John Moretta

Down on “The Technicolor Farm” of Summertown, Tennessee

The Hippie Era’s Most Eclectic and Visionary Commune

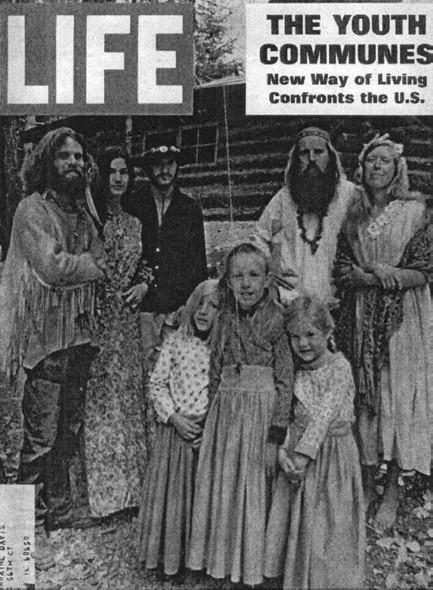

In the summer of 1969, Life magazine featured a photograph of a family of hippies, gathered around a teepee before majestic tall firs and broad leaf oaks of the southern Willamette Valley of western Oregon. The caption below the photograph read “The Commune Comes to America,” and within a five-page story heralded the arrival of the communes, implying that such pastoral communities were a recent phenomenon in American culture, having bloomed from the hippie movement. Everything about the story reflected the mainstream media’s stereotyping of the counterculture, caricaturing country hippies as the most extreme type of “fanatics” to be approached with caution, especially if sighted in their remote, isolated rural enclaves. No exposé of a hippie commune would have been complete without the gratuitous photos of hippies meditating as the sun set, or nude-but-happy hippie children frolicking in woods or meadows, or of hippie women wearing bright colors or perhaps nothing at all, preparing a typical hippie macrobiotic meal of rice, vegetables, and fruit. Even commune members’ names were strangely “un-American”—Twig, Ama, and Evening Star— and their language equally unfamiliar if not unintelligible: “The energy we perceive within ourselves is beyond electric; it is atomic; it is bliss.” Like the majority of their counterparts throughout the nation, this group of communards revealed as little as possible about their way of life, wanting to stay out of the media limelight. They referred to their commune as “The Family” and described their habitat as “somewhere in the woods.” This particular assortment of new-age pioneers actually called themselves the Family of Mystic Arts.[1]

Late 1960s and early 1970s hippie communards became “builders of the dawn,” developing their alternative societies in a pastoral setting and referring to their new hip enclaves as communes, cooperatives, collectives, or communities, depending upon which name most aptly identified the member’s purpose for establishing their particular alternative existence; living and working arrangements were forever fluid. Such a varied assortment made defining communes difficult as one Oregon communard noted at the time.

Each commune is different. There are communes that live on brown rice, and communes that have big gardens, and communes that get white bread and frozen vegetables at the grocery store. There are communes with no schedule whatsoever (an no clocks); there is at least one commune where the entire day is divided into sections by bells, and each person states, at a planning meeting at 7 a.m. each morning, what work he intends to do that day. There are communes centered around a particular piece of land, like us, or travelling communes like the Hog Farm, or communes centered around a music trip or a political trip, like many of the city communes. This diversity raised certain questions. A piece of land that is simply thrown open to anyone who wants to live there, or a place where each family lives entirely in its own house but the land is owned jointly; shall we call these places “communes” or not?[2]

It has been estimated that by 1970 there were 2,000 rural communes and 5,000 urban counterparts, home for approximately two to three million hippies. Reliable statistics are difficult to gather because most communards wanted as little contact with mainstream society as was possible, and to reporters or social scientists who visited, they were reluctant to reveal much about themselves or their lifestyle choice.[3]

Inherent in hippie social thought was the pursuit of an Arcadia, felt by many seekers to have been lost with the passage of time. This quest culminated in a return to a pre-capitalist attachment to the land by moving to the country or the desert, of getting away from the city, and by extension escaping modernity. Journalist William Hedgepath maintained there was “a serious mass-level motive behind this migration,” and that “those communes lying out there somewhere in the fierce, snaky reaches of the wilderness” were “by no means hideouts” or “cop-outs from the world. Rather, they are outposts, testing grounds, selfexperimental laboratories, starting points for [a]... social life that more rightly fits the human form.”[4]

As reflected in Hedgepath’s observations, joining a commune represented a deliberate, wholesale rejection of mainstream society and its attendant values and norms. As Bill Dodd of the San Francisco Oracle opined,

Everywhere it seems people, even those far removed from such a way of life, are at odds with the regimentation, alienation from their society and from themselves, and the simple sheer drudgery of their lives. Equally it seems that if means were readily available to drop out of this vicious cycle there would be no one who would not do so.[5]

Genuine bonding and solicitude for each individual’s well-being would define the new societal order; one hippie writer declared that communes were “a way to bring our people [hippies] closer together—closer to social freedom.”[6] Time reporter Robert F. Jones maintained that those hippies who had moved to a rural commune “come closest to realizing the ideal of complete alienation.” As far as Jones was concerned, the rest simply “talk continuously and rapturously about the virtues of dropping out, but few, if any manage to sever all ties with straight society.” Whether they panhandled or sold dope, or simply “turned on in doorways,” they were “still linked—however remotely—to the macro-economy.”[7]

Many of the 1960s communes were founded by disgruntled urban hipsters; “Haight-Ashbury and New York’s East Village turned loose on the land.”[8] Some of the more famous ones were established by hippies leaving their original metropolitan enclaves, many of which by the late 1960s had deteriorated into cesspools of hard drugs, violent street crime, and increasing establishment repression of dissident lifestyles. The economic recession and conservative backlash of the late 1960s and early 1970s dashed hippie “expectations... that American society could be radically altered, whether by politics, revolution, or alchemy....” As a result, rural communal living became the favored new “countercultural mode,” with the hope that the new forms of human relationships that had not come to fruition in the cities, could be better realized.[9]

As their old urban haunts decayed, many “community-oriented hippies left the city” for the countryside where they hoped to recreate the hip vision— “to routinize hippiedom.”[10] As William Hedgepath noted at the time, the explosion of country communes in the post-Summer of Love years reflected “the fact that these young people’s mass readjustment to their parents’ world simply did not take place,” despite all the media’s “epitaphs” that such a shift back had occurred. Instead, hippies found “another, quieter alternative”— rural communes—“of every imaginable genre... silently cropping out of the earth by the hundreds,” and prompting “alienated young folk to set off in a collective exodus once again.”[11]

Dope also played an important role in the rise of rural communes; acid-heads and other dope-using hipsters bonded the moment they started passing the joint around the circle or tripped together on acid. Since dope was illegal hippie users became outlaws and shared the goal of staying out of jail. They believed their chances of avoiding that fate increased if they stuck together and remained out of the law’s sight (and grasp) in the country, and in fact, most rural communes were isolated enough from mainstream civilization that they were safe from the law in dope cultivation and usage. No doubt the search for remote areas in which to grow marijuana motivated more than a few hippies “Going up the Country,” as Canned Heat urged fellow freaks to do.[12]

The early communes attracted the more genuine, purposeful counter-culturists; true seekers of a New Age in pastoral miniature. As one member of the movement reflected, “Given both our despair over the social injustices endemic to our political and economic systems, and our optimism about our own ability to come together and create better environments in which to live, it now seems inevitable that so many of us would try to form communes in the late sixties and early seventies.”[13] Communal seekers wanted to feel the flow of the seasons, to grow things, to walk naked; to breathe-in, to soak up, to envelop themselves in as much nature as they possibly could; to affirm “Life,” a word they often used that encompassed everything they valued. Indeed, as one Northwest communard told Harper’s reporter Sara Davidson, who spent the fall of 1969 visiting intentional communities in California, Oregon, and Washington and interviewing their inhabitants, “I like it here [at Tolstoy/Freedom Farm in Davenport, Washington established in 1963 by Huw Williams and one of the first to embrace open land] because I can stand nude on my porch and yell f—! Also, I think I like it here because I’m fat, and there aren’t many mirrors around. Clothes don’t matter and people don’t judge you by your appearance like they do out there [in mainstream society].”[14]

Apocalyptic visions of the “end of days” for urban/industrial society compelled many to seek refuge in rural areas. Many hippies determined that the United States had finally reached a point of no return after decades of greedy excess and abuse of the nation’s natural environment. The warning signs of the impending collapse were all around by the late 1960s— smog alerts, water shortages, pesticide scares, power outages, traffic snarls, overcrowding—clear indicators that the urban scene soon would be deadly to body and soul. To Lew Welch it was “quite clear that gluttony, greed, lack of compassion” was fast destroying

this generous and undemanding Planet. We face great holocausts, terrible catastrophes, all American cities burned from within and without. And there will be signs. We will know when to slip away [to the country] and let these murderous fools rip themselves to pieces.[15]

Once hippies had staked out their “colively [communal] retreats” in the country, it was imperative to Welch that they “learn the berries, the nuts the fruit, the small animals and plants. Learn water,” so that when the day comes when all the “good men and women” who had taken refuge “in the mountains, on the beaches, in all the neglected beautiful places,” gather together, “we will be prepared to go back to ghostly cities and set them right, at last.”[16] A Northwest communard agreed with Welch, announcing, “Technology can’t feed the world,” and thus if “you don’t want to starve to death, better know how to plot a garden.”[17] Despite their popular image at the time as weird, naive nature freaks, the hippies’ environmental call to arms now seems visionary and cannot be dismissed as the silly notions of a bunch of “long-haired leaping gnomes.”

Contrary to popular myth, few hip communards were drug and sex-crazed hippies or miscreants. Although some communes did become sanctuaries for the casualties of psychedelia or its sickies, vagabonds, and other unsavory characters who took advantage of hippie gentle hospitality, the majority remained from start to finish, the home for mostly young, white affluent Americans, many of whom had a college education. As William Hedgepath observed, these new “young migrants” were “not just displaced veteran hip gypsies who set forth on this second wave” of hippiedom. Joining them in this new exodus were “thousands more hippie-symps and until-just-recently straight kids who were finally sensing the Angst of living in official America,” and most important they were “more sophisticated and a damn sight more serious about why they were leaving and what they were headed for.”[18] Regardless of who they were, or what they were searching for in communal living, “they all had in common the highest human aspiration: to be free.”[19]

One of the most emblematic, intriguing, and enduring was The Farm “collective” of Summertown, Tennessee founded in 1971 by one of the era’s more beguiling and charismatic gurus, Stephen Gaskin, “Moses in Blue Jeans.” Gaskin refused to “let anybody call it a commune because people who live on communes are communists. We were a collective, which is scary enough for some people.” Gaskin also made it clear that although he and his followers had established a collective, they were not Marxists: “I think Marx talked about the problem pretty well but what he said to do about it didn’t work very well because almost everybody who’s tried it has slid into some kind of dictatorship. He even uses that phrase, ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat.’” Although Gaskin passed away in July 2014, the Farm still exists, home for a mix of about 200 diehard old and new “Farmies,” and thus Gaskin’s vision and legacy has endured, albeit in a modified form. Some would even go so far as to claim that the Farm is flourishing, having become in its forty-six year history, not only an influential force in local Tennessee politics but also a font of much technological and social innovation, producing the first Doppler fetal pulse detector, a portable ionizing radiation detector, and passive solar space-heating technology. The Farm has long outlasted the majority of its countercultural peers while fulfilling Gaskin’s initial call to “change the world” by spreading good works from Guatemala (where Farmies built 1,200 houses for 1976 earthquake victims), to the South Bronx and to Indian reservations in upstate New York (where Farmies provided free ambulance services); to Liberia (an agricultural training program); and to Belize, where Farmies initiated a free lunch program. Farmies were among some of the first responders to arrive in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Big Easy in August 2005. From its inception the Farm was never intended to be just an escape from mainstream culture as Gaskin made social outreach and activism his collective’s raison d’etre. For such endeavors Gaskin and his compatriots formed Plenty International, which won the other Nobel Prize in 1980, the Right Livelihood Award, presented by the Swedish Parliament in recognition of the Farmies’ charitable efforts in Guatemala, Washington D.C., and the South Bronx. In addition to its eleemosynary activities, the Farm also has a printing and publishing company, a small electronics firm, a Mayan goods trading company, a woodworking shop, and produces a host of vegetarian food products, most notably one of its first staples, sorghum molasses. Gaskin’s fourth wife, Ina May Middleton almost single-handedly put the Farm on the international map as a center for midwifery, and her book on the subject, Spiritual Midwifery, has sold more than 600,000 copies. According to one of the Farm’s first communards, Albert Bates, “We’re probably the single largest producer of tempeh [a food made from fermented soybeans] in the world. And of course, there’s the Dye Works. Tie-dyes [were] a kind of traditional craft among hippies, and we’ve carried it to its peak.”[20]

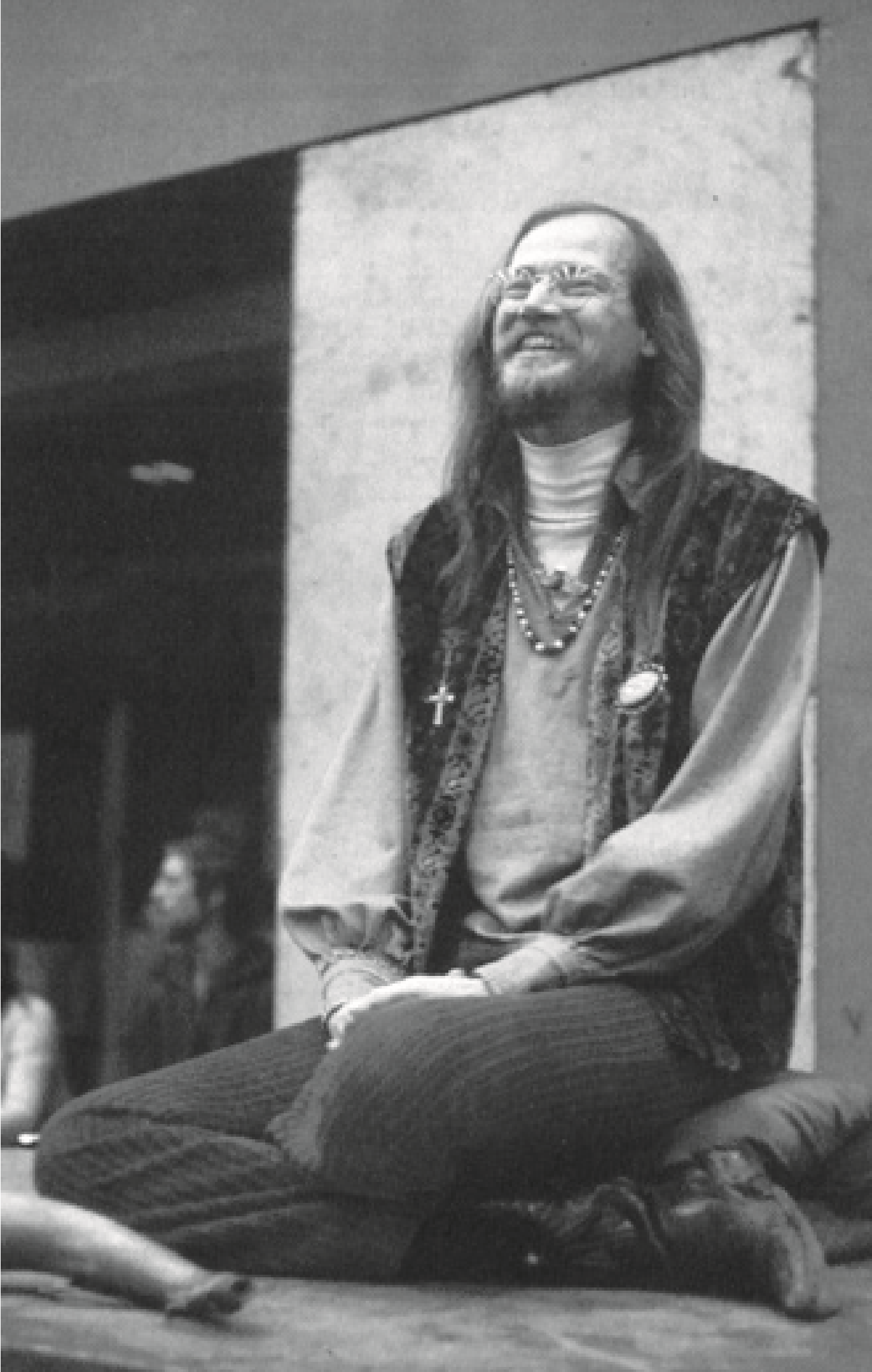

The often controversial figure at the center of both the Farm’s outstanding successes and equally pronounced failures was the enterprise’s founder, Stephen Gaskin. Born in Denver, Colorado, in 1935, Gaskin lied about his age (he was seventeen at the time), joined the Marine Corps during the Korean War, and saw combat in that conflict. Mustered out of service at war’s end, Gaskin returned to the United States and attended junior college but eventually dropped out, drank heavily, and ran coffee houses in North Beach, San Francisco’s Beat enclave. Although embracing much of the Beat ethos and aesthetic, Gaskin nonetheless returned to school, eventually earning a BA and an MA in English and Language Arts at San Francisco State University, where he became a teaching assistant for the noted linguist and semanticist, S.I. Hayakawa. Upon completing his MA, the university offered Gaskin the position of instructor, teaching not only basic composition and creative writing classes but also the opportunity to present courses on subjects like witchcraft and others with descriptions such as “Einstein, Magic, and God.” Heavily influenced by Beat literature and poetry, particularly by the Beats’ emphasis on stream of consciousness, Gaskin encouraged his rhetoric students to “just write what they felt. Forget about the formal stuff like spelling and punctuation.” Gaskin’s unorthodox approach reflected the trend among many 1960s college professors who embraced much of the hip ethos, hoping their “sensitivity” would allow them to better understand the “new consciousness” emerging in many of their students, who increasingly were demanding more open, creative, and personal learning environments. No doubt Gaskin’s eschewing of academic formalism disturbed many of his more traditional colleagues. However it was his “Monday Night Class” or “tripping instructions,” for which Gaskin gained local and then national notoriety. As one of Gaskin’s original followers, John Coate, noted, “The holy-man scene was a big part of the action in the late sixties, and in San Francisco the guy who worked the local beat was Steve Gaskin.” Gaskin’s first class held in the fall of 1966 on the SFSU campus, had only six students; by the fall of 1970, as many as 2,000 true believers regularly showed to hear Gaskin “rap” about his brand of hip cosmic spirituality, an interesting amalgam of Buddhism, Christianity, Tantric thought, and the psychedelic ruminations of Aldous Huxley, believing in telepathy, loving your enemy, and chanting “om” to cleanse away “bad vibes.” Gaskin’s affiliation with SFSU ended in 1967: “I didn’t get fired; I just got too weird to get rehired.” By that time he was holding his classes at rock entrepreneur Chet Helms’s famous dance hall, The Family Dog. Gaskin and his students “talked about what was the most important thing in the world we could talk about right then. We talked about God, we talked about cannabis, love, sex and marriage, death, and religion, non-violence, telepathy, subconscious, and enlightenment.” For one regular attendee, the Monday Night Class “was really about religion and the psychedelic drug-inspired, long-overdue spiritual reawakening which was then just beginning to stretch, come alive, and sweep across our jaded, materialistic modern world.” Gaskin believed his attraction was his “ability to talk intelligently while stoned for longer than most people.” However, for many of his followers, Gaskin was no longer “just the teacher of a class.” He had become “a Teacher as in your guru.” Gaskin embraced his new accolade, declaring, “I started out teaching people how to trip. Then I found out life was a trip. Then I started teaching people how to live.” Perhaps most revealing Gaskin reviled those gurus who charged money for their “wisdom” or “enlightenment,” considering such individuals to be “fakirs because spiritual teaching is for free or it ain’t real.” Interestingly, neither the mainstream nor underground press covered much of Gaskin’s Monday Night Class popularity, satisfied to “devote whole pages of their papers to the false prophets of the day: the warped and twisted prophets who said that The Answer was ever more exotic mixtures of reality-altering chemicals.”[21]

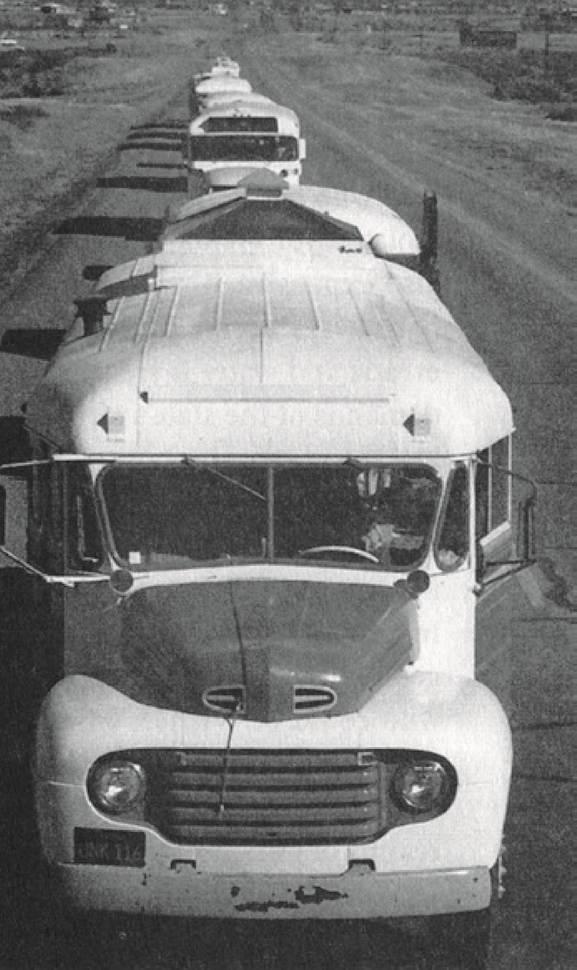

Gaskin’s charismatic youth-appeal got the attention of the progressive American Academy of Religion, who hired him to travel about the country preaching his gospel at local churches and colleges. Joining Gaskin on his speaking junket across forty-two states were about 250 of his “students,” traveling in thirty old buses. Gaskin and company were on the road for four months and as they traveled about “the more people there were who joined the caravan. Pretty soon there were three or four hundred of us and the police were meeting us every time we crossed a state line.”[22]

For many hippies Gaskin’s emergence represented yet another manifestation of what some referred to as “The Prankster/Millbrook dichotomy.” This split in the movement forced many hippies to have to decide which of the two hip trips they would follow: the Ken Kesey/ Merry Prankster/Grateful Dead approach to life or the “Tim Leary, Richard Alpert, Stephen [Gaskin], yoga and natural foods” way of being. For John Coate, the Kessey/ Prankster/Dead style “was doing acid on the streets and learning to be tough and glib and fast on your feet. Looking for an edge.” For Coate, the Dead’s music also reflected a similar “wild loose style,” as the band “would establish eye contact with individuals and play to them until they got them off. They were doing a lot more than playing music.” Most important to Coate, there were “no leaders and teachers.” At the other end of the hip spectrum “you have Leary and Alpert tucked away at this huge mansion in Millbrook, NY, tripping, getting quiet and still, everything inner-reaching and working with the whole Eastern religion aspect where you keep yourself high and together with meditation, or stillness, or certain diets or yoga. Structure, organization, method, technique, centering.” Gaskin had embraced this approach to life as well as he spoke “about selfdiscipline and creating good karma, and paying attention to being truthful and correct.” By 1970, many hippies, having burned-out from too much acid-tripping a-la-the Merry Pranksters, but still wanting to personally keep the hip vision alive, were ready to slow down and become more “centered” with a Zen-Buddha purposefulness and engagement advocated by gurus such as Gaskin. Equally important was Coate’s acceptance of Gaskin’s leadership. For John Coate, Gaskin’s message “made sense” to him and thus he became one of Gaskin’s most devoted disciples and Farmies for several years.[23] Matthew McClure agreed with his fellow Farmie that “the kind of people who started the Farm experiment” had emerged out of their sixties drug experiences with an awareness “of the vibrations and other realms of existence besides the material plain. … We’d had some kind of spiritual realization that we were all One and that peace and love were obvious untried answers to the problems facing our society. Those were the kinds of people who followed Stephen to Tennessee.” Walter Rabideau was even more convinced that psychedelic drugs were the key to the Farm’s founding and main reason why such an eclectic group of individuals “mixed in together. The reason why they were all there [on the Farm] was that they all took psychedelic drugs. If that hadn’t happened, the Farm wouldn’t have been there.”[24]

Rabideau also believed that he and his fellow Farmies represented that segment of 1960s alienated youth who had “completely lost faith in America, the whole straight society and everything else to do something like the farm.” Because “everything was totally f—d,” Rabideau believed the Farm reflected starting “absolutely from scratch with a piece of bare dirt and build everything, including your culture, out of whole cloth. And you wouldn’t do that unless you just had a totally apocalyptic vision brought on by the war in Vietnam and lots of acid. And that’s an unusual combination.”[25]

Not only had the majority of future Farmies reached the level of “consciousness” essential for creating an alternative rural lifestyle, but they were also overwhelming white, middle class, and educated, many with college degrees. As was true throughout the hippie movement in general, and specifically for the back-to-the land/communal phase, few African Americans found either manifestation of rebellion against, or rejection of, white hegemonic bourgeois culture to be very appealing or effective. Few African Americans had joined the 1960s hip parade, finding little they could relate to in the hippie counterculture. Like almost everything else related to the hippies at the time, the majority of African Americans, especially inner city blacks, saw communes as just another incarnation of bored, spoiled, and crazy white people temporarily playing at being poor, and voluntary poverty, egalitarian or not, had little attraction among late 1960s and early 1970s urban black Americans. Neither did trying to eke out a living by working the land, a painful reminder for many African Americans of their ancestors’ harsh and desperate lives as Southern sharecroppers or tenant farmers, or worse, plantation slaves. Nonetheless, true to the hip creed of inclusiveness and egalitarianism, Gaskin welcomed all individuals to the Farm as long as they were willing to work toward the common goal of helping to create a self-sustaining rural, agrarian alternative to the mainstream macro capitalist economy. As far as Gaskin was concerned, “Within the community a man was neither black, tan or white but just another brother.” As the Farm’s chronicler Douglas Stevenson, has observed, “Throughout The Farm community’s history, a few people of color have made The Farm their home for some period of time, but for numerous reasons, they have chosen to move on. Consequently the overall population remains a mix of predominantly [white] Western European ethnicities.”[26]

Upon their return to San Francisco in January 1971, it became readily apparent to all who had made the pilgrimage of 6,000 miles that all wanted to “stay in community.” All felt “stronger, more tied together,” and that

we could no longer just separate and go back to our separate apartments and our separate lives. So we thought back to the parts of the country we’d especially liked on our tour and Stephen said “Let’s go to Tennessee and get a farm,” and we all said, “Yeah, let’s go to Tennessee and get a farm.”

For Gaskin the decision to go to Tennessee was simple: “We can get it on with the dirt.”[27] Also motivating Gaskin and his compatriots was the sad fact that by the early 1970s their beloved Haight-Ashbury, like so many of the hippies’ original urban enclaves and the concomitant hip scene that they had so fully embraced, had degenerated into cesspools of crime, hard drugs, and violence. The Haight had “gone decadent,” Gaskin recalled years later. “We started seeing guys in long dark overcoats and brimmed hats who were heroin people. We started seeing meth—that was skinny guys sleeping in doorways— you could tell the meth. And we were into natural foods and like that.”[28]

Thus in the fall of 1971, some 280 devoted followers, traveling in roughly eighty buses, trucks, and vans trekked to Tennessee. Gaskin’s message was simple and direct: he and his followers were out to save the world, which to Gaskin and his acolytes ultimately meant establishing a spiritually-based commune that would become a new “City Upon a Hill;” a shining example of how to live off the land without endangering or destroying nature and wildlife, a much different back-to-the-land refuge than most of its contemporaries. For that purpose Gaskin and his followers purchased 1,700 acres of land for $70 an acre in one of the poorest counties in Tennessee, Lewis, about sixty miles southwest of Nashville. There they established The Farm and became “voluntary peasants.” Why the upper South, a region where the majority of citizens hardly possessed warm and fuzzy feelings toward hippies, an area of Tennessee only thirty-five miles from Pulaski, birthplace of the KKK? According to Gaskin, as he and his parade of disciples sojourned across forty-two states, “We found out a lot of stuff. We found the country was not as crazy in the middle as it was on the edges.” The locals became friendlier toward the “tie-dyed Amish” as they were dubbed, after overcoming their fears that “we were the Manson family. Amazingly we found several of the local men helping to cut an opening in the barbed wire and leading a group of longhairs into the trees.[29]

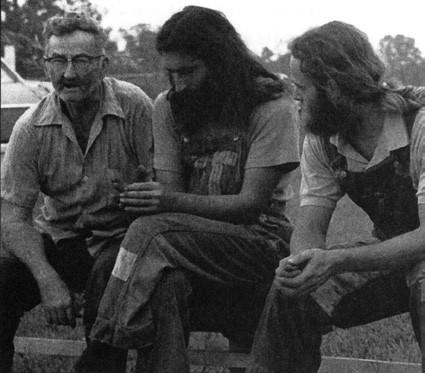

From the moment Gaskin and his companions arrived they knew, “These 60 and 70-year old farmers” would be “priceless to us. They know how to build everything and fix everything and grow everything.” Over time Gaskin and the Farmies

made friends with them and hung around them because we wanted to learn the things they knew. And this really turned them on. They would say “I didn’t know anybody wanted to learn this old stuff anymore.” And we’d say, “Yeah man. How do you do it?” You can’t jive anybody who’s teaching you how to run a tractor. It’s something to watch a cat who was once a Hell’s Angel being taught to run a tractor by an old man and being respectful to that old farmer.[30]

One such individual who “took a liking” to the Farmies was Homer Sanders, with whom “we collaborated on a saw mill and other projects.” As John Coate further observed, Sanders

didn’t have any teeth and only half of his tongue. It took real training to be able to understand the jokes he constantly told. He knew how to do everything involved with living on that land. A great guy; a living folk hero and genuine moonshiner who had fought it out with every revenue agent in the area.

For several years Sanders was among only a handful of locals who were willing to accept and help “the tie-dyed Amish.” Indeed, according to Douglas Stevenson, Sanders

became The Farm’s most important unofficial ambassador throughout the local area. He spread the word among the rest of the neighbors that the hippies were okay. If Homer heard someone bad-mouthing the hippies, he would set them straight. Homer’s early support was an important breakthrough that smoothed the way for The Farm to gain acceptance in the redneck South.[31]

However, for several years the majority of the town’s inhabitants remained leery, and thus Farmies “had to hustle to make friends with our neighbors.” Coate was certain that if he and his fellow Farmies did not try to cultivate a good rapport with the locals, “they would have shot-gunned us right out of there and burned the place to the ground.” Gaskin and his followers believed that the best way to foster a relationship was to try to bond along religious lines, for Farmies considered themselves essentially a “religious group,” and thus they “decided to get into religious dialogue with the locals, matching our patchwork eclecticism to their Christian fundamentalism.” Gaskin invited members from the Church of Christ to attend the Farmies’ “services,” which according to Coate, they readily accepted because they “wouldn’t turn down the chance to preach to the heathens” and get them to repent their sinful ways, and consequently “they came up in great numbers for these meetings.” Much to the chagrin of many local pastors and preachers, Gaskin became a licensed Tennessee cleric, marrying many Farm couples and leading Sunday morning services, which were held either in the huge meadow on the farm or inside the school-house. Regardless of location, Gaskin preached a gospel that he developed from the mystical teachings of various world religions, a synthesis he referred to as “the psychedelic testimony of the saints” or the “totality of the manifestation.”[32] Suffice it to say, the moment Gaskin mouthed such esoterica, his message fell on completely deaf ears. Nonetheless, Gaskin and his compatriots were determined to find some sort of accord with their neighbors.

At one of the get-togethers, Gaskin told the story of the Tibetan Yogi Milarepa and how he was similar to “some of the Biblical heavies in the way he had to construct these stone houses and then tear them down, then rebuild them again, each nine times, as a way to become unattached to the fruits of your labor.” Apparently Gaskin’s “preaching” was beyond the ken of his local audience as the Church of Christ attendees failed to comprehend a single word of his message—rambling—let alone see any analogy to the Bible, and thus one of “the old guys stood up and said, ‘excuse me, now I don’t about this Miller feller [Milarepa], but I do know that the Bible is the word of God for him too.!’” Suffice it to say there was no meeting of the minds between the Farmies and the local congregation of the Church of Christ. Not to be deterred, the Farmies reached out to the Summertown Covenant Church, which resulted in a righteous harangue courtesy of the main preacher Johnny Prentiss and his wife Betty, in which the Farmies were told “the things you believe in are wrong,” and that they were condemning their children “to an afterlife in hell.”[33]

After that chastisement, the Farmies decided to abandon reaching out to their neighbors by trying to find religious commonality, an impossibility. They would henceforth pursue a different approach: time; that is “wait it out” and let the town-folk come around to them, which they believed Summertowners would do as they realized that the Farmies were no threat, that Gaskin and his followers were there to stay, and that they were more than willing to become good, participatory citizens in the town’s daily life. Most important, Gaskin was certain that his enterprise would eventually become a regional economic boon, and in that anticipation he was correct on a variety of levels.

Gaskin was the community’s undisputed leader, minister, and “spiritual guide,” personally setting Farm policies and procedures based on what he envisioned to be the Farm’s purpose and philosophy. As former communard Alan Graf remembered, “We had a charismatic leader, Stephen” through whom “most authority went. We weren’t a democratic society.” Indeed, the Farm defined the concept of an intentional commune, in which everyone had fairly specific work related roles or jobs to perform but were allowed or encouraged to choose the kind of work that most appealed to them. Unlike the majority of communes, the Farm was not a place one went to dream one’s life away in a psychedelic besotted haze. As Albert Bates noted, from the Farm’s inception, “It was never intended as some hippie crash pad or beatnik retirement home. It was a platform from which to launch efforts to improve the lot of poor and indigenous peoples, whales, and old growth trees. It was a means, not an end in itself. Stephen was more than a pacifist; he was an activist.” According to Ina May Gaskin, “Farmies” were “a special kind of hippie: they worked.” Indeed, according to New York Times reporter Kate Wenner, these particular “flower children” were

supremely industrious and disciplined. They have dedicated themselves to work in building a totally unselfish and compassionate culture in which others may seek refuge from mainstream civilization. As “spiritual revolutionaries” these pioneering youth are not so much trying to create a new society as to bring this country back to its early heritage.[34]

Gaskin could not have agreed more with Wenner’s assessment, telling interviewers from Mother Earth News

If you really want to be spiritual, you don’t want to have to sell your soul for eight hours a day in order to have 16 hours in which to eat and sleep and get yourself back together again. You’d like for your work to be seamless with your life and that what you do for a living doesn’t deny everything else you believe in. What we’re really into is making a living in a clean way. There ain’t nothing devious about it: Right out front, we’re trying to build an alternative culture.

For Gaskin and his comrades, there was no “cleaner way in making a living than farming. It’s just you, the dirt, and God. You can’t make friends with an acre of land and expect it to give you an ‘A’ like some college professor or something. You can’t snow that acre of dirt. But if you put the work into it, it’ll come back and feed you. It really will.”[35]

Gaskin wanted committed people and thus all potential communards had to spend time “soaking”—a trial or probationary period during which “candidates” participated in the communities’ various activities, work, and general lifestyle to see if such an experience in alternative living was how they wanted to spend the rest of their lives. At the Farm’s entrance, those wanting to enter the commune were told by the “guards” that “no animal products, no tobacco, no alcohol, no manmade psychedelics [LSD], no sex without commitment, no overt anger, no lying, no private money, no [ownership of] large pieces of private property” were allowed. If after “soaking” a visitor wanted to join the commune, they were required to take a vow of poverty, turning over to the community all cash, credit cards, and possessions, for they were no longer needed by a “Farmie.” Most important, initiates had to accept Gaskin as their teacher and guru. According to “Catherine,” who visited the Farm in the summer of 1973, looking for friends who had become full-fledged Farmies,

These people behaved as if Stephen Gaskin had some special wisdom that elevated him to the position of a holy man over themselves, people who I knew as well-educated, smart, talented, and formerly free thinking individuals. “Stephen says” were the buzzwords I heard over and over again.[36]

As Kate Wenner aptly observed, it was ironic that “the same people who once stood firmly and loudly against any absolute authority now accept Stephen Gaskin as their unquestioned and unchallenged leader.” Communard John Coate recalled, “The catch to living there was ‘copping to Stephen.’ You had to enter into a student-teacher relationship with him. If you accepted that kind of relationship, all was good with him and everybody else.” Wenner agreed, labeling Gaskin as “unabashedly egocentric,” which made him simultaneously the Farm’s “greatest strength and greatest weakness.”[37]

Gaskin consistently downplayed his role as the Farm’s leader, telling an interviewer from The Tennessean in 1981, that he only used that “terminology” when “copping to that on a national or international level that I am one of the leaders of our movement which is not just the Farm but all the long hairs and pacifists and hippies of the world.” Relative to the Farm, Gaskin referred to himself as “the coach,” declaring that real authority and “power” was exercised through the Council of Elders, who many disgruntled Farmies claimed was comprised of individuals who “thoroughly copped to Stephen’s ideas and way of doing things, no questions asked.” John Coate agreed that Gaskin did indeed put yes-people on the Council, that he “was inclined to surround himself with advisors who over time seemed to much prefer advising to nail banging, hoeing, or wrenching. And he sometimes delegated great authority to single individuals, some of whom were utterly unqualified to handle it.” As a result, many people “learned to kiss ass to keep their position in Stephen’s inner circle. They had to learn what to say and more importantly what not to say.” The emerging sycophancy coupled with Gaskin’s escalating imperiousness and refusal to accept any challenges to his “teachings,” had a deleterious impact on the community. As John Seward recalled, Gaskin equated any doubt in his leadership with a lack of faith in the Farm community and its mission. Consequently,

anybody who had doubtful thoughts running through their head was in fairly short order forced to split because you couldn’t maintain that feeling and stay there without bringing everybody down. So there was never any big impetus to radically change how things were because anybody who starting thinking that way was just steered out.

Walter Rabideau agreed: “The strange phenomenon that I started to realize was that you couldn’t tell the truth to him if it was about him.”[38]

Gaskin denied having “this lust for power,” and said that until the collective reached over 600 people, “we did everything in full meeting and consensus because everybody was there and anyone who wanted to argue could. That part was good at the time, but we got too big for that,” and thus according to some, Gaskin’s excuse for becoming more high-handed and autocratic. Kathleen Platt, a Farmie for nine years and a member of the Council of Elders, believed the council was a sham as far as having any real decision-making authority, a ruse designed by Gaskin to create the illusion among his followers that they had a say in Farm affairs. According to Platt, from the group’s first meeting,

Gaskin controlled the decisions of the board. Supposedly you had freedom of speech at the Farm but you would be shut down pretty fast if you said something against the flow. I was very excited when I was on the board but I found out it was a joke. We sat there for hours and smoked so much grass that decisions we could come to would all be erased in a couple of days.

In fairness to Gaskin, Platt admitted that “we asked for it. That’s the crux of it. He couldn’t be doing it if all these people did not bow down to him.”[39]

Another original Farmie, Wayne Bonser, agreed with Platt, leaving the Farm in 1976, “fed up with Gaskin’s authoritarian rule.” In Bonser’s view, Gaskin believed “he was the second Christ and everybody bought it back then” because “we were all taking a lot of psychedelic drugs back then,” and in Bonser’s view, Gaskin exploited his “disciples” perpetual hallucinogenic state of mind to dominate them. “No one questioned his authority and you couldn’t do anything unless you had his approval. He took whatever women he wanted and nobody questioned it.” What happened to those individuals who challenged Gaskin? According to Bonser, they would be visited by Gaskin’s “gang of henchmen. If anybody interrupted him at one of his gigs, he sends out one of the guys to remove them.” “Removal” meant exile from the Farm for as long as thirty days, or one was “busted” to a lower status job, such as the crew in charge of picking crops. Interestingly, until his falling out with Gaskin, Bonser was a “big honcho” on the Farm, involved in some of the operation’s plumb jobs such as the gate security crew, sanitation construction, and the most important one, “the pot crew.” Bonser eventually had a major falling-out with Gaskin over child-care issues, especially their diet, which was for quite some time “a kind of soybean corn meal mush, three times a day and rarely getting any fruits or vegetables. If your baby cries, Stephen said he’s probably on an ego trip. Never mind it’s tired, hungry, or thirsty. You should ignore it.” So disturbed did Bonser become by Gaskin’s imperiousness and callousness, that he believed “There are absolute similarities between the Farm and Jim Jones and Charles Manson.”[40] Another aspect of Gaskin’s “tremendous power” over the Farm’s “vibrations” that burdened many Farmies was his mantra that the Farm

was the guru for the rest of the world. Everybody on the Farm carried around the idea on their shoulders of being responsible for the whole world. Every act, everything you said, everything you did, the way you lived, the way you dressed, everything was having a vast effect all over the planet.

Matthew McClure agreed. “All of us there believed that we were in fact the hope of the world and that if anything happened to this small group of acid heads the world was going to collapse.” This was Gaskin’s message to his “tribe” every Sunday at their gathering in the meadow; that Farmies were “keeping it together for the entire world because we were a demonstration that people could live together in peace and harmony. Nobody would have gone there if they hadn’t believed that.” However, having to carry that illusion around in their heads “prevented us from trying a lot of things that would have made the Farm better.” Although Gaskin had fully embraced the hip slogan to “question authority,” when it came to his own people, “we were institutionally not supposed to think for ourselves in some areas. We weren’t allowed to change.” John Coate believed that Gaskin unwisely “stifled all that talent and brain power” that surrounded him, or tried “to mold it in a narrow fashion. I say Stephen was the luckiest guy in the world to have all that good energy and talent around him. Too bad he didn’t see it for what it really could have been.”[41]

As with any start-up experiment in alternative living, whether in the early 1970s or now, personality and philosophical clashes of will are inevitably endemic, causing alienation, hostility, and even despair among the individuals or groups involved. Such was the situation at the Farm during its formative years but to accuse Gaskin of being another Jim Jones, or worse, Charles Manson, is extreme in the least. No doubt Gaskin was indeed autocratic, self-serving, and probably on an “ego-trip” at times but as Kathleen Platt admitted “we asked for it.” Indeed, as already established in this paper through the memoirs of some of the Farm’s original members, virtually all of the individuals who followed Gaskin first on the caravan and then later to Tennessee, were, in some form or another, some of the more alienated, if not at times, desperate seekers from the 1960s hip-psychedelic scene, yearning for an alternative lifestyle to the mainstream economic culture of their time. Many believed they had found the answer to their quest in Gaskin’s Monday Night Class message, and thus initially were willing to embrace both Gaskin as their undisputed guru and his Farm idea. Although Walter Rabideau believed that Farmies had given Gaskin too much “control over our lives, and that “it was several years before we realized what was happening,” Rabideau and his compatriots nonetheless had “agreed to start a community following his [Gaskin’s] spiritual teachings.”[42] Moreover, as the Farm grew in population, peaking at around 1,500 members in 1979, it was virtually impossible for Gaskin to maintain his initial town-meeting, democratic consensus approach, and thus he, in consultation with a handful of others, increasingly made more and more of the decisions affecting the Farm’s daily operation, outreach, and commonwealth. He believed himself personally responsible for the well-being of so many people and in having to constantly exhort them to work toward the common goal, which was based on his vision of the Farm’s existence and purpose, which he made clear from the outset. Gaskin was a committed, serious seeker, wholeheartedly devoted to making his vision real and his enterprise a success within the context of the hippie ethos and its attendant values and priorities. So were many of his compatriots as confirmed by the fact that the Farm is still in existence and flourishing as testimony to both Gaskin’s idea and those individuals who continue to believe in his dream of a completely self-sustaining agricultural alternative to the nation’s capitalist techno-industrial macro-economy. Nonetheless, there was pressure from Gaskin and from his more devoted disciples to maintain above all else the community’s “good vibes” that required all Farmies to be “into the juice,” and that often meant “copping” to Stephen Gaskin’s way of being.

Although some had negative experiences at the Farm, for most “Farmies,” the place, at least initially “was like a hippie dream—you didn’t use any money, there weren’t any cops, there weren’t even adults. Everybody was your age. For some people that was really what they’d been looking for.” Most meaningful was that “a whole bunch of people learned to grow food and build houses, and we learned to live with a bunch of other people.... And doing it together made it so a lot of us could do stuff that we wouldn’t have been able to do if we’d done it individually.” Perhaps most important for the majority of Farmies, and what kept them on the Farm for more years than they thought possible, was their belief that

we were all one. We believed we were creating a unique reality, controlling our own destiny, and for some years it was true. You can’t do that without massive struggle at times. But once again the good feelings are often contained in the way people look into each other’s eyes and the silent understanding. It wasn’t the brainwash trip by any means. It’s a hard thing to quantify.

For Peter Else, the Farm provided “an escape from eight to five city living and the chance to form a model society, a chance to be closer to the land. Well, I did escape city living, but I ended up working from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m.; I definitely got closer to the land.” Moreover, by the early 1970s, large, experimental communities such as the Farm were few and far between and thus for many Farmies, “if you wanted to do something with other people” leaving the Farm “seemed kind of bleak.” Consequently, “a lot of people really gave Stephen a certain amount of lip service and ‘got with the program’ but were really there for the folks rather than being a hardcore [Gaskin] student.” For John Coate some of his “finer moments” were fairly elemental but nonetheless uplifting: “When someone would holler ‘Joint Break!’ across the [car] shop and we would retire to the woods for our communion, I felt that we were living on liberated soil. I could look around at the woods and my buddies and say, ‘this is ours.’ What could be finer than that?”[43] As with most start-up communes, there were the “starving times” and such a potential catastrophe visited the Farm during the fall 1972 and winter 1973, “wheat berry winter,” when all Farmies had to eat in any real quantity was boiled wheat berries: “Every night there they were on your plate, beside the blighted potatoes.” However, the hard-times did not bring about the Farm’s demise; quite the opposite: the true believers persevered even without Gaskin, who had been busted for growing marijuana and incarcerated for a year (1974–75) at the “Walls,” the Tennessee State Penitentiary built in the 1880s in Nashville. Overjoyed by Gaskin’s return upon his release, the Farmies presented him with a grand new residence they had built during his absence, a veritable palace compared to most Farmies’ meager abodes. However, to his credit, Gaskin sensed that such ostentation could easily alienate fellow communards and refused to live in his new home, which only enhanced his guru mystique. Nonetheless, Gaskin frequently exploited his followers’ love for him, feigning humility by sitting in his chair like a grand potentate, meeting and greeting people with “an attractive woman sitting on either side at his feet, leaning against his legs. The air would be filled with our sacramental herb [marijuana] and the anticipation of his profound teachings.” Indeed, in Matthew McClure’s view, “Stephen professed to think of himself as a fully enlightened spiritual teacher on a par with Buddha and Christ. The avatar of the Aquarian Age.”[44]

By the mid-1970s, the Farm had not only turned the corner relative to lasting for more than a few years but also had become “the place to go, especially in the summertime, when we got all the hitchhiking people, people without homes, the free-lancers, the free spirits. They were all out there and the word started getting out. We were getting 10,000 to 15,000 people a year (ten times our population), coming to visit the Farm, many of them just driving through on Sundays. We had guided tours for local Tennesseans as one of our community obligations.” Unlike many communes, Gaskin did not have a nonexclusion philosophy or policy, and countless people were turned away after their “soaking” or even at the gate, especially if the gate guards determined they were “real yahoos who were there to see if the ladies really were bare-breasted [as they indeed were at many communes] all the time or something, which they weren’t.”[45]

However, there were instances when Gaskin felt sorry for a seeker, especially if they were completely lost, mind-blown “blissed-out flower children schizophrenics who just couldn’t work but were going to get fed anyway. One of the things Stephen would occasionally advertise was that no matter how crazy you were, if you came to the Farm, he’d make you sane.” According to Walter Rabideau, sometimes the community could help someone recover from too much psychedelia, but in some instances no amount of group or individual therapy worked and thus,

We’d always have at least one psychotic, full-blown, total blissed out freak who would’ve been in mental institution if he hadn’t been on the Farm. When everybody was ready to thrown them off the Farm, they would go to Stephen and he would get stoned with them and give them another two days [to redeem themselves].

If they were simply unable to “cop” to Farm life after the two-day grace period, whether they were drugged out ex-hippies, a fugitive on the run, or any other form of miscreant unable to embrace the Farm ethos, “We’d buy them plane tickets, bus tickets, whatever, just to get them off the Farm and out of the state.” Despite the gatekeepers’ vigilance and probing questions,

Some people would know that if you said the right things you could stay. You got to stay for a month before you’d be ask to make a decision to live [on the Farm] or leave. They would stay and get about six weeks of free medical care, a roof over their heads, dope, friendly hippies, and the word was out that this was the place.

For Matthew McClure, the Farm’s “spirit of compassion” resulted in a “youthful arrogance” among Farmies, certain they could assimilate into Farm life and culture, “too broad a spectrum of people.” Walter Rabideau and John Seward agreed. “We overloaded ourselves and took on more than we could handle as a result of Stephen’s pep talks,” Rabideau told Kevin Kelly. Seward concurred, somewhat blaming Gaskin as well for the Farm “taking on all these welfare cases. Stephen would talk on Sunday morning about how you can’t close your heart, don’t get square, because with good karma, doing good deeds, it’ll all balance out and blah blah blah. But it didn’t really work that way.”[46]

One group of folk who particularly found the Farm to be “the place” to go, were young pregnant women, the majority of whom were unwed. As Walter Rabideau recalled, “Ina May put out the word to the nation at large that ‘Hey ladies, don’t have an abortion. Come to the Farm and we’ll deliver your baby free!’” As a result, between the Farm’s founding and when the Rabideaus left in the early 1980s, to their recollection, over 1,000 babies were born on the Farm and over half were “from people who didn’t live on the Farm. We’d have all these pregnant couples and women come to the Farm six weeks before they were due and at no cost, not even room and board, we would support them for six weeks before birth and sometimes for a month or two after the baby was born.” As far as the Gaskins were concerned, “There cannot be too many children living at the commune. ‘Farmies’ consider them to be their most important crop. They are raised with special care and are Part Two of the Farm’s dreams.” There was no doubt in Kathryn McClure’s mind that the Farm’s anti-abortion policy “saved a few babies’ lives” but the problem became that all too frequently the child’s parent or parents would simply up and leave one day, secure in the knowledge that their child would be taken care of by one of the Farm families. The parents might return for their child but in many instances they did not, abandoning them to the solicitude of Farm families, where they would be fostered out for several years among the community. As Kathryn McClure remembered, “at one point, one-quarter of the kids on the Farm had been dumped there,” and consequently it was up to the established Farm families to take them in. Such kindness bred resentment toward the Gaskins, for taking in the abandoned children represented a burden; one more mouth to feed, clothe, and care for, while most already had difficulty providing for their own children. As Susan Rabideau observed,

We made the mistake of thinking we could actually take on and help people before we were even helping ourselves, before we had enough for our own families. Our hearts weren’t closed; we were just overcrowded and didn’t have enough to eat.... You can’t be hungry and help somebody else. You have to be together and smart and well fed and know everything in your home is taken care of before you help others.

However, according to Gaskin, if one believed their child “was better than anybody else’s,” that was considered to be “one of the roots of racism. You couldn’t think more about your kids than you did about all the kids in the Third World.” Rabideau agreed with Gaskin in “consciousness” that “that was how it should be,” but such generosity was hard to embrace on a daily basis when “your own kids are right here in front of you and they don’t have boots for the winter.” Indeed, as famous author and Merry Prankster-acid head Ken Kesey aptly observed, “The commune idea of sharing was great but it all breaks down in the fridge.”[47]

Gaskin forbade nudity and as far as sex was concerned, Gaskin decreed, “If you’re sleeping together, you’re engaged. If you’re pregnant, you’re married.” As Mother Earth News remarked at the time, “There’s none of this hippie ‘free love’ monkeying around on The Farm.” The Farm was also definitively heterosexual in philosophy and orientation, with great peer pressure placed on singles to “couple-up” as soon as possible, for to Gaskin “the Basic Unit of Mankind was the heterosexual couple.” In that context, Farmies were supposed to follow the Tantric sexual path where lovemaking was not only for procreative purposes but as an equally important healing exercise for body and soul. Particularly affected by this philosophy were Farm males, most of whom came from very traditional male-sexual dominant, quasi-misogynistic backgrounds, in which women played a passive/receptive if not subservient role. As John Coate observed at the time, “The early seventies was the time when the feminist movement was on the rise. It was obvious that almost every male in America carried around with him certain inbred attitudes that assumed superiority over females.” However, on the Farm, the Gaskins were determined to reverse such “programming” as women now were to be “on top” so-to-speak, and as the phrase on the Farm confirmed, “The man steers during the day, and the woman steers at night. This meant for men that all traces of macho had to be eliminated. You had to ‘cop to your lady.’” As Cliff Figallo remembered, the new mantra “put sand in the Vaseline! There is nothing that does more to ruin the magic in bed than self-consciousness. The aim of all this, of course, was to enhance the sexual act for women and to extinguish the old stereotype of ‘Wham, bam, thank you ma’am.’” The Gaskins made Tantric sex part of the Farm’s creed and consequently those males who failed in bed to adhere to this doctrine often found themselves publically exposed and ostracized. If they hoped to remain part of the Farm community they had to “purge” themselves by spending time in a special tent Gaskin had constructed called “The Tumbler” where recalcitrant males “with rough edges could bump up against each other with the idea that they could smooth each other out” by spending hours “ferreting out the subconscious attitudes” that had caused the tension between themselves and their women or with other Farmies, regardless of gender. Individuals would remain in these “sort sessions speaking bluntly to each other without the inhibitions of politeness standing in the way” until they “copped to making visible changes.” For Coate and for many others, the Tumbler experience “was like a mental nudist colony. It was a definite flaw in our thinking to imagine that great numbers of people would be interested in that kind of thing.” Nonetheless, on the Farm, “a person’s inner business became everybody’s business.”[48]

One of the more absurd “sorting sessions” that occurred in The Tumbler involved a Farm woman who was “not into the juice” of the Farm’s “vibes” because she used “big words” such as “averted” and other such “non-Farmese” vocabulary, and for her refusal to use “ain’t.” The woman had a college degree in English and had published several short stories in Highlights, a children’s magazine, an accomplishment she hid from her Farm peers. According to the woman’s daughter, “They wanted her to sound more like them with slow, droned out, stony sayings and using words like ‘ain’t.’ She was very upset and crying in our bus after finding out that people didn’t like her using ‘big’ words. It must have been a long meeting because I don’t think she ever copped.”[49]

Homosexuality, although not outright condemned was frowned upon by both Gaskin and many communards, leaving “little room for out-of-the-closet gays. There were some gays on the Farm, but there was so little action that they didn’t stick around.” Although establishing such codes, Gaskin did not believe in conventional monogamy, sanctioning a somewhat strange polygamy of spouse-swapping that came to be known as “four marriage”— two couples married together. When asked about this type of “marital arrangement,” Gaskin responded by asking the interviewer “What part about being a hippie don’t you understand?” Perhaps most interesting, Farmies advocated natural birth control, forbidding all artificial methods that prevented conception. “In their place, we developed the basal temperature/cervical mucus method, which could be very effective if you were very disciplined.” However, as Cliff Figallo recalled, “Not many of us were at the time, and it took several children for most of us to either catch on to the method, or to cheat and buy rubbers anyway, or to give up lovemaking altogether.” By the close of the decade, thanks in large part to the procreation policies, the Farm’s population had grown from around 300 to 1,500.[50]

Farmies were hardcore vegans, eating soybeans for protein, prepared in as many different creative ways as possible. According to one communard, the Farmies’ devotion to vegetarianism reflected their belief that there would be more food “to go around the world if people ate soybeans instead of cattle.” How fanatical of vegans were the Farmies? As one young member recalled, “The adults at ‘Seven Nations’ (my house) had a meeting because my grandmother sent a gigantic block of Wisconsin cheddar cheese to us. The adults were deciding whether to give the cheese to the neighbors (off the farm), or to just bury it! Meanwhile, the kids, including myself, managed to finish off the entire block of cheese before the issue was resolved.” Another young communard remembered “getting really sick of eating so many soybeans in every form,” and another not having her first peanut butter and jelly sandwich until she was nine after having lived at the Farm all her life. “I was like ‘Oh my God, this is the best thing I’ve ever tasted in my life!’”[51]

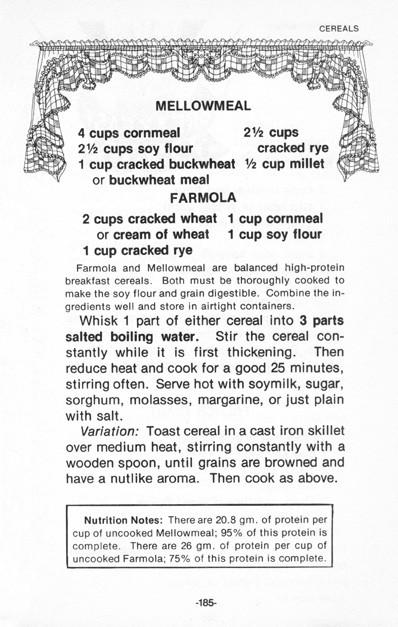

As noted earlier, one of the Farm’s dietary staples, especially for breakfast and lunch, was a soybean-cornmeal mush like “oatmeal” that the children in particular came to loathe. As one Farm child recalled,

The repulsive oatmeal made me gag every morning and every afternoon when we had cold, gloppy leftover oatmeal for lunch. It was agonizingly hard to force through my mouth and down my throat. I would plead, beg even cry, in a desperate attempt to be spared from eating it. It made me choke and vomit with every despicable bite.

Some of the other children were allowed “to pour lots of white sugar on theirs but I could not have any sugar on my bowl of torture because to my mom sugar was the root of all evil only for making cakes on peoples’ birthdays.” Dinner was better as long as it “wasn’t dumplings, slimy balls of boiled dough just as gag worthy as oatmeal.” Fortunately both the kids and adults got a respite at dinnertime because they got to eat “soybean tortillas and that was eating happiness. I wished we could eat happiness for breakfast too.” Indeed, “soybeans and soft tortillas—simple, nutritious, and wonderfully satisfying,” became the Farm’s “national dish.”[52] Parental devotion to an exclusively vegan diet unfortunately deprived communal children of other, much-needed protein sources. So desperate for such nourishment did Farm kids become that they were overjoyed one day when “Archer of the Dogwood Blossom Household scored some cat food, the delicious, little reddish x-shaped treats we weren’t supposed to touch or eat.” News of Archer’s surreptitious acquisition spread like wildfire to a neighboring Farm household, and soon surrounding him were “a growing harem of hungry little vulture children,” all of whom would “really love some of that cat food, the thought of its tasty, tasty, gourmet crunch was irresistible.” Apparently Archer was in a magnanimous mood that day and shared his treasure, making sure all “got some of the tasty morsels. Cat food is worlds better than slimy, putrid oatmeal. I am so, so happy to have eaten several pieces of forbidden, rare, precious cat food. Thank God we did not get caught by the giant grownups.” The Farm’s frailer children were somewhat more fortunate than the “normal” kids because they were placed on “the skinny kid’s list” and were to receive extra food, sometimes even “exotic foods” such as bananas or oranges, which was “unheard of because we ate nothing that did not come from our own fields.” The news of the arrival of such delicacies often caused the older kids to go on clandestine “raids of the food stashes to get some oranges that were reserved for the babies. They weren’t bad kids but that’s just what they had to do.” Indeed, as Marilyn Friedlander confirmed, “We were pretty much a town that ate the same food every night. Sometimes those foods and the events surrounding their appearance were rather weird—the mere mention of them causes simultaneous laughs and moans.”[53] As was true in many communes determined to use only natural or organic substances and ingredients rather than those that had been chemically or artificially adulterated, processed, or man-made, basic hygiene and health care were often neglected in the name of purity and righteousness. On the Farm, both toothpaste and band-aides were not allowed into the compound. As one Farmie recalled, she brushed her teeth every night but could not remember what her mother gave her to use as “toothpaste.” However, she remembered vividly the day “we got some toothpaste, it was a treat. A man would use his pocket knife to slice open a completely flattened tube of toothpaste while dozens of people stood around hoping to get a miniscule scraping of its rare, sweet insides.” For many Farm kids, “the best thing about getting hurt was possibly getting an incredible band-aide if there was [sic] any.” Like bananas, band-aides, “out of a rarefied packaged wrapper,” were “from the outside, something that wasn’t horse poop.” Farm kids would often purposely scrape or wound themselves in order to “bask in the glory of an extraordinary plastic band-aide. Any kid with a marvelous band-aide displayed it proudly and kept the flesh-colored plastic treat on as long as possible” because one never knew “when you’d be so blessed to get another one instead of a plantain leaf.”[54]

Although man-made psychedelics were banned at the farm, marijuana, peyote, and “magic mushrooms,” all natural substances, were considered to be a holy sacraments essential for enlightenment. Indeed, the majority of Farmies could not wait for what they called “hanging out with Uncle Roy,” which meant sitting in a big circle, talking and passing around “the doobies.” Gaskin believed the Farm grew “the cleanest form of pot” in the country, and it was “lovingly grown” as those Farmies responsible for its cultivation “not only planted it but sat nude and played flute to it.” Most important to Gaskin was that “no money ever changed hands.” Gaskin’s attitude toward drugs was rather unusual for the time:

Don’t lose your head to a fad. The idea is that you want to get open so you can experience other folks, not all closed up and off on your own trip. So you shouldn’t take speed or smack or coke. You shouldn’t take barbiturates or tranquilizers. All that kind of dope really dumbs you out. Don’t take anything that makes you dumb. It’s hard enough to get smart.[55]

For Farmies as well as for most other rural communards, love of nature and dope became symbiotic. Only on some hallucinogen could the wonder and beauty of the wilderness be truly experienced. On dope, one felt in tune with the “stars, migratory patterns, planting cycles, the chirping of insects.” Nature talked and stoned country hippies listened in ecstatic communion. “The planet is a sentient companion! Everything that lives is talking to everything and communicating its response back to everything, without stopping, constantly!” For many rural freaks, dope indeed made “it possible to have a decent conversation with a tree.”[56] Money was also forbidden and was not needed; everyone picked up their household rations at the Farm Store. If cash was required for an errand to nearby Summertown or Hohenwald, one applied for funds and received the exact amount needed from the “Bank ladies.” Vehicles were also parceled out in the same fashion; all cars or trucks were procured at the Motor Pool and signed out for a specific time and use.[57]

Gaskin left prison with “big time visions of grandeur” for his particular brand of rural communal alternative living. He was certain that the Farm had become such “a heavy-duty flagship for humanity” that the concept needed to be expanded to as many parts of the country as possible now, while his ideas were still “hot.” Gaskin thus began borrowing money to establish “sister farms” in Wisconsin, Missouri, and Florida. Started by “colonizers” from the original Tennessee location, these were intended to become “heavy duty farming operations cranking out cash crops.” Unfortunately Gaskin’s grand plans never came to fruition; none of the three locations, for a variety of reasons, ever got off the ground, ultimately plunging Gaskin and many of his fellow Farmies into serious financial straits. By 1978, as John Coate succinctly put it, “The Farm from then on had a huge debt as each year went by. We [had] lost our ass.”[58]

Also by that time increasing numbers of original Farmies were growing weary of their Spartan existence and Gaskin’s imperiousness. By 1980 the majority of male Farmies had taken on weekend work in Nashville and the surrounding area, hoping to earn enough money to improve their living conditions, especially their homes. Henry Goodman, for example, wanted to buy linoleum to replace the unfinished plywood in his house “so you could keep it clean and the kids and babies who were crawling around on it wouldn’t get grubby or sick.” After Goodman and some other men had worked for seven straight Saturdays, for ten hours a day, they had enough cash to make the repairs on their homes. Gaskin, however, announced that their money “had been earmarked for other purposes.” For Goodman and many others, Gaskin’s pronouncement proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. “I remember feeling totally ripped off,” Goodman told an interviewer. “The kicker was that as soon as the Saturday work money got collectivized, guess what happened? People quit going out to work on Saturdays. This was a bitter pill for us to swallow, to see that there really was something to the capitalist, free-enterprise philosophy after all.” Walter Rabideau agreed, no longer “believing in the system.” After waiting several weeks for shoes from the Shoe Lady while his children wore “sneakers with their toes coming out the ends,” Rabideau “started buying my kids’ shoes on my own. I just avoided the whole system. I’d go out and work Saturday, save the money, and take the kids to K-Mart or someplace on Sunday.” By the early 1980s, Gaskin and the Farm’s other true-believers had no choice but to acquiesce to “capitalist Saturdays,” allowing Farmies who got Saturday jobs to keep their money. “At first you could only spend it on houses,” John Seward recalled, “but then it got to where you could use it for anything.” For several years Seward and his compatriots “didn’t have to think about money. This was great. I never touched money, I never had anything to do with money.” However, during his last three years on the farm, Seward “never thought about anything but money.”[59]

By the early 1980s many adult Farmies worried about their children, most of whom had been living “a Third World Existence in the U.S.A.” Although the adults had willingly become “voluntary peasants,” their children had taken no such vow of poverty. Concerned for their children’s future, increasing numbers of families began leaving the farm, opting to re-enter mainstream society rather than endure more years of deprivation. “Re-entry” for children born and raised on the Farm proved to be quite a psychological, sociological, and emotional adjustment. After her parents divorced, Rena Mundo, along with her sister Nadine and brother Miguel, moved with their mother to Santa Monica, California, where she recalled feeling “like foreigners in our own country. It was really scary. I couldn’t tell the difference between a Mercedes and a Corvette. Being from a hippie commune wasn’t cool. They [people] were like ‘Are you from a cult? Are you a Communist?’ So we completely buried it.” Zane Kesey, son of legendary acid-head, Merry Prankster, and author Ken Kesey, had similar experiences. “I remember when one of the kids at school called me a hippie. I cried and asked my mom what it meant. She said a hippie is someone who is closer to Jesus.” Although extreme in its indictment of communal living, there was perhaps an element of truth to Newsweek’s assessment that most of the children in hippie communes at the time were “illiterate, ignored, and unprepared.”[60]

In most communes children were raised by all the adults and thus the traditional, exclusive parent-child relationship of the nuclear family had been replaced by an extended family of affectionate adults who all contributed to each child’s education and development. As one communard noted, “Nowadays, each child has a special relationship with his own parent (bedtime stories and special cuddling and such), but the casual observer to the farm usually can’t tell which child belongs to which adult.” According to Kate Wenner, similar to most commune children of the time, “The young Farm hippies enjoy a state not found in the rest of our society. Rather than underling, they are treated on an equal basis by their parents. Calling them by their first names, the children view their parents more as friends.” Such a relationship between communal parents and children, and between adults and children in general in the hip counterculture, stemmed largely from the hippie belief in equality, a determination to remain “forever young,” a wholesale rejection of all bourgeois convention and values, and as part of their liberation ethos that they extended to children and adolescents, whom they believed were as oppressed as the era’s other marginalized affinity groups. Indeed, hippies disdained virtually all aspects or phases of the contemporary notions of white middle class adulthood, and thus as Raymond Mungo declared, hippie males in particular battled daily “the forces attempting to make me grow up, sign contracts, get an agent, be a man. I have seen what happens to men. It is curious how helpless, pathetic, and cowardly is what adults call a Real Man. If that is manhood, no thank you.” As another communard declared, “Grownups are dead.”[61]

Such contempt for adulthood and veneration of youth naturally led hippie parents to “disavow most of the dominant models of parenthood,” since they themselves refused to grow up “to meet middle class standards of maturity and responsibility. These standards are symbolic of what they dropped out of and dropped out for.... Like the little kids who are their children, the big kids who are the children’s parents are busy ‘seeking their identities.’” In short, on many communes, it became a case of children raising children and consequently children were left to make their own choices and decisions, which in many if not most instances, would be unthinkable today. Nonetheless, as Raymond Mungo made clear, the children in his commune were “fully peers by the time they’ve learned to eat and eliminate without any help.” Consequently, for many communal children “there was something more important than Saturday morning cartoons missing from their formative years—guidance.” Communal children were praised by their adult-parent-peers for their displays of self-reliance and “responsibility for taking care of ourselves.” However, as one former child communard remembered, for him “it was too much. I was a little kid and I needed to be taken care of. We had too much freedom. I wish my parents would have pushed me a little harder.” Another child communard remembered “actually begging my mom for rules. ‘Let’s have a rule where kids have to go to bed at a certain time every night!’ I said.... I longed for discipline, for someone to tell me, ‘That’s quite enough of that young lady.’” However, in hippiedom’s heyday, “discipline was out and wild, Dionysian revelry was in.”[62]

To their credit, when it came to exposing Farm children to sex and drugs, the Gaskins and Farmies in general, adhered to almost puritanical policies compared to their contemporaries, where marriage and family were eschewed and thus “courtship, coupling, uncoupling, and recoupling [occurred] as frequently and intensely after they are raising children as before.” Despite the brief tenure of four-marriage, Gaskin promoted monogamy and family solidarity and, by comparison, a relatively chaste sexual environment, largely because there were so many Farm children around whom Farm parents and Gaskin believed should not be exposed to random sexual practices and discussion. Although devoted to marijuana use, Farm parents did not encourage their children (at least until adolescence) to indulge. Quite the opposite environment existed on most communes, where “Sex was way too much out in the forefront. We knew too much—we were exposed to a lot of talk about sex, a lot of hearing sex, seeing sex, a lot of dirty jokes.” As far as drugs were concerned, one child communard recalled being “provided with LSD when I was 13 and told, ‘You’ll probably experiment, so you might as well have the best.’”[63]