Julie Ault & James Benning

Two Cabins

Industrial Society and Its Future

INDUSTRIAL-TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY CANNOT BE REFORMED

RESTRICTION OF FREEDOM IS UNAVOIDARLE IN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

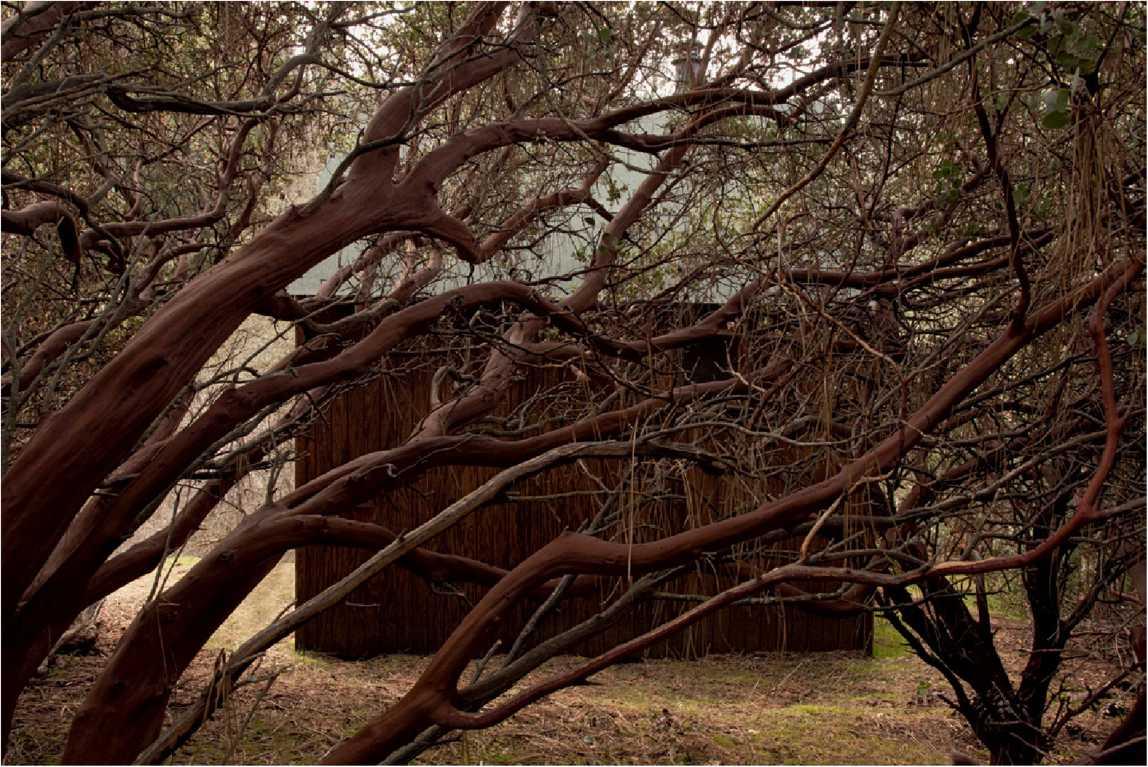

Henry David Thoreau Cabin, constructed July 2007 — January 2008

Ted Kaczynski Cabin, constructed April 2008 — June 2008

Kaczynski Cabin Library (11 Stacks, listed from bottom to top)

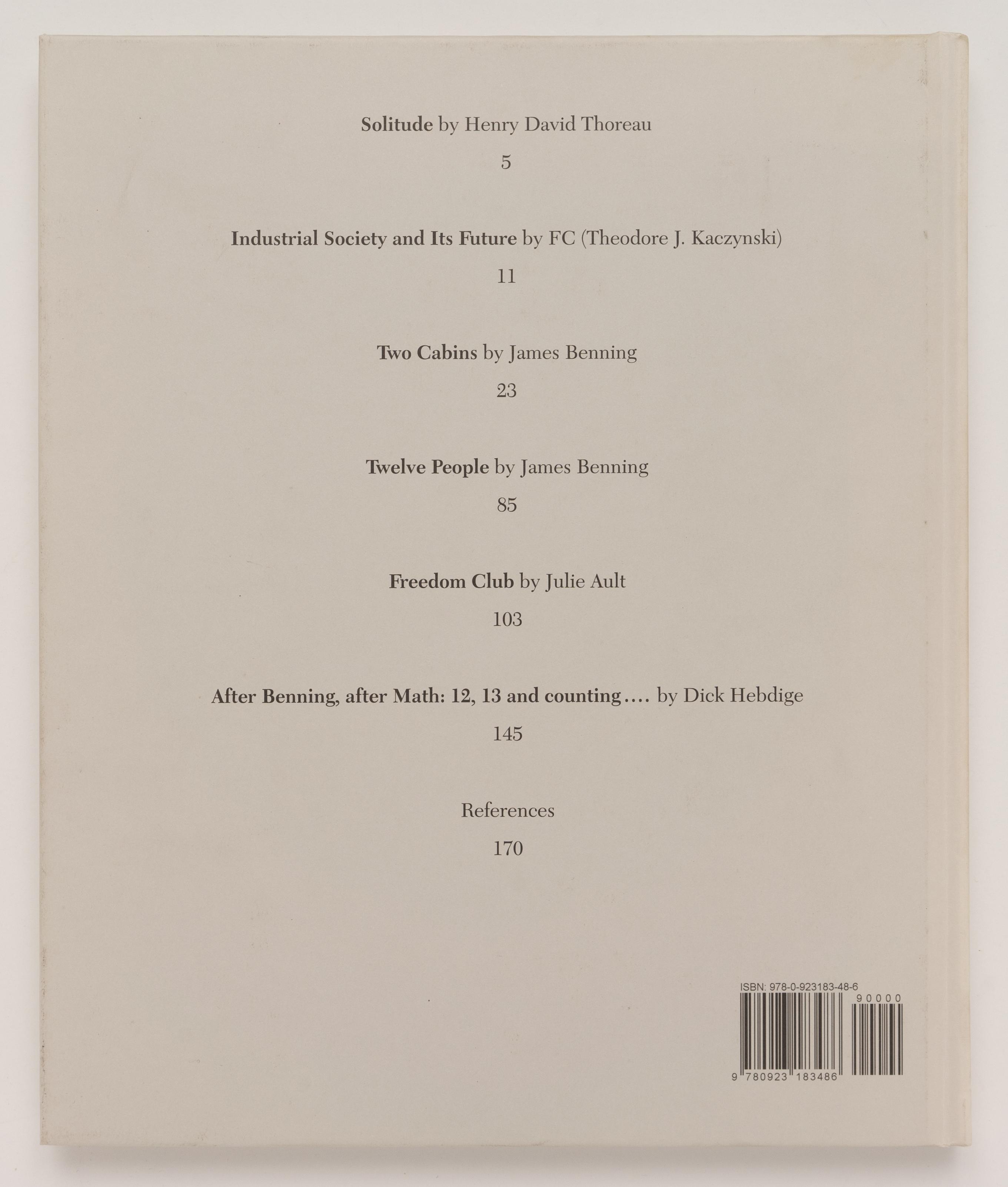

After Benning, after Math: 12, 13 and counting....

SQUARE ONE: 2 CABINS + CONTENTS

BOUNDARY FUNCTIONS: LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCUTION

BEAUTY + THE BLOOD = THE PLEASURE OF SEEING

EDEN AFTERMATH: CRAFT « CONTROL

SQUARED ROOTS: ONE IS THE UNIT NUMBER

(FC) Two Cabins by JB

A.R.T. Press

Edited by Julie Ault

Solitude

Henry David Thoreau

This is a delicious evening, when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every pore. I go and come with a strange liberty in Nature, a part of herself. As I walk along the stony shore of the pond in my shirt-sleeves, though it is cool as well as cloudy and windy, and I see nothing special to attract me, all the elements are unusually congenial to me. The bullfrogs trump to usher in the night, and the note of the whip-poor-will is borne on the rippling wind from over the water. Sympathy with the fluttering alder and poplar leaves almost takes away my breath; yet, like the lake, my serenity is rippled but not ruffled. These small waves raised by the evening wind are as remote from storm as the smooth reflecting surface. Though it is now dark, the wind still blows and roars in the wood, the waves still dash, and some creatures lull the rest with their notes. The repose is never complete. The wildest animals do not repose, but seek their prey now; the fox, and skunk, and rabbit, now roam the fields and woods without fear. They are Nature’s watchmen,—links which connect the days of animated life.

When I return to my house I find that visitors have been there and left their cards, either a bunch of flowers, or a wreath of evergreen, or a name in pencil on a yellow walnut leaf or a chip. They who come rarely to the woods take some little piece of the forest into their hands to play with by the way, which they leave, either intentionally or accidentally. One has peeled a willow wand, woven it into a ring, and dropped it on my table. I could always tell if visitors had called in my absence, either by the bended twigs or grass, or the print of their shoes, and generally of what sex or age or quality they were by some slight trace left, as a flower dropped, or a bunch of grass plucked and thrown away, even as far off as the railroad, half a mile distant, or by the lingering odor of a cigar or pipe. Nay, I was frequently notified of the passage of a traveller along the highway sixty rods off by the scent of his pipe.

There is commonly sufficient space about us. Our horizon is never quite at our elbows. The thick woods is not just at our door, nor the pond, but somewhat is always clearing, familiar and worn by us, appropriated and fenced in some way, and reclaimed from Nature. For what reason have I this vast range and circuit, some square miles of unfrequented forest, for my privacy, abandoned to me by men? My nearest neighbor is a mile distant, and no house is visible from any place but the hill-tops within half a mile of my own. I have my horizon bounded by woods all to myself; a distant view of the railroad where it touches the pond on the one hand, and of the fence which skirts the woodland road on the other. But for the most part it is solitary where I live as on the prairies. It is as much Asia or Africa as New England. I have, as it were, my own sun and moon and stars, and a little world all to myself. At night there was never a traveller passed my house, or knocked at my door, more than if I were the first or last man; unless it were in the spring, when at long intervals some came from the village to fish for pouts,—they plainly fished much more in the Walden Pond of their own natures, and baited their hooks with darkness,—but they soon retreated, usually with light baskets, and left “the world to darkness and to me,” and the black kernel of the night was never profaned by any human neighborhood. I believe that men are generally still a little afraid of the dark, though the witches are all hung, and Christianity and candles have been introduced.

Yet I experienced sometimes that the most sweet and tender, the most innocent and encouraging society may be found in any natural object, even for the poor misanthrope and most melancholy man. There can be no very black melancholy to him who lives in the midst of Nature and has his senses still. There was never yet such a storm but it was /Eolian music to a healthy and innocent ear. Nothing can rightly compel a simple and brave man to a vulgar sadness. While I enjoy the friendship of the seasons I trust that nothing can make life a burden to me. The gentle rain which waters my beans and keeps me in the house today is not drear and melancholy, but good for me too. Though it prevents my hoeing them, it is of far more worth than my hoeing. If it should continue so long as to cause the seeds to rot in the ground and destroy the potatoes in the low lands, it would still be good for the grass on the uplands, and, being good for the grass, it would be good for me. Sometimes, when I compare myself with other men, it seems as if I were more favored by the gods than they, beyond any deserts that I am conscious of; as if I had a warrant and surety at their hands which my fellows have not, and were especially guided and guarded. I do not flatter myself, but if it be possible they flatter me. I have never been lonesome, or in the least oppressed by a sense of solitude, but once, and that was a few weeks after I came to the woods, when, for an hour, I doubted if the near neighborhood of man was not essential to a serene and healthy life. To be alone was something unpleasant. But I was at the same time conscious of a slight insanity in my mood, and seemed to foresee my recovery. In the midst of a gentle rain while these thoughts prevailed, I was suddenly sensible of such sweet and beneficent society in Nature, in the very pattering of the drops, and in every sound and sight around my house, an infinite and unaccountable friendliness all at once like an atmosphere sustaining me, as made the fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant, and I have never thought of them since. Every little pine needle expanded and swelled with sympathy and befriended me. I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of something kindred to me, even in scenes which we are accustomed to call wild and dreary, and also that the nearest of blood to me and humanest was not a person nor a villager, that I thought no places could ever be strange to me again.—

“Mourning untimely consumes the sad;

Few are their days in the land of the living,

Beautiful daughter of Tosca.”

Some of my pleasantest hours were during the long rain-storms in the spring or fall, which confined me to the house for the afternoon as well as the forenoon, soothed by their ceaseless roar and pelting; when an early twilight ushered in a long evening in which many thoughts had time to take root and unfold themselves. In those driving northeast rains which tried the village houses so, when the maids stood ready with mop and pail in front entries to keep the deluge out, I sat behind my door in my little house, which was all entry, and thoroughly enjoyed its protection. In one heavy thunder-shower the lightning struck a large pitch pine across the pond, making a very conspicuous and perfectly regular spiral groove from top to bottom, an inch or more deep, and four or five inches wide, as you would groove a walking-stick. I passed it again the other day, and was struck with awe on looking up and beholding that mark, now more distinct than ever, where a terrific and resistless bolt came down out of the harmless sky eight years ago. Men frequently say to me, “I should think you would feel lonesome down there, and want to be nearer to folks, rainy and snowy days and nights especially.” I am tempted to reply to such,—This whole earth which we inhabit is but a point in space. How far apart, think you, dwell the two most distant inhabitants of yonder star, the breadth of whose disk cannot be appreciated by our instruments? Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way? This which you put seems to me not to be the most important question. What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another. What do we want most to dwell near to? Not to many men surely, the depot, the post-office, the bar-room, the meeting-house, the school-house, the grocery, Beacon Hill, or the Five Points, where men most congregate, but to the perennial source of our life, whence in all our experience we have found that to issue, as the willow stands near the water and sends out its roots in that direction. This will vary with different natures, but this is the place where a wise man will dig his cellar.... I one evening overtook one of my townsmen, who has accumulated what is called “a handsome property,”—though I never got a fair view of it,—on the Walden road, driving a pair of cattle to market, who inquired of me how I could bring my mind to give up so many of the comforts of life. I answered that I was very sure I liked it passably well; I was not joking. And so I went home to my bed, and left him to pick his way through the darkness and the mud to Brighton,—or Bright- town,—which place he would reach some time in the morning.

Any prospect of awakening or coming to life to a dead man makes indifferent all times and places. The place where that may occur is always the same, and indescribably pleasant to all our senses. For the most part we allow only outlying and transient circumstances to make our occasions. They are, in fact, the cause of our distraction. Nearest to all things is that power which fashions their being. Next to us the grandest laws are continually being executed. Next to us is not the workman whom we have hired, with whom we love so well to talk, but the workman whose work we are.

”How vast and profound is the influence of the subtile powers of Heaven and of Earth!”

”We seek to perceive them, and we do not see them; we seek to hear them, and we do not hear them; identified with the substance of things, they cannot be separated from them.”

”They cause that in all the universe men purify and sanctify their hearts, and clothe themselves in their holiday garments to offer sacrifices and oblations to their ancestors. It is an ocean of subtile intelligences. They are everywhere, above us, on our left, on our right; they environ us on all sides.”

We are the subject of an experiment which is not a little interesting to me. Can we not do without the society of our gossips a little while under these circumstances,—have our own thoughts to cheer us? Confucius says truly, “Virtue does not remain as an abandoned orphan; it must of necessity have neighbors.”

With thinking we may be beside ourselves in a sane sense. By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent. We are not wholly involved in Nature. I may be affected by a theatrical exhibition; on the other hand, I may not be affected by an actual event which appears to concern me much more. I only know myself as a human entity; the scene, so to speak, of thoughts and affections; and am sensible of a certain doubleness by which I can stand as remote from myself as from another. However intense my experience, I am conscious of the presence and criticism of a part of me, which, as it were, is not a part of me, but a spectator, sharing no experience, but taking note of it, and that is no more I than it is you. When the play, it may be the tragedy, of life is over, the spectator goes his way. I was a kind of fiction, a work of the imagination only, so far as he was concerned. This doubleness may easily make us poor neighbors and friends sometimes.

I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time. To be in company, even with the best, is soon wearisome and dissipating. I love to be alone. I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers. A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be where he will. Solitude is not measured by the miles of space that intervene between a man and his fellows. The really diligent student in one of the crowded hives of Cambridge College is as solitary as a dervish in the desert. The farmer can work alone in the field or the woods all day, hoeing or chopping, and not feel lonesome, because he is employed; but when he comes home at night he cannot sit down in a room alone, at the mercy of his thoughts, but must be where he can “see the folks,” and recreate, and, as he thinks, remunerate himself for his day’s solitude: and hence he wonders how the student can sit alone in the house all night and most of the day without ennui and “the blues” but he does not realize that the student, though in the house, is still at work in his field, and chopping in his woods, as the farmer in his, and in turn seeks the same recreation and society that the latter does, though it may be a more condensed form of it.

Society is commonly too cheap. We meet at very short intervals, not having had time to acquire any new value for each other. We meet at meals three times a day, and give each other a new taste of that musty cheese that we are. We have had to agree on a certain set of rules, called etiquette and politeness, to make this frequent meeting tolerable and that we need not come to open war. We meet at the post-office, and at the sociable, and about the fireside every night; we live thick and are in each other’s way, and stumble over one another, and I think that we thus lose some respect for one another. Certainly less frequency would suffice for all important and hearty communications. Consider the girls in a factory,— never alone, hardly in their dreams. It would be better if there were but one inhabitant to a square mile, as where I live. The value of a man is not in his skin, that we should touch him.

I have heard of a man lost in the woods and dying of famine and exhaustion at the foot of a tree, whose loneliness was relieved by the grotesque visions with which, owing to bodily weakness, his diseased imagination surrounded him, and which he believed to be real. So also, owing to bodily and mental health and strength, we may be continually cheered by a like but more normal and natural society, and come to know that we are never alone.

I have a great deal of company in my house; especially in the morning, when nobody calls. Let me suggest a few comparisons, that some one may convey an idea of my situation. I am no more lonely than the loon in the pond that laughs out loud, or than Walden Pond itself. What company has that lonely lake, I pray? And yet it has not the blue devils, but the blue angels in it, in the azure tint of its waters. The sun is alone, except in thick weather, when there sometimes appear to be two, but one is a mock sun. God is alone,—but the devil, he is far from being alone; he sees a great deal of company; he is legion. I am no more lonely than a single mullein or dandelion in a pasture, or a bean leaf, or sorrel, or a horse-fly, or a bumblebee. I am no more lonely than the Mill Brook, or a weathercock, or the north star, or the south wind, or an April shower, or a January thaw, or the first spider in a new house.

I have occasional visits in the long winter evenings, when the snow falls fast and the wind howls in the wood, from an old settler and original proprietor, who is reported to have dug Walden Pond, and stoned it, and fringed it with pine woods; who tells me stories of old time and of new eternity; and between us we manage to pass a cheerful evening with social mirth and pleasant views of things, even without apples or cider,—a most wise and humorous friend, whom I love much, who keeps himself more secret than ever did Goffe or Whalley; and though he is thought to be dead, none can show where he is buried. An elderly dame, too, dwells in my neighborhood, invisible to most persons, in whose odorous herb garden I love to stroll sometimes, gathering simples and listening to her fables; for she has a genius of unequalled fertility, and memory runs back farther than mythology, and she can tell me the original of every fable, and on what fact every one is founded, for the incidents occurred when she was young. A ruddy and lusty old dame who delights in all weathers and seasons, and is likely to outlive all her children yet.

The indescribable innocence and beneficence of Nature,—of sun and wind and rain, of summer and winter,—such health, such cheer, they afford forever! and such sympathy have they ever with our race, that all Nature would be affected, and the sun’s brightness fade, and the winds would sigh humanely, and the clouds rain tears, and the woods shed their leaves and put on mourning in midsummer, if any man should ever for a just cause grieve. Shall I not have intelligence with the earth? Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?

What is the pill which will keep us well, serene, contented? Not my or thy great-grandfather’s, but our great-grandmother Nature’s universal, vegetable, botanic medicines, by which she has kept herself young always, outlived so many old Parrs in her day, and fed her health with their decaying fatness. For my panacea, instead of one of those quack vials of a mixture dipped from Acheron and the Dead Sea, which come out of those long shallow black-schooner looking wagons which we sometimes see made to carry bottles, let me have a draught of undiluted morning air. Morning air! If men will not drink of this at the fountainhead of the day, why, then, we must even bottle up some and sell it in the shops, for the benefit of those who have lost their subscription ticket to morning time in this world. But remember, it will not keep quite till noonday even in the coolest cellar, but drive out the stopples long ere that and follow westward the steps of Aurora. I am no worshipper of Hygeia, who was the daughter of that old herb-doctor/Esculapius, and who is represented on monuments holding a serpent in one hand, and in the other a cup out of which the serpent sometimes drinks; but rather of Hebe, cup-bearer to Jupiter, who was the daughter of Juno and wild lettuce, and who had the power of restoring gods and men to the vigor of youth. She was probably the only thoroughly sound-conditioned, healthy, and robust young lady that ever walked the globe, and wherever she came it was spring.

Industrial Society and Its Future

FC (Theodore J. Kaczynski)

THE NATURE OF FREEDOM

93. We are going to argue that industrial-technological society cannot be reformed in such a way as to prevent it from progressively narrowing the sphere of human freedom. But because “freedom” is a word that can be interpreted in many ways, we must first make clear what kind of freedom we are concerned with.

94. By “freedom” we mean the opportunity to go through the power process, with real goals not the artificial goals of surrogate activities, and without interference, manipulation or supervision from anyone, especially from any large organization. Freedom means being in control (either as an individual or as a member of a SMALL group) of the life-and-death issues of one’s existence: food, clothing, shelter and defense against whatever threats there may be in one’s environment. Freedom means having power; not the power to control other people but the power to control the circumstances of one’s own life. One does not have freedom if anyone else (especially a large organization) has power over one, no matter how benevolently, tolerantly and permissively that power may be exercised. It is important not to confuse freedom with mere permissiveness (see paragraph 72).

95. It is said that we live in a free society because we have a certain number of constitutionally guaranteed rights. But those are not as important as they seem. The degree of personal freedom that exists in a society is determined more by the economic and technological structure of the society than by its laws or its form of government.[1] Most of the Indian nations of New England were monarchies, and many of the cities of the Italian Renaissance were controlled by dictators. But in reading about these societies one gets the impression that they allowed far more personal freedom than our society does. In part this was because they lacked efficient mechanisms for enforcing the ruler’s will: There were no modern, well- organized police forces, no rapid long-distance communications, no surveillance cameras, no dossiers of information about the lives of average citizens. Hence it was relatively easy to evade control.

96. As for our constitutional rights, consider for example that of freedom of the press. We certainly don’t mean to knock that right; it is a very important tool for limiting concentration of political power and for keeping those who do not have political power in line by publicly exposing any misbehavior on their part. But freedom of the press is of very little use to the average citizen as an individual. The mass media are mostly under the control of large organizations that are integrated into the system. Anyone who has a little money can have something printed, or can distribute it on the Internet or in some such way, but what he has to say will be swamped by the vast volume of material put out by the media, hence it will have no practical effect. To make an impression on society with words is therefore almost impossible for most individuals and small groups. Take us (FC) for example. If we had never done anything violent and had submitted the present writings to a publisher, they probably would not have been accepted. If they had been accepted and published, they probably would not have attracted many readers, because it’s more fun to watch the entertainment put out by the media than to read a sober essay. Even if these writings had had many readers, most of these readers would soon have forgotten what they had read as their minds were flooded by the mass of material to which the media expose them. In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression, we’ve had to kill people.

97. Constitutional rights are useful up to a point, but they do not serve to guarantee much more than what could be called the bourgeois conception of freedom. According to the bourgeois conception, a “free” man is essentially an element of a social machine and has only a certain set of prescribed and delimited freedoms; freedoms that are designed to serve the needs of the social machine more than those of the individual. Thus the bourgeois’s “free” man has economic freedom because that promotes growth and progress; he has freedom of the press because public criticism restrains misbehavior by political leaders; he has a right to a fair trial because imprisonment at the whim of the powerful would be bad for the system. This was clearly the attitude of Simon Bolivar. To him, people deserved liberty only if they used it to promote progress (progress as conceived by the bourgeois). Other bourgeois thinkers have taken a similar view of freedom as a mere means to collective ends. Chester C. Tan, Chinese Political Thought in the Twentieth Century, page 202, explains the philosophy of the Kuomingtang leader Hu Han-min: “An individual is granted rights because he is a member of society and his community life requires such rights. By community Hu meant the whole society of the nation.” And on page 259 Tan states that according to Carsun Chang (Chang Chun-Mai, head of the State Socialist Party in China) freedom had to be used in the interest of the state and of the people as a whole. But what kind of freedom does one have if one can use it only as someone else prescribes? FC’s conception of freedom is not that of Bolivar, Hu, Chang or other bourgeois theorists. The trouble with such theorists is that they have made the development and application of social theories their surrogate activity. Consequently the theories are designed to serve the needs of the theorists more than the needs of any people who may be unlucky enough to live in a society on which the theories are imposed.

98. One more point to be made in this section: It should not be assumed that a person has enough freedom just because he SAYS he has enough. Freedom is restricted in part by psychological controls of which people are unconscious, and moreover many people’s ideas of what constitutes freedom are governed more by social convention than by their real needs. For example, it’s likely that many leftists of the oversocialized type would say that most people, including themselves, are socialized too little rather than too much, yet the oversocialized leftist pays a heavy psychological price for his high level of socialization.

SOME PRINCIPLES OF HISTORY

99. Think of history as being the sum of two components: an erratic component that consists of unpredictable events that follow no discernible pattern, and a regular component that consists of long-term historical trends. Here we are concerned with the long-term trends.

100. FIRST PRICINPLE. If a SMALL change is made that affects a long-term historical trend, then the effect of that change will almost always be transitory— the trend will soon revert to its original state. (Example: A reform movement designed to clean up political corruption in a society rarely has more than a shortterm effect; sooner or later the reformers relax and corruption creeps back in. The level of political corruption in a given society tends to remain constant, or to change only slowly with the evolution of the society. Normally, a political cleanup will be permanent only if accompanied by widespread social changes; a SMALL change in the society won’t be enough.) If a small change in a long-term historical trend appears to be permanent, it is only because the change acts in the direction in which the trend is already moving, so that the trend is not altered but only pushed a step ahead.

101. The first principle is almost a tautology. If a trend were not stable with respect to small changes, it would wander at random rather than following a definite direction; in other words it would not be a long-term trend at all.

102. SECOND PRINCIPLE. If a change is made that is sufficiently large to alter permanently a long-term historical trend, then it will alter the society as a whole. In other words, a society is a system in which all parts are interrelated, and you can’t permanently change any important part without changing all the other parts as well.

103. THIRD PRINCIPLE. If a change is made that is large enough to alter errantly a long-term trend, then the consequences for the society as a whole cannot be predicted in advance. (Unless various other societies have passed through the same change and have all experienced the same consequences, in which case one can predict on empirical grounds that another society that passes through the same change will be likely to experience similar consequences.)

104. FOURTH PRINCIPLE. A new kind of society cannot be designed on paper. That is, you cannot plan out a new form of society in advance, then set it up and expect it to function as it was designed to do.

105. The third and fourth principles result from the complexity of human societies. A change in human behavior will affect the economy of a society and its physical environment; the economy will affect the environment and vice versa, and the changes in the economy and the environment will affect human behavior in complex, unpredictable ways; and so forth. The network of causes and effects is far too complex to be untangled and understood.

106. FIFTH PRINCIPLE. People do not consciously and rationally choose the form of their society. Societies develop through processes of social evolution that are not under rational human control.

107. The fifth principle is a consequence of the other four.

108. To illustrate: By the first principle, generally speaking an attempt at social reform either acts in the direction in which the society is developing anyway (so that it merely accelerates a change that would have occurred in any case) or else it only has a transitory effect, so that the society soon slips back into its old groove. To make a lasting change in the direction of the development of any important aspect of a society, reform is insufficient and revolution is required. (A revolution does not necessarily involve an armed uprising or the overthrow of a government.) By the second principle, a revolution never changes only one aspect of a society; and by the third principle changes occur that were never expected or desired by the revolutionaries. By the fourth principle, when revolutionaries or Utopians set up a new kind of society, it never works out as planned.

109. The American Revolution does not provide a counterexample. The American “Revolution” was not a revolution in our sense of the word, but a war of independence followed by a rather far-reaching political reform. The Founding Fathers did not change the direction of development of American society, nor did they aspire to do so. They only freed the development of American society from the retarding effect of British rule. Their political reform did not change any basic trend, but only pushed American political culture along its natural direction of development. British society, of which American society was an offshoot, had been moving for a long time in the direction of representative democracy. And prior to the War of Independence the Americans were already practicing a significant degree of representative democracy in the colonial assemblies. The political system established by the Constitution was modeled on the British system and on the colonial assemblies, with major alteration, to be sure—there is no doubt that the Founding Fathers took a very important step. But it was a step along the road the English-speaking world was already traveling. The proof is that Britain and all of its colonies that were populated predominantly by people of British descent ended up with systems of representative democracy essentially similar to that of the United States. If the Founding Fathers had lost their nerve and declined to sign the Declaration of Independence, our way of life today would not have been significantly different. Maybe we would have had somewhat closer ties to Britain, and would have had a Parliament and Prime Minister instead of a Congress and President. No big deal. Thus the American Revolution provides not a counterexample to our principles but a good illustration of them.

110. Still, one has to use common sense in applying the principles. They are expressed in imprecise language that allows latitude for interpretation, and exceptions to them can be found. So we present these principles not as inviolable laws but as rules of thumb, or guides to thinking, that may provide a partial antidote to naive ideas about the future of society. The principles should be borne constantly in mind, and whenever one reaches a conclusion that conflicts with them one should carefully reexamine one’s thinking and retain the conclusion only if one has good, solid reasons for doing so.

INDUSTRIAL-TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY CANNOT BE REFORMED

111. The foregoing principles help to show how hopelessly difficult it would be to reform the industrial system in such a way as to prevent it from progressively narrowing our sphere of freedom. There has been a consistent tendency, going back at least to the Industrial Revolution, for technology to strengthen the system at a high cost in individual freedom and local autonomy. Hence any change designed to protect freedom from technology would be contrary to a fundamental trend in the development of our society. Consequently, such a change would either be a transitory one—soon swamped by the tide of history—or, if large enough to be permanent, would alter the nature of our whole society. This by the first and second principles. Moreover, since society would be altered in a way that could not be predicted in advance (third principle) there would be great risk. Changes large enough to make a lasting difference in favor of freedom would not be initiated because it would be realized that they would gravely disrupt the system. So any attempts at reform would be too timid to be effective. Even if changes large enough to make a lasting difference were initiated, they would be retracted when their disruptive effects became apparent. Thus, permanent changes in favor of freedom could be brought about only by persons prepared to accept radical, dangerous and unpredictable alteration of the entire system. In other words, by revolutionaries, not reformers.

112. People anxious to rescue freedom without sacrificing the supposed benefits of technology will suggest naive schemes for some new form of society that would reconcile freedom with technology. Apart from the fact that people who make suggestions seldom propose any practical means by which the new form of society could be set up in the first place, it follows from the fourth principle that even if the new form of society could be once established, it either would collapse or would give results very different from those expected.

113. So even on very general grounds it seems highly improbable that any way of changing society could be found that would reconcile freedom with modern technology. In the next few sections we will give more specific reasons for concluding that freedom and technological progress are incompatible.

RESTRICTION OF FREEDOM IS UNAVOIDARLE IN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

114. As explained in paragraphs 65–67, 70–73, modern man is strapped down by a network of rules and regulations, and his fate depends on the actions of persons remote from him whose decisions he cannot influence. This is not accidental or a result of the arbitrariness of arrogant bureaucrats. It is necessary and inevitable in any technologically advanced society. The system HAS TO regulate human behavior closely in order to function. At work, people have to do what they are told to do, otherwise production would be thrown into chaos. Bureaucracies HAVE TO be run according to rigid rules. To allow any substantial personal discretion to lower-level bureaucrats would disrupt the system and lead to charges of unfairness due to differences in the way individual bureaucrats exercised their discretion. GENERALLY SPEAKING the regulation of our lives by large organizations is necessary for the functioning of industrial-technological society. The result is a sense of powerlessness on the part of the average person. It may be, however, that formal regulations will tend increasingly to be replaced by psychological tools that make us want to do what the system requires of us. (Propaganda, educational techniques, “mental health” programs, etc.)

115. The system HAS TO force people to behave in ways that are increasingly remote from the natural pattern of human behavior. For example, the system needs scientists, mathematicians and engineers. It can’t function without them. So heavy pressure is put on children to excel in these fields. It isn’t natural for an adolescent human being to spend the bulk of his time sitting at a desk absorbed in study. A normal adolescent wants to spend his time in active contact with the real world. Among primitive peoples the things that children are trained to do tend to be in reasonable harmony with natural human impulses. Among the American Indians, for example, boys were trained in active outdoor pursuits—just the sort of things that boys like. But in our society children are pushed into studying technical subjects, which most do grudgingly.

116. Because of the constant pressure that the system exerts to modify human behavior, there is a gradual increase in the number of people who cannot or will not adjust to society’s requirements: welfare leeches, youth-gang members, cultists, anti-government rebels, radical environmentalist saboteurs, dropouts and resisters of various kinds.

117. In any technologically advanced society the individual’s fare MUST depend on decisions that he personally cannot influence to any great extent. A technological society cannot be broken down into small, autonomous communities, because production depends on the cooperation of very large numbers of people and machines. Such a society MUST be highly organized and decisions HAVE TO be made that affect very large numbers of people. When a decision affects, say, a million people, then each of the affected individuals has, on the average, only a one-millionth share in making the decision. What usually happens in practice is that decisions are made by public officials or corporation executives, or by technical specialists, but even when the public votes on a decision the number of voters ordinarily is too large for the vote of any one individual to be significant.[2] Thus most individuals are unable to influence measurably the major decisions that affect their lives. There is no conceivable way to remedy this in a technologically advanced society. The system tries to “solve” this problem by using propaganda to make people WANT the decisions that have been made for them, but even if this “solution” were completely successful in making people feel better, it would be demeaning.

118. Conservatives and some others advocate more “local autonomy.” Local communities once did have autonomy, but such autonomy becomes less and less possible as local communities become more enmeshed with and dependent on large-scale systems like public utilities, computer networks, highway systems, and mass communications media and the modern health-care system. Also operating against autonomy is the fact that technology applied in one location often affects people at other locations far away. Thus pesticide or chemical use near a creek may contaminate the water supply hundreds of miles downstream, and the greenhouse effect affects the whole world.

119. The system does not and cannot exist to satisfy human needs. Instead, it is human behavior that has to be modified to fit the needs of the system. This has nothing to do with the political or social ideology that may pretend to guide the technological system. It is not the fault of capitalism and it is not the fault of socialism. It is the fault of technology, because the system is guided not by ideology but by technological necessity.[3] Of course the system does satisfy many human needs, but generally speaking it does this only to the extent that it is to the advantage of the system to do it. It is the needs of the system that are paramount, not those of the human being. For example, the system provides people with food because the system couldn’t function if everyone starved; it attends to people’s psychological needs whenever it can CONVENIENTLY do so, because it couldn’t function if too many people became depressed or rebellious. But the system, for good, solid, practical reasons, must exert constant pressure on people to mold their behavior to the needs of the system. Too much waste accumulating? The government, the media, the educational system, environmentalists, everyone inundates us with a mass of propaganda about recycling. Need more technical personnel? A chorus of voices exhorts kids to study science. No one stops to ask whether it is inhumane to force adolescents to spend the bulk of their time studying subjects most of them hate. When skilled workers are put out of a job by technical advances and have to undergo “retraining,” no one asks whether it is humiliating for them to be pushed around in this way. It is simply taken for granted that everyone must bow to technical necessity. And for good reason: If human needs were put before technical necessity there would be economic problems, unemployment, shortages or worse. The concept of “mental health” in our society is defined largely by the extent to which an individual behaves in accord with the needs of the system and does so without showing signs of stress.

120. Efforts to make room for a sense of purpose and for autonomy within the system are no better than a joke. For example, one company, instead of having each of its employees assemble only one section of a catalogue, had each assemble a whole catalogue, and this was supposed to give them a sense of purpose and achievement. Some companies have tried to give their employees more autonomy in their work, but for practical reasons this usually can be done only to a very limited extent, and in any case employees are never given autonomy as to ultimate goals—their “autonomous” efforts can never be directed toward goals that they select personally, but only toward their employer’s goals, such as the survival and growth of the company. Any company would soon go out of business if it permitted its employees to act otherwise. Similarly, in any enterprise within a socialist system, workers must direct their efforts toward the goals of the enterprise, otherwise the enterprise will not serve its purpose as part of the system. Once again, for purely technical reasons it is not possible for most individuals or small groups to have much autonomy in industrial society. Even the small-business owner commonly has only limited autonomy. Apart from the necessity of government regulation, he is restricted by the fact that he must fit into the economic system and conform to its requirements. For instance, when someone develops a new technology, the small business person often has to use that technology whether he wants to or not, in order to remain competitive.

Two Cabins

Henry David Thoreau Cabin, constructed July 2007 — January 2008

Dimensions

Outside: 14 ft. 4 in. x 10 ft. 4 in., peak: 14 ft.

Inside: 13 ft. 5 in. x 9 ft. 5 in., ceiling: 7 ft. 4 in.

Two windows: 5 ft. 6 in. x 3 ft., 14 in. off floor, centered

Door: 80 in. x 36 in., front, centered

Fireplace: rear wall, centered

Paintings

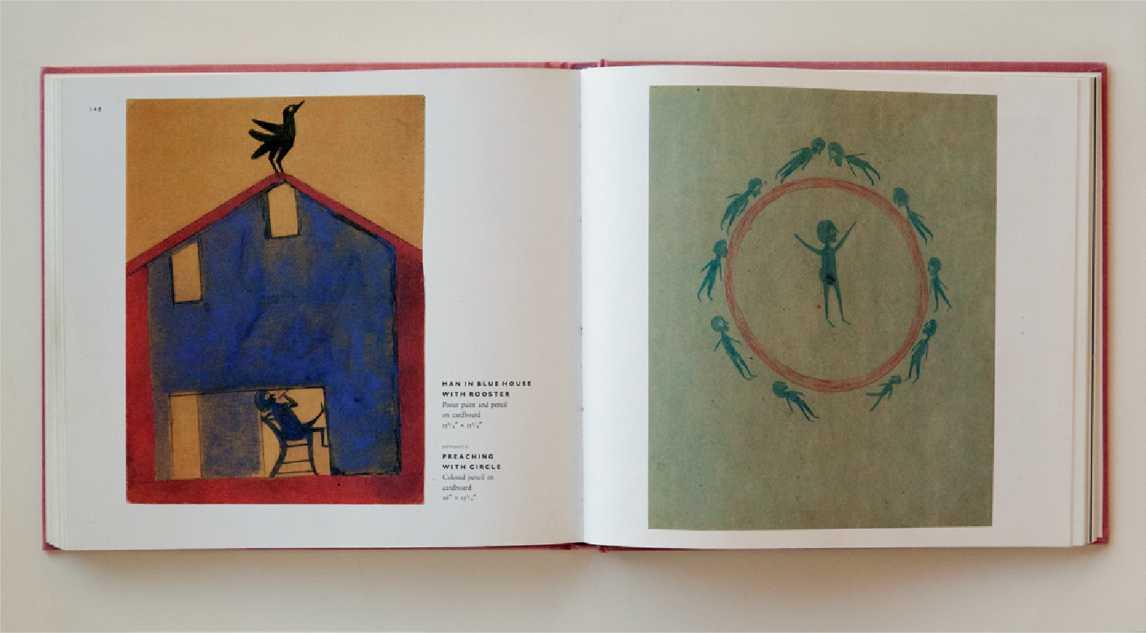

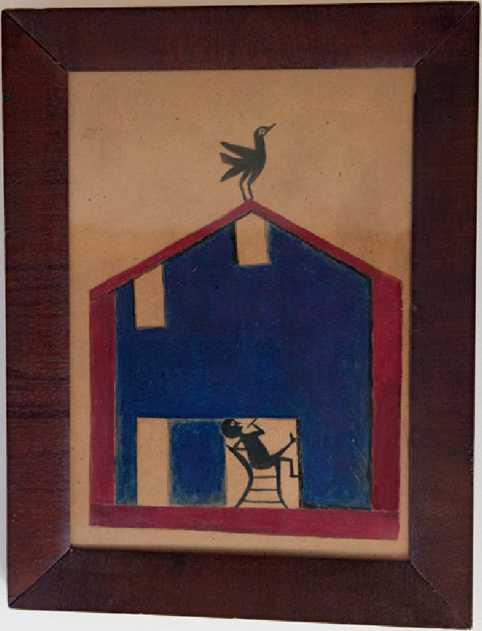

Bill Traylor

Untitled (Man in Blue House with Rooster), 1939–43

Pencil, poster paint on found cardboard 13 in. x 10 in.

Untitled (Blue Construction with Two

Figures and Dog), 1939–43

Pencil, poster paint on found cardboard 13 in. x 7 in.

Untitled (Female Drinker), 1939–43

Pencil, poster paint on found cardboard 12 in. x 9 in.

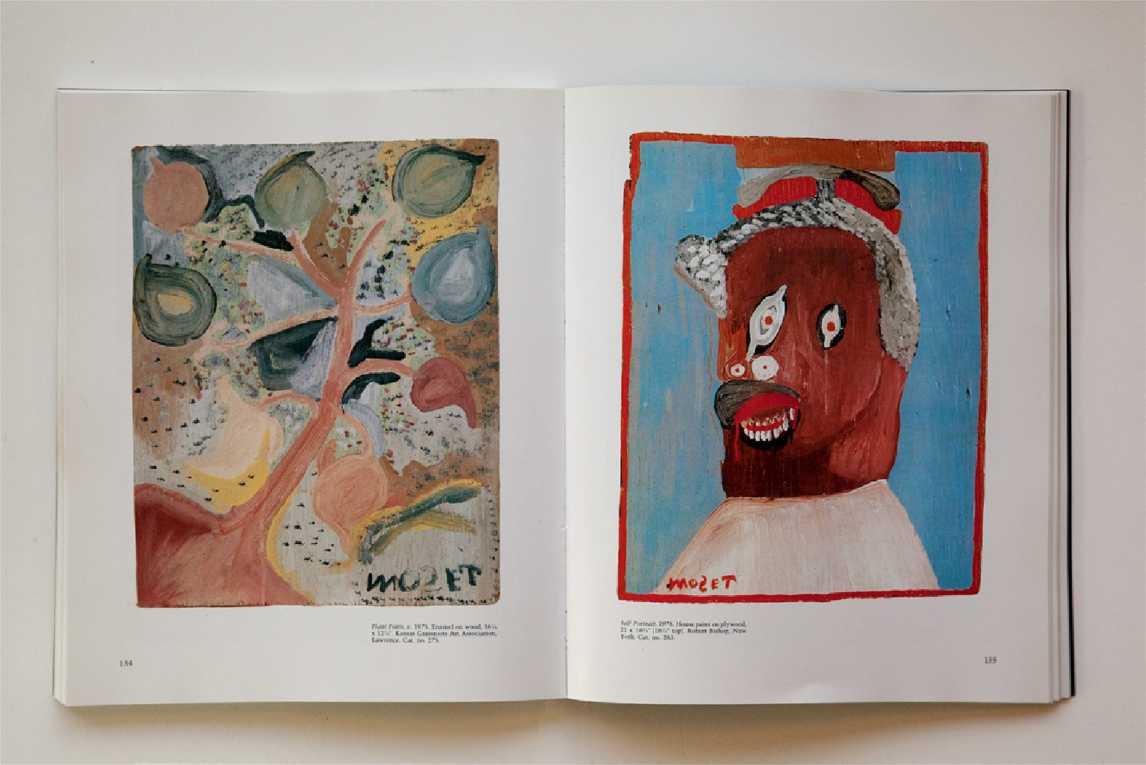

Mose Tolliver

Self Portrait, 1978

House paint on plywood

21 in. x 17 in.

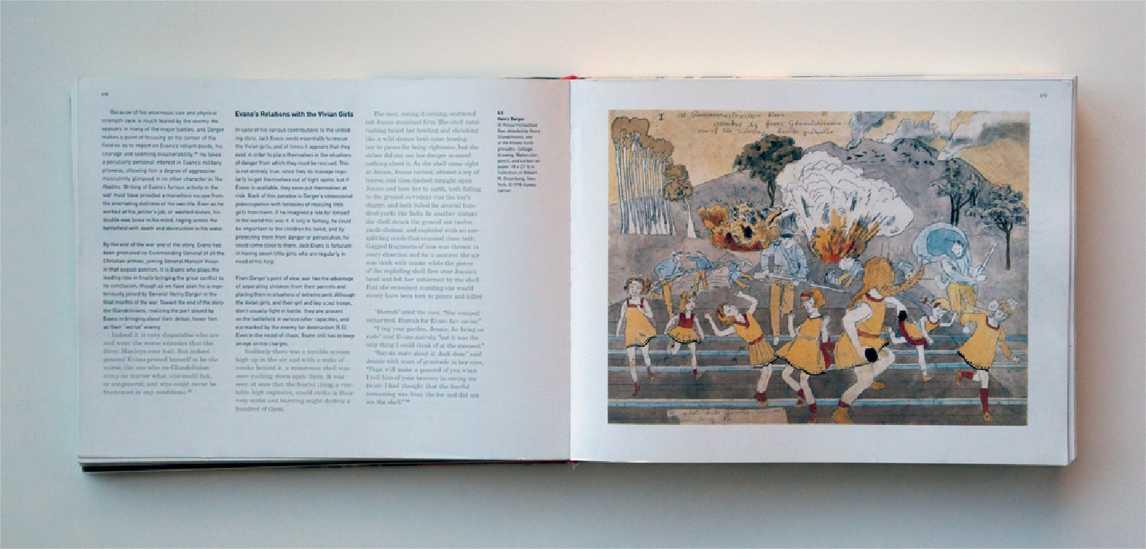

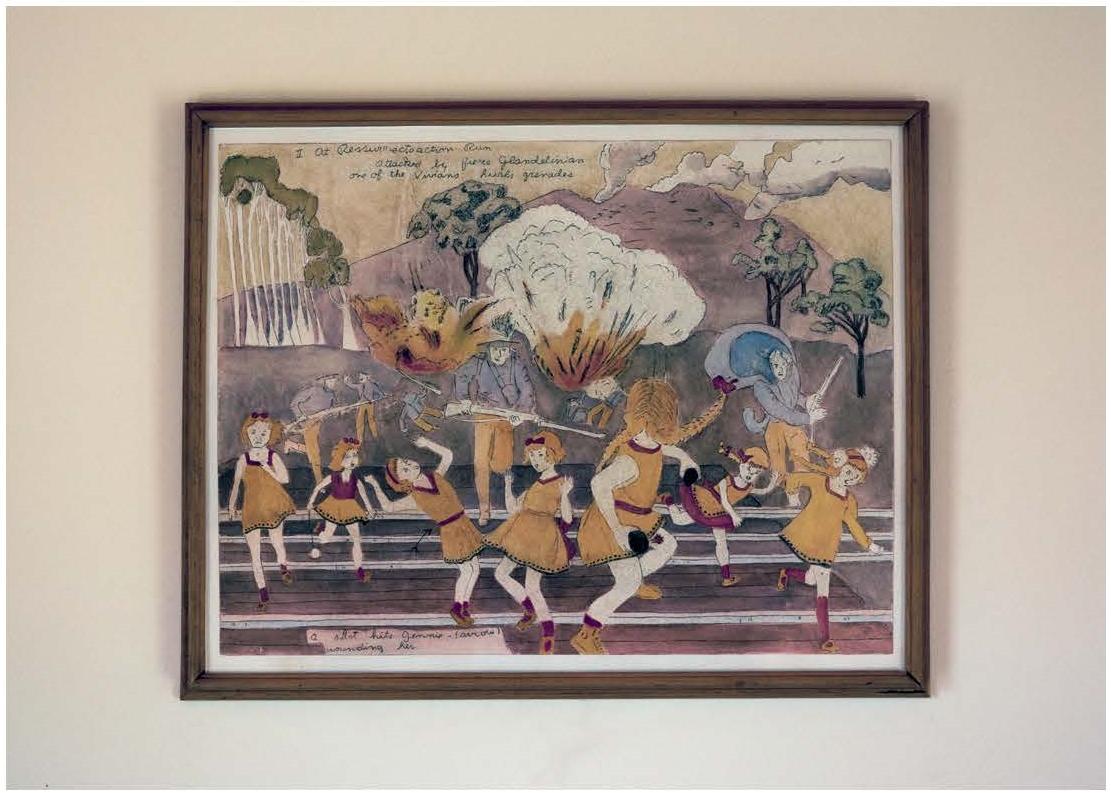

Henry Darger

At Ressurrectoation Run. Attacked by Fierce Glandelinians, One of the Vivians Hurls Grenades, c. 1960

Carbon, watercolor on manila paper 18 in. x 23 in.

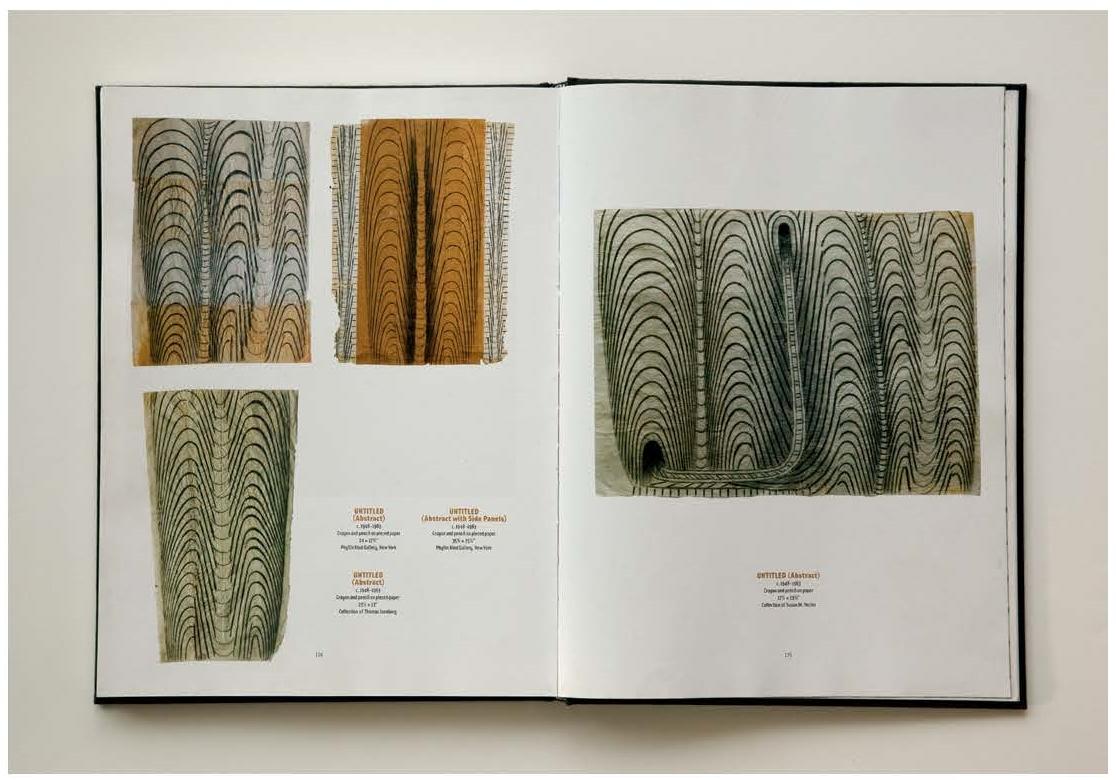

Martin Ramirez

Untitled (Train tracks with two tunnels), 1948–1963

Crayon, pencil on handmade paper

18 in. x 24 in.

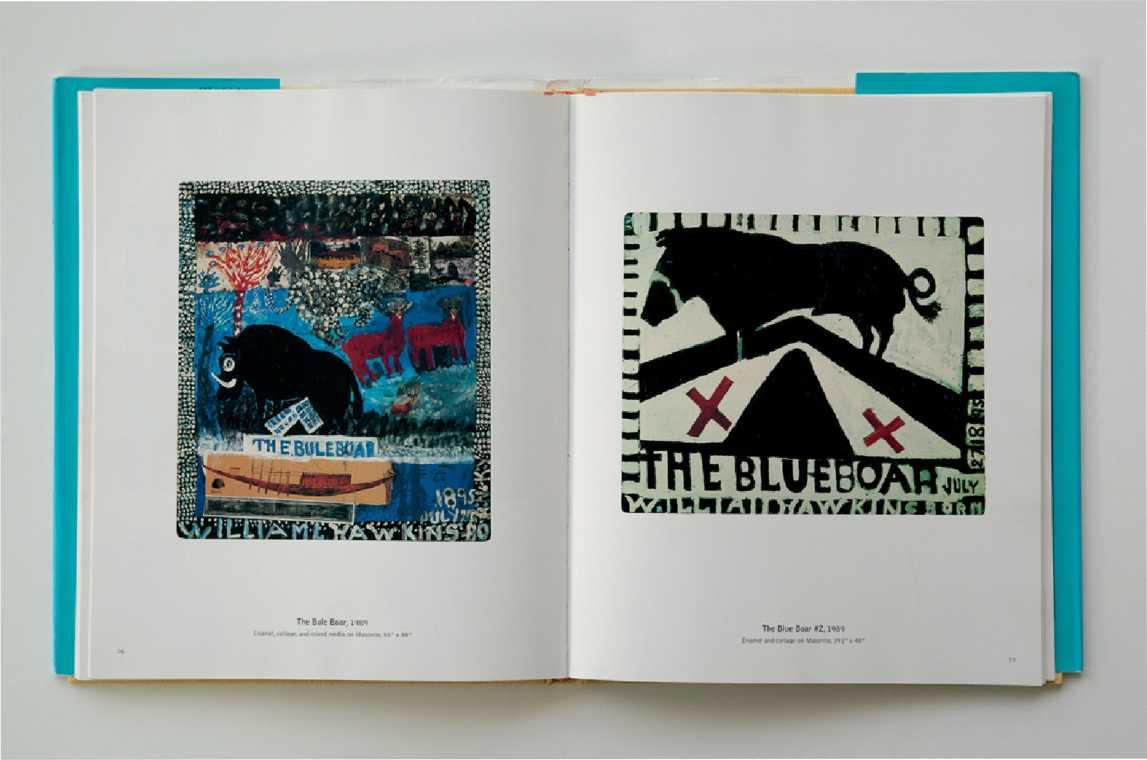

William Hawkins

The Blue Boar #2, 1989

Enamel on masonite

16 in. x 19 x/2 in.

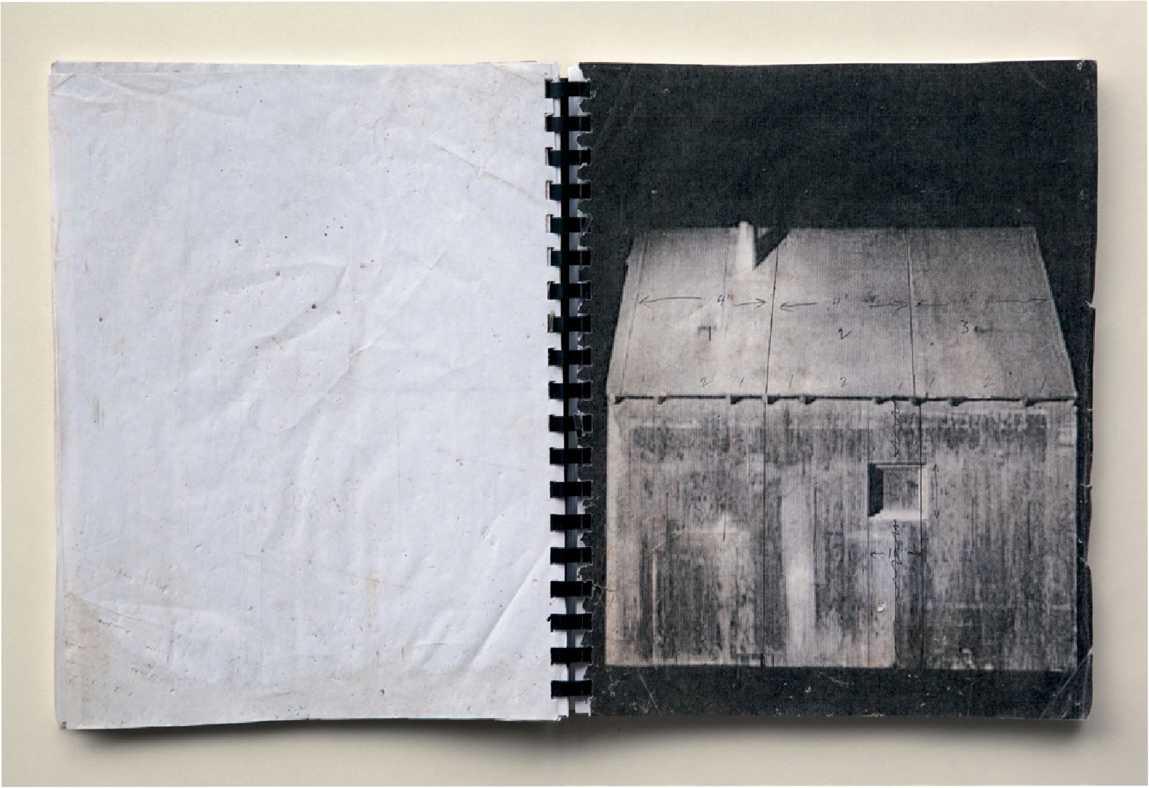

Ted Kaczynski Cabin, constructed April 2008 — June 2008

Dimensions

Outside: 12 ft. 1 in. x 10 ft. 2 in., peak: 12 ft. 9 in.

Inside: 11 ft. 4 in. x 9 ft. 4 in., ceiling: 6 ft. 9 in.

Two windows: 18 in. square, left side: 39 in. off floor, 44 in. from front;

right side: 59 in. off floor, 30 in. from rear

Door: 76 in. x 26 in., front, centered

Bookshelf: left side, 9 ft. 10 in. x 8% in.

Woodstove: rear left

Paintings

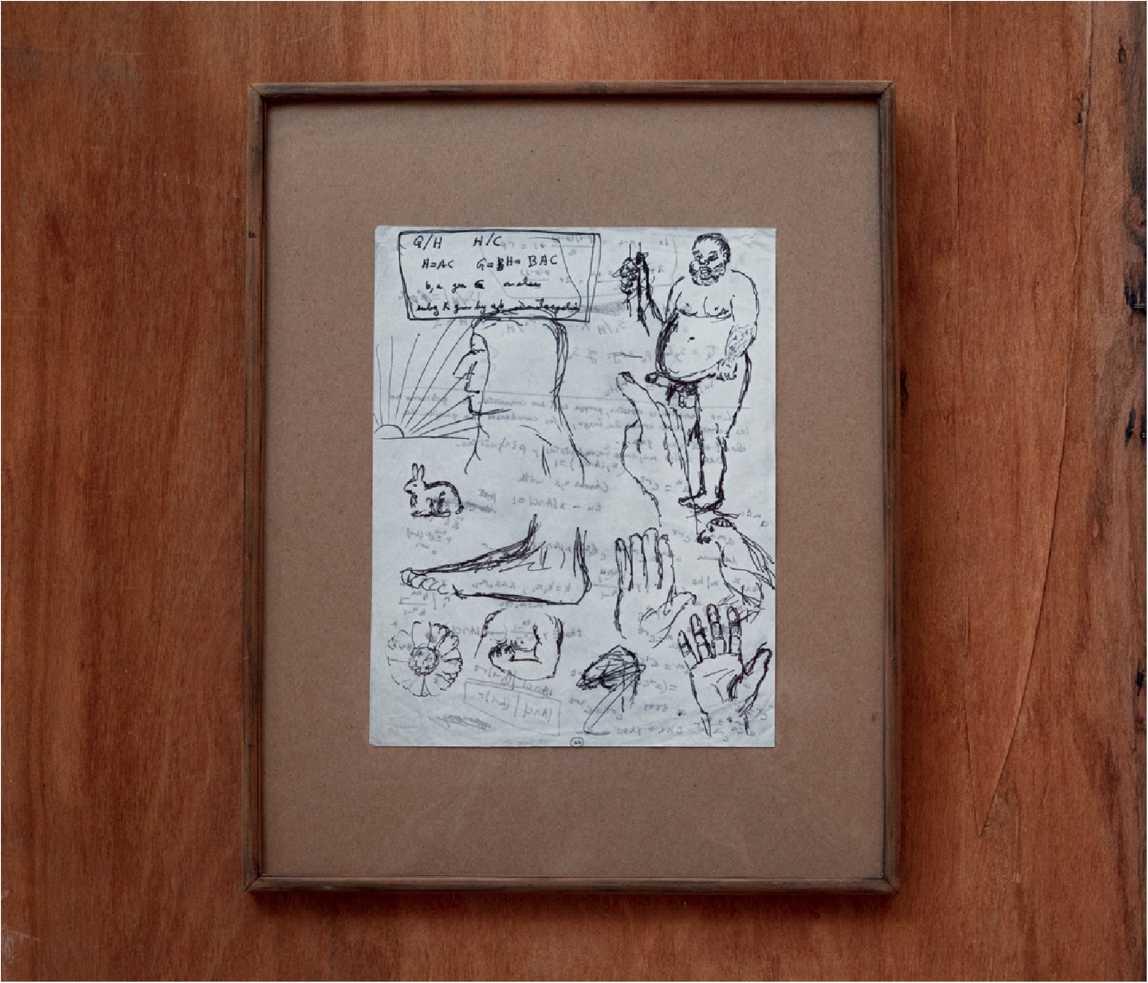

Ted Kaczynski

Untitled, c. 1980

Laser print on paper

11 in. x 81/2 in.

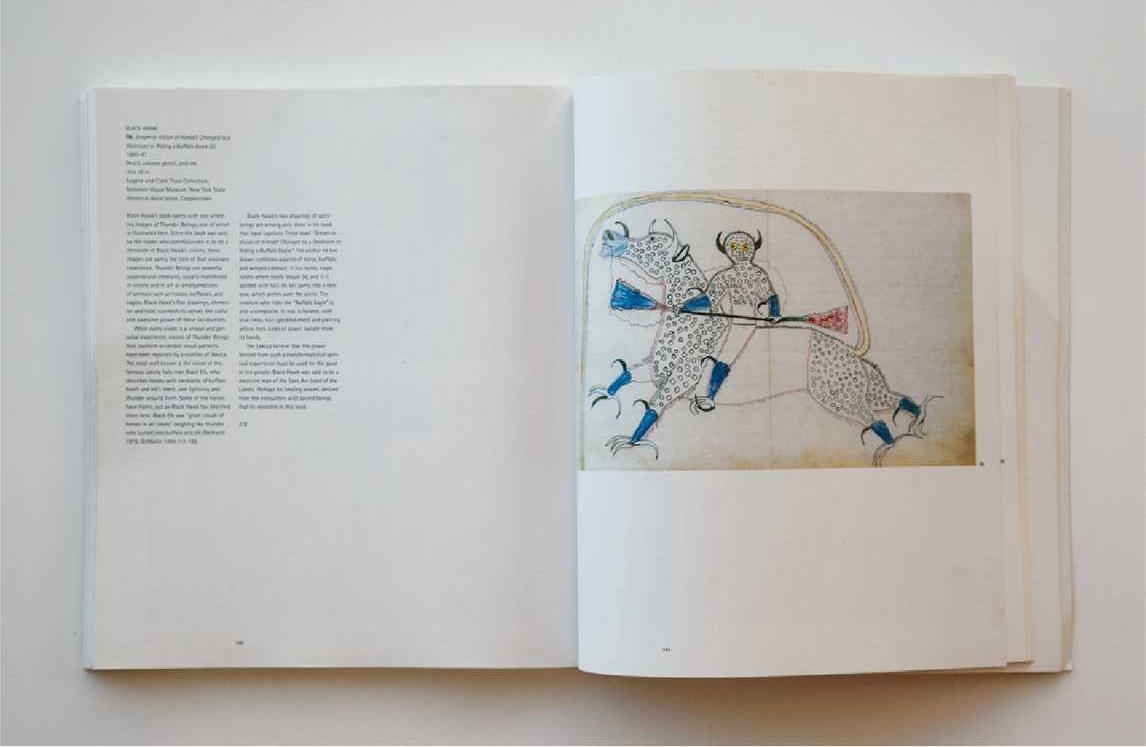

Black Hawk

Dreams or Visions of Himself Changed to a Destroyer or Riding a Buffalo Eagle,

1880–81

Pencil, color pencil, ink, poster paint on found paper

10 in. x 16 in.

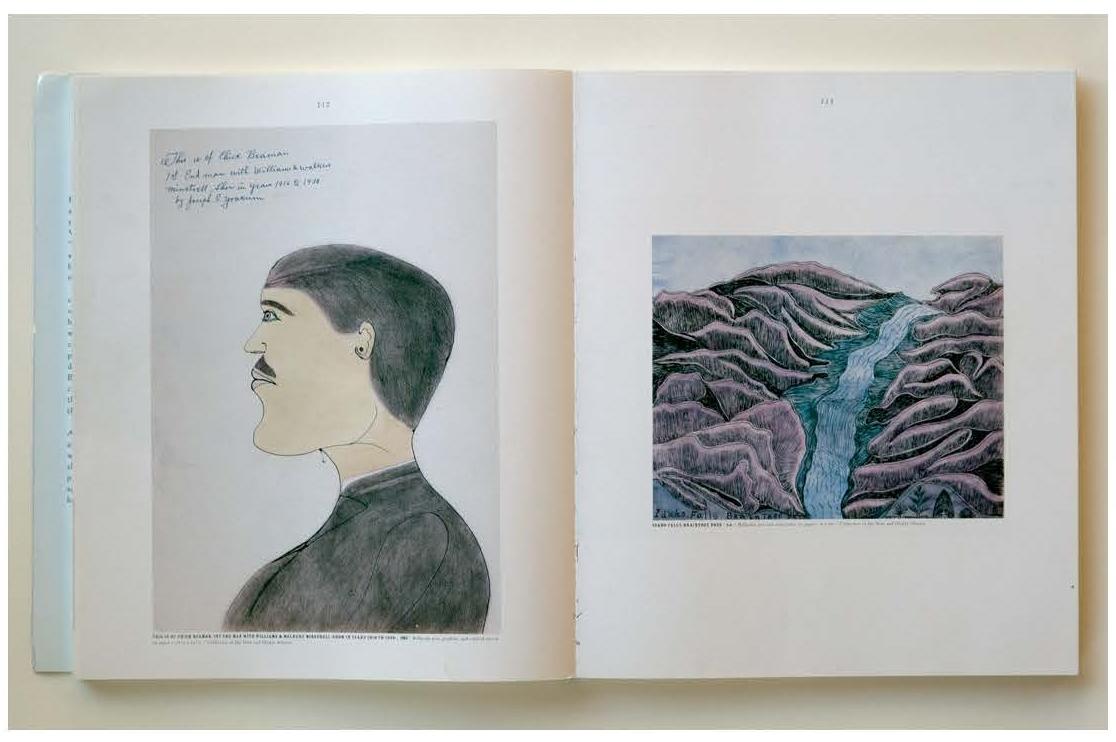

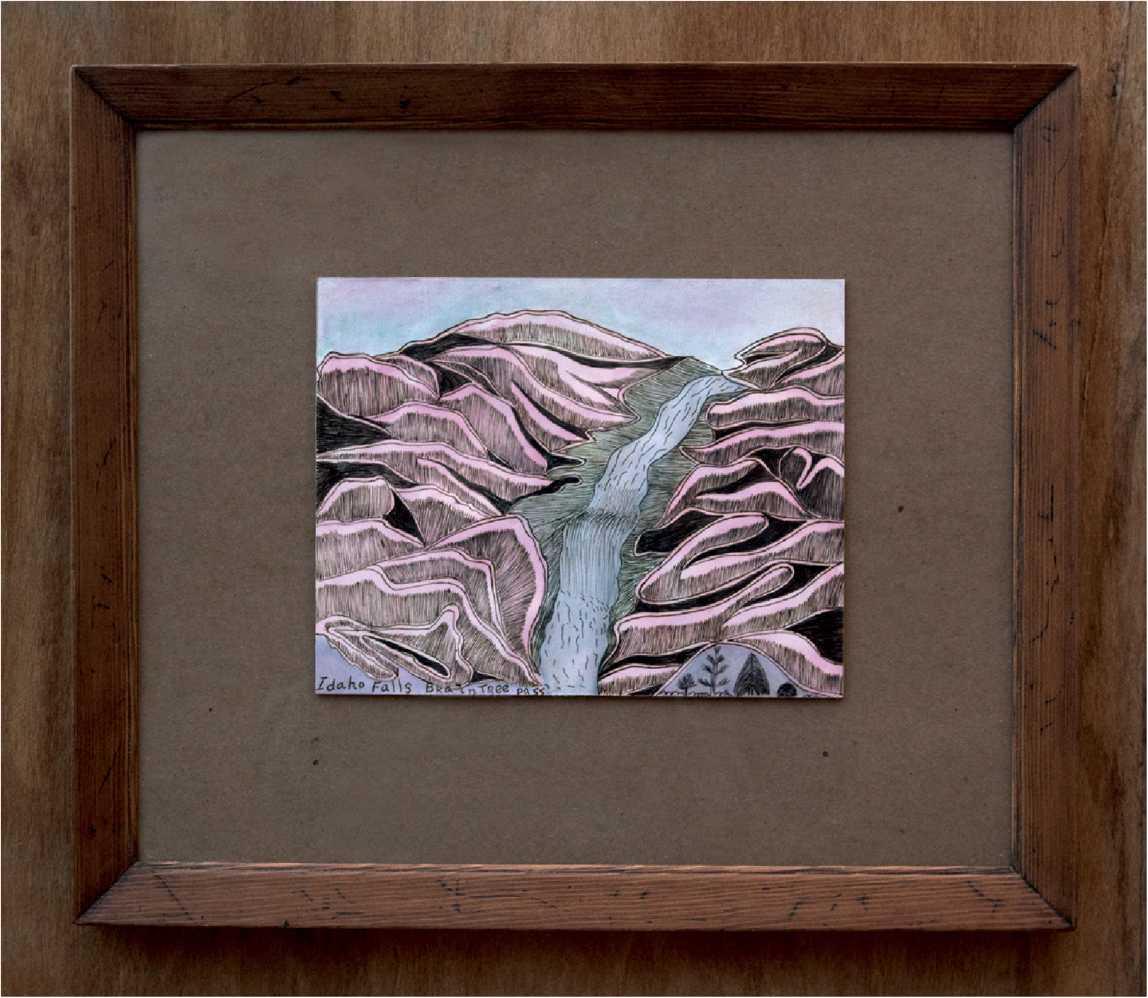

Joseph E. Yoakum

Idaho Falls Braintree Pass, c. 1966 Ball point pen, watercolor on paper 8 in. x 10 in.

Artifacts

Ted Kaczynski

Typed motto, c. 1985

Ink on paper

<br3/4 in. x 3 1/2 in.

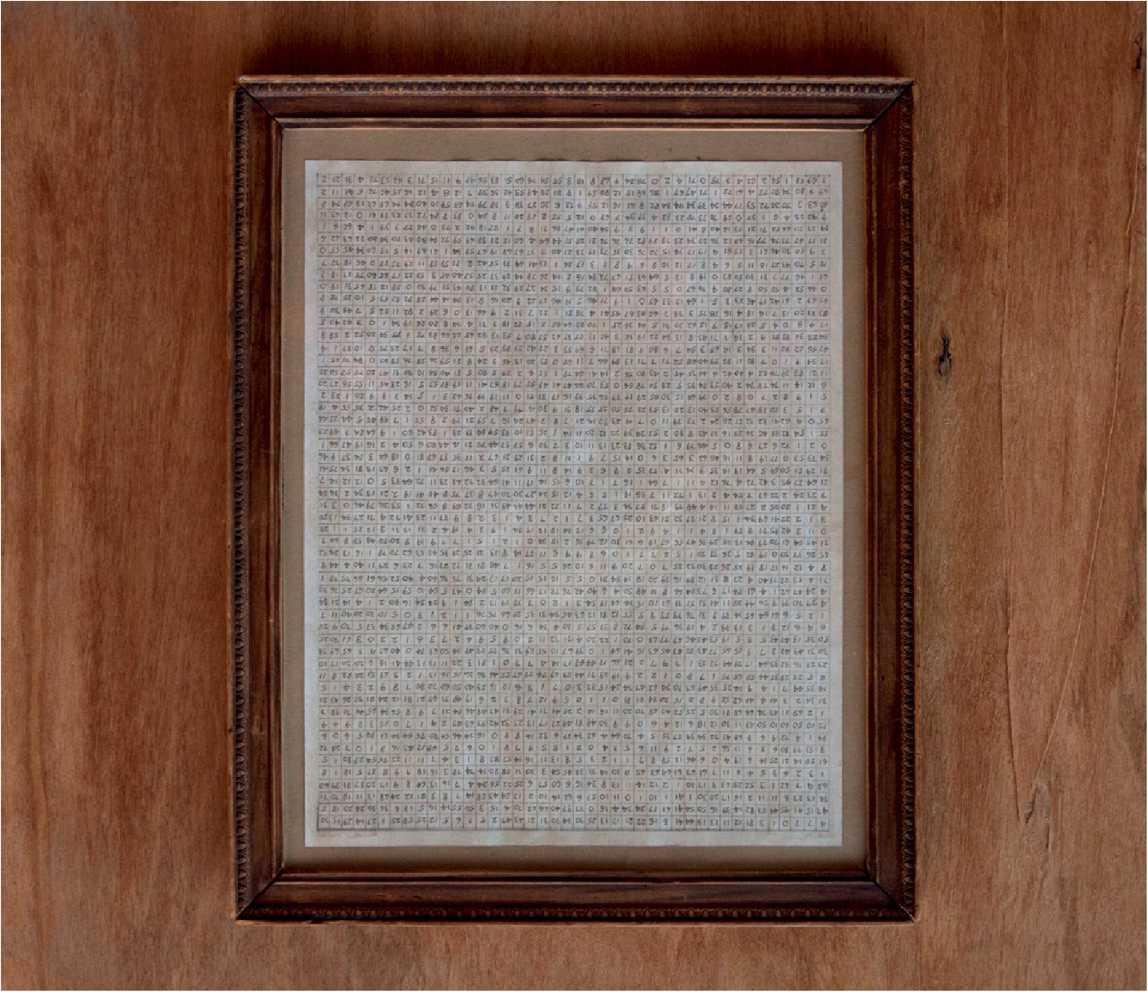

Ted Kaczynski

Code numbers, 1981

Pencil on paper

10 in. x 8 in.

Furnishings

Navajo Rug, 1910

3 ft. 4 in. x 5 ft. 6 in.

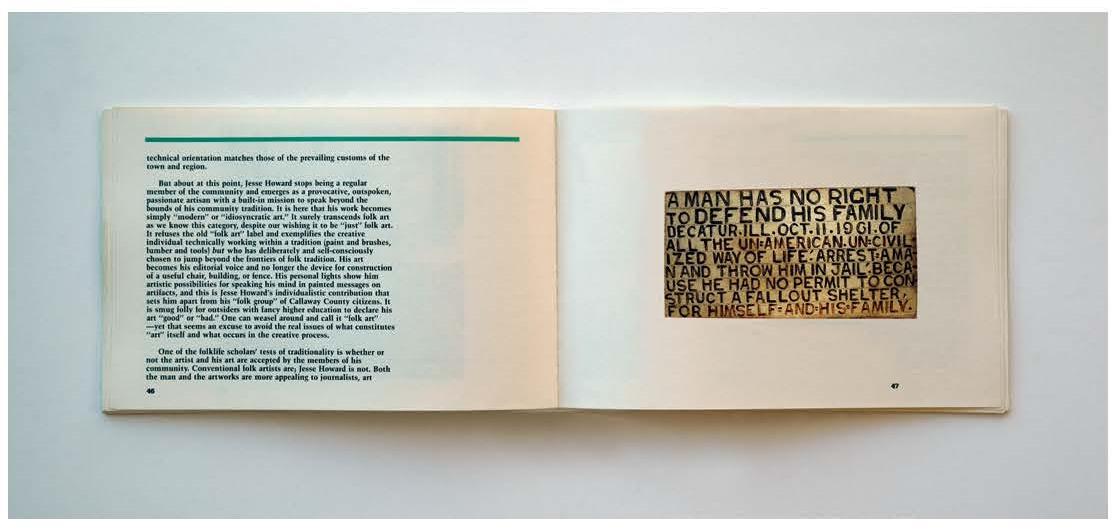

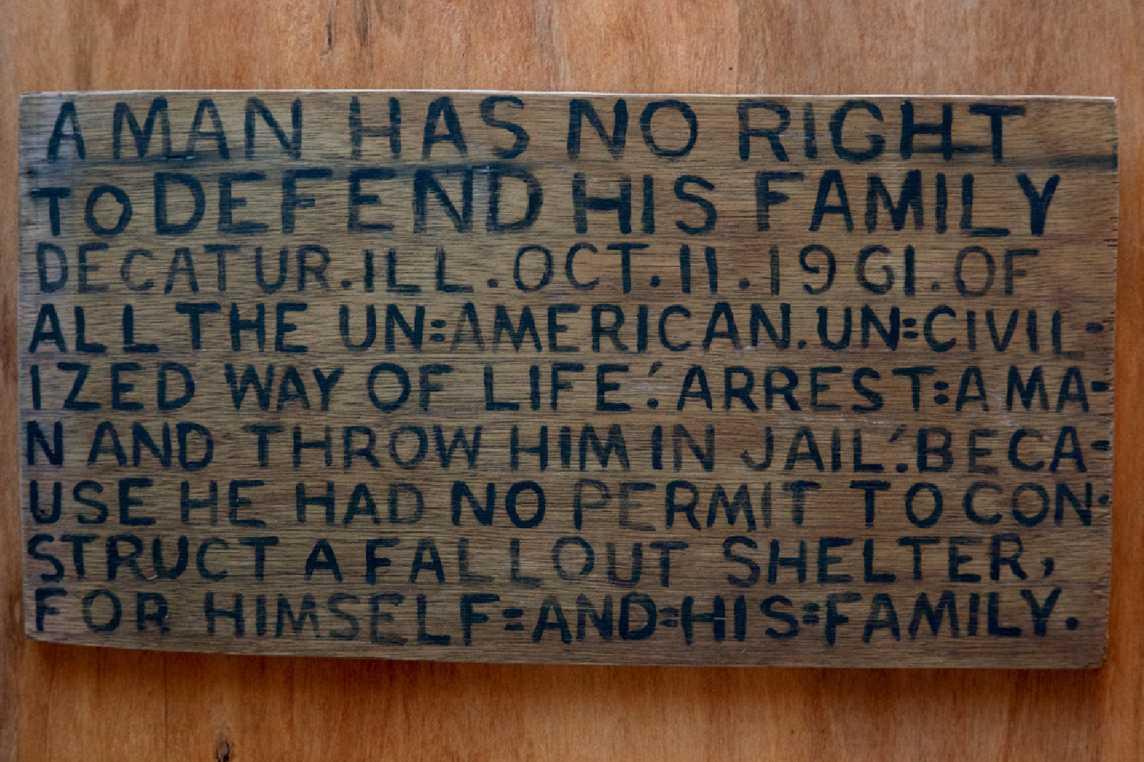

Jesse Howard

Untitled (A Man Has No Right to Defend

His Family), 1955

House paint on plywood

10 1/4 in. x 19 3/4 in.

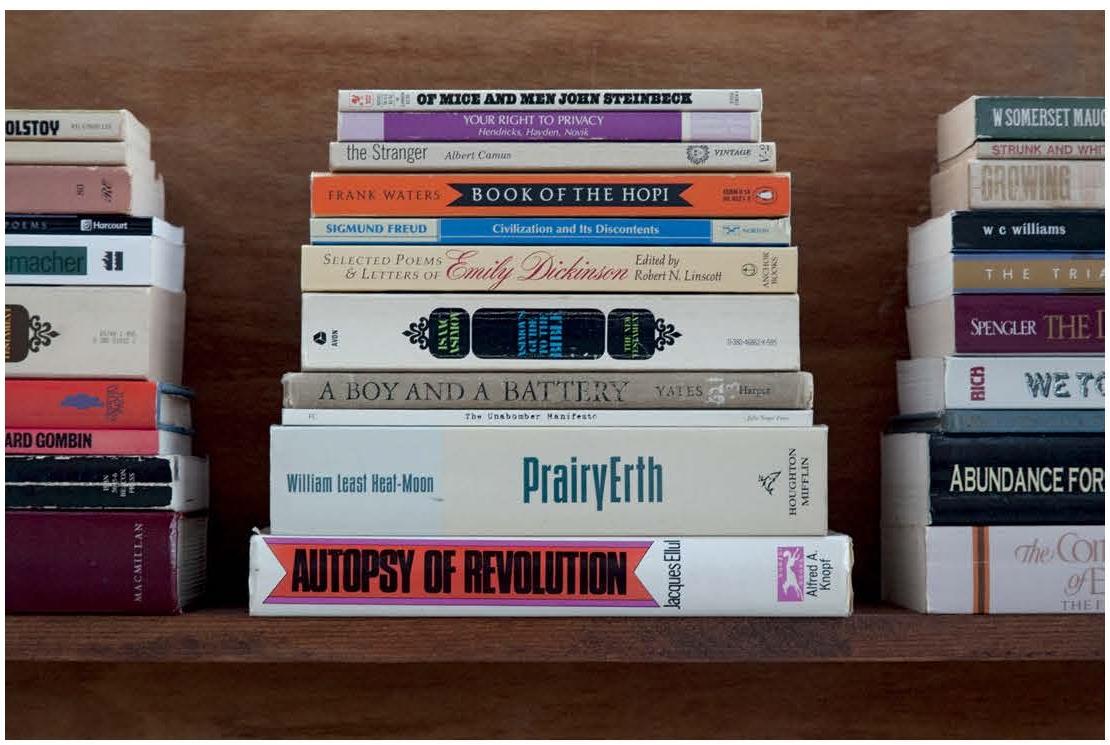

Kaczynski Cabin Library (11 Stacks, listed from bottom to top)

1.

Betty Owen, Typing for Beginners, 1976[4]

Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, 1906

Richard Rhodes, The Inland Ground, 1969

National Rifle Association, The Basics of Rifle Shooting, 1987[5]

Robert Silverberg, The Pueblo Revolt, 1970

Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 1883[6]

Olaus Johan Murie, A Field Guide to Animal Tracks, 1954[7]

Arthur P. Mendel, ed., Essential Works of Marxism, 1961

William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, 1596[8]

William Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury, 1929

Ivan Turgenev, Fathers and Sons, 1862

2.

Henry Jacobwitz, Electronics Made Simple, 1958[9]

United States Department of Justice, The Science of Fingerprints, 1973[10]

Alexandra Orme, Comes the Comrade!, 1949[11]

Richard Lattimore, The Revelation of John, 1962

Fyodor Dostoevski, Brothers Karamazov, 1878[12]

Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, 1964

Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha, 1951

Chandler S. Robbins, Bertel Brunn, Herbert S. Zim, Arthur Singer, Birds of

North America, 1966

Don Armando Palacio Valdes, Maximina, 1888[13]

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World, 1932

3.

Anthony Gooch, Angela Garcia de Paredes, Cassell’s Spanish-English/English-

Spanish Dictionary, 1978[14]

Robert V. Daniels, Red October, The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, 1967

Richard Gombin, The Radical Tradition, 1978[15]

Arthur H. Bremer, An Assassins Diary, 1973[16]

Isaac Asimov, Asimovs Guide to the Bible, The Old Testament, 1968[17]

E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful, 1973

T. S. Eliot, The Wasteland and Other Poems, 1930

Jack London, Martin Eden, 1913

Eric Hoffer, The True Believer, 1951[18]

Leo Tolstoy, The Cossacks and The Raid, 1862[19]

4.

Jacques Ellul, Autopsy of Revolution, 1971[20]

William Least Heat-Moon, PrairyErth, 1993

FC, Industrial Society and Its Future, 1995[21]

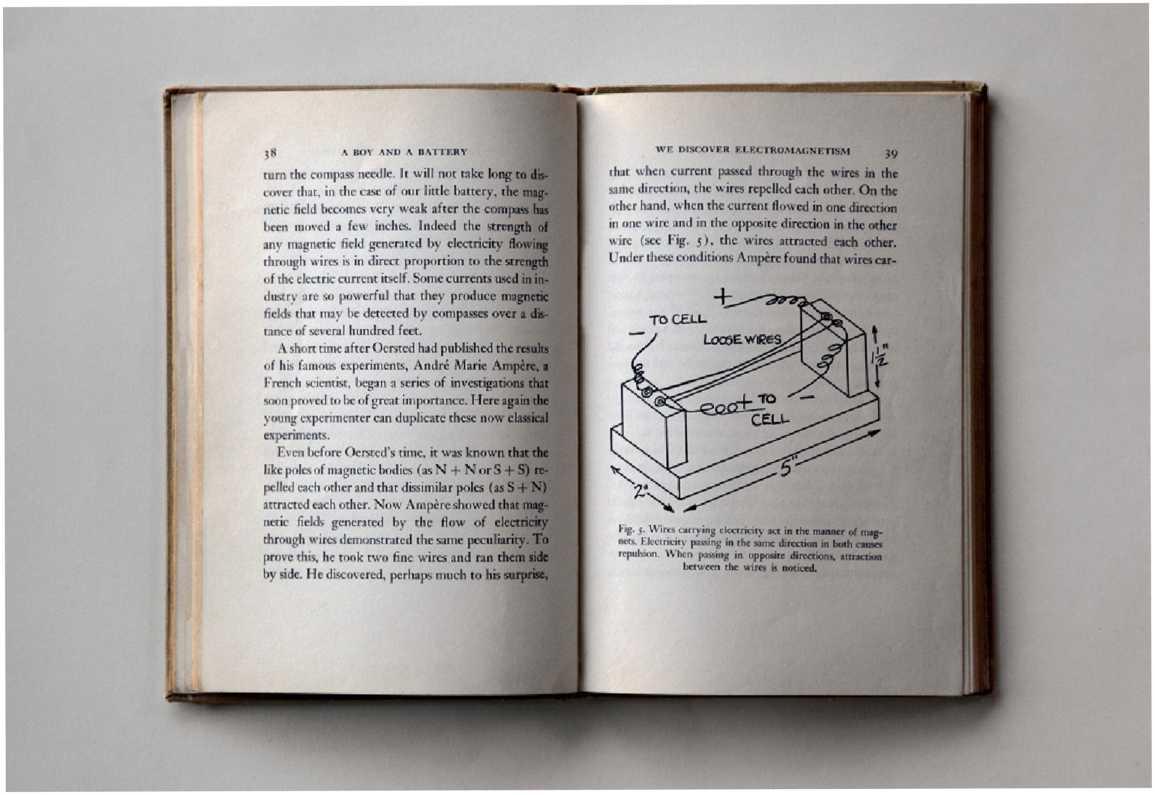

Raymond F. Yates, A Boy and a Battery, 1942

Isaac Asimov, Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, The New Testament, 1969[22]

Robert N. Linscott, ed., Selected Poems & Letters of Emily Dickinson, 1959

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, 1930

Frank Waters, Book of the Hopi, 1963

Albert Camus, The Stranger, 1946

Evan Hendricks, Trudy Hayden, Jack D. Novik, Your Right to Privacy, 1980[23]

John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men, 1937[24]

5.

Ernest Hemingway, The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, 1987

David Riesman, Abundance for What?, 1964[25]

Norman Cousins, Modern Man is Obsolete, 1945

Louise Dickinson Rich, We Took to the Woods, 1942

Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 1918

Franz Kafka, The Trial, 1925

William Carlos Williams, In the American Grain, 1925

Paul Goodman, Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized

System, 1956[26]

William Strunk Jr., Elements of Style, 1959[27]

W. Somerset Maugham, The Razor’s Edge, 1944[28]

6.

Allan R. Buss, Wayne Poley, Individual Differences: Traits and Factors, 1976[29]

Horacio Quiroga, The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories, 1935

Euell Gibbons, Gordon Tucker, Euell Gibbons’ Handbook of Edible Wild Plants, 1979[30]

M. H. A. Newman, Topology of Plane Sets, 1964[31]

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949[32]

Margret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa, 1928

Saul D. Alinsky, Rules For Radicals, 1971

Niccolb Machiavelli, The Prince and The Discourses, 1950[33]

Theodore Roszak, Where the Wasteland Ends, 1972

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, 1859

7.

Lila Pargment, Beginner’s Russian Reader, 1977[34]

Richard Flacks, Making History, 1988

Romola Nijinsky, ed., The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, 1936[35]

Bernard DeVoto, ed., The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 1953

Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, 1878

Irving Kohn, Meteorology for All, 1946

Bradford Angier, How to Stay Alive in the Woods, 1956[36]

Albert Speer, Spandau: The Secret Diaries, 1976[37]

L. Sprague De Camp, The Ancient Engineers, I960[38]

Kenneth Keniston, The Uncommitted: Alienated Youth in American Society, 1966

8.

William Whyte, The Organization Man, 1956[39]

Stephen B. Oates, To Purge This Land With Blood: A Biography of John Brown, 1970

Colin Wilson, The Outsider, 1956

Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang, 1975

Jean Baker Miller, Toward a New Psychology of Women, 1976[40]

Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism, 1947

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, 1859[41]

Rosemary Sutcliff, Tristan and Iseult, 1971[42]

H. J. Eysenck, Sense and Nonsense in Psychology, 1957[43]

Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon, 1941[44]

Kiyoko & Nathan Lerner, Henry Darger’s Room, 851 Webster, 2007

9.

Andrew Robinson, Lost Languages, 1957[45]

Chester C. Tan, Chinese Political Thought in the Twentieth Century, 1971[46]

Michael Spivak, Calculus On Manifolds, 1966

William H. Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 1843[47]

Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1970

Aubrey L. Haines, ed., Journal of a Trapper: Osborne Russell, 1965[48]

Eugene O’Neill, The Iceman Cometh, 1946

R. W. B. Lewis, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy, & Tradition in 19th Century

America, 1955

Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent, 1907[49]

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Toms Cabin, 1852[50]

Ernest Seton-Thompson, Wild Animals I Have Known, 1898[51]

10.

Hugh Davis Graham, Ted Robert Gurr, eds., Violence in America, Volume 1, 1979[52]

Food and Nutrition Board, Recommended Dietary Allowances, 1974[53]

Bertrand Russell, Mysticism and Logic, 1917

Karl Marx, Das Kapital, 1848

Jules Michelet, History of the French Revolution, 1967[54]

James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1916

Walter Starkie, Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Hungary and Roumania, 1933[55]

Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd, 1874[56]

James Fenimore Cooper, The Deerslayer, 1823[57]

Sloan Wilson, Ice Rrothers, 1979[58]

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, 1845

11.

Ted Robert Gurr, ed., Violence in America, Volume 2, 1989[59]

Glen R. Johnson, Tracking Dog, 1975[60]

David A. Conway, Ronald Munson, The Elements of Reasoning, 1990

Henry David Thoreau, Walden and Civil Disobedience, 1854

Al Gore, Earth in the Ealance, Ecology and the Human Spirit, 1992

Lewis Mumford, The Conduct of Life, 1951[61]

Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1988[62]

J. W. Schultz, My Life as an Indian, 1935[63]

Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, 1964[64]

H. G. Wells, The War of the Worlds, 1898

Twelve People

James Benning

1.

David Henry Thoreau was born on July 12, 1817 at the family home on Virginia Road in Concord, Massachusetts. His father was John Thoreau. His mother was Cynthia Dunbar. David Henry was named after his father’s brother who had just died, and was the third of four children. The two older were Helen and John, Jr. The younger was his sister Sophia. At the age of twelve David Henry lost part of a toe while chopping wood. He attended Concord’s Center School and already as a child he was uncompromising. He looked up to his brother John. They were very close. When David Henry entered Harvard University in 1833, John paid his tuition. His sister Helen and an aunt helped with his expenses. He studied the classics, philosophy, and mathematics and lived at Hollis Hall. In 1835 he took the winter term off to teach school in Canton, Massachusetts. There he met the outspoken reformer, Orestes Brownson. David Henry graduated from Harvard in 1837 and soon after changed his name to Henry David, though never officially. He then took a teaching job at his boyhood school in Concord, but resigned within a few weeks after he was made to physically discipline six students — one of which was a family servant. On October 22, 1837 he began to write a journal. In 1838 he and his brother John started a grammar school called Concord Academy.

They stressed reasoning over memorizing and took their students on trips to the surrounding wilderness. In 1839 the brothers explored the White Mountains in New Hampshire spending a week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Two years later John suffered from tuberculosis and they were forced to close the Academy. Henry David then moved into a friend’s house working as a tutor, handyman, and gardener. In 1842 John died from tetanus. Henry David witnessed his death and soon after suffered from psychosomatic paralytic symptoms. For a few months in 1844 Henry David lived in Staten Island. There he met the abolitionist William Tappan and social reformer Lucretia Mott. He then returned to Concord to work in his father’s pencil factory where he discovered new ways to improve the production of graphite. His mother and sister were deeply involved in the abolition movement and Henry David followed their lead. In spring 1844 he accidentally set fire to the Concord woods destroying 300 acres of mature forest. In March 1845 Henry David began squatting on eleven acres of land along the northern shore of Walden Pond. With a borrowed axe he cut down twenty tall white pines from which he hand crafted lumber. In the side of a hill that sloped toward the water he dug a cellar. In early May friends helped him raise the frame for a 10 x 15 foot cabin. He then bought an old shed from an Irishman who worked on the Fitchburg Railroad. From it he salvaged wood and nails. By July 4, 1845 the cabin was boarded and roofed and Henry David moved in. By September he finished the lath and plastering and built a brick fireplace. In the fall he shingled the roof and outside walls and built a chimney. By winter the cabin was complete. The fireplace was opposite the front door, and the two sidewalls each had a large window measuring 6x3 feet. The ceiling was 8 feet high. In the spring Henry David planted two and a half acres chiefly with beans, but also a small part with potatoes, corn, peas, and turnips. He began to openly oppose U.S. policy on both slavery and the Mexican-American War. In summer he was jailed for withholding his poll taxes. His aunt paid what he owed and he was released the following day. He was furious with her. She was the same aunt who had helped him with expenses at Harvard. On September 6, 1847 Henry David left Walden. Except for a short trip to the Maine woods and the day in jail, he lived there for two years, two months, and two days. In 1851 he became the land surveyor of twenty-six square miles of forest for the township of Concord and during that same time became more actively involved in the Underground Railroad hiding escaped slaves at the family home and aiding their flight to Canada. He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three. In 1854 he traveled to Philadelphia and New York City. In 1857 he met John Brown and donated a small amount of money to his cause. In 1859 Brown was captured after invading Harper’s Ferry and hung for treason. Shortly after Henry David helped one of Brown’s accomplices escape to Canada. In 1860 Henry David contracted bronchitis and then tuberculosis. The next year he visited Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul where he collected various specimens of plants and met with Native Americans. Henry David died on May 6, 1862. He was forty-four and had kept his journal for almost twenty-five years. It filled twenty-six handwritten volumes and contains over two million words.

3.

Bill Traylor was born sometime in the early spring of 1853 or 1854 on a small cotton plantation near Benton, Alabama. He was third generation American. His parents, Bill Calloway and Sally Traylor, were the property of George Traylor. Sally was born in Virginia in 1815 and became a Traylor slave a few years later. Bill’s father was purchased from the Calloway estate in 1840. Bill joined his father, mother, sister, and three brothers as a Traylor possession upon birth. He started working the cotton fields at the age of six. When the Civil War ended, Bill and his family remained on the Traylor plantation. His father died when Bill turned seventeen, and he became the head of the household. In 1884 the first of his eight

children with Larisa Dunklin was born. Twelve years later the first of five children with Laura Williams was born. Bill was still living with Larisa at the time. He and Larisa had their seventh child that same year. In early 1904 Larisa took an outside lover. A few months later the lover was found dead. The death was never investigated. Larisa then disappeared taking with her their youngest child, whose name was Child. By 1909 Bill gathered together children from both marriages and with Laura moved to land he had rented from the Will Seller plantation near Montgomery, Alabama. No longer a sharecropper, Bill became a farmer. The price of cotton rose and Bill’s family made their way; then the stock market crashed and personal tragedy hit. On August 26,1929 Laura and Bill’s son Will was shot to death by two Birmingham policemen. The official report claimed he had a gun and was breaking and entering. Bill believed it was a police execution of yet another Negro, and it disturbed him greatly. By 1935 Bill’s farm had failed and he moved by himself into Montgomery. He rented a small shanty on Bell Street for $6 a month and made money repairing shoes. During his spare time he sat outside his door and began to draw on small scraps of discarded cardboard. He was 83 years old. Within a year his shoe repair business failed and he could no longer afford rent. He found a place to sleep in the back room of Dave Ross’s funeral parlor, along with a number of other homeless black men. Later that year Bill began to receive $15 a month from the Montgomery County Old Age Assistance Program. In spring 1939 Charles Shannon, a young white man, found Bill drawing on Monroe Street a block down from the funeral parlor. They became friends and Charles brought Bill charcoal, brushes and paint. In June 1939 Bill moved from the funeral parlor to a shoe-repair shop on Lawrence Street. Ten feet up the block toward the corner of Monroe was the locked back doorway of a colored-only pool hall next to a fruit stand run by Isaac Varon. Bill sat there from morning until night for the next three years completing over 1500 paintings and drawings of what he saw or remembered. In the fall of 1942 he left Montgomery to visit some of his children living in the north. He returned a year later. Shortly after he lost a leg to gangrene and joined the Catholic Church. The county found Child living in Montgomery, and his old age pension was denied. She reluctantly took him in. He tried painting again, but with less passion. Except for his name, Bill Traylor never learned to read or write. He died on October 23, 1949 at Montgomery’s Oak Street Hospital. His death was never reported to the Alabama Health Department.

4.

Moses Ernest Tolliver was born on July 4, 1921 or 1922, but it might have been as early as 1915. His parents were Ike and Laney Tolliver. Mose was the youngest of twelve children. They worked as sharecroppers on the Charles Rittenour farm in the Pike Road Community a few miles southeast of Montgomery, Alabama. When Mose was eleven the family moved to Macedonia, Alabama, where he attended Mount Olive School. He soon quit to help with the family farming. Later Mose worked for a dry cleaning business and then operated a small truck-farm gathering produce. In 1935 his father died and his mother moved the family to the black side of Montgomery. There they settled into one of the small wooden duplexes on Sternfield Alley. Years later all of Sternfield Alley was razed to make room for the Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway. Mose first worked tending gardens on the white side of town and later did house painting, carpentry, and plumbing. In the early forties he married Willie Mae Thomas in a ceremony held at South Union Baptist Church. Soon after his wedding, he spent six months in the Army at Fort Benning, bringing about his own discharge. Over the years he fathered thirteen children, of which eleven survived. To support his family Mose did mostly unskilled labor. In 1968 while working at McLendon’s Furniture Company he was injured when a thousand pound crate of marble fell from a forklift. His left ankle was crushed. Muscles and tendons in his left leg were badly hurt. He was unable to walk without crutches. He was forced to stop working. He was in constant pain and drank heavily. Then he found the urge to paint and quit drinking. Sitting at his bed, he would complete eight to ten paintings a day. In 1975 he learned to write his name. He purposely wrote the ‘s’ in Mose backwards. In 1991 Willie Mae died. The two had been married for almost fifty years. His spirits fell severely low. He stopped painting. He missed Willie Mae terribly. But then he started to paint again, and continued until his death. He died on October 31, 2006 leaving behind thousands of paintings signed Moze T.

5.

Henry Darger was born at home in Chicago on April 12, 1892. His parents were Henry Joseph Darger and Rosa Fullman Darger. Henry’s father was a tailor from Meldorf, a small town in northern Germany. Rosa was from Bell Center, Wisconsin. She died on April 1, 1896 shortly after giving birth to a baby girl. Henry was about to turn four. His father gave the baby up for adoption. Henry and his father then moved to a two-room apartment in the small alley of the 100 block between Adams and Monroe Streets. There his father taught Henry to read before he entered school. Henry had extraordinary intelligence. At St. Patrick’s Catholic Boys School he skipped the 2nd grade, but due to his father’s long working hours and crippling health, Henry was left to himself. He began to hate small children and he hated his father for giving his sister away. He became physically abusive. He started fires. He cut a teacher with a knife. He blamed God. He punched pictures of Jesus in the face. Then he took Confession and changed, wanting only to protect children. At the age of eight, Henry was sent to The Mission of our Lady of Mercy, also known as The News Boys’ Home, and switched to a public school called The Skinner.

Here his new environment was harsher. He began to make peculiar hand gestures and uncontrollable sounds. He appeared to be seriously disturbed. In 1904 his father moved to a Catholic old age home, run by the Little Sisters of the Poor. Henry never saw his father again and was committed permanently to the Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children in Lincoln, Illinois. There he was relatively happy. It was safer and undemanding. A mile south near the Salt Creek the Asylum ran a dairy farm. Henry worked the summers there. On March 1, 1908 his father died. The next summer Henry and two other boys escaped from the Asylum farm. They hopped a freight train to Decatur and found work for a few months with a German farmer. This was the third time Henry had run away, but this time he didn’t return, instead he walked 175 miles to his godmother’s house in Chicago. She helped him get a job as a janitor at St. Joseph’s Hospital. There he took a room at the Workingman’s House and someone stole one of his notebooks. A year later Henry clipped a photo of five-year old Elsie Paroubek from the May 9, 1911 Chicago Daily News. She had been kidnapped and murdered. Then someone took the photo. Henry obsessed over his losses. He blamed God and again became blasphemous. One of the hospital nuns started calling him Crazy, a name that stuck with him forever. In 1917 Henry was drafted into the Army. He trained in Rockford, Illinois with Company L of the 32nd Infantry, and was sent to Camp Logan, Texas. Soon after, Henry developed an eye infection and was honorably discharged. He returned to St. Joseph’s Hospital and worked there until 1922 quitting due to a running battle with Sister DePaul. She was the one who named him Crazy. He then took a job as a dishwasher at Grant Hospital and moved to a boarding house at 1035 Webster Street. In 1928 he returned to St. Joseph’s Hospital where he remained a dishwasher. Sister DePaul had died. In 1932 he moved to a rooming house at 851 Webster Street owned by Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner. Henry carried his belongings down the street two blocks from one house to the other. His new room was in the back on the third floor. In 1947 he began to work at Alexian Brothers Hospital, again as a dishwasher. He was later transferred to the bandage room. At each job he always worked in the back having little contact with the public. Henry’s only known friend was William Schloeder who he met around 1910. They formed a secret children’s protective society they called the Black Brothers Lodge. In 1956 after forty-six years of friendship, William moved to San Antonio, Texas. He died three years later. On November 19, 1963 the pains from old age forced Henry to retire. He had worked fifty-four uninterrupted years, six to seven days a week, eight to ten hours a day. He never depended on welfare or charity. Henry then began to visit twice daily St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church attending both Mass and Communion. He walked the streets and alleys looking for discarded books and magazines. He collected junk and string. On March 24, 1968 Henry began to keep a personal diary. In 1969 he got hit by a car. In 1971 he had an eye operation. On November 15, 1972 Henry left 851 Webster Street and moved to St. Augustine’s Home for the Aged. He took nothing with him. He had lived in the same room for forty years. It had three light bulbs and measured 17 feet 6 inches by 13 feet 9 inches with a 9 foot 8 inch ceiling. It was filled from floor to ceiling. Found among the complete works of Frank L. Baum, two postcards picturing Henry and his friend William, bundles of magazines and newspapers, scrapbooks filled with thousands of cartoon clippings, and many balls of string, was a lifetime of work. From 1911 until the early 1930s, Henry wrote In the Realms of the Unreal. It consisted of 15,145 typewritten pages and filled thirteen hand-bound volumes. Somewhere in the middle of The Realms Henry copied word for word Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. In the early 1940s Henry began a 10,461 page handwritten sequel to The Realms called Further Adventures in Chicago: Crazy House and began to illustrate his writings with hundreds of paintings, many were over 12 feet long, some painted on both sides. On December 31, 1957 he began a daily weather diary that lasted for exactly ten years. It fills nine volumes, and on the last page he wrote the word “finished.” In 1963 he began an autobiography, The History of My Life. The first 206 pages give details about his life. The next four thousand pages are about a tornado that eventually becomes known as “Sweetie Pie.” Henry Darger died on April 13, 1973, a day after his 81st birthday.

6.

Martin Ramirez was born on January 30, 1895 in Rincon de Velazquez, a small rural village at the center of Los Altos de Jalisco, a place of pure Spanish blood in west-central Mexico. His parents were Gertrudis Ramirez and Juana Gonzalez. He was the youngest of eight children. His father was an impoverished sharecropper who taught all of his children to read. They attended Mass at the Parish of Capilla de Milpillas. Martin married Maria Santa Ana Navarro Velazquer there in 1918. She was a 17-year old orphan, and somewhat poorer. Together they worked the El Venado rancheria and then moved to La Puerta del Rincon and El Pelon. Maria Santa Ana gave birth to a daughter at each place. Their names were Juana, Teofila, and Agustina. In 1923 Martin bought fifty acres of land on credit near San Jose de Gracia. It included a house and orchard. He added a milk cow and a horse, pigs and sheep, two deer, and a vegetable garden. Debt mounted. In 1925 he crossed the border at El Paso looking for extra work. Martin didn’t know his wife was pregnant. In February 1926 a son was born. She named him Candelario. Martin found work with the railroads in northern California. He sent money back home to Mexico. His wife sent him a picture of herself and their four children. In 1927 the Cristero Rebellion began. Although his wife and children survived, their property was lost to the struggle. Martin’s brother wrote him the news. Somehow Martin misinterpreted the letter. He mistakenly thought his wife had given help to the government soldiers that confiscated his land. He wrote his brother back saying he would never return to Mexico and wished for his children to be taken from his wife. Then in 1930 the Depression eliminated any work for Martin in the U.S. He couldn’t speak English. He was caught between two disintegrating worlds. He was destitute, and became depressed and disoriented. On January 9, 1931 Martin was committed to the psych ward at Stockton State Hospital. Over the next eight years he escaped many times, but always returned on his own. Each time his diagnoses escalated — first from manic depression to a catatonic form of dementia praecox, and then finally to incurable schizophrenia. He became somewhat mute. Around 1935 he began to draw obsessively. He made his own paper using a paste made from potato starch. After seventeen years at Stockton, Martin was moved to Dewitt State Hospital in Alburn, California. All of his drawings were sent to his wife in Mexico. She hung them on an outside wall of her adobe home. Later she stored them under a mattress. On January 6, 1952, Martin got his only visitor, Jose Gomez Ramirez, the son of his older sister. The nephew learned Martin had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Martin’s wife then burned his drawings along with the mattress. At Dewitt State Hospital, Martin remained quiet and continued to draw. Sometimes he drew the same picture twenty times. In 1951 he was discovered by Tarmo Pasto, Professor of Art and Psychology at nearby Sacramento State College. Pasto made a career from studying Martin. Martin continued to draw from morning until night, seven days a week until pulmonary edema brought about his death on February 17, 1963. He left behind over three hundred paintings. In 1995 ten more were found locked away and forgotten in a storage warehouse of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. They had been there forty years. Pasto had sent them to James Johnson Sweeney, the director of the museum, in 1955. Martin was buried in a pauper’s grave.

7.

William Hawkins was born in rural Kentucky outside of Lexington on July 27, 1895. Two years later his mother gave birth to another boy, Vertia. She died a short time after, and his father dropped the two boys off with their maternal grandmother. Her name was Mary Mason Runyon Scudder. She owned a farm that was somewhat prosperous, raised horses, and was an accomplished quilter and God-fearing Christian. William attended school through the third grade. He never learned to read or write. At home he operated farm equipment, and repaired buildings and fences. He hunted and trapped, and often bragged about the money his pelts would bring. In 1916 his girlfriend became pregnant and his grandmother sent him away to Columbus, Ohio to live with relatives. He got a job at a steel casting company. About the time his child was born he was drafted into the Army and served in the Great War with an all black regiment. Over the next sixty years he held many jobs. He drove a delivery truck, did carpentry, masonry, plumbing, and painting. Later he ran a shelter for homeless youth, a brothel, and a flophouse. He was a storyteller, and a collector of cardboard, newspapers, magazines, scrap wood, metal, linoleum, and hubcaps. He sold candid photographs on the street. At the age of 80 he began to paint and continued for the next fourteen years. William Hawkins died in January 1990 at the age of 94.

8.

Henry Aaron was born on February 5, 1934 in a low laying, poor black section of Mobile, Alabama known as Down the Bay. His parents were Herbert Aaron and Estella Pritchett Aaron. His father came from a long line of preachers. Henry’s great grandmother was half Cherokee. He was the third of eight children, all baptized at Morning Star Baptist Church. His mother was a member there. His father attended an Episcopal church where the services were shorter. At the start of WWII Henry’s father began working as a boilermaker’s assistant at Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding. For some weeks he was escorted to work by armed guards when white dockworkers rioted over the hiring of Negroes. Henry’s younger brother Alfred died at two. His sister Alfredia was born shortly after. Years later, Henry would help send both Alfredia and his younger brother James to college. In 1942 Henry’s father moved the family to nearby Toulminville and paid two carpenters $100 to build a six-room house. Henry’s father scavenged the wood and his mother pulled and straightened nails. Then his father got laid off at the dry docks and opened a small tavern next to their house called the Black Cat Inn. He also did some bootlegging. Henry picked potatoes, mixed cement, delivered ice, and wore hand-me-down clothes worn by his older sister. He loved baseball. He practiced by hitting bottle caps with a broomstick. Later he made a bat from a tree branch and a ball from scraps of rubber and old nylon stockings. Henry batted cross-handed. In 1945 Toulminville became part of Mobile and Washington Carver Park was built across the cornfield from Henry’s home. It was the first park for blacks in Alabama. Henry played there as much as he could. At 17 he joined a semi-pro baseball team, the Mobile Black Bears, but his mother wouldn’t allow him to travel, so he could only play the Sunday home games in nearby Prichard. Henry attended Central High School for four years. In 1952, just before graduating, he left home with the barnstorming Indianapolis Clowns, one of the last teams of the old Negro Leagues. Henry, having never gone any further than Prichard, traveled to Winston-Salem, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Memphis, Little Rock, Hot Springs, Nashville, Greenwood, Cullman, Oklahoma City, Sikeston, Asheville, Denton, and Spartanburg. He never played in Indianapolis. Within the year the Clowns sold Henry to the Boston Braves. They sent him to their Class-C farm team, the Eau Claire Bears in the Wisconsin Northern League. There he stopped batting cross-handed and was named Rookie of the Year. The next year he was sent to the Class-A Jacksonville Tars in the Sally League. There he was voted Most Valuable Player. At both Eau Claire and Jacksonville he broke the color barrier. In Jacksonville Henry met Barbara Lucas. She was a Florida A&M college student. They got married in the fall on October 6, 1953. Their first child, Gaile, was born in Puerto Rico. The Braves had sent Henry there to play in the Winter League. Henry and Barbara had four more children: Hankie, born in early spring of 1957; twins, Lary and Gary, born later that same year in December — Gary died in the hospital a few days after birth; and their last, Dorinda, born on Henry’s birthday in 1962. Henry began his Major League career with the Milwaukee Braves on April 13, 1954. He played for twenty-three seasons. By 1970 it became apparent that Henry was in reach of the all-time home run record held by Babe Ruth. The next year Barbara filed for divorce. At the end of the 1973 season Henry was one home run short of tying Ruth’s record. During the off-season he received almost a million letters — more than some were hateful, bigoted, and life threatening. In November Henry married Billye Williams, an Atlanta news anchor, and later adopted her daughter, Ceci. Billye’s first husband was the late Dr. Sam Williams, an Atlanta civil rights activist. On April 8, 1974, Henry hit his 715th career home run breaking Babe Ruth’s record. When Henry retired in 1976, he was the last Major Leaguer to have played in the Negro Leagues. In 1982 Henry became a vice president and director of player development for the Atlanta Braves. He was one of the first blacks in baseball to be hired for an upper-management position. Since, he has fought for racial parity on and off the field.

9.