Hye Seung Chung

Beyond “Extreme”

Rereading Kim Ki-duk’s Cinema of Ressentiment

Critical Debate: Sexual Terrorism or Necessary Ressentiment?

Corporeal Effects: “Extreme Fishhook Penetration” and Transnational Canons

A Postcolonial Rationale for Violence

Beginning in the 1950s and 60s, the films of Kurosawa Akira, Ozu Yasujiro, and Mizoguchi Kenji entered the Western canon of East Asian cinema under the various rubrics associated with auteurism and art cinema. Throughout the 1980s and 90s, Fifth-Generation Chinese filmmakers such as Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige rose to international fame for their exotic, ethnographic films, sparking critical debates about self-orientalism, among other things (Chow 142–72). In recent years, however, the dominant mode of East Asian canon-formations in the West appears to have shifted into an area that can be (and has been) described as “extreme cinema.”[1] Under this blood-soaked banner are assembled some of the most iconoclastic auteurs in East Asia, including Fruit Chan, the Pang Brothers, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Miike Takashi, Kitano Takeshi, Park Chan-wook [Pak Ch’an-uk], and Kim Ki-duk [Kim Ki-do˘k], who are all enjoying a spike in international recognition and cult fandom, due in part to the visceral nature of their disturbing yet engrossing films, which frequently shuttle between tranquility and terror, the sublime and the grotesque.

According to one anonymous contributor to Wikipedia, “Extreme cinema is a term typically used to describe films containing violence, gore, and sex of an extreme nature. In recent years, the term has been a popular word to describe many of the violent films coming out of Asia (particularly Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea).” The online encyclopedia entry lists the names of four East Asian directors (Miike Takashi, Park Chan-wook, Tsukamoto Shinya, and Kim Ki-duk) as examples of “the more notorious ‘extreme’ filmmakers” (“Extreme Cinema”). Alongside Park Chan-wook, famous for his “vengeance trilogy” of films (Poksu nuˇn na uˇi koˇt [Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance] [2002], Oldboy [2003], and Ch’ingoˇlhan Kuˇmjassi [Lady Vengeance] [2005]), Kim Ki-duk is arguably the most acclaimed Korean auteur in the Western world. An unprecedented ten of Kim’s fifteen feature-length motion pictures are currently available in the US home video market.[2] Among these thematically interrelated yet stylistically disparate films, including Soˇm [The Isle] (2000), Shilje sanghwang [Real Fiction] (2000), Nappuˇn namja [Bad Guy] (2001), and Haeansoˇn [The Coast Guard] (2002), his awardwinning Buddhist fable Pom yo˘ru˘m kau˘l kyo˘ul ku˘rigo pom [Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring] (2003) became an international art-house hit, breaking all previous box-office records of South Korean films receiving theatrical distribution in the United States and Europe.[3] Around the time of this film’s US release (beginning in April of 2004), Kim successfully made his way into Western critics’ East Asian film canons by winning two prestigious Best Director awards from the Berlin and Venice International Film Festivals, for Samaria [Samaritan Girl] (2004) and Pin jip [3-Iron] (2004), respectively. As the mother of all tributes to a maverick filmmaker whose “sensuous, sensational imagery and wild and haunting narratives” have enthralled film festival juries and extreme cinema aficionados around the world, the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) held a then-complete retrospective of Kim’s fourteen films between 23 April and 8 May 2008 (MoMA Exhibitions 2008).[4]

Regardless of the ceaseless controversy surrounding Kim Ki-duk both at home and abroad, MoMA’s endorsement and showcasing of his entire oeuvre—the first of its kind granted to a Korean filmmaker[5]—demonstrates that Korean cinema can now boast its own Kurosawa Akira, its own Zhang Yimou, its own visionary auteur whose border-crossing reputation promises to boost the status of the nation’s earlier and future cultural productions in the global arena.[6] Such rhetorical maneuvers by critics may prove to be problematic, however, given that the pigeonholing of Kim as a Korean Kurosawa or Zhang—and, by extension, the labeling of Korean cinema as something derivative (or, in the words of Anthony C. Y. Leong, “the New Hong Kong”)[7]—has the potential to reproduce dominant ideological positions vis-à-vis the abstracted Asian other, with an attendant risk of rendering diverse cultural traditions as interchangeable elements within a monolithically conceived canon endorsed by Western scholars and Euro-American institutions. Moreover, these kinds of ahistorical analogies threaten to reduce a centralized yet discursive national cinema to a mere handful of exceptional filmmakers, an auteurist folly criticized by several scholars in the context of classical Hollywood cinema (Schatz 5) but rarely challenged in the context of East Asian cinema.

A social outcast and autodidact, Kim Ki-duk has a very different background from that of Kurosawa or Zhang, who were trained in prestigious film institutions, Toho Studios and the Beijing Film Academy, respectively. In addition, this ex–sidewalk artist continues to operate in an expressive, “semi-abstract” realm (to borrow his own words), departing from the primarily realistic diegetic worlds and classical narratives found in Kurosawa’s and Zhang’s films. And yet despite their apparent dissimilarities, one can detect reception-based parallels among the three directors, each one at least partly responsible for “instituting” a passion for Asian genre films in the West (from Kurosawa’s samurai films of the 1950s and 60s to Zhang’s historical melodramas made three decades later, to the “extreme” cinema being grinded out by Kim and his contemporaries in the new millennium). At the risk of being reductive, one can argue that a pervasive Orientalism—far from being consigned to the grave by postcolonial scholars—is what links the Western reception of “exotic” East Asian cinemas across national borders and increasingly porous genres over the course of the past six decades.

More specifically, by lumping Kim Ki-duk’s socially conscious (if also exploitative) dramas with such assorted East Asian genre films, from supernatural horror flicks like Hideo Nakata’s Ringu [Ring] (1998) to psychological thrillers like Takashi Miike’s Odishon [Audition] (1999) to science fiction spectacles like Min Pyoˇng-ch’oˇn’s Natural City (2003), under the inclusive umbrella of “extreme cinema,” one is likely to gloss over the cultural specificity of his necessarily brutal cinema. Although the excessively coded and deeply felt corporeal effects (from vomiting to fainting) of his visceral psychosexual thriller The Isle are what made Kim an overnight sensation, a complete hermeneutic picture of his films—a full understanding of their complex social meanings—would be lost if aesthetic celebration or condemnation of such effects were to take precedence over a culturally specific analysis of cinematic pain and violence as a form of therapeutic ressentiment. Translated into “resentment” or “hostility,” this French term is central to Friedrich Nietzsche’s conceptualization of morality. According to the German philosopher, this state of mind arises when the powerless and oppressed, who are “denied the proper response for action, compensate for it only with imaginary revenge” (20). Taking this concept as a theoretical springboard, this article investigates how and why Kim’s cinema of ressentiment is often misunderstood as something else, as something other (from “sexual terrorism” to cheap thrills) inside and outside South Korean institutional and cultural contexts.

After pinpointing some of the brightest (if not always most illuminating) points of light within the larger constellation of local and global debates surrounding Kim Ki-duk, I situate the auteur’s body of work (which can be said to work on the body) within the critical category of what Linda Williams refers to as “body genre” films. But rather than slavishly following Williams’s path and employing psychoanalytic theory in hopes of elaborating the affective excess unique to such a genre, I probe the postcolonial, historical implications of cinematically realized sadomasochistic violence. Finally, this article teases out some of the semiautobiographical elements in Kim’s films so as to explore the connotative meanings of silence on the part of subaltern protagonists—men and women whose refusal, rather than inability, to speak to members of the social elite mimics the recalcitrant acts of the director offscreen. This self-reflexive relationship suggests that, despite its seemingly outdated status in postmodernist film studies, auteurism retains its explanatory power as long as such deeply personal films as Kim’s continue to emerge in the age of global media flows and increased conglomeration.

Critical Debate: Sexual Terrorism or Necessary Ressentiment?

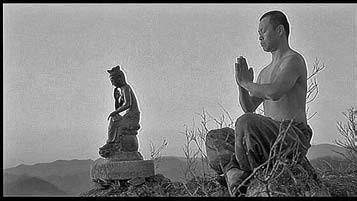

A landmark achievement in this controversial auteur’s prolific career and the winner of the Best Picture Award at the 2004 Grand Bell (Taejongsang) Awards, the Korean equivalent to the Oscars, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring includes an autobiographical scene in the penultimate winter chapter. After serving time in prison for murder, a former monk (played by the director himself) returns to a floating temple in the middle of a lake, the film’s idyllic central setting. In one of his physically rigorous training sessions, the ex-monk—seeking atonement and spiritual rebirth—drags a heavy stone Buddha up to the summit of one of the surrounding mountains, which commands a panoramic view of the world beneath him. This scene is significant insofar as it connotes, in allegorical fashion, Kim’s own life journey: his ultimate ascendancy in the world of filmmaking as well as his artistic introspection and maturation. Like his onscreen character, before climbing to such heights of fame, before gaining recognition as a world-class auteur, Kim had to overcome enormous obstacles and hardships, the likes of which would be unthinkable to his contemporaries from privileged backgrounds. As a middle-school dropout victimized by domestic violence, an exploited factory worker, a wrongly court-marshaled marine, a vagabond street artist in Paris, and a self-educated screenwriter lacking the familial, educational, and professional connections necessary to succeed in South Korea, Kim encountered one setback or difficulty after another.[8] Yet, like the monk in Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring, he has risen above it all. However, Kim Ki-duk’s international fame did little to improve the box-office performance of his independently produced art films in his homeland or to assuage the critical controversy plaguing this iconoclastic director, who apparently got under the skin of members of the Korean press as early as 1997, a year after his widely neglected debut, Agoˇ [Crocodile] (1996). In the wake of the negative critical and commercial reception of his second feature, Yasaeng tongmul pohoguyoˇk [Wild Animals] (1997),[9] Kim sent a provocative fax to South Korean dailies, declaring his outright “hatred” toward indifferent, dismissive, or hostile journalists who, in his opinion, were responsible for keeping audiences away from his films. The critical reception of Kim’s films has since been divided into polemical positions and diametrically opposing extremes. Although there has been a steady stream of accolades from domestic critics and cult film fans who have followed Kim’s career since the early days, a majority of the public has either ignored or denounced his films, primarily because of their disturbing images of violence (from murder and cannibalism to animal cruelty and body mutilation to rape and sadomasochistic sex) and often discontinuous, discombobulating narratives (filled with ellipses, fissures, contradictions, and fantasies). The ferocious rhetoric adopted by the latter group, who went so far as to call Kim Ki-duk a “psychopath,” attests to the fact that such films not only upset or alienate mainstream sensibilities but also undermine middle-class conformity in South Korea.

In Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema, Rey Chow lays out several accounts of critics who have criticized the films of Zhang Yimou, mainland China’s most celebrated yet controversial filmmaker, who, like Kim, is known for his distinct visual style:

First, we hear that Zhang’s films lack depth, a lack that critics often consider as the reason why his films are beautiful.... Second, Zhang’s “lack of depth” is inserted in what became debates about the politics of cross-cultural representations. The beauty of Zhang’s films is, for some critics, a sign of Zhang’s attempt to pander to the tastes of foreigners.... Even though Zhang and his contemporaries are “orientals,” then, they are explicitly or implicitly regarded as producing a kind of orientalism. Third, this lack of depth, this orientalism, is linked to yet another crime—that of exploiting women. Zhang’s films are unmistakably filled with sexually violent elements. (150–51)

The preceding quotation approximates the kinds of criticisms Kim Ki-duk has encountered both at home and abroad despite critical consensus endorsing his instinctual yet painterly aesthetic sensibilities—his predilection for primary colors and water imagery. As with Zhang, the integrity and sincerity of the Korean filmmaker have been questioned by cynical critics accusing him of having “sold out” to North American and European festival programmers, juries, and art-house movie patrons who are drawn to “exotic” visuals and shock-filled material.

One group in particular—Korean feminists— has delivered the most cohesive critique of Kim Ki-duk, whose films are often populated with prostitute characters and frequently feature scenes of sexual violence. For example, Yu Gina called Kim’s feature debut Crocodile a “rape movie” (Choˇng 85), and Chu Yu-sin deemed Kim’s most commercially successful film, Bad Guy, an example of “dangerous penis fascism” (34). Echoing the reactions of their Korean counterparts, some American female journalists have been offended by Kim’s films, as exemplified by Carina Chocano’s review of Bad Guy for the 1 April 2005 issue of the Los Angeles Times. Describing the film’s plot, in which a vengeful underworld pimp turns a middle-class college student into a sex worker, Chocano labels it “a metaphor only a Marxist critic could love,” which suggests that “you can take the middle class out of the girl, but you can’t take the whore out of the woman” (E-6).

Despite its seemingly misogynistic premise, which has been frowned upon by female critics such as Chu and Chocano, Bad Guy is a far cry from conventional sexploitation fare. In fact, sex scenes oftentimes take place offscreen and when depicted within the frame are presented in long shots and long takes to emphasize the pain, rather than the pleasure, experienced by female characters. There is no implication of a sexual relationship between the two protagonists, brothel thug Han-gi and college student– turned–prostitute Soˇn-hwa, who gradually falls in love with this man who is responsible for her own social downfall. Upon closer scrutiny, Bad Guy is a multilayered text skillfully interweaving reality and fantasy as well as soft-porn melodrama and indictments against Korea’s class system. Ending with a bittersweet “happy ending” (framed as a mortally stabbed Han-gi’s dying dream) in which the interclass couple makes a living from roadside prostitution, Bad Guy should be taken as a reverse-Pygmalion social allegory, the flip side of George Bernard Shaw’s perennial play wherein the erudite Professor Higgins transforms the cockney-speaking flower girl Eliza Doolittle into a dignified lady.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of Bad Guy, it is vital that audiences interject an auteuristic interpretation of its “abject hero,”[10] to borrow a phrase coined by the literary critic Michael A. Bernstein. Like the other literally and figuratively silent underdogs populating Kim’s cinema (from T’ae-soˇk in 3-Iron to Chang Chin in Sum [Breath] [2007]), Han-gi is a semiautographical portrait of the director himself, someone who, before becoming an awardwinning filmmaker, lived a subaltern existence as an undereducated factory worker in South Korea. In an interview with Kim So-hee, Kim Ki-duk equated filmmaking with the metaphorical act of “kidnapping those of the mainstream into [his] own space, and then introducing [himself] to them as a human being,” rather than as a lowlife (as he is sometimes depicted in the Korean press). In another interview, Kim elaborates on his authorial intention behind Bad Guy: “People look at the world of prostitutes and hoodlums and say, ‘this is trash, we need to clean this up.’ But these people’s lives deserve to be treated with respect” (Paquet, “Close Up” 14). As a Nietzschean cinema of ressentiment, Kim’s films derive their vitality and momentum from raw emotions such as angst, frustration, envy, and resentment—emotions felt and exhibited by disenfranchised individuals ill-equipped to survive in an ultra-competitive society where exclusive college connections or family networks are prerequisites for upward mobility.[11]

In his book On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche defines ressentiment as a process by which disempowered and injured parties “anaesthetize pain through emotion ... a tormenting, secret pain that is becoming unbearable with a more violent emotion of any sort” (93). Although ressentiment was denounced as a vengeful and poisonous “slave morality” by Nietzsche, affirmative possibilities of the concept have been recuperated by contemporary scholars and philosophers. For example, M. J. Bowles argues, “Ressentiment in fact marks the potentiality of a tremendous energy source ... To exploit human ressentiment is something of an art” (14–15). Rebecca Stringer sees ressentiment as “an inevitable and potentially positive force in feminism” that is partly responsible for shaping such institutional practices as affirmative action and women’s studies (266–67). Jeffrey T. Nealon calls ressentiment a “political anger of transformation” that might “open a space for us to respond to subjective or communal expropriation in other than resentful ways” (277). According to Nietzsche, a profound comprehension of ressentiment is possible only by and among those who share the same ailments and agonies. To quote him, the sick are in need of “doctors and nurses who are sick themselves.... [The man of ressentiment] must be sick, he must really be a close relative of the sick and the destitute in order to understand them” (Nietzsche 92).

Themes and characters deriving from the writer-director’s lived experience are precisely what makes Kim Ki-duk’s cinema of ressentiment powerful and potent. In this regard, Kim’s corpus can be best described as a necessarily brutal cinema, one that accurately reflects and symbolically avenges the cruelty of a classist, conformist society. Although such New Wave filmmakers as Park Kwang-su, Jang Sun-woo (Chang Soˇn-u), and Chung Ji-young (Choˇng Chiyoˇng) have explored the wretched situations of the Korean underclass in the throes of stateinitiated modernization under military regimes (1961–92), their films typically privilege intellectual male protagonists who speak for subaltern characters. As such, the latter’s agency gets lost in these cinematic acts of cross-class ventriloquism. A good example of this occurs in Park Kwang-su’s biopic Aru˘mdaun ch’onyo˘n Cho˘n T’ae-il [A Single Spark] (1995), in which the life of martyred union activist Chon T’ae-il (who immolated himself in 1970 at the age of twenty-two in protest against the exploitation of sweatshop workers) unfolds from the perspective of his biographer, a fugitive law-school graduate. In contrast, Kim’s cinema is propelled by underdog protagonists—socially marginalized and oppressed subalterns such as homeless people, thugs, prostitutes, camptown residents, Amerasians, the disabled, inmates, and so on—whose only means of communicating their ressentiment is a shared sense of corporeal pain resulting from sadistic or masochistic acts of violence.

In Western film criticism, Kim Ki-duk’s potentially subversive cinema of ressentiment is often mistaken as simply another example of East Asian “extreme” cinema characterized by exploitative or sensationalistic use of sex, violence, and horror/terror. Kim’s most vocal nemesis in the English-speaking world seems to be the British critic Tony Rayns, otherwise known as an influential advocate of East Asian cinema and a supporter of several Korean directors, most notably Jang Sun-woo (the subject of his 2001 documentary, The Jang Sun-Woo Variations). In a controversial essay published by Film Comment in the winter of 2004, Rayns indicts not only Kim Ki-duk himself but also his “duped” champions (i.e., film festival jurors and sympathetic critics). Rayns goes so far as to call Kim’s 3-Iron a “shameless plagiarism” of Tsai Ming-liang’s Ai qing wan sui [Vive l’amour] (1994). He also refers to The Isle, Bad Guy, and Samaritan Girl as examples of “sexual terrorism.” Moreover, he denounces Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring as a faux Buddhist film that would appeal only to Orientalist Western critics who know nothing about Buddhism and whose “bullshit detectors [have stopped] working” when it comes to East Asian films (50–52). Unintentionally, Rayns’s condescending bashing of the factory worker– turned–director generated controversy online among cinephilic members of particular Web communities and ended up converting some former detractors of Kim Ki-duk (including the leading Korean feminist film critic Kim Soyoung) into his defenders (Martin).

Kim responded to this in a nonchalant way, stating, “[T]he way I see it is that recently I’ve been doing extremely well, and Tony’s giving me an opportunity to look back and reexamine my work.... We need not only sun but also rain for agriculture” (Smith N9). However, less forgiving bloggers passionately protested Rayns’s “hatchet job.” For example, in his appropriately titled blog post “Tony Reigns,” Ben Slater opines, “[I]ts main argument—that Kim has somehow fooled people into believing his terrible films are good—reveals that Rayns’s target isn’t actually Kim himself, but rather all the critics, curators, programmers, juries and audiences who have apparently committed the ultimate, unforgivable mistake. They didn’t listen to Tony.” The Singapore-based blogger persuasively argues, “Rayns has made his position clear—only people who don’t know anything about Asian cinema would embrace Kim Ki-duk. Where this leaves Asian critics who admire him, and programme him into their festivals, and the Asian audiences who admire his work, I have no idea.” To this list can be added a host of Asian producers who, within the past few years, have invested in his work (Hwal [The Bow] [2005] and Sigan [Time] [2006] were financed by Japanese company Happinet Pictures).

In response to the online hullabaloo sparked by Rayns’s three-page article, Chuck Stephens, an editor of Film Comment who had commissioned the piece, published his justifications in a 2005 issue of Cinema Scope. In this ostensible review of 3-Iron, Stephens makes his editorial intention clear: “My initial hope in asking Rayns to rework his already familiar-inKorea thesis was to sound a cautionary note at precisely the moment Kim stood on the verge of greatly expanding his American profile.... The umpteenth incarnation of exportable Asian cinema was the last thing anyone needed, with Kim cast as a more scabrous variation of Zhang Yimou.” This admission ironically confirms Slater’s suspicion that Rayns (and his editor) “[seem] to be wishing that Kim Ki-duk had remained obscure, that no one in the West had ever heard of him, and to take that desire further, that Kim had been unable to continue making films (which given his lack of success in South Korea is a likely scenario).” Despite Rayns’s and Stephens’s efforts to diminish his Euro-American profile, Kim’s international reputation remained intact, culminating in Breath’s entry into the competition section at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival as well as the aforementioned 2008 MoMA retrospective.

As a Korean-born woman who has firsthand knowledge of gender discrimination in my native country, I am more sympathetic to the feminist criticism directed against Kim Ki-duk’s alleged misogyny than to Tony Rayns’s outrage at Kim’s supposed lack of “authenticity” as an artist and his “undeserving” canonical standing as South Korea’s preeminent provocateur. From a feminist perspective, it is indeed problematic that the male-focalized class warfare is waged over the bodies of middle-class women in such films as Crocodile, Bad Guy, and 3-Iron. However, Kim’s oeuvre, which constitutes a visceral, bottom-to-top critique of social stratification in South Korea, cannot be fully grasped from a feminist perspective alone. As the Chinese American critic Ma Sheng-mei observes in his insightful essay on Kim’s films published in Asian Cinema, “Kim’s ritualization of violence dangles between sadomasochism that debases and reifies human beings and mysticism that negates [the] demarcation of human and nonhuman” (37–38). As Ma perceptively argues, Kim’s cinema centers on voiceless, traumatized, or sometimes bodiless “non-persons” who, regardless of their gender, are subject to various forms of unspeakable violence (be it physical, social, or sexual). It is true that many female characters in Kim’s films are beaten, raped, or coerced into prostitution. However, as the Korean film critic Kyung Hyun Kim argues, Kim Ki-duk’s films “are no more misogynistic than the Korean society itself that has adopted its masculine hegemonic values by fusing neoConfucian ethics and military rule and structure that stem from decades—if not centuries—of foreign occupation and martial violence” (135).

Moreover, Korean society does not have a monopoly on patriarchy and misogyny, for there have been numerous shocking depictions of sexual violence in the annals of world cinema (particularly in the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Imamura Shohei, Oshima Nagisa, and Miike Takashi), the likes of which far surpass anything that Kim’s tormented imagination has churned out. What is unique about Kim’s version of extreme cinema is the vivid nature of the psychological wounds apparent therein, caused by or leading to further violence, not violence in and by itself. The “extreme” nature of his films should not be misunderstood as merely a sensorial provocation or exploitative sleight-of-hand to “hook” the audience with repulsive images. Rather, it can be seen as a desperate (and desperately needed) exclamation point—a kind of corporeal exclamation point— emphasizing the excruciating pain suffered by abject heroes, who often serve as semiautobiographical portraits of the filmmaker himself.

Corporeal Effects: “Extreme Fishhook Penetration” and Transnational Canons

Although Kim Ki-duk is best known to mainstream Euro-American cinephiles for glossier, more meditative, modern Zen fables such as Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring and 3-Iron, an intense cult fandom for his brutal yopgi (translated as bizarre, grotesque, or horrific) aesthetics first sprang up with the 2000 release of The Isle, a psychological thriller set against the backdrop of a deceptively peaceful waterscape. One gruesome scene, in particular, in which the fugitive male protagonist swallows a ball of fishing hooks in an attempt to evade his anticipated capture by the police, led certain audience members to faint or vomit when shown in theaters worldwide, from Venice to New York, turning the little-known South Korean independent filmmaker into an overnight sensation and earning him a spot in international extreme film canons.

For the screenings of The Isle as a part of the 2001 New York Korean Film Festival at the Anthology Film Archives, the following disclaimer was advertised: “The Isle contains scenes of a graphic nature. Incidents, including fainting (see ‘Viewing Peril’ below), have occurred. Attend at your own risk. Management of the Anthology Film Archives cannot be held responsible” (“When Korean Cinema Attacks”). The tie-in “viewing peril” bulletin was taken from the 5 August 2001 issue of the New York Post and read, “Being a movie critic isn’t as easy as you might think. Joshua Tanzer ... found a scene in the Korean feature The Isle so disturbing, he blacked out during a screening at the Anthology Film Archives the other day.” In June 2004, the New Yorker retrospectively reported this notorious incident in a more graphic way: “The Isle contains ... ‘a moment of extreme fishhook penetration,’ and it was shortly after this part of the film that a critic emerged into the lobby, made a high-pitched gurgling noise, and passed out on the floor.... The story was reprinted in [The Post and] other newspapers, and soon The Isle acquired a reputation as the most dangerous movie around” (Agger 37).

Writing for the Village Voice, Michael Atkinson celebrates the sensorial audience participation induced by Kim’s gory aesthetics:

You’d have to look back to the theater-lobby barf-bag heyday of Night of the Living Dead, Mark of the Devil, and The Exorcist for this kind of fun. In every case, however, the ostensible trauma begins with the offscreen, or just vaguely glimpsed, suggestion of physical violation.... It’s refreshing to see that audiences are still vulnerable enough to lose their consciousness or their lunch thanks to a film, but thanks to what a film doesn’t show? That’s entertainment. (1)

Particularly noteworthy is Atkinson’s choice of two words: “fun” and “entertainment.” Kim’s films (with the exception of Bad Guy, which garnered 750,000 admissions) flopped one after another at the domestic box office precisely because they denied the kinds of fun and entertainment that middle-class moviegoers pursue, forcing them to confront the torturous, harsh realities of “non-persons” or subalterns living on the bottom rungs of Korean society. Choˇng Soˇng-il, one of the few Korean critics to consistently post favorable reviews of Kim Ki-duk since his debut, commented, “I become sad when I see a Kim Ki-duk film ... There are people who say they become angry. I wonder why. I do not intend to fight with them. But I do want to understand their anger. And I want them to understand my sadness” (Choˇng Preface). As Adrian Martin has written in the online Film-Philosophy Salon, “[Kim Ki-duk] is a director who evokes love and/or hate in viewers— certainly not indifference!” From the disdain and indignation of Tony Rayns to the amusement and exhilaration of Michael Atkinson, from the pathos and sympathy of Choˇng Soˇng-il to the outrage of Choˇng’s feminist counterparts, Kim’s emotive, visceral films have prompted diametrically opposing yet equally passionate reactions (whether positive or negative) from different viewers both at home and abroad.

In this respect, Kim’s visceral cinema can be read as an example of the “body genre” theorized by Linda Williams. According to Williams, there are three major body genres: (1) pornography, characterized by gratuitous sex and nudity; (2) horror films, characterized by gratuitous violence and terror; and (3) melodramas, characterized by gratuitous emotion and affect. Body genres prompt the body of the spectator to enact an “almost involuntary mimicry of the emotion or sensation of the body on the screen” (140–43). The New York Post’s critic Joshua Tanzer’s gagging and fainting at the Anthology Film Archives upon seeing the scene of “extreme fishhook penetration” in The Isle exemplifies the body genre’s powerful effects on the viewer’s body. The question is how to historicize this excessive corporeal performance (both onscreen and offscreen) in a specific geopolitical and cultural context. Williams’s psychoanalytically informed essay “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess” does not provide an answer to this question.

A Postcolonial Rationale for Violence

Let us now shift our attention to another infamous scene in Kim’s oeuvre so as to begin addressing this important inquiry. The scene in question is from Such’wiin pulmyoˇng [Address Unknown] (2001), which is set in a kijich’on (camptown) during the 1970s. The most overtly political and autobiographical of Kim’s films, Address Unknown centers on three social outcasts: (1) Chi-huˇm, an effeminate apprentice sketch artist who is habitually harassed by two high school bullies; (2) Euˇn-ok, Chi-huˇm’s love interest who has lost one eye to a childhood accident and ends up dating an American GI to receive an eye operation in the US military hospital; and (3) Ch’ang-guk, an ostracized halfblack assistant to a dog butcher who dates his ex-yanggongju (GI prostitute) mother. Comparable to two “gross out” scenes of self-inflicted flesh mutilation—involving the most sensitive body parts, the throat and the vagina—in The Isle, there are several shots and scenes in Address Unknown in which violence, both accidental and intended, is directed at the eye. Euˇn-ok gets a glass eye as a young girl when her brother’s makeshift gun misfires and sends a pellet into her optical tissues; Chi-huˇm hurts his own eye when his gun aimed at bullies misfires; and Ch’ang-guk’s eye is pierced when Euˇn-ok attacks it with a pencil upon his peeping through a hole in her door. The final and most traumatic eye injury occurs when James, Euˇnok’s neurotic GI boyfriend-gone-AWOL, visits her in a state of panic and attempts to violate her body.

When James tries to tattoo his name on the 18-year-old Korean girl’s bosom as a marker of his ownership, Euˇn-ok knifes her own cured eye in order to absolve her debt to the American GI and to end their abusive relationship once and for all. The subaltern woman’s masochistic act of violence shocks her neocolonial abuser, who flees the scene of crime in fear, only to be shot in his penis by avenging male archers. The eyegouging scene may seem to be another gratuitous yopgi moment of Kim’s cruel universe. However, its postcolonial significance cannot be overemphasized. As Cynthia Enloe asserts, “[n]one of these institutions—multilateral alliances, bilateral alliances, foreign military assistance programmes—can achieve their militarizing objective without controlling women for the sake of militarizing men” (Moon 11). Institutionalized prostitution and camptown-building indeed played significant roles in maintaining the US–ROK joint defense alliance during and after the Korean War. As a result, tens of thousands of Korean women not only have suffered a dual form of exploitation at the hands of both American soldiers and Korean pimps, but also have faced social ostracism for bearing mixed children and contaminating the “Korean race.” One case in particular—the brutal rape and murder in 1992 of barwoman Yun Kuˇm-i by Private Kenneth Markle (who stuffed two beer bottles into Yun’s womb, a cola bottle into her uterus, and an umbrella into her anus after killing her)—flamed nationwide rage and protests against the US military.

Euˇn-ok’s eye-knifing is a symbolic act of “speaking back” to the cruelty of the physical and mental violence committed by US military personnel against countless Korean women during and after the Korean War. James can finally see the atrocious nature of his own violence when Euˇn-ok fearlessly exhibits its mechanism, using her own eye as the target. Only then does he cower and turn away from his victim in shame. It should be noted that, though frequently directed at female bodies, excessive corporeal violence in Kim’s films is not gender-specific. Although it appears that Chi-huˇm and other Korean men have come to Euˇn-ok’s rescue belatedly and that they punish James by figuratively castrating him, Chi-huˇm is arrested for injuring an American GI and shot in his knee by a policeman (for resisting the transport to a prison) toward the film’s end. Although Ch’ang-guk habitually releases his frustration and anger by beating his mother and even cuts away his black father’s love mark (tattoo) from her breast, it is his demented mother who cannibalizes the son’s frozen body after his peculiar head-dive suicide in the wintry rice field. The mother immolates herself and her son’s remains shortly after this extreme act of necrophilic cannibalism.

Going into the production of Address Unknown, Kim Ki-duk posed the question, “Where does our cruelty come from?” (Lee). He apparently found a partial answer in Korean modern history itself, punctuated with many violent ruptures, including national division, civil war, and Cold War military confrontations—themes that recur in a few of his other films, such as Wild Animals (depicting a friendship between a South Korean street artist and an AWOL North Korean solider exiled in Paris) and The Coast Guard (set along the heavily armed coastal border between the two Koreas). The extremity of Kim’s cinema should not—indeed, cannot—be divorced from its historical and social context.

Kim’s cinema creates an allegorical (and often fantastical) space where men and women from different class backgrounds encounter one another and reconcile their antagonisms. As discussed earlier, an unlikely yet redemptive romantic union between a college student– turned–prostitute and a brothel hoodlum who is responsible for her downfall is what drives the narrative progression of Bad Guy. An extraordinary friendship develops between a resident prostitute in a provincial inn and her boss’s daughter (who, in place of her sex worker friend, sleeps with a customer one night) in Paran taemun [Birdcage Inn] (1998). A middle-class high school girl (whose father is a cop) helps her best friend, a destitute teenager, earn pocket money through online prostitution in Samaritan Girl. These relationships may not be realistic in a conventional sense, but they, along with several other metaphysically imbued moments in Kim’s cinema, suggest faint yet discernible hopes of interclass communication, against all odds and despite social prejudices.

Reconciling the Paradox of Silence and Apologia

As many observers have noted, silence is a recurring motif in Kim Ki-duk’s cinema. According to the French critic Cédric Lagandré, Kim’s films hinge on “the impossibility of language itself: impossibility, consequently, of adapting to the social world, of polishing one’s vices, of softening them through relationships with fellow humans” (60). Lagandré goes on to state,

Because of that original wound, because of those “unkept promises,” about which Kim Ki-duk repeats in his interviews that they are the origin of all violence ... everybody withdraws into a stubborn silence.... “The characters in my films are not mute,” said Kim Ki-duk. “They just don’t believe in verbal communication.” It is not that they cannot speak, it’s that they don’t want to speak. They are not silent through the inability to speak, but through the inability to believe in words. (67)

Like his characters, Kim withdrew into a “stubborn silence” after being hurt by words (particularly those by unsympathetic critics) and exhausted from defending his films, controversy after controversy.

In August 2006, Kim Ki-duk broke his nearly two-year media silence and held a press conference arranged by Sponge, the Korean distributor of his film Time, produced by the Japanese company Happinet Pictures.[12] This otherwise uneventful thirty-minute publicity gig for a small art film generated an unexpected scandal when two comments by Kim Ki-duk were sensationalized by the media and Web communities. First, when asked about his opinion on the success of the megablockbuster Koemul [The Host] (2006), which had opened in an unprecedented 620 theaters and would become the highest-grossing domestic film of all time, Kim ambiguously described the phenomenon as “a perfect meeting between the level of Korean audience and the level of Korean cinema” (Paquet, “Helmer Ignites” 16). Second, in an outburst of frustration over considerably lower admissions for his films in South Korea (as opposed to North America and Europe),[13] the director suggested that he might stop “exporting” his films to South Korea should Time sink at the box office. These angst-ridden statements should be contextualized in the oligopolistic market conditions of the Korean film industry, wherein the “Big Three” investor-distributorexhibitor majors (CJ-CGV, Showbox-Megabox, and Lotte Entertainment-Cinema) dominate approximately 60 percent of the total market share, driving independent art films such as Kim’s into near extinction (Howard 94). (Mis) interpreting Kim’s remarks as a sign of his condescension and hostility toward Korean audiences, however, thousands of netizens posted invectives against the director in cyberspace discussion boards and chatrooms.[14]

The public frenzy led to the issuance of Kim Ki-duk’s official apology to the production crew of The Host as well as to national audiences, one that was e-mailed to major South Korean media institutions. In his statement, Kim evaluates his films in a sarcastic, self-deprecating way:

My movies are lamentable for uncovering the genitals that everyone wants to hide; I am guilty for contributing only incredulity to an unstable future and society; and I feel shame and regret for having wasted time making movies without understanding the feelings of those who wish to avoid excrement ... I apologize for making the public watch my films under the pretext of the difficult situation of independent cinema, and I apologize for exaggerating hideous and dark aspects of Korean society and insulting excellent Korean filmmakers with my works that ape art-house cinema but are, in fact, self-tortured pieces of masturbation, or maybe they’re just garbage. Now I realize I am seriously mentally-challenged and inadequate for life in Korea. (Jamier)

Kim’s choice of extreme vocabulary such as “excrement,” “garbage,” and “mentally challenged” once again captured the media’s attention, granting the director an unprecedented amount of publicity. Several domestic critics reacted to the apology in a cynical way. For example, Soˇng Uˇn-ae confides, “It’s uncertain where the sincerity in Kim Ki-duk’s radical masochism ends and where the ridicule of audiences or his ‘performance’ begins” (317). What Soˇng fails to consider is the irony of apology in which Kim defines himself and his films from the perspective of his worst detractors. The whole situation is uncannily reminiscent of several scenes in Kim’s films where outlaw protagonists are pressed to apologize for or confess their sins by social elites.

Take the notorious six-minute opening sequence of Bad Guy, for instance. A quintessential Kim hero played by Cho Jae-hyoˇn (referred to by Tony Rayns as “the De Niro to Kim’s Scorsese”) sluggishly enters the heart of Seoul’s commercial district, Myoˇngdong. In front of the upscale Lotte Department store, the only thing that this lowlife thug dressed in black can afford to eat is a skewer of processed fish meat, purchased from a makeshift food stand. While navigating passersby on the street, Cho’s character (Han-gi) spots a beautiful college girl (Soˇn-hwa) in a blue polka dot dress and a white cardigan sitting on a department store bench, a member of the middle class clearly beyond his reach. Nevertheless, Han-gi approaches the bench and sits awkwardly by her side as if demanding equal standing.

After telephoning her boyfriend, for whom she is waiting, Soˇn-hwa notices the presence of this stranger sitting beside her and moves to an adjacent bench, disgust etched on her face. After her boyfriend arrives, the college couple avoids Han-gi, glancing derisively at him. Only when the unwelcome intruder walks away does the couple begin to feel at ease. Provoked by their innocent yet mindless sweet-nothings, Han-gi turns back and snatches Soˇn-hwa, planting a forceful kiss on her lips. The boyfriend intervenes, banging Han-gi’s body with a nearby garbage can and punching him in the face. An enraged Soˇn-hwa stops Han-gi when he starts to withdraw, barking at him, “Where are you going? Apologize! In front of everybody.” Emerging from the crowd that begins to circle around, three marines block the way of Hangi’s exit. They order, “Apologize to the lady.” When Han-gi resists, the marines gang up and beat him, calling him a “gangster.” The marines force the bloody culprit to kneel down in front of the insulted college girl and demand that he apologize. As the defiant offender continues to remain silent, Soˇn-hwa spits on him, calling him “a crazy bastard.” After the crowd dissipates from the scene of the spectacle, Han-gi turns his face to the side, at 90 degrees, displaying his profile on the left side of the frame. The film title, “Bad Guy,” appears next to the frozen close-up of the socially branded outlaw.

This confrontational opening is reminiscent of a passage from Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, in which the Martinique-born philosopher describes the psychology of the dominated native in colonial society:

The look that the native turns on the [white] settler’s town is a look of lust, a look of envy; it expresses his dreams of possession—all manner of possession: to sit at the settler’s table, to sleep in the settler’s bed, with his wife if possible. The colonized man is an envious man. And this the settler knows very well; when their glances meet he ascertains bitterly, always on the defensive, “They want to take our place.” (39)

Although the class antagonism depicted in the aforementioned scene may appear to be distinct from the racially mediated colonial tensions elaborated in Fanon’s treatise, the mise-en-scène of Kim’s film symbolically encodes Han-gi’s character as a “black man,” an internally colonized subject who belongs to “the Negro village, the medina, the reservation ... a place of ill fame, peopled by men of evil repute.” His encroachment on the “well-fed town, an easygoing town ... always full of good things” (Fanon 39), is rendered an unpardonable offense. However, what is more threatening is his envy and ressentiment, his insolent desire to look at and possess the other man’s girlfriend. Not unlike the colonial power structure explained by Fanon, postcolonial South Korean society can be characterized by the decades-long collusion between militaristic, educational, and capitalistic powers, together exerting a hegemonic hold on the populace. As such, the soldiers intervene to safeguard privileged members of the consumption-driven middle class who possess both material and cultural capital. Seen from the subaltern perspective, the arrogance of the college girl (who forces an underclass man to speak despite his throat injury) partially justifies his vengeful scheme to bring her down to his depressed station in life. Despite his despicable act of luring Soˇn-hwa into the world of prostitution, Han-gi is no ordinary “bad guy.” Not only does he display remorse and agony in witnessing Soˇnhwa’s degradation, but he is also altruistic and self-sacrificial in protecting his underlings (he voluntarily goes to prison for the murder committed by Choˇng-t’ae and buries a knife after being stabbed with it by a jealous Myoˇng-su, in order to eliminate evidence of his own murder).

Kim’s cinema puts forth a unique variation of the oppressed subaltern who, according to the postcolonial critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “cannot be heard or read ... [and] cannot speak” (104). Significantly, Kim’s muted subaltern characters can but will not speak, as is the case for T’ae-soˇk of 3 Iron, a harmless housebreaker who remains silent despite the repeated beating of a police officer who attempts to extract a false confession of rape. The same goes for Huˇi-jin of The Isle, a gatekeeper of a remote fishing resort who, after sexually servicing one of the customers, refuses to humor him verbally in exchange for a big tip. In both cases, subaltern characters—a homeless man and a part-time sex worker, respectively— challenge the authority of the dominant class by not speaking what others wish to hear from them (and by extension, not speaking at all, to the consternation of their impatient listeners).

Silence connotes not only subaltern resistance in the face of military or police brutality (distantly evoking the political dissidence and martyrdom of the 1970s and 80s) but also Kim Ki-duk’s own mistrust of language-based discourse and the signifying systems that are controlled and manipulated by members of the intelligentsia (including journalists). Indeed, it is not difficult to discern a parallel between the filmmaker and his silent protagonists such as Han-gi and T’ae-soˇk, rebels with hearts of gold who are mistaken as “bad guys” as a result of their provocative actions and unapologetic demeanors. Unlike his muted characters who maintain their silence in the face of violent force, Kim caved in and spoke. He apologized publicly, an act demanded repeatedly of his alter-ego Han-gi in the opening sequence of Bad Guy. Through his “extreme” words of masochism and apologia, however, Kim Ki-duk turned the tables and exposed the cruelty of his persecutors. In his editorial for Chosoˇn Ilbo [Chosun Daily], the musician Sin Tae-ch’oˇl correctly interprets Kim’s apology as a “masochistic act of resistance against mass lynching directed against him.” Sin goes on to warn against the culture of collective violence directed toward a nonconforming minority.

In his interview with Darcy Paquet, Kim Ki-duk elaborates on the authorial intentions of his cinema: “It’s not my purpose to offend people, but the things I show in my films are genuine problems in our society. If mainstream society distances itself from the class of people I show in my films, it will only cause deeper conflicts. With my films, I want to help both sides understand each other” (Paquet, “Close Up” 14). Kim’s films can indeed promote interclass communication, but only when it is embraced by an open-minded audience. As Kim So-hee puts it, “What Kim Ki-duk truly longs for is a gentle touch that will soothe his ragged inner world, yet keep his spirit intact. Sincere criticism along with encouragement from the heart.” Like the silent protagonist of Breath, a prisoner on death row (played by the Taiwanese actor Chang Chen) who is visited by a kind-hearted stranger (an unhappily married, middle-class woman with whom the inmate bonds spiritually), Kim Ki-duk is awaiting a sympathetic audience who can recognize the vulnerable and innocent soul beneath the surface of his “extreme” cinema.

hye seung chung is assistant professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is the author of Hollywood Asian: Philip Ahn and the Politics of Cross-Ethnic Performance (Temple UP, 2006). Her scholarship on Korean cinema has been published in such journals and anthologies as Asian Cinema, Film and Philosophy, South Korean Golden Age Melodrama, New Korean Cinema, and Seoul Searching. She is currently completing a manuscript on the films of Kim Ki-duk for the University of Illinois Press’s Contemporary Film Directors series.

Notes

A shorter version of this article was presented in the “‘Extreme’ East Asian Cinema and Cult Film Canons” panel that I chaired for the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Chicago, 8–11 March 2007. I wish to thank my fellow panelists (Ch-Yun Shin, James Fiumara, and Ruby Cheung) as well as audience members who shared their enthusiasm for “extreme” cinema. I am also indebted to David Scott Diffrient who watched Kim Ki-duk’s films with me and shared many insights and ideas.

References

Agger, Michael. “Gross and Grosser.” The New Yorker 28 June 2004: 37. Print.

Atkinson, Michael. “Ace in the Hole.” Village Voice 21–27 Aug. 2002: 1. Print.

Bernstein, Michael A. Bitter Carnival: Ressentiment and the Abject Hero. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1992. Print.

Bowles, M. J. “The Practice of Meaning in Nietzsche and Wittgenstein.” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 26 (2003): 12–24. Print.

Chocano, Carina. “Love among Ruins.” Los Angeles Times 1 Apr. 2005: E-6. Print.

Choˇng, Soˇng-il, ed. Kim Ki-duk: yaseang hok uˇn sokjaeyang [Kim Ki-duk: A Wild Life or Sacrificial Lamb]. Seoul: Haengbok han ch’aek ilgi, 2003. Print.

Chow, Rey. Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. New York: Columbia UP, 1995. Print.

Chu, Yu-sin. “Kuˇ uˇi yoˇnghwa nuˇn yoˇsoˇng ae taehan t’eroˇda” [“His Film Is Terror to Women”]. Cine 21 22 Jan. 2002: 34–35. Print.

Chu Soˇng-ch’oˇl. “Kim Ki-duk Sigan Kijahoegyoˇn

Chisangjunggae” [Broadcasting Kim Ki-duk’s Time Press Conference]. Film 2.0 15–22 Aug. 2006: 8. Print.

“Extreme Cinema.” Wikipedia. Web. 15 May 2009. <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extreme_cinema>.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 1963. Print.

Howard, Chris. “Contemporary South Korean Cinema: ‘National Conjunction’ and ‘Diversity.’” East Asian Cinemas: Exploring Transnational Connections on Film. Ed. Leon Hunt and Leung Wing-Fai. London: I. B. Tauris, 2008. 88–102. Print.

Jamier, Samuel. “The Strange Case of Director Kim Ki-Duk: The Past, the Persistent Problems and the

Near Future.” The Korean Society, n.d. Web. 12 May 2009. <www.koreasociety.org/table/film_blog>.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema. Durham: Duke UP, 2004. Print.

Kim, So-hee, “Interview & Biography.” Kim Ki-duk, from Crocodile to Address Unknown. Ed. Lee Haejin. Seoul: LJ Film, 2001. Print.

Lagandré, Cédric. “Spoken Words in Suspense.” Kim Ki-duk. Paris: Dis Voir, 2006. 59–93. Print. Leong, Anthony C. Y. Korean Cinema: The New Hong Kong. Victoria, Canada: Trafford, 2003. Print.

Ma Sheng-mei. “Kim Ki-duk’s Non-Person Films.” Asian Cinema 17.2 (Fall/Winter 2006): 32–46. Print.

Martin, Adrian. “Re: Kim Ki Duk.” 15 Feb. 2007. Message to the Film-Philosophy Salon discussion list. E-mail. 15 May 2009.

MoMA Exhibitions 2008. Web. 15 July 2008. <www.moma.org/visit/calendar/films/597>.

Moon, Katharine. Sex among allies: Military Prostitution in U.S.–Korea Relations. New York: Columbia UP, 1997. Print.

Nealon, Jeffrey T. “Performing Resentment: White Male Anger; or, ‘Lack’ and Nietzschean Political Theory.” Why Nietzsche Still? Reflections on Drama, Culture, and Politics. Ed. Alan D. Schrift. Berkeley: U of California P, 2000. 274–92. Print.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morality. Rev. student ed. Trans. Carol Diethe. Ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.

Paquet, Darcy. “Close Up: Kim Ki-duk.” Screen International 1353 (19–25 Apr. 2002): 14. Print.

———. “Helmer Ignites ‘Time’ Tussle.” Variety 28 Aug. 2006: 16. Print.

Rayns, Tony. “Sexual Terrorism: The Strange Case of Kim Ki-duk.” Film Comment 40.6 (Nov./Dec. 2004): 50–52. Print.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988. Print.

Shaw, George Bernard. Pygmalion. New York: Washington Square, 1973. Print.

Shin, Chi-Yun. “Art of Branding: Tartan ‘Asia Extreme’ Films.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media <www.ejumpcut.org/currentissue/TartanDist/index.html#n>.

Sin Tae-ch’oˇl. “Lynching Kim Ki-duk Is Collective Violence” [“Kim Ki-doˇk ttaerigi nuˇn tasu uˇihoengp’o”]. Chosun Daily [Chosoˇn Ilbo]. 30 Aug. 2006. Web. 15 May 2009.

Slater, Ben. “Tony Reigns.” Harrylimetheme. 26 Nov. 2004. Web. 1 Mar. 2007 <harrylimetheme.blogspot.com/2004/11/tony-reigns.html>.

Smith, Damon. “The Bad Boy of Korean Cinema.” The Boston Globe 1 May 2005: N9. Print.

Soˇng, Uˇn-ae. “The Host and Kim Ki-duk: Beyond the Monstrous Dialectics” [“Koemul kwa Kim Ki-doˇk: Kuˇ koemul kat uˇn taehang uˇl nuˇmoˇ”]. Criticism [Pip’yoˇng] 13 (Winter 2006): 310–23. Print.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. Ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. New York: Columbia UP, 1994. 66–111. Print.

Stephens, Chuck. “3 Iron.” Cinema Scope 22 (June 2005). Web. 1 Mar. 2007 <www.cinema-scope.com/cs22/cur_stephens_iron.htm>.

Stringer, Rebecca. “‘A Nietzschean Breed’: Feminism, Victimology, Ressentiment.” Why Nietzsche Still? Reflections on Drama, Culture, and Politics. Ed. Alan D. Schrift. Berkeley: U of California P, 2000. 247–73. Print.

Walsh, Mike. Book review of New Korean Cinema. Screening the Past. Mar. 2007. Web. 30 July 2008. <www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/19/new-korean-cinema.html>.

“When Korean Cinema Attacks: New York Korean Film Festival 2001.” Subway Cinema. Aug. 2001. Web. 1 Mar. 2007. <www.subwaycinema.com/kfest2001/theisle.htm>

Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Film Genre Reader II. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: U of Texas P, 1995. 140–58. Print.

[1] Although it is unclear when and by whom the critical term “extreme cinema” was first coined, at least in the context of marketing Asian cinema, credit should be given to Hamish McAlpine, the founder and proprietor of the now-defunct UK-based Tartan Films, who created the popular “Asia Extreme” brand at the end of 1999 and subsequently distributed numerous Asian horror films, thrillers, and erotica to European and North American markets. This continued until his company’s bankruptcy in the summer of 2008. For detailed information about the Tartan Asia Extreme line of DVDs, see Shin, “Art of Branding.”

[2] No other Korean filmmaker has received such a degree of commercial representations in the North American market. After Kim, Park Chan-wook ranks a distant second, with five of his eight features (Kongdong kyoˇngbi kuyoˇk [Joint Security Area] [2000], the films comprising his “vengeance trilogy,” and Pakjwi [Thirst] [2009])available on DVD in the United States.

[3] Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring garnered 370,000 admissions stateside alone, grossing $2.4 million for distributor Sony Pictures Classics

[4] Prior to the MoMA retrospective, there had been a couple of European retrospectives devoted to Kim Ki-duk: the 2002 Etrange Film Festival in Paris and the 2002 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. According to a report issued by the Korean Film Council (KOFIC), the government-subsidized organization receives more overseas requests for assistance with Kim Ki-duk retrospectives than all other Korean filmrelated events combined (Rayns 50).

[5] Although various Korean studies programs in US college campuses have held retrospectives on important Korean directors (Im Kwon-taek [Im Kwoˇn-t’aek], Lee Myung-se [Yi Myoˇng-se], Park Kwang-su, Hong Sang-soo [Hong Sang-su], etc.), and although the Museum of Modern Art introduced selective works of Shin Sang-ok, Yu Hyoˇn-mok, and Im Kwon-taek under the title “Three Korean Master Filmmakers” in 1996, a complete MoMA retrospective of Kim Ki-duk’s fourteen films is an unprecedented honor in terms of its scope and prestige.

[6] A number of American film scholars have confided to me their newfound admiration for Korean cinema after viewing Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring and 3-Iron. A majority of the University of Michigan students who took my contemporary East Asian cinema course in the spring semester of 2006 selected the latter film as their favorite class screening over such canonical titles as Zhang Yimou’s Jou Dou (1990), Chen Kaige’s Ba wang bie ji [Farewell My Concubine] (1993), Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Hao nan hao nu [Good Men, Good Women] (1995), and Wong Kar-wai’s Chun gong cha sit [Happy Together] (1997). In this and other classes, many American college students from diverse cultural and racial backgrounds expressed their interest in the films of Kim Ki-duk and chose to write about them in their paper assignments.

[7] In his book Korean Cinema: The New Hong Kong, Anthony C. Y. Leong argues, “South Korea is even being likened to the new ‘Hong Kong,’ with its homegrown film industry on the verge of exploding onto the world stage, similar to how ‘Hong Kong New Wave’ catapulted the former British colony and its groundbreaking directors into the international spotlight” (2). Recapitulating the term in his online book review of New Korean Cinema, Mike Walsh states that “the startling factor in the success of recent Korean film has been not only the growth of domestic box office, but the exponential growth in export sales, particularly throughout East Asia. Truly, Korea is the new Hong Kong in this respect.”

[8] For detailed information about Kim Ki-duk’s life, see Kim So-hee. There is a connection between Kim’s films (the scripts for which the director wrote) and his life. Much like one of the characters in Address Unknown, Kim grew up fearing his authoritarian father (a Korean War veteran with gunshot wounds), had an Amerasian friend, and was bullied by village thugs. In his twenties, he served five years in the marines. During his service, Kim Ki-duk was wrongly court-martialed for failing to report a North Korean spy ship (in place of his superior who was responsible) and detained in a military prison for months. This experience served as the basis for the narrative in The Coast Guard. At the age of twenty-eight, he finished his military service and spent two years at a church for the visually impaired with the intention of becoming a preacher. Religious overtones in his films Bad Guy, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring, and Samaritan Girl are indebted to this pious period of Kim’s youth. In 1990, cashing in on his savings, Kim flew to Paris and spent three years in Europe as a sidewalk artist making a living from sketching portraits, like the characters in Wild Animals and Real Fiction do. Kim is reported to have seen his first film in Paris at the age of thirty-three. Having been inspired by such films as Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Leos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont-Neuf [The Lovers on the Bridge] (1991), he took up screenwriting after returning to South Korea. With no academic or professional training in filmmaking, Kim was able to debut as a director due largely to the fact that his early scripts (Painter and Prisoner, Illegal Crossing) won prizes from KOFIC.

[9] The admissions for Wild Animals fell short of 5,400, a slight increase from 3,300 for Crocodile, his debut feature released a year prior.

[10] Exemplified by antiheroes in the literary works of Diderot, Dostoevsky, and Céline as well as the real-life serial killer Charles Manson, the abject hero is both victim and murderer, “servile and satanic.” According to Michael A. Bernstein, “abjection could lead directly to ressentiment embittered enough to erupt into murder” (9). Many of Kim Ki-duk’s heroes are likewise criminals of some sort (murderers, rapists, gangsters, etc.) who are themselves victims of circumstance and who often invoke our sympathy.

[11] Kim Ki-duk confesses to his lifelong inferiority complex in his interview with the journalist Kim Kyoˇng: “Since our society’s elite class consists of those who graduate from college and find employments in such conglomerates as Hyundai and Samsung, my undereducated background prevented me from even submitting applications for decent jobs” (Choˇng 47).

[12] Kim Ki-duk had initially given up the Korean release of Time, which was being exported to thirty countries. A netizen signature-gathering movement demanding the release of Time in South Korea was partly responsible for Sponge’s purchase of the film’s Korean distribution rights.

[13] Kim Ki-duk stated in the press conference, “I hope that 200,000 people will come see [Time in South Korea]. More than 300,000 American moviegoers saw Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring. And 3 Iron was seen by 200,000 in France and another 200,000 in Germany. My mind [about the Korean market] might change if domestic admissions [for Time] exceed 200,000” (Chu Soˇng-ch’oˇl 8.) Despite the media frenzy surrounding the director around the time of its release, Time’s Korean admissions fell short of 30,000.

[14] The situation became aggravated when Kim appeared on a television panel (MBC’s 100 Minutes Special) debating the screen monopoly on August 17, eleven days after the controversial press conference. In this rare TV appearance, Kim defended himself from the online attacks and restated his controversial remark about The Host.