). What this means is that individuals cannot live their genders outside the symbolic framework of sexual difference, and that this is the case however subversive or alternative their constructions of gender might be. But this should not be taken to mean that individuals lack agency with regard to the way they live their genders. Butler argues that Western gender systems naturalize the masculine and the feminine as ideal constructions against which, or in terms of which, all individuals experience their bodily selves. In Butler’s terms masculine and feminine identifications cannot be fully exhaustive, in the sense that there will always be a gap between the symbolic constructions of female and male, and the experience of being a woman or a man. Since gender identities are never complete, never finished, they cannot be fully stable. They therefore require repetition and this for Butler explains the iterative nature of gender performance (Butler 1993: 187–8).

There are other aspects of Butler’s theory that cannot be explored here, but it is worth considering her work in relation to ritual performances and symbolic systems in the African context. Blystad (this volume) and Power and Watts (this volume) explore the connections and disconnections between Butler’s notion of performance and the way it has been used in anthropology (cf. V. Turner 1967; 1969; Tambiah 1979). What is evident is that the psychoanalytic emphasis on the gap between the experience of living a gendered identity and the symbolic constructions of gender is essential in any attempt to understand the basic paradox of the relation between the social and the symbolic. It explains why the categories ‘female’ and ‘male’ cannot be reduced to actual women and men (see Sanders, this volume). It is also potentially helpful to see ritual performances as instances of what Butler terms the ‘discourses of sex’,[25] as moments or events, where images and narratives about the nature of gendered identities, the relations between women and men, and the powerful nature of sexuality and fertility are being reiterated and repeated. What is important, however, in the context of the ethnography is that we do not see these reiterations as fixed, closed and determining. The metaphoric extension of gender symbolism across many domains of human experience, and its technological relation to a lived world of practice, means that gender discourses — as they are enacted in rituals — act as a reflection on the capacities of the genders and their interactions. Each individual makes his or her own interpretations based on this reflective performance, and through a process of creative imagination, rather than intellectual exegesis, arrives at an understanding of him or herself and others as gendered individuals. In this sense, practical engagement with gender symbolism in ritual and day-to-day contexts provides possibilities for agency both individual and collective. Groups of women who perform fertility rituals thus identify a space for their collective agency in terms of a gender symbolism that brings their experience of their bodies into close relation with the problem of how to manage the reproduction of the human, natural and cosmological worlds (see Snyder, this volume; Green, this volume; and Blystad, this volume). When African women and men perform operations on their genders a great deal more is at stake than simply gender.

References

Beattie, J. (1960) ‘On the Nyoro concept of Mahano’, African Studies, 19 (3): 145–50.

Beidelman, T.O. (1964) ‘Pig (guluwe): an essay on Ngulu sexual symbolism and ceremony’, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 20: 359–92.

Beidelman, T.O. (1966a) ‘Swazi royal ritual’, Africa, 36 (4): 373–405.

Beidelman, T.O. (1966b) ‘Utani: some Kaguru notions of death, sexuality and affinity’, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 22: 354–80.

Beidelman, T.O. (1971) ‘Some Kaguru notions about incest and other sexual prohibitions’, in R. Needham,, (ed.) Rethinking Kinship and Marriage (London: Tavistock).

Beidelman, T.O. (1972) ‘The filth of incest: a text and comments on Kaguru notions of sexuality, alimentation and aggression’, Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines, 12: 164–73.

Beidelman, T.O. (1973) ‘Kaguru symbolic classification’, in R. Needham (ed.) Right and Left: Essays on Dual Symbolic Classification (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Beidelman, T.O. (1980) ‘Women and men in two East African societies’, in I. Karp and C. Bird (eds) Explorations in African Systems of Thought (Bloomington: Indiana University Press).

Beidelman, T.O. (1993) Moral Imagination in Kaguru Modes of Thought (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press).

Beidelman, T.O. (1997) The Cool Knife: Imagery of Gender, Sexuality, and Moral Education in Kaguru Initiation Ritual (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press).

Bell, C. (1992) Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Berglund, A.-I. (1976) Zulu Thought-Patterns and Symbolism (London: Hurst and Company).

Bloch, M. (1992) Prey into Hunter: The Politics of Religious Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1990) The Logic of Practice (Cambridge: Polity).

Braidotti, R. (1991) Patterns of Dissonance (Cambridge: Polity).

Brain, J.L. (1977) ‘Sex, incest and death: initiation rites reconsidered’, Current Anthropology, 18 (2): 191–208.

Brain, J.L. (1978) ‘Symbolic rebirth: the mwali rite among the Luguru of eastern Tanzania’, Africa, 48 (2): 176–88.

Brain, J.L. (1983) ‘Basic concepts of life according to the Luguru of eastern Tanzania’, Ultimate Reality and Meaning, 6 (1): 4–21.

Broch-Due, V. (1993) ‘Making meaning out of matter: perceptions of sex, gender and bodies among the Turkana’, in V. Broch-Due, I. Rudie and T Bleie (eds) Carved FleshjCast Selves: Gendered Symbols and Social Practices (Oxford: Berg).

Burton, J.W. (1991) ‘Representations of the feminine in Nilotic cosmologies’, in A. Jacobson-Widding (ed.) Body and Space: Symbolic Models of Unity and Division in African Cosmology and Experience (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis).

Butler, J.P. (1990) Gender Trouble (London: Routledge).

Butler, J.P. (1993) Bodies that Matter (London: Routledge).