Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov

Changing Nomads in a Changing World

Titles of Interest From Sussex Academic Press

Great Scholar, Great Man, Great Friend (Remembering Ernest Gellner)

1. Pastoralists in the Contemporary World: The Problem of Survival

2. Who are these Nomads? What do they do? Continuous Change or Changing Continuities?

3. Being Bedouin: Nomads and Tribes in the Arab Social Imagination

Bedouin and Tribe: Imputed Cultural Identities

4. Coping with Change in Arabia: The Bedouin Community and the Idea of Development

5. Bedouin Settlement Policy in Israel, 1964–1996

6. Continuing Education and Community Development for Bedouin

Continuing Education for Community Development in the Nile Centers

Nile Centers with Bedouin Societies

Specific Seminar Topics for and with Bedouin

Bedouin Participation in Seminars on Community Development

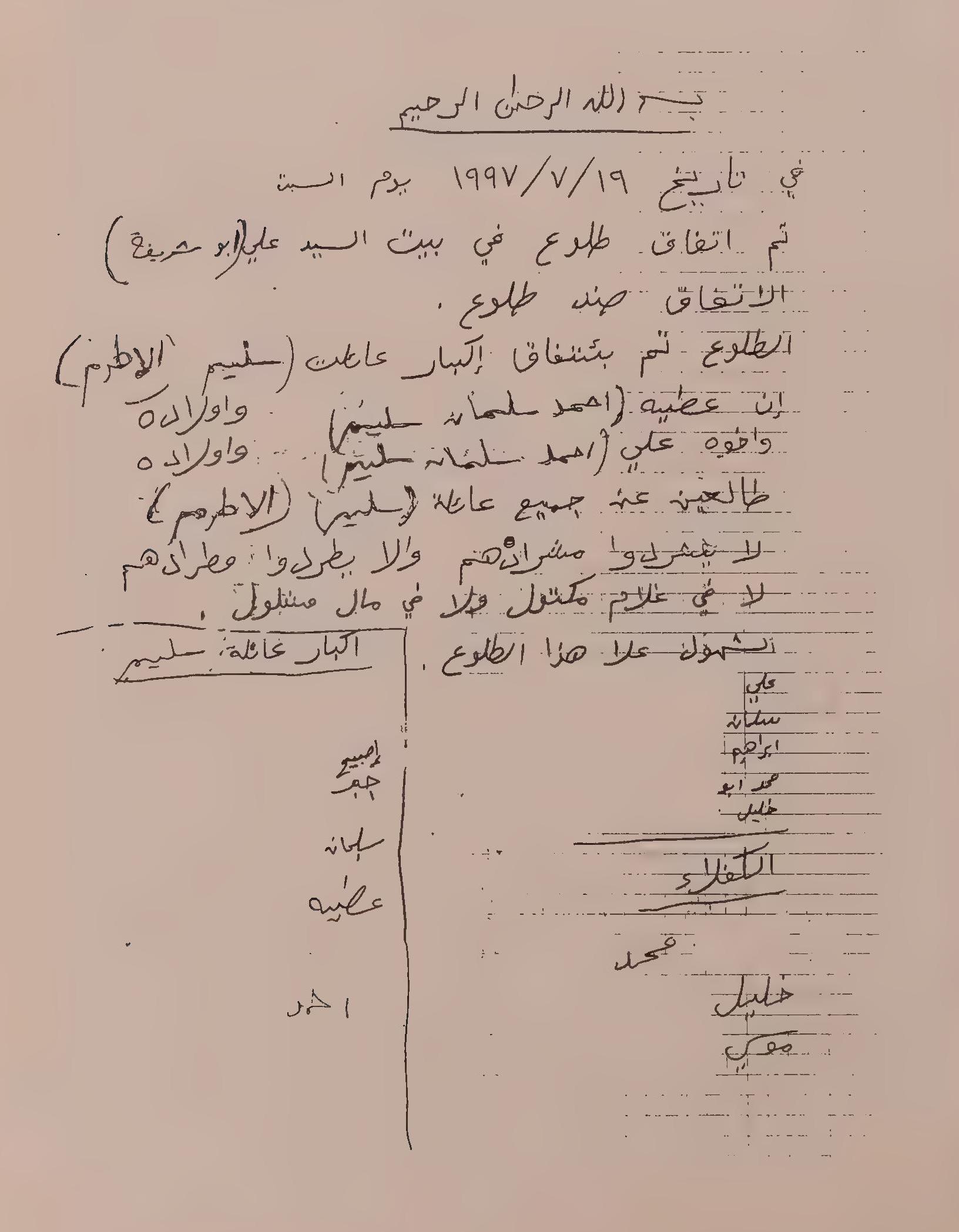

7. The joz musarrib: An Unusual Form of Marriage among the Arabs

8. The Segmentary Lineage System: A Reappraisal

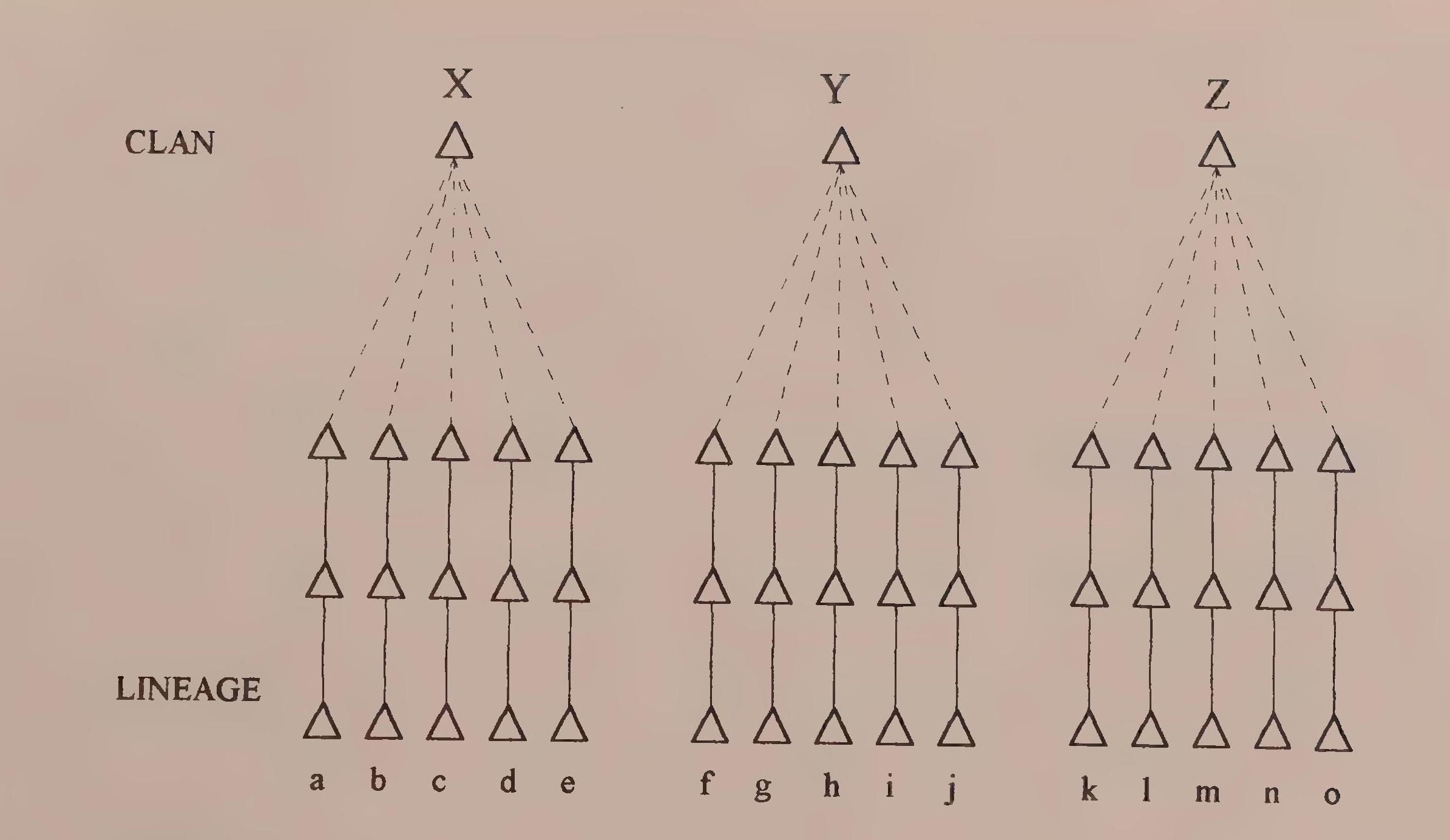

Segmentary Lineage vs. Clan Organization

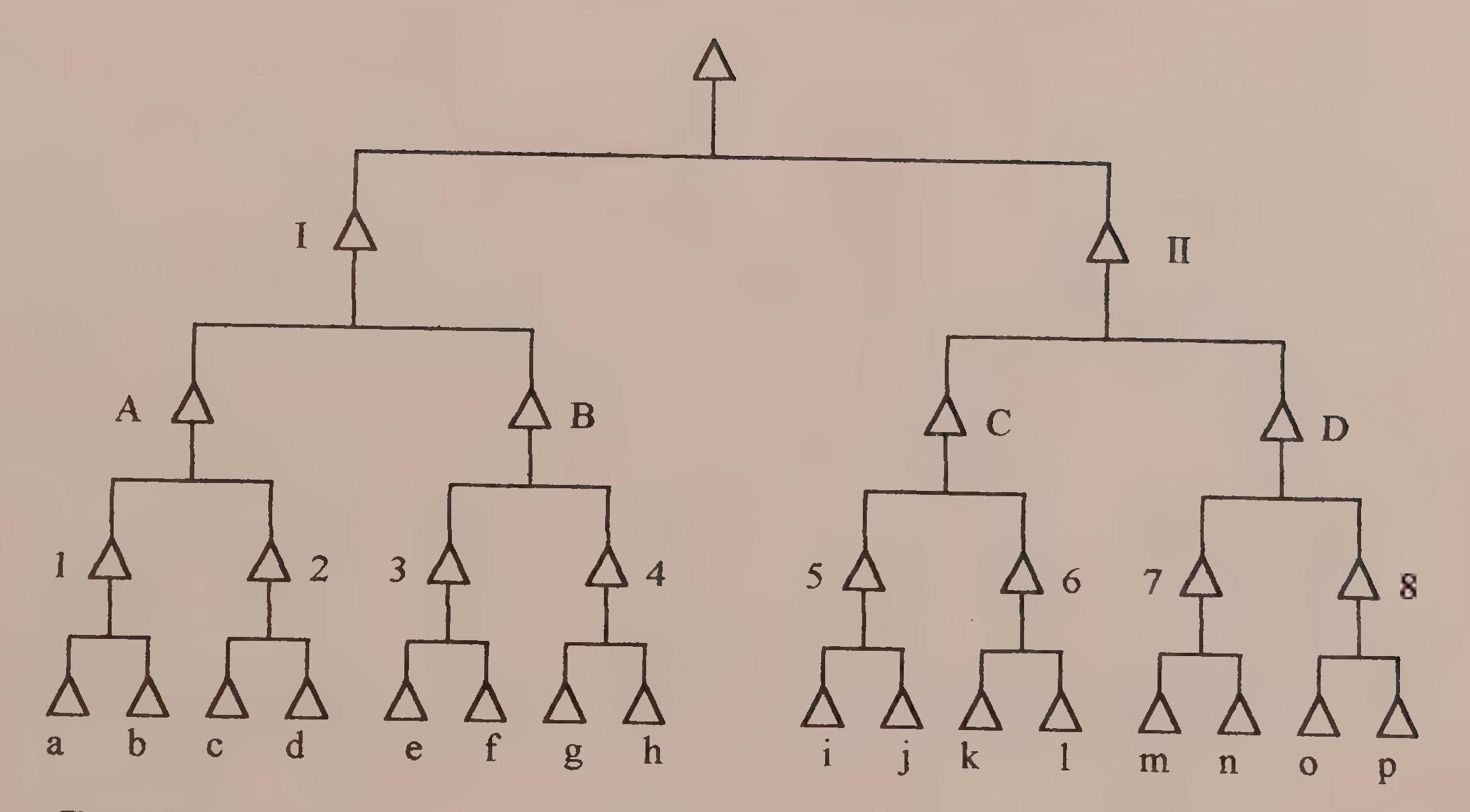

The Formation of Internal Subdivisions

Political Organization and Social Hierarchies

II. Hierarchy and Social Differentiation

III. Tribe, Confederation and State

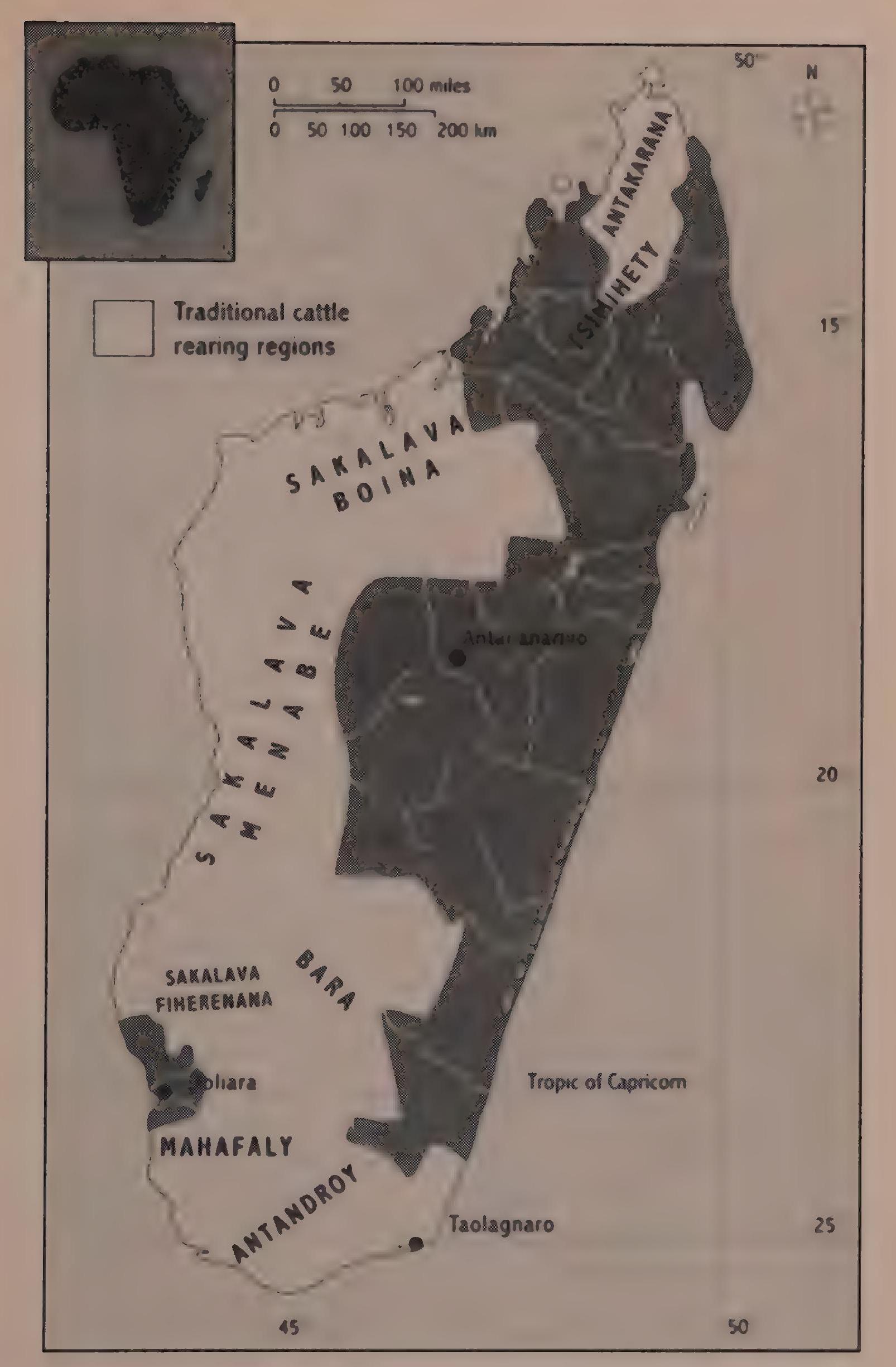

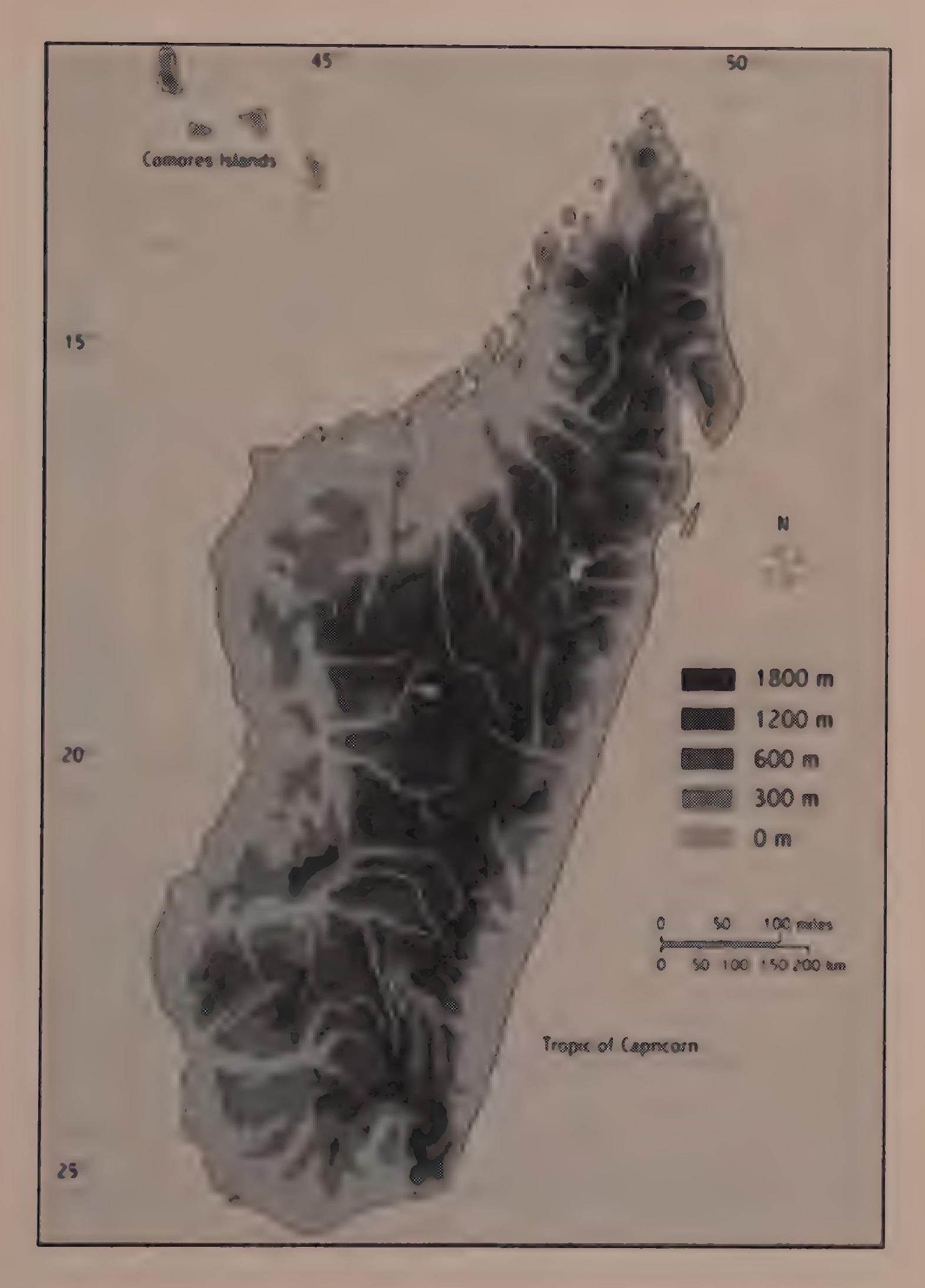

9. The Cactus Was Our Kin: Pastoralism in the Spiny Desert of Southern Madagascar

The Importance of Prickly Pear Cactus

11. The Missing Link: “Badu” and “Tribal” Honor as Components in the Iraqi Decision to Invade Kuwait

Badu and Tribal Arabs, and the Regime’s Power-Base

Tribal Values in the Political Culture of Ba’thi Iraq

Tribal Honor and the Saddam-Glaspie Meeting

12. Preservation and Change in Bedouin Societies in Israel

Attempts at Changing and Preserving Traditional

Marriage Patterns

The Bishac: Increased Use of the Ordeal among the Israeli Bedouin

Institutions: Local Communities

Institutions: Kinship and Redistribution

Institutions and Attitudes: Status Seeking

Management and Market Response

Introduction: A “Subsistence Continuum” in the Arctic

Modern Status of Native Pastoralism

[Front Matter]

Titles of Interest From Sussex Academic Press

A HUNAN GEOGRAPHY OF SPAIN

JOSE MARIA SERRANO MARTINEZ AND RUSSELL KING

Spain has witnessed the most remarkable economic, social and political transformation of an/ West European country over the past 25 years. This volume, the first book on the human geography of the “new Spain,” traces Spain’s own political evolution from dictatorship to democracy, to the autonomous regions. Subsequent chapters deal with demography, the agricultural crisis, industrial restructuring, the growth of the service economy, mass tourism, the welfare state, transport and urban systems. The book concludes with an integrated summary of the constituent elements of the new geography of Spain, set within the context of continuing and emerging regional disequilibria in Spain and with reference to Spain’s position on the dynamic semi-periphery of Europe.

300 pages Publication: Summer 1999

Hardcover ISBN: I 898723 91 5 £45 $65

Paperback ISBN: I 898 723 92 3 £1695 $29.95

A HUNAN GEOGRAPHY OF THE

NEDITERRANEAN

Edited by

RUSSELL KING, PAOLO DE MAS AND

JAN MANSVELT BECK

This book explores the many geographies of the Mediterranean Basin with chapters on the Mediterranean environment, geopolitics, economic development, trade, demography, migration, cities, tourism, landscapes, mountains and islands. Written by an international team of geographers, the book offers a carefully integrated and up-to-date treatment of the contemporary human geography of one of the world’s most fascinating and significant regions.

300 pages Publication: Autumn 1998

Hardcover ISBN: I 898723 89 3 £45 $65

Paperback ISBN: I 898723 90 7 £14.95 $24 95

CONSTRUCTING COLLECTIVE IDENTITIES

AND SHAPING PUBLIC SPHERES

LATIN AMERICAN PATHS

Edited by

LUIS RONIGER AND MARIO SZNAJDER

“Deserves to be read by all those who take a serious interest in the construction of identity.” David Lehmann, Director of Latin American Studies, University of Cambridge

“An exceptional book which decodes the battles fought between imagination and reality in the construction of Latin America’s collective identities.” Tomas Eloy Martinez, Rutgers University

This book shows how different collective identities in Latin America shape the access to, and participation in, the ptsfeSic domain. It significantly enhances our understanding of the historical experience of societies marked by social, politics and intellectual struggles as each shapes a collective identity according to competing visions of modernity.

Hardcover ISBN: I 898723 77 X £45 $65

[Title Page]

Changing Nomads in a

Changing World

Edited by

Joseph Ginat

and

Anatoly M. Khazanov

Sussex

ACADEMIC

PRESS

[Copyright]

Editorial selection copyright © Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov 1998

Copyrights retained bv .ill individual authors

The right of Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov to be identified as editors of this work has

been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

2468 10 97531

First published 1998 in Great Britain by

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

Box 2950

Brighton BN2 5SP

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

5804 N.E. Hassalo St

Portland, Oregon 97213–3644

All rights reserved. Except for quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and

review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Changing nomads in a changing world / edited by Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov

p cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1–898723—44–3 (hardcover : alk paper)

1 Nomads. 2. Pastoral systems. 3. Social change I. Ginat, J II. Khazanov, Anatoly M. (Anatoly Michailovich), 1936- GN387.C49 1998

3U5.9’0961 —dc21 97–26463

CIP

Printed by Bookcraft, Midsomer Norton, Bath

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Contents

Acknowledgments

Great Scholar, Great Man, Great Friend

(Remembering Ernest Gellner)

Anatoly M. Khazanov

Introduction

Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov

1. Pastoralists in the Contemporary World: The Problem of Survival

Anatoly M. Khazanov

2. Who are these Nomads? What do they do? Continuous Change or Changing Continuities?

William Lancaster and Fidelity Lancaster

3. Being Bedouin: Nomads and Tribes in the Arab Social Imagination

Dale F. Eickelman

4. Coping with Change in Arabia: The Bedouin Community and the Idea of Development

Ugo Fabietti

5. Bedouin Settlement Policy in Israel, 1964–1996

Arnon Medzini

6. Continuing Education and Community Development for Bedouin

Helmut Danner and Malta El-Rashidi

7 The joz musarrib: An Unusual Form of Marriage 78 among the Arabs

Frank H. Stewart

8. The Segmentary Lineage System: A Reappraisal

Sharon Ba$tug

9 The Cactus Was Our Kin: Pastoralism in the Spiny 124

Desert of Southern Madagascar

Jeffrey C. Kaufmann

10. The Role of Triabal Groups in State Expansion and Consolidation: The Northern Arabian Peninsula during and after the First World War

Joseph Kostiner

11. The Missing Link: “Badu” and “Tribal” Honor as Components in the Iraqi Decision to Invade Kuwait

Amatzia Baram

12 Preservation and Change in Bedouin Societies in Israel

Joseph Ginat

13 Contemporary Mongol Concepts on Being a Pastoralist: Institutional Continuity, Change and Substitutes

Slawoj Szynkiewicz

14 Understanding Reindeer Pastoralism in Modern Siberia: Ecological Continuity versus State Engineering

Igor I. Krupnik

List of Contributors 243

Index

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to a number of people and institutes who have helped us with the preparation and production of this book. Both the Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung and the Bertha von Sutner Research Program, from Germany, provided financial assistance. A special word of thanks goes to Sara Tamir, Zvia Haimovitz, and Rivka Fadder of the Jewish-Arab Center for their assistance. We also extend our thanks to the University of Haifa Research Authorities whose support made it possible to undertake this project. We are also indebted to the staff at Sussex Academic Press; their assistance and advice is much appreciated.

One important paper is missing in this volume, that of Ernest Gellner. He was going to submit it on the editors’ request; however the paper remained unwritten because of his sudden and premature death. Gellner’s contribution to the study of pastoralism is well known and does not need any reminding. The least that we can do to commemorate this great scholar is to dedicate this volume to his memory.

Great Scholar, Great Man, Great Friend (Remembering Ernest Gellner)

Anatoly M. Khazanov

There is a saying in the Talmud that a man should not refuse to do what he believes he must do, even if he is not destined to reap the fruits of his labor. If this is the case, Ernest Gellner should be considered a happy man. All his life he was an indefatigable disseminator of knowledge, of new ideas and new approaches. He has opened new fields of study, new horizons of scholarship; he challenged many dogmas. And yet, well deserved and world-wide recognition and fame came early in his scholarly life. He liked to claim that his prime interest was in intellectual history, the development of human thought and ideas. Well, his own ideas occupy and for a very long time will continue to occupy an important place in this history. All his works were extensively researched, written with vigor, invariably analytically acute and penetrating far beyond surface events. They will endure, unlike the ephemeral excursions into fanciful pseudo-theoretical ideas so popular and faddish especially today. One might agree or disagree with some of his theories and concepts, but almost everybody recognized him as a great scholar and thinker.

Everybody, except Ernest himself. His modesty and unpretentiousness were extraordinary. Once, only once, in a private conversation with him I mentioned the position that, in my opinion, he was occupying in contemporary social science. It was a matter-of-fact statement, made in a specific context, without any desire to flatter him (nor would he ever tolerate any flattering). Ernest smiled and replied that we certainly had many more interesting subjects to talk about. Apparently the Scotch that I had imbibed that evening made me persistent, forcing Ernest to argue that he was no better than at least two dozen other social scientists. It is my deep conviction that on this matter I was absolutely right and he was wrong. But it is also true that to Ernest the excitement and pleasure of intellectual research and intercourse were always much more important than all the rewards and recognition they might bring. Maybe this was one of the reasons why, contrary to some other great scholars who had peaked and became pundits long before they passed away, Ernest’s peak was always ahead of him. The tempo of his life and productivity and quality of his scholarship remained astonishing to his very last day. His letters to me always began with the words: “Life is hectic at the moment,” or “The pace of life is faster than ever before.” Many times, anxious about this incredible pace and, to tell the truth a little envious of his ability to keep up with it, I told him that he was literally burning himself out, that although younger than he, I would not be able to maintain such a strenuous life for a long time. I am afraid that my pleas to slow down sometimes irritated Ernest a little and he called me a nagging mama; on other occasions, he explained to me that he was simply afraid of getting old. Well, he has escaped that fate. He has passed away at the height of his intellectual powers and old age is the last thing that could be associated with him.

A lot has been said and will be said and written about Ernest Gellner as a great scholar, and with every year to come we will comprehend better his greatness. But he was not only a great scholar; he was also a great man. Unfortunately, this century has provided us with more than enough proof that professional greatness is not always accompanied by high ethical standards or even by elementary human honesty. I am not speaking about people like Martin Heidegger whom Gellner despised so much — with them everything is more or less clear. I am speaking about those gurus of Western Leftist intellectualism who for the sake of their ambitions, illusions, vanity, or for personal reasons, refused to face the truth, or even worse, tried to distort or to suppress the truth. I am speaking about people like Sartre who tried to suppress the truth about the Soviet hard-labor camps because this might disillusion the French working class, or Hannah Arendt who did her best to exonerate Heidegger’s involvement with Nazism, or Derrida who was so angry with those who exposed the collaborationist past of his idol, Paul de Mann.

Ernest was different, very different. His personal integrity and his integrity as a scholar were never in conflict, they were inseparable from each other. I never heard him repeating “Amicus Plato, sed magis arnica veritas,” but this was the principle he unflinchingly followed all his life.

Ernest always spoke his mind and stuck to his principles and conviction even at the risk of losing some popularity in certain circles and countries. I remember how much he angered some radical feminists at the American Anthropological Association meeting in 1990 when, responding to their questions, he stated that there was no male history and no female history, just universal human history. A very prominent American anthropologist who was sitting near me at that moment turned to me and said, “I’m so glad that there is somebody brave enough to tell the truth.” I asked him why he was not following Ernest’s example. His reply was precise and sincere: “Because I am no Ernest Gellner.”

Although Ernest never abandoned his principles, I do not know any other scholar, anyone at all, who was as patient and tolerant to any criticism, and to his critics, as he was, even when these people trespassed the norms of scholarly polemics and attacked him personally. His firm stand against ideas that he considered false and parochial never extended to their proponents; the latter sometimes were much less generous and less impartial. But this is the difference between a great man and those of smaller stature. As Chekhov once remarked, the most intolerable people are provincial celebrities.

Many of us remember the polemics between Ernest Gellner and Edward Said, in which Said, apparently for the lack of convincing arguments, preferred to resort to insults. Still, Ernest did not hesitate to invite him to participate in a conference he was requested by UNESCO to organize, pointing out in his personal letter to Said that scholarly disagreement should not preclude but stimulate a fruitful dialogue. The rude reply of that literary critic should remain on his conscience.

Contrary to many of us, Ernest simply could not comprehend, nor accept the fact that scholarly disagreement too often affects human relations. For many years he considered one famous American scholar to be his friend, and he always told me that their different vision of Social Science would never have an impact on their friendship. I remember how disappointed, even wounded, he became when he discovered that for reasons that I prefer not to speculate upon, this man failed to meet some important criteria of friendship. Still, Ernest continued to hold him in high esteem as a brilliant scholar. Recently, Ernest was planning to pubhsh a special volume devoted entirely to the criticism of Ernest Gellner in which all of his opponents would be invited to participate. This would be quite a unique volume in the history of scholarship, almost as unique as Ernest himself was.

He was much needed by very many people, and it was extremely difficult for him to deny his expertise and assistance to anybody. In June 1995, having been involved in organizing a conference on changing patterns of nomads in a contemporary world at Haifa, I asked Ernest to attend, or, at least, to open the conference. At that time he was very busy with something in London, but still he responded that if I considered his presence necessary, he would take a night flight to Israel, open the conference, and return to London the next night. Thank God, I decided that under the circumstances it would be too cruel to insist on his participation; but now I ask myself how often did I unnecessarily encroach upon Ernest’s time and strength, how many times did I approach him with requests that he did not deny even once, but that were not so crucial and important to me?

Ernest was a man of great intellectual courage and of personal courage as well. This was clear to everybody who was but slightly acquainted with him. Once, when I was traveling in Europe with a group of friends, Ernest invited us to spend a couple of days in his Italian house. When we came to the nearby village, the road from this village to the house turned out to be too difficult for one woman in our group. She asked a villager how Ernest managed to traverse it. The answer was: “He is a man with weak legs, but with a strong spirit and with an iron will.” He never complained about his health problems. On many occasions he managed to hide even from his closest friends that he had to live, work, and travel under severe pain that he had endured for many years.

There is another reason why it is impossible to separate Gellner the thinker from Gellner the man. He never lived and never strove to live in an ivory tower. He enjoyed living in this real, though imperfect, world and the problems and troubles of this world were the matter of his constant concern. He fought in the Second World War, and he volunteered to fight in the Israeli War for Independence; only the 1949 armistice prevented his participation in that new war.

Even his house in Fontanily which, in the Russian fashion he liked to call a dacha, a summer house, was to him not a refuge from the world, but a place where he could do his research and writing about the acute contemporary problems without being beset by a wide variety of administrative burdens and without being interrupted by the nuisances of everyday life in which everyone and his grandmother seemed to have some matter for which Ernest’s presence, participation, or attention were requested.

Karl Marx would certainly be disappointed with Ernest Gellner, and not only because he was never lured to Marxism. Ernest was striving to understand our world and to explain it, but was never actively involved in practical attempts to change it, if this involvement is merely conceived as membership in a political party, or participation in a political movement. Nevertheless, the very fact that at a crucial moment in Czech history he returned to Prague, the city he always loved so much and considered the most beautiful in Europe, proved that he did not shun activism in a broader sense when he thought that he could contribute something feasible in practical terms.

To the extent that thought influences behavior and actions, Ernest was certainly deeply involved in the process of ongoing change in our world. I hope that among other things his strong though sober argumentation on behalf of liberal democracy, his merciless analysis of logical inconsistencies and fallacies in the Marxist theory of historical process, his contempt for the attempts at advocating moral equity in the name of cultural relativism have made an impact, and will continue to make an impact on a significant number of intellectuals in the West and will help them to escape the temptation of worshipping false idols. I do not wish to make an icon of Ernest Gellner. He would be the first to be angry with me for this. Nor does he need canonization. He was a cosmopolitan in the best meaning of this much used and abused word. No one country, no one culture, no one people can claim an exclusive monopoly on him. He was everywhere at home, except among his own home and his family: Susan, David, Debora, Sarah, and Ben, and his grandchildren, all of whom he loved so much. Still, just as a leopard cannot change its spots, Ernest could not avoid the impact that his origin, background, and the circumstances of his life had made upon his thinking and writing. Nor did he wish to escape this impact. When he gave me his book Nations and Nationalism he told me: “This is my autobiography.” I spent the whole night reading it and the next day I asked him: “When you told me that this book was your autobiography, did you mean the chapter on Ruritania (read Czechoslovakia)?” He answered, “No, the whole book, from the first chapter to the last one.”

He cared not only for theoretical concepts but for countries and nations as well. So sensitive to the problems of the contemporary world, he was not devoid of contradictions. But these were the contradictions of a great scholar and a great man who explained phenomena but was unable to change or to prevent their negative consequences. Somewhere in 1989, I told Ernest that the Soviet Union should collapse and soon would collapse. I said, “This is a very positive development and this is inevitable. Why? Read Ernest Gellner. ” To my great surprise Ernest was by no means happy with my forecast, or with my reference to his book on nationalism. At the moment when I was still longing for the destruction of the totalitarian empire, he had already started to think about its negative collateral consequences.

Afterwards we returned to these problems many times. He who explained why nationalism is inevitable in the modem world was very depressed by the rising tide of nationalism in the Middle East as well as in the ex-Soviet Union, Balkans and East Central Europe. This problem was literally torturing Ernest during his last years. Several times he told me, half in jest, about his concept of nationalism: “I wish I were wrong.” This is why he suddenly began to talk in positive terms about empires, about the Austro-Hungarian empire, and even about the Russian and Soviet empires as political bodies capable of preventing, or, at least reducing, ethnic strife.

And still Ernest was cautiously optimistic in his world view and in his hopes for the future. Although he used to point out that there were problems that do not have an immediate and easy solution, he always hoped that sooner or later conditions would emerge for the solution of current problems. He understood the complications of the Israeli-Arab conflict better than many experts and politicians. He wholeheartedly welcomed the Oslo agreement, but immediately pointed out the difficulties that the peace process would inevitably meet. Unfortunately, this prediction, just like his many others, has turned out to be correct. Gellner’s keen interest in the Soviet Union was connected not only with his deep aversion to all forms of totalitarianism. Simply to condemn was not enough for him. In comparison to Raymond Pearson, who was very skeptical about the Soviet Union’s ability to transform itself into a Western-type liberal democracy, Ernest was much more optimistic, and during his numerous visits to Moscow he was trying to discover the inner force capable of gradually reforming the country. He pinned his hopes on a need for security and a regard for efficiency and integrity of the educated middle class, including technocrats and administrators. Later, Ernest admitted that he was wrong, but his approach and attitude are very indicative, indeed.

He cared for concepts, for countries, and for nations. But he also cared for individuals. This brings me to the third side of Ernest’s personality: a more intimate one, but to me at least as precious as the first two. He was not only a great scholar, and a great man, he was also a great friend: absolutely loyal and faithful, sympathetic, indulgent to his friends’ weaknesses, always understanding, always eager to help and to support. He was always making good to his friends, and to many other people, and he was always extremely reluctant to talk about it.

Nobody influenced me intellectually as much as Ernest did, and nobody did me as much good as he did. In his presence I was always becoming more clever, and was vainly trying to become better. When I was a refusenik in the Soviet Union Ernest was one of the most active participants amongst those who literally saved me from imprisonment. Unfortunately, I know much less than I would like to know about his tireless activities on my behalf, because, in Ernest’s opinion, friendship does not need gratitude.

He understood how the Soviet system, and the communist system in general, operated much better than many other people in the West and he used his knowledge not only in his research but also in assisting many people who were in trouble. Once he told me about Dr. Bromley, at that time the head of the Soviet anthropologists: “Bromley would be most happy if he could scratch off your skin but since this is beyond his capability, I am trying to persuade him that he should be satisfied with a little less. He should suggest to the Soviet authorities to punish you in a different way, by letting you out of the country and, thus, by getting you out of his hair.” To tell the truth, I was rather skeptical with this idea, but eventually Ernest succeeded. After his death several dozen letters that he wrote on my behalf urging other scholars to support my plight were discovered in his archives. I had known about a few of them from other people, but never from Ernest himself.

Please, excuse me for these incoherent thoughts and reminiscences. The shock is still too great and the pain is still too acute to arrange them in a more systematic way. From November 1995 Ernest continues to live only in his works, and in his family, and also in us: his friends, his students, his colleagues, in what we are thinking and doing, and in what we are refusing to do.

Still, I know for sure and I already feel that my life will never be the same without Ernest, without our meetings and conversations, without playing chess with him, without his letters and telephone calls from the most unexpected places, without knowing that Ernest simply exists in this world. It has already become colder, duller, more colorless, less exciting. So, allow me to conclude my reminiscences about Ernest Gellner, great scholar, great man, great friend with a traditional saying: zihrono livraha, may his memory be blessed.

Note

This essay was first presented as a talk given at the Ernest Gellner Memorial Conference in Prague, December 1995.

Introduction

Joseph Ginat and Anatoly M. Khazanov

This volume consists of the revised texts that were originally submitted to the Conference “Changing Patterns of Nomads in Changing Societies,” which took place at the Jewish-Arab Center, The Gustav Heinemann Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, University of Haifa, in June 1995. The chapters by Kaufmann, Krupnik, and Szynkiewicz were specially written for the volume at the editor’s request. Although the chapters of this book deal with different geographic areas and with different issues, they are united by a general theme: socioeconomic and cultural changes in contemporary pastoralist societies and groups. In most, if not all the cases, these changes are far from being spontaneous. They result from the painful adaptation of the mobile and extensive pastoralists to the modern (some scholars would argue already post-modern) world, in which, as a rule, the pastoralists are occupying only a marginal and inferior economic and social position (see the chapter by Khazanov). As the chapters by Eickelman, Fabietti and Danner, and El-Rashidi demonstrate, this is true even with regard to the Middle Eastern countries, although in some of them a social prestige connected with pastoralism is still quite high. William and Fidelity Lancaster claim in their chapter that the pastoralists in some Middle Eastern countries are unable to avoid the governments, but have learned how to exploit them. Still, one may wonder whether this situation is permanent or even optimal for the pastoralists’ development. As Fabietti points out, in Saudi Arabia Bedouin stand for ancestors but also for “backward people” or even “savages.”

A worldwide deterioration of the socio-political and economic standing of the pastoralist began in early modern times, continued during the colonial period (see the chapters by Kostiner and Kaufmann), and often was strengthened by the decolonization process. This situation is directly connected with the ongoing changes taking place in those modernizing sedentary societies into which the pastoralists were incorporated, not infrequently by force.

Thus, the main problem discussed in this volume is the modernization that the pastoralists are undergoing, or have to undergo, in order to survive as valuable contributors to national and international economies. In order to make our own position clear, we should stress at the outset that we conceive modernization as economic growth based on technological innovations, which implies corresponding cultural changes and changes in the socio-political organization. We are obliged to provide this explanation because nowadays the very term “modernization” is considered by some scholars as outdated and even “politically incorrect,” and is often substituted by much broader but vague terms, such as “change” and “development.” As the Lancasters point out, change in nomadic societies is inevitable, continual and expected, due to the very nature of their way of life. However, change is by no means always synonymous with modernization.

Well-known deficiencies of modernization theory, as it was advanced in the 1950s and 1960s, have discredited not the concept itself, but only its specific approaches (i.e., the belief that every country should and will follow the Western model of socio-economic and political development). Still, this concept needs some elaboration with regard to specific types of economic activity and social settings. In this respect, mobile pastorahsm serves as a good example. On the one hand, the extensive and mobile pastoralism still remains as a viable economic alternative in many arid and semi-arid zones of the world. On the other hand, its dependence on natural pastures hinders steady economic growth. Even technological improvements in pastorahst systems aimed at their intensification may have but a limited effect and sometimes even negative collateral consequences (i.e., when they lead to overgrazing and deterioration of natural pastures).

It is obvious that one must speak about modernization of the extensive and mobile pastoralism not in isolation, but only in broader terms, when this type of economic activity is incorporated into modernizing national economies as a specialized but integral sector, and when the pastoralists benefit from their membership in the society at large. Accordingly, the pastoralists should become and must be accepted as full-fledged citizens of these modernizing states. However, this is not always the case. The mutual distrust of the modernizing states and the pastoralists is evident in many countries. Thus, the chapter by Ginat provides examples of the Bedouin desire to escape the authorities and to solve their problems without the latter’s interference.

Furthermore, membership in modernizing societies imphes specific economic policies and stimuli with regard to the pastoralists, such as favorable taxation and price policies, and the development and expansion of modem infrastructure, transport facilities and services, veterinary care, education, investments, and even subsidies. However, the pastoralists in the Third World countries are too often considered as donors of the modernization process, rather than as its beneficiaries.

The problem of subsidies is, apparently, the most controversial one. The current mood of many international agencies which deal with the development of Third World countries is negative as far as subsidizing agricultural production. This attitude raises many doubts since agricultural production remains subsidized, in one way or another, even in the countries of Western Europe, the USA, Japan, and Israel, where agriculture, including stock-breeding, is the most developed. The poor developing countries certainly lack the necessary financial resources for further modernization in this area. The problem, as we see it, is not whether subsidies are needed for modernization of mobile pastoralism, but how to gain access to them and how to use them in the most efficient way.

The chapters by Szynkiewicz and Krupnik demonstrate, through the examples of Mongolia and the Russian Far North, that some ex-Communist countries are facing a similar problem. A sudden withdrawal or reduction of subsidies and services, such as water supply or fodder provisions, as well as of state-regulated marketing channels, which in the recent past were provided by the communist state, have made a negative impact upon the pastoralism in these countries. One may observe similar consequences of this situation in such Central Asian countries as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, where the number of livestock has drastically decreased during the last few years.

On the other hand, an overdependence on subsidies may also be detrimental to modernization of mobile pastoralism. In some oil-rich Arab countries, for example, the pastoralists enjoy artificially favorable conditions. However, one may wonder if this makes their economy efficient and capable of withstanding competition from international producers of meat, dairy products, and wool. Subsidies and other assistance are needed as incentives for development, not as compensation for a lack of proper development. Danner and El-Rashidi point out that in Egypt, the solution of Bedouin problems is too often left to government authorities, even if a problem could be taken care of by the Bedouin themselves. Likewise, Fabietti notes in his chapter that government investments in the pastoralist sector have not achieved the desired results because the Bedouin were not involved in the operations that concerned them. One general conclusion is that while the paternalistic policies toward the pastoralists turned out to be inadequate for, and even detrimental to, their development, dooming them to a role of passive recipients of the “development package,” without a voice in the decision-making, the traditional pastoralists can hardly be left alone with no assistance at all. Their own resources are too meager to be sufficient for spontaneous modernization.

The old debate on whether modernization of the mobile pastoralists should better proceed along the socialist or capitalist lines seems to have come to an end. The Soviet experiment with collectivization and forced sedentarization of the pastoralists, which, to some extent, was followed by several other countries, turned out to be a failure in an economic respect and was ruinous to the pastoralist way of hfe. In the late Soviet period, a relatively high number of livestock in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Kalmykia, was maintained by artificial measures: large subsidies, a total disregard of the production costs and rapidly deteriorating natural environment, and strict everyday control and supervision by appointed managerial staff, which denied any initiative on the part of the pastoralists themselves. As soon as the policy was changed, the crises of pastoralism followed immediately.

Still, it is worth noting that the Soviet experiment was wrong not because sedentarization was its primary component, but because of the ways in which sedentarization was imposed upon the pastoralists. In principle, sedentarization of at least a part of the mobile pastoralists is inevitable and even desirable under modern conditions, if it channels the surplus labor in the pastoralist sector into other occupational activities. It may even increase economic efficiency among those who remain involved in mobile pastoralism. Although this process may be spontaneous, it may be facilitated or hindered by different governmental policies (cf. “the stick and the carrot” policy practiced by the Israeli government, which is described in the chapter by Medzini, or the discriminatory policy of land allocation and long-term land distribution practiced by the Saudi Arabian government, which is mentioned in the chapter by Fabietti).

It is obvious that in order to survive, mobile pastoralism should adjust to the contemporary economic climate. In particular, it should undergo a certain commercialization and a market-oriented transformation. A mere conservation of its subsistence-oriented forms is neither desirable nor feasible and would only relegate it to a reservation-like way of life.

However, the ways and models of incorporation of mobile pastoralism into the contemporary economic order remain unclear. Some experts on economic development have advocated its transformation into the capitalist ranch system based on individual land-tenure. The recommendation, when it was implemented in practice, turned out to be inadequate for environmental and social reasons. Ranch forms that emerged in some countries in the nineteenth century were by no means a result of the spontaneous transformation of the traditional pastoralist economies. Rather, they were created and introduced anew. In economic and social respects, they were capitalist from the very beginning, even in their initial forms.

One may wonder whether individual entrepreneurship and land ownership are optimal solutions for modernization of extensive pastoralism in any country. In some Third World countries, the situation is quite different from that which existed in the USA or Australia. Pastors Urn in Third World countries retains many traditional characteristics and in some, it is still, to a large extent, non market-oriented, and continues to be connected with the communal forms of land tenure, and with kinship and descent-based forms of social organization. Sharon Ba§tug dwells on the latter issue in her discussion. Several chapters in the volume also demonstrate the resilience and continuing importance of many traditional forms of social organization, even under conditions of rapid socio-economic change (see the chapters by Ginat, Kostiner, the Lancasters, Medzini, and Stewart). Szynkiewicz points out that kinship and neighborhood-based communities became important factors in restructuring social relations in post-Communist Mongolia. One may observe a similar tendency in Kazakhstan.

Nevertheless, the continuing changes in technology, markets, information, and governmental control, as well as new opportunities in other sectors of national economies, are undermining traditional social norms and bonds. Modernization brings not only economic and technological changes, but social and cultural changes as well. This may increase the tension within pastoralist groups. At the same time, the problem of their integration into nationalizing states is further exacerbated when the pastoralists have to integrate into societies which are alien to them in cultural and ethnolinguistic respects. Ginat demonstrates this through the Israeli Bedouin and Krupnik with an example of the Northern pastoralists in Russia.

On the pohtical level, tribalism, which is embodied by the pastoralists, although it is not coterminous with them, still affects the process of nation-state building not only in the Middle East, as demonstrated by Eickelman, but even in some central Asian countries. In his analysis, Baram shows the importance of “honor” in the political structure of Iraq and emphasizes that the phenomenon is related to tribal organization. Kostiner’s chapter points to the important role played by the Bedouin in shaping the modern political configuration of the Middle East. However, as a rule, the contemporary nationalizing and developing states in this region have little experience with any politically autonomous bodies on their territory; hence, their attempts at detribalization (see the chapter by Fabietti).

Under these circumstances, the transformation of mobile pastoralism and its adjustment to or incorporation into modern economic systems and nationalizing states can be only gradual. In this case, the mere destruction of the traditional forms of social organization will not bring positive results. It is impossible to predict what exact forms the transformation of traditional mobile pastoralism into a market-oriented one will eventually take. It is obvious, however, that there will be various forms, and that they may be quite different from each other in terms of land tenure, degree of cooperation between the pastoralists, and many other parameters.

Only a few things seem to be more or less clear at the moment. Assistance to the mobile pastoralists is desirable, if its goal is modernization of their economy and traditional way of life. However, this assistance should stimulate self-development, rather than serve as a substitute for it. In other words, the worst that can happen (and sometimes has already happened) to the mobile pastoralists is to take their destiny away from them.

1. Pastoralists in the Contemporary World: The Problem of Survival

Anatoly M. Khazanov

Recent failures and shortcomings of modernization attempts in many Third World countries have proved that modernization is not just tantamount to industrialization and urbanization. It also involves a deep transformation, or even destruction, of many traditional social, economic, and cultural institutions (Eisenstadt, 1973). Some scholars consider this inevitable. “In the footsteps of modernization a disruption of old systems of social control and their economic base is inevitable” (Back, 1993: 79). However, the mere destruction of traditional forms of social organization may result not in the emergence of a vital new system, but in disorganization, chaos, and social dislocations. As an example of the negative effects of modernization, imposed from the outside and not connected with spontaneous development, I will refer to extensive pastoralists. These are the groups whose subsistence mainly depends on a mobile way of life and the maintenance of herds all year round on a system of free-range pastures, and who practise agriculture only as a supplementary and secondary activity or, like pure pastoral nomads, even do not practise it at all.

Were this chapter devoted to the general question of the change in relations of pastoral nomads and mobile pastoralists in general with various sedentary societies, I would sum up my ideas in the following way: Their past was unique considering their former role in world history, their present is precarious, and as for their future — it seems dubious at the moment, if present tendencies continue. There are more than enough people who assume that pastoralists simply do not have any future at all.

Still, there are about 30 to 40 million of these people mainly in the Middle East, Central and Inner Asia, Africa, and the Far North. In such African countries as Niger, Djibouti, Somalia, and Mauritania the pastoralists constitute the majority of the population. To all of them modernization has become an acute and yet unsolved problem. It also became a hot political, economic, environmental and humanitarian issue for national governments and various international agencies involved in development, as well as for anthropologists along with sociologists, economists, planners, experts in development, and many others. At present they all are trying to solve the problem. So far the results are poor, sometimes even disastrous for the pastoralists themselves. Baxter (n.d.: i) barely exaggerated when he stated: “Almost all, indeed maybe all, the development interventions to date had not helped the impoverished pastoralists at all, nor had they added a cent to the wealth of any nation. Pastoralists had survived despite development schemes, not because of them.”

It might seem that the most simple and obvious alternative would be to leave the pastoralists alone and allow them to maintain their traditional way of life. This is hardly feasible, however, in the current global situation. It is true that for a very long time, extensive and mobile pastoralism was, even in ecological respects, the most suitable form of economic activity in several climatic zones. This is true despite the insufficiently substantiated claims that “nomadic pastoralism is inherently self-destructive, since systems of management are based on the short-term objective of keeping as many animals as possible alive, without regard to the long-term conservation of land resources” (Allan, 1976: 321); or that, “the nomad ... has no vested interest in the land his flocks graze. He is not even interested in conservation. Traditionally he would scorn the idea that his flocks were overgrazing his territory. If the pasture deteriorated he would move on into fresh pastures” (Spooner, 1973: 37). The ecological, economic and social foundations of traditional mobile pastoralism made it incapable of any long-term economic growth based on increases in productivity and livestock reproduction on an expanded scale. Moreover, they implied its constant instability. At the same time, this very instability prevented overgrazing from becoming a permanent problem. Although stock numbers sometimes outgrew the carrying capacities of utilized pastures, ecology and biology made periodic losses of livestock inevitable because of various natural calamities.

It was just such cyclical fluctuations that maintained a long-term balance in the pastoral economy, however ruinous they might be in the short run. Thus, a correlation between overstocking and overgrazing in traditional pastoral economies is much more complicated than it is sometimes assumed by ecologists and development experts. Besides, a growing body of data indicates that often pastoralists developed quite efficient folk conservation systems (Hobbs, 1992: 109 ff).

Specialization means dependency. The location of pastoralists in arid or semi-arid geographical zones and their mobile way of life left little room for agriculture and crafts, not to mention industries. The more specialized mobile pastoralists were, the more dependent they became, in turn, on the outside, non-pastoralist, mainly sedentary world. Written sources, since the very first mention of nomads, make it clear that agricultural products formed an important part of their dietary systems. These sources, as well as numerous archaeological data, also demonstrate beyond doubt that nomads procured a substantial part of their material culture from the sedentaries, as well as other aspects of culture and even ideologies. As the nomadic economy needed to be supplemented with agricultural products and crafts from external sources, so nomadic culture needed sedentary culture as a source, a component, and a model for comparison, imitation, or rejection. To a lesser degree the same applied to semi-nomads. Therefore, pastoralists had to adapt not only to specific natural environments but also to external socio-political and cultural environments.

In the past, particularly in the medieval period, their military superiority and undeveloped social division of labor often allowed the pastoralists to overcome the deficiencies of their specialized but subsistence-oriented economy by acquiring the necessary products of agriculture and crafts by non-economic measures such as using force or threatening to resort to it. That was particularly true for the Great Nomads of the Near and Middle East and the Eurasian Steppes who were capable of numerous intrusions and conquests in ancient and medieval history. Their relative economic and social undevelopment turned out to confer a military and political advantage (Khazanov, 1994).

This situation began to change in the early modem period, when sedentary states achieved significant progress in transportation and warfare. Caravels, and then steamboats and railroads, proved to be more efficient than caravans, and regular armies of centralized states became stronger than irregular cavalries of the pastoralists. First, the pastoralists lost their military superiority, then their political independence; afterwards they had to adjust to forces beyond their control, including the economies of the modem or modernizing sedentary world. The increasing dependence of the pastoralists on colonial powers, and then on national governments which favored agriculture and industries and often pursued deliberately anti-pastoralist policies, had several detrimental effects. It contributed to the further marginalization of the pastoralists, decreased the size of the territory occupied by them, undermined their subsistence-oriented economy, and eroded the stability of their society. New political maps of the world also seriously hindered the pastoralists. The stable but sometimes artificial boundaries of the new states often spht the grazing areas that in the past had been utilized by the nomads and negatively restricted their migratory routes and patterns.

In many countries the expansion of urbanization and industrialization, and the intrusion of farmers and peasants into pastoral areas especially, was due to the growth in sedentary populations, the development of national economies, and deliberate policies of colonial powers and national governments. This happened in Central and Inner Asia, in the Middle East, in Africa, and in other parts of the world. Thus, the governments declared the whole uncultivated steppe and desert areas in Central Asia, Iran, and Syria to be state or public property and brought agriculture into areas occupied by the pastoralists (Demko, 1969; Lewis, 1987; Shoup, 1990). In Israel, most of the land in the Negev which is now held by the Lands Administration had previously belonged to the Bedouin (Abu-Rabi‘a, 1994: 15). In Inner Mongolia, the Chinese population increased from 1.2 million in 1912 to 17.3 million in 1990 (Ma, 1993: 173). The Chinese peasant colonization pushed the nomads to marginal lands and eventually made them an ethnic minority in what had been their own country (Sheehy, 1993: 17—30). The Land Use Act of 1978 in Nigeria provided the state with ownership of all land in the country. In 1957, about 67 percent of Nigeria’s land had been available for grazing livestock; by 1986, this territory was reduced to 39 percent (Gefu and Gilles, 1990: 39, 40). By 1987, pastoralists in Nigeria controlled over 90 percent of the total national herd but had no right to land (Awogbade, 1987: 19). Governments in other African countries also alienated many grazing lands traditionally utilized by pastoralists and put a brake on their movements (Bovin and Manger, 1990; Silitshena, 1990; Galaty and Bonte, 1991; Smith, 1992). Thus, in Mali, the government declared all noncultivated land to be open to grazing by the animals of any citizen, including rich urban businessmen, politicians and local farmers (Grayzel, 1990: 63). In India, the Raika pastoralists were denied the right to be eligible for receiving any land during the land reforms of the 1950s in Rajasthan (Kohler-Rollefson, 1992: 80—1). On the other side of the world, in the Scandinavian Arctic and Siberia, the reindeer pastoralists suffer because many pastures were lost to hydroelectric development, extractive industries, and other projects (Paine, 1982; Savoskul and Karlov, 1988; Morris, 1990; Forsyth, 1992: 402—3; see also the chapter by Krupnik in this volume).

After large gas and oil deposits were discovered in the Yamal Peninsula, the Soviet government decided to start rapid exploration and development of the area, although some experts had warned that it would not be profitable even from a purely economic point of view. As usual, the rights and needs of the native reindeer pastoralists were not taken into account at all. The machines moving north destroyed the tundra so that in a few years the reindeer farms in the Yamal-Nenets District lost 594,699 hectares of pasture and more than 24,000 reindeer. Each oil bore-test leaves 4 to 9 hectares of spoiled land. By the year 2000, the pastureland in the Yamal may shrink by half, at a minimum. The same happened in other regions of Siberia. Between 1970 and 1987, the reindeer herd decreased by 15 percent in the Magadan Region, by 30—40 percent in the Krasnoiarsk Territory, and almost ceased to exist on Sakhalin island (Leibzon, 1992: 4; Vakhtin, 1992: 24). When Mr Zoteev, in the 1980s the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Russian Federation, was asked why the plans for industrial development of Siberia did not take into consideration the interests of the indigenous population, he answered without hesitation: “The interests of the State go first, the interests of the people are subordinate” (Vakhtin, 1992: 26).

While the territories occupied by pastoralists in different parts of the world are decreasing, nowadays they are sometimes required to produce more, although this often results in serious overgrazing and advancing desertification (see, for example, Tserendash and Erdenebaatar, 1993 on Mongolia; Hogg, 1992 on East Africa). The pastoralists not only have to purchase on the market the necessary agricultural and industrial products, they also have to pay taxes to subsidize bureaucracies that are alien to them, and/or the development biased in favor of other branches of the national economies. They are increasingly being drawn into national, regional and international systems based on a monetary economy and regular surplus production. However, subsistence-oriented economies, even specialized ones, are easily overstressed when they become dependent on market transactions and have to produce in accordance with market demands. Stress is even greater if the subsistence-oriented economies undergo some kind of modernization but continue to operate within the framework of traditional social organization and communal land tenure. As Gorse and Steeds (1987: 10) noted: “Planners have often misunderstood the logic of traditional production systems, and have thereby overestimated the ease with which improvements could be introduced and underestimated the negative consequences of intended improvements.” In many countries, the over-exploitation of productive ecosystems in the arid zones through attempts at intensifying extensive pastoralism by implying modem technologies gave rise to desertification and degradation of vegetation, soil and water (Reining, 1978). The steppes of Kalmykia and the North Caucasian piedmont are rapidly deteriorating because their seasonal pastures at present are used all year round (Kotliakov, Zonn, and Chemychev, 1988: 62—3, 89). In Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, vast areas of fertile pastures have turned into sand deserts due to overgrazing without a seasonal rotation of pastures and a trend away from multispecies toward monospecies herd composition (Wolfson, 1990: 41—2).

Some African governments, who were advised and assisted by foreign donors and experts, initiated various water development programs including the drilling of boreholes and the installation of mechanical pumping stations to improve pastures and increase the beef production at the expense of traditional dairy-oriented pastoralism. Wells were often opened to everybody, sometimes even to pastoralists from all the neighboring tribes (Bernus, 1990: 124), while in the past access to water resources usually was controlled by certain segments of the local pastoral society. As a result, pastures around new wells soon became overgrazed (Goldschmidt, 1981: 104 ff; Horowitz, 1981: 61–88;; Bemus, 1990: 166–7). When drought struck, many animals perished from the lack of fodder (Leya, 1975). In Somalia, the result of water development without an accompanying grazing management program also caused the overconcentration of livestock in proximity to wells with great damage to the vegetation and soil. In the late 1970s, degradation of the grazing resources in Somalia was perceived to be widespread (Handulle and Gay, 1987). Recent Sahelian history also provides us with many examples of how hasty attempts at modernization led to overgrazing and, thus, along with droughts, contributed to the deterioration of pastures and the decay of traditional pastoralism (Gorse and Steeds, 1987).

It is difficult, in principle, to maintain traditional mobile pastoralism within the current economic and political climate. Those who are involved in it face two main options. They must modernize it by making it even more specialized, but along the fines of commercial production, in other words, by producing mainly for the market; or, on the contrary, by supplementing pastoralism with some modern economic activities. Actually, one option does not exclude the other. Otherwise, pastoralists face the risk of being further marginalized and encapsulated, or of becoming zoo groups, the exotics for urban romantics and tourists for whom the sight of black tents represents a living museum’s inventory. Episodic revivals of more or less traditional pastoralism, in one country or another, are more connected with temporary factors, such as the weakening of central power, than with longstanding trends in modem development.

The problem as it has been formulated by different governments and implemented by various development agencies is what kind of modernization is the most suitable for the pastorahsts? The very formulation of the problem in these terms is dubious because it assigns to the pastoralists a role of passive recipient. Before any developmental policy is implemented there should at least be dialogue and negotiation with the population that will be affected. The problem is not so much what to do with the pastoralists, but what the pastoralists have to do to adjust to the demands of modernity. Unfortunately, their opinion is very seldom taken into account. National governments and international agencies often prefer to talk and decide among themselves, without listening to those who are supposed to benefit from their decisions. No wonder, in most cases, that they remain external and alien powers to the pastorahsts. Even such liberal governments as in Norway, which, in principle, maintains that the Saami pastoralists themselves must make their own decisions, in practice they systematically take decisionmaking responsibilities away from them (Paine, 1994: 191).

The underlying reasons of the decision makers, even when they are not connected with specific political interests, are invariably the same, and are based on two main assumptions. First, in our modem times, the pastoralists simply can no longer maintain their traditional way of fife and subsistence-oriented economy. Second, the pastoralists themselves are incapable of developing viable adjustment strategies; therefore, they have to be paternalized and guided. The first assumption is correct, the second is not.

So far, only two main solutions have been suggested, experimented with, and, in many cases, have resulted in disappointment. The first one is advocated mainly by experts from Western countries. Its declared goal is to transform traditional pastoralists into commercial stock producers, assuming there is a fully-developed market structure (Ingold, 1978: 121), or into a highly regulated and restricted form of pastoralism, with its economy, like in Sweden, being dependent on the state welfare system (Hjort af Ornas, 1992). Some experts even recommend turning traditional pastoralists into capitalist-type ranch-owners.

For the last thirty or so years, attitudes of many governments and aid agencies, such as USAID, FAO, and the World Bank, were bolstered by the “tragedy of the commons” hypothesis suggested by the American ecologist Garret Hardin (Hardin, 1968: 1243—8; Hardin and Baden, 1977). It is claimed that the lands held in common, rather than those that are privately-owned, inevitably suffer from overgrazing and environmental degradation, since each pastoralist strives to maximize returns by increasing his herds. This hypothesis is based on insufficient knowledge of traditional pastoralism, and has already been disputed by a number of scholars (see, for example, McCay and Acheson, 1987; Paine, 1994: 187—8).

The adherents of the “tragedy of the commons” concept confuse common property on pastures and other resources with open access to them. In fact, common property among extensive pastoralists is a rather institutionalized, communal one which is based on an elaborate system of checks and balances, on overlapping temporal and spatial rights and constraints which regulate access to pastures. In many cases, traditional land-tenure systems are the best guarantee of optimal resource exploitation (Sanford, 1983; Swift, 1988; Meams, 1993). Attempts to intensify the pastoralist production in the arid environment through privatization of grazing territories often result in overgrazing, deterioration of pastureland, and increased ecological and economic instability.

With few and incomplete exceptions, different ranching schemes and the privatization of grazing lands undertaken in several African countries, like Kenya and Tanzania, or in the Middle Eastern ones, turned out to be inadequate for environmental, social, and other reasons. In many desert and semidesert areas precipitation is unpredictable, most of the pastures are seasonal, and their productivity is low and considerably variable from year to year. In some arid zones a pastoralist needs to have access to 100,000—300,000 hectares to ensure the survival of livestock over time (Gefu and Gilles, 1990: 37). In this situation, the pastoralists should have the freedom to move with their stock over a large territory. Moreover, to overcome the negative effects of destocking during the dry years they must keep more animals than are needed for subsistence, even at the risk of temporary overgrazing. In West Africa, many development schemes turned out to be inappropriate and destructive because they encouraged pastoralists to increase herd numbers in order to ensure a surplus for the beef market. However, the pastoralists welcomed the larger herds that provided them more security within their traditional survival strategy (Mamham, 1979: 12). East African range areas are littered with the carcasses of failed livestock projects, some of which merely hastened overgrazing and land degeneration (Raikes, 1981: 3).

Besides, administrators and planners who tried to turn traditional pastoralists into commercial livestock producers have not realized that production is not only an economic activity, it is also a socially and culturally constructed activity. Thus, many pastoralist groups, especially in Africa, are reluctant to produce meat for the market because stock for them is not only a means of subsistence, but also a form of wealth, a social capital, and a source of prestige and esteem connected with specific cultural values. It is very difficult, in many cases almost impossible, to turn traditional pastoralists into capitalist ranch-owners without drastic changes in their social organization, without destroying their communal forms of land tenure and depriving a large number of people free access to pastures. Even the advocates of ranch schemes admit that allocation of large tracks of land to a few individuals will alienate the other pastoralists and that, in the long run, this policy will legitimize the concentration of land in the hands of only a few individuals, thereby creating a new set of social and political problems (Awogbade, 1987: 25—6). In many such cases the social cost may be too great, since it inevitably leads to an increasing number of displaced and unemployed persons who, in the currently prevailing conditions in many Third World countries, are denied viable possibilities for readjustment and alternative employment. Most jobs held by pastoralists in East Africa, especially those who are forced to work to provide for their families’ subsistence, allow few prospects for social and economic advancement (Sperling and Galaty, 1990: 89).

Furthermore, traditional pastoralists usually lack both the experience and the necessary capital to start market-oriented ranch enterprises. Thus, in Turkey, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, some West African countries, and nowadays in Mongolia and Central Asia, it is not the pastoralists but sedentary businessmen with managerial experience and people with good connections in the government who have estabhshed commercial livestock enterprises. They rent pastures, negotiate transportation, and organize the delivery of stock, meat and dairy products to the markets. The pastoralists have at best been hired as shepherds, but even this is not always the case. It is not surprising that the development of capital-intensive livestock production usually leads to a concentration of benefits in only a few hands (Waters-Bayer and Bayer, 1992: 4). In Kenya, thousands of hectares of Maasai pastures have been skimmed off by corrupt officials and local bigwigs. In some places the entire savanna has been divided among politicians and their friends. Some of the best lands belong to President Moi, the second best to the Vice-President, and the inferior places to their cronies (Ellwood, 1995: 9). Overall, 40 percent of the privatized land has been appropriated by non-Maasai and is used mainly for speculation (Hjort af Omas, 1990; Galaty, 1992; see also Arhem, 1985 on Tanzania; Maliki, 1986 on Niger; Hinderink and Sterkenburg, 1987 on Botswana; Mohamed Salih, 1990 on Sudan; and Waters-Bayer, 1988 on Nigeria).

Hollywood images of the cowboy should not distort the truth. The open range system, that developed in the United States and in some other countries during the second half of the nineteenth and in the first half of the twentieth centuries, was from the outset very different from the traditional pastoral economies, both in its land-tenure system and its operation within a capitalist profit-oriented economy. In the beginning, the availability of free range and rapid growth of the East coast and European beef markets guaranteed cattlemen high prices and profits, especially after the introduction of refrigerator cars in 1869 and refrigerated ships in 1875. Later on, the open-range system was rapidly replaced by the intensive system of fenced ranching with irrigated pastures, machinery, motorized transport, tame-seed forage plants, breeding, shelters for brood cows and calves in the winter, and so on (Dale, 1960; Atherton, 1961; Bennett, 1985; Barsh, 1990). Still, it is remarkable that even in the United States the ranchers have to rely on government subsidies and supports (Gilles and Gefu, 1990: 110—11). It would be unrealistic to expect similar developments in many Third World countries, at any rate in the short run.

The second solution to the problems connected with traditional mobile pastoralists was advocated particularly strongly by governments and governmental experts from the communist countries, and from many developing countries as well. The suggested solution is the sedentarization of pastoralists which, in the opinion of the communist experts, should be accompanied by their collectivization. Very often, these people consider the pastoralists as an obstacle in the path of progress and are inspired by the desire to impose upon them the power of central governments.

Thus, in 1973, when the Sahel was affected by a severe drought and many pastorahsts there lost their stock, Ebrahim Konate, the Secretary of the Permanent African Interstate Committee for Drought Control, expressed his satisfaction with the situation with remarkably cynical frankness. He stated: “We have to discipline these people, and to control their grazing and their movements. Their liberty is too expensive for us. Their disaster is our opportunity” (Mamham, 1979: 9).

The results of the policy of sedentarization, however, are not infrequently disastrous to the pastorahsts and dissatisfactory to national economies of the countries in which this policy had been pursued. The forced sedentarization of the Kazakh pastorahsts initiated by the Soviet government in 1931–2 cost those people about two million lives and literahy decimated their herds (Khazanov, 1990: 90—1). It took more than forty years for the stock population in Kazakhstan to regain the numbers of the late 1920s. However, in the 1970s, the state’s demand to increase the number of stock resulted in the serious deterioration of the diminishing territory still allocated for pastorahsm. At present, 55 million hectares of pastureland, about one-third of ah productive lands in Kazakhstan, are virtually destroyed (Masanov, 1995: 41).

Likewise, in Iran, during the reign of Reza Shah, the government forced the pastorahsts to settle, which soon resulted in their impoverishment. About 75 percent of their stock perished because of the epidemics and the lack of sufficient pasturage (Irons, 1975: Tapper, 1979: 22; Beck, 1986: 129 ff.; Black-Michaud, 1986: 83 ff.).

Unfortunately, the lesson of these failed attempts at sedentarization is not sufficiently taken into account. After the drought of 1974, the Somah government, inspired by the Soviet cohectivist model, decided to move 120,000 camel herders from the north into four villages on the Indian Ocean coast to force them to become fishermen and small farmers (Ellwood, 1995: 8).

I can only agree with Salzman (1980: vii): “Sedentarization, viewed as an inevitable and necessary step in furthering progress and advancing civilization, and pressed upon nomadic peoples by external forces, can have detrimental consequences not only for the nomadic peoples themselves but for the large societies of which they are part.”

It is true that sedentarization of the mobile pastoralists due to their impoverishment, migrations, or some other factors is by no means a new phenomenon. However, in the past, successful sedentarization usually occurred when the pastoralists migrated into areas favorable for agriculture and often seized by force arable lands in oases or in zones of dry agriculture. Nowadays, this opportunity does not exist anymore and the pastoralists who are forced or have to settle face additional difficulties connected with the shortage of land suitable for cultivation, competition with the agriculturalists for a diminishing resource base, unfavorable climatic change, and so on. It seems that nature lends a helping hand to anti-pastoralist policies in some countries. The recent droughts in Africa deprived many pastoralists of their animals and forced them to move to the slums of nearby towns and cities, or to start to cultivate marginal lands that agriculturalists themselves consider of little use, since agriculture there is risky and results are unpredictable. Not infrequently, these lands soon become degraded. “It is obvious that an outright acceptance of pastoral settlement programmes in the arid and semiarid zones of Africa amounts to suicide in an ecology characterized by erratic and sharp seasonal variations in rainfall and pasture” (Mohamed Salih, 1992: 5). It is also obvious that in order to be successful, sedentarization programs among other things should be accompanied by extensive irrigation projects and other large-scale capital investments. With few exceptions, neither national governments nor international agencies seem ready or able to make such investments. When the projects are undertaken, the pastoralists are sometimes excluded from their benefits. In the 1950s, the Soviet government initiated the so-called “virgin lands campaign” aimed at sowing wheat on huge tracts of land in the northern Kazakhstan steppes. This development was clearly at the expense of Kazakh pastoralists. Their stock-raising state and collective farms were closed but Kazakh employees were prevented from becoming involved in grain production. Likewise, the Sudanese government stated, in 1962, that for a very long time nomads could not make us of irrigation lands (Mohamed Salih, 1990: 71).

The example of some Arab countries, in particular the oil-producing ones, which for some specific historical and social reasons are investing part of their financial resources in improving the economic and living conditions of the Bedouin in the form of money payments, land distribution, job offers in the military and administration, development of education, medical care and infrastructure (see, for example, Katakura, 1977; Cole, 1981; Fabietti, 1982; Lancaster, 1986 on Saudi Arabia; Scholz, 1981; Jansen, 1986 on Oman; Behnke, 1980 on Libya), can not be followed by other developing countries. Besides, the negative consequences of this policy are also evident. There are very few ranch and stock enterprises in existence, and those that do exist are not able to satisfy their countries’ needs. The sad fact is that the region where pastoralism flourished for millennia, at present has to rely upon imported meat and even dairy products. One may also wonder what will happen to pastoralists and former pastoralists in these countries if governmental subsidies are withdrawn or reduced due to fluctuating oil prices on the world market or other reasons. How many stock enterprises will go bankrupt without the government assistance that heavily subsidizes pastoral production?

It seems that it is still premature to dismiss mobile pastoralism as a viable food-producing economy in many arid areas. It is worth keeping in mind that pastoralism was originally developed as an alternative to agriculture in just those regions where the latter was impossible, or economically less profitable. In many of those areas the situation remains basically the same. In many countries, the complete transformation of their pastoralists into sedentary cultivators would mean that vast desert and semi-desert territories unsuitable for cultivation would cease to be used for food production and would be left to he as waste land.

One may agree with Raikes (1981: 250) that the most productive (or least destructive) way to incorporate mobile pastoralists into national economies is “through developing the production and productivity of existing herding systems rather than through their replacement by ‘modern’ systems.” The problem is not how to substitute extensive pastoralism with other types of economic activities but rather how to make it more efficient, and at the same time how to lessen the pain in the inevitable transformation of the social organization of pastoralists. There is no single recipe, and there can not be one for all countries and all groups of pastoralists all over the world.

One lesson from the recent failures to modernize mobile pastoralist economies in different countries, however, seems clear enough. The simplistic view that an increase in hvestock production and productivity is tantamount to the social development of pastoralists, is false (Mohamed Salih, 1990: 75). The concept of modernization is applicable to pastoralists only if they become an integrated part of a modem society; having not only a stake in the wider distribution of its benefits, but also a voice in decision making. Excessive paternalism, even a benevolent one, will not help as long as pastoralists continue to be treated as mere recipients of the “modernization package.” One may agree with those scholars who insist that attempts at transforming extensive pastoralism “from above,” initiated, designed and implemented by the state through purely administrative measures, are counterproductive. These bureaucratic actions are based on the false assumption that “whereas these people own livestock, they know very little about them and, therefore, have to be taught how to care for them” (Ndagala, 1990: 61; see also Hurskainen, 1990: 80).

Any development project should not be enforced but, at least, accepted by those to whom it is addressed. Pastoralists are quite capable of appreciating those innovations which they consider beneficial. The spread of trucks among the Bedouin of the Middle East or snowmobiles among the Saami of Scandinavia are only one of many indications of this. The pastoralists also usually welcome the introduction of improved veterinary and stock vaccinations. This proves the point: we will not have economic development until we permit, stimulate and encourage self-development.

During the last decades of the twentieth century we have witnessed how often development projects, sometimes advertised with great pomp, eventually turned out to be inadequate and ill-devised. In most development programs operations continued only for as long as donor funds were sustained (Oba, 1992: 69). However, as subsidies and support were provided, reduced, and finally withdrawn, governmental policies and priorities changed. In all such cases the ones at the losing end were almost invariably not the planners and bureaucrats but the pastoralists. They alone were left facing their deteriorating natural environment and had to pay the social cost for all decisions made without their consent. Therefore, without much hope that this will happen, I still hold that only when the views and expertise of the pastoralists themselves are taken into account and their own participation in the decision-making process is secured, may we expect any real success in their modernization.

In 1979, Gudrun Dahl (1979: 264) concluded her book on the Waso Borana pastoralists with the following words: “Will there still be resilience in the suffering grass? I would hope so, but can see no clear answer.” The question is still valid, and the answer is still unclear.

References

Abu-Rabia, Aref. The Negev Beduin and Livestock Rearing: Social, Economic and Political Aspects. Oxford/Providence: Berg Publishers, 1994.

Allan, W. The African Husbandman. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1976.

Arhem, K. Pastoral Man in the Garden of Eden: The Maasai of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Uppsala: Uppsala Research Reports on Cultural Anthropology, 1985.

Atherton, Lewis. The Cattle Kings. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1961.

Awogbade, Moses D. “Grazing Reserves in Nigeria.” Nomadic Peoples, 23 (1987): 19–30.

Back, Lennart. “Reindeer Management in Conflict and Co-Operation: A Geographic Land Use and Simulation Study from Northernmost Sweden.” Nomadic Peoples, 32 (1993): 65—80.