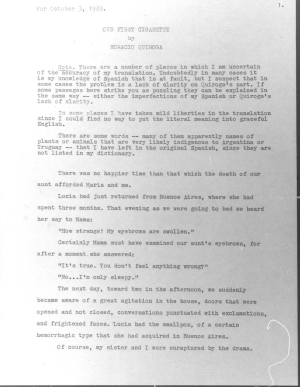

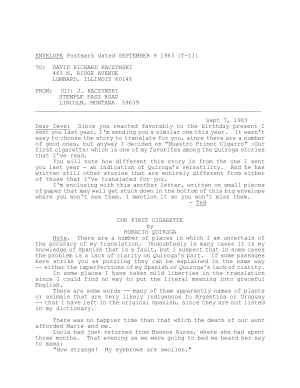

Horacio Quiroga & Ted Kaczynski

Our First Cigarette

Note. There are a number of places in which I am uncertain of the accuracy of my translation. Undoubtedly in many cases it is my knowledge of Spanish that is a fault, but I suspect that in some cases the problem is a lack of clarity on Quiroga's part. If some passages here strike you as puzzling they can be explained in the same way -- either the imperfections of my Spanish or Quiroga's lack of clarity.

In some places I have taken mild liberties in the translation since I could find no way to put the literal meaning into graceful English.

There are some words -- many of them apparently names of plants or animals that are very likely indigenous to Argentina or Uruguay -- that I have left in the original Spanish, since they are not listed in my dictionary.

There was no happier time than that which the death of our aunt afforded Marie and me.

Lucia had just returned from Buenos Aires, where she had spent three months. That evening as we were going to bed we heard her say to mama:

"How strange! My eyebrows are swollen."

Certainly Mama must have examined our aunt's eyebrows, for after a moment she answered:

"It's true. You don't feel anything wrong?"

"No...I'm only sleepy."

The next day, toward two in the afternoon, we suddenly became aware of a great agitation in the house, doors that were opened and not closed, conversations punctuated with exclamations, and frightened faces. Lucia had the smallpox, of a certain hemorrhagic type that she had acquired in Buenos Aires.

Of course, my sister and I were enraptured by the drama. Children almost always have to endure the misfortune that the great events do no occur in their own house. This time our aunt -- by chance our aunt! -- down with smallpox! I, lucky boy, already was proud to possess the friendship of a policeman and to have had contact with a clown who, jumping up the steps [in some show or circus, I take it], had taken a seat at my side. But now the great event was taking place in our own house; and upon communicating it to the first little boy who stopped at eh street door to look, I already had in my eyes the vanity with which a child in strict mourning passes before his astonished and envious little neighbors.

That same afternoon we moved out of the house, installing ourselves in the only other that we could find on such short notice, an old country-house on the outskirts of town. A sister of Mama's who had had smallpox in her childhood remained at Lucia's side.

Certainly, during the first days after the event, Mama passed through cruel anguish for her children, who had kissed the woman now sick with smallpox. But we on the other hand turned into enthusiastic Robinson Crusoes and had no time to remember our aunt. For a long time the country-house had been sleeping in its damp and shadowy tranquility. Orange-trees whitish with diaspis; peach-trees split at the fork; quince-trees with the appearance of osiers; fig-trees dragging on the ground through neglect; all that, among the thick beds of dead leaves that smothered footsteps, gave a strong impression of paradise.

We weren't exactly Adam and Eve; but we were indeed heroic Robinson Crusoes, dragged into our exile by a family tragedy; the death of our aunt, which happened four days after we began our explorations.

We would spend the whole day poking around the grounds, though the fig-trees, too thick underfoot, inconvenienced us a little. The well, too, was an object of our geographical preoccupation. It was an old unfinished well, the work on which had been abandoned at a depth of some forty-five feet. It had a rock bottom and was now disappearing among the culantrillos and doradillas of its walls. It was necessary, nonetheless, to explore it, and by way of an outpost we succeeded after infinite effort in bringing to its edge a great stone. As the well was hidden by a (UI), we were able to execute this maneuver without Mama's finding out about it. All the same, Maria, whose poetic inspiration always prevailed in our enterprises, decided that we had to put off the event until a great rain, half filling the well, should offer us an artistic satisfaction to equal the scientific.

But what especially attracted our daily assaults was the cane thicket. We spent two whole weeks in duly exploring that primeval tangle of green stalks, dry stalks, vertical stalks, bent, cross-wise, broken, down-turned stalks. The dry leaves, caught in their fall, were interwoven with the mass, which filled the air with dust and fragments at the slightest touch.

We found out the secrets of the place all the same, and sitting in the gloomy lair of some corner, close together and mute in the semidarkness, we revelled for whole hours in the pride of not being afraid.

It was there that one afternoon, embarrassed at our lack of initiative, we concocted the idea of smoking. Mama was a widow; two sisters of hers always lived with us, and at the moment a brother also, the very one who had gone with Lucia to Buenos Aires.

This uncle, twenty years old, very elegant and presumptuous, had taken upon himself a certain authority over us which Mama, what with the current annoyance and her lack of character, encouraged.

Maria and I promptly professed the warmest dislike for the little stepfather.

"I'll tell you," he would say to mother, indicating us with a jerk of his chin, "that I'd like to live with you all the time just to keep an eye on your children. They're going to give you a lot of trouble."

"Oh, leave them alone," Mama would answer, tired.

We wouldn't say anything, but we would look at each other over the dish of soup.

From this strict personage, then, we had stolen a pack of cigarettes; and though we were tempted to initiate ourselves immediately into the manly art of smoking, we waited for the appropriate device. This consisted of a pipe that I manufactured, with a piece of cane for the bowl and a curtain-rod for the stem, stuck together with putty from a recently replaced window-pane. The pipe was perfect: big, particolored, and frivolous-looking.

In our den in the cane thicket Maria and I filled it with firm and religious unction. Five cigarettes yielded their tobacco to it. We then seated ourselves with our knees up; I lit the pipe and inhaled. Maria, who was devouring the action with her eyes, saw that mine were filling with tears: there never has been and never will be seen anything more abominable. I nevertheless swallowed the nauseating saliva.

"Is it good?" Maria asked eagerly, putting out her hand.

"Good," I answered, passing her the horrible device.

Maria sucked, even harder than I. Watching her closely, I noted her tears in turn, and the simultaneous movement of her lips, tongue, and throat rejecting it. Her courage was greater than mine.

"It's good," she said with watering eyes, almost grimacing. And heroically she again raised the brass tube to her mouth.

It was urgently necessary to rescue her. It was pride and nothing else that sent her back to that infernal smoke that tasted like salt of Chantaud, the same pride that has made me praise the nauseating combustion.

"Pst!" I said abruptly, turning my head to listen, "I think it's the gargantillo we heard the other day. It must have a nest here."

Maria stood up, leaving the pipe lying on its side; and with attentive ears and searching eyes we drew away from the place, seemingly anxious to get a look at the little animal, but actually clutching like dying men at the honorable pretext I had invented for prudently withdrawing from the tobacco without having our pride suffer.

A month later I went back to the can pipe, but with a very different result.

For some prank or other of ours, our little stepfather had raised his voice to us much more harshly than my sister and I could permit him to do. We complained to Mama.

"Bah! Don't pay any attention," she answered, almost without having heard us. "That's just the way he is."

"One of these days he's going to hit us," whined Maria.

"He won't if you don't give him a reason to. What did you do to him?" she added, addressing the question to me.

"Nothing, Mama, ... but I don't want him to touch me!" I objected in my turn.

At that moment our uncle came into the room.

"Oh, so here's your little villain Eduardo ... That kid is going to give you gray hair! You'll see!"

"They're complaining that you want to hit them."

"Me?" exclaimed the little stepfather, drawing himself up, "I haven't even thought of it. But as soon as they treat me disrespectfully..."

"And you'll be doing the right thing," Mama agreed.

"I don't want him to touch me!" I repeated, scowling and red in the face. "He isn't Papa!"

"But in the absence of your poor father, he's your uncle.

Now leave me in peace!" she concluded, pushing us away.

By ourselves in the courtyard, Maria and I looked at each other with eyes full of proud fire.

"Nobody's going to hit me!" I declared.

"No, nor me either," she added on her own account.

"He's a zonzo 1!"

The inspiration came abruptly and, as always, to my sister. With a furious laugh she began the triumphal march and the chant:

"Uncle Alfonso ... is a zonzo! Uncle Alfonso ... is a zonzo!" When I ran into the little stepfather a while afterward, it appeared from the way he looked at me that he had heard us. But

1 Zonzo = boob, fool we had already planned the incident of the Kicking Cigarette, this epithet being to the greater glory of the mule Maud.

The kicking cigarette consisted, in brief, of a firecracker 2 which, wrapped in cigarette paper, was placed in the pack of cigarettes that Uncle Alfonso kept on his night-table, smoking them during the siestas.

One end of the firecracker had been cut off os that the effect on the smoker would not be excessive. The violent stream of sparks would be enough, and the whole success of the trick depended on the assumption that our drowsy uncle would not notice the peculiar rigidity of his cigarette.

Things sometimes happen so suddenly and in such a way that there is neither time nor breath to take account of them. I only know that during a certain siesta the little stepfather burst out of his room like a bomb, runnung into Mama in the dining room.

"Ah! There you are! Do you know what they've done? I swear that this time they're going to remember!"

"Alfonso!"

"What? You too? That's all I needed! If you don't know how to bring up your children, I'm going to do it!:

On hearing the furious voice of my uncle, I, who was innocently occupied with my sister in scratching lines on the metal rim of the cistern, made a detour through the second door of the dining room and stationed myself behind Mama. The little stepfather saw me then and made a dash at me.

"I didn't do anything!" I cried.

"You just wait!" roared my uncle, chasing me around the table.

"Alfonso! Leave him alone!"

2 Cohete = literally rocket, but I think here a firecracker must be meant.

"I'll leave him to you when I'm done with him!"

"I don't want him to touch me!"

"Come on, Alfonso, You're acting like a child!"

This was the last thing that one ought to say to the little stepfather. He swore and took after me at such a speed that he was on the point of catching me. But at that instant I flew out of the open door like an arrow and took off for the farther parts of the grounds, with my uncle on my heels.

In five seconds we shot like a meteor through the peach-trees, the orange-trees, and the pear-trees, and it was at that moment that the idea of the well and its stone presented itself to my mind with terrible clarity.

"I don't want him to touch me!" I screamed again.

"You just wait!"

At that instant we reached the cane thicket.

"I'm going to throw myself in the well!" I howled, so that Mama would hear me.

"I'm the one who's going to throw you in!"

Abruptly I disappeared from his sight behind the cane; without breaking my stride I gave a shove to our exploratory stone that was still waiting for a rain, and jumped off to one side, burying myself in the dead foliage.

My uncle, without seeing me, arrived in time to hear from the bottom of the well the awful thud of a body smashing.

The little stepfather stopped, completely livid; he turned his dilated eyes this way and that, and approached the well. He tried to look into it but the culantrillos prevented him. Then he seemed to think for a moment, and after a careful look at the well and its surroundings he began to search for me.

Since it was unfortunately not long since Uncle Alfonso himself had stopped hiding in order to avoid bodily encounters with his parents, eh still preserved a very fresh memory of the strategies involved, and he made every possible effort to find me.

He located my den immediately and kept returning to it with admirable intuition, but apart from the fact that the primeval tangle of dead leaves hid me completely, the sound of my body shattering at the bottom of the well had my uncle seriously upset, and, in consequence, he did not search efficiently.

It was, then, settled that I was lying in the well, crushed, which gave rise to what we may call my posthumous revenge. The problem was quite clear: How was my uncle going to explain to Mama that I had killed myself in order to avoid having him hit me?

Ten minutes passed.

Mama's voice suddenly rang from the courtyard. "Alfonso!" "Mercedes?" he answered after an abrupt start.

Certainly Mama sensed something wrong, for her voice was heard again, disturbed.

"And Eduardo? Where is he?" she added, stepping forward.

"Here with me," he answered laughing. "We've made peace."

Since Mama couldn't see from a distance his pallor or the ridiculous grimace that he meant for a beatific smile, all was well.

"You didn't hit him, did you?"

"No. It was only a joke."

Mama went back in. Joke! It was beginning to be my joke on the little stepfather.

Celia, my eldest aunt, who had finished her siesta nap, crossed the courtyard and Alfonso summoned her with a silent gesture. Moments later Celia gave a smothered "oh!" raising her hands to her head.

"But, how? What a horror! Poor, poor Mercedes! What a blow!"

It was necessary to decide on something before informing Mercedes. Might I be brought up alive? ... The well was forty-five feet deep with a solid rock bottom. Maybe, who knows ... But for that, one would have to bring ropes, men; and Mercedes ...

"Poor, poor mother!" my aunt repeated.

It must be said that for me, the little hero, martyr to his corporal dignity, there was not a single tear. Mama monopolized all those effusions of grief, to which they sacrificed the remote possibility of life that I might still have down there. This, wounding my vanity both as a corpse and as a living being, intensified my thirst for vengeance.

Half an hour later Mama asked for me again, and Celia answered her with such poor diplomacy that she was immediately certain there had been a catastrophe.

"Eduardo, my son!" she exclaimed, pulling away from the hands of her sister who was trying to hold her, and rushing out to the grounds.

"Mercedes! I swear nothing's happened! He's gone out!"

"My son! My son! Alfonso!"

Alfonso ran to meet her, stopping her when he saw she was heading for the well. Mama wasn't thinking of anything definite, but when she saw the horrified gesture of her brother she remembered my exclamation of an hour before and shot forth a frightening shriek.

"Ay! My son! He's killed himself! Let me go! Let me go! My son, Alfonso! You've killed him!"

They carried Mama away senseless. I hadn't been moved in the slightest degree by Mama's desperation, since I -- the cause of it

-- was in fact alive and very much alive, merely, at the age of eight, playing with emotion as do the great who use semitragic surprises: the pleasure she will have when she sees me!

Meanwhile, I was experiencing inward delight at the little stepfather's discomfiture.

"Hmm! ... Hit me!" I grumbled, still under the dead leaves. Rising then with caution, I squatted in my den and picked up the famous pipe carefully hidden in the foliage. That was the right time to dedicate myself seriously to smoking the rest of the pipe.

The smoke of that tobacco that had been wetted, dried, and wetted and dried again an infinity of times, had then a taste of cumbari, Coirre solution, and sodium sulfate much more advantageous than the first time. Nevertheless I undertook the task, which I knew to be hard, with brows contracted and teeth clenched on the mouthpiece.

I smoked, I like to think, the fourth pipe. I only remember that at the end the cane thicket turned entirely blue and began to dance before my eyes at a distance of two fingers' breadths. Two or three hammers on each side of my head began demolishing my temples, while my stomach, right up in my mouth, itself breathed directly the last few mouthfuls of smoke.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I came to as they were carrying me in their arms to the house. In spite of how horribly sick I felt I had the wisdom to stay asleep, on account of what might happen. I felt Mama's delirious arms shaking me.

"My darling son! Eduardo, my son! Ah, Alfonso, I'll never forgive you for the grief you've caused me!"

"Oh, come on!" my eldest aunt was saying, "Don't be silly, Mercedes! You can see there's nothing wrong with him!"

"Ah!" replied Mama, putting her hands to her heart with an immense sigh, "Yes, it's alright! ... But tell me, Alfonso, how could he have helped hurting himself? That well! My God!"

The little stepfather, broken down, spoke vaguely of crumbling and soft earth, preferring to leave the true explanation for a calmer moment; while poor Mama took no notice of the horrible stink of tobacco that her little suicide was exhaling.

Finally I opened my eyes, smiled, and went to sleep again, this time genuinely and deeply.

Late in the day, Uncle Alfonso woke me up.

"What do you think I should do to you?" he asked with hissing rancor. "What I'm going to do tomorrow is tell your mother everything and then you'll see what thanks are!"

I was still seeing rather badly, things were dancing a little, and my stomach was still stuck in my throat. Nevertheless I answered:

"If you tell Mama anything I swear this time I really will throw myself in the well!"

The eyes of a young suicide who has heroically smoked his pipe -- do they perchance express a desperate courage?

Possibly so. At any rate the little stepfather, after looking at me fixedly, shrugged his shoulders, drawing the sheet, which had slipped down a little, up to my neck.

"I think I would do better to make friends with this microbe," he murmured.

"I think the same," I answered.

And I went to sleep.

FIN