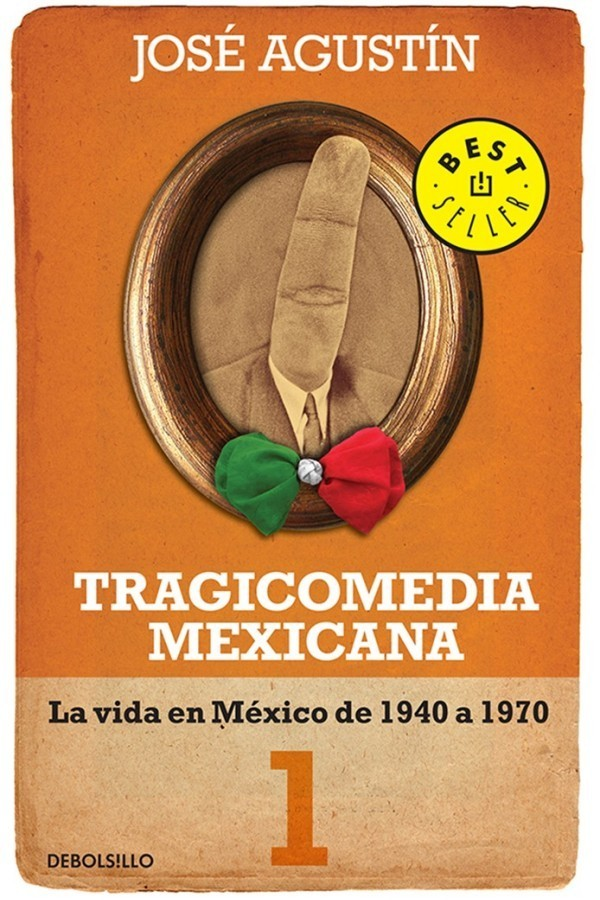

José Agustín

Mexican Tragicomedy Vol. 1

The Life of Mexico from 1940 to 1970

3. The Stabilizing Development (1952-1958)

From Chachachá to Rock and Roll

“Saint Madriza, Patron Saint of the Grenadiers”

4. The “Correct” Left (1958-1964)

[About the author]

José Agustín was born in Acapulco in 1944. A little less than two decades later he began to publish, placing himself at the forefront of his generation. He was a member of the literary workshop of Juan José Arreola, who published his first novel, La tumba , in 1964. He has been a fellow of the Mexican Center of Writers and of the Fulbright and Guggenheim foundations. He has written plays and film scripts, a field in which he directed various projects. Among his works are De perfil (1966), Inventando que sueño (1968), Se está haciendo tarde (final en laguna) (1973, Dos Océanos award from the Biarritz Festival, France), El rey se acerca a His Temple (1976), Deserted Cities (1984, Colima Narrative Prize), Near the Fire (1986), Prison Rock (1986), There is No Censorship (1988), Spilled Honey (1992), The Belly del Tepozteco (1993), Two hours of sun (1994), The counterculture in Mexico (1996), Flight over the depths (2008) Stories Complete (2001), The Great Rock Albums (2001), Life with my widow (2004, Mazatlán Literature Prize), Armablanca (2006) and Diario de brigadista (2010). He has published essays and historical chronicles, including three volumes of Tragicomedia mexicana (1990, 1992, 1998). In 2011, the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District awarded him the Medal of Merit in the Arts for his literary career; and he was awarded, along with Daniel Sada, the National Prize for Sciences and Arts that same year.

[Epigraph]

To Andrés, Jesús and Agustín, may it be easy for them! and to Mercedes Certucha and Homero Gayosso

1. The Transition (1940-1946)

Here Comes Golden Eggs!

In 1940, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo married for the second time and Mexico was on the tail of the tiger. There was intense unrest. Lázaro Cárdenas's revolutionary measures (agrarian reform, strengthening of workers, socialist education and oil expropriation) benefited the people but also aroused active opposition from landowners, bosses, the Church and part of the middle class in the cities. All these forces identified Cárdenas as a communist danger and defended themselves by attacking: investments were reduced, capital fled and a speculative fever of urban land was unleashed, which in 1940 increased in value by up to 200 percent. The rich also rushed to buy luxury imported cars, and Packards, Lincolns and Cadillacs circulated the streets, paved or not, of Mexican cities.

The big foreign companies, for their part, contributed to the economic chaos by withdrawing their money from Mexican banks, which simply stopped granting loans. As usual, the government continued to overextend itself and therefore printed banknotes vigorously; price increases, especially for basic goods, deepened the shortage and ended up exasperating the entire population, since no one was still recovering from the effects of the oil expropriation and, trying not to worry too much, the great war was taking place in Europe, Africa and Asia.

The rejection of Cárdenas benefited two military leaders: Joaquín Amaro, a radical right-winger, and the “moderate” Juan Andrew Almazán, a former Huerta member, “businessman and commander of troops,” who in January 1940 founded the Revolutionary Party of National Unification ( PRUN ). Amaro was not far behind and created the Federation of Revolutionary Oppositional Groups ( FARO ). The two new dissidents of the system announced their candidacies for the presidency of the Republic and (Almazán with greater caution) spoke out against socialist education, the ejidos, the Confederation of Mexican Workers ( CTM ), the left, the expropriation of oil and the anti-democracy of the official party. Both proposed “to restore the confidence of investors and rectify the mistakes made.” However, it soon became clear that Almazán was far ahead of Amaro.

The enormous strength that the right was gaining was decisive for President Cárdenas to choose a successor, since his reforms to the system did not include the will to democratize but rather the consolidation of the impressive powers of the presidency. Within the Party of the Mexican Revolution ( PRM ) there were two vigorous campaigns seeking the official candidacy for “the big one.” One of them, that of General Francisco J. Múgica, Secretary of Communications, represented the continuity and expansion of the revolutionary reforms, and was the natural choice of the left. Cárdenas knew that if he leaned towards Múgica, as he very possibly wanted, the right would become exacerbated against him and the situation could become unmanageable. He therefore chose the other existing candidate, that of General Manuel Ávila Camacho, Secretary of War and Navy, who had managed to position himself in the “center” and was a neutral element who could unify the great diversity of interests that were boiling in the PRM , in addition to taking away the flags of the opposition without abdicating the principles of the Mexican Revolution. “You will be the President of the Republic,” Lázaro Cárdenas is said to have informed Ávila Camacho. “And if anyone receives a card or letter from me, do not pay attention to it. It will be because I was forced to give it.”

Lázaro Cárdenas used all the ostentatious weight of his office in favor of his chosen one. He brought him together with Vicente Lombardo Toledano, Marx's old wolf, general secretary of the then very powerful CTM , and managed to get the distinguished teacher of high opportunism to support Ávila Camacho, because "it was necessary to choose," Lombardo declared, "not the man who offered the most to the labor movement but the one who would guarantee the unity of the Mexican people and its revolutionary sector." With this, General Múgica began to say goodbye to his presidential ambitions.

The National Peasant Confederation ( CNC ), the always weak and manipulable peasant sector, also satisfied the president's wishes and supported the candidacy of Ávila Camacho. The same occurred with a majority of military officers (the most conflictive sector of the party) and governors, led by the young and eager governor of Veracruz, Miguel Alemán, who was named general secretary of the Pro-Ávila Camacho Committee, thereby practically ensuring his position in the next cabinet.

With all that force behind him, Ávila Camacho raised the conservative volume of his campaign and never tired of suggesting that he would carry out the rectifications that were demanded. On the opposition side, Joaquín Amaro saw that he had little chance of winning and, grumbling, withdrew from the electoral game.

Rafael Sánchez Tapia had also been registered as a candidate, but he never gained any traction. The National Action Party (PAN ) had only just been founded in 1939 by Manuel Gómez Morin and did not present a candidate for the presidency, but it supported Andrew Almazán.

Thus, all expectations were pinned on Manuel Ávila Camacho, who had the overwhelming support of the government, and on Juan Andrew Almazán, whose “green wave” grew and grew in the cities and gained the support of many people. Almazán’s campaign soon became a real threat, and the government and the PRM plotted a ruthless “dirty war” against the Almazanists. In several cities (Monterrey, Puebla, Pachuca, for example) the local authorities harshly repressed the opposition and there were numerous deaths and injuries; in many other parts of the Republic all pro-Almazán activity was systematically harassed and obstructed. All these circumstances were ominously rarefying the political atmosphere of the country.

President Cárdenas had promised that the elections would be clean and that there would be absolute respect for the popular vote. But Almazán kept repeating that the government and the PRM would carry out a fraud of such colossal and gross proportions that a national insurrection in defense of the vote would undoubtedly break out. General Almazán had planned, for when that happened, to form his own Almazanist congress, “seat of the legitimately elected powers,” which would qualify the elections, name him president-elect, and elect a substitute president. Almazán would go to the United States and lead the revolt, call a general strike, and coordinate the armed groups that would take over the cities.

Tensions were at their limit on July 7. The trigger for the conflicts was a purely surrealist arrangement, whereby polling stations were set up with one employee of the authorities and the first five citizens who showed up. Of course, everyone wanted to be the first to arrive. Both the PRM and the PRUN formed heavily equipped shock brigades. The CTM had promised 40,000 workers to do “electoral surveillance,” but at the last minute the workers disobeyed their leaders and the CTM brigades never showed up. This allowed many polling stations to be occupied by supporters of Almazan. Manuel Ávila Camacho was unpleasantly surprised to find that all the officials at the polling station where he voted had photos of Almazan on their lapels.

Gonzalo N. Santos, the chief of San Luis Potosí, left us in his Memoirs a narrative of the events of July 7 that is truly extraordinary for its cynicism. By seven in the morning, Santos had already killed an Almazan supporter in a shootout; he then formed a shock brigade that came to have more than 300 people, and with it he dedicated himself to attacking polling stations with gunfire. People went out to vote in large numbers and, at least in the cities, they did so overwhelmingly in favor of Almazan and the PRUN candidates . But soon after, the brigades of the Pro-Ávila Camacho Committee arrived and, with gunfire, made voters and polling station representatives flee. They knocked down tables, broke ballot boxes, and exchanged gunfire with the Almazan supporters, who were numerous and were everywhere.

President Cárdenas, accompanied by the Undersecretary of the Interior, Agustín Arroyo Ch., drove around in his car to watch the voting, and found that the polling station where he was to vote was well guarded by the Almazanists. By telephone, Arroyo Ch. urged the brigades to intervene so that the president could vote in adequate conditions. The shock group quickly responded to the call. From several blocks around the polling station there were shooters on balconies and rooftops, and all of them were shooting down the Avilacamacha troops, thanks to the irrefutable bursts of Thompson machine guns with which they made their way.

“Give up, you sons of bitches, here comes the Golden Eggs!” shouted General Miguel Z. Martinez, who would later become head of the Alemán police in the capital. The defenders capitulated and “after a cannon shot to the head” they left one by one. “Quickly, you bastards, whoever stops will be hunted down like a deer.” The firemen arrived instantly and, with high-pressure hoses, cleaned up the blood stains that were everywhere; the Red Cross, helpful, removed the corpses and wounded. The polling station was rearranged, a new ballot box was put in, and at last the citizen president and his companion, Arroyo Ch., were able to vote. “The street is so clean,” said Cardenas upon leaving the polling station. Santos recounts: “I answered him: ‘Where the president of the Republic votes, there should be no garbage dump. ’ He almost smiled, shook my hand, and got into his car. Arroyo Ch., less hypocritical, told me: 'This is very well watered, are you going to have a dance?' I answered: 'No, Chicote, we already had one and with very good music.' Cárdenas turned a deaf ear...

"I ordered the improvised members of the polling station to put in the new ballot box, because it would be inexplicable that in 'the sacred urn' there were only two votes: that of General Lázaro Cárdenas, President of the Republic, and that of Arroyo Ch., Undersecretary of the Interior. I told the 'scrutineers': 'Empty the register and fill the little box, and do not discriminate against the dead, because everyone is a citizen and has the right to vote.'"

Armed encounters took place throughout Mexico City throughout the day. In the afternoon, huge Almazanist crowds gathered around El Caballito. They were awaiting the arrival of their leader so they could charge against the Palace, which, of course, was already well guarded by the army. But Almazan never arrived.

In the end, 30 people were reported dead and 157 wounded. Clashes took place almost everywhere, but were especially bloody in Ciudad Juarez, San Luis Potosi, Monterrey, Ciudad del Carmen, Puebla, Saltillo, Toluca, Ciudad Madero and Coatepec. The elections were peaceful only in Nogales, Hermosillo, Tampico, Piedras Negras, Mazatlan, Torreon, Chihuahua and Ensenada. Officially, there were 17 deaths in the provinces. The disturbances, clashes and irregularities were so numerous that Juan Andrew Almazan openly alleged illegality.

For his part, Manuel Ávila Camacho went to rest that night at his house. Gonzalo N. Santos relates: “Don Manuel told me: 'Well, I have the impression that they have won the elections and I, in those conditions, out of shame and decorum, am not going to accept winning.' Don Manuel burst into tears. I told him: 'No, sir, do not have that impression, it is false, the capital of the Republic has always been reactionary, but now it is more so; these votes for Almazán, you can be sure that they were cast against Cárdenas and also against the Revolution… But for no reason and in no way are we going to betray the Revolution by allowing Almazán to vote, never!' Don Manuel began to cry again and told me: 'I will never betray the Revolution and for it I do not mind losing my life as I have already demonstrated, but I will not accept a victory like that.'” Of course, the next day he had already changed his mind.

After the elections, Sánchez Tapia announced that he was rejoining the army, which made it clear that he had only entered the contest to legitimize the elections by accepting the result. Cárdenas bought rifles and ammunition, and carried out movements in the army in anticipation of the insurrection. And Almazán flew to Cuba. He wanted to meet with Cordell Hull, the American Secretary of State, who was participating in the Havana Conference, in which the northern empire sought to ensure the support of the Latin American countries in the world war. To begin with, Hull did not want to receive Almazán. Then, he denied him a visa under an assumed name and, finally, the American government revealed to Cárdenas details of Almazán's military plans. He, of course, was unaware that days before Miguel Alemán had spoken in Washington with Sumner Welles, the Undersecretary of State. Alemán gave him guarantees that Ávila Camacho would support the United States in the war, and that he would resolve the controversies between the two countries. The United States therefore agreed to send Vice President Henry Wallace to strengthen the battered legitimacy of the transfer of powers. However, if the Mexican delegation at the Havana Conference did not cooperate with the United States delegation, confidential information revealing that the elections had been a tragic farce could reach the Almazanistas.

On August 15, the Electoral College, completely controlled by the PRM , had already qualified the elections and gave the presidency to Ávila Camacho with two and a half million votes. A last sinister joke was made about Almazán by recognizing him with 15 thousand votes! Complaints of electoral fraud were heard everywhere, since the press and the radio supported Almazán; only El Popular , leftist, and El Nacional , official, supported the government. In September, two congresses were formed: the Almazanist one and the official one. In the first, Juan Andrew Almazán was declared president-elect, who was then in the south of the United States, without daring to do anything. Shortly afterwards, the Plan of Yautepec was promulgated and Manuel Zarzosa, Almazán's right-hand man, died in Monterrey. He never returned to the country nor led any insurrection. In November, he resigned from the post of president-elect, "as the only way to achieve the tranquility to which my supporters have a right." These people, for their part, had already had a taste of the barbarity that still prevailed in the system, and then they were hit by a hangover that plunged them into frustration, first, and finally into the conviction that they had been betrayed.

All of this, in a short time, generated a deep distrust of the citizens towards the electoral processes, which translated into apathy, disinterest and high rates of abstentionism, which always benefited the government and the official party.

In his last government report, Lázaro Cárdenas said in reference to the elections and without paying attention to the cheers for Al Mazán that were heard in the Chamber of Deputies: “The government rejects, based on its democratic concept, the use of all violence that it has incessantly tried to banish from the public life of the country. Therefore, it roundly condemns any contrary procedure, whatever the tendency or significance of the victim or the aggressor. And it considers it even more reprehensible when such a system is presented with foreign contributions, devoid of any feeling of respect for the State that welcomed it.”

But none of this could erase the resentment and deep offense of the population because of the electoral fraud. After the report, Cárdenas spent the remaining 90 days with the utmost discretion: all the while he supported his chosen one to the point that he even softened many of his political positions so as not to hinder him. Quietly, behind the scenes, as politics is done in Mexico, he moved his pieces and applied pressure so that his ideas and his followers would not be left completely uncovered. He had hopes that the next administration would be guided by the second six-year plan that his best cadres had prepared.

General Ávila Camacho, for his part, emphasized his moderate and conciliatory traits, and businessmen breathed a sigh of relief when they saw that the president-elect had declared himself a believer (“now he will be called Ávila Camacho , ” people joked), which scandalized many of the old Jacobins. But things began to clear up towards the end of November, and only the very absent-minded did not realize that there would soon be serious changes in the regime. Few, however, understood the scope that the new rules of the game that were beginning to take shape would have.

On December 1, Manuel Ávila Camacho took office. The general realized that everything had gone well for him up to that point, but also that his position was not firm enough. To begin with, he had to “restore the confidence” of investors, as he had promised, in order to calm the waters of discontent and ease the pressures of the wealthy people, who were confident of their power in the face of the avalanche of concessions they were obtaining. Ávila Camacho’s main objective was to take full advantage of the situation offered by the world war to industrialize the country. In this way, not only would he make businessmen happy, but Mexico would no longer be a backward country, neither self-sufficient nor a supplier of unprocessed raw materials. The idea was that, without rejecting foreign capital in the least, an industrial infrastructure had to be developed so that we would not have to import all the new and good things that high technology offered, since Mexican industry would take care of keeping us well supplied and, as far as possible, up to date and of good quality. Therefore, from the beginning the president rejected all rhetoric that could seem socialist, he encouraged and even used the new anti-communist fashion and he was determined to promote the industrialization of the country. He allocated between 50 and 60 percent of government spending to support private enterprise. Of course, from the beginning he also ignored the famous second six-year plan with which Cárdenas intended to consolidate his reforms, he rejected any type of planning with a socialist scent, and imposed the pragmatism of the supposedly free market.

After some hesitation, the businessmen decided to take advantage of the opportunity. There was no point in holding on to ideological resentments if the regime offered such good conditions. The passion for Almazan or the sympathies for the PAN were left behind . Many hard-working and ambitious titans of industry had emerged with the governments of the revolution and moved very well within such peculiar waters. Others went from high political positions to juicy businesses that enriched them in a short time. And still others, those of Porfirian roots who survived the Revolution, also became integrated into the new politics. For example, the high leaders of the Monterrey group in January 1942 met with President Ávila Camacho to happily tell him that they were renouncing their oppositional tendencies because they had seen that the new government in truth “did not fall into the errors of the previous one.” In reality, all the bosses received enormous benefits, ranging from tax exemptions, subsidies, credits, streamlining of procedures and even outright complicity in many cases.

On the political level, Ávila Camacho had to balance between an official (Cardenista) left that was still very powerful and an increasingly belligerent right that did not cease its pressures. The new president's idea was to make the two political poles confront each other while he positioned himself as the supreme arbiter, alternating concessions to each group according to their specific needs. To the right he would offer the "rectification" of the controversial reforms (socialist education and agrarian distribution), but at the moment he considered it appropriate. To deal with the left he had to dismantle the positions that Cárdenas had left him and reduce the power of the CTM in the political and labor fields. The best way to do all this was to strengthen himself and his brand new team. To do so, he had the immense power that the Revolution had given to the presidency (and that Cárdenas consolidated and expanded), and also the context of the world war, which allowed him to call for national unity with more than justified reasons.

Ávila Camacho's cabinet was an example of the conciliatory negotiations necessary to heal the cracks in the system. To satisfy the right-wing supporters of Callista, he placed Ezequiel Padilla in Foreign Relations, who was "very well connected with the United States." In the Ministry of Economy he appointed Javier Gaxiola, who belonged to the group of political entrepreneurs of former President Abelardo L. Rodríguez.

For his part, Cárdenas had managed to get several politicians who identified with his ideas to obtain important positions. Luis Sánchez Pontón was appointed to Public Education to guarantee the continuation of socialist education. Ignacio García Téllez obtained the brand new Secretary of Labor and Social Security, which emerged from what was the Autonomous Department of Labor. And he placed Jesús Garza in Communications and Public Works. By the way, this appointment infuriated Maximino Ávila Camacho, governor, chieftain of Puebla and brother of the president, who wanted that position for himself. Maximino ranted to anyone who would listen that Cárdenas had chosen his brother because he was weak and easily manipulated. “Another maximato!” complained the governor of Puebla, who would undoubtedly have preferred a “maximinato.” By the way, there was a joke that when he had breakfast, Don Manuel ate tongue because his brother kept the eggs.

But Maximino and the jokes were completely wrong. Cárdenas did not claim to be a maximato, although he was attentive to what was happening and tried to preserve what he had done. This placed him squarely in politics. In reality, Lázaro Cárdenas was very present in the political life of the country practically until his death, but Ávila Camacho and the other presidents did what they wanted. And Manuel Ávila Camacho was not a softie either, even though his emotional outbursts might suggest so. “A flirtatious woman tends to be a whore, and a good man tends to be an idiot,” says the popular expression, but the “gentleman president” from the beginning showed signs that he could not even remotely be considered good-natured or clumsy.

Among his first measures was the suppression of the military sector of the official party. There were real caciques in the army, whose command of troops made them prone to revolt. Shortly before, General Cedillo, governor of San Luis Potosí, had been defeated in his bullish adventure. The awareness of limiting the army chiefs was common in those days and the need for the armed forces to become professional and for the presidents of Mexico to be civilians was in the air, something that Cárdenas would have gladly satisfied if circumstances had permitted it. In a certain way, choosing Ávila Camacho was already a step in that direction, since Don Manuel did not distinguish himself in command of troops and his military career had to be traced among the administrative areas.

In 1940, the country had 19.6 million inhabitants, distributed mainly in the countryside and inland cities. But Mexico City was the unequivocal center of national life. For example, Leon Trotsky lived there. One day, he saw, terrified, a commando that included the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros attack his house and burst into his bedroom with bullets. Old Leon saved himself by diving under the bed, but shortly afterward his secretary's boyfriend, Ramón Mercader, or Jacques Mornard, killed him with a pickaxe. Siqueiros was arrested, but he always denied his involvement.

These two, and José Clemente Orozco, had already painted the core of their work and perhaps as a reflection or consequence of the changes that were beginning in Mexico, muralism, more identified with the active stages of the Revolution, began to decline, and with it began the departure of the Mexicanist current: cultured women with shawls, chongos and indigenous dresses (Frida Kahlo, of course, in Tehuana). It had been the first time that for a period of time the Indians and their culture were appreciated: the greatness of their past, the achievements of their civilization, the archaeological pieces, the masks and so on. In its place, a cosmopolitan tendency began to emerge, which meant the resounding triumph of intellectuals such as Alfonso Reyes and the Contemporáneos, who went from the “opposition” to full power in the so-called Republic of Letters. In painting, Rufino Tamayo and Juan Soriano first began to gain strength, followed by Carlos Mérida and Pedro Coronel a little later. Except for the later work of the same three great artists, and of Juan O'Gorman and Chávez Morado, those who joined the so-called Mexican School of Painting were unaware that they had climbed onto the worst possible bandwagon and that their destiny would be limited to painting murals in municipal presidencies.

Surrealism also gained frank legitimacy, and in 1940 a great International Exhibition of Surrealism took place at the Mexican Art Gallery, with the presence of the eminent guru André Bretón, who saw surrealism in every Mexican cactus, which allowed him to issue his famous dictum: “Mexico is a surrealist country,” which was followed, years later, by the also famous joke that, in effect, here Kafka would be a writer of customs.

In that same year, 1940, Malcolm Lowry left the country, amidst incredible (surreal) bureaucratic obstacles, without knowing that eight years later he would return to Mexico and this time things would be worse for him. He already had the first manuscript of Under the Volcano in his suitcase . But the great novelty in Mexico, besides reading Papini and swimming in the Deportivo Chapultepec, was the presence of the Spanish Republicans (Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez, Pedro Garfias, Enrique Díez-Canedo, José Moreno Villa, Wenceslao Roces, among others) that Cárdenas had welcomed a year earlier. With them, the Casa de España was formed, which in 1940 became El Colegio de México. The purpose of this institution was to “create the intellectual elites of Mexico.” The Colegio was directed by Alfonso Reyes, of whom the joke was made: in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is Reyes. The teachers were paid 500 pesos a month and among the most famous founding students were the brothers Pablo and Henrique González Casanova, the historian Luis González and the scholar Antonio Alatorre.

At the antipodes, Oswaldo Díaz Ruanova records in his book Los existencialistas mexicanos that José Revueltas led lively gatherings at the Rendez-vous restaurant. Revueltas was 27 years old in 1941, when he published his novel Los mu ros de agua , based on his own experiences in 1934 in the Islas Marías prison. Revueltas' literary start was dazzling; after Los paredes he won an international prize with his hallucinating novel El luto humano (from which, without a doubt, Juan Rulfo drew) and consolidated his exceptional quality with the stories of Dios en la tierra . Other very solid young writers were those of the magazine Taller , especially Efraín Huerta and Octavio Paz, both revolutionary poets. Paz had even sung to the Spanish republicans in the Civil War. Huerta, for his part, was a supporter of a Dionysian idea of the Revolution, and already from then on he was enthusiastic about the intoxication of women and alcohol. Soon the two poets would diverge their paths: Paz published Entre la piedra y la flor in 1941 ; later he would return to Europe and develop as an intellectual of the highest level. Huerta would remain in Mexico City and would be the home of poetry linked to the people.

In 1941, the poet Xavier Villaurrutia offered Décima muerte , and Carlos Pellicer Recinto y otras imágenes , but the great novelty in the national panorama was the beginning of the anti-communist furor. In January, the ex-president Abelardo Rodríguez openly launched himself against “social experiments based on exotic ideas”. Marxism-exoticism had been born, whose ghost would be the food of official and business speeches for decades.

In reality, the anti-communist attacks had little ideological basis (the “McCarthyist mystique” had not yet been born) but rather they concealed attacks on Cárdenas and what were considered his forces, especially Vicente Lombardo Toledano and the five little wolves of the CTM , who, due to their embeddedness in the system and their capacity to stop or hinder production, represented a real danger. The aim was to dismantle the power of the official left.

PRM ’s labor sector was dominated by the CTM , which was in the hands of Lombardo Toledano and the five little wolves, so called because in 1929, during the heyday of Luis N. Morones and the Mexican Regional Workers Confederation ( CROM ), Fidel Velázquez and his comrades Fernando Amilpa, Jesús Yurén, Alfonso Sánchez Madariaga and Luis Quintero left the great central. “The CROM has the characteristics of a gigantic oak tree,” Morones sang, inspired, “with strong and large roots and a gigantic trunk: from that trunk five miserable worms left for unknown directions.” The response was not long in coming: “You fool, Morones, who in your feverish imagination see worms… What you call worms are five little wolves that soon, very soon, will eat the chickens in your yard.”

In 1941, it was clear that the prophecy of the little wolves was going very well. In February, during the II Congress of the CTM , Vicente Lombardo Toledano punctually left the general secretary and gave the post to the old milkman Fidel Velázquez, who said before President Ávila Camacho: “I am not a communist, but I admire the communists because they are revolutionaries like me and like all the members of the CTM . Lombardo, who so successfully and so intelligently directed the CTM , knows that we are sincere, and he also knows that we can direct the organization, direct it according to its guidelines, because he is not leaving the Confederation, he will not be able to leave because we will never let him go, as we will not let him go now.” The unanimity in the applause for Lombardo was the same with which he was expelled from the CTM years later.

The first thing Fidel Velázquez did was to guarantee that he would support the president. The Lobitos, like their former boss Lombardo Toledano, were not thinking of carrying out an ideological struggle, nor were they even concerned with defending the workers; rather, what they intended was to preserve as much as possible and strengthen that support through total collaboration with the new president. The latter, for his part, was not so sure, and just in case he presented reforms to the Federal Labor Law to tighten the regulation of the right to strike, to punish illegal strikes and wildcat strikes, and to contain violence in the life of the unions, since groups of gunmen frequently forced terrified workers to join the CTM .

In addition, Ávila Camacho promoted the emergence of the Renovación group in the Chamber of Deputies, where the left had a majority (in the Senate, however, the balance of forces favored the right). This group began to launch strong attacks against the Secretaries of State identified with Cárdenas. The military deputy Enrique Carrola Antuna denounced that the Ministries of Education, Communications and Labor were in the hands of communists. The press supported him energetically. Carrola later intensified his attacks on the Banco de Crédito Ejidal: “Ninety percent of the personnel,” he warned, scandalized, “sympathizes with communism.”

In May of that year, the press was up in arms because striking students at a teacher training college in the state of Guerrero had burned a Mexican flag to display the red and black flag of the strike. Both the federal and state governments ordered investigations and found out that, of course, no flag had been burned, but also that the communists, in this case the militants of the Mexican Communist Party ( PCM ), had control of the school. In any case, Deputy Carrola had already asked for Sánchez Pontón's dismissal from the SEP .

Although in his report of September 1st Ávila Camacho made it clear that he would not ask his ministers to resign because of pressure from social forces, on September 10th Sánchez Pontón presented his resignation, “for health reasons.” It was the opportune moment to begin the educational “rectification.” The new secretary Octavio Véjar Vázquez, from the start said that he would not allow exotic ideas to predominate in the teaching plans and that education should have a spiritual purpose; he accepted that religion and national traditions were links of nationality, recognized the role of the family as the main educator and in this way opened the royal road to private education.

The events at the SEP delighted the business and official right, and they celebrated by demanding the total repeal of Article 3 of the Constitution. In several cities there were demonstrations of thousands to protest against socialist education (40 thousand people in front of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City). In reality, Ávila Camacho was dying to get rid of socialist education, but he was not going to give in to the pressures of the right because every particle of power he lost would fatten his opponents; Furthermore, it was a question of asserting authority, and that is why he announced that he did not intend to repeal the constitutional precept but rather regulate it, even though that required acts of arduous rhetorical balancing act in order to be able to preserve the terms “socialist education” while dismantling it and turning a blind eye to the schools that various religious orders were preparing to offer to the upper middle class and the rich of the country: Lasallians, Marists and Jesuits, mainly.

Once Sánchez Pontón was eliminated, the Secretary of Communications, Jesús de la Garza, had also been the target of tenacious attacks from the right, and he also ended up resigning. The president wanted to make a fortune with this move and took advantage of the trip to fulfill the whim of his brother, who always wanted (apart from being president) that position. Maximino Ávila Camacho took office with an escort of 50 cars and motorcyclists, burst into his offices followed by two aides armed with Thompson machine guns, and only afterward did it occur to him to protest as Secretary of State before the president of the republic, his younger brother.

In 1941, the United States entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Bay, and this precipitated peace with the neighboring power. All previous claims were settled, the United States agreed to compensation for the expropriated oil companies, and Mexico, in turn, agreed to help it, and it was granted access to credit systems after years of being declared insolvent. For the first time in history, the presidents of Mexico and the United States met on Mexican soil, which would become common and even routine practice in subsequent years. In all these negotiations, Foreign Minister Ezequiel Padilla played a leading role, which fueled the presidential ambitions he had already cultivated.

The proximity of the war had an immediate effect in Mexico. Both chambers tried to stop the left-right disputes and the Antifascist Parliamentary Committee was formed. Vicente Lombardo Toledano organized antifascist rallies in support of the government in which he attacked the mainstream press, the PAN and synarchism.

However, the need for unity due to the war did not prevent Ávila Camacho's first confrontation with the private sector, on the occasion of the reforms to the Chambers Law. Until then, the Confederation of Chambers of Commerce was dominated by that of Mexico City. As it was not convenient for the president to deal with a single employers' front, which was economically very powerful and in the hands of an extremely conservative sector, he proposed separating the merchants from the industrialists, and the latter from each other. In this way, in addition to the already existing Confederation of Employers' Chambers (Coparmex), the confederations of Chambers of Commerce (Concanaco), of Industrial Chambers (Concamin) and of Transformation Industries (Canacintra) emerged.

At the end of the year, the Ávila Camacho government made it clear that in order to satisfactorily change the Party of the Mexican Revolution, it was not enough to eliminate the military sector. The workers' sector still had a lot of strength, and it was necessary to rein it in. The peasant sector served as a counterweight, since the CNC was easily manipulated because the peasants were always more controlled. But it was not enough. It was necessary to strengthen the popular sector, which was very weak due to the heterogeneity of the forces that comprised it. Several senators, duly instructed, began to ask for the creation of a strong popular sector. This would be a sector of the stature of the workers and peasants, but its undisputed leader had to be President Ávila Camacho. During 1942 work was done on this project, until the National Confederation of Popular Organizations ( CNOP ) was established in February 1943.

Just as nationalism lost ground in painting, something similar occurred in music. The great nationalist, inventive and imaginative current of Silvestre Revueltas (who died in 1940), Carlos Chávez, Blas Galindo and Pablo Moncayo (in 1944 he managed to premiere, with great success, his Huapango ) began to decline in favor of the compositional patterns of the then quite mature international avant-garde, and the new authors, who really stood out until the fifties and sixties, were Joaquín Gutiérrez Heras, Rafael Elizondo, Mario Kuri, Jiménez Mabarak, Miguel Bernal, Armando Lavalle, Raúl Cosío, Jorge González Ávila, Leonardo Velázquez, Manuel Henríquez, Héctor Quintanar and Julio Estrada.

In literature, the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists, which had caused so much noise in the previous decade, disappeared from the map. The stridentist movement was also a thing of the past. On the other hand, the presence of José Vasconcelos in the National Library caused a sensation; to hear him meant to be in front of “the intelligence of the angels,” considered Oswaldo Díaz Ruanova. But the one who ruled the intellectual life was Alfonso Reyes. José Gorostiza and Jaime Torres Bodet continued to climb the official ladder. Novo did his extraordinary journalism and also worked in advertising, with “the boss Augusto Elías.” Jorge Cuesta died in 1942, and his terrible death still makes one’s hair stand on end: the master emasculated himself after a frustrated siege of his own sister (Elías Nandino version). Octavio Paz, in 1942, published A la orilla del mundo . Xavier Villaurrutia dedicated himself to the theater and wrote his incredible décimas and hendecasyllables.

In 1942, Mexican cinema was booming. The big phenomenon of the year was the appearance of María Félix, who filmed El peñón de las ánimas alongside Jorge Negrete. The singing charro was undoubtedly the king of the cinema, the most popular, among other things because of his relationship with Gloria Marín, and he was famous for being bossy and arrogant. María Félix, on the other hand, came when she wanted, obeyed no one and did whatever she wanted. Therefore, her fights with Jorge Negrete were legendary. Later, as expected, they got married. The following year, María Félix's dizzying fame would be consolidated with the release of Doña Bárbara , a film version of the novel by Rómulo Gallegos. At that time, making a film cost 350 thousand pesos. Cinema was a big business and the film studios kept churning out films with the hottest actors: Arturo de Córdova, Pedro Armendariz, Emilio Tuero; the Soler brothers Fernando, Andrés, Julian and Domingo; Joaquin Pardave, Cantinflas, Isabela Corona, Maria Elena Marques, Dolores del Rio, Andrea Palma and Sara Garcia.

It was the famous Golden Age of National Cinema, when the domestic market had been conquered and the Central and South American markets were also dominated. The main stars embodied archetypal forces and were true vessels that received the projections of countless people. The mythical relationship was genuine, much more so than now, because the level of collective consciousness was considerably lower, at least in general terms, and unconscious forces manifested themselves with much greater fluidity. Films were made with what can now be considered true innocence, with the enthusiasm of a frankly successful first era. The industry was not as contaminated by the vulgarity of the search for maximum profit through minimum investment, as occurred from the fifties onwards. Film people sought to make money, and a lot of it, but they also wanted to express themselves, and that is why there were films that managed to be sinister and sublime at the same time: the innocence of a 10-year-old whore, Revueltas would say.

In 1943, Emilio Fernández filmed María Candelaria , an undisputed box-office hit, and Flor silvestre , one of his most significant works. El Indio undoubtedly contributed to the mythologisation of Mexican cinema in the 1940s. His films were box-office successes and won important awards at the most prestigious European competitions, where the image that El Indio gave of Mexico was greatly appreciated, since it reinforced the fiercest stereotypes of the “land of death, the infernal paradise” that many foreigners liked and still like to cultivate. El Indio also became an artistic vehicle for the Mexican Revolution, which in the cinema took on a dramatic and aesthetic image, thanks to the carefully illuminated and technically impeccable shots of Gabriel Figueroa.

In popular music, during the Avila Machado era, the great success of Agustín Lara, the poet-musician, who reflected the last great manifestation of the old bohemian and “proudly corny” romanticism, continued. Lara’s gift for versifying and creating melodies was extraordinary, and his sensitivity managed to capture that of a good part of the nation, hence his success. A marijuana addict, a singer of whores and sordid cabarets, Lara also reflected the Zeitgeist by singing about the landscape and the cities for the excellent reason that it came naturally to him. Lara reached the height of popularity when his romance with María Félix became famous. This new version of Beauty and the Beast, or the Triumph of the Spirit over Matter, shocked the Mexican public. With the leader Lara also came the great popularity of Pedro Vargas, Ana María González and Toña la Negra, his interpreters. Equally important was the presence of María Luisa Landín, with her enervating boleros, the Martínez Gil Brothers and the extraordinary ranchero singer Lucha Reyes, the highest ceiling that vernacular Mexican song has ever reached. Lucha Reyes was a woman with hair on her chest who often sang songs for men (“if you have curves I have a slide, let’s see if that Cuquita wants to slide”), because she contained within herself all the rough Mexico that was ready to eat Mexican eggs sprinkled with gunpowder for breakfast and that didn’t take off its gun even to sleep (“if they throw a lasso at me, I respond with bullets”); but she also extracted very fine aspects of the popular soul, as in “Por una mujer ladina” or “La Panchita” (by Joaquín Pardavé), or, if not, she rescued a luminous country air, with all its rich colloquial language (“I feel lacia, lacia, lacia, it’s that you bring me agorzomada”). Lucha Reyes' vigor, vitality, and charisma only found something equivalent a little later, with the appearance of Pedro Infante. Reyes (not related to Don Poncho) committed suicide in 1944, and there were persistent rumors about the involvement of the Terrible Chief Maximino Ávila Camacho, who was also a famous womanizer. But, as we know, rumors and gossip are inherent to popular idols, since being recipients of the projections of thousands of spectators, they are unbeatable spaces for the emergence of all kinds of legends (such as that of Chamaco Domínguez, author, it was said, of almost all of Agustín Lara's songs).

The national cinema sparked the creativity of several composers, especially the duo Esperón and Cortázar, who composed excellent songs for films. Ernesto Cortázar, before teaming up with Manuel Esperón, was part of the excellent group Los Trovadores Tamaulipecos (Lorenzo Barcelata, Agustín Ramírez, Cortázar, Planes and Caballero), who, like Guti Cárdenas, made very successful recordings in New York in the early 1930s. And since we are on the subject of gossip, it was said that Lorenzo Barcelata had acquired, for a carton of beer, the lyrics and music of the famous song “María Elena” from its true author, the Guerrero native Agustín Ramírez, who also composed “Acapulqueña”, “Por los caminos del sur”, “Caleta” and “La sanmarqueña”.

Another who was at the top was Cantinflas, who in the previous decade caused a sensation first for his performances in the tents and then for the cinema: Águila o sol and Ahí está The detail was the springboards that allowed him to become an absolute celebrity. As we know, the ability to talk and talk without saying much was so decisive that the term “cantinflismo” was born. Of course, this type of speech was the exclusive domain of politicians, but none of them enjoyed the popularity of Cantinflas because no one had his grace and wit. Cantinflas represented the “pelado”, the screwed-up guy, and as long as he maintained his connection with the people, the comedian was incomparable. Unfortunately, not only Mario Moreno changed his social status, but his character did too, and at that time began the spectacular qualitative decline of Cantinflas, who in the fifties was only a poor imitation of himself and a sad bourgeois clown. But at the beginning of the forties Cantinflas was still the one in hilarious films like El gendarme desconocida or Sangre y arena . The other comedians recognised Cantinflas' abilities and people like Manuel Medel, El Chicote, Chato Ortín and Panzón Soto admitted that something different had arrived that epitomised what they had done and that had a great influence on new comedians like Jesús Martínez, Palillo , who left Guadalajara to triumph in the big tops of Mexico City until he arrived to stay at the Follies theatre in the middle of the decade. Palillo, following in the tradition of Roberto Soto, Panzón, railed against the government, against the public starvers and looters, and as in those years the shortage of food began to cause havoc, Palillo always had material for his philippics.

In the first half of the 1940s, Francisco Gabilondo Soler, Cri Cri, who had begun his fertile and beautiful musical career in the previous decade, also shone enormously. By that time, Cri Cri had already composed several of his extraordinary hits in children's songs, such as "El ratón vaquero" or the prodigious "El comal y la olla." Of course, Cri Cri had a first-rate melodic capacity, as well as a mimetic disposition to recreate airs or tunes from other countries. His songs condensed all the tenderness, freshness and innocence that represented the best of Mexican families of the time, but, in addition, in the work of Gabilondo Soler a radiant Mexicanness stood out, which rescued popular atmospheres, colloquial verbal wit and also malice and intelligence. Cri Cri fed the childish souls of children in the thirties, forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, and even in the eighties, already very old, Cri Cri was still alive in many Mexican families, as confirmed by the fact that his main records continued to be reissued. Already in his eighties, Cri Cri had the humor and energy to sing in public extremely funny versions of “Negrita Cucurumbé” or “El negrito Sandía”. Cri Cri’s work is impeccable, well-rounded and brilliant, to the point that he even survived a horrendous tribute that, presumably with good will, was given to him by the Televisa consortium in the eighties, when we had to choke on the “cultured” versions of Cri Cri’s songs sung by ( of all people ) Plácido Domingo and Mireille Mathieu.

In 1942, while work continued to form the CNOP , the struggles between the left and the right also continued intensely, which, in reality, rather represented the efforts of President Ávila Camacho to have total control of the country, since what can be considered the traditional right by then no longer doubted the benefits of the regime and was busy doing business with great pleasure.

A major problem remained Lázaro Cárdenas. Beginning in September 1941, the government considered the entire strip of states with coasts on the Pacific Ocean to be a militarized zone. Ávila Camacho appointed General Cárdenas commander of this enormous militarized region. However, in February 1942, the governor of Sinaloa called a meeting of governors of the Pacific states, and this was seen as a move by Lázaro Cárdenas to gain influence in all those states (from Sonora and Baja California to Chiapas). The newspapers strongly attacked the board of governors, and gossip ran high enough that Cárdenas decided not to attend the meeting, which, without him, was a failure.

The presence of Cárdenas was very important given the attacks that the official left was receiving since the beginning of the anti-communist campaigns and the demonization of “exotic ideas.” The offensive was so dense that Vicente Lombardo Toledano came up with the idea that the working class should temporarily renounce the right to strike, since these were “not times to sharpen the class struggle.” The unions, of course, were horrified by the idea, but, just in case, they did not say anything. But several factors led them to adopt Lombardo’s idea. On the one hand, a futuristic struggle for the presidency of the Republic was already visible. Ezequiel Padilla was capitalizing to the maximum on his preponderance in international issues, decisive given the context of the world war. But also fighting for “the great” was Maximino Ávila Camacho, who launched frequent attacks against Cárdenas, the CTM , Lombardo and any leftist bastion. Maximino had amassed a large fortune to finance his presidential ambitions. He had partnered with the Swedish millionaire Axel Werner Grenn, and from his position in Communications and Public Works he had a large stake in profiting from contracts for road construction, urban improvements in the Federal District and irrigation projects. And Miguel Alemán, the Secretary of the Interior, took advantage of the network of political influences that his position represented to strengthen himself throughout the country. Alemán was very careful that the benefits that arose from the left-right struggle not only benefited the president but himself as well.

It was soon discovered, for example, that the three presidential hopefuls were behind the attacks on Cardenas by the famous junta of governors. Both Padilla and Alemán had fomented the rumors and criticism in the press, and Maximino, who was already famous for his anti-communist crusade, not only said that these Cardenas meetings were agitations but also energetically blocked attempts to call another similar meeting with the governors of the northern states.

In May, the Germans sank the tankers Potrero del Llano and Faja de Oro , which precipitated Mexico's entry into the war. To begin with, war was declared on the Axis and the United Nations Pact was signed. The president declared a state of national emergency and, of course, called for maximum unity and collaboration throughout the country. Because of the war, the Law of Compulsory Military Service, which affected 18-year-olds, came into force in August 1942, and on November 12 the registration of conscripts of the famous class of 1924 began. There were even blackouts and rehearsals for war emergencies that greatly excited the population. And Lázaro Cárdenas was named Secretary of Defense.

This temporarily halted the attacks on the workers and their offensives against the Secretary of Education, Octavio Véjar Vázquez, who, undaunted, was eliminating communists from the teaching profession. On May 26, the CTM , through Fidel Velázquez, proudly proposed the workers' commitment to renounce the sacrosanct right to strike, although it was careful to ask for "employer reciprocity to find fair solutions to labor conflicts." The government and private enterprise, as was to be expected, applauded this "extraordinary sacrifice of solidarity by the workers," and both Lombardo and the leaders of the main unions breathed a sigh of relief at seeing that the "anti-communist" offensive was somewhat subsiding.

This was taken advantage of by Fidel Velázquez to begin what would be a long and disastrous reign over the workers.

In 1942, Fidel had to leave the post of general secretary of the CTM , but the leader resisted until the very end. Since non-reelection was sacred, Fidel Velázquez hid his pretensions of perpetuating himself under the proposal that his mandate be “extended” for two more years; in other words, he asked that the term of the general secretary of the Confederation be four years, and not two. Several labor leaders opposed Fidel’s plans, shouting “I know my people, my lieutenant,” but the wolves moved their pieces to eliminate their opponents and finally achieved the extension of the general secretary’s mandate.

Meanwhile, to somewhat mitigate the beatings on the workers, President Ávila Camacho continued work on the creation of one of his major projects and his most important achievement: the Mexican Social Security Institute, which was initially very problematic. The workers, contrary to expectations, rejected it, because they considered the contributions they had to pay to “insure themselves” to be too heavy. The employers, for their part, flatly refused to pay them.

They were too busy making money to think about sharing it. By 1942, exports of raw materials had increased substantially due to the war, which later allowed them to sell textiles, chemical products and other products as well. A lot of money was coming in, and with it machinery was bought to develop the industry. But while many saw enormous economic benefits, the great majority continued to suffer in order to survive. It was difficult to contain popular discontent. By then it was clear that the shortage, which had begun in 1941, was increasing alarmingly a year later. The private sector had also taken advantage of the workers' renunciation of the right to strike and was dedicated to making "staff adjustments" and to hoarding and hiding basic products in order to increase their price. In addition, the bosses were happily swimming in the corruption of the system to do business. The country's main political forces (the president, the PRM and the candidates Maximino, Alemán and Padilla) supported them in everything and the only adversaries (Cárdenas and the leftists) were firmly contained by the government itself. The rich could not only invest profitably in whatever they wanted and had in their power numerous and important exports abroad at war, they also had all the public works undertaken by the government and which usually passed through the hands of Maximino Ávila Camacho.

Under these conditions, the employers were able to harden. The workers had formed a unifying Workers' Pact which later became a National Workers' Council, which sought to unify all the workers' confederations in a single central and which brought together Fidel Velázquez and the old Luis N. Morones, still head of the CROM . Both complained that the employers did not adhere to the policy of unity, but rather took advantage of the conditions to enrich themselves outrageously. The president tried to form a Workers-Industrial Pact to discipline the employers and merchants a little, and thus stop, or calm down, the hoarding, the concealment and subsequent price increase of food, the suspension of staff cuts and the closure of companies without prior notice to authorities and unions.

The private sector rejected the Pact and made it clear that any condition imposed on them was unjustifiable, divisive and unpatriotic, since they identified themselves remorselessly with the country (if the government did it, why not them?). The most they managed to do was to propose a Single Clause Pact, which stipulated the need to “put efforts at the service of the country,” and we already know what they understood by country, “and to preserve the union within the legal precepts and contractual norms,” which of course, at that time, entirely favored them, since there was not even a legal strike to fear. They called this the National Employers’ Council, and Aaron Saenz, leader of the bankers, was named president. Avila Camacho accepted this arrangement reluctantly and was content with the employers participating in the Supreme Defense Council, made up of representatives of all organized social forces. Their activities consisted of guiding and developing the activities of war, military defense, economic, financial, commercial, agricultural, market, legal and national spirit. All this sounded very nice but of course it did not stop the high cost, the artificial scarcity and the free rein given to people with money. But, yes, the respectable public was able to enjoy the spectacle of seeing together the former presidents Plutarco Elías Calles, Pascual Ortiz Rubio, Abelardo Rodríguez, Emilio Portes Gil and Lázaro Cárdenas.

In 1942, the fighter from Morelos, Rubén Jaramillo, made his public appearance, but was murdered during the government of López Mateos. In 1942, the manager of the Zacatepec sugar mill, created by Lázaro Cárdenas, was mired in corruption and had terrible relations with the sugarcane growers. Jaramillo, who led the peasants, demanded that the manager be held accountable. But the manager enjoyed the full support of Governor Elpidio Perdomo, who made his delicate pronouncements heard: “Hit the scumbags hard.” From then on, the repression of the sugarcane growers began and the harassment forced Jaramillo to go to the mountains with 90 men and from there he began his guerrilla activities. “He was just defending himself,” said the peasants, and they helped him in any way they could, so Jaramillo successfully evaded the troops that sought to arrest him.

But Jaramillo was not a real problem. What worried Ávila Camacho was how to curb corporate greed and the resulting high prices. It was clear to the people that the government was incapable of containing shortages and price increases, no matter how much it talked about national unity and solidarity.

To distract themselves from the high cost of living, apparently inherent to the country's so-called economic growth, the people relied on tents and sports. The vicious circle of boxing formed by Chango Casanova, Joe Conde and Juan Zurita excited fans. The bullfighters Armilla, Soldado and Silverio Pérez (who later dedicated himself to politics) were also admired. In soccer, the space was dominated by Chivas de Guadalajara, Asturias and Club España. The famous match between Asturias and Moctezuma in 1942 cost two pesos per seat. In baseball, the Industriales de Monterrey and Águila de Veracruz were extremely popular.

In the city streets, children played the traditional “cascara” or street soccer, and others, a few, played baseball or “tochito.” But almost everyone had fun jumping over the plane (Cortázar’s hopscotch, only without the “sky”), playing “encantados,” hide-and-seek, “burro corredo” or “burro dieciséis” (“sixteen, boys, run!”), playing “cebollitas” or its thicker version: “tamalada.” Middle-class children already showed influences from the United States when playing “estop” or asking for “taim.” Those who could traveled around on their bicycles, donkeys, or bürulas. The kids already read “monitos” or “cuentos” translated from English. As Elena Poniatowska states in “La Flor de Lis” , Little Lulu , Periquita and Lorenzo and Pepita were already in circulation , but in reality, American comics would not infest the newsstands until the fifties. The strong Mexican comic strip was in Pepín and Chamaco . In the first one, La Sagrada Familia Burrón appeared , by Gabriel Vargas, more caustic and anarchist at that time, because the Burrón family (doña Borola and don Regino and their bodoques) were extremely poor, they lived in a miserable neighborhood in the center of the city (the “Callejón del Cuajo”); this comic strip presented excellent drawings, with sometimes sincerely inspired shots, and the texts abounded in criticisms of the authorities. Over time, La Familia Burrón moved towards the middle class, but it never made a fool of itself and never lost its wit or virulence.

In Chamaco people also read the terrible dramas of Yolanda Vargas Dulché (who would live one of them in 1989), and Los Supersabios , by Germán Butze. In the fifties, Rolando el rabioso would appear . The main newspapers at that time were El Universal , directed by Miguel Lanz Duret and with articles by Alfonso Junco, Mauricio Magdaleno, Carlos González Peña and Antonio Caso; Excélsior , by Rodrigo del Llano, in one of his most right-wing periods; El Nacional , official (“in its golden age”, said Daniel Cosío Villegas), gave opportunities to the young Ermilo Abreu Gómez, Raúl Noriega, Fernando Benítez, and gave space to the Spaniards Margarita Nelken and Juan Rejano; The latter produced a cultural supplement of excellent quality and, together with Romance , the literary tabloid edited by Rafael Giménez Siles, served as a starting point for the cultural supplements of the following years. Also in circulation were Novedades , El Popular , dominated by the Lombardist left, and La Prensa . The magazines with the largest circulation were Hoy , Mañana , Jueves , Voz and Revista de Revistas.

In radio, after XEQ , the most powerful station was XEW , which in the previous decade had played an essential role in the rise of popular idols. Radio sets crept in wherever electricity reached, and radio stations from the interior began to spring up everywhere, but Emilio Azcárraga’s XEW soon achieved a reasonably national coverage and was undoubtedly the maximum power in radio, transmitting songs, information, interviews and also daily radio soap operas and radio series, which kept people glued to the set. Cri Cri, Agustín Lara or Pedro Vargas were essential parts of radio. In 1940, XEQK emerged , the “exact time of the Observatory of Mexico,” which gave the time minute by minute between very fast mini-announcements.

The American swing and jitterbug craze also filtered through the radio, but Mexico had not yet become Americanized, although of course many people who could afford it preferred to smoke imported cigars, or “faced” ones, like Lucky Strikes, Chesterfields or Camels; those same people drank Coca Cola, listened to Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey, but the vast majority, including the middle class, in the mid-forties preferred Mexican soft drinks: Pato Pascual, Mundet soft drinks, or fruit waters, “from horchata to chia my soul is reborn,” or “excellent Mexican beer,” as Malcolm Lowry said, who knew what he was talking about and did not hesitate to describe Mexico as “rich tequila country.” Pulque was also drunk a lot, and its industry, from the plains of Apam, was still prosperous, since pulque was a symbol of national identity. The infinite variations of corn were widely eaten, such as tortillas, sopes, picadas, tostadas, enchiladas, enfrijoladas, chalupas, tlacoyos, or atoles of different flavors. Pinole was a common delicacy. Chocolate was beaten, sauces were made in a mortar and pestle to obtain adequate oxygenation, tortillas were made by hand and at home, most of the time in braziers and griddles.

Refrigerators were cooled with ice blocks; toilets, when they existed, had the tank at the top of the feed pipe and were chain-operated, and beds had a strict brass headboard. On the streets there were vendors selling sweet potatoes and bananas, alegrías and cocadas, raspados, snow cones, ice cream and paletas (they sold dry ice ), meringues (ready to be thrown in), guajolotes or pípilas; there were also sharpeners, junk dealers, and buyers of old newspapers. There were many coal and petroleum stalls, and the pharmacies were apothecaries, where the apothecary (at the door) maintained a connection with the old alchemists and prepared all kinds of compounds. Small shops predominated, although of course there were already large ones, which, like the bakeries (run by Spanish people), housed stalls selling tamales and atole, pumpkin seeds, roasted corn, vendors of pork rinds, balloons, and a newspaper stand on their sides.

The train continued to be a very important means of communication, but roads and highways were also being built to connect the country; however, there were countless areas that were difficult to access and the journey to them could take many days on mules and in pangas to cross the rivers. Electricity and radio telephony were also gradually spreading (telephones were still relatively few and people knew that the answer was “good”, one of the strangest things in the world, because that was how they qualified whether the reception of the signal was adequate; or “bad” if it was not heard well).

In small towns, people still lived decades ago; the roads were rough, there was no electricity or gas, no radios, and much less cars; people traveled on horseback or in carts, on donkeys or mules; the cinema, a fair or some attraction would occasionally come and life would come alive during religious festivals and with Sunday strolls (“the girls over there, the boys over here, and the dads and moms sitting on the benches,” Chava Flores sang years later); people would also go out to see the profusely, intoxicatingly starry skies and the wonderful shooting stars while people, lying down and in peace, talked; otherwise, at night or on gloomy and rainy days, there would be the narration of legends and fantastic stories, where unreality took the place of honor after its daily devaluation in favor of an overvalued rationality.

In many small towns (and in some not so small ones) more than 130 years after independence, many Spaniards controlled the commerce or the entire life of the town, if they were not held hostage by the local chieftains, imposed through murders, white guards and corruption to buy dangerous men or desirable women. Gonzalo N. Santos was an excellent example of the powerful chieftain who had to be courted by the different governments in the electoral rounds.

More and more cars were seen, and they became so popular that the saying “Mercedes Benz, how much for the Nash?” “Well, sometimes Dodge and sometimes Ford.” “No Fiat?” “No, only Packard.” “Then Chevrolet, your Mercury” was invented (already in these metaphysical themes we must remember the gloss of the film companies: “Don't give me Movietone because if Paramount gives me Twentieth Century Fox, you'll get Metro Goldwyn Mayer for Columbia Pictures”).

In the 1940s, men from the cities wore wide, double-breasted jackets with large shoulder pads and lapels, and equally wide trousers with numerous pleats, but without going to the extremes of the famous Tarzans (“they call them Tarzans, a bunch of lazy people!” sang Lucha Reyes), also called pachucos de la frontera, one of the first clearly countercultural manifestations of such vitality that it would even withstand the interpretive sieges of Octavio Paz a few years later. All men wore hats, whether palm, southern, Texan or felt for city dwellers, “from Sonora to Yucatán Tardán hats are used,” said the slogan, which Alfonso Reyes twisted upon hearing a concert: “From Sonora to Yucatán you can hear Chopán music.” And for many people, an indispensable part of their attire, as vital as their boxer shorts (big, baggy, boxer-style), was the pistol, fusca or matona, an inexhaustible source of jokes. Just like Diego Rivera and Siqueiros, the vast majority carried different models, revolvers or pistols, but they carried guns and often used their weapons. It was an instant reflection of the “rough Mexico” that still swarmed and continued to be a dispenser of machismo. Every now and then there were “de-pistolization” campaigns.

Women also wore an endless variety of hats and followed the fashions of long dresses, with lots of fabric, below the knee, stockings with their proper crease in the back, blouses buttoned up to the neck, because the prevailing morality was “strict”; they wore makeup with taste (rouge on the cheekbones, mascaraed eyelashes, a very red mouth, eyebrows plucked à la María Félix). They read Paquita de Jueves , and most of them dedicated themselves to “household chores,” as was usually stated in official documents.

But what in the seventies would be a strong female presence, in the forties it barely moved. During Cardenismo a group of left-wing women had formed the Frente Único Pro Derechos de la Mujer, which came to house Frida Kahlo, Concha Michel, Adelina Zendejas, Soledad Orozco and Esther Chapa, but the FUPDM was soon absorbed by the PRM and in the years of Avilacamacha, much less propitious, it disappeared. However, the question of women's suffrage, one of the main premises of the FUPDM , had been left in the air.

In early 1943, the country was shocked by the appearance of a new volcano in Dionisio Pulido's cornfield in Paricutín, Michoacán. For days it was the center of the immense, shocking and chilling spectacle produced by explosions and the expulsion of fire, gases, rocks, ashes, a white-hot semi-liquid mass, and lava that flowed at 10 kilometers per hour. At night, in the center of the valley, a resplendent red mountain rose, marked by glowing lines. Numerous researchers from all over the world came to Paricutín to see the phenomenon, about which José Revueltas wrote a splendid chronicle.

In 1943, the CNOP was finally established as a strong sector. It was the ideal vehicle to take seats from the CTM and the CNC in the elections for deputies that would take place in the middle of the year. In addition, the CNOP represented a space for the middle class, which was clearly growing and growing and becoming a unique driving force of the new, frankly capitalist development. It brought together small rural landowners, small-scale merchants and industrialists, cooperative members, artisans, professionals, intellectuals, bureaucrats, and women's and youth groups. Antonio Nava Castillo (who in the sixties would explode in the government of Puebla) was appointed as general secretary, but total control was in the hands of the Avila Camacho deputies. In reality, Avila Camacho established the vital features of the new sector: total subordination to the executive and a tool for various intrigues.

With the CNOP ready, negotiations could begin for the distribution of seats (everyone was sure of winning) in the upcoming legislature. To this end, the three sectors established a “pact of honor” to not invade “zones of influence.” President Ávila Camacho carried out the solemn and transcendental rite of the “palomeo” (a sign of approval next to the name of the proposed deputy), made the list to his very personal taste, and with this the sectors left their grievances. Through the submissive CNOP and CNC , the president kept 120 seats, 21 went to the CTM , which also had no desire to fight, and the rest were distributed among the smaller groups. The ridicule of the day corresponded to the poor Mexican Communist Party, which tried to obtain a PRM seat for the leader Dionisio Encinas, a pillar of Stalinism. To make matters worse, Narciso Bassols left the PCM and formed the League of Political Action, which at least in name managed to get rid of the much-demonized label "communist."

Meanwhile, the National Action Party had just consolidated itself as a right-wing party, as could be seen in its Third National Assembly, where leader Manuel Gómez Morin criticized Ávila Camacho for “fostering accommodating quietism or deceived disorientation and making possible with them the survival of the forces of destruction and corruption.” He also announced that the PAN would participate in the elections.

The PRM was worried: the PAN could fan the flames of Almazanism; after all, things had changed, but for many it had not been for the better: high prices, the concealment of products and speculation were sources of discontent that could be used against the regime. It was therefore decided to remove the flag of high prices from the PAN and the CTM senator Fernando Amilpa was instructed or suggested to hold the Secretary of Economy Javier Gaxiola responsible for all the economic ills of the country. Amilpa, with great pleasure, asked for Gaxiola's immediate resignation.

Everything was in place for the elections. Even the electoral law had been amended, but this, of course, continued to ensure government control over the process. Local authorities would control the integration and purification of the electoral roll, the definition of districts and the designation of polling stations. The provision that the first five citizens to arrive would be constituted at the polling station was also maintained.

The PAN finally presented candidates in 21 districts in 11 states and the Federal District, and claimed to be “strong” in more than 10 states. It called for the elimination of socialist education, effective municipal autonomy, measures against high prices, for the State to arbitrate but not be the owner of the economy, as well as true reforms to the Federal Electoral Law to guarantee free elections. For its part, the PRM considered that the PAN did not deserve the honors of refutation and only dedicated insults, slander and sharp disqualifications to it.

It was not surprising then that on election day there were again attacks on the polling stations and theft of ballot boxes, but these were unnecessary, since the PAN opposition did not try to fight with weapons for the polling stations, and the lack of interest and apathy of the people was immense in almost all of the Republic, which was a deplorable result of the immense electoral fraud of three years before. The fraud in this case rather served to finish designing the composition of the Chamber in the following legislature. There were attempts to subtract seats from the CTM but it managed to maintain its positions. The sessions of the electoral college, however, had its climactic moments.

The most spectacular one occurred when the college gave the seat for the second district of Oaxaca to a candidate who presented himself as an independent because the PRM had taken the fourth district from him to give it to another more influential candidate. The one who had truly triumphed, and from the PRM as well, was Jorge Meixueiro, who, in addition to having the rare triphthong uei in his surname, allowed himself to shock Congress when he went up to the podium and without further ado shot himself there and then.

Meixueiro's suicide, in the end, managed to impose a minimum of sanity on the electoral college, which was forced to open up a little and allow the defense of the disputed cases on the platform. In this way, it had to swallow the speech ("forceful and well-founded," describes it as Luis Medina) of Narciso Bassols, who pointed out truly grotesque irregularities, such as Ávila Camacho himself voting outside of Mexico City due to manipulations in the electoral process. He asked that the voting documentation be reviewed, and the PRM responded that it would never end if they started reading all the voting records. In the end, to demonstrate its power, the government kept "the whole cart" and only gave two seats to "independent" candidates (like the one who caused Meixueiro's suicide). Nothing for the PAN or for Bassols.

The elections and their unedifying and boring results were the setting for protests against high prices, and specifically against Francisco Javier Gaxiola, the Secretary of the Economy. In the press, he was accused of supporting hoarders in order to benefit economically from his family. There were many rumours that Ávila Camacho was behind the attacks on Gaxiola, which, of course, was true: in doing so, the president was drawing a line under Abelardo L. Rodríguez's side, ingratiating himself a little with the suffering leftists, reaffirming his power and surely having a lot of fun.

The CTM organized a demonstration of 80,000 people in Mexico City, and shortly afterwards, in Durango, the mob raided the railway warehouses and looted the corn stored there. This led Ávila Camacho to issue several decrees: “to compensate for the insufficient wages of the workers,” to freeze prices, to control corn stocks and to intensify sugar production. All this, in the long run, proved useless.