Horace Kephart

The Book Of Camping And Woodcraft

A guidebook for those who travel in the wilderness

10. Dressing and Keeping Game and Fish

13. Forest Travel—Keeping a Course

14. Blazes—survey Lines—natural Signs of Direction

16. Emergency Foods—Living Off the Country

17. Edible Plants of the Wilderness

18. Axemanship—Qualities of Wood and Bark

19. Trophies, Buckskin, and Rawhide

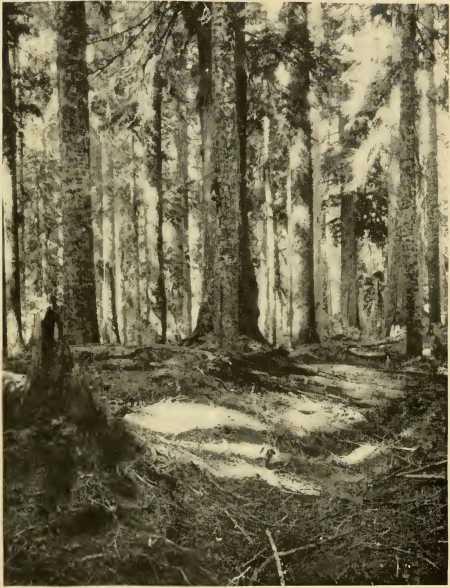

“This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlock,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of old, with voices sad and prophetic, Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.’’

Longfellow.

Front Matter

Title Page

THE BOOK OF

CAMPING AND WOODCRAFT

A GUIDEBOOK FOR THOSE WHO TRAVEL IN THE WILDERNESS

BY

Horace Kephart

NEW YORK

THE OUTING PUBLISHING COMPANY

1906

Publisher Details

Copyright, 1906, by

THE OUTING PUBLISHING COMPANY

1905, by FIELD AND STREAM

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London, England

Published September, 1906

THE OUTING PRESS

DEPOSIT, N. Y.

THE SHADE OF NESSMUK IN THE HAPPY HUNTING GROUND

Illustrations

| “The Forest Primeval" |

| In Still Waters . . |

| A Proud Moment . . . |

| Real Comfort in the Open . |

| Starting a Lean-to Shelter |

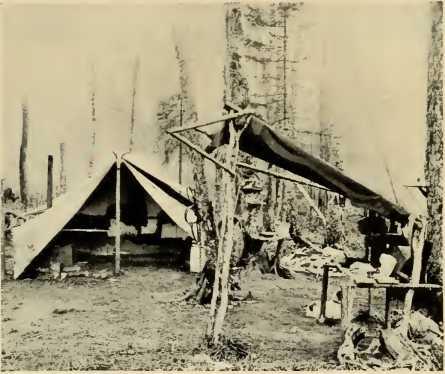

| The Fixed Camp . . . |

| A Good Day’s Shoot . . |

| An Ideal Camp-Fire . . |

| The Camp in Order . . |

| Just Starting Out . . |

| Crude, but Comfortable . |

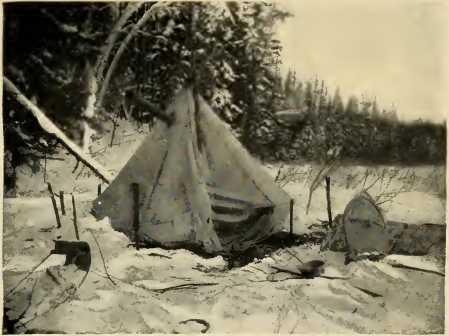

| Down the Snow-white Alleys |

| The Old, Old Story . . |

| But a Good Day’s Luck Lands Them . |

| A Stray Goose Wanders Near |

| Where Lurks the Lusty Trout |

Foreword

My one aim in writing this little book is to make it of practical service to those who seek rest or sport in the wilderness, or whose business calls them thither. I have treated the matter of outfitting in some detail, not because elaborate outfits are usually desirable, for they are not, but because in town there is so much to pick and choose from. Thereafter, the body of the book is mainly given up to such shifts and expedients as are learned in the wilderness itself, where we have nothing to choose from but the raw materials that lie around us.

As for camps situated within easy reach of towns or supply-posts, every one, I suppose, knows best how to gratify his own tastes in fitting them up, and prefers to use his own ingenuity rather than copy after others. Real woodcraft consists rather in knowing how to get along without the appliances of civilization than in adapting them to wildwood life. Such an art comes in play when we travel “light,” and especially in emergencies, when the equipment, or essential parts of it, have been destroyed. I am not advising anybody to travel with nothing but a gun and ammunition, a blanket, a frying-pan, and a tin cup; but it has been part of my object to show how the thing can be done, if necessary, without serious hardship.

Woodcraft may be defined as the art of getting along well in the wilderness by utilizing nature’s storehouse. When we say that Daniel Boone, for example, was a good woodsman, we mean that he could confidently enter an unmapped wilderness, with no outfit but what was carried by his horse, his canoe, or on his own back, and with the intention of a protracted stay; that he could find his way through the dense forest without man-made marks to guide him; that he knew the habits and properties of trees and plants, and the ways of fish and game; that he was a good trailer and a good shot; that he could dress game and cure peltry, cook wholesome meals over an open fire, build adequate shelter against wind and rain, and keep himself warm through the bitter nights of winter—in short, that he knew how to utilize the gifts of nature, and could bide comfortably in the wilderness without help from outside.

The literature of outdoor sport is getting us used to such correlative terms as plainscraft, mountaincraft, and even icecraft, snowcraft, and birdcraft. This sort of thing can be overdone; but we need a generic term to express the art, in general, of getting on well in wild regions, whether in forests, deserts, mountains, plains, tropics or arctics; and for this I would suggest the plain English compound wildcrajt.

In the following chapters I offer some suggestions on outfitting, making camps, dressing and keeping game and fish, camp cookery, forest travel, how to avoid getting lost, and what to do if one does get lost, living off the country, what the different species of trees are good for (from a camper’s viewpoint), backwoods handicrafts in wood, bark, skins and other raw materials, the treatment of wounds and other injuries, and some other branches of woodcraft that may be of service when one is far from shops and from hired help. I have little or nothing to say, here, about hunting, fishing, trailing, trapping, canoeing, snowshoeing, or the management of horses and pack-trains, because each of these is an art by itself, and we have good books on all of them save trailing.{1}

I have preferred to give full details, as far as this book goes. One’s health and comfort in the wilds very often depend upon close observance of just such details as breathless people would skip or scurry over. Moreover, since this is not a guidebook to any one particular region, I have tried to keep in mind a variety of conditions existing in different kinds of country, and have suggested alternative methods or materials, to be used according to circumstances.

In the school of the woods there is no graduation day. What would be good woodcraft in one region might be bad bungling in another. A Maine guide may scour all the forests of northeastern America, and feel quite at home in any of them; but put him in a Mississippi canebrake, and it is long odds that he would be, for a time,

Perplexed, bewildered, till he scarce doth know His right forefinger from his left big toe.

And a southern cane-cracker would be quite as much at sea if he were turned loose in a spruce forest in winter. But it would not take long for either of these men to “catch on” to the new conditions; for both are shifty, both are cool-headed, and both are keen observers. Any man may blunder once, when confronted by strange conditions; but none will repeat the error unless he be possessed by the notion that he has nothing new to learn.

As for book-learning, it is useful only to those who do not expect too much from it. No book can teach a man how to swing an axe or follow a trail. But there are some practical arts that it can teach, and, what is of more consequence, it can give a clear idea of general principles. It can also show how not to do a thing—and there is a good deal in that. Half of woodcraft, as of any other art, is in knowing what to avoid. That is the difference between a true knot and a granny knot, and the difference can be shown by a sketch as easily as with string in hand.

If any one should get the impression from these pages that camping out with a light outfit means little but a daily grind of camp chores, questionable meals, a hard bed, torment from insects, and a good chance of broken bones at the end, he will not have caught the spirit of my intent. It is not here my purpose to dwell on the charms of free life in a wild country; rather, taking all that for granted, I would point out some short-cuts, and offer a lift, here and there, over rough parts of the trail. No one need be told how to enjoy the smooth ones. Hence it is that I treat chiefly of difficulties, and how to overcome them.

This book had its origin in a series of articles, under a similar title, that I contributed, in 1904-6, to the magazine Field and Stream. The original chapters have been expanded, and new ones have been added, until there is here about double the matter that appeared in the parent series. I have also added two chapters previously published in Sports Afield.

Most of these pages were written in the wilderness, where there were abundant facilities for testing the value of suggestions that were outside my previous experience. In this connection I must acknowledge indebtedness to a scrap-book full of notes and clippings, the latter chiefly from old volumes of Forest and Stream and Shooting and Fishing, which was one of the most valued tomes in the rather select “library” that graced half a soap-box in one corner of my cabin.

I owe much, both to the spirit and the letter of that classic in the literature of outdoor life, the little book on Woodcraft by the late George R. Sears, who is best known by his Indian-given title of Nessmuk. To me, in a peculiar sense, it has been remedium utriusque fortune?; and it is but fitting that I should dedicate to the memory of its author this humble pendant to his work. Horace Kephart.

Dayton, Ohio

March, 1906.

1. Outfitting

“By St. Nicholas

I have a sudden passion for the wild wood— We should be free as air in the wild wood— What say you? Shall we go? Your hands, your hands!”

—Robin Hood.

IN some of our large cities there are professional outfitters to whom one can go and say: “So many of us wish to spend such a month in such a region, hunting and fishing: equip us.” The dealer will name a price; you pay it, and leave the rest to him. When the time comes he will have the outfit ready and packed. It will include everything needed for the trip, well selected and of the best materials. When your party reaches the jumping-off place it will be met by professional guides and packers, who will take you to the best hunting grounds and fishing waters, and will do all the hard work of paddling, packing over portages, making camp, chopping wood, cooking, and cleaning up, besides showing you where the game and fish are “ using,” and how to get them. In this way a party of city men who know nothing of woodcraft can spend a season in the woods very comfortably, though getting little practical knowledge of the wilderness. This is touring, not campaigning. It is expensive; but it may be worth the price to such as can afford it, and who like that sort of thing.

But, aside from the expense of this kind of camping, it seems to me that whoever takes to the woods and waters for recreation should learn how to shift for himself in an emergency. He may employ guides and a cook—all that; but the day of disaster may come, the outfit may be destroyed, or the city man may find himself some day alone, lost in the forest, and compelled to meet the forces of nature in a struggle for his life. Then it may go hard with him indeed if he be not only master of himself, but of that woodcraft that holds the key to nature’s storehouse. A camper should know for himself how to outfit, how to select and make a camp, how to wield an axe and make proper fires, how to cook, wash, mend, how to travel without losing his course, or what to do when he has lost it; how to trail, hunt, shoot, fish, dress game, manage boat or canoe, and how to extemporize such makeshifts as may be needed in wilderness faring. And he should know these things as he does the way to his mouth. Then is he truly a woodsman, sure to do promptly the right thing at the right time, whatever befalls. Such a man has an honest pride in his own resourcefulness, a sense of reserve force, a doughty self-reliance that is good to feel. His is the confidence of the lone sailorman, who whistles as he puts his tiny bark out to sea.

And there are many of us who, through some miscue of the Fates, are not rich enough to give carte blanche orders over the counter. We would like silk tents, air mattresses, fiber packing cases, and all that sort of thing; but we would soon “go broke” if we started in at that rate. I am saying nothing about guns, rods, reels, and such-like, because they are the things that every properly conducted sportsman goes broke on, anyway, as a matter of course. I am speaking only of such purchases as might be thought extravagant. And it is conceivable that some folks might call it extravagant to pay thirty-five dollars for a thing to sleep in when you lie out of doors on the ground from choice, or thirty dollars for pots and pans to cook with when you are “playing hobo,” as the unregenerate call our sylvan sport.

Nor can we deny that a man with an axe and a couple of dollars’ worth of cotton cloth can put up in two or three hours as good a woodland shelter as any mere democrat or republican needs between the ides of May and of November; and if he wants a portable tent he can generally buy very cheaply a second-hand army one that will meet all his requirements for several seasons. Tin or enameled ware, though not so smart nor so ingeniously nested as a special aluminum kit, will cook just as good meals, and will not burn one’s fingers and mouth so severely. Blankets we can take from home (though never the second time, perhaps); and a narrow bed-tick, filled with browse, or with grass or leaves where there is no browse, in combination with a rubber blanket or poncho, makes a better mattress than the Father of his Country had on many a weary night. A discarded business suit and a flannel shirt, easy shoes and a campaign hat, are quite as respectable in the eyes of woodland folk as a costume of loden or gabardine, and they do not set one up so prominently as a mark. Grocery boxes make good packing cases, and they have the advantage that they are not too good to be broken up for shelves and table in camp. As for duffel bags, few things are more satisfactory than seamless grain bags that you have coated with boiled linseed oil. Such a bag, by the way, is a good thing to produce now and then to show your friends how ingeniously economical you are. It helps out when you are caught slipping in through the back gate with a brand-new gun, when everybody knows that you already possess more guns than you can find legitimate use for.

If one begins, as he should, six months in advance, to plan and prepare for his next summer or fall vacation, he can, by gradual and surreptitious hoarding, get together a commendable camping equipment, and nobody will notice the outlay. The best way is to make many of the things yourself. This gives your pastime an air of thrift, and propitiates the Lares and Penates by keeping you home o’ nights. And there is a world of solid comfort in having everything fixed just to suit you. The only way to have it so is to do the work yourself. One can wear ready-made clothing, he can exist in ready-furnished rooms, but a readymade camping outfit is a delusion and a snare. It is sure to be loaded with gimcracks that you have no use for, and to lack something that you will be miserable without.

It is great fun, in the long winter evenings, to sort over your beloved duffel, to make and fit up the little boxes and hold-alls in which everything has its proper place, to contrive new wrinkles that nobody but yourself has the gigantic brain to conceive, to concoct mysterious dopes that fill the house with unsanctimonious smells, to fish around for materials, in odd corners where you have no business, and, generally, to set the female members of the household to buzzing around in curiosity, disapproval, and sundry other states of mind.

To be sure, even though a man rigs up his own outfit, he never gets it quite to suit him. Every season sees the downfall of some cherished scheme, the failure of some fond contrivance. Every winter sees you again fussing over your kit, altering this, substituting that, and flogging your wits with the same old problem of how to save weight and bulk without sacrifice of utility. All thoroughbred campers do this as regularly as the birds come back in spring, and their kind have been doing it since the world began. It is good for us. If some misguided genius should invent a camping equipment that nobody could find fault with, half our pleasure in life would be swept away.

There is something to be said in favor of individual outfits, every man going completely equipped and quite independent of the others. It is one of the delights of single-handed canoeing, whether you go alone or cruise in squadron, that every man is fixed to suit himself. Then if any one carries too much or too little, or cooks badly, or is too lazy to be neat, or lacks forethought in any way, he alone suffers the penalty; and this is but just. On the other hand, if one of the cruisers’ outfits comes to grief, the others can help him out, since all the eggs are not in one basket. I like to have a complete camping outfit of my own, just big enough for two men, so that I can dispense a modest hospitality to a chance acquaintance, or take with me a comrade who, through no fault of his own, turns up at the last moment; but I want this outfit to be so light and compact that I can easily handle it myself when I am alone.

Then I am always “fixed,” and always independent, come good or ill, blow high or low.

Still, it is the general rule among campers to have “company stores.” In so far as this means only those things that all use in common, such as tent, utensils, tools, and provisions, it is well enough; but it should be a point of honor with each and every man to carry for himself a complete kit of personal necessities, down to the least detail. As for company stores, everybody should bear a hand in collecting and packing them. To saddle this hard and thankless job on one man, merely because he is experienced and a willing worker, is selfish. Depend upon it, the fellow who “hasn’t time” to do his share of the work before starting will be the very one to shirk in camp.

The question of what to take on a trip resolves itself chiefly into a question of transportation. If the party can travel by wagon, and intends to go into fixed camp, then almost anything can be carried along—trunks, chests, big wall tents and poles, cots, mattresses, pots and pans galore, camp stove, kerosene, mackintoshes and rubber boots, plentiful changes of clothing, arsenals of weapons and ammunition, books, folding bath-tubs —what you will. Anybody can fit up a wagon-load of calamities, and hire a farmer to serve as porter. But does it pay ? I think not.

Be plain in the woods. In a far way you are emulating those grim heroes of the past who made the white man’s trails across this continent. Fancy Boone reclining on an air mattress, or Carson pottering over a sheet-iron stove! We seek the woods to escape civilization for a time, and all that suggests it. Let us sometimes broil our venison on a sharpened stick and serve it on a sheet of bark. It tastes better. It gets us closer to nature, and closer to those good old times when every American was considered “a man for a’ that” if he proved it in a manful way. And there is a pleasure in achieving creditable results by the simplest means. When you win your own way through the wilds with axe and rifle you win at the same time the imperturbability of a mind at ease with itself in any emergency by flood or field. Then you feel that you have red blood in your veins, and that it is good to be free and out of doors. It is one of the blessings of wilderness life that it shows us how few things we need in order to be perfectly happy.

Let me not be misunderstood as counseling anybody to “rough it” by sleeping on the bare ground and eating nothing but hardtack and bacon. Only a tenderfoot will parade a scorn of comfort and a taste for useless hardships. As Nessmuk says: “We do not go to the woods to rough it; we go to smoothe it—we get it rough enough in town. But let us live the simple, natural life in the woods, and leave all frills behind.”

An old campaigner is known by the simplicity and fitness of his equipment. He carries few impedimenta, but every article has been well tested and it is the best that his purse can afford. He has learned by hard experience how steep are the mountain trails and how tangled the undergrowth and down wood in the primitive forest. He has learned, too, how to fashion on the spot many substitutes for “ boughten” things that we consider necessary at home.

The art of going “light but right” is hard to learn. I never knew a camper who did not burden himself, at first, with a lot of kickshaws that he did not need in the woods; nor one who, if he learned anything, did not soon begin to weed them out; nor even a veteran who ever quite attained his own ideal of lightness and serviceability. Probably Nessmuk came as near to it as any one, after he got that famous ten-pound canoe. He said that his load, including canoe, knapsack, blanket-bag, extra clothing, hatchet, rod, and two days’ rations, “never exceeded twenty-six pounds; and I went prepared to camp out any and every night.” This, of course, was in summer.

In the days when game was plentiful and there were no closed seasons our frontiersmen thought nothing of making long expeditions into the unknown wilderness with no equipment but what they carried on their own persons, to wit: a blanket, rifle, ammunition, flint and steel, tomahawk, knife, an awl, a spare pair of moc- easins, perhaps, a small bag of jerked venison, and another of parched Indian corn, ground to a coarse meal, which they called “rockahominy” or “coal flour.” Their tutors in woodcraft often traveled lighter than this. An Indian runner would strip to his G-string and moccasins, roll up in his small blanket a pouch of rockahominy, and, armed only with a bow and arrows, he would perform journeys that no mammal but a wolf could equal. General Clark said that when he and Lewis, with their men, started afoot from the mouth of the Columbia River on their return trip across the continent, their total store of articles for barter with the Indians for horses and food could have been tied up in two handkerchiefs. But they were woodsmen, every inch of them.

Now it is not needful nor advisable for a camper in our time to suffer hardships from stinting his supplies. It is foolish to take insufficient bedding, or to rely upon a diet of pork, beans, and hardtack, in a country where game may be scarce. The knack is in striking a happy medium between too much luggage and too little. A pair of scales are good things to have at hand when one is making up his packs. Scales of another kind will then fall from his eyes. He will note how the little, unconsidered trifles mount up; how every bag and tin adds weight. Now let him imagine himself toiling uphill under an August sun, or forging through thickety woods, over rocks and roots and fallen trees, with all this stuff on his back. Again, let him think of a chill, wet night ahead, and of what he will really need to keep himself warm, dry, and well ballasted amidships. Balancing these two prospects one against the other, he cannot go far wrong in selecting his outfit.

In his charming book The Forest, Stewart Edward White has spoken of that amusing foible, common to us all, which compels even an experienced woodsman to lug along some pet trifle that he does not need, but which he would be miserable without. The more absurd this trinket is, the more he loves it. One of my camp-mates for five seasons carried in his “packer” a big chunk of rosin. When asked what it was for, he confessed: “Oh, I’m going to get a fellow to make me a turkey-call, some day, and this is to make it ‘turk. ’ ” Jew’s-harps, camp-stools, shaving-mugs, alarm-clocks, derringers that nobody could hit anything with, and other such trifles have been known to accompany very practical men who were otherwise in light marching order. If you have some such thing that you know you can’t sleep well without, stow it religiously in your kit. It is your “medicine,” your amulet against the spooks and bogies of the woods. It will dispel the koosy-oonek. (If you don’t know what that means, ask an Eskimo. He may tell you that it means sorcery, witchcraft—and so, no doubt, it does to the children of nature; but to us children of guile it is the spell of that imp who hides our pipes, steals our last match, and brings rain on the just when they want to go fishing.)

No two men have the same “medicine.” Mine is a porcelain teacup, minus the handle. It cost me much trouble to find one that would fit snugly inside the metal cup in which I brew my tea. Many’s the time it has all but slipped from my fingers and dropped upon a rock; many’s the gibe I have suffered for its dear sake. But I do love it. Hot indeed must be the sun, tangled the trail and weary the miles, before I forsake thee, O my frail, cool-lipped, but ardent teacup!

The joys and sorrows of camp life, and the proportion of each to the other, depend very much upon how one chooses his companions—granting that he has any choice in the matter at all. It may be noticed that old-timers are apt to be a bit distant when a novice betrays any eagerness to share in their pilgrimages. There is no churlishness in this; rather it is commendable caution. Not every good fellow in town makes a pleasant comrade in the woods. So it is that experienced campers are chary of admitting new members to their lodges. To be one of them you must be of the right stuff, ready to endure trial and privation without a murmur, and—what is harder for most men—to put up with petty inconveniences without grumbling.

For there is a seamy side to camp life, as to everything else. Even in the best of camps things do happen sometimes that are enough to make a saint swear silently through his teeth. But no one is fit for such life who cannot turn ordinary ill-luck into a joke, and bear downright calamity like a gentleman.

Yet there are other qualities in a good camp-mate that are rarer than fortitude and endurance. Chief of these is a love of nature for her own sake—not the “put on” kind that expresses itself in gushy sentimentalism, but that pure, intense, though ordinarily mute affection which finds pleasure in her companionship and needs none other. As Olive Shreiner says: “It is not he who praises nature, but he who lies continually on her breast and is satisfied, who is actually united to her.” Donald G. Mitchell once remarked that nobody should go to the country with the expectation of deriving much pleasure from it, as country, who has not a keen eye for the things of the country, for scenery, or for trees, or flowers, or some kind of culture; to which a New York editor replied that “Of this not one city man in a thousand has a particle in his composition.” The proportion of city men who do thoroughly enjoy the hardy sports and adventures of the wilderness is certainly much larger than those who could be entertained on a farm; but the elect of these, the ones who can find plenty to interest them in the woods when fishing and hunting fail, are not to be found on every street corner.

If your party is made up of men inexperienced in the woods, hire a guide, and, if there be more than three of you, take along a cook as well. Treat your guide as one of yourselves. A good one deserves such consideration; a poor one is not worth having at all. But if you cannot afford this expense, then leave the real wilderness out of account for the present; go to some pleasant woodland, within hail of civilization, and start an experimental camp, spending a good part of your time in learning how to wield an axe, how to build proper fires, how to cook good meals out of doors, and so forth. Be sure to get the privilege beforehand of cutting what wood you will need. It is worth paying some wood-geld that you may learn how to fell and hew. Here, with fair fishing and some small game hunting, you can have a jolly good time, and will be fitted for something more ambitious the next season.

In any case, be sure to get together a company of good-hearted, manly fellows, who will take things as they come, do their fair share of the camp chores, and agree to have no arguments before breakfast. There are plenty of such men, steel-true and blade-straight. Then will your trip be a lasting pleasure, to be lived over time and again in after years. There are no friendships like those that are made under canvas and in the open field.

2. The Sportsman’s Clothing

FOR ordinary camping trips an old business suit will do; but be sure that the buttons are securely sewn and that the cloth is not worn thin. It is somewhat embarrassing to come back home, as a friend of mine once did, with a staring legend of XXX FAMILY FLOUR emblazoned on the seat of his trousers. It may be well to take along a pair of overalls; they are workmanlike and win the respect of country folk. Men who dwell in the woods the year ’round are practical fellows who despise frills and ostentation. Many a tenderfoot has had to pay double prices for everything, and has been well laughed at in the bargain, because he sported a big bowie knife or a fake cowboy hat-band.

When one is preparing for a long, hard trip, it pays to give some heed to the clothing question. As a rule, the conventional hunting costumes of the shops are as unfit for the wilderness as they are for the gymnasium. They are designed for bird hunters, who carry heavy loads of shotgun shells, and little else, and who can tumble into a civilized bed at night. Canvas and corduroy are the materials most used. These cloths wear well, are generally of fairly good color for the purpose, are not easily soiled, and they do not collect burs; but this is about all the good that can be said of them. Canvas is too stiff for athletic movements, a poor protection against cold, and not so comfortable in any weather as wool. Corduroy wears like iron, but it is too heavy for hot days, not nearly so warm in cold weather as its weight of woolen goods, and it is notoriously heavy and hard to dry when it has been soaked through. Neither canvas nor corduroy are good absorbents of perspiration, nor do they let it evaporate freely. Both of them are too noisy for still-hunting. Even when they are not rasping against grass and underbush, there is a swishswash oi the trousers at every step. They are also likely to chafe the wearer.

A sportsman’s clothing should be strong, soft, light, warm for its weight, of inconspicuous color, and easy to dry after a wetting. It should be self-ventilating, and of such material as absorbs the moisture from the body. It should fit so as not to chafe, and should be roomy enough to give one’s limbs free play, permitting him to be active and agile.

The quality of one’s underwear is of more importance than his outer garments. It should be of pure, TT , soft wool throughout, regardless of the

Underwear. .. -n i i

&&&season. Cotton or silk are clammy and unhealthful when one perspires freely, as he is sure to do when living an active life out of doors, even in midwinter, and they chill the skin when one is drenched by a shower or when he rests after exertion. The air of the forest is often damp and chilly, especially at night and in the early morning hours. And you must expect to get a ducking now and then, and to be exposed to a keen wind when topping a ridge after a hard climb. At such times you are likely to catch a bad cold, or sow the seeds of rheumatism, if your underclothing is of any other material than wool. Thick underwear is not recommended, even for winter. It is better to have a spare undershirt of a size larger than what one commonly wears, and to double-up in cold weather or on frosty nights. Two thin shirts worn together are warmer than a thick one weighing as much as both. This is because there is a layer of warm air between them. The more air contained in a garment, other things being equal, the warmer it is. One soon realizes this when he spreads a blanket on the hard ground and lies down on it, thus pressing out the confined air. Drawers should be loose around the thighs and knees, but snug in the crotch. Remember that woolen goods will shrink in washing, unless the work is skilfully done; so do not get a snug fit at the start.

It is unwise t? carry more changes of underwear,

THE SPORTSMAN’S CLOTHING 13 handkerchiefs, etc., than one can comfortably get along with. They will all have to be washed, anyway, and so long as spare clean ones remain no man is going to bother about washing the others. This means an accumulation of soiled clothes, which is a nuisance of the first magnitude.

Overshirts should be loose at the neck, a size larger than one ordinarily wears, for they will surely shrink, o ,. and a tight collar is not to be tolerated.

The collars should be wide, if the shirts are to be used in cold weather, so that they can be turned up and tied around the neck. Gray is the best color, the dark blue of soldiers’ or firemen’s shirts being too conspicuous for hunters. It is well to sew two small pockets on the shirt just below where the collar-bone comes. These are to receive the watch and compass, which should fit snugly so as not to flop out when one stoops over. If the watch is carried in the fob pocket of the trousers it will be unhandy to get at, on account of the belt, and it is more likely to be injured when one wades out of his depth or gets a spill in shallow water.

A neckerchief should be worn, preferably of silk, because that is easy to wash and dry out. It protects K , the neck from sunburn, keeps it warm

&&&m cold weather, and is useful to tie over the hat and ears when the wind is high or the frost nips keenly. In case of cramps it is a good thing to tie over the stomach. A bright color, white or red especially, should be avoided if one expects to do any hunting.

A heavy coat is a nuisance in the woods. It would only be worn as a “come-and-go” garment when one Coats and trave^n^ to an^ from the wilderness, Tersevs and aroun(^ camP in the chill of the y ’ morning and evening. For the latter purpose a heavy jersey or sweater is much better, besides being more comfortable to sleep in, and easier to dry out. It should be of gray or light tan color, and all-wool of course. The objections to a sweater are that it is easily torn or picked out by brush, it attracts burs almost as a magnet does iron filings, and it soaks through in a smart shower. But if a coat of thin, very closely woven khaki, “duxbak,” or gabardine, large enough to wear over the sweater, is taken along, the perfection of comfort in all kinds of weather is attained. Such a coat is rain-proof, sheds burs, and keeps out not only the wind but the fine, dust-like snow which, on a windy day in winter, drives through the air, forces itself into every pore of a woolen fabric, and, melting from the heat of the body, soaks the garment through and through. With the above combination one is fixed for any kind of weather. On hot days his overshirt and trousers will be all the outer clothing he will want; if it threatens rain, he will add the coat; mornings and evenings, or on cold, dry days, he will substitute the sweater; and when it is both cold and windy, or cold and wet, all three will be worn. In any case the coat is merely considered as a thin, soft, rain-proof and windproof, but self-ventilating, skin, the heat-giving and sweat-absorbing part of the clothing being worn underneath. To combine the two in one garment would defeat the purpose, for it would be clumsy and would not dry out quickly. A free outlet for the moisture from the body, or a thick absorbent of it that can be taken off and dried out quickly, is a prime essential of health and comfort in all climates, and at no time more so than when the mercury stands far below zero.

For those who prefer a single heavy coat, rather than tolerate the “bunchy” feeling of several layers of different materials, I would recommend, for steady cold weather, a Mackinaw coat of the best obtainable quality, such as sheds a light rain; poor ones soak up water like a sponge.

Do not seek to keep your legs dry by wearing waterproofed material. Nothing but rubber or pantasote Trousers will s^e(^ water w^en you f°rge through wet underbrush, and they would wet you most uncomfortably by giving no vent to perspiration. Take your wetting, and dry out when you get back to camp. Strong, firmly woven woolen trousers or knickers are best for the woods in cold weather, and khaki or duxbak for warm weather.

The color of a woodsman’s clothing should be as near invisibility as possible—unless he ranges through Color a country infested with fools with guns, in which case a flaming red head-dress may be advisable. By the way, it is bad practice when one is calling turkeys to hide in the brush or behind a tree. Sit right out in the open. So long as you are motionless the turkey will not recognize you as a human being, whereas a man attracted by your calling will. The same rule holds good when one is on a deer stand, or “holding down a log” on a runway. As for inconspicuous clothing, take a hint from the deer and the rabbit, from the protective plumage of grouse and woodcock. Most shades of cloth used for men’s clothing are darker than they should be for hunting. What seems, near by, to be a light brown, for instance, looks quite dark in the woods. The light browns, greens, and drabs are indistinguishable from each other at a few rods’ distance. The color of withered fern is good; so are some of the lighter shades of covert cloth, such as top-coats are made of; also the yellowish-green khaki. White (except amid snow) and red are the most glaring colors in the woods. An ideal combination would be a mottle of alternate splotches of brown or drab and light gray, which, at a short distance in the woods, would blend with the tree trunks and would not look entirely opaque. Many men who think themselves properly dressed for stillhunting, and are so in the main, spoil it all by a flopping hat, a bright neckerchief, a glittering buckle, or rasping covering for their legs.

Leggings should be of woolen cloth, preferably of loden, which is waterproof. Those of canvas, pantasote, L . or leather are too noisy. When a man is

&&&in the woods to see what is going on in them he should move as quietly and make himself as unnoticeable as possible, whether he carries a gun or not. Leggings should not be fastened with buckles, hooks, or springs, but should lace through large eyelets or fasten with a puttee strap. Buckles and hooks catch in the grass and glitter in the sunlight, besides being hard to manage when covered with mud or ice; hooks are easily bent out of shape; springs are too stiff for pedestrians. Many recommend cloth puttees instead of leggings. A puttee of the kind I mean is a piece of stout woolen cloth four or five inches wide and fully nine feet long, to be wrapped spirally around the leg, starting from the ankle and winding up to the knee, overlapping an inch or two at a turn, and fastened at the top by tapes sewn on like horse-bandages. It is claimed that nothing else so well supports the veins of the legs in marching, that they are more comfortable and noiseless than ordinary leggings, and that they afford better protection against venomous snakes, as the serpent’s fangs are not so likely to penetrate the comparatively loose folds of cloth. Puttees should be specially woven with selvage edges on both sides, for if merely hemmed they will soon fray at the edges. It is not advisable to wear them in a thickety country.

Nothing in a woodsman’s clothing is of more importance than his foot dressing. The two unpardonable Shoes sins a s°ld*er are a rusty rifle and sore feet. So they should be regarded by us campers. The shoes and stockings should fit snugly, so as not to chafe from friction, but they should on no account be tight enough to bind. The shoes should be well broken in before starting.

High-topped hunting boots that lace up the leg are well enough for engineers and stockmen, but for hunters or others who travel in the wilderness, either afoot or afloat, they are much too heavy and clumsy. A pair of strong shoes with medium soles and bellows tongues, not over seven inches high, nor weighing an ounce more than two and a half pounds to the pair, will do for ordinary wear. They should be pliable both in soles and uppers. No one can walk well in boots with thick, stiff soles. Hob-nails are recommended only for fishermen and mountaineers. They should be of soft iron, as steel ones slip on the rocks. Their heads should be large and square, not cone-shaped. A few hob-nails along the edges of the soles and heels will suffice, those of most importance being the two on either side of the ball of the foot. If the middle of the

THE SPORTSMAN’S CLOTHING 17 sole is studded with them they are likely to hurt the feet. The leather should be well soaked before they are driven in.

It is not a bad plan to drive a few protruding nails in the heels and soles of one’s shoes, in a particular pattern, so that one can infallibly recognize his own footprints when back-trailing. This will also assist one’s companions if they should have occasion to search for him.

The best shoe-laces are made from rawhide beltlacing, cut in strips and hardened at the ends by slightly roasting them in the fire.

Shoes to be worn in cool weather may well be waterproofed, but for warm weather they should not, for w , waterproofed leather heats the feet; and in a Leather SO’ wa^’ ru^^er so^es- If one ing ea er. much marching to do he had better take his chances of getting his feet wet now and then than to keep them overheated all the time, and consequently tender.

An excellent Norwegian recipe for waterproofing leather is this:

Boil together two parts pine tar and three parts cod-liver oil. Soak the leather in the hot mixture, rubbing in while hot. It will make boots waterproof, and will keep them soft for months, in spite of repeated wettings.

For canoeing, still-hunting, and for long marches in the dry season, as well as for use around camp, wear M . either thick moccasins or light moccasin-shoes (the latter should not weigh over one and a half pounds to the pair).

The importance of going lightly shod when one is to do much tramping is not always appreciated. Let me show what it means. Suppose that a man in fair training can carry on his back a weight of forty pounds for ten miles on good roads, without excessive fatigue. Now shift that load from his back and fasten half of it on each foot—how far will he go ? You see the difference between carrying on your back and lifting with your feet. Very well; a pair of hunting shoes of conventional store pattern weighs about three pounds; a pair of moose-hide moccasins weighs eleven ounces. In ten miles there are 21,120 average paces. It follows that a ten-mile tramp in the big shoes means lifting some eight tons more footgear than if one wore moccasins. Nor is that all. The moccasins are soft and pliable as gloves; the shoes are stiff, clumsy, and likely to blister the feet.

If your feet are too tender, at first, for moccasins, add insoles of birch bark or the dried inner bark of red cedar. After a few days the feet will toughen, the tendons will learn to do their proper work without crutches, and you will be able to travel farther, faster, more noiselessly, and with less exertion, than in any kind of boots or shoes. This, too, in rough country. I have often gone tenderfooted from a year’s office work and have traveled in moccasins for weeks, over flinty Ozark hills, through canebrakes, through cypress swamps where the sharp little immature “knees” are hidden under the needles, over unballasted railroad tracks at night, and in other rough places, and enjoyed nothing more than the lightness and ease of my footwear. After one’s feet have become accustomed to this most rational of all covering they become almost like hands, feeling their way, and avoiding obstacles as though gifted with a special sense. They can bend freely. One can climb in moccasins as in nothing else. So long as they are dry, he can cross narrow logs like a cat, and pass in safety along treacherous slopes where thick-soled shoes might bring him swiftly to grief. Moccasined feet feel the dry sticks underneath, and glide softly over the telltales without cracking them. They do not stick fast in mud. One can swim with them as if he were barefoot. It is rarely indeed that one hears of a man spraining his ankle when wearing the Indian footgear.

Moccasins should be of moose-hide, or, better still, of caribou. Elk-hide is the next choice. Deerskin is too thin, hard on the feet for that reason, and soon wears out. The hide should be Indian-tanned, and “honest Injun” at that—that is to say, not tanned with bark or chemicals, in which case (unless of caribouhide) they would shrink and dry hard after a wetting, but made of the raw hide, its fibers thoroughly broken

&&&up by a plentiful expenditure of elbow-grease, the skin softened by rubbing into it the brains of the animal, and then smoked, so that it will dry without shrinking and can be made as pliable as before by a little rubbing in the hands. Moccasins to be used in a prickly-pear or cactus country must be soled with rawhide.

Ordinary moccasins, tanned by the above process (which properly is not tanning at all), are only pleasant to wear in dry weather. But they are always a great comfort in a canoe or around camp, and are almost indispensable for still-hunting or snow-shoeing. They weigh so little, take up so little room in the pack, and are so delightfully easy on the feet, that a pair should be in every camper’s outfit. At night they are the best foot-warmers that one could wish, and they will be appreciated when one must get up and move about outside the tent.

In a mountainous region that is heavily timbered, moccasins are too slippery for use after the leaves fall.

Oil-tanned shoe-packs are better than moccasins for wet weather. When kept well greased with tallow (oil “ Packs ” and so^cns ^lcm too much) they are water- “ qh k » proof, and much more comfortable than rubber shoes. ‘‘ Shanks ’’ made by stripping the hide from the hind legs of moose, caribou, or elk, without splitting it, using the bend of the hock for the heel of the boot, and sewing up the toe part, when properly tanned are impervious to water and snow, and are beyond comparison the warmest and driest of footwear for high latitudes. Caribou or reindeer skin makes the best. It is remarkably tough, moderately elastic, warmer for its weight than any other material, more impervious to wind, drier than any other kind of leather, and it has the singular property of tightening when wet, or at least not stretching like all other skins. Shanks are sometimes made of green hide, but only for temporary purposes, as they soon wear out; when tanned they are very durable. The hide should be tanned with bark, as alum destroys its good qualities. The hair should be left on and worn outside, the shanks being carefully dried away from the fire, after using, or the hair will drop out.

Never hang your moccasins before the fire to dry; they would shrink too small for your feet, and become almost as stiff and hard as horn. Scrape off as much moisture as you can, stuff them full of dry grass or some other elastic, absorbent substance, and hang them in a current of air where they can dry slowly. Then rub them soft.

Rubber boots I never wear, save when working in the marshes, or for a short time in muddy, sloppy

Wading Boots.

&&&weather around a cabin or fixed camp. I would rather get wet from water than from perspiration. Canvas wading

&&&shoes, with eyelets at the toes to let the water run out, or old shoes with slits cut in them (not wide enough to let in gravel), are good to use when fishing.

A mackintosh or other long-tailed coat is as out of place in the woods as an umbrella on shipboard. An

Waterproof Clothing.

&&&oilskin slicker, topped off by a sou’wester, may be all right in a boat or over decoys, on horseback, or when driving;

&&&but anything of this sort is too heavy, too draggling, too hot, too awkward to shoot from, when one is afoot;

&&&and the brush soon tears it. For a woodsman an army poncho is better, either of rubber or (much more durable) of pantasote. It makes a good ground-sheet at night. The infantry size is 45x72 inches, the cavalry 72x84, the latter being large enough to serve as a shelter, but heavy to tote around. A waterproof poncho weighing only one pound can be made from thin enameled cloth, at a cost of about forty cents; but it is easily torn.

The best head-gear for general wear is a Stetson hat of army pattern. It stands rain, and keeps its shape under a good deal of abuse. The natural smoke-color of the felt is best.

The brim should be wide enough to keep rain and snow from falling down the back of one’s neck. Remove the leather sweat-band and substitute one of flannel, which is far more comfortable in all weathers, and sticks well to one’s head, so that the hat is not easily knocked off by wind or boughs.

In the fall or winter take also a knitted wool cap

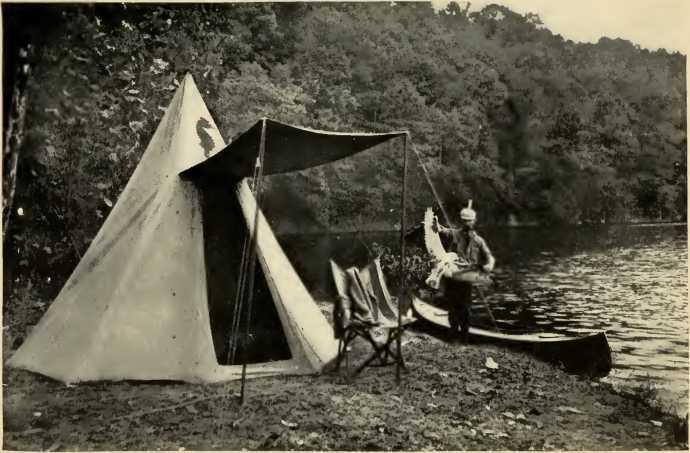

In Still Waters

&&&that can be drawn down over the ears. It makes a good nightcap, which you will need on cold nights when sleeping in the open or under canvas.

For very hot weather a pith helmet with yellow lining is better than a hat.

If a head-net is taken, get one long enough to button under the coat, and dye the bobbinet black, for black is easier to see through than white or colored stuff. A head-net is somewhat of a nuisance, particularly when you want to smoke or spit; but in some localities, especially in the far north, it is almost indispensable at times on account of the thick clouds of mosquitoes. It is also useful in hunting wild bees.

A pair of buckskin gloves or gauntlets, pliable and not too thick, should be carried by any man who goes Gloves fresh from the office to the woods.

Rowing and chopping will quickly blister tender hands. Woolen gloves, as a protection from cold, are too easily wet through, and then are little better than none. But in very cold weather it is best to wear woolen ones under loose fur mittens, the latter being hung from the neck by strings.

The belt, if one is worn, should be loose. A belt drawn tightly enough to hold up much weight may gejtg cause rupture. Suspenders should be

&&&worn if the trousers are heavy. A cartridge belt should be worn cowboy fashion, sagging well down on the hips. Woven ones are more comfortable than leather, and do not cause verdigris to form on the cartridges as any leather belt will do, no matter how well it may be greased. Loops closed at the bottom collect dirt and grit. A leather belt with loops long enough to cover the bullets is best for a sandy region. If there is a big, shiny buckle, wear it to the rear; for sunlight glittering on it will scare away game.

When traveling in foreign lands, where the climate is different from our own, dress after the custom of the country. In nearly all wild regions there are civilized residents who can give the desired pointers.

3. Personal Kits

TT is hard to generalize on outfits, because men’s re* quirements vary, according to the country traversed, the season of the year, and personal tastes. Let no one imagine that he must lay in everything mentioned here, for any one trip.

One’s health and comfort in camp depend very much upon what kind of bed he has. In nothing does a ten- The Prime derfoot show off more discreditably than

w ., in his disregard of the essentials of a

J ’ good night’s rest. He comes into camp after a hard day’s tramp, sweating and tired, eats heartily, and then throws himself down in his blanket on the bare ground. For a time he rests in supreme ease, drowsily satisfied that this is the proper way to show that he can “rough it,” and that no hardships of the field can daunt his spirit. Presently, as his eyes grow heavy and he cuddles up for the night, he discovers that a sharp stone is boring into his flesh. He shifts about, and rolls upon a sharper stub or projecting root. Cursing a little, he arises and clears the ground of his tormentors. Lying down again, he drops off peacefully and is soon snoring. An hour passes, and he rolls over on the other side; a half hour, and he rolls back again into his former position; ten minutes, and he rolls again; then he tosses, fidgets, groans, wakes up, and finds that his hips and shoulders ache from serving as piers for the arches of his back and sides.

He gets up, muttering, scoops out hollows to receive the projecting portions of his frame, and again lies down. An hour later he reawakens, this time with shivering flesh and teeth a-chatter. How cold the 22

&&&ground is! The blanket over him is sufficient cover, but the same thickness beneath, compacted by his weight and in contact with the cold earth, is not half enough to keep out the bone-searching chill that comes up from the damp ground. This will never do. Pneumonia or rheumatism will follow. He arises, this time for good, passes a wretched night before the fire, and dawn finds him a haggard, worn-out type of misery, disgusted with camp life and eager to hit the back trail for home.

The moral is plain. This sort of roughing it is bad enough when one is compelled to submit to it. It kills twice as many soldiers as bullets do. When it is endured merely to show off one’s fancied toughness and hardihood it is rank folly. Even the dumb beasts know better, and they are particular about making their beds.

This matter of a good portable bed is the most serious problem in outfitting. A man can stand almost any hardship by day, and be none the worse for it, provided he gets a comfortable night’s rest; but without sound sleep he will soon go to pieces, no matter how gritty he may be.

For camping in summer or in early autumn, when means of transportation permit it, the best camp bed Cotg is a compactly folding cot, such as is

&&&specially made for military and sportsmen’s use; it weighs but sixteen pounds, and folds into a package 3 ft. x 4 in. x 5 in. A thin mattress of cotton or curled hair, or a doubled comforter as a substitute, is of even more importance on such a cot than the blanket that one covers himself with; for to sleep on taut canvas with nothing but a blanket under you is little more restful than lying on a board floor, and, if the nights are chilly, you will suffer from cold underneath. A cot and mattress, when you can carry them, save much time and work in bed-making and tent-trenching, and they keep the bedding clean, besides affording a comfortable lounge by day. A cot, however, is not at all comfortable in real cold weather, because, no matter how much bedding you have, you cannot keep it tucked in snugly around you, owing to the narrowness of the cot.

But suppose you are traveling light, perforce—what then ? Cot or no cot, the first requisite is a mattress of __ xx some sort, either ready-made or extem-

&&&ponzed on the spot. An air mattress is luxurious, but expensive, unreliable and cold in zero weather, and useless if punctured; but for summer camping, especially by us middle-aged or older fellows, who may have grown a trifle stiff and rheumatic from many a night on the bare, damp ground, it is a perquisite fairly won. Cork mattresses are favored by such canoeists as are not obliged to make long portages, being easily dried, and making good life-preservers. But they are rather bulky, and none too soft nor warm. Down quilts, though the warmest covering for their weight, are not warm underneath one’s body, as the pressure squeezes out their confined air. A canvas stretcher swung on long poles makes a good spring bed for hot weather; but if the nights are chilly there will be a cold draught along the floor (always the coldest part of a tent) which will soon chill one to the bone. If it be made double, forming a bag open at both ends that can be stuffed with grass or browse, it is improved; but any such contrivance takes considerable time to rig up properly, and the tent may not be long enough for the poles and their supports.

Nearly every book and magazine article on camping that I have read extols a bed of balsam browse shingled p P , in between a pair of logs. Balsam is rowse e s. gOoj. unfortunately, throughout the greater part of our country there is no balsam, nor even hemlock, nor spruce, nor any other kind of tree that affords even passable browse, in the fall, for this sort of bed.

For all-round service, in all sorts of countries, I prefer to carry with me a narrow bag of 10-cent bed ticking, 2^ feet wide and 6 feet long, to be filled with grass, leaves, or such other soft stuff as one may find on the camping ground. Such a bag weighs but 1J pounds, takes up little room when empty, is useful in packing, and a man can make a good mattress with it —one that will not spread out nor pack hard—in less than half the time it would take to shingle browse or rig up a stretcher. If wet stuff must be used for filling, spread the rubber blanket or poncho on top of the bag, and all will be well.

Blankets should be all-wool, and firmly woven, so as to shed dirt. California blankets are best, then

, . Hudson Bay or Mackinaw. The qual

&&&ity of our regular army blanket is excellent for the purpose, but do not get one that is narrow and folds at the end—you cannot roll up in it so snugly as if it were almost square. For extremely cold climates nothing equals a robe (not bag) of caribouhide with the hair on, as it is warmer and drier for its bulk and weight than any other material.

A separate pillow-bag, to be filled in camp like the bed-tick, is another soft thing that no experienced woodsman despises. For horsemen a saddle is supposed to be all the pillow needed; but it is nothing of the sort—a mound of earth is better.

Sleeping-bags have their good and bad qualities. Those which open only part way down are abomina- . tions, hard to get into and out of, and

P s hard to air properly and to dry. No matter how waterproof the outside cover may be, the blanket or fur lining will surely get damp, both from the air and from the exudations of the sleeper. The only sleeping-bags worth considering are those that can easily be opened and spread wide in the sunlight or before the fire, which should be done every morning. Even so, they cannot so quickly be aired and dried as blankets, unless the lining is entirely removable from the cover.

An explorer of wide experience both in the arctic and antarctic regions gives his opinion of sleeping-bags as follows:

For the first two or three days the sleeping-bag is a thing of comfort and a joy, and then it gradually gets worse and worse. The perspiration that collects in the bag during the night freezes immediately we leave it in the morning, and there is not sufficient heat from the sun to dry the bag when it is packed on the sledge. The bag, therefore, has to be thawed out by our bodies each night, so that it gradually becomes heavy with moisture, and more and more uninviting.—Lieut. Armitage, Two Years in the Antarctic.

It is snug, for a while, to be laced up in a bag, but not so snug when you roll over and find that some aperture at the top is letting a stream of cold air run down your spine, and that your weight and cooped-up- ness prevent you from readjusting the bag to your comfort. Likewise a sleeping-bag may be an unpleasant trap to be in when a squall springs up suddenly at night, or the tent catches fire.

I think that one is more likely to catch cold when emerging from a stuffy sleeping-bag into the cold air than if he had slept between loose blankets. A waterproof cover without any opening except where your nose sticks out is no more wholesome to sleep in than a rubber boot is wholesome for one’s foot. Nor is such a cover of much practical advantage, except underneath. The notion that it is any substitute for a roof overhead, on a rainy night, is a delusion.

Blankets can be wrapped around one more snugly, they do not condense moisture inside, and they can be thrown open instantly in case of alarm. In blankets you can sleep double in cold weather. Taking it all in all, I choose the separate bed-tick, pillow-bag, poncho, and blanket, rather than the same bulk and weight of any kind of sleeping-bag that I have so far experimented with. There may be better bags that I have not tried.

There is a form of camp bed known as a “carry-all” that deserves mention. It may be described as a bag

The

“ Carry-All.”

&&&open at both ends, with a flap on each side to cover the sleeper, and shorter flaps for feet and head, the whole being made of stout waterproofed canvas, and fitted with straps and buckles. Two large pockets at the head end contain spare clothing, and thus form a pillow for the night. The blankets, and other articles, can be rolled up within this cover, and the whole affair is then quickly buckled up, making a convenient pack, rainproof all around. The bag part of the affair can be stuffed full of browse, grass, or such other bedding as the country affords; and poles can be run through it at either side, and across the ends, so as to form either a spring-bed or a hammock. The chief objection to this contrivance, as now made, is its weight, which is 10 pounds. A cotton bed-tick, pillow-bag, silk sheltercloth, and poncho of pantasote sheeting, together weigh only 6 pounds, and each of them is good for something by itself when you are on the trail. The addition of a good, heavy blanket brings the weight up to about 15 pounds, for one man’s bedding, packcloth, and shelter—and these are plenty for anybody until frosts set in.

SThe shelter-cloth here referred to is of waterproofed loon silk, 7x8 feet, with eyelets (small steel rings - pi ft, sewed on by hand, not mere metal eye- e er ° lets) around the edges at intervals of about a foot, the contrivance weighing from 2 to 2| pounds^ This makes a small roll on top of one’s knapsack, or serves as a pack-cloth. It makes a good shelter or windbreak when one takes a side trip of a day or two from camp. Such side trips are generally the pleasantest and most profitable days in my experience. One sees more, learns more, and gets closer to nature when he is far off in the woods by himself than when he is around camp or hunting with companions.

To the same end it is well to take with you an individual cooking kit. This is not formidable. A frying- T j. ., . pan and a large tin cup, with the sheath- Individual r ° *

„ . . knife, are sufficient; though a quart

Cooking Kits. .. . . i , ’. ? * j f

&&&pail is a useful addition. Instead ot a frying-pan, for such trips, I like a U. S. Army mess kit, procured from a dealer in second-hand military equipments for twenty cents. It consists of two oval dishes of tinned steel which fit together and form a meat can 8 inches long, 6} inches wide, and 1| inches deep, weighing f of a pound. In this a ration of meat is carried on the march. When the dishes are separated the lower one serves as a plate, and is deep enough for soup. The upper dish has a folding handle which locks the two together, and it makes a fair frying-pan.

The Preston individual cooking kit, made of aluminum, is commendable for those who care to spend more money on such a thing. It can be procured from army outfitters.

On the subject of hunting knives I am tempted to

&&&be diffuse.

SheathKnives.

In my green and callow days (perhaps not yet over) I tried nearly everything in the knife line from a shoemaker’s skiver to a machete, and I had knives

&&&made to order. The conventional hunting knife is, or was until quite recently, of the familiar dime-novel pattern invented by Colonel Bowie. Such a knife is too thick and clumsy to whittle with, much too thick for a good skinning knife, and too sharply pointed to cook and eat with. It is always tempered too hard. When put to the rough service for which it is supposed to be intended, as in cutting through the ossified false ribs of an old buck, it is an even bet that out will come a nick as big as a saw-tooth—and Sheridan forty miles from a grindstone! Such a knife is shaped expressly for stabbing, which is about the very last thing that a woodsman ever has occasion to do, our lamented grandmothers to the contrary notwithstanding.

A camper has use for a common-sense sheath-knife, sometimes for dressing big game, but oftener for such homely work as cutting sticks, slicing bacon, and frying “spuds.” For such purposes a rather thin, broad- pointed blade is required, and it need not be over four or five inches long. Nothing is gained by a longer blade, and it would be in one’s way every time he sat down. Such a knife, bearing the marks of hard usage, lies before me. Its blade and handle are each 4| inches long, the blade being 1 inch wide, J inch thick on the back, broad pointed, and continued through the handle as a hasp and riveted to it. It is tempered hard enough to cut green hardwood sticks, but soft enough so that when it strikes a knot or bone it will, if anything, turn rather than nick; then a whetstone soon puts it in order. The Abyssinians have a saying, “If a sword bends, we can straighten it; but if it breaks, who can mend it ? ” So with a knife or hatchet. The handle of this knife is of oval cross-section, long enough to give a good grip for the whole hand, and with no sharp edges to blister one’s hand. It has a | inch knob behind the cutting edge as a guard, but there is no guard on the back, for it would be useless and in the way. The handle is of light but hard wood, J inch thick at the butt and tapering to A inch forward, so as to enter the sheath easily and grip it tightly. If it were heavy it would make the knife drop out when I stooped over. The sheath has a slit frog binding tightly on the belt, and keeping the knife well up on my side. This knife weighs only 4 ounces. It was made by a country blacksmith, and is one of the homeliest things I ever saw; but it has outlived in my affections the score of other knives that I have used in competition with it, and has done more work than all of them put together.

For ordinary whittling a good jackknife is needed. It should have one heavy blade 2| or 3 inches long, y , , . tempered hard enough for seasoned J ’ hickory, but thick enough not to nick

&&&or snap off; also a small, thin blade that will take a keen edge and keep it. The best pattern is an “easy- opener,” which has part of the handle cut away so that one can open it without using his thumb-nail, which may be wet and soft, or brittle from cold. There should be no sharp edges on the handle, which is preferably of ebony.

A woodsman should carry a hatchet, and he should be as critical in selecting it as in buying a gun. The n , notion that a heavy hunting knife can

&&&do the work of a hatchet is a delusion. When it comes to cleaving carcasses, chopping kindling, blazing thick-barked trees, driving tent pegs or trap stakes, and keeping up a bivouac fire, the knife never was made that will compare with a good tomahawk. The common hatchets of the hardware stores are unfit for a woodsman’s use. They have broad, thin blades with beveled edge, and they are generally made of poor, brittle stuff. A camper’s hatchet should have the edge and temper of a good axe. It must be light enough to carry in one’s belt or knapsack, yet it should bite deep in timber. There is but one way to get this seemingly contradictory result, and that is to make the blade long and narrow, like an Indian tomahawk, or like a Nessmuk double-blade, thus putting the weight where it will do the most good. (,When there is a full-grown axe in camp I carry a tomahawk of 12-ounce head. The handle is just a foot long. Its grip is wound with waxed twine to give a good hold when one’s hand is wet. This little tool has been my mainstay on several bitter nights when I was lost in the forest, or in a canebrake, and without it I would have fared badly.

For a canoeing trip, or any journey on which a fullsized axe cannot be taken with the camping equipment, a half-axe with 2-pound head and 18-inch handle is about right. With it one can fell trees big enough for an all-night fire made Indian fashion. If such a tool is carried from the belt (seldom advisable) its muzzle should be attached by a frog that works on a loose rivet, thus forming a hinged joint, then the handle will swing free from brush and will not be in the way when you sit down.

For a light and quick-cutting hone, to keep knives and hatchet in order, take a piece of cigar box about x x two by six inches and glue to each side ’ a strip of emery cloth, coarse on one side, fine on the other. Or, if you don’t mind the weight, get a quite small double whetstone, coarse and fine on opposite sides. This may be carried in a light leather wallet, along with the following articles:

Small coil of copper snare wire. Needle and thread. Safety pins. One or two short fishing lines, rigged. p Spare hooks. Minnow hooks (with

m^Sency haif ^e barb filed off) for catching

These things with your gun, a dozen rounds of ammunition, hatchet, knives, matches, compass, map, money, pipe and tobacco, should always be with you, or where they can be snatched up at a grab in case of emergency. Then you are always “fixed.”

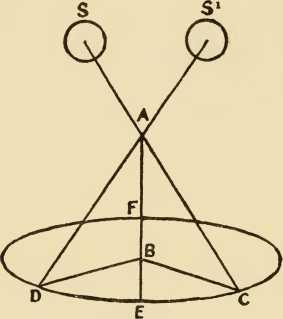

If a needle compass is chosen, try to get one with a pearl point on the north end of the needle; it is easier to see in dark weather, and easily re- ompass. membered. If you must put up with a common one in which the north end of the needle is merely blackened, scratch B=N (Black equals North) on the case. This seems like an absurd precaution, does it not ? Well, it will not seem so if you get lost. The first time that a man loses his bearings in the wilderness his wits refuse to work. He cannot, to save his life, remember whether the black end of the needle is north or south. A card compass Jis better than one with a needle, if the case is deep enough for the card to traverse freely when inclined, but it is more bulky.

An expensive watch should be left at home. A dollar watch is good enough where there are no trains to . catch. Take with you the sheets of an

p ’ almanac for the months in which you will be out. They are useful to regulate the watch, show the moon’s changes, and, by them, to determine the day of the month and week, which one is apt to forget when he is away from civilization.

Do not on any account omit a waterproof matchbox, preferably of such pattern as has a cover that cannot __ x ,, drop off. A bit of candle is a good thing to carry in one’s pouch to start fire in a driving rain.

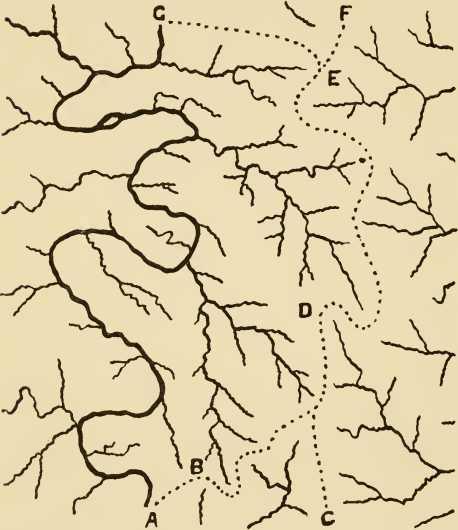

Procure, if possible, a good map of the region to be visited. The best maps for any part of the United

Maps.

States for which they have been published are the topographical sheets

&&&issued by the U. S. Geological Survey, and sold at five cents each. A list of those published up to date can be had by applying to the Director, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D. C. Most of these sheets are on a scale of two miles to the inch. They are printed in three colors, and show every watercourse, big or little, every road and important trail, bridges, ferries, fords, mines, settlements, and, what is of high importance to a traveler, they give contour lines (usually for every 100 feet in mountainous regions, and at lesser intervals for more level country).{2}

Maps should be cut up into sections about 4 by 6 inches, numbered, and carried (together with a keymap that one makes himself) in an envelope made of tracing cloth. The required sheet is placed on top, and can be made out through the envelope without removing it, thus protecting the map from tearing, soiling, wet, and from blowing away.

Note-books should be of such paper as is ruled in squares, which are useful in rough mapping and sketch- q . ing. Take along some postal cards,

&&&a lonery. anj & timetab]e of the road by which

&&&you expect to return.

Wear a money belt. Gold coin is more trusty than banknotes, as one is liable to get a ducking at any time. Quarter eagles are best, being more easily changed by country folks than higher denominations.

In the matter of medicines, every man must take into account his personal equation and the ills to which . he is most subiect; but there are cer-

,iyi cd icincs *

&&&tain risks that we all run in common

&&&when we venture far from civilization, such as wounds, fractures, snake-bites, attacks of venomous insects, malaria, footsoreness, ivy poisoning, and others that will be mentioned in the chapter on Accidents.

As for myself, no matter how light I travel, I always carry either in a pocket or in my hunting pouch a soldier’s first-aid packet. This can be procured from a dealer in surgical instruments or from a camp outfitter. It contains two antiseptic compresses of sublimated gauze, an antiseptic bandage, an Esmarch triangular bandage with cuts printed on it showing how to bandage any part of the body, and two safety pins, inclosed in a waterproof cover, the whole being very light and compact.

In snake time I also keep by me at all times a hypodermic syringe with tubes of potassium permanganate and strychnin, the use of which will be explained hereafter. A permanganate solution will precipitate a sediment in a week or two. It is better to carry separately the crystals and a little vial of distilled water. A small bottle of unguentine and some cathartic pills generally complete the list for a short trip.

.1 Proud Moment

When going far from medical or surgical aid, I might pack along a box containing the following kit:

3-in. artery forceps and needle-holder combined.

Tooth forceps.

Surgeon’s needles: 2 straight medium,

1 curved medium,

1 curved small.

Surgeon’s silk, coarse and fine.

Catgut ligatures.

3 2-m. rolled bandages.

1 yd. sublimated gauze, in bottle.

Absorbent cotton.

Mustard plasters.

Belladonna plasters.

Hypodermic syringe.

Bernays’ antiseptic tablets.

| - Potassium permanganate, | -grain tablets. |

-

Cocain and morphin tablets (cocain 1-5 gr., morphin 1-40 gr., sod. chlor. 1-5 gr.)—local anaesthetic.

-

Morphin (J gr.) and atropin (1-150 gr.) tablets—intense pain.

-

Strychnin sulphate, 1-30 gr. tablets—surgical shock, etc.

Quinin, 3 gr. capsules—malaria, etc.

»»-Sun cholera tablets—dysentery, etc.

Senega compound, tablets—coughs, colds.

Compound cathartic pills.

Soda mint tablets—sour stomach, heartburn, ivy poisoning.

Trional—sleeplessness.

Unguentine—burns, sunburn, insect bites, bruises. McClintock’s germicidal soap—cleansing wounds. Vaselin.

8 oz. brandy, in two small bottles.

One such kit is enough for a large party. It will be used mostly on the natives.

An ulcerated tooth is a bad thing to fight in the wilderness—grizzly bears are nothing to it. Some natives have an unpleasant way of extracting an aching

* The tablets starred are carried in the hypodermic case. molar, a bit at a time, by prying it out with an awl. Paul Kruger used to cut his out with a knife. A word to the wise is sufficient: Forceps.

When traveling in the South or Southwest (anywhere from Missouri down), I add a 4-ounce bottle of chlorop. p form, which, after exhaustive experi-

7 °Pes* ments, I have found to be the only thing that can be depended upon to put chiggers (red- bugs) to sleep in the cuticle of H. Kephart. I will pay my respects to these microscopic fiends, and to other torments of the woods and swamps, in the chapter on Pests, wherein will also be found various formulas for fly dopes, to which the reader is referred.

In spring and autumn I usually carry a tiny vial of oil of anise, which is very attractive to various animals whose acquaintance I wish to cultivate—from bees to bears. One drop of anise will lure for half a mile radius.

In hot weather it is well to carry, each for himself, a little citric acid, if there are no lemons in the outfit.

Acids.

The crystals added to water make a refreshing lemonade, and they are val

&&&uable to neutralize alkaline water and make it potable. Wyeth’s lemonade tablets are still better. When much water is to be corrected, as when making a long trip through an alkaline country, it is preferable to use hydrochloric (muriatic) acid, one teaspoonful to the gallon of water.

Spare clothing should be packed in a bag by itself. It is well to make this in saddle-bag shape, one side Clothes Ba use(^ ^or clean clothes and the

&&&other for soiled ones, the whole serving as a pillow if you have no regular pillow-bag. For an ordinary trip the following will suffice:

Jersey or sweater, two undershirts, two pairs drawers, three pairs socks, spare overshirt, moccasins, gloves, three handkerchiefs, woolen pyjamas (not linen), if you have room. In summer add a head-net; in winter, German socks, lumberman’s rubbers (if you cannot get shanks), knit cap, and a pair of mitts.

Toilet Bag. In a sponge-bag carry:

Towel (old and soft), soap, comb, toothbrush, pocket mirror; the soap in a soft rubber tobacco-pouch. The razor and strop, if you carry them, go elsewhere.

If you smoke, stow a spare pipe in your kit—the koosy-oonek will get one, sure. If you wear glasses, take along an extra pair.

In one’s camp kit it is advisable to have a holdall, or a japanned box, in which are kept such things as

. . these (contents varying, of course, acRepair -1 • , i , x

r cording to personal requirements):

Rifle-rod and brush, gun grease, cut wipers, oiled rags, screw driver (T-shaped, folding, with 3 blades), 6-in. halfround bastard file, a few assorted nails and tacks, two sizes soft wire, side-cutting parallel pliers, pocket tape-measure, pocket scales, scissors, awl, waxed-ends (get a shoemaker to make them for you if you don’t know how), sewing and darning needles, linen thread, beeswax, strong twine, darning cotton, spare buttons, safety pins, split rivets, small pieces of mending cloth and leather, a rawhide belt-lace, 1 doz. large rubber bands.

In fitting up such a repair kit, be sparing of bulk and weight. Of nails, wire, rivets, include only enough for a few small jobs.

In winter it pays to carry a pair of smoke-colored goggles, to prevent snow-blindness—likewise in summer if you are much on the water.

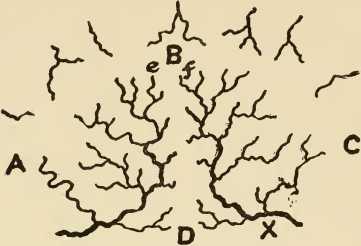

88 * These are better than green or blue ones, because they are less opaque and there is less loss of color in objects seen through them. They should fit well. The glasses should be surrounded by fine wire gauze, the edges covered with velvet, and the part crossing the bridge of the nose similarly covered. The Eskimo kind of eye-shades are better for high latitudes than glasses. They consist of two wooden disks, each with a T-shaped slit cut in it to see through, with a narrow strap to go over the bridge of the nose and another to go around the head. Such shades give perfect vision, do not collect moisture, and, when removed, do not give the sensation of darkness that is experienced after removing colored glasses.