Janet McCracken

Lake Forest College

Ruination and Redemption in Billy Wilder’s Romantic Comedies

In his acceptance speech for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film of 1992, Fernando Trueba stated, “I would like to believe in God in order to thank him. But I just believe in Billy Wilder...so thank you, Mr. Wilder.” To directors, Billy Wilder, who would die in 2002, was alive and well in every sense. When French filmmaker Michel Hazanavicius accepted his Oscar for Best Picture for The Artist (2011), he thanked “Billy Wilder…Billy Wilder, and…Billy Wilder.” Director Stephen Frears, no slouch himself, is currently in post-production of a film about the Hollywood icon, starring Christoph Waltz. Directors get books written about them, and the volumes written about Wilder are too numerous to review, but not often do directors get movies made about them. Wilder, however, was a rare sort: a director’s director, the kind of artist who, long after death, keeps teaching the other directors, and the scholars keep talking. In this company, then, it’s prudent for me to keep my claim modest, demonstrable, and useful. My claim bears some resemblance to what Andrew Sarris once wrote: that the “apparent cynicism” in Billy Wilder “was the only way he could make his raging romanticism palatable’” (McBride, 273). Conversely, Neil Sinyard and Adrian Turner “drew attention to Wilder’s gentler, more romantic side…[challenging] the accusations of cynicism and bad taste” (Armstrong, 2). But that’s the point: Wilder would never sacrifice comedic or romantic force in his films, but neither would he sacrifice tragic or agonistic elements that drove the otherwise happy endings toward existential choice.

Born in Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which, after WWI, was considered a part of Poland (McBride, 11), Billy Wilder was raised amidst the disarray of European identity after the war. Nations and empires had dissolved and emerged. Like so many other Jewish Europeans, Wilder appreciated the gravity of existential choices in this increasingly hostile environment. He once remarked that “antisemitism is impossible to eradicate. It was impossible two thousand or four thousand years ago” (McBride 15). Although he and his family were relatively safe in their corner of Europe, Hitler’s rise to power manifested the racial anxieties on all sides. Wilder fled Berlin, where he was working at the time, in 1933, arriving first in Paris. Then he had to flee again, to the United States, landing in Hollywood. Wilder’s stepfather, grandmother, and mother were all killed by the Nazis, probably in the Kraków ghetto or the nearby Plaszów Labor camp, the facility depicted in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), which Wilder himself was eager to direct. This personal history—including his failure to bring his mother with him to the US—was never far in the background for Wilder (McBride 20–23), and, while this existential terror might be most evident in his 1945 documentary for the U.S. War Department, Death Mills, which documented Nazi atrocities, the tension driving it informs all his films.

As indicated, Wilder is known for his biting satire and dark sense of humor. His Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Blvd. (1950) are noir classics, and Ace in the Hole (1951), which I’ll discuss more, is widely regarded as one of the most cynical movies ever made (Hamrah). Against these stands the American Film Institute’s “Funniest movie ever,” Some Like it Hot (1959), and most of Wilder’s other films are comedies—indeed, romantic comedies. Wilder started in Hollywood as a screenwriter, and once he began directing his own movies, he became a dialogue-forward auteur, co-writing (most of his films were co-written with Charles Brackett or I.A.L. Diamond), directing, and often producing them. Yet, despite Wilder’s lifelong emulation of Ernst Lubitsch, to whom he is sometimes compared (he had a sign on his office wall: “How would Lubitsch do it?” {McBride 8}), Wilder’s style contained harder edges and greater ambivalence (McBride 9–10).

Defining the romantic comedy, or indeed defining the bounds of any film or literary genre, poses difficulties, whereas the economics of moviemaking are more clear. Movies are expensive to make, and turning a profit requires the filmmaker to rely on bankable commodities, like reliable genres and recognized stars and directors, to attract audiences. But classifying films into clear genres for the purpose of understanding meaningful distinctions in structure and content is always an academic puzzle. Thomas Schatz defines a genre as a kind of contract between filmmakers and audiences, a “static, dynamic system” in which each genre film is a satisfactory or unsatisfactory attempt to fulfill the contract. Schatz argues that each genre “continually reexamines some basic cultural conflict” (Schatz, 16). In a similar way, Leo Braudy considers a genre to be a way in which societies address various perennial problems (Braudy, 104–14). For Braudy, genre films are generally “closed” films (4451), but, unlike closed art films—which are bound by the director’s artistic will, like those by Hitchcock and Lang—genre films are “closed by convention” (112). Braudy is saying that, in closed films, the mythic tropes that form the concerns of audiences bind genre films to the hypotheses of the world given in the film, making it feel and operate as a separate space and time, whereas open films start before and then continue after their screentime, from and into the unpredictable and real world outside the film, not unlike the “reportage” styles of Renoir and Antonioni.

Schatz categorizes romantic comedy as a genre of “indeterminate space” precisely because the conflicts facing their member films are set in abstract, somewhat generic communities—i.e., basically anywhere, anytime—and celebrate social integration. Thus, their plots center on universally-redolent social groups—family members, best friends, employers, etc. (Schatz, 27–29; Grindon 12–16). In line with Schatz’s claim, almost every romantic comedy begins with some social obstacle between the protagonists that their love will overcome, and the audience can accept the relevant society no matter where the movie is set (Grindon, 3–7 ff.). It is standard, for instance, for romantic comedies to begin with one or both of the protagonists unhappy in their current relationship or recovering from a recent break-up or desperately alone, and it’s relatively common for some serious misfortune to befall one of the secondary characters. In Ernst Lubitsch’s classic 1940 The Shop Around the Corner, for instance, the store owner, Mr. Matuschek (Frank Morgan), having wrongfully accused his protégé, Alfred Kralik (James Stewart), of participating in an affair with Mrs. Matuschek, tries to shoot himself. Jon Turtletaub’s popular Sandra Bullock vehicle, While You Were Sleeping (1995), begins with Bullock’s character barely saving the man she thinks she’s in love with from being run over by a subway train. In Love and Basketball (Gina Prince-Bythewood, 2000), protagonists Monica (Sanaa Lathan) and Quincy (Omar Epps) break up over their competing basketball ambitions; in When Harry Met Sally (Rob Reiner, 1989), friends Sally (Meg Ryan) and Harry (Billy Crystal) endure multiple failed relationships before realizing they love each other. The “where and when” of these stories drops away.

Similarly, class distinctions often serve as the initial obstacle between the protagonists (Grindon 8–11), as in It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), where Ellie (Claudette Colbert), an heiress, and Peter (Clark Gable), an out-of-work Reporter, must transcend the bigotries of class status, or in The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940), where Tracy (Katherine Hepburn) is Old Money, like her former husband, Dexter (Cary Grant), her betrothed, George (John Howard), is New Money, and her new suitor, Mike (James Stewart), is a poor freelance writer. Social class separates protagonists in newer romantic comedies, too, like Roger Michell’s Notting Hill (1999), in which Anna (Julia Roberts) is a movie star and William (Hugh Grant) owns a little bookstore, or Jon Chu’s Crazy Rich Asians (2018), in which Nick (Henry Golding) is a Crazy Rich Asian (Singaporean) and Rachel (Constance Wu) is a first-generation Asian-American college professor raised by a single mother.

Culture clashes also provide popular social conflicts overcome by the comedic structure of romance. In My Big Fat Greek Wedding (Joel Zwick, 2002) the very Greek Toula (Nia Vardalos) marries nonGreek Ian (John Corbett); in The Big Sick (Michael Showalter, 2017), Kumail (Kumail Nanjiani) is Pakistani and Emily (Zoe Kazan) is American; in Something New (Sanaa Hamri, 2006), AfricanAmerican CPA Kenya (Sanaa Lathan) falls for White landscaper Brian (Simon Baker). The minimal summary required for these romantic comedies to suggest a plot indicates the domain of closed genre stories, which operate outside any necessary place or time.

By contrast, in genres of “determinate space,” according to Schatz, akin to the “open” genres that Braudy defines, like Westerns and gangster movies (Schatz, 27–29), the defining conflicts are existential, not social. Combatting forces vie for political, moral, or at least ideological control of territory, including the territory of the soul; consequently, the environment in these films supersedes the social relations. Choices become bound to time and space. The self becomes of a function of context, not of some timeless dynamic between lovers. Such movies must represent how one takes responsibility for one’s actions in a world in which the environment that defines the self loses its fixity and stability and instead changes, decoheres, and thus continually threatens the integrity of one’s own being. At this point, the structure of closed, indeterminate romance is useless as a model of existence, because it removes the necessity—and perhaps terror—of a choice made inside a specific time and place. As Sartre puts it in “Existentialism Is a Humanism”:

[Man] first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards. … Thus, the first effect of existentialism is that it puts every man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely upon his own shoulders. … The existentialist frankly states that man is in anguish. … When a man commits himself to anything …– in such a moment a man cannot escape from the sense of complete and profound responsibility.

In his essay “The Westerner,” (120–140), Robert Warshow claims, similarly to Sartre, that the protagonist of a western has “a moral clarity which corresponds to his physical image against his bare landscape” (125), indicating that in westerns, the relation of the individual to the impassive universe supersedes the social connections among members of a community. Note how, in this representative still from Shane (George Stevens, 1953), the Western hero (Shane, played by Alan Ladd) stands apart from the little family against an open sky, while the Starretts (Van Heflin, Jean Arthur, and Brandon De Wilde) are enclosed, even while outside, by the walls of their house. Similarly, in this still from the famous final shot of John Ford’s The Searchers (1954), Ethan (John Wayne) is barred from the domestic interior that represents the settled community that he has restored; his realm is marked against it in the stark orange of the desert dust. The point I’m making is not simply the familiar argument that the masculine hero can’t be integrated into society but that the form of each film is itself about one’s choice of life in particular historical circumstances, torn between open and closed modes of choice. In a closed or indeterminate mode, choices are part of the structure itself, the genre; in an open or determinate (contextually-bound) mode, the choices about who we are—the existential decisions that define us—are decoupled from the structure—and from the image itself—and made instead into a function of circumstance, becoming at once more consequential and more terrifying that the more universal choices we all make in response to love and family. Shane isn’t just alone; he is operating inside a different existential space; his decisions are not made by the structure itself, by how romance affects choices in general.

Importantly for my purposes, in his “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” Warshow claims, “The gangster is a man of the city” (118) “doomed because he is under the obligation to succeed, not because the means he employs are unlawful. In the deeper layers of the modern consciousness, all means are unlawful, every attempt to succeed is an act of aggression, leaving one alone and guilty…one is punished for success” (120–21). Sartre echoes this understanding of the Gangster, the killer:

When, for instance, a military leader takes upon himself the responsibility for an attack and sends a number of men to their death, he chooses to do it and at bottom he alone chooses. No doubt under a higher command, but its orders, which are more general, require interpretation by him and upon that interpretation depends on the life of ten, fourteen, or twenty men. In making the decision, he cannot but feel a certain anguish.

Both Paul Muni’s (Howard Hawks, 1932) and Al Pacino’s (Bran De Palma, 1983) Scarface’s, for instance, are depicted at the height of their success as ultra urbane, with all the marks of wealth and sophistication that place them in a city setting, even in interior scenes. And both are tortured souls. We could say the same about Michael Corleone in The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974), Henry Hill in Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990), Ricky Baker, Doughboy, and Tre Styles in Boyz in the Hood (John Singleton, 1991), or Eddie Bartlett, Lloyd Hart, and George Hally in The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939). Regardless of the decade, the gangster film portrays the anguishing internal battle of the individual between the forces of ambition and those of his or her moral compass, a battle that is quintessentially depicted in the city.

Rather, even though romances are usually set in real places, they almost always have a generic quality given by the myth of a happy society they explore, what Northrup Frye called “the green world.” Leger Grindon notes, “each [romantic comedy] …construct[s] its magical, comic setting in a distinctive manner” but the magical, utopian quality seems almost universal (Grindon 18–20). Tamar Jeffries McDonald remarks that romantic comedies give “the audience a high degree of closure with the happy ending” (Jeffers McDonald 14), indicating that romantic comedies are what Braudy refers to as “closed” films, by convention limiting the world of the film to the main couple, their family and friends, those for whom the film winds up happily.

I argue that Wilder’s romantic comedies, contrarily, take place in the real historical, territorial, world. In other words, while they are light and have happy endings, and do celebrate social integration, Wilder’s romantic comedies are at the same time what Braudy would call “open” films and what Schatz would call films of “determinate space”. Thus, they explore existential as well as social myths and real problems in the world outside the film, more like western or gangster films. Indeed, I think many of Wilder’s romantic comedies explore gangster themes, those in which Warshow claimed, “every attempt to succeed is an act of aggression.” And, I believe, this lends their happy endings a more existential quality that allows the audience to face the absurdity of modern life, beyond the—also very valuable—idyllic faith with which most romantic comedies make the absurdity rational. In other words, while still offering the satisfaction of a romance which bolsters the audience’s faith in the possibility of a happy community, Wilder’s romantic comedies, by framing that faith in the historical, social, and moral landscape of the real and troubled world outside the film, extend its scope. His romantic comedies help audiences believe that love is possible even in horrifying and absurd social or moral circumstances. For instance, A Foreign Affair (1948) and One, Two, Three (1961), famously, both begin with long takes of postwar Berlin. And yet despite the nightmarish conditions in which they find themselves—or perhaps even because of these—Wilder’s romantic protagonists manage to project an enduring sweetness that redeems not only the couple themselves, but also the films’ other characters, and indeed, even the members of the audience. Absurdly, the depth of their despair enables the joyfulness of their spiritual redemption.

I don’t have the space discuss every one of Wilder’s romantic comedies in depth. But I will survey them quickly, categorizing them into those that make my thesis easy to argue and those that seem on their face less in line with my argument. Then, to test the claim, I will make the case for a film that seems not to support it.

The Wilder romantic comedies fitting this thesis:

-

The Emperor Waltz (1948). In this film, Wilder’s only musical, set “around 1900,” American Virgil Smith (Bing Crosby) displays the marvels of American salesmanship by hawking a phonograph to Emperor Franz Joseph of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Richard Haydn). Farcical, of course, but an opportunity to pit rabid American capitalism and progressivism against the aristocratic values of the old Empire, and released at a time when it would be impossible for audiences to ignore the fate of the Empire in WWI, and of its ally Germany in WWII. Thus, the protagonists’ happy fate here is played out in the context of the great cost of America’s rise to power and the whimpering demise of Aristocratic Europe.

-

A Foreign Affair (1948), mentioned above, is one of the best fits to my thesis. Here, an American congressional delegation is sent to occupied Berlin after WWII to assess the morale of the American troops. Prim Iowa Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur) vies for the soul of Captain John Pringle (John Lund) against a Nazi-sympathizing cabaret singer (Erika Von Schluetow) played by Marlene Dietrich, with whom Pringle has been having a long-standing affair. Here, American puritanism is pitted against post-war German degradation, to the credit of neither. And yet, we wind up liking all the main characters, happy even for Erika when, at the end, the movie implies that she will evade the American authorities’ perfectly just attempt to sentence her to a labor camp by seducing the MPs assigned to her case.

-

Romantic comedies almost always begin with what’s usually referred to as a “meet cute” of the protagonists. In a perversion of the meet cute, however in Sabrina (1954), Wilder depicts Linus Larraby (Humphrey Bogart) barely saving Sabrina (Audrey Hepburn) from suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. The fate of the Larraby Corporation’s diversification into plastics is threatened because Linus’s brother David (William Holden) wants to marry Sabrina instead of the daughter of the plastics mogul for whom Linus has intended him; Linus duplicitously woos Sabrina away, meaning to abandon her as soon as David is married. It’s cruel. In addition, many viewers over the years have been put off by the casting here, also perverse and farcical: Humphrey Bogart was cast here at fifty-five and Sabrina, we are told, is seventeen at the beginning of the film. Hepburn was actually twenty-five at the time. This is surely intentional and quite unnerving. As Colin McArthur notes, too, “Men such as Cagney, Robinson, and Bogart seem to gather within themselves the qualities of the [gangster] genres they appear in, so that the violence, suffering, and angst of the film is restated in their faces” (McArthur 24). Thus, casting Bogart brings to his character in Sabrina his gangster persona. Hence, when Linus realizes at the end of the film that he is in love with Sabrina, we see the possibility of love amid crude American ambition in both its legal and illegal forms.

-

Some Like It Hot (1959). In this film, set in the 1920s, jazz musicians Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon), out of work after their speakeasy gets raided, witness the Valentine’s Day massacre at the hands of the “Al Capone” character Spats Columbo, played by George Raft (who like Bogart, was also inveterately cast as a gangster). To evade capture by Columbo’s mob, they take a job—dressed in drag—with an all-girls’ jazz band headed to Florida. The singer for the band, Sugar Kane Kawalczyk, is played by Marilyn Monroe. She has been ill used by a string of men, and drinks. Yet not only ranked as one of the funniest movies of all time, Some Like It Hot is redemptive and timeless, taking on existential issues of personal identity. Racing to get away from the gangs, Joe kisses Sugar goodbye, during a performance, as Josephine. He and Jerry, as Daphne, usurp the yacht of millionaire Osgood Fielding (Joe E. Brown), who has fallen in love with Daphne, for their getaway. Here, in the taxi boat, Daphne is forced to reveal to Osgood that he is really Jerry, a man, making way for one of the greatest last lines in film history, Osgood’s “Nobody’s perfect.”

-

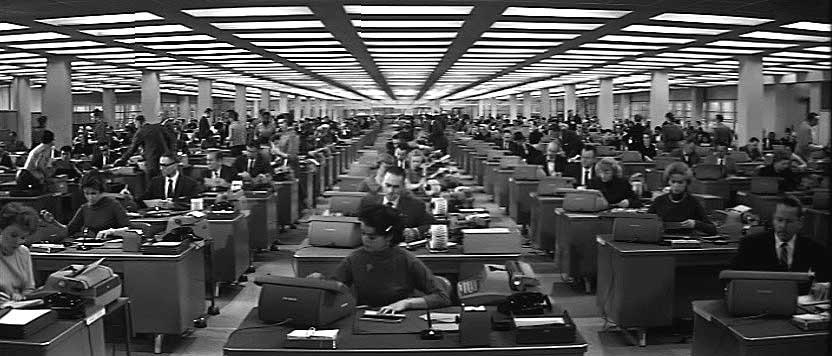

“In a way,” Wilder claimed, “I based The Apartment (1960) on The Crowd” (King Vidor, 1928) (Wilder, in Brooks, 156). For anyone who’s seen both films, this hardly needs saying. Note the comparison of shots from the beginning and end of each film here:

The opening shots of The Crowd (1928) [left] and The Apartment (1960) [right] are nearly identical: a series of establishing shots of busy New York City, then a low shot of the main characters’ office building, moving up its face to a window which, when we fade through it, reveals the correspondingly uniform and monotonous workroom.

In the closing shot of The Crowd, however, [left] [MGM] we see the couple laughing, in a movie theater, facing the camera, after Mary Sims (Eleanor Boardman) has decided for no apparent reason, to stay with her husband John. In the corresponding shot from The Apartment (1960) [MGM] [right], the protagonists are in a private space, smiling at each other.

The Crowd is far from comedy, however. The main character in that film, John (James Murray), like C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) in The Apartment, goes to New York to make his fortune at an insurance agency. But John in The Crowd goes nowhere in his job, argues with his wife and her family over it, and falls into a state of drunken despair when their daughter is killed by a truck. Although the couple seems to reconcile, we leave the movie with a sense of absurd resignation, the couple suddenly in the audience of a movie comedy, laughing away. Wilder’s CC Baxter, on the other hand, is alone with his beloved Ms. Kubelick (Shirley MacLaine) at the end of the film, and they’re about to leave the city together. Hence, Wilder here keeps intact Vidor’s devastating condemnation of modernity while nonetheless spiritually lifts the main couple out of their degradation, taking us with them.

-

One, Two, Three (1961), to which I referred earlier, marks a high point in Wilder’s mix of farce, biting cynicism, and redemption. James Cagney plays C.R. MacNamara, the director of Coca-Cola West Berlin. Here again, the film begins with establishing shots of post-war Berlin, East and West. Among other banners, some East German protesters hold up one asking, “What’s Going on in Little Rock?” referencing the battle in the US over civil rights, and making sure that the audience does not distance themselves from the turmoil depicted on the screen. Here again also, casting ties the audience to the world outside the film: Cagney, typecast as a gangster but for a couple of his works and thus, like Bogart, bringing that persona with him, thus also brings the ruthless ambition that Warshow states is characteristic of the gangster, eager as MacNamara is to become European head of operations in London. His boss at Coca-Cola—based of course in Atlanta—sends his precocious Southern-Belle of a daughter (Scarlett, played by Pamela Tiffin) to stay with MacNamara’s family to forget the most recent of her many young admirers. While supposedly under MacNamara’s supervision, Scarlett secretly meets, weds, and becomes pregnant by the rabid East German communist, Otto Ludwig Piffl, played by Horst Buchholtz. In the meantime, MacNamara’s staff struggle to shake the habits of life they learned under Nazi control, always standing up when their boss walks by, clicking their heels when accepting their assignments, and barely managing not to give him the Nazi salute. MacNamara’s wife, Phyllis (Arlene Francis) is tired of Europe and of C.R.’s many dalliances and yearns to return to a wholesome life in the States. Eager at first to annul the new marriage and get Scarlett back home, MacNamara changes gears when he discovers the pregnancy and that Scarlett’s father is coming to visit the next day. Frantically making Otto over into a Western-sympathizing son of the old Aristocracy, MacNamara saves the marriage, impresses his boss, and wins back his wife. No one is spared Wilder’s contempt in this film (except maybe Phyllis), yet love triumphs for both couples, and we leave the film feeling optimistic—but certainly not in a daydream.

-

In Avanti (1972), Jack Lemmon’s arrogant businessman, Wendell Armbruster Jr., travels to Italy to claim the body of his just-deceased father, a titan of American industry. There he meets what he perceives to be a low-class, dumpy Englishwoman, Pamela Piggot, played by Juliet Mills (in a particularly crushing moment, he even calls her “fat ass”). It turns out Pamela’s mother was the longtime mistress of Armbruster Sr., with whom she died in a car crash on the last of their annual rendezvous on the idyllic Mediterranean island. Here, American efficiency and ambition are pitted against the sophistication and gentility of the small European town. Wendell is married, and often talking to his wife on the phone, and Pamela is nearly penniless. Yet we’re uplifted when the two follow in their parents’ footsteps, ending the film with their plans for a lifetime adulterous affair.

A quick overview of the four Wilder romantic comedies that do not so readily seem like ruinous, acidic social commentary:

-

In The Major and the Minor (1942), Ray Milland’s Major Philip Kirby befriends Susan Applegate, played by Ginger Rogers, a grown woman pretending to be twelve years old in order to get the children’s rate on the train home to Iowa from New York, where she has failed to find her fortune. Of course, Kirby has fallen in love with Susan, but understands his feelings as avuncular. Hijinx ensue.

-

1957’s Love in the Afternoon casts Gary Cooper, normally typecast as an all-American hero—Mr. Deeds, Sergeant York, Lou Gherig, Marshal Kane in High Noon (1952), etc.—into the role of Frank Flannagan, a notorious libertine who seduces women, often married, across the great hotels of Europe. The husband of one of his conquests hires a private detective, Claude Chevasse, played by Maurice Chevalier. Chevasse’s probably-seventeen-year-old daughter, Ariane, again played by Audrey Hepburn, has fallen in love with Flannagan through the file in her father’s office, and successfully seduces—and makes and honest man—of him.

-

In Irma La Douce (1963), Jack Lemmon’s Nestor Patou, a Parisian police officer, falls in love with the unrepentant prostitute, Irma, played by Shirley MacLaine. Fired from his job, Nestor relies on Irma financially, but can’t shake his jealously over her clients. So he disguises himself as a client— Lord X from England—in order to keep an eye on Irma, but the real Nestor winds up competing with Lord X for her affection. Ultimately Lord X must die; but Nestor is accused of his murder. Here again, hijinx.

-

Lastly, Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) “flopped with American viewers and critics” (Desowitz). R.M. Hodgens called it “[a] particularly grimy comedy” (Hodgens 60). Reassessed and restored in 2002, the film stars Dean Martin, basically playing himself as a horrible person. “Dino” is detained in a tiny Nevada town by aspiring songwriters Orville Spooner (Ray Walston) and Barney Millsap (Cliff Osmond) in hopes of selling him a song. Knowing that Dino is a womanizer, Barney convinces Orville to pimp out to Dino his beautiful wife Zelda (played by Felicia Farr)—about whom Orville is insanely jealous. To assuage Orville’s puritanical resistance to the scheme, Barney convinces him to hire a real prostitute (Polly the Pistol, played by Kim Novak) to pretend to be his wife while Dino is in town. Polly enjoys being an honest woman for a change. Dino goes out on the town when he strikes out with the fake “Mrs. Spooner.” Zelda, drunk and angry at Orville, passes out in Polly’s trailer behind the town bar; waking up to Dino, who is there to see Polly, Zelda figures out Barney and Orville’s plot. Zelda pretends to be Polly and has sex with Dino, in order to seal the recording deal for her husband. Orville and the real Polly enjoy a night of “wholesome” married life.

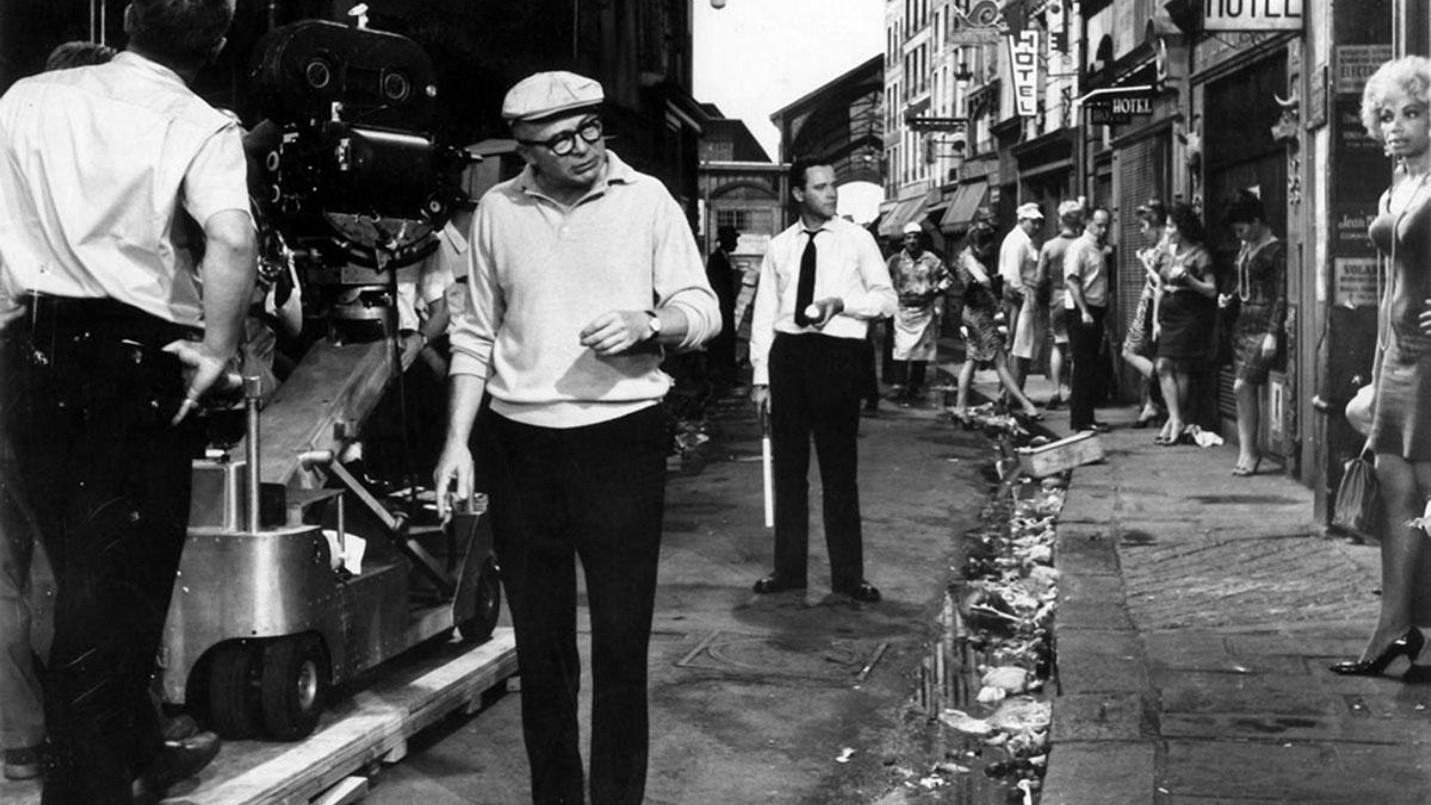

It’s Kiss Me, Stupid on which I’ll spend more time. In his review for the Los Angeles Times in 2002, Bill Desowitz compared Kiss Me, Stupid to “Wilder’s earlier flop, the acidic journalistic critique ‘Ace in the Hole.’” Ace In the Hole (1951), mentioned earlier and generally characterized as film noir, is also often taken to be Wilder’s darkest film (McBride, e.g., 246). McBride calls it a “profoundly felt Holocaust allegory” (246). Desowitz’s comparison to Kiss Me, Stupid is apt, and I would suggest, intentional: Ace In the Hole [below, left] and Kiss Me, Stupid [below, right] are set in then-present-day Nevada and New Mexico, respectively, Wilder’s only two films to evoke the Hollywood western genre. Both depict a western desert location; both depict the rural area with a Mexican-style building standing alone in the middle of nowhere, and both even depict the star riding in his car while being towed to the gas station.

In Ace In the Hole, Kirk Douglas’s Chuck Tatum is “a ruthlessly ambitious reporter…who has been fired by big-city papers for various forms of insubordination and other irresponsible behavior” (McBride 50). Seeing the possibilities for a big news story in the cave-in of a local man (Leo Minosa, played by Richard Benedict) at an old and sacred native American site, Tatum arranges to slow his rescue down to a snail’s pace (using a weird contraption that evokes an oil rig) in order to keep the story alive. Tourists flock to the site, and any number of little businesses crop up to serve them, including a carnival. Minosa’s wife (Jan Sterling), who is raking in the money at her husband’s Mexican café and gift shop, starts sleeping with Tatum. Ultimately, Mrs. Minosa leaves town with her newfound fortune, Minosa dies in the cave, and Tatum, in the last shot, keels over dead toward the camera. Not comic. Not romantic.

And yet, Kiss Me, Stupid plays with very similar themes. In the opening sequence, over the credits, we are introduced to Dino, played by Dean Martin, as a famous and successful—but really very debased— Las Vegas act, during his last performance there of the season. He jokes about the chorus girl next to him: “Last night she was banging on my door for forty-five minutes. But I wouldn’t let her out.” He falls down, faux-drunk, on stage, remarking ‘[my mother] is eighty-five years old and she don’t need glasses. She drinks right out of the bottle.” Leaving Las Vegas for Los Angeles against a veritably noir background, Dino has to take a detour through the desert, changing the mise en scene from the noir neon-spotted vice capital of the world to the wide-open spaces, which Dino experiences as an embarrassing backwater. This parallels the debauched Chuck Tatum coming from New York to Albuquerque, and arrogantly lording his sophistication over what he claims is a hick town newspaper.

Dino is forced to drive through a town called ‘Climax,’ Nevada. Apparently just a belabored name choice for the setting of a sex romp, however, there is a real “Climax Mine” in Nevada with the utterly barren landscape depicted in the film, in the middle of the Great Basin Desert. And the Climax mine is just about ten miles from the Nevada National Security (Nuclear Testing) Site (below). The last above-ground test occurred in 1962, just two years before the release of Kiss Me, Stupid. Given Wilder’s bent for setting his films in real places relevant to the plot, I think we must take this as intentional. The small town in Kiss Me, Stupid lies just outside the blast zone. This parallels Ace in the Hole’s setting at a gift shop adjacent to a sacred Native American burial ground, long since abandoned and looted, the ghosts of whose former tenants petrifies Minosa.

And of course, Dean Martin’s casting here is as calculated to unnerve as is Bogart’s, Cagney’s, or Cooper’s: making reference in his Las Vegas act to the Rat Pack and to Frank Sinatra, and again, basically playing himself, Martin carries with him into the film all that his image evokes: enormous fame, political influence, pop idolhood—the tuxedo he wears and the glass in his hand seem to hover about him everywhere he goes. We might gossip about his possible Mafia connections. Wilder here makes it extremely difficult to shake Martin apart from Dino, which adds to the eerie realism of this supposed farce, much more subtle but just as wrong-footing as the scenes of post-war Berlin in A Foreign Affair and One, Two, Three.

https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q19068220)

So, here, as in Ace in the Hole, we are placed in a specific cold-war context, essentially a ruin. And the look of both films evokes a western, the central vehicle of the myth of US Western expansion. Polly the Pistol is reminiscent of both Mrs. Minosa and Erika Von Schlutow in A Foreign Affair, having followed a man who abandoned her into what is now a degrading existence (indeed, like Mrs. Minosa, the last we see of Polly is her driving out of town). Thus, as in Ace in The Hole, the American west is here represented as a desert with a gas station, stark and beautiful but hick and sleepy, poised to be exploited by an unlikable and unscrupulous gangster type, one who tries to take advantage of a desperate woman who finds herself stuck in the ruins. Now the film, I think, starts to look at lot more like a social commentary: in come the Americans, all Hollywood and economically dominant, with a naïve belief in their own sophistication, to exploit the market possibilities of their newly-taken territory, which includes its women.

Whereas, however, Ace in the Hole tells the story of the inevitable fall of the sinful Tatum (literally, his dead body falls to the floor in front of the camera), Kiss Me, Stupid treats its sinners with love. Orville and Zelda are reunited, Orville and Barney’s song is a hit, Polly buys a car and quits the Belly Button Inn. Indeed, the film becomes a nice fit into Stanley Cavell’s concept of the “remarriage” comedy of Hollywood’s golden age (1). Orville and Zelda—high school sweethearts—fit Cavell’s bill as a “pair who recognize themselves as having known one another forever, …before there was a past, before history” (31). And as in Cavell’s remarriage comedies, “marriage has its disappointment—call this its impotence to domesticate sexuality without discouraging it, or its stupidity in the face of the riddle of intimacy” (31), which I take to characterize Orville and Zelda’s attitudes toward the adultery they both commit. Unlike Chuck Tatum and Mrs. Minosa, however, Orville and Zelda are redeemed—from their sins of adultery, from the childish association of sex with love, from their adulation of Dino and all that he represents. Orville and Zelda find in one another a way to bear with the awfulness of the actual modern world in which we live. No forest glen here, but a dull American town probably subject to the various illnesses caused by nearby nuclear tests, subject to—and surrounded by—death. And yet, like Sisyphus in Camus’s version of that myth, they are happy:

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor. … Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. … The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. (23)

This absurd redemption is represented in the closing scene. Orville meets Zelda and Barney, he thinks, to see a lawyer about a divorce. The hardware store under the lawyer’s office sells TVs, and at just the moment that Orville arrives, Dino’s show is on in the window display, and a large crowd of his fans has gathered to watch. In a marked contrast to the opening sequence, however, where we saw Dino “live” on stage surrounded by chorus girls, we now see Dino, alone, but multiplied on the many screens, singing Orville and Barney’s song, and giving them, and Climax, their overdue shout-outs. This time, the Dinos are small and hazy, and over their images are superimposed the faces from the little Climax audience reflected in the store window. Here, Dino, the big-city sophisticate, the gangstertype bully, has been put in his proper place: screens through a window, observed by the ordinary people who make up the American TV audience, essentially at three removes from the film’s viewers. Unlike Chuck Tatum and the Star-struck gawkers who come to see him in action, here, everybody stands at an aesthetic distance from the Hollywood star, from their former misdeeds, and from their desperate situation.

What makes for this aesthetic distance? What creates the redemptive lightness of Kiss Me, Stupid out of the stark tragedy of Ace in The Hole? This is the deeply philosophical question I take Orville to be asking in the penultimate line of the film, as Barney signs autographs, Polly drives by, and Zelda returns the wedding ring that Orville lent Polly for the evening with Dino: “I must be going out of my mind. I can’t figure out any of this … How would you, when did she, why would he…?” Zelda responds only, “Kiss me, stupid.” This, by my lights, suggests the existential absurdity that Wilder brings to all his romantic comedies. While Wilder seems to see people as Aristotle does in the Politics: “when separated from law and justice, … the worst [animal] of all; … the most unholy and the most savage of animals, and the most full of lust and gluttony” (Politics I:2), yet, somewhere within us is the possibility of love and there—absurdly—hope.

An earlier version on this paper was presented at the Eastern Conference of the American Philosophical Association, Panel of the International Association for the Philosophy of Humor, Montreal, January 4, 2023.

The author would like to thank the IAPH, Lake Forest College, and Imani Downer (undergraduate research assistant for parts of this project) for their support.

Works Cited

Academy Award Acceptance Speech Database.

Aristotle. Politics. Trans. Benjamin Jowett. Internet Classics Archive, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.html

_______. Nicomachean Ethics. Trans. W.D. Ross. Internet Classics Archive, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.1.i.html

Armstrong, Richard. Billy Wilder: American Film Realist. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company Publishers. 2000.

Braudy, Leo. The World in a Frame : What We See in Films. Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Press, 1977.

Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. translated by Justin O’Brien. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Translation originally published by A. A. Knopf, 1955. Originally published as Le Mythe de Sisyphe by Librairie Gallimard, 1942. https://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil360/16.%20Myth%20of%20Sisyphus.pdf.

Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Cambridge, MA. Harvard U. Press, 1981.

Chandler, Charlotte. Nobody’s Perfect: Billy Wilder; A Personal Biography. S. & S. Nov. 2002. C.336p. Filmog. ISBN 0-74321709-8.

Desowitz, Bill. “Reviving ‘Kiss Me, Stupid’ Is a No-Brainer; Movies Restoration of a Censored Seduction Scene Improves the Overlooked 1964 Billy Wilder-Izzy Diamond Comedy Starring Dean Martin as ‘Dino.’ The Los Angeles Times. 2002.

Grindon, Leger. The Hollywood Romantic Comedy. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Hamrah, A.S. “Some Like it Fraught,” Bookforum MAR/APR/MAY 2022.

Hodgens, R. M. “Review: Kiss Me, Stupid.” Film Quarterly 18, no. 3 (1965): 60–60. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nevada_Test_Site.

Jeffers McDonald, Tamar. Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. New York: Columbia U. Press, 2007.

McArthur, Colin. Underworld U.S.A. New York: Viking Press, 1972.

McBride, Joseph. Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge. New York: Columbia U. Press, 2021.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “Existentialism Is a Humanism.” 1946. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/sartre/works/exist/sartre.htm

Schatz, Thomas. Hollywood Genres. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Warshow, Robert. The Immediate Experience; Movies, Comics, Theatre & Other Aspects of Popular Culture. [1st ed.]. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1962.

Wilder, “Interview with Billy Wilder,” Cinema 4 (1969, 19–24), quoted in Ian Brookes, “The Eye of Power: Postwar Fordism and the Panoptic Corporation in The Apartment,” The Journal of Popular Film and Television (37:4, 2009, 150–60)