Jamie Gehring

I Grew Up Next To The Unabomber. I Felt Such Anger Toward Him — So Why Am I Grieving His Death?

"I thought back to the times I was home alone, forced to hide in a coat closet while my strange neighbor knocked on my door and peered through the windows."

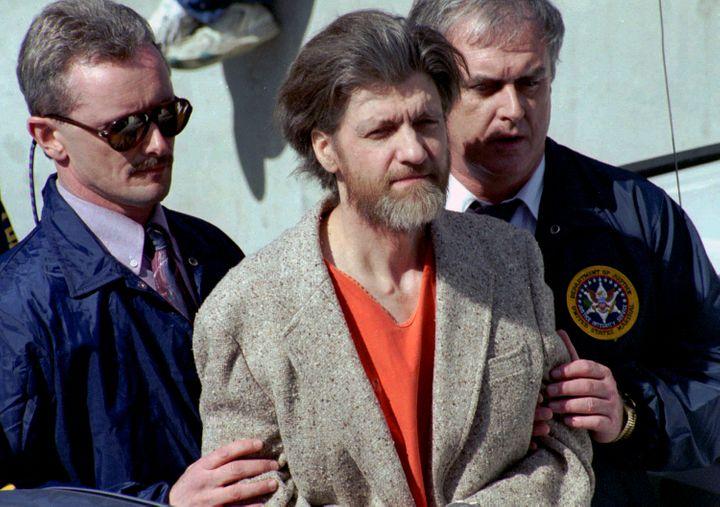

JOHN YOUNGBEAR/ASSOCIATED PRESS

“Ted just died,” I told my husband in a hushed voice.

As we stood in the shadows of the Duke of York’s Theatre, where we were meant to see the premiere of “The Pillowman,” I felt like a prisoner to my complicated emotions in this land foreign to me. Everything hit me at once while crowds of people passed by, laughing, drinking and taking in the vibrant nightlife of London.

“Are you OK?” he asked.

“I think so. I knew this was coming. It’s just hard to put words to,” I replied as he took my hand.

I was only 16 when my neighbor, Theodore J. Kaczynski, was arrested. Better known to my family as Ted or Teddy, and then “The Unabomber,” this man had held our nation captive with his killing. Universities, airlines, storefronts, scientists ― his targets were so scattered it felt as though these attacks could happen to anyone. He reveled in the control he held, and he treated it much like a game.

Though I found out as a teenager that the hermit next door was planting and sending bombs for 17 years while seemingly living a peaceful existence beside us, it took me more than 20 years ― and writing a book about the experience ― to fully process it. To this day, it is still hard to reconcile the serial killer with the man bringing me gifts as a child.

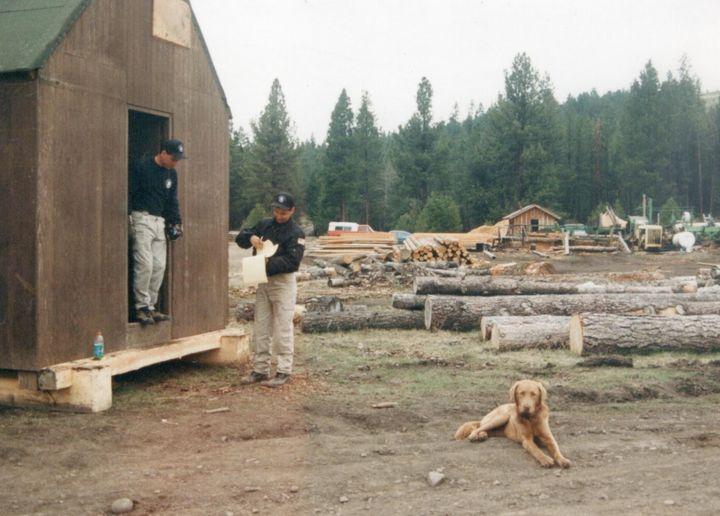

The former professor, who lived next to my family from 1971 to 1996, killed three and injured more than 20 innocent people in the name of revenge. He sat in his rural 10-by-12 cabin with no modern conveniences and wrote of murder in his journals, where he described his victims as experiments.

In his journals he outlined his ideas, which would later be presented in a manifesto, and documented bomb construction and experimentation in our shared woods. His anger was fueled not only by isolation during the cold Montana winters but also his vehement hatred of modern technology.

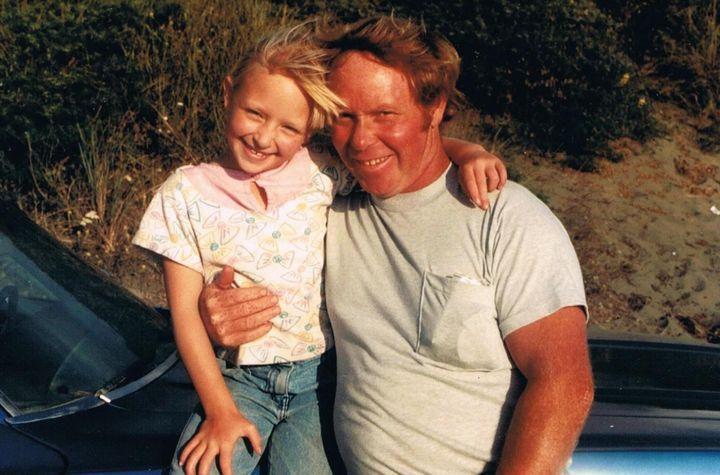

COURTESY OF JAMIE GEHRING

Two decades after Ted explored the pristine forests in Lincoln, Montana, and then planned and plotted, I worked to unearth the full range and rage of Kaczynski as I interviewed the only man that was ever truly close to Ted, his brother David Kaczynski; the FBI agents that ended the Unabomber’s reign of terror, including FBI agent Max Noel; and many others who knew Ted during his bombing campaign. With this insight, paired with my own memories of a childhood sharing a vast backyard, I saw the murderer and I saw the man who became a killer. I cried for his victims ― children left without a father, mothers without a son, wives without a husband. I thought of the people who were targeted and left to wonder Why? and Who next? until the domestic terrorist was arrested in 1996 and sentenced to life in prison in 1998.

The compassion I felt for the people who suffered at the hands of Kaczynski always outweighed my childhood fondness for the killer next door. But there was still a part of me ― the child on the side of the mountain with the unkempt hermit ― that held a small amount of clemency for the longtime neighbor.

This theme came to the forefront once again just a couple of years prior to learning of Ted’s death.

During the past few years, I corresponded with Ted in an effort to better understand his criminal mind and his motives, while attempting to reclaim a part of my own childhood. I wrote to him about my memories of him, my father’s part in the UNABOM investigation and arrest, and even my father’s passing. I also looked for his thoughts on topics such as social media, school shootings and even rising depression and anxiety rates (which is a topic frequently researched and described in Kaczynski’s writings).

Ted’s response to my outreach reaffirmed that my neighbor hadn’t changed during his years in prison. In fact, I felt that the two-sided letter I received penned in the curly handwriting that I had come to recognize told so much about the man that I had to include it in my own book.

COURTESY OF BUTCH GEHRING

The front of the letter was a nod to our shared time together, surface responses to my questions and advice that was far from what I had expected.

The back of the letter was a stream-of-consciousness about freedom written from Ted’s Supermax prison cell.

But it would be dishonest, albeit naive, to say I wasn’t hoping the man would offer an apology for the pain he had caused. Even though I knew the chances of that were extremely low, I continued to write to him.

As I was preparing to address a letter I wrote to Ted in December of 2021, I typed the convicted killer’s register number into the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ search engine. Expecting the Supermax to appear, just as it had only a couple of months prior, I took pause as I read the bold typeface scrolled across my screen: LOCATED AT: BUTNER FMC.

The Unabomber, the man living off the land and waging his own war of domestic terror, was now in a federal security medical center, no longer held in the “Alcatraz of the Rockies.”

After multiple conversations with sources close to Ted, I found that the aging man was fighting cancer. The move to Butner was made out of necessity, and I kept this news private. I knew that Ted had started treatment for an aggressive cancer, so it didn’t come as a shock when I located a letter that he had written that stated that his condition was terminal and he had only two years to live.

Still, I never could have imagined that the news of the death of the serial killer next door would have come while I was on the streets of London, sandwiched between an international true crime event and an evening in the West End that was meant to examine the role of artistry in society.

On that muggy evening in the U.K., the news alerts overtook my phone. Then I spotted the headline, “Kaczynski Is Said to Have Died by Suicide in Prison.” The article stated that he was thought to have taken his own life, early in the morning on June 10, “according to three people familiar with the situation.” As I write these words, an autopsy still hasn’t been completed and an official cause of death cannot be announced until that is final.

COURTESY OF JAMIE GEHRING

As I focused on mental health, suicide and cancer, images of Kaczynski flooded my thoughts. In my mind, he resembled the young Berkeley professor rather than the austere bomber in the orange jumpsuit. Remembering the early years with Ted was so visceral that I could smell the mountains we shared, see the vibrant sunflowers in the afternoon sun and feel the hand-painted rocks that Ted had brought me as gifts.

This slideshow of memories was rapidly replaced with a barrage of headlines. Seeing “Kaczynski” and “suicide” together was haunting, as I had written the two words together multiple times while drafting my manuscript. Years prior, I had discovered that Ted’s father, lovingly referred to as “Turk,” had died by suicide. After Turk discovered he had cancer, the husband and father ended his life.

But the theme of suicide didn’t end here. More than 25 years before Ted’s death, the bomber had attempted to end his life while he awaited trial in Sacramento, California.

As thoughts of cancer and suicide circled my mind, I felt grief overtaking me.

This emotion was uncomfortable, and I reminded myself that my childhood “monster” was gone.

This man had murdered innocent people and caused so much heartache. I thought back to the times I was home alone, forced to hide in a coat closet while my strange neighbor knocked on my door and peered through the windows. I remembered the writings and interviews I had completed that revealed the danger that had been lurking in my backyard. Traps that could have killed me and my family were discovered. One of our dogs was lethally poisoned with strychnine. And most terrifyingly, my little sister, only a toddler at the time, was in Kaczynski’s rifle scope as he considered killing close to home. My stepmother’s recounting of the day she read these words in Ted’s journals still haunts me: “It would be easy to take the little bitch out [my sister]. But then the big bitch [my stepmom] could get away. Or if I shoot the big bitch, then the little bitch would be left on the hill.”

The unearthing of the danger we unknowingly faced as his neighbors for all of those years only fueled my already existing anger toward this murderer. How could I possibly be feeling what I knew to be grief?

You may have heard the saying that “with every loss, you feel all the losses that have come before.”

COURTESY OF BUTCH GEHRING

Ted is inextricably tied to my childhood ― the carefree years of riding horses and my motorcycle, playing in the Blackfoot River while my dad spent the afternoon fishing, and answering the log cabin door for that wild-eyed hermit that just happened to be our neighbor. He’s also directly tied to and responsible for the loss of parts of my childhood innocence and my naive sense of security that was shattered when we learned what he had done.

In addition, Ted’s passing brought to the forefront my own emotion tied to my father’s death. It brought back the grief I felt when my sister passed away unexpectedly at the age of 24. It was a reminder that my own time is limited ― that the cycle of life can be brutal and unrelenting.

There isn’t a person that can outrun or outsmart this part of our human condition, not even the Unabomber — a serial killer obsessed with dismantling technological society.

I do not know where my emotions will go from here. Should we grieve for the death of someone who did unforgivable things? And if we do, what does that say about us? Maybe it simply says I am human ― that loss isn’t simple and neither is trying to understand why people do evil things. Or that sorrow is messy and complicated and can be intimately connected to parts of ourselves we lost or left years ago. One thing does feel certain: Now that Ted is gone, a bit of me ― some version of myself I knew all of those years ago when he was just my neighbor ― has vanished, and I don’t know that I’ll ever get it back.

Jamie Gehring is a Montana native who grew up sharing a backyard with Ted Kaczynski, the man widely known as the Unabomber. She was featured in Netflix’s “Unabomber: In His Own Words,” where she discussed her family’s role in Kaczynski’s capture. She was recently shortlisted for the Best New True Crime Author award by CrimeCon UK, and her narrative nonfiction debut, “Madman in the Woods: Life Next Door to the Unabomber,” has been described as being both universal and deeply personal. Jamie holds a bachelor’s degree in visual communications and spent the first half of her career in finance. She currently lives in Denver with her husband, three children and two cats.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

If you or someone you know needs help, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org for mental health support. Additionally, you can find local mental health and crisis resources at dontcallthepolice.com. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention.