• Ted Kaczynski’s 1978–79 Journal

• Ted Kaczynski’s Letter Correspondence With David Skrbina

James F. Kirkham, Sheldon G. Levy & William J. Crotty

Assassination and Political Violence, Vol. 8

A Report to the National Commission on the Cause and Prevention of Violence

Statement on the Staff Studies

Task Force on Assassination and Political Violence

Conceptual and Structural Analysis of Assassination

B. Categories of Assassination

C. Preconditions for Assassination’

D. The Impact of Assassinations on Government Institutions and Policy

Chapter 1: Deadly Attacks Upon Public Officeholders in the United States

B. Case Method Discussion of Assassinations

Assassinations of State Legislators

C. Conclusions and Statistical Overview

Chapter 2: Assassination Attempts Directed at the Office of the President of the United States

A. Presidential Assassination Attempts

B. The Psychology of Presidential Assassins

1. Similarities between Presidential Assassins

2. A Comparison of the Presidential Assassin and the Normal Citizen

C. A Psychiatric Perspective Upon Public Reaction To the Murder of a President.

D. A Survey of Public Reaction to Assassinations

1. Emotional Responses of Specific Groups to Assassination

3. Polarized Subgroup Analysis

E. Political Consequences Traceable to Assassination of Presidents of the United States

F. Strategies for the Reduction of Presidential Assassinations

1. Protection of the President

The Press and the Presidential Symbol

3. Campaign Style and the Risk of Assassination

G. The Presidency and Assassination: Suggestions and Conclusions

5. The Federal System Generally

Chapter 3: Cross-National Comparative Study of Assassination

A. Assassination: A Cross-National Quantitative Perspective

B. Political Violence and Assassination

C. Violence, Assassination, and Political Variables

1. Level of Development and Political Violence

2. Systemic Frustration—Satisfaction and Political Violence

3. Rate of Socioeconomic Change and Political Violence

4. Coerciveness of Political Regimes and Political Violence

5. External Aggression, Minority Tension, Homicide, and Suicide

Chapter 4: Political Violence in the United States

A. Historical Overview of Political Violence in the United States

2. Abolitionsim and Anti-Abolitionism

3. Reimposing White Supremacy in the South after the Civil War (the First Ku Klux Klan)

7. Political Violence in Contemporary America

c. The Extreme Right and the New Left

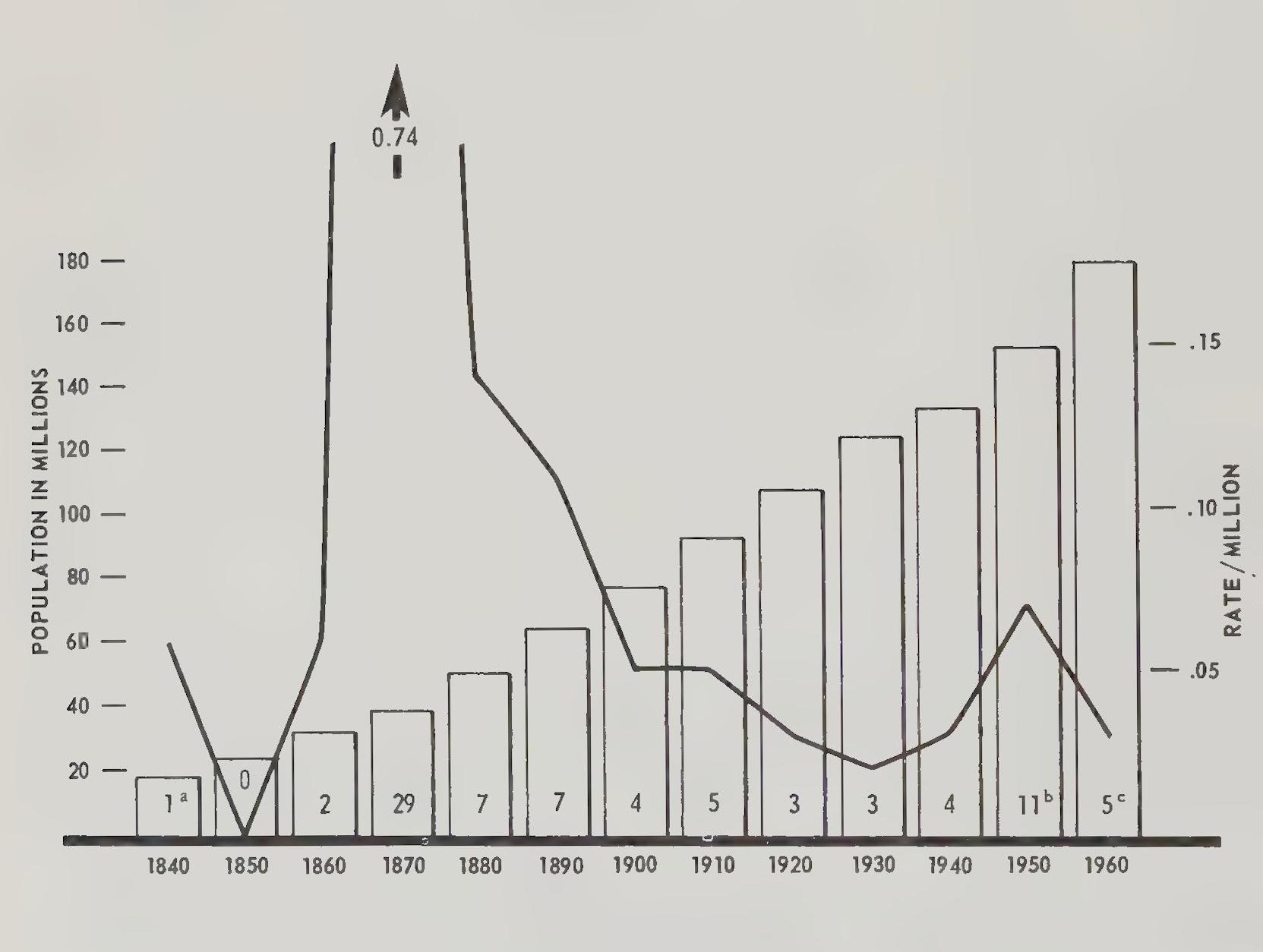

B. Historical Comparison of the Intensity of Political Violence in the United States

General Summary of the Newspaper Study

C. Profile of Support Within the United States for Political Violence

1. Analysis of Groups Whose Attitudinal Responses Indicate Support for Political Violence

3. Political Vengeance and Other Types of Violence: An Attempt at Validation of the Measure

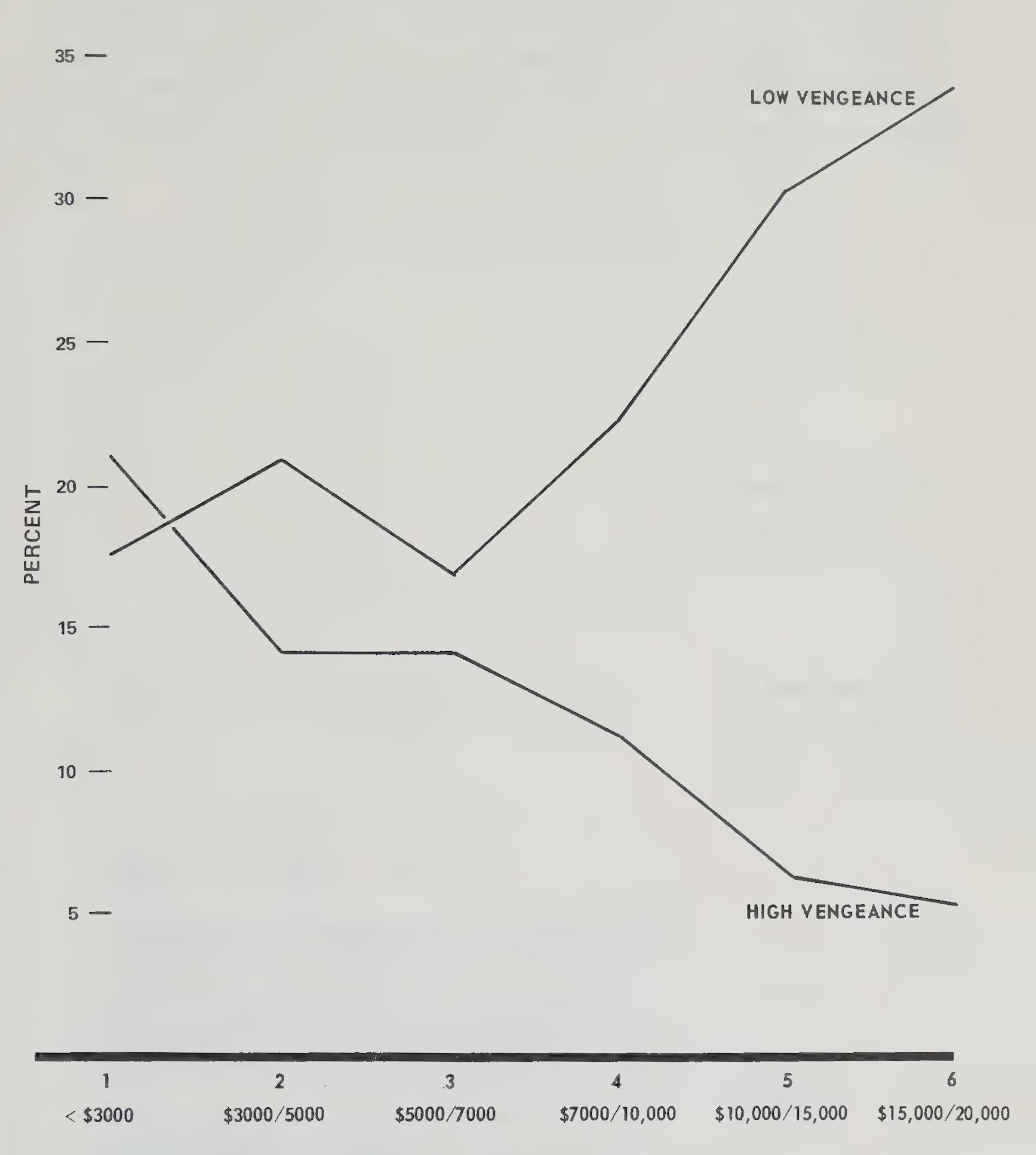

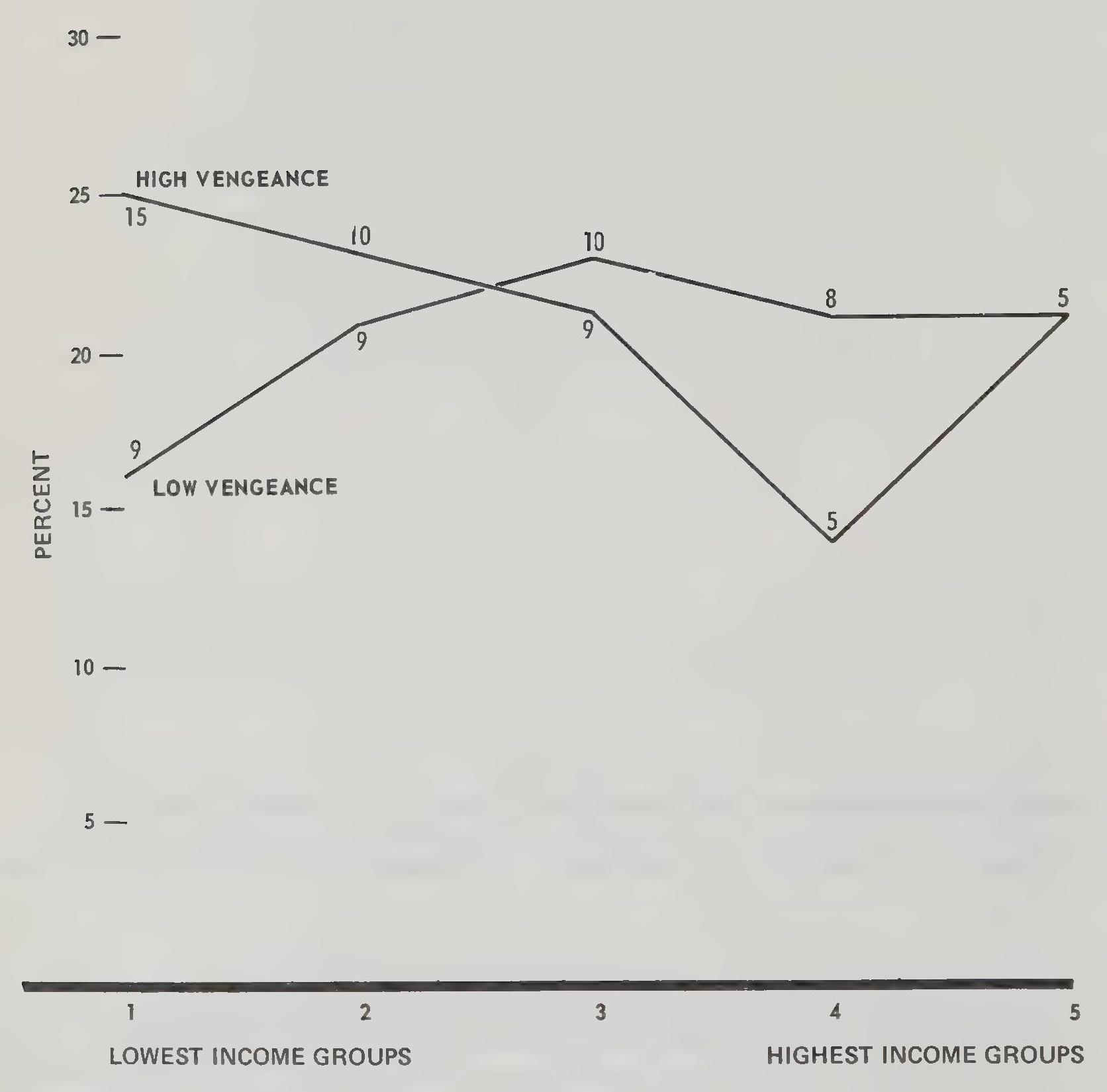

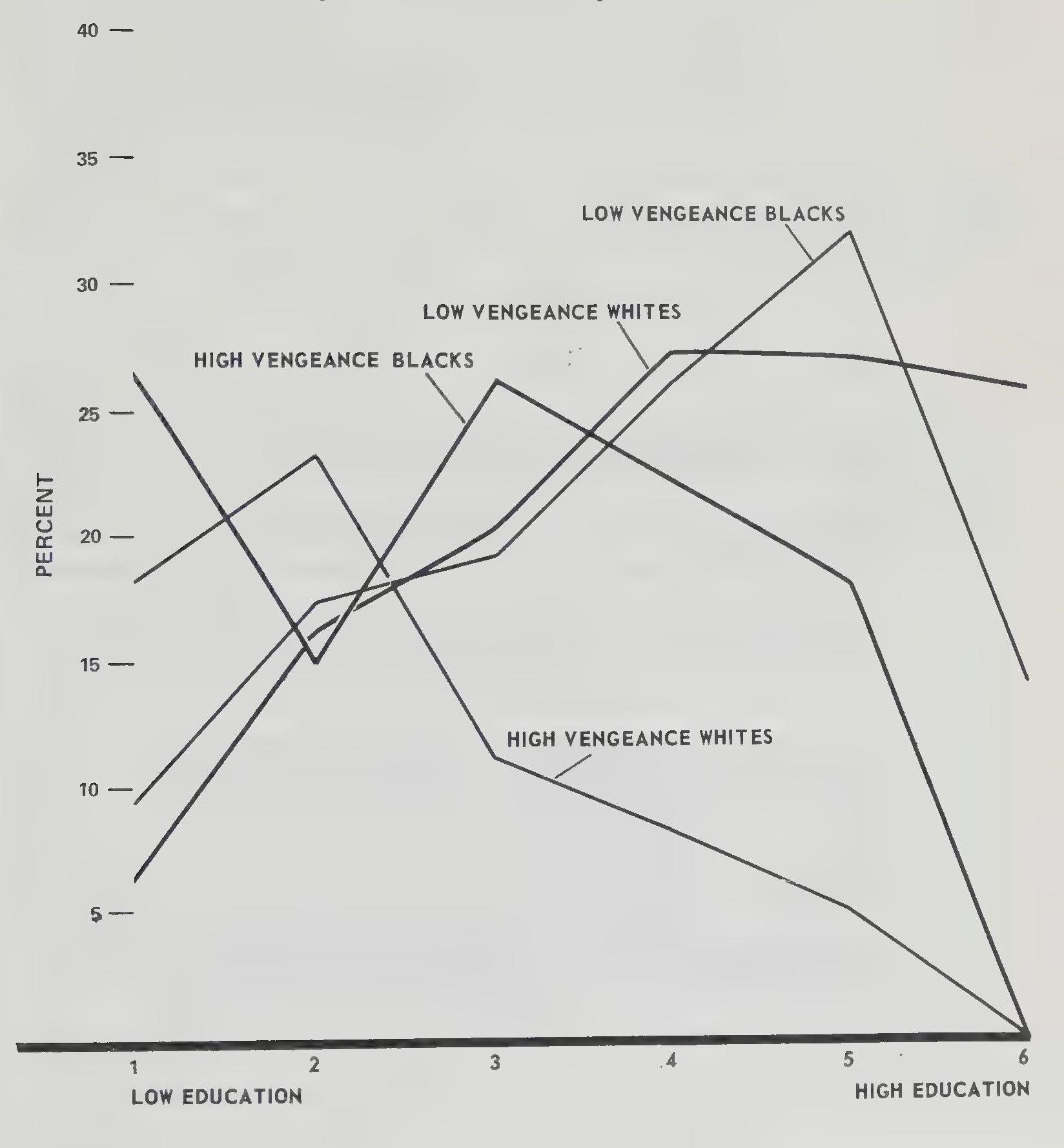

4. Analysis of the Social Structural Characteristics of the “Politically Vengeant”

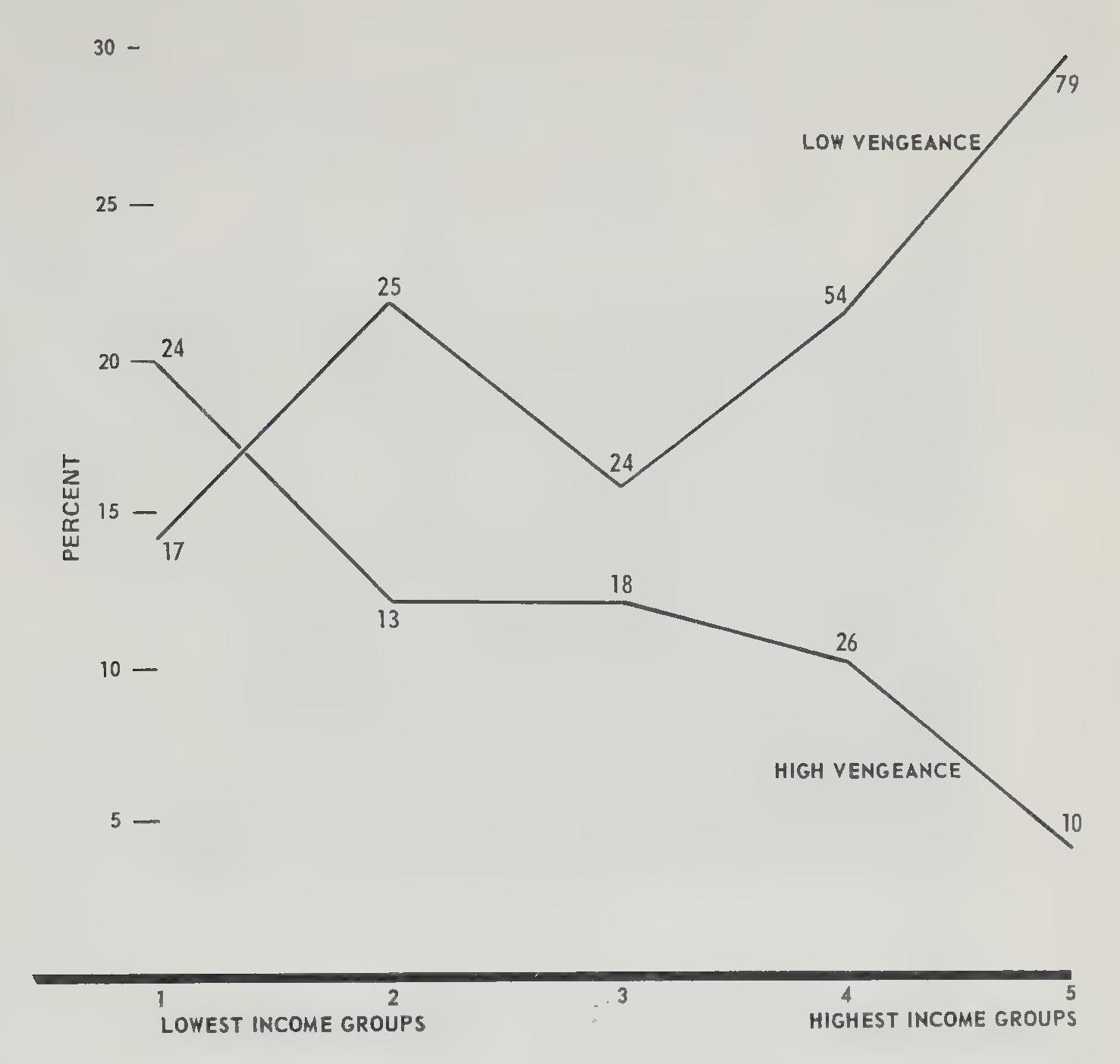

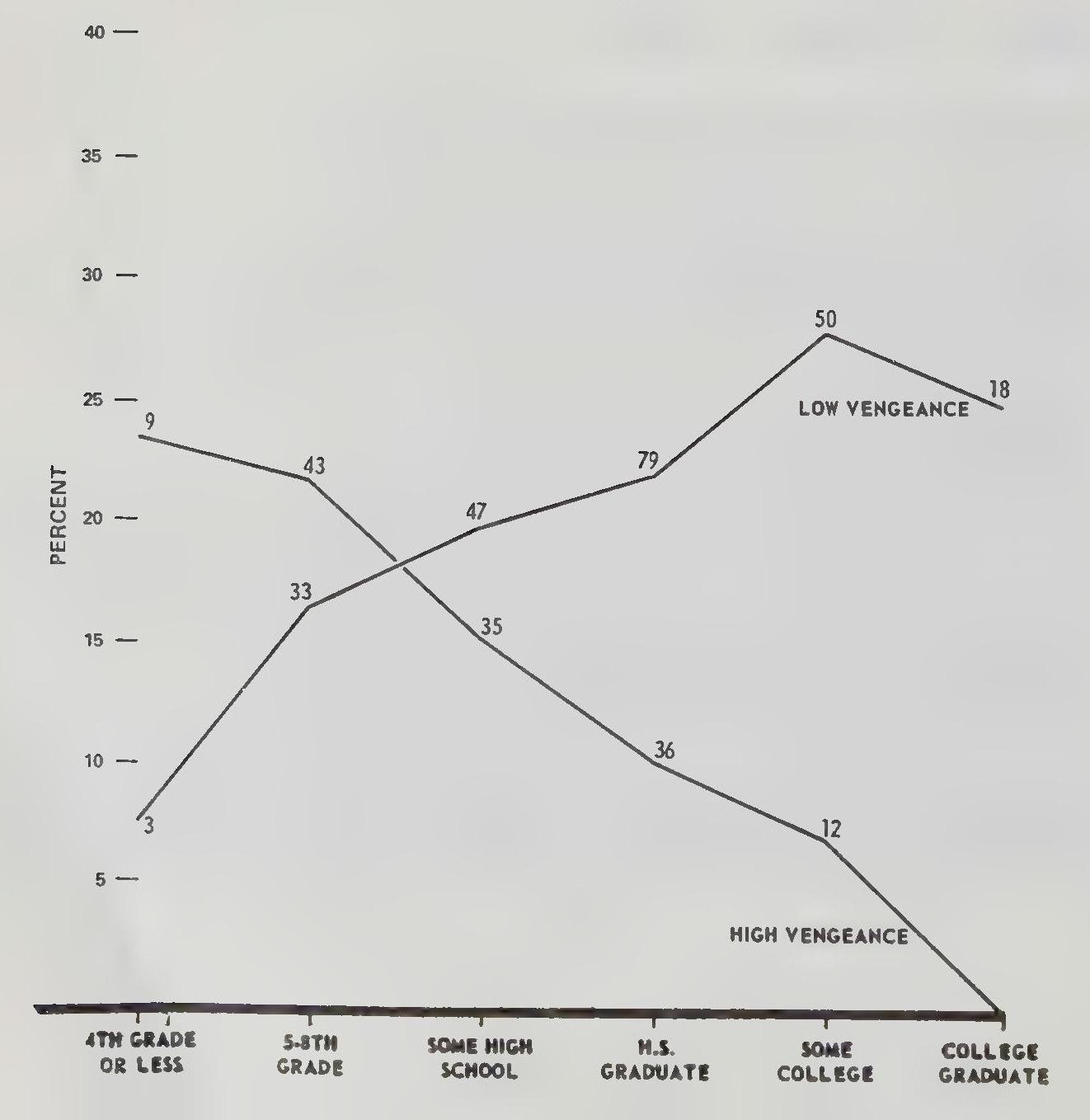

5. Demographic Correlates of Political Vengeance

6. Vengence and the Political System: Party Identification and Policy Orientation

a. America’s Presidential Elections

b. Vengeance and Position on Political Issues

c. Conclusions to Political Vengeance Analysis

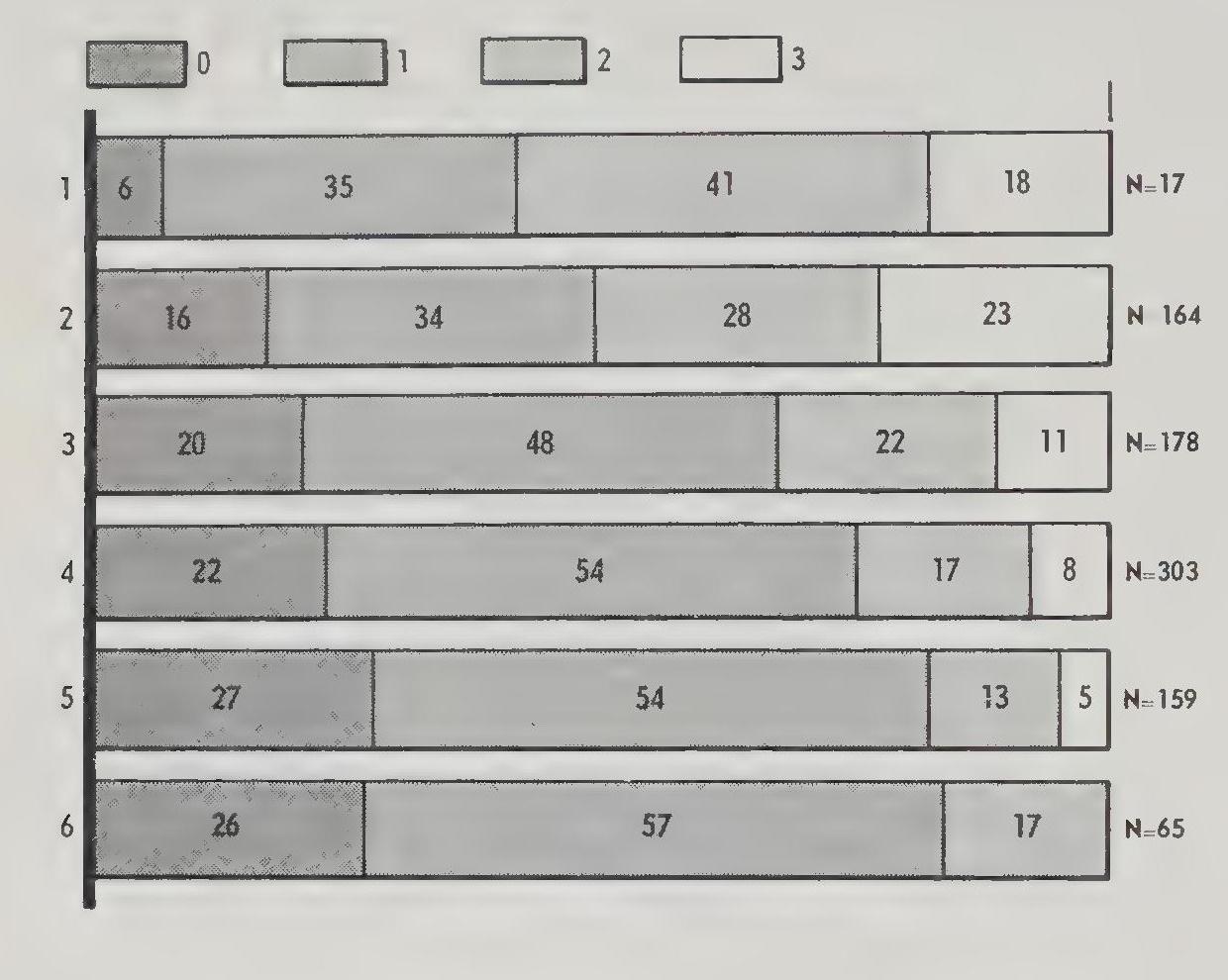

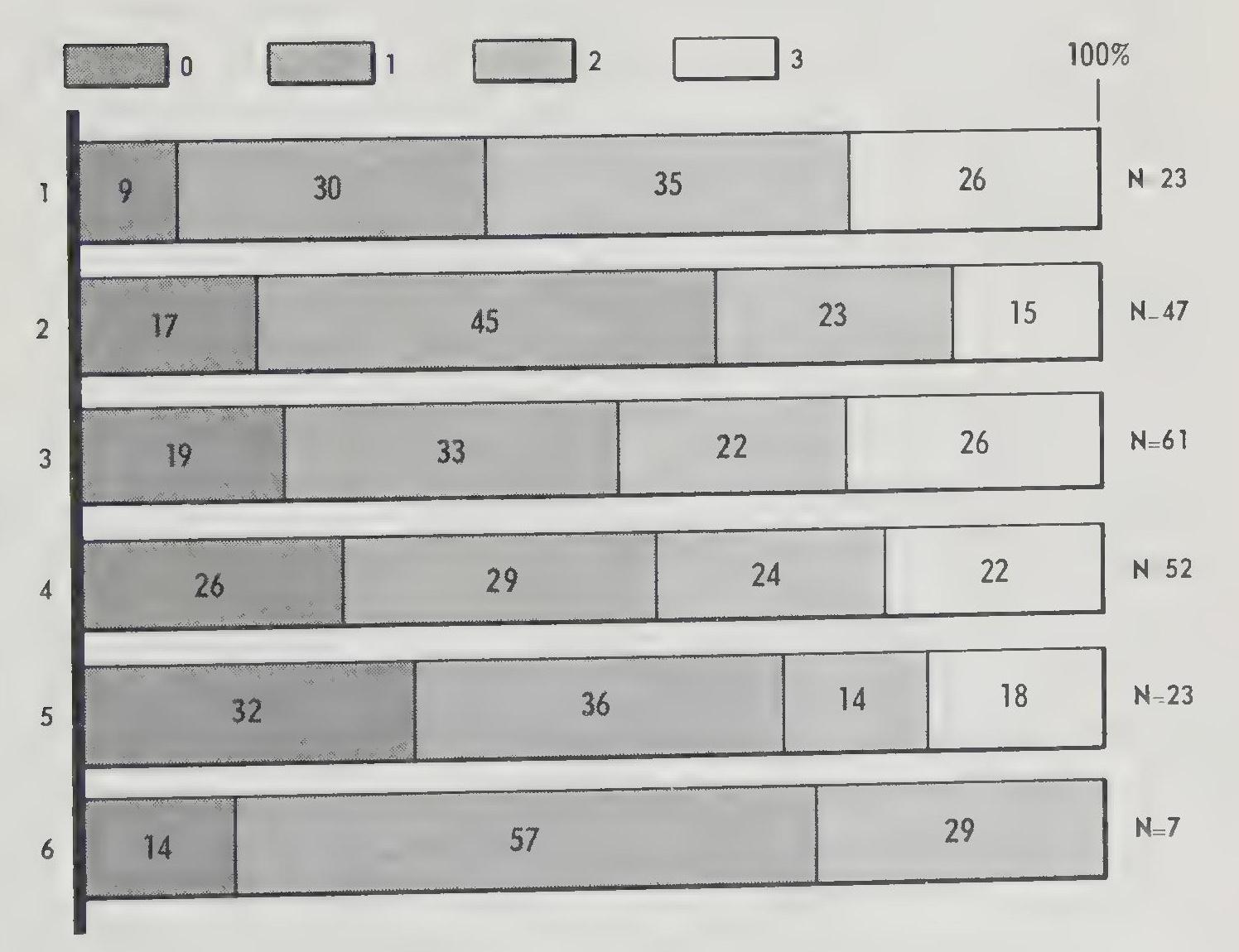

Item-by-item analysis of responses to perceived governmental injustice.

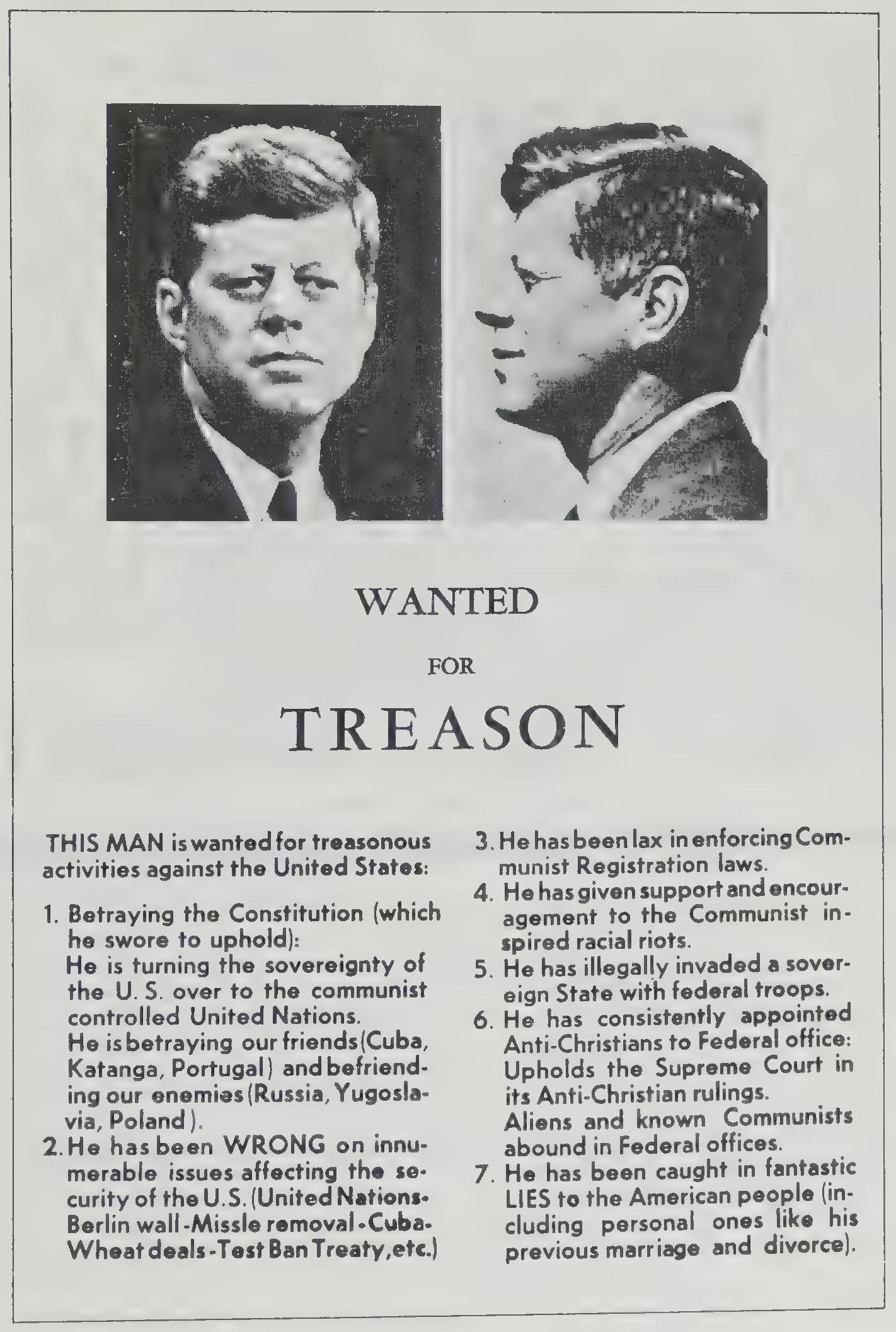

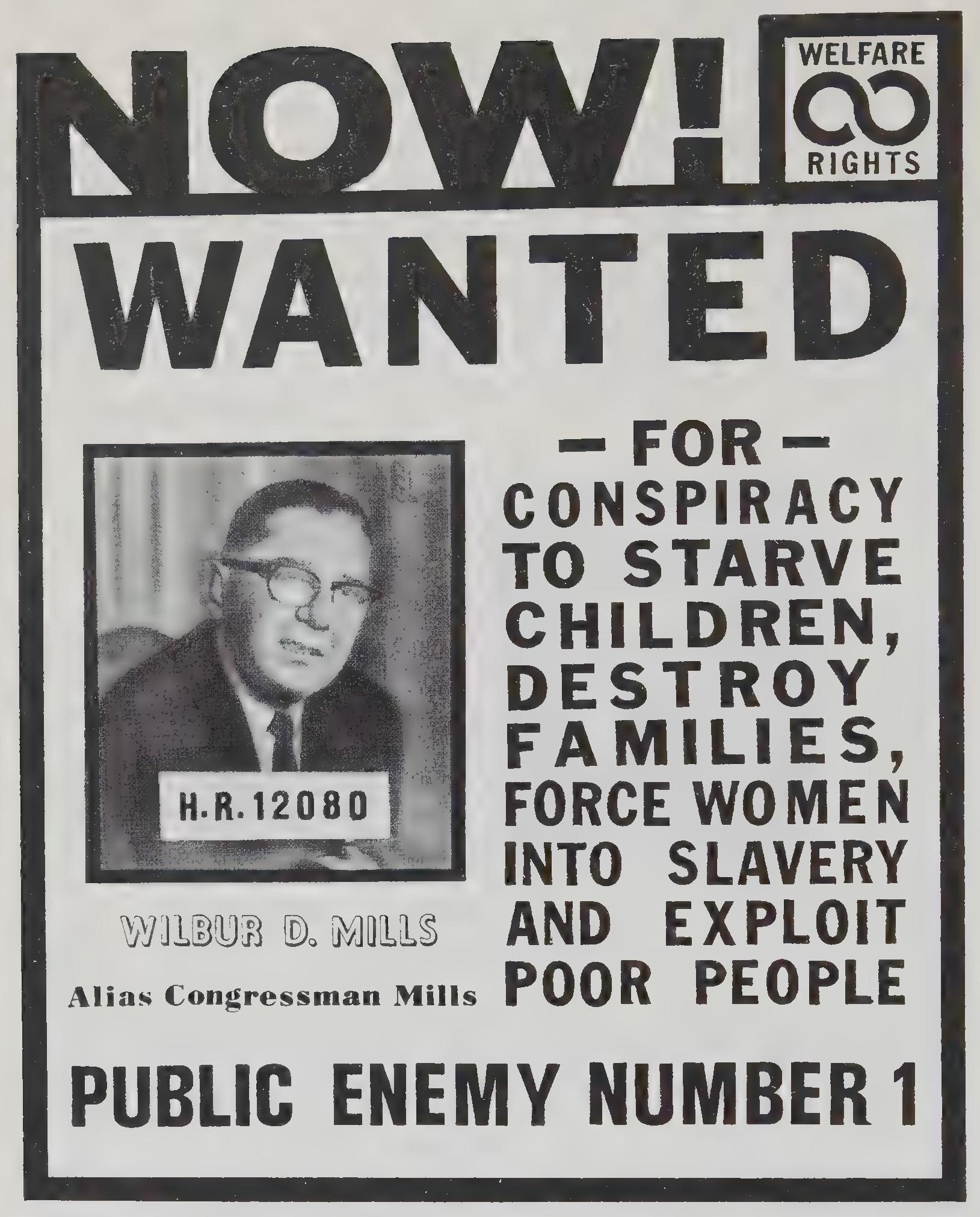

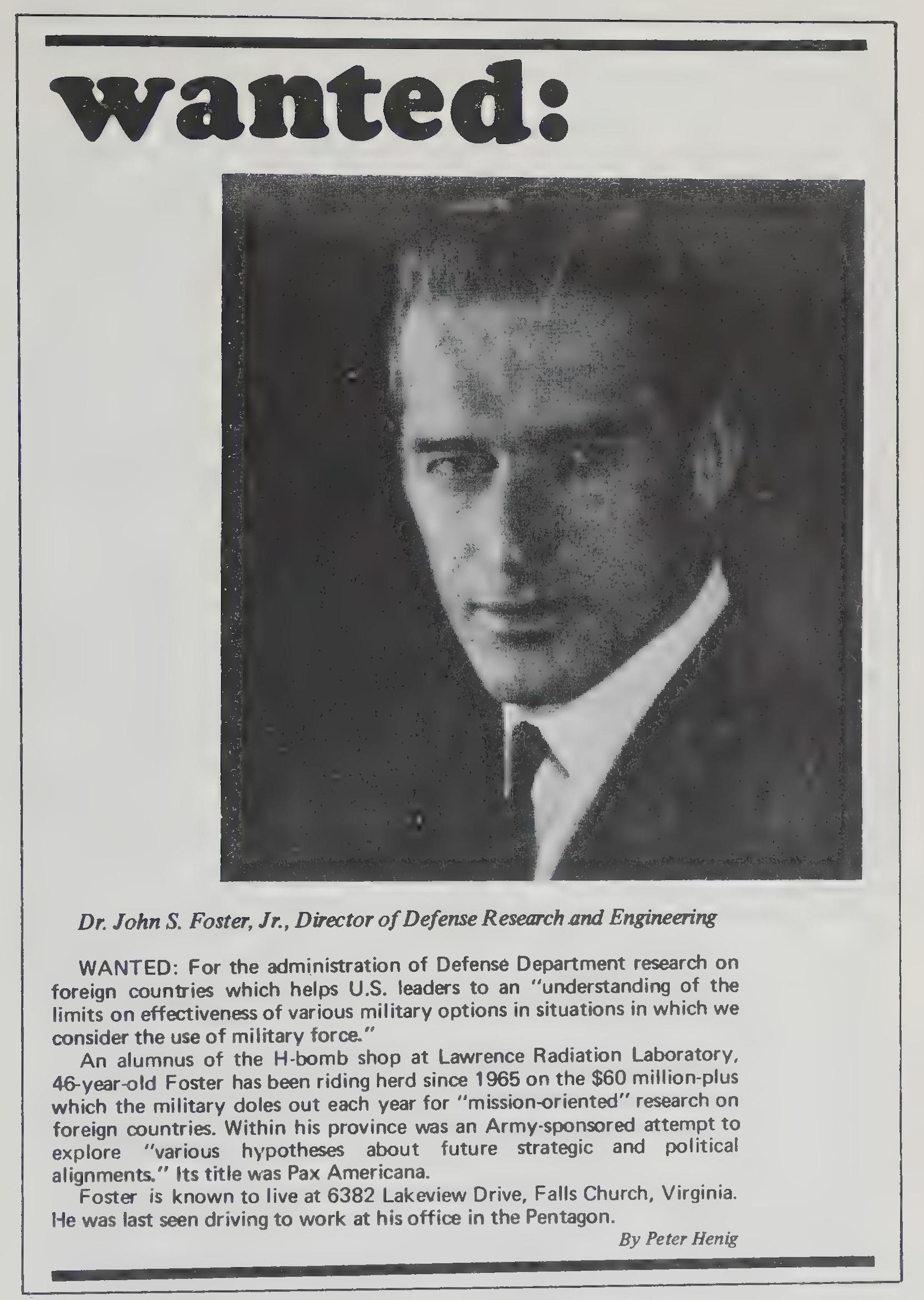

D. The Rhetoric of Vilification and Violence in Contemporary America

E. Two Contemporary Violent or Potentially Violent White Vigilante-Type Groups

1. North Carolina Ku Klux Klan (White Ghetto)

White and. Black Ghettos: Similarities and Differences

2. North Ward Citizen’s Council (Urban Backlash)

F. Summary: Cultural Origins and Impact of Violence

Appendix A: Data on Assassination Events

1. Data Collected by Leiden Group

2. Data Collected by Feierabend Group

Definition of Assassination Event

ASSASSINATION CODE INDEX and EXPLANATORY NOTES

Explanatory Notes: Assassination Code Index

2. Data Collected by Feierabend Group

Appendix B: The Rhetoric of Vilification and Violence

Appendix C: Alienation Today Conveyed Through the Words of Peter Young

Appendix D: The Contemporary Ku Klux Klan

1. The Traditional Perspective

The 1960’s—Klan Membership and Violence on the Rise

2. Violence and the White Ghetto, a View From the Inside Consultant to the Commission

3. Summary of Tapes Made by Peter Young

Interview with exalted Cyclops, Billy Flowers

Interviews With Klan Members, 1965

Tapes of “Segregationist” Records

Interview with Will Campbell, September 1968

Summary of Tony Imperiale Tape

Responses to question from audience after speech

Two views from the “Opposite” Perspective

Interview with Dan Watts (September 1968)

Interview with Paul Krasner (September 1968)

Appendix E: National Survey Questionnaire

Special Research Report: Attitudes Toward Political Violence

2. Dimensions of Psychological Orientation

3. Discussion of Factor Analytic Traits

4. Response To Governmental Injustice

The Governmental Injustice Items

Actions That Individuals Would Take

Political Complaints and Political Action

Supplement A: Political Violence and Terror in 19th and 20th Century Russia and Eastern Europe

2. Types and Function of Terror

“Sultanism” and the Transfer of Power by Assassination

Renaissance: Tyranny and its Political Style

Political Assassination: Systematic and Tactical

Contradictions of Terror and Mass Terror

Historical Pattern of Mass Terror

Tactical and Strategic Objectives of Terror

Terror and Isolated Assassination

From Political Assassination to Tactical Terror

Early Political Assassinations

Beginnings of a Systematic Terroristic Struggle

Motivation and Some of the Determinants

Ideology and Objectives of the Terrorists

The Government’s Reaction to Terror

The Size of the Terroristic Party

Terror and Representative Institutions

4. Violence and Terror against Foreign Rule in Eastern Europe

Origin of the Polish Revolutionary Movement

Absence of Terror in the Austrian Part of Poland

The Nature of Terror in Poland

Opposition to Terror and Direct Action

The Termination of Systematic Terror

Terror by the Armenian Dashnaks as a Defense and Struggle Against Turkish Massacres

Polish and Armenian Terroristic Tactics Compared

5. Political Assassination in Balkan Politics

The Nature of Political Assassination

Dynastic Feuds and Assassinations

The Black Hand and the Assassination of Archduke Ferdinand

Professionalization and Institutionalization of Terror

The Komitadji of Macedonia and Terroristic Action

6. From the Terror of the Totalitarians to the Underground Struggle Against Conquerors, 1918–1945

The Political Situation, 1918–1945

Former Terrorist Parties and Revolution in Russia

Former Fighters and Democracy in Poland

Former Komitadji in a New Bulgaria

Effect of Former Patterns of Violence on the Political Behavior of Leaders

Significance of the Political Situation

New and Old Patterns of Political Assassination

Isolated Political Assassination and Tactical Terror in Poland

Yugoslavia and the Ustasha; Assassinations of King Alexander and Stephen Radic

The Rumanian Iron Guard and Terror-Assassinations of lorga, Duca, and Others

World War II: Tactical Terror and Resistance

The Polish Underground and Legitimation of Terror

7. Overview: Russian Balkan, and Polish Terrorism

Causes of Terror Against Autocracy and Foreign Rule

MODEL A: Causation of Tactical Terroristic Acts Against Foreign Rule or Autocracy

Causation of Terror Against Democracy: the Preassassination Stage

MODEL B: Causation of Individual Violence as a Tactic

Duration of Tactics of Individual Terror Against Autocracy and Foreign Rule (Approximations)

Duration of Terroristic Tactics Against Democracy and Moderate Governments (Approximations)

Diffusion of the Terroristic Pattern

Supplement B: Assassination and Political Violence in 20th Century France and Germany

3. Political Violence in the Early Weimar Republic

The Kapp Putsch, March 12–17, 1920

The Ruhr Revolt, March-April 1920

Leftist Outbreak in Saxony, October 1923

The Munich “Beer Cellar Putsch,” November 8–9, 1923

The Episode of Rhineland Separatism

4. The German Political Crisis, 1929–33

The Sanctioning of Internal Violence

The Use of Violence in Establishing the Dictatorship

Continued Anti-Semitic Excesses

6. Anti-Hitler Plots and Assassination Attempts

Supplement C: Political Assassinations in China, 1600–1968

2. Political Assassinations in China, 1600–1968

d. The Communist Period, 1949–68

3. Politics and Political Assassination in Traditional China

b. Assassinations in the Warlord Period

c. Gun Availability in Pre-Republican China

4. On the Legitimation of Assassination of Chinese Officials

5. The Impact and Effectiveness of Assassination in China

6. A Postscript: Some Relevant Comparisons on Political Assassinations in China and the U.S.

Supplement D: Assassination in Japan

4. Effectiveness of Assassination

Supplement E: Assassination in Latin America

3. The Impact of Assassination on Political Systems

4. Effectiveness of Assassination as a Political Technique

Supplement F: Assassination in the Middle East

4. The Impact of Assassination

5. The Effectiveness of Assassination

Supplement G: Assassination and Political Violence in Canada

2. Problem of Canadian Identity

3. Historical Context of Political Violence in Modern Canada

From Louis Riel to Modern Separatism

Supplement H: Assassination in Great Britain

Supplement I: Assassination in Australia

Supplement J: Assassination in Finland

[Front Matter]

[Executive Order #11412]

The White House

June 10. 1968

EXECUTIVE ORDER #11412

ESTABLISHING A NATIONAL COMMISSION ON

THE CAUSES AND PREVENTION OF VIOLENCE

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, it is ordered as follows

SECTION 1. Establishment of the Commission (a) There is hereby established a National Commission on theCausesand Prevention of Violence (hereinafter referred to as the “Commission”).

(b) The Commission shall be composed of

SECTION 2. Functions of the Commission The Commission shall investigate and make recommendations with respect to

(a) The causes and prevention of lawless acts of violence in our society, including assassination, murder and assault;

(b) The causes and prevention of disrespect for law and order, of disrespect for public officials, and of violent disruptions of public order by individuals and groups: and

(c) Such other matters as the President may place before the Commission.

SECTION 4. Staff of the Commission

SECTION 5. Cooperation by Executive Departments and Agencies

(a) The Commission, acting through its Chairman, is authorized to request from any executive department or agency any information and assistance deemed necessary to carry out its functions under this Order. Each department or agency is directed, to the extent permitted by law and within the limits of available funds, to furnish information and assistance to the Commission.

SECTION 6. Report and Termination The Commission shall present its report and recommendations as soon as practicable, hut not later than one year from the date of this Order. The Commission shall terminate thirty days following the submission of its final report or one year from the date of this Order, whichever is earlier.

S/Lyndon B. Johnson

--Added by an Executive Order June 21, 1968

[Executive Order #11469]

The White House

May 23, 1969

EXECUTIVE ORDER #11469

EXTENDING THE LIFE OF THE NATIONAL COMMISSION ON THE CAUSES ANO PREVENTION OF VIOLENCE

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, Executive Order No. 11412 of June 10, 1968,entitled “Establishing a National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence,” is hereby amended bv substituting for the last sentence thereof the following. “The Commission shall terminate thnty days following the submission of its final report or on December 10. 1969. whichever is earlier.”

S’ Richard Nixon

[Title Page]

ASSASSINATION

AND

POLITICAL VIOLENCE

VOL 8

A Report to the

National Commission on

the Causes and Prevention of

Violence

James F. Kirkham

Sheldon G. Levy

William J. Crotty

October 1969

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402 — Price $2.50

[Public Domain]

Official editions of publications of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence may be freely used, duplicated or published, in whole or in part, except to the extent that, where expressly noted in the publications, they contain copyrighted materials reprinted by permission of the copyright holders. Photographs may have been copyrighted by the owners, and permission to reproduce may be required.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74–603981

Statement on the Staff Studies

The Commission was directed to “go as far as man’s knowledge takes” it in searching for the causes of violence and the means of prevention. These studies are reports to the Commission by independent scholars and lawyers who have served as directors of our staff task forces and study teams; they are not reports by the Commission itself. Publication of any of the reports should not be taken Io imply endorsement of their contents by the Commission, or by any member of the Commission’s staff, including the Executive Director and other staff officers, not directly responsible fur the preparation of the particular report. Both the credit and the responsibility fur the reports he in each case with the directors of the task forces and study teams. The Commission is making the reports available at this tune as works of scholarship to be judged on their merits, so that the Commission as well as the public may have the benefit of both reports and informed criticism and comment on their contents.

Dr. Milton S. Eisenhower. Chairman

Task Force on Assassination and Political Violence

Co-Directors

James F. Kirkham

Sheldon G. Levy

William J. Crotty

Staff

Robert C. Herr

Robert C. Nurick

Linda G. Stone

Secretary

Vicky Clinton

Editor

Anthony F. Abell

Commission Staff Officers

Lloyd N. Cutler,Executive Director

Thomas D. Barr, Deputy Director

James F. Short, Jr., Marvin E. Wolfgang, Co-Directors of Research

James S. Campbell, General Counsel

William G McDonald, Administrative Officer

Ronald Wolk, Special Assistant to the Chairman

Joseph Laitin, Director of Information

National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence

Dr. Milton S. Eisenhower, Chairman

Preface

From the earliest days of organization, the Chairman, Commissioners, and Executive Director of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence recognized the importance of research in accomplishing the task of analyzing the many facets of violence in America. As a result of this recognition, the Commission has enjoyed the receptivity, encouragement, and cooperation of a large part of the scientific community in this country. Because of the assistance given in varying degrees by scores of scholars here and abroad, these Task Force reports represent some of the most elaborate work ever done on the major topics they cover.

The Commission was formed on June 10, 1968. By the end of the month, the Executive Director had gathered together a small cadre of capable young lawyers from various Federal agencies and law firms around the country. That group was later augmented by partners borrowed from some of the Nation’s major law firms who served without compensation. Such a professional group can be assembled more quickly than university faculty because the latter are not accustomed to quick institutional shifts after making firm commitments of teaching or research at a particular locus. Moreover, the legal profession has long had a major and traditional role in Federal agencies and commissions.

In early July a group of 50 persons from the academic disciplines of sociology, psychology, psychiatry, political science, history, law, and biology were called together on short notice to discuss for 2 days how best the Commission and its staff might proceed to analyze violence. The enthusiastic response of these scientists came at a moment when our Nation was still suffering from the tragedy of Senator Kennedy’s assassination.

It was clear from that meeting that the scholars were prepared to join research analysis and action, interpretation, and policy. They were eager to present to the American people the best available data, to bring reason to bear where myth had prevailed. They cautioned against simplistic solutions, but urged application of what is known in the service of sane policies for the benefit of the entire society.

Shortly thereafter the position of Director of Research was created. We assumed the role as a joint undertaking, with common responsibilities. Our function was to enlist social and other scientists to join the staff, to write papers, act as advisers or consultants, and engage in new research. The decentralized structure of the staff, which at its peak numbered 100, required research coordination to reduce duplication and to fill in gaps among the original seven separate Task Forces. In General, the plan was for each Task Force to have a pair of directors: one a social scientist, one a lawyer. In a number of instances, this formal structure bent before the necessities of available personnel but in almost every case the Task Force work program relied on both social scientists and lawyers for its successful completion. In addition to our work with the seven original Task Forces, we provided consultation for the work of the eighth “Investigative” Task Force, formed originally to investigate the disorders at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions and the civil strife in Cleveland during the summer of 1968 and eventually expanded to study campus disorders at several colleges and universities.

Throughout September and October and in December of 1968 the Commission held about 30 days of public hearings related expressly to each of the Task Force areas. About 100 witnesses testified, including many scholars, Government officials, corporate executives as well as militants and activists of various persuasions. In addition to the hearings, the Commission and the staff met privately with scores of persons, including college presidents, religious and youth leaders, and experts in such areas as the media, victim compensation, and firearms. The staff participated actively in structuring and conducting those hearings and conferences and in the questioning of witnesses.

As Research Directors, we participated in structuring the strategy of design for each Task Force, but we listened more than directed. We have known the delicate details of some of the statistical problems and computer runs. We have argued over philosophy and syntax; we have offered bibliographical and other resource materials, we have written portions of reports and copy edited others. In short, we know the enormous energy and devotion, the long hours and accelerated study that members of each Task Force have invested in their labors. In retrospect we are amazed at the high caliber and quantity of the material produced, much of which truly represents, the best in research and scholarship. About 150 separate papers and projects were involved in the work culminating in the Task Force reports. We feel less that we have orchestrated than that we have been members of the orchestra, and that together with the entire staff we have helped compose a repertoire of current knowledge about the enormously complex subject of this Commission.

That scholarly research is predominant in the work here presented is evident in the product. But we should like to emphasize that the roles which we occupied were not limited to scholarly inquiry The Directors of Research were afforded an opportunity to participate in all Commission meetings. We engaged in discussions at the highest levels of decisionmaking, and had great freedom in the selection of scholars, in the control of research budgets, and in the direction and design of research. If this was not unique, it is at least an uncommon degree of prominence accorded research by a national commission.

There were three major levels to our research pursuit: (1) summarizing the state of our present knowledge and clarifying the lacunae where more or new research should be encouraged; (2) accelerating known ongoing research so as to make it available to the Task Forces; (3) undertaking new research projects within the limits of time and funds available. Coming from a university setting where the pace of research is more conducive to reflection and quiet hours analyzing data, we at first thought that completing much meaningful new research within a matter of months was most unlikely But the need was matched by the talent and enthusiasm of the staff, and the Task Forces very early had begun enough new projects to launch a small university with a score of doctoral theses. It is well to remember also that in each volume here presented, the research reported is on full public display and thereby makes the staff more than usually accountable for their products.

One of the very rewarding aspects of these research undertaking has been the experience of minds trained in the law mingling and meshing, sometimes fiercely arguing, with other minds trained in behavioral science. The organizational structure and the substantive issues of each Task Force required members from both groups. Intuitive judgment and the logic of argument and organization blended, not always smoothly, with the methodology of science and statistical reasoning. Critical and analytical faculties were sharpened as theories confronted facts. The arrogance neither of ignorance nor of certainty could long endure the doubts and questions of interdisciplinary debate. Any sign of approaching the priestly pontification of scientism was quickly dispelled in the matrix of mutual criticism. Years required for the normal accumulation of experience were compressed into months of sharing ideas with others who had equally valid but differing perspectives Because of this process, these volumes are much richer than they otherwise might have been.

Partly because of the freedom which the Commission gave to the Directors of Research and the Directors of each Task Force, and partly to retain the full integrity of the research work in publication, these reports of the Task Forces are in the posture of being submitted to and received by the Commission. These are volumes published under the authority of the Commission, but they do not necessarily represent the views or the conclusions of the Commission. The Commission is presently at work producing its own report, based in part on the materials presented to it by the Task Forces. Commission members have, of course, commented on earlier drafts of each Task Force, and have caused alterations by reason of the cogency of their remarks and insights. But the linal responsibility for what is contained in these volumes rests fully and properly on the reserch staffs who labored on them.

hi this connection, we should like to acknowledge the special leadership of the Chairman, Dr. Milton S. Eisenhower, in formulating and supporting the

principle of research freedom and autonomy under which this work has been conducted.

We note, finally, that these volumes are in many respects incomplete and tentative. The urgency with which papers were prepared and then integrated into Task Force Reports rendered impossible the successive siftings of data and argument to which the typical academic article or volume is subjected. The reports have benefited greatly from the counsel of our colleagues on the Advisory Panel, and from much debate and revision from within the staff. It is our hope, that the total work effort of the Commission staff will be the source and subject of continued research by scholars in the several disciplines, as well as a useful resource for policymakers. We feel certain that public policy and the disciplines will benefit greatly from such further work.

To the Commission, and especially to its Chairman, for the opportunity they provided for complete research freedom, and to the staff for its prodigious and prolific work, we, who were intermediaries and servants to both, arc most grateful.

Acknowledgments

This Report is necessarily not the work of any one person; it draws together the contributions of many diverse scholars recruited by the Task Force. Accordingly, the Report has breadth of approach and diversity of viewpoint on the many facets of assassination and political violence.

For example, approaches include psychiatric post facto examinations of previous assassins; descriptive and historical treatments of assassinations; quantitative comparative analyses of the relationship between acts of political violence and assassinations and the occurrence of assassinations cross-nationally; interpretive discussions of aspects of United States culture which may support violence and, more specifically, violence directed against prominent individuals in the society; and contemporary reports of groups whose rhetoric and previous activities are associated with a variety of kinds of politically violent acts. Each approach contributes a different vantage point from which to examine assassinations and political violence.

The Task Force staff has brought the materials together and has presented them in three major parts: the report itself, Appendices to the report, and a Supplement to the Report. The Appendices contain materials that document in greater detail many of the points raised in the Report, including much of the unrefined data employed in the analyses contained within the Report. The Supplement presents more intensive historical and interpretative explorations of political assassinations in other countries and other regions of the world. These studies, along with the quantitative analyses of comparative aspects of violent behavior, assist in placing the experience of the United States in a world context.

In commissioning studies for the Task Force Report, the codirectors attempted to include reports by individuals distinguished in their understanding of the topic in question. The final Report of the Task Force is based on these studies, many of which are incorporated in whole or in part. In a few cases, the editing has been relatively severe. In all cases, at least some minor editorial changes have been made by the staff. In each instance, however, the original author has been identified and the extent of his contribution to the Report described as accurately as possible. In addition, some sections were written entirely by the staff, including much of the introductory and explanatory material. Thus, the result is neither a book of selected readings by different authors nor a presentation which is homogeneous in style and viewpoint. We have instead attempted to combine the different approaches and viewpoints within a systematic structure. This will enable us to treat the resulting product as a whole and draw conclusions based upon all the different approaches to the subject matter.

The codirectors of Task Force I, Assassination and Political Violence, wish to extend their sincere thanks to the Commissioners and the administrative staff of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence for their constant help, support, suggestions, and contributions to this report. Essential to all the Task Force Reports, and to this report in particular, was the continuing loyal support of the Executive Director, Lloyd N. Cutler. In addition, we wish to acknowledge a special debt to the Commission’s codirectors of research, Dr. James F. Short, Jr., and Dr. Marvin E. Wolfgang, and the Commission’s indefatigable administrative officer, Col. William G. McDonald. To single out particular staff members, however, is necessarily unfair. All worked well beyond what could be reasonably expected in helping this and the other Task Forces.

This Report would not exist but for the consultants to the Task Force, and we should like at this point to acknowledge the contributions of each.

Reports submitted by the following were directly drawn upon in one form or another in the text of the Report; as with all consultant papers, some editing was done by the staff.

| Consultant | Project Title |

|

Richard Maxwell Brown Department of History College of William and Mary |

Violence in American History. |

|

Ivo K. Feierabend Rosalind Feierabend Betty A. Nesvold Franz N. Jaggar Department of Political Science San Diego State College San Diego, Calif. |

Political Violence and Assassination: A Cross-National Assessment--1948-1968 |

| Lawrence Z. Freedman, M.D. Department of Psychiatry University of Chicago | Assassins of Presidents of the United States: Their Motives and Personality Traits |

|

Clinton E. Grimes Judith H. Grimes Department of Political Science University of Idaho Moscow, Idaho |

Personalism, Partisanship, and Assassination |

|

Feliks Gross Department of Sociology Brooklyn College |

Political Violence and Terror in 19th and 20th Century Russia and Eastern Europe |

|

Carl Leiden Murray C. Havens Karl M. Schmitt James Soukup Department of Government University of Texas Austin, Tex. |

Assassinations Worldwide 1918–1969 |

|

James McEvoy III Department of Sociology University of California, Davis And Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley |

Components of Political Violence |

|

Rita J. Simon Department of Sociology University of Illinois Urbana, Ill. |

Political Violence Directed at Public Office Holders: A Brief Analysis of the American Scene |

|

Peter B. Young Summit, N.J. |

Whose Law, Whose Order? |

|

Doris Y. Wilkinson Jerry A. Gaines Department of Sociology University of Kentucky Lexington, Ky. |

Sociological Insights into the Assassin |

|

Jerome Bakst Anti-Defamation League New York, N.Y. |

Political Extremism and Violence in the United States |

Reports from the following are reprinted in the Supplement:

|

Harold Deutsch Department of History University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minn. |

Assassination and Political Violence in 20th Century France and Germany |

|

Feliks Gross Department of Sociology Brooklyn College New York, N.Y. |

Political Violence and Terror in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Russia and Eastern Europe |

|

Murray C. Havens Department of Government University of Texas Austin, Tex. |

Assassination in Australia |

|

Carl Leiden Department of Government University of Texas Austin, Tex. |

Assassinations in the Middle East |

|

Karl M. Schmitt Department of Government University of Texas Austin, Tex. |

Assassination in Latin America |

|

James R. Soukup Department of Government University of Texas Austin, Tex. |

Assassination in Japan |

|

Denis Szabo Department of Criminology University of Montreal |

Assassination and Political Violence in Canada |

| Inkeri Auttila | Assassination in Finland |

| Kias Lithner | Assassination in Sweden |

|

Daniel Tretiak Advanced Studies Group Westinghouse Electric Corp. Waltham, Mass. |

Political Assassinations in China, 1600–1968 |

The following also submitted papers or appeared at hearings before the Commission and provided valuable insights that contributed to the Report:

|

Dr. David Abrahamsen Department of Psychiatry Roosevelt Hospital New York, N.Y. |

|

|

Joseph Bensman Department of Sociology City College of New York New York, N.Y. |

Social and Instructional Factors Determining the Level of Assassination |

|

Lynne Iglitzin University of Washington Seattle, Wash. |

Violence and American Democracy |

|

Seymour M. Lipset Carl Sheingold Department of Government and Social Relations Harvard University Cambridge, Mass. |

Values and Political Structure: An Interpretation of the Sources of Extremism and Violence in American Society |

|

Harold L. Nieburg Department of Political Science University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Wis. |

The Political Uses of Assassination |

|

Dr. David A. Rothstein Michael Reese Hospital Chicago, Illinois |

|

|

Richard E. Rubenstein The Adlai Stevenson Institute Chicago, Ill. |

Assassination and the Breakdown of American Politics |

|

Dore Schary National Chairman Anti-Defamation League B’nai B’rith |

|

|

Joyce A. Sween Rae L. Blumberg Department of Sociology Northwestern University |

Reactions to the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. |

|

Stanford Research Institute Henry Alberts |

A Study of Game Theory and Probability Models as Employed in the Prediction and Prevention of Assassination |

|

Edward A. Zeigenhagen Department of Political Science Wayne State University Detroit, Mich. |

Systematic Constraints and Political Assassination |

|

Roy Nagle Buffalo, N.Y. |

Assassination of President McKinley |

The original version of each of the foregoing papers is contained in the files of the Commission, as are the transcripts of the testimony.

One final word of appreciation: with almost no exceptions, the consultants to this Task Force were very generous with their time and professional abilities. Again with almost no exceptions, the amount of work each of the consultants contributed to this Task Force far exceeded the compensation received. In addition, both the Advanced Studies Group of Westinghouse Electric Corporation and the Stanford Research Institute generously donated their services. This Task Force received whole-hearted support from those whose help it sought. Nothing could have been accomplished without that support.

Special thanks is owed Robert C. Herr, who helped direct the work of the Task Force from its inception, and our research assistants, Robert Nurick and Linda Stone, who contributed not only notable ability, but continuing good cheer, notwithstanding the severe pressures of time and performance under which the Task Force operated. Our sincere appreciation is also extended to Victoria Clinton, the secretary of the Task Force, who maintained all its records in addition to assuming the main burden of its clerical work; she cheerfully worked nights and weekends to complete her many tasks.

We appreciate the diligent, painstaking, and patient work of Mr. Anthony F. Abell, who established the overall style for this volume and prepared the manuscript for publication.

The greatest debt of all is owed to Katherine Kirkham, Mary Lois Levy, and Nan Crotty, the wives of the codirectors. Each of us on very short notice left our wives and small children in other parts of the country to come to Washington, D.C., for the Commission. None of us could or would have imposed that hardship upon our wives without their loyal and enthusiastic support for the work we undertook.

J.F.K.

S.G.L.

W.J.C.

Introduction

A. Summary

The National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence was established by President Lyndon Johnson immediately after the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy. Senator Kennedy’s assassination occurred within months of that of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and both followed by less than five years the assassination of President John Kennedy.

The Commission divided its staff into various Task Force groups. This Task Force was to investigate and respond to the questions and issues raised by the phenomenon of assassination and the related phenomenon of political violence. It sought among other things, to shed light on the patterns, if any, that exist in assassination and other acts of political violence; the relationship between assassinations and other forms of political violence; the social and political consequences of assassination; the relative incidence of assassinations and other acts of political violence in the United States vis-a-vis other nations; and the environmental factors that encourage groups or individuals to attack political leaders. This report presents and assesses the evidence available on each of these aspects of political assassinations.[1]

Assassinations have occurred throughout the history of the United States and have been employed on occasion to achieve political and ideological goals, although such use has been limited almost entirely to the Reconstruction period in the South.

The number of assassinations and acts of general political violence in the United States is high, compared with other nations, particularly when with more politically stable and economically developed countries. However, despite the assassinations that have taken place during the 1960’s, physical attacks against politically prominent individuals do not appear to be increasing.

The risk of assassination is considerably greater for elective as opposed to appointed public officials in spite of the fact appointed officials may wield greater power. Also, the risk of assassination is directly proportional to the size of constituency of the officeholder. The presidency is the most striking example. In relation to the number of officeholders, the position of President has been the object of by far the greatest proportion of assassination attempts.

Truly “political” assassinations, that is assassinations that are part of a rational scheme to transfer political power from one group to another or to achieve specific policy objectives, are rare in the United States. Assassinations did occur in the Reconstruction period in the South combined with terrorist activities employed in an effort to reinpose white supremacy after the Civil War. But most assassinations in the United States have been the products of individual passion or derangement.

As an example, each of the persons who attempted, either successfully or unsuccessfully, to assassinate Presidents of the United States, with the possible exception of the so-called Puerto Rican nationalists who attacked President Truman, evidenced serious mental illness. None of them were chosen representatives of political movements, although most claimed allegiance to broader political groups and cited political reasons for their act. Each assassin seemed to be acting out some inner pathological need. Despite this, the public, in reaction to the assassinations, has sometimes attempted to tie the assassins to political movements or conspiracies.

The presidential assassinshave a number of characteristics in common. Still, we are as yet unable to comprehend the individual and social forces at work sufficiently to be able to identify potential assassins in advance of their attacks. Characteristics common to assassins are shared by a large number of citizens. It is, however, both impossible at this point and probably undesirable in a democratic political system to attempt to identify and isolate potential assassins on any broad scale based on present knowledge.

As a result, prevention of assassinations must remain fundamentally a problem of physical protection. The Secret Service has the principal responsibility for protecting the President and is engaged in a continuing program to evaluate and upgrade its capabilities and to reduce the exposure of the President to risk.

Assuming the assassin to be mentally ill, there remains the question what factors tend to channel such mental illness into an assassination event. Our studies show that assassination correlates highly with general political turmoil.

Political turmoil and violence have characterized the United States throughout its history. Levels of political violence appear to crest during periods of accelerated social change. Agrarian reform abolitionism, the Reconstruction era, the fight to organize labor, and the periodic recrudescence of American nativism in its various forms were each accompanied by high levels of political violence. The 1960’s have witnessed a level of violence and political turmoil comparable to other high points of violence in the nation’s history.

Also, specific cultural and social factors in the United States may support political violence, including assassinations. Recent years have seen a number of movements that justify violence as a legitimate tactic in seeking political ends. There has been frequent use of rhetoric villifying institutions and individuals. Such rhetoric is frequently a precondition for physical assaults directed against politically prominent individuals. In addition, some segments of the population view our democratic government as ineffectual in meeting the needs of its people.

The likelihood of assassination should decrease as the level of political unrest within the country diminishes.

Neither panic nor complacency is an appropriate response to this Report. We should not surround our elected representatives with guards or otherwise risk isolating political leaders from their contact with the people. Our data suggest that isolated acts of assassination, unconnected with systematic terrorism, rarely bring fundamental change to a nation and have not had such impact in the United States, with the possible exception of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the other hand, our data suggest that isolation of political representatives from the people may have a long-range corrosive effect upon the perceived legitimacy of democratic institutions.

Nor should we seek specific legislation purporting to respond directly to the problem of assassination alone. The most effective defense against assassination in a society that seeks to preserve freedom of the individual is an overwhelming consensus that the government is legitimate and responsive to the people. A government supported by such a consensus will have the political strength and purpose to defend itself firmly and effectively at all levels against those who reject the ideals of democracy.

Thus, we report that the continuing urgent search for strategies to cope with fundamental causes of present disaffection in the United States, such as racial inequality, mounting crime, and the questioned use of military force in our foreign affairs, is of direct relevance to the overall problem of assassination. Such disaffection weakens the consensus upon which the strength of the government is based. We have not found a specific remedy for assassination and political violence in a democracy apart from the perceived legitimacy of the government and its leaders.

B. Organization

The introductory section of this report begins by discussing definitional problems associated with the study of assassination. It presents five categories of assassination, distinguishing between, for example, a palace coup, and the attack of an individual acting out private pathological needs. This part of the report helps to establish a framework in which to evaluate the American experience.

The section also describes preconditions, or factors conducive to assassinations, based on the patterns found in the historical and comparative studies of assassination in a variety of different countries. While, strictly speaking, the precondition to an assassination is a man with a weapon and sufficient motivation to murder a political leader, this section attempts to identify broader, more basic factors that shape an environment conducive to assassination.

The introductory section concludes with an overview of the impact of assassinations upon governmental policies and political institutions, again based upon historical and comparative studies. The conditions necessary for an assassination to provoke fundamental change are reviewed and the likelihood of these occurring at the time of a specific assassination is discussed.[2]

The remainder of the report is divided into four chapters. Chapter 1 describes all attempts on the lives of officeholders in the United States. The perspective is historical and the time period covered is from the inception of the Nation to the present. The offices analyzed are President, US Senator, US Congressman, Governor, State Legislator, Judge, Mayor, and other local offices...

Chapter 2 analyzes in greater detail presidential assassinations, describing the events connected with each assassination and evaluating, to the extent possible, the motives and emotional stability of the assassins. The chapter reports on public reaction to the assassination and the impact that presidential assassinations have had on political institutions and policy. The symbolic attraction of the office of President for assassins is explored, and several general recommendations are put forward to direct attention to the limits of the office, as well as the alternative points of decisionmaking avilable within the political system. The problems of physical protection of the President are dealt with from the perspective of the Secret Service, the agency charged with this task.

Chapter 3 employs cross-cultural comparative data to compare the American experience with assassinations in other nations. The data show that the United States ranks high in political assassinations. The analysis also describes the relationship between assassination and other forms of political violence. These data, in addition to providing a perspective on assassinations in the United States, contribute a framework and basepoint from which to begin a more intensive exploration of the historical studies of individual nations and regions contained in the supplement to this report.

While Chapter 3 employs quantitative data to discover patterns of political violence among nations, Chapter 4 explores the cultural factors that underlie the high incidence of assassinations and other politically violent acts in the United States. The chapter presents historical overviews of political violence, including both an historical review of the major political movements and groups associated with violence and an analysis of trends in politically violent behavior obtained from a sampling of newspaper accounts over a 150-year period. With this as background, the contemporary levels of violence in the United States are analyzed in several ways. From an original survey of data, the demographic characteristics of those persons in our society who express support for political violence are described. Then, several examples of the rhetoric of violence, drawn from the more extensive materials contained within the appendix to this report, are put forward. Such rhetoric is often a precursor of attacks directed against individuals. The chapter, and the volume, ends with a personalized exploration of two contemporary groups which pose typical problems for those concerned with political violence.

Conceptual and Structural Analysis of Assassination

A. Problems of Definition

Although this is a report about assassination, we do not undertake to define precisely what is meant by an “assassination/’ nor do we limit consideration in this Report to a particular consistent definition of “assassination.” There are at least three separate elements woven into the concept of “assassination” which identify it as a particular kind of murder: (1) a target that is a prominent political figure; (2) a political motive for the killing; (3) the potential political impact of the death or escape from death, as the case may be.

Most murders that would be called “assassinations” contain in greater or lesser degree all three elements, as for example, the killing of a head of state by an agent of a rival political party for the purpose of changing the regime. All three elements, however, do not necessarily coexist. A murder which contains any one of the foregoing three elements should properly be considered in any investigation of the phenomenon of assassination. For example, during the 1920’s in Germany, there were a great number of politically motivated killings of persons whose political stature was trivial, but these political killings and assaults had great significance. The terrorism during the Reconstruction era in the South often had nonpolitical figures as its object. In recent years, civil rights workers—not political figures by ordinary definition—have likewise been murdered or assaulted for political motives. Such acts of political terrorism are assassinations in some senses; they should be and are treated as such in this report.

At the other extreme, the head of state or a crucial political figure could be murdered by his estranged wife or simply by a burglar with no political motivation. Nonetheless, the impact upon the political system involved could be profound. Again, in some senses, these would be assassinations and are treated as such in this report.

In assessing the impact of assassination or the level of assassination in a given country, it could be argued that the relevant inquiry becomes, “What factors within a country produce high or low impact upon the removal of a political figure, whether by assassination or not.” As Carl Leiden[3] points out, the natural death of a political leader under certain circumstances can have a far more profoundly disruptive political effect than would the assassination of a political leader under other circumstances.

Also, how does one categorize attempts by mentally disturbed persons, such as the typical attacker of a President of the United States? A distinguished psychiatrist and contributer to the Commission, Dr. Lawrence Z. Freedman, has suggested that in some senses, with the possible exception of the attack upon President Truman, there have been no political assassination attempts directed at the President of the United States. The attacks are viewed as products of mental illness with no direct political content. This view is certainly arguable.

Our approach has been to avoid the definitional swamp by simply going around it, using routes dictated by common sense and practicality. In Chapter 1, we have treated all attacks against officeholders in the United States as worthy of our attention, although in most instances the attacks did not have a primary political motivation. In Chapter 2, we treat all attempts upon the lives of Presidents or of presidential candidates as assassinations.

In Chapter 3, our cross-national comparative study of assassination, we draw upon the work of two groups, one headed by Prof. Ivo Feierabend at San Diego State College, and the other headed by Professor Carl Leiden at the University of Texas.

Each group was in a position to make a valuable contribution to the study of assassination despite severe time constraints. Each had already begun gathering relevant data prior to the formation of the Commission. Each group had been working independently. In presenting their materials we adopted the definition of assassination used by each of these groups, although the definitions are not entirely the same. We did so because: (1) no reasonable alternative was feasible or desirable in terms of coordinating and reworking data which had already been gathered by the two groups, and which spoke of different times periods and (2) definitional consistency is irrelevant. Each group made cross-national comparisons only in terms of its own data: that is, all comparisons are based on a consistent definition.

Nor need the definitions used in Chapter 3 be consistent with those used in Chapters 1 and 2. The validity of comparisons of relative incidence of assassination and political violence is unaffected by the fact that the data banks used for comparative purposes may or may not have included all the Presidents of the United States or all the officeholders listed in Chapters 1 and 2 as “assassinations.”

In Chapter 4, we have treated low-level political violence as a proper subject for this Report—i.e., violence for political purposes, but not necessarily directed toward political figures. Again, whether the deliberate murder of a Pinkerton guard or a union leader in an earlier time would be considered a “true” assassination is a meaningless question. As we will demonstrate, low-level violence keys into high-level violence. Low-level violence has political implications and impact. Such conduct must be treated in any discussion of political assassination.

B. Categories of Assassination[4]

Acts of assassination can occur in different social and political contexts and may be committed for different reasons. While avoiding the problem of precise definition of assassination as such, it is useful to describe the various categories of assassination and examine the experience of the United States and other regions in the world in light of these categories.

1. The first category we can identify is assassination by one political elite to replace another without effecting any substantial systemic or ideological change. The purpose of such an assassination is simply to change the identity of the top man and the ruling clique.

This kind of assassination appears in the Middle East. Palace revolutions, or coups in Latin America would also come under this heading. Coups in Latin America, however, have not always ended in assassination. The object of the coup has usually relinquished his position and those taking power have been content to let him live.

This type has been successful in countries where the government has little de facto impact upon the vast body of the citizens outside the capital city. As long as governments can come and go with little impact or participation by peon or fellahin, as the case may be, palace revolutions appear to be a practical way of gaining power. This type of assassination has not appeared in the United States.

2. A second category is assassination for the purpose of terrorizing and destroying the legitimacy of the ruling elite in order to effect substantial systemic or ideological change.

Such assassination may be directed against high government officials or against mid-level officials to undermine the effectiveness of the central government at the local or provincial level. When such terror is directed toward a chief of state, the assassin may accomplish part of his goal even though the attempt is unsuccessful. For example, the members of the group which set out to assassinate the Czar in the 1880’s realized that they had no realistic chance of short-term success in changing the basic political structure of Czarist Russia. They pointed out, however, that if they forced the Czars to retreat into their palaces or surround themselves with guards, the symbolic separation of the leaders from their people would, in the long run, undermine the legitimacy of the Czarist government.

Our studies show that this kind of assassination is effective in achieving the long-range goals sought, although not so in advancing the short-term goals or careers of the terrorists themselves. Our studies show that, at least in modern history (post-1850), it cannot be said that in the long run any terrorist group was unsuccessful, except in those countries such as Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany where the ruling elite was willing to use massive counter-terror to suppress potentially terroristic groups. Once a terrorist group is well established, the only effective response is either counterterror or agreement to the basic demands of the terrorists—demands which may or may not be compatible with a democratic society. The Nazis, for example, rose to power on a wave of terrorism.

The best defense against terrorism is a government which has the broad popular support necessary to control terrorist activities through normal channels of law enforcement without resorting to counterterror. Terrorists often correctly perceive that their greatest enemy is the moderate who attempts to remedy whatever perceived injustices form the basis for terrorist strength. It is often these moderates who are the targets of assassination.

For example, Premier Stolypin of Russia, whose energy and force might have made the Duma a practical instrument of constitutional monarchy, fell to an assassin in 1911. Archduke Ferdinand, whose death triggered World War I, advocated federalism and limited autonomy for Serbian nationals within the Austrian Empire. The representatives of Serbian nationalism who killed him apparently feared that this moderate policy might undermine the support upon which they counted.

It should be pointed out that even the strategy of remedying the perceived injustices from which the terrorists gain their strength may not work or may be impractical, because that strategy may be consistent with the basic goals of the central government.

An example is the British presence in both Cyprus and Palestine. It was the British presence itself that was the perceived injustice. In both instances, terrorism was effective in spite of all counter-strategies. As can be seen, terrorism is particularly effective when the government is viewed by a substantial portion of the local population as a foreign conqueror or otherwise illegitimate.

This type of assassination terrorism appeared in the South directly after the Civil War. The imposed ruling class was viewed as illegitimate by a substantial portion of the population. Assassination of Northern Republican officeholders, combined with systematic terrorism practiced on Southerners sympathetic to the then “foreign elite,” eventually forced Northern capitulation. The so-called “Southern way of life” was reestablished, and lasted virtually unchallenged until the 195O’s.

Even where the government is neither foreign nor otherwise illegitmate, if terrorism has established itself, it may become so institutionalized and professionalized as a way of life that no concession is sufficient. A concession may please one group but offend another. This is apparently what happened in the case of the IMRO, or Black Hand, in the Balkans. Thus, it is important that potential terrorism be recognized and counteracted at an early stage.

3. A third category is assassination by the government in power to surpress political challenge.

This strategy, including mass counterterror, has appeared in Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany. A recent example was the assassination of the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood by the Egyptian Government. Such strategy is not necessarily ideologically based. Machiavelli advised this strategy for the prince who has just come to power—to kill relatives of the previous prince and other potential challengers with promptness in order to make his power secure. Such a strategy is an indication and confession of weakness by the central government. This type of assassination has not occurred in the United States.

4. A fourth category is assassination to propagandize a political or ideological point of view. This is the so-called “propaganda of the deed,” popular with anarchists at the turn of the century.

Its purpose is to dramatize and publicize perceived injustice. Some of the assassins of Presidents of the United States may marginally fall within this category, as well as within the fifth category.

The success of such strategies cannot easily be measured, for the assassin does not purport directly to advance his ideaology except through publicity. A cause-and-effect relationship cannot be unravelled. For example, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand may fall in part within this category-to publicize Serbian national aspirations. The effect, we can speculate, was to create upheavals far beyond those anticipated, and still there is no Serbian national state-although Yugoslavia perhaps comes closer than Austria. The speculation remains whether the assassins and the group they represented

would prefer Yugoslavia today to the rule of the Austrian Empire prior to World War I.

5. The fifth and last category is assassination unconnected with rational political goals which satisfies only the pathological needs of the mentally disturbed attacker. This represents the typical attacker of Presidents of the United States. Whether such assassinations achieve the goal of the assassin is a matter of psychiatric speculation. To the extent that such assassins seek attention, publicity, and importance, they consistently have achieved their goals in the United States.

C. Preconditions for Assassination’[5]

Cross-national comparative studies demonstrate that other forms of political violence correlate highly with and may be preconditions to assassination. That is, political turmoil itself may spawn assassination without regard to distinctions between types of turmoil.

We believe, however, that our studies of assassination in specific regions and countries throughout the world enable us to identify more precisely certain preconditions for assassination.

An analysis of the preconditions of assassination cannot ignore the issue of the kind of government towards which the assassination is directed. The study of assassination and terrorism in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries demonstrates that the preconditions for assassination under a democracy differ from preconditions under oppressive foreign or autocratic rule, where political expression is not allowed. Where there is oppressive rule, comparative studies suggest three antecedents to assassination: (1) the existence of a political party with an ideology and technique of direct action; (2) perception of oppression; and (3) presence of activists, i.e., persons willing to respond with violence to the conditions of oppression.

In a democracy, however, where physical oppression is absent, its equivalent must be created through (1) a weakening of shared democratic values, or a crisis in which the democratic institutions are incapable of taking effective remedial action; and (2) a pre-assassination process of defamation and vilification of democratic politicians and institutions. The remaining preconditions are also shared with the oppressive rule situation—(3) the existence of a party or groups of persons with an ideology and tactics of direct violence, and (4) the presence of persons with propensities for violence once the antecedents are present.

A number of the preconditions for assassination are latent in the United States. Some groups may perceive the government as oppressive, in which case the model describing oppressive rule is applicable. It is, however, a reverse sentimentalism to distort the overall picture of political conditions in the United States by dwelling on its admitted imperfections. The United States is a remarkably free country. Most of its citizens enjoy perhaps more real freedom, including the freedom from hunger and other material deprivations, than any other nation. Thus, it is the second model, preconditions for assassination in a democracy, which is of particular interest to us.

Specifically, the rhetoric of vilification of political leaders and the advocacy of violence may have a more profound effect than we have realized. The fact that our most tragic assassinations have been at the hands of persons who were mentally deranged, or not part of any political conspiracy, does not weaken the point. As Professor Feliks Gross points out, by way of example:

Before the assassination of President Gabriel Narutowicz in 1922 in Poland, in a pre-assassination stage, a vituperous defamation campaign was launched against him by the parties of the right. The assassination was an isolated, political act of killing, not a result of a terroristic tactic. The assassin, Eligious Niewiadomski, believed that he’had performed a heroic act and a patriotic duty. There was neither conspiracy nor organized terroristic party. But in the climate of vilification, once the political actor was “morally” branded, eliminated, and destroyed, psychological restraints and controls of a potential assassin were weakened or even removed, and in his view assassination was justified (Supplement, section A).

Professor Gross is not alone with his concern for the impact of such rhetoric. Dan Watts, editor of The Liberator magazine, a Negro, and an early advocate of black nationalism, made the same point in an interview with a consultant for this Task Force, that there should be a deescalation of violent talk before it leads to violent action (see Appendix D). On the other hand, a stabilizing strength peculiar to the United States is its unique capacity to absorb and adopt the rhetoric and symbols of radical challenge. To this extent, one can agree with and rejoice in one of the basic theses of Herbert Marcuse that the United States has a tremendous capacity to absorb and thus to emasculate radical challenges. One early exponent of the “hippie” movement complained that the movement was not a success in challenging basic American values because trying to change the United States was like “tilting with a marshmallow; you end up getting smothered.”[6] In effect, the movement has been in large part absorbed through diffusion of its symbols into the very establishment which the hippies challenged. This process has a two-fold benefit. In the process of absorbing the destructive radical challenge, the establishment in the United States also experiences renewal and change, not by a destruction of fundamental values, but by an evolutionary awareness and adaptation to the challenging point of view. It is this capacity for absorption and the good-humored refusal of mainstream America to allow itself to be teased into overreaction by irrelevant symbols—well publicized, short-term exceptions to the contrary notwithstanding-which contributes to America’s great capacity for keeping its basic democratic values intact while making the necessary adjustments and responses to continuing change.

D. The Impact of Assassinations on Government Institutions and Policy

It takes a congruence of unusual circumstances for assassinations to achieve fundamental long-run changes within a political system. An assassination of whatever category is not likely in itself to cause any basic alterations in institutional forms or policy.[7] Under a combination of unusual circumstances, however, the removal of a key figure-for example, a Lincoln or Franklin Roosevelt (unsuccessfully attacked just before he took office) in the United States, an Abdullah in Jordan—can have unanticipated and profound implications for the course of the society. The convergence of forces necessary to create high-impact assassinations occurs rather infrequently, however.

Carl Leiden[8]distinguishes between the implications of the assassination act for the survival of the system as against the considerably less consequential difficulties it might create for a particular ruling elite or party. He argues that only in a few very specific cases do assassinations have profound implications for the total political system.

An assassination can have a high impact when (a) the system is highly centralized, (b) the political support of the victim is highly personal, (c) the “replaceability” of the victim is low, (d) the system is in crisis and/or in a period of rapid political and social change, and (e) if the death of the victim involves the system in confrontation with other powers. (Supplement, section F)

Applying the foregoing criteria to the United States, we believe that there is little likelihood of an assassination in the United States having a fundamentally destructive impact. Our leaders are either constrained or supported, to the extent that they are either strong or weak, by the institutional framework within which they must operate. Although the federal government has great power, that power is divided among three branches, and the power to control individuals is also shared to a significant degree by the State and local governing bodies. Thus, our government is probably not “highly centralized,” that is, our government is not a single hierarchy of power which would be possible for one man to control.

Support of political figures in the United States may result from a charismatic inspiration of personal loyalty among supporters, for example, the two Roosevelts, Bryan, and Lincoln. But such personal support is effectively constrained by our institutions of government. It is impossible for political leaders in the United States to operate outside of institutional forms that set clear restraint on the powers of the office and the eligibility and tenure of its occupants. The political system of the United States also permits many competing centers of power as well as procedures for opposing and replacing those in office.

“Replaceability” of the victim of an assassination is, of course, a concern in the United States, in the sense that no man is a duplicate of another. Each President brings to the office unique qualities which may effect the way he handles a “crisis,” “a period of rapid political or social change,” or a “confrontation with other powers.” Nevertheless, the United States does have an ordered replacement system for its Presidents that has proved successful. The institution of the presidency, with all its powers, limitations, and resources, remains even as one man leaves the office and another succeeds to it. This will continue to be true so long as the United States remains a country governed by law, not by men.

We can take comfort from Professor Leiden’s summary statement that “assassination ... as a deliberate instrument of policy is a highly uncertain, risky adventure with little probability that systemic or other far-reaching changes will be brought about ”[9]

Chapter 1: Deadly Attacks Upon Public Officeholders in the United States

A. Introduction[10]

During all stages of our Nation’s history, violence has been one response offered to many of the controversial issues confronting our society. The establishment of independence, the relationship of settlers with the American Indian, the slavery and secession questions, and the trade union and civil rights movements are prime examples. Included in this history of violence are deadly attacks on persons holding public office. Chapter 1 is addressed to this particular kind of political violence.

It is important to state clearly at the outset the definition of assassination used in this chapter. We consider “assassinations” all deadly attacks upon public office holders in the United States by any person for any reason. Included is violence (in the form of direct physical assault, use of firearms, or conspiracies, the aim of which is death or injury) directed at persons both holding or actively aspiring to such office. The offices considered cover a wide range: Presidents, cabinet members, governors, senators, congressmen, mayors, state legislators, judges, tax collectors, state and district attorneys, etc. Not included are politically prominent leaders or workers for social causes or political movements and organizations who did not hold public office, were not actively aspiring to public office, or were not former officeholders.

In specific terms, this section reviews all reported deadly attacks upon public officeholders or aspirants to public office without regard for motive for the attack—whether “personal” or “political”—from revenue collectors to Presidents. But this section does not consider attacks upon persons such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, or George Lincoln Rockwell. By including all officeholders who have been the victims of attack, we gain confidence in the validity of our conclusions as to the nature and scope of the problem of deadly political violence in the United States. Virtually none of the deadly attacks against officeholders had a dominant rational political purpose; but most were in some way related to politics. Thus, the soundest approach is to include all such attacks in our investigation; no subjective judgements had to be made about whether the dominant motive for the attack was political, and the entire scope of such violence is before us. In excluding attacks upon all non-officeholders, we again avoid the problem of subjective judgment. Further, we avoid severe historical bias, because the names of the “politically prominent” of a given era tend to fade more rapidly from the pages of history than do the names of officeholders.

Table 1 lists all eighty-one of the recorded assassinations or attempted assassinations in chronological order. Working with this limited but useful definition of assassination, two conclusions can be drawn from the data in Table 1. First, the more powerful and prestigious the office, the greater the likelihood of assassination. Second, there is much greater likelihood that the occupant of or aspirant to an elected public office will be the victim of an assassination than will the occupant of an appointed position, even though the position may be a powerful one, such as Secretary of State, Justice of the Supreme Court, or Attorney General.

The relationships between the importance of the office and the likelihood of assassination are dramatically demonstrated by Table 2. This table compares the proportion of successful or attempted assassinations in four offices which differ significantly in degree of power or prestige.

Despite the crudeness of the estimates upon which the figures inTable 2 are based, the differences among the four categories are still sufficiently large that the relationship between importance or prestige of position and likelihood of assassination is demonstrated. One out of four Presidents has been a target of assassination, compared to approximately one out of every one hundred and sixty-six governors, one out of one hundred and forty-two Senators, and one out of every one thousand congressmen.[11]

We can suggest that the correlation between importance of elected office and likelihood of assassination is affected by the fact that the importance of the office and the size of the constituency are directly related. The President’s constituency is much larger than that of any other elected office. Similarly, a senator’s or a govenor’s constituency is greater than that of any congressman. Of the eight senators and eight governors who have been assassination targets, all but one were attacked by members of their own constituency.

The absence of assassination attempts on the vice president may also be consistent with this observation; the office of vice president has no elective independence from the presidency, and, in effect, has no constituency for purposes of this analysis. In any event, the office is sufficiently anomalous that lack of assassination attempts directed at the vice president does not necessarily invalidate the postulated relationship between assassination and size of constituency.

The second point is that persons in elected positions are more likely to be assassinated than are occupants of appointed offices. Of approximately four hundred and fifty cabinet members, and of approximately one hundred and two Supreme Court Justices, only one in each category has been the target of an assassin.

With the exception of attacks upon Republicans in the South during the Reconstruction era, only a very small portion of the deadly attacks against officeholders was rationally calculated to advance political aims of the assassin. With the possible exception of the attack upon President Truman by two self-avowed Puerto Rican nationalists, none of the presidential

assassinations or assassination attempts were made under the aegis of any organized political group or to advance any rational strategy for political change. Still, the unbalanced minds of the presidential assassins focused themselves on high political officeholders rather than nonpolitical targets, and the question of why those acts became political still remains.

Similarly, the attacks on other officeholders were related to politics without being “conspiratorial” or “political” in the sense of seeking power. Senator Charles Sumner, the antislavery senator from Massachusetts, was severely beaten on the floor of the Congress by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina three days after Sumner had made a strong speech denouncing slavery. Several other public officials were attacked in quarrels over political issues. A number of officeholders were attacked by constituents who harbored a personal grudge over political treatment they thought they had received.

Perhaps as many as eleven public officials were victims of assassination attempts by elements of organized crime. These were mostly lower-level officials who were either involved with the criminals or whose activities represented a threat to organized crime. We may speculate that such attacks were well planned and “political” in the sense of seeking to control legislative or executive conduct vis-a-vis the attackers. These may be the only examples that are comparable to the classic form of “assassination” in other nations, i.e., for direct political payoff.

Of all the assassinations and assassination attempts against officeholders in U.S. history, perhaps only one, excepting those related to organized crime, fits the classic picture of an assassination for a rational political purpose—that of Governor William Goebel of Kentucky in 1900. Goebel narrowly won a hotly contested three-way fight for the governorship between Populist Democrats (Goebel’s party), Conservative Democrats, and the incumbent Republicans. Three men associated with the Republican party were convicted of conspiracy to assassinate the Governor.