Ian Cunnison & Wendy James

Essays in Sudan Ethnography Presented to Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard

I. Southeastern Nuba Age Organisation

The formal age-group structure

Age and the organisation of production

Age-group recruitment and group function

Relations between sets, internal set solidarity, relative age behaviour

II. The Politics of Rain Control Among the Uduk

III. Residence Among the Berti

IV. The Bovine Idiom and Formal Logic

V. Proverbs and Social Values In a Northern Sudanese Village

VI. Blood Money, Vengeance and Joint Responsibility: The Baggara Case

VII. Political Inequality in the Kababish Tribe

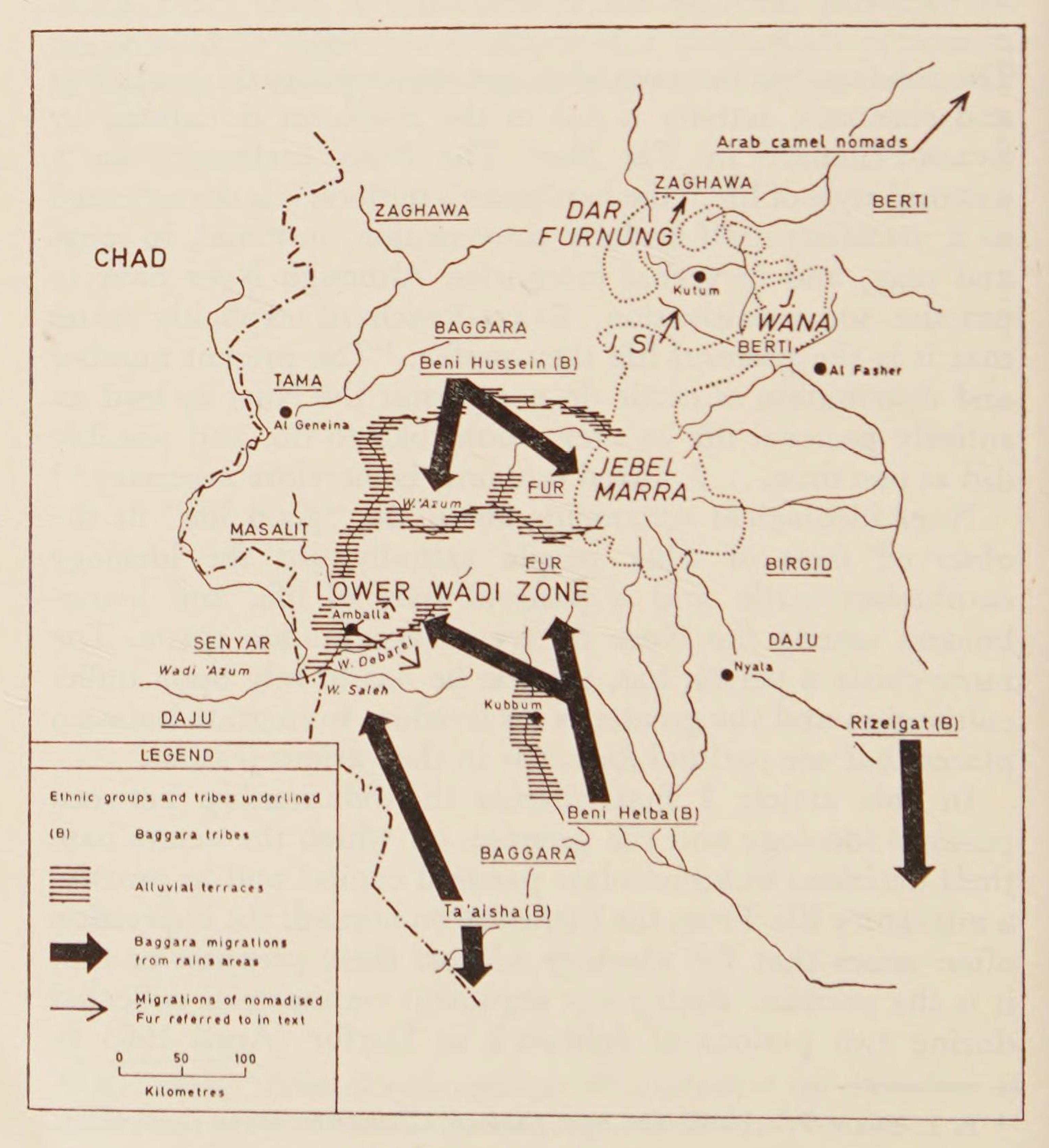

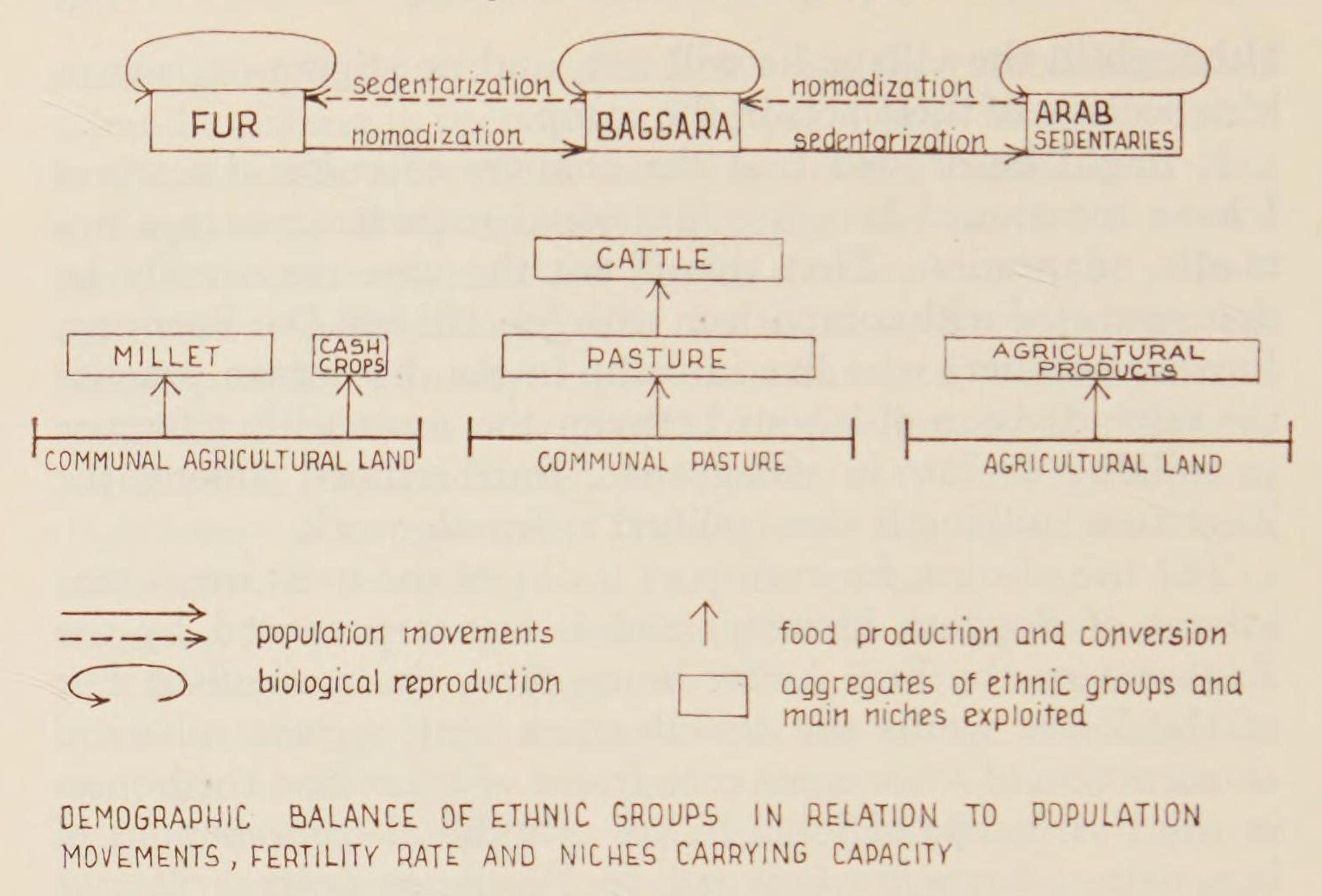

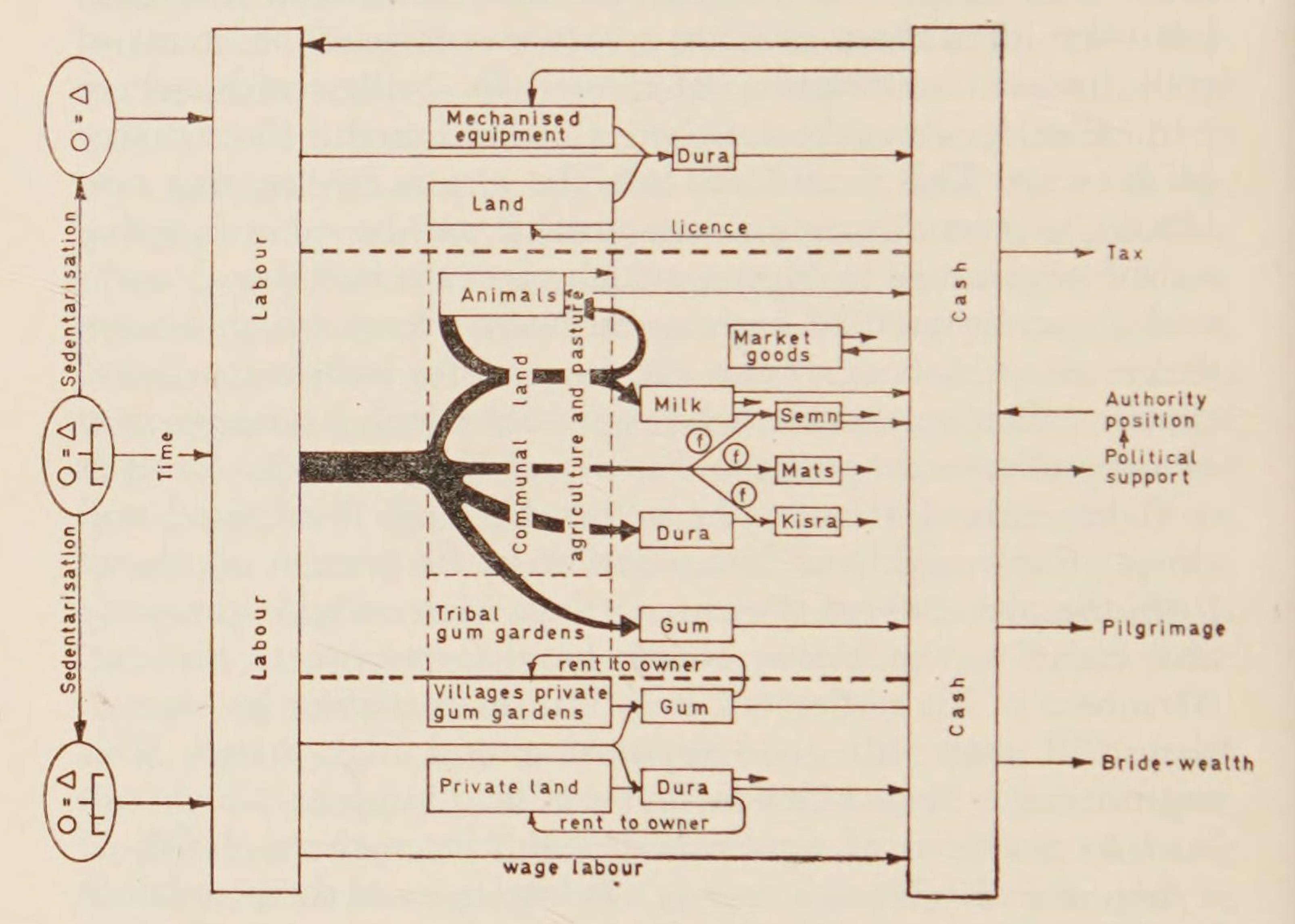

VIII. Nomadisation as an Economic Career Among the Sedentaries In the Sudan Savannah Belt

The tribe and its seasonal migration

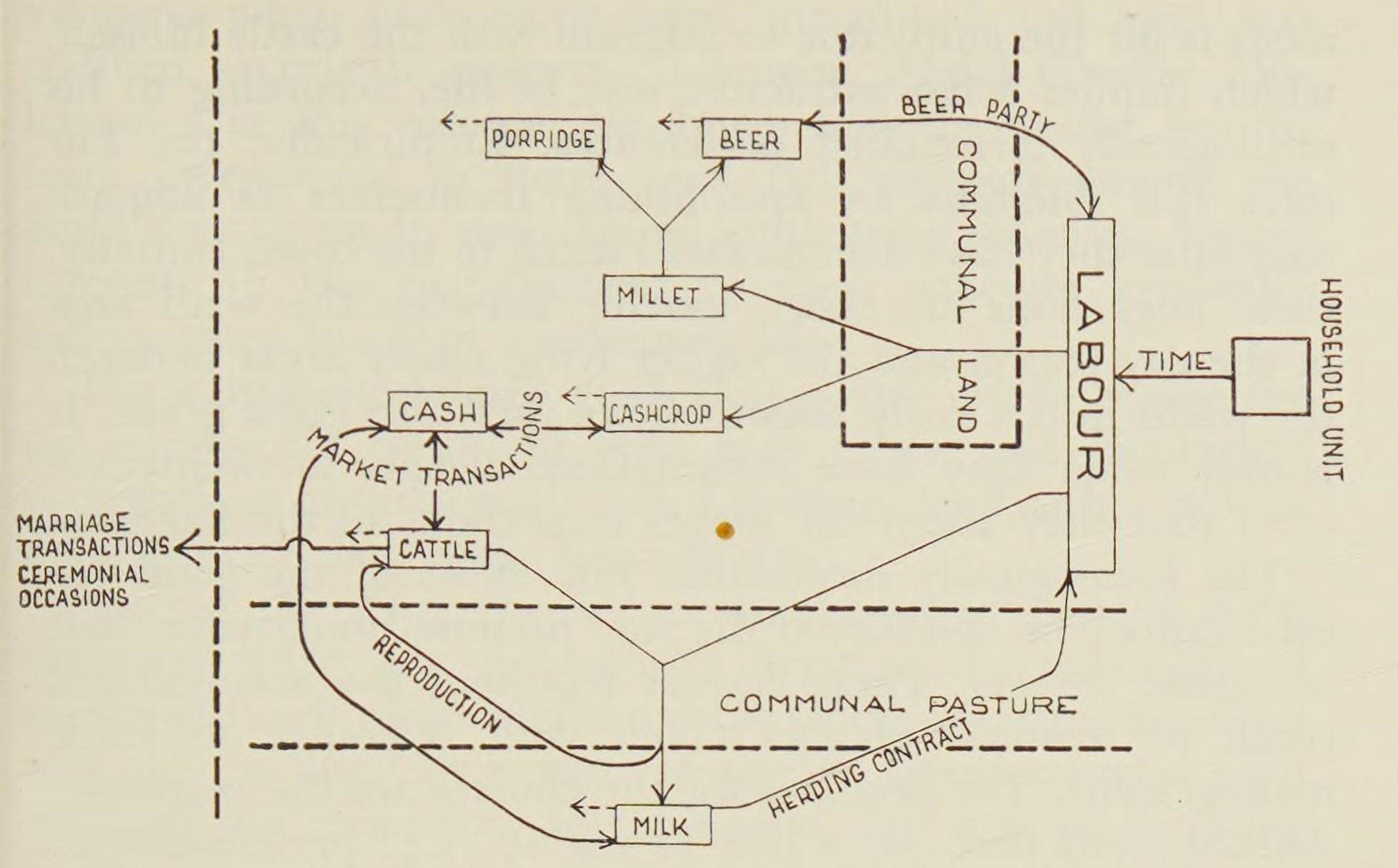

The economic unit, resources and division of labour

Building of capital and allocation of time

X. A Rotating Credit Association in the Three Towns

XI. Social Characteristics Of Big Merchants and Businessmen in El Obeid

XII. The Jamutya Development Scheme: An Essay on the Utility of ‘Instant Anthropology’

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

Essays in

Sudan

Ethnography

presented to

Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard

edited by Ian Gunnison and Wendy James

Humanities Press

New York

[Copyright]

Published in the United States of America

by Humanities Press, Inc.

© 1972 C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.

SBN 391 — 00246 — 5

51644

Printed in Czechoslovakia, by Statni tiskArna, Prague

[Royalties]

Royalties from the sale of this volume will be contributed to the Ioma Evans-Pritchard Scholarship Fund, at St. Anne’s College, Oxford, which was established in memory of the wife of Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard. Its purpose is to support continuing research in the social anthropology of Africa.

Contents

FOREWORD

EDITORS’ NOTES

I. Southeastern Nuba Age Organisation

by James C. Faris

II. The Politics of Rain Control among the Uduk

by Wendy James

III. Residence among the Berti

by L. Holy

IV. The Bovine Idiom and Formal Logic

by A. and W. Kronenberg

V. Proverbs and Social Values in a Northern Sudanese Village

by Ahmed S. al-Shahi

VI. Blood Money, Vengeance and Joint Responsibility: the Baggara case

by Ian Gunnison

VII. Political Inequality in the Kababish Tribe

by Talal Asad

VIII. Nomadism as an Economic Career among the Sedentaries of the Sudan Savannah Belt

by Gunnar Haaland

IX. The Rufa’a al-Hoj Economy

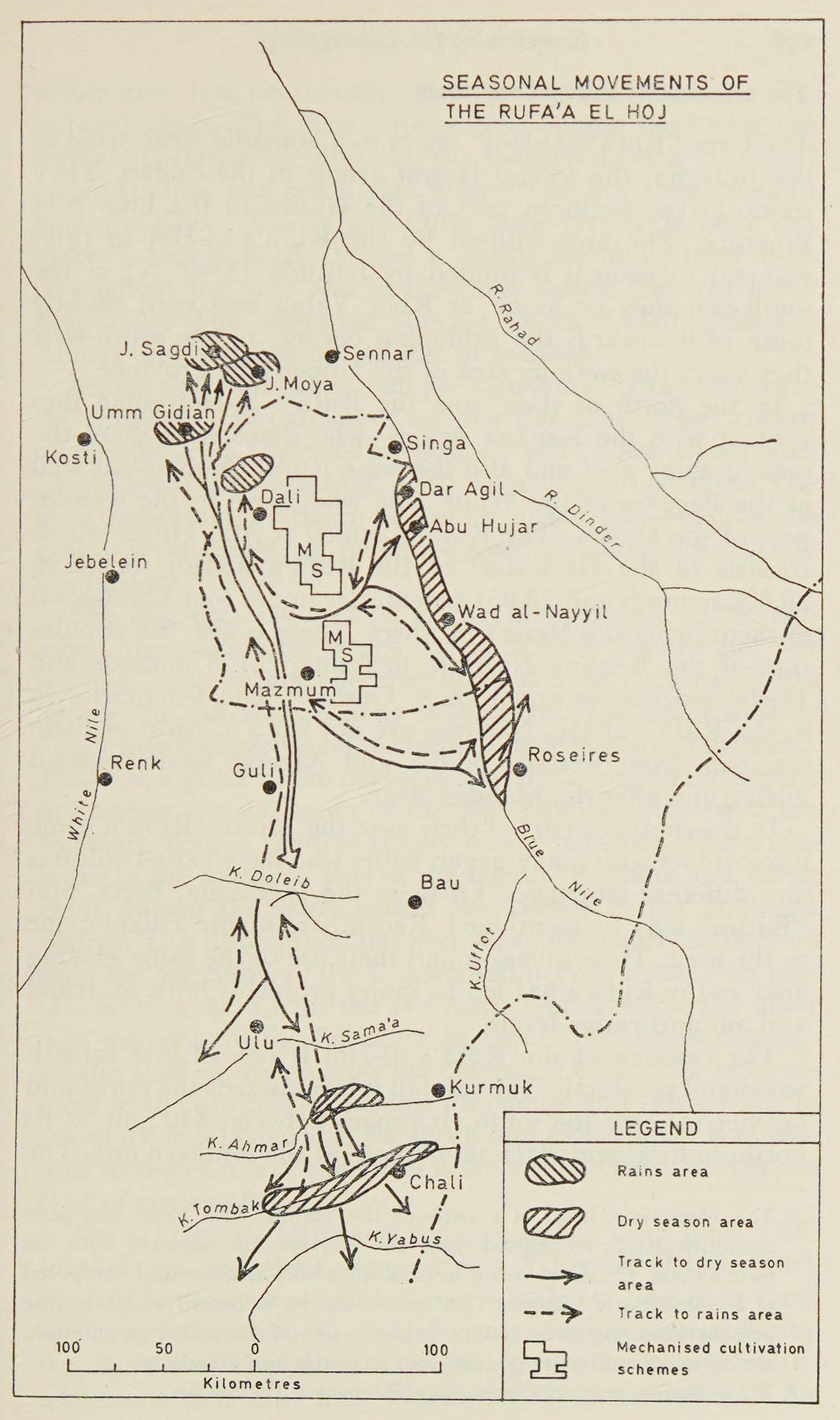

by Abdel Ghaffar Mohammed Ahmed 173

X. A Rotating Credit Association in the Three Towns

by F. Rehfisch

XI. Social Characteristics of Big Merchants and Businessmen in El Obeid

by Taj al-Anbia AH al-Dawi 201

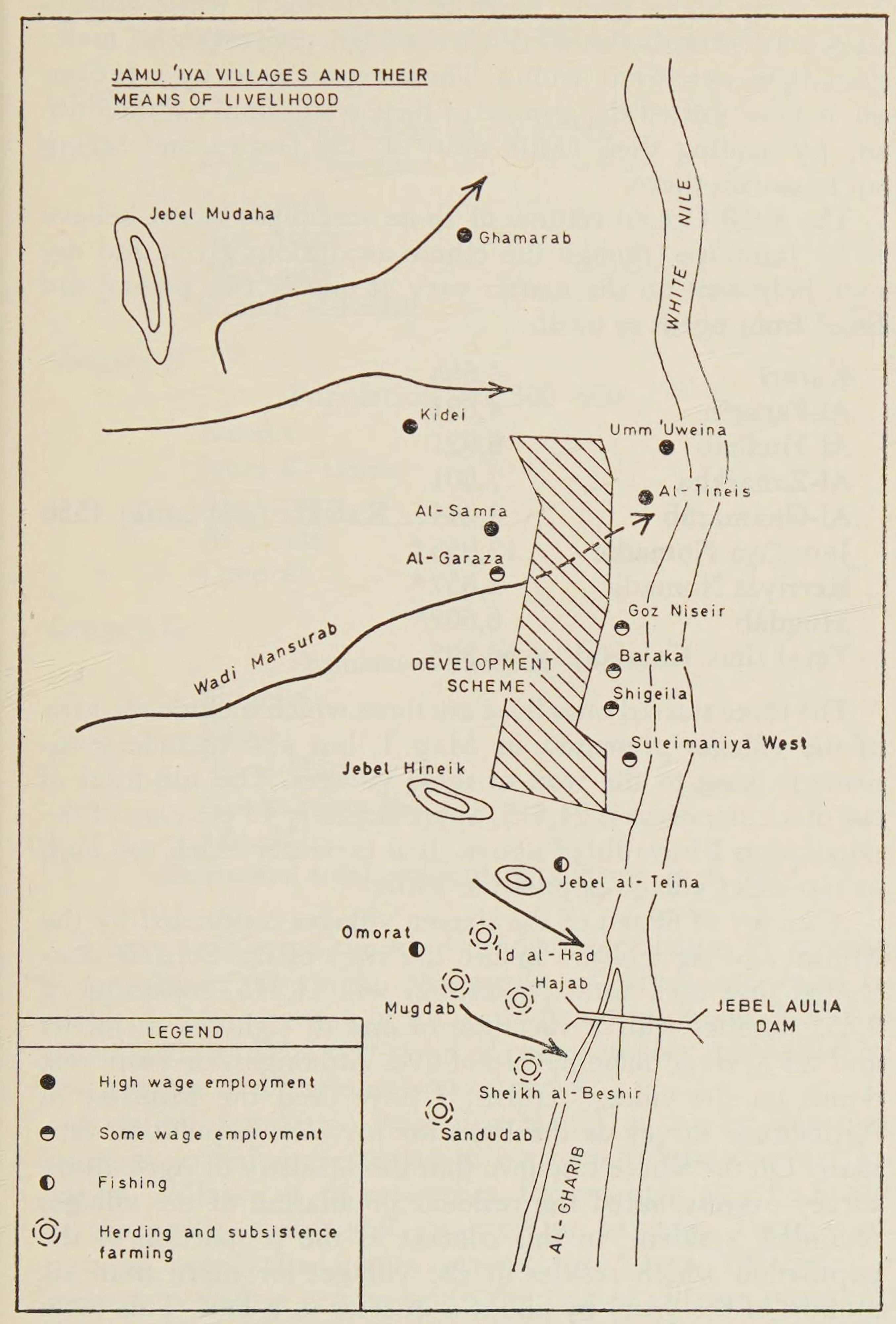

XII. The Jamu’iya Development Scheme: an essay in the utility of ‘Instant Anthropology’

by Peter Harries-Jones 217

REFERENCES

INDEX

Foreword

In 1926, E. E. Evans-Pritchard arrived for the first time in the Sudan, after studying under Professors Seligman and Malinowski at the London School of Economics. He was to carry on the ethnographic survey work initiated by Charles and Brenda Seligman for the Sudan Government. Between 1909 and 1912, the Seligmans had visited the Nuba mountains, the Kababish Arabs and the Beja, and in 1921–2 they had carried out investigations in the south. But they were unable to complete their fieldwork because of illness. Their research had already been accepted as valuable, not only in academic terms but also in a practical way to the administrators of the Sudan. The Sudan Government, and in particular Sir Harold MacMichael, Civil Secretary (1926–34), were sympathetic to this type of field enquiry, and therefore gave Evans-Pritchard every support in his work. Although his subsequent research covered at various times parts of Libya, Egypt, Syria, Ethiopia, the Congo and Kenya, the major body of his field work was carried out between 1926 and 1936 in the Sudan. The Sudan material is a rich source of ethnographic information, published in seven books and over 150 articles. These writings, together with the later study of the Bedouin of Cyrenaica, form the basis of Evans-Pritchard’s world-wide standing in social anthropology, and have attracted the attention of philosophers, psychologists, historians, political scientists and economists.[1]

To indicate adequately the importance of Professor Evans-Pritchard’s work would be impossible here, and we are not attempting to do so. But we feel it might be of interest to give a brief chronological outline of his various Sudan expeditions, based on published material. This fieldwork record is in itself an outstanding achievement.

Evans-Pritchard’s first field expedition was to Dar Funj; he started from Khartoum about the end of October 1926, and established himself at Soda, in Ingessana country. The record he has given us of Ingessana society has not since been bettered. On 12 December, he left on a tour of the “Burun” country to the south, and arrived back in the Ingessana Hills on 7 January, 1927. During this period of scarcely a month, he made many detailed and accurate observations on the languages, history and custom of the southern Funj hills, providing a framework for future investigations. After passing south through Sillok and Ulu, he was prevented by illness from travelling more than a few miles beyond Wadega, into the Uduk speaking area; but he completed the circuit via Kurmuk and Keili.

Later in 1927, Evans-Pritchard arrived in Zandeland for the first time, and in connection with this trip spent five weeks on investigations among the peoples of Amadi District. On the basis of this first expedition to the Azande, he prepared a doctoral thesis for London University; and by late 1928 was on his way back to the Azande. In March 1929, he spent nine days in Bongo country, in Torn District, on his way home from the Zande trip. In his report on the Bongo (Sudan Notes & Records, 1929), he makes an appeal for others to follow up his research: “Owing to the shortness of my visit, my own notes are lamentably incomplete...” This appeal was to be echoed in many of his writings on lesser-known peoples, which, however, remain important and sometimes unique records.

For most of 1930, Evans-Pritchard was engaged on field research. He made his way, at the special request of the Government, to Nuerland, arriving there (unfortunately without most of his baggage) early in the year. In spite of misgivings, he spent some time in Leek and then in Lou country. He experienced so many difficulties, however, in particular political suspicion because of recent punitive patrols against the Nuer, that after three-and-a-half months he decided to return to the Azande.

This third and final visit to Zandc country brought the total period he had spent there to about twenty months. On his travels to and from Zandeland he continued to make brief investigations on a variety of non-Zande peoples: for example, he spent four days making enquiries among the Mberidi and

Mbegumba, on the old Yambio-Tonj road, in 1930, in connection with his Zande historical studies. He also prepared some notes on the Moru of Amadi District.

In the dry season of 1931, Evans-Pritchard returned to Nuerland. He went to the eastern Nuer area, spending the first fortnight at Nasser and then moving to the cattle camps on the Nyanding River. Physical conditions were harsh and movement almost impossible, so he went on to the Yakwac cattle camp on the Sobat and stayed there until the early rains. He had intended to go back to Leek country, but had a severe attack of malaria and was obliged to retire to Malakal hospital and England. This trip had lasted for five-and-a-half months; it was his longest in Nuerland. Just before taking up the Chair of Sociology at Cairo University in 1932 he read a paper to the British Association in which he remarked: “I do not regard my work among the Nuer as finished, and I hope to complete it when circumstances are more favourable.”

In 1935, after being appointed to a research lectureship in Oxford, he was awarded a Leverhulme Fellowship for two years, to study the Galla of Ethiopia. There was, however, a delay in making arrangements, and so he spent two-and-a-half months on the Sudan-Ethiopian border, making a survey of the Anuak. When at last he entered Ethiopia, the Italian invasion was imminent, and so he had to return to the Sudan, and he then spent seven weeks among the Nuer at Pibor. It was in the rains, and this trip again ended in sickness. But in 1936, after a period of fieldwork among the Nilotic Luo of Kenya, Evans-Pritchard returned for the fourth time to the Nuer, entering Adok in western Nuerland on October 1st. He had to retire once more after seven weeks, because of fever.

The bulk of Evans-Pritchard’s Sudan fieldwork was concluded by 1936; but in 1940 “I found myself back in Anuakland... and was able to make some further observations about their political system during a strenuous, if very minor campaign.”

The research tradition combining scholarship with an explorer’s determination which is peculiarly that of Professor Evans-Pritchard was established in a former era of the Sudan’s history. Since then, the country has welcomed many political changes; and it has continued to foster academic studies in social anthropology, in recent years through the University of Khartoum, the Anthropology Board of the Ministry of the Interior, and the Ministry of Education.

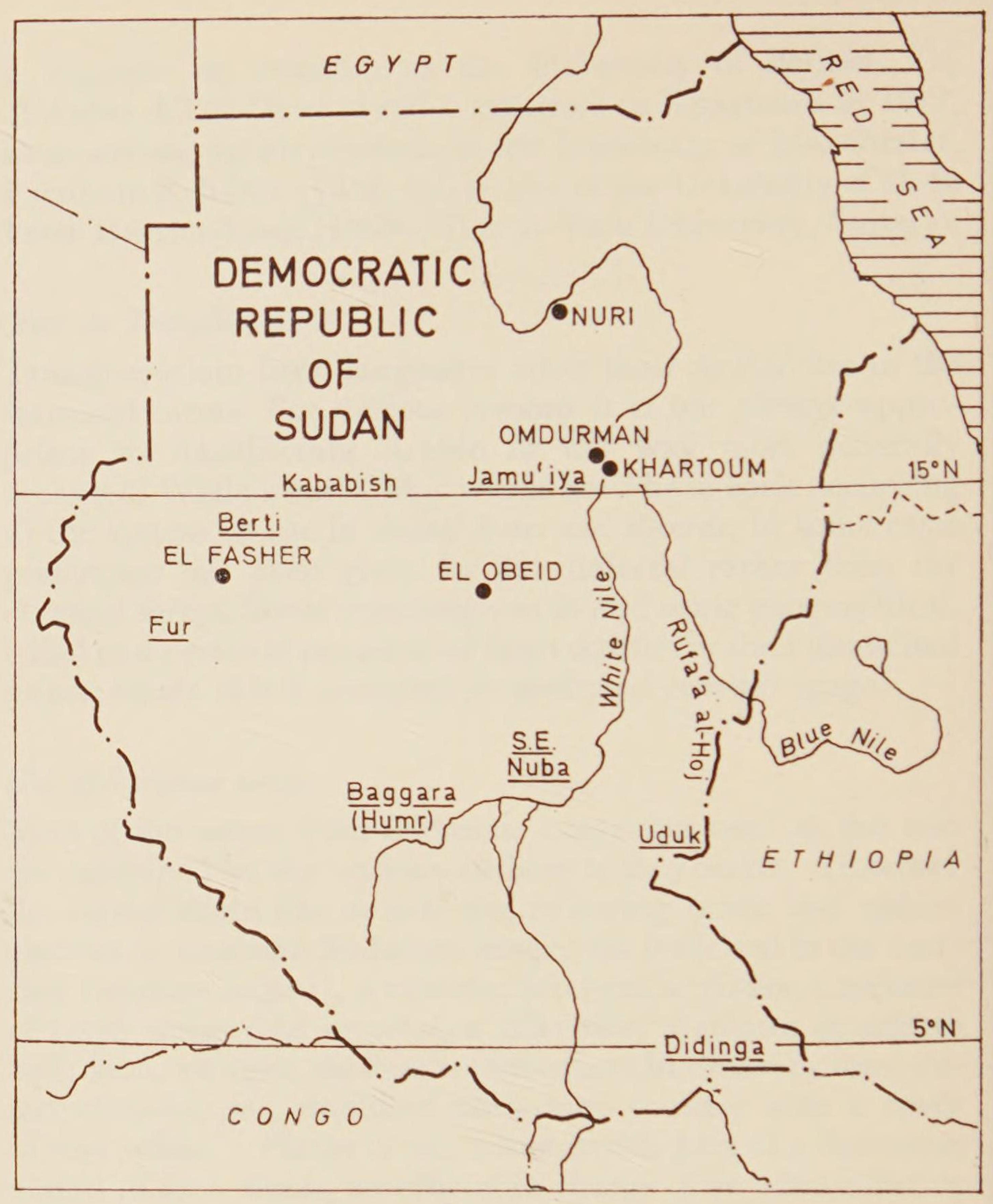

The essays in the present volume are offered as examples of contemporary work in the ethnography of the Sudan. They are the work of members, past members and informal associates of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology in the University of Khartoum. In their geographical spread (Nuri village to the Didinga, Darfur to the Ethiopian border), the varied character of the communities in which they are set (nomadic pastoralists, sedentary cultivating villages, Omdur-man and El Obeid) and the range of problems with which they deal (economic development, oral tradition, political and legal organisation, rite and symbol, the logic of kinship and the place of anthropology in the Third World) they indicate an important place for this subject, both in the intellectual life of the Sudan and those connected with it and in the practical social administration of the country.

We dedicate the essays in this collection to Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard, after his retirement from the Chair of Social Anthropology at the University of Oxford, as a token of our debt to his pioneering example, our affection, and our gratitude for the unceasing interest he has shown in the development of social studies in the Sudan. We remember with pleasure his recent visits in the capacity of external examiner to the Department of Anthropology and Sociology in the University of Khartoum.

February 1972

Ian Cunnison

Wendy James

Editors’ Notes

Acknowledgements

The Editors thank A. J. Arkell and Godfrey Lienhardt for helpful advice and encouragement at the time the book was being planned. The latter also read a draft of the Introduction, and Edwin and Shirley Ardener kindly commented on parts of the manuscript. The Editors also thank Derek Waite, of the drawing service at the Library of Hull University, for preparing most maps and diagrams, and Teresa Weatherston and Eileen Lee, of the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Hull, for secretarial services.

The Contributors

Andreas Kronenberg was from 1957 to 1964 an anthropologist attached to the Ministry of Education, Sudan, and is now on the staff of the Goethe University, Frankfurt-am-Main; he conducted fieldwork together with W. Kronenberg. Ladislav Holy, of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences at the time of his fieldwork, is now Director of the Livingstone Museum in Zambia. The other contributors are, or have been, staff members of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology in the University of Khartoum, at the dates indicated. James C. Faris (1966—9) is now in the Department of Anthropology of the University of Connecticut at Storrs. Wendy James (1964–9) was subsequently Leverhulme Research Fellow at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford, and has since been teaching at the Universities of Aarhus and Bergen. Ahmed Salman al-Shahi (1965—70) returned to Oxford to write up his research. Ian Gunnison (1959–65) is now at the University of Hull. Talal Asad (1961–6) of Hull University is at present in Egypt on a British Academy travel grant. Gunnar Haaland (1972-) paid two visits to the Sudan from the University of Bergen in connection with the F. A.O. Jebel Marra Project. Abdel Ghaffar Mohammed Ahmed (1970-) is engaged on research at the University of Bergen. Taj al-Anbia Ali al-Dawi (1966-) returned to Khartoum in 1971, after writing up his research at the University of Manchester. Farnham Rehfisch (1958–69) is now at the University of Hull. Peter Harries-Jones (1969–71) is at York University. Ontario.

Note, on Transliteration

Transliterations from languages other than Arabic arc in the standard forms. For various reasons it is not always appropriate to transliterate Arabic in the way most generally accepted. While most Arabic words have been spelt according to the system in use in Sudan Notes and Records, in some cases preference has been given to the dialectal rather than the classical forms. Some common words and some geographical, tribal and personal names have been written in their anglicised forms, where this is accepted or preferred current usage.

Use of Sudanese terms

Most of the terms from Sudanese languages used in the text are explained by the various authors as they occur. However the reader might like to note the following terms and abbreviations in common Sudanese usage, not italicised in the text: dura (sorghum vulgare), a common food grain \ feddan, a measure of 1.038 acres; jebel or jab al, a hill; khor, a stream or stream bed; wadi, an open shallow water-course in desert or semi-desert country; goz, stabilised sand-dune country with a cover of vegetation. Piastre or pt., a hundredth part of a Sudanese pound (LS). Omda, an official in charge of an adminisrative unit, the omodiya. In the system of local government prevailing until recently, several Omdas might be grouped under a Nazir.

I. Southeastern Nuba Age Organisation

James C. Faris

This paper is a description of the age organisation and its variations amongst the Southeastern Nuba. It will be argued that circumstances involving the history of the wider colonial society are sufficient and necessary to explain the variations documented in the Southeastern Nuba age system.

We are all now aware, I assume, that descriptions are (or in fact imply) theories, and that social anthropology’s theory and method are as much a part of its imperialistic heritage as the definition of its subject matter. This may sound pedantic and even rhetorical. But given the contemporary social anthropological proclivity for the speculative interpretation of symbol systems,[2] and the previous poverty of limited functional explanations (particularly of variation and change[3]), it is time to restate the case for historical materialism in explanation. It is perhaps appropriate here to do so as Professor Evans-Pritchard is one of the few British social anthropologists who have attempted to stress diachronic perspectives.

The Southeastern Nuba[4]

The peoples here designated Southeastern Nuba reside in three villages in the southeast corner of Kordofan Province, Democratic Republic of the Sudan. The villages—Kao, Nyaro, and Fungor—have a total population of under 2,500. This small group of sedentary farmers ( who keep some animals) live on and around the base of the last small group of low rocky mountains before the country slopes off to the sudd.

They are physically and socially rather isolated from other Nuba of central Kordofan, although they share certain cultural features with the Southern Nuba group (Mesakin, Talodi, Werni) and the North Central Nuba group (Heiban, Otoro, Tira)—the latter with whom they also share a language family (speaking a mutually unintelligible dialect).[5] Today closest neighbours are Baggara Arabs (Awlad Himeyd) to the north and west, and Shilluk to the south and east.

Their social organisation, characterised by duolineal descent and clanship, is quite likely an amalgam of the matrilineally-organised Southern Nuba and the patrilineally-organised North Central Nuba. This is borne out by traditions of migration, and by the sharing of certain matriclan section names with the Southern Nuba Werni peoples and certain patrician section names with the Tira and Otoro Central Nuba. The local duolineal system is a unique and peculiar adaptation, however, not found elsewhere in the Nuba Mountains.[6]

Oral tradition documents Nuba habitation prior to the movement of Baggara nomads into the area.[7] Surface habitation and stone tool evidence indicate the Southeastern Nuba have been in their present location for at least the past 200 years, and genealogies and linguistic separation from others of the same language family would indicate an even greater time depth. There are also traditions in linkage to the Funj kingdom (Tagali branch)—apparently a rather common claim of non-Arab groups on either side of the White Nile at this latitude.[8]

However reliable these oral data, it is certain the Southeastern Nuba have suffered locally at the hands of a series of raiders and slavers for a long time. Most relevant to this paper are the raids during the Mahdiya period.

While the Mahdi mobilised at Gedir in 1881,[9] he was met by the peace priest and assistants from the Southeastern Nuba. On the presentation of several pots of honey, local tobacco[10] and other gifts, a promise was extracted from the Mahdi not to attack the Southeastern Nuba.[11] Tradition holds that this promise was respected during the Mahdi’s lifetime, but ignored after his death by his Baggara successor, the Khalifa ‘Abdallahi.

It is said that three of the Khalifa’s lieutenants, known locally as Rashid, Majbur, and Al-Nur ‘Anja, raided[12] the Southeastern Nuba, and at least once were successful in overcoming Fungor, the least defensible and smallest of the three villages of the total society. Although some people escaped, the majority were captured, branded (and the men circumcised), and eventually taken to Omdurman to fight against Kitchener in 1898.[13]

The Southeastern Nuba were of sufficient numbers or renown that today one section of the modern city of Om-durman still bears their name.[14] After the fall of Omdurman in 1898 the remaining Southeastern Nuba returned to Kordofan. The circumstances and period of enslavement, however, resulted in several unique features of the Fungor social organisation and local community—not shared by Kao and Nyaro.[15] The major feature relevant to this paper is the variation manifested in the age organisation.

The formal age-group structure[16]

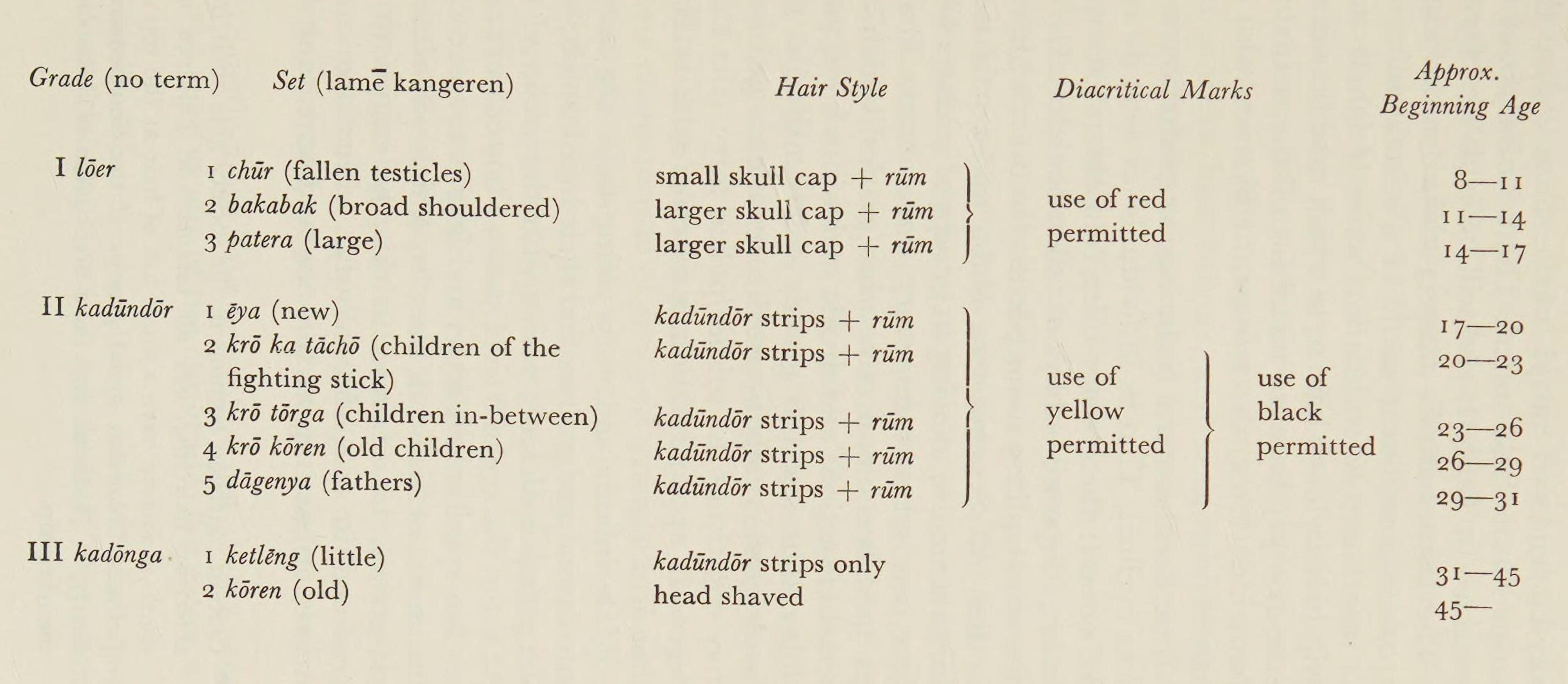

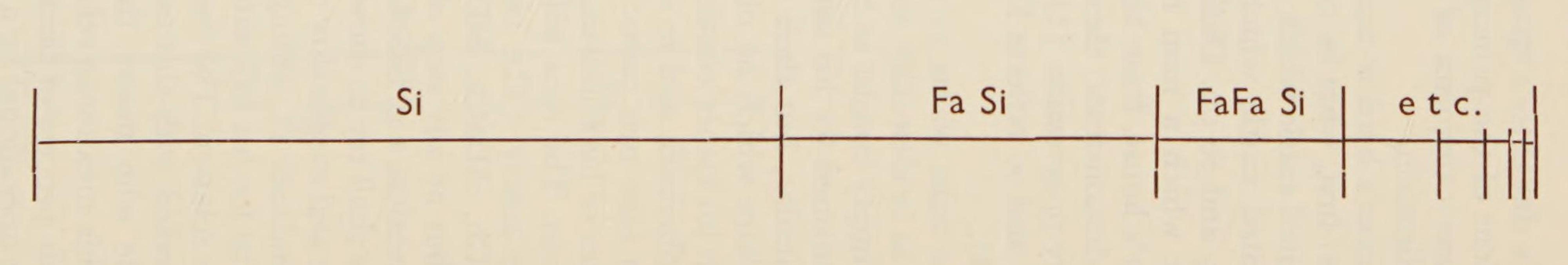

There is no term which can be translated ‘age organisation’, nor a term which may be translated ‘age grade’. There are three named units (here designated grades), the names of which may be translated, each composed of subdivisions (here designated sets) which are named and for which there is a term. The formal structure is illustrated in Table 1.

The grade names, Ider, kadundor, and kadonga, may be translated as ‘responsible boys’, ‘males of kadundor hair style’, and ‘elders’, respectively. The term for age set, lame kangeren, may be rendered ‘people of the same age’, as the term ngeren means simply ‘age mates’. The translations of the set names are given in Table 1, and will be explained further below.

| Grade (no term) | Set (lame kangeren) | Hair Style | Diacritical Marks | Approx. Beginning Age | |

| I loer |

1 chur (fallen testicles) 2 bakabak (broad shouldered) 3 patera (large) |

small skull cap + rim larger skull cap + rim larger skull cap + rim |

use of red permitted |

8—11 11 —14 14—17 |

|

| II kadunddr |

i eya (new) 2 kro ka tacho (children of the fighting stick) |

kadunddr strips + rum kadunddr strips + riim |

use of yellow permitted | use of black permitted |

17—20 20—23 23—26 26—29 29—31 |

|

3 kro torga (children in-between) 4 kro koren (old children) 5 dagenya (fathers) |

kadunddr strips + rum kadunddr strips + rum kadunddr strips + rum |

||||

| III kadonga | 1 ketldng (little)<b>2 koren (old) | kadunddr strips only head shaved |

31—45 45— |

The term kadundor may crudely denote ‘warrior’ in some circumstances, but it would be a mistake so to translate it. In its most narrow translation sense it labels the two-shaved strip hair style—a hair style which may be worn by men who have not yet become members of the actual soldier police (‘warrior’) force, the talmara, or by men who have recently retired from it.

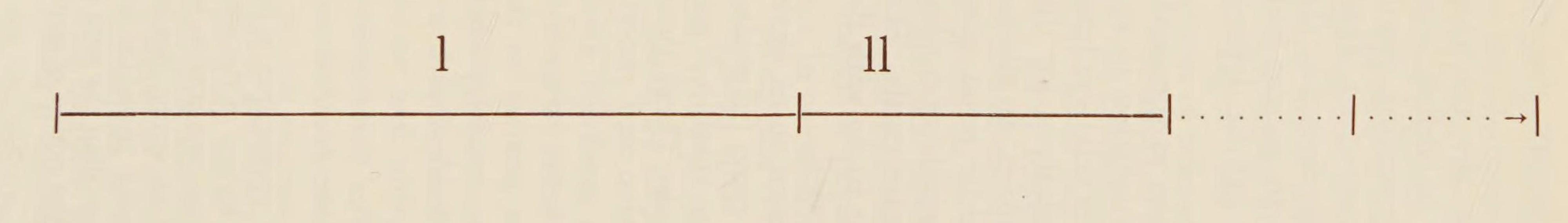

The Southeastern Nuba age organisation is linear rather than cyclical. That is, individuals (or sets) do not ‘revolve’ in the system: the kadonga koren, ‘old elders’, do not become Ider kachur, ‘responsible boys of fallen testicles’. Neither do initiation sets acquire a name peculiar to them which they maintain for life. All Southeastern Nuba males pass through a fixed linear structure, moving in groups of initiates which form sets, into new set statuses every three years. The age sets are grouped into broad categories (grades) which crudely denote certain functions and divide males into boys, young men, and elders. The kadundor grade, which might be glossed ‘young men’s grade’, only approximates the range of age sets which may constitute the soldier/police force (the talmara} and the degree of approximation is much greater in Kao and Nyaro than in Fungor.

Male infants and very young boys are not differentiated into formal age groups, and their hair fashion, later to become the group indicator, varies with the whim of their fathers.[17] At about the age of 8 to 11 years, a boy ceases to wear a random or clan-specific hair style, and begins to wear a tuft of hair on the crown of his head, the rum, which will remain until senior elderhood. In addition to this, he begins to have his hair groomed in one of two ways, either two narrow straight stripes originating at the rum and spreading forward at an ever-increasing angle to the front of the head (drothb), or a small skull-cap type of hair patch, with the rum tuft at roughly the centre (ludu). The size of this skull cap increases until initiation into the kadundor grade, some nine years later.

At the first indications of a boy’s approaching maturation, his hair style is changed and he is considered a member of the first set of the first grade. Entry is usually the decision of the village section elders, and involves no ceremony save the new hair style. At this time a boy may begin to decorate his body with red or shell-white base colours, and designs in black.[18] He is also now eligible to compete formally in wrestling tournaments.

The first Ider set usually wrestle only within the village section. They wrestle in other sections of the same village only after advancing to the second set of the first grade, Ider kabaka-bak, ‘broad-shouldered boys’. Boys advancing to the final set of the grade, Ider patera, ‘big boys’, wrestle in other villages— they meet opponents of their age set and others of loer grade whom they will be likely to meet in one or another of the sports of the society for the next ten years. The junior sets of loer grade may wrestle with foreigners who come into their village sections, but they cannot cross village section boundaries to do so.

In these inter-village wrestling matches (as in the more dangerous sports characteristic of the next grade), boys fight hereditary opponents—those with whom they have no traceable links—and the determination of potential opponents acts to inculcate a large measure of genealogical knowledge and awareness of intricate social networks.

Except for the increase in size of the ludu skull cap and the increasing formalisation of the wrestling activities, there are but few overt distinguishing activities of the various sets of the loer grade. For one example, only loer kabakabak of the village compete in the long distance race at the new year’s activities (alete).

But even if the distinctions have heretofore not always been clear between the various sets of the Ider grade, the patera set (final set) is carefully chosen, and all boys who have been age-set mates up to the time for advancement to the patera set may not necessarily be advanced to it together. Some boys, of course, mature more quickly than others, and elders of each village section decide which boys are of sufficient maturity to be advanced. This normally includes boys who arc from fourteen to seventeen years old; a physically precocious fourteen year old may be advanced to loer patera at the same time as a slower maturing seventcen-year old.

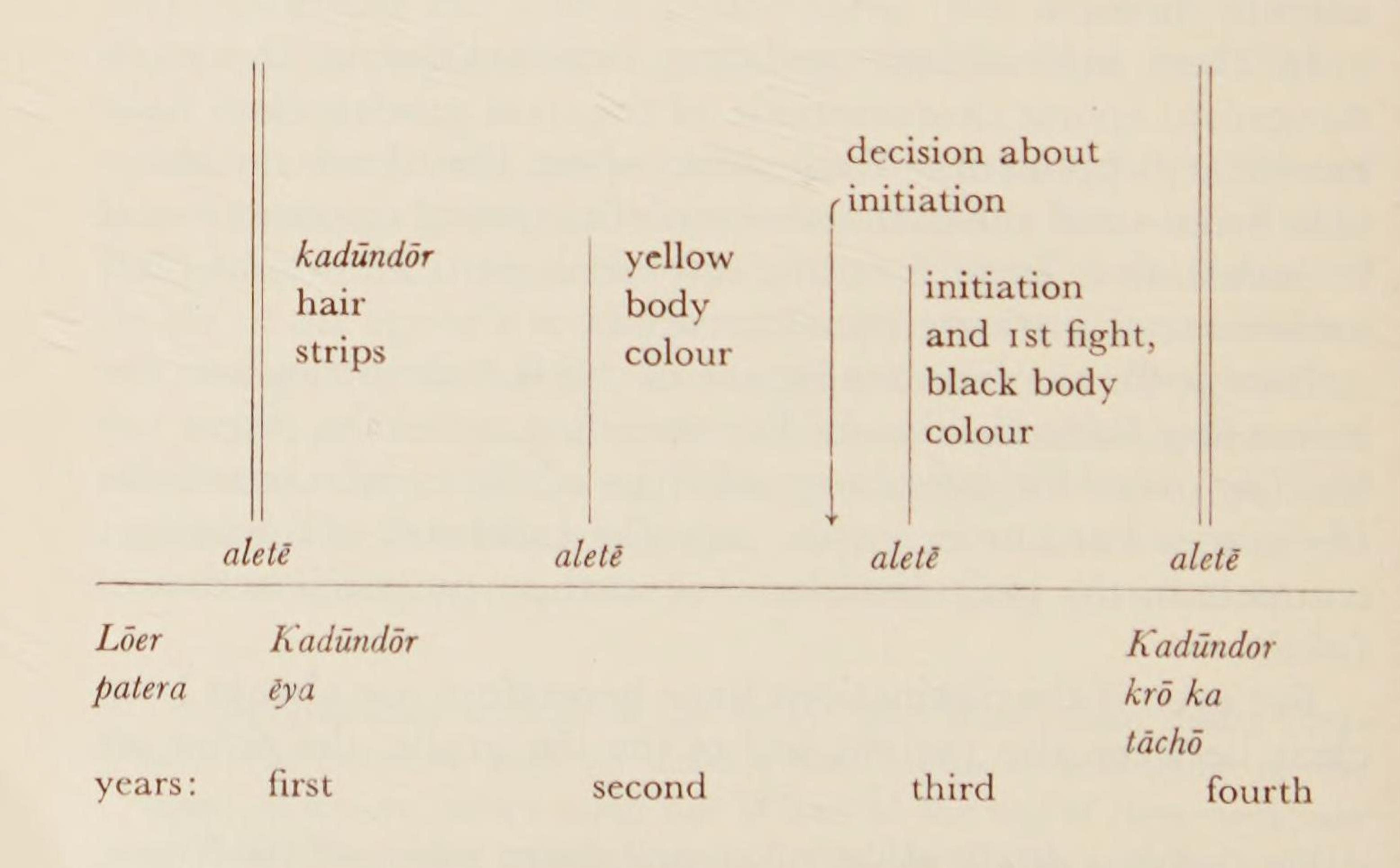

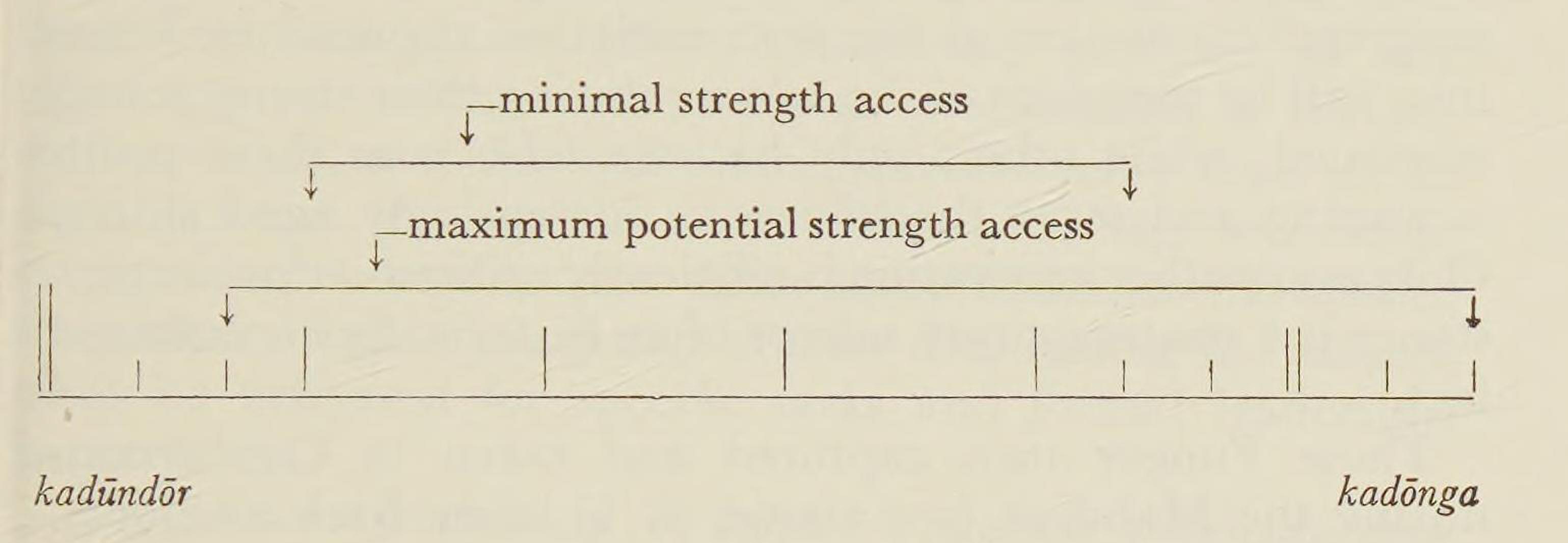

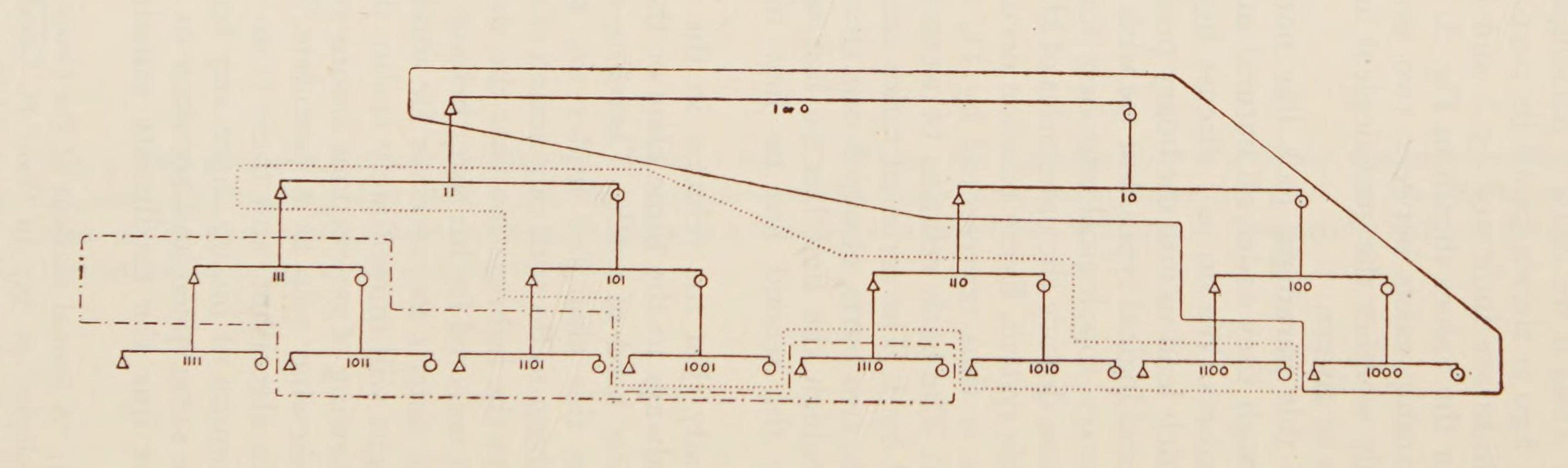

Advancement into the first set of the kadundor grade also depends on physical maturation, plus a host of other necessary factors, such as the maturity state of a young man’s betrothed and his health at the time. The young men chosen for advancement to kadundor eya begin first by adopting the kadundor hair style, and next by the use of yellow background in body design. Their formal initiation (which is really initiation into the sport of bracelet and stick fighting) comes two or more years later. After the initiation and the bracelet fighting debut, the kadundor eya are entitled to use rich black background in body painting, and are entitled to use a stick in the tribal sports, and become kro ka tacho, ‘children of the stick’ (see Chart 1).

Advancement through the last four sets of the kadundor grade involves no shift in diacritical markers—only attendance at a yearly age organisation ritual, ngorana, where every third year persons in the grade are advanced one set. It is at this ritual (see below, p. 20) that decisions are publicly announced regarding membership in the village soldier/police force, the talmara. Advancement by set each three years through the entire grade is automatic after entry into the eya set; no mitigating circumstances delay formal progression. When a man has been in the kadundor dagenya set for three years, a stick is broken which symbolises his set’s retirement from the sport and entry into the next and last grade, kadonga. A man at this time will be approximately thirty-one years old (see Table 1).

The kadonga grade is divided into two rough parts—the kadonga ketleng, ‘little elders’, and kadonga koren, ‘old elders’. No formal ceremony marks the shift from ‘little’ to ‘old’, but normally a man ceases to decorate his body and stops wearing the rum tuft of hair and kadundor strips, and begins to keep his head entirely shaved. Entry into the kadonga grade need not correspond to retirement from the talmara (soldier/police). As will be seen below, the age of recruitment to and retirement from the talmara varies markedly between the village of Fungoi’ and the villages of Kao and Nyaro, and even slightly within Kao and Nyaro over periods of time.

Elders no longer engage in sports, though their own fighting praises may still be sung by the drummers in the praise song cycles, and they may still prance and scream challenges at this time. It must not be assumed that a man’s life is labour after retirement from kadundor grade, however, for only after becoming kadbnga is one eligible for the very many ritual leadership posts.

Age and the organisation of production

The entry into Ider grade (marked only by a hair style and potential use of red body decoration) is normally coincident with goat-herding activities. Boys, singly or in small groups, are responsible for goats of the village section for at least the duration of their membership in the chur set. By the time boys enter the bakabak set they may have begun herding calves— which during the dry season requires that they accompany the older calves for distances up to two to three days from the villages in search of water and grass. If there are few boys in the set, they may have responsibility for the entire herd of a village section. Although it is herded together, each boy is normally responsible for the calves or herd of a father, a father’s brother, or a mother’s brother. Though every adult man does not have cattle, it is a rare youth who does not find himself caring for a few cattle for some senior patrikinsman—or more commonly, senior matrikinsman.

While a bakabak, a boy normally will become betrothed to a girl some six to eight years his junior. During his tenure as loer patera he will begin the required bride-service—which continues until the girl becomes pregnant, normally about six to eight years from initial betrothal.

The amount of work involved in bride-service to a girl’s father (or appointed surrogate) is substantial. A boy is required to provide yearly contributions of grain (in the amount of about two bushels, threshed); to build at least one normalsized living hut and one large cattle hut; erect fences around the fields adjacent to the village sections to keep cattle and other animals from the crop; and to contribute substantial weeding chores each season—amounting to at least two days’ labour by all members of his age set in the village section. Moreover, he is required to provide oil (an amount of approximately eight gallons each year) and coloured ochre for his betrothed (girls cover themselves completely with red or yellow ochre and oil from about five years of age until pregnancy), and various gifts, such as on occasions of scarring—which accompany all physiological changes in females. Demands are also made on a young man by his future mother-in-law for gifts of cloth, oil and money.

Depending on the maturity of a young man’s betrothed, he may begin a farm on his own while in the last year of Ider grade. If not, he will undoubtedly begin a crop of his own after advancement into the kadundor grade. The marriage is finalised normally on pregnancy, or, if this is not forthcoming, at an appropriate time after initial menstruation, usually about two years. Even the very rare girl who is without a betrothed will take on a skirt, cease to wear oil and ochre, and assume the appearance of other young married women

of the community about two to three years after initial menses.

It occasionally happens that a young man’s betrothed becomes pregnant while he is still loer patera. In this case, he is immediately advanced to kadundbr and enters the next bracelet fight—to wait for formal initiation when the next Ider patera set is advanced to kadundbr eya.

After advancement to kadundbr, young men always assume their own fields. On finalisation of the marriage, a young couple normally moves into one of the husband’s father’s huts or, if none is available, into a vacant hut of another resident senior patrikinsman. Only in rare circumstances will a man and his new wife move into one of his matrikinsmen’s huts, and almost never into a hut of the girl’s kinsmen. With the common occurrence of cross-cousin marriage, of course a young man and his wife share many kinsmen. The physical consummation of the marriage, part of the pregnancy, and the delivery of the first child (only), takes place, however, in the wife’s natal home.

Wives to a new kadundbr (the society is characterised by common polygyny) are a vital production asset. Apart from domestic support, wives carry grain from the fields to the threshing arenas, and make the beer necessary for weeding, harvesting, and threshing parties.

With the agricultural techniques available and rigorous environmental conditions, there are limits on the size of fields a man can handle. Weeding, harvesting and threshing are collective activities, but beyond a certain amount it is impossible to capitalise on existing agricultural produce. Grain can seldom be stored more than one year without ruin from vermin and elements, and there are no reasonably accessible markets for surplus grain sale. Occasionally grain is sold to nomadic Arabs or Fellata (Sokoto Fulani) going through the area, but this is not a substantial exchange.

Some young men without wives (usually whose wives have been stolen) have begun to cultivate cotton in the past few vears. This is sold to Arab merchants in the nearest market town, but it is important to note that most of their proceeds must go for grain purchase. With a new wife and young children this becomes a dangerous and uneconomic investment. Older men with mature sons of Iber grade may attempt both cotton and grain production, but the exigencies of production in current technological and ecological circumstances make this diversification possible only with a more sizeable labour force. A man’s productive life after retirement from the kadundor grade is precisely related to the labour force in sons and attached kinsmen he may command. The very aged usually attach themselves to a son and contribute what labour they can. Aged men without offspring are the responsibility of more distant kinsmen, usually matrikinsmen.

Very little of a grown man’s time is spent on herding or cattle care activities. But generally elders spend an increasing amount of time in hunting pursuits. Game is still reasonably plentiful, and at least every other hunt yields some meat. Hunts are seldom more than one or two hours from the village, except where a specific group of men (based on friendship and residential networks) go after giraffe or other large species found at greater distances from the villages. Fishing is sometimes pursued in lakes during the spring—a productive activity which is most commonly carried out by young kadonga and older kadundor. This is never for more than about two weeks in any year, however.

Even though ‘elderhood’ begins at approximately thirty-one years, it would be wrong to assume tensions and strain from a premature retirement and antagonisms based on early transition to elderhood, as does Nadel.[19] On becoming kadonga the demanding and onerous talmara duties are nearing an end (particularly in Kao and Nyaro, see below, p. 26), and a rich and full ritual life begins. Moreover, prestige accrues from agricultural and hunting success and the fathering of many children.

The time invested in ritual activities should not be underestimated—and to a large extent this is specific to elder males. On the assumption of adult personality (after the bracelet fight initiation), young men participate in the affairs of the ritual societies to which they may belong by ascription; the kin-group rituals (patrigroup and matrigroup); kin groups linked to one’s own (sec below, page 21, note 24, for reciprocal clan relations), and matrikin groups of one’s father. Investment at this point is limited to group participation, but on reaching elderhood, a man assumes various leadership posidons in the ritual activities, which involve considerably more time.

For four or five sets of kadunddr f kaddnga (six sets in Fungor) men, the talmara soldier/police force requires time, in weeding assignments for important priests as well as other society functions (see below, p. 21). In former times the talmara constituted the raiding organisation and first defence force. The time and work is so demanding that men always press for early retirement and release from talmara activities.

Age-group recruitment and group function

The formal recruitment mechanisms for age-group structure have been outlined above. For the tribal sport of bracelet and stick fighting (timbraf and for the village-specific talmara force, the age-organisation recruitment mechanisms are specifically mechanisms for personnel selection to the activity. In other age-based activities, age-group memberships are prerequisites or correlates of activities, but the recruitment mechanisms themselves are not necessary to these functions and activities.

(1) The timbra

By far the most important sporting activity of the Southeastern Nuba is the bracelet and stick fighting which generally characterises the kadunddr age grade. Boys train for this activity during their wrestling years and the results of the sport form the basis for dance praise (or ridicule) songs composed by the drummers’ society—a vitally important public acknowledgement of one’s performance. These praises are remembered, recounted many times publicly, and transmitted through members of the drummers’ society (chabajaf)[20] to be sung on occasion during a man’s waning years and finally to form the central dance praise song at his funeral. The importance of this sporting activity and its consequences for adult males can hardly be overemphasised.

(a) Initiation

Decisions about changes in status of young men in the age system are made at the ngbrana ceremonies in October or November (see below, p. 20), and become effective or are implemented at the following New Year’s rituals (alete) normally held in January. In the case of kadundor eya, a decision is reached about their initiation at the fall ngorana, and is normally effected at the following alete (see Chart 1).

The ‘initiation’ or period of isolation prior to the first fight is normally from ten days to two weeks. Young men are initiated in village-section groups[21] and spend most of the period of seclusion in caves on the mountainside immediately adjacent to their village sections—only coming down in the evening to sleep in a special cattle hut prepared for the occasion. They are covered each day with sacred mud (ku) and ash, both to give them strength for the coming initial fight, and to protect them from the potentially dangerous stares of others. This is washed off each night when the young men descend from the mountain to sleep, and is the same mud that will be smeared on them prior to all other timbra. fights in which they will participate for the next ten years. On coming down each evening, the initiates also put on sandals as protection from dangerous substances or signs on tlie ground which might have been set by witches or enemies. For the same reasons— fear of pollution and loss of strength—the initiates do not cross village-section boundaries during the isolation period.

The isolated fighters are served by a chosen Ider patera boy who will belong to the next set to be initiated. He keeps their sleeping hut clean, brings them water and food, and keeps the initiates company—particularly important if only a few arc involved. Food is particularly rich and heavy, involving much oil and honey. Milk and meat are made available in large quantities, and the normal grain-porridge staple is mixed with water and strained, and the liquor drunk. Food is provided for each initiate by female matrikin and wives of patrikinsmen. In real ways, the isolation is a fattening period.

The isolated initiates are visited by village-section elders who advise them of appropriate behaviour during the initial fight and when later visiting other villages. Much of this is, of course, common knowledge. The elders also offer considerable moral instruction, and constant admonition to fight well, to not dissipate strength on lovers, and to be as brave as the elders were in their day. The end of the isolation is marked by an extended and elaborated version of the common prefight ritual used by all combatants of the kadundor grade.

Each village section has a special priest for rituals involving the timbrd fight. This post is hereditary in specific resident patrician sections, and the incumbents are responsible for all pre-fight ritual of new initiates as well as older fighters. This specialist mixes the village section’s ku mud and prepares the herbal mixtures applied to the bracelets prior to fights. He arranges the invocations preceding each contest, supervises the tying-on of the bracelets (which are kept in a special storage place near his compound). He also makes decisions about allowing a young man who may be weak or ritually polluted, such as from the death of a close kinsman or from recent sexual intercourse, to prepare ritually, put on a bracelet, and attend the contest. These initiates approach their fight much less conspicuously than older fighters, for they do not yet wear rich shiny black which protects against the stares of others, and which can be worn only after the first daytime performance of their first fight’s praise song and dance (usually taking place within the month following the initial fight). The initial fight is a combat with the heavy brass bracelets only, the stick fight portion of the contest not coming until entry into the second set of the kadundor grade, krb ka tacho (‘children of the stick’). All the village section rejoices if a youth does well in his initial fight, and then begins to collect the necessary material and money required by the drummers’ society to pay for the composition of the praisesong cycle of his initial fight. This is extremely expensive (amounting to LS 7) but critical, for without it, the prancing and shouting which take place at the dance are impossible, and the payment is further supported as the drummers’ society will not perform at a man’s funeral until this initial payment is completed.[22]

After this praise song is composed and performed the first time, the young fighters may weai’ the rich black background colour in body designing, and may shortly begin the stickfighting portion of the timbrd combat. The initiatory aspects of the kadundor grade are then finished. At this point a young man is considered to have a wholly adult personality.

The entire initiation is one of classic form: ritual removal; a period outside society characterised by extraordinary behaviour and diet; a ritual re-introduction with new knowledge and superior strength; and a changed status realised by entry to the tribal bracelet fight and the diacritical shifts after the first fight’s praise songs.

(b) Combatants

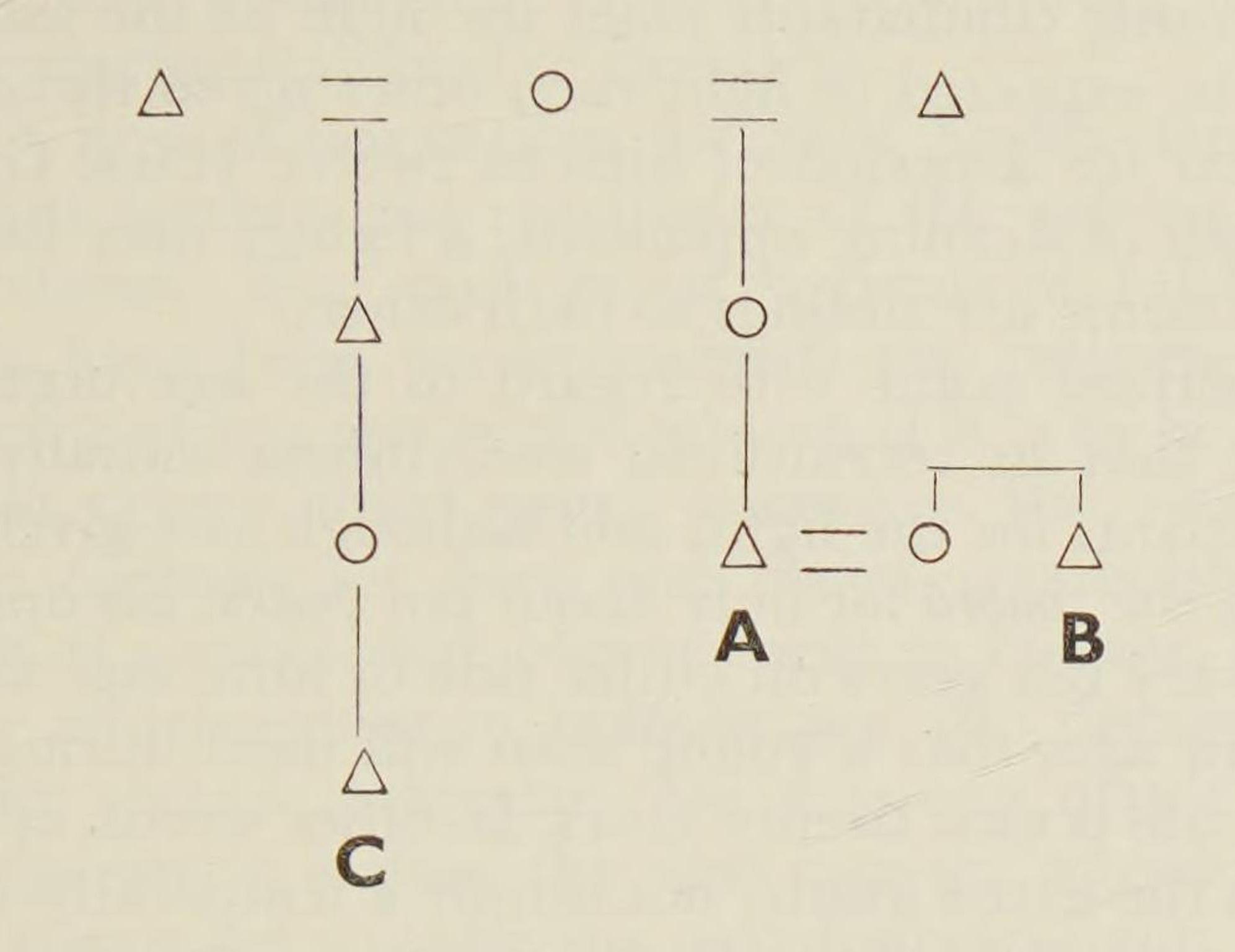

Opponents in the timbrd fight are determined by an examination of the kinship and affinal bonds between potential combatants, or between an elder spectator and two potential combatants. Should any male older than the fighters object, and should such objection be supported genealogically, the fight cannot take place. Combat is between those with no traceable links to one another or to a third party objector. The degree to which kin and affinal relationships are considered is sometimes striking. Fights between matrikinsmen and between patrikinsmen are prohibited—sanctioned respectively by witchcraft fears and the threat of expulsion.[23] Another categorical prohibition includes the same-generation members of the father’s matriclan (i.e., classificatory FaSiSo), the same-generation offspring of males of own matriclan (i.e., classificatory MoBrSo), and the same-generation offspring of males of father’s matriclan (i.e., same-generation offspring of males of the same matriclan). This category is coded by a term, da^da^a, and fighting between da^da^a automatically brings about leprosy. But quite apart from these mechanical prohibitions, a not atypical example is illustrated in Figure 1.

A refused to allow B (his wife’s brother) to fight C (A’s mother’s uterine half-brother’s daughter’s son).

The complicated kinship and affinal networks narrow the range of potential opponents. This has become so serious in the society that most combatants are now from different villages—the intra-village possibilities now being negligible. In some cases a fighter may have only one or two potential combatants for the entire range of his fighting years. Others, however, especially of small matriclans and small patricians, may have many possibilities and frequent opportunities for , combat.

Should there be no traceable (or objectionable) kinship or affinal links between the potential combatants or between them and an objecting third party, the fight may take place. Referees watch carefully to attempt to ensure that no undue advantage accrues to either of the fighters, as, for example, in the case that one stumbles, breaks his fighting stick, or loosens the bindings holding his brass fighting bracelet.

But age, relative size, and skills learned from several years in the grade are normally irrelevant to determining combatants, and a small, young and inexperienced fighter in his last eya set year may find himself matched against a large, experienced fighter in his last dagenya set year. The only consolation to the young fighter in such a case, as the outcome of the individual fight is obvious, is that he must only meet this opponent for one year, since the older fighter is soon to retire from the grade.

If two young combatants enter the fight at the same time, they may be expected to fight each other up to three or four times a year for a period of nine to twelve years. Given the kinship basis of defining opponents, a fighter may find many of his opponents are siblings to each other.

An important point with regard to the age organisation is the fact that its recruitment mechanisms initially dictate the participants for the fight, and although any given fighter is active in the timbrd for only about ten years, his opponents’ ages will vary ten years on either side of him, and the range of opponent ages that a young man will meet during his ten years in grade is thus twenty years. In other words, opponents come from the entire grade, not simply a temporally-identical set, and he may fight old kadunddr when he is young and young kadunddr when he is old.

(ii) Ngdrana ceremony

After the ripening of the first grain (about October), the ngdrana[24] ritual is held. Most males of kadunddr and kaddnga grade attend, the specific date being set by the hereditary priest-in-charge. This leader is the rain priest (or a surrogate from the rain priest’s clan section) in each village. The relationship between rain and the age organisation is manifest only in the talmara (soldicr/police force) relationship to the rain priest. They weed his fields, may build his huts, and should his ritual control bring insufficient or too much rain, the talmara arc responsible to the entire society for forcing a correction. The annual ‘tax’ due the rain priest (paid in grain contributions) may be collected by the talmara should it not be forthcoming voluntarily, and should action be necessary because of inadequate rain control, the talmara beat him or tie him to an ant-hill (or both), which may result in death. This ‘punishment’ is regarded as putting into motion a purely mechanical kind of causality.

After a host of invocations for good health, long life and production success, the remainder of the ngorana ceremony is age-related. The rain priest announces (although the decisions have been predetermined) the retirement and/or recruitment of age sets to the talmara, if it is to be done, and may also (every third year) announce the retirement of a senior kadundor set from the timbra (symbolised by the breaking of a stick) and advancement to kadonga. Individual cases for advancement to kadundor are also discussed at this time, and should it appear that a young man’s wife may become pregnant before the next age-set advancement, he may be instructed to enter the next bracelet fight.

Should any change in talmara leadership be necessary (for reasons of retirement, incapacity or incompetence), it takes place at the ngorana, the rain priest announcing the new incumbent after consultation with elders. And talmara strength and performance (see below, p. 23) is discussed, including such issues as undue harassment of a priest or ritual specialist; or conversely, insufficient warning or punishment of recalcitrant specialists. The rain priest may bring complaints against the talmara for insufficient aid in weeding, house building, collection of grain due, or non-cooperation in general. Talmara members younger than the elders bringing the complaints must not dispute the charges (see below, p. 28 for relative age behaviour).

The talmara then leave the ngorana site, go to the village near farms, and each take four heads[25] of ripe unharvested grain. They are accompanied by the rain priest’s assistants who collect grain as ‘tax’ for rain services rendered. Some of the talmara grain is boiled, roasted and eaten, and the remainder is made into beer by the wives of talmara leaders to be consumed by the talmara later. After feasting on the boiled and roasted grain, the talmara return to the Helds near the village sections to confiscate loose animals (pigs, goats or cattle) which might get into fields to eat the newly-ripened grain.

Should loose animals be confiscated, those responsible for keeping the animals penned may be beaten (i.e., younger Ider boys and young girls). The animals are divided equally between all talmara members, except that the head, spleen, liver, chest and kidneys go to the peace priest, who may also command a fine from the animal’s owner for having let it become loose.

No one attempts to block talmara action during these activities, for fear of being beaten or tied to an ant-hill. At no other time of year, however, do talmara have authority to confiscate animals, unless so ordered by the peace priest for payment of fines, or for provision for special external guests (such as the rare occasion when a district Local Government Inspector visits the community).

(iii) The talmara

The age organisation also provides the basis for recruitment to the talmara (soldier/police force), but the way in which this is effected is quite different in the village of Fungor from that of Kao and Nyaro. The latter two villages share the same recruitment/replacement system.

(fl) Kao/Nyaro recruitment

At every third ngorana the formal advancement of persons to higher sets takes place. Except for the initial kadundor sets and the final kadundor dagenya there is no ritual, and advance is without ceremony or diacritical marker. More important,

is food’, an unrelated non-reciprocal clan sections are llga-—those ‘between whom there is fire’. See Faris, “Some aspects of clanship...” for details.

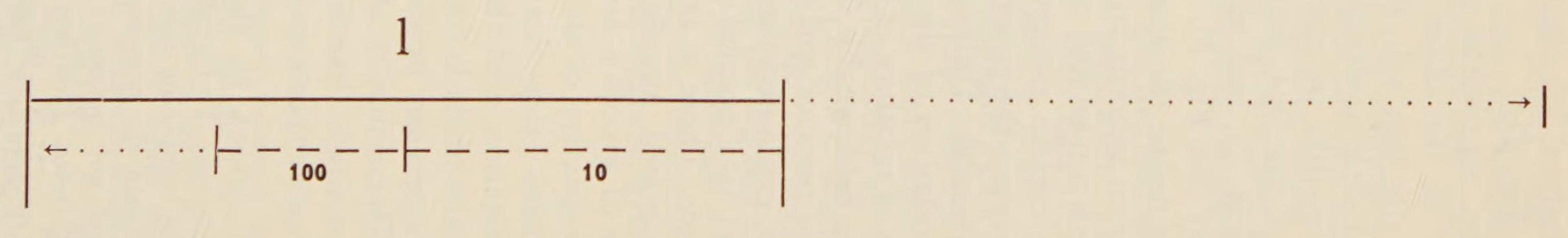

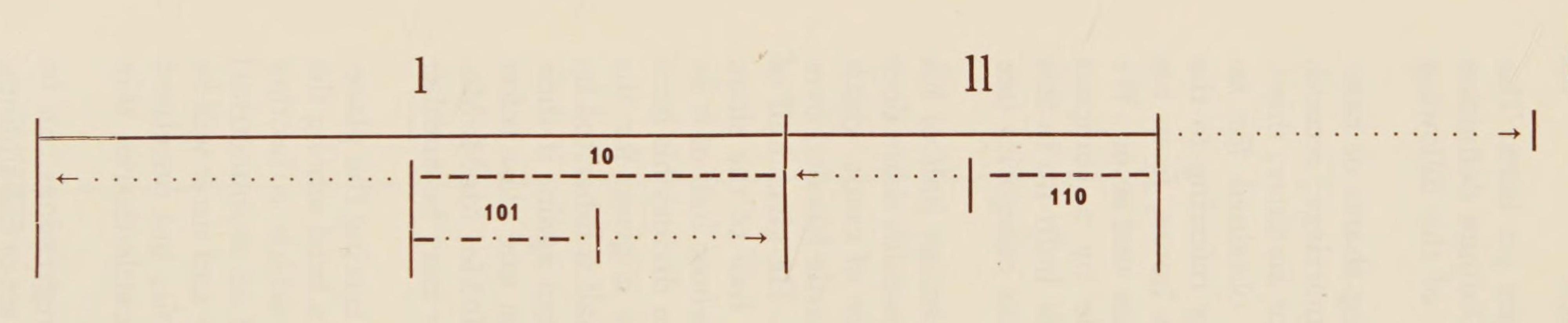

however, is consideration of talmara strength, and this may take place at each year’s ngorana. If the strength of the talmara is down from natural causes, or if a potential incoming set is small, decisions will be made to delay retirement of the eldest set of the group, even if this set is retired from Umbra combat and the kadundor grade. If strength is sufficient, one set may be retired without admission of a new set; if strength is insufficient, a new set may be admitted without retirement of the eldest set. This may be diagrammed, as in Chart 2.

If sets are large, then talmara strength is kept up with fewer of them, but if they are small, it may be that four or more sets are required. This variability is clear evidence that the kadundor age grade and the talmara soldier force are not exactly the same and should not be confused. Indeed, a concrete example of the necessity of this flexibility in talmara recruitment may be seen in the case of Fungor.

(b) Fungor recruitment

The age-grade and age-set system of Fungor is identical to that of Kao and Nyaro. But the use of the set system for recruitment to talmara is strikingly different. The Fungor talmara may at one time be roughly the kadunddr age grade, such as it is in Kao and in Nyaro. But at another time it will contain only members of the oldest set of kadundor, while the great majority of members will be kadonga. Recruitment in Fungor, instead of every third year, is but once every eighteen years.

The Fungor talmara is normally composed of up to six sets, in contrast to the four-plus sets of Kao and Nyaro. At the time of recruitment, the youngest members will be kadundor eya, and the oldest members the youngest kadonga set—a range from about eighteen to thirty-six years of age. Just before the time of the next recruitment to the talmara, eighteen years later, the youngest member will be a young kadonga ketleng’, the oldest members will be kadonga koren, about fifty-two to fifty-five years old. In terms of able bodies, then, the Fungor talmara are strongest just after an initiation, and become progressively weaker as the next initiation approaches. Some men will be members of the talmara during their strong young manhood, while others only become talmara as their youth is waning and serve the talmara as increasingly aged ciders. Only every other generation is efficiently utilised—this circumstance is a contemporary mirror of an historically necessitated fact.

Those Fungor men captured and taken to Omdurman during the Mahdiya (see above, p. 4) came back as elders. In reconstituting a talmara force they had only themselves and the offspring they might create in future. Thus they continued to serve as the Fungor talmara until the new offspring matured to kadundor and were initiated.

A ‘generation’ of potential talmara was wiped out in the raids on Fungor, and the recruitment system today maintains this generation gap. Rather than the slow trickle in and out of the talmara every third year which characterises the Kao and the Nyaro talmara, the Fungor talmara jumps with a complete change of personnel every eighteen years each incumbent then serving the entire eighteen years of the duration between initiations. Without a change in recruitment, there is no way of adding to the numerical strength of the force, whereas in Kao and Nyaro, sets may be added or dropped as size and strength demand.

A proto-Fungor talmara may have looked like that found in Kao and Nyaro today. Certainly the flexibility of the Kao and Nyaro system is suggestive—for should strength be low, retirement may be delayed. This is exactly what happened in Fungor, but the delay had to be until an entirely new generation of males could be bred and matured to kadundor—an 18-year delay. This delayed retirement then became an instituted feature of the Fungor talmara selection, and the Fungor talmara today contains the requisite six sets (eighteen years), the time necessary for maturity to kadundor of a newborn. The flexibility provision characterising the entire Southeastern Nuba talmara selection, was then evoked in the extreme to permit reconstruction of the Fungor talmara.

(c) Talmara leadership

The elder leadership positions for the ngorana age ritual have been described above. Formal leadership positions in any given age set are not necessary, as mobilisation is villagesection based, and this will seldom involve more than six to eight persons. Age grades and village-wide age sets never emerge as corporate groups. After acceptance into the talmara the entire village-wide group of men constituting the talmara must be activated for specific tasks and formal leadership is necessary.

The talmara leadership is fixed in specific patrician sections—that is, the post is hereditary in the clan section, the specific incumbent being chosen by the ngorana leaders. But this is slightly different for each village of the society. In the village of Kao there is one leader with two assistants, both of whom come from patrician sections of a different village section than the leader. These men are hereditary assistants and never leaders. This means, in Kao, with three village sections, one village section provides neither leader nor assistants. During the tenure of my research this was a sore point, and there was discussion by the “disadvantaged” village section talmara of forming a separate talmara society.

In the village of Nyaro, the same imbalance is not found, as there are two talmara co-leaders, each post hereditary in patrician sections of each of the two village sections of the village.

In Fungor, the number of talmara leaders exceeds the number of village sections, and each section is represented by at least one leader (succession again in the patriline). There are six co-leaders in total. In Fungor, however, one ‘leader’ (of appropriate patrician section) must be an infant. This baby attends all talmara functions—being carried or placed on a donkey until old enough to walk. This youth serves as a marker, whose maturity and advance to kadundor is an indicator of the appropriate time for another talmara force to succeed. Shortly after this youth is initiated to the timbra, the existing talmara force is retired and another talmara comes into being, with this young man as one of its adult leaders. Another infant male of his patrician section also becomes a leader at this time, and the eighteen-year talmara tenure period begins.

In all villages, the talmara leader (s) and assistants make decisions about talmara actions, mobilise the membership for these actions and direct sanctions against members who have not participated in the talmara chores. This is not an easy or popular task. No glory or praise songs accrue to talmara activities, and they are generally regarded as onerous. The talmara must weed the fields of the rain priests and the peace priest, and must frequently run errands for the latter. Today this involves various courier assignments, including messages to the nearest police post, about forty miles away, the summoning of persons to the public moot of the peace priest, and the enforcement of decisions of the moot. Thev must also meet nomadic Arabs to turn them and their herds away from Nuba water sources in very dry years—not a popular assignment and a constant source of friction between the sedentary Southeastern Nuba and the nomadic Baggara Arabs. And they must decide upon and execute various punishments to recalcitrant priests and ritual specialists should failure occur in the sphere of activity over which these specialists and priests bear responsibility.

None of this activity is rewarded, and it takes determined and strong leaders to decide upon action and mobilise the force for these assignments. Talmara who do not participate may have their granaries invaded by the membership, the grain so acquired being distributed to members after it has been made into beer by the wives of the talmara leaders. This ‘fine’ levied on recalcitrant members who do not have acceptable excuses for their lack of participation is heavy, being many times the worth of the labour required in the talmara activities.

The talmara must never take prepared food, however, in any of their requisitioning actions, and there are important sanctions (accompanied by a series of symbolic equations) which specify persons who may command cooked or prepared food.[26]

Relations between sets, internal set solidarity, relative age behaviour

Specific relationships exist between adjacent and alternate sets. It has been pointed out above that those running errands and keeping the isolated timbrd initiates company are members of the adjacent younger set, i.e., Ider patera. This aid is symbolic of the close relationships which exist between adjacent sets who will remain sources of support to each other throughout life. To a lesser extent, close relationships exist between alternate sets—a member of an older alternate set is, for example, considered best to help bind on one’s timbrd bracelet, for then it is less likely to come loose. And older sets, adjacent and alternate, have authority, can scold, give unwanted advice, and criticise. Younger sets must accept this, however onerous it may become.[27]

Internal set solidarity is based first on the common experience of age, reinforced by many factors. By the time boys are herding cattle, their constant companions will be age-set mates from the same village section. Patrician sections are localised and boys are cautioned not to cross village section boundaries until they are kadunddr—save on the sanctioned occasions such as a bakabak or patera wrestling match. Thus age and sex are visible in most group activity of young people until after their timbrd initiation when they begin to participate in matriclan rituals (matriclans are dispersed) and in other non-kin organisations and societies[28] in which both adult men and women are involved.

There is age-set cooperation in herding, as mentioned. But when a young man begins bride-service—which involves considerable work time in weeding and hut building— villagesection age-set help is essential. Cooperative age-set work teams take care of each other’s bride-service obligations in turn. A man’s reputation vis-a-vis his affines rests to a large extent on his abilities to mobilise his village-section age-set mates when required. Indications of unsuccessful bride-service can result in rejection of a young man as a suitable mate. As relative age demands respect, there is little redress a young man has should a future father-in-law reject him.

Age-set solidarity for adults is, of course, basically manifest in the fact that the men of a group are recruited and retired together—they enter and leave the talmara together, for example. And finally, on a death, the drummers sing the praise songs of the deceased and his age-set mates, and such age-set mates are obliged to prance, utter challenges, and otherwise express their mourning loudly and publicly.

The very great degree of respect tended elders by younger men can be seen first in the fact that any older person can object to a fight (timbra} and the younger combatants must accede to his objection, however poor his reason may appear—i. e., however remote the links may be that he traces between himself and the two combatants or simply those that he perceives between the two fighters.

The respect involved in relative age distinctions can also be seen in any formal interaction setting, such as a ritual or a public moot. Here, any younger speaker should not directly address an elder—he should address indirectly the person the statement is intended for, by making his comments to another attending elder, preferably a kinsman. In fact, this caused me initial grief, as my familiarity with the language did not allow me to see at first that most statements in moots and rituals were actually directed to persons other than those to whom they were in fact addressed. In all decision-making situations, relative age distinctions always dictate authority where it is not otherwise specified.

Youths must not eat from the same container as their elders (members of other grades), nor sit on the same sleeping racks.[29] In greetings, a younger person always initiates the action and extends his arm so the elder may touch the top of the wrist or the extended hand. Only age mates shake hands, and a younger’s hand must be placed beneath an cider’s in the hand-touching greeting. This is perhaps one of the most concrete manifestations of the superordinate-subordinate character of relative age behaviour.

Conclusions

The age organisation of the Southeastern Nuba has been described in brief. It differs from the better-documented age organisations of East Africa[30] basically in that Southeastern Nuba personnel move through a fixed linear structure, as opposed to a peer group (set) ‘revolving’ in a cyclical structure (cf. Karimojong, Jie, Turkana, Kikuyu). Although the Fungor talmara structural variation initially looks similar to the ‘generation set’ described for the Karimojong[31] and others of East Africa, it should be clear the similarity is spurious. Without knowledge of the history of the wider social structure of the Sudan, however, it might seem less so.

Enough detail has been presented to demonstrate that there are insufficient differences between the Kao-Nyaro and Fungor systems to derive a functional explanation of the differences in the talmara organisation. The absolute equivalence in formal age organisation and functional equivalence in talmara activities demands that explanation for the talmara recruitment and retirement differences be sought elsewhere. This illustrates in these circumstances the poverty of explanation of a synchronic comparative approach.

Even in this limited aspect of the age organisation of an isolated tribal society it can be seen that colonial history is a necessary and sufficient factor in explanation. How much more critical should be historical materialism, then, for causal questions in wider African settings. We must, as Thompson says,

... look at history as history—men placed in actual contexts which they have not chosen, and confronted by indivertible forces, with an overwhelming immediacy of relations and duties and with only a scanty opportunity for inserting their own agency...[32]

POSTSCRIPT

Since this paper was written I have received information from Prof. P. M. Holt on a recent summary translation of the unpublished Kitab sa‘ adat al-mustahdi bi sirat al-Imam al-Mahdi (Isma‘il b. ‘Abd al-Qadir) prepared by Dr. Haim Shaked as a thesis in the University of London, 1969. This hagiographical account contains references to Rashid Ayman’s advance on Gedir in 1881:

On reaching Jabal Funqur, Rashid warned the inhabitants not to inform the Mahdi of his march, hoping, thereby, to take the Mahdi by surprise (Shaked, p. 128).

It continues:

When the Mahdi heard that the people of Jabal Funqur, which is two days from Qadir, had aided Rashid with transport animals, provisions, and some fighting men, he set out with all his companions, to raid them. After the Mahdi’s arrival at Jabal Funqur, its people wanted to fight him, but God cast fear in their hearts and they requested the Mahdi’s aman, which he granted them. In accordance with his noble practice he pardoned them and returned without a battle (Shaked, p. 131).

I have noted the oral tradition that the people of Kao and Nyaro did in fact on occasion notify the Mahdi of advancing Government troops with signal fires, and the new information above corroborates the general tradition that Fungor was, for its treachery, on at least two occasions the focus of the wrath of the Mahdi.

II. The Politics of Rain Control Among the Uduk

Wendy James

Professor Evans-Pritchard’s earliest fieldwork was in the southern Funj region in 1926–7; and in his reports many questions are raised which have not yet been given the attention they deserve. For example, he records in several parts of the region the importance attached to rounded stones, symbolic objects which have been noted in various parts of the Sudan,[33] especially in connection with rain. Unluckily, Professor Evans-Pritchard became ill and was unable to complete his investigations. However, even after the short time he had available for enquiries among the Uduk, he writes:

My single note on their customs consists of a reference to rain-making. I was told that the rain-maker keeps rainstones in a bag and that when he wants rain he makes a hole in the ground and places the stones in it and pours water over them. The stones are then washed and the blood of a sacrificed ox is added to the water. When rain is no longer desired the stones arc covered over in the hole with earth...[34]

It has been my privilege to carry out fieldwork recently in the southern Funj region, particularly among the Uduk-speaking people,[35] and to take up some of the ethnographic problems first posed by Professor Evans-Pritchard. My debt to him is even greater in that he has been my teacher for many years, and it was partly through him that I was drawn in contact with the peoples of the Sudan, at first through the literature and later personally. This essay will deal with some aspects of the significance of attempts to control the weather in Uduk society, of the sort indicated in the quotation above.

In the Kurmuk District live some 10,000 people who speak the Uduk language,[36] mainly in scattered hamlets on the three Khors Ahmar, Tombak and Yabus. They rely largely on the hoe cultivation of dura (sorghum), maize and sesame for subsistence, although some livestock is kept (cattle, goats, chickens and pigs). They conceive of their own social organisation in terms of incorporation by blood into matrilineal clans (wak”), but this tic is complemented by important reciprocal obligations between a person and his father, and father’s clan. The named matrilineal clans arc widely scattered, but within them are exogamous units (also teak’ we may call subclans, which usually form the core of local residential groups. The subclan is a joint cultivating, herding and consuming unit, and is jointly responsible for debts incurred by its members. It is in theory the unit for blood-vengeance.

There is no formal political ascendancy of clans in Uduk society; nor are there formalised positions of leadership, apart from the Omda, sheikhs, officials of the Chali Church (started by the Sudan Interior Mission) and local council representatives, whose authority is derived from outside “traditional” Uduk society. The Uduk area, in regional terms, is a political vacuum: in the context of several local religious cults the Uduk are politically tributary to the Jum Jum and Meban, their northern and western neighbours; in relation to wider questions such as administration and national politics, the villagers on the whole accept the leadership of local merchants and the officials mentioned above. Struggles for influence and ascendancy within Uduk village society take place on a small scale, and are rarely of more than local significance.

However, it is within the context of local political struggles that the main significance of rain-control ritual can be seen. Control over the weather, not only to bring rain necessary to produce the crops, but also to use storms and the threat of damage to lives and property as a means of commanding tribute, co-operation, and the payment of bad debts, is a component of most forms of power as conceived in Uduk thought. It would be misleading to take Uduk rain rites and beliefs and analyse them as a formal system, apart from the way they are actually used in the context of social action. To perform a rain ritual is not simply to carry out a naive “symbolic” act which is supposed to have instrumental efficacy; it is to make a calculated move in a very real game of social and political manoeuvre. That moves in the local power game are often of a “symbolic” character should require no special explanation, as symbolic action is bound up with politics everywhere. Politics is played not only with such obvious symbols as flags, banquets and cricket matches, which may be opposed in the mind to the reality that they symbolise; but also with symbols which are themselves a reality, a means of social articulation and political control. Currency is such a symbol, the circulation of money and financial policy being in themselves the stuff of politics. The hard cash in one’s pocket is of value, but only in relation to the economic and political creditworthiness of one’s country, the nature of which may affect what can be done with one’s money. On a larger scale, financial manipulation may build up or destroy political power. Control over the rain is one of the main idioms through which power relations are worked out in Uduk society; and although rainstones, the main medium of such control, may not be compared with currency directly, their manipulation might be seen as analogous to the higher levels of financial politics. This is certainly not a field of “mere” symbolism, but of real political competition and the building up and destruction of credit.

It would be valuable to know why political symbolism draws so heavily on rain control among the Uduk; but I do not have sufficient historical information to answer this question. This essay attempts to explain how the symbolism of weather control is used today in the southern Funj, particularly within Uduk society, and falls into three parts. Firstly, I consider ecological conditions in relation to the Uduk conception of the nature of rainfall; secondly, I show in general terms how the symbolism of rain-control enters into social and political relations; and thirdly, some case-situations are examined.

I

Geographical and climatic conditions in the southern Funj may certainly be described as marginal for peasant cultivators. The Kurmuk District receives, on average, about 1000 mm. rain each year in the south-east, decreasing to about 800 mm. in the north-west.[37] With the decrease goes increasing irregularity of the showers. Most of the rain falls between mid-May and mid-November, and is brought by south-easterly winds, which having deposited most of their rainfall on the Ethiopian Highlands, have little left by the time they reach this “rain shadow” area. In the villages of the western Kurmuk District, one often waits in bright sunshine for the first few showers to cool the scorched earth, while day after day there are dark clouds and heavy precipitation over the hills to the east.

The Uduk annual cycle is of five seasons, based on the pattern of agricultural work related to the three main crops, dura, maize and sesame. Dura and maize are of approximately equal importance as food grains, and each has different essential rain requirements: maize needs regular showers in the early part of the rainy season (May-July); and dura can survive with less regular showers during the middle, and later, rainy season. Although it often happens that one crop or the other does badly, it is only rarely that both fail. Sesame, which is a subsidiary crop, is used for transactions rather than direct consumption and may be used to purchase food grains if necessary. Although there are various risks to the crops (such as insects, birds, flocks of the nomads who pass through the area, and even village livestock), the shortage or excess of rainfall, its maldistribution, or associated floods are the greatest single worry of the Uduk farmer. Famine conditions are never very far away.

Rain showers are not only irregular in terms of frequency, they are often highly localised and geographically erratic. The region is a fairly uniform plain, drained by wide valleys opening to the west into the White Nile swamps; but there are scattered hills, outliers of the Ethiopian Highlands, rising to five hundred and sometimes a thousand feet above the general level of the plain. This pattern of relief obviously makes for localised showers in the vicinity of the hills. Indeed, the hills are often capped with cloud in the rainy season, and showers seem to spread from them. It is therefore not surprising that rain showers are usually associated with particular hills; and this association becomes significant when it is realised that hamlets, too, are often grouped around hills. One can, under these conditions, sympathise with a farmer whose fields remain dry, in spite of the fact that rain has been visibly falling over several neighbouring hills.

A final characteristic of rain in this region, as indeed in much of the Sudan, is that it very rarely falls in a mild and continuous form. Most of it comes in short, intense downpours, and is often accompanied by wind, thunder and lightning. Such storms are not only dramatic and rather unpleasant; they may cause a good deal of damage. Crops may be battered, trees or huts may be struck by lightning or blown over, and people may be hurt and even killed. Thus, although rain is beneficial and life-giving, it cannot be dissociated from potential danger and destruction. By the very nature of local meteorological conditions, farmers are bound to have a highly ambivalent attitude to the rain.

The Uduk word asho’k, which in some contexts appears to be the equivalent of the English word “rain”, can be fully appreciated only in relation to the local climatic conditions. It has a broader range of reference than “rain”, for which there is no exact translation. Its focus is upon the atmospheric disturbance behind the weather which produces rain, rather than upon the falling water itself. The word can be used equally of heavy clouds, winds, whirlwinds, thunder and lightning, and falling rain. Asho’k manifests itself in all these forms, and is therefore perhaps best rendered by an insubstantial word such as “turbulence” or “storminess”.[38] The concepts of thundering, rain, and so forth are commonly expressed in the Uduk tongue by using the “abstract” noun asho’k with a variety of verbs. Thus, one says asho’k doro’d (the “storm” is beating, or thundering), asho’k mi’da war (the “storm” is making lightning), asho’k hethe’d (the “storm” is raining) or asho’k eke’dayide^ the “storm” is pouring out water; the same verb, ek, can be used with noise, to suggest loudness). At the heart of the turbulence named asho’k, there is sometimes said to be a ball of fire, an idea which makes sense of the action of lightning, and of the way in which dry winds can apparently set huts on fire. In the dry season, and during occasional dry periods in the rainy season, asho’k is said to go into a hole underground. However, it can be active in the drv months, when it causes strong winds and dust devils, o

Iii Uduk thought, disturbed weather is not part of a blind and uncontrollable nature. Turbulence in the atmosphere, so often the home of spiritual powers, is thought to be influenced by the activity of spiritually potent men. I think the Uduk see the interplay of human passions, especially the anger of powerful men, being worked out in the winds and violent clashes of the upper air. This human element in the atmospheric struggle, of which rain is a by-product, is understood in the Uduk word asho,k. Whenever a shower or storm is mentioned, it is never inappropriate to ask, “Whose rain? Whose storm?” (oy^o’Z; maja?) The answer may be, “I don’t know”, or “Probably God’s rain” (asho’k ma rum); but as often as not an individual, or a group of people, will be named as a possible source. I have seen men furiously shouting directly up at the heavens in a downpour, urging their own rainstones to ward off the danger from those of their adversaries.

II

Control over the weather is one of the commonest forms which power in Uduk society is thought to take. Most influential people, even though they are not primarily responsible for the rain, have nevertheless a certain effect on it, which may be beneficial or harmful. Diviners fari) for example, possess small stones which they wash and anoint in various curative rituals, and this incidentally encourages the rain. The anger or ill-will of any ritual specialists can inhibit the rain. The tribute and respect paid to Meban religious leaders is rationalised in terms of the need to please them to avoid the danger of drought. When missionaries began work at Chali, they were suspected of trying to prevent the rain from falling.[39] He who controls the rain, possesses a double-edged power to bless or to curse; and this quality, derived from the nature of rainfall itself, makes it a particularly suitable idiom for the symbolic expression of political power, also ambivalent in character.