Jesse Chaney

Covering the Unabomber: It was 'all hands on deck' for Helena journalists reporting national story

It was a typical day at the Independent Record 25 years ago today, when the newsroom began getting questions about a Unabomber suspect by the name of Theodore Kaczynski.

“We started getting these weird calls: ‘What do you know about this guy in Lincoln?’” said David Shors, who was associate editor at the time.

Although skeptical that the infamous Unabomber whose mailed bombs killed three people and injured 24 others had been living just 60 miles north of town, a reporter and a photographer headed that way to see if they could figure out what all the fuss was about.

THOM BRIDGE, Independent Record

“Dave looked at me and kind of laughed and said: ‘They say they have the Unabomber in Lincoln. You want to go see if it’s real?’” said Carolynn Bright, who was a reporter who went by Carolynn Farley at the time.

So Bright and chief photographer George Lane hit the road, not expecting the trip to amount to much.

“I think we stopped at the gas station there, and I remember going in and asking them: ‘Do you know anything about the Unabomber being here?’” Lane said. “They just kind of looked at me like, ‘What?’”

When they arrived at the end of Kaczynski’s road outside of town, they came across someone who they later learned was an FBI agent. Lane said the man was wearing a heavy-down coat in light-jacket weather, which was their first clue that he wasn’t from around here.

“I thought this must be the place, because this guy’s so far out of his comfort zone,” Lane said.

Lane struck up a conversation and asked if there was something going on up the road.

“He didn’t say a word,” Lane said. “He just sort of looked at me and smiled.”

A little while later, Bright took Lane’s truck back into town while he stayed behind. That’s when Lane saw a white Ford Bronco coming down the road from the cabin, which he instinctively knew was carrying Kaczynski to Helena.

THOM BRIDGE, Independent Record

“I ran up trying to shoot through the window, but it was so dark you couldn’t get anything,” he said. “ … I couldn’t follow him because Carolynn was gone.”

In an article about the ordeal, reporter and photographer Mark Goldstein recalled that the IR had an “ace up its sleeve” in Lincoln-based staff reporter Marie Hoeffner. Through her contacts in the area, she learned Kaczynski’s name even before the county sheriff did and was able to call his neighbors seconds after finding out where he was apprehended.

“Marie’s contacts proved invaluable and provided crucial information for at least three of the six stories we broke nationally during the week,” Goldstein wrote.

Back in Helena, the IR staffers who remained at the office were scrambling to figure out where Kaczynski was being taken.

“It was all hands on deck as far as reporters and anyone who knew how to work a camera,” said Wayne Klinkel, who was the newspaper’s staff artist at the time.

Although the newspaper had staff posted outside the county jail, the Federal Building and other places around town, it was four young photojournalists from the University of Montana who ended up snapping the first photos of the Unabomber as he was escorted into a small FBI office in the Arcade Building along the Walking Mall. But the IR was able to get copies of the photos for the next day's paper, after the students showed up at the office asking if someone could help develop their film.

GREGORY REC

“I said, 'I’ll develop your film, but right now I’m going to tell you I want two photos from it for our use,’” Lane said. “One kid said 'no,' and I said, 'Well, Butte’s 60 miles away. Start driving.’”

The students reluctantly agreed to Lane’s terms, he said, and “I spent most of my night scanning in photos and getting them into the computer system.”

Meanwhile, the phones in the newsroom were ringing off the hook. Goldstein noted in his article that the major networks were contacting Shors hourly to pump him for information because their news crews were having trouble getting to Helena, as Delta had only two flights per day into the city and both of them were full.

“The first night all of the phones were just ringing and ringing and ringing, and it was from all of the big newspapers just wanting interviews about what was going on, what we knew,” Bright said. “You could just assign someone to just do that for those first three days.”

After the arrest

The day after the arrest, Shors asked Klinkel if he could sketch Kaczynski in court because cameras were not allowed in the courtroom. Although he hadn’t done any people sketches since college about 20 years prior, Klinkel found some old colored charcoal and notepads buried in his desk and headed to the courthouse.

Klinkel said he got into the courtroom early and sketched the room and U.S. District Judge Charles C. Lovell well before Kaczynski showed up for his first hearing, which lasted all of seven minutes. The TV networks had arrived by that point, and he said they were all over him the moment he stepped out the door.

“They ripped my sketches out of my book and taped them to the side of the truck and videoed them right on the side of the truck,” he said.

Klinkel said he ended up drawing about a dozen sketches of Kaczynski’s court hearings in Helena, but only half of them were used. That was the first and last time he has ever done court sketches, he said.

“It was a whole new ballgame for me,” he said. “It was very intimidating, but in the end I guess I can say it was very rewarding. I guess I accomplished what I was supposed to.”

The front-row seats reserved for the IR staff were a big help.

“Charles Lovell made sure that we had three seats in that courtroom because we were the locals,” said Eve Byron, another former IR reporter who helped cover the case.

The FBI, on the other hand, was less accommodating.

“The FBI couldn’t be less helpful, I thought,” said Charles S. Johnson, who was a longtime reporter for the IR State Bureau.

In a story published the day after Kaczynski's arrest, Johnson wrote that some FBI agents would walk by without responding to reporters’ questions. Others smiled and said they weren’t allowed to say anything, he wrote.

AP Photo, Douglas C. Pizac

“They refused to answer reporters’ questions, telling them a public information officer would show up soon. Some local reporters waited for nearly two hours outside the restaurant for the spokesman, who never appeared,” he wrote. “Finally, when a CNN television news crew arrived, one federal agent directed reporters to the site five miles south of Lincoln near Kaczynski’s cabin. Federal agents parked trucks in the middle of the dirt road that forked up toward the cabin and ordered reporters not to trespass.”

It wasn’t until two days after Kaczynski’s arrest that the first photo of his cabin was published in the newspaper, as reporters could not get close enough to see it.

“The guy was known for bombs, so they weren’t going to let anybody go anywhere near his cabin because they though he booby trapped everything,” Byron said.

However, Johnson found what he described as a “pretty lousy picture” of the Unabomber’s 12-by-10 foot shack attached to public tax records.

“This was pre-cellphones with cameras, and I needed to get it to the IR to scan,” he said, noting that he had to convince the county assessor and appraiser’s office to part with the photo. “ … I offered to leave my wallet.”

Keeping in touch

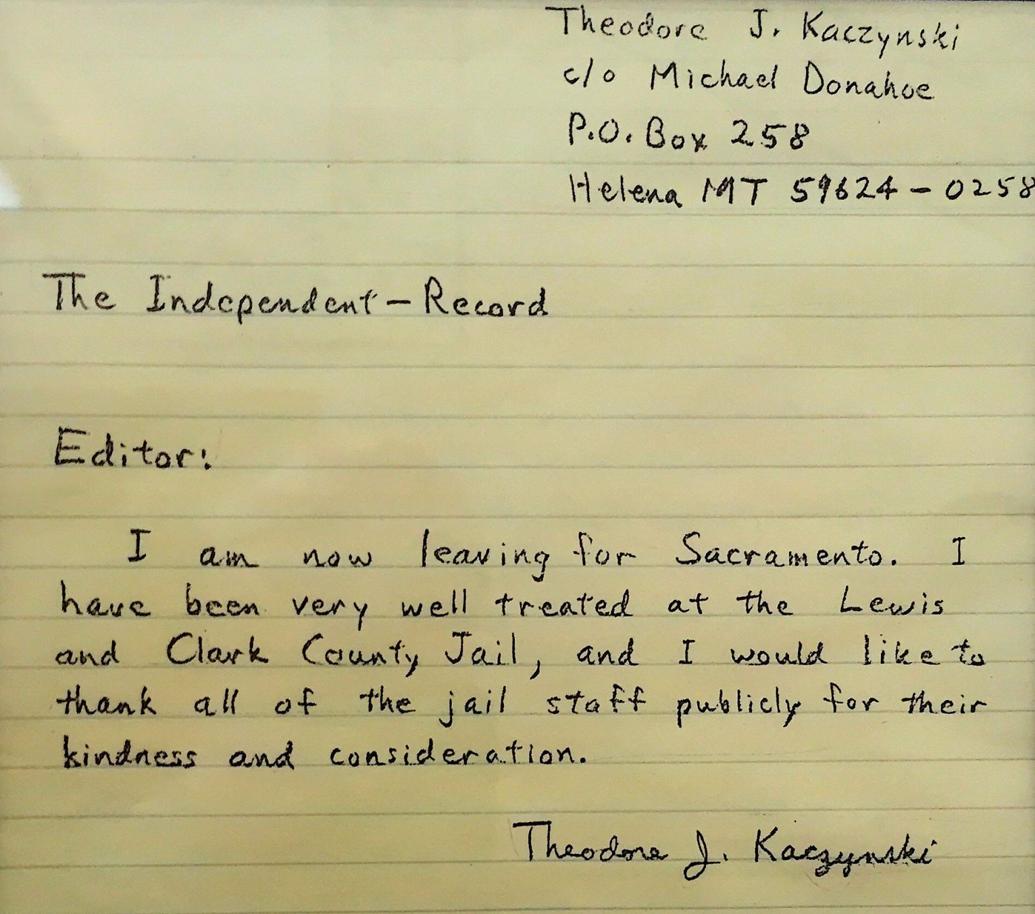

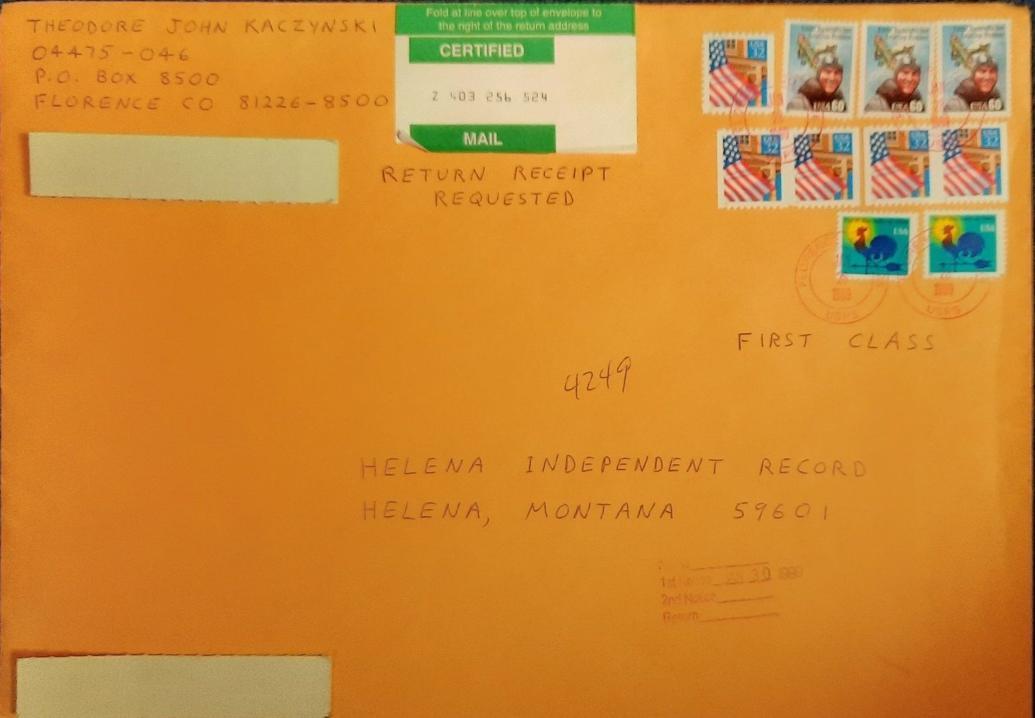

Despite the Independent Record’s repeated attempts to contact him over the last 25 years, Kaczynski only wrote to the Independent Record on two occasions that Shors can remember.

“I am now leaving for Sacramento,” he wrote in the letter published June 26, 1996. “I have been very well treated at the Lewis and Clark County Jail, and I would like to thank all of the jail staff publicly for their kindness and consideration.”

Kaczynski sent a considerably bigger package dated Jan. 30, 1999, which contained two letters addressed to the managing editor of the IR and a handwritten copy of another letter sent to the editors of the Missoulian. Among this correspondence was his scathing critique of a book titled “Unabomber: The Secret Life of Ted Kaczynski.” Authored by Shors and Chris Waits, who was described as Kaczynski’s friend and neighbor for 25 years, the book was published by the Independent Record and Montana Magazine earlier that month.

David Shors photo

“The book is a hoax, and a clumsy one at that,” a letter from Kaczynski begins. “It contains a certain amount of fact, which gives it an air of authenticity, but it is largely fabricated. When all of the documents in my case have been made public (as they probably will be within a few years), Waits will be revealed as the pathetic fake that he is.”

Shors said the opposite was true, as the information that came out over the years ended up confirming the book’s accuracy. And while he has no regrets about the book, Shors noted that his wife once asked: “Why in the hell would you make Ted mad?”