And the California University Archive: <harbor.klnpa.org/california/islandora/object/cali%3A944>

Henry S. Resnik

The Groovy Revolution

WOODSTOCK NATION: A Talk-Rock Album

by Abbie Hoffman

Vintage, paperback, 154 pp., $2.95

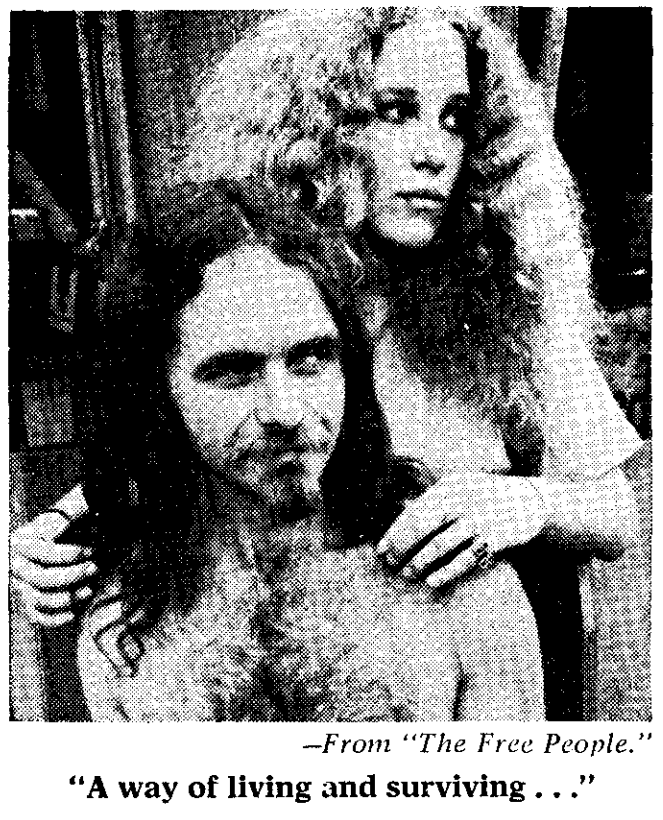

THE FREE PEOPLE

Photographs by Anders Holmquist, introduction by Peter Marin

Outerbridge & Dienstfrey/Dutton, $6.95, paperback $2.95

THE MAKING OF A COUNTER CULTURE

by Theodore Roszak

Doubleday, 303 pp., $7.95, paperback $1.95

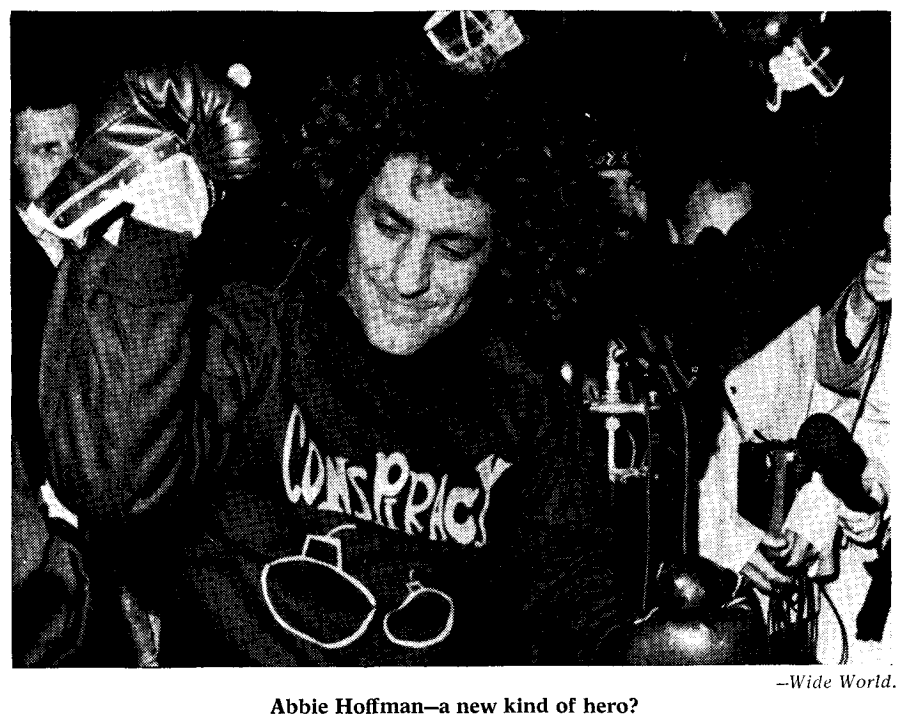

According to a biographical sketch in Woodstock Nation, Abbie Hoffman, who describes himself as a "revolutionist,” was thrown out of high school for hitting his English teacher. It seems that Abbie has always had a brilliant sense of theatrical irony—the class was probably discussing Silas Marner at the time. Abbie’s grammar still isn’t very good, but that hasn’t stopped him from writing books of his own. Woodstock Nation is his third.

Abbie Hoffman has been in an excellent position, in fact, to document, through books and articles, the “youth” movement so vividly represented by the Woodstock Music and Art Fair of August 1969, for he has been consistently at the center of the action during the last several years. He was involved in the "exorcism” of the Pentagon in October 1967, for example—an attempt to levitate the dread polyhedron three feet in the air by surrounding it with a magic number of chanting people, and thus rid it of its evil spirits. (The Pentagon stayed put.) Abbie lent his own special elan to the "Festival of Life” in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic Convention, which culminated in a police riot. And now he is one of the Chicago Eight, whose trial on charges of conspiracy he calls "the World Series of Injustice.” Wherever Abbie goes these days, there is magic— and theater and media and, if possible, dancing and sex and laughter. As Abbie himself often says, it’s a groovy revolution. He lives it all the time, even, as the following will show, during taped interviews.

H.R.: Who do you want to buy your book, anyway?

A.H.: I don’t want anybody to buy it— I want them to steal it.

H.R.: Okay, who do you want to steal your book?

A.H.: Seven-year-old kids, cause that's who I write for. They’re the vanguard of the revolution.

H.R.: But why write books at all?

A.H.: I don’t write books. Woodstock Nation is a talk-rock album—it's a record album. They're all songs and cuts ... I paint books . . . and sing them . . .

H.R.: Are seven-year-olds reading books? Are fifty-year-olds reading books?

A.H.: No, but they’re listening to albums, and since this is an album they’ll listen to it.

H.R.: Is this thing meant to be on a record?

A.H.: It's meant to be swum in, it's meant to be sung, it’s meant to be looked at. In Woodstock Nation there’s nobody who’s gonna read it from front to back unless you’re over seventy. You read it from blue to green to red and then you look at the written part and you look at the pictures and then you read the end to see how it ends and then you go and look at the list of song titles and then you look at the back—that’s how you do it; that’s how I wrote it.

Abbie wrote Woodstock Nation, the jacket copy proudly announces, "in longhand while lying upside down, stoned, on the floor of an unused office of the publisher.” Don’t underestimate Abbie; he could lie upside down. But don’t expect Woodstock Nation to herald a cultural revolution, either. The book is more of the "revolutionary” same: a slick, pseudo-media mix, with several different colored papers and myriad type faces and text-over-picture pages, and an apocryphal "last letter” in longhand from Che Guevara, and a film scenario in "sprocketed” frames. You will find every turned-on trick in the book in this volume (derived, no doubt, from the work of Quentin Fiore, Marshall McLuhan’s designer-collaborator), and by now you ought to be catching on to the fact that books like Woodstock Nation only aspire to being outasight — Quentin Fiore’s remarkable vision loses all its power when it becomes just another gimmick.

For the sake of those septuagenarians who are likely to read Woodstock Nation as if it were a book, at any rate, some explanation is in order. First of all, and most important, it gives relatively little attention to the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. Most of it is about Abbie Hoffman’s adventures as a revolutionary culture hero and enemy of the state—the United States of America, which he calls "Pig Nation.” And the record is impressive: Abbie was busted on one charge or another ten times in 1968 alone, and in the past five years or so he has been beaten and jailed so often that he could be a leading candidate for martyrdom if he didn’t make people laugh so much. On the surface, Abbie’s life is one fabulous put-on; at another level, there is a certain dreary routine to having a lawyer as a traveling companion. Abbie and his friends really do get hassled.

A.H.: All the money from the book goes to the trial—what else is there? Except a little for dope. I ain’t paid taxes in eight years; I don’t keep the money. I got ten grand advance, I got rid of that in less than five hours. That money went to, like, the John Sinclair defense fund, to try and get him out of prison—he got ten years for having two joints of marijuana, and it’s an important case. The rest went for the conspiracy trial in Chicago.

The main idea of the book, in short, is that Woodstock Nation was not just a music festival, but that it continues to be a way of living and surviving within the confines of Pig Nation. The citizens of Woodstock Nation are those who either think of themselves as cultural revolutionaries or have dropped out of the predominant culture—they are the mind-blown "hippies” and the radical activists; their numbers constantly grow.

Woodstock Nation did not really begin to dawn on Abbie as a political fact until "the rains came” on Saturday of that mad August weekend— then, suddenly, the 600 acres in White Lake, New York, were no longer the setting of a festival but a palpable enemy and threat. "Those that stayed,” Abbie writes, "are better for it all, including me. When you learn to survive in a hostile environment, be it the tear gas parks of Chicago or the mud slopes of Woodstock Nation, you learn a little more of the universal puzzle, you learn a little more about yourself . . .”

And it is here, when Abbie gets into a description of his experience at the festival (including a bad acid trip), that the monumental egotism of his writing glares, that his prejudices and his staged reality come sharply into focus. “Everything was so beautiful,” Abbie says earlier in the book, describing a visit to ultra-liberal Antioch College, "I was completely bored after three hours. The school lacked the energy that comes from struggle.” For the Abbie Hoffmans of America the absurd overkill of modern communications and the domination of technology has made only one kind of struggle really interesting: guerrilla theater, play-revolution, and ultimately the mock wars of the SDS Weathermen. All other struggles are a bore; action is the key, violence the reward. There are no writers in Woodstock Nation, Abbie tells us—only "poetwarriors.”

Abbie may be fine as a media clown, and his courage and idealism are admirable, but he cannot qualify as a poet in anyone’s nation. His strings of wordy sentences, spun out in a number of styles so blatantly conflicting that the over-all effect can only be called schizophrenic, amount to one huge, leaden rap. Woodstock Nation is, in fact, little more than clumsy propaganda for a "revolution” that Abbie takes with what seems to be great seriousness—the overthrow of the United States government. If such a revolution ever occurs, however, it will need better propaganda than Woodstock Nation.

There is some kind of awful yet unfathomable tragedy here, and Abbie may yet emerge a unique kind of hero that Orwell and Huxley never dreamed of. The purpose of the propaganda, after all, is to raise money for the Trial. And the Trial is one absurdity that Abbie Hoffman didn’t invent—he has been completely upstaged, in fact, by the United States Department of Justice. Nor, for that matter, is Vice President Agnew the mere fantasy of some diabolical cartoonist. Abbie’s book is ridiculous, but he and his comrades are the leading figures in a crisis that can only widen the schism dividing our country. We may have to defend him soon whether we take him seriously or not.

A.H.: I don’t think I have much to say. I think I have a lot to do and I think I’m pretty clever and I know how to do a lot of things, but I don’t think I have much to say. I don’t think there’s anything more to say. I think the ideas are already in.

H.R.: Do you have much to give?

A.H.: Yes, I have my life to give.

While Woodstock Nation does not satisfy either as poetry or as propaganda, the authors of The Free People have struck just the right note in presenting a genuinely poetic view of the counter-culture that Abbie Hoffman symbolizes. A collection of 154 black-and-white photographs of young rebels in their many natural habitats—Berkeley, the Lower East Side, Chicago, beaches, roads, woods, and music festivals (including Woodstock)—The Free People has a tender, loving quality that manages to avoid the usual slick simplemindedness of most journalism sympathetic to the subject. Even Peter Marin’s introduction, unabashedly lyrical in tone, has a solid earthiness quite foreign to the usual media treatment. Perhaps this is the book that Abbie Hoffman would have made if he didn’t find words such useless things while insisting on using them anyway. For if the old adage has any validity, The Free People is worth approximately 154,000 words. This book is probably more relevant, in fact, than any treatise on the counterculture to date; its pages are filled with vitality, beauty, and joy.

Though conventional in form and scarcely revolutionary, Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture is the most comprehensive and sophisticated analysis of what is happening among the young people of the Western world yet to emerge from the everincreasing flood of speculation. A frequent contributor to The Nation, a teacher of history at California State College, and a leader among the selfproclaimed radicals who maintain their ties to the academy, Roszak has an aggressive, clear-headed way of summing up phenomena that the media have made blurred or shapeless, or merely unreal, and putting the whole counter-culture in perspective. Roszak’s premise is that "the rivalry between young and adult in Western society during the current decade is uniquely critical" and that we should consider, first of all, why this situation exists and, secondly, where it is likely to lead.

Roszak has strong leanings towards the counter-culture himself; admirably, he lays his prejudices on the table: ". . . to make my own point of view quite clear from the outset, I believe that, despite their follies, these young centaurs deserve to win their encounter with the defending Apollos of our society. For the orthodox culture they confront is fatally and contagiously diseased.” What Roszak and the counterculture oppose is the absolute domination in the Western world, particularly in America, of science and technology —a “technocracy” that is subtly totalitarian, yet beyond conventional politics.

This predominating super-rationality and dependence on the authority of science is contrasted with the personal, mystical, anti-intellectual culture of the rock-drug-beat-“hippie”-Zen generation and the search for true liberation, humanity, and community. But the counter-culture is more than new art forms and philosophies, in Roszak’s view; it is also a political phenomenon, an “insistence on revolutionary change that must at last embrace psyche and society.” It is a movement that includes much of the New Left and the hippies as well, communes and free universities, music festivals and antiwar demonstrations. And, Roszak insists, the counter-culture is not so mindless as some technocrats might fear: evidence for this is “the strong influence upon the young of Eastern religion, with its heritage of gentle, tranquil, and thoroughly civilized contemplativeness.” Thus, the essence of the crucial early chapters, in which Roszak picks through the garbage-heap of information that the media have piled up in the last decade, and, more often than not, sets matters unequivocally straight.

A.H.: The reality is that no politician in this country, in Pig Nation, is going to endorse what happened [in Woodstock Nation] . . . The people that make up the military-industrial complex in this country, they’re shittin about the Woodstock Festival. They're uptight about it. They got three enemies—Nixon laid em out— they got the Vietcong, they got niggers, and they got drugs. Drugs don’t mean penicillin, it means us.

Roszak believes that the countercultural revolution is nearly inevitable, but he admits early in his discourse a number of serious obstacles. One of these is perhaps best illustrated by Abbie Hoffman himself: it is the idea, widely popularized in this country by Herbert Marcuse (whom Roszak contrasts in the book’s most thoughtful chapter with Norman O. Brown), that the liberal technocracy is infinitely capable of absorbing dissent—through the attention of the media and commerce, through the overwhelming idolization of youth, even through the modification of existing laws (the legalization of marijuana, for example, which is much more likely now than it seemed a decade ago). The Nixon-Agnew maneuvers are an exception, of course, but they could well be a merely unfortunate episode, a spasm in the unfolding of technocracy’s destiny. Nixon and Agnew lack vision, after all; they may have to jail and batter thousands of youthful dissenters before they finally realize that dope and rock and electricity are bigger than all of us.

Roszak is a passionate humanist, but in the light of such problems he can do no more than warn that the survival of the counter-culture is by no means certain. In a chapter on drugs, this warning is very near to despair:

What if the psychedelic boosters had their way then, and American society could get legally turned on? No doubt the marijuana trade would immediately be taken over by the major cigarette companies—which would doubtless be an improvement over leaving it in the hands of the Mafia . . . And surely the major pharmaceutical houses would move in on LSD just as readily. And what then? Would the revolution have been achieved? Would we suddenly find ourselves blessed with a society of love, gentleness, innocence, freedom? If that were so, what should we have to say about ourselves regarding the integrity of our organism? Should we not have to admit that the behavioral technicians have been right from the start? That we are, indeed, the bundle of electrochemical circuitry they tell us we are—and not persons at all who have it in our nature to achieve enlightenment by native ingenuity and a deal of hard growing.

Though The Making of a Counter Culture is often a defense, even a vivid example, of the counter-culture, as well as a reasoned explanation, Roszak never confronts the major problem of how that culture will elude the subtle forces that threaten it. The book has an air of having been written for those technocrats still capable of being swayed, as if Roszak were saying, "Here it is; try it!” Perhaps there is a future for revolution through seduction, in fact—it may well be the only way.

But Roszak is still in the academy; his style is still basically analytical and rational; and his attitude toward the counter-culture is, in the long run, profoundly ambivalent. Throughout the book there is a palpable straining, almost a duel, between rationality and passion, and it is a problem of which Roszak is painfully aware. Roszak does not even begin to believe, moreover, that the counter-culture has attained a healthy balance. In a chapter on the influence of Eastern culture, he is forced to admit that the entire beat-Zen movement is terribly superficial: “Perhaps what the young took Zen to be has little relationship to that venerable and elusive tradition; but what they readily adopted was a gentle and gay rejection of the positivistic and the compulsively cerebral.”

In the chapter on drugs, he sounds like a nagging grandmother: "Perhaps the drug experience bears significant fruit when rooted in the soil of a mature and cultivated mind. But the experience has, all of a sudden, been laid hold of by a generation of youngsters who are pathetically acultural and who often bring nothing to the experience but a vacuous yearning.... I think one must be prepared to take a very strong line on the matter and maintain that there are minds too small and too young for such psychic adventures. . .” Who, then, should be allowed to use drugs? Theodore Roszak and other dissenting academicians? Scientists in laboratories? Over-thirties?

What Roszak wants is an ideal combination of humanity and politics, tolerance and activism, and reason balanced by passion. As an example of this harmony he cites Paul Goodman, whom he lauds in a chapter that has the solid tin quality of public relations copy. Goodman has long been one of the prime intellectual movers of the counter-culture, of course, but when Roszak starts to preach rationality, one can easily envision the teenyboppers turning away in boredom. Roszak is clever and hip indeed, yet the counter-culture seems at times to be slipping away from his reasonable grasp as fast as he can describe it. The growth of the counter-culture has been toward irrationality, not away from it. Irrationality has become a last defense against the cold manipulativeness of the everyday world.

Finally Roszak takes the plunge himself, concluding with a lengthy plea on behalf of shamans as culture heroes (magical, imbued with ancient wisdom and ritual, even better than Goodman) that verges on silliness. Stylistically the book is most uneven, in fact, despite the validity and strength of its important insights, for it spans the spectrum from logical essay to impressionistic blur, from hard-headed critique to mass-magazine slickness. One suspects that Roszak is quite capable of blowing his mind entirely, that he might even be happier as a Dionysiac reveler than a dissenting academician.

But the threat of the turned-on concentration camp—the infinitely tolerant technocracy—cannot be taken lightly by those who understand it. The teenyboppers and the utterly mindless have not had the problem of choosing; for the rest of us, the balance gets more delicate every day.

Book Forum Responses

In his review of The Making of a Counter Culture, The Free People, and Woodstock Nation [SR, Dec. 13], Henry Resnik has written honest, open-minded analyses of books that concern themselves with a very complex, mixed-up, unsure, yet sincere group of people. However, regardless of the question of literary or social qualities, the books, albeit mostly inadvertently, reveal more than their writers intended.

All three books spotlight the great inadequacies of the mass of the “young rebels.” They seek to find in drugs and mysticism an anodyne for their frustrations with their own inabilities to understand themselves and their deficiencies. Examine closely and sympathetically the faces in the illustrations in The Free People and you weep for the pain of disillusionment which will be theirs when the drugs wear off and the “Woodstockian” festivals show themselves to be only establishment-promoted money-makers, and the "counter culture” only the seamy underside of the establishment itself.

Joseph Rosenzweig, Los Angeles, Calif.

I did not care at all for Henry S. Resnik’s sympathetic treatment of Abbie Hoffman and the New Left activists.

To describe these people as if they were unselfish idealists is a bit naive. Examples of their selfishness—and self-righteousness—are abundant.

For instance, there is their tendency to condone (and practice) stealing from anyone they choose to regard as part of the establishment. There is their tendency to ignore the desire for quiet on the part of people who are disturbed by their extraordinarily loud music.

My own experience indicates to me that it is impossible to carry on even a semi-rational political discussion with these people. If you happen to disagree with some of their opinions, you are likely to be called a fascist or a racist. They seriously assert that the United States is a fascist country—which is no less unreasonable than Robert Welch’s assertion that Dwight D. Eisenhower was a conscious agent of the Communist Party. If the New Left activists ever came into power in this country, they would be fully as ready to suppress dissent as the John Birch Society would be.

Theodore J. Kaczynski, Lombard, Ill.

Resnik’s review "The Groovy Revolution” was excellent.

I wish you would devote more space in your magazine to the rising American revolution of neo-primitivism. This is so very important and drastic and full of shattering implications for America and the Western world, that it seems a terrible oversight on the part of the media that they have not gone into it in depth.

Some questions: What is the role played in this by Negro consciousness? Is it beginning to dominate white Judaeo-Christian consciousness? Will it lead to a Hitler in this country? How many of the white youth have actually become "white Negroes,” to use Mailer’s terminology?

Horace Schwartz, San Francisco, Calif.

Abbie Hoffman is an idiot! He is a self-admitted drug addict, sadly in need of hospitalization! You thoughtlessly print his rantings, which downgrades our United States, a nation which but a few years back saved the world from the horrors of Hitlerism.

Granted, our nation has a lot of ills, but the Abbie Hoffmans will not cure them! Rather, he is a disrupting element in our society, and I regret that a fine magazine has given so much free publicity to such a low character.

Samuel Shapiro, Milton, Del.