John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker

Unabomber: On the Trail of America's Most-Wanted Serial Killer

Critical Praise for John Douglas and Mark Olshaker’s MINDHUNTER

Prologue: ANOTHER DAY AT THE OFFICE

Appendix 1: AN OVERVIEW AND CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY

Berkeley Bomb Note, June 2,1982

Geiernter Letter, April 24,1995

New York Times Letter, April 24,1995

(Passage deleted at the request of the FBI.)

(Passage deleted at the request of the FBI.)

(Passage deleted at the request of the FBI.)

San Francisco Chronicfe Letter, June 27,1995

New York Times Letter, June 28,1995

Washington Post Letter, June 28,1995

New York Times Letter No. 2, June 29,1995

Tom Tyler Letter, June 30,1995

Appendix 3: THE UNABOMBER MANIFESTO

Industrial Society and Its Future

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MODERN LEFTISM

DISRUPTION OF THE POWER PROCESS IN MODERN SOCIETY

INDUSTRIAL-TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY CANNOT BE REFORMED

RESTRICTION OF FREEDOM IS UNAVOIDABLE IN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

THE ‘BAD’ PARTS OF TECHNOLOGY CANNOT BE SEPARATED FROM THE ‘GOOD’ PARTS

TECHNOLOGY IS A MORE POWERFUL SOCIAL FORCE THAN THE ASPIRATION FOR FREEDOM

SIMPLER SOCIAL PROBLEMS HAVE PROVED INTRACTABLE

REVOLUTION IS EASIER THAN REFORM

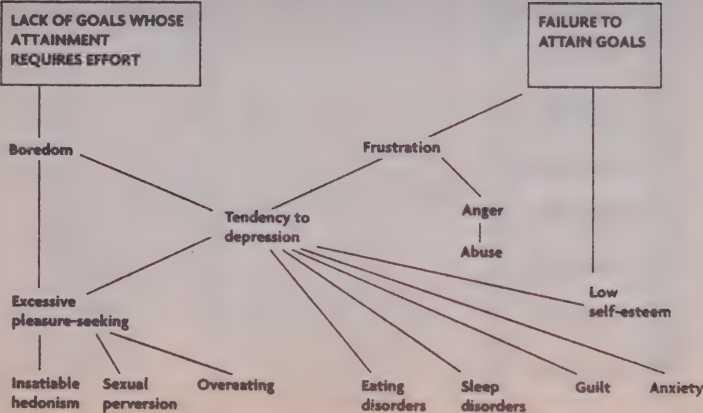

DIAGRAM OF SYMPTOMS RESULTING FROM DISRUPTION OF THE POWER PROCESS

Front Matter

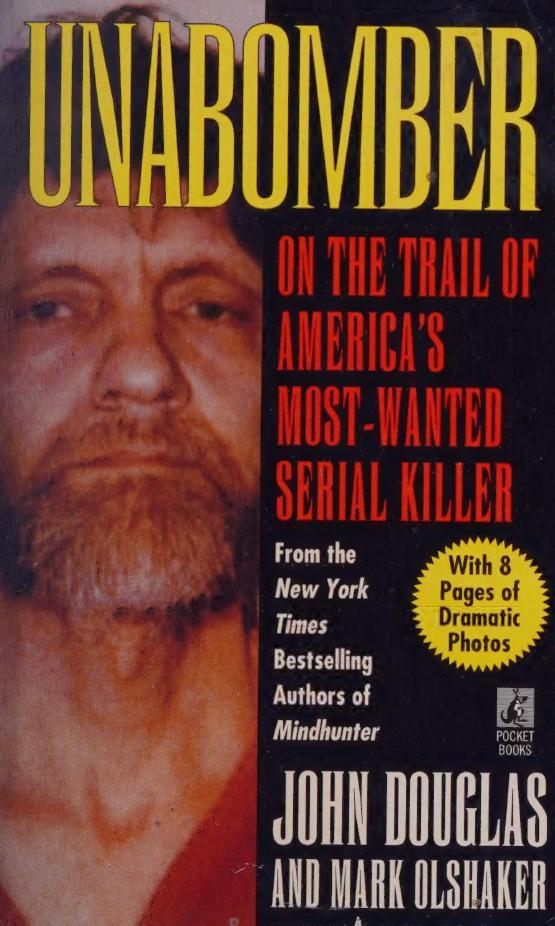

Front Cover

With 8 Pages of Dramatic Photos

POCKET BOOKS

From the New York Times Bestselling Authors of Mindhunter

JOHN DOUGLAS

AND MARK OLSHAKER

Front Flap

$6.50 U.S.

$8.50 CAN

DON'T MISS THE FASCINATING

BOOK THAT TAKES YOU INSIDE

THE FBI's ELITE SERIAL CRIME UNIT,

FROM NEW YORK TIMES

BESTSELLING AUTHORS

JOHN DOUGLAS

AND MARK OLSHAKER

MINDHUNTER

(RECENTLY NOMINATED FORAN EDGAR AWARD)

COMING SOON IN PAPERBACK FROM POCKETBOOKS

Critical Praise for John Douglas and Mark Olshaker’s MINDHUNTER

“This singularly important study [is] as readable as a mystery novel. . . .”

-—Publishers Weekly

“Mr. Douglas and Mark Olshaker . . . have written a fascinating report on the criminal profiling program of the FBI’s behavioral science unit and have provided a disturbing look at this country’s most savage murderers. . . . Mr. Douglas sets out to produce a good true-crime book, but because of his insights and the power of his material, he gives us more—he leaves us shaken, gripped by a quiet grief for the innocent victims and anguished by the human condition.”

—Dean Koontz, The New York Times Book Review

“One of the first to develop the specialty of ‘criminal-personality profiling’. . . . Douglas is justifiably proud of its success. . . . Readable, popular. . . . [Mindhunter is] recommended for true-crime collections.”

—Library Journal

Publisher Details

The sale of this book without its cover is unauthorized. If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that it was reported to the publisher as “unsold and destroyed.” Neither the author nor the publisner has received payment for the sale of this “stripped book.”

An Original Publication of POCKET BOOKS

POCKET ROOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

1996 by Mindhunters, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 0-671-00411-5

First Pocket Books printing May 1996

10 987654321

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Cover photo courtesy of AP/Lewis and Clark Sheriff Dept.

Printed in the U.S.A.

AUTHORS’ NOTE

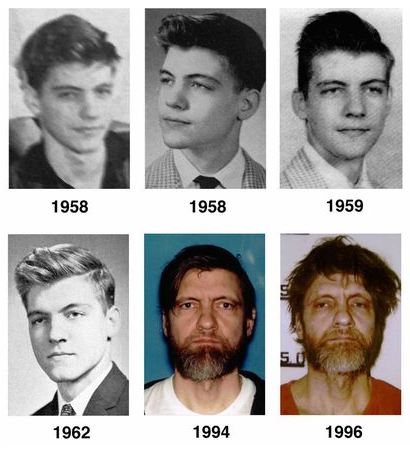

This book is a report on an ongoing case in which news continues to break virtually on a day-by-day basis. It chronicles and gives one perspective on the eighteen-year hunt for a notorious terrorist and serial killer, culminating in the apprehension of suspect Theodore J. Kaczynski.

But we must caution that Mr. Kaczynski is just that—a suspect. According to our system, he and everyone else must be presumed innocent unless— and until—proven guilty in a court of law. Everything that follows should be read in that context.

This book truly has been a team effort, and it would not have been possible without the diligent and devoted, practically around-the-clock efforts of each membei of our team. Jay Acton, Ann Hennigan, and Carolyn Olshaker worked side-by-side with us from beginning to end, reading, researching, writing and rewriting, and generally keeping us going. It is no exaggeration to say that in many ways this work is as much theirs as ours. Special thanks also to Bennett Olshaker, M.D., for his insight, analysis, and interpretation of psychological and psychiatric issues.

On the publishing side, our intrepid editor and publisher, Lisa Drew, headed up a parallel team that included Pocket Books publisher Gina Centrello, Julie Rubenstein, Tris Cobum, Marysue Rucci and a host of others, some of whom we’ve never even met, who all pulled together to make this book a reality literally m a matter of days after it had been only a concept. Special thanks are due to Simon & Schuster Consumer Books Division President Jack Romanos, who, along with Gina, originated that concept and pushed it forward.

Finally, we want to acknowledge all of John’s colleagues at the FBI and the other law enforcement agencies—federal, state, and local—who worked so long, so hard, and so well to see this case through and see justice done. They have the undying gratitude of us all.

Special thanks also to Mark Morril and Emily Remes for fighting the good fight for us, and fighting it exceedingly well.

—John Douglas and Mark Olshaker April 1996

Epigraph

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.

—William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Prologue: ANOTHER DAY AT THE OFFICE

I just can’t handle another major case, I said to myself. I don’t know how I’m going to handle all the ones I’m working already.

It was late spring of 1980. It might have been a nice day in the rolling countryside or it might have been raining and dreary. I would have had no way of knowing. I was in my windowless office several floors belowground at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. I was the only full-time profiler in the Bureau, which was one agent too many as far as most of the brass at headquarters were concerned. J. Edgar Hoover had been dead only eight years, and his shadow still loomed large. The Hoover FBI had been interested in “just the facts, ma’am,” and anyone who thought he could help solve a crime by claiming to describe the personality of some unknown perpetrator would likely have been suspected of witchcraft.

I hated to turn anything down. My colleagues at Quantico used to say I was like a prostitute who couldn’t say no to a customer. On my desk were case files from a series of horrifying murders of young black children in Atlanta, Georgia, that the local press was saying had to be the signature of some Klan-like hate group but which I felt was probably the work of a single young black male—not a popular opinion and not one likely to win me many friends. There was a guy in Wichita, Kansas, calling himself the BTK Strangler, for “Bind, Torture, Kill.” At the same time I was trying to help Scotland Yard crack the case of the Yorkshire Ripper who was butchering women in north central England.

Those were just three of the hundred fifty or so active cases I was working on at the time. In addition, I was trying to convince anyone who would listen, both within the Bureau and at police departments from coast to coast, that we had something real and valuable to offer them. This meant meetings, consultations, lectures, and interviews all over the country. And any time I happened to find myself near a state or federal prison where there might be a serial killer, rapist, arsonist, or assassin for me to interview and learn from, I’d be there.

I wasn’t spending time with my wife and two daughters. I was drinking too much, exercising like a fiend because I was too wound up to relax, and doing all the things I’ve always counseled the people who work for me not to do. I’d become obsessed with my mission, just like the people I was hunting. And driving everything was the overwhelming fear of failure. At this delicate stage of my program’s development, it would take only one significant screwup to give the brass downtown the ammunition they needed to sink us. So not only did I have to take on more cases than one person could sensibly or responsibly handle, I couldn’t afford to be wrong on any of them.

But when Tom Barrett, a special agent working in the Chicago Field Office called me that spring afternoon in 1980, I put down what I was doing and listened. Tom and I had been agents together in the Detroit Field Office. Then, at the same time I was assigned to Milwaukee, Tom had gone to Chicago.

“We’ve had a bombing in Lake Forest,” Tom explained. “June tenth. Percy Wood, the president of United Airlines, was injured opening a package addressed to him at his home in Lake Forest that exploded when he opened it.”

Had the airline gotten any threats? I asked, beginning a series of standard questions.

“No. No ransom demands or anything like that. There’s no apparent motive. I know you’re doing a lot of work and research in sexual homicide and trying to profile the offenders. Do you think you could do anything on this type of guy?”

I thought about it for a moment. In addition to the work we’d been doing on serial killers and rapists, we were starting to delve into the backgrounds and personalities of assassin types. My research partner and Academy teaching associate, Robert Ressler, and I were in the process of interviewing such assassins as Robert Kennedy’s murderer, Sirhan B. Sirhan; Arthur Bremer, who had shot and paralyzed Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace; and Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme and Sara Jane Moore, both of whom had made attempts on the life of President Gerald Ford.

Just as there is no single profile for a serial killer, we were finding there was no single profile for an assassin. Those who did it up close and personal, like Sirhan, represented one type. Those who worked at a distance—anonymously—like the killers of President John Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., represented another type. Those were the types I considered the most cruel and cowardly. I had already made a connection in my own thinking with arsonists and would later apply the same logic to product tamperers such as the craven Tylenol Poisoner.

As I listened to Tom Barrett describe the crime, I started thinking there could be a connection with bombers, too. A careful bomber will set or send his device and be nowhere nearby when it goes off. That had to tell me something about personality. And after all, I recalled, it was a bombing case that had really created the field I’d staked out for myself in the FBI.

“Okay, Tom,” I said at last. “Let me see what I can do.” .

THE MAD BOMBER

It was the hunt for an elusive serial bomber terrorizing the public that actually began modem behavioral profiling.

By the mid-1950s, New York City had been racked for more than a decade by a series of explosions in such highly public places as train stations, movie theaters, and libraries. The earliest device had appeared on November 16, 1940, a crude pipe bomb found on a windowsill of the Consolidated Edison Company building on West Sixty-fourth Street. It was found before it went off". One blast in 1954 had gone off in Radio City Music Hall. Newspapers had dubbed him the Mad Bomber. The entire city lived in fear. I was a kid back then, growing up in Brooklyn, and I remember this case very well. Some of the devices exploded, causing injury and mayhem. Some of them were discovered and disarmed before they went off. And some just turned out to be duds. Fortunately no one had yet been killed. But two things were clear: the bomber’s work had been growing in sophistication over the years, and anywhere you went in the course of a normal day, you could be the bomber’s next victim.

Like other kinds of terrorists, many bombers feel a need to communicate with their intended victim, which is the public at large. That urge in the nature of the beast. Through neatly printed letters he had written to various newspapers, one important fact was known about the bomber: he had a grudge against Consolidated Edison, the New York City power company. His letters, signed “F.P.,” were filled with florid references to Con Ed’s “ghoulish acts” and “dastardly deeds,” and he claimed that some unspecified ailment or injury from Con Ed and unspecified “others” had caused him “financial loss.” He ended one letter to the New York Herald-Tribune with the statement, “I merely seek justice.”

The problem with tracking down someone from this specific but scant evidence is that Con Edison was a huge but relatively new company, actually “consolidated” from the myriad other power companies that had served New York since the nineteenth century. Each of these companies had maintained its own records, many of which no longer existed, the ones that did were in no organized order. So while police and Con Ed clerical employees began poring over records of disability claims and complaint letters going back decades, they knew the chances of finding this particular needle in the haystack were remote. Even if the file existed and someone happened upon it, how would they know he was tLe guy?

Initially, the police had tried to keep a lid on the details of the crimes, figuring the more information they let out, the more they would encourage the bomber and the myriad copycats that inevitably crop up in high-profile cases. But as the Mad Bomber’s work continued, there was little they could do to contain the public’s outrage and hysteria. A bomb exploded inside Grand Central Station, nearly killing a redcap.

Then, just before 8:00 p.m. on December 2, 1956, as the city was gearing up for a typically festive Christmas season, a bomb ripped through the Paramount Theater in Brooklyn. Six people were injured, three critically.

That was the last straw. New York City Police Commissioner Stephen Kennedy announced that every resource would be thrown into the effort to trap the Mad Bomber and bring him to justice.

This was a publicly comforting pronouncement, but the fact of the matter was that NYPD had already thrown all of the traditional crime-solving resources into the hunt and so far nothing had worked. So Inspector Howard Finney, director of NYPD’s crime lab, decided to try something new.

For more than a hundred years, fictional detectives such as Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes had been solving cases by inferring, or profiling, the personality of the perpetrator. In the 1841 classic “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,’’ Dupin had predicted a large ape as the killer when reason couldn’t get any human type to fit his behavioral profile. But this was the stuff of books and movies until a cold December day in 1956 when Inspector Finney took two detectives with him and paid a visit to Dr. James A. Brussel, a Greenwich Village psychiatrist who also served part-time as assistant commissioner of the New York Department of Mental Hygiene. Though few in the department had any hope a civilian shrink could help crack a case in real life, Finney asked the psychiatrist if he could draw any conclusions about the bomber’s personality from the details of the crime scenes or the style and content of the letters.

Brussel, as you might expect, knew little about bomb-making, so he started by asking the police officers to analyze the devices for him. They told him that the bombs represented highly skilled work, the product of an individual with some experience, and that they had grown increasingly powerful and sophisticated over the years. To Brussel, this certainly indicated that the unknown subject, or UNSUB, as we say in police terminology, probably had had a job involving electricity, metalworking, pipe fitting, or something related, which would have been consistent with employment with a large power company. Since these skills are often learned in the military and in 1956 many American males were veterans of World War II, it seemed likely he had some military background involving technical skills.

The one thing that could be said with some certainty was that the bomber believed Con Ed and the mysterious “others” were responsible for some accident or event that had left him chronically ill and that he had been obsessed with this belief for at least the last sixteen years. This obsession had probably been going on a lot longer than that, since Brussel knew from his psychiatric experience that most fixations take time to brew and fester before they are acted upon. But though the first device had been directed specifically against Con Ed, the bomber had quickly expanded his targets to a wide variety of public spaces, as if he was now trying to punish the public at large, and believed that everybody in New York City was potentially out to get him.

“What kind of man would harbor such a belief?” Dr. Brussel wrote in his memoirs, Casebook of a Crime Psychiatrist. “I was forced to a conclusion: the Mad Bomber was suffering from paranoia.

“Paranoia, to define it in textbook language, is a chronic disorder of insidious development, characterized by persistent, unalterable, systematized, logically constructed delusions. The definition fit the Mad Bomber, as far as I knew him, perfectly.”

The bomber’s communications with newspapers certainly demonstrated to Brussel a persistent, systematized, and logically constructed delusion. It seemed to have developed insidiously and, judging by the growing sophistication and lethality of the bombs, was continuing to develop. From his psychiatric perspective, Brussel knew this type of individual to be narcissistic, self-centered, and convinced of his own moral rightness, even if the whole world seemed to be allied against him. But for these hostile forces, he would succeed, conquer, flourish. Maybe it was Con Ed originally, but now everyone was the enemy.

That was not to say you could pick this guy out of a crowd from his behavior. Quite the contrary, except for his directed antisocial behavior—in this case the bombings—he might be expected to behave in a legal and proper fashion. After all, he was the one who had been wronged, and far be it from him to stoop to the level of those beneath him. He could be expected to write letters making all sorts of bizarre legal threats, but in his own context, that would seem absolutely proper. He would never, for instance, threaten someone directly. This, interestingly enough, was a trait we were later to see over and over again in serial killers. The one they actually felt they had the grudge against—mother, girlfriend, boss—was often the last person they could bring themselves to confront.

In a sense, Brussel surmised, the Mad Bomber probably saw himself as both victim and avenging angel. Such people are tough to treat from a psychiatric point of view because they don’t believe there’s anything wrong with them. The problem is with everyone else.

Inspector Finney found this discussion interesting, but he hadn’t heard anything he couldn’t have figured out on his own, and nothing so far to help him get closer to the bomber.

“Is there any way you can describe him to us?” Finney asked.

Brussel hesitated. He wasn’t a cop. He hadn’t examined physical evidence. He didn’t know any bombers personally. But the police had come to him for help, and he thought he’d take a shot.

“He’s symmetrically built,” he began, “neither fat nor skinny.”

The three cops exchanged skeptical glances. “How did you arrive at that?”

Actually, it had been a statistical guess, Brussel later admitted in his memoirs. He had followed the work of the noted German psychiatrist, Ernst Kretschmer, who had studied thousands of psychiatric patients in an attempt to match physical build with personality type. Kretschmer’s study suggested that about 85 percent of all paranoiacs had a symmetrical, or athletic, body. As weird or baseless as this might at first sound, follow-up studies by other pioneers such as psychologist William Sheldon have shown a certain validity to this approach. We’ve found, for instance, that manic-depressives tend to be heavyset and nervous; high-strung people tend to be thin.

So, emboldened by this first step, Brussel continued. The Mad Bomber would now be in his early fifties. Paranoia is a slowly developing disease, the doctor explained, usually not coming into full bloom until the mid-thirties. They knew that the bomber had been at work for at least sixteen years, and that his latest activities marked the blossoming, not the planting, of the initial seed.

The communications Finney showed Brussel were the work of a neat, obsessively meticulous man. Every letter of every word was carefully penned and precise. If and when his Con Ed personnel file was found, it would reveal a solid, reliable, cooperative worker. He would have been polite, punctual, and neatly dressed—up until the day that the perceived injustice occurred. Then his world would have turned upside down.

The level of articulateness of the letters suggested the bomber had some education—probably not college, but high school. More significant, though, was his use of the “dastardly deed” type of phrase, which hadn’t been in popular usage since Victorian melodramas. Also, he continually referred to “the Consolidated Edison” or “the Con Ed.” He had obviously been around since before 1940, yet most New Yorkers routinely referred to the company simply as “Con Ed,” without the definite article. This suggested someone of a European background, to whom English was not a first language. In spite of the letter writer’s obvious anger and passion, there was a formal, stilted tone to each paragraph. In fact, this guy, in his meticulous, obsessive fashion, was probably thinking in his native language, then translating into English.

The way Brussel was evaluating the letters was a precursor of what we now refer to as psycholinguistic analysis, and as we shall see, a trained and experienced profiler can reach a rich lode of information this way.

On a related front, something else about the handwriting struck Brussel as significant. While twenty- five letters of the alphabet were consistently sharp and blocky, the IT’s were oddly but consistently misshapen into twin rounded forms the psychiatrist speculated might subconsciously represent the female breasts or the male scrotum.

“His censoring conscience kept all his other printed characters standing rigidly at attention, but there was something inside him so strong that it dodged or bulldozed past his conscience when he penned a W."

The method of planting bombs in theaters—slashing the undersides of seats—represented the same kind of deep, hidden motivation. Brussel thought this could have something to do with an Oedipal tendency the bomber didn’t want to face. From there, Brussel constructed a portrait of a man who’d never gotten past the Oedipal phase, who would have no close friendships with men and no meaningful relationships with women. He would not be married and might likely still be a virgin. Brussel guessed he’d never even kissed a girl. He would live alone or with a female relative who reminded him of his mother— either an aunt or sister. Since the police had already concluded that the types of tools the bomber used probably required a house-size workshop rather than something that could be crammed into an apartment, this suggested that he lived with female relatives rather than alone. This was not the type of person who would live alone in a house.

So, putting it all together, Brussel described a symmetrically built, neat, and clean-shaven middleaged white male of European background, a polite but friendless loner who lived with a sister or aunt in a house. There would be nothing flashy about his appearance. When he was employed, presumably by Con Ed or one of its precursors, he would have done his job well but would not have mingled with other employees. He would have eaten lunch alone and would not have attended company picnics or other social events.

Both from the psycholinguistic analysis and from the types of weapons used, Brussel was willing to bet the Mad Bomber was not only European but Slavic. A Slav would be more likely to use a bomb than a gun to settle his scores, Brussel felt. If he was a Slav, he’d probably be a Roman Catholic, and if his religious devotion fit in with the rest of his life and habits, he’d be a regular churchgoer.

As to where he lived, Brussel focused on Connecticut. Most of the letters had been postmarked either in New York City or in Westchester County. A man as fastidious and careful as this would never make so basic a mistake as to mail his communications from his own town or city. He would mail them either in New York, where he was setting his bombs, or somewhere between his home and New York. On his forays into the city, he could drive partway and then take either a commuter train or subway the rest of the way in. Brussel knew there was a large Polish community in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and that the state in general had many residents of Slavic origin. To get from Bridgeport, say, to New York City, he would have to go through Westchester.

The man believed he had a chronic illness that was Con Ed’s fault. Whether it actually was or not would be hard to determine. The facts wouldn’t necessarily get in the way of this guy’s logic. But again playing the odds, Brussel felt there were three good possibilities: heart disease, cancer, and tuberculosis. Cancer was a long shot, due to the time that had obviously elapsed since the first incident. If it was cancer, he would either have been cured or long since dead. With the antibiotics available in the mid-1950s, tuberculosis was treatable and manageable. That left heart disease. Since this covers such a multitude of causes and effects, both physical and emotional, Brussel’s profile called for someone who either had, or thought he had, a chronic heart condition.

As a wrap-up, Brussel told the detectives that whenever they found this middle-aged, foreign-born white Slavic male with a heart condition who lived in a house in Connecticut with his sister or aunt, he would be fastidiously but not flashily dressed.

“When you find him, chances are he’ll be wearing a double-breasted suit. Buttoned.”

So that was the profile James Brussel gave to the frankly stunned police officers. But then what? Many times I’ve given highly detailed profiles to local police departments around the country, only to have someone respond, “Okay, Douglas, but what’s his name and address?” As much as the people in my unit and I may resent working our asses off helping someone with a case that’s primarily their responsibility, not ours, there is a point to this. A profile, if you have faith in it, might help you limit your suspect pool, but it only goes so far. What the profile should suggest is a proactive strategy for using it.

And that was, in fact, what Brussel did in this first real-life profile. He suggested to the police that they use every means at their disposal to publicize his evaluation, forcing the bomber into the open to respond or comment. On one level, he was having the satisfaction of terrorizing the public and outfoxing the police, proving to himself what he had believed all along—that he was smarter than everyone else. But on another level, in his everyday life, he was still this insignificant nobody who probably got ignored at lunch counters and department stores. The increasing size and complexity of his bombs spoke to Brussel of the bomber’s growing frustration at not being recognized. A part of him wanted to go public, to let the world see him in all his glory.

Finney pointed out that the department had maintained a policy of letting out as little information as possible. But “by putting these theories of mine in the papers,” Brussel recalled saying, “you might prod the bomber out of hiding. He’ll read what I’ve said about him. Maybe a lot of my theories will be wrong, maybe all of them. It’ll challenge him. He’ll say to himself, ‘Here’s some psychiatrist who thinks he’s clever, thinks he can outfox me—me, the Bomber! Well, he’s all wet, and I’ll tell him so.’ And then maybe he’ll write to some newspaper and tell how wrong I am. He might give his correct age and other clues—who knows? It’s an outside chance, but it’s worth trying, I think. And if my theories are anywhere close to the mark, there’s a chance somebody might recognize him—a mail carrier, a local merchant, a fellow employee. . . .”

The police did take Brussel’s advice, though they may have been sorry they did. For weeks, everyone saw the Mad Bomber—in the neighborhood, on the train, in movie theaters and libraries, in parks and supermarkets. A special Bomb Investigation Unit was established under the direction of a veteran and well- respected chief inspector named Edward Byrnes. Throughout late December and into January of 1957, Byrnes’s unit handled between fifty and a hundred bomb reports a day!

As Brussel imagined, with all this publicity, the bomber would feel compelled to show off his cleverness and expertise. Early in the afternoon on December 24, an unexploded bomb, obviously the Mad Bomber’s handiwork, was found in a phone booth at the main branch of the New York Public Library at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street. Four days later, another was found in a seat at the palatial Paramount Theater in Times Square.

Brussel himself got a taunting phone call in the middle of the night from a caller identifying himself as “F.P.” Brussel and the police had been prepared for such a possibility, but the caller was smart enough to get off the line before a trace could be initiated.

Meanwhile, as they had the time, various Con Ed employees were slowly and laboriously plowing through the mountains of employee claim records. But now with Dr. Brussel’s guidance, at least they had some idea what they were looking for.

At the company’s main office at Fourteenth Street and Irving Place, south of Gramercy Park, three secretaries were reading through injury compensation files whenever their other duties allowed. By the second week in January 1957, they were up to files from the late 1920s and into the 1930s that had belonged to some of the companies that had been consolidated into Con Ed. There were so many liability claims, so many disgruntled employees, so many individual incidents that their eyes tended to glaze over with the details.

Late on Friday, January 18, one of the three women, Alice Kelly, came upon a file folder marked “Metesky, George.” According to the record, George Metesky had been employed as a generator wiper at the Hell Gate plant of United Electric & Power, one of Con Ed’s precursors, beginning in 1929. On September 5, 1931, a backdraft of hot gases from a boiler had knocked him down. Though doctors found no serious or permanent injury, Metesky insisted that the incident had left him permanently disabled. At first the company let him stay home and gave him sick pay, but eventually he was perceived to be malingering and was dropped from the payroll. United Electric seemed to be one of the “others” F.P. referred to in his letters.

In a claim filed before the Workmen’s Compensation Board on January 4, 1934, Metesky asked for permanent disability pay, stating that the accident had left him with tuberculosis. The claim was denied, and over the next three years Metesky wrote increasingly volatile letters demanding his rights, bitterly complaining about the “dastardly deeds” perpetrated against him by the company. But then he became silent and disappeared. The last entry in the file was dated 1937.

Recognizing the phrase “dastardly deeds,” Kelly dug out the rest of Metesky’s personnel files and sifted through them carefully. Mr. Metesky had joined the marines after World War I and had been trained in the service as an electrician. He had had a sterling employment record up until his accident—everything Brussel had predicted. His age at the time would make him fifty-four if he was still alive. He was a Roman Catholic born in Poland. His last known address was 17 Fourth Street in Waterbury, Connecticut. Other than the fact that he’d dismissed tuberculosis in favor of heart disease, Brussel’s profile seemed right on the money. And if this was the UNSUB, he’d provided enough information for a reader to recognize a hot file when she saw it.

Byrnes’s Bomb Investigation Unit asked the Waterbury police for a check on the specified premises, but at first they couldn’t find any George Metesky. It had belonged to a Mr. Adam Milauskas in the 1920s and had been deeded over to his son, George Milauskas, who had owned it during the time in question. A discreet check in this rather shabby neighborhood of

Irish, Italians, and Middle Europeans revealed that though he’d never changed it officially, George Milau- skas had, since grade school, gone by the name Metesky. Neighbors described him as polite but “strange,” a loner with no known close friends.

The clincher came on Monday morning when a letter from F.P. arrived at the office of the New York Journal-American. It made reference to a date he must have figured would be meaningless to the paper and the police but which would demonstrate his own superior knowledge and understanding: September 5, 1931—the date of George Metesky’s accident at the Hell Gate power plant.

Late that night, four New York City detectives drove up to Waterbury, Connecticut, and knocked on the door of number 17 Fourth Street. George Metesky, a man of medium height and average weight, answered the door in his pajamas. He was unfailingly polite to the detectives and willingly complied when they asked for a sample of his handwriting. It matched the angry and taunting letters exactly.

“What does F.P. stand for?” one of the officers asked.

“Fair play,” Metesky replied.

The detectives placed him under arrest and asked him to get dressed for the ride into the city. He left the room to do so and to inform the two unmarried sisters with whom he lived. When he returned, he was wearing a double-breasted suit, neatly buttoned.

Normally, when a suspect is subjected to what police call the “perp walk,” where he is paraded past the hungry press on his way to appear before a judge or magistrate, you see a glazed expression, an attempt to hide his face or place a coat over his head, or you will hear shouted claims that he is innocent or the wrong man. The newspaper photos of the captured Mad Bomber show a smiling man with a twinkle in his eye who is clearly enjoying all the attention and publicity. I find this very significant.

Metesky was kept in custody in Bellevue Hospital, where medical tests revealed that one lung was actively tubercular. A course of antibiotic therapy was instituted, and gradually, Metesky’s condition improved. In reviewing his own reasoning process and his exclusion of tuberculosis, Brussel saw his analytical mistake: his failure to realize that many paranoiacs would mistrust a doctor as much as they would mistrust anyone else, feeling they knew more, and therefore would not go for treatment.

Brussel visited Metesky several times over the years at Matteawan State Hospital, which has a facility for the criminally insane. He was always neat, proper, and very cordial.

The police in various cities continued to call on Dr. James Brussel, including such celebrated cases as the Boston Strangler and the Coppolino murder.

Special Agent Howard Teten, who taught applied criminal psychology at the FBI Academy, became interested in Dr. Brussel’s work in the late 1960s and early 1970s and began corresponding and consulting with him, trying to apply Brussel’s observations and principles to the police understanding of criminal behavior.

When I came to the Academy as a young agent, fresh from a couple of years as a field agent in Detroit and then Milwaukee, Teten and his associate, Dick Ault, were the FBI’s recognized masters of what was then referred to as behavioral science. Behavioral profiling, in the sense that Brussel practiced it, was strictly an informal activity Teten practiced in his spare time when police colleagues who had been through his course at the Academy would ask his hunch on a particular open case they were working on. Eventually, police students began asking for help from some of the other behavioral science instructors, including Ault, Jim Reese, Dick Harper, Tom O’Malley, Bob Ressler, and the new guy, me.

I was in my early thirties when I was assigned to the Behavioral Science Unit, teaching classes to police officers often a generation older than me. It used to scare the hell out of me that I might be standing up there in front of the class, imparting the FBI’s received wisdom on a particular case to a group of hardened cops, and I’d have one raise his hand and say, “Hold on a minute, Mr. Douglas. I worked that case and that’s not the way it went down at all,” or “I arrested that guy, and he was nothing like what you say.”

Where did we get off, I wondered to myself, telling cops their own business? If we were going to say anything meaningful about a case or a type of crime, we’d better damn well know what we were talking about.

Not all of the training took place at the Academy. We also conducted week-long “road schools,” in which usually two of us would go to a local police or sheriff’s department or an FBI field office and teach for a week, then move on for a week at another location before heading back home. Bob Ressler and I used to do a lot of these road schools, and I recall one time in 1978 we were in Sacramento. I remember commenting to him that away from home, there are only so many margaritas you can drink and only so much television you can watch. As long as we were out on the road anyway, why didn’t we go into the prisons wherever we were and interview some of these guys we’d been talking about in class? Get the story straight from the horse’s mouth, as it were. That way, we could start to see what really made them tick and tell the cops and other agents something valuable.

I already had something of a reputation as a blue flamer in the Bureau, but Ressler went along with me, even though we both knew this was something Headquarters was unlikely to applaud or instantly approve. Even more than “Just the facts, ma’am,” the primary principle by which we all lived was “Don’t embarrass the Bureau.” We both knew that if anything we did came back to cause embarrassment to the Bureau, they’d hang us out to dry like surplus laundry.

The first subject we interviewed was Edmund Kemper III, an inmate at the California State Medical Facility at Vacaville, between Sacramento and San Francisco. As a teen, Kemper had shot and killed both his grandparents, had done time in a juvenile facility, had been released, and was regularly reporting his psychological progress to a therapist while he was picking up, raping, and murdering college coeds and other young women in and around the University of California at Santa Cruz. He had finally worked through his displaced anger and rage and killed the one person he really felt had messed up his life—his mother—and then a close friend of hers. Having gotten this out of his system, he turned himself in to police. Certainly this is an oversimplification of Kemper’s story, but those are some of the basic details.

Kemper is a giant of a man with an equally large intellect. He spoke to us for several hours on several occasions and gave us tremendous insight into the mind of a serial killer. We went on to interview many other violent offenders and eventually compiled a rigorous study with Dr. Ann Burgess of the University of Pennsylvania. Eventually we published two books based on our work: Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives, and the Crime Classification Manual.

Gradually but steadily I became more and more involved in profiling and less and less involved in teaching until I was the only full-time profiler in the unit. But as I’ve implied, what I and such other colleagues as Special Agent Roy Hazelwood, another instructor who became interested in profiling, were doing was far from FBI or forensic science orthodoxy.

In one murder case in New York, for example, the police had no idea after a year who had strangled a young woman on the stairway landing of her apartment building. Their only lead was a pubic hair from a black male, which had been found in the body bag. I looked at crime scene photos and told them their UNSUB was a white male in his early twenties who was unemployed, had no driver’s license, lived within a mile of the scene, was related to someone in the building, would be disheveled in appearance and nocturnal by habit, would spook easily, had been institutionalized, and was on medication. He had no college education, military experience, or serious criminal record, I told the police, and he had undoubtedly already been interviewed in the normal course of the investigation. And I turned out to be right.

We needed successes like that to make our potential clients, as well as our bosses and fellow agents, into believers. And when Tom Barrett called me from Chicago to tell me about an unknown bomber, I was very much looking for believers.

TYPES OF BRIBERS

Before you can come up with an accurate profile or effective proactive strategy, you have to know what kind of crime you’re dealing with. It may be a murder, but there are many types of murders and murderers, and unless you know how to classify the one before you, you’re not going to get very far. The classification system my Quantico colleagues and I developed was based on firsthand knowledge from the experts—the offenders themselves. Before our study, there were a lot of suppositions based on academic teachings and psychological theory, but no one could actually say what aspects of those suppositions came from real- world experience.

In classifying a bombing, the critical elements to us are victimology, crime scene indicators, victimoffender relationship, type and/or construction of the bomb, and any elements of staging.

Then we ask a number of questions. The more of them we can answer, the more complete our product can be.

Linder victimology: Is the victim known to the offender? What is the risk level—that is, how strong were the victim’s chances of becoming a victim? What is the offender’s risk level of being identified in or around the scene? For example, if he places the bomb in the middle of a full football stadium, his risk level is obviously very high. If he mails it to a private home, his risk level is obviously considerably lower. And either of these circumstances will tell you something meaningful about the bomber.

Were the targets chosen discriminately or indiscriminately? To make the determination you review the delivery system used by the bomber. For example, was the bomb addressed to a specific person or was it addressed to the university or to an individual department?

It is more difficult to assess the motive of the offender if the bombs are sent indiscriminately. In assessing a series of cases, you are looking for common denominators or threads that link the cases together. Unfortunately, a single bomb is more more difficult to use in assessing motive than a series. In assessing cases, more is generally better.

How many crime scenes are there? Are they clustered in one limited geographical area or are there many locations?

Criminals are no different from law-abiding people when it comes to being creatures of habit. We feel comfortable in areas where we work and live, and so does the bomber. Consequently, the first set of cases will be in one of these familiar areas. And he will remain there as long as he believes his identity will not be revealed or his personal safety compromised.

What about specific place and time? Indoors or outdoors? Daylight or nighttime? Urban, suburban, or rural?

We consider all of these factors when we are attempting to place a label on the motive as well as to develop personality characteristics of the offender.

Was the bomb delivered by mail, planted by the offender, or carried by a third party? Sending a package bomb through the mail requires much more technical ability. The package bomb must be detonated by the intended victim when the package is opened, not before.

In most cases in which a third party is involved, such as terrorist airplane bombings, the carriers do not know they are delivering a bomb and in many instances they are killed or injured by the blast.

All of the aforementioned factors are gauged to help determine the risk level on the part of the offender and victim. Offenders begin to increase their risk level over time. Psychologists and criminologists will sometimes state that the reason for this change in behavior is that they want to be apprehended. It has been my experience, on the other hand, that at a certain point offenders begin to feel invincible or uncatchable. As I point out frequently, they feel they are above the law and smarter than the authorities. This is a positive change in favor of law enforcement, because sooner or later the bomber will make a mistake.

How many offenders are there? Many bombers are no different from extortionists who send some form of communication to the intended victim or law enforcement agency. In this communication they almost always use the plural “we” or “our” to imply that they are part of a larger group or organization. ,

If the assessment determines that the motive is group-caused, there will be more than one offender. However, due to their paranoia, typical bombers they almost always act alone. Why? Because they don’t trust anyone.

We also have a number of statistical factors that we must plug in, such as race and gender. Historically, most bombers have been male, and most have been white. Over the years we occasionally have had female bombers, but their targets tend to be family members or close associates. Very rarely, if ever, will they go for an unknown or indiscriminately chosen target.

Most bombers are single or involved in a marriage of convenience. The wife or girlfriend is made to feel subservient to the bomber.

What about staging? Many crimes are staged. That is, there is an attempt on the offender’s part to deflect the investigation away from the logical suspect. During the course of my career I have done many analyses and testified in cases where a husband or wife has killed his or her spouse. An attempt is subsequently undertaken to make the scene look as if the spouse died at the hands of a burglar or rapist.

Since we know a lot more about the subtle details of how each type of crime is “supposed” to look than the offender, staging often gives us a lot of good behavioral evidence to go on. (So I’ll just say parenthetically here that if you’re thinking about killing your spouse and trying to make it look like some other type of crime, forget it. It won’t work.)

The bomber will often stage his crimes by sending a communique. The analysis should determine if the crime fits the message that the bomber wants us to believe. We must always be suspicious. He may be setting us up, particularly if he has left few clues and has eluded law enforcement for some considerable period of time.

What are the forensic findings? This evidence will be critical in linking any potential suspects to the crime.

Crime detection has become much more sophisticated over the years. Blood, hair, fiber, fingerprints, and psycholinguistic analysis may link a suspect to a bombing. Psycholinguistics, as I’ve implied earlier, is a fancy word for the process of analyzing language with the purpose of assessing the personality and critical choices of the author of the communique.

If letters or packages are sent, we have added evidence that can be assessed forensically. Though the capability didn’t exist back in 1980 when we started profiling Unabomber, now we can often subject licked stamps to DNA analysis.

As for the bomb device itself, what level of expertise was necessary to construct it? Is the bomber a technician who’s had certain vocational or educational experience? Or could he have gone to the nearest library and checked out one of the many books that have been published describing and depicting how a bomb can be made?

Are there unique components? Unique workmanship? Unique design? Are the bomber and builder the same individual?

Another important factor to assess is the risk level to the offender in constructing the device. By talking to forensic bomb experts we must learn if making the bomb created any degree of danger to the bomber or if the risk level was low.

When we have a mobile offender with bombings occurring over a wide geographical area, motive is often the thorniest issue to resolve. The classification of the bomber initially may fall into one or more categories. It could be a criminal enterprise, a personal cause, a group cause, a psychologically disorganized individual, or a mix of these elements.

We know from some cases of extortion, arson, and product tampering that the offenders may be driven principally by a desire for power. Their otherwise drab and colorless lives seem more exciting if they can get this kind of reaction out of so many people, mobilize large police and fire and rescue resources, and generally have a public effect.

Traditional motives are clearly related to normal, though hideously exaggerated, emotions. Anger, hatred, and love are typical. Revenge or retaliation can be methods of acting out these feelings. In cases of extortion, product tampering, arson, and bombing, the motive is not always clear.

A criminal-enterprise bombing may be undertaken for material gain, such as insurance or inheritance. On November 1, 1955, twenty-three-year-old Jack Gilbert Graham drove his mother, Mrs. Daisie King, to the airport in Denver and put on her United Airlines Flight 629. Eleven minutes after takeoff, the DC-6 exploded in midair and thirty-nine passengers and five crew members plunged to their death. The cause of the explosion was a bomb planted by Graham in his mother’s suitcase. At the airport he had taken out several hefty policies on his mother’s life from insurance vending machines. Graham, who was convicted of first degree murder and executed in the Colorado gas chamber in 1957, had once commented to a neighbor, “I’d do anything for money.”

Under the heading of personal cause, we would include bombings that aren’t motivated by the quest for material gain and are not sanctioned by a group of, say, political terrorists or by some hate organization. It is the underlying emotional conflict that propels the bomber to act out his anger and/or frustration.

On December 16, 1989, in a suburb near Birmingham, Alabama, Mrs. Helen Vance was wrapping Christmas gifts when the mailman brought a package addressed to her husband, Federal Court of Appeals Judge Robert Vance. The bomb contained in this package exploded with such force that the judge was killed instantly.

Then, in a room of the Atlanta, Georgia, Federal Court of Appeals, an X-ray check intercepted a second bomb. A third device turned up in a Jacksonville, Florida, office of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In Savannah, Georgia, a fourth bomb went off, killing Robbie Robinson, a lawyer who had done legal work for the NAACP.

After seventeen federal judges across the Southeast received threats and another communique warned that more NAACP officials would be murdered, panic spread. _

Walter Moody, Jr., a brilliant and charming chameleon of a man was indicted and later convicted of homicide. Nearly seventeen years earlier, Moody had been one of seventy-four subjects arrested for bootlegging whiskey in Georgia. For years, Moody had complained to ATF Agent Chet Bryant about the perceived mishandling of the bootlegging case. Bryant later recalled that Moody’s wife, Hazel, was maimed in an explosion.

Moody targeted his victims because of the paranoid belief that he was somehow wronged by the judicial system. Moody’s “personal cause” was revenge.

A group cause, on the other hand, pertains to two or more people with a common ideology who sanction the act committed by one or more of its members.

On February 26, 1993, at eighteen minutes past noon, a massive bomb exploded in an underground parking garage beneath the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center near the tip of Manhattan. Of the 50,000 people in the 110-story towers, six individuals were killed and over a thousand sustained some injury.

Two days after the explosion, one of the ATF’s explosive experts found the remnants of a mediumsize van that evidently had been used to transport the explosives. Found on its chassis were the remains of a vehicle identification number, which allowed the van to be traced to a Ryder Truck Rental Company office in New Jersey. Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman, a blind radical Egyptian cleric, was directly linked to the bombing. Rahman, along with three conspirators, was charged and convicted.

The disorganized and sometimes mentally unstable bomber almost always acts alone. A disorganized bombing incident or site may be the work of a youthful offender, a subject under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or someone who lacks criminal experience and/or sophistication or mental stability. Consequently, disorganized bombers are much easier to identify.

They may also experience delusions and hallucinations, and they will take little care to hide or mask themselves. While we see this type of individual more frequently in other serious crimes, including murder, it is rare to see one in a bombing due to the technical experience level required to make a bomb effectively and safely.

The last category is a catch-all classification used when the motive is not clear. We speak of this category as “mixed.” An example of this type might be an abortion clinic bombing. Is this a group-cause crime perpetrated by an extreme pro-life organization? Or is it a personal-cause bombing for which one individual is responsible, whether or not he is also be part of a group?

If a motive cannot be clearly established, then proactive techniques might be used to try to flush out the bomber. The area of focus for these techniques should be within in the geographical area of the first bombing or cluster of bombings. Investigators focus on the very first case or first few cases because the offender can be linked directly to that area and because the subject is generally less criminally sophisticated at first and is not yet likely to have a well- defined modus operandi.

Let me say a few words about search-warrant considerations.

If you’ve gotten to the point where you have a potential suspect and are going for a search warrant, you should be looking for some specific things. Among them would be books on making bombs, possibly books or articles on political philosophy to support or justify intellectually his actions, scrapbooks or clippings of previous cases, and of course tools and materials to make the bombs.

If you’ve been accurate in your classification, you shouldn’t have too many surprises.

THE MANHUNT

The most expensive manhunt in United States history, ultimately costing upward of $50 million, began with a relatively insignificant event. On May 25, 1978, what appeared to be a lost package was found in a parking lot on the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Addressed to a professor of engineering at upstate New York’s Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the package had the return address of a professor from Northwestern University and so was forwarded to Northwestern to be returned to its presumed sender, Buckley Crist, a professor of material sciences. The explosion that injured Terry Marker, a police officer on the Northwestern campus the next day marked the beginning of the eighteen-year search for the mysterious bomber whose case the FBI would dub “Unabom.”

That first bomb, built of match heads and other wooden components held together in a simple wood box, gave little indication of the complexity of the devices that would follow. Police were left with no apparent motive, no witnesses, and no clues other than the remains of the bomb itself—that is, until another bomb exploded in the same area almost exactly a year later.

In the second incident, another member of the Northwestern University community was injured— this time a thirty-five-year-old graduate student of civil engineering. John G. Harris suffered minor cuts and bums when he picked up a curious-looking cigar box, taped shut, that he found in a common area in the school’s technological institute. Although shocking to the college community, the bombings were not yet big news outside the Chicago area. This was just one among many that occurred every year in the United States, and not a particularly noteworthy one on its own.

In November of that year, though, the stakes grew higher with the bomber’s next target: American Airlines Flight 444, in flight from Chicago to Dulles International Airport over the Virginia countryside outside of Washington, D.C. Although the bomb did not explode as intended, it caught fire in a mailbag in the cargo hold and forced an emergency landing. Twelve people on the plane had to be treated for smoke inhalation.

The bomber had moved beyond targeting one person at a time. He’d gone outside a university setting and was enlarging his base past the immediate Chicago area.

Tom Barrett and Chris Ronay, an FBI bomb expert who would go on to become chief of the Explosives Unit, focused on the airplane bomb’s improvised detonator and showed the evidence around to other expert to see if they felt this was related to the previous explosions. There was a consensus that they were. The detonator was nearly unique.

But federal explosives specialists who studied the device recognized that the construction of the bomb was more sophisticated than investigators had imagined the university bomber capable of—the bomb’s trigger was an altimeter, set to explode when pressure in the cabin reached a critical level.

The first two bombs at Northwestern—one placed in a handcrafted wooden box, the other in a cigar box—had earned the UNSUB the nickname “the Junkyard Bomber” at the FBI Crime Lab because the internal parts were constructed from leftover materials such as furniture pieces, plumbing pipes, and sink traps.

Seven months after the American Airlines incident, on June 10, 1980, another bomb was targeted at the airline industry, this time arriving at the Lake Forest, Illinois, residence of Percy Wood, the president of United Airlines. Wood suffered injuries on his hands, face, and thighs when a package bomb exploded in his suburban Chicago home. It was hidden inside Ice Brothers, a novel published by Arbor House, a company that used a tree leaf as its trademark. Given the name of his latest victim, the leaf trademark, and the construction of his bombs (usually largely fabricated from wood), investigators began to speculate that his message might be tied to an obsession with wood. Still, they were no closer to establishing a specific motive for the bomber’s attacks.

It was at this point that Tom Barrett called me. And it was at this point that the multiagency task force was assembled.

A number of traditional forensic people were working the case, so if I had anything to contribute, it would have to be in the area of the unknown bomber’s behavior.

Traditionally, police have used modus pperandi, or M.O., as their primary guide to serial-crime linkage. In other words, they study the method by which the crime was accomplished—the use of a particular weapon, a note used by a bank robber, a technique for disabling a rape victim—in determining whether a series of offenses was committed by the same individual or group of bad guys. But as we studied more and more serial offenders and developed our profiling methods, we came to realize that while M.O. was important, in certain types of crimes it wasn’t nearly as important as what I call “signature”—the unique aspect that was critical not so much to accomplish the crime as to satisfy the perpetrator emotionally. A sexual sadist, for example, might bind one victim with rope and take her home or use duct tape on another and place her in the trunk of his car, but his reason for abducting each of them is the same. Or he might use a whip on one and a pair of pliers on another, but in each case his signature is torture. He does what he has to do to acquire his victim, but what satisfies him emotionally is the torture and ultimate murder of that victim—his ability to manipulate, dominate, and control her. So while modus operand! is adaptable and evolutionary for a successful criminal, it’s something he’ll learn from and improve upon from crime to crime, whereas signature is relatively static. It’s a clear indication of motive and therefore, to my way of thinking, a much more reliable indicator of serial-crime linkage.

My feeling has always been that if you can get into a case fairly early in the series, after the signature has been established but while the M.O. is still in the working-out stage, you get your clearest insight into the UNSUB and your best chance of catching him.

Just as there is a behavioral signature to many sadistic and violent serial crimes, there is also a physical signature to such hand-art crimes as bombmaking.

By the time I got involved in the Unabomber case, the FBI lab in Washington had already established distinctive links among the four cases. According to our experts, whom I personally believe to be the best in the world, all four bombs displayed a similar signature, an indication of the type of flair the maker obviously found emotionally satisfying: there was a high degree of handcrafting of elements that could have easily been bought in a hardware store; the experts also thought they had found a written signature of sorts on the bombs’ bases: the initials “F.C.” Immediately I thought of George Metesky’s “F.P.” and wondered if this bomber was a student of history.

In this case, unlike in the Metesky case, the problem was that there was no communication from UNSUB to victim, no clear or obvious relationship between the subject and any of the victims, and no apparent motive. Other than the physical forensic connections established by our labs, the only thing that stood out was that the first two targets had been LWiversity-related and the second two had been Airline-related, hence the FBI case code: Unabom.

The first task was to come up with a motive for the bombings. There was a combination of specific and nonspecific targets—that is, we had two bombs intended for particular individuals, and two that were essentially left for anyone to find. With no clear common denominator, how would we classify these crimes? Group? Personal Cause? What? And why had the subject shifted from universities to airlines?

I wondered if the subject had experienced some precipitating event that prompted him to switch gears. Had he been traveling and felt he was slighted in some way by people working for the airlines? Since he had changed his focus like this, I thought perhaps the crime had become a personal cause. He was already motivated to cause harm to nonspecific victims; if he perceived he’d been mistreated by some company, individual, or group, that feeling could have led him to narrow or change his target.

On the federal, state, and local level, the United States has more than 17,000 separate law enforcement agencies. So as often happens with major cases, something of a turf war was brewing with Unabom. In addition to the FBI and the various police departments in places where the crimes had taken place, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the Office of the Postal Inspector also had legitimate interests. The multiagency task force was established to include all the key players.

In analyzing a crime from a behavioral perspective, we try to figure out what actually happened between the attacker and the victim. For example, my colleague Roy Hazelwood has shown how, in rape cases, the attacker’s acts have a lot to do with how the victim reacts. This is not to say we can prescribe a specific way a victim should behave if she’s unfortunate enough to be involved in a rape attempt, since there are various types of rapists. But if we can get a good interview with the victim afterward, we’re going to know a hell of a lot about her attacker.

This applies across the board. When we analyze a murder, we try to find out as much about the victim as we possibly can. Victimology, as we call it, is as important as any other single aspect of our analysis. So in bombings, as in other more up-front and direct crimes, we needed to know as much about the victims as we did about the bombs. As background, I looked into what was going on in the Chicago area around that time—in the news generally and in politics, industry, academia, and airlines.

The early bombs were fairly unsophisticated but very carefully made. The risk level to the bomb-maker was low—that is, the devices were unlikely to blow up during construction. Likewise, the early bombs were not as deadly as the later ones turned out to be. They could blow your hands off if they exploded at close range, but they probably wouldn’t kill you.

At that time, bombing was a relatively popular crime, although I hadn’t been involved in many of the investigations. The FBI and ATF lab work, though, clearly differentiated F.C.’s work from all the others.

Some of the original suspects in the Chicago area were a group of college students who belonged to a Dungeons & Dragons club. But when they were brought in to the FBI office for questioning, it was clear they weren’t going to pan out. Drawing on my experience with related types of crimes, I felt certain the bomber would be a lone subject. Like George Metesky and most other cowardly “distance crime” offenders, he wouldn’t be comfortable around other people, certainly not to the extent that he would trust them.

Our research has shown that various types of crimes tend to begin at various ages. Therefore, we generally take age twenty-five as our starting point and add or subtract years depending on the details and specifics of the case. Based on the level of sophistication, I profiled a white male in his late twenties to early thirties. I thought he would be white because of the types of targets: airlines and universities. Culturally, I thought a black, Asian, or Hispanic individual would have other targets for his rage. And I thought the bomber was a male because female bombers were extremely rare and when they surfaced at all, they would typically target loved ones—or, should I say, former loved ones.

Like Metesky, he wouldn’t be antisocial. Rather, he’d be asocial. He’d be the type of person who might hold a night job because he felt more comfortable when there weren’t a lot of people around. It was unlikely he belonged to any sort of organized political group or movement, but if he did, he would be the guy in the background, not a demonstrator type. He’d be a secondary player or a gofer, sending out the letters or writing the flyers. He would also keep diaries, detailed notes, obsessive lists. He would trust only himself, so he would maintain an active self-dialogue.

For this reason, I didn’t expect him to have a criminal record. He would, quite the contrary, be very careful to stay on the right side of the law at all times.

I visualized this subject as an obsessive-compulsive, a very rigid personality. As with most bomber and assassin types, the elements of his everyday life, such as eating habits and personal hygiene, would be in complete disarray. But what is really important to him would be immaculately kept. His library would be well organized. His garage and/or workshop would be kept under lock and key. All of his tools would have a specific, carefully labeled place. His bomb work area would be in perfect order, matching his rigid, ritualistic style. When the four NYPD detectives drove up to Connecticut to arrest George Metesky, for example, he proudly showed them his well-ordered workshop.

When an individual commits his first violent crime, there is almost always a “trigger.” Something happens, some stress, that makes the person lash out, often against people he doesn’t even know. There can be many different kinds of triggers, but the ones we’ve uncovered most often in our interviews with convicted offenders and our study of cases are loss of a job and the end of a relationship with a significant other person. Sometimes those two things will come together, as they did in a case my colleague Jud Ray handled in Anchorage, Alaska. In that one, an angry and emotionally volatile young man was jilted by his girlfriend, who immediately took up with his boss. The boss then fired him to be rid of the interference. Rocked by this double whammy, the young man brutally killed his aunt and two young girl cousins, whose stable and happy life he resented.

We had no real idea what the Unabomber’s initial trigger might have been, but we were sure there was something.

As I’ve indicated, I believe a subject’s earliest crimes are the most telling. He’s fulfilling himself emotionally, but he has not yet perfected himself or his crime. If you understand the early crimes, you can study the subject in process. Therefore, despite the relative crudeness of the bombs, I felt we were dealing with someone with a strong connection to the academic world, either to Northwestern or the University of Illinois at Chicago, or both. Maybe he was an instructor who’d been turned down for tenure. Maybe he was an “ABD”—All But Dissertation—a frustrated, long-suffering grad student who just couldn’t get it together to finish. Maybe he had some other type of grudge. But I was relatively certain this wasn’t a blue-collar type. This guy was well educated and intellectual, with a strong grounding in the sciences.

There was some talk in police circles that our UNSUB was probably a Vietnam veteran and that he learned his bomb-making skills in the service. But from what I understood of his devices, it didn’t appear that he would have needed a superior skill level to construct them. An intelligent person with some science background, as I expected him to be, could have gotten all he needed out of such readily available publications as The Anarchist’s Cookbook, for example. ,

This is not to say I originally pegged the bomber as brilliant. Initially I just figured him to be of above average IQ. The longer his crime spree went on, however, the more respect I gained for his intelligence.

There is a danger in investing too much significance in the initials F.C. It was highly unlikely they stood for a name, so expending manpower combing records looking for names that matched up would be a huge waste. The letters meant something only to the user. Maybe they stood for “Fuck Computers” or something like that. Computers were a sufficiently universal symbol of our age that someone who felt on the outs with society enough to want to blow things up might possibly focus on the computer as the source of all ills. But that was just a guess.

Sometimes you have to hold something three feet from your face instead of three inches. When I interviewed serial killer David Berkowitz, the Son of Sam, in Attica, I asked him the significance of the wavy and curly lines at the bottom of some of his letters. Several psychiatrists had speculated that they might represent female breasts, specifically the breasts of his biological mother, who gave him up for adoption in infancy and whom he later tracked down. But he simply smiled and said, “I just liked the way it looked.”

If the UNSUB had a car, it would be well maintained, given his level of technical expertise, but it would be an older, unflashy type of vehicle. This person would not have the money for a new car.

I thought the subject would be single and would have severe difficulty maintaining relationships with both men and women. It was possible that later in life, in his forties or fifties, he could have a relationship with a woman and even marry, but the marriage would be one of convenience. His wife or girlfriend would have to be someone who would always obey him if, for instance, he told her always to stay out of a particular room in the house. This pattern is fairly common. We had one serial killer who kept body parts from his victims in a large freezer in the garage. When his submissive and unknowing wife wanted a particular cut of meat to prepare for dinner, she had to ask him to get it for her. While she might have suspected something from her husband’s secretiveness, she would never have challenged him on it.

All in all, though, I would expect this guy to remain single throughout his life.

The offender would be similar in many ways to arsonists I had studied. Like other types of criminals, there is a range of arsonists, from the nuisance type to someone intent on hurting people. Bombing is also like arson in the sense that most of the evidence goes up in flames, making analysis difficult.

Still, from the victimology, I could see no apparent motive or common denominator to this bomber’s crimes.

I thought a good first step would be to go to newspapers in the Chicago area, including college papers, to look for letter writers. Before the subject decided upon his course of criminal action, he would likely have signed his real name to his letters, since he wouldn’t yet have had anything to hide.

In focusing on the early crimes, I noted that the first incident took place around Memorial Day. Although not apparently meaningful to others, this day could hold some significance to him. ,

Going public with this profile of the guy, focusing more on pre- and post-offense behavior than on specifics such as age can be an important investigative technique. People don’t just wake up one morning and say, “I'm going to be a bomber.’’ An arsonist might do this, although he probably wouldn’t. But while anyone can light a match, bombing is something one has to learn and practice first. There are earlier steps that someone close—a parent, a teacher, a neighbor—would recognize if, for example, the kid next door has been setting nuisance fires or mistreating the neighborhood cats.

In 1980, I’d only been at this game for about three years and the FBI wasn’t ready for a full-court press. In an organization as large and complex as ours, “analysis paralysis” can easily set in if you have to explain your methods or get permissions to try proactive techniques such as working with the media or using a decoy. This was several years before the Wayne Williams-Atlanta Child Murder case really spotlighted our proactive techniques, giving them national attention and public authentification.

There was also the feeling in a lot of Bureau circles that since we couldn’t use a behavioral profile as evidence in court, what good was it? Why bother?

This tussle between the operational people and the behavioral people will probably always be ongoing, though I like to think it can be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. Years later, for instance, my people and I were deeply frustrated by the events at Ruby Ridge and Waco, where we felt our message based on our knowledge of profiling either wasn’t being listened to or wasn’t being understood. But it doesn’t have to be this way. In my career I’ve experienced many examples of terrific and productive cooperation between us and the front-line police troops and forensic guys.

Finally, I felt certain the Unabom crimes would continue to grow in sophistication and dangerousness as the UNSUB perfected his craft. There was a good chance we’d start to see some social or political justification for his violence and an even better chance that be would move his operations farther outside the Chicago area.

On October 8, 1981, sixteen months after the blast that injured Percy Wood, another bomb was found by a maintenance worker in a business classroom at the University of Utah at Salt Lake City. A bomb squad got to it and was able to diffuse it before it went off. When it was analyzed in the lab, the report came back: Unabomber had struck again. And he had moved outside the Chicago area. Still, we had little more to go on than we’d had the previous year.

The next mysterious wooden box was received May 5, 1982, addressed to Professor Patrick Fischer, a computer scientist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Tracing the path to the intended victim of this bomb was a little more complicated, though. The package was addressed to Fischer’s previous place of work at Pennsylvania State University, a position he’d left two years earlier. Someone had forwarded it from Pennsylvania to Nashville. But how the package even got as far as the Pennsylvania address was something of a mystery, since the bomber had used canceled stamps when he mailed it in Provo, Utah. It appeared that this bomb was intended to work like the very first bomb, the one that injured the Northwestern campus security officer: the intended victim may have been the person named in the return address. In this case, that was Brigham Young University electrical engineering professor LeRoy Beamson. Although the link with Beamson was no more apparent than with Fischer or any of the other recipients thus far, we were interested to learn that Bearnson’s middle name was Wood.

But the package never made it “back” to Beamson. Instead, Fischer’s secretary, Janet Smith, was injured and had to be treated for lacerations when the bomb inside the parcel exploded.

Only a couple of months later, on July 2, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley became the victim of the next bomb. A professor of engineering and applied physics, Diogenes Angelakos, went to move a package, described as a “green container with wires hanging out of it,” or perhaps a can of some kind left in the faculty lounge.

It was relatively early in the morning, around eight o’clock, and Angelakos thought the container might have been left behind by construction workers or by a student. Another nonspecific target of the Una- bomber, Angelakos suffered severe bums on his right hand when the small pipe bomb exploded.